Background: A protein-only ribonuclease P (PRORP) has been recently discovered.

Results: PRORP activity has a single ionization (pKa ∼ 8.7) important for catalysis and a cooperative dependence on Mg2+ (nH = 2).

Conclusion: PRORP uses catalytic strategies similar to RNA-dependent RNase P.

Significance: These results provide evidence for the mechanistic convergence of two different enzymatic macromolecules (RNA and protein) that perform the same biological function.

Keywords: endoribonuclease, magnesium, precursor tRNA (pre-tRNA), ribonuclease P (RNase P), ribozyme, NYN, PRORP, metal dependence, metallonuclease

Abstract

Ribonuclease P (RNase P) is an endonuclease that catalyzes the essential removal of the 5′ end of tRNA precursors. Until recently, all identified RNase P enzymes were a ribonucleoprotein with a conserved catalytic RNA component. However, the discovery of protein-only RNase P (PRORP) shifted this paradigm, affording a unique opportunity to compare mechanistic strategies used by naturally evolved protein and RNA-based enzymes that catalyze the same reaction. Here we investigate the enzymatic mechanism of pre-tRNA hydrolysis catalyzed by the NYN (Nedd4-BP1, YacP nuclease) metallonuclease of Arabidopsis thaliana, PRORP1. Multiple and single turnover kinetic data support a mechanism where a step at or before chemistry is rate-limiting and provide a kinetic framework to interpret the results of metal alteration, mutations, and pH dependence. Catalytic activity has a cooperative dependence on the magnesium concentration (nH = 2) under kcat/Km conditions, suggesting that PRORP1 catalysis is optimal with at least two active site metal ions, consistent with the crystal structure. Metal rescue of Asp-to-Ala mutations identified two aspartates important for enhancing metal ion affinity. The single turnover pH dependence of pre-tRNA cleavage revealed a single ionization (pKa ∼ 8.7) important for catalysis, consistent with deprotonation of a metal-bound water nucleophile. The pH and metal dependence mirrors that observed for the RNA-based RNase P, suggesting similar catalytic mechanisms. Thus, despite different macromolecular composition, the RNA and protein-based RNase P act as dynamic scaffolds for the binding and positioning of magnesium ions to catalyze phosphodiester bond hydrolysis.

Introduction

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are transcribed as precursor tRNAs (pre-tRNAs)2 with extra nucleotides flanking the 5′ (leader) and 3′ (trailer) ends. Removal of these extra sequences is essential for tRNA function, making the enzymes that catalyze pre-tRNA end maturation essential. Ribonuclease P (RNase P) catalyzes the formation of the mature 5′ end of pre-tRNA and has remarkable diversity in subunit and macromolecular composition throughout domains and even within the same species (1). RNA-based RNase P (ribozyme) contains varying numbers of protein subunits ranging from one in bacteria to at least 10 in eukaryotes (2).

Some eukaryotic species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, are seemingly devoid of an RNA-based RNase P and instead encode a protein-only RNase P (PRORP) (3). Mammals, including humans, use both RNA- and protein-based RNase P to catalyze pre-tRNA maturation (4). This redundancy in humans can be partly explained by differential localization; PRORP (or MRPP3) functions in the mitochondria, whereas the RNA-based RNase P functions in the nucleus (4, 5). Knockdown of human PRORP results in accumulation of mitochondrial pre-tRNA in HeLa cells, and knock-out of the homologous PRORP1 in A. thaliana is lethal (3, 4, 6). Thus, PRORP enzymes play an essential role in mitochondria.

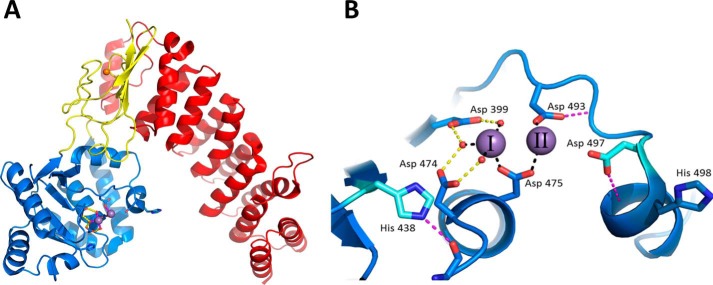

In A. thaliana, three PRORPs are encoded within the nuclear genome (PRORP1, -2, and -3). PRORP2 and PRORP3 co-localize to the nucleus, whereas PRORP1 functions within both the mitochondria and chloroplasts (6). PRORP is homologous to the nuclease component of the human mitochondrial RNase P (MRPP3/human PRORP). The structure of A. thaliana PRORP1 revealed three domains: a Nedd4-BP1, YacP nuclease (NYN) metallonuclease domain, a central structural zinc-binding domain, and a pentatricopeptide repeat domain involved in pre-tRNA binding (Fig. 1A) (7). The NYN domain is a novel metallonuclease domain sharing structural homology to the PIN (PilT N terminus) and flap nuclease families (8). NYN domains have a relatively exposed active site and contain four conserved aspartates as compared with the flap nuclease family that has six conserved aspartates (7, 8). Despite having only four conserved potential metal ligands within its active site, the crystal structure visualized the binding of two manganese ions to the NYN domain of PRORP1 in positions similar to those observed in the flap nuclease family (7, 9). These similarities led to the proposal that NYN metallonuclease domains catalyze phosphodiester bond hydrolysis using a classical two-metal ion mechanism (6, 7, 10). In this mechanism, metal I is proposed to activate a coordinated water molecule for nucleophilic attack, both metals are proposed to stabilize the negative charge buildup in the transition state, and metal II is proposed to stabilize the developing charge on the 3′-oxyanion leaving group (10).

FIGURE 1.

Crystal structure and active site of PRORP1. A, A. thaliana PRORP1 (Protein Data Bank code 4G24) contains three domains: pentatricopeptide repeat domain in red, central domain in yellow, and NYN-metallonuclease domain in blue. B, active site of PRORP1 with two bound Mn2+ ions (I and II). Completely conserved residues are represented as blue sticks (Asp-399, Asp-493, Asp-474, Asp-475, and His-498). Partially conserved residues are in cyan (His-438 and Asp-497). Potential hydrogen bonds are depicted by magenta dashes (with other amino acids) and yellow dashes (with metal-bound waters). Black dashes represent proposed inner sphere coordination of the metal ions. In the crystal structure, metal II has a lower occupancy (∼80%), and the metal-bound waters are not visible (7).

Here we investigate the catalytic mechanism of PRORP1 by examining the metal and pH dependence of pre-tRNA cleavage. These data provide evidence for a two-metal ion mechanism and identify a single ionization that is important for catalysis. The pH dependence is consistent with deprotonation of a catalytic metal-bound water and provides no evidence for an amino acid side chain acting as a general acid to protonate the leaving group. Alanine mutations of the conserved aspartate residues that coordinate metal ions significantly reduce single turnover activity as observed previously (6, 7). However, addition of high concentrations of Mg2+ can partially rescue the activity of the D474A and D475A mutant enzymes, indicating that these residues are important for enhancing metal ion affinity. These findings provide insight into the enzymatic mechanism and metal binding properties of PRORP1 that can be extended to the NYN metallonuclease domains found throughout Eukaryota. Furthermore, the mechanism of PRORP1 has important similarities to the RNA-dependent RNase P.

Experimental Procedures

Enzyme Preparation

A truncation of PRORP1 lacking the N-terminal 76 amino acids, encompassing the mitochondrial localization sequence, was used in this study. PRORP1 WT and mutants were purified as described previously (7). Enzyme concentration was determined by absorbance using an extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 84,630 m−1 cm−1. Purified enzymes were aliquoted, flash frozen, and stored at −80 °C in 20 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 100 mm NaCl, and 1 mm TCEP.

Pre-tRNA Preparation

The A. thaliana pre-tRNA was produced by runoff transcription from a linearized plasmid containing a T7 promoter, a 5:1 (leader nt length:discriminator base) mitochondrial pre-tRNACys gene, and a 3′-BstNI restriction site. The Bacillus subtilis pre-tRNAAsp was transcribed from a PCR product containing a T7 promoter with a 5-nt leader and a discriminator base (1-nt trailer) using a plasmid encoding B. subtilis pre-tRNAAsp with a 5-nucleotide leader and GCCA trailer as the template (11). Transcription reactions were performed in the presence of GMPS and the 5′-phosphorothioate was incubated with 5-(iodoacetamido)fluorescein to fluorescently label the 5′ end (12). Substrates were purified on 12% urea-polyacrylamide gels, crush-soaked to elute, then washed, and concentrated. The concentration of pre-tRNA substrates was calculated by absorbance using extinction coefficients of 674,390 and 685,000 m−1 cm−1 at 260 nm for A. thaliana and B. subtilis pre-tRNA, respectively. Labeling efficiency was assessed by fluorescein absorbance at 492 nm using an extinction coefficient of 78,000 m−1 cm−1. Samples were stored at −20 or −80 °C in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4. Proposed tRNA secondary structures were generated with tRNAscan-SE 1.21 (13).

