Abstract

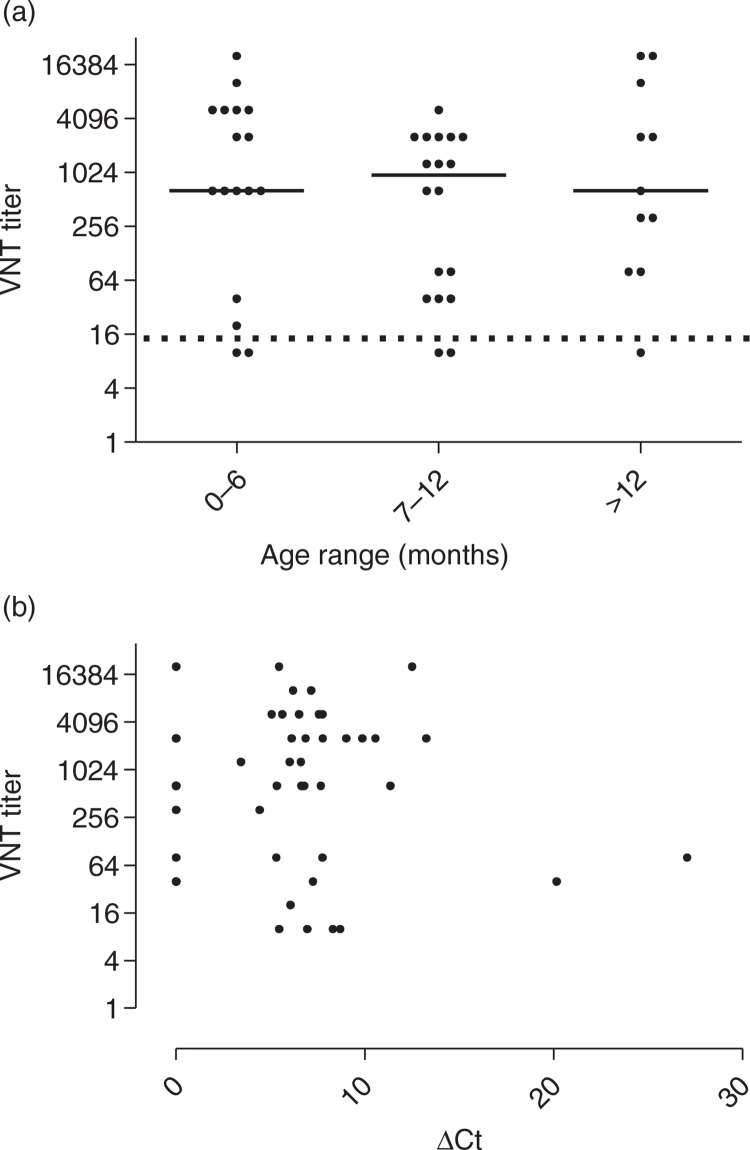

Two of the earliest Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) cases were men who had visited the Doha central animal market and adjoining slaughterhouse in Qatar. We show that a high proportion of camels presenting for slaughter in Qatar show evidence for nasal MERS-CoV shedding (62/105). Sequence analysis showed the circulation of at least five different virus strains at these premises, suggesting that this location is a driver of MERS-CoV circulation and a high-risk area for human exposure. No correlation between RNA loads and levels of neutralizing antibodies was observed, suggesting limited immune protection and potential for reinfection despite previous exposure.

Keywords: zoonoses, camels, MERS-CoV, respiratory infections

Dromedary camels are likely the primary source of Middle East respiratory syndrome virus (MERS-CoV) infection in humans, but further evidence is needed to support their role in zoonotic transmission. Two of the earliest diagnosed cases in Qatar were men who had visited the Doha central animal market and the adjoining central slaughterhouse (Farag, pers. comm.). Therefore, pre- and postmortem sampling was conducted on dromedary camels (n=105) at the central slaughterhouse in Doha, Qatar. Nasal, oral, and rectal swabs collected prior to slaughter were tested for the presence of MERS-CoV RNA. Most of the camels that were sampled showed evidence for MERS-CoV shedding at the time of slaughter (59%). Sequence analysis showed the circulation of at least five different virus strains at the slaughterhouse premises. An understanding of the extent and pattern of MERS-CoV shedding by dromedaries presenting for slaughter provides insight into the risks for MERS-CoV exposure of persons with occupational contact with live camels and their carcasses.

