Background: TANK has been shown to promote deubiquitination of TRAFs, but the mechanism involved is unclear.

Results: TANK associates with MCPIP1 and USP10, thereby diminishing TRAF6 ubiquitination, which inhibits NF-κB activation by genotoxic stress and IL-1R/TLR activation.

Conclusion: The deubiquitinating activity of TANK is achieved by its association with USP10.

Significance: Modulating TANK may enhance cancer cell sensitivity to chemotherapy.

Keywords: DNA damage, NF-κB, TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF), ubiquitin-dependent protease, ubiquitylation (ubiquitination), TANK

Abstract

DNA damage-induced NF-κB activation plays a critical role in regulating cellular response to genotoxic stress. However, the molecular mechanisms controlling the magnitude and duration of this genotoxic NF-κB signaling cascade are poorly understood. We recently demonstrated that genotoxic NF-κB activation is regulated by reversible ubiquitination of several essential mediators involved in this signaling pathway. Here we show that TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator (TANK) negatively regulates NF-κB activation by DNA damage via inhibiting ubiquitination of TRAF6. Despite the lack of a deubiquitination enzyme domain, TANK has been shown to negatively regulate the ubiquitination of TRAF proteins. We found TANK formed a complex with MCPIP1 (also known as ZC3H12A) and a deubiquitinase, USP10, which was essential for the USP10-dependent deubiquitination of TRAF6 and the resolution of genotoxic NF-κB activation upon DNA damage. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9-mediated deletion of TANK in human cells significantly enhanced NF-κB activation by genotoxic treatment, resulting in enhanced cell survival and increased inflammatory cytokine production. Furthermore, we found that the TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 complex also decreased TRAF6 ubiquitination in cells treated with IL-1β or LPS. In accordance, depletion of USP10 enhanced NF-κB activation induced by IL-1β or LPS. Collectively, our data demonstrate that TANK serves as an important negative regulator of NF-κB signaling cascades induced by genotoxic stress and IL-1R/Toll-like receptor stimulation in a manner dependent on MCPIP1/USP10-mediated TRAF6 deubiquitination.

Introduction

DNA-damaging agents such as genotoxic chemotherapeutics and ionizing radiation are widely used as the mainstay of cancer therapy to treat various types of human malignancies such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, and colon cancer. However, acquired therapeutic resistance to the genotoxic agents significantly limits the efficacy of cancer treatments, resulting in cancer relapse and metastasis. DNA damage-induced activation of transcription factor NF-κB plays a critical role in mediating therapeutic resistance in cancer cells (1, 2). Genotoxic treatment-activated NF-κB has been shown to modulate the transcription of antiapoptotic genes, proinflammatory cytokines, and oncogenic microRNAs, which collaboratively attenuate DNA damage-induced cancer cell apoptosis and promote cancer cell invasion (3–5). Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms controlling the activation and resolution of NF-κB activation by genotoxic anticancer agents may provide pivotal insights into developing novel therapeutic approaches to counteract acquired drug resistance and improve therapeutic efficacy.

The mechanisms involved in regulating NF-κB signaling cascades following activation of membrane-bound receptors have been well established (6, 7). Nevertheless, how genotoxic agents, which initiate a DNA damage response in the nucleus, activate the cytoplasmic NF-κB signaling cascade is still not completely understood (2, 8). It has been found that NF-κB essential modifier (NEMO,4 also known as IKKγ), the regulatory subunit of the canonical IκB kinase complex, was modified by SUMO-1 in the nucleus upon genotoxic stress (9), which was facilitated by PARP1, protein inhibitor of activated STAT (PIASy), and the PIDD (p53-induced protein with a death domain)/RIP1 (receptor-interacting protein 1) complex (10–12). Then SUMOylated NEMO could further interact with the DNA damage response apical kinase ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated), which directly phosphorylates and facilitates cIAP1/2-mediated monoubiquitination of NEMO (13, 14). The nuclear monoubiquitination of NEMO promotes the export of the NEMO-ATM complex into the cytoplasm, where it further activates the cytoplasmic IKK and downstream NF-κB signaling pathways. Moreover, Lys-63-linked polyubiquitination of ELKS, RIP1, and TRAF6 as well as the M1-linked linear ubiquitination of NEMO have been shown to modulate TAK1/IKK kinase complex activation in the cytoplasm upon genotoxic stimulation (15–18).

The extent and duration of NF-κB activation is controlled by a dynamic balance between activation signaling and negative regulatory mechanisms, leading to the resolution of NF-κB activation (19). Compared with signaling events mediating NF-κB activation upon DNA damage, even less was known about how this signaling cascade is resolved. Lee et al. (20) found that a Sentrin/SUMO-specific protease, SENP2, was up-regulated in response to genotoxic NF-κB activation, which served as a negative feedback response to inhibit NF-κB activation by attenuating NEMO SUMOylation in response to genotoxic stress. We showed recently that NF-κB-dependent MCPIP1 (also known as ZC3H12A) induction negatively regulated the genotoxic NF-κB signaling cascade by promoting USP10-mediated deubiquitination of NEMO, resulting in decreased NF-κB activation upon DNA damage (21). Nevertheless, genetic deletion of either SENP2 or MCPIP1 in MEF cells was not sufficient to completely block the resolution of genotoxic NF-κB activation, suggesting that additional negative regulatory mechanisms controlling genotoxic NF-κB signaling remain to be elucidated.

TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator (TANK, also known as I-TRAF) could interact with the TRAF family members TRAF2 and TRAF3, thereby regulating TRAF-mediated signaling pathways (22–24). In the antiviral immune response following retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 activation, TANK may serve as an adaptor bridging TRAF3 with TBK1 and IKKϵ, which promotes phosphorylation and activation of IRF3/IRF7 as well as induction of NF-κB activation, leading to effective type I IFN production (25–27). Nevertheless, TANK has also been shown to negatively regulate NF-κB activation (28, 29). It has been found that NF-κB activation upon TLR or BCR (B cell receptor) stimulation was augmented in macrophages and B cells isolated from Tank−/− mice compared with their wild-type counterparts. Moreover, TANK deficiency increased TRAF6 ubiquitination in response to TLR activation in macrophages, which may contribute to enhanced NF-κB activation. However, the mechanism by which TANK inhibits TRAF6 ubiquitination remains enigmatic because TANK lacks the deubiquitination enzyme (DUB) domain and TANK does not interact with A20 and CYLD (cylindromatosis), two common DUBs that have been shown to inhibit NF-κB signaling (28).

In this report, we show that TANK inhibits genotoxic stress-induced NF-κB activation, which may be dependent on inhibition of TRAF6 ubiquitination. The TRAF2/3-interacting domain of TANK and the TRAF-C domain of TRAF6 are essential for TANK association with TRAF6. Mechanistically, TANK forms a complex with MCPIP1 and USP10, which promotes USP10-dependent deubiquitination of TRAF6 in cells treated with genotoxic stimuli. TANK is indispensable for TRAF6 deubiquitination by USP10 because deletion of TANK disrupts the association between USP10 and TRAF6, thereby stabilizing TRAF6 ubiquitination upon DNA damage. Moreover, the TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 complex is also responsible for inhibition of TRAF6 ubiquitination in cells treated with LPS or IL-1β. Collectively, our data suggest that TANK may serve as the adaptor for recruiting the USP10-MCPIP1 complex to polyubiquitinated TRAF6, which, in turn, disassembles the polyubiquitin chains anchored on TRAF6, resulting in the termination of NF-κB activation in response to genotoxic stress and IL-1R/TLR activation.

Experimental Procedures

Cells, Plasmids, and Reagents

HEK293T cells, mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (wild-type and MCPIP1−/−), and human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cell lines were maintained in the presence of penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The HA-TANK plasmid was generated by cloning the human TANK coding sequence into the pcDNA3 vector. The TANK siRNA sequence used was UCACUUCAACAGACUAUUAUU, as reported previously (30). Two siRNAs targeting USP10 were used. One was synthesized with the sequence CCC UGA UGG UAU CAC UAA AGA UU, and the other was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (catalog no. 7747). TANK or USP10 knockout cells were generated with the CRISPR-Cas9 system. The pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 vector was purchased from Addgene (catalog no. 42230). TANK-targeting constructs were generated as described previously (31). The small guide RNA sequences targeting TANK were AGCGTATGAAGCCTTCCGGCAGG (protospacer adjacent motif, PAM) and ATCCATGCATGCCTGCCGGAAGG. The sgRNA (single-guide RNA) sequence targeting USP10 was GACTCCTCGATCTTCAGTTGAGG (PAM). HEK293T cells were transfected with individual TANK- or USP10-targeting Cas9 constructs, and stable clones were screened by puromycin selection. Antibodies against HA (catalog no. sc-805), p65 (catalog no. sc-372), IκBα (catalog no. SC-371), IKKα/β (catalog no. sc-7607), NEMO (IKKγ) (catalog no. sc-8330), ubiquitin (catalog no. sc-8017), TRAF6 (catalog no. sc-7221), and Myc (catalog no. sc-40) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against p-p65 (catalog no. 3033), p-IKK (catalog no. 2697), TANK (catalog no. 2141), USP10 (catalog no. 8501), cleaved PARP (catalog no. 5625), and cleaved Caspase3 (catalog no. 9664) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Antibody against Tubulin (catalog no. CP06) was from Oncogene (Cambridge, MA). Antibodies against FLAG (catalog no. F1804) and ELKS (catalog no. E4531) were from Sigma.

