Abstract

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is a lethal parasitic disease. In Gansu Province of China, all AE cases reported in literature were from Zhang and Min Counties, the southern part of the province. Here, we report the discovery of nine AE cases and one cystic echinococcosis (CE) case from Nanfeng Town of Minle County, in the middle of Hexi Corridor in west Gansu Province. The diagnosis of these cases were confirmed by serology, histopathology, computed tomography, B-ultrasound, immunohistochemistry method, DNA polymerase chain reaction and sequencing analysis. Because eight of nine AE cases came from First Zhanglianzhuang (FZLZ) village, we conducted preliminary epidemiological analyses of 730 persons on domestic water, community and ecology such as 356 dogs’ faeces of FZLZ, in comparison with those of other five villages surrounding FZLZ. Our studies indicate that Nanfeng Town of Minle County is a newly discovered focus of AE in China as a CE and AE co-epidemic area. Further research of Echinococcus multilocularis transmission pattern in the area should be carried for prevention of this parasitic disease.

Introduction

Echinococcosis is a worldwide, serious zoonosis caused by the larval stages of tapeworms of the genus Echinococcus. Four species of Echinococcus (E. granulosus, E. multilocularis, E. vogeli, E. oligarthrus) are known to be pathogenic and of public health concern [1,2].

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE), a serious disease in humans and animals, is caused by E. multilocularis, and was found many years ago [3]. The metacestode larvae of E. multilocularis are an infiltrating structure consisting of many small vesicles embedded in the stroma of connective tissue. The larvae grow in the liver as a result of the invasion of the surrounding tissues, and are more hazardous than cystic echinococcosis (CE). If left untreated, the mortality rates of AE patients can be as high as 50%-75%[1,4,5]. Diagnosis of AE is supported by the results from imaging studies, histopathology, nucleic acid detection and serology [1,6].

AE is epidemic in the northern hemisphere including central Europe, most area of Russia, western Alaska, the northwestern portion of Canada, the Central Asian republics, northern Japan, and western China [1]. The dynamics of E. multilocularis transmission are complex. The reported definitive hosts include foxes and domestic dogs, wolves and cats [1,7,8]. The main intermediate hosts of E. multilocularis are small mammals [5]. People are usually infected with E. multilocularis by handling infected hosts, or by ingestion of food contaminated with eggs. AE patients are termination of E. multilocularis life cycle, because they are not generally consumed by definitive hosts and protoscolices are rarely observed in alveolar hydatid cyst in patients lesion organ [1].

Regional distributions of AE in China are limited to northwest and northern China including Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Tibet, Sichuan, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, and Heilongjiang Provinces or Autonomous Regions [9]. Human AE is most epidemic in Yili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture of northwest and western areas of Xinjiang, Xiji, Haiyuan and Guyuan Counties of south Ningxia, Ganze and Aba Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures of the eastern Tibetan plateau comprising northwest Sichuan, Yushu and Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures of southwest Qinghai, Zhang and Min Counties of south Gansu [9–11].

The reported AE cases in Gansu Province were all concentrated in Zhang and Min Counties located in southern Gansu. AE in Gansu Province was first described in 1981 [12] and it was confirmed later by seroepidemiology and abdominal ultrasound scan [7]. Detailed studies were carried out in the epidemic area between 1994 and 1997 [13]. Eighty-four AE cases (3%) were identified from 2482 people in Zhang and Min Counties. Risk factors for human AE are poorly understood. Dogs played an important role in AE transmission to humans in this area. The total number of dogs owned over a period of time was shown to be a risk factor [9,13]. The proportion of habitats favorable to the vole (Microtus limnophilus) closely correlated to village AE prevalence rates [14]. Deforestation driven by agriculture results in creation of optimal peri-domestic habitats for rodents and subsequent development of a peri-domestic cycle involving dogs [13].

Minle County located in middle of Hexi Corridor, north slope of the Qilian Mountain, west of Gansu Province, China. Zhao et al surveyed the Minle County population hydatid diseases from 8 towns and the results showed that the prevalence was 0.75% (67/8932) in 2010 [15]. All of the 67 hydatid cases were CE, and AE cases were not found [15]. From the Zhangye People’s Hospital, our collaborators found two AE cases who lived in Nanfeng Town of Minle County in their daily health service. The current collaborative research was undertaken in this area, aiming to quantify human AE prevalence, elucidate the main risk factors and attempt to dissect the transmission ecology.

