Abstract

Background

AGN-201904-Z is a new, slowly-absorbed, acid-stable pro-PPI rapidly converted to omeprazole in the systemic circulation giving a prolonged residence time.

Aims

To investigate pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of AGN-201904-Z compared to esomeprazole.

Methods

A randomized, open-label, parallel group, investigator-blinded intra-gastric pH study was conducted in 24 healthy Helicobacter pylori negative male volunteers. AGN-201904-Z enteric-coated capsules (600mg/day) or esomeprazole delayed-release tablets (40mg/day) were administered for 5 days. 24-h intra-gastric pH recordings were acquired at baseline, days 1, 3 and 5 with blood levels of omeprazole, AGN-201904-Z and gastrin.

Results

On day 1, median nocturnal pH and proportion of nocturnal time with pH ≥4 and 24-h and nocturnal time pH ≥5 were significantly higher with AGN-201904-Z than esomeprazole. At day 5, 24-h and median nocturnal pH were significantly higher for AGN-201904-Z than esomeprazole (p<0.0001). There was also a marked reduction in periods of nocturnal pH <4.0. AUC of the AGN-201904-Z active metabolite (omeprazole) in the blood was twice that of esomeprazole at day 5.

Conclusion

AGN-201904-Z produced significantly greater and more prolonged acid suppression than esomeprazole and nocturnal acid suppression was more prolonged over all 5 days. AGN 201904-Z should provide true once-a-day treatment and better clinical efficacy compared to current PPIs.

Keywords: Proton pump inhibitor, AGN-201904-Z, Esomeprazole, Acid suppression

Introduction

The healing of acid-related disorders is directly related to the degree and duration of acid suppression and the length of treatment.1 The introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in 1989, covalent inhibitors of the gastric H+, K+ ATPase, resulted in a significant improvement in the management of peptic ulcer disease, erosive esophagitis and other acid-related disorders. PPIs produce significantly more effective and prolonged acid suppression than H2-receptor antagonists (H2-RAs) without any evidence of tolerance.2–5 However, despite the advantages of PPI therapy, a significant number of patients with acid-related disorders do not adequately respond to once or even twice daily PPI therapy. In patients with esophagitis, this is related to the severity of esophagitis. Patients with LA grades C and D esophagitis show much lower healing rates (62–84%) than the general gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) population.6 In a clinical trial of 2425 patients, poor healing was seen for both omeprazole and esomeprazole in patients with grades C (30% vs. 13%, respectively) and D (36% vs. 20%, respectively) erosive esophagitis.7 Symptomatic response to PPI is even less. According to another study, only 58% of patients with GERD experienced satisfactory symptom relief with PPIs.8 Symptomatic response is even less for non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (NERD) with a 63% non-response rate in a pooled analysis.9 The disparity between healing and symptom relief may be that the latter requires an intra-esophageal pH of ~ 5.0.10 A suboptimal symptomatic response to PPI therapy commonly leads the physician to double the PPI dose, the first dose to be before breakfast and the second before dinner.11

The pharmacokinetic properties, namely a short plasma half-life, of the currently available PPIs are not ideal for rapidly and reliably producing prolonged acid suppression. This is especially true for the nocturnal time period. These are pro-drugs and require an acid environment for conversion to the active moiety and the presence of actively acid secreting pumps for covalent binding of the drug which leads to inhibition of acid secretion. Since the PPIs all have similar plasma half-lives or residence time above threshold, namely between 1 and 2h, any proton pumps synthesized or activated after the plasma level of the PPI falls below threshold will not be blocked from secreting acid.12 Thus, the currently marketed acid-protected PPIs cannot control acid secretion over the complete 24-h period with a single or dual dose. This is because pumps which are newly synthesized or activated after the plasma level of the PPI falls below threshold will not be inhibited.

Some 15–20% of patients with GERD require twice-daily maintenance dosing to achieve a satisfactory clinical response.13 Apart from GERD patients, there are several other disease groups with unmet needs. These include the management and prevention of non-variceal upper GI bleeding, stress-related mucosal disease, prevention of NSAID gastropathy, simpler eradication regimens for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection as well as improvement of IV formulations at neutral pH suitable for infusion.14 In addition, patients with non-erosive reflux disease do not respond well to current PPIs, leading to the supposition that their symptoms are not acid-related. However, with improvement in acid control, some of these patients may indeed respond to better control of acid.

