Background: The link between poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) and nuclear-translocated glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in neurons under oxidative/nitrosative stress remains unknown.

Results: The N terminus of nuclear GAPDH binds with PARP-1, and this complex promotes PARP-1 overactivation both in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusion: Nuclear GAPDH is a key PARP-1 regulator.

Significance: GAPDH/PARP-1 signaling underlies oxidative/nitrosative stress-induced brain damage such as stroke.

Keywords: ischemia, nitric oxide, oxidative stress, signaling, stroke

Abstract

In addition to its role in DNA repair, nuclear poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) mediates brain damage when it is over-activated by oxidative/nitrosative stress. Nonetheless, it remains unclear how PARP-1 is activated in neuropathological contexts. Here we report that PARP-1 interacts with a pool of glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) that translocates into the nucleus under oxidative/nitrosative stress both in vitro and in vivo. A well conserved amino acid at the N terminus of GAPDH determines its protein binding with PARP-1. Wild-type (WT) but not mutant GAPDH, that lacks the ability to bind PARP-1, can promote PARP-1 activation. Importantly, disrupting this interaction significantly diminishes PARP-1 overactivation and protects against both brain damage and neurological deficits induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion in a rat stroke model. Together, these findings suggest that nuclear GAPDH is a key regulator of PARP-1 activity, and its signaling underlies the pathology of oxidative/nitrosative stress-induced brain damage including stroke.

Introduction

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1)2 is a nuclear protein that plays roles in DNA repair, transcription, cell cycle, proliferation, and cell death (1, 2). Upon activation, PARP-1 consumes β-NAD to form poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) on specific acceptor proteins including PARP-1 itself as the major target via automodification (3). PARP-1 overactivation is likely to underlie some neurological conditions; its involvement has been well characterized in brain damage due to stroke as a result of DNA strand breakage after exposure to oxidative/nitrosative stress (4, 5). Recent studies have elucidated novel mechanisms for PARP-1 activation in physiological conditions; the current body of knowledge suggests that PARP-1 activation is also regulated by alternative mechanisms (6–8). Thus, it is important to further explore the regulatory mechanisms of PARP-1 in both physiological and pathological conditions.

Glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is also multifunctional (9, 10) in the brain (11, 12). Upon exposure to oxidative/nitrosative stressors, the active site cysteine 152 residue is oxidized/S-nitrosylated, which triggers GAPDH to translocate to the nucleus together with Siah (seven in absentia homolog), an E3-ubiquitin ligase with a nuclear localization signal (NLS) (13). Additionally, binding of nuclear GAPDH to acetyltransferase p300/CBT (CREB-binding protein) leads to the acetylation of GAPDH at lysine 162, which mediates cellular dysfunction in a p53-dependent manner (14). In pathological contexts, this nuclear GAPDH cascade is initiated in stroke models (15). Thus, posttranscriptional modifications of GAPDH are likely to play a crucial role in brain damage (16).

Here we report a novel protein interaction between GAPDH and PARP-1 in the nucleus both in vitro and in vivo. Our data indicate that nuclear-translocated GAPDH is an important regulator of PARP-1 activation in the pathological context of a rat stroke model. We used an adeno-associated virus 2 vector (AAV2) to replace or augment endogenous GAPDH in the adult rat brain by introducing siRNA co-expressing either exogenous GAPDH or a mutant lacking the ability to bind PARP-1, and our findings demonstrate that protein binding ability is required for PARP-1 regulation in the setting of stroke.

Experimental Procedures

Constructs

For bacterial expression, GAPDH or PARP-1 cDNA was cloned into pBAD-HisA (Invitrogen), pGEX-5X-2, or pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare). For mammalian expression, the cDNA was cloned into pcDNA4-TO-Myc/HisA (Invitrogen). Deletion constructs or site-directed mutant constructs for GAPDH or PARP-1 were generated as described in our previous publications (13, 14, 17, 18).

Antibodies

Goat polyclonal anti-PARP-1 antibody (1:2500, R&D Systems), mouse monoclonal anti-PARP-1 antibody (1:1000, Enzo Life Sciences), mouse monoclonal anti-PAR antibody (1:500, Enzo Life Sciences), mouse monoclonal anti-myc antibody (1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (1:300, Millipore), goat polyclonal anti-GST antibody (1:5000, GE Healthcare), rabbit polyclonal anti-His antibody (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-H2B (1:5000, Upstate Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine (1:200, StressMarq Bioscience, Inc.), and rabbit polyclonal anti-dinitrophenyl antibody (SHIMA Laboratories) were used in the present study. Rabbit polyclonal anti-triosephosphate isomerase antibody (1:1000) was kindly provided by Drs. Yamaji and Harada (Osaka Prefecture University).

Cell Culture

The generation of stable SH-SY5Y cells for inducible expression of human GAPDH (hGAPDH) was previously described (17). SH-SY5Y cells were purchased from the ATCC.

LC-MS/MS

Proteins were separated by 5–20% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Gel pieces were digested in 1 mg/ml trypsin, 100 mm NH4HCO3 at 37 °C for 12 h. Tryptic peptides were analyzed using a NanoFrontier L liquid chromatograph mass spectrometer (Hitachi High-Technologies). Peptides were trapped on MONOLITH TRAP (Kyoto Monotech) and separated on a MonoCap for fast flow (GL Sciences). MS and MS/MS analysis with the NanoFrontier L included the following parameters: the electrospray ionization spray potential was 1100 V in positive-ion mode, curtain gas flow was 1.0 liter/min, atmospheric pressure temperature was 140 °C, and scan mass range was m/z 200–2000 in auto MS/MS scan mode.

Biochemistry

All of the biochemical techniques were carried out according to existing methods. Production and purification of His- and GST-tagged recombinant proteins were conducted according to published protocols (13, 14, 17, 18). Subcellular fractionation (isolation of nuclear extracts) and co-immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously (3, 13, 19). GAPDH glycolytic and PARP-1 catalytic activities were measured according to our published protocols (17, 20). The GST pulldown assay was performed as described previously (13, 14).

Structure Modeling

A ribbon diagram of the hGAPDH monomer was prepared using the atomic coordinates of hGAPDH (PDB code 1U8F) with a molecular graphics program, the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System Version 0.99 software (DeLano Scientific LLC). A ribbon diagram of the rGAPDH monomer was prepared using SWISS-MODEL with the crystal structure of hGAPDH as a template structure (21).