Materials and Methods

The human study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Board of School of Basic Medical Sciences, Lanzhou University. All participants and guardians provided their written consent to participate in this study. The ethics committees approved this consent procedure.

Study area and communities

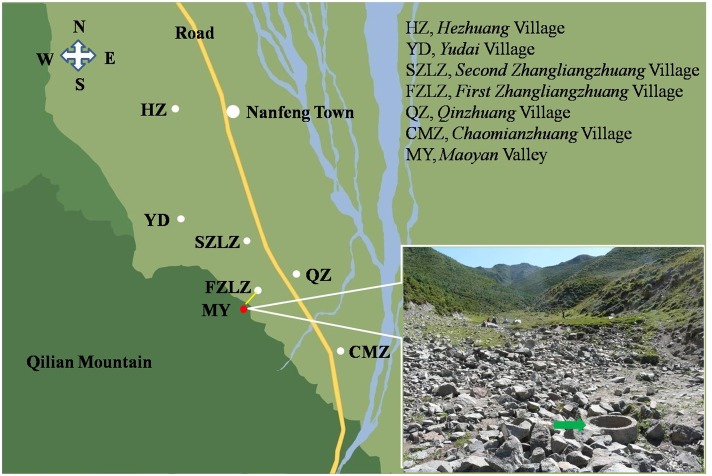

The study was undertaken in six villages including First Zhanglianzhuang (FZLZ), Second Zhanglianzhuang (SZLZ), Hezhuang (HZ), Qinzhuang (QZ), Yudai (YD), and Chaomianzhuang (CMZ) which lie in Nanfeng Town of south Minle County (Fig 1), about 900 kilometers away from Zhang County of south Gansu Province. Through the majestic Qilian Mountain, these villages neighbor with Qilian County of Qinghai Province. The villages ranged in size from 256 to 2650 people with an average population of 1125. All villagers in the six villages were Han Chinese, most of them were subsistence farmers (wheat, barley, rape, potatoes, highland barley, flax, beans, etc.). Every village owns at least one infirmary, and the nearest hospital is in the Nanfeng Town with the distance to the village ranging from 1.5 to 9 km. The maximum distance between the surveyed villages is about 10 km. Livestock comprised sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, yaks and cattle. Domestic dogs were owned in most families. The whole Minle County annual average temperature is about 4.1°C. The annual average rainfall is 351 mm, with a frost-free period of approximately 140 days. The average altitude of the six villages is about 2600 m. The summer of the area is short, warm and a little dry (14–32°C) and the winter is always cold (−8–−28°C).

Fig 1. The location of FZLZ and the other five villages of Nanfeng Town of South Minle County.

Alveococcosis cases diagnosis methods

The hydatid cases medical record databases were searched from the hospitals where they were cared before. AE cases were diagnosed by performing or re-analyzing serodiagnosis, histopathology, computed tomography (CT), B-ultrasound, immunohistochemistry, DNA PCR and sequence technique. The medical record databases of CT images, pathological slice, and B-ultrasound images were examined by the experienced radiographic physicians, pathologists, and sonographers. Paraffin-embedded sample slices were stained by immunohistochemical method with polyclonal antibodies of mice infected by E. multilocularis. DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded samples by using the special kit (Takara Bio.). E. multilocularis mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene was used as the target gene to design the primer based on the reference [16]. The primer EM29F (5’-GATTTGCTGATTTGTTAAAGTTAGTGATC-3’) and EM281R (5’-AGAACTTAAAAACGAATATTTATTGTAACT-3’) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai). The PCR products were sequenced by Beijing Genomics Institute. The sequence alignment was performed by NCBI Blastn.

Human hydatid disease screening and questionnaires

A total of 362 people were voluntarily sampled from six villages which represented approximately 5.36% (362/6749) of the population. A liver scan was performed on each person by an experienced sonographer using a portable scanner (ALOKA-SSC-210) with a 3.0~3.5 MHz transducer. We designed a questionnaire form for registering individuals information including name, age, sex and any previous history of hydatid disease records (usually surgical) and recording information that was relevant to identifying AE risk factors which included fox hunting, fox-skins contact history, dog ownership (number and length of time), dog faeces used as fertilizer or exposure history, feeding dogs with animal organs, eating wild fruit or vegetables, a previous history of AE and living in hydatid disease epidemic areas. A 5-ml venous blood sample was taken from some people with characteristic or query echinococcosis or alveococcosis images or with hydatid disease surgical history. The seral antibody was detected by colloidal gold rapid diagnostic kit as described by the manufacturer (Xinjiang Beithming Biotechnology Development Co., LTD).