EMSA

The Igκ-κB oligonucleotide probe and conditions for EMSA have been described previously (32). The Oct-1 oligonucleotide used for control EMSA reactions was obtained from Promega. Gels were quantified with a Cyclone PhosphorImager (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Luciferase Assay

HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the pGL4.0 Luciferase reporter containing the NF-κB target sequence and Tk-Rluc reporter (Promega). After 48 h, cells were treated and lysed, and the activity of firefly/Renilla luciferase in the lysates was measured with the Dual-Luciferase assay system (Promega).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Briefly, in co-IP experiments, cells were lysed in 10% PBS and 90% IP lysis buffer (20 mm Tris (pH 7.0), 250 mm NaCl, 3 mm EDTA, 3 mm EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 2 mm DTT, 0.5 mm PMSF, 20 mm β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate, and 10 mm sodium fluoride). Then, 1 μg of primary antibody (or control IgG) and protein G-Sepharose were mixed into the lysates and incubated together at 4 °C overnight. Protein G-Sepharose-enriched complexes were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The protein signals were visualized by ECL exposure.

To detect protein ubiquitination, cells were lysed with 1% SDS in IP lysis buffer at 95 °C for 30 min. The cell lysates were then diluted with IP lysis buffer to reduce SDS to 0.1% and mixed with primary antibodies and protein G-Sepharose for incubation at 4 °C overnight. The ubiquitin modification of precipitated proteins was examined by immunoblotting.

GST Pulldown Assay

GST and GST fusion proteins with TANK or TANK mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells. All fusion proteins were precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) and eluted with 10 mm glutathione in 50 mm Tris (pH 8.0) according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences). In the GST pulldown assay, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-MCPIP1/TRAF6 or respective mutants. After 24 h, the cell lysates were prepared. Equal amounts of immobilized GST or GST fusion proteins were mixed and incubated for 3 h at 4 °C with the cell lysates in GST binding buffer containing 40 mm HEPES, 50 mm sodium acetate, 200 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). Glutathione beads were washed three times in the same GST binding buffer. Then the beads were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and the supernatants were collected. Immunoblotting was conducted under standard conditions.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and retrotranscribed with a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). Real-time PCR analyses were performed in triplicate as described previously (33). The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as an internal control. The sequences of gene-specific primers used for quantitative PCR were as follows: GAPDH, 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′ (reverse); cIAP1, 5′-GTTTCAGGTCTGTCACTGGAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGCATACTACCAGATGACCA-3′ (reverse); cIAP2, 5′-TCCTGGATAGTCTACTAACTGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′- GCTTCTTGCAGAGAGTTTCTGAA-3′ (reverse); BCL-XL, 5′-GGTCGCATTGTGGCCTTTTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′- TGCTGCATTGTTCCCATAGAG-3′ (reverse); IL-6, 5′-AGCGCCTTCGGTCCAGTTGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGCTGTCTGTGTGGGGCG-3′ (reverse); and IL-8, 5′-TTGGCAGCCTTCCTGATTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTTTA GCACTCCT GGCAAAAC-3′ (reverse).

Cell Survival Assay

Cells were transfected with plasmids and treated as indicated. Then cells were stained with trypan blue, and live cells were counted with a TC20 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad). Data from three independent experiments were collected and plotted.

Statistical Analysis

The results are presented as mean ± S.D. Student's t test was applied to analyze the significance. p < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

TANK Negatively Regulates Genotoxic Stress-induced NF-κB Activation

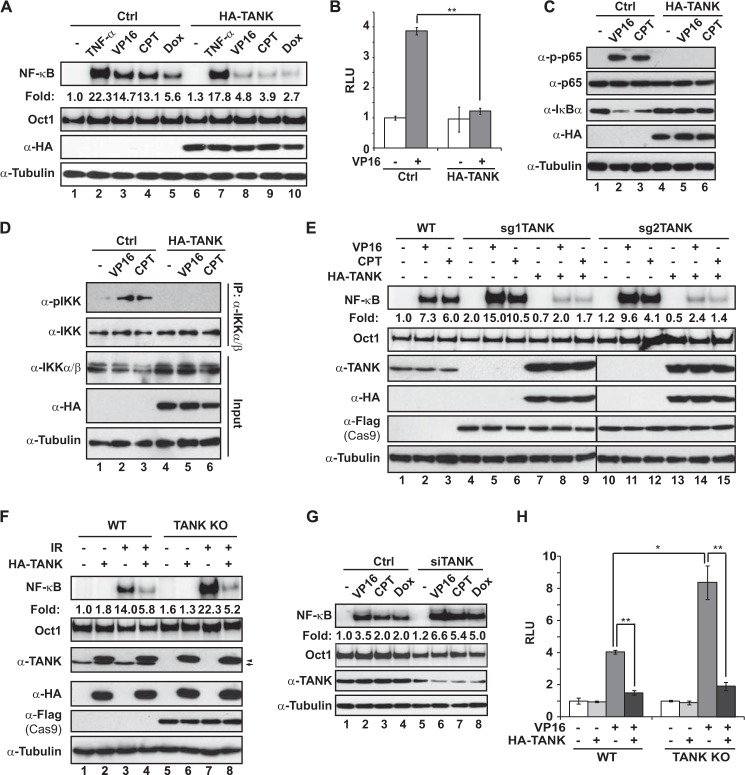

TANK has been shown to inhibit TLR-induced NF-κB activation by attenuating TRAF6 polyubiquitination (28). Interestingly, TRAF6 ubiquitination has been reported to mediate genotoxic stress-induced NF-κB activation (15). We reasoned that TANK may also negatively regulate genotoxic NF-κB activation. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed TANK in HEK293T cells and measured NF-κB activation in response to TNF-α and genotoxic agents such as etoposide (VP16), camptothecin (CPT), and doxorubicin. As expected, TANK overexpression significantly decreased genotoxic agent-induced NF-κB activation, as measured by EMSA (Fig. 1A) and luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 1B). Consistently, VP16 or CPT-induced IKK activation, IκBα degradation, and RelA/p65 phosphorylation were abrogated in cells overexpressing TANK (Fig. 1, C and D), suggesting that increased TANK expression diminishes the NF-κB signaling cascade activated by genotoxic stimulation.

FIGURE 1.

TANK negatively regulates genotoxic stress-induced NF-κB activation. A, control (Ctrl) or HA-TANK-transfected HEK293T cells were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml, 30 min), VP16 (10 μm, 2 h), CPT (10 μm, 2 h), or doxorubicin (Dox, 2 μg/ml, 2 h). Whole cell lysates were analyzed by EMSA (NF-κB and Oct1) and immunoblotting. For EMSA, signals were quantified with a PhosphorImager, and normalized activity (NF-κB/Oct1) is shown as -fold induction. B, HEK293T cells were transfected with the NF-κB-Fluc and Tk-Rluc reporter along with a control or HA-TANK. Cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 4 h), and luciferase activity was quantified. The histogram represents the normalized data (FLuc/RLuc) from three independent experiments, shown as mean ± S.D. **, p < 0.01. RLU, relative luciferase unit. C and D, control or HA-TANK-transfected HEK293T cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 1 h) or CPT (10 μm, 1 h). Whole lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies (C) or immunoprecipitated with IKKα/β antibody followed by immunoblotting (D). E and F, wild-type or TANK knockout HEK293T cells generated with two different sgRNAs were transfected with HA-TANK as indicated. Cells were then treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h) or CPT (10 μm, 2 h) (E) or ionizing radiation (IR, 10 gray, 2 h) (F) and analyzed as in A. Arrow, endogenous TANK; arrowhead, HA-TANK. G, HEK293T cells were transfected with control siRNA or TANK-targeting siRNA. After 48 h, cells were treated and analyzed as in A. H, wild-type or TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected, treated, and analyzed as in B. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

To further validate the role of TANK in modulating the genotoxic NF-κB signaling pathway in human cells, we took advantage of the recently developed CRISPR-Cas9 gene-targeting tools (34) and generated two TANK-targeting CRISPR constructs harboring distinct sgRNAs as reported previously (31). We found both TANK-targeting CRISPR constructs effectively disrupted TANK gene expression in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1E, lanes 4–6 and 10–12), to which we hereafter refer as TANK KO cells. Accordingly, TANK deletion significantly enhanced NF-κB activation by VP16 or CPT, which can be attenuated by reconstitution of TANK in TANK KO cells (Fig. 1E). In addition to chemotherapeutic drugs, ionizing radiation-induced NF-κB activation was also attenuated or escalated in cells overexpressing TANK or with TANK deletion, respectively (Fig. 1F). To further confirm the results from TANK KO cells, we used siRNA to knock down TANK in HEK293T cells. Consistently, suppression of TANK expression by siRNA also substantially enhanced NF-κB activation by genotoxic drugs (Fig. 1G). Moreover, NF-κB-dependent transcription upon DNA damage was further enhanced in TANK KO cells, which could be attenuated by overexpressing TANK (Fig. 1H). Taken together, our data indicate that TANK is a negative regulator of the NF-κB signaling cascade in cells exposed to genotoxic stress.

