Background: CLN3 protein function is still unknown, but its loss causes Batten disease.

Results: Drug screening in a Batten disease model was developed to identify modifiers of altered cellular pathways.

Conclusion: Alterations in Ca2+ handling are implicated in Batten disease, which may negatively influence the intracellular pathways regulated by Ca2+.

Significance: A proof-of-concept is established for the application of drug screening to Batten disease research.

Keywords: autophagy, calcium, chemical biology, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lysosomal storage disease, lysosome, CLN3, GFP-LC3, juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL), thapsigargin

Abstract

Abnormal accumulation of undigested macromolecules, often disease-specific, is a major feature of lysosomal and neurodegenerative disease and is frequently attributed to defective autophagy. The mechanistic underpinnings of the autophagy defects are the subject of intense research, which is aided by genetic disease models. To gain an improved understanding of the pathways regulating defective autophagy specifically in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL or Batten disease), a neurodegenerative disease of childhood, we developed and piloted a GFP-microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (GFP-LC3) screening assay to identify, in an unbiased fashion, genotype-sensitive small molecule autophagy modifiers, employing a JNCL neuronal cell model bearing the most common disease mutation in CLN3. Thapsigargin, a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) Ca2+ pump inhibitor, reproducibly displayed significantly more activity in the mouse JNCL cells, an effect that was also observed in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived JNCL neural progenitor cells. The mechanism of thapsigargin sensitivity was Ca2+-mediated, and autophagosome accumulation in JNCL cells could be reversed by Ca2+ chelation. Interrogation of intracellular Ca2+ handling highlighted alterations in endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondrial, and lysosomal Ca2+ pools and in store-operated Ca2+ uptake in JNCL cells. These results further support an important role for the CLN3 protein in intracellular Ca2+ handling and in autophagic pathway flux and establish a powerful new platform for therapeutic screening.

Introduction

The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs)3 are a group of inherited neurodegenerative diseases characterized by motor and cognitive decline, seizures, and typically vision loss. The NCLs are further typified by the occurrence of abnormal accumulations of protein- and lipid-containing autofluorescent storage material in both neuronal and non-neuronal cells, which most often contains abundant levels of the pore-forming subunit of the mitochondrial ATP synthase (subunit c of the F0-ATPase complex; hereafter referred to as subunit c) (1). Currently, 13 genes are known to cause different subtypes of NCL, encoding proteins of varied, often incompletely understood functions within the secretory and endosomal-lysosomal systems (2–4). In juvenile onset NCL (JNCL), autosomal recessive inheritance of loss-of-function mutations in the CLN3 gene lead to disease, with most patients carrying at least one copy of a common ∼1-kb deletion in CLN3 (5).

CLN3 encodes a multipass transmembrane protein, referred to as CLN3, CLN3p, or battenin (5), that has been demonstrated to localize to multiple membrane compartments, including within the endosomal, lysosomal, and autophagosomal pathways (6). Although the primary function of CLN3 has not yet been fully uncovered it is proposed to play a role in vesicular trafficking because its deficiency leads to altered distribution of endosomal and lysosomal proteins and phospholipids (7–12), abnormal morphology of endocytic and lysosomal organelles (7, 11), lysosomal pH dyshomeostasis (13–15), and amino acid transport defects (16). The hallmark JNCL storage material containing subunit c accumulates in both autophagosomes and lysosomes implicating further impact of CLN3 deficiency on the autophagy pathway (17).

In previous work employing a genetically accurate neuronal progenitor cell model of JNCL that bears a homozygous ∼1-kb deletion in the murine Cln3 gene, recapitulating the most common genetic defect found in JNCL patients (7), we further demonstrated that Cln3 mutation leads to LC3-II-positive autophagosome accumulation, even preceding the onset of detectable storage material (17). To further dissect the autophagy pathway abnormalities caused by Cln3 mutation, here we have developed a high throughput, cell-based autophagy assay, employing the use of a green fluorescent protein-tagged LC3 transgene (GFP-LC3), stably expressed in our mouse Cln3 cell culture model of JNCL. Using this cell system, we conducted a screen to identify small molecule modifiers of autophagy. By focusing on the hit compounds that showed differential sensitivities in the cells bearing the Cln3 disease mutations, compared with the wild type cells, we have identified specific intracellular Ca2+ handling alterations that impact JNCL pathophysiological pathways in vitro, supporting further investigation of CLN3 in Ca2+ homeostasis and directed targeting of Ca2+ handling defects as potential JNCL therapies.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents and Cell Lines

Establishment and Maintenance of CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 Cell Lines Expressing GFP-LC3

CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cell lines were generated as described previously (7). To establish stably expressing GFP-LC3 derivative cell lines from these, cells were first transiently transfected with the pCAG-EGFP-LC3 expression plasmid (a generous gift from Dr. Noboru Mizushima) using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Stable transfectant subclonal lines were then established by replating for limiting dilution subcloning 72 h post-transfection, to expand from single cells. Positive subclones were identified by visual scoring for GFP fluorescence. Initially, >6 subclones per genotype were established and screened for relative GFP cytosolic and vesicular signal, and representative subclones for each genotype were subsequently chosen for use in the primary screen and in follow-up experiments.

For maintenance, cells were grown at 33 °C, with 5% CO2 atmosphere control, in Cbc media (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco catalog no. 11995-065), 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Sigma catalog no. F4135), 24 mm KCl, 1× penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine (Corning Cellgro® catalog no. 0-009-CI), and 200 μg/ml G418 (Gibco catalog no. 11811-098)). Unless otherwise indicated, cells were maintained between 30 and 90% confluency on 100-mm plastic tissue culture dishes, as described previously (7).

Compounds (Not Including the Screening Library) Used in This Study

The following compounds were used: thapsigargin (Enzo catalog no. BML-PE180); BAPTA-AM (Life Technologies, Inc., catalog no. B-6769); bafilomycin B1 (AG Scientific Inc., catalog no. B-1185); tunicamycin (Sigma, catalog no. T7765); chelerythrine (Sigma, catalog no. C-2932); arvanil (Biomol catalog no. VR-101); nifedipine (Biomol catalog no. CA-210); A-23187 (Biomol catalog no. CA-100); ikarugamycin (Biomol catalog no. EI-313); and CA-074 (Biomol catalog no. PI-126). All compounds were reconstituted in DMSO.

Cell-based Screening Assay

Compound Library Used for Screening

Plate 1 from the ICCB Known Bioactives Library (Biomol catalog no. 2840-0001) was used in our primary cell screen; this library is a collection of diverse biologically active compounds with defined biological activity. Briefly, plate 1 contained 320 test compounds, suspended in DMSO, and 64 “vehicle” wells containing only DMSO, randomly positioned throughout a 384-well plate. Note that rapamycin, a well known autophagy inducer (18, 19), was not present in this library.

Primary Screen

CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells expressing GFP-LC3 were plated into clear-bottomed 384-well plates at a density of 2 × 103 cells/well and allowed to attach and recover from plating overnight. The following morning, test compounds and DMSO negative control were added to the wells by robotic pin-transfer from the library plate. Duplicate plates were prepared each for the CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells expressing GFP-LC3. Cells were then incubated with compounds for 24 h (33 °C, 5% CO2). At the 24-h time point, cells were fixed with freshly prepared 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by PBS wash (two 10-min washes) and Hoechst nuclear counterstaining (Life Technologies, Inc., catalog no. H3570). Following nuclear counterstaining, PBS containing 0.3% sodium azide was added to each well, and plates were sealed, wrapped in foil, and stored at 4 °C until they were imaged.

Imaging

Automated imaging of plates was performed at ambient temperature with a ×10 objective, using an ImageXpress Micro high content imaging system (Molecular Devices Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). MetaXpress® software, version 2.0.1.28, was used to acquire and analyze the images. For DAPI, laser- and image-based focusing was used, and images were acquired with a 100-ms exposure time. For GFP, laser- and image-based focusing was used, and images were acquired with a 1500-ms exposure time. Nuclei and vesicle compartments were identified on the appropriate channels using the “nuclei” and “vesicles” parameters in the Transfluor® module of MetaXpress®. For vesicles, parameters were set to a 5-pixel minimum, a 14-pixel maximum, and an intensity of at least 80 gray levels above local background. For nuclei, parameters were set to a 12-pixel minimum, a 50-pixel maximum, and an intensity of at least 150 gray levels above local background. One image per well (typically containing ∼250 cells) was analyzed for each compound treatment to obtain per well and per cell image measurements. The end point measurement for the primary screening assay was “vesicle count per cell.”

Data Processing and Analysis

To account for plate-to-plate variation in signal, each compound treatment well was compared with the collection of DMSO treatment well measurements performed in the same plate. First, the values of DMSO treatment wells in a given plate were compiled, and values falling above or below twice the standard deviation for this overall distribution were discarded as outliers (this accounted for <5% of the total DMSO wells in the plate and typically represented edge wells). The remaining DMSO treatment measurements were then used to arrive at a “mean vesicle count per cell” value for DMSO treatment. To obtain a z score for each compound well, the mean DMSO treatment value (μ) was subtracted from the individual compound value (xi), and this value was then divided by twice the standard deviation of the DMSO treatment wells (2σ), using the equation z = (xi − μ)/2σ. Finally, to arrive at our “hit list,” a mean z score was calculated from each of the replicate plates for each compound, and a cutoff was then applied to define hits as those compounds that had a mean z score of >2 or <−2. To facilitate the identification of “genotype-sensitive” compounds among the compounds displaying activity in the primary screen, i.e. compounds that tended to display more or less activity in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with the CbCln3+/+ cells, a “z score ratio” was calculated. Briefly, for each hit compound, the absolute value of the mean z score in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells divided by the mean z score in CbCln3+/+ cells was calculated, and genotype-sensitive activities were hypothesized if a hit compound's z score ratio was >2 or <0.5. The complete list of significant hits, with corresponding z score values and z score ratios, is provided in supplemental Table 1. z scores for all 320 compounds in the primary screen are provided in supplemental Table 2.

Secondary Dose-Response Analysis of Selected Hit Compounds

Seven of the hypothesized genotype-sensitive compounds from the primary screen data analysis (supplemental Table 1) were selected for follow-up dose-response experiments. These were selected based on putative mechanism-of-action, which was Ca2+-related in five cases (e.g. Ca2+ channels, Ca2+-responsive signaling) and was otherwise in a pathway of established interest in CLN3 research (e.g. lysosomal proteolysis and endocytosis). A secondary screening plate was prepared containing each of the selected compounds at a total of 11 concentrations per compound (in most cases, this included the original screening dose, one dose 2-fold more concentrated, and nine 2-fold serial dilutions), with DMSO-only control wells included in the plate. A single plate each for CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells was screened with the dilution series plate, exactly as described for the primary screening assay. End-point again was vesicle count per cell. “Nuclei count per image” was used as an additional end-point to assess relative toxicity of the compound treatments in the dose-response experiment. These data are provided in supplemental Fig. 1.