Hosts investigation

All the investigated dogs were domestic and we obtained permission from dog owners to use the faeces. The Kato-katz technique [17] was used to detect the tapeworm eggs from 356 dogs. We could not obtain samples from other possible definitive and intermediate hosts of E. multilocularis other than dogs and instead only used pre-existing data supplied by the local Forestry Administration (the wild animal management department) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of Minle County. These data were not published before.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 17.0 was used to analyze questionnaire data for statistical significance of putative human AE ‘risk factors’ (Chi-Square-test).

Results

Nine AE cases and one CE case were found in the area

Eight cases who had been diagnosed as hydatidosis in the local hospitals and treated by surgeries before were found by our questionnaire. After we re-analyzed the eight cases medical record databases, and with the addition of serodiagnosis, immunohistochemistry, DNA PCR and sequence technique, we confirmed that all the eight cases were infected by E. multilocularis. Two new hydatid cases were discovered by our B-ultrasound screen from 362 volunteers. One case image suggested AE diagnosis, and the serum E. multilocularis antibody was also positive. Another case image suggested CE diagnosis, and the serum E. granulosus antibody was positive, but the E. multilocularis antibody was negative. Thus, we found nine AE cases and one CE case in the area. The diagnostic methods and results for the 9 AE cases are listed in Table 1 and Fig 2.

Table 1. The diagnostic methods for the 9 AE cases.

| Cases | diagnostic methods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sero- diagnosis | Histopath-ology | CT | B-ultrasound | Immunohisto- chemistry | DNA PCR and sequence | |

| 1st Case | + | N | N | + | N | N |

| 2nd Case | + | N | N | N | N | N |

| 3rd Case | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4th Case | + | + | + | + | N | + |

| 5th Case | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6th Case | + | N | N | N | N | N |

| 7th Case | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8th Case | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 9th Case | N | N | + | + | N | N |

N, not done. +, the results support alveococcosis diagnosis.

