Background: Imbalanced TGFβ/BMP-mediated signaling has been identified as a principal stimulus of EndMT.

Results: The EndMT master regulator SNAIL is a direct target of HIF1α.

Conclusion: Hypoxia-induced EndMT is mediated by HIF1α through direct targeting of SNAIL.

Significance: This study provides conceptual clues of how endothelial cells undergoing EndMT relate to tip cells associated with sprouting angiogenesis in response to hypoxia.

Keywords: endothelial cell, fibroblast, fibrosis, hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)

Abstract

Endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndMT) was originally described in heart development where the endocardial endothelial cells that line the atrioventricular canal undergo an EndMT to form the endocardial mesenchymal cushion that later gives rise to the septum and mitral and tricuspid valves. In the postnatal heart specifically, endothelial cells that originate from the endocardium maintain increased susceptibility to undergo EndMT as remnants from their embryonic origin. Such EndMT involving adult coronary endothelial cells contributes to microvascular rarefaction and subsequent chronification of hypoxia in the injured heart, ultimately leading to cardiac fibrosis. Although in most endothelial beds hypoxia induces tip cell formation and sprouting angiogenesis, here we demonstrate that hypoxia is a stimulus for human coronary endothelial cells to undergo phenotypic changes reminiscent of EndMT via a mechanism involving hypoxia-inducible factor 1α-induced activation of the EndMT master regulatory transcription factor SNAIL. Our study adds further evidence for the unique susceptibility of endocardium-derived endothelial cells to undergo EndMT and provides novel insights into how hypoxia contributes to progression of cardiac fibrosis. Additional studies may be required to discriminate between distinct sprouting angiogenesis and EndMT responses of different endothelial cells populations.

Introduction

Endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndMT)4 refers to a cellular process through which endothelial cells delaminate from their organized layer and migrate away, possibly invading the surrounding connective tissue (1–3). The acquired mesenchymal phenotype is associated with increased expression of mesenchymal marker proteins such as α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen 1A1 (Col1A1) and decreased expression of typical endothelial markers such as CD31 (Pecam-1) and vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin. EndMT was originally described in heart development where the endocardial endothelial cells that line the atrioventricular canal undergo EndMT to form the endocardial mesenchymal cushion that later gives rise to the septum and mitral and tricuspid valves (4). Postnatal EndMT contributes to pathologies including cardiac fibrosis (5–10). Although it is not clear whether all endothelial cells can undergo EndMT, recent studies have suggested that among cardiac endothelial cells it is specifically endocardial endothelial cells and endothelial cells of endocardial origin (such as coronary endothelial cells) that can undergo EndMT possibly as remnants of their embryonic plasticity (11).

The molecular pathways that control EndMT involving embryonic and postnatal endothelial cells are still incompletely understood. Although an imbalance of TGFβ/bone morphogenetic protein-mediated signaling has been identified as a principal stimulus of EndMT, additional pathways such as Notch signaling can also induce EndMT (12–15). Several studies have implicated unequivocally that all inducers of EndMT culminate in an induction of at least one of the transcription factors Snail, Slug, and Twist (16). Because all three transcription factors also control various epithelial-mesenchymal transitions during embryogenesis and cancer progression, they have been highlighted as master regulators of cell plasticity, directly targeting numerous genes involved in cellular transitions (17–19).

Chronic hypoxia is a hallmark of cardiac fibrosis resulting from both rarefaction of microvessels (and subsequent oxygen supply) and increased oxygen consumption by activated inflammatory cells and fibroblasts (20). Chronic hypoxia itself contributes to aberrant ventricular remodeling and cardiac fibrosis (21). In this regard, a circulus vitiosus of hypoxia-induced EndMT contributing to microvascular rarefaction and subsequent chronification of hypoxia appears to be an attractive concept. Here we explored the possibility that EndMT associated with cardiac fibrosis could be a direct consequence of hypoxia independent of growth factors.

The effect of hypoxia on any given cell is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription factors that respond to changes in available oxygen in the cellular environment with HIF1α being the most abundant isoform. Intracellular levels of HIF1α under hypoxic conditions is caused by increased expression mostly through impaired proteolytic degradation: under hypoxic conditions, HIF1α is stabilized, dimerizes with HIF1β, and translocates into the nucleus where it can bind to hypoxia response elements within promoter regions of target genes and induce transcriptional activity. Once normoxia is restored, prolyl hydroxylase hydroxylates HIF1α, causing its association with the von Hippel Lindau tumor suppressor protein, ultimately causing ubiquitin-dependent degradation of HIF1α. Vhl-null mice in which HIFs accumulate independently of hypoxia due to impaired degradation develop spontaneous cardiac fibrosis (22), prompting us to explore the involvement of HIF1α in hypoxia-induced EndMT.

Here we aimed to elucidate a potential role for hypoxia in the induction of EndMT involving coronary endothelial cells. Our studies demonstrate that hypoxia can induce EndMT through HIF1 signaling independently of TGFβ and that Snail is a direct target of HIF1α.

Experimental Procedures

Animal Experiments

C57Bl6 or Tie1Cre;R26RstopYFP micestrains were maintained at the breeding facility of the University of Göttingen. The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication Number 85-23, revised 1996). The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Göttingen and the responsible government authority of Lower Saxony (Germany).

Ascending Aortic Constriction

Ascending aortic constriction was performed in 12-week-old mice under anesthesia with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) given at 0.1 ml intraperitoneally as described previously (10). Adequacy of anesthesia was monitored by observing muscle twitch and by tail pinch as well as documenting heart rate and body temperature. As postoperative analgesia, Buprenex (0.1 mg/kg) was given intraperitoneally every 6–8 h for the first 48 h. All mice used weighed 25–30 g. For sham control operated mice, the chest was surgically opened under the same conditions as banded mice except that no aortic banding was performed. 4 weeks after operation, mice were sacrificed with a lethal intraperitoneal dose of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) followed by cervical dislocation.

Cell Culture and Immunofluorescence Staining

Human coronary artery endothelial cells (Genlantis) were grown in human coronary artery endothelial cell (HCAEC) culture medium (Genlantis) and passaged according to the company's instructions. At the fifth passage, 1 × 106 cells were seeded into 10-cm plates (Griner), after 18–24 h of attachment supplied with fresh medium, and incubated for an additional 72–96 h at normoxic or hypoxic conditions. For hypoxic conditions, cells were cultured in a gas mixture containing 1% O2 in a hypoxia chamber (STEMCELL Technologies) following the protocol as described elsewhere (23, 24) or treated in medium containing 400 μm CoCl2 (Sigma). To block the synthesis of HIF1α, 100 nm digoxin (Sigma) was prior added into the medium before placed into a hypoxia chamber. For immunofluorescence staining, cells were seeded onto four-chamber culture slides (BD Falcon) after treatment with hypoxia and then fixed with ice-cold methanol/acetone (1:1) for 10 min at −20 °C followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and then blocking with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with primary antibody CD31 (1:100; Dako) or α-SMA (1:100; Abcam) for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were washed with cold PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled anti-rabbit (1:300) and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-mouse (1:300) secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) at room temperature for 1 h. The cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope and AxioVision 3.0 software. The acquired imaged were processed using Photoshop CS3 software.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Ascending aortic constriction banded mouse hearts were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 3 μm, then deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in ethanol containing distilled water. Masson's trichrome staining was performed as described previously (10). Immunohistochemistry were performed using carbonic anhydrase IX antibody (sc-25599, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) peroxidase-labeled with the Vectastain Universal Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). 3-Amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate chromogen (Dako) was used for peroxidase visualization according to the manufacturer's protocol. Mayer's hematoxylin solution (Sigma) was used for visualizing the cell nucleus.