Enzyme Assays

Standard reaction conditions were 30 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm TCEP, and 1 mm MgCl2 at 25 °C. Pre-tRNA substrates were denatured by heating at 95 °C for 1 min in Milli-Q H2O and then refolded by incubating at 25 °C for 15 min, adding reaction buffer, and incubating at 25 °C for at least 15 min before use. For single turnover reactions, the enzyme and pre-tRNA concentrations were 5 μm and 20 nm, respectively, unless otherwise noted. Single turnover reactions were initiated by addition of enzyme (5 μm) and quenched at specified times with an equal volume of 100 mm EDTA, 6 m urea, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol, and 2 μg/μl yeast tRNA. The labeled 5′ leader product was separated from pre-tRNA by 20 or 22.5% urea-PAGE. Gels were visualized using a Typhoon 9410 scanner, and the fraction product was quantified using ImageQuant 5.2 software. The observed single turnover rate constant was calculated from a fit of a first order exponential equation to the data using KaleidaGraph fitting software. The kobs was not significantly dependent on the PRORP1 concentration (2 and 5 μm), confirming that the enzyme was saturating (kmax conditions).

Multiple turnover reactions were performed in black Costar half-area 96-well plates using a fluorescence polarization (FP) assay (as described in Ref. 14). Standard reaction conditions were used with an enzyme concentration of 20 nm. The concentration of fluorescently labeled pre-tRNA was held constant at 40 nm in the reactions, whereas the concentration of unlabeled pre-tRNA substrate was varied. The ratio of labeled to unlabeled substrate did not alter the measured initial rates. Initial rates were calculated from the linear decrease in fluorescence anisotropy (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 535 nm). The steady state kinetic parameters were calculated from a fit of the Michaelis-Menten (15) equation to the concentration dependence of the initial rates using KaleidaGraph.

Metal Dependence

The metal dependence of cleavage of B. subtilis pre-tRNA was measured under multiple turnover conditions using the FP assay. The pre-tRNA concentration dependence of the initial velocity was measured at seven MgCl2 concentrations with the ionic strength held constant by adjusting the NaCl concentration (μ = 200 mm taking only the NaCl and MgCl2 concentrations into account). The metal dependence of PRORP-catalyzed cleavage of A. thaliana pre-tRNACys was measured at two substrate concentrations, 250 nm and 5 μm, mimicking kcat/Km and kcat conditions, respectively. Metal dependence reactions were similarly performed in the presence of 1 mm CaCl2. Equation 1 was fit to the Mg2+ dependence of the apparent steady state kinetic parameters where k represents the apparent kcat or kcat/Km, kMg represents the maximal rate constant (kcatMg or (kcat/Km)Mg) at saturating Mg2+, and KmMg is the concentration of Mg2+ at which kMg is half-maximal.

|

Metal Dependence of Mutants

5 μm WT, D399A, D474A, D475A, or D493A PRORP were incubated with 20 nm B. subtilis fluorescein-pre-tRNAAsp in 50 mm MTA buffer (see “pH Dependence” for description of MTA buffer), pH 8.0 with 1–20 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm TCEP. For WT, the NaCl concentration was adjusted to correct for ionic strength, whereas 100 mm NaCl was used to assay the mutant enzymes. These single turnover reactions were quenched at 2 h with an equal volume of 100 mm EDTA, 6 m urea, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol, and 2 μg/μl yeast tRNA. The fraction product was determined using 22.5% urea-PAGE.

pH Dependence

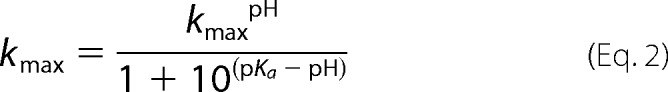

Reactions were performed under single turnover conditions (5 μm PRORP and 20 nm pre-tRNA) in a three-component buffer system (MTA buffer): 50 mm MES (pKa 6.15), Tris (pKa 8), and 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (pKa 9.7) (16, 17). Reactions also included 1 mm TCEP, 1 mm MgCl2, and NaCl to maintain ionic strength (μ = 240 ± 10 mm). The pH range assayed was 6.0–9.75. Doubling the concentration of PRORP to 10 μm at pH 6.5 and 8.0 increased the observed rate constant <20%, indicating that the enzyme concentration was saturating. The rate constants measured in MTA buffer were within 20% of assays performed in 50 mm PIPES, pH 6.95; Tris, pH 8.0; and CHES, pH 9.5. Reactions performed with A. thaliana pre-tRNA at and above pH 8.5 displayed biphasic kinetics possibly due to misfolded substrate (18). The observed rate constant for the first phase (largest amplitude) was used in the pH profile. Reactions at pH 9.5 and 9.75 for cleavage of B. subtilis pre-tRNA were performed using a quench-flow apparatus. A single ionization model (Equation 2) was fit to the pH dependence of the single turnover reaction where kmax is the observed rate constant at a given pH, kmaxpH is the pH-independent rate constant, and the pKa is the pH when the activity is half-maximal.

|

Single turnover (STO) reactions performed in the presence of various divalent ions contained 8 μm PRORP1, 50 mm MTA buffer at pH 6.5, 10 mm divalent metal, 1 mm TCEP, 250 μm hexamminecobalt(III) chloride, 165 mm NaCl, and 30 nm B. subtilis pre-tRNA. kmax was measured under various metal concentrations (1, 5, 10, and 20 mm) to ensure metal saturation and lack of inhibition.

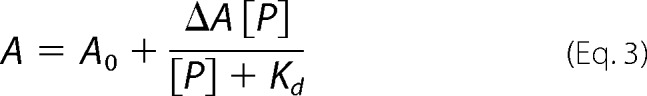

Anisotropy Binding Assays

Binding assays were performed as described previously (7). Briefly, the concentration of fluorescein labeled pre-tRNA was maintained at 20 nm, whereas the concentration of PRORP was varied (0.005–5 μm). Binding experiments were performed in 20 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm TCEP, and 1 mm CaCl2 in a 96-well plate format. Fluorescence anisotropy was measured at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm (14). PRORP1 is not active in CaCl2 (7). Equation 3 was fit to the dependence of the anisotropy on the protein concentration where A is the observed anisotropy, A0 is the initial anisotropy, ΔA is the total change in anisotropy, P is the concentration of PRORP, and Kd is the apparent dissociation constant.