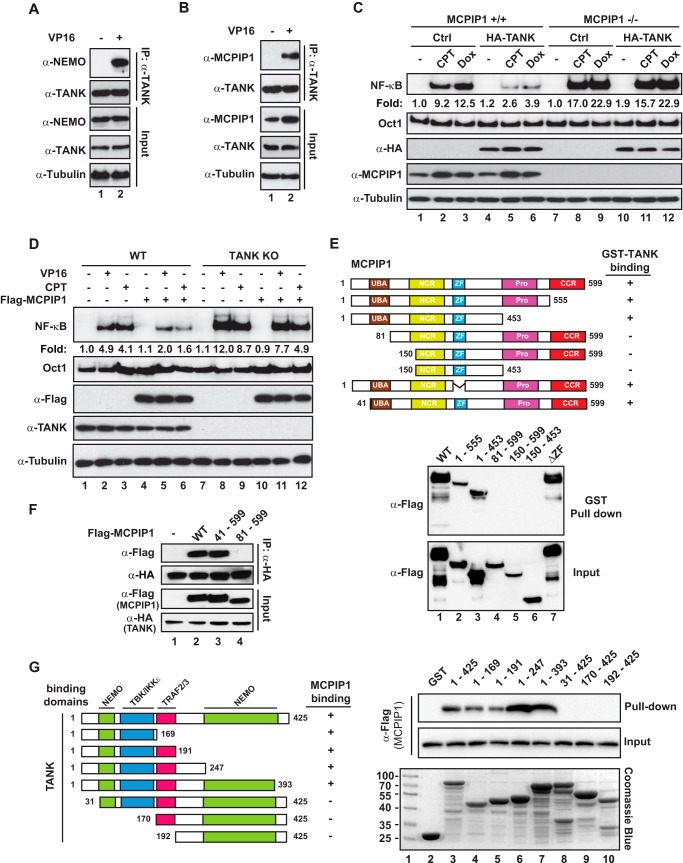

MCPIP1 Is Required for TANK-dependent Repression of NF-κB Activation by DNA Damage

Previous studies have indicated that TANK-associated TBK1 could inhibit NF-κB signaling by phosphorylating the canonical IKK complex (35, 36). We found that pharmacological inhibition of TBK1 with amlexanox did not affect TANK-dependent inhibition of genotoxic NF-κB activation (data not shown), suggesting that additional TANK-associated partners may be involved in TANK-mediated NF-κB inhibition. The association between TANK and NEMO has been reported previously (37). Moreover, TANK has also been identified as a MCPIP1-associated protein in a yeast two-hybrid screen (38). We confirmed the association between TANK and NEMO or MCPIP1 in cells treated with VP16 (Fig. 2, A and B). Interestingly, TANK overexpression was able to inhibit NF-κB activation by genotoxic agents in wild-type but not in MCPIP1-deficient MEFs (Fig. 2C), suggesting that MCPIP1 may be required for TANK to inhibit genotoxic NF-κB activation. Reciprocally, although overexpressing MCPIP1 was able to partially decrease NF-κB activation by genotoxic drugs in TANK KO cells (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 11 and 12 with lanes 8 and 9), the extent of MCPIP1-dependent NF-κB suppression was substantially dampened. These data indicate that MCPIP1 and TANK are mutually required for effective suppression of genotoxic NF-κB activation by overexpressing either MCPIP1 or TANK.

FIGURE 2.

MCPIP1 is required for TANK repression of genotoxic NF-κB activation. A and B, HEK293T cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h), and whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the antibody against TANK. The precipitates were immunoblotted with the antibody against NEMO (A) or MCPIP1 (B). C, wild-type and MCPIP1-deficient MEFs were transfected with HA-TANK as indicated. Cells were treated with CPT (10 μm, 2 h) or doxorubicin (Dox, 2 μg/ml, 2 h). Whole cell lysates were analyzed by EMSA (NF-κB and Oct1) and immunoblotting. Normalized NF-κB activation (NF-κB/Oct1) is shown as -fold induction. Ctrl, control. D, wild-type and TANK-KO HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-MCPIP1 or a control plasmid. After 48 h, cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h) or CPT (10 μm, 2 h) and analyzed as in C. E, cell lysates containing FLAG-MCPIP1 wild-type or the respective mutants were incubated with recombinant GST-TANK proteins. TANK-associated proteins were enriched by IP with glutathione beads and detected by immunoblotting. UBA, ubiquitin associated domain; NCR, N-terminal conserved region; proline rich domain; CCR, C-terminal conserved region. F, HEK293T cells transfected with HA-TANK alone or along with FLAG-MCPIP1 WT or mutant as indicated. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA, followed by immunoblotting with the antibodies as shown. IR, ionizing radiation. G, wild-type or the indicated mutants of recombinant GST-TANK proteins were incubated with cell lysates containing FLAG-MCPIP1 wild-type proteins. TANK-associated FLAG-MCPIP1 was analyzed as in E. Input GST-TANK proteins were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

To further characterize the interaction between MCPIP1 and TANK, we generated a series of MCPIP1 truncation/deletion mutants (Fig. 2E, top panel) and recombinant GST-TANK protein. Cell lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with MCPIP1 wild-type or an individual mutant were subjected to an in vitro pulldown assay with GST-TANK. As shown in Fig. 2E, we found that the MCPIP1 N terminus (amino acids 1–81) was required for interaction with TANK. Moreover, deletion of the N-terminal 40 amino acids had little impact on MCPIP1 interaction with TANK, indicating the that the UBA domain (ubiquitin associated domain) is critical for the association between MCPIP1 and TANK (Fig. 2F). In parallel, we also generated a number of truncated GST-TANK recombinant proteins (Fig. 2G, left panel) that were incubated with cell lysates from HEK293T cells expressing wild-type MCPIP1. Our data further suggested that the N-terminal fragment (amino acids 1–31) of TANK was essential for the association between TANK and MCPIP1.

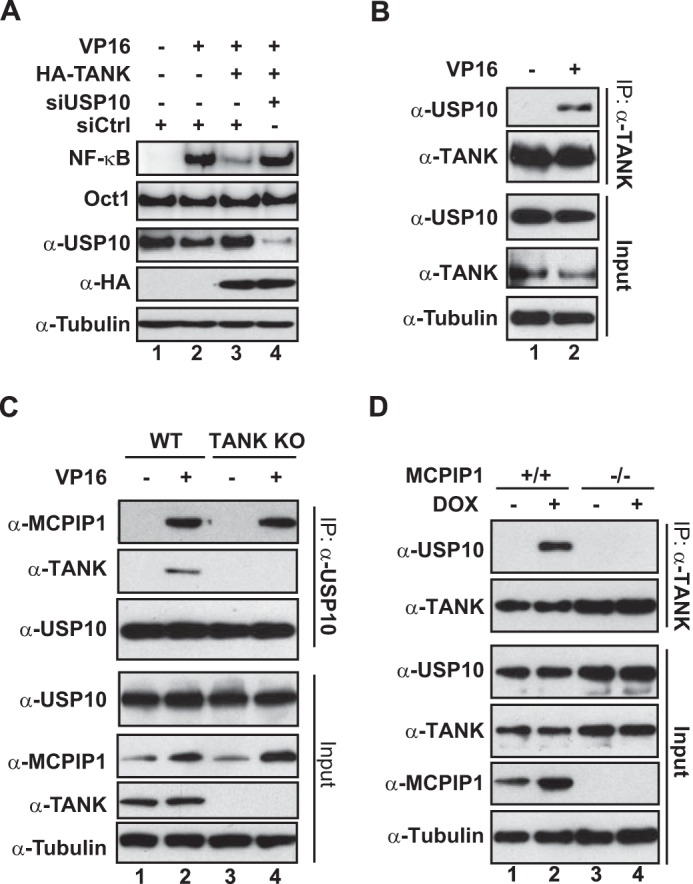

TANK-associated USP10 Is Essential for TANK to Inhibit Genotoxic NF-κB Activation