The efficacy of a covalent inhibitor of the H+, K+ ATPase, namely a PPI, has usually been related to the area under curve (AUC).12 However, it is more realistic to relate the inhibitor’s effect to the residence time of the drug in the blood above threshold.1 With this concept, a PPI with a longer plasma residence time should produce more prolonged inhibition of proton pumps with consequent greater, more prolonged and consistent acid suppression and potentially more beneficial clinical effects, particularly in patients with nocturnal symptoms.

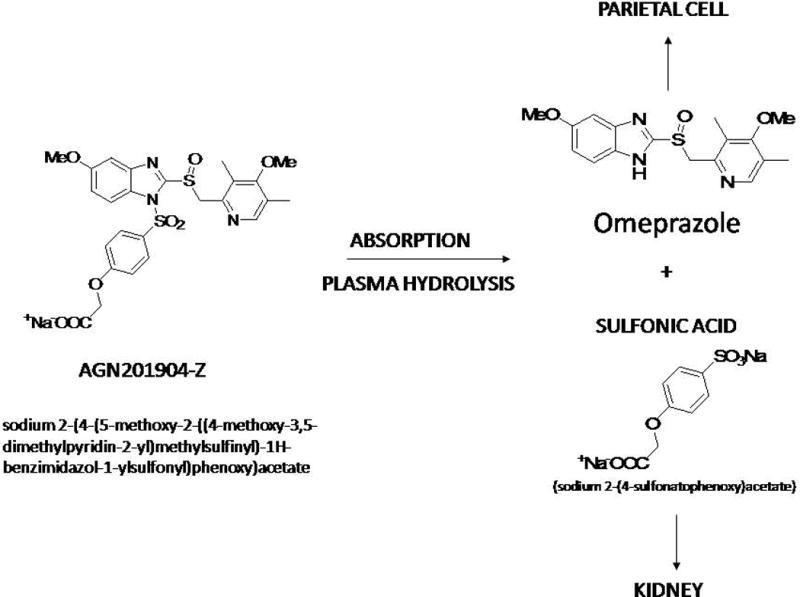

AGN-201904-Z is the sodium salt of AGN-201904, which is an acid-stable prodrug of omeprazole. This drug is designed to provide chemically metered absorption (CMA) of the pro-PPI throughout the length of the small intestine in contrast to the rapid absorption of omeprazole in the upper part of the gut. Once absorbed into the systemic circulation, it is hydrolyzed very rapidly within the blood stream to omeprazole, as has been shown in previous experiments in rats, dogs, and monkeys.15,16 Its structure and principle of design is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Oral dosing with AGN-201904-Z in rats and dogs results in a more prolonged systemic omeprazole concentration-time profile compared to that following dosing with omeprazole and esomeprazole.17,18 Thus, this newly developed CMA-PPI might be expected to provide more effective acid suppression throughout the 24-h period and, in contrast to the existing PPIs, be much more effective through the nocturnal period.

We therefore undertook a phase I, randomized study to compare AGN 201904-Z 600 mg with esomeprazole 40 mg in healthy H. pylori negative male volunteers and compared the pharmacokinetics of these two treatments as well as the resultant intragastric pH after 1, 3 and 5 days of treatment. The 600 mg dose of the prodrug in its current formulation, AGN 201904-Z, provided the equivalent of 50 mg omeprazole in the circulation. This dose would be lower with improved formulation such as a tablet of AGN 201904-Z. It should also be pointed out that to generate an equivalent plasma profile for esomeprazole, approximately 400mg of this esomeprazole would have to be given, with a consequent Cmax of about 10,000 ng/L.

Methods

Subjects

24 healthy male volunteers were recruited for the study by two investigators (RHH and DA) from November 2006 to January 2007. Eligible subjects were H. pylori negative, based on a negative 13C urea breath test (13C UBT; Isodiagnostika, Edmonton, AB, Canada) analyzed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (BreathMat, FinniganMat, Bremen, Germany). All subjects were in good health as determined by medical history, physical examination, laboratory profile, and electrocardiogram. No subject had taken any medication within the preceding 14 days or participated in another drug study within the preceding 30 days, and none was a smoker or had a history of drug or alcohol abuse or drug allergies. Other exclusion criteria were: history of allergy to study medications or their ingredients and inability to tolerate an intragastric pH probe.