RNA Extraction and Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells or tissues using a PureLink RNA kit (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's protocol. 1 μg of total RNA was digested with DNase I (Sigma) and used for cDNA synthesis using the SuperScriptII system (Life Technologies). Diluted cDNA (1:10) was used as a template in Fast SYBR Master Mix (Life Technologies) and run on a StepOne Plus real time PCR system (Life Technologies) with real time PCR primers (sequences are listed in Table 1). Measurements were standardized to the GAPDH reaction using ΔΔCt methods.

TABLE 1.

qRT-PCR primer sequence

F, forward; R, reverse.

| Gene | Sequence | Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| COL1A1 | F: AGACAGTGATTGAATACAAAACCA | Primerdesign, Southampton, UK |

| R: GGAGTTTACAGGAAGCAGACA | ||

| GAPDH | Undisclosed | Primerdesign |

| SLUG | F: ACTCCGAAGCCAAATGACAA | Primerdesign |

| R: CTCTCTCTGTGGGTGTGTGT | ||

| SNAIL | F: GGCAATTTAACAATGTCTGAAAAGG | Primerdesign |

| R: GAATAGTTCTGGGAGACACATCG | ||

| α-SMA | F: AAGCACAGAGCAAAAGAGGAAT | Primerdesign |

| R: ATGTCGTCCCAGTTGGTGAT | ||

| DDR2 | F: GGAGGTCATGGCATCGAGTT | Eurofins MWG Operon (Ford et al. (40)) |

| R: GAGTGCCATCCCGACTGTAATT | ||

| FSP1 | F: TCTTTCTTGGTTTGATCCTGACT | Primerdesign |

| R: AGTTCTGACTTGTTGAGCTTGA | ||

| CD31 | F: AAGGAACAGGAGGGAGAGTATTA | Primerdesign |

| R: GTATTTTGCTTCTGGGGACACT | ||

| VE-cadherin | F: GCACCAGTTTGGCCAATATA | Eurofins MWG Operon (Kiran et al. (41)) |

| R: GGGTTTTTGCATAATAAGCAGG | ||

| VWF | F: GGGGTCATCTCTGGATTCAAG | Primerdesign |

| R: TCTGTCCTCCTCTTAGCTGAA | ||

| TWIST | F: CTCAAGAGGTCGTGCCAATC | Primerdesign |

| R: CCCAGTATTTTTATTTCTAAAGGTGTT |

Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

Proteins were extracted from cells and tissues using Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (Life Technologies) containing protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Protein samples were resolved by 4–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences). After blocking with 5% dry milk in TBST (TBS, pH 7.2, 0.1% Tween 20), the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies (details and dilution factors are listed in Table 2) at 4 °C overnight. On the 2nd day, after washing three times with 2% dry milk in TBST, the membrane was incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology), and signals were detected using a chemiluminescence kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

TABLE 2.

Antibodies

IF, immunofluorescence; PE, phycoerythrin.

| Antibody | Product code | Dilution | Company |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIF1α | PA1-16601 | 1:1000 | Thermo Scientific |

| HIF1α | MA1-16504 | 1:50 (IF) | Life Technologies |

| VE-cadherin | 2158 | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| α-SMA | Ab32575 | 1:1000 | Abcam |

| β-Actin | A5316 | 1:5000 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| FSP1 | HPA007973 | 1:1000 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| CD31 | 553370 | 1:1000 | BD Pharmingen |

| CD31 (PE-labeled) | 560983 | 1:100 | BD Pharmingen |

| SNAIL | ab180714 | 1:100 | Abcam |

| SLUG | AB27568 | 1:1000 | Abcam |

| α-Tubulin | Sig T5168 | 1:5000 | Sigma-Aldrich |

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were performed with a OneDay ChIP kit (Diagenode) and followed the protocols as described previously (25). Briefly, cells were first cross-linked and then lysed with a shearing kit (Diagenode) followed by sonication (Misonix). The sheared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with 5 μg of DDK antibody (OriGene) or with IgG as a negative control (Diagenode) using the Diagenode OneDay ChIP protocol. Quantitative analysis of the immunoprecipitated DNA was performed using the StepOne Real-Time System (Applied Biosystems) using two pairs of primers (sequences are listed in Table 3) flanking the human SNAIL promoter region and one pair of primers flanking exon 2 as a negative control. The ChIP-quantitative PCR data were analyzed using the ΔCt method in which the immunoprecipitated sample Ct value was normalized with the input DNA Ct value, and the percentage of precipitation was calculated using the following formula: % input = 2−(Ct immunoprecipitated − Ct input) × dilution factor × 100%.

TABLE 3.

ChIP-quantitative PCR primer sequences

| Name | Sequence | Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| hSnailChip_P1F | GGAGACGAGCCTCCGATT | Eurofins MWG Operon |

| hSnailChip_P1R | GCCGCCAACTCCCTTAAGTA | Eurofins MWG Operon |

| hSnailChip_P2F | GCGAGCTGCAGGACTCTAAT | Eurofins MWG Operon |

| hSnailChip_P2R | GTGACTCGATCCTGGCTCA | Eurofins MWG Operon |

| hSnailChip_ngF | GCTCCTTCGTCCTTCTCCTC | Eurofins MWG Operon |

| hSnailChip_ngR | GAGATCCTTGGCCTCAGAGA | Eurofins MWG Operon |

Transfection

For transfection experiments, cells were plated onto 10-cm plates (Griner), cultured overnight, and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the plasmid DNA (2 μg each) and Lipofectamine 2000 were mixed in a ratio of 1:2 in a total volume of 500 μl of Opti-MEM (Life Technologies) and allowed to form the complex by incubating for 20 min at room temperature. Then the DNA-Lipofectamine complex was added to the cells in endothelial basic medium (Genlantis). After 3 h of incubation, the medium was replaced by growth medium, and then the cells were subjected to hypoxic conditions. For the gene silencing experiment, pLKO.1 vector was used for generating pLKO.1-shHIF1α and pLKO.1-shSNAIL constructs (shRNA oligo sequences are listed in Table 4). For gene overexpression, pCMV6-HIF1α (RC202461) and pCMV-HIFAN (RC202843) were purchased from OriGene.