|

Results

Single and Multiple Turnover Kinetics of PRORP1-catalyzed Pre-tRNA Cleavage

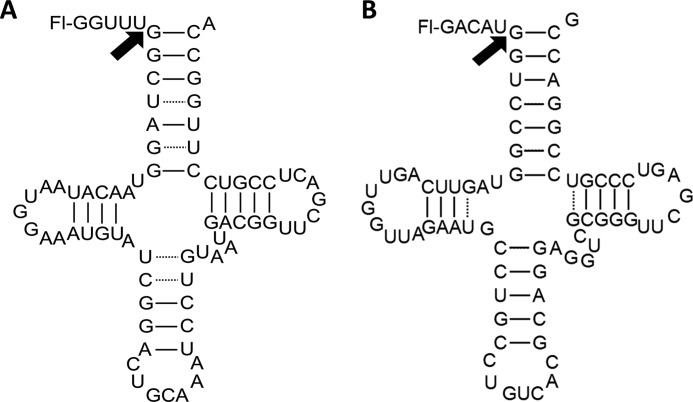

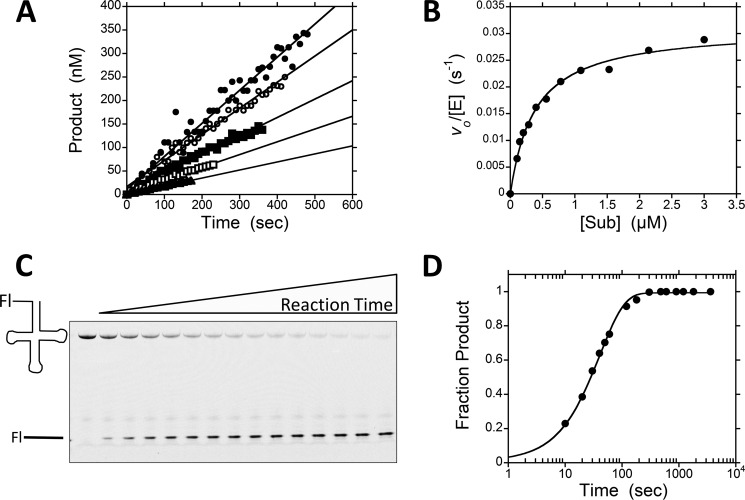

We measured the STO and multiple turnover (MTO) kinetics of pre-tRNA cleavage catalyzed by PRORP1 to establish a kinetic framework to evaluate the effects of pH, metal ion concentration, and mutations. Cleavage reactions were carried out using two substrates, A. thaliana mitochondrial pre-tRNACys (A. thaliana pre-tRNA) and B. subtilis pre-tRNAAsp (B. subtilis pre-tRNA), a bacterial substrate extensively used to analyze the reactivity of the RNA-based RNase P (Fig. 2). These substrates were 5′ end-labeled with fluorescein and contain a 5-nt leader and a 3′ discriminator base. For MTO reactions, we used a recently developed real time FP assay to monitor the dependence of PRORP1-catalyzed pre-tRNA cleavage on the substrate concentration (14). Representative MTO data from the FP assay are shown in Fig. 3A; the value of kcat/Km is ∼ 1 × 105 m−1 s−1, which is ∼35-fold slower than the reaction catalyzed by B. subtilis RNA-dependent RNase P (19), and the value of kcat is 0.03–0.06 s−1 (Table 1). Cleavage of pre-tRNA catalyzed by PRORP1 under STO conditions was too fast to measure using the FP assay. Therefore, these reactions were performed in a stopped assay format at saturating enzyme concentrations, and product formation was analyzed by urea-PAGE (Fig. 3C) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A single exponential equation was fit to the data (Fig. 3D). The values of the STO rate constant at saturating enzyme (kmax), 0.03–0.04 s−1, are comparable with the multiple turnover parameter at saturating substrate (kcat), suggesting that a step at or before cleavage is rate-limiting for both substrates under these conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Proposed secondary structures of the pre-tRNA substrates used in this study. Both substrates are labeled at the 5′ end with fluorescein (Fl) and contain 5-nt leaders and a discriminator base at the 3′ end. The cleavage sites are identified with an arrow. A, A. thaliana mitochondrial pre-tRNACys. B, B. subtilis pre-tRNAAsp.

FIGURE 3.

Representative multiple and single turnover data of PRORP1-catalyzed pre-tRNA cleavage. A, representative initial rates of product formation using the FP assay under multiple turnover conditions with varying concentrations of B. subtilis pre-tRNA (circles, 1 μm; open circles, 0.5 μm; squares, 0.3 μm; open squares, 0.15 μm; triangles, 0.06 μm) and 20 nm PRORP1 in 30 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm TCEP, and 1 mm MgCl2 at 25 °C (standard reaction conditions). B, dependence of the initial velocities, normalized by the PRORP1 concentration, on the substrate (Sub) concentration. The Michaelis-Menten equation was fit to the data. C, representative fluorescence scan of a urea 20% polyacrylamide gel of a single turnover assay (0–60 min) containing 5 μm PRORP1 and 20 nm B. subtilis pre-tRNA under standard reaction conditions. D, the gel was quantified, and the fraction product was calculated at each time point. A nonlinear regression curve of a single exponential fit to the data is shown. Kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1. Fl, fluorescein.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters for PRORP1-catalyzed A. thaliana pre-tRNA and B. subtilis pre-tRNA cleavage

Reactions were measured at 25 °C in 30 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm TCEP, and 1 mm MgCl2 as described in the legend of Fig. 3. Values reported reflect the mean of two independent experiments with the error reported as the standard deviation.

| Multiple turnovera |

Single turnover,b kmax | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-tRNA | Km | kcat | kcat/Km | |

| nm | s−1 | m−1 s−1 | s−1 | |

| A. thaliana | 630 ± 60 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 9.8 ± 1.0 × 104 | 0.04 ± 0.003 |

| B. subtilis | 350 ± 50 | 0.03 ± 0.003 | 1.0 ± 0.2 × 105 | 0.03 ± 0.003 |

a Measured using the FP assay with 20 nm PRORP and 0.06–3 μm pre-tRNA.

b Measured using a stopped assay with 5 μm PRORP1 and 20 nm pre-tRNA.