We showed recently that MCPIP1 association with USP10, a bona fide DUB, is required for MCPIP1-dependent inhibition of genotoxic NF-κB signaling (21). USP10 removes the linear ubiquitin chain attached to NEMO en bloc, thereby attenuating NF-κB activation signaling upon DNA damage. Because we found that TANK formed a complex with MCPIP1, and both were mutually required for NF-κB inhibition, we asked whether USP10 is involved in TANK-dependent negative regulation of NF-κB. To this end, we depleted USP10 with siRNA in HEK293T cells. We found that USP10 knockdown almost abrogated TANK-dependent inhibition of NF-κB activation in VP16-treated cells (Fig. 3A), indicating that USP10 is critical for TANK to negatively regulate NF-κB signaling upon DNA damage. We further confirmed the inducible association between TANK and USP10 in cells treated with VP16 (Fig. 3B), which suggested that TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 may form a functional complex in response to genotoxic stress. Further coimmunoprecipitation analyses showed that TANK was dispensable for the interaction between MCPIP1 and USP10, whereas MCPIP1 was essential for TANK to interact with USP10 (Fig. 3, C and D). Therefore, MCPIP1 likely served as a bridge to anchor both TANK and USP10 into the same complex.

FIGURE 3.

USP10 is required for TANK to inhibit NF-κB activation. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK along with control siRNA (siCtrl) or USP10-targeting siRNA as indicated. After 48 h, cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h), and whole cell lysates were analyzed by EMSA (NF-κB and Oct1) and immunoblotting. B, HEK293T cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h), and then whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody against TANK. The precipitates were immunoblotted with antibodies as shown. C, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h), and whole lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody against USP10, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. D, wild-type and MCPIP1-deficient MEFs were treated with doxorubicin (DOX, 2 μg/ml, 2 h) and analyzed as in B.

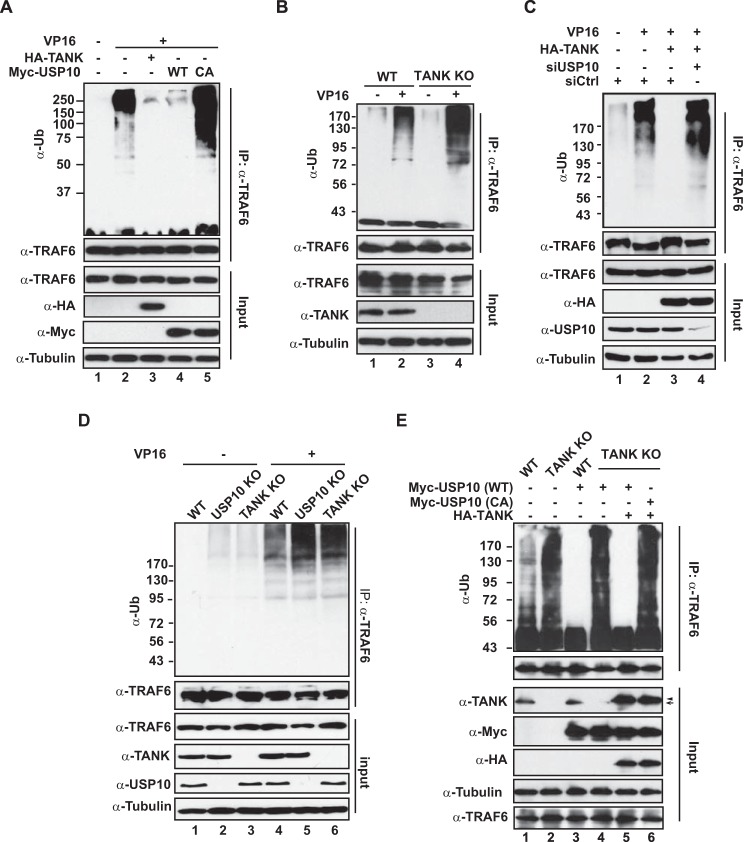

USP10 Is Required for TANK-promoted Deubiquitination of TRAF6

In response to TLR activation, TRAF6 ubiquitination was enhanced in mouse cells deficient of TANK (28). We found that VP16-induced TRAF6 polyubiquitination was decreased significantly in cells overexpressing TANK (Fig. 4A, lane 3), suggesting that TANK may also promote TRAF6 deubiquitination in response to genotoxic stress. This notion was supported by our observation that TRAF6 ubiquitination was further enhanced in TANK KO cells upon VP16 treatment (Fig. 4B). In parallel, we found that overexpression of wild-type USP10, but not its catalytic-inactive mutant (C424A), also abolished VP16-induced TRAF6 polyubiquitination (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 5). Considering the lack of a DUB domain in TANK and the inducible association between TANK and USP10, we speculated that USP10 may facilitate TANK-dependent deubiquitination. As expected, we found that overexpression of TANK failed to decrease genotoxic stress-induced TRAF6 polyubiquitination in USP10-depleted cells (Fig. 4C). In accordance, we found that VP16-induced TRAF6 ubiquitination was comparably enhanced in cells deficient of TANK or USP10 (Fig. 4D). Reciprocally, overexpression of USP10 was able to diminish TRAF6 polyubiquitination in wild-type cells, but not in TANK KO cells, upon genotoxic treatment (Fig. 4E, compare lanes 3 and 4). Moreover, the defect of USP10 in deubiquitinating TRAF6 in TANK KO cells can be rescued by ectopic expression of TANK (Fig. 4E, compare lanes 4 and 5). These results indicate that USP10 is the essential DUB for TANK to inhibit DNA damage-induced ubiquitination of TRAF6, whereas TANK is indispensable for TRAF6 deubiquitination by USP10.

FIGURE 4.

USP10 is essential for TANK-dependent deubiquitination of TRAF6 upon genotoxic stress. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK, wild-type USP10 or catalytically inactive (CA) USP10 (C424A) as indicated and treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h). TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed with TRAF6 immunoprecipitation under denatured conditions, followed by immunoblotting. B, wild-type or TANK KO HEK293T cells were treated with VP16. TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed as in A. C, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK along with control (siCtrl) or USP10-targeting siRNA. Cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h), and TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed as in A. D, wild-type HEK293T cells, USP10 KO cells, or TANK KO cells were treated with VP16, and TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed as in A. E, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK, wild-type USP10 (WT) or catalytically inactive USP10 as indicated. TRAF6 ubiquitination following VP16 (10 μm, 2 h) treatment was analyzed as in A.

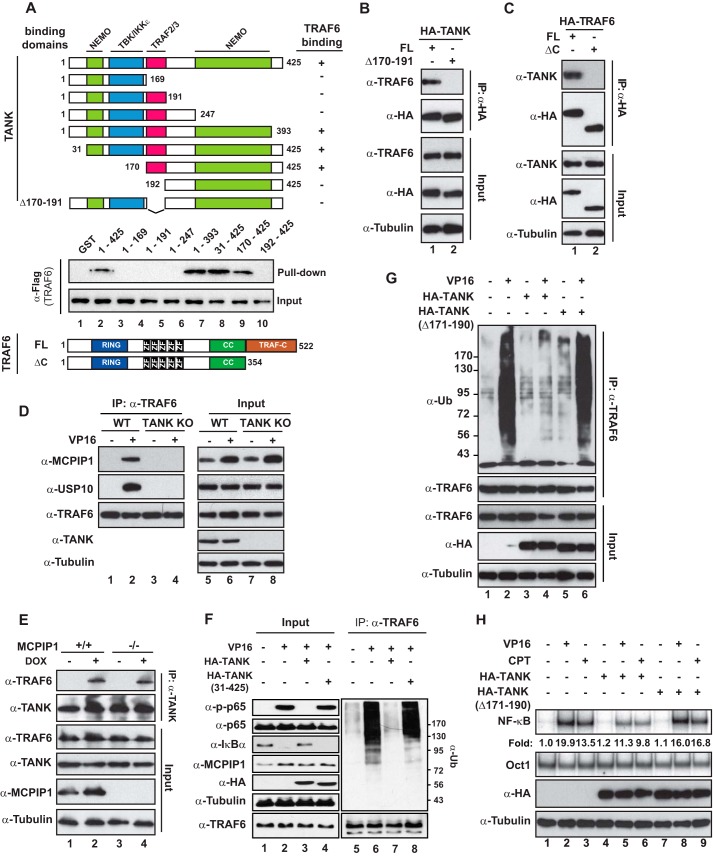

The Interaction between TANK and TRAF6 Was Required for Inhibition of Genotoxic Stress-induced NF-κB Activation

The indispensable role of TANK in mediating USP10-dependent TRAF6 deubiquitination suggested that TANK may directly interact with TRAF6, which recruits USP10 to the ubiquitinated TRAF6. TANK has been shown to interact with TRAF1/2/3 via a TRAF-binding domain located at the center region (24). Our in vitro pulldown assay indicated that the TRAF-binding domain is also required for TANK association with TRAF6 (Fig. 5A). A C-terminal region of TANK, which was identified as part of NEMO-binding domain (37), was also important for the TANK-TRAF6 interaction. In accordance, deletion of the TRAF-binding domain (amino acids 170–191) completely abrogated the interaction between TANK and TRAF6 (Fig. 5B). The essential region required for TRAF6 to interact with TANK was mapped to the TRAF-C domain (Fig. 5C), which is consistent with that identified in other TRAF family members (23, 24).