TABLE 4.

shRNA targeted sequences

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| shRNA_HIF1α_A | AGCTTGCTCATCAGTTGCCACTTCCACAT |

| shRNA_HIF1α_B | AGGCCACATTCACGTATATGATACCAACA |

| shRNA_SNAIL | CAAGATGCACATCCGAAGCCACACGCTGC |

Cloning of SNAIL Promoter and Luciferase Reporter Assay

For generating a SNAIL promoter construct, a 1.6-kb fragment (−1638 to +12 bp) located 5′ upstream of the SNAIL coding sequence (26) was amplified using human HCAEC genomic DNA. The fragment was sequenced before being cloned in the KpnI/HindIII sites of pGL4.10 vector. Luciferase reporter assays were performed as described previously (27). Briefly, 1 day before transfection, cells were seeded (1 × 105 cells/well) to a 6-well plate. The next day, the cells were transiently transfected in duplicates with the indicated luciferase vectors, and 2 μg of the reporter plasmid pGL4.10_SNAIL or empty vector pGL4.10 (Promega) was co-transfected with 0.2 μg of pGL4.73 (Promega), a Renilla control vector for normalization of transfection efficiencies. The cells were lysed and assayed using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega).

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative PCR data for RNA expression analysis (two or more biological replicates) were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. One-way ANOVA (multiple group analysis) and Student's t test (GraphPad Prism 5.1) were used to obtain calculations of statistical significance.

Results

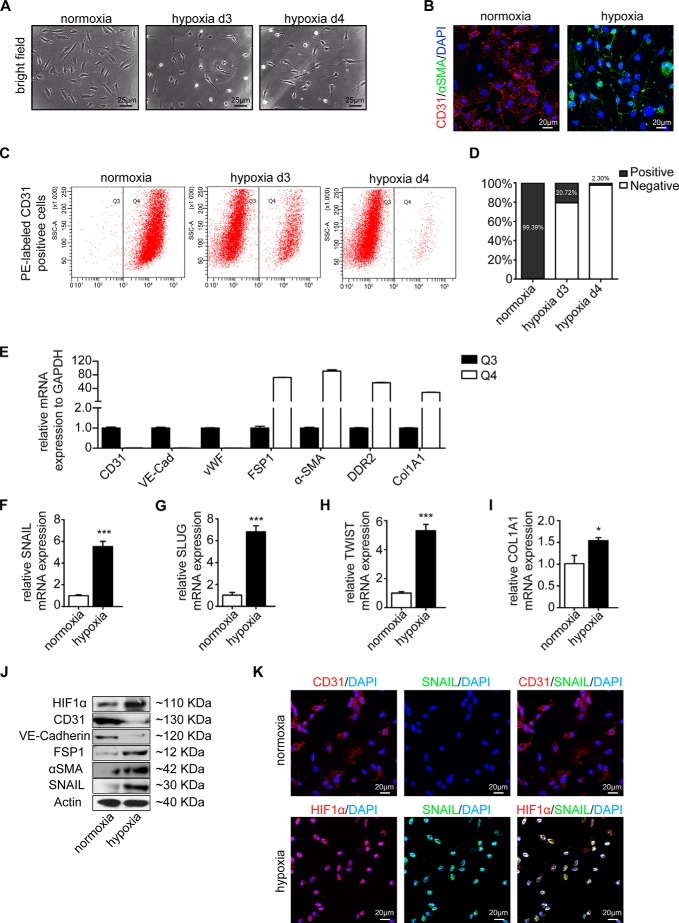

Upon cultivation in hypoxic conditions for 4 days, HCAECs acquired an elongated spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 1A) associated with acquisition of α-SMA and decreased CD31 expression (Fig. 1B) typical of EndMT (8). In response to hypoxia, cells progressively lost expression of CD31 (Fig. 1, B–D), and loss of CD31 expression corresponded reciprocally with increased expression of mesenchymal markers collagen 1A1, fibroblast -specific protein 1 (FSP1), α-SMA, and discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2), whereas other endothelial cell markers, VE-cadherin and von Willebrand factor (VWF), were similarly down-regulated (Fig. 1E). Overall, principal EndMT transcription factors SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST as well as collagen 1A1 were up-regulated under hypoxia (Fig. 1, F–J), suggesting that hypoxia elicits phenotypic changes reminiscent of EndMT in HCAECs.

FIGURE 1.

Hypoxia triggers endothelial to mesenchymal transition. A, representative bright field images showing the morphology of human coronary artery endothelial cells cultured under either normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 3 and 4 days (d). Hypoxic cells showed fibroblast-like phenotypes. Scale bars, 25 μm. B, representative immunofluorescence images showing CD31 (red) and α-SMA (green) staining in normoxic (left panel) and hypoxic cells (right panel); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Acquisition of a spindle-shaped morphology upon hypoxia exposure correlated with α-SMA acquisition and loss of CD31. Scale bars, 20 μm. C, cells exposed to normoxia (left panel), 3-day hypoxia (middle panel), or 4-day hypoxia (right panel) condition were sorted by FACS according to CD31 expression. CD31 protein was labeled with phycoerythrin (PE) (red) (x axis). In the normoxia condition, CD31+ cells were most prominent (gate Q4). This population was decreased in the hypoxia condition in favor of CD31− cells (gate Q3). D, quantification of CD31+ and CD31− cells exposed to normoxia and hypoxia. E, cells from gates Q3 and Q4 of 4-day hypoxia exposure were sorted and compared by quantitative real time PCR analysis. Expression of mRNAs encoding the endothelial markers (CD31, VE-cadherin (VE-Cad), and VWF) and mesenchymal markers (FSP1, α-SMA, DDR2, and collagen 1A1) in the CD31− (Q3) cell population is shown compared with their expression in the CD31+ (Q4) cell population. F–I, qRT-PCR data showing the mRNA expression levels of EndMT transcription factors (SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST) and COL1A1 in normoxic and hypoxic cells. EndMT transcription factors and COL1A1 were significantly induced in endothelial cells upon hypoxia conditions. Results were normalized to reference gene GAPDH (expression is presented as mean value; error bars represent S.D.; n = 3; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). J, Western blots showing expression of HIF1α, CD31, VE-cadherin, FSP1, α-SMA, and SNAIL in normoxic and hypoxic cells. All blots were reprobed with an anti-actin antibody as a control for equal loading. Hypoxia-induced HIF1 is associated with the EndMT program. K, representative immunofluorescence images showing CD31/Hif1α (red) and SNAIL (green) in normoxic (upper panel) and hypoxic cells (lower panel); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Acquisition of HIF1α upon hypoxia exposure correlated with SNAIL acquisition. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Cultivation of HCAECs under hypoxic conditions induced intracellular accumulation of Hif1α (Fig. 1, J and K), correlating with increased expression of mesenchymal marker α-SMA (Fig. 1J) and decreased expression of endothelial VE-cadherin (Fig. 1J). Moreover, EndMT transcription factor SNAIL colocalized with HIF1α under hypoxia (Fig. 1K). Based on this correlative evidence, we next aimed to further explore a causal link of Hif1α accumulation and EndMT.

