Abstract

Background

The NLST (National Lung Screening Trial) showed reduced lung cancer mortality in high-risk participants (smoking history of ≥30 pack-years) aged 55 to 74 years who were randomly assigned to screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) versus those assigned to chest radiography. An advisory panel recently expressed reservations about Medicare coverage of LDCT screening because of concerns about performance in the Medicare-aged population, which accounted for only 25% of the NLST participants.

Objective

To examine the results of the NLST LDCT group by age (Medicare-eligible vs. <65 years).

Design

Secondary analysis of a group from a randomized trial (NCT00047385).

Setting

33 U.S. screening centers.

Patients

19 612 participants aged 55 to 64 years (under-65 cohort) and 7110 participants aged 65 to 74 years (65+ cohort) at randomization.

Intervention

3 annual rounds of LDCT screening.

Measurements

Demographics, smoking and medical history, screening examination adherence and results, diagnostic follow-up procedures and complications, lung cancer diagnoses, treatment, survival, and mortality.

Results

The aggregate false-positive rate was higher in the 65+ cohort than in the under-65 cohort (27.7% vs. 22.0%; P < 0.001). Invasive diagnostic procedures after false-positive screening results were modestly more frequent in the older cohort (3.3% vs. 2.7%; P = 0.039). Complications from invasive procedures were low in both groups (9.8% in the under-65 cohort vs. 8.5% in the 65+ cohort). Prevalence and positive predictive value (PPV) were higher in the 65+ cohort (PPV, 4.9% vs. 3.0%). Resection rates for screen-detected cancer were similar (75.6% in the under-65 cohort vs. 73.2% in the 65+ cohort). Five-year all-cause survival was lower in the 65+ cohort (55.1% vs. 64.1%; P = 0.018).

Limitation

The oldest screened patient was aged 76 years.

Conclusion

NLST participants aged 65 years or older had a higher rate of false-positive screening results than those younger than 65 years but a higher cancer prevalence and PPV. Screen-detected cancer was treated similarly in the groups.

Primary Funding Source

National Institutes of Health.

The NLST (National Lung Screening Trial) reported a reduction in lung cancer mortality in high-risk participants aged 55 to 74 years who were randomly assigned to low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening compared with those randomly assigned to chest radiography (CXR) screening (1). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently issued a grade B recommendation for LDCT screening for persons meeting the NLST eligibility criteria for smoking history (2), primarily on the basis of the NLST results. The USPSTF broadened the age criteria modestly to an upper limit of 80 years, based in part on modeling studies (2, 3).

Several months after the final USPSTF recommendation was released, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) convened a Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) meeting to advise CMS on coverage decisions for LDCT screening in the Medicare population. For the question “How confident are you that there is adequate evidence to determine if the benefits outweigh the harms of lung cancer screening with LDCT in the Medicare population?,” the MEDCAC panel’s average response was 2.2 on a scale of 1 (low confidence) to 5 (high confidence) (4). The panel members also had an average response of 2.3 to the question of how confident they were that the harms of lung cancer screening could be minimized in the Medicare population.

Some of the concerns expressed by the MEDCAC panel did not pertain directly to age but to more general issues involving quality control of screening and potential “indication creep” (screening being disseminated to lower-risk populations). However, many of the concerns were directly related to age and the uncertainty about the effectiveness and potential for harms in the population of persons aged 65 years or older (4). The primary source of evidence for LDCT effectiveness was the NLST, and because only 25% of the NLST participants were aged 65 years or older at randomization, there were reservations about whether the overall NLST results could be applied to the Medicare-aged population. Specific concerns were raised that older persons might have substantially more comorbid conditions, with more harms from diagnostic work-ups, more frequent ineligibility for curative surgery for screen-detected cancer, and increased postsurgical mortality compared with younger eligible persons.

Context

A large trial showed that screening high-risk persons with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduced lung cancer mortality, but experts question the utility of screening older persons.