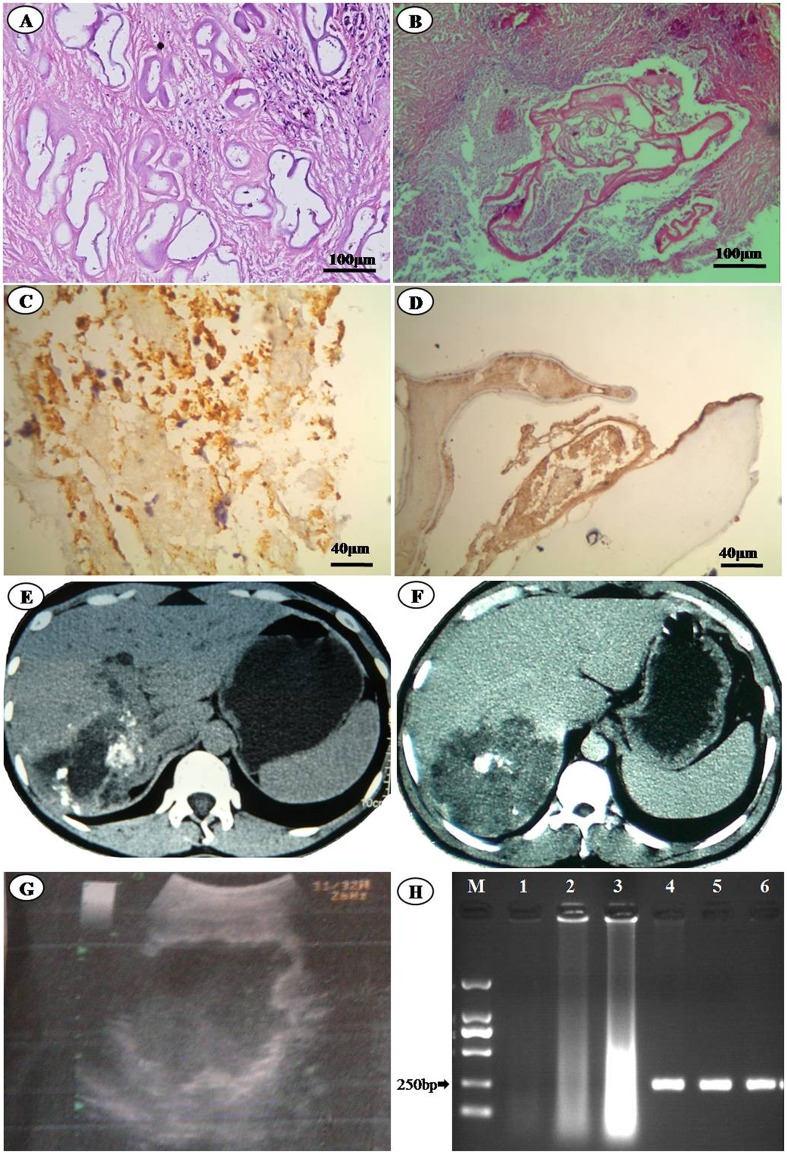

Fig 2. The methods used in AE diagnosis.

(A) and (B) the 5th and 4th cases’ liver samples histopathological images (HE staining, ×100); (C) and (D) the 7th and 8th cases’ liver samples immunohistochemical staining images (×400); (E) and (F) the 7th and 8th cases’ abdominal CT images; (G) the 1st cases’ abdominal B-ultrasound images; (H) DNA extracted from three cases’ paraffin- embedded samples and PCR products (M.5000 bp DNA Marker. Line 1, 2, 3, DNA extracted from the 5th, 7th, and 8th cases paraffin-embedded samples. Line 4, 5, 6, PCR products of the 5th, 7th, and 8th cases’ DNA samples).

The serodiagnostic detections of eight cases (except for 9th case which patient was dead) alive at that time were all positive. HE stained histopathological slices from lesions showed the characteristics of alveolar hydatid cyst (Fig 2A and 2B). The case pathological specimens immunohistochemically stained with alveococcosis mice polyclonal antibodies showed positive results (Fig 2C and 2D). CT and B-ultrasound images of the cases all supported liver AE diagnosis (Fig 2E, 2F and 2G). The PCR products size of E. multilocularis mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene from the paraffin-embedded samples templates was same as initial designed (252 bp) (Fig 2H). The sequence alignment showed 100% similarity with the mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene of 18 E. multilocularis strains in NCBI.

The cases’ distributions and the villagers domestic water investigation

Out of nine AE cases, 8 came from FZLZ village and 1 from YD village, 2 km northwest of FZLZ village (Fig 1). All the cases were adult farmers ranging from 24 to 62 years old. The FZLZ was the nearest village to the Qilian Mountain among the six villages (Fig 1). Only the FZLZ villagers used the domestic water from two wells whose water came from the Maoyan Valley located in Qilian Mountain. The two wells were opened and the water from the upper spring could permeate into the well through the gravel fractures (Fig 1). Around the Maoyan Valley and nearby Qilian Mountain, the vegetation was thriving and the ground and slopes were covered by grass and shrubs (Fig 1). Except for FZLZ villagers, domestic water of other villagers’ came from a reservoir.

Risk factors investigation

Statistical analysis of information in questionnaires were carried out in association with the risk factors of hydatid disease from 730 villagers (10.82% of the population) in the six villages (270 males and 460 females). 113 respondents came from FZLZ village and 617 came from other five villages. The mean age was 44.29 (ranging from 11 to 78 years). There were no significant differences detected between FZLZ villagers and other villagers in habits linked with hydatid disease (P value > 0.05), except that the numbers of relatives with hydatid history of the inquired FZLZ villagers were significantly higher than other villagers (P value < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2. Potential risk factors for human hydatids disease in Nanfeng Town.

