ABSTRACT

Bats are important reservoirs for several viruses, many of which cause lethal infections in humans but have reduced pathogenicity in bats. As the innate immune response is critical for controlling viruses, the nature of this response in bats and how it may differ from that in other mammals are of great interest. Using next-generation transcriptome sequencing (mRNA-seq), we profiled the transcriptional response of Pteropus vampyrus bat kidney (PVK) cells to Newcastle disease virus (NDV), an avian paramyxovirus known to elicit a strong innate immune response in mammalian cells. The Pteropus genus is a known reservoir of Nipah virus (NiV) and Hendra virus (HeV). Analysis of the 200 to 300 regulated genes showed that genes for interferon (IFN) and antiviral pathways are highly upregulated in NDV-infected PVK cells, including genes for beta IFN, RIG-I, MDA5, ISG15, and IRF1. NDV-infected cells also upregulated several genes not previously characterized to be antiviral, such as RND1, SERTAD1, CHAC1, and MORC3. In fact, we show that MORC3 is induced by both IFN and NDV infection in PVK cells but is not induced by either stimulus in human A549 cells. In contrast to NDV infection, HeV and NiV infection of PVK cells failed to induce these innate immune response genes. Likewise, an attenuated response was observed in PVK cells infected with recombinant NDVs expressing the NiV IFN antagonist proteins V and W. This study provides the first global profile of a robust virus-induced innate immune response in bats and indicates that henipavirus IFN antagonist mechanisms are likely active in bat cells.

IMPORTANCE Bats are the reservoir host for many highly pathogenic human viruses, including henipaviruses, lyssaviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, and filoviruses, and many other viruses have also been isolated from bats. Viral infections are reportedly asymptomatic or heavily attenuated in bat populations. Despite their ecological importance to viral maintenance, research into their immune system and mechanisms for viral control has only recently begun. Nipah virus and Hendra virus are two paramyxoviruses associated with high mortality rates in humans and whose reservoir is the Pteropus genus of bats. Greater knowledge of the innate immune response of P. vampyrus bats to viral infection may elucidate how bats serve as a reservoir for so many viruses.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, interest in bats has steadily increased because of the discovery that they ecologically maintain viruses pathogenic to humans. To date, over 100 viruses have been isolated from bats (1, 2), and they are believed to be a reservoir host for lyssaviruses (including rabies virus) (1, 2), henipaviruses (3, 4), filoviruses (5, 6), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (7). Interestingly, current data suggest that both natural and experimental viral infections are predominantly clinically asymptomatic in bats (3, 8–14). Clinical pathogenicity has been seen only with lyssavirus infections (though the severity of the infection is attenuated compared with that of lyssavirus infections in other mammalian species) (15–19) and Tacaribe virus infections (20), and the filovirus Lloviu virus was associated with bat die-offs in caves in Europe (21). Bats possess many characteristics that make them adept at spreading pathogens, including viruses. They are the only mammals that fly, enabling them to travel large distances (22, 23); they have life spans of up to 35 years (24); some hibernate, allowing overwintering of pathogens (25); and they can live in crowded, large population roosts, facilitating pathogen spread (26). However, none of these physical characteristics can fully explain the ability of bats to harbor so many human pathogens while rarely showing any sign of disease. Precisely what accounts for this balance between the ability of bats to support virus replication and control viral disease remains an open question.

Insight into the immune response of bats could shed light on how they function as reservoir hosts. Current research does not yield a complete picture of the immune system for any one species of bats. Several studies that have examined various aspects of the immune system of a variety of bat species have been done; these studies can be summarized, with the caveat that bats are a diverse order and these findings may not hold true across all species of bats. Examination of the adaptive immune system shows that bats should have all of the cell types required for mounting an effective adaptive immune response, and sequence analysis shows that antibodies produced by bats should undergo class switching, VDJ recombination, and somatic hypermutation (27–31). When looking at the innate immune system, specifically, the production of and signaling through interferon (IFN), bats possess the necessary signaling molecules, both RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (32, 33), type I and II IFNs, and type I and II IFN receptors (34–37). Cells and tissues from bats also have the ability to respond to a variety of stimuli [poly(I·C), virus infection, IFN treatment], producing type I and III IFNs and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (34, 36–41). It appears as though an antiviral state can be established in bat cells because both IFN and supernatant from infected bat cells (which should contain secreted IFNs and other cytokines) protect against further virus challenge (37, 39, 41–43).

While some differences in immunity between bats and other mammals have been discovered, the most notable differences are seen in adaptive immunity. Both B and T cells in bats display delayed and reduced responses to antigen (28, 29), and there appears to be less somatic hypermutation and potentially weaker antibody binding to antigens (30, 31). Differences in the innate immune response could elucidate how bats can control so many different virus infections, but to date, bats do not appear to have any differences greater than the natural variation expected within an order of mammals. More insight into the innate immune system of bats is necessary to see if they possess something unique or lack a standard component or pathway that distinguishes them from other mammals.

Nipah virus (NiV) and Hendra virus (HeV) are two closely related paramyxoviruses whose reservoir hosts are the Pteropus genus of bats. The first outbreak of NiV occurred in 1998 in Malaysia, where pigs were an intermediate and amplifying host that then spread the virus to humans (44). Since then, yearly outbreaks have occurred in Bangladesh, with the virus appearing to spread directly from bats to humans (45, 46). The first outbreak of HeV occurred in Australia in 1994. This virus mainly affects horses, but spillover to humans has occurred (47). Like almost all pathogenic viruses, NiV and HeV have evolved mechanisms to block the type I IFN pathway, and these mechanisms have been characterized in human cells. The IFN antagonists for NiV and HeV are the four proteins produced from the P gene: P, V, W, and C (48). NiV and HeV are believed to share the same mechanism of IFN inhibition. The V and W proteins each block IFN production, with V inhibiting MDA5 signaling in a mechanism conserved among all paramyxoviruses (49–51) and W blocking IFN production from both TLRs and RLRs in a step downstream of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) activation (52). The P, V, and W proteins all inhibit IFN signaling by binding to STAT1 and preventing phosphorylation in response to IFN (53–56). However, IFN production and signaling during NiV infection in vitro are highly variable, depending on the cell type used. In the 293T cell line and human endothelial cells, IFN production is limited, but IFN production is observed in infected human neuronal cells, one of the major targets of NiV replication (57, 58). IFN signaling is reported to be functional in NiV-infected 293T cells (with exogenous IFN), yet there is no evidence of phosphorylated STAT1 in NiV-infected Vero cells treated with IFN, a block relieved by a mutation in the STAT1 binding site in the P gene (57, 59).

For henipavirus IFN antagonist function in bats, it is reported that HeV V can block IFN production in Tb1 Lu cells, lung cells from Tadarida brasiliensis, a bat species that is not a reservoir host for henipaviruses (60). This supports the findings of Virtue et al. (61), who report that immortalized cells from a Pteropus alecto bat do not produce IFN when infected with NiV or HeV, as measured by quantitative PCR. These cells also do not signal through IFN when exogenous IFN is added following infection. However, when these P. alecto cells were infected with HeV and analyzed using next-generation transcriptome sequencing (mRNA-seq), a low-level upregulation of immune genes was observed (62).

To obtain a more detailed picture of the antiviral gene profile in bats, we infected immortalized kidney cells from a Pteropus vampyrus bat with Newcastle disease virus (NDV), which allowed characterization of a robust innate immune response. Next-generation mRNAseq analysis identified many well-characterized IFN-related genes as well as several genes with no reported antiviral role that may represent previously undiscovered innate immune response genes in bats. When these cells were infected with NiV and HeV, no such response was observed, and through the use of recombinant NDV (rNDV) expressing the NiV V and W proteins, we show that the IFN antagonist functions of these proteins are active in P. vampyrus cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Primary P. vampyrus kidney (PPVK) cells were cultured from a P. vampyrus kidney received from the Lubee Bat Conservancy in Gainesville, FL. Upon delivery, the kidney was minced, digested in trypsin, and suspended in fetal bovine serum (FBS). This solution was then centrifuged and filtered through a cell strainer to remove debris. Cells were resuspended in 1× minimal essential medium with 10% FBS and plated in a 10-cm dish. We immortalized these cells by stably expressing human telomerase (hTERT) to create the PVK4 cell line. Approximately 7 × 105 GP2-293 cells (Clontech), which stably express gag and pol from Moloney murine leukemia virus, were transfected in suspension with 2.5 μg each of plasmids expressing vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein and pBABE-hTERT-puro (Addgene plasmid 1771; a gift from Bob Weinberg [63]) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The medium was changed at 24 h postinfection (hpi), and supernatant (2 ml) from transfected cells was harvested at 48 h, filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter, and buffered with HEPES (Corning) at a final concentration of 25 mM. Approximately 1 × 106 PPVK cells were inoculated with 200 μl of undiluted supernatant in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma) for 2 h, and then the inoculum was replaced with 2 ml Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Corning) containing 8 μg/ml Polybrene. This process was repeated 24 h later. At 48 h after dosing of the initial inoculum, cells were transferred to a new dish, and 24 h later puromycin (Gemini) was added at a concentration 2 μg/ml (Fig. 1a). A549, MVI, and Vero cells were purchased from ATCC. Marcel A. Müller and Christian Drosten (University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany) kindly provided the EidNi/41.2 and RoNi/7.3 cells (39) and EpoNi/22.1 cells (64), whose isolation and characterization have been described previously. All cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS (HyClone) and 5% penicillin-streptomycin (Corning).

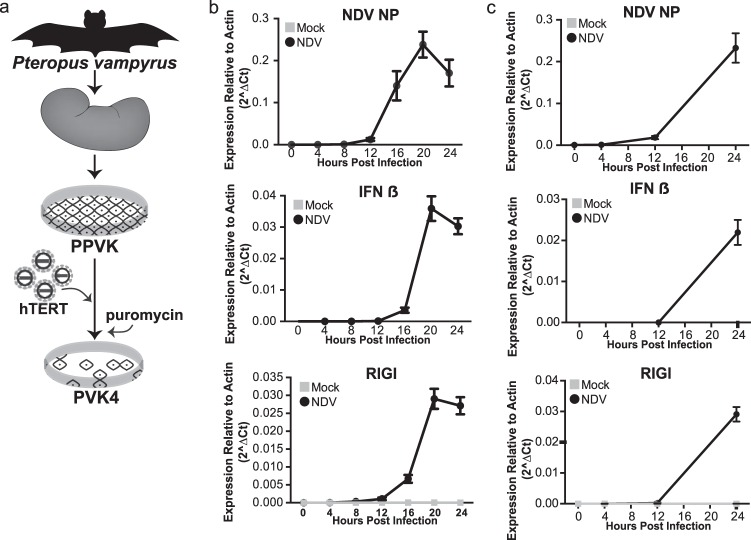

FIG 1.