Contribution

This secondary analysis of the trial found that lung cancer prevalence, the positive predictive value of LDCT screening, and the rate of false-positive results were higher in persons aged 65 to 74 years than those aged 55 to 64 years. Detected cancer was treated similarly in both groups, but 5-year survival was lower in the older group.

Caution

Persons older than 74 years were not studied.

Implication

Screening Medicare-eligible persons results in more false-positive findings but identifies more lung cancer than screening younger persons.

—The Editors

We examine several facets of LDCT screening in the NLST by age group (≥65 years vs. <65 years), including participant demographics, screening adherence and results, diagnostic follow-up, performance characteristics of LDCT, treatment and survival of patients with screen-detected cancer, and lung cancer mortality. These data will enable a more informed discussion of the relative benefits and harms of LDCT screening in the Medicare-aged eligible population.

Methods

NLST Design

The NLST randomly assigned persons aged 55 to 74 years to LDCT or CXR screening. Eligibility criteria included a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years and current smoking or having quit within the past 15 years (5). Participant data on medical and smoking history were self-reported in questionnaires. Participants were enrolled at 33 U.S. screening centers during 2002 to 2004 and received either LDCT or CXR screening at baseline (year 0) and annually for 2 more years (years 1 and 2). Blocked randomization was used, with stratification by age, sex, and screening center. The NLST was approved by the institutional review board at each screening center. All participants provided informed consent.

NLST Protocol

The NLST protocol defined a positive screening result as a noncalcified nodule with a greatest transverse diameter of at least 4 mm (5). Other abnormalities, including mediastinal or hilar adenopathy and pleural effusion, could also constitute a positive result. Radiologists reported other findings not related to lung cancer, including emphysema, cardiac abnormalities, and any other clinically significant abnormality. Screening results were classified as positive, negative without abnormalities, negative with minor abnormalities, or negative with clinically significant abnormalities (not suspicious for lung cancer). The NLST radiologists also recorded their recommendations for diagnostic follow-up, which included LDCT at various time intervals, diagnostic computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and biopsy. There was no trial-wide algorithm for diagnostic follow-up, which was conducted outside of trial auspices and managed by participants’ personal physicians.

NLST Follow-up and Outcomes

Positive screening results were tracked with respect to resultant diagnostic procedures and cancer diagnoses. In addition, participants were followed with annual surveys to ascertain incident cancer cases in the absence of positive screening results. All reported cancer cases were verified with medical records. Deaths were tracked with the annual surveys and supplemented by National Death Index searches, with an end point verification process used to verify cause of death.

Statistical Analysis

Our analyses involved participants from the LDCT group only and compared baseline characteristics, screening results, and downstream outcomes for the under-65 cohort (aged <65 years at randomization) versus the 65+ cohort (aged ≥65 years at randomization). Results of an analysis of the NLST mortality rate ratios for lung cancer between the LDCT and CXR groups for the 2 cohorts were reported previously (6).

The proportion of participants adhering to screening, by round, was defined as the proportion of those eligible for a given screening round who were actually screened. Lung cancer was deemed present at a screening if it was diagnosed within 1 year or before the next screening (whichever came first) or, for positive screening results, if it was diagnosed after a longer period but without a gap of more than 1 year between diagnostic procedures. If lung cancer was deemed present, the cancer was categorized as screen-detected (true-positive) if the screening result was positive and false-negative if the screening result was negative. False-positive rates (1 – specificity) and sensitivity were derived from the aforementioned definitions of true-positive and false-negative results, as was positive predictive value (PPV). Numbers of participants with at least 1 LDCT screening-related event (such as a false-positive screening result or a negative screening result with clinically significant abnormalities) were used to derive frequencies of events per 10 000 NLST participants in each cohort.

Participants were followed until 31 December 2009, death, or loss to follow-up, whichever came first. All-cause and lung cancer–specific survival rates for patients with lung cancer were computed from the time of diagnosis, with censoring of participants who did not have the end point of interest by the end of follow-up.