FIGURE 5.

The TRAF-binding domain of TANK is required for USP10 to deubiquitinate TRAF6. A, recombinant full-length GST-TANK or varying mutants harboring different binding domains were incubated with lysates from HEK293 cells expressing FLAG-TRAF6. TANK-associated TRAF6 was determined by IP with glutathione beads, followed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. A diagram of the TRAF6 function domain is shown at the bottom. RING, really interesting new gene domain; CC, coiled coil domain; FL, full length. B, HEK293T cells were transfected with wild-type HA-TANK or a TANK mutant with TRAF-binding domain depletion (Δ170–191). Whole cell lysates were subjected to IP with anti-HA and followed by immunoblotting as indicated. C, Similar analyses as in B were carried out in HEK293T cells transfected with HA-TRAF6 wild-type or a TRAF-C depletion mutant. D, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h). Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody against TRAF6. The precipitates were immunoblotted as indicated. E, wild-type and MCPIP1−/− MEFs were treated with doxorubicin (DOX, 2 μg/ml, 2 h), and whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-TANK antibody, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. F, TANK KO cells were transfected with a vector control, TANK WT, or TANK (31–425) mutant. Cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h), and TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed by TRAF6 IP, followed by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin (Ub). Input whole cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. G and H, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK or TRAF-binding domain-depleted TANK mutants as shown. Cells were then treated with VP16 (10 μm, 2 h) or CPT (10 μm, 2 h). Whole cell lysates were subjected to analyses of TRAF6 ubiquitination (G) or analyzed by EMSA (NF-κB and Oct1) and immunoblotting (H). Normalized NF-κB activation (NF-κB/Oct1) is shown as -fold induction.

To examine the role of TANK in mediating TRAF6 and USP10 interaction, we performed co-IP analyses in both wild-type and TANK KO cells. As we expected, the genotoxic treatment-induced association between TRAF6 and USP10 was abolished in TANK KO cells (Fig. 5D). Similarly, genotoxic treatment also promoted the interaction between TRAF6 and MCPIP1, which was diminished by TANK deletion. In contrast, MCPIP1 deficiency did not affect the interaction between TANK and TRAF6 in cells exposed to genotoxic drugs (Fig. 5E). Nevertheless, TANK KO cell reconstitution with the MCPIP1 binding-deficient TANK mutant (31–425, Fig. 2G) failed, whereas TANK WT reconstitution was sufficient to suppress TRAF6 ubiquitination by VP16 (Fig. 5F). These data suggested that TANK served as an essential adaptor to assemble MCPIP1-USP10 and TRAF6 into the same complex, thereby diminishing TRAF6 polyubiquitination. In support of this notion, we found that the TRAF-binding deficient mutant of TANK failed to inhibit TRAF6 ubiquitination in cells treated with VP16 (Fig. 5G). Moreover, only wild-type TANK, but not its TRAF binding-deficient mutant, was able to attenuate NF-κB activation by genotoxic drugs (Fig. 5H), indicating that TANK association with TRAF6 plays a critical role in mediating TANK-MCPIP1-USP10-dependent inhibition of TRAF6 ubiquitination and subsequent NF-κB activation upon DNA damage.

TANK also Facilitates the Deubiquitination of NEMO in Response to Genotoxic Stress

We found that NEMO was attached to the linear ubiquitin chain upon DNA damage, which is required for genotoxic NF-κB activation (18). In a negative feedback response, NF-κB-up-regulated MCPIP1 could facilitate the USP10-dependent removal of the linear ubiquitin chain from NEMO, thereby inhibiting NF-κB activation upon DNA damage (21). Because we found that genotoxic treatment also induced the interaction between NEMO and TANK (Fig. 2A), we speculate that TANK may also regulate NEMO ubiquitination by genotoxic stress. Indeed, we found that VP16-induced NEMO ubiquitination was substantially enhanced in TANK KO cells (Fig. 6A), suggesting that TANK may inhibit NEMO ubiquitination. This TANK-mediated suppression of NEMO ubiquitination is specific because we did not detect a significant change in ELKS ubiquitination, another signaling event required for genotoxic NF-κB activation (16), in TANK KO cells upon genotoxic stimulation (Fig. 6B). However, TANK deletion only partially reduced USP10-dependent NEMO deubiquitination (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 2 and 4). Consistently, we were able to detect an interaction between MCPIP1-USP10 and NEMO in TANK KO cells, although at a reduced level (Fig. 6D). All of these results suggest that MCPIP1-USP10 may mediate the deubiquitination of NEMO upon genotoxic stress in both a TANK-dependent and TANK-independent manner.

FIGURE 6.

TANK enhances NEMO deubiquitination by MCPIP1/USP10 upon DNA damage. A, wild-type and TANK-deficient HEK293T cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm) for 2 h. VP16-induced NEMO ubiquitination was analyzed with NEMO IP under denatured conditions. The immunoprecipitates were further analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Ub, ubiquitin. B, VP16-induced ELKS ubiquitination was analyzed as in A. C, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK, wild-type USP10 (WT), or catalytically inactive USP10 (CA) as indicated. NEMO ubiquitination following VP16 (10 μm, 2 h) treatment was analyzed as in A. D, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm) for 2 h. Whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-NEMO antibody and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies as shown.

The TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 Complex Inhibits IL-1R/TLR-mediated NF-κB Activation by Deubiquitinating TRAF6

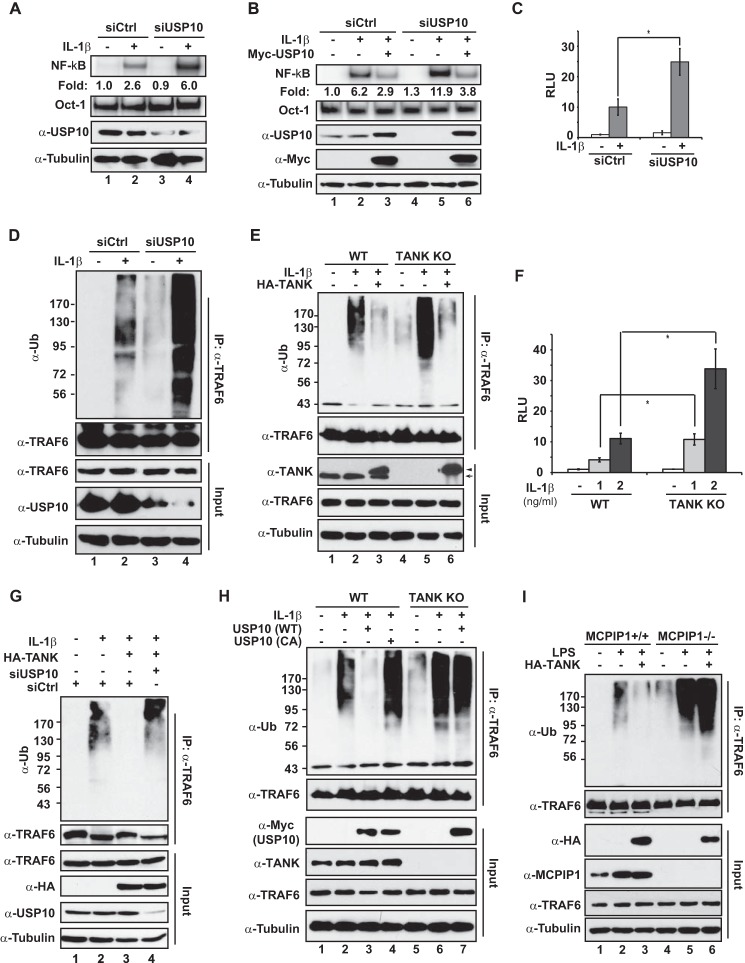

Both TANK and MCPIP1 have been shown to suppress NF-κB activation by IL-1β treatment or TLR activation (28, 39). Deubiquitination of TRAF proteins was identified as the underlying mechanism by which TANK and MCPIP1 inhibit NF-κB signaling. Interestingly, neither TANK nor MCPIP1 harbor a DUB domain, suggesting that the TANK/MCPIP1-associated DUB is required for the deubiquitination of TRAF proteins. Because we found that TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 formed a complex and promoted TRAF6 deubiquitination in response to genotoxic stress, we wondered whether the TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 complex could play a role in suppressing IL-1R/TLR-mediated NF-κB activation. To test this hypothesis, we depleted USP10 with siRNA in HEK293T cells and treated the cells with IL-1β. We found that knockdown of USP10 significantly enhanced IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 7A). Consistent results were observed in cells where USP10 was depleted with another siRNA targeting a different sequence (Fig. 7B). Moreover, ectopic expression of USP10 suppressed IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation and diminished the enhanced NF-κB activation by IL-1β in USP10-depleted cells. These results were further confirmed by a NF-κB reporter assay showing that depletion of USP10 enhanced IL-1β-induced NF-κB transactivity (Fig. 7C). In accordance, TRAF6 ubiquitination was also remarkably increased in cells depleted of USP10, suggesting that USP10 may negatively regulate IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation by deubiquitinating TRAF6 (Fig. 7D).