People habits were compared between FZLZ and other villages using Chi-Square-test.

| Potential risk factor | FZLZ % | Other villages | P value | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers | 84.07 (95/113) | 85.25 (526/617) | 0.75 | 85.07 (621/730) |

| Fox hunting | 2.65 (3/113) | 2.76 (17/617) | 0.95 | 2.74 (20/730) |

| Contact fox skins | 5.31 (6/113) | 2.92 (18/617) | 0.19 | 3.29 (24/730) |

| Wild vegetables | 41.59 (47/113) | 32.25 (199/617) | 0.053 | 33.70 (246/730) |

| Vegetable garden | 69.91 (79/113) | 69.69 (430/617) | 0.84 | 69.73 (509/730) |

| Dog ownership | 67.26 (76/113) | 61.43 (379/617) | 0.24 | 62.33 (455/730) |

| Dog faeces as fertilizer | 12.39 (14/113) | 18.96 (117/617) | 0.09 | 17.95 (131/730) |

| Sheep ownership | 69.03 (78/113) | 70.02 (432/617) | 0.83 | 69.86 (510/730) |

| Sheep liver feed dog | 14.16 (16/113) | 9.24 (57/617) | 0.11 | 10.0 (73/730) |

| Relatives with hydatid history | 23.89 (27/113) | 6.32 (39/617) | <0.05 | 9.04 (66/730) |

Possible AE hosts investigation

No tapeworm egg was found from 356 dogs’ faeces by using Kato-katz technique. The geographic diversity in Minle County provides good natural conditions for wildlife and the area has a variety of wild species including about 58 kinds of mammals species, 142 kinds of birds species and 13 kinds of amphibians and reptiles species. Besides the dogs, other possible definitive hosts of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis are Vulpes vulpes, Canis lupus, Cuon alpinus. Many villagers had occasionally seen the red fox in nearby areas in winter. Rodents are the primary intermediate hosts of E. multilocularis[1]. There are several rodents including Ochotona thomasi, Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Cricetulus migratorius, Microtus irene, Microtus oeconomus, Marmota himalayana in the area. The dominant species of wild rodents is O. thomasi and the dominant species in residential areas is M. musculus. The other wild herbivores of Lepus oiostolus and Lepus capensis in the area can also serve as possible intermediate hosts of E. multilocularis [18–23].

Discussion

Nanfeng Town of Minle County in west Gansu Province is a newly discovered area of E. multilocularis prevalence in China

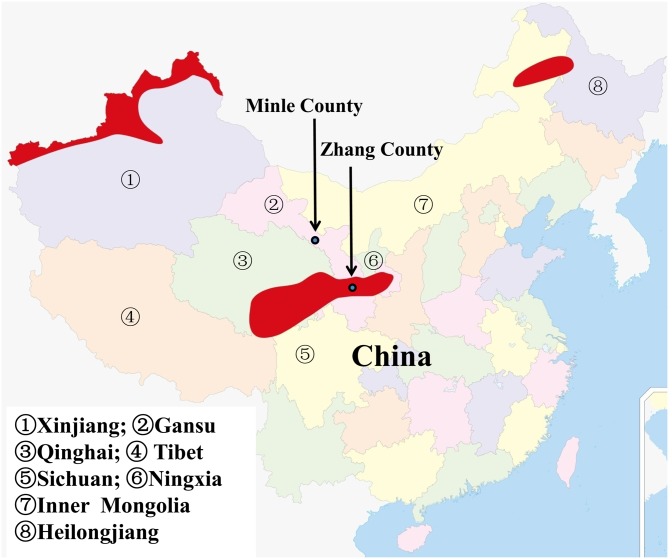

The previous known areas of AE in Gansu Province were Zhang and Min Counties [7]. In this study, we provide evidence of nine AE cases in Nanfeng Town of Minle County. Except for one case dwelling in YD village, other eight cases lived in FZLZ village. The questionnaires showed that all the cases had never visited the historical foci of Zhang-Min County before. Moreover, Nanfeng Town is situated in the skirt of the Qilian Mountain and close to Tibetan plateau foci of Qinghai. Its geographical location, the altitude and cold climatic conditions make the area suitable for E. multilocularis endemicity. Nanfeng Town of Minle County is a newly discovered focus of AE in China (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Epidemiology of human AE in China, and the location of Minle County and Zhang County in China.

The major epidemic regions of human AE in China (the red areas). Minle County locates in west Gansu Province and about 900 km away from Zhang County, and outside of the red areas. This figure is similar but not identical to the image which was published by Craig [9].