We used chi-square tests to compare baseline factors and characteristics of screen-detected cancer cases by age group. To compare differences by age group in the aggregate rates (across all screening rounds) of screening and diagnostic follow-up results when there were multiple outcomes per participant, we used logistic regression models for repeated measures fit with generalized estimating equations (7). These models included a term for age group only; no other covariates were included because the goal of this analysis was to examine differences between age groups, not to identify causative factors. We used the Kaplan–Meier method to generate survival curves, with differences in survival between age groups assessed by using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute); PROC GENMOD was used for the repeated-measures logistic regression models, and PROC LIFETEST was used for the Kaplan–Meier curves.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported by grants and contracts from the National Institutes of Health. Two of the authors are employees of the National Institutes of Health; otherwise, the sponsor had no role in the study design, analysis or interpretation of data, or writing of the report.

Results

A total of 26 722 participants were randomly assigned to the LDCT group of the NLST (19 612 in the under-65 cohort and 7110 in the 65+ cohort). Table 1 shows baseline demographics, smoking history, and comorbid conditions of the cohorts. Compared with participants in the under-65 cohort, those in the 65+ cohort were less likely to be current smokers (40.1% vs. 51.0%) and had greater median pack-years (52 vs. 46). The 65+ cohort had higher rates of comorbid conditions; history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was reported in 17.4% of participants in the 65+ cohort versus 11.8% in the under-65 cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants in the LDCT Group, by Age

| Characteristic | Under-65 Cohort | 65+ Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Participants enrolled, n | 19 612 | 7110 |

| Male, % | 58.0 | 61.8 |

| Median age (IQR), y | 59 (56–61) | 68 (66–70) |

| Current smoking, % | 51.0 | 40.1 |

| Median smoking history (IQR), pack-years | 46 (38–65) | 52 (43–75) |

| Time since quitting, % 1–5 y |

46.2 | 33.7 |

| 6–10 y Medical history, % |

27.0 | 29.4 |

| ≥11 y | 26.8 | 37.0 |

| Emphysema | 6.5 | 11.1 |

| COPD | 11.8 | 17.4 |

| Diabetes | 9.2 | 11.2 |

| Heart disease | 11.1 | 18.2 |

| Stroke | 2.3 | 4.4 |

| Hypertension | 32.6 | 42.4 |

| COPD, diabetes, heart disease, or stroke | 28.5 | 40.3 |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR = interquartile range; LDCT = low-dose computed tomography.

Adherence to screening was similar in the cohorts (98.5%, 93.9%, and 92.9% for years 0, 1, and 2, respectively, in the under-65 cohort vs. 98.6%, 94.4%, and 93.0% in the 65+ cohort). Table 2 shows the results of the LDCT screening examinations and diagnostic follow-up. Rates of positive and false-positive screening results were higher at each round in the 65+ cohort. Across all screening rounds, the aggregate false-positive rate was higher in the 65+ cohort (27.7%) than the under-65 cohort (22.0%) (P = 0.001). Invasive procedures after false-positive results were modestly more frequent in the older cohort; aggregate frequencies (across screening rounds) were 2.7% in the under-65 cohort and 3.3% in the 65+ cohort (P = 0.039). Complications from invasive procedures after false-positive results occurred at similarly low frequencies for the under-65 (9.8%) and 65+ (8.5%) cohorts (P = 0.62).

Table 2.