Background

Illness associated with infection with MERS-CoV is characterized primarily by mild-to-severe respiratory complaints, most requiring hospital admission for pneumonitis or acute respiratory distress syndrome. As of June 11, 2015, ECDC has reported 1,288 laboratory-confirmed cases, including 498 deaths (1). Human-to-human transmission seems limited to family and health care settings. Overall, a large proportion of MERS cases is suspected to be a result of zoonotic transmission (1) with growing evidence for dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) as a reservoir. MERS-CoV-specific antibodies have been detected in camels across the Middle East and the African continent, suggesting a geographically widespread distribution (2). Analysis of an outbreak associated with a barn in Qatar found dromedaries and humans to be infected with nearly identical strains of MERS-CoV (3) and further support for camels as reservoir came from a study in Saudi Arabia (KSA) that found widespread circulation of different genetic variants of MERS-CoV in camels, with geographic clustering of human and camel MERS-CoV sequences (4). However, few other studies provided evidence for zoonotic transmission of MERS-CoV from camels (5). The routes of direct or indirect zoonotic transmission are yet unknown. We investigated the rate of MERS-CoV circulation in dromedaries at the slaughterhouse in Qatar, previously linked to two MERS cases in Qatar.

MERS virus shedding at slaughterhouse

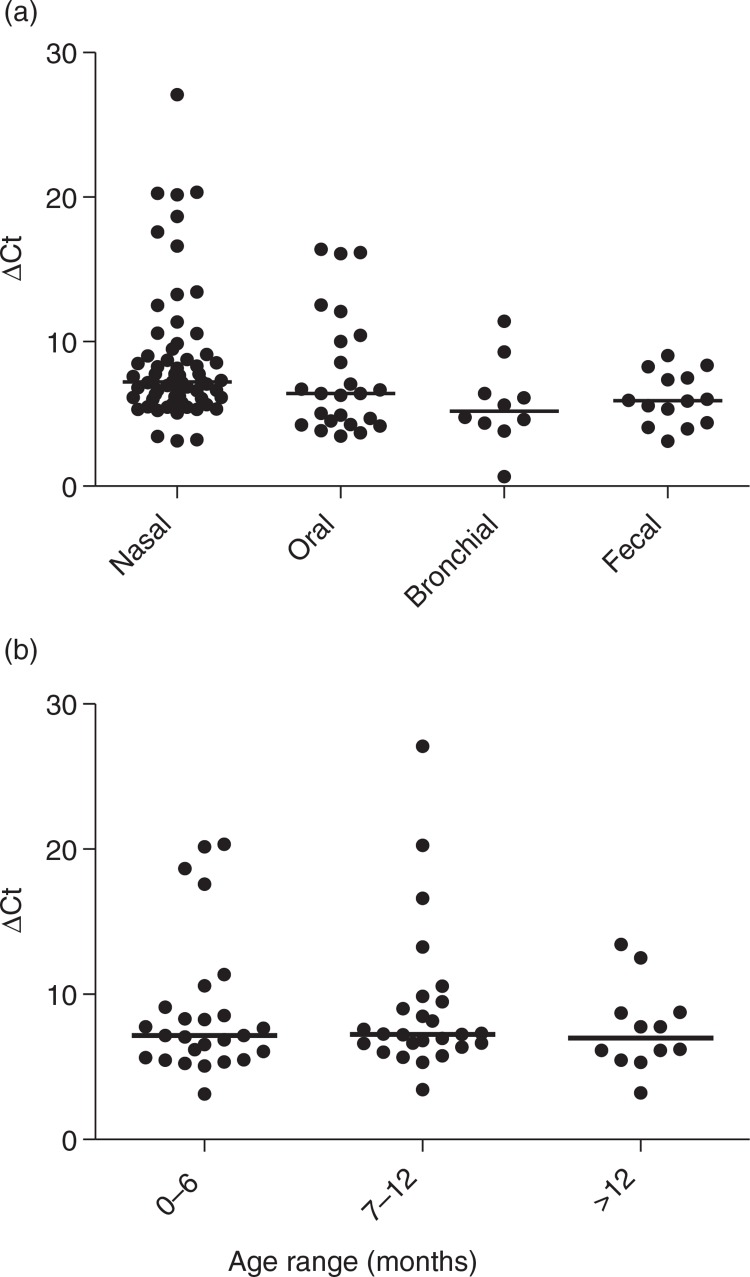

A random group of 105 camels that presented for slaughter in February (n=53) and March (n=52) 2014 were sampled for MERS-CoV analysis (Table 1). Animals either had come directly from within Qatar or KSA, or had been sold through the central animal market (CM). Swabs and lymph nodes were tested for MERS-CoV RNA by internally controlled RT-PCR targeting UpE and N genes, as described (3, 6). The first camel isolate of MERS-CoV as described by Raj et al. (7) was obtained from the first group of 53 samples and among others sequences generated from this group have been used to define a general MERS-CoV typing fragment (8). In total, 59% of the camels showed evidence for virus shedding in at least one type of swab at the time of slaughter (Table 1). The percentage positive samples was the highest for nasal samples, followed by oral swabs, fecal swabs, and bronchial swabs. All but one animals with virus shedding from any sample had a positive nasal swab. For saliva (oral), the percentage of positive samples