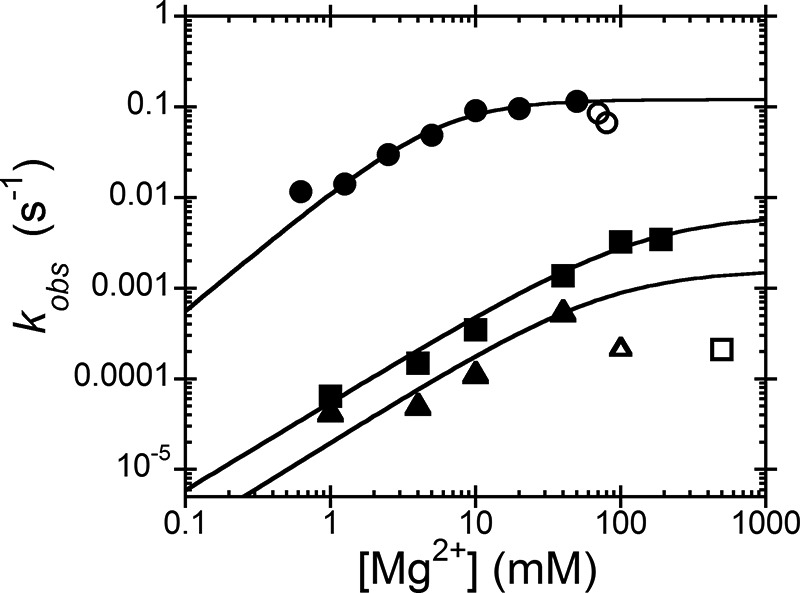

PRORP1 Magnesium Dependence

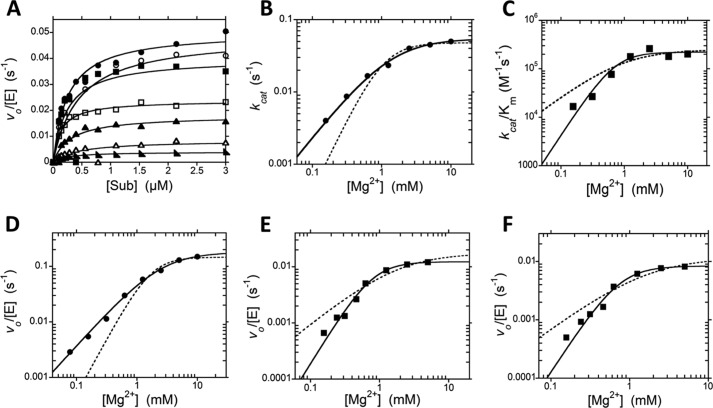

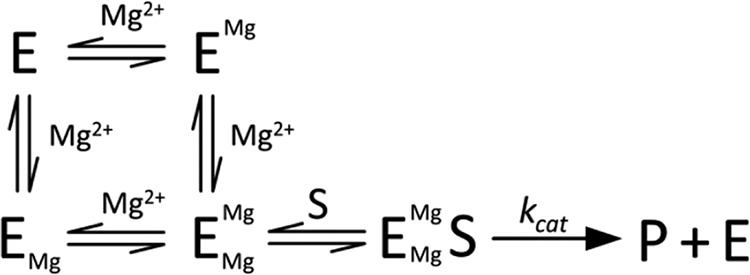

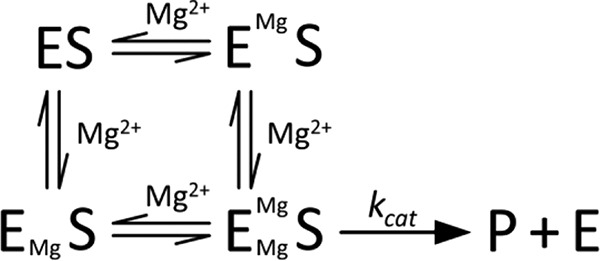

The crystal structure of PRORP1 in the presence of Mn2+ revealed two metal ion binding sites within the active site (Fig. 1B) (7). Based on this observation and the similarity of the NYN domain of PRORP1 to other nucleases, it has been proposed that PRORP enzymes use a two-metal ion mechanism for catalyzing phosphodiester bond hydrolysis (6, 7). To test this hypothesis, we measured the magnesium dependence of the steady state kinetics for cleavage of B. subtilis pre-tRNA catalyzed by PRORP1 (Fig. 4A). The measured kcat values show a hyperbolic dependence on the Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 4B). Fitting Equation 1 to these data yielded a Hill coefficient (nH) of 1.2 ± 0.2, a kcatMg of 0.06 ± 0.01 s−1, and a KmMg(kcat) of 1.4 ± 0.3 mm (Fig. 4B, solid line), indicating that no cooperativity is observed. The dashed line in Fig. 4B shows that a fit with nH = 2 does not describe the data. The value kcatMg reflects the maximal turnover number at saturating Mg2+ concentrations, and KmMg(kcat) represents the concentration of Mg2+ at which the rate is half of kcatMg. In contrast, the apparent kcat/Km values show a cooperative dependence on Mg2+ concentration with an nH value of 2.0 ± 0.6, resulting in a maximal value for kcat/Km at saturating Mg2+ ((kcat/Km)Mg) of 2.2 ± 0.3 × 105 m−1 s−1 and KmMg(kcat/Km) of 510 ± 270 μm (Fig. 4C). To determine whether these effects are substrate-specific, we also examined the Mg2+ dependence of the A. thaliana pre-tRNA at a subsaturating substrate concentration (250 nm) reflecting kcat/Km conditions and a saturating substrate concentration (5 μm) reflecting kcat conditions. The magnesium dependence of the PRORP1-catalyzed cleavage of the A. thaliana pre-tRNA substrate mirrors that observed for the B. subtilis pre-tRNA substrate; a cooperative dependence on Mg2+ concentration was observed under kcat/Km conditions (Fig. 4E) but disappeared under saturating substrate (kcat) conditions (Fig. 4D). Finally, to test whether the magnesium cooperativity observed under kcat/Km conditions is due to stabilization of the structure of pre-tRNA, we repeated these activity measurements in the presence of 1 mm CaCl2. Calcium stabilizes tRNA structure (20) but does not activate PRORP1 catalysis (7). However, we still observed an nH of 2.1 ± 0.2 for the Mg2+ dependence of kcat/Km in the presence of 1 mm CaCl2 (Fig. 4F). Potential models for the Mg2+ dependence under kcat/Km conditions and kcat conditions are represented in Schemes 1 and 2, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Mg2+ dependence of multiple turnover reactions catalyzed by PRORP1. Data in plots A–C were collected with the B. subtilis pre-tRNA substrate (Sub). A, dependence of PRORP1-catalyzed cleavage on the concentration of B. subtilis pre-tRNA and varying concentrations of Mg2+ (10 mm, circles; 5 mm, open circles; 2.5 mm, squares; 1.25 mm, open squares; 0.63 mm, triangles; 0.31 mm, open triangles; 0.16 mm, right triangles). Reactions were performed at 25 °C, in MOPS, pH 7.8 and 1 mm TCEP with varying concentrations of MgCl2 and NaCl to maintain ionic strength. The Michaelis-Menten equation is fit to the data. The apparent steady state kinetic parameters are plotted in B and C. B, dependence of kcat on the Mg2+ concentration. The solid line shows a fit of Equation 1 to the data yielding kcatMg = 0.06 ± 0.01 s−1, KmMg(kcat) = 1.4 ± 0.3 mm, and nH = 1.2 ± 0.2. The dotted line simulates data with a Hill coefficient of 2. C, dependence of kcat/Km on Mg2+ concentration. The solid line shows a weighted fit of Equation 1 to the data yielding kcat/KmMg = 2.2 ± 0.3 × 105 m−1 s−1, KmMg(kcat/Km) = 510 ± 270 μm, and nH = 2.0 ± 0.6. The dotted line simulates data with a Hill coefficient of 1. Data in plots D–F were collected with the A. thaliana pre-tRNA substrate. D, dependence of the initial velocity on Mg2+ at saturating substrate (5 μm). The solid line shows a fit of Equation 1 to the data yielding kcatMg = 0.18 ± 0.01 s−1, KmMg(kcat) = 3.0 ± 0.3 mm, and nH = 1.2 ± 0.1. The dotted line simulates data with a Hill coefficient of 2. E, dependence of the initial velocity on the Mg2+ concentration using a subsaturating substrate concentration (250 nm). The solid line shows a fit of Equation 1 to the data yielding a maximal rate constant of 0.01 ± 0.001 s−1 (4.7 × 104 m−1 s−1), KmMg(kcat/Km) = 640 ± 100 μm, and nH = 2.0 ± 0.2. The dotted line simulates data with a Hill coefficient of 1. F, dependence of the initial velocity on the Mg2+ concentration using a subsaturating substrate concentration (250 nm) in the presence of 1 mm CaCl2. The solid line shows a fit of Equation 1 to the data yielding a maximal rate constant of 0.008 ± 0.001 s−1 (3.3 × 104 m−1 s−1), KmMg(kcat/Km) = 560 ± 110 μm, and nH = 2.1 ± 0.2. The dotted line simulates data with a Hill coefficient of 1.

SCHEME 1.

Mg2+ dependence under kcat/Km conditions.

SCHEME 2.

Mg2+ dependence under kcat conditions.

Taken together, these magnesium-dependent data indicate that PRORP1 requires at least two Mg2+ ions for optimal catalysis and that the Mg2+ ions bind cooperatively to PRORP1. Additionally, because Mg2+ cooperativity was only observed under kcat/Km conditions, these data suggest that Mg2+ binding to PRORP1 is coupled to pre-tRNA binding.

Metal Dependence of Aspartate to Alanine Mutants

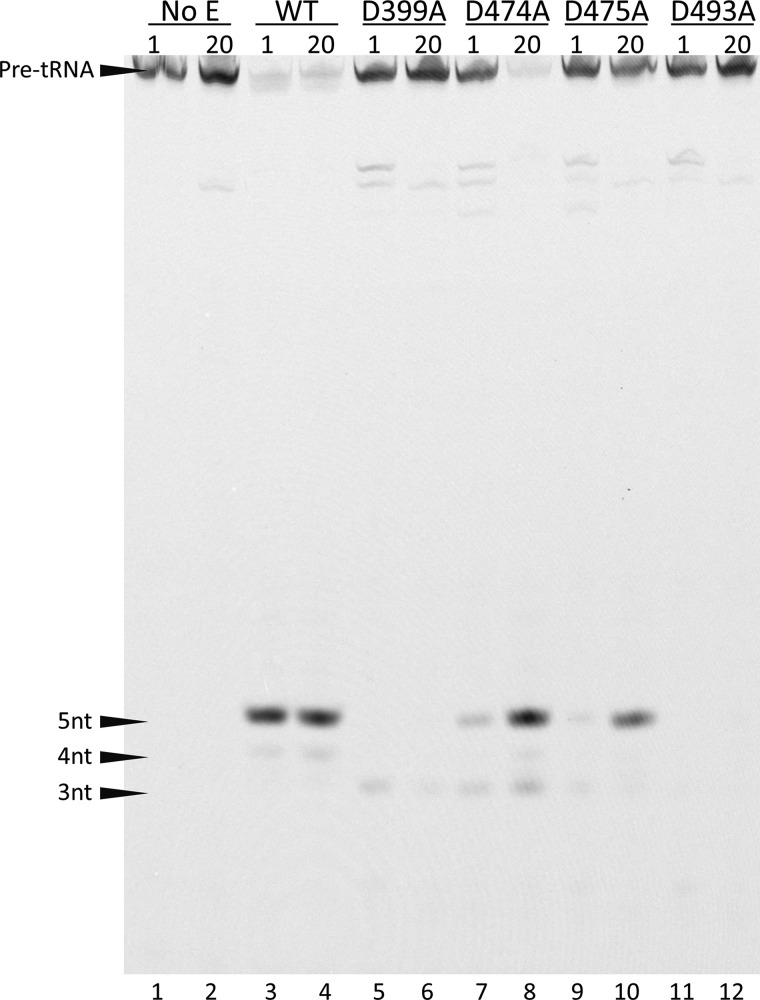

The PRORP1 crystal structure also revealed amino acid residues that interact with the active site metal ions (7). Two manganese ions are observed bound to the active site interacting with four conserved aspartate residues (D399A, D474A, D475A, and D493A) through both inner and outer sphere interactions (Fig. 1B). Mutation of any one of these conserved aspartate residues to alanine significantly reduces activity (7); no product formation is observed after a 30-min incubation under standard STO assay conditions (1 mm MgCl2). To evaluate whether the activity of these mutants could be enhanced by higher Mg2+ concentrations, we compared the STO cleavage activity at 1 and 20 mm Mg2+ (Fig. 5). The activity of the D474A and D475A increased significantly at the higher magnesium concentration (Fig. 5). However, no increase in activity was observed with the D399A and D493A mutants (even after incubation at 50 mm Mg2+ for 2 h; data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

The activity of the D474A and D475A mutants increases at high concentrations of Mg2+. 20 nm B. subtilis pre-tRNA was incubated with a 5 μm concentration of each PRORP1 variant at 25 °C with either 1 or 20 mm MgCl2 in 50 mm MTA buffer at pH 8.0, 1 mm TCEP, and NaCl adjusted to maintain ionic strength. Reactions were quenched at 2 h and resolved by 22.5% denaturing PAGE. Less intense bands, representing miscleaved products, are observed between the substrate and product bands and below the correct 5-nt product band (4- and 3-nt products).