Animal Surgery

Experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines of the Animal Ethical Committee. Left middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in male Wister rats (220–300 g) was performed as described previously (20, 22). Rats were anesthetized with 1.0–1.5% isoflurane (MSD Animal Health) in 70% N2O and 30% O2 delivered through a facial mask. The rectal temperature was monitored using a rectal probe and maintained around 37 °C using a thermostatically controlled heating blanket and an overhead lamp (Fine Science Tools). Under an operating microscope, a 4-0 monofilament nylon suture (NESCO, Nichi-in Bio Sciences Ltd.) coated with low viscosity silicone (XantoprenTM, Heraeus Kulzer) was inserted into the left internal carotid artery through the left external carotid artery and advanced ∼18–18.5 mm intracranially from the common carotid artery bifurcation to occlude the origin of left middle cerebral artery. After 1-h ischemia, the rats were re-anesthetized, and reperfusion was performed by the withdrawal of the thread. Physiological characteristics were measured according to published protocols (20, 22); the rats were anesthetized with 1.0–1.5% isoflurane in 70% N2O and 30% O2 delivered through a facial mask. Rectal temperature was measured using a rectal probe (Fine Science Tools). The right femoral artery was cannulated with PE-50 tubing for continuous monitoring of mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate in the polygraph system (RM-6000, Nihon Kohden). The left common carotid artery was also cannulated to measure pH, pO2, and pCO2 in the 288 Blood Gas System (Ciba Corning Diagnostics). Cerebral blood flow was monitored by a laser-Doppler flow meter FLO-N1 (Omegawave) with a probe placed on the burr hole (2 mm) of thinned skull over the left lateral cortex 2–3 mm posterior to the bregma and 5 mm lateral to midline. PARP-1 activation and GAPDH nuclear translocation were assessed by immunofluorescent tissue staining with the anti-PAR and anti-GAPDH antibodies as described above. The percentages of PAR-positive cells (in >500 DAPI-positive cells) captured by confocal microscopy were determined. Three or four images in different striatal regions were counted in each experimental group.

Introduction of siRNA and AAV2-mediated Expression Constructs into Rat Brain

Recombinant AAV2 vectors expressing either human WT or G10A mutant GAPDH were constructed according to a previously published protocol (23). To prepare recombinant AAV2 vectors harboring either the human WT GAPDH or G10A-GAPDH, each cDNA was cloned into pAAV-MCS using the pAAV-MCS vector of the AAV Helper-Free System (Agilent Technologies). Briefly, hGAPDH cDNA (WT or G10A) was amplified using the pcDNA4-TO-Myc/HisA harboring WT or G10A as a template for the EcoRI-BamHI sites. The sequences of the primers were 5′-CCGGAATTCCGTTATGGGGAAGGTGAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGCGGATCCGTTTAAACTCAATGGTGATG-3′ (reverse). The cis plasmid (which contains the gene of interest with AAV inverted terminal repeats), trans plasmid (with the AAV rep and cap gene), and a helper plasmid (pFΔ6, which contains an essential region from the Ad genome) were then co-transfected into HEK293 cells at a ratio of 1:1:1 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The cells were harvested 72 h later. The AAV2 particles were purified with a VIRA TRAP AAV Purification Maxi kit (Omega Bio-Tek) through elution from an AAV affinity column, desalted by dialysis at 4 °C against PBS, concentrated, and kept at 4 °C. The titer was determined with the AAV2 Titration ELISA Kit (PROGEN), finally yielding 2 × 1014 viral particles/ml. Injections (3 μl/site) of viral particles (2 × 1014/ml) were made at the following: A) +1.5 mm posterior to bregma, −3.2 mm lateral to midline, +5.5 mm ventral to the skull surface; B) +1.0 mm, −3.4 mm, +5.5 mm; C) +0.5 mm, −3.8 mm, +4.3 mm at an injection rate of 1 μl/min according to published protocols (24, 25). Exogenous GAPDH expression in the striatum (an ischemic core region) and the cortex (an ischemic penumbra region) was confirmed 1 month after injection. siRNA to control, e.g. non-targeting siRNA, (5′-UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA-3′) or rat GAPDH (rGAPDH; 5′-UCUACAUGUUCCAGUAUGA-3′, Accell siRNA from Dharmacon) was intracerebroventricularly introduced according to a previously published method (26). The AAV2-injected rats were placed in a stereotaxic instrument (Narishige). A single 28-gauge stainless steel injection cannula (Eicom) was lowered into the left lateral ventricle (coordinates: −0.8 mm posterior to bregma, −1.5 mm lateral to midline, and −4.6 mm ventral to the skull surface). The rats then received an acute intracerebroventricular injection of Accell siRNA (5 μg/rat) in 5 μl of Accell siRNA delivery media (Thermo Scientific) at a rate of 0.5 μl/min using a microinfusion pump (type ESP-32, Eicom) and a 10-μl Hamilton microsyringe. After infusion was complete, the cannula was left in place for 5 min and then removed at a rate of 1 mm/min.

Immunohistochemical Staining in Rat Brain

Frozen coronal sections (10–15 μm) were incubated with 10% goat serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature to block nonspecific binding. For assessment of production of nitrosative stress in MCAO brains, the sections were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with mouse monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine (1:200, StressMarq Biosciences Inc.). After three PBS washes, the sections were treated with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Histofine Simplestain MAX PO, Nichirei) for 1 h at room temperature. The signal was visualized using a 3,3-diaminobenzidine substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). For identification of cells expressing exogenous GAPDHs derived from AAV2 particle infection, frozen coronal sections through the rat striatal and cortical region (+1 to −1.16 mm) to the bregma were incubated at 4 °C overnight with mouse monoclonal anti-myc antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit polyclonal anti-MAP2 antibody (1:500, Millipore) or rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) (1:500, Dako). After 3 washes, the sections were incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen) and Alexa 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen) for 1 h. For nuclear staining, the cells were labeled with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 10 min. Square images (5 × 5 mm) were captured by confocal microscopy (C1si-TE2000-E; Nikon).

Determination of Infarct Volumes

Infarct volumes were measured after 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining according to a published protocol (20).