Formation and characterization of Pteropus vampyrus cells. (a) PPVK cells were cultured from a kidney and then immortalized by ectopically expressing human telomerase using a Moloney murine leukemia virus system, creating the cell line PVK4. (b) qRT-PCR expression of NDV NP, IFN-β, and RIG-I in PPVK cells infected with NDV at an MOI of 0.2 or mock infected. The data shown are normalized to the level of actin expression. Error bars represent standard deviations. No data point signifies that no signal was detected for that sample. (c) qRT-PCR expression of NDV NP, IFN-β, and RIG-I in PVK4 cells infected with NDV at an MOI of 2 or mock infected. The data shown are normalized to the level of actin expression. Error bars represent standard deviations. No data point signifies that no signal was detected for that sample.

Viruses.

rNDV B1 ΔV/NDV V (NDV) has been previously described (65) and is a recombinant virus with mutations removing the P-gene edit site, thereby deleting expression of the V protein. Expression of the V protein is restored by insertion of the V open reading frame. This virus was used because it replicates like wild-type NDV B1 (65) and serves as the parental control for viruses expressing the NiV IFN antagonist proteins (see below). rNDV B1 ΔV/NiV V (rNDV/NiV V) and rNDV B1 ΔV/NiV W (rNDV/NiV W) have been described previously (66) and are recombinant viruses also with mutations removing the P-gene edit site (deleting expression of the V protein). The NiV IFN antagonists V and W were inserted as additional open reading frames. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged NDV (NDV-GFP) has been described previously (67). NDVs were grown in embryonated chicken eggs, and titers were determined on Vero cells by immunofluorescence with an antinucleoprotein (anti-NP) polyclonal antibody (P. Palese lab, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai [ISMMS]). All NDV infections were performed as follows: NDV was diluted in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Corning) with 5% penicillin-streptomycin and 0.3% bovine serum albumin (Fischer) and was inoculated on 1 × 106 cells. After 1 h, the inoculum was replaced with 500 μl Opti-MEM medium (Life Technologies). For NDV-GFP, infections were performed in a 96-well format with 4 × 104 cells per well.

All infections with HeV and NiV were performed under biosafety level 4 (BSL4) containment conditions at the CDC laboratory. HeV and NiV growth curve assays were performed in PVK4 cells. PVK4 cells (1 × 105) were seeded into each well of 12-well plates and grown overnight. On the following day, cells were infected with 1 × 105 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50s) (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 1) of NiV (Malaysian strain, GenBank accession number AF212302) or HeV (GenBank accession number AF017149) in 250 μl for 2 h, and then the inoculum was replaced with growth medium. At 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi, supernatants were harvested for determination of the TCID50s. Cytopathic effect-based TCID50 assays were performed by infecting Vero cells in a 10-fold dilution series of samples (10−1 to 10−8) in a 96-well plate format, infecting 9 wells per sample and dilution step. Plates were read after 7 days to ensure a clear distinction between infected and uninfected wells at the highest dilutions.

RNA isolation.

RNA from PVK4, PPVK, MVI, EidNi/41.2, RoNi/7.3, EpoNi/22.1, and A549 cells infected with NDVs or treated with universal IFN was purified using an RNeasy miniprep (Qiagen) kit following the manufacturer's protocols. RNA was then digested with Turbo DNA-free DNase (Ambion). RNA from PVK4 cells infected with HeV or NiV was isolated using a MagMAX sample preparation system (ABI) and DNase treated according to the manufacturer's protocols.

mRNA-seq.

PPVK cells were infected with NDV at an MOI of 0.2 for 24 h as described above. Purified RNA from NDV- or mock-infected cells was poly(A) selected, converted to cDNA, ligated to platform-specific adapters, and then amplified using an Illumina TruSeq RNA kit. Massively parallel sequencing was carried out on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer at a density of one sample per lane. Reads containing rRNA or Illumina adapters were filtered. The remaining reads were mapped to the P. vampyrus genome build 1 using the TopHat (v2) program and the Ensembl (release 75) gene annotation set. The Cufflinks (v2) program was used to create a de novo transcriptome annotation set, using the Ensembl (release 75) gene annotation set as a reference. Mapped read files were analyzed by use of the HTSeq-Count script to generate a list of reads per exon gene model, and then the DESeq R package was used to perform differential expression analysis. We used the suggested parameters in DESeq for analysis of nonreplicate data sets.

All gene ontology studies were performed on annotated genes differentially regulated more than 2-fold. The list of genes was uploaded into the Interferome (v2.01) database (68). The list of genes and expression data were also uploaded for analysis into Qiagen's Ingenuity pathway analysis database. Genes were mapped to canonical pathways in the Ingenuity database according to the ratio of genes present in our data set to the total number of genes in the pathway, and the P value was calculated by Fisher's exact test. Graphical representation of the Ingenuity data was generated by creating bubble graphs for the canonical pathways, with each pathway representing one bubble. The area of the bubble was calculated using the negative log of the P value. The expression dots of the genes present in each pathway were calculated by making a heat map of the mRNA-seq expression data in the R Studio interface.

For genes that were not identified with the Ensembl or BLAST program, we identified putative genes by evidence of expression in mRNA-seq and homology on the basis of similarity to known proteins. Putative mRNA sequences were extracted using the Cufflinks program-derived region on the genome and then stored as a FastA file of nucleotide sequences. The sequences were compared to those in the nonredundant UniRef protein database (http://www.uniprot.org/uniref/) using a translated nucleotide query against the protein sequences. The top-scoring protein in the UniRef database was used to annotate the putative bat gene.

qRT-PCR.

PPVK, EidNi/41.2, RoNi/7.3, EpoNi/22.1, MVI, or A549 cells (1 × 105) were infected with NDV at an MOI of 2 as described above, and RNA was harvested at 24 hpi. PVK4 cells were infected with NDV at an MOI of 2 as described above, and RNA was harvested every 4 h for 24 h. PVK4 cells (1 × 105) were treated with 10,000 or 2,000 U/ml of universal IFN (Sigma) diluted in 2 ml of DMEM for 24 h. EidNi/41.2, RoNi/7.3, EpoNi/22.1, MVI, or A549 cells (1 × 105) were treated with 2,000 U/ml of universal IFN (Sigma) diluted in 2 ml of DMEM for 24 h. PVK4 cells (1 × 105) were infected with HeV and NiV at an MOI of 10. RNA was isolated as described above. cDNA was synthesized using Invitrogen SuperScript III first-strand synthesis (Life Technologies). Fifteen nanograms of cDNA was used in each quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). qRT-PCR was performed on a Roche LightCycler 480 apparatus using the Roche LightCycler 480 SYBR green I master mix reagent. Validated primers used for human RPS18, RND1, MORC3, SERTAD1, and PPP1R15A were purchased from Bio-Rad. All other primers were designed and synthesized (sequences are available upon request).

Data were analyzed using the normalized expression (2−ΔCT) or fold induction (2−ΔΔCT) threshold cycle (CT) method as noted previously (69). Values represent the means from three replicates, and error bars represent standard deviations. Heat maps were made using the ΔCT method in the R Studio program.

NDV-GFP cytokine bioassay.

PVK4 cells were infected with NDV at an MOI of 2 or PVK4 cells were infected with HeV or NiV at an MOI of 10 for 24 h. The supernatant was UV inactivated and then incubated on 4 × 104 fresh PVK4 cells (NDV, HeV, NiV) or Vero cells (NDV) for 24 h. Cells were then infected with NDV-GFP at an MOI of 1 for 24 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher) and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton (Fisher) in PBS. Cells were then stained with ethidium bromide for 1 h. The levels of GFP and ethidium bromide were read on a TTP Labtech Accumen HCI laser scanning microplate imaging cytometer. Values are presented as the ratio of the GFP signal to the ethidium bromide signal, and then the level of infection for the control sample treated with DMEM only was normalized to 100%. All other values are relative to that value. Values are the averages from three replicates, and error bars represent standard deviations.

Antibodies, immunofluorescence, and Western blotting.

PVK4 cells (1 × 106) were incubated with 10,000 U/ml universal IFN for 1, 3, or 6 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were stained using a human monoclonal STAT1 antibody (catalog number 610185; BD Sciences). Images were taken on a Leica SP5 DM microscope with a 63× immersion lens objective.

PVK4 cells (1 × 105) were seeded into each well of 12-well plates overnight. On the following day, cells were infected with NiV or HeV at an MOI of 1, 5, or 10 in 250 μl for 2 h, and then the inoculum was replaced with growth medium. At 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi, the supernatant was discarded and cells were fixed for 20 min in 10% formalin (Sigma) solution. Cells were then permeabilized with PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and then incubated overnight with an anti-N antibody (which is cross-reactive against both NiV and HeV) in 5% milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) at a dilution of 1:1,000. On the following day, the cells were washed 3 times with PBS-T and incubated with anti-mouse Dylight 488 secondary antibody (Bethyl Laboratories) in PBS-T containing 5% milk at dilutions of 1:500 and 1:1,000, respectively. After 3 washes, fluorescent images were taken on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope at ×20 magnification.

PVK4 cells infected with rNDV/NDV V, rNDV/NiV V, or rNDV/NiV W were infected as described above and harvested at 0, 8, and 24 h in 200 μl 2× SDS lysis buffer with β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), freeze-thawed once, and boiled. Five percent of the lysate was separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (Fisher) and 5% milk. Polyclonal antibodies against NiV V and NiV W (70) and NDV NP (a gift from the P. Palese lab, ISMMS) and a monoclonal antibody against human actin (Sigma) were diluted in the PBS–Tween 20–milk solution, and the mixture was incubated on individual membranes overnight at 4°C. Following washing, membranes were incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Invivogen). Following washing, the membranes were illuminated using enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer), and the signal was detected on a ChemiDoc imager (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Primary and immortalized P. vampyrus cells mount an immune response to NDV infection.