Study Design

This was an open-label, randomized, parallel group, investigator-blinded study. Following a screening period of 3–28 days prior to study initiation, subjects were assigned a consecutive number in the order in which they were enrolled into the study according to a random assignment schedule prepared by Allergan. One group received AGN 201904-Z 600mg enteric-coated capsules (5 capsules of 120mg each) once daily or esomeprazole 40 mg delayed release capsule (Nexium® 40 mg, AstraZeneca US) once daily at 7:00 a.m., one hour before a standardized breakfast. The administration of medication was supervised to ensure compliance and was done at McMaster University Health Sciences Centre. All meals were standardized and served at the same times (08:00, 13:00, and 18:00) on each study day. Other food and drink, smoking, and alcohol consumption were prohibited during the entire study period. Genotyping for cytochrome 2C19 (CYP2C19) and 2D6 (CYP2D6) was done at day 6 (Covance Central Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). Each subject gave informed and signed consent prior to participation in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board of McMaster University and Hamilton Health Sciences, Hamilton, Canada.

Pharmacodynamic evaluation

Each participant underwent four ambulatory 24-h intragastric pH-metry measurements during the study: at baseline (day -2) and on days 1, 3 and 5. Briefly, a combination glass electrode, incorporating both pH and reference electrodes (Ingold Biopolar Electrode, MUI Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada) was inserted transnasally and positioned 10 cm below the lower esophageal sphincter, which was located manometrically, and connected to a Medtronic Digitrapper data recorder (Medtronic, Mississauga, ON, Canada) to digitize and store the pH data. Electrodes were calibrated at 20°C using standard buffers to pH 1 and 7 (VWR, WestChester, PA) before each use; recorded pH values were corrected automatically to body temperature (37°C). Intragastric pH values were recorded every 4 seconds by the data recorder for 24 hours. The data were downloaded to a native format Medtronic pH data file before conversion to an ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) file for analysis by an investigator who remained blinded to the treatment schedule.

Each intragastric pH recording was further validated by the investigator. Values within the range 0.8–7.5 were considered as biologically accurate and values exceeding pH 7.5 or lower than pH 0.8 were excluded from analysis. The nocturnal period was defined as from 19:00 to 7:00. For pH-metry analysis, 24-h periods with at least 95% of accurate data were used in the statistical analysis. All valid recordings were then analyzed blindly, using standard, commercially available software (Polygram.Net; Medtronic Digitrapper, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The median pH and percentages of time spent above pH 4 and 5 were determined at baseline (day 0) and at day 1, day 3, and day 5 for the 24-h period as well as for the nocturnal period. The proportion of subjects who had nocturnal acid breakthrough (NAB) episode, defined as the occurrence of intragastric pH <4 for at least 1 h during the nighttime, and the total duration of nocturnal time with pH <4 episodes were also assessed.

Gastrin level

Serum gastrin levels were measured under fasting conditions at baseline, and on day 6 at the time the pH probe was removed. Blood samples were separated and frozen to −20°C and shipped to a central laboratory for serum gastrin measurements (Covance Central Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). All serum gastrin values were measured in a single assay by a sensitive and specific radioimmunoassay. The normal range of serum gastrin for this laboratory is 25–111 ng/l.

Pharmacokinetic Evaluation

Blood samples were collected from each subject for the determination of AGN 201904-Z and omeprazole as well as esomeprazole concentrations in either treatment group respectively. Serial blood samples were collected following the 1st and 5th dose at the following time points: prior to dosing and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours post-dose. Blood AGN 201904-Z, omeprazole, and esomeprazole concentrations were determined using validated liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods. The lower limit of quantitation was 0.5 ng/mL for all analyses. Pharmacokinetic parameters included individual and mean plasma concentrations, peak plasma concentration (Cmax), and, if applicable, time to peak concentration (Tmax), area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to infinity (AUC0-∞), and elimination half time (t1/2). In addition, drug accumulation ratios of Cmax (Day5)/Cmax (Day1) and AUC0-24/AUC0-∞ were estimated. The time that blood omeprazole concentrations were above 50ng/mL was also calculated for AGN 201904-Z group. Similar data were obtained for esomeprazole.

Safety Evaluation

Safety evaluation included a physical examination and monitoring of vital signs. Routine laboratory analyses included hematology, biochemistry and urinalysis. Subjects kept daily diaries to monitor any adverse event including severity and investigators closely assessed the possible relationship of each adverse event to the study drugs.

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was to assess the effects of 5-day dosing of AGN 201904-Z (600 mg daily) and esomeprazole (40 mg daily) on 24-h and nocturnal intragastric pH. Secondary endpoints were to assess the blood concentrations of AGN 201904-Z, its active metabolite, omeprazole, and esomeprazole following 5-days of dosing. Additional endpoints were to assess the safety of the two medications following once-daily oral administration of a 600 mg dose of AGN 201904-Z capsules and 40 mg of esomeprazole for 5 consecutive days.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was done by an investigator who was blind to the recruitment. Variables are expressed as mean or median ± SD when appropriate. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare non-parametric data between the two groups. The 2‐sample t-test was performed to assess between-group differences and the paired t-test for within-group comparisons to baseline when change from baseline was analyzed. Data from all subjects who received at least one dose of study medication were included in the safety analyses. Statistical significance was considered when the p value was less than 0.05. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and analyses were performed using SAS® Version 8.2 and WinNonlin® Version 5.0.1.