Neurological Tests

Global neurological deficits (normal score = 0, maximum score = 4) were assessed according to a published protocol (22). Paw tests (normal score = 0, maximum score = 10) included three examinations (fore and hind limb placing reflexes, tail suspension test, and fore and hind limb tests) according to published protocols (27, 28). Neurological deficits were evaluated by an observer blinded to the treatments. First, global neurological deficits were evaluated on a scale of 0–4 using the following criteria: 0 = rat appeared normal, 1 = failure to fully extend the contralateral forepaw, 2 = circling to the contralateral side, 3 = falling the contralateral side, 4 = no spontaneous movement and depressed consciousness. Second, paw tests were evaluated on a scale of 0–10 during three tests. In examination 1 (fore- and hind limb placing reflexes for 10 s) the scale was as follows: 0 = rats reveal normal paw placing reflex, 1 = mild reflex deficit (<5 s), and 2 = severe reflex deficit (<5 s). Examination 2 was a 10-s tail suspension test using the following scale: 0 = contralateral forelimb touch to floor, 1 = some touch, and 2 = no touch. Examination 3 was a fore- and hind limb grip test using the following scale: 0 = rats can pull the paw strongly, 1 = mild paw-pull, 2 = no paw-pull.

Docking Simulation of GAPDH-PARP-1 Interaction

A structural model of the N terminus of hGAPDH (PDB code 1U8F) and the catalytic domain of hPARP-1 (PDB code 2RCW) complex was generated using the data-driven docking program HADDOCK 2.1 (29) governed by ambiguous intermolecular restraints obtained from mutagenesis data.

Statistical Analysis

All data are the mean ± S.E. of independent experiments as indicated the numbers (n) in each figure legend. For statistical analysis, two groups and multiple groups were compared with unpaired Student's t tests or Dunnett's multiple tests after one-way analysis of variance, respectively.

Results and Discussion

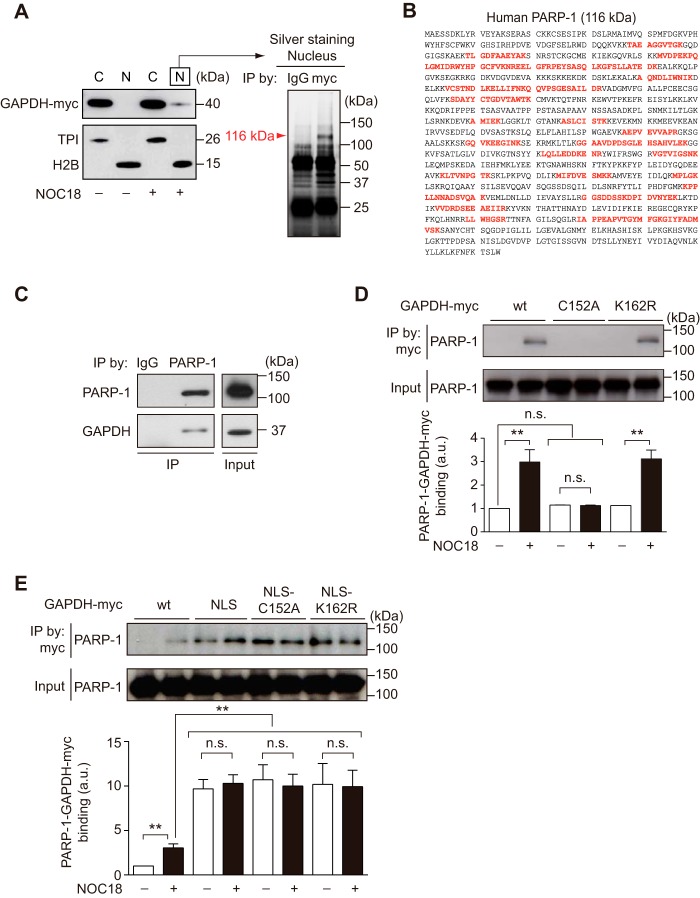

We initially investigated nuclear proteins that exhibited enhanced or specific binding with GAPDH when exposed to the nitric oxide generator NOC18 (also termed DETA NONOate) in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing exogenous myc-tagged GAPDH (Fig. 1A, left). We analyzed the immunoprecipitates of the nuclear fraction with an anti-myc antibody and observed that ∼116-kDa protein(s) preferentially precipitated with myc-GAPDH (Fig. 1A, right). We then performed MS and identified 20 peptides whose sequences perfectly matched those of PARP-1 (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that PARP-1 and GAPDH may interact in the nuclei of cells exposed to oxidative/nitrosative stressors. We further confirmed the endogenous protein interaction of PARP-1 and GAPDH in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Nuclear GAPDH interacts with PARP-1 in SH-SY5Y cells. A, treatment of SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing exogenous myc-tagged GAPDH with vehicle (−) or NOC18 (+). NOC18 stimulated GAPDH nuclear translocation. C, cytoplasm; N, nucleus. Triosephosphate isomerase (TPI) and H2B are cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, respectively. Nuclear GAPDH preferentially binds with a protein(s) that is ∼116 kDa in NOC18-treated SH-SY5Y cells. The arrowhead indicates a specific protein at 116 kDa that is immunoprecipitated (IP) with myc-tagged hGAPDH. B, hPARP-1 amino acids (GenBankTM accession number AAB59447); peptide sequences identified with MS are indicated in red. C, endogenous GAPDH and PARP-1 bind in the nuclei of NOC18-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Input indicates the IP starting material. D, GAPDH-PARP-1 binding in SH-SY5Y cells stably harboring three distinct myc-tagged GAPDH (WT, C152A, and K162R mutants) in the presence or absence of NOC18. Vehicle (−) or NOC18 (+) exposure augmented the protein binding of WT GAPDH-myc with PARP-1. Replacement of Cys-152 did not show the interaction, whereas substitution of Lys-162 to arginine showed the interaction same degree as that of WT. Input is the immunoprecipitation starting material. **, p < 0.01. n.s., not significant. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3). E, GAPDH-PARP-1 binding in SH-SY5Y cells stably harboring four distinct myc-tagged GAPDH (WT, NLS conjugated, C152A mutant with NLS, and K162R with NLS) in the presence or absence of NOC18. Ectopic NLS attachment dramatically enhanced the binding, and further exposure to NOS18 did not lead to an additional change. Replacement of Cys-152 or Lys-162 did not affect the interaction in the presence of NLS. Input is the immunoprecipitation starting material. **, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3).