To generate P. vampyrus cells for our studies, we obtained a kidney from a euthanized P. vampyrus bat at the Lubee Bat Conservancy in Gainesville, FL. Primary cells were cultured from this kidney, establishing the primary P. vampyrus kidney (PPVK) cell culture. We then immortalized these primary cells by transduction with a human telomerase-expressing retrovirus to generate the cell line PVK4 (Fig. 1a). To examine the antiviral response of P. vampyrus cells, we infected both primary and immortalized cell cultures with Newcastle disease virus (NDV), a potent activator of the mammalian antiviral response (65). Infection resulted in increased NDV NP expression both in PPVK cells (Fig. 1b) and in PVK4 cells (Fig. 1c), as assayed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). This signifies that cultures of both types of cells can support NDV infection and gene expression, establishing that NDV can be used to explore the response of P. vampyrus cells to virus infection. Since beta IFN (IFN-β) and RIG-I are activation markers of the host innate immune response, we investigated their expression and found that NDV infection of PPVK and PVK4 cells elicited IFN-β production and increased the levels of RIG-I expression, indicative of IFN signaling (Fig. 1b and c).

The innate immune response of PVK4 cells protects against virus challenge.

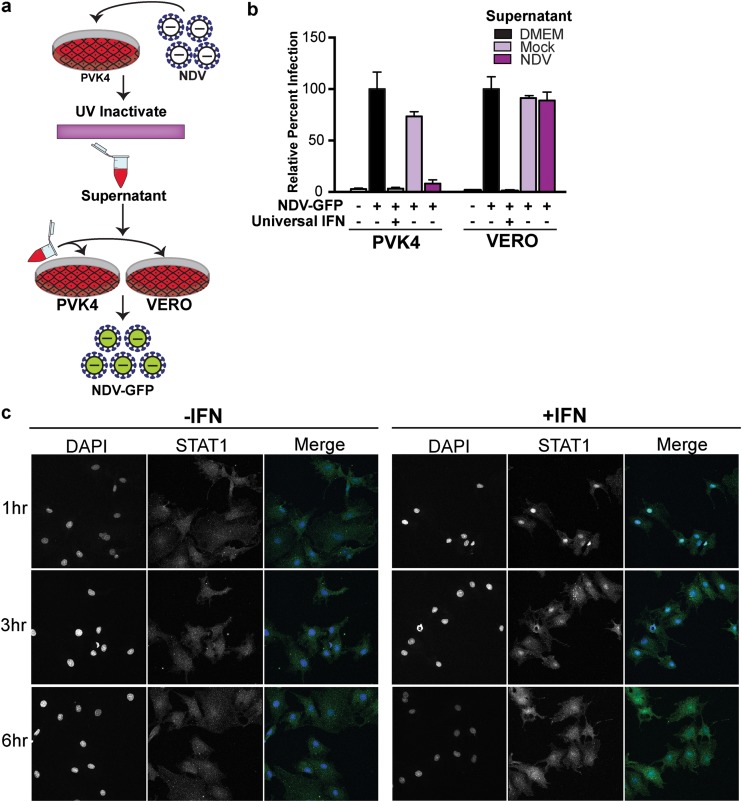

To determine if the antiviral response produced in NDV-infected PVK4 cells is functional, we tested whether the cytokine-containing supernatant from infected cells would be able to protect naive cells from infection. This was achieved by overlaying UV-inactivated supernatant from either NDV- or mock-infected PVK4 cells onto both fresh PVK4 cells and Vero cells and then challenging the cells with NDV-GFP 24 h later (Fig. 2a). Supernatant from NDV-infected PVK4 cells restricted NDV-GFP infection in PVK4 cells but not in Vero cells (Fig. 2b). This indicates a species-specific protective activity of the antiviral cytokines produced by P. vampyrus cells. In contrast, universal IFN, which is a recombinant form of IFN-α that is functional in many mammalian species (71), protected both PVK4 and Vero cells against NDV-GFP infection (Fig. 2b). As another indicator of a functional antiviral response, we examined the nuclear translocation of STAT1 as a measure of JAK/STAT signaling. In PVK4 cells, 1 h of treatment with universal IFN (10,000 U/ml) caused the translocation of STAT1 into the nucleus, which returned to its more diffuse cytoplasmic location after 6 h of treatment (Fig. 2c). This further exemplifies the activation of JAK/STAT signaling in response to type I IFN in P. vampyrus cells.

FIG 2.

Functional characterization of the PVK4 cell innate immune response. (a) NDV-GFP cytokine bioassay. (b) NDV-GFP infection (MOI = 1) in PVK4 and Vero cells treated with universal IFN or UV-inactivated supernatant from NDV-infected (MOI = 2) or mock-infected PVK4 cells. The data shown are the ratio of the GFP signal to the ethidium bromide signal for staining of nuclei. The level of infection for supernatant containing DMEM only was normalized to 100%, and the results for the other samples are shown as a percentage of that value. Error bars represent standard deviations. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of STAT1 in PVK4 cells following universal IFN treatment over 6 h.

Transcriptome analysis of NDV-infected P. vampyrus cells reveals global immune pathway activation.

To obtain a global view of the P. vampyrus innate immune response following NDV infection and to explore the identity and profile of virus-regulated genes, we performed next-generation mRNAseq of NDV-infected (MOI = 0.2, 24 h) and mock-infected PPVK cells using the Illumina platform. As summarized in Table 1, this analysis yielded 7 × 107 to 10 × 107 total reads and 3 × 107 to 5 × 107 unique reads per sample, which indicates considerable depth. A draft genome of P. vampyrus is publically available, and 82% of the total reads in the mock-infected cells and 64% of the total reads in the infected cells were mapped to the genome using TopHat. Of the total reads that remained unmapped by TopHat, 8% (mock-infected cells) and 7% (infected cells) could be mapped to the P. vampyrus genome using the BLAST program. We also mapped 19% of the total reads (5% unique reads) from the infected cells to the rNDV genome, but reassuringly, a negligible number of reads were mapped to the virus from the mock-infected sample. This demonstrates a relatively good infection level in the infected cells and little cross contamination in the mock-infected cells. We also analyzed the data for the presence of other microbes (viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites) but found that sequences for those microbes comprised nothing greater than 0.0001% of total reads (data not shown), suggesting that the P. vampyrus cells are not harboring any known microbial species and that potentially latent viruses were not activated under our culture conditions. Approximately 10% of reads remained unmapped in both mock-infected and infected samples. This value is considered reasonable for this type of analysis.

TABLE 1.

mRNA-seq reads from NDV-infected PPVK cells

| Read group and infection | Total no. of readsa | % reads: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mapped to P. vampyrus genome |

Mapped to NDV | Unmapped | |||

| TopHat | BLAST | ||||

| All reads | |||||

| Mock | 90,272,827 | 82 | 8 | 0 | 10 |

| NDV | 74,396,949 | 64 | 7 | 19 | 10 |

| Unique reads | |||||

| Mock | 54,744,789 | 79 | 6 | 0 | 15 |

| NDV | 38,574,846 | 74 | 8 | 5 | 13 |

Filtered for rRNA and quality.

We next performed quantitative analysis using DeSeq to examine regulated gene expression. Assessment was limited to the reads that were mapped to the P. vampyrus genome using TopHat, and compared with the gene expression in mock-infected cells, NDV infection upregulated 309 genes and downregulated 16 genes (Table 2). The P. vampyrus genome is only partially annotated; therefore, gene names could be assigned to only 267 of these genes. Annotation was carried out using Ensembl and homology with other mammalian species (Table 2; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). We attempted to identify the 52 genes that remained unidentified after analysis with the Ensembl and BLAST programs by examining homology on the basis of similarity to known proteins. Briefly, putative mRNA sequences were extracted using the Cufflinks-derived region on the genome and were then compared to the sequences in the nonredundant UniRef protein database using a translated nucleotide search against the protein sequences (BLASTX). Portions of some of these transcripts showed homology at the protein level to known and putative genes in other species. For example, one of the transcripts showed homology to TRIM3 (the highest percent identity was to Myotis lucifugus; data not shown); however, this homology was not seen at the nucleotide level, potentially indicating a gene that is highly divergent in bats compared to its degree of divergence in other mammalian species.

TABLE 2.

Differentially expressed genes in NDV-infected PPVK cells

| Gene | No. of genes |

|

|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Downregulated | |

| Total | 309 | 16 |

| Annotated | 257a | 10 |

| Unannotated | 52 | 6 |

| Known IFN stimulated | 155 | 1 |

Includes 6 gene families and 3 duplicates.

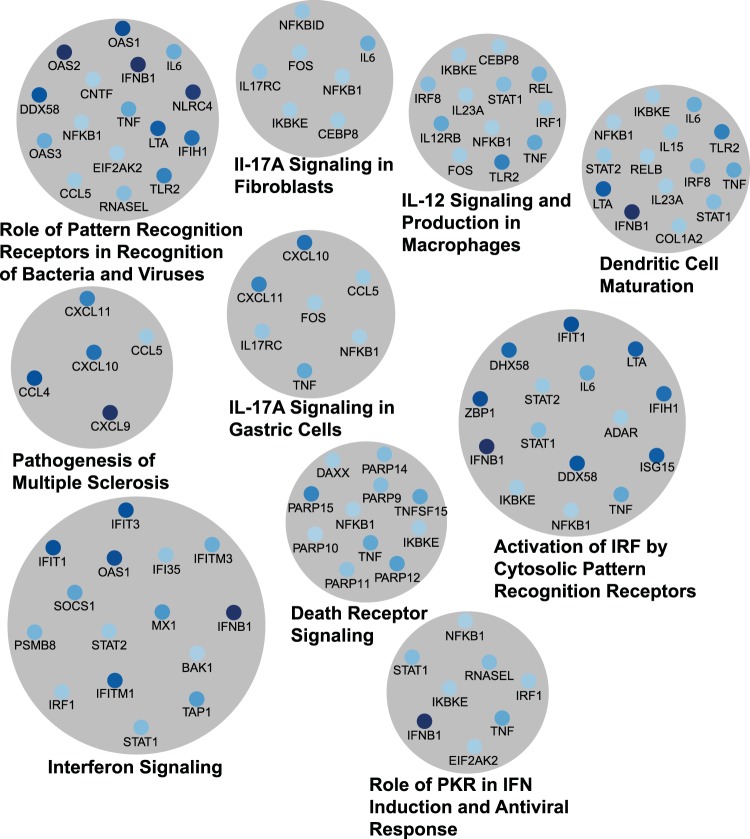

Since NDV is a potent activator of the IFN response, we compared the genes differentially expressed during NDV infection with the genes in a public database of known IFN-regulated genes in mice and humans (Interferome, v2.0 [68]) to see how many of the genes induced during NDV infection were ISGs. We found that 156 genes differentially expressed during NDV infection of PPVK cells are known ISGs in either humans or mice (Table 2; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). Further gene ontology analysis was performed using Ingenuity pathway analysis, which determined the cellular canonical pathways significantly enriched in the data set. Significant pathways included many immune pathways as well as virus detection pathways and apoptosis pathways (Fig. 3; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). The most significantly enriched pathway within our data set was that of interferon signaling (P = 5 × 10−20), followed by activation of an IRF by cytosolic pattern recognition receptors (P = 1 × 10−15) and role of pattern recognition receptors in recognition of bacteria and viruses (P = 3.16 × 10−12). The top 10 pathways are illustrated in Fig. 3, with the size of the gray circle corresponding to the P value. The regulated genes contributing to each pathway are shown in blue, with higher levels of expression being indicated by the darker colors, and vice versa. Many genes are present in more than one pathway, showing the high degree of overlap between different immune pathways.