Cell Treatment in Follow-up Pharmacological Studies

For epifluorescence and confocal microscopy studies, CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells were cultured on 18-mm diameter number 1 glass coverslips (Fisher). Cells were typically seeded at a density of 5 × 104 and were grown overnight at 33 °C, 5% CO2 in Cbc media. For preparation of lysates, CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells were seeded at density of 9 × 105 into 100-mm dishes and were grown overnight at 33 °C, 5% CO2 in Cbc media. Cells were treated 24 h post-plating as follows.

Treatment with Thapsigargin

Unless otherwise indicated, cells were treated with 0.1 μm thapsigargin for 24 h.

Treatment with Tunicamycin

Cells were treated with 0.1 and 1 μg/ml tunicamycin for 24 h.

Treatment with Bafilomycin

To determine the saturating dose/incubation time for bafilomycin treatment, cells were treated with 0.1 or 1 μm bafilomycin. Lysates were collected at 6- and 24-h time points for immunoblot analysis. For microscopy experiments, cells were treated with 1 μm bafilomycin for 24 h.

Co-treatment with Bafilomycin and Thapsigargin

Cells were co-treated with 0.1 μm thapsigargin together with 1 μm bafilomycin for 24 h.

Treatment with BAPTA-AM

Cells were treated with or without (DMSO only) 0.1 μm thapsigargin for 23 h, and for the last hour, 5 μm BAPTA-AM was added to the media at a final concentration of 5 μm.

Starvation

Complete media were aspirated away and exchanged for Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Invitrogen, catalog no. 14025092), following a brief wash with warmed HBSS. Cells were incubated in HBSS for 1.5 h prior to fixation.

Treatment with Lysosomal Protease Inhibitors

For treatments with lysosomal protease inhibitors, the mouse cerebellar cells were treated with E64 (10 μg/ml) (E3132, Sigma) and pepstatin A (100 μg/ml) (P5318, Sigma) for 16 h. The NPCs were treated with E64 (10 μg/ml) and pepstatin A (50 μg/ml) for 16 h. For both sets of cells, the indicated doses were predetermined to be the saturating doses (data not shown), as recommended (19). For treatment with thapsigargin in the presence of lysosomal protease inhibitors, a 16-h pretreatment was performed with the protease inhibitors and then thapsigargin was added for 24 h.

Treatment with Known Autophagy Inducers

Cells were treated with 2 μm rapamycin (BML-A275, Enzo Life Sciences) and 10 μm torin (S2827, Selleck Chemical) for the indicated treatment times.

Human Neural Progenitor Cell (NPC) Culture

Human NPCs were derived and maintained as described previously (11). The control line was derived from GM8330-8 patient fibroblasts. The patient NPCs (CLN3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 and CLN3IVS13/E15) were derived from de-identified fibroblasts from JNCL individuals. NPCs were maintained on poly-l-ornithine- and laminin-coated plates, in media containing 97% DMEM/F-12 (Life Technologies, Inc., catalog no. 11330-032), 2% 50× B-27 Supplement (Life Technologies, Inc., catalog no. 17504-044) and 1% 1× penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine (Corning Cellgro® catalog no. 30-009-CI) and supplemented with 20 ng/ml of the growth factors EGF (Sigma catalog no. E9644) and FGF (Millipore catalog no. GF003). Cells were plated on either 6-well plates or on 14-mm diameter number 1 glass coverslips (Fisher) and left to attach overnight before treatment. For Western blotting, one well of a 6-well plate was harvested, and cell lysates were made using the procedure described below (see under “Immunoblotting and Densitometry”).

Immunostaining

Cells (CbCln3 cells or human iPSC-derived NPCs) grown on coverslips were fixed with one of two methods, depending on the primary antibody. For Rab7 antibody (Cell Signaling catalog no. 9367, used at 1:100 dilution), p62/SQSTM1 antibody (Enzo catalog no. BML-PW9860, used at 1:100 dilution in Cb cells and 1:400 in NPCs), and LAMP-2a antibody (Abcam catalog no. ab18528, used at 1:500 dilution), cells were fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde diluted in PBS, pH 7.4, at room temperature, for 20 min. Alternatively, for LAMP-1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology catalog no. sc-19992, used at 1:200 dilution) and in some experiments for LC3 antibody (Abcam catalog no. ab51520, used at 1:500 dilution), cells were fixed in an ice-cold 50:50 (v/v) mixture of methanol/acetone for 10 min. The immunostaining procedure was performed as described previously (11, 20). Briefly, 0.05% Triton X-100 diluted in PBS, pH 7.4, was used for cell permeabilization, and 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) diluted in PBS, pH 7.4, was used for blocking. However, permeabilization was different for the following, as indicated: for LAMP-2a antibody, cell permeabilization was with 0.5% saponin, diluted in blocking buffer; SERCA immunostaining (SERCA 2 antibody, catalog no. ab3625, Abcam) used 20 μg/ml digitonin; and p62 staining in NPCs instead utilized a 1-h 3% normal horse serum, 0.2% Triton X-100 permeabilization step. Notably, the different fixation and staining procedures required for the different primary antibodies resulted in slight differences in the overall fluorescent signal of GFP-LC3. It is also noteworthy that our staining conditions are expected to allow for visualization of GFP fluorescence in the late endosomal and lysosomal acidic compartments, because it is well documented that the permeabilization and neutral pH of fixation and staining solutions eliminates the quenching of GFP in these compartments (19, 21). Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor®-555 (Life Technologies, Inc.) and anti-rat Alexa Fluor®-568 (Life Technologies, Inc.) were used as secondary antibody (1:800). Coverslips were semi-permanently mounted onto microscope slides using ProLong® Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's recommended procedures. Nail polish-sealed and mounted coverslips were stored in the dark at 4 °C until they were imaged. Imaging was performed on an upright epifluorescence microscope equipped for digital capture (Zeiss) or on an SP5 AOBS scanning laser confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Image Analysis

Quantification of GFP-LC3 Vesicles and p62 Aggregates in Post-screening Follow-up Experiments

All like-stained images within a given experiment were taken with the same image acquisition settings and in the same imaging session. “GFP-LC3 Vesicle Count per Cell” was determined using the Transfluor® module of MetaXpress®, as described for the primary screen, but with the following differences. Images were captured at ×20 magnification; vesicles parameters were set to a width between 4 and 15 pixels and an intensity of at least 4000 gray levels above local background, and nuclei parameters were set to a width between 30 and 67 pixels and an intensity of at least 2500 gray levels above local background. For the experiment performed using BAPTA-AM alone on the CbCln3 cells, imaging parameters were adjusted (equally for the DMSO and BAPTA-AM alone) to compensate for the relatively lower GFP intensity. Vesicles parameters were set to width between 5.5 and 14 pixels, and intensities of 4500 gray levels above local background were identified.

“p62 aggregates per cell” were also determined using the Transfluor® module of MetaXpress®. Images were captured at ×40 magnification. For the Cb cells, “p62 aggregates” were defined and identified as those structures between 8 and 12 pixels in width, and with an intensity of at least 20,000 gray levels above local background. Nuclei parameters were set to a width of between 30 pixels and 70 pixels, and an intensity of at least 500 gray levels above local background. For the NPCs, p62 aggregates were defined and identified as those structures between 1 and 25 pixels in width, and with an intensity of at least 50,000 gray levels above local background. Nuclei parameters were set to a width of between 54 pixels and 107 pixels, and an intensity of at least 2000 gray levels above local background.

Co-localization Analysis

All like-stained images within a given experiment were taken with the same image acquisition settings and in the same imaging session. Relative degree of co-localization was determined using ImageJ/Fiji and the coloc2 plugin (22, 23), with the following details. Images were captured at ×40 magnification. Nuclei were first identified by applying a threshold to the DAPI channel and then employing the “analyze particles” module. Cell bodies were then identified on the GFP-LC3 channel using a convolve filter to create a cell bodies mask, from which the identified nuclei were then subtracted to create a region of interest “biomask.” On each channel to be analyzed, the “subtract background” module was used with a defined rolling ball radius, which ranged from 10 to 30 pixels. This setting depended on the intensity of the set of images, which sometimes varied from experiment to experiment, but was uniformly applied to all images within each experiment. The coloc2 plugin was then applied to the background-subtracted channels, with the biomasks as guides. Pearson's correlation coefficients were determined for the “above threshold” signal, and these values were used to assess the relative degree of co-localization within an experiment. Pearson's correlation coefficients were determined for each image within a set of images (usually at least 10 images per genotype/treatment group), and these per image values were then averaged to determine the mean Pearson's correlation coefficient for each group. A negative Pearson's correlation coefficient was interpreted to indicate that the above threshold signal on each channel being analyzed was on average found in mutually exclusive pixels.

SERCA Immunostaining Threshold Analysis

Threshold analysis was performed on ∼100 cells (from four experiments) in the Simple PCI imaging package. The CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cell images, taken with identical settings, were opened, and the threshold was set as the fluorescence intensity equal to the CbCln3+/+ mean gray levels. The number of visible cells once the threshold was set were then counted.

Immunoblotting and Densitometry

For preparation of cell lysates (except for total p62 analysis), lysis buffer contained 50 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.2% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors (cOmplete, Mini catalog no. 11836153001; Roche Applied Science) and phosphatase inhibitors (PhosSTOP catalog no. 04906845001; Roche Applied Science). For total p62 analysis, cell lysates were prepared with the following lysis buffer: 50 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 1% SDS, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors as above. Protein quantification was performed using a BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, catalog no. 23225). 10 μg of total protein were typically loaded (except for BiP experiments, 2 μg of total protein was loaded) for separation by SDS-PAGE using Bistris NuPAGE 10% or 4–12% gels (Life Technologies, Inc.), as appropriate for the individual experiments, and proteins were subsequently transferred to 0.2-μm pore-size nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad, catalog no. 162-0097). Blots were incubated in primary antibody overnight and then probed with secondary antibody (anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP) (GE Healthcare catalog no. NA931), anti-rabbit-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology catalog no. sc-2313), or anti-guinea pig-HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch catalog no. 706-035148), all used at 1:5000 dilution and incubated for 1 h at room temperature). Western Lightning® Plus-ECL, enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (PerkinElmer Life Sciences catalog no. NEL103001EA), was used to develop blots, which were then exposed to Amersham Biosciences HyperfilmTM ECL (GE Healthcare) for 4–5 exposure times, and films were developed using an X-Omat automatic processor. Blots were digitally scanned using a GS800 calibrated densitometer scanner, and bands were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). GFP antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology catalog no. sc-9996) was used at 1:1000 dilution; SERCA 2 antibody (Abcam catalog no. ab3625) was used at 1:10,000 dilution; GAPDH antibody (Abcam catalog no. ab9485) was used at 1:5000; BiP antibody (Abcam catalog no. 21685) was used at 1:10,000; α-tubulin antibody (Sigma catalog no. T6199) was used at 1:1000 dilution; and p62/SQSTM1 antibody (Progen Biotechnik catalog no. GP62-C) was used at 1:5000 dilution. LC3 antibody (Sigma catalog no. L8918) was used to probe NPC blots at a 1:1000 dilution, and β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology catalog no. sc81178) was used at 1:1000 dilution.