FIGURE 7.

The TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 complex inhibits IL-1R/TLR-mediated NF-κB activation by deubiquitinating TRAF6. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with control siRNA (siCtrl) or USP10-specific siRNA (CST#7747). Cells were treated with IL-1β (2 ng/ml, 30 min) and then analyzed by EMSA (NF-κB and Oct1) and immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Normalized NF-κB activation (NF-κB/Oct1) is shown as -fold induction. B, HEK293T cells were transfected with control siRNA or USP10-targeting siRNA alone or along with Myc-USP10 (siRNA-resistant). 48 h later, cells were treated with IL-1β (2 ng/ml, 30 min). Whole cell lysates were analyzed as in A. C, HEK293T cells were transfected as in A and treated with IL-1β (2 ng/ml) for 2 h. NF-κB luciferase reporter activity was measured with a Dual-Luciferase assay, and data from three independent experiments were pooled and are shown as mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05. RLU, relative luciferase unit. D, HEK293T cells were transfected and treated as in A. TRAF6 ubiquitination in response to IL-1β treatment was analyzed with TRAF6 IP, followed by immunoblotting as indicated. Ub, ubiquitin. E, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK as indicated. Cells were treated with IL-1β (2 ng/ml) for 1 h, and TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed as in D. Arrow, endogenous TANK; arrowhead, HA-TANK. F, IL-1β-induced NF-κB luciferase reporter activity in wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells was determined as in C. *, p < 0.05. G, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK along with control siRNA or USP10-targeting siRNA as indicated. After 48 h, cells were treated with IL-1β (2 ng/ml, 30 min), and TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed as in D. H, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-USP10 (WT) or Myc-USP10 (CA) as shown. TRAF6 ubiquitination in response to IL-1β treatment was analyzed as in D. I, wild-type and MCPIP1-deficient MEFs were transfected with HA-TANK or a control. 48 h later, cells were treated with LPS (10 μg/ml, 30 min), and LPS-induced TRAF6 ubiquitination was analyzed as in D.

Consistent with previous reports (28, 29), TRAF6 ubiquitination was increased substantially in TANK KO HEK293T cells treated with IL-1β, whereas overexpression of TANK suppressed TRAF6 ubiquitination (Fig. 7E). Moreover, deletion of TANK significantly enhanced IL-1β-induced NF-κB-dependent transcription (Fig. 7F). In parallel, USP10 was indispensable for the TANK-promoted deubiquitination of TRAF6 because knockdown of USP10 abrogated TRAF6 deubiquitination by TANK overexpression (Fig. 7G). Because we found that TANK was an essential partner for USP10 to deubiquitinate TRAF6, we examined whether ectopic USP10 could inhibit IL-1β-induced TRAF6 ubiquitination in the absence of TANK. As shown in Fig. 7H, overexpressing USP10 was able to inhibit TRAF6 ubiquitination in wild-type cells but not in TANK KO cells (compare lanes 3 and 7). In parallel, we found that LPS-induced TRAF6 ubiquitination was resistant to TANK overexpression in MCPIP1-deficient MEFs (Fig. 7I). Together, our data indicate that USP10/MCPIP1/TANK likely also form a deubiquitinating complex in response to IL-1R/TLR activation, which, in turn, suppresses NF-κB activation by diminishing TRAF6 ubiquitination.

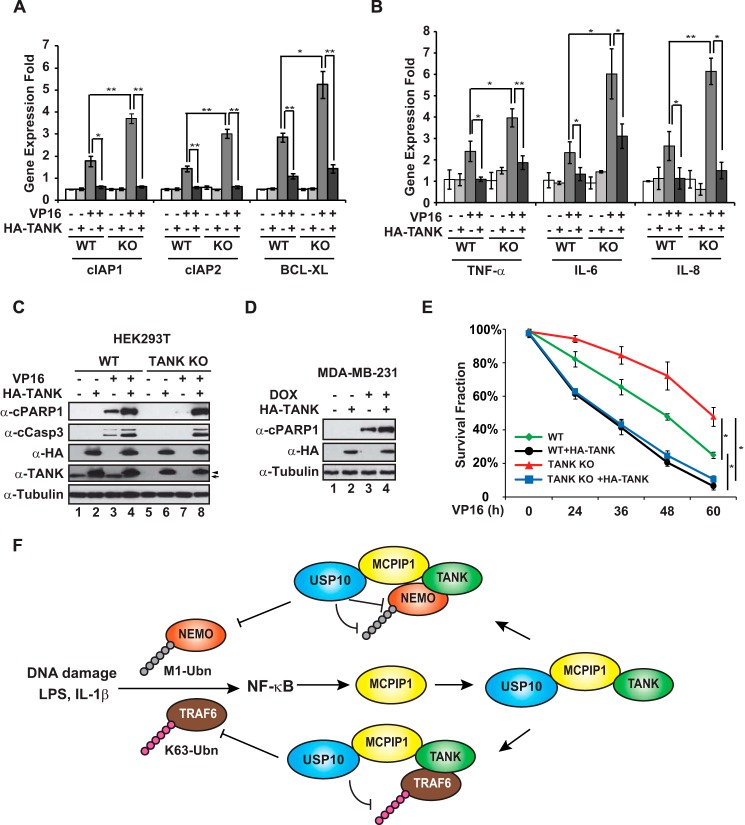

TANK Overexpression Decreases Cell Survival upon DNA Damage

We found that increased expression of the anti-apoptosis genes BIRC2, BIRC3, and BCL2L1 by VP16 treatment was further enhanced in TANK KO cells (Fig. 8A). Moreover, TANK overexpression abrogated the induction of cIAP1, cIAP2, and BCL-XL in both wild-type and TANK KO cells. In parallel, TANK deletion also further increased the VP16-induced transcription of the cytokine genes TNF, IL6, and CXCL8, which was suppressed by reconstitution of TANK (Fig. 8B). Our previous studies have demonstrated that the transcription of these genes in response to genotoxic stress is regulated by NF-κB, which may contribute to reduced apoptosis and prolonged cell survival upon DNA damage (5, 16, 18). Accordingly, we found that genotoxic drug-induced apoptosis was attenuated in TANK KO cells compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 8C, compare lanes 3 and 7). In contrast, overexpressing TANK increased cell apoptosis in both HEK293T and MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to genotoxic drugs (Fig. 8, C and D). In agreement, TANK KO cells were more resistant to VP16 treatment compared with wild-type cells, whereas TANK overexpression significantly reduced cell survival upon genotoxic treatment (Fig. 8E). All of these data further support the hypothesis that TANK may promote genotoxic stress-induced cell apoptosis through inhibiting NF-κB activation.

FIGURE 8.