was the highest for animals between 7 and 12 months of age. Lymph nodes from 53 animals were tested, yielding five positives. Approximation of the viral loads in the samples using the Ct values obtained with the UpE target showed no significant differences between types of samples and age groups (Fig. 1) It should be noted that viral loads with ΔCt>20 were observed only in the nasal swabs and the nasal swab sample with the highest viral load was found to contain infectious virus (7).

Table 1.

MERS-CoV detection in pre- and postmortem samples from camels presented for slaughter in Doha, Qatar (n=105)

| Sample type | All (n=105) | 0–6 months (n=41) | 7–12 months (n=35) | >1 years (n=29) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | 60 (61/101)a | 63 (24/38) | 74 (26/35) | 39 (11/28) |

| Oral | 23 (23/102) | 18 (7/39) | 35 (12/34) | 14 (4/29) |

| Rectal | 15 (15/103) | 15 (6/39) | 17 (6/35) | 10 (3/29) |

| Bronchial | 7 (7/101) | 8 (3/38) | 6 (2/34) | 7 (2/29) |

| Lymph nodes | 9 (5/53) | 0 (0/19) | 20 (4/20) | 7 (1/14) |

Percentage positive for MERS-CoV RNA as detected by two RT-PCR targets, followed by (absolute number of samples positive/ total number tested).

Fig. 1.

MERS-CoV RNA shedding by dromedary camels at the central slaughterhouse, Qatar, depicted by sample type (a) and age group for nasal swabs (b). Viral loads in samples are approximated using Ct values obtained with the Up-E target and are expressed as ΔCt (40-Ctsample). Black lines indicate medians.

Diversity in MERS-CoV circulation

To obtain further insight in the diversity of the viruses that circulated in dromedary camels at the slaughterhouse, MERS-CoV strains were sequenced according to a recently developed technique that enables the identification of divergent MERS-CoV types [sequences and technique in (8)]. In total, five different sequence types were identified with three different types found at both sampling moments (Table 2). Camels either came from the large Al-Shahaniya international racing complex (ASH) or from different sources elsewhere in Qatar (indicated by the initial arrow for animals 6–8 and 10–12 in (Table 2). Subsequently, they were either brought to a showing area (Al Mazad, AM), to the barns at the CM for a holding period, or immediately sent to the slaughterhouse (SH). Therefore, the sampling for animals 1–5 and 9–13 reflects MERS-CoV sequence diversity as a result of import from other regions in Qatar, whereas virus circulation at the CM more likely explains the virus diversity for animals 6–8.