Ca2+ Measurements

Cells grown on 8-well chamberslides (Ibidi) were loaded with 5 μm Fura-2AM (Invitrogen), and all Ca2+ measurements were recorded and analyzed according to Lloyd-Evans et al. (25). To measure specific subcellular Ca2+ pools, the following compounds were used: GPN (Alfa Aesar), ionomycin (Merck), rotenone (Sigma), thapsigargin (Sigma), and caffeine (Sigma).

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, statistical analysis of image-based data were performed using one-way or two-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison's tests to determine p values, as indicated in each figure legend. For statistical analysis of blot densitometry data, ANOVA or a two-tailed Student's t test was used to determine statistical significance, as indicated in each figure legend. Statistical testing and graph preparation were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Relative degree of significance is indicated in figures by the number of asterisks and is defined in each figure legend.

Gene Expression Analysis of SERCA-encoding Genes

Affymetrix gene expression analysis of CbCln3 cells has been previously reported (20). Raw microarray data (GSE24368) are publicly available at the NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Results

Cell-based Screening Assay Identifies Autophagy Modifiers in CbCln3Δex7/8 Cells

We previously established a panel of wild type and homozygous cerebellar neuronal progenitor cells derived from Cln3Δex7/8 mice, which were engineered to precisely model JNCL by recapitulating the major genetic defect found in JNCL patients (CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells) (7, 26). Further work with the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells identified elevated steady-state levels of LC3-II, which corresponded to an increased number of autophagosomes (17). To develop a high throughput version of this cell-based assay for further analysis of this phenotype and to identify autophagy modifiers in these cells, we subsequently established derivative wild type and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8 cell lines stably expressing a GFP-LC3 transgene. Using these reporter lines, we developed a miniaturized assay to quantify the mean GFP-LC3 vesicle number per cell, which was consistently ∼1.5-fold higher in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 1).

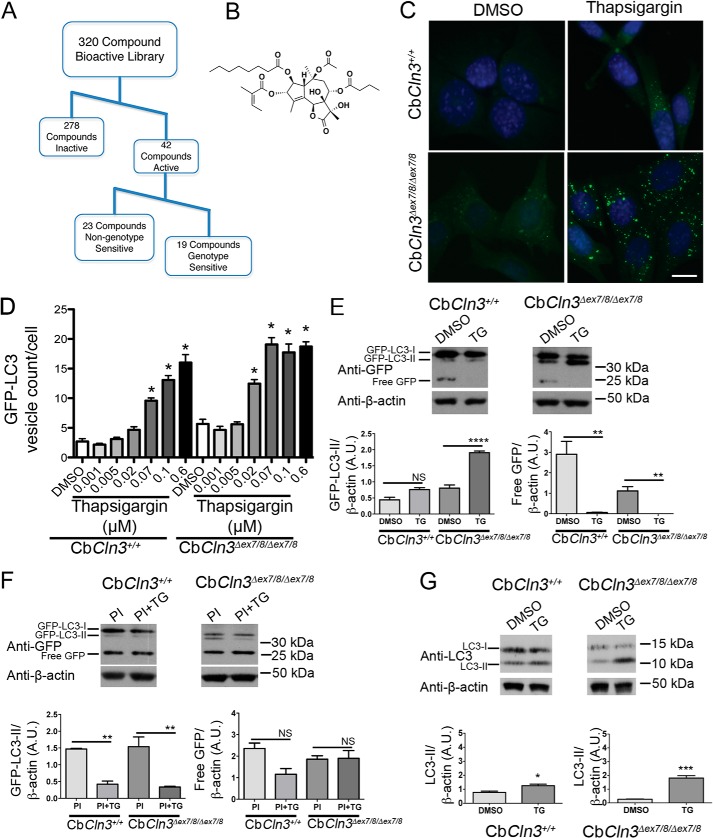

FIGURE 1.

CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cell lines are more sensitive to thapsigargin treatment than CbCln3+/+ cells. A, workflow for hit identification and categorization of activities for our primary screening data is shown. B, structure of thapsigargin, a sesquiterpene lactone and a specific, noncompetitive inhibitor of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase is shown. C, representative epifluorescence images are shown of wild type (CbCln3+/+) and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 (green) following DMSO or thapsigargin treatment. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm D, GFP-LC3 vesicle counts per cell were quantified and plotted in the bar graph from dose-response analysis of thapsigargin (0.001–0.6 μm) in the CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. Mean values are from N of 9–12 images per genotype/treatment (∼4–12 cells per image) from a representative experiment. Error bars represent S.D. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001) and a significant interaction effect (p < 0.0001). Statistical significance from post hoc Bonferroni analysis is shown (*, p < 0.0001). E, representative immunoblots probed with a GFP antibody are shown. Triplicate lysates prepared from CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells were assessed for relative forms of the GFP-LC3 transgene, including the cytoplasmic form (GFP-LC3-I), the autophagosome-associated form (GFP-LC3-II), and for free GFP. TG = thapsigargin and PI = protease inhibitors. Blotting for β-actin levels was used as a load control. Positions of the molecular weight standards are shown to the right of the immunoblots. kDa = kilodaltons. F, results from densitometry of GFP-LC3-II and free GFP bands on triplicate lysates are shown in the bar graphs. Statistical significance (Bonferroni) for the indicated comparisons (lines) are shown. NS, not significant, ****, p < 0.0001; **, p < 0.01. For E and F, samples for these analyses were run on the same blot; intervening replicate lanes were cropped from the blot images shown. G, representative immunoblots probed with an LC3 antibody to detect endogenous LC3-I and LC3-II are shown, and results from densitometry of LC3-II on triplicate lysates are shown in the bar graphs. Samples for this analysis from each cell line were run on separate blots; replicate lanes are cropped out. Statistical significance (Student's t test) values are shown. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. A.U., arbitrary units.

To test the GFP-LC3 assay in the CbCln3 set of cells, we screened a subset of known bioactive compounds from a library of Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs and natural products (see under “Experimental Procedures”). Applying a z score cutoff of greater than ±2, we identified 42 compounds that significantly increased the GFP-LC3 vesicle number per cell (z score ≥2), in either the CbCln3+/+ cells or in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, and 29 of these compounds were significant hits in both sets of cells (supplemental Table 1). Among the significant hits were multiple compounds that were predicted to affect proteolysis, including CA-074-Me, a cathepsin B inhibitor (27), NapSul-Ile-Trp-CHO, a cathepsin L inhibitor (28), and two well known calpain and proteasomal inhibitors (MG-132 and Ac-Leu-Leu-Nle-CHO). Furthermore, we also identified multiple compounds with a predicted role in ion regulation (31% of the hits), and most notable among these were Ca2+ channel blockers (supplemental Table 1). The ability of Ca2+ channel blockers to modulate autophagy is now well documented, although the precise mechanisms by which Ca2+ plays a role in the autophagy pathway remains incompletely understood (18, 29, 30). We also identified compounds that were predicted to target protein kinase C (PKC) and NF-κB signaling pathways, were inducers of apoptosis, DNA topoisomerase inhibitors, protein synthesis inhibitors, antioxidants, or cell cycle inhibitors. Among our hits were 16 compounds that had previously been identified in a similar GFP-LC3 screen in neuroglioma cells (supplemental Table 1) (18).

Among our 42 significant hits in the primary screen, 19 compounds were identified that appeared to display more or less activity in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, compared with the wild type cells (CbCln3+/+) (Fig. 1; supplemental Table 1; see under “Experimental Procedures” for a description on the determination of potential genotype sensitivity). We speculated that further investigation of the target pathways in which genotype-sensitive compounds were active could provide important clues to the altered autophagosomal biology we had observed in this JNCL model system. A total of 8 of the 19 genotype-sensitive compounds were among those predicted to target ion channels (∼42% compared with 13/42, or 31%, in the total hit list). A follow-up dose-response analysis was then performed on seven of the potentially genotype-sensitive compounds, with a particular emphasis on the ion channel targeting compounds. In all cases, the retested compounds again showed activity in the assay, although typically this was mostly observed only at the highest doses where substantial toxicity was also observed (supplemental Fig. 1). In particular, thapsigargin reproducibly and robustly displayed genotype-sensitive activity across multiple doses, and it was therefore the major focus of our further studies (supplemental Fig. 1).

Autophagy Pathway in Homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8 Cells Is Highly Sensitive to Thapsigargin Treatment

The natural product thapsigargin, a sesquiterpene lactone (Fig. 1A), is a highly specific, noncompetitive inhibitor of the of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) (31). SERCA is responsible for the uptake of Ca2+ into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and thapsigargin is a known modulator of autophagy (18, 32, 33). Initially reported in some cell systems to stimulate autophagy (34), thapsigargin has also more recently been suggested to inhibit autophagosome maturation, which also leads to an accumulation of autophagosomes (32). Intriguingly, CLN3 knockdown cells have previously been reported to be sensitive to thapsigargin-induced cell death and to display perturbed Ca2+ influx following membrane depolarization (35, 36).