Positive and False-Positive Screening Results and Diagnostic Follow-up, by Age

| Variable | Under-65 Cohort

|

65+Cohort

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 0 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Total | Year 0 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Total | |

| Screened, n | 19 306 | 18 184 | 17 798 | 55 288 | 7003 | 6531 | 6304 | 19 838 |

|

| ||||||||

| Participants screened, n (%) | ||||||||

| Positive result | 4947 (25.6) | 4773 (26.3) | 2726 (15.3) | 12 446 (22.5) | 2244 (32.0) | 2131 (32.6) | 1320 (20.9) | 5695 (28.7) |

|

| ||||||||

| Cancer not present at screening* | 19 147 (99.2) | 18 081 (99.4) | 17 664 (99.3) | 54 892 (99.3) | 6874 (98.2) | 6456 (98.9) | 6211 (98.5) | 19 541 (98.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| False-positive results among participants with cancer not present at screening, n (%) | 4796 (25.1) | 4678 (25.9) | 2603 (14.7) | 12 077 (22.0) | 2125 (30.9) | 2058 (31.9) | 1232 (19.8) | 5415 (27.7) |

| Procedures among participants with false-positive results, n (%) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Surgical procedure | 60 (1.3) | 34 (0.7) | 25 (1.0) | 119 (1.0) | 29 (1.4) | 17 (0.8) | 18 (1.5) | 64 (1.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Invasive procedure | 168 (3.5) | 84 (1.8) | 73 (2.8) | 325 (2.7) | 86 (4.1) | 44 (2.1) | 47 (3.8) | 177 (3.3) |

| Complications among participants with invasive procedures, n (%) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Complications | 10 (5.9) | 14 (16.7) | 8 (11.0) | 32 (9.8) | 8 (9.3) | 2 (4.5) | 5 (11.6) | 15 (8.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| Major complications | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (4.1) | 6 (1.9) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (4.6) | 2 (4.3) | 6 (3.4) |

Includes tests with positive results and incomplete information on diagnostic follow-up (n = 102 [year 0], 113 [year 1], and 103 [year 2] in the under-65 cohort; n = 37 [year 0], 49 [year 1], and 34 [year 2] in the 65+ cohort).

Sensitivity of LDCT was similar in the cohorts across screening rounds (93.2% in the under-65 cohort vs. 94.3% in the 65+ cohort). Despite the higher false-positive rate, the aggregate PPV was higher in the 65+ cohort (4.9%) than the under-65 cohort (3.0%) (P < 0.001) due to the substantially higher prevalence of lung cancer (proportion of screenings with lung cancer present) in the 65+ cohort (1.5% vs. 0.7%; P < 0.001). Raw counts of positive and negative screening results by cancer status in each cohort are provided in the Appendix Table (available at www.annals.org).

Appendix Table.

Aggregate True-Positive, False-Positive, True-Negative, and False-Negative Results, by Age

| Screening Result | Under-65 Cohort

|

65+ Cohort

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Present | Cancer Not Present | Cancer Present | Cancer Not Present | |

| Positive, n | 369 | 12 077 | 280 | 5415 |

|

| ||||

| Negative, n | 27 | 42 815 | 17 | 14 126 |

Table 3 shows LDCT screening results for non–lung cancer findings. Negative results with clinically significant abnormalities were more frequent in the 65+ cohort; aggregate frequencies were 9.2% in that cohort versus 6.9% in the under-65 cohort (P < 0.001). Reported abnormal findings on the screening, including emphysema, cardiovascular abnormalities, and abnormalities above and below the diaphragm, were also higher in the older cohort (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Findings Not Related to Lung Cancer, by Age

| Variable | Under-65 Cohort

|

65+ Cohort

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 0 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Total | Year 0 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Total | |

| Participants screened, n | 19 306 | 18 184 | 17 798 | 55 288 | 7003 | 6531 | 6304 | 19 838 |

|

| ||||||||

| Negative result with clinically significant abnormalities, n (%) | 1810 (9.4) | 1015 (5.6) | 972 (5.5) | 3797 (6.9) | 884 (12.6) | 502 (7.7) | 437 (6.9) | 1823 (9.2) |

| Specific findings, n (%) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Emphysema | 5522 (28.6) | 5660 (31.1) | 6006 (33.8) | 17 188 (31.1) | 2597 (37.1) | 2516 (38.5) | 2593 (41.1) | 7706 (38.8) |