TANK overexpression promotes cell apoptosis upon DNA damage. A and B, wild type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK or a control vector. After 48 h, cells were treated with VP16 (10 μm, 4 h), and expression of the antiapoptosis genes cIAP1, cIAP2, and BCL-XL (A) as well as the cytokine genes TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 (B) was measured by quantitative RT-PCR. GAPDH expression was used as the internal control. Normalized -fold change data were from three independent experiments and are shown as mean ± S.D. C, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK as shown. Cells were treated with VP16 (1 μm) for 24 h and whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Arrow, endogenous TANK; arrowhead, HA-TANK. D, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with HA-TANK or a control vector. Cells were treated with doxorubicin (DOX, 0.5 μm) for 24 h and analyzed as in C. E, wild-type and TANK KO HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-TANK or a control for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 1 μm VP16 for the indicated times, and the survival fraction of the cells was determined by trypan blue staining. The cell survival fraction data are from three independent experiments and are shown as mean ± S.D. F, a model illustrating the TANK/MCPIP1/USP10-mediated negative feedback response to suppress NF-κB activation via deubiquitinating TRAF6 and NEMO. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Discussion

Studies in the last decade have provided significant insights into how genotoxic stress induces NF-κB activation through an atypical nuclear-to-cytoplasmic signaling cascade that may play critical roles in mediating acquired therapeutic resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in cancer cells (2, 8). In this genotoxic NF-κB signaling pathway, a variety of protein posttranslational modifications, such as SUMOylation, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, were found to be involved in mediating signal transduction. Multiple forms of ubiquitination, including monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination with Lys-63, Met-1, and Lys-48 linkages, have been shown to play distinct roles in transducing the nuclear DNA damage signal to the cytoplasmic IKK complex, leading to NF-κB activation (2, 40). Because these posttranslational modifications are reversible, they may serve as signaling switches to regulate the extent and duration of genotoxic NF-κB activation. Indeed, a recent study showed that a SUMO protease, SENP2, was induced by NF-κB activation in response to DNA damage, which, in turn, inhibited NEMO SUMOylation, leading to decreased genotoxic NF-κB activation (20). We found that MCPIP1 transcription was enhanced by NF-κB upon genotoxic stress, which served as a scaffold protein to promote USP10-dependent deubiquitination of NEMO, thereby attenuating NF-κB activation (21). In this study, we further showed that TANK was a member of the MCPIP1-USP10-associated complex induced by genotoxic stress. NF-κB-mediated up-regulation of MCPIP1 enhanced complex formation among MCPIP1, USP10, and TANK, which played an important role as a negative feedback response to attenuate NF-κB activation by diminishing polyubiquitination of both NEMO and TRAF6 (Fig. 8F). Although TANK is indispensable for MCPIP1/USP10-dependent TRAF6 deubiquitination upon genotoxic stress, USP10 was still able to partially decrease NEMO ubiquitination in TANK KO cells, suggesting that a TANK-independent mechanism may also promote the deubiquitination of NEMO. Nevertheless, TANK deletion remarkably reduced the interaction between NEMO and MCPIP1-USP10 and USP10-promoted NEMO deubiquitination, indicating that the interaction between TANK and NEMO may further reinforce NEMO association with the MCPIP1-USP10 complex, thereby enhancing the removal of polyubiquitin chains anchored on NEMO.

The polyubiquitin chains attached on TRAF6 and NEMO in response to genotoxic stress have been characterized as a Lys-63-linked chain and linear chain, respectively (15, 18). Recent studies from Keusekotten et al. (41) and Rivkin et al. (42) demonstrated that OTU deubiquitinase with linear linkage specificity (OTULIN/Gumby/FAM105B) is a linear ubiquitin chain-specific DUB that disassembles a linear ubiquitin chain by cleaving the peptide bond-linked ubiquitin molecules (41, 42). We found that MCPIP1-associated USP10 was able to remove the linear polyubiquitin chain from NEMO in cells exposed to genotoxic stimuli, likely by cleaving isopeptide bond between NEMO and the first ubiquitin and having the Met-1-linked linear chain removed en bloc. In contrast, USP10 was able to disassemble the Lys-63-linked chain by cleaving the individual ubiquitin moiety (21). Another well characterized DUB, CYLD, was also found to cleave both the Lys-63 chain and linear chain in vitro (43) and form a complex with OTULIN to suppress linear ubiquitination in cells (44). We found that overexpression of CYLD or OTULIN diminished NEMO linear ubiquitination by genotoxic stress, whereas deletion of TANK had little impact on CYLD/OTULIN-dependent deubiquitination of NEMO (data not shown). These observations suggest that TANK selectively participates in USP10-dependent deubiquitination of NEMO, likely through interaction with MCPIP1.

USP10 has been shown to regulate the cellular response to DNA damage by deubiquitinating and stabilizing p53, which requires its translocation into the nucleus and phosphorylation by ATM (45). Moreover, USP10 could stabilize Beclin1 by inhibiting its ubiquitination, which reciprocally stabilizes USP10 and promotes p53-dependent apoptosis (46). A recent report found that USP10 could interact with and deubiquitinates SIRT6, which enhanced SIRT6 stability and resulted in SIRT6/p53-dependent suppression of c-Myc oncogenic activity (47). All of these studies indicate that USP10 may play a tumor-suppressive role by deubiquitinating and stabilizing critical tumor suppressors. Here we show that USP10 may also suppress tumor progression by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. In cancer cells exposed to genotoxic treatment, USP10 may diminish NF-κB activation by removing polyubiquitin chains attached on NEMO and TRAF6, which disrupts the signaling scaffold required for effective IKK activation, thereby sensitizing cancer cells to cytotoxic treatment.

Our data indicate that TANK-associated MCPIP1-USP10 may also suppress NF-κB activation in the inflammatory response upon IL1R/TLR activation. It has been found that LPS-induced ubiquitination of TRAF2, TRAF3, and TRAF6 was increased substantially in MCPIP1−/− macrophages (39). Similarly, TRAF6 ubiquitination was enhanced significantly in Tank−/− B cells and macrophages upon TLR stimulation (28). Consistently, escalated NF-κB activation and hyperinflammation were observed in both Zc3h12a−/− and Tank−/− mice. Although both TANK and MCPIP1 were implicated in promoting the deubiquitination of TRAF proteins, the underlying mechanism was elusive because neither of the proteins harbor a well defined DUB domain. Our study demonstrated that USP10 forms a complex with TANK and MCPIP1 and is essential for TANK-dependent deubiquitination of TRAF6 in response to IL-1β treatment and genotoxic stress, suggesting that USP10 may be the missing link responsible for the DUB activity of the TANK-MCPIP1-associated complex.

In summary, the results presented in this study imply that TANK negatively regulates genotoxic NF-κB activation by diminishing the ubiquitination of TRAF6 and NEMO, which relies on the formation of a deubiquitinating complex comprised of TANK, MCPIP1, and USP10. TANK plays an essential role as a scaffold protein, bridging the interaction between TRAF6 and MCPIP1-USP10, which facilitates USP10-dependent deubiquitination. Our data further suggest that this TANK-MCPIP1-USP10 complex may also be responsible for inhibiting the ubiquitination of TRAF family proteins in response to IL-1R/TLR activation, which may prevent hyperinflammation and other pathological processes because of uncontrolled activation of NF-κB signaling. Therefore, modulating the TANK-mediated inhibition of NF-κB activation may serve as a valuable therapeutic approach to mitigate cancer therapeutic resistance and prevent autoimmune diseases.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by NCI/National Institutes of Health grant R01CA149251 (to Z. W.). This work was also supported by American Cancer Society Grant RSG-13-186-01-CSM (to Z. W.).

- NEMO

- NF-κB essential modifier

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-like modifier

- CYLD

- cylindromatosis

- ELKS

- glutamine-, leucine-, lysine-, and serine-rich protein

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- TANK

- TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator

- DUB

- deubiquitination enzyme

- TRAF

- TNF receptor-associated factor

- CRISPR

- clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- CPT

- camptothecin.