We next tested the roles for oxidative/nitrosative stress, nuclear localization, and two major posttranslational modifications of GAPDH: Cys-152 required for GAPDH nuclear translocation in response to oxidative/nitrosative stress (13) and Lys-162 essential for its interaction with p300/CBP (14). Therefore, we used SH-SY5Y cells stably and ectopically expressing myc-tagged GAPDH with six different characteristics (Fig. 1, D and E). Although the exposure to NOC18 significantly elicited its interaction of WT- and K162R-GAPDH-myc with PARP-1, replacement of Cys-152 did not even under NOC18-exposure (Fig. 1D). Then, the addition of a NLS to GAPDH was sufficient to augment its interaction with PARP-1, and further exposure to NOC18 did not lead to an additional change (Fig. 1E). Replacement of Cys-152 or Lys-162 did not affect the interaction in the presence of the NLS (Fig. 1E), indicating that the interaction is critical only for the existence of GAPDH in the nucleus. Thus, oxidative/nitrosative stressors are likely to facilitate the GAPDH-PARP-1 interaction by inducing the nuclear translocation of GAPDH.

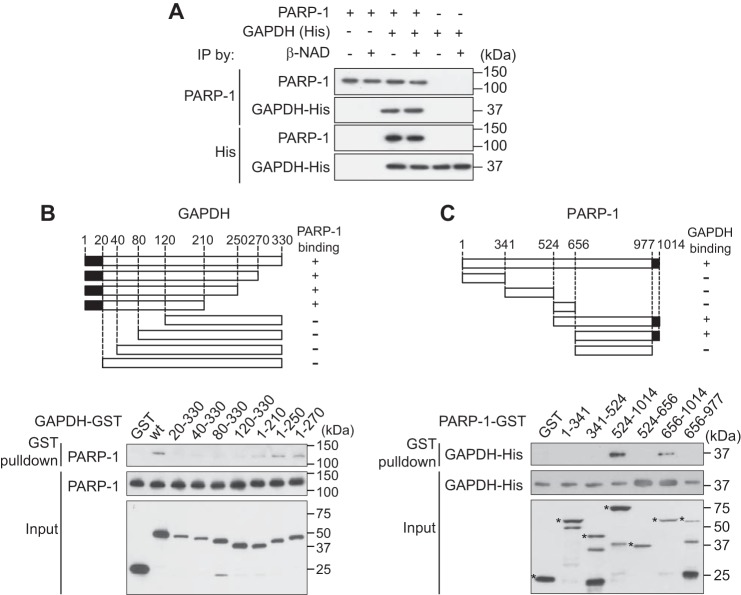

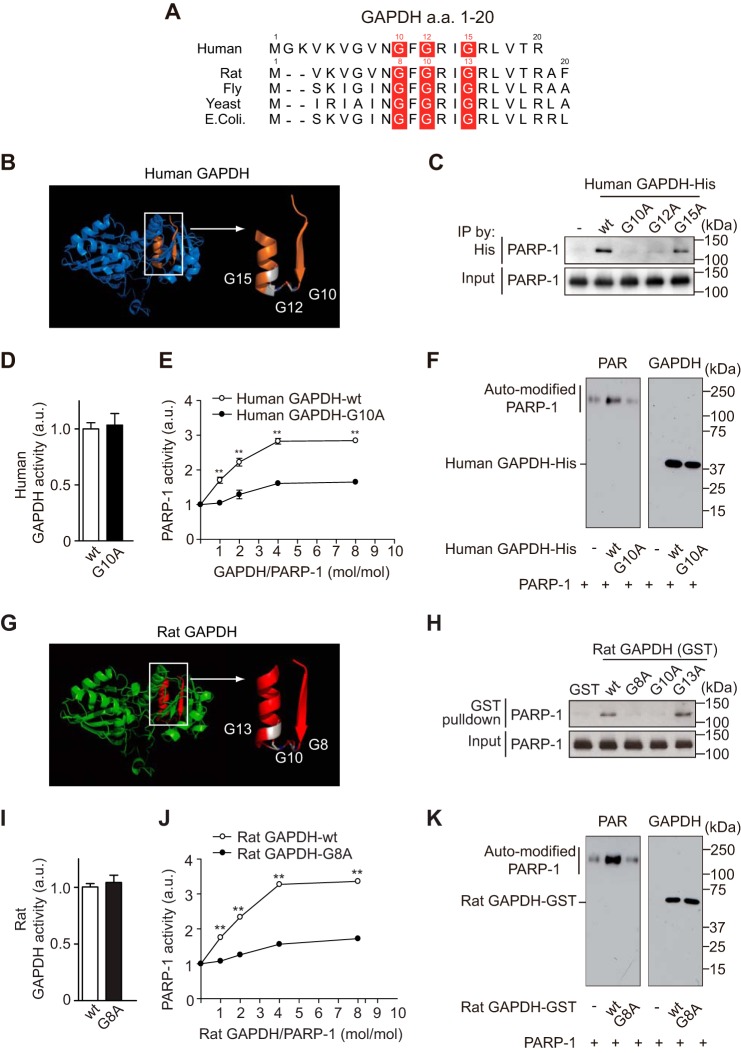

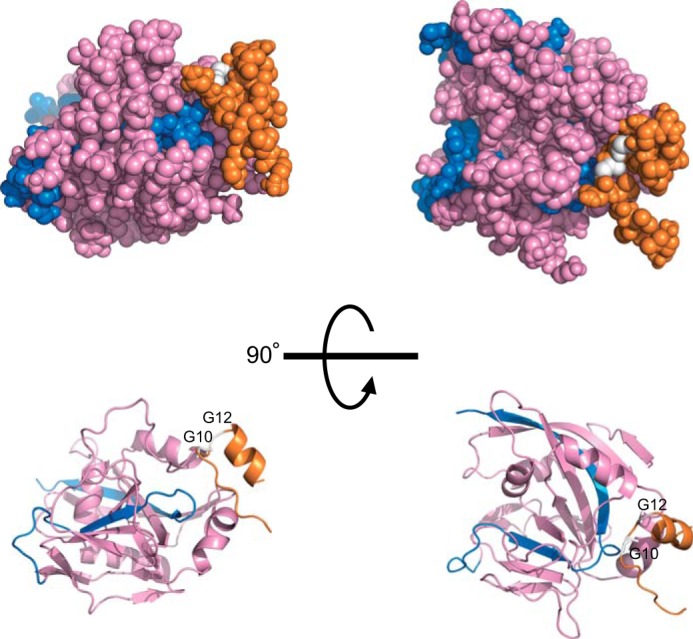

By utilizing recombinant proteins in vitro, we further characterized direct binding between PARP-1 and GAPDH and observed no influence of β-NAD (a substrate for both proteins) (Fig. 2A). Mutagenesis of GAPDH and PARP-1 was performed to define the critical domains required for the interaction (the 20 N terminus amino acids of GAPDH (Fig. 2B) and the short C terminus of PARP-1 (Fig. 2C)). The N terminus of GAPDH contains the Rossmann glycine motif (GXGXXG) (30), which is highly conserved among species (Fig. 3A). Among three glycine residues (Fig. 3B), human Gly-10 and Gly-12 were determined to be crucial for the binding, as replacement of either amino acid with alanine abolished binding between GAPDH and PAPR-1 (Fig. 3C). Replacement of Gly-10 did not affect GAPDH glycolytic activity (Fig. 3D). Importantly, we observed that GAPDH activated PARP-1; this activation is likely to depend on their interactions, as WT, but not Gly-10 mutant, GAPDH activated PARP-1 (Fig. 3E). Although PARP-1 poly-ADP ribosylates many proteins including mainly PARP-1 itself (3), GAPDH is not a PARP-1 substrate (Fig. 3F). The interaction and functional influence of GAPDH was observed for both the human and rat proteins (Fig. 3, G and H).

FIGURE 2.