|

| ||||||||

| Significant cardiovascular abnormality | 1062 (5.5) | 796 (4.4) | 901 (5.1) | 2759 (5.0) | 633 (9.0) | 483 (7.4) | 511 (8.1) | 1627 (8.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Abnormalities above diaphragm | 942 (4.9) | 611 (3.4) | 484 (2.7) | 2037 (3.7) | 466 (6.7) | 288 (4.4) | 210 (3.3) | 964 (4.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Abnormalities below diaphragm | 984 (5.1) | 742 (4.1) | 731 (4.1) | 2457 (4.4) | 490 (7.0) | 383 (5.9) | 334 (5.3) | 1207 (6.1) |

Table 4 shows findings with respect to screen-detected cancer. Stage and histology did not statistically differ between the cohorts. Similar proportions in each cohort had resection (75.6% in the under-65 cohort vs. 73.2% in the 65+ cohort). Among stage I cases, resection frequencies were high in both cohorts (96.9% in the under-65 cohort vs. 93.0% in the 65+ cohort). Postsurgical mortality at 90 days was low in each cohort (1.8% and 1.0% in the under-65 and 65+ cohorts, respectively; P = 0.81).

Table 4.

Histology, Stage, Treatment, and Postsurgical Mortality for Screen-Detected Cancer, by Age

| Variable | Under-65 Cohort | 65+ Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer cases, n | 369 | 280 |

|

| ||

| Median age at diagnosis (IQR), y | 61 (58–63) | 70 (68–72) |

| Histology, % | ||

|

| ||

| Adenocarcinoma (including bronchioloalveolar carcinoma) | 56.9 | 50.7 |

|

| ||

| Squamous cell | 17.9 | 25.0 |

|

| ||

| Other non–small cell lung cancer | 17.3 | 17.1 |

|

| ||

| Small cell | 7.9 | 7.1 |

| TNM stage, % | ||

|

| ||

| I | 62.1 | 61.1 |

|

| ||

| II | 6.2 | 8.2 |

|

| ||

| III/IV | 28.5 | 30.0 |

|

| ||

| Resection, % | 75.6 | 73.2 |

|

| ||

| Resection for stage I cancer, % | 96.9 | 93.0 |

|

| ||

| Death within 30 d of resection, % | 0.7 | 0.5 |

|

| ||

| Death within 90 d of resection, % | 1.8 | 1.0 |

IQR = interquartile range; TNM = tumor, node, metastasis.

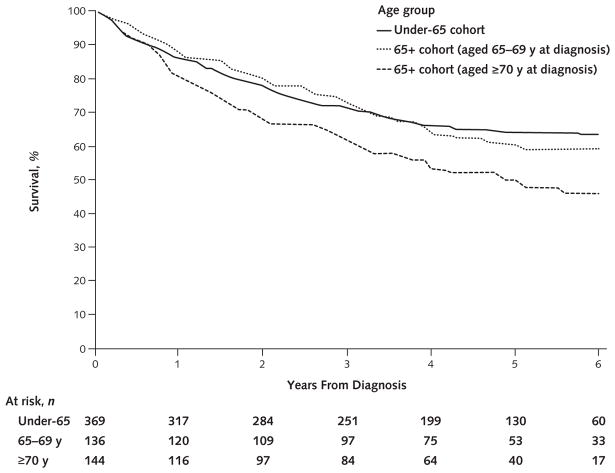

Among screen-detected cancer cases in the 65+ cohort, we further stratified participants into subgroups of those aged 65 to 69 years (n = 136) and those aged 70 years or older (n = 144) at diagnosis. The 65– 69 subgroup had a borderline statistically significantly higher resection rate (77.9%) than the 70subgroup (68.8%) (P = 0.083). The Figure shows all-cause survival for participants with screen-detected cancer in these 2 subgroups as well as the under-65 cohort. Median follow-up for participants who survived was 5.3 years in the under-65 cohort, 5.6 years in the 65– 69 group, and 4.9 years in the 70+ group. Five-year all-cause survival was 60.2% in the 65– 69 group versus 50.0% in the 70+ group (P = 0.018) and was 55.1% in the entire 65+ cohort compared with 64.1% in the under-65 cohort (P = 0.018). The corresponding values for 5-year lung cancer–specific survival were 67.5% for the under-65 cohort, 66.7% for the 65– 69 group, and 56.5% for the 70+ group.