FIG 3.

Canonical pathways enriched during NDV infection. Genes upregulated during NDV infection were clustered using the Ingenuity pathway analysis software. Shown here are the top 10 canonical pathways and the genes upregulated during NDV infection in each pathway. The area of the circle is inversely proportional to the P value of the pathway. Genes with darker colors are expressed at higher levels. See Table S2 in the supplemental material for a complete list of canonical pathways. IL-17A, interleukin-17A; PKR, RNA-dependent protein kinase.

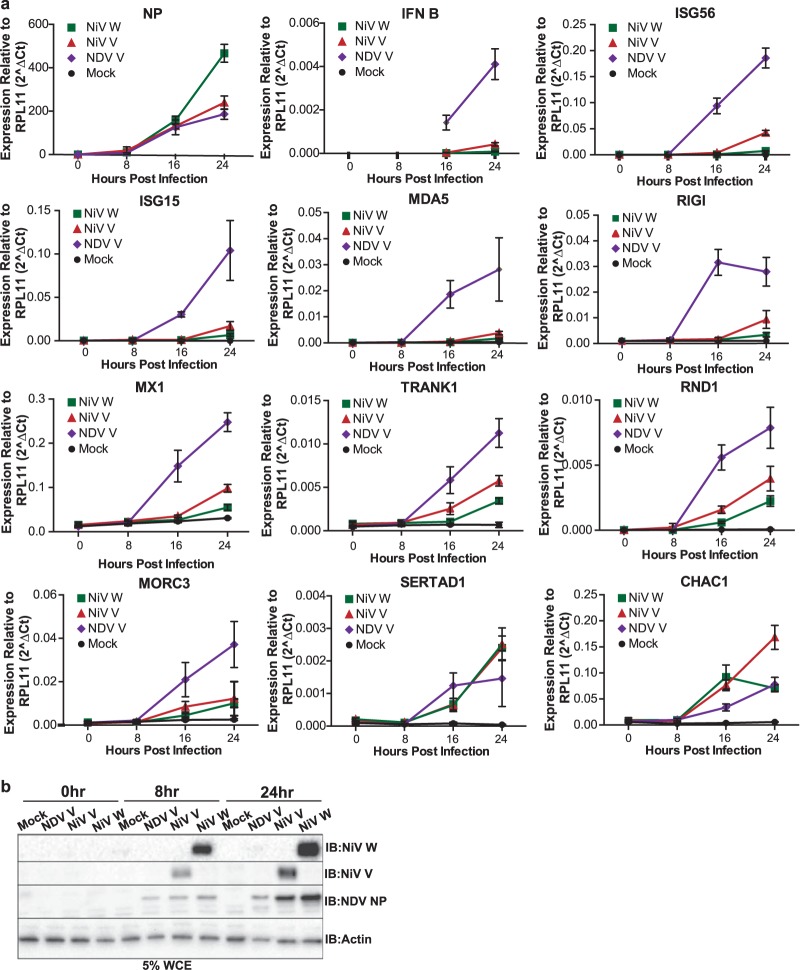

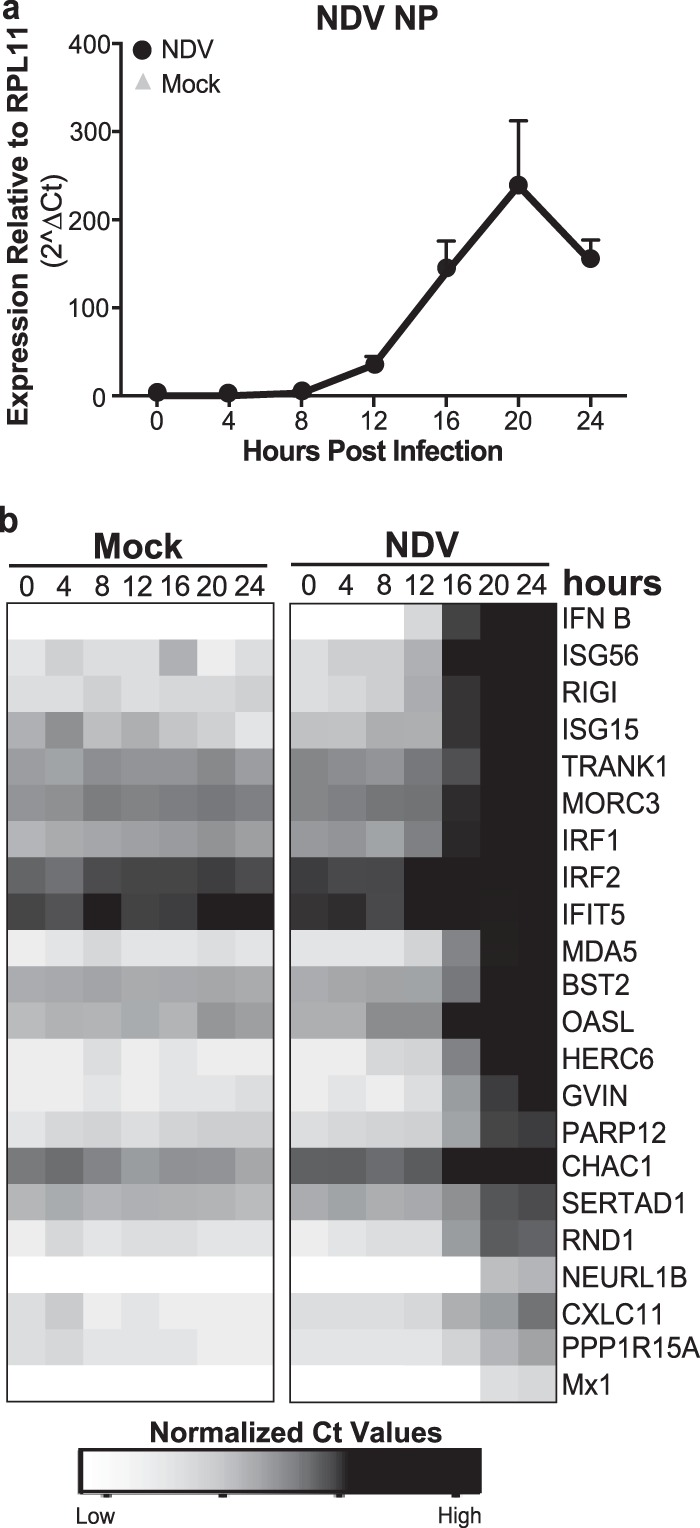

We chose 22 of the 306 upregulated genes for validation using qRT-PCR analysis, including 6 genes (CHAC1, MORC3, PPP1R15A, RND1, SERTAD1, NEURL1B) not present in the Interferome (v2.0) database. Primers specific to these genes were designed on the basis of the sequence information from the mRNAseq data. We infected PVK4 cells with NDV over a 24-h time course and harvested RNA every 4 h for analysis by qRT-PCR. Virus infection increased the expression of all 22 genes, confirming the mRNAseq results (Fig. 4b). Host gene induction in response to NDV infection occurred at between 12 and 20 h, reaching a maximum at 24 h. While PVK4 cells expressed some genes (e.g., IFN-β, NEURL1B, Mx1) at a low basal level and others (e.g., IRF1, IRF2, BST2) at a higher basal level, NDV infection induced the expression of all genes tested, regardless of basal expression levels. These included CHAC1, MORC3, PPP1R15A, RND1, SERTAD1, and NEURL1B, which are not known to be ISGs, at least not in human or murine systems. This gene expression profile is likely representative of an antiviral state in infected PVK4 cells.

FIG 4.

Confirmation of genes upregulated during NDV infection of PVK4 cells. (a and b) qRT-PCR for gene expression in PVK4 cells infected with NDV at an MOI of 2. (a) Level of expression of NDV NP normalized to the level of expression of the housekeeping gene RPL11. (b) Heat map of qRT-PCR expression for the indicated genes, which were selected on the basis of mRNA-seq analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Data are normalized CT values (CTtarget − CTRPL11). Darker boxes indicate higher levels of expression.

Gene expression profiling of NDV-infected P. vampyrus cells elucidates potential differences between the regulation of bat and human antiviral genes.

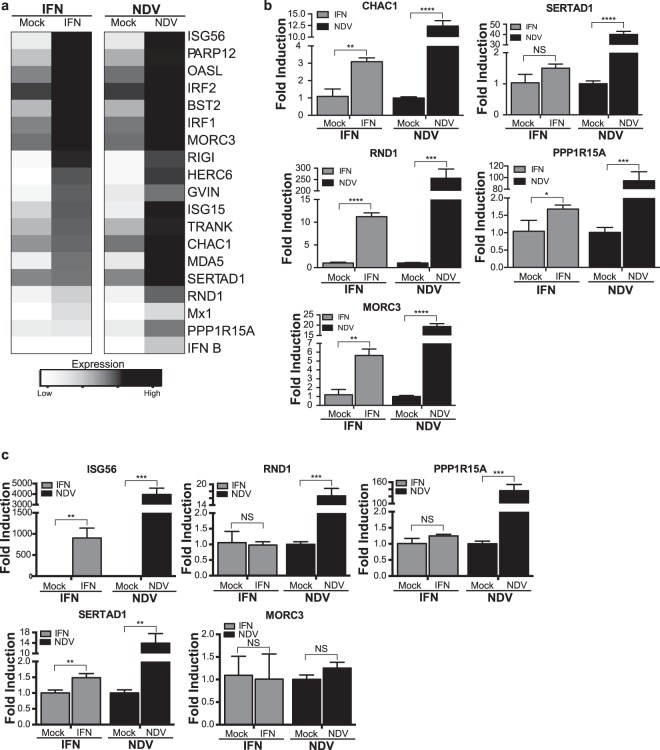

Genes that are transcriptionally upregulated by NDV infection most likely include typical ISGs that respond to activation of the IFN-α/β receptor, but they could also include genes that are activated by the virus independently of IFN. To distinguish between the two, we either treated PVK4 cells with universal IFN (10,000 U/ml, 24 h) or infected PVK4 cells with NDV (MOI = 2, 20 h) and monitored the expression of select genes identified by the mRNAseq study, including both known ISGs and five of the genes yet to be described as ISGs. We found that IFN treatment of PVK4 cells upregulated all genes known to be ISGs (Fig. 5a). These genes included signaling molecules involved in the production of IFN-β (RIG-I, MDA5), transcription factors (IRF1, IRF2), effector molecules (Mx1, BST2), and some with poorly characterized functions (GVIN, TRANK1). While treatment with universal IFN did upregulate all of these genes, the levels of upregulation of many of these genes did not reach the same levels seen with NDV infection. This suggests that virus infection has secondary signals that amplify these genes further.