Direct binding of the GAPDH-PARP-1 and mapping of the crucial domains for the interaction in vitro. A, β-NAD did not affect the direct interaction between His-tagged human GAPDH and human PARP1. IP, immunoprecipitation. B, schematic representation of the GAPDH binding domain for PARP-1. Recombinant and purified proteins from various GST-tagged human GAPDH deletion constructs were tested for in vitro binding with human PARP-1 using a GST pulldown method. Amino acids 1–20 of GAPDH are responsible for binding to PARP-1. C, schematic representation of the PARP-1 binding domain for GAPDH. Recombinant and purified proteins from various GST-tagged human PARP-1 deletion constructs were tested for in vitro binding with His-tagged human GADPH (recombinant and purified protein) by GST pulldown. Asterisks indicate each recombinant PARP-1 mutant. Amino acids 977–1014 of PARP-1 are responsible for binding GAPDH.

FIGURE 3.

GAPDH promotes PARP-1 activation via direct binding in vitro. A, conservation of the Rossmann glycine motif of GAPDH among species. These reference sequences are GenBankTM accessions NP_001276675 (human), NP_058704 (rat), P00360 (yeast), AAF48531 (fly), and EFW64777 (Escherichia coli), respectively. a.a., amino acids. B, structural model of the Rossmann glycine motif (orange) of human GAPDH (PDB code 1U8F). C, WT and mutant G15A GAPDH bind to human PARP-1, whereas mutants G10A and G12A do not. Input is the immunoprecipitation (IP) starting material. D, mutation of G10A in human GAPDH does not affect glycolytic activity. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 4). a.u., arbitrary units. E, WT GAPDH activates human PARP-1, but the G10A mutant does not. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 4). F, Western blot of PAR (left) and human His-tagged GAPDH (right) after in vitro PARP-1 activation assays in E with a 1:1 molar ratio of GAPDH and PARP-1. Human GAPDH is not polyADP-ribosylated by human PARP-1. G, structural model of the Rossmann glycine motif (red) of rat GAPDH. H, GST-tagged WT and mutant G13A rat GAPDH bind to human PARP-1 in vitro, whereas G8A and G10A mutants do not. I, a G8A mutation in GST-tagged rat GAPDH did not affect glycolytic activity. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 4). J, GST-tagged WT rat GAPDH promotes human PARP-1 activation in vitro, but the G8A mutant does not. **, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 4). K, Western blots of PAR (left) and GST-tagged rat GAPDH (right) in the in vitro human PARP-1 activation assay in J with a 1:1 molar ratio of GAPDH to PARP-1.