To further investigate the increased sensitivity of the autophagy phenotype in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells to thapsigargin treatment, we performed a series of higher resolution image analysis studies and GFP-LC3 immunoblotting. GFP-LC3 lipidation, detected as the faster mobility GFP-LC3-II isoform by immunoblot, correlates with the degree of autophagosomal membrane association of this protein (19). Validating our screening results, GFP-LC3 puncta accumulation in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells was particularly responsive to thapsigargin treatment, which showed an EC50 dose of ∼20 nm. The thapsigargin EC50 dose on GFP-LC3 puncta formation in CbCln3+/+ cells was ≥70 nm (Fig. 1D). Notably, thapsigargin doses in this range have previously been shown in healthy cells to reduce but not completely abolish SERCA activity (37). The effect of low dose thapsigargin treatment on the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells was also observed by immunoblot analysis, where 100 nm thapsigargin treatment increased lipidated GFP-LC3-II levels in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, but GFP-LC3-II levels were not significantly altered by 100 nm thapsigargin in the wild type cells (Fig. 1E). A similar effect was also observed on levels of endogenous LC3-II following thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 1G).

To ascertain whether thapsigargin was inhibiting or stimulating autophagic flux in our cell system, we also tested its effects on GFP-LC3-II and free GFP levels by immunoblot following pretreatment with protease inhibitors. If thapsigargin stimulates autophagy in this system, it should increase GFP-LC3-II and free GFP levels compared with protease inhibitors alone (19). As compared with protease inhibitor treatment alone, thapsigargin following protease inhibitor pretreatment significantly reduced GFP-LC3-II levels in both CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells and had no significant effect on free GFP in either set of cells (Fig. 1F). Therefore, these data suggest that thapsigargin inhibits autophagic flux in our mouse cerebellar cell system.

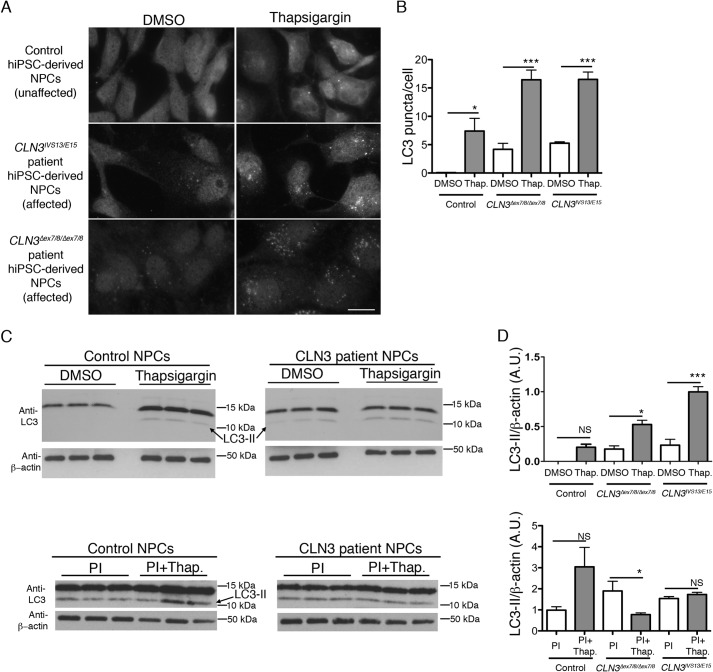

Human CLN3 Patient Neural Progenitor Cells Display Thapsigargin-responsive Abnormal Autophagosome Accumulation

We have recently established a set of human neural progenitor cell lines (NPCs) by reprogramming of JNCL (CLN3) patient skin fibroblasts and unaffected control skin fibroblasts to generate iPSCs, which were then differentiated into a neurally committed lineage (11). Importantly, we therefore next sought to test whether the effects of thapsigargin treatment on autophagosome accumulation in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 murine cells would also be observed in CLN3 patient NPCs. In DMSO-treated control NPCs, the endogenous LC3 immunofluorescence signal was almost entirely cytoplasmic, with only occasional observations of LC3-positive puncta (Fig. 2A). To the contrary, CLN3 patient NPCs treated with DMSO vehicle displayed clear LC3-positive puncta in addition to the low level cytoplasmic signal (Fig. 2, A and B). Upon treatment of the control and CLN3 patient NPCs with low-dose thapsigargin (100 nm), we observed significant increases in the degree of punctate LC3 immunostain, which was more dramatic in the CLN3 patient cells (Fig. 2, A and B). Similarly, by immunoblot, the lipidated form of LC3, LC3-II, was elevated in CLN3 patient NPCs and by thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 2, C and D). To assess whether the thapsigargin effect was through a stimulation or inhibition of the autophagy pathway, we also assessed LC3-II levels following protease inhibitor treatment (19). As we observed in the mouse cerebellar cell system, thapsigargin following protease inhibitor pretreatment did not significantly increase LC3-II levels in the human NPCs, as compared with protease inhibitor treatment alone (Fig. 2, C and D). Therefore, these results suggest that the autophagy pathway is similarly affected in our murine neuronal precursor cell model and in CLN3 patient NPCs and that thapsigargin inhibits autophagic flux in these cell systems.

FIGURE 2.

Thapsigargin and autophagy analysis in human iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells from control and JNCL-affected subjects. A, representative epifluorescence images are shown from control (unaffected) and affected JNCL subject (CLN3IVS13/E15 and CLN3Δex7/8/Δex7/8) human iPSC-derived NPCs, immunostained to detect endogenous LC3. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, bar graph depicts the image analysis-based quantification of LC3-stained puncta (shown as mean LC3 puncta per cell) in the control and JNCL (CLN3) patient NPC lines, DMSO, or thapsigargin-treated (Thap). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001) and a significant interaction effect (p < 0.01). Statistical significance from post hoc Bonferroni analysis for the indicated comparisons is shown (**, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001). Mean values were from 5 to 6 images per genotype/treatment (∼10–15 cells per image). C, representative immunoblots are shown for endogenous LC3 (anti-LC3; ∼11-kDa band = LC3-I, ∼14-kDa band = LC3-II) level analysis in cell lysates. Top panels are from DMSO or thapsigargin-treated control NPCs and CLN3 patient NPCs. Bottom panels are from protease inhibitor-treated or thapsigargin plus protease inhibitor-treated control and CLN3 patient NPCs. Three replicate lysate samples are shown for the indicated cell lines and treatment conditions. D, bar graphs depict results of densitometry performed on the ∼14-kDa band representing LC3-II, normalized to β-actin, and averaged from the indicated replicate lysates. Statistical significance (Bonferroni) for the indicated comparisons (lines), are shown. NS = not significant; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. A.U., arbitrary units; PI, PI = protease inhibitor. Error bars represent S.E.

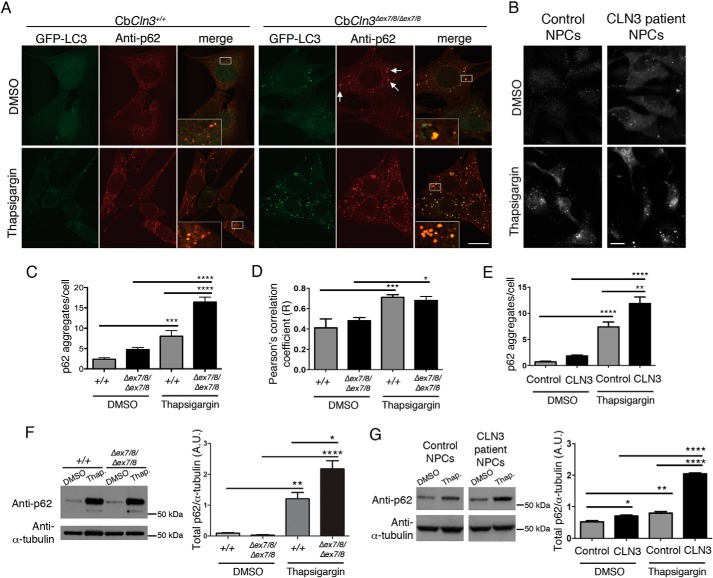

Dissection of Autophagy Defects in Neuronal Cell Culture Models of JNCL

p62, also known as SQSTM1, binds to LC3 to facilitate autophagolysosomal turnover of accumulated polyubiquitinated substrates. It is therefore often used as an additional marker to monitor autophagolysosomal turnover and to assess cargo recruitment to autophagosomes by monitoring co-localization of p62 with LC3- or GFP-LC3-positive autophagosomes (19). We next analyzed p62 in our set of GFP-LC3 wild type cells and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells and in control and CLN3 patient-derived NPCs, with and without thapsigargin treatment. In both the murine and the human neuronal cell systems, the p62 immunofluorescence signal was mostly in punctate vesicles. Quantification of the p62 aggregates revealed that both the Cln3/CLN3 mutation and thapsigargin treatment caused significant increases in the number of p62 aggregates per cell (Fig. 3, A–C and E). Assessment of p62 aggregate overlap with GFP-LC3-positive vesicles in the mouse cell system indicated that some of these p62-positive structures were indeed co-localized with the autophagosomal marker (zoomed insets in Fig. 3A). Moreover, the degree of p62 and GFP-LC3 overlap was increased by thapsigargin treatment, but interestingly, the correlation of the two signals was not significantly altered by Cln3 mutation (Fig. 3, A and D). The p62 levels in cerebellar cell and human NPC lysates were also increased by immunoblot analysis following thapsigargin treatment, with a higher increase observed in the cells bearing Cln3/CLN3 mutations versus wild type controls (Fig. 3, F and G). Taken together, these data suggest that neither thapsigargin nor Cln3 mutation causes an obvious defect in p62-autophagosomal recruitment.

FIGURE 3.