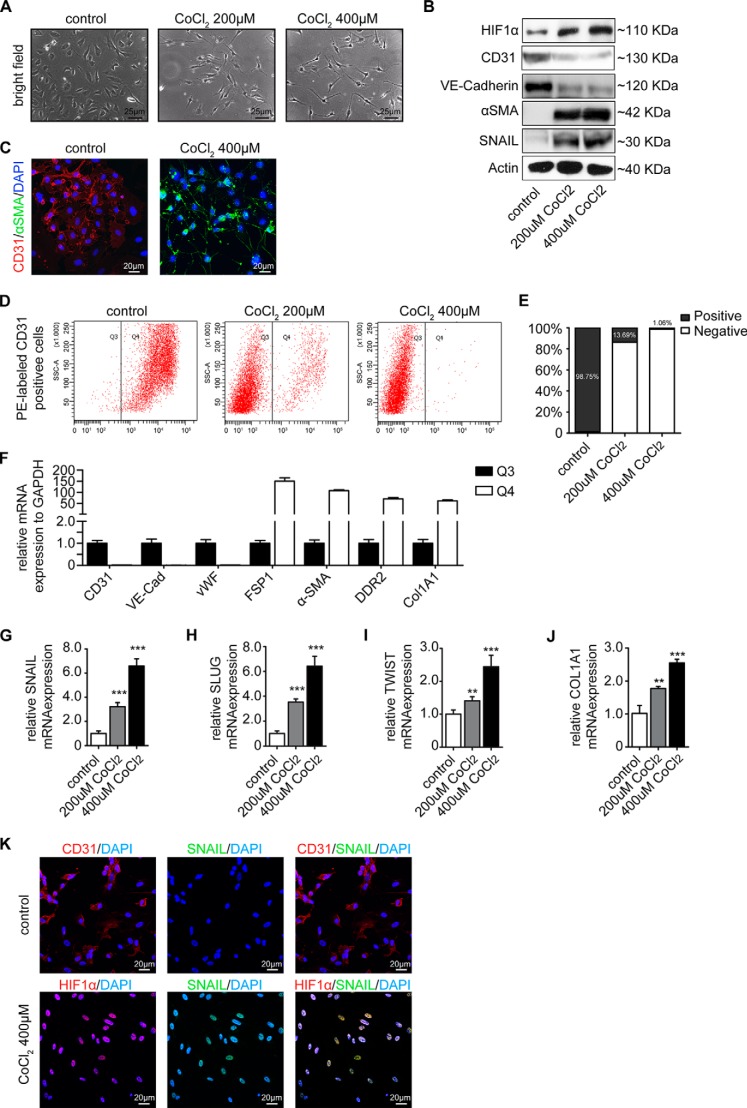

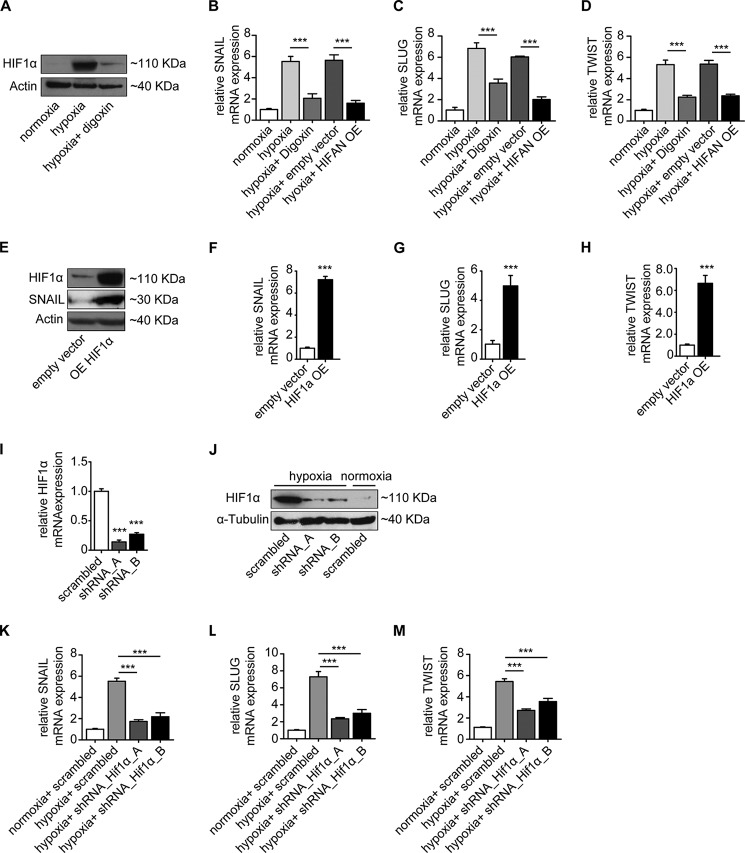

HIF1α is the major transcription factor specifically activated during hypoxia. Because cobalt aberrantly increases Hif1α under normoxia by inhibiting the prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing enzymes and subsequently inhibiting Hif1α degradation (28, 29), we next exposed HCAECs to CoCl2 to specifically induce Hif1α independently of hypoxia. Supplementation of cell culture media with CoCl2 caused intracellular accumulation of Hif1α in a dose-dependent manner that correlated with acquisition of spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 2, A and B), acquisition of α-SMA, and decreased CD31 expression (Fig. 2, C–E). As under hypoxic conditions, loss of CD31 upon CoCl2 treatment was associated with increased expression of FSP1, α-SMA, DDR2, and collagen 1A1 and loss of the other endothelial markers VE-cadherin and VWF (Fig. 2F). Correspondingly, EndMT key regulators SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST as well as collagen 1A1 upon CoCl2 treatment mimicked phenotypic changes observed upon cultivation under hypoxic conditions (compare Fig. 2, G--K, with Fig. 1). To further substantiate the link among hypoxia, Hif1α, and EndMT, we next explored the impact of digoxin, an inhibitor of Hif1α protein translation (30) (Fig. 3A) and overexpression of a dominant-negative Hif1α mutant on the EndMT response to hypoxia. Both digoxin and dominant-negative Hif1α mutant overexpression effectively blunted expression of SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST (Fig. 3, B–D) under hypoxic conditions. Furthermore, intracellular accumulation of Hif1α under normoxic conditions through superphysiologic transgenic overexpression (Fig. 3E) reduced CD31 expression and induced expression of EndMT master regulators (Fig. 3, F–H). Conversely, shRNA knockdown of HIF1α (using two different constructs; Fig. 3, I and J) reduced expression of EndMT transcription factors under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3, K–M). In summary, our data suggested that hypoxia induces phenotypic changes typical of EndMT in HCAECs and that this effect is mediated by Hif1α.

FIGURE 2.