Table 2.

Summary of background information from slaughter camels for which sequences could be obtained from nasal swabs

| Animal ID # | Origin | Age | Sampling moment | Sequence type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ASH→AM→SH | 6 months | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | ASH→AM→SH | 6 months | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | ASH→AM→SH | 6 months | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | ASH→AM→SH | 8 months | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | ASH→AM→SH | 7 months | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | →CM→SH | 6 months | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | →CM→SH | 6 months | 1 | 3 |

| 8 | →CM→SH | 8 months | 1 | 3 |

| 9 | ASH→SH | 2 years | 1 | 3 |

| 10 | →AM→CM | 6 months | 2 | 3 |

| 11 | →AM→CM | 10 month | 1 | 4 |

| 12 | →AM→CM | 6 months | 2 | 4 |

| 13 | ASH→SH | 8 months | 2 | 5 |

ASH=Al-Shahaniya, AM=Al Mazad, SH=slaughterhouse, CM=central market.

Serology

Antibodies to MERS-CoV S1 were found in 100 out of 103 animals tested by micro-array technology (9). For 53 animals, antibody levels were also determined by virus neutralization assay as described earlier (9). Almost all animals had detectable neutralizing antibodies with no obvious age pattern and no significant difference in proportion of animals with low antibody levels (<20) (Fig. 2a) . There was no correlation between antibody levels and the viral load as reflected by Ct values (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Reciprocal MERS-CoV-neutralizing antibodies titers by age group (a) and correlated with ΔCt (40-Ctsample) (b) for 53 camels at central slaughterhouse, Qatar.

Discussion

A high proportion of dromedary camels shed MERS-CoV RNA when presented for slaughter on two occasions at the central abattoir in Qatar. Co-circulation of multiple MERS-CoV variants demonstrates multiple virus introductions through flow of new animals traded into this group of animals, reflecting the virus diversity in wider Qatar, including animals imported from Australia, the Middle East region and East Africa. This suggests that CM is a driver of MERS-CoV circulation and a high-risk site for human exposure. Indeed two cases in Qatar were linked to visits to this area, and serology data on the only five workers that exclusively work in camel slaughter in Qatar illustrated this potential burden as four of the five slaughterers had IgG antibodies specific for MERS-CoV (10)

A study at four slaughterhouses in Egypt showed an overall RNA prevalence in nasal swabs of 3.6% among 110 camels (11), which is significantly lower than in our study. A comparison of the organization of the meat markets between Egypt and Qatar could provide insight in the observed differences. The camels that are put together for a holding period of weeks prior to slaughter in Doha have a wide variety of origins with varying initial immune status, which might provide a platform for extensive virus circulation. These include naïve camels from Australia (12) and camels from areas in the Horn of Africa and the Gulf region with known differences in immune status (2, 13, 14). We observed a positivity rate in rectal swabs of 15 out of 103 animals that were analyzed (of which 61 were positive in nasal swabs). Other studies observed none to very low numbers of camels shedding MERS-CoV RNA in feces (3, 15). However, the total numbers of animals in these studies were too low to make a significant comparison with the data presented here. In the current views on MERS-CoV epidemiology, young camels (≤1year) with primary infections are thought to play a bigger role in MERS-CoV transmission than older animals for which less frequent shedding is observed (4, 15) and who demonstrate higher rates of seroconversion (reviewed in (Ref. 2). However, we observed no significant differences in MERS-CoV RNA shedding between different age groups. Moreover, the lack of correlation between viral RNA loads and levels of neutralizing antibodies in the animals suggests limited protection and potential for reinfection despite previous exposure, similar to the situation in humans with the four common human CoVs and as observed in a camel herd in KSA (15). A problem is that the time since onset of infection could not be determined as the animals did not show overt symptoms. Therefore, it remains to be determined how the kinetics of infection are. In theory, the observed shedding of virus in the presence of neutralizing antibodies could represent sampling toward the end of an infection cycle. Alternatively, the data may reflect limited mucosal immunity as has been shown for other animal coronaviruses (16). The possibility of camel vaccination has been suggested as a possible approach to controlling MERS-CoV transmission to humans. However, this may prove to be a challenging task in light of the above observations.