FIG 5.

Regulation of gene expression in PVK4 cells (a and b) and A549 cells (c) treated with IFN or infected with NDV at an MOI of 2 for 24 h. (a) Heat map of qRT-PCR data for the indicated genes, which were selected from those in Fig. 4b. Data are calculated as normalized CT values (CTtarget − CTRPL11). Darker boxes indicate higher levels of expression. (b and c) Bar graphs of the fold induction of select genes from PVK4 cells (b) and A549 cells (c). Data are presented as the fold induction relative to that for mock-infected cells, and error bars represent standard deviations. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, no statistically significant difference.

We examined the data for those genes not previously described to be ISGs (CHAC1, MORC3, PPP1R15A, RND1, SERTAD1) in more detail to see if their regulation is IFN dependent or independent (Fig. 5b). Since stimulation with IFN induced RND1 and MORC3 more than 5-fold in PVK4 cells compared with their level of induction in mock-treated cells, we believe that these genes may be ISGs in P. vampyrus cells. However, SERTAD1 did not show a statistically significant increase in the level of induction upon IFN stimulation, and PPP1R15A and CHAC1 showed increases of less than 5-fold compared with their levels of induction in mock-treated cells, so we conclude that these three genes are likely not ISGs in P. vampyrus cells (Fig. 5a and b). A lower concentration of universal IFN (2,000 U/ml) provided results that were the same as those depicted in Fig. 5a and b (data not shown).

MORC3, PPP1R15A, RND1, and SERTAD1 are all poorly characterized in other mammalian species. To determine if induction of these genes is regulated similarly or differently in human cells, we treated cells of the human A549 lung cell line with universal IFN (2,000 U/ml, 24 h) or infected them with NDV (MOI = 2, 24 h) and examined gene expression levels via qRT-PCR (Fig. 5c). As a control for IFN signaling, we observed the induction of ISG56 (which is regulated through IFN-dependent and -independent mechanisms) following treatment with universal IFN or NDV infection. Only expression of SERTAD1 was significantly increased by universal IFN, but it was increased less than 2-fold compared with the level of expression in mock-infected cells, so it appears that MORC3, PPP1R15A, RND1, and SERTAD1 are probably not ISGs in human cells, at least A549 cells. In response to NDV infection, the expression levels of RND1, PPP1R15A, and SERTD1 did increase; however, MORC3 expression was not induced upon NDV infection (Fig. 5c). Therefore, we have identified potential species-specific differences in the regulation of certain antiviral response genes. MORC3, which is upregulated in response to both IFN and virus in PVK4 cells, did not respond to either stimulus in A549 cells, while RND1 was regulated by virus infection in both species but responded only to IFN in PVK4 cells.

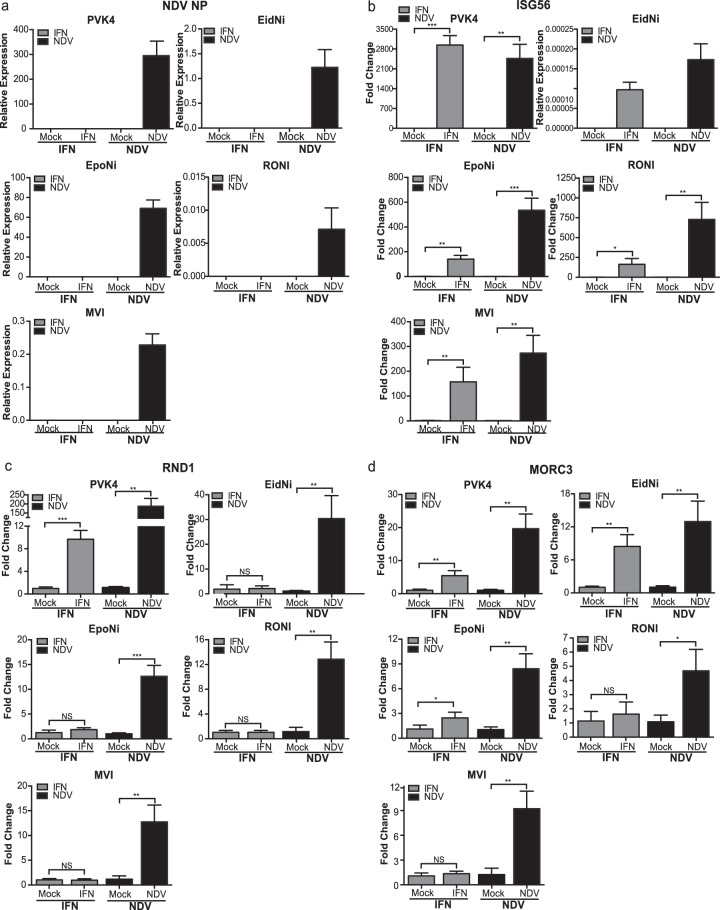

Since bats are a very diverse order, we wanted to determine if IFN or NDV regulation of RND1 and MORC3 occurs in other bat species or if the regulation is P. vampyrus specific. We infected and treated cell lines from four additional species of bats, Eidolon helvum (EidNi/41.2 cells), Epomops buettikoferi (EpoNi/22.1 cells), Rousettus aegyptiacus (RoNi/7.3 cells), and Myotis velifer incautus (MVI cells), with NDV and IFN and tested for the expression of RND1 and MORC3. These cells represent cells of kidney origin from three megabat species (EidNi/41.2, EpoNi/22.1, and RoNi/7.1 cells) and cells of skin tumor origin from one microbat species (MVI cells). qRT-PCR primers were designed using the sequence of the P. vampyrus gene. The increased expression of NDV NP in all infected cell types demonstrates that all four cell lines are susceptible to NDV infection (Fig. 6a), and the increased expression of ISG56 in infected and IFN-treated cells demonstrates that all four cell lines respond to both NDV infection and IFN treatment (Fig. 6b). However, RND1 and MORC3 did not behave similarly in PVK4 cells and cells from other bat species. NDV induced RND1 expression in EidNi/41.2, EpoNi/22.1, RoNi/7.1, and MVI cells, as it did in both PVK4 and A549 cells, while IFN treatment induced RND1 only in PVK4 cells and not EidNi/41.2, EpoNi/22.1, RoNi/7.1, or MVI cells (Fig. 6c). Therefore, RND1 may be a P. vampyrus-specific ISG. The regulation of MORC3, however, varied among the cells from the different bat species. As in PVK4 cells, MORC3 expression was induced in EidNi/41.2 cells upon both NDV infection and IFN treatment (Fig. 6d). In EpoNi/22.1, RoNi/7.1, and MVI cells, NDV infection but not IFN induced MORC3 expression (Fig. 6d). This differs from the regulation in A549 cells, where neither NDV nor IFN induced MORC3 expression.

FIG 6.

Regulation of RND1 and MORC3 in cell lines from different bat species. qRT-PCR analysis for NDV-NP (a), ISG56 (b), RND1 (c), and MORC3 (d) in PVK4, EidNi/41.2, EpoNi/22.1, RoNi/7.3, and MVI cells treated with IFN (2,000 U/ml) or infected with NDV (MOI = 2) for 24 h. Primers for the selected genes were designed from the P. vampyrus genome sequence. The data shown in panel a and for EidNi in panel b are normalized to the expression levels of RPL11. The data shown in the remainder of panel b and in panels c and d are shown as the fold change relative to mock infection. Error bars represent standard deviations. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, no statistically significant difference. No data point signifies that no signal was detected for that sample.

PVK4 cells support henipavirus replication but do not elicit an innate immune response following infection.

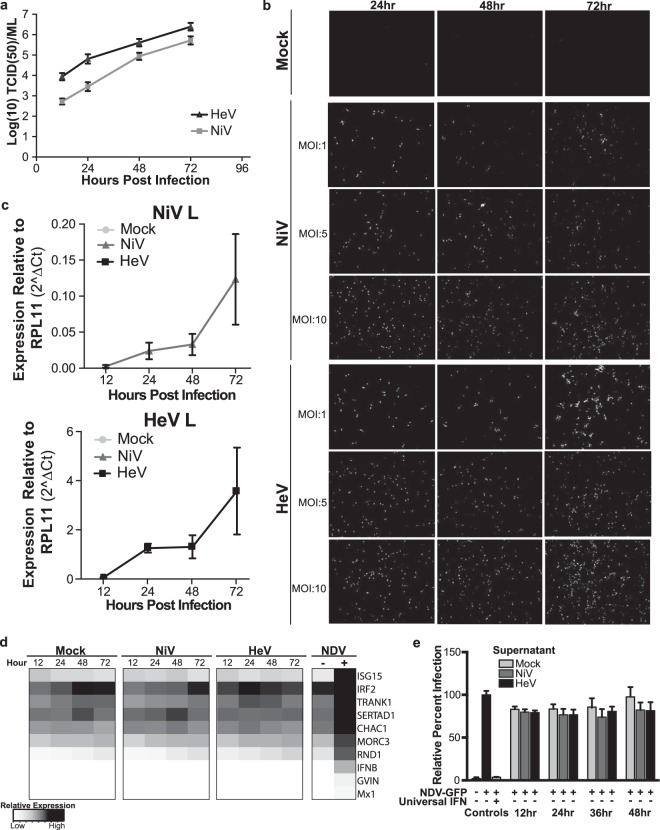

NDV is not a natural pathogen of P. vampyrus or any other species of bat that we are aware of, but it is a useful tool to test the innate immune response of a mammalian species to a virus infection because the NDV IFN antagonist protein is nonfunctional in mammalian cells (65). To test the ability of P. vampyrus cells to support and respond to one of its natural pathogens, we examined the growth of and antiviral response to NiV and HeV in PVK4 cells. All experiments using NiV and HeV were performed under BSL4 containment conditions at the CDC. To examine if PVK4 cells could support the growth and replication of NiV and HeV, we infected PVK4 cells with NiV and HeV (MOI = 1) and harvested virus at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. Both viruses grew to a titer of approximately 106 TCID50s/ml (Fig. 7a). Further demonstrating the ability of PVK4 cells to support henipavirus infection, the infected cells stained positively with an antibody that cross-reacts to the nucleocapsid proteins of both NiV and HeV (Fig. 7b). Cells were infected at MOIs of 1, 5, and 10. Though the monolayer was not completely infected at any MOI, we did see a high percentage of cells infected, with the number of cells infected increasing both with time and with MOI.