The local AE transmission dynamics analysis

The transmission pattern of E. multilocularis includes both the sylvatic cycle and the synanthropic cycle [11]. The sylvatic cycle is the main transmission pattern of E. multilocularis in Europe, Japan, and North America [24,25]. However, in China, epidemiological studies generally indicated that the synanthropic cycle, involving dogs, seemed to be the main transmission route to humans [8,9,11,26]. In this study, we did not detect significant differences regarding dog ownership between the participants screened in FZLZ, and those of other villages, and did not found taeniid egg in 356 dogs’ faeces. Furthermore, we found that only the domestic water of the FZLZ was different from other villages. The government has established wildlife sanctuaries in those mountains, which provides good natural conditions for wildlife. The data, provided by the local Forestry Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of Minle County, indicated that besides domestic dogs, three species of wild animals could act as the possible definitive hosts and other nine species animals could be the possible intermediate hosts. We speculate that red foxes (V. vulpes) and wolves (C. lupus), and the variety of small mammals, which thrive in the mountains which may favor a sylvatic cycle of E. multilocularis transmission possibly, and it needs a further confirmation. The vegetation of grass and shrubs around the Maoyan Valley and nearby Qilian Mountain provides a suitable habitat for wildlife especially foxes (Fig 1). Considering the facts that the distance of other five villages to the FZLZ village are very near, and all natural conditions are similar except the domestic water source, and the morbidity of AE is so different, the possible explanation is that the definitive host (such as foxes etc.) faeces in the Maoyan Valley can be washed into the well possibly and be a source of E. multilocularis infection.

Minle County is a CE and AE co-epidemic area

In most places, human CE and AE are epidemic separately, but they are co-epidemic in only a few other regions, notably eastern Turkey, central Asia and Siberia [27]. The majority of echinococcosis cases in China are caused by E. granulosus[28], but in some areas, CE and AE exist in a co-epidemic phenomenon, and these areas include Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu Provinces and Xin Jiang and Ningxia Autonomous Regions [28–30]. The communities where CE and AE are co-epidemic always suffered from serious echinococcosis, and dogs always were important sources for both E. granulosus and E. multilocularis[11,28]. However in Nanfeng Town, we did not detect that dogs are source for E. multilocularis during the course of our study.

Other investigators reported that the CE occurred in Nanfeng Town with a prevalence rate up to 1.5%[15]. In this study, we found one CE case and nine AE cases in Nanfeng Town. Our finding suggests that Nanfeng Town of Minle County is a CE and AE co-epidemic area and that the area is an important echinococcosis epidemic area. Although we could not confirm that dogs played a role in AE propagation in the local area, other geographical results warned us that dogs in Nanfeng Town should be monitored for E. multilocularis infection in order to prevent AE prevalence.

FZLZ village is centralization cluster of AE cases. The village is situated at the northern foot of Qilian Mountain. Across the Qilian Mountain, the E. multilocularis can be transmitted to the Qinghai Province, and along the Qilian Mountain it can be transmitted to other places of the vast Hexi Corridor. It is important to carry out further research to explore the E. multilocularis transmission pattern in order to develop strategies to prevent the parasitic disease transmitted in the area.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the Nanfeng Town hospital staffs, rural health workers and villagers who participated in the surveys in Nanfeng Town. We are also grateful for Na Xue, Hua Ye, Zhengtao Chen, Zhengdao Wei, Liang Li, and Pengguo Xu who participated in the questionnaires. We thank for George D. Rist, Yanan Su who modified the words of the paper.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Grant number: lzujbky-2014-m02, JH.