Given the high numbers of animals shedding these viruses in dynamic environments like the Doha market and abattoir, potential human health risks need to be considered and the implementation of management alternatives (e.g. separation of naïve animals from previously exposed animals and personal protective equipment for employees) might reduce the burden of MERS-CoV exposure to humans.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Berend-Jan Bosch for supply of antigens for micro-array testing. Samples were collected according to national regulations with regard to animal health and welfare under the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), permit number 2014-01-001. All animal samples were transported in agreement with Dutch import regulations with regard to animal disease legislation.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.ECDC. Severe respiratory disease associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – seventeenth update, 11 June 2015. Stockholm: ECDC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackay IM, Arden KE. Middle East respiratory syndrome: an emerging coronavirus infection tracked by the crowd. Virus Res. 2015;202:60–88. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haagmans BL, Al Dhahiry SH, Reusken CB, Raj VS, Galiano M, Myers R, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:140–5. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70690-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alagaili AN, Briese T, Mishra N, Kapoor V, Sameroff SC, de Wit E, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia. MBio. 2014;5:e00884–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00884-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Memish Z, Cotton M, Meyer B, Watson S, Alsahafi A, Al Rabeeah A, et al. Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1012–15. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corman VM, Eckerle I, Bleicker T, Zaki A, Landt O, Eschbach-Bludau M, et al. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro Surveill. 2012;17 doi: 10.2807/ese.17.39.20285-en. pii: 20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raj VS, Farag E, Reusken CB, Lamers MM, Pas SD, Voermans J, et al. Isolation of MERS coronavirus from a dromedary camel, Qatar, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1339–42. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.140663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smits SL, Raj VS, Pas SD, Reusken C, Mohran KA, Farag E, et al. Reliable typing of MERS-CoV variants with a small genome fragment. J Clin Virol. 2015;64:83–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Muller MA, Gutierrez C, Godeke GJ, Meyer B, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:859–66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reusken CBEM, Farag EABA, Haagmans BL, Mohran KA, Godeke G-J, Raj VS, et al. Occupational exposure to dromedaries and risk for MERS-CoV infection, Qatar, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21 doi: 10.3201/eid2108.150481. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2108.150481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu DKW, Poon LLM, Gomaa MM, Shehata MM, Perera RAPM, Zeid DA, et al. MERS coronaviruses in dromedary camels, Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1049–53. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemida MG, Perera RA, AlJassim RA, Kayali G, Siu LY, Wang P, et al. Seroepidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus in Saudi Arabia (1993) and Australia (2014) and characterisation of assay specificity. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:20828. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.23.20828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corman VM, Jores J, Meyer B, Younan M, Liljander A, Said MY, et al. Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, Kenya, 1992–2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1319–22. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.140596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemida MG, Perera RA, Wang P, Alhammadi MA, Siu LY, Li M, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20659. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.50.20659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemida MG, Chu DKW, Poon LLM, Perera RAPM, Alhammadi MA, Ng H, et al. MERS Coronavirus in Dromedary Camel Herd, Saudi Arabia 2014. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140571. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2007.140571 [cited 15 April 2014]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saif LJ. Animal coronavirus vaccines: lessons for SARS. Dev Biol (Basel) 2004;119:129–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]