Abstract

Background

Tanzania has a young mining history with several operating open pit and underground mines. No prevalence studies of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) have been conducted among mine workers to provide an impetus for the development of comprehensive hearing protection programmes.

Aims

To determine the prevalence of NIHL and associated factors among miners in a major gold mining company operating in Tanzania. Associated risk factors such as age, sex and duration of exposure were examined.

Methods

Audiograms obtained from periodic medical examinations were categorized using the UK Health & Safety Executive system.

Results

A total of 246 audiograms were studied. The prevalence of NIHL was 47%, with 12% with poor hearing and 35% with mild hearing impairment. The proportion of NIHL increased with total years of exposure to noise. Underground miners were more affected (71%) than open pit miners (28%). These findings were statistically significant. The highest proportion of miners with NIHL (60%) was among the youngest age group (20–29 years).

Conclusions

There was a high prevalence of NIHL in the company under study. There was a strong correlation with type of mining, age and years of exposure. The findings have been used to develop comprehensive hearing conservation programmes.

Key words: Exposure duration, HSE categorization, noise-induced hearing loss, mining, presbycusis.

Introduction

The mining industry contributes significantly to Tanzania’s foreign exports, direct foreign investment and the country’s gross domestic product [1]. Within this industry the greatest risks to health are from silica and noise exposure. The Tanzania Mining Act 2010 set an occupational exposure limit for noise at 85 dB(A) [2]. The Tanzania Occupational Health and Safety Act require employers in all industries to conduct periodic occupational medical examinations but there are no government data on miners’ exposure to hazardous noise [3].

A few African countries have prevalence studies of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) to draw from. In a Ghanaian gold mine study, 23% had a ‘notch’ in the audiogram at 4kHz [4], while in a South African mining workforce, 22% had NIHL [5]. Data suggest that males are most affected by the condition [6] and that age is an important confounder for hearing loss. An in-depth analysis showed that the prevalence of NIHL varied according to diagnostic criteria applied and the age group tested [7]. A South African study showed no cases in the youngest age group but a prevalence of 22% in workers aged 58 and over [5]. A similar study in Zimbabwe with a prevalence of 27% found 60% of cases in the oldest group (50 and over) and the lowest prevalence (5%) among the youngest (age 20–29) [8]. Another South African study found the highest degree of hearing deterioration among miners aged over 50 [9].

The Zimbabwean study showed that those most affected had >20 years’ service [8]. The South African study also showed an increase in hearing deterioration with longer service [9]. In a Nigerian study miners with prior exposure had a higher prevalence of hearing loss [10]. Among Zambian miners with >20 years’ experience 23% suffered total hearing loss [11].

To date no studies have investigated NIHL in Tanzanian miners. This study therefore sought to ascertain the prevalence of NIHL and evaluate associated factors such as age, sex and duration of exposure.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study examining existing periodic audiograms of employees of a Tanzanian mining company to determine the prevalence of NIHL. Half the sample was drawn from an open pit mine and the other from an underground mine using a stratified random sampling technique. There are significant differences in noise exposure between open pit and underground mines. Industrial hygiene data from the company concerned show significant exposures to noise in some similar exposure groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Company industrial hygiene data on workplace noise exposures

| Underground | Open pit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Task designation | 8-h time-weighted average (TWA) exposure in dB(A) | Task designation | 8-h TWA exposure in dB(A) |

| Jumbo operator | 101 | Dozer operator | 89 |

| Jumbo helper/offsider | 97 | Drill operator | 98 |

| Jack leg operator | 105 | Grader operator | 93 |

| Alimak driller | 108 | Haul truck operator | 81 |

| Truck operator | 101 | Excavator operator | 90 |

| Long hole driller | 95 | Water truck operator | 87 |

Tanzanian legislation offers no guidance on categorization of workers’ audiograms and there are no normative data on hearing for the Tanzanian population. Cases were therefore identified and categorized using the UK Health & Safety Executive (HSE) system for categorizing audiograms in noise-exposed populations (Table 2) [12]. This does so according to the sum of hearing at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6kHz. Although criticized, the HSE system also allows for the identification of other forms of hearing loss [13].

Table 2.

HSE categorization scheme based on sum of hearing at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6kHz [12]

| Category | Calculation | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Acceptable hearing ability. Hearing within normal limits. | Sum of hearing levels at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6kHz. Compare value with figure given for appropriate age band and gender in standardized tables. | None |

| 2. Mild hearing impairment. Hearing within 20th percentile, i.e. hearing level normally experienced by one person in five. May indicate developing NIHL. | Sum of hearing levels at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6kHz. Compare value with figure given for appropriate age band and gender in standardized tables. | Warning. This means the employee has mild hearing impairment and needs training and counselling on how best to prevent further deterioration. No referral is warranted. |

| 3. Poor hearing. Hearing within 5th percentile, i.e. hearing level normally experienced by 1 person in 20. Suggests significant NIHL | Sum of hearing levels at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6kHz. Compare value with figure given for appropriate age band and gender in standardized tables. | Referral. This means that the employee has hearing worse than would be expected for their age and referral to an occupational physician, audiologist or an ENT specialist for further evaluation is indicated. |

| 4. Rapid hearing loss. Reduction in hearing level of 30 dB or more, within 3 years or less. Such a change could be caused by noise exposure or disease. | Sum of hearing levels at 3, 4 and 6kHz. | Referral. This means that the employee has hearing worse than would be expected for their age and referral to an occupational physician, audiologist or an ENT specialist for further evaluation is indicated. This type of deterioration could be due to noise or disease. |