CoCl2, a mimic of hypoxia, induces endothelial to mesenchymal transition. A, representative bright field images showing the morphology of untreated and CoCl2-treated cells (200 and 400 nm). CoCl2-treated HCAECs showed a fibroblast-like phenotype. Scale bars, 25 μm. B, Western blot analysis showing expression of HIF1α, CD31, VE-cadherin, α-SMA, and SNAIL in HCAECs treated with CoCl2 (200 and 400 nm). All blots were reprobed with an anti-actin antibody as a loading control. C, representative immunofluorescence images showing CD31 (red) and α-SMA (green) staining in untreated (left panel) and CoCl2-treated cells (right panel); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Acquisition of a spindle-shaped morphology upon CoCl2 exposure correlated with increased α-SMA expression and loss of CD31. Scale bars, 20 μm. D, untreated control cells (left panel), cells treated with 200 nm CoCl2 (middle panel), or cells treated with 400 nm CoCl2 (right panel) were sorted by FACS according to CD31 expression. CD31 protein was labeled with phycoerythrin (PE) (red) (x axis). In control cells, CD31+ cells were most prominent (gate Q4). This population was decreased under CoCl2 treatment in favor of CD31− cells (gate Q3). E, quantification of CD31+ and CD31− cells exposed to CoCl2 treatment. F, cells from gate Q3 and Q4 of 400 nm CoCl2-treated cells were sorted and compared by quantitative real time PCR analysis. Expression of mRNAs encoding the endothelial markers (CD31, VE-cadherin (VE-Cad), and VWF) and mesenchymal markers (FSP1, α-SMA, DDR2, and collagen 1A1) in the CD31− (Q3) cell population is shown compared with their expression in the CD31+ (Q4) cell population. G–J, qRT-PCR data showing the mRNA expression of EndMT transcription factors (SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST) and COL1A1 in untreated and CoCl2-treated cells. EndMT transcription factors and COL1A1 were significantly induced in endothelial cells upon CoCl2 treatment. Results were normalized to reference gene GAPDH (expression is presented as mean value; error bars represent S.D.; n = 3; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). K, representative immunofluorescence images showing CD31/Hif1α (red) and SNAIL (green) in normoxic (upper panel) and hypoxic cells (lower panel); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Acquisition of HIF1α upon CoCl2 treatment correlated with SNAIL acquisition. Scale bars, 20 μm.

FIGURE 3.

HIF1α expression mediates endothelial to mesenchymal transition. A, HCAECs treated with 100 nm digoxin have significantly reduced HIF1α accumulation upon hypoxia as shown by Western blot analysis. Actin was used as an equal loading control. B–D, qRT-PCR data showing the mRNA expression levels of SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST in normoxic and hypoxic conditions in the absence or presence of digoxin or dominant-negative Hif1α mutant overexpression in endothelial cells. Reduction of HIF1α by digoxin or overexpression of dominant-negative Hif1α mutant (HIFAN OE) resulted in inhibition of the EndMT program. E, overexpression (OE) of HIF1α in HCAECs by pCMV6-HIF1α transfection. HIF1α and SNAIL expression levels were examined by Western blot analysis. F–H, qRT-PCR data showing the mRNA expression levels of EndMT markers SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST in empty control vector-transfected and pCMV6-HIF1α-transfected HCAECs. Upon HIF1α overexpression, transcription factors were significantly induced in endothelial cells. qRT-PCR (I) and Western blot (J) show the mRNA and protein expression, respectively, in HCAECs transfected with two different HIF1α shRNA constructs. Cells transfected with scrambled shRNA served as the control. K–M, qRT-PCR analysis showing the mRNA expression levels of EndMT markers SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST in HCAECs transfected with HIF1α shRNA compared with cells transfected with scrambled shRNA constructs. Under the hypoxia condition, the expression of transcription factors was significantly reduced in HIF1α shRNA-transfected cells (expression is presented as mean value; error bars represent S.D.; n = 3; ***, p < 0.001).

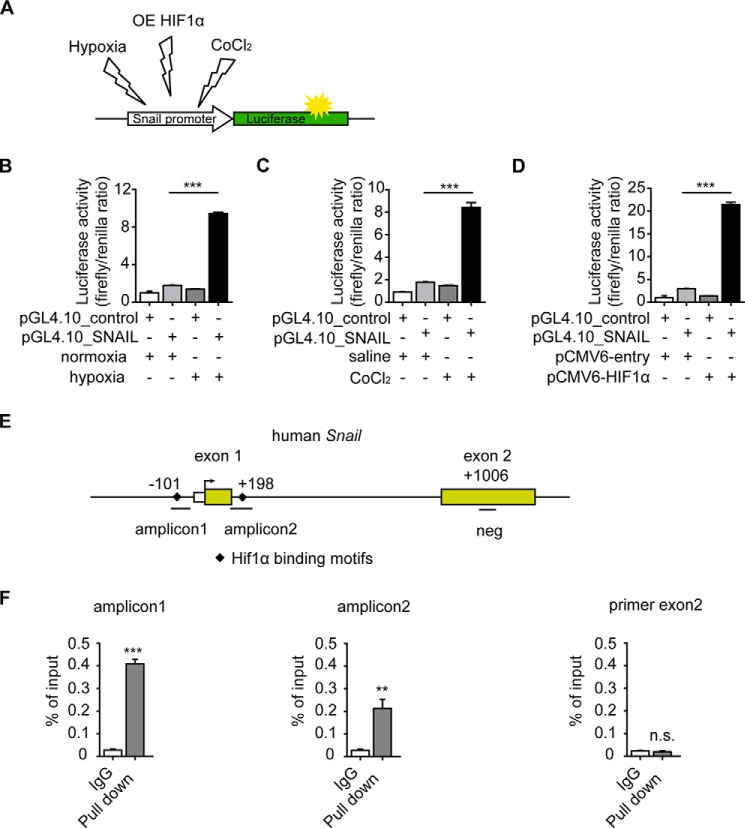

Because the EndMT master regulator SNAIL has been identified to be a direct transcriptional target of HIF1α (31), we next performed luciferase assays utilizing a SNAIL-pGL4.10 firefly reporter containing HIF1α target motifs within the SNAIL promoter to further elucidate this causal link with Hif1α transcription factor upon hypoxia and EndMT (Fig. 4A). Culture under hypoxic conditions, accumulation of endogenous Hif1α through addition of CoCl2 to culture media, and overexpression of Hif1α at superphysiological levels all induced SNAIL promoter activity (Fig. 4, A–D). A ChIP assay further demonstrated that Hif1α directly binds to the promoter region of SNAIL containing Hif1α binding motifs (Fig. 4, E and F).

FIGURE 4.

HIF1α induces SNAIL expression through direct binding to its promoter. A, schematic illustration of pGL4.10_SNAIL luciferase reporter construct that was exposed to different conditions (normoxia, hypoxia, CoCl2 treatment, and HIF1α overexpression (OE)). B–D, HCAECs were transfected with a pGL4.10_SNAIL luciferase reporter construct and a control Renilla expression vector. A luciferase assay shows that SNAIL promoter activity significantly increases under hypoxic conditions (B), CoCl2 treatment (C), and HIF1α overexpression (D). The bar graphs display relative SNAIL promoter activities normalized to Renilla luciferase. E, simplified schematic showing the human SNAIL promoter along with exons (yellow boxes), translational start site (black arrow), HIF1α binding motifs (black diamonds), locations of SNAIL ChIP primers (amplicon1 and amplicon2), and negative control chip primer (neg) location. F, the binding properties of HIF1α to the SNAIL promoter region were analyzed by ChIP assay following qRT-PCR. IgG purified from the same species as HIF1α antibody was used as a negative control for ChIP (expression is presented as mean value; error bars represent S.D.; n = 3; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., no significance).