Figure.

All-cause survival among patients with screen-detected cancer, by age group.

Table 5 shows the number of screen-related outcomes per 10 000 participants in the under-65 and 65+ cohorts. Participants in the older cohort were more likely to have a false-positive screening result (4145 vs. 3474) and a subsequent invasive diagnostic procedure (242 vs. 162). They were also more likely to have a negative screening result with clinically significant abnormalities. Screen-detected cancer was about twice as frequent in the 65+ cohort (394 cases) than in the under-65 cohort (188 cases), and lung cancer deaths were 2.4-fold as frequent in the older cohort (304 vs. 129).

Table 5.

Outcomes in the LDCT Group, by Age

| Outcome | Frequency per 10 000 Participants (95% CI), n | |

|---|---|---|

| Under-65 Cohort | 65+ Cohort | |

| ≥1 negative screening result with clinically significant abnormalities | 1493 (1443–1543) | 1934 (1842–2026) |

| ≥1 false-positive screening result | 3474 (3407–3541) | 4145 (4030–4259) |

| ≥1 invasive diagnostic procedure after false-positive result | 162 (144–180) | 242 (206–277) |

| Surgical procedure | 60 (49–70) | 89 (67–110) |

| Nonsurgical procedure only | 102 (88–117) | 153 (125–182) |

| Major complication | 3 (1–6) | 8 (2–15) |

| Screen-detected cancer | 188 (169–207) | 394 (349–439) |

| Lung cancer death | 129 (113–145) | 304 (264–344) |

LDCT =low-dose computed tomography.

Discussion

In general, cancer screening is more efficient in higher-risk populations because persons can benefit from it only if they develop the cancer of interest, whereas the harms of screening are usually relatively constant across the cancer risk spectrum. After smoking, arguably the next most important risk factor for lung cancer is age. Seventy percent of all U.S. lung cancer cases are diagnosed at age 65 years or later, and the relative risk for lung cancer for persons aged 75 to 79 years compared with those aged 50 to 54 years is 8.7 (8). Our analysis showed that the PPV, a measure of screening efficiency that is related to prevalence, was higher in the 65+ cohort (4.9%) than the under-65 cohort (3.0%); furthermore, the frequency of screen-detected cancer was twice as high in the 65+ cohort. A prior analysis of NLST data showed an excess of 54 lung cancer deaths (27.5 per 10 000 participants) in the CXR group versus the LDCT group in the under-65 cohort compared with an excess of 29 (40.8 per 10 000 participants) in the 65+ cohort (6). These translate to numbers needed to screen to prevent 1 lung cancer death of 364 and 245, respectively. These numbers suggest that LDCT screening may be more efficient in persons aged 65 years or older than in the younger (aged 55 to 64 years) eligible population. However, if the harms of screening disproportionately affect the older population or the benefits in terms of mortality reduction are attenuated in that population because of several possible factors, the advantage in terms of screening efficiency for the 65+ cohort versus the younger population could be mitigated.

We observed a modestly higher false-positive rate in the older cohort than in the younger cohort. Other studies have found a similar increase in the LDCT false-positive rate with age (9, 10). Overall, an additional 671 per 10 000 NLST participants in the 65+ cohort had at least 1 false-positive screening result, and an additional 80 had a subsequent invasive diagnostic procedure, with 29 of these being surgical procedures. This excess, however, should be viewed in the context of the higher rate of screen-detected cancer and the lower number needed to screen in the older cohort. When we examined the number of invasive procedures after a false-positive screening result per lung cancer death averted, where the latter was computed as the excess of lung cancer deaths in the CXR versus LDCT group, we found similar ratios (5.9 [242 / 40.8] in the 65+ cohort vs. 5.9 [162 / 27.5] in the under-65 cohort).