References

- 1. Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13: 125–133. 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li T, Ito A, Nakaya K, Qiu J, Nakao M, Zhen R, et al. Species identification of human echinococcosis using histopathology and genotyping in northwestern China. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102: 585–590. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tappe D, Kern P, Frosch M, Kern P. A hundred years of controversy about the taxonomic status of Echinococcus species. Acta Trop. 2010;115: 167–174. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McManus DP, Li Z, Yang S, Gray DJ, Yang YR. Case studies emphasising the difficulties in the diagnosis and management of alveolar echinococcosis in rural China. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4: 196 10.1186/1756-3305-4-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, Bartley PB. Echinococcosis. Lancet. 2003;362: 1295–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kern P. Clinical features and treatment of alveolar echinococcosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23: 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Craig PS, Deshan L, MacPherson CN, Dazhong S, Reynolds D, Barnish G, et al. A large focus of alveolar echinococcosis in central China. Lancet. 1992;340: 826–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moss JE, Chen X, Li T, Qiu J, Wang Q, Giraudoux P, et al. Reinfection studies of canine echinococcosis and role of dogs in transmission of Echinococcus multilocularis in Tibetan communities, Sichuan, China. Parasitology. 2013;140: 1685–1692. 10.1017/S0031182013001200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Craig PS, Echinococcosis Working Group in China. Epidemiology of human alveolar echinococcosis in China. Parasitol Int. 2006;55 Suppl: S221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jiang C. Today's regional distribution of echinococcosis in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2002;115: 1244–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Z, Wang X, Liu X. Echinococcosis in China, a review of the epidemiology of Echinococcus spp. Ecohealth. 2008;5: 115–126. 10.1007/s10393-008-0174-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jiang CP. Liver alveolar echinococcosis in the northwest: report of 15 patients and a collective analysis of 90 cases. Chin Med J (Engl). 1981;94: 771–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Craig PS, Giraudoux P, Shi D, Bartholomot B, Barnish G, Delattre P, et al. An epidemiological and ecological study of human alveolar echinococcosis transmission in south Gansu, China. Acta Trop. 2000;77: 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giraudoux P, Craig PS, Delattre P, Bao G, Bartholomot B, Harraga S, et al. Interactions between landscape changes and host communities can regulate Echinococcus multilocularis transmission. Parasitology. 2003;127 Suppl: S121–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao Zhiying, Wu Tingjun, Ma Sanfu. Epidemiological analysis of hydatid disease of Minle County in Gansu Province. Endemic Diseases Bulletin. 2010;25: 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schneider R, Gollackner B, Edel B, Schmid K, Wrba F, Tucek G, et al. Development of a new PCR protocol for the detection of species and genotypes (strains) of Echinococcus in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38: 1065–1071. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. WHO. Basic Laboratory Methods in Medical Parasitology. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beiromvand M, Akhlaghi L, Fattahi Massom SH, Meamar AR, Darvish J, Razmjou E. Molecular identification of Echinococcus multilocularis infection in small mammals from Northeast, Iran. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: e2313 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang C, He H, Li M, Lei F, Root JJ, Wu Y, et al. Parasite species associated with wild plateau pika (Ochotona curzoniae) in southeastern Qinghai Province, China. J Wildl Dis. 2009;45: 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ito A, Okamoto M, Kariwa H, Ishiguro T, Hashimoto A, Nakao M. Antibody responses against Echinococcus multilocularis antigens in naturally infected Rattus norvegicus. J Helminthol. 1996;70: 355–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanner F, Hegglin D, Thoma R, Brosi G, Deplazes P. [Echinococcus multilocularis in Grisons: distribution in foxes and presence of potential intermediate hosts]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2006;148: 501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liccioli S, Duignan PJ, Lejeune M, Deunk J, Majid S, Massolo A. A new intermediate host for Echinococcus multilocularis: the southern red-backed vole (Myodes gapperi) in urban landscape in Calgary, Canada. Parasitol Int. 2013;62: 355–357. 10.1016/j.parint.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou HX, Chai SX, Craig PS, Delattre P, Quere JP, Raoul F, et al. Epidemiology of alveolar echinococcosis in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, China: a preliminary analysis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94: 715–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eckert J, Conraths FJ, Tackmann K. Echinococcosis: an emerging or re-emerging zoonosis? Int J Parasitol. 2000;30: 1283–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vuitton DA, Zhou H, Bresson-Hadni S, Wang Q, Piarroux M, Raoul F, et al. Epidemiology of alveolar echinococcosis with particular reference to China and Europe. Parasitology. 2003;127 Suppl: S87–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tiaoying L, Jiamin Q, Wen Y, Craig PS, Xingwang C, Ning X, et al. Echinococcosis in Tibetan populations, western Sichuan Province, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11: 1866–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Craig P. Echinococcus multilocularis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16: 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang YR, Craig PS, Sun T, Vuitton DA, Giraudoux P, Jones MK, et al. Echinococcosis in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, northwest China. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102: 319–328. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li T, Chen X, Zhen R, Qiu J, Qiu D, Xiao N, et al. Widespread co-endemicity of human cystic and alveolar echinococcosis on the eastern Tibetan Plateau, northwest Sichuan/southeast Qinghai, China. Acta Trop. 2010;113: 248–256. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang W, Zhang Z, Wu W, Shi B, Li J, zhou X, et al. Epidemiology and control of echinococcosis in central Asia, with particular reference to the People's Republic of China. Acta Trop. 2015;141:235–243 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.