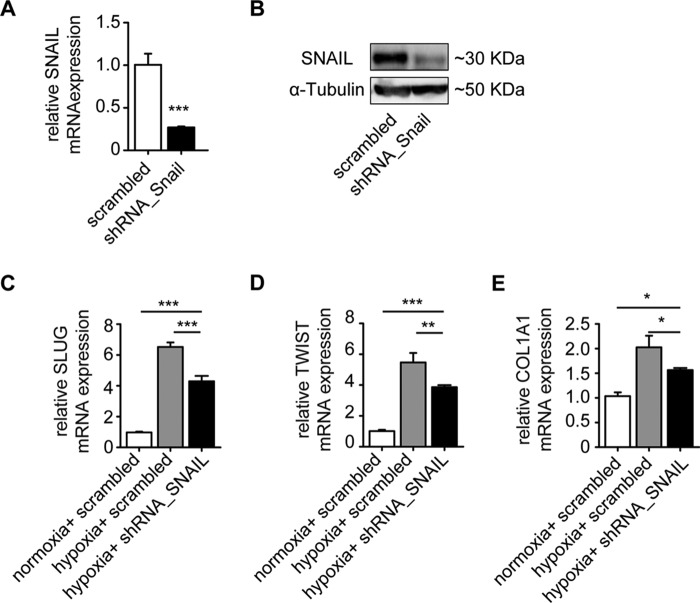

We therefore next aimed to test whether hypoxia-induced EndMT is SNAIL-dependent. Under hypoxic condition, shRNA knockdown of SNAIL (Fig. 5, A and B) led to reduced expression of the other two EndMT master genes, SLUG and TWIST, as well as of collagen 1A1 as compared with scrambled control (Fig. 5, C–E). However, expression levels upon SNAIL knockdown did not reach the same low levels as under normoxic conditions (Fig. 5, C–E), suggesting an additional, Snail-independent pathway.

FIGURE 5.

Knockdown of SNAIL ameliorates hypoxia-induced EndMT. qRT-PCR (A) and Western blot (B) analysis show the mRNA and protein expression, respectively, in HCAECs transfected with SNAIL shRNA constructs. Cells transfected with scrambled shRNA served as the control. C–E, qRT-PCR analysis showing the mRNA expression levels of EndMT markers SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST in HCAECs transfected with SNAIL shRNA compared with cells transfected with scrambled shRNA constructs. Under the hypoxia condition, the expression of transcription factors was significantly reduced in SNAIL shRNA-transfected cells (expression levels are presented as mean value; error bars represent S.D.; n = 3; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., no significance).

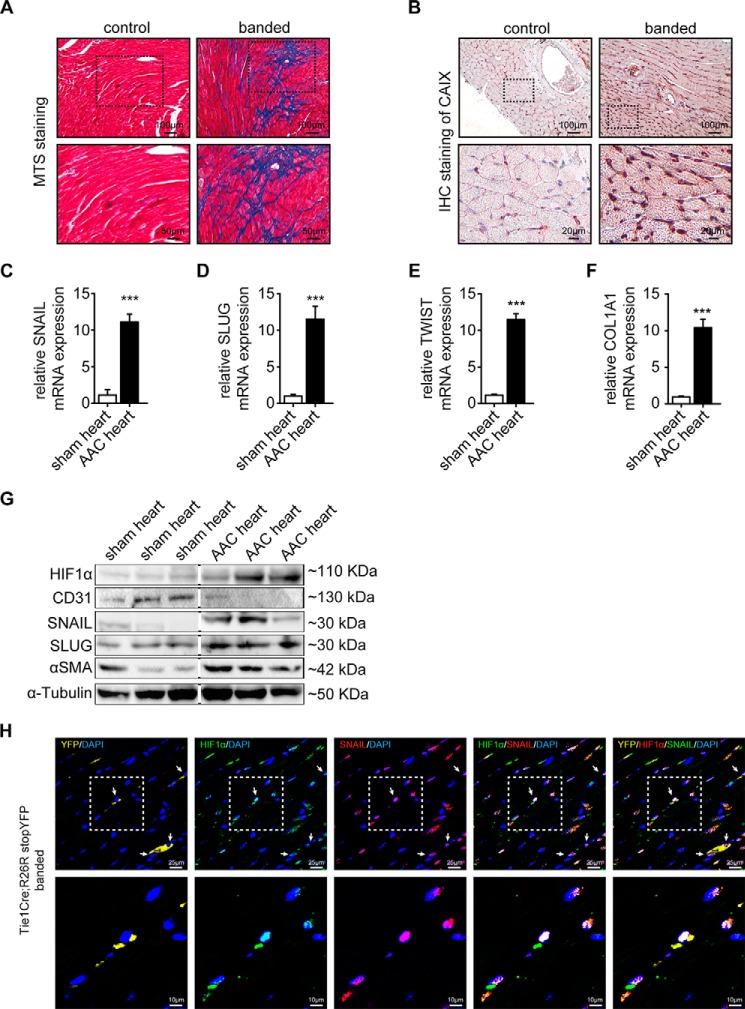

We next aimed to explore the possible contribution of hypoxia in the context of cardiac fibrosis. For this purpose, we utilized the mouse model of ascending aortic constriction that consistently causes cardiac fibrosis and in which EndMT was previously demonstrated to occur. Fibrotic tissue was detected by Masson's trichrome stain (Fig. 6A) associated with intrinsic hypoxia visualized by carbonic anhydrase IX immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6B). As expected, constriction of the ascending aorta caused both cardiac fibrosis throughout the myocardium and hypoxia especially in interstitial cells (Fig. 6, A and B). Cardiac fibrosis and intrinsic hypoxia were associated with increased expression of SNAIL, SLUG, and TWIST as well as of collagen 1A1 (Fig. 6, C–G), substantial accumulation of Hif1α (Fig. 6G), increased α-SMA, and decreased expression of CD31 (Fig. 6G), mirroring the link of hypoxia and EndMT that was observed in cell culture experiments. Finally, we utilized a Tie1Cre;R26RstopYFP endothelial lineage tracing mouse model with ascending aortic constriction-induced cardiac fibrosis and detected colocalization of SNAIL, HIF1α, and YFP (Fig. 6H). Although these data support the occurrence of EndMT in HIF1α-positive cells of endothelial origin in vivo, additional studies will be needed to prove HIF1α dependence in hypoxia-induced EndMT.

FIGURE 6.