We then measured the magnesium dependence of the activity of WT and the D474A and D475A mutants under STO conditions with saturating enzyme (Fig. 6). For WT, the observed rate constant shows a hyperbolic dependence on Mg2+ concentration, yielding kmaxMg = 0.12 ± 0.01 s−1, K1/2Mg = 10 ± 3.3 mm, and nH = 1.3 ± 0.3. High concentrations of Mg2+ inhibited both wild-type PRORP1 and the aspartate mutants (Fig. 6, open symbols), and these points were not included in the analysis of the data. For the mutants, the K1/2Mg value was estimated as >90 mm, and kmaxMg was ≥0.007 s−1 (D474A) and ≥0.002 s−1 (D475A), indicating that the value of K1/2Mg was increased at least 9-fold and the activity was decreased at least 17-fold as compared with WT (Table 2). The metal-dependent parameters measured for WT PRORP1 under STO conditions (K1/2Mg = 10 ± 3.3 mm and kmaxMg = 0.12 ± 0.01 s−1) were larger than the comparable values measured under MTO conditions (KmMg(kcat) = 1.4 ± 0.3 mm and kcatMg = 0.06 ± 0.01 s−1); this could potentially be a result of different assay conditions or a change in the rate-limiting step at high Mg2+ concentrations for MTO reactions. Nonetheless, these data indicate that one function of Asp-474 and Asp-475 is to enhance metal ion affinity; however, the decrease in activity suggests that these side chains also increase the reactivity of the metal ions, possibly by correct positioning. This proposal is supported by the observation that the D474A and D475A PRORP1 variants catalyze low amounts of miscleaved product (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 6.

Single turnover magnesium dependence of WT, D474A, and D475A PRORP1-catalyzed cleavage. Reactions were performed with 5 μm PRORP1 (WT, circles; D474A, squares; D475A, triangles) and 20 nm B. subtilis pre-tRNA as described in the legend of Fig. 5. Inhibition was observed at high concentrations of Mg2+, and these data were not included in the fit (shown as open symbols). Equation 1 was fit to the data, yielding kmaxMg = 0.12 ± 0.01 s−1, K1/2Mg = 10 ± 3.3 mm, and nH = 1.3 ± 0.3 for WT. The K1/2Mg and kmaxMg values for the D474A and D475A mutants were estimated as >90 mm and ≥0.007 and ≥0.002 s−1, respectively. Data are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Single turnover magnesium dependence of PRORP1 metal ligand mutants

pH Dependence

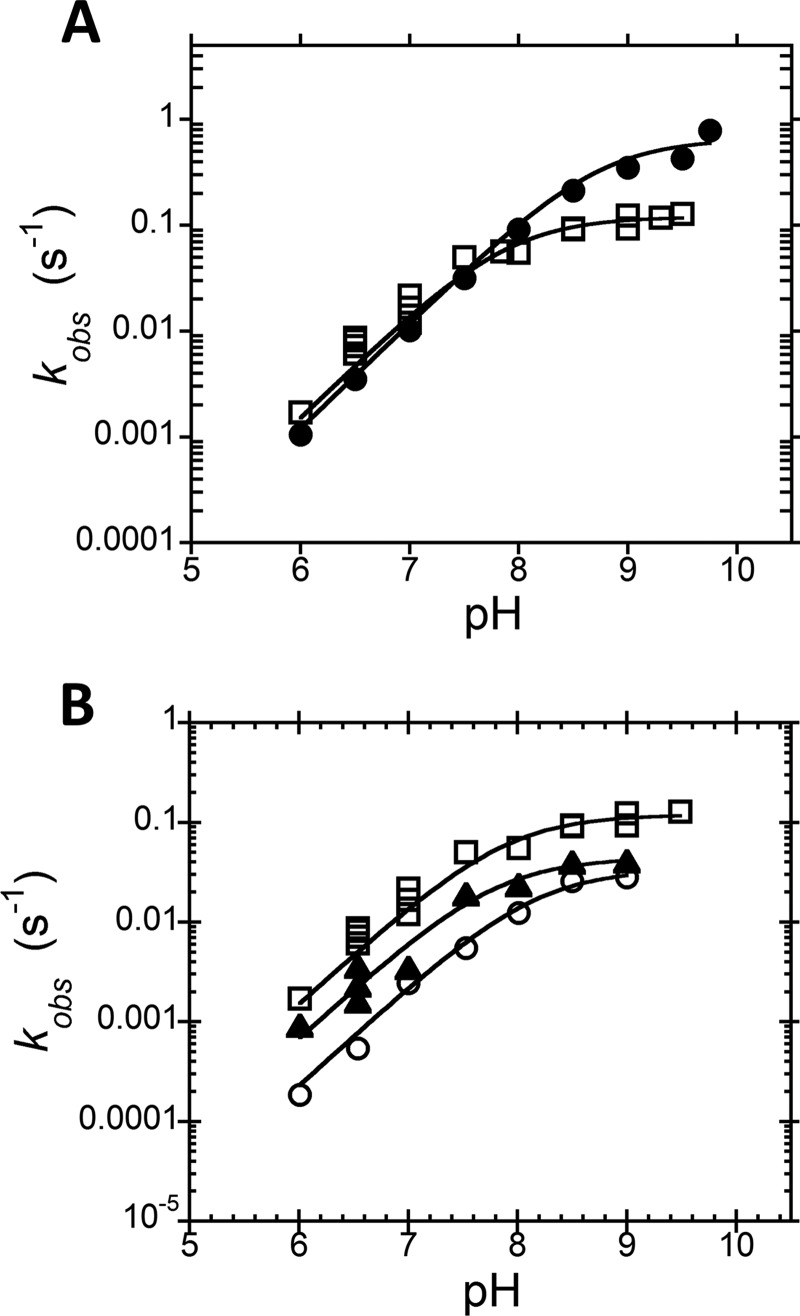

To provide further insight into the mechanism of PRORP-catalyzed phosphodiester bond hydrolysis, we measured the pH dependence of STO cleavage with both A. thaliana and B. subtilis pre-tRNA substrates. The kobs values for both substrates show a similar dependence on pH: a log-linear increase with increasing pH that becomes pH-independent under alkaline conditions (Fig. 7A). These data are well described by a single ionization that increases activity with pKa values of 7.9 ± 0.1 (A. thaliana pre-tRNA) and 8.7 ± 0.4 (B. subtilis pre-tRNA), suggesting that deprotonation of a single group enhances activity. The lack of an alkaline limb suggests that no protein side chain acts as a general acid.

FIGURE 7.

pH dependence of PRORP1-catalyzed cleavage of pre-tRNA under single turnover conditions. Single turnover reactions were carried out as described in the legend of Fig. 3 in a three-component buffer system (MTA buffer) with NaCl varied to maintain ionic strength, 5 μm enzyme, 20 nm substrate, 1 mm TCEP, and 1 mm MgCl2 at 25 °C. A, pH profile for cleavage of A. thaliana pre-tRNA (open squares) and B. subtilis pre-tRNA (circles) under STO conditions. Equation 2 was fit to the data with resulting pKa values of 7.9 ± 0.1 and 8.7 ± 0.4 and kmaxpH values of 0.12 ± 0.01 and 0.65 ± 0.08 s−1 for A. thaliana pre-tRNA and B. subtilis pre-tRNA, respectively. B, pH profile for H498Q- (triangles) and H438A (open circles)-catalyzed cleavage of A. thaliana pre-tRNA. WT (open squares) data are shown for comparison. Equation 2 was fit to the data with resulting pKa values of 8.2 ± 0.1 and 7.8 ± 0.1 and kmaxpH values of 0.03 ± 0.002 and 0.04 ± 0.003 s−1 for H498Q and H438A, respectively.