Thapsigargin induces p62/SQSTM1 accumulation in mouse cerebellar cells and human NPCs. A, representative confocal images are shown for p62 immunostaining (anti-p62, red) of wild type (CbCln3+/+) and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 (green), following DMSO or thapsigargin treatment. Zoomed insets are shown in the white-boxed regions in the merge panels to better display the extent of overlap of the GFP-LC3 and p62 signals (orange/yellow). White arrows point to examples of large p62-positive aggregates that were frequently observed in the homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, even in the absence of thapsigargin. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, representative images are shown for p62 immunostaining of control and CLN3 patient NPCs, DMSO, or thapsigargin-treated. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, p62-stained aggregates were quantified by image-based analysis, as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and results from a representative experiment are displayed in the bar graph. Wild type (+/+), homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 (Δex7/8/Δex7/8). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype (p < 0.001) and treatment (p < 0.0001) and a significant interaction effect (p < 0.01). Statistical significance from post hoc Bonferroni analysis for the indicated comparisons is shown (***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001). D, Pearson's correlation coefficients for co-localization analysis (co-loc2, ImageJ/Fiji) of p62-GFP-LC3 signal overlap in wild type (+/+) and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 (Δex7/8/Δex7/8) cells, treated with DMSO or thapsigargin (Thap), are plotted in the displayed bar graph. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of treatment only (p < 0.0001). Statistical significance from post hoc Bonferroni analysis for the indicated comparisons is shown (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). For C and D, error bars represent S.E. n = mean values from 9 to 12 images per genotype/treatment (∼4–8 cells per image), from a representative experiment. E, p62-stained aggregates in control and CLN3 patient NPCs were quantified by image-based analysis, as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and results from a representative experiment are displayed in the bar graph. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of genotype (p < 0.001) and treatment (p < 0.0001) and a significant interaction effect (p < 0.05). Statistical significance from post hoc Bonferroni analysis for the indicated comparisons is shown (**, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001). Mean values were from 7 to 8 images per genotype/treatment (∼15 cells per image). F and G, representative immunoblots of total p62 levels in cell lysates from DMSO or thapsigargin-treated (Thap.) wild type cells (+/+) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Δex7/8/Δex7/8) (F) and DMSO or thapsigargin-treated (Thap.) control and CLN3 patient NPCs (G) are shown. Samples for this analysis were run on the same blot; intervening replicate lanes were cropped from the blot images shown in G. In the Cb cell lysates, in addition to the expected ∼62-kDa band labeled with the anti-p62 antibody, an ∼52-kDa band was also observed following thapsigargin treatment. The identity of this band is unknown. The bar graphs depict results of densitometry performed on the ∼62-kDa band, normalized to α-tubulin, averaged from three replicate lysates, from a representative experiment. A.U., arbitrary units. Error bars represent S.E. Bonferroni analysis for the indicated comparisons are shown (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001).

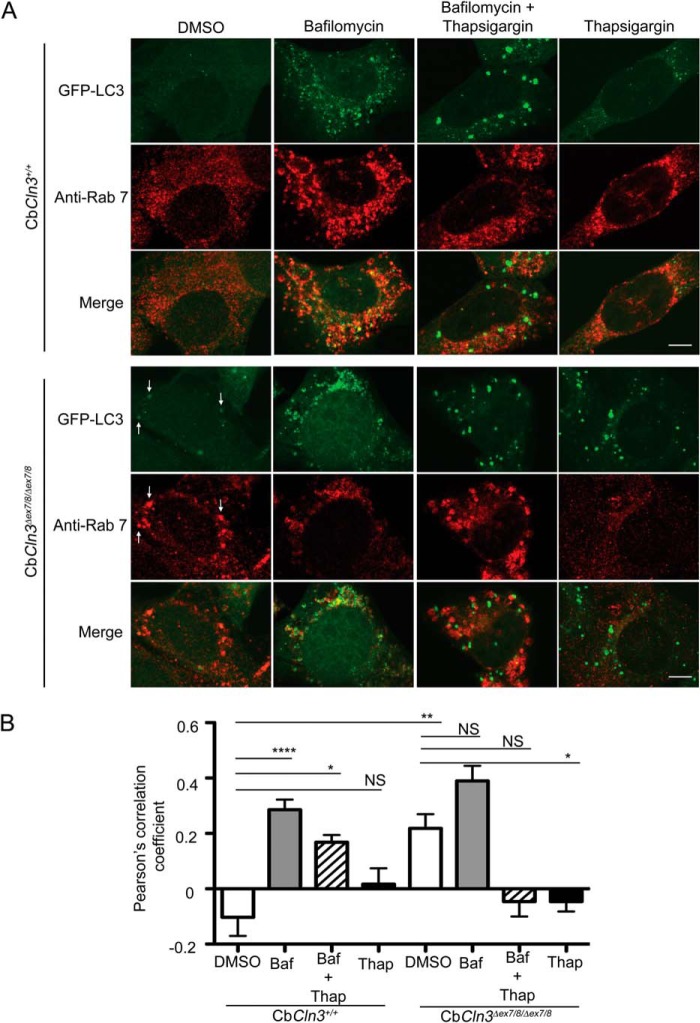

It has been proposed that thapsigargin disrupts autophagosome maturation by interfering with Rab7-mediated autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion (32), perhaps even upstream of Rab7, inhibiting closure of the pre-autophagosomal structure (37). Interestingly, CLN3 has also been proposed to mediate Rab7 function, and overexpressed CLN3 protein has been reported to co-immunoprecipitate with a Rab7-interacting lysosomal protein complex (39). To extend our analyses, particularly given the possibility that CLN3 and thapsigargin share some mechanism, and to further rule out the possibility that the observed effects were not due to an up-regulation of autophagy, we next examined the effects of thapsigargin treatment and Cln3 mutation on Rab7 autophagosomal localization in our cerebellar cell system, with and without bafilomycin, a V-ATPase inhibitor that blocks lysosomal acidification and fusion.

Using the pre-determined bafilomycin dose that appeared to block autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion in both CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (1 μm, 24-h incubation; data not shown), we analyzed Rab7-GFP-LC3 co-localization in bafilomycin-treated cells and those co-treated with thapsigargin. Bafilomycin treatment alone did not significantly alter the degree of Rab7-GFP-LC3 co-localization in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with that observed in DMSO control treatment (Fig. 4). However, the CbCln3+/+ cells showed a dramatic increase in GFP-LC3 vesicle accumulation and a rise in the degree of Rab7-GFP-LC3 co-localization with bafilomycin treatment versus DMSO control (Fig. 4, A and B). Conversely, thapsigargin treatment of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells dramatically reduced the degree of Rab7-GFP-LC3 co-localization compared with DMSO control, essentially abolishing any overlap of these two markers (Fig. 4, A and B). Thapsigargin-bafilomycin co-treatment also dramatically reduced Rab7-GFP-LC3 co-localization in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, whereas the co-treatment yielded an intermediate effect on the degree of Rab7-GFP-LC3 co-localization in the CbCln3+/+ cells. Notably, with only DMSO treatment, the degree of co-localization of Rab7 with GFP-LC3 in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells was significantly greater than that observed in the CbCln3+/+ cells. Taken together, these results suggest that thapsigargin acts upstream of Rab7 association with the autophagosome, whereas the common JNCL-associated Cln3 mutation affects a step downstream of Rab7 association with the autophagosome.

FIGURE 4.

Pharmacological dissection of autophagosome maturation in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. A, representative confocal images are shown for Rab7 (Anti-Rab7, red) immunostaining of wild type (CbCln3+/+) and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 (green), following DMSO or bafilomycin (1 μm, 24 h), thapsigargin (0.1 μm, 24 h), or combined treatment (1 μm bafilomycin and 0.1 μm thapsigargin, 24 h). Settings for confocal image capture were identical across the entire set of images. Enhanced contrast to images on the independent channels was applied uniformly within a given treatment set, but differed for the treatments (DMSO and Thapsigargin images were identically enhanced, and Bafilomycin and Bafilomycin + Thapsigargin images were identically enhanced). This was necessitated by large changes in the overall signal intensities due to the drug treatments and to ensure staining and degree of signal overlap could be visualized in the representative images shown. Scale bar, 5 μm. Note that bafilomycin treatment sensitized CbCln3+/+ cells to thapsigargin, mimicking the effect of the Cln3 mutation on thapsigargin response. To aid in visualization of the extent of co-localization in some panels, white arrows point to examples of structures with signal overlap. B, Pearson's correlation coefficients for automated co-localization analysis (co-loc2, ImageJ/Fiji) of Rab7-GFP-LC3 signal overlap in wild type and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, treated with DMSO, bafilomycin (Baf, 1 μm, 24 h), thapsigargin (Thap, 0.1 μm, 24 h), or combined treatment (Baf + Thap, 1 μm bafilomycin and 0.1 μm thapsigargin, 24 h), are plotted in the displayed bar graph. Bafilomycin significantly increased the Pearson's correlation coefficient compared with the virtual lack of co-localization observed in the DMSO-treated CbCln3+/+ cells (****, p < 0.0001). Intriguingly, however, bafilomycin did not significantly change the Pearson's correlation coefficient in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with that determined in DMSO-treated CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, which was significantly higher than DMSO-treated CbCln3+/+ cells (**, p < 0.01). No co-localization of Rab7 signal with GFP-LC3 was observed in thapsigargin-treated CbCln3+/+ cells or CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, and bafilomycin + thapsigargin co-treated CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. Error bars represent S.E. n = mean values from 9 to 12 images per genotype/treatment (∼4–8 cells per image), from a representative experiment. *, p < 0.05; NS, not significant. Statistical significance values shown are from Bonferroni post hoc following two-way ANOVA (p < 0.0001 interaction, p < 0.0001 treatment).