All audiograms were produced by Interacoustics model AS216 audiometers calibrated to the British standard BS EN 60445-1. The audiometry booths were calibrated according to the South African standard SANS 10182 and the audiometry testing procedures were based on the South African Standard SANS 10083:2004, which requires the use of a soundproof booth and no exposure to noise for 24h prior to the test.

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Manchester Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health ethics committee.

Results

A total of 246 audiograms were studied. The study population was almost entirely male (98%). The prevalence of NIHL was 47%, with 35% exhibiting mild hearing impairment and 12% poor hearing. The largest proportion of study participants (56%) were in the 30–39 age group (Table 3). The largest proportion of participants (41%) had 6–10 years’ exposure and the smallest (18%) had >10 years’ exposure.

Table 3.

Summary of study data showing gender, age, exposure and level of hearing impairment

| Age in years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | >50 | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 40 (16) | 139 (56) | 56 (23) | 8 (3) |

| Female | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Years of exposure, n (%) | ||||

| 1–5 | 27 (11) | 61 (25) | 9 (4) | 1(0.4) |

| 6–10 | 13 (5) | 64 (26) | 23 (9) | 2 (0.8) |

| >10 | 3 (1) | 14 (5) | 24 (10) | 5 (2) |

| Hearing impairment, n (%) | ||||

| Acceptable hearing | 17 (7) | 72 (29) | 38 (15) | 4 (2) |

| Mild impairment | 19 (8) | 52 (21) | 11 (4) | 3 (1) |

| Poor hearing | 7 (3) | 15 (6) | 7 (3) | 1 (0.4) |

| Years of exposure | Category of hearing loss | |||

| Acceptable hearing | Mild hearing impairment | Poor hearing | ||

| 1–5, n (%) | 57 (23) | 36 (15) | 5 (2) | |

| 6–10, n (%) | 61 (25) | 33 (13) | 8 (3) | |

| >10, n (%) | 13 (5) | 16 (6) | 17 (7) | |

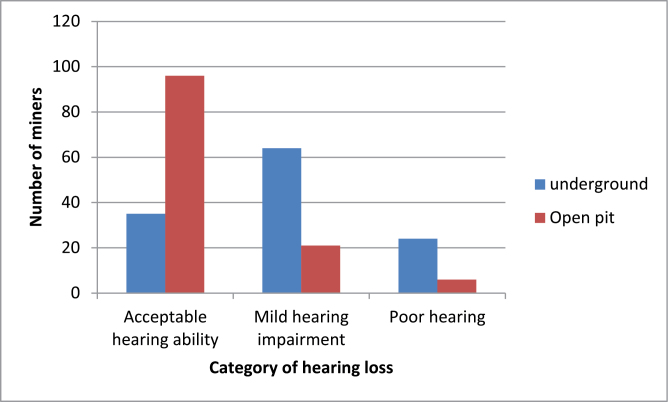

Approximately 70% of participants had a history of prior occupational noise exposure and 51% of these had NIHL. This group also had a higher proportion (17%) of individuals categorized as having poor hearing (χ 2 = 12, P < 0.05). Only 2 (1%) of the 246 study participants were aware of having had a hearing problem in the past. Among underground miners, 72% had NIHL, 52% with mild hearing impairment and 20% with ‘poor hearing’. Among open pit miners, 22% had NIHL with 17% having mild hearing impairment and 5% ‘poor hearing’, a statistically significant difference between these two occupational groups (χ 2 = 61, P < 0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hearing loss category according to type of mining.

The youngest age group (20–29) had the highest proportion with NIHL (60%), followed by those aged 50 and above (50%). The group with the smallest proportion affected was aged 40–49 (32%), although these differences were not statistically significant. The group with >10 years’ exposure was most affected (72%) and also had the highest proportion of individuals with poor hearing (37%) (χ 2 = 36, P < 0.05). Eighty per cent of subjects operated mobile equipment as a core duty. Of this group, 41% had NIHL. In the group that did not operate mobile equipment 70% were affected, with 20% exhibiting poor hearing (χ 2 = 14, P < 0.05).

Discussion

There was a high prevalence (47%) of NIHL among miners in this study with mild hearing impairment in 35% and poor hearing in 12%. A higher proportion of underground workers were affected and the youngest age group had the highest proportion of miners with NIHL.