A specific concern of the MEDCAC panel was that elderly patients in the general population might be screened and then would not be able to have curative resection or could have high surgical mortality if they did receive such treatment. This was not seen in the NLST. Among patients with screen-detected cancer, resection rates were similar by age. Five-year overall survival was modestly higher in the younger cohort (64% vs. 55%), and surgical mortality rates were low in both cohorts.

Age-related increases in surgical mortality after lung resection have been reported in the literature. In a study from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, which reflects a cross-section of U.S. hospitals, the risk for inhospital mortality in patients having resection for lung cancer ranged from 2.3% to 4.0% depending on surgical specialty and increased steadily with age, with odds ratios of 1.40, 2.44, and 3.14 for patients aged 51 to 70 years, 71 to 80 years, and 80 years or older, respectively, compared with those younger than 50 years (11). A study that used the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database, which represents surgeries done by dedicated thoracic surgeons primarily at tertiary centers, found odds ratios of 1.84 and 1.23 for surgical mortality and major morbidity, respectively, for each 10-year increase in age; perioperative mortality was 2.2% and major morbidity was 7.9% overall (12).

Other patient-specific variables in addition to age have been reported to affect outcomes of lung resection, including chronic lung disease and other comorbid conditions (12). Because of a possible “healthy volunteer” effect, NLST participants may have had fewer comorbid conditions than the general U.S. population of persons at high risk for lung cancer, which may explain their lower surgical mortality rates and lack of difference between age groups.

To assess the healthy volunteer effect, we analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) by using the tobacco-related questions to identify the NHIS subset meeting the NLST eligibility criteria for smoking history (13, 14). We compared rates of several comorbid conditions that were inquired about in both the NHIS and the NLST. Among those aged 65 to 74 years, NHIS participants had substantially higher rates of emphysema (20.5% vs. 11.1%), heart disease (30.8% vs. 18.1%), and diabetes (25.1% vs. 11.2%). Participants in the under-65 NHIS cohort (aged 55 to 64 years) also had higher rates of these conditions (11.3%, 25.9%, and 21.1% for emphysema, heart disease, and diabetes, respectively, vs. 6.5%, 11.1%, and 9.2%, respectively, in the NLST). Therefore, the NLST probably had a healthy volunteer effect in both the 65+ and under-65 cohorts. Self-selection (among NLST-eligible persons) of healthier or more health-conscious persons for LDCT screening, including those aged 65 years or older, could also occur in the population setting as LDCT disseminates more widely, but the effect may be less pronounced than in the NLST.

In the NLST, we did not find lower surgical resection rates in the 65+ cohort, possibly due to a healthy volunteer effect. The extent, if any, to which resection rates in general population screening will be lower for persons aged 65 years or older compared with younger persons is uncertain, as is the potential effect of any reduction in resection rates on LDCT screening benefit. Although lobectomy is the standard surgical procedure for resection of early-stage lung cancer, other procedures with lower risk in older patients may be more appropriate, including sublobar resections for tumors less than 1 cm in diameter, lobectomy performed by video-assisted thoracoscopy, or stereotactic body (or ablative) radiotherapy for medically inoperable patients (15–21).

A limitation of the NLST is that the upper age limit at randomization was 74 years and was effectively 76 years at the final screening. This precluded an analysis of how persons in their later 70s and 80s fared with LDCT screening. Also, because of small numbers of events, the study had limited statistical power to detect small but potentially clinically important differences by age in complications of diagnostic procedures and postresection mortality.