Induction of HIF1α in experimental cardiac fibrosis. A, representative areas of Masson's trichrome stained (MTS) sham and banded mouse heart sections. Scale bars, 100 (top panels) and 50 μm (bottom panels). B, immunohistochemistry (IHC) of hypoxia marker carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) in sham and banded mouse heart sections. The dotted areas denote the regions magnified in the lower panel. Scale bars, 100 (top panels) and 20 μm (bottom panels). C–F, qRT-PCR data showing the mRNA expression of EndMT transcription factors (Snail, Slug, and Twist) and Col1A1 in sham control and banded cells. EndMT transcription factors and Col1A1 were significantly induced in banded mouse hearts. Results were normalized to reference gene GAPDH (expression is presented as mean value; error bars represent S.D.; n = 3; ***, p < 0.001). G, Western blots showing expression of HIF1α, CD31, SNAIL, SLUG, and α-SMA in sham control and banded mouse hearts. All blots were reprobed with an anti-α-tubulin antibody as an equal loading control. H, representative confocal photomicrographs of sections from banded Tie1Cre;R26RstopYFP hearts stained for HIF1α (green) and SNAIL (red). Endogenous YFP expression is shown in yellow. Dotted areas denote the region shown magnified in the lower panel; white arrows indicate representative triple positive cells. Scale bars, 25 (top panels) and 10 μm (bottom panels). AAC, ascending aortic constriction.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that hypoxia induces phenotypic changes typical of EndMT in cultured human coronary endothelial cells, that this effect is mediated by HIF1α, and that the EndMT master regulator SNAIL is a direct target of HIF1α. Because previous studies have reported that TGFβ is a prototypical inducer of EndMT and that hypoxia is a stimulus for TGFβ expression, it is important to note that our data demonstrate that EndMT involving HCAECs is also mediated by HIF1α independently of TGFβ, suggesting that these are distinct, potentially additive pathways.

Our finding that hypoxia-induced EndMT is mediated by HIF1α is in line with existing literature in the cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition field reporting that hypoxia contributes to cancer progression and metastasis through induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in an HIF1α-dependent manner (32). Furthermore, our study is compatible with previous reports demonstrating that hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition is mediated through epithelial-mesenchymal transition master transcription factors Snail, Slug, and Twist (33–35). In this regard, our study demonstrates that Snail is a direct target of HIF1α by revealing that HIF1α directly binds to its HIF1-binding sites within the SNAIL promoter. Future studies are needed to address which HIF1α-binding sites are functionally relevant. Furthermore, our data are supported by a previous study demonstrating that cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury is associated with induction of Snail within endothelial cells (36).

We are aware that hypoxia is a principal inducer of angiogenesis. In this regard, sprouting endothelial cells, so-called tip cells, share similarities with endothelial cells undergoing EndMT: both tip cells and EndMT cells display spindle-shaped morphology associated with increased expression of mesenchymal cytoskeletal constituents such as vimentin (37). A principal difference, however, is the decreased expression of endothelial markers such as CD31 and VE-cadherin that is typical of EndMT but is not observed in tip cells. Another difference is an increased expression of extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen types I and III that is only observed in endothelial cells undergoing EndMT but not in tip cells, raising the question of the molecular mechanisms discriminating between EndMT and sprouting angiogenesis (38).

In this regard, our studies demonstrate that primary HCAECs undergo EndMT in response to hypoxia via a mechanism involving HIF1-mediated induction of SNAIL. In contrast, hypoxia or SNAIL overexpression did not increase collagen expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (36). Similarly, targeted overexpression of SLUG (SNAI2) in human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced acquisition of spindle-shaped morphology, whereas VE-cadherin expression was unaltered (39). These differing observations are in line with previous reports that suggested that only distinct subpopulations of endothelial cells have the capacity to undergo EndMT. In the context of the heart, a previous study suggested that specifically endothelial cells that originate from the endocardium (that undergo EndMT during cardiac development to form the mesenchymal cushion) maintain increased susceptibility to undergo EndMT as remnants from their embryonic origin. HCAECs used in this study are derived at least in part from endocardial endothelial cells, whereas aortic endothelial or human umbilical vein endothelial cells are of other origin. The molecular mechanisms that determine distinct cellular responses to Snail/Slug/Twist activation in individual endothelial cell populations remain elusive for now and deserve further exploration.

This work was supported in part by funds of the University Medical Center of Göttingen and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grant SFB1002/C01 (to E. Z.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- EndMT

- endothelial to mesenchymal transition

- HCAEC

- human coronary artery endothelial cell

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- α-SMA

- α-smooth muscle actin

- Col1A1

- collagen 1A1

- VE

- vascular endothelial

- FSP1

- fibroblast -specific protein 1

- DDR2

- discoidin domain receptor 2

- VWF

- von Willebrand factor.