References

- 1. Baldwin A. S. (2012) Regulation of cell death and autophagy by IKK and NF-κB: critical mechanisms in immune function and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 246, 327–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCool K. W., Miyamoto S. (2012) DNA damage-dependent NF-κB activation: NEMO turns nuclear signaling inside out. Immunol. Rev. 246, 311–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang C. Y., Mayo M. W., Korneluk R. G., Goeddel D. V., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (1998) NF-κB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science 281, 1680–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nakanishi C., Toi M. (2005) Nuclear factor-κB inhibitors as sensitizers to anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer 5, 297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Niu J., Shi Y., Tan G., Yang C. H., Fan M., Pfeffer L. M., Wu Z. H. (2012) DNA damage induces NF-κB-dependent microRNA-21 upregulation and promotes breast cancer cell invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 21783–21795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6. Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2012) NF-κB, the first quarter-century: remarkable progress and outstanding questions. Genes Dev. 26, 203–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oeckinghaus A., Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2011) Crosstalk in NF-κB signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 12, 695–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hinz M., Scheidereit C. (2014) The IκB kinase complex in NF-κB regulation and beyond. EMBO Rep. 15, 46–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang T. T., Wuerzberger-Davis S. M., Wu Z. H., Miyamoto S. (2003) Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKγ by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-κB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell 115, 565–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janssens S., Tinel A., Lippens S., Tschopp J. (2005) PIDD mediates NF-κB activation in response to DNA damage. Cell 123, 1079–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mabb A. M., Wuerzberger-Davis S. M., Miyamoto S. (2006) PIASy mediates NEMO sumoylation and NF-κB activation in response to genotoxic stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stilmann M., Hinz M., Arslan S. C., Zimmer A., Schreiber V., Scheidereit C. (2009) A nuclear poly(ADP-Ribose)-dependent signalosome confers DNA damage-induced IκB kinase activation. Mol. Cell 36, 365–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jin H.-S., Lee D.-H., Kim D.-H., Chung J.-H., Lee S.-J., Lee T. H. (2009) cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP act cooperatively via nonredundant pathways to regulate genotoxic stress-induced nuclear factor-κB Activation. Cancer Res. 69, 1782–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu Z. H., Shi Y., Tibbetts R. S., Miyamoto S. (2006) Molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-κB signaling in response to genotoxic stimuli. Science 311, 1141–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hinz M., Stilmann M., Arslan S. Ç., Khanna K. K., Dittmar G., Scheidereit C. (2010) A cytoplasmic ATM-TRAF6-cIAP1 module links nuclear DNA damage signaling to ubiquitin-mediated NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell 40, 63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu Z. H., Wong E. T., Shi Y., Niu J., Chen Z., Miyamoto S., Tergaonkar V. (2010) ATM- and NEMO-dependent ELKS ubiquitination coordinates TAK1-mediated IKK activation in response to genotoxic stress. Mol. Cell 40, 75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang Y., Xia F., Hermance N., Mabb A., Simonson S., Morrissey S., Gandhi P., Munson M., Miyamoto S., Kelliher M. A. (2011) A cytosolic ATM/NEMO/RIP1 complex recruits TAK1 to mediate the NF-κB and p38 MAP kinase/MAPKAP-2 responses to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 2774–2786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Niu J., Shi Y., Iwai K., Wu Z.-H. (2011) LUBAC regulates NF-κB activation upon genotoxic stress by promoting linear ubiquitination of NEMO. EMBO J. 30, 3741–3753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruland J. (2011) Return to homeostasis: downregulation of NF-κB responses. Nat. Immunol. 12, 709–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee M. H., Mabb A. M., Gill G. B., Yeh E. T., Miyamoto S. (2011) NF-κB induction of the SUMO protease SENP2: a negative feedback loop to attenuate cell survival response to genotoxic stress. Mol. Cell 43, 180–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niu J., Shi Y., Xue J., Miao R., Huang S., Wang T., Wu J., Fu M., Wu Z. H. (2013) USP10 inhibits genotoxic NF-κB activation by MCPIP1-facilitated deubiquitination of NEMO. EMBO J. 32, 3206–3219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pomerantz J. L., Baltimore D. (1999) NF-κB activation by a signaling complex containing TRAF2, TANK and TBK1, a novel IKK-related kinase. EMBO J. 18, 6694–6704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rothe M., Xiong J., Shu H. B., Williamson K., Goddard A., Goeddel D. V. (1996) I-TRAF is a novel TRAF-interacting protein that regulates TRAF-mediated signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8241–8246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheng G., Baltimore D. (1996) TANK, a co-inducer with TRAF2 of TNF- and CD 40L-mediated NF-κB activation. Genes Dev. 10, 963–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharma S., tenOever B. R., Grandvaux N., Zhou G. P., Lin R., Hiscott J. (2003) Triggering the interferon antiviral response through an IKK-related pathway. Science 300, 1148–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Häcker H., Redecke V., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Hsu L.-C., Wang G. G., Kamps M. P., Raz E., Wagner H., Häcker G., Mann M., Karin M. (2006) Specificity in Toll-like receptor signalling through distinct effector functions of TRAF3 and TRAF6. Nature 439, 204–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oganesyan G., Saha S. K., Guo B., He J. Q., Shahangian A., Zarnegar B., Perry A., Cheng G. (2006) Critical role of TRAF3 in the Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent antiviral response. Nature 439, 208–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kawagoe T., Takeuchi O., Takabatake Y., Kato H., Isaka Y., Tsujimura T., Akira S. (2009) TANK is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling and is critical for the prevention of autoimmune nephritis. Nat. Immunol. 10, 965–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maruyama K., Kawagoe T., Kondo T., Akira S., Takeuchi O. (2012) TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator (TANK) is a negative regulator of osteoclastogenesis and bone formation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29114–29124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guo B., Cheng G. (2007) Modulation of the interferon antiviral response by the TBK1/IKKi adaptor protein TANK. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11817–11826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Wright J., Agarwala V., Scott D. A., Zhang F. (2013) Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu Z. H., Miyamoto S. (2008) Induction of a pro-apoptotic ATM-NF-κB pathway and its repression by ATR in response to replication stress. EMBO J. 27, 1963–1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tan G., Niu J., Shi Y., Ouyang H., Wu Z.-H. (2012) NF-κB-dependent microRNA-125b upregulation promotes cell survival by targeting p38α upon UV radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33036–33047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P. D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L. A., Zhang F. (2013) Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clark K., Peggie M., Plater L., Sorcek R. J., Young E. R., Madwed J. B., Hough J., McIver E. G., Cohen P. (2011) Novel cross-talk within the IKK family controls innate immunity. Biochem. J. 434, 93–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clark K., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Cohen P. (2011) The TRAF-associated protein TANK facilitates cross-talk within the IκB kinase family during Toll-like receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17093–17098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chariot A., Leonardi A., Muller J., Bonif M., Brown K., Siebenlist U. (2002) Association of the adaptor TANK with the I κ B kinase (IKK) regulator NEMO connects IKK complexes with IKK epsilon and TBK1 kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37029–37036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rual J. F., Venkatesan K., Hao T., Hirozane-Kishikawa T., Dricot A., Li N., Berriz G. F., Gibbons F. D., Dreze M., Ayivi-Guedehoussou N., Klitgord N., Simon C., Boxem M., Milstein S., Rosenberg J., Goldberg D. S., Zhang L. V., Wong S. L., Franklin G., Li S., Albala J. S., Lim J., Fraughton C., Llamosas E., Cevik S., Bex C., Lamesch P., Sikorski R. S., Vandenhaute J., Zoghbi H. Y., Smolyar A., Bosak S., Sequerra R., Doucette-Stamm L., Cusick M. E., Hill D. E., Roth F. P., Vidal M. (2005) Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature 437, 1173–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liang J., Saad Y., Lei T., Wang J., Qi D., Yang Q., Kolattukudy P. E., Fu M. (2010) MCP-induced protein 1 deubiquitinates TRAF proteins and negatively regulates JNK and NF-κB signaling. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2959–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu Z. H., Shi Y. (2013) When ubiquitin meets NF-κB: a trove for anti-cancer drug development. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 3263–3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keusekotten K., Elliott P. R., Glockner L., Fiil B. K., Damgaard R. B., Kulathu Y., Wauer T., Hospenthal M. K., Gyrd-Hansen M., Krappmann D., Hofmann K., Komander D. (2013) OTULIN antagonizes LUBAC signaling by specifically hydrolyzing Met1-linked polyubiquitin. Cell 153, 1312–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rivkin E., Almeida S. M., Ceccarelli D. F., Juang Y.-C., MacLean T. A., Srikumar T., Huang H., Dunham W. H., Fukumura R., Xie G., Gondo Y., Raught B., Gingras A.-C., Sicheri F., Cordes S. P. (2013) The linear ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinase gumby regulates angiogenesis. Nature 498, 318–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Komander D., Reyes-Turcu F., Licchesi J. D., Odenwaelder P., Wilkinson K. D., Barford D. (2009) Molecular discrimination of structurally equivalent Lys 63-linked and linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO Rep. 10, 466–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takiuchi T., Nakagawa T., Tamiya H., Fujita H., Sasaki Y., Saeki Y., Takeda H., Sawasaki T., Buchberger A., Kimura T., Iwai K. (2014) Suppression of LUBAC-mediated linear ubiquitination by a specific interaction between LUBAC and the deubiquitinases CYLD and OTULIN. Genes Cells 19, 254–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yuan J., Luo K., Zhang L., Cheville J. C., Lou Z. (2010) USP10 regulates p53 localization and stability by deubiquitinating p53. Cell 140, 384–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu J., Xia H., Kim M., Xu L., Li Y., Zhang L., Cai Y., Norberg H. V., Zhang T., Furuya T., Jin M., Zhu Z., Wang H., Yu J., Li Y., Hao Y., Choi A., Ke H., Ma D., Yuan J. (2011) Beclin1 controls the levels of p53 by regulating the deubiquitination activity of USP10 and USP13. Cell 147, 223–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin Z., Yang H., Tan C., Li J., Liu Z., Quan Q., Kong S., Ye J., Gao B., Fang D. (2013) USP10 Antagonizes c-Myc transcriptional activation through SIRT6 stabilization to suppress tumor formation. Cell Rep. 5, 1639–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]