In addition to the conserved aspartate residues, the active site of PRORP1 contains two histidine side chains that are located ∼6 Å from the metal binding sites (Fig. 1B). His-498 is invariant, whereas His-438 is conserved in plants. To examine whether either of these histidine side chains plays a role in PRORP1 catalysis or pH dependence, we mutated His-498 and His-438 to alanine. Under the standard STO assay conditions, the H498A and H438A mutations reduced the observed rate constant to 5.0 ± 0.2 × 10−4 and 0.02 ± 0.001 s−1, representing an 80- and 2-fold decrease, respectively, as compared with WT (0.04 s−1; Table 1). However, the more conservative mutation of His-498 to glutamine (H498Q) decreased the STO rate constant only 4-fold compared with WT. Furthermore, a single ionization was observed in the pH dependence of the STO cleavage rate constants for both the H498Q and H438A mutants with pKa values of 8.2 ± 0.1 and 7.8 ± 0.1, respectively. These mutations decreased the value of kmaxpH to 0.03 ± 0.002 and 0.04 ± 0.003 s−1, respectively, representing an ∼3-fold decrease for both as compared with WT (Fig. 7B). These modest alterations in the activity and pKa values for the H438A and H498Q mutants are not consistent with a function as a general acid/base catalyst; mutagenesis of a general acid/base group typically decreases activity by ∼103–104 in hydrolytic reactions (21, 22).

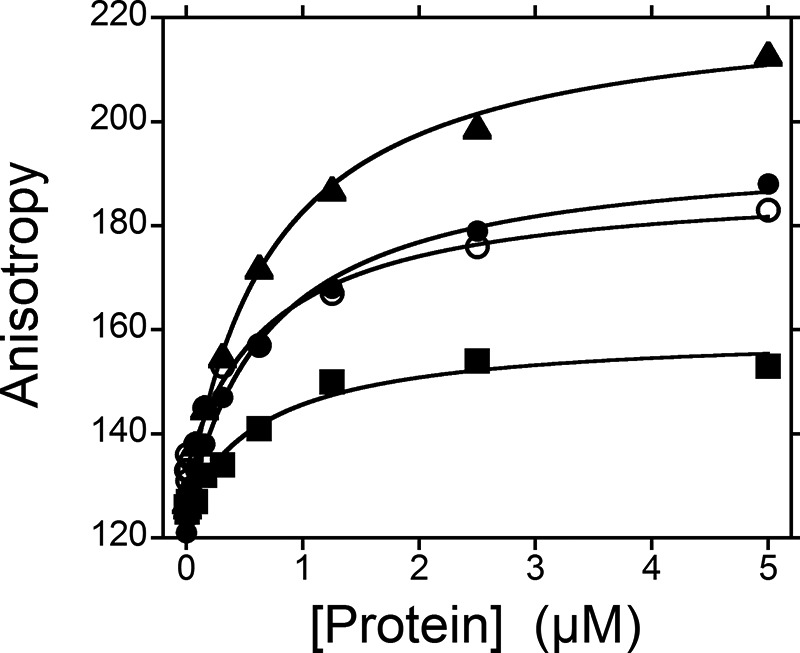

To determine whether the side chains of His-498 and His-438 enhance pre-tRNA binding, we measured the affinity of the variants for A. thaliana pre-tRNA using an anisotropy assay (Fig. 8). No significant change in binding affinity was observed for these histidine mutants in comparison with WT with dissociation constants of ∼700 nm. However, the end point anisotropy, reflecting the anisotropy of the ES complex, for the His-498 mutants varied significantly from the values measured for the WT and H438A enzymes. This result may indicate that the fluorescein and potentially the 5′ leader adopt a different position and/or conformation when bound to the His-498 mutants as compared with WT.

FIGURE 8.

Alanine mutations at His-498 and His-438 do not affect the PRORP1 binding affinity for A. thaliana pre-tRNA. The binding affinity for A. thaliana pre-tRNA of PRORP1 variants (WT, circles; H498A, squares; H498Q, triangles; and H438A, open circles) was measured by changes in the anisotropy of the fluorescein-labeled pre-tRNA substrate (20 nm) as the protein concentration varied in a 96-well plate format. Assays were performed in 20 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm TCEP, and 1 mm CaCl2 at 25 °C. The dissociation constants (Kd) for A. thaliana pre-tRNA were determined by fitting Equation 3 to the data, resulting in values of 700 ± 80, 680 ± 150, 710 ± 60, and 700 ± 120 nm for WT, H498A, H498Q, and H438A, respectively.

To examine whether the observed ionization reflects deprotonation of a metal-bound water, we measured the dependence of the activity on the identity of the metal ion. PRORP1 is activated by Mg2+, Mn2+, Co2+, and Ni2+ (but not Ca2+, Zn2+, or Cd2+ (7, 23)). We measured the rate constant for single turnover cleavage (kmax) at pH 6.5 with saturating concentrations of PRORP1 and metal (Co2+, Ni2+, Mn2+, or Mg2+). At pH 6.5, PRORP1 catalysis is within a log-linear region of the pH profile (Fig. 7). Furthermore, this pH is below the pKa values of the hydrated metals used (Co2+ = 9.65, Ni2+ = 10.0, Mn2+ = 10.46, and Mg = 11.4) (24, 25). Therefore, if the observed ionization reflects metal-water deprotonation, the value of kmax should correlate with the concentration of the metal-hydroxide, as indicated by the pKa value. Thus, the kmax values are predicted to follow the order Co2+ > Ni2+ > Mn2+ > Mg2+. The measured kmax values for PRORP1 are 0.417, 0.042, 0.004, and 0.021 s−1 for Co2+, Ni2+, Mn2+, and Mg2+, respectively, representing a trend of Co2+ > Ni2+ > Mg2+ > Mn2+. The faster reactivity observed in reactions with Mg2+ versus Mn2+ could be a result of PRORP1 evolving to specifically use Mg2+ ions; thus others factors such as differences in coordination geometries and preferred ligands of the metals used may explain this deviation (26). Excluding the Mg2+ data, log kmax decreased linearly with the value of the pKa of the hydrated metal (r = 0.998), consistent with the observed ionization in catalysis arising from a metal-bound water.

Discussion

A Minimal Kinetic Mechanism Reveals That Product Release Is Not Rate-limiting at Neutral pH

We have determined kinetic parameters for PRORP1-catalyzed pre-tRNA cleavage for a cognate A. thaliana substrate and a bacterial pre-tRNA substrate. Despite being from different organisms and domains of life, these substrates show similar kinetic parameters (Table 1). This is not surprising given that both of these tRNAs have conserved secondary and tertiary features (27). Furthermore, the similarity between the STO (kmax) and MTO (kcat) values suggests that a step observable under STO conditions is rate-limiting (e.g. a step at or before cleavage) and rules out product release as the rate-limiting step under MTO conditions. Consistent with this proposal, we did not observe burst kinetics in the steady state turnover with the substrates used in this study (Fig. 3A). This is in contrast to other RNase P enzymes that have been kinetically characterized. For instance, bacterial and yeast nuclear RNase P (RNA-based enzymes) are both limited by product dissociation and display burst kinetics under MTO conditions (28, 29). The standard assay condition (pH 7.8) is within the log-linear region of the pH dependence for PRORP1-catalyzed hydrolysis of B. subtilis pre-tRNA, suggesting that the cleavage step is rate-limiting.

Evidence for a Two-metal Ion Mechanism

Crystal structures of metallonucleases with metals bound in the active site have fuelled mechanistic proposals for one-, two-, and even three-metal ion mechanisms (30, 31). In fact, structures of PRORP1 in the presence of different divalent metal ions have revealed one (calcium) to two metal ions (manganese) bound within the active site. The metal dependence of PRORP1-catalyzed phosphodiester bond hydrolysis has a cooperativity of 2 for Mg2+ under kcat/Km conditions for both substrates, indicating that at least two metal ions activate catalysis. Addition of calcium does not abrogate the cooperativity, providing evidence that this effect is not due to stabilization of the pre-tRNA structure. Given these observations, we propose a model where the binding of one Mg2+ ion at the active site enhances the affinity of the second metal ion, leading to the cooperativity observed at low pre-tRNA concentrations (Scheme 1). Furthermore, the loss of cooperativity at saturating pre-tRNA concentration is most easily explained by enhancement of the affinity of one of the two metal ions by substrate. One model consistent with the data is that under kcat conditions an inactive ES complex with one tightly bound Mg2+ ion forms (EMgS) (Scheme 2). The enhanced metal binding affinity to the ES complex could be the result of either an indirect effect or the direct coordination of Mg2+ to a phosphodiester oxygen from the substrate. Similarly, the bacteriophage T5 Flap endonuclease, a member of the homologous flap nuclease family, shows no cooperativity for Mg2+ under kcat conditions, but a cooperativity of 2 is observed under kcat/Km conditions within the same Mg2+ concentration range tested for PRORP1 (31).