References

- 1. Piera-Velazquez S., Li Z., Jimenez S. A. (2011) Role of endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 1074–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin F., Wang N., Zhang T. C. (2012) The role of endothelial-mesenchymal transition in development and pathological process. IUBMB Life 64, 717–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Meeteren L. A., ten Dijke P. (2012) Regulation of endothelial cell plasticity by TGF-β. Cell Tissue Res. 347, 177–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisenberg L. M., Markwald R. R. (1995) Molecular regulation of atrioventricular valvuloseptal morphogenesis. Circ. Res. 77, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hashimoto N., Phan S. H., Imaizumi K., Matsuo M., Nakashima H., Kawabe T., Shimokata K., Hasegawa Y. (2010) Endothelial-mesenchymal transition in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 43, 161–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maddaluno L., Rudini N., Cuttano R., Bravi L., Giampietro C., Corada M., Ferrarini L., Orsenigo F., Papa E., Boulday G., Tournier-Lasserve E., Chapon F., Richichi C., Retta S. F., Lampugnani M. G., Dejana E. (2013) EndMT contributes to the onset and progression of cerebral cavernous malformations. Nature 498, 492–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rieder F., Kessler S. P., West G. A., Bhilocha S., de la Motte C., Sadler T. M., Gopalan B., Stylianou E., Fiocchi C. (2011) Inflammation-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: a novel mechanism of intestinal fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 2660–2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zeisberg E. M., Potenta S., Xie L., Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. (2007) Discovery of endothelial to mesenchymal transition as a source for carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 67, 10123–10128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zeisberg E. M., Potenta S. E., Sugimoto H., Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. (2008) Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 2282–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zeisberg E. M., Tarnavski O., Zeisberg M., Dorfman A. L., McMullen J. R., Gustafsson E., Chandraker A., Yuan X., Pu W. T., Roberts A. B., Neilson E. G., Sayegh M. H., Izumo S., Kalluri R. (2007) Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat. Med. 13, 952–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu B., Zhang Z., Lui W., Chen X., Wang Y., Chamberlain A. A., Moreno-Rodriguez R. A., Markwald R. R., O'Rourke B. P., Sharp D. J., Zheng D., Lenz J., Baldwin H. S., Chang C. P., Zhou B. (2012) Endocardial cells form the coronary arteries by angiogenesis through myocardial-endocardial VEGF signaling. Cell 151, 1083–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mihira H., Suzuki H. I., Akatsu Y., Yoshimatsu Y., Igarashi T., Miyazono K., Watabe T. (2012) TGF-β-induced mesenchymal transition of MS-1 endothelial cells requires Smad-dependent cooperative activation of Rho signals and MRTF-A. J. Biochem. 151, 145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakano Y., Oyamada M., Dai P., Nakagami T., Kinoshita S., Takamatsu T. (2008) Connexin43 knockdown accelerates wound healing but inhibits mesenchymal transition after corneal endothelial injury in vivo. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 93–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noseda M., McLean G., Niessen K., Chang L., Pollet I., Montpetit R., Shahidi R., Dorovini-Zis K., Li L., Beckstead B., Durand R. E., Hoodless P. A., Karsan A. (2004) Notch activation results in phenotypic and functional changes consistent with endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation. Circ. Res. 94, 910–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rivera-Feliciano J., Lee K. H., Kong S. W., Rajagopal S., Ma Q., Springer Z., Izumo S., Tabin C. J., Pu W. T. (2006) Development of heart valves requires Gata4 expression in endothelial-derived cells. Development 133, 3607–3618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kokudo T., Suzuki Y., Yoshimatsu Y., Yamazaki T., Watabe T., Miyazono K. (2008) Snail is required for TGFβ-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition of embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3317–3324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kovacic J. C., Mercader N., Torres M., Boehm M., Fuster V. (2012) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: from cardiovascular development to disease. Circulation 125, 1795–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naber H. P., Drabsch Y., Snaar-Jagalska B. E., ten Dijke P., van Laar T. (2013) Snail and Slug, key regulators of TGF-β-induced EMT, are sufficient for the induction of single-cell invasion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 435, 58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cano A., Pérez-Moreno M. A., Rodrigo I., Locascio A., Blanco M. J., del Barrio M. G., Portillo F., Nieto M. A. (2000) The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thornhill B. A., Forbes M. S., Marcinko E. S., Chevalier R. L. (2007) Glomerulotubular disconnection in neonatal mice after relief of partial ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int. 72, 1103–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watson C. J., Collier P., Tea I., Neary R., Watson J. A., Robinson C., Phelan D., Ledwidge M. T., McDonald K. M., McCann A., Sharaf O., Baugh J. A. (2014) Hypoxia-induced epigenetic modifications are associated with cardiac tissue fibrosis and the development of a myofibroblast-like phenotype. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 2176–2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lei L., Mason S., Liu D., Huang Y., Marks C., Hickey R., Jovin I. S., Pypaert M., Johnson R. S., Giordano F. J. (2008) Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent degeneration, failure, and malignant transformation of the heart in the absence of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 3790–3803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luo Y., Zhu D. (2014) Combinatorial control of transgene expression by hypoxia-responsive promoter and microRNA regulation for neural stem cell-based cancer therapy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 751397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bar E. E., Lin A., Mahairaki V., Matsui W., Eberhart C. G. (2010) Hypoxia increases the expression of stem-cell markers and promotes clonogenicity in glioblastoma neurospheres. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 1491–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tampe B., Tampe D., Müller C. A., Sugimoto H., LeBleu V., Xu X., Müller G. A., Zeisberg E. M., Kalluri R., Zeisberg M. (2014) Tet3-mediated hydroxymethylation of epigenetically silenced genes contributes to bone morphogenic protein 7-induced reversal of kidney fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25, 905–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barberà M. J., Puig I., Domínguez D., Julien-Grille S., Guaita-Esteruelas S., Peiró S., Baulida J., Francí C., Dedhar S., Larue L., García de Herreros A. (2004) Regulation of Snail transcription during epithelial to mesenchymal transition of tumor cells. Oncogene 23, 7345–7354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu X., Tan X., Lin Q., Schmidt B., Engel W., Pantakani D. V. (2013) Mouse Dazl and its novel splice variant functions in translational repression of target mRNAs in embryonic stem cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 425–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ho V. T., Bunn H. F. (1996) Effects of transition metals on the expression of the erythropoietin gene: further evidence that the oxygen sensor is a heme protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 223, 175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Epstein A. C., Gleadle J. M., McNeill L. A., Hewitson K. S., O'Rourke J., Mole D. R., Mukherji M., Metzen E., Wilson M. I., Dhanda A., Tian Y. M., Masson N., Hamilton D. L., Jaakkola P., Barstead R., Hodgkin J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Schofield C. J., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001) C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107, 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang H., Qian D. Z., Tan Y. S., Lee K., Gao P., Ren Y. R., Rey S., Hammers H., Chang D., Pili R., Dang C. V., Liu J. O., Semenza G. L. (2008) Digoxin and other cardiac glycosides inhibit HIF-1α synthesis and block tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19579–19586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luo D., Wang J., Li J., Post M. (2011) Mouse snail is a target gene for HIF. Mol Cancer Res. 9, 234–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Du R., Sun W., Xia L., Zhao A., Yu Y., Zhao L., Wang H., Huang C., Sun S. (2012) Hypoxia-induced down-regulation of microRNA-34a promotes EMT by targeting the Notch signaling pathway in tubular epithelial cells. PLoS One 7, e30771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang M. H., Wu M. Z., Chiou S. H., Chen P. M., Chang S. Y., Liu C. J., Teng S. C., Wu K. J. (2008) Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1α promotes metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang L., Huang G., Li X., Zhang Y., Jiang Y., Shen J., Liu J., Wang Q., Zhu J., Feng X., Dong J., Qian C. (2013) Hypoxia induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via activation of SNAI1 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 13, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang C. H., Yang W. H., Chang S. Y., Tai S. K., Tzeng C. H., Kao J. Y., Wu K. J., Yang M. H. (2009) Regulation of membrane-type 4 matrix metalloproteinase by SLUG contributes to hypoxia-mediated metastasis. Neoplasia 11, 1371–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee S. W., Won J. Y., Kim W. J., Lee J., Kim K. H., Youn S. W., Kim J. Y., Lee E. J., Kim Y. J., Kim K. W., Kim H. S. (2013) Snail as a potential target molecule in cardiac fibrosis: paracrine action of endothelial cells on fibroblasts through snail and CTGF axis. Mol. Ther. 21, 1767–1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dave J. M., Bayless K. J. (2014) Vimentin as an integral regulator of cell adhesion and endothelial sprouting. Microcirculation 21, 333–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Davis G. E., Senger D. R. (2005) Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ. Res. 97, 1093–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Welch-Reardon K. M., Ehsan S. M., Wang K., Wu N., Newman A. C., Romero-Lopez M., Fong A. H., George S. C., Edwards R. A., Hughes C. C. (2014) Angiogenic sprouting is regulated by endothelial cell expression of Slug. J. Cell Sci. 127, 2017–2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ford C. E., Lau S. K., Zhu C. Q., Andersson T., Tsao M. S., Vogel W. F. (2007) Expression and mutation analysis of the discoidin domain receptors 1 and 2 in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 96, 808–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kiran M. S., Viji R. I., Kumar S. V., Prabhakaran A. A., Sudhakaran P. R. (2011) Changes in expression of VE-cadherin and MMPs in endothelial cells: implications for angiogenesis. Vasc. Cell 3, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]