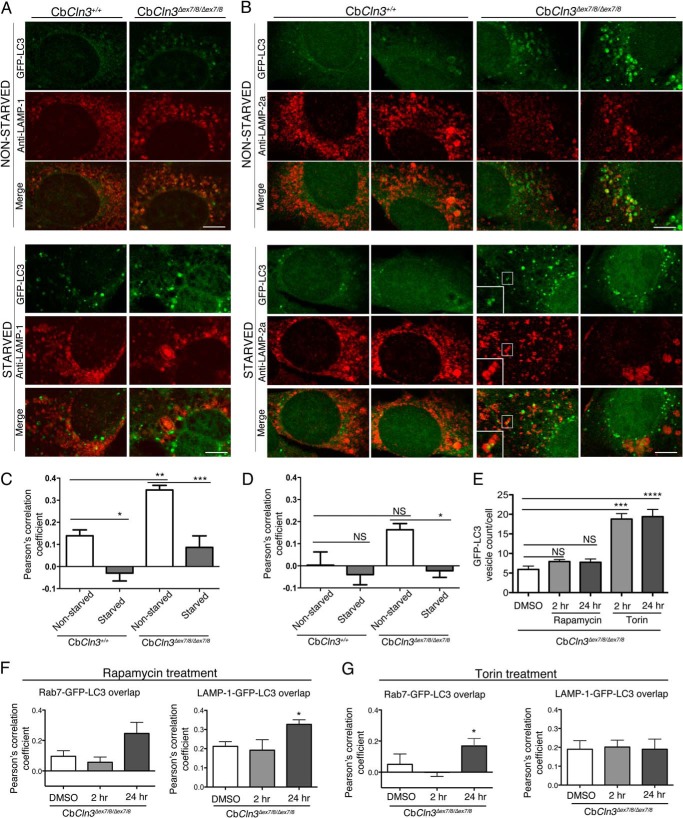

To further analyze the impact of Cln3 mutation on late-stage maturation of autophagosomes, we next analyzed the relative degree of GFP-LC3 overlap with the additional late endosomal/lysosomal markers, LAMP-1 and LAMP-2a, in fixed and pH-neutralized cell preparations to ensure visualization of GFP in acidic compartments (19). As seen for Rab7, we observed a significant increase in the relative degree of LAMP-1 overlap with GFP-LC3 signal in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, compared with that observed in CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 5, A and B). LAMP-2a-GFP-LC3 overlap was also significantly greater in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with the CbCln3+/+ cells. Notably, however, the overall degree of LAMP-2a-GFP-LC3 overlap was lower than that observed for the other markers in our mouse cerebellar cell system. We next tested the effect of starvation to further determine whether the relatively increased degree of Rab7-GFP-LC3 overlap observed in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells reflected an accumulation of amphisomes (post-late endosome fused autophagosomes) A 1-h starvation robustly eliminated the Rab7-GFP-LC3 (data not shown), LAMP-1-GFP-LC3, and LAMP-2a-GFP-LC3 overlap in both CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 5). Occasional Rab7-, LAMP-1-, or LAMP-2a-positive puncta were noted to overlap with GFP-LC3 puncta or to be in close proximity to GFP-LC3 puncta in the starved cells, particularly in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, but these were a minority of the total analyzed structures in our co-localization analysis (see Fig. 5, zoomed inset for an example). Notably, LAMP-2a, a protein critical for chaperone-mediated autophagy (40, 41), appeared to be altered in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with that observed in CbCln3+/+ cells. The majority (∼63%) of nonstarved CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells displayed non-GFP-LC3 overlapping LAMP-2a signal that was a combination of lightly stained punctate structures and peripherally located LAMP-2a-positive vesicles, but ∼37% of the nonstarved CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells had strongly stained LAMP-2a-positive vesicles that strongly overlapped with GFP-LC3 signal (Fig. 5). The effects of longer term starvation could not be tested due to poor cell survival regardless of genotype. We therefore also analyzed Rab7-GFP-LC3 and LAMP-1-GFP-LC3 overlap in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells following 2- and 24-h treatment periods with the well known mTOR inhibitors, rapamycin and torin, which stimulate autophagy (19). For both rapamycin and torin, we observed a slight reduction in the extent of Rab7-GFP-LC3 overlap at the 2-h time point, but this effect was not maintained at the 24-h time point (Fig. 5, E and F). Overall, there was no effect or a slight increase in overlap of the Rab7 and LAMP-1 markers with GFP-LC3 at the 24-h time point (Fig. 5, E and F). Together, these observations further support the hypothesis that Cln3 mutation in cerebellar neuronal progenitor cells predominantly impacts late-stage autophagosome maturation, although it does not completely block the pathway.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of late endosome/lysosome overlap with GFP-LC3-labeled autophagic pathway structures. Representative confocal images are shown for LAMP-1 (Anti-LAMP-1, red) (A) or LAMP-2a (Anti-LAMP-2a, red) (B) immunostaining of wild type (CbCln3+/+) and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 (green), during normal growth (nonstarved) and following a 1-h starvation (starved). Settings for confocal image capture and enhanced contrast to images were applied identically across the entire set of images for each given marker. For LAMP-1 immunostaining, cells were methanol/acetone-fixed, although for LAMP-2a-immunostaining, cells were 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed and subsequently permeabilized with 0.2% saponin (see “Experimental Procedures” for more detailed staining methods). For LAMP-2a-immunostained cells, two representative cells are shown for each genotype and treatment condition, to demonstrate the significant cell-to-cell heterogeneity that was prominent for this marker, particularly in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. White boxes demarcate zoomed regions in insets. Scale bar, 7.5 μm. C, D, F, and G, Pearson's correlation coefficients for automated co-localization analysis (co-loc2, ImageJ/Fiji) of LAMP-1-GFP-LC3 signal overlap (C), LAMP-2a-GFP-LC3 signal overlap in wild type and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (D), Rab7-GFP-LC3 and LAMP-1-GFP-LC3 signal overlap following rapamycin treatment of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (F), and Rab7-GFP-LC3 and LAMP-1-GFP-LC3 signal overlap following torin treatment of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (G) are plotted in the displayed bar graphs. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; NS = not significant. Significance values shown are from Bonferroni analysis. For both C and D, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant genotype effect (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively) and a significant treatment effect (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.01, respectively). E, image-based quantification of GFP-LC3 vesicle count per cell is shown for CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells treated with DMSO only or with rapamycin (2 μm) or torin (10 μm) for either a 2-h (2 hr) or 24-h (24 hr) treatment period. Data from the different drugs were analyzed separately. Significance values shown are from Bonferroni post-hoc analysis following one-way ANOVA. NS, not significant, ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. For all analyses shown in bar graphs, error bars represent S.E. n = mean values from 9 to 12 images per genotype/treatment (∼4–8 cells per image), from representative experiments.

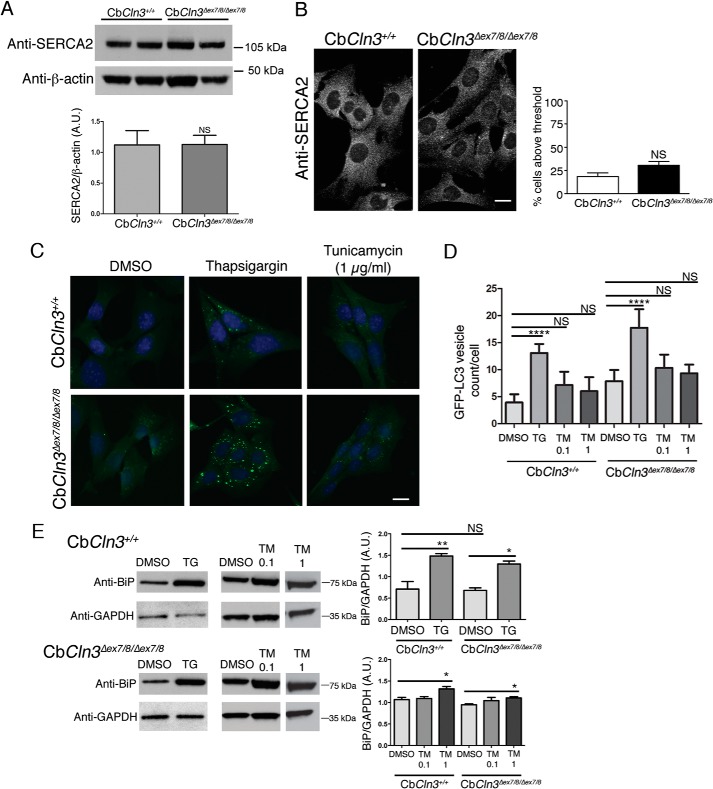

Sensitivity of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 Cells to Thapsigargin Treatment Is Not Due to a General ER Stress Response, but Is Ca2+-related

Possible explanations for the thapsigargin sensitivity of our CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells include altered SERCA expression levels, underlying ER stress, and disruption of normal Ca2+ homeostasis, compared with wild type cells, and we next sought to test each of these possibilities. SERCA2 expression (the major brain isoform of SERCA) (43, 44) at both the RNA and protein levels was not different in CbCln3+/+ versus CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Table 1; Fig. 6A) (20). SERCA immunostaining was also not obviously different in CbCln3+/+ versus CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 6B). Moreover, treatment with tunicamycin, an inhibitor of N-acylglucosamine phosphotransferase, only slightly increased GFP-LC3 vesicle counts in both CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 6, C and D). We have previously reported that protein-disulfide isomerase levels and localization were unchanged in the mutant CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, compared with the wild type cells (20). Consistent with those data, we also found that BiP levels were not altered in untreated or DMSO-treated CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, compared with the wild type cells (data not shown and Fig. 6E). As expected, both thapsigargin and tunicamycin induced an increase in BiP levels, but this effect was similar in both the CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 6E). Therefore, although an activation of ER stress may be a component of the downstream effects of thapsigargin, the sensitivity of the autophagic response of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells to thapsigargin treatment is unlikely to be primarily mediated by ER stress.

TABLE 1.

Relative expression levels of SERCA-encoding genes in CbCln3 cells

Relative expression levels for Affymetrix probes representing the three SERCA-encoding genes, Atp2a2, Atp2a1, and Atp2a3, are shown. Consistent with the neural origin of the CbCln3 cells, the highest expression is observed for Atp2a2, which encodes the major brain isoform SERCA2. No genotypic difference in relative expression levels across the probe sets is observed.

| Affymetrix Probe ID | CbCln3+/+expression level ± S.D. | CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 expression level ± S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, cardiac muscle, slow twitch 2, Atp2a2 | ||

| 1452363_a_at | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.2 |

| 1427250_at | 13.5 ± 0.1 | 13.4 ± 0.1 |

| 1443551_at | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.1 |

| 1416551_at | 11 ± 0.1 | 11 ± 0.3 |

| 1427251_at | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 8.7 ± 0.2 |

| 1437797_at | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.6 |

| ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, cardiac muscle, fast twitch 1, Atp2a1 | ||

| 1419312_at | 2.5 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.01 |

| ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, ubiquitous, Atp2a3 | ||

| 1421129_a_at | 2.9 ± 0.02 | 2.9 ± 0.01 |

| 1450124_a_at | 2.4 ± 0.01 | 2.4 ± 0.03 |

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of SERCA and ER stress. A, representative immunoblots are shown for wild type (CbCln3+/+) and mutant (CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8) cells, probed with antibodies recognizing the major brain SERCA isoform, SERCA2 (Anti-SERCA2), and β-actin as a loading control. kDa, kilodaltons. Bar graph depicts densitometry results for relative total SERCA2 levels in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. Data are combined from five independent experiments, each with two to three technical replicates. Error bars represent S.E. No significant difference in SERCA2 levels was found (Student's t test). B, representative epifluorescence micrographs are shown from anti-SERCA2 immunostaining of CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. Bar graph depicts quantification of fluorescence intensity as described under “Experimental Procedures” from four independent experiments (∼100 cells/experiment/genotype). Error bars represent S.E. No significant difference in SERCA2 was found (Student's t test). C, representative epifluorescence micrographs are shown for CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells expressing GFP-LC3, treated with DMSO only (DMSO), thapsigargin (0.1 μm), or tunicamycin (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. D, bar graph depicts results of image-based quantification of GFP-LC3 vesicle counts per cell. Mean values from n = 5–10 images per genotype/treatment (∼20 cells per image) from a representative experiment are shown. Error bars represent S.D. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of genotype (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001). Statistical significance from post hoc Bonferroni analysis for the indicated comparisons is shown (****, p < 0.0001). E, immunoblot analysis for BiP (Anti-BiP) in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells examining basal levels, and levels following thapsigargin (TG) or tunicamycin (TM, 0.1 or 1 μg/ml) treatment. Representative blots are shown. Replicate lysates for the thapsigargin analyses were run on the same blot, and replicate lanes were cropped for the figure. Replicate lysates for tunicamycin analyses were run on the same blot for a given cell line, and replicate lanes were cropped for the figure. GAPDH (Anti-GAPDH) was used as loading control, and densitometry was performed on the replicate lysates, with BiP normalized to GAPDH. Bonferroni analysis for the indicated comparisons is shown (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). Error bars represent S.E. For A–E, A.U., arbitrary units; NS, not significant; kDa, kilodaltons, micrograph scale bars are 10 μm.