FIG 7.

Response to henipavirus infection in PVK4 cells. (a) Multicycle growth curve of HeV and NiV in PVK4 cells. Data are shown as the log number of TCID50s per milliliter at the indicated time points. Error bars represent standard deviations. (b) Immunofluorescence staining of NiV- and HeV-infected PVK4 cells at the indicated MOIs and time points. Virus-infected cells were detected with an antibody against the nucleocapsid protein. (c and d) qRT-PCR of PVK4 cells infected with HeV and NiV at an MOI of 10. (c) Levels of expression of NiV L and HeV L normalized to the level of expression of RPL11. Error bars represent standard deviations. No data point signifies that no signal was detected for that sample. (d) Heat map of qRT-PCR data of gene expression normalized to the level of expression of the housekeeping gene RPL11. The genes selected are a subset of those shown in Fig. 4b. Data are calculated as normalized CT values ((CTtarget − CTRPL11). Darker boxes indicate higher levels of expression. (e) NDV-GFP cytokine bioassay. NDV-GFP infection (MOI = 1) in PVK4 cells treated with universal IFN or UV-inactivated supernatant from henipavirus-infected (MOI = 10) or mock-infected PVK4 cells. Data are shown as the ratio of the GFP signal to the ethidium bromide signal for staining of nuclei. The level of infection for supernatant containing DMEM only was normalized to 100%, and the results for the other samples are shown as a percentage of that value. Error bars represent standard deviations.

To maximize the number of infected cells for analysis of the host immune response, we infected PVK4 with HeV and NiV at an MOI of 10 and extracted RNA at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection for qRT-PCR analysis of host and viral genes. Both NiV- and HeV-infected PVK4 cells showed an increase in L expression over 72 h (Fig. 7c). We examined the expression of 11 genes confirmed to be upregulated by NDV in PVK4 cells, and in contrast to NDV, neither NiV nor HeV induced any of these genes over the 72-h time course (Fig. 7d). To verify this lack of response, we examined the supernatants of HeV- and NiV-infected PVK4 cells (MOI = 10, 24 h) for the presence of protective cytokines. UV-inactivated supernatants were overlaid onto fresh PVK4 cells, which were subsequently challenged with NDV-GFP. In contrast to the results for the IFN-treated control, we did not see protection against NDV-GFP infection with supernatants from HeV- or NiV-infected cells (Fig. 7e), reinforcing the qRT-PCR data showing that henipavirus infection does not upregulate antiviral cytokines in P. vampyrus cells. These data confirm and expand on the inhibition of IFN production seen in P. alecto cells following henipavirus infection (61).

Two reasons can explain why NiV- and HeV-infected PVK4 cells do not mount an IFN response. Either these viruses do not infect to a high enough level and do not produce enough of a signal to trigger a response, or the virus has IFN antagonist mechanisms to block the response. The most well-characterized IFN antagonists of henipaviruses are the V and W proteins; they block both IFN production and signaling (72). To see if the IFN antagonists from NiV are active in PVK4 cells, we infected cells with recombinant NDVs that express either the NiV V (rNDV/NiV V) or NiV W (rNDV/NiV W) protein as an additional open reading frame. These viruses do not express the NDV V protein and have been shown to block the IFN response in human dendritic cells (66). PVK4 cells infected with rNDV expressing NiV V or NiV W showed expression of NDV NP at levels equal to (rNDV/NiV V) or greater than (rNDV/NiV W) the levels of expression by rNDV, demonstrating adequate infection levels (Fig. 8a). The presence of an NiV IFN antagonist also resulted in decreased expression of IFN-β and all ISGs tested (ISG56, ISG15, MDA5, RIG-I, Mx1, TRANK1, RND1, MORC3) compared with the level of expression by the control NDV (Fig. 8a). rNDV/NiV W decreased expression of these genes to a greater extent than rNDV/NiV V, but this could have been due to different expression levels of the NiV IFN antagonists. These results show that the IFN antagonists of NiV retain their activity in PVK4 cells and that blocking of the innate immune response observed in NiV-infected P. vampyrus cells is most likely mediated by the V and W proteins. Two genes that we had determined were regulated independently of IFN, SERTAD1 and CHAC1, showed comparable expression levels following infection with rNDV/NiV V, rNDV/NiV W, or the parental NDV (Fig. 8a). Therefore, NiV V and W do not block the mechanism by which these genes are induced in response to NDV. As they are not induced by NiV infection, either induction is a specific effect of NDV or alternative NiV proteins are responsible for their inhibition.

FIG 8.

Recombinant NDVs expressing NiV IFN antagonists block the innate immune response in PVK4 cells. (a) qRT-PCR analysis of genes in PVK4 cells infected with recombinant NDVs expressing either NDV V, NiV V, or NiV W at an MOI of 2. Genes were selected from those in Fig. 4b. The data shown are levels of expression normalized to the level of actin expression. Error bars represent standard deviations. No data point signifies that no signal was detected for that sample. (b) Western blot (immunoblot [IB]) showing the expression of NDV NP, NiV V, and NiV W from PVK4 cells infected with rNDVs expressing NDV V, NiV V, and NiV W. Actin levels are shown as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

We generated primary (PPVK) and immortalized (PVK4) cells from the kidney of a P. vampyrus bat and show that these cells support infection with NDV, as well as NiV and HeV. NDV infection of P. vampyrus cells produced a robust and protective antiviral immune response. In contrast, NiV and HeV infections as well as infections with rNDVs that express the IFN antagonists of NiV in PVK4 cells did not elicit an innate immune response, leading to the conclusion that the IFN antagonist functions of NiV are intact in these cells. Using next-generation sequencing technology, we were able to characterize the full profile of the antiviral response of PPVK cells to NDV infection and identify several factors potentially unique to the innate immune system of P. vampyrus.

Interest in the innate immune responses of bats has increased as it has become clear that bats are the reservoir hosts for many human viruses and, as such, that they must have mechanisms to control these infections while still allowing transmission events (1, 2). Most previously published studies on this subject have used a targeted approach and investigated innate immune molecules known to be important to antiviral responses in human or murine systems. This includes studies that have characterized the sequences and predicted the structures of select immune receptors, signaling molecules, and transcription factors, such as TLRs (32, 33), RLRs (34, 40), type I and type III IFNs (35–37), and other cytokines (73). Other studies examined stimulation of the bat innate immune response [with poly(I·C), type I or III IFN, virus infection], but they examined the production only of known IFNs and ISGs (34, 37–39, 41, 74, 75), limiting the analysis to whether the bat response is similar to that of other mammals or if bats lack something known to be functionally important in other mammals. We employed a broad, nonbiased approach to describe the complete transcriptional response of P. vampyrus cells to virus infection with the goal of ascertaining any novel immune factors. To do this, we used mRNAseq technology on P. vampyrus cells infected with NDV, chosen as a stimulus because it is known to induce a robust immune response in mammalian cells (65). In a similar study by Papenfuss et al. (76), the investigators performed mRNAseq analysis on mitogen-stimulated P. alecto tissues that had been pooled from multiple sources, and they compared the total transcriptome with the sequences in a mammalian sequence database to identify orthologues of immune genes known to be induced in these bat cells. While both analyses have the potential to discover novel factors, our use of virus-infected cells that were quantitatively compared with noninfected cells and our use of a defined bat cell culture system allowed us to more specifically focus on genes induced in response to viral infection. During the manuscript's preparation, Wynne et al. (62) reported on the transcriptome of HeV-infected P. alecto cells. While they observed the induction of innate immune response genes, the fact that HeV has mechanisms to inhibit these pathways probably means that they could not capture the full scale of this response or the entire repertoire of induced genes. NDV, on the other hand, is not a natural mammalian pathogen, and consequently, it does not block the mammalian IFN response. This makes it a useful tool for stimulating a strong innate immune response in mammalian cells via exposure to natural viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns [as opposed to poly(I·C)].

As expected, mRNAseq analysis of NDV-infected P. vampyrus cells revealed the significant upregulation of genes enriched in antiviral immune pathways. By comparing these genes with the genes in a database of mouse and human ISGs (Interferome, v2.0 [68]), we could distinguish between those genes that have been described to be ISGs in other species and those that have not, and these differences may represent differences with respect to the bat antiviral response. Even within the list of known ISGs identified, some are very poorly characterized. One such gene is TRANK1 (tetratricopeptide repeat and ankyrin repeat containing 1). While it is present in the Interferome ISG database, a functional role for TRANK1 in immunity has not yet been described. However, since TRANK1 has been identified to be an ISG in both humans and P. vampyrus cells, it may be an important immune factor, and further study could shed light on its conserved function. A second poorly characterized ISG that we identified in PVK4 cells is GVIN1 (GTPase, very large interferon inducible 1). GVIN1 is in the family of IFN-induced GTPases, like the Mx proteins (77). It is a guanine nucleotide binding protein that, in addition to being expressed in response to type I and II IFNs, is also upregulated upon Listeria monocytogenes infection in mice (78). While rodents express seven members of the GVIN family, primates do not express any GVIN family protein (humans have one pseudogene for GVIN). We can hypothesize that since rodents and bats are the most abundant mammalian reservoirs of human pathogens (1, 2, 79), an immune gene that is present in these orders but is absent in humans is potentially an important player in how rodents and bats function as reservoirs.

Several genes in our data set of P. vampyrus genes upregulated during NDV infection were not present in the Interferome (v2.0) database, and therefore, there is currently no evidence that these genes are ISGs in humans or mice. When we further characterized the regulation of the bat and human homologues, we confirmed that two were ISGs in P. vampyrus cells but not in human cells. One such gene was RND1, a Rho GTPase that lacks GTP hydrolysis function and interferes with cytoskeleton function by destabilizing microtubules, leading to a loss of cell matrix adhesion. RND1 is thought to function primarily in neuronal axon formation (80–82). RND1 was identified in a screen for genes required for HIV replication (83), which is likely related to its regulation of the cytoskeleton. However, there is no evidence in the literature for any immune or antiviral function associated with RND1. Given the different regulation mechanisms observed in P. vampyrus versus humans, it is plausible that in P. vampyrus the role of RND1 in altering the cytoskeleton has been adapted as an antiviral mechanism.