Asp-474 and Asp-475 Enhance the Active Site Metal Ion Affinity

Metal dependence measurements of aspartate-to-alanine mutations identified two side chains that enhance metal ion affinity by at least 9-fold. These mutations also decreased activity a maximum of 17- and 60-fold for the D474A and D475A mutants, respectively. These residues both lie on the end of an active site helix (Fig. 1B). Based on the crystal structure, Asp-475 makes an inner sphere bidentate interaction with both active site metal ions (Fig. 1B). A bidentate Asp ligand is very common among metallonucleases where it has proposed to orient the active site metal ions for optimal catalysis (32). However, in PRORP1, other groups besides Asp-475 must also help orient the metal ions, potentially including interactions with the substrate, because this mutant has significant activity at high concentrations of Mg2+. The activity of D399A and D493A mutants could not be rescued by high Mg2+ concentrations, suggesting that they serve other roles in addition to metal binding. For instance, Asp-399 makes a hydrogen bond with a metal-bound water that is positioned approximately between the two active site metals (Fig. 1B), suggesting that Asp-399 could position a metal-bound water for nucleophilic attack. In the other nonrescuable aspartate mutant, D493A, the Asp side chain forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone amide of methionine 495 (Fig. 1B); thus mutation of Asp-493 may deleteriously affect the active site architecture.

pH Dependence Reveals a Single Ionization Important for Catalysis

The pH dependence of PRORP1-catalyzed cleavage of pre-tRNA is consistent with ionization of a single group that enhances catalysis. However, for the A. thaliana pre-tRNA the values of both kmaxpH and pKa were decreased compared with the B. subtilis substrate. There are two models that could account for this. In the first model, the plateau in activity at high pH could result from a change in the rate-limiting step from chemistry at low pH to a pH-independent step, such as a conformational change, at high pH. In this case, the observed pKa does not reflect the thermodynamic ionization but rather a kinetic pKa due to a change in the rate-limiting step over the pH range tested. This mechanism leads to an underestimation of the pKa value as observed previously in the pH dependence of B. subtilis RNase P where the pKa reflects a change in the rate-limiting step (33). Alternatively, the difference in pKa values observed with the A. thaliana and B. subtilis pre-tRNAs could arise from differences in local active site environments in the pre-tRNA·PRORP complex, potentially arising from differences in nucleotide composition and/or the conformation of the bound pre-tRNA.

The pH-dependent data for cleavage of B. subtilis pre-tRNA indicate that ionization of a functional group with a pKa of 8.7 or higher is important for catalytic activity. The crystal structure demonstrates that the active site of PRORP1 contains two His residues but no conserved lysine or arginine side chains within 8 Å of the metal binding sites. Mutagenesis data demonstrate that the ionization does not reflect one of the His side chains (His-498 and His-438). Therefore, the most likely ionizable functional group within the active site vicinity with a pKa of 8.7 or higher is a metal-bound water molecule as predicted from the [Mg(H2O)6]2+ pKa of 11.4 (24). This proposal is also consistent with the finding that the kmax value is dependent on the pKa of the hydrated metal ion used in the reaction. We therefore propose that the observed ionization in PRORP1 is deprotonation of a metal-bound water to form the attacking hydroxide nucleophile. Bacterial RNase P and T5 Flap endonuclease have a similar pH dependence to PRORP1 with a single deprotonation important for catalysis of phosphodiester bond cleavage, which is proposed to be deprotonation of a metal-bound water (34, 35).

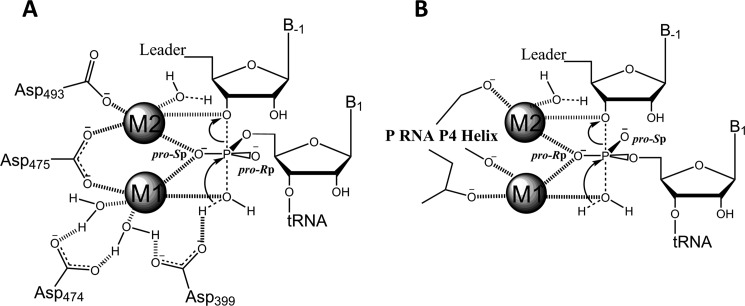

Convergence of Enzyme Mechanism

A comparison of the proposed enzymatic mechanisms of PRORP and RNA-dependent RNase P reveals that both enzymes require catalytic metal ions, although the metal ligands vary (Fig. 9). The metal ions in PRORP1 are coordinated by conserved aspartate residues, whereas the RNA-based RNase P mainly uses non-bridging phosphodiester oxygens for metal ion coordination. Furthermore, the data suggest that one of the scissile phosphate oxygens of pre-tRNA interacts with bound metal ion(s). In PRORP, the pro-Sp oxygen of pre-tRNA is hypothesized to interact with the active site metal ions (23, 36), although this needs to be confirmed experimentally, whereas the pro-Rp substrate oxygen coordinates a metal ion in RNA-based RNase P (37, 38). Modeling of bound substrate suggests that coordination of the pro-Sp or pro-Rp oxygen affects the position of the metal ion relative to the scissile phosphate, leading to an alteration in the pre-tRNA binding mode. Other protein-based phosphoryl transfer enzymes also contact the pro-Sp oxygen of the scissile phosphate, including RNase H, EcoRV, and DNA transposases (39–41). The hammerhead ribozyme and spliceosome are proposed to contact the pro-Rp oxygen at the cleavage site, whereas the Tetrahymena ribozyme contacts the pro-Sp oxygen (42–44).

FIGURE 9.

Proposed enzymatic mechanisms for protein-only (A) and RNA-based (B) RNase P enzymes. Both protein and RNA-based RNase P enzymes use at least two metal ions for phosphodiester bond hydrolysis. The metal ions in PRORP1 are positioned through conserved aspartate residues, whereas the RNA-based RNase P coordinates metal ions mainly using non-bridging phosphate oxygens. Metal I (M1) is proposed to coordinate the nucleophilic water molecule and aid in transition state stabilization by interaction with a non-bridging phosphate oxygen. Metal II (M2) is also proposed to stabilize the transition state and potentially coordinates the 3′-oxyanion leaving group to facilitate bond cleavage.

The RNA-based RNase P reaction has been proposed to catalyze cleavage using a metal-bound hydroxide nucleophile (34). The pH dependence of PRORP1 suggests a similar mechanism for the protein-catalyzed reaction. A possible alternate mechanism is activation of a metal-bound nucleophile by a general base as suggested for EcoRV and RNase H (45, 46). However, two ionizations (slope = 2) and pKa values of ∼6.0–7.0 are observed in pH profiles of these enzymes (45–47), which is significantly different from the pH dependence observed with PRORP1. Thus, it is unlikely that PRORP1 uses a general base mechanism for activation of the nucleophile. In both cases, the metal ions are proposed to stabilize the negative charge buildup in the transition state and facilitate bond cleavage by stabilizing the 3′-oxyanion leaving group. The absence of an alkaline limb on the pH profile for PRORP1 and RNA-based RNase P (48) suggests that an amino acid or nucleotide with a pKa <10 does not serve as a general acid. Rather, the proton donor for the 3′-oxyanion leaving group is most likely a water molecule. The functional convergence of enzymes is not uncommon (49); however, the functional and mechanistic convergence of two different enzymatic macromolecules (RNA and protein) is remarkable. This observation suggests that the protein and RNA macromolecules act as dynamic scaffolds that achieve large rate enhancements mainly through the binding and positioning of hydrated magnesium ions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM055387 (to C. A. F.).

- pre-tRNA

- precursor tRNA

- RNase P

- ribonuclease P

- PRORP

- protein-only RNase P

- NYN

- Nedd4-BP1, YacP nucleases

- STO

- single turnover

- MTO

- multiple turnover

- FP

- fluorescence polarization

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- TCEP

- tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- GMPS

- guanosine 5′-O-monophosphorothioate

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid.