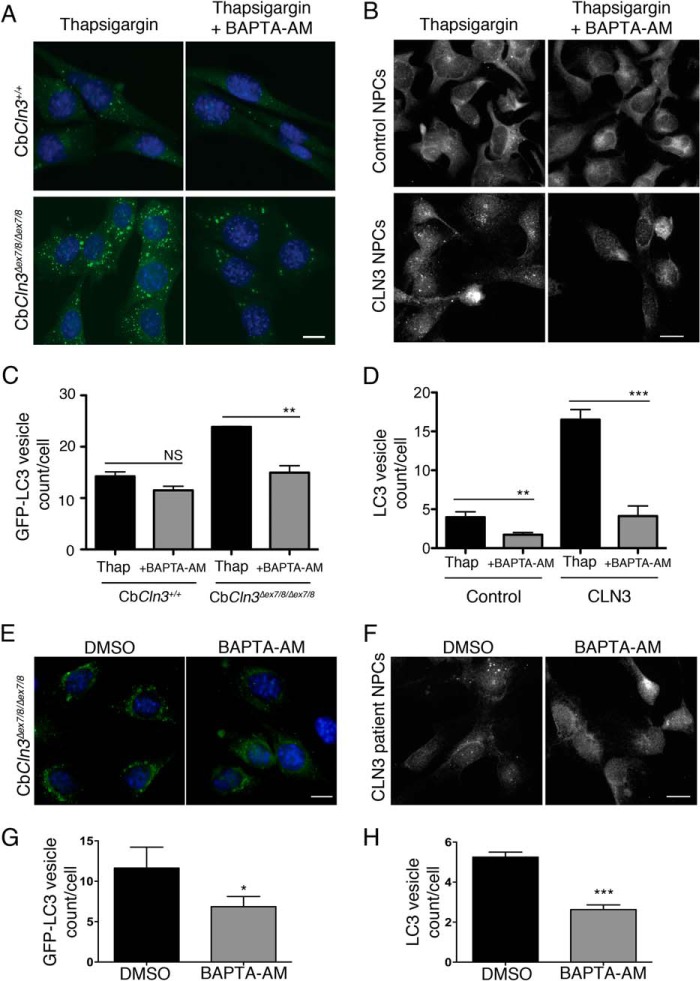

To next test whether the thapsigargin effect on GFP-LC3 vesicle accumulation in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, and on endogenous LC3 vesicle accumulation in control and CLN3 human NPCs, was mediated via Ca2+, we again treated the cells with thapsigargin, and we also added the cytosolic Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM for the final hour of treatment. The BAPTA-AM treatment reduced the vesicle counts, suggesting that elevation in cytosolic Ca2+ levels was contributing to the autophagosome accumulation (Fig. 7, A and C). Furthermore, we also tested the effects of BAPTA-AM treatment alone in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 and CLN3 patient NPCs. As compared with DMSO, both the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 and CLN3 patient NPCs displayed significantly fewer labeled vesicles following a 1-h BAPTA-AM treatment.

FIGURE 7.

Thapsigargin effect is mediated by Ca2+. For A, B, E, and F, representative epifluorescence images are shown for wild type (CbCln3+/+) and homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 (green) (A and E) or control versus CLN3 patient NPCs immunostained for endogenous LC3 (B and F), following the indicated treatments. Images were captured for E and F with higher gain settings than those in A and B to visualize and quantify the less intensely fluorescent puncta that are typical for unstimulated (DMSO) and BAPTA-AM (1 h, 5 μm) conditions. Scale bars, 10 μm. C, D, G, and H, bar graphs depict results of image-based quantification of GFP-LC3 vesicle count per cell (C and G) or LC3 vesicle count per cell (D and H), for each indicated genotype and treatment condition. C and G, results shown are mean values from three independent experiments. Each experiment involved quantification of ∼10–20 images per genotype/treatment (∼4–12 cells per image). Error bars represent S.D. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 (Student's t test). D and H, results shown are mean values from 8 to 11 images per genotype/treatment (∼10–20 cells per image) from representative experiments. Error bars represent S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (Student's t test).

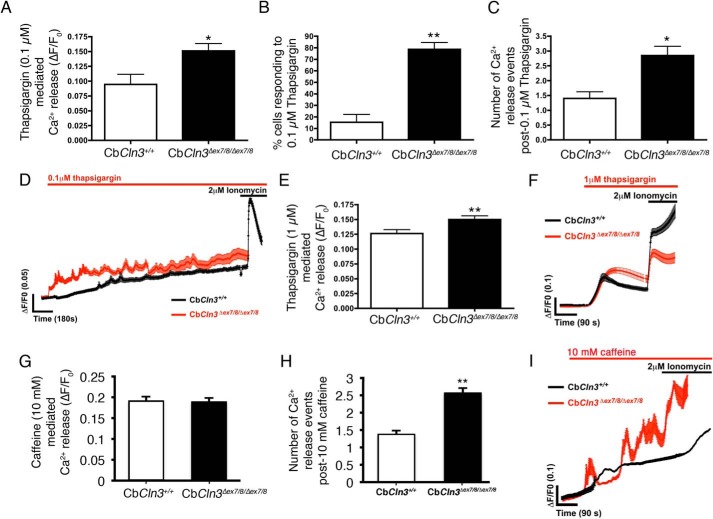

Therefore, we next sought to assess Ca2+ flux in response to thapsigargin treatment using the CbCln3 cerebellar cell system and Ca2+ ratiometric imaging with Fura-2AM. Upon addition of low-dose thapsigargin (0.1 μm), a significantly higher (∼50%) level of Ca2+ was initially released in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells versus the CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, significantly more (∼75%) of the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells in the culture population responded to this low dose of thapsigargin compared with the CbCln3+/+ (∼15%) cultured cells (Fig. 8B), indicative of an increased sensitivity of the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells to inhibition of ER Ca2+ uptake. Additional spontaneous Ca2+ spikes after low-dose thapsigargin treatment were also observed more frequently in the recordings from the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, compared with the CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 8, C and D), indicative of an inability of the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells to maintain normal cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis following mild inhibition of SERCA or that Ca2+ release from the ER channels is potentiated. We also tested higher doses of thapsigargin, observing that 1 μm also caused a slightly higher Ca2+ release in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with the CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 8, E and F), but maximal emptying of the ER and nonlysosomal Ca2+ stores with 2 μm thapsigargin (or with 2 μm ionomycin) did not significantly differ between the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 and the CbCln3+/+ cells (ΔF/F0 = ∼0.15 and 100% of cells responding, for both CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells). To further test direct ER Ca2+ release, we also monitored Ca2+ flux following 10 mm caffeine treatment. Caffeine causes a direct release of ER Ca2+ via stimulation of the ryanodine receptor (45). Again, there was no significant difference in 10 mm caffeine-mediated Ca2+ release in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, compared with the CbCln3+/+ cells suggesting the ER Ca2+ store is normal (Fig. 8G). However, the number of Ca2+ release events was increased in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, compared with the CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 8, H and I), further supporting the hypothesis that the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells handle Ca2+ flux differently than wild type cells.

FIGURE 8.

Ca2+ analysis in response to thapsigargin treatment. A, bar graph depicts Ca2+ measurements in CbCln3+/+ (white bars) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (black bars) using Fura-2AM (baseline normalized, ΔF/F0) following low-dose (100 nm) thapsigargin treatment. *, p < 0.05. B, bar graph depicts the number of cells in the fields of view that responded to 100 nm thapsigargin, expressed as a % of total cell number. **, p < 0.01. C, bar graph depicts the number of Ca2+ release events observed following 100 nm thapsigargin treatment in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. *, p < 0.05. D, fura-2AM (ΔF/F0) traces of CbCln3+/+ (black line) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (red line) with low-dose (100 nm) thapsigargin treatment are shown. Multiple releases are evident as spikes in the traces, which were frequently observed over the recording period in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells and were only occasionally observed in the CbCln3+/+ cells. Recording following 2 μm ionomycin treatment shows emptying of the remaining ER Ca2+ pool. E, bar graph depicts Ca2+ measurements in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells using Fura-2AM (baseline normalized, ΔF/F0) following 1 μm thapsigargin treatment. **, p < 0.01. F, fura-2AM (ΔF/F0) traces of CbCln3+/+ (black line) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (red line) with 1 μm thapsigargin treatment are shown. A single release at this dose was evident in the traces, which was slightly higher in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells compared with CbCln3+/+ cells. Recording following 2 μm ionomycin treatment shows emptying of the remaining ER and nonlysosomal Ca2+ stores indicating cells remain viable. Error bars represent S.E. G, bar graph depicts Ca2+ measurements in CbCln3+/+ (white bars) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (black bars) using Fura-2AM (baseline normalized, ΔF/F0) following 10 mm caffeine treatment to mobilize the ER pool from the ryanodine receptor. H, bar graph depicts the number of Ca2+ release events observed following 10 mm caffeine treatment in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. **, p < 0.01. I, fura-2AM (ΔF/F0) traces of CbCln3+/+ (black line, average from ∼100 cells) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (red line, average from ∼100 cells) with 10 mm caffeine treatment in Ca2+-free buffer are shown. Multiple releases were evident as spikes in the traces during the recording period in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. Recording following 2 μm ionomycin treatment shows emptying of the remaining ER Ca2+ pool. For Ca2+ measurements, ≥60 cells were analyzed from three to four independent experiments.