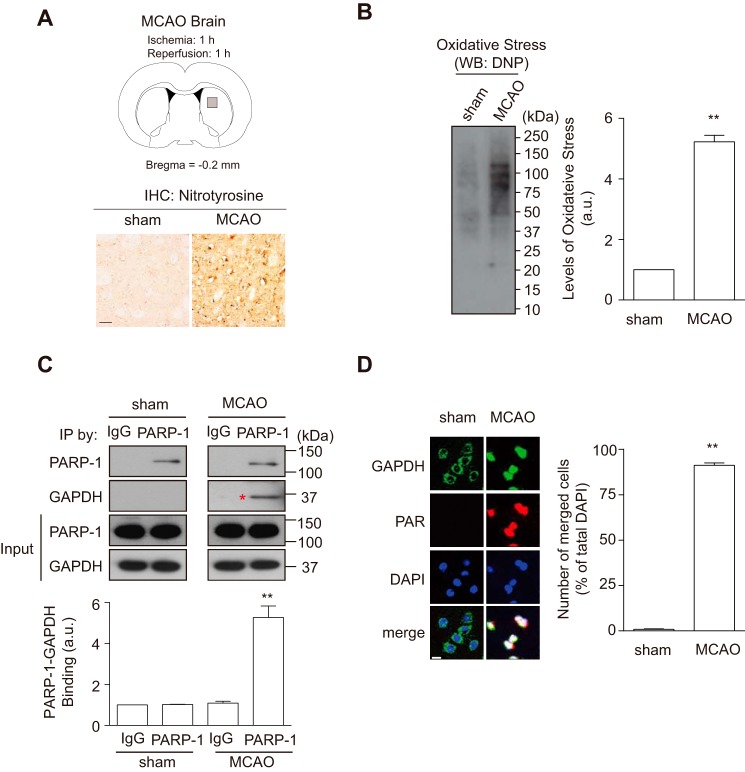

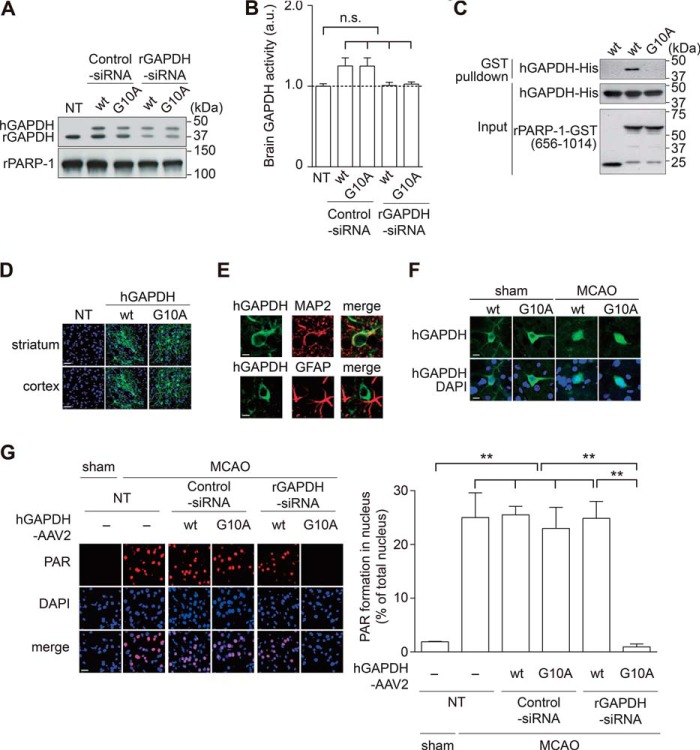

Oxidative/nitrosative stress-induced PARP-1 activation and its pivotal role in brain damage have been established in an MCAO stroke model (4, 27). Furthermore, the nuclear translocation of GAPDH has also been reported in the MCAO model (15). To examine whether GAPDH-PARP-1 interaction and nuclear GAPDH-induced PARP-1 activation occurred in vivo, we conducted the MCAO rat stroke model. We first confirmed production of both nitosative stress (Fig. 4A) and oxidative stress (Fig. 4B) in the striatum (ischemic core) of MCAO brain at 1 h after reperfusion. At this time point, we tested whether the interaction between GAPDH and PARP-1 occurred in this stroke model. Protein extracts from MCAO, but not sham rats, revealed an endogenous interaction significantly (Fig. 4C). Histological examination revealed that GAPDH had translocated to the nucleus and activated PARP-1, as indicated by augmented PAR levels in the MCAO brain (Fig. 4D). To determine whether the GAPDH-PARP-1 interaction is indeed crucial for PARP-1 activation in vivo, we replaced endogenous rGAPDH by introducing a corresponding siRNA and co-expressing exogenous hGAPDH via an AAV2 (Fig. 5A). Under this experimental condition, we did not observe any change in cerebral blood flow or major physiological characteristics (Fig. 5, B and C). We confirmed successful knockdown of endogenous rGAPDH and did not observe degradation of exogenous hGAPDH following the application of rGAPDH siRNA (Fig. 6A). These GAPDH activities were maintained in each genetically modified brain (Fig. 6B). We also validated that human WT, but not Gly-10 mutant, GAPDH interacted with rat PARP-1 in vitro (Fig. 6C). Exogenous hGAPDH was expressed in the neurons of both the rat striatum and cortex in vivo (Fig. 6, D and E). Both exogenous WT and Gly-10 mutant hGAPDH were found in the nucleus 1 h after reperfusion (Fig. 6F). Under these experimental conditions, we examined PARP-1 activation in the striatum of MCAO rats and investigated the impact of the GAPDH-PARP-1 interaction. As reported (4), robust PARP-1 activation was observed in the MCAO model (Fig. 6G). Interestingly, replacement of exogenous rGAPDH with the Gly-10 hGAPDH mutant lacking the ability to bind PARP-1 abolished the activation (Fig. 6G). The GAPDH-PARP-1 interaction is likely to play a pivotal role in this process, as replacement of endogenous rGAPDH with exogenous WT hGAPDH failed to abolish PARP-1 activation.

FIGURE 4.

Oxidative/nitrosative stress induced nuclear-translocated GAPDH interacts with PARP-1 in a rat stroke model. A, assessment of nitrosative stress in MCAO brain. Schematic depicting the ischemic core site (striatum) of interest in analyses (gray square, upper panel). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) using an anti-nitrotyrosine antibody in striatum of sham- or MCAO-operated rats (lower panels). Scale bar = 50 μm. B, assessment of oxidative stress in MCAO brain. Protein carbonyls in the striatum, a hallmark for oxidative stress, were detected by Western blotting (WB) using an anti-dinitrophenyl (DNP) antibody (left panel). The levels of oxidative stress increased to ∼5-fold by MCAO treatment (right panel). **, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3). C, rat GAPDH and rat PARP-1 bind in the brain of MCAO but not sham-operated rats. Input is the starting immunoprecipitation (IP) material. **, p < 0.01. a.u., arbitrary units. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3). D, rat GAPDH (green) translocates to the nucleus (blue, DAPI) in neurons of MCAO rats, in which rat PARP-1 is activated as indicated by the level of PAR (red). The numbers of both PAR and nuclear GAPDH-positive cells merged with DAPI prominently increased in MCAO rats (roughly 85% of total DAPI-positive cells; right panel). The analyzed area is indicated at the regions of the gray square in A. Scale bar = 15 μm. **, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 4).

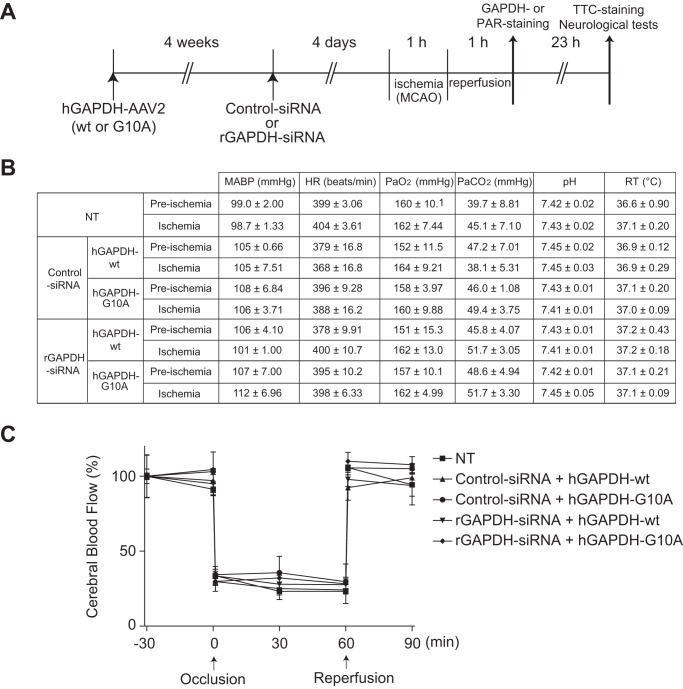

FIGURE 5.