It is difficult to predict how LDCT screening for lung cancer will disseminate in the Medicare-eligible population, regardless of whether it is covered by Medicare. Its use may spread to persons with little chance of benefit and some chance of harm, although this risk exists for those in younger age groups as well. Going forward, monitoring and assessing the relative performance of LDCT screening in older persons will be critical to more fully understand its risks and benefits when it is done outside the clinical trial setting and to modify recommendations on the basis of the evidence if needed.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: By the National Institutes of Health (U01-CA-80098, U01-CA-79778, N01-CN-25522, N01-CN-25511, N01-CN-25512, N01-CN-25513, N01-CN-25514, N01-CN-25515, N01-CN-25516, N01-CN-25518, N01-CN-25524, N01-CN-75022, N01-CN-25476, and N02-CN-63300).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M14-1484.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol and statistical code: Available from Dr. Pinsky (e-mail, pp4f@nih.gov). Data set: Available upon request at https://biometry.nci.nih.gov/cdas.

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at www.annals.org.

References

- 1.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer VA U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:330–8. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, ten Haaf K, Munshi VN, Jeon J, et al. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:311–20. doi: 10.7326/M13-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MEDCAC Meeting 4/30/ 2014—Lung Cancer Screening with Low-Dose Computed Tomography. Baltimore: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2014. [10 June 2014]. Accessed at www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/medcac-meeting-details.aspx?MEDCACId=68 on. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, Church TR, Fagerstrom RM, Galen B, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology. 2011;258:243–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinsky PF, Church TR, Izmirlian G, Kramer BS. The National Lung Screening Trial: results stratified by demographics, smoking history, and lung cancer histology. Cancer. 2013;119:3976–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Pr; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute. [18 August 2014];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Web site. Accessed at www.seer.cancer.gov on.

- 9.Gohagan J, Marcus P, Fagerstrom R, Pinsky P, Kramer B, Prorok P Writing Committee, Lung Screening Study Research Group. Baseline findings of a randomized feasibility trial of lung cancer screening with spiral CT scan vs chest radiograph: the Lung Screening Study of the National Cancer Institute. Chest. 2004;126:114–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg AK, Lu F, Goldberg JD, Eylers E, Tsay JC, Yie TA, et al. CT scan screening for lung cancer: risk factors for nodules and malignancy in a high-risk urban cohort. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis MC, Diggs BS, Vetto JT, Schipper PH. Intraoperative oncologic staging and outcomes for lung cancer resection vary by surgeon specialty. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1958–63. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozower BD, Sheng S, O’Brien SM, Liptay MJ, Lau CL, Jones DR, et al. STS database risk models: predictors of mortality and major morbidity for lung cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:875–81. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinsky PF, Berg CD. Applying the National Lung Screening Trial eligibility criteria to the US population: what percent of the population and of incident lung cancers would be covered? J Med Screen. 2012;19:154–6. doi: 10.1258/jms.2012.012010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [13 May 2014]. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis on. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kates M, Swanson S, Wisnivesky JP. Survival following lobectomy and limited resection for the treatment of stage I non-small cell lung cancer < = 1 cm in size: a review of SEER data. Chest. 2011;139:491–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mery CM, Pappas AN, Bueno R, Colson YL, Linden P, Sugarbaker DJ, et al. Similar long-term survival of elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with lobectomy or wedge resection within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Chest. 2005;128:237–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cattaneo SM, Park BJ, Wilton AS, Seshan VE, Bains MS, Downey RJ, et al. Use of video-assisted thoracic surgery for lobectomy in the elderly results in fewer complications. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:231–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demmy TL, Curtis JJ. Minimally invasive lobectomy directed toward frail and high-risk patients: a case-control study. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:194–200. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senan S, Paul MA, Lagerwaard FJ. Treatment of early-stage lung cancer detected by screening: surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy? Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e270–4. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70592-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, Michalski J, Straube W, Bradley J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1070–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grills IS, Mangona VS, Welsh R, Chmielewski G, McInerney E, Martin S, et al. Outcomes after stereotactic lung radiotherapy or wedge resection for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:928–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]