References

- 1. Howard M. J., Liu X., Lim W. H., Klemm B. P., Fierke C. A., Koutmos M., Engelke D. R. (2013) RNase P enzymes: divergent scaffolds for a conserved biological reaction. RNA Biol. 10, 909–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walker S. C., Engelke D. R. (2006) Ribonuclease P: the evolution of an ancient RNA enzyme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41, 77–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gutmann B., Gobert A., Giegé P. (2012) PRORP proteins support RNase P activity in both organelles and the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 26, 1022–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holzmann J., Frank P., Löffler E., Bennett K. L., Gerner C., Rossmanith W. (2008) RNase P without RNA: identification and functional reconstitution of the human mitochondrial tRNA processing enzyme. Cell 135, 462–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rossmanith W. (2012) Of P and Z: mitochondrial tRNA processing enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1819, 1017–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gobert A., Gutmann B., Taschner A., Gössringer M., Holzmann J., Hartmann R. K., Rossmanith W., Giegé P. (2010) A single Arabidopsis organellar protein has RNase P activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 740–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howard M. J., Lim W. H., Fierke C. A., Koutmos M. (2012) Mitochondrial ribonuclease P structure provides insight into the evolution of catalytic strategies for precursor-tRNA 5′ processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16149–16154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anantharaman V., Aravind L. (2006) The NYN domains: novel predicted RNases with a PIN domain-like fold. RNA Biol. 3, 18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Orans J., McSweeney E. A., Iyer R. R., Hast M. A., Hellinga H. W., Modrich P., Beese L. S. (2011) Structures of human exonuclease 1 DNA complexes suggest a unified mechanism for nuclease family. Cell 145, 212–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steitz T. A., Steitz J. A. (1993) A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 6498–6502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Milligan J. F., Uhlenbeck O. C. (1989) Synthesis of small RNAs using T7 RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol. 180, 51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rueda D., Hsieh J., Day-Storms J. J., Fierke C. A., Walter N. G. (2005) The 5′ leader of precursor tRNAAsp bound to the Bacillus subtilis RNase P holoenzyme has an extended conformation. Biochemistry 44, 16130–16139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schattner P., Brooks A. N., Lowe T. M. (2005) The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W686–W689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu X., Chen Y., Fierke C. A. (2014) A real-time fluorescence polarization activity assay to screen for inhibitors of bacterial ribonuclease P. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michaelis L., Menten M. L., Johnson K. A., Goody R. S. (2011) The original Michaelis constant: translation of the 1913 Michaelis-Menten paper. Biochemistry 50, 8264–8269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perrin D. D. (1974) Buffers for pH and Metal Ion Control, Chapman and Hall, London [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perrotta A. T., Shih I., Been M. D. (1999) Imidazole rescue of a cytosine mutation in a self cleaving ribozyme. Science 286, 123–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhaskaran H., Taniguchi T., Suzuki T., Suzuki T., Perona J. J. (2014) Structural dynamics of a mitochondrial tRNA possessing weak thermodynamic stability. Biochemistry 53, 1456–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kurz J. C., Niranjanakumari S., Fierke C. A. (1998) Protein component of Bacillus subtilis RNase P specifically enhances the affinity for precursor-tRNAAsp. Biochemistry 37, 2393–2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frank D. N., Pace N. R. (1997) In vitro selection for altered divalent metal specificity in the RNase P RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 14355–14360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thompson J. E., Raines R. T. (1994) Value of general acid-base catalysis to ribonuclease A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 5467–5468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Brien P. J., Ellenberger T. (2003) Human alkyladenine DNA glycosylase uses acid-base catalysis for selective excision of damaged purines. Biochemistry 42, 12418–12429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pavlova L. V., Gössringer M., Weber C., Buzet A., Rossmanith W., Hartmann R. K. (2012) tRNA processing by protein-only versus RNA-based RNase P: kinetic analysis reveals mechanistic differences. Chembiochem 13, 2270–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cech T. R., Bass B. L. (1986) Biological catalysis by RNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 55, 599–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sillen L. G., Martell A. E. (1971) Stability Constants of Metal-Ion Complexes, Special Publication No. 25, Chemical Society, London [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dahm S., Derrick W. B., Uhlenbeck O. C. (1993) Evidence for the role of solvated metal hydroxide in the hammerhead cleavage mechanism. Biochemistry 32, 13040–13045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giegé R., Jühling F., Pütz J., Stadler P., Sauter C., Florentz C. (2012) Structure of transfer RNAs: similarity and variability. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 3, 37–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beebe J. A., Fierke C. A. (1994) A kinetic mechanism for cleavage of precursor tRNAAsp catalyzed by the RNA component of Bacillus subtilis ribonuclease P. Biochemistry 33, 10294–10304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsieh J., Walker S. C., Fierke C. A., Engelke D. R. (2009) Pre-tRNA turnover catalyzed by the yeast nuclear RNase P holoenzyme is limited by product release. RNA 15, 224–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dupureur C. M. (2010) One is enough: insights into the two-metal ion nuclease mechanism from global analysis and computational studies. Metallomics 2, 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Syson K., Tomlinson C., Chapados B. R., Sayers J. R., Tainer J. A., Williams N. H., Grasby J. A. (2008) Three metal ions participate in the reaction catalyzed by T5 flap endonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28741–28746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang W., Lee J. Y., Nowotny M. (2006) Making and breaking nucleic acids: two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol. Cell 22, 5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsieh J., Fierke C. A. (2009) Conformational change in the Bacillus subtilis RNase P holoenzyme-pre-tRNA complex enhances substrate affinity and limits cleavage rate. RNA 15, 1565–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cassano A. G., Anderson V. E., Harris M. E. (2004) Analysis of solvent nucleophile isotope effects: evidence for concerted mechanisms and nucleophilic activation by metal coordination in nonenzymatic and ribozyme-catalyzed phosphodiester hydrolysis. Biochemistry 43, 10547–10559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tock M. R., Frary E., Sayers J. R., Grasby J. A. (2003) Dynamic evidence for metal ion catalysis in the reaction mediated by a flap endonuclease. EMBO J. 22, 995–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thomas B. C., Li X., Gegenheimer P. (2000) Chloroplast ribonuclease P does not utilize the ribozyme-type pre-tRNA cleavage mechanism. RNA 6, 545–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen Y., Li X., Gegenheimer P. (1997) Ribonuclease P catalysis requires Mg2+ coordinated to the pro-RP oxygen of the scissile bond. Biochemistry 36, 2425–2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Warnecke J. M., Fürste J. P., Hardt W. D., Erdmann V. A., Hartmann R. K. (1996) Ribonuclease P (RNase P) RNA is converted to a Cd2+-ribozyme by a single Rp-phosphorothioate modification in the precursor tRNA at the RNase P cleavage site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8924–8928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nowotny M., Gaidamakov S. A., Crouch R. J., Yang W. (2005) Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell 121, 1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kostrewa D., Winkler F. K. (1995) Mg2+ binding to the active site of EcoRV endonuclease: a crystallographic study of complexes with substrate and product DNA at 2-Å resolution. Biochemistry 34, 683–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kennedy A. K., Haniford D. B., Mizuuchi K. (2000) Single active site catalysis of the successive phosphoryl transfer steps by DNA transposases: insights from phosphorothioate stereoselectivity. Cell 101, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dahm S. C., Uhlenbeck O. C. (1991) Role of divalent metal ions in the hammerhead RNA cleavage reaction. Biochemistry 30, 9464–9469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fica S. M., Tuttle N., Novak T., Li N.-S., Lu J., Koodathingal P., Dai Q., Staley J. P., Piccirilli J. A. (2013) RNA catalyses nuclear pre-mRNA splicing. Nature 503, 229–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shan S., Kravchuk A. V., Piccirilli J. A., Herschlag D. (2001) Defining the catalytic metal ion interactions in the Tetrahymena ribozyme reaction. Biochemistry 40, 5161–5171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stanford N. P., Halford S. E., Baldwin G. S. (1999) DNA cleavage by the EcoRV restriction endonuclease: pH dependence and proton transfers in catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 288, 105–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bastock J. A., Webb M., Grasby J. A. (2007) The pH-dependence of the Escherichia coli RNase HII-catalysed reaction suggests that an active site carboxylate group participates directly in catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 368, 421–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Campbell F. E., Jr., Cassano A. G., Anderson V. E., Harris M. E. (2002) Pre-steady-state and stopped-flow fluorescence analysis of Escherichia coli ribonuclease III: insights into mechanism and conformational changes associated with binding and catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 317, 21–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kurz J. C., Fierke C. A. (2002) The affinity of magnesium binding sites in the Bacillus subtilis RNase P·pre-tRNA complex is enhanced by the protein subunit. Biochemistry 41, 9545–9558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Doolittle R. F. (1994) Convergent evolution: the need to be explicit. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19, 15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]