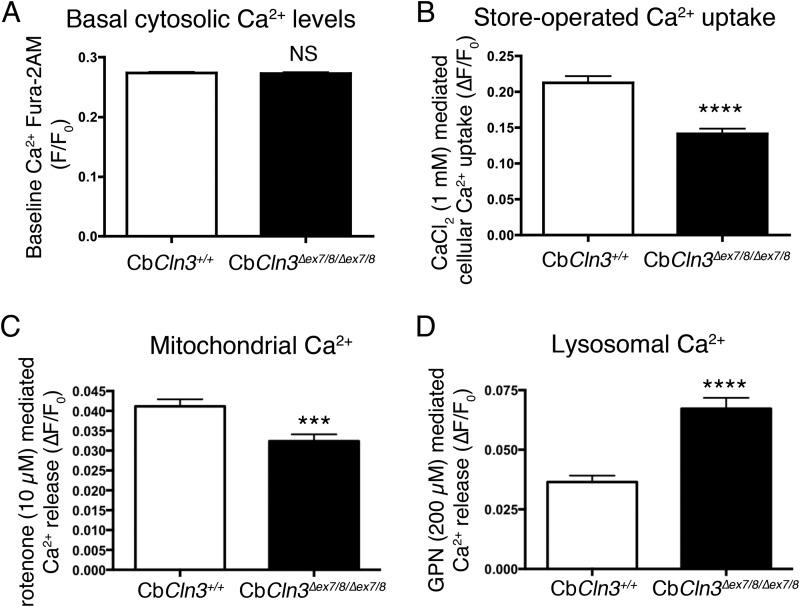

Given the observed differences in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cellular response to Ca2+ perturbation, we extended our measurements to analyze store-operated Ca2+ uptake and the mitochondrial and lysosomal Ca2+ pools, because Ca2+ from these latter sources is known to be important in vesicular fusion and in mediating the autophagy pathway (46, 47), and they also act as Ca2+ sinks in response to elevated cytosolic Ca2+ (25, 48). First, it was noteworthy that basal cytosolic Fura-2AM Ca2+ measurements were not different between the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 and CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 9A), indicating the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells could adequately buffer changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels. This might be achieved by pumping Ca2+ out of the cell, storing Ca2+ in other compartments such as lysosomes, or by altering store-operated Ca2+ entry. To determine whether the observed difference in cytosolic Ca2+ in response to subinhibitory doses of thapsigargin was caused by alterations in store-operated Ca2+ entry, we re-introduced 1 mm CaCl2 to the low Ca2+ extracellular recording buffer. Although both the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 and CbCln3+/+ cells responded, the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells had a significantly lower Ca2+ influx response (25% less), suggesting that the machinery of store-operated Ca2+ entry is also perturbed in these cells (Fig. 9B). To assess mitochondrial Ca2+, we measured Ca2+ release upon mitochondrial depolarization with rotenone. Although there was not a significant difference in the percentage of cells responding to rotenone (data not shown), the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells released ∼45% less Ca2+ following rotenone treatment, compared with CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 9C), suggesting the mitochondria in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells cannot properly maintain their Ca2+ levels, perhaps due to a reduced mitochondrial membrane potential. Mitochondrial membrane depolarization has been observed in CLN3 patient lymphoblasts (49). Finally, lysosomal Ca2+ was measured by first depleting and clamping the other intracellular stores with ionomycin (2 μm), then inducing lysosomal release by treatment with 200 μm glycyl-l-phenylalanine-β-naphthylamide (GPN) (25). In this instance, although all cells responded to the treatment, CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells released more Ca2+ compared with that observed for the CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 9D). Therefore, in addition to alterations in Ca2+ release following SERCA inhibition, CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells also harbor alterations in store-operated Ca2+ entry and in mitochondrial and lysosomal Ca2+ stores.

FIGURE 9.

Store-operated uptake, mitochondrial and lysosomal Ca2+ measurements in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. A, bar graph depicts mean baseline Ca2+ measurements in CbCln3+/+ (white bars) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (black bars) using Fura-2AM (F/F0). NS, not significant. n = 9 experiments, ≥150 cells analyzed. B, bar graph depicts Ca2+ uptake following 2 μm thapsigargin treatment to empty ER calcium stores in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells using Fura-2AM (ΔF/F0). C, bar graph depicts Ca2+ measurements in CbCln3+/+ (white bars) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (black bars) using Fura-2AM (ΔF/F0), in response to the mitochondrial uncoupling agent, rotenone (10 μm). ***, p < 0.001. D, bar graph depicts Ca2+ measurements in CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells using Fura-2AM (ΔF/F0), in response to 200 μm glycyl-l-phenylalanine-β-naphthylamide (GPN) after nonlysosomal stores had first been emptied with 2 μm ionomycin. ****, p < 0.0001. B–D, ≥50 cells were analyzed from three to four independent experiments. NS, not significant.

Discussion

Given the limited knowledge surrounding CLN3 function and the paucity of proven early-stage therapeutic targets for treatment of the fatal neurodegenerative disorder JNCL, we sought to establish a system for unbiased drug screening and target pathway discovery that accurately recapitulates disease genetics and represents a relevant cell type. Although the established autophagy-related phenotypes in CLN3 models and the relationship of these to neurodegeneration in JNCL are incompletely understood, we further reasoned that developing a screening assay around autophagy in an accurate genetic model would serve as a useful starting point because abnormalities in autophagy are detected early in the disease process (17). Furthermore, the CLN3 protein is documented to be present in autophagosomes and autolysosomes/lysosomes (17), and defects in this pathway are hypothesized to be important in the development of mitochondrial ATPase subunit c-containing lysosomal storage material, a pathological hallmark in JNCL and other forms of NCL (17, 42, 50). Here, we have successfully developed a GFP-LC3-based autophagy assay in our murine cerebellar neuronal progenitor cell model of JNCL, and importantly, we have demonstrated that chemical biology studies using this model can successfully identify compounds with conserved bioactivity in human JNCL patient-derived disease relevant cell types. In this case, our initial small scale unbiased drug screen led to the discovery and validation that at the level of the autophagy pathway, JNCL cells are particularly sensitive to thapsigargin treatment highlighting the potential importance of altered Ca2+ handling in the disease process. Indeed, we have clearly demonstrated here that CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells display increased Ca2+ leak events that could lead to aberrant Ca2+ signaling and vesicular trafficking. Therefore, this work definitively establishes the need for expanded research surrounding the role of CLN3 in regulating intracellular Ca2+ handling and further exploration of Ca2+ modulation as a potential target for JNCL therapy development.

The mechanisms by which CLN3 mutation leads to sensitivity to thapsigargin may involve a primary loss-of-function in the maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ stores, or this may occur secondary to loss of regulation of the Ca2+ homeostatic machinery. Indeed, in other forms of NCL, Ca2+ and other ion homeostatic disturbances have also been increasingly recognized (51). In particular, Zn2+ homeostasis is a major focus of current research in other forms of NCL and NCL-Parkinsonism overlap disorders, caused by CLN6 mutation and ATP13A2 mutation, respectively (52–54). In CLN6 disease models, a major disturbance in intracellular Zn2+ regulation and Ca2+ regulation have been identified (55, 56). To date, there is no compelling evidence that CLN3 itself functions as an ion transporter, but this possibility cannot yet be ruled out. An alternative hypothesis is that CLN3 regulates ion transporters/channel activity via regulating their trafficking, turnover, and/or activity via interactions with accessory proteins and/or lipids. In support of this notion is the observation that overexpressed CLN3 interacts with an ion channel complex (57). Intriguingly, consistent with the notion that CLN3 may play an active role in directly regulating Ca2+-mediated events, CLN3 has also previously been shown to bind the Ca2+-sensing protein, calsenilin, in a Ca2+-sensitive manner, and absence of this interaction in CLN3 knockdown cells sensitized to Ca2+ mediated cell death (35). In addition to this link between CLN3 function and Ca2+, pharmacological studies in CLN3 siRNA knockdown SH-SY5Y cells have also implicated a potential involvement of Ca2+ in neuronal cell death due to CLN3 loss (36, 58). A delayed recovery of intracellular Ca2+ levels was also reported following inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels in depolarized primary cortical neurons isolated from Cln3 knock-out mice (59). Notably, we did not observe a significantly altered sensitivity to cell death of the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells to low dose thapsigargin treatment compared with wild type cells, perhaps due to the changes we observed in the other intracellular Ca2+ stores, which may serve to protect the cells from Ca2+-mediated excitotoxicity.

Chronic CLN3 loss-of-function has also been reported to alter lipid microdomain architecture, which may influence Ca2+ channel complex formation and activity, and it has been demonstrated that glycolipids, such as the gangliosides, can alter SERCA activity (9, 24, 44, 60, 61). Hence, future work delineating the role of CLN3 in regulating lipids may shed further light on the altered Ca2+ handling observed in CLN3-deficient cells.

Rab7 is known to be a key regulator of autophagosomal maturation, and thapsigargin appears to specifically disrupt a step upstream of Rab7 association with the autophagosome (32, 37). These facts, along with the evidence that endogenous CLN3 may be present in a Rab7-Rab7-interacting lysosomal protein complex (39) prompted us to assess Rab7 association with autophagosomes in our mouse cerebellar cell system as well. Intriguingly, although Rab7 and CLN3 both appear to be important in the maturation of autophagosomes, the effect on the pathway by CLN3 mutation is not elicited by preventing Rab7 localization to the autophagosome. Further work is needed to fully elucidate whether CLN3 functions in regulating autophagosomal maturation via a Rab7 pathway, and how it may do so. It is nevertheless notable that Uusi-Rauva et al. (39) suggested that loss of CLN3 function leads to an imbalance of GTP/GDP forms of Rab7, given their observation that EGFP-Rab7 recruitment to the late endosome was more rapid in JNCL patient fibroblasts with the common ∼1-kb mutation, compared with control fibroblasts. Our observation in this study that Rab7 association with autophagosomal compartments is somewhat increased in fixed CbCln3Δex7/8 cells, as compared with wild type CbCln3 cells, would seem to support their findings. Interestingly, the additional late endosomal/lysosomal markers, LAMP-1 and LAMP-2a, also showed an increased association with autophagosomal pathway-derived compartments, as compared with wild type cells, further supporting the notion that loss of CLN3 function does not prevent fusion between autophagosomes and late endosomes but that the further maturation of these structures into degradative autolysosomes does not proceed with the same efficiency as that observed in nonstressed wild type cells. Indeed, brief stimulation of autophagic pathway flux via starvation or mTOR inhibition reduced the accumulation of GFP-LC3-Rab7 and GFP-LC3-LAMP-1 co-labeled structures. However, longer term stimulation, which could only be tested via mTOR inhibition due to general toxicity effects of starvation, did not produce this same effect. Further analysis of the effects of chronic autophagy pathway stimulation will be needed to determine whether this is beneficial or harmful to the cell in the context of CLN3 loss-of-function mutations. Notably, a 48-h treatment with rapamycin was previously found to increase the relative amount of subunit c deposits in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (17).