Another gene that appears to be differentially regulated in P. vampyrus versus human cells is MORC3 (MORC family CW-type zinc finger 3), which is upregulated in response to both IFN and NDV in PVK4 cells but not in A549 cells. MORC3 (also known as NXP2) is a nuclear protein with RNA binding activity (84) and is reported to localize to promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies in a SUMO-dependent manner, where it regulates p53 activity (85). This is reminiscent of PML itself, a TRIM family member that is induced by IFN and has antiviral activity (86, 87). In P. vampyrus, it is possible that MORC3 participates in the antiviral response coordinated from these subnuclear domains.

When we examined cells from additional bat species (3 megabats and 1 microbat), we found that the regulation of RND1 and MORC3 varied across the different bat species. RND1 was stimulated by IFN only in PVK4 cells and not in cells of the other bat species, and yet all cells upregulated RND1 in response to NDV infection. This could signify that this factor is important only in P. vampyrus, though it would be prudent to test the regulation of this gene in other species from the Pteropus genus. The regulation of MORC3 was even more varied. Though NDV does not induce MORC3 in human cells, NDV did induce MORC3 expression in all bat cells tested. Thus, MORC3 may be an important antiviral gene in both megabats and microbats. However, IFN regulation of MORC3 appears to be more specific and was observed only in PVK4 and EidNi/41.2 cells. In general, while virus induction of these two potential innate immune response genes appears to be conserved across the Chiroptera order, IFN regulation is more species specific.

There were also two genes (SERTAD1 and PPP1R15A) induced in response to NDV but not IFN (or induced in response to IFN only to a limited extent) in both PVK4 and A549 cells. This indicates that they are not classical ISGs (activated by JAK/STAT signaling) but, rather, are activated by virus in an IFN-independent manner. SERTAD1 is a transcriptional regulator that interacts with PHD zinc fingers present in transcription factors. It is involved in cyclin E-mediated cell cycle progression and is believed to be an antiapoptosis factor in cancer cells (88–90). No immune or antiviral role has been described for SERTAD1, but both P. vampyrus and humans may have exploited the antiapoptosis function of SERTAD1 as a defense mechanism against viruses that induce apoptosis, including NDV (91, 92), as well as adenoviruses (93, 94), papillomaviruses (95), herpesviruses (96, 97), alphaviruses (98), and influenza viruses (99). Perhaps the most interesting set of genes that were upregulated in response to NDV infection consisted of genes that could not be annotated. This implies that they are significantly different from their counterparts in other mammals, such that they could not be identified by BLAST analysis, or that counterparts do not exist in other mammals and that these may be unique to P. vampyrus (and possibly other bat species.) In time, once more bat genomes become available and annotation is performed more thoroughly, this can, it is hoped, be addressed.

As P. vampyrus serves as a reservoir host for NiV and HeV, we explored whether these viruses induced the same genes induced by NDV but determined that, in contrast to NDV, the henipaviruses do not lead to the same robust innate immune response in P. vampyrus cells. Our findings support and expand on those of Virtue et al. (61), who reported that NiV and HeV infection of P. alecto does not result in IFN production. However, they examined only samples collected at time points very early in infection (3 h). We confirmed the lack of IFN production over a longer infection period (72 h), as measured both by IFN-β mRNA production and by indirectly detecting protective cytokines secreted from infected cells using an antiviral cytokine bioassay. We also measured the response of select IFN-independent genes (CHAC1 and SERTAD1) to HeV and NiV infection and did not observe the upregulation of any these genes.

A lack of an IFN response from NiV- and HeV-infected cells could stem from one of two causes: not enough signal from the infection was present to stimulate a response, or competent IFN antagonists from these viruses blocked the response. We believe that immunofluorescence staining of NiV- and HeV-infected cells showed that the proportion of cells infected at the MOI used for determination of immune activation (MOI = 10) was high enough. Thus, the more likely explanation is that induction of an innate immune response was actively blocked in henipavirus-infected bat cells. This could be demonstrated through the use of rNDVs expressing NiV IFN antagonists (V and W), which, unlike the parental NDV, failed to induce IFN or ISGs. This leads us to conclude that the IFN antagonists of NiV function in PVK4 cells. Since the antagonist mechanisms for NiV and HeV are conserved (50, 53, 72, 100), we can hypothesize that the IFN antagonists of HeV function in PVK4 cells as well. Therefore, it seems likely that the IFN antagonist capabilities of these viruses evolved in their reservoir host (Pteropus bats) and not specifically in their incidental host (humans).

Finally, it is important to note that results seen in one species of bat may not hold true across the entire order, as we discovered with the ability of IFN to regulate RND1 and MORC3 expression. Chiroptera diverged approximately 63 million years ago (101) and comprises 20% of all mammalian species (2), making it a very diverse order. For example, in a study by Zhou et al. (38), neither Sendai virus nor the bat reovirus pteropine orthoreovirus NB caused the upregulation of PKR (EIF2AK2) in P. alecto lung cells, even though both of these viruses elicited a strong IFN response (38). In contrast, we observed the upregulation of EIF2AK2 following NDV infection in P. vampyrus kidney cells. This finding and the data presented on RND1 and MORC3 demonstrate that there may be differences in gene regulation depending on the species, tissue, and stimulus, and these differences are important to consider when interpreting the findings of immune studies for all species of bats.

In summary, we have determined that P. vampyrus cells infected with NDV mount a robust innate immune response but that this immune response is blunted following NiV or HeV infection due to the actions of henipavirus IFN antagonist proteins. We were also able to ascertain potentially novel immune factors that may play a role in the ability of bats (or certain species thereof) to serve as reservoir hosts for human viruses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by in part by NIH grants HHSN272200900032C, R01 AI101308, and R21AI102169 to M.L.S. N.B.G. was supported in part by NIH training grant T32AI007647.