Among the strengths of the study is that audiograms were taken by qualified technicians using recognized protocols on calibrated equipment. Its limitations, however, included a lack of representative samples for all age groups. The prevalence of NIHL was higher than that seen in similar studies and this could be attributed to the different categorization systems used. For instance, the Zimbabwean nickel mine study used the American National Standard C29 CFR 1910.95, which may have excluded individuals with longstanding disability and loss of the classical notch. Similarly, the HSE categorization scheme may include hearing loss due to other causes as it ignores the notch.

There was a NIHL prevalence of 51% among those with history of work in a noisy industry compared to 36% among those without. This was similar to the findings of the Ghanaian study by Amedofu et al. [4]. The age distribution was similar to the Zimbabwean study with the greatest number of individuals in the 30–39 age group (56%). There were very few individuals in the over 50 age group, demonstrating that mining in Tanzania is in its infancy. The inference from other data that men are more affected by NIHL may be a result of population bias in an almost all male industry (Table 3).

The finding of a 1% prevalence of a history of pre-existing hearing problems is within the range of external ear infection prevalence found in Berger’s analysis [14], which implied that infections and other disease processes do not contribute significantly to hearing loss in occupationally noise-exposed populations.

Of those affected by NIHL 67% were from the underground mine. This is in keeping with literature documenting greater noise exposure in underground mines. Significantly, more underground miners (71%) had NIHL than open pit miners (22%).

The youngest age group (20–29) had the highest prevalence of hearing impairment (60%). These findings are not consistent with a review of previous literature, in which NIHL prevalence increased with age. However, in the study of South African gold miners, the youngest age group (aged under 29) had a mean pure tone threshold of hearing 2 dB higher than the older 30–39 age group at the frequencies examined [9]. This could be due to the less mechanized mining methods used to induct new and younger miners. Further studies are required to examine this finding as it conflicts with other studies, although the differences in prevalence between age groups were not statistically significant.

The largest proportion of workers had a total exposure of 6–10 years and the smallest (18%) >10 years. Subjects in the Zimbabwean and South African studies had longer durations of exposure [5,8]. There was a greater NIHL prevalence (72%) among those with >10 years’ exposure. There was little difference in NIHL prevalence between those with 1–5 and 6–10 years’ exposure (42 and 40%, respectively). The greatest proportion of those with poor hearing (37%) occurred in subjects with >10 years’ exposure. With the exception of the similar NIHL prevalence between 1–5 and 6–10 years’ exposure these results are consistent with all studies reviewed. The results show a higher NIHL prevalence (70%) among miners not operating mobile equipment, probably because miners who operate mobile equipment as their core duty are exposed to noise of lower intensity (Table 3).

Although the company provides an array of hearing protection devices the high prevalence may suggest poor compliance with their use. The study’s findings highlight the need for comprehensive hearing conservation programmes that involve systematic ally classifying audiograms leading to a well-defined process to assist workers affected by NIHL, coupled with effective primary prevention measures. If progressive NIHL is to be prevented, clinicians should at every opportunity classify and interpret audiograms so as to ensure appropriate intervention to prevent deteriorating NIHL.

Further studies to verify the finding of the highest prevalence of NIHL in the youngest age group and determine the reasons for this would provide valuable insight. Additional studies to assess miners’ knowledge of NIHL and attitudes to the use of hearing protection would also provide useful information.

Key points

This study found a high prevalence of noise-induced hearing loss among Tanzanian miners, with underground miners affected more than open pit miners.

The findings suggest that the Health & Safety Executive audiogram classification system can be used to identify noise-induced hearing loss and consequently guide appropriate intervention.

In industries undertaking periodic audiometry to screen for developing noise-induced hearing loss there is a need to classify audiograms using a simple, practical tool with clear protocols for resulting actions.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. MacDonald C, Roe A.Tanzania Case Study. International Council on Mining and Minerals, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Mining (Safety Occupational Health and Environment) Regulations 2010, 211(2).

- 3. The Occupational Health and Safety Act 2003, 5.

- 4. Amedofu KG. Hearing impairment among workers in a surface gold mining company in Ghana. Afr J Health Sci 2002;9:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hessel PA, Sluis-Cremer GK. Hearing loss in white South African goldminers. S Afr Med J 1987;71:364–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kurmis PA, Apps AS. Occupationally acquired noise induced hearing loss: a senseless workplace hazard. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2007;20:127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McBride ID. Noise induced hearing loss and hearing conservation in mining. Occup Med (Lond) 2004;54:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edmore M.The Prevalence of Noise Induced Hearing Loss at a Nickel Mine in Zimbabwe. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Witwatersrand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edwards AK.Characteristics of Noise Induced Hearing Loss in Gold Miners. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ali A, Garandawa HI, Nwawolo CC, Somefun OO. Noise induced hearing loss in a cement company, Nigeria. Online J Med Med Sci Res 2012;1:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Obiako MN. Deafness and the mining industry in Zambia. East Afr Med J 1979;56:445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health & Safety Executive. Controlling Noise at Work. 2nd edn. London, UK: HSE Books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheesman M, Steinberg P. Health surveillance for noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Occup Med (Lond) 2010;60:576–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berger EH. EARlog#17—ear infection and the use of hearing protection. J Occup Med 1985;27:620–623. [Google Scholar]