Experimental design and physiological parameters. A, MCAO/reperfusion combined with replacement of endogenous rGAPDH with human WT or mutant G10A hGAPDH in vivo. TTC, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride. B, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), heart rate (HR), blood parameters (pH, PaO2, and PaCO2), and rectal temperature (RT) 30 min before occlusion (pre-ischemia) or just before reperfusion (ischemia). Data from each group are represented as the mean ± S.E. from three animals. NT, no treatment. C, change in the cerebral blood flow. Levels 30 min before occlusion per group are defined as 100%. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3).

FIGURE 6.

Nuclear-translocated GAPDH promotes MCAO/reperfusion-induced PARP-1 overactivation in a rat stroke model. A, successful knockdown of endogenous rGAPDH without degradation of exogenous WT or mutant G10A hGAPDH by siRNA to rGAPDH. NT, no treatment. pPARP-1, rat PARP-1. B, no influence of GAPDH glycolytic activities in tissue lysates extracted from each brain. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 5). n.s., not significant. C, GST pulldown revealing an interaction between GST-tagged rat PARP-1 fragment (amino acids 656–1014) and human WT GAPDH but not the Gly-10 mutant in vitro. D and E, preferential ectopic expression of human myc-tagged GAPDH in neurons of the rat striatum and cortex was confirmed by immunofluorescent tissue staining with an anti-myc antibody. Green, human GAPDH; blue, DAPI (nuclei). The neuronal marker MAP2 and the glial marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) are shown in red. Scale bar, left panel, 50 μm; right panel, 5 μm. F, nuclear translocation of ectopically introduced WT or mutant G10A hGAPDH in neurons of MCAO but not sham-operated rats. Green, hGAPDH; blue, DAPI (nucleus). Scale bar = 15 μm. G, PARP-1 activation in the MCAO brain is blocked by complementing endogenous GADPH with mutant G10A GAPDH that cannot interact with PARP-1, whereas replacement with WT GAPDH has no beneficial effect. PARP-1 activation was assessed by measuring PAR levels (in red). Scale bar = 40 μm. **, p < 0.01, Dunnett's multiple test after one-way analysis of variance. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 3–4).

To further address whether the PARP-1-GAPDH interaction mediates MCAO/reperfusion-induced brain damage in a rat stroke model, we measured infarct volumes and neurological functions under the same conditions. At 23 h after reperfusion, intense infarctions were observed in MCAO model rats (Fig. 7A), but replacement with Gly-10 mutant hGAPDH significantly reduced MCAO/reperfusion-induced infarct volumes. No significant reduction of infarct volume was observed for exogenous WT hGAPDH (Fig. 7A). Notably, the neurological test results were better in rats with smaller infarct volumes (Fig. 7B). Thus, our findings indicate that nuclear GAPDH is likely to contribute MCAO/reperfusion-induced brain damage via regulation of PARP-1 activity in a rat stroke model.

FIGURE 7.

Nuclear-translocated GAPDH is involved in MCAO/reperfusion-induced both brain damage and neurological deficits in a rat stroke model. A, infarct volume in the MCAO brain is reduced by complementing endogenous GADPH with mutant G10A GAPDH that cannot interact with PARP-1, whereas replacement with WT GAPDH has no beneficial effect. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; Dunnett's multiple test after one-way analysis of variance. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 6). NT, no treatment. B, neurological tests in the MCAO rats are consistent with the infarct volume results (A). The left panel shows the global neurological deficits evaluated from 0–4. The right panel shows the results of the paw tests evaluated from 0–10. **, p < 0.01, Dunnett's multiple test after one-way analysis of variance. Error bars represent S.E. (n = 6).

In the present study we demonstrated that nuclear-translocated GAPDH mediates PARP-1 activation in the setting of oxidative/nitrosative stress in a rat stroke model. Our data from mutant GAPDH lacking the ability to bind PARP-1 indicate that this interaction is necessary to promote PARP-1 activity. These results suggest that PARP-1 overactivation requires both DNA strand breakage and binding to nuclear GAPDH. A recent review postulated that PARP-1 binding to DNA strand breaks is not the only mechanism for PARP-1 activation; protein-protein interactions are also considered to be involved (8).

GAPDH-induced PARP-1 activation is thought to depend on the interaction between the two proteins. Langelier et al. (31) proposed a PARP-1 activation model in which conformational distortions of the C terminus catalytic domain of PARP-1 (amino acids 656–1014) leads to PAR formation regardless of its DNA binding ability. Our data indicate that GAPDH specifically binds to the short C terminus of PARP-1 (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, a docking model of GAPDH-PARP-1 confirmed that their interaction is possible (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Simulation of the GAPDH-PARP-1 interaction. Shown is a proposed model of the N terminus of human GAPDH and the catalytic domain of human PARP complex obtained by HADDOCK Version 2.1. The N terminus of GAPDH is orange, the catalytic domain of PARP is pink (including the short C terminus, blue), and both Gly-10 and Gly-12 are white.

Our results also demonstrate that the interaction between GAPDH and PARP-1 is involved in brain damage. When massive oxidative/nitrosative stress occurs after a stroke, nuclear-translocated GAPDH may play a crucial role in the PARP-1-dependent cell death cascade (32, 33). Thus, the findings in this study reveal a possible method for combating brain damage caused by the PARP-1-dependent cell death cascade that takes place in stroke and other ischemia-reperfusion injury-related diseases.

Acknowledgment

We thank Yukiko L. Lema for preparing the figures and organizing the manuscript.

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grants 15605666 (to T. T.), 22580339 and 25450428 (to H. N.), and 23120011 and 23680034 (to T. H.).

- PARP-1

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1

- AAV2

- adeno-associated virus serotype 2

- hGAPDH

- human GAPDH

- rGAPDH

- rat GAPDH

- MCAO

- middle cerebral artery occlusion

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- NOC18 (DETA NONOate)

- 1-hydroxy-2-oxo-3,3-bis(2-aminoethyl)-1-triazene

- PAR

- poly(ADP-ribose).