We thank the Lubee Bat Conservancy for providing us with a P. vampyrus kidney. EidNi/41.2, RoNi/7.3, and EpoNi/22 cells were kindly provided by Marcel A. Müller and Christian Drosten, Institute of Virology, University of Bonn Medical Centre, Bonn, Germany. We also thank the P. Palese laboratory for providing the NDV NP antibody and Matthew Urbanowski for help with immunofluorescence images.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00302-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker ML, Schountz T, Wang L-F. 2013. Antiviral immune responses of bats: a review. Zoonoses Public Health 60:104–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calisher CH, Childs JE, Field HE, Holmes KV, Schountz T. 2006. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 19:531–545. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00017-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpin K, Hyatt AD, Fogarty R, Middleton D, Bingham J, Epstein JH, Rahman SA, Hughes T, Smith C, Field HE, Daszak P. 2011. Pteropid bats are confirmed as the reservoir hosts of henipaviruses: a comprehensive experimental study of virus transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85:946–951. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halpin K, Young PL, Field HE, Mackenzie JS. 2000. Isolation of Hendra virus from pteropid bats: a natural reservoir of Hendra virus. J Gen Virol 81:1927–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Towner JS, Pourrut X, Albarino CG, Nkogue CN, Bird BH, Grard G, Ksiazek TG, Gonzalez JP, Nichol ST, Leroy EM. 2007. Marburg virus infection detected in a common African bat. PLoS One 2:e764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Delicat A, Paweska JT, Gonzalez JP, Swanepoel R. 2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438:575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, Ren W, Smith C, Epstein JH, Wang H, Crameri G, Hu Z, Zhang H, Zhang J, McEachern J, Field H, Daszak P, Eaton BT, Zhang S, Wang LF. 2005. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe S, Masangkay JS, Nagata N, Morikawa S, Mizutani T, Fukushi S, Alviola P, Omatsu T, Ueda N, Iha K, Taniguchi S, Fujii H, Tsuda S, Endoh M, Kato K, Tohya Y, Kyuwa S, Yoshikawa Y, Akashi H. 2010. Bat coronaviruses and experimental infection of bats, the Philippines. Emerg Infect Dis 16:1217–1223. doi: 10.3201/eid1608.100208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sulkin SE, Allen R, Sims R. 1963. Studies of arthropod-borne virus infections in Chiroptera. I. Susceptibility of insectivorous species to experimental infection with Japanese B and St. Louis encephalitis viruses. Am J Trop Med Hyg 12:800–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanepoel R, Leman PA, Burt FJ, Zachariades NA, Braack LE, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Zaki SR, Peters CJ. 1996. Experimental inoculation of plants and animals with Ebola virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2:321–325. doi: 10.3201/eid0204.960407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson MM, Hooper PT, Selleck PW, Westbury HA, Slocombe RF. 2000. Experimental Hendra virus infection in pregnant guinea-pigs and fruit bats (Pteropus poliocephalus). J Comp Pathol 122:201–207. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1999.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Middleton DJ, Morrissy CJ, van der Heide BM, Russell GM, Braun MA, Westbury HA, Halpin K, Daniels PW. 2007. Experimental Nipah virus infection in pteropid bats (Pteropus poliocephalus). J Comp Pathol 136:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halpin K, Mungall BA. 2007. Recent progress in henipavirus research. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 30:287–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drexler JF, Corman VM, Wegner T, Tateno AF, Zerbinati RM, Gloza-Rausch F, Seebens A, Müller MA, Drosten C. 2011. Amplification of emerging viruses in a bat colony. Emerg Infect Dis 17:449–456. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.100526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freuling C, Vos A, Johnson N, Kaipf I, Denzinger A, Neubert L, Mansfield K, Hicks D, Nunez A, Tordo N, Rupprecht CE, Fooks AR, Muller T. 2009. Experimental infection of serotine bats (Eptesicus serotinus) with European bat lyssavirus type 1a. J Gen Virol 90:2493–2502. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.011510-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson FR, Turmelle AS, Farino DM, Franka R, McCracken GF, Rupprecht CE. 2008. Experimental rabies virus infection of big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus). J Wildl Dis 44:612–621. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.3.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid JE, Jackson AC. 2001. Experimental rabies virus infection in Artibeus jamaicensis bats with CVS-24 variants. J Neurovirol 7:511–517. doi: 10.1080/135502801753248097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turmelle AS, Jackson FR, Green D, McCracken GF, Rupprecht CE. 2010. Host immunity to repeated rabies virus infection in big brown bats. J Gen Virol 91:2360–2366. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuzmin IV, Franka R, Rupprecht CE. 2008. Experimental infection of big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) with West Caucasian bat virus (WCBV). Dev Biol (Basel) 131:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cogswell-Hawkinson A, Bowen R, James S, Gardiner D, Calisher CH, Adams R, Schountz T. 2012. Tacaribe virus causes fatal infection of an ostensible reservoir host, the Jamaican fruit bat. J Virol 86:5791–5799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00201-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negredo A, Palacios G, Vazquez-Moron S, Gonzalez F, Dopazo H, Molero F, Juste J, Quetglas J, Savji N, de la Cruz Martinez M, Herrera JE, Pizarro M, Hutchison SK, Echevarria JE, Lipkin WI, Tenorio A. 2011. Discovery of an Ebolavirus-like filovirus in Europe. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002304. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Constantine DG. 2003. Geographic translocation of bats: known and potential problems. Emerg Infect Dis 9:17–21. doi: 10.3201/eid0901.020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Shea TJ, Cryan PM, Cunningham AA, Fooks AR, Hayman DT, Luis AD, Peel AJ, Plowright RK, Wood JL. 2014. Bat flight and zoonotic viruses. Emerg Infect Dis 20:741–745. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.130539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuweiler G. 2000. The biology of the bats. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyman CP. 1970. Thermoregulation and metabolism in bats, p 301–330. In Wimsatt WA. (ed), Biology of bats. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunz TH, Lumsden LF. 2003. Ecology of cavity and foliage roosting bats, p 3–89. In Kunz TH, Fenton MB (ed), Bat ecology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkar SK, Chakravarty AK. 1991. Analysis of immunocompetent cells in the bat, Pteropus giganteus: isolation and scanning electron microscopic characterization. Dev Comp Immunol 15:423–430. doi: 10.1016/0145-305X(91)90034-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakravarty AK, Paul BN. 1987. Analysis of suppressor factor in delayed immune responses of a bat, Pteropus giganteus. Dev Comp Immunol 11:649–660. doi: 10.1016/0145-305X(87)90053-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakraborty AK, Chakravarty AK. 1984. Antibody-mediated immune response in the bat, Pteropus giganteus. Dev Comp Immunol 8:415–423. doi: 10.1016/0145-305X(84)90048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bratsch S, Wertz N, Chaloner K, Kunz TH, Butler JE. 2011. The little brown bat, M. lucifugus, displays a highly diverse V(H), D(H) and J(H) repertoire but little evidence of somatic hypermutation. Dev Comp Immunol 35:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker ML, Tachedjian M, Wang LF. 2010. Immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity in pteropid bats: evidence for a diverse and highly specific antigen binding repertoire. Immunogenetics 62:173–184. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0425-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iha K, Omatsu T, Watanabe S, Ueda N, Taniguchi S, Fujii H, Ishii Y, Kyuwa S, Akashi H, Yoshikawa Y. 2010. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of bat Toll-like receptors 3, 7 and 9. J Vet Med Sci 72:217–220. doi: 10.1292/jvms.09-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cowled C, Baker M, Tachedjian M, Zhou P, Bulach D, Wang L-F. 2011. Molecular characterisation of Toll-like receptors in the black flying fox Pteropus alecto. Dev Comp Immunol 35:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omatsu T, Bak E-J, Ishii Y, Kyuwa S, Tohya Y, Akashi H, Yoshikawa Y. 2008. Induction and sequencing of Rousette bat interferon α and β genes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 124:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He G, He B, Racey PA, Cui J. 2010. Positive selection of the bat interferon alpha gene family. Biochem Genet 48:840–846. doi: 10.1007/s10528-010-9365-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou P, Cowled C, Marsh GA, Shi Z, Wang L-F, Baker ML. 2011. Type III IFN receptor expression and functional characterisation in the pteropid bat, Pteropus alecto. PLoS One 6:e25385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He X, Korytar T, Schatz J, Freuling CM, Muller T, Kollner B. 2014. Anti-lyssaviral activity of interferons kappa and omega from the serotine bat, Eptesicus serotinus. J Virol 88:5444–5454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03403-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou P, Cowled C, Wang L-F, Baker ML. 2013. Bat Mx1 and Oas1, but not Pkr are highly induced by bat interferon and viral infection. Dev Comp Immunol 40:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biesold SE, Ritz D, Gloza-Rausch F, Wollny R, Drexler JF, Corman VM, Kalko EKV, Oppong S, Drosten C, Müller MA. 2011. Type I interferon reaction to viral infection in interferon-competent, immortalized cell lines from the African fruit bat Eidolon helvum. PLoS One 6:e28131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cowled C, Baker ML, Zhou P, Tachedjian M, Wang L-F. 2012. Molecular characterisation of RIG-I-like helicases in the black flying fox, Pteropus alecto. Dev Comp Immunol 36:657–664. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou P, Cowled C, Todd S, Crameri G, Virtue ER, Marsh GA, Klein R, Shi Z, Wang L-F, Baker ML. 2011. Type III IFNs in pteropid bats: differential expression patterns provide evidence for distinct roles in antiviral immunity. J Immunol 186:3138–3147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart WE II, Scott WD, Sulkin SE. 1969. Relative sensitivities of viruses to different species of interferon. J Virol 4:147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janardhana V, Tachedjian M, Crameri G, Cowled C, Wang L-F, Baker ML. 2012. Cloning, expression and antiviral activity of IFNγ from the Australian fruit bat, Pteropus alecto. Dev Comp Immunol 36:610–618. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Harcourt BH, Tamin A, Lam SK, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Zaki SR, Shieh W, Goldsmith CS, Gubler DJ, Roehrig JT, Eaton B, Gould AR, Olson J, Field H, Daniels P, Ling AE, Peters CJ, Anderson LJ, Mahy BW. 2000. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science 288:1432–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Homaira N, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Epstein JH, Sultana R, Khan MS, Podder G, Nahar K, Ahmed B, Gurley ES, Daszak P, Lipkin WI, Rollin PE, Comer JA, Ksiazek TG, Luby SP. 2010. Nipah virus outbreak with person-to-person transmission in a district of Bangladesh. Epidemiol Infect 138:1630–1636. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luby SP, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ. 2009. Transmission of human infection with Nipah virus. Clin Infect Dis 49:1743–1748. doi: 10.1086/647951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahalingam S, Herrero LJ, Playford EG, Spann K, Herring B, Rolph MS, Middleton D, McCall B, Field H, Wang LF. 2012. Hendra virus: an emerging paramyxovirus in Australia. Lancet Infect Dis 12:799–807. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park MS, Shaw ML, Munoz-Jordan J, Cros JF, Nakaya T, Bouvier N, Palese P, Garcia-Sastre A, Basler CF. 2003. Newcastle disease virus (NDV)-based assay demonstrates interferon-antagonist activity for the NDV V protein and the Nipah virus V, W, and C proteins. J Virol 77:1501–1511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1501-1511.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Childs K, Stock N, Ross C, Andrejeva J, Hilton L, Skinner M, Randall R, Goodbourn S. 2007. mda-5, but not RIG-I, is a common target for paramyxovirus V proteins. Virology 359:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parisien JP, Bamming D, Komuro A, Ramachandran A, Rodriguez JJ, Barber G, Wojahn RD, Horvath CM. 2009. A shared interface mediates paramyxovirus interference with antiviral RNA helicases MDA5 and LGP2. J Virol 83:7252–7260. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00153-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andrejeva J, Childs KS, Young DF, Carlos TS, Stock N, Goodbourn S, Randall RE. 2004. The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, mda-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN-beta promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:17264–17269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407639101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaw ML, Cardenas WB, Zamarin D, Palese P, Basler CF. 2005. Nuclear localization of the Nipah virus W protein allows for inhibition of both virus- and Toll-like receptor 3-triggered signaling pathways. J Virol 79:6078–6088. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6078-6088.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ludlow LE, Lo MK, Rodriguez JJ, Rota PA, Horvath CM. 2008. Henipavirus V protein association with Polo-like kinase reveals functional overlap with STAT1 binding and interferon evasion. J Virol 82:6259–6271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00409-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodriguez JJ, Cruz CD, Horvath CM. 2004. Identification of the nuclear export signal and STAT-binding domains of the Nipah virus V protein reveals mechanisms underlying interferon evasion. J Virol 78:5358–5367. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5358-5367.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez JJ, Parisien JP, Horvath CM. 2002. Nipah virus V protein evades alpha and gamma interferons by preventing STAT1 and STAT2 activation and nuclear accumulation. J Virol 76:11476–11483. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11476-11483.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaw ML, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P, Basler CF. 2004. Nipah virus V and W proteins have a common STAT1-binding domain yet inhibit STAT1 activation from the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments, respectively. J Virol 78:5633–5641. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5633-5641.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Virtue ER, Marsh GA, Wang LF. 2011. Interferon signaling remains functional during henipavirus infection of human cell lines. J Virol 85:4031–4034. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02412-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lo MK, Miller D, Aljofan M, Mungall BA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, Rota PA. 2010. Characterization of the antiviral and inflammatory responses against Nipah virus in endothelial cells and neurons. Virology 404:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ciancanelli MJ, Volchkova VA, Shaw ML, Volchkov VE, Basler CF. 2009. Nipah virus sequesters inactive STAT1 in the nucleus via a P gene-encoded mechanism. J Virol 83:7828–7841. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02610-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hagmaier K, Stock N, Goodbourn S, Wang L-F, Randall R. 2006. A single amino acid substitution in the V protein of Nipah virus alters its ability to block interferon signalling in cells from different species. J Gen Virol 87:3649–3653. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82261-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Virtue ER, Marsh GA, Baker ML, Wang L-F. 2011. Interferon production and signaling pathways are antagonized during henipavirus infection of fruit bat cell lines. PLoS One 6:e22488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wynne JW, Shiell BJ, Marsh GA, Boyd V, Harper JA, Heesom K, Monaghan P, Zhou P, Payne J, Klein R, Todd S, Mok L, Green D, Bingham J, Tachedjian M, Baker ML, Matthews D, Wang LF. 2014. Proteomics informed by transcriptomics reveals Hendra virus sensitizes bat cells to TRAIL mediated apoptosis. Genome Biol 15:532. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0532-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Counter CM, Hahn WC, Wei W, Caddle SD, Beijersbergen RL, Lansdorp PM, Sedivy JM, Weinberg RA. 1998. Dissociation among in vitro telomerase activity, telomere maintenance, and cellular immortalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:14723–14728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuhl A, Hoffmann M, Müller MA, Munster VJ, Gnirss K, Kiene M, Tsegaye TS, Behrens G, Herrler G, Feldmann H, Drosten C, Pohlmann S. 2011. Comparative analysis of Ebola virus glycoprotein interactions with human and bat cells. J Infect Dis 204(Suppl 3):S840–S849. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]