References

- 1. D'Amours D., Desnoyers S., D'Silva I., Poirier G. G. (1999) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem. J. 342, 249–268 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schreiber V., Dantzer F., Ame J. C., de Murcia G. (2006) Poly(ADP-ribose): novel functions for an old molecule. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ogata N., Ueda K., Kawaichi M., Hayaishi O. (1981) Poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase, a main acceptor of poly(ADP-ribose) in isolated nuclei. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 4135–4137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eliasson M. J., Sampei K., Mandir A. S., Hurn P. D., Traystman R. J., Bao J., Pieper A., Wang Z. Q., Dawson T. M., Snyder S. H., Dawson V. L. (1997) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase gene disruption renders mice resistant to cerebral ischemia. Nat. Med. 3, 1089–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ha H. C., Snyder S. H. (2000) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in the nervous system. Neurobiol. Dis. 7, 225–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abd Elmageed Z. Y., Naura A. S., Errami Y., Zerfaoui M. (2012) The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs): new roles in intracellular transport. Cell. Signal. 24, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bürkle A., Virág L. (2013) Poly(ADP-ribose): PARadigms and PARadoxes. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 1046–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Virág L., Robaszkiewicz A., Rodriguez-Vargas J. M., Oliver F. J. (2013) Poly(ADP-ribose) signaling in cell death. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 1153–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sirover M. A. (2012) Subcellular dynamics of multifunctional protein regulation: mechanisms of GAPDH intracellular translocation. J. Cell. Biochem. 113, 2193–2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tristan C., Shahani N., Sedlak T. W., Sawa A. (2011) The diverse functions of GAPDH: views from different subcellular compartments. Cell. Signal. 23, 317–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Butterfield D. A., Hardas S. S., Lange M. L. (2010) Oxidatively modified glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and Alzheimer's disease: many pathways to neurodegeneration. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 20, 369–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tatton W. G., Chalmers-Redman R. M., Elstner M., Leesch W., Jagodzinski F. B., Stupak D. P., Sugrue M. M., Tatton N. A. (2000) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in neurodegeneration and apoptosis signaling. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 60, 77–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hara M. R., Agrawal N., Kim S. F., Cascio M. B., Fujimuro M., Ozeki Y., Takahashi M., Cheah J. H., Tankou S. K., Hester L. D., Ferris C. D., Hayward S. D., Snyder S. H., Sawa A. (2005) S-Nitrosylated GAPDH initiates apoptotic cell death by nuclear translocation following Siah1 binding. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 665–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sen N., Hara M. R., Kornberg M. D., Cascio M. B., Bae B. I., Shahani N., Thomas B., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L., Snyder S. H., Sawa A. (2008) Nitric oxide-induced nuclear GAPDH activates p300/CBP and mediates apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 866–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanaka R., Mochizuki H., Suzuki A., Katsube N., Ishitani R., Mizuno Y., Urabe T. (2002) Induction of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression in rat brain after focal ischemia/reperfusion. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 22, 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakamura T., Lipton S. A. (2013) Emerging role of protein-protein transnitrosylation in cell signaling pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 239–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakajima H., Amano W., Kubo T., Fukuhara A., Ihara H., Azuma Y. T., Tajima H., Inui T., Sawa A., Takeuchi T. (2009) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase aggregate formation participates in oxidative stress-induced cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34331–34341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakajima H., Amano W., Fujita A., Fukuhara A., Azuma Y. T., Hata F., Inui T., Takeuchi T. (2007) The active site cysteine of the proapoptotic protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is essential in oxidative stress-induced aggregation and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26562–26574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sawa A., Khan A. A., Hester L. D., Snyder S. H. (1997) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: nuclear translocation participates in neuronal and nonneuronal cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11669–11674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakajima H., Kakui N., Ohkuma K., Ishikawa M., Hasegawa T. (2005) A newly synthesized poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, DR2313 [2-methyl-3,5,7,8-tetrahydrothiopyrano[4,3-d]-pyrimidine-4-one]: pharmacological profiles, neuroprotective effects, and therapeutic time window in cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 312, 472–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N., Peitsch M. C. (2003) SWISS-MODEL: An automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3381–3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Longa E. Z., Weinstein P. R., Carlson S., Cummins R. (1989) Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 20, 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hikida T., Kimura K., Wada N., Funabiki K., Nakanishi S. (2010) Distinct roles of synaptic transmission in direct and indirect striatal pathways to reward and aversive behavior. Neuron 66, 896–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun Y., Jin K., Clark K. R., Peel A., Mao X. O., Chang Q., Simon R. P., Greenberg D. A. (2003) Adeno-associated virus-mediated delivery of BCL-w gene improves outcome after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Gene Ther. 10, 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang L., Muramatsu S., Lu Y., Ikeguchi K., Fujimoto K., Okada T., Mizukami H., Hanazono Y., Kume A., Urano F., Ichinose H., Nagatsu T., Nakano I., Ozawa K. (2002) Delayed delivery of AAV-GDNF prevents nigral neurodegeneration and promotes functional recovery in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Gene Ther. 9, 381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakajima H., Kubo T., Semi Y., Itakura M., Kuwamura M., Izawa T., Azuma Y. T., Takeuchi T. (2012) A rapid, targeted, neuron-selective, in vivo knockdown following a single intracerebroventricular injection of a novel chemically modified siRNA in the adult rat brain. J. Biotechnol. 157, 326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Belayev L., Alonso O. F., Busto R., Zhao W., Ginsberg M. D. (1996) Middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat by intraluminal suture: neurological and pathological evaluation of an improved model. Stroke 27, 1616–1622; discussion 1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garcia J. H., Wagner S., Liu K. F., Hu X. J. (1995) Neurological deficit and extent of neuronal necrosis attributable to middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats: statistical validation. Stroke 26, 627–634; discussion 635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dominguez C., Boelens R., Bonvin A. M. (2003) HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1731–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kleiger G., Eisenberg D. (2002) GXXXG and GXXXA motifs stabilize FAD and NAD(P)-binding Rossmann folds through Cα-H···O hydrogen bonds and van der waals interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 323, 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Langelier M. F., Planck J. L., Roy S., Pascal J. M. (2012) Structural basis for DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by human PARP-1. Science 336, 728–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andrabi S. A., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L. (2008) Mitochondrial and nuclear cross talk in cell death: parthanatos. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1147, 233–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vanden Berghe T., Linkermann A., Jouan-Lanhouet S., Walczak H., Vandenabeele P. (2014) Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 135–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]