A model-independent approach was used to calculate blood pharmacokinetic parameters of AGN 201904-Z, omeprazole, and esomeprazole after single (1st dose) and multiple (5th dose) dose administration, when applicable. The parameters calculated included Cmax, Tmax, AUC0-t, AUC0-24, AUC0-∞, T1/2, oral clearance (CL/F) (AGN 201904-Z only), apparent CL/F (omeprazole only), MRT, and drug exposure ratios, i.e., Cmax (Day 5)/Cmax (Day 1) and AUC0-24 (Day 5)/AUC0-∞ (Day 1).

Results

All twenty-four healthy male volunteers completed the study. Table 1 depicts the baseline characteristics of the study population. There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the two study groups in terms of age, baseline median 24-h or nocturnal pH, mean duration of nocturnal time with pH <4 and gastrin levels. 20 subjects were CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers, 3 were CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers, and 1 was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. For CYP2C19, 17 subjects were extensive metabolizers and 7 were intermediate metabolizers.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study populations in two study groups (n=24). Figures are presented as mean (range) when applicable.

| Total | AGN | Esomeprazole | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 24 | 12 | 12 | NS |

| Age (years) | 22.5 (19–30) | 22.9 (19–30) | 22.0 (20–27) | NS |

| BMI | 25.1 (19–36) | 25.2 (22–36) | 25.0 (20–31) | NS |

| Ethnicity | NS | |||

| Caucasians | 16 | 8 | 8 | |

| Asians | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| West Indian | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Spanish | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Gastrin level | – | 47.0 (31–63) | 46.5 (33–54) | NS |

| Median 24-h pH | – | 1.470.18 | 1.48±0.22 | NS |

| Median nocturnal pH | – | 1.37 ± 0.28 | 1.40 ± 0.28 | NS |

| 24-h % time pH ≥ 4 | – | (8.8 ± 4.2)% | (9.6 ± 3.7)% | NS |

| Nocturnal % time pH ≥ 4 | – | (5.1 ± 4.1)% | (3.5 ± 4.2)% | 0.35 |

| Mean duration of nocturnal time pH <4 | – | 7hr15 | 6hr59 | NS |

| Subjects with >1hr nocturnal time with pH <4 | – | 100% | 100% | NS |

| 24-h % time pH ≥ 5 | – | (8.8 ± 4.2)% | (9.6 ± 3.7)% | 0.62 |

| Nocturnal % time pH ≥ 5 | – | (2.3 ± 3.0)% | (1.5 ± 2.7)% | NS |

BMI: Body Mass Index, NS: Nonsignificant.

Out of 96 intragastric pH recordings from 24 subjects, 2 (one baseline in the esomeprazole group and one day 1 in the AGN 201904-Z group) were considered invalid for analysis. On day 1 (Table 2), the nocturnal median pH was significantly higher for AGN 201904-Z than for esomeprazole and the nocturnal % time with pH ≥ 4 was 1.8 greater for AGN 201904-Z than for esomeprazole. Furthermore, both 24-h and nocturnal % time with pH ≥5 were significantly higher with AGN 201904-Z than with esomeprazole.

Table 2.

Mean (± SD) of median pH and proportion of time with pH ≥4 and ≥5 at baseline, day 1 and 5 by AGN 201904-Z and esomeprazole.

| N | Median pH | % Time pH ≥ 4 | % Time pH ≥ 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 5 | Day 1 | Day 5 | Day 1 | Day 5 | Day 1 | Day5 | ||

| 24-h | AGN 201904-Z | 11 | 12 | 3.91 ± 1.07 | 5.59 ± 0.39 | (49.5 ± 19.0)% | (87.0 ± 10.6)% | (33.5 ± 15.5)% | (72.5 ± 15.2)% |

| Esomeprazole | 12 | 12 | 3.05 ± 1.17 | 4.50 ± 0.68 | (36.5 ± 19.4)% | (57.0 ± 8.9)% | (20.8 ± 13.3)% | (42.1 ± 9.9)% | |

| p – values | 0.07 | < 0.0001 | 0.11 | < 0.0001 | 0.047 | < 0.001 | |||

| Nocturnal | AGN 201904-Z | 11 | 12 | 3.91 ± 0.94 | 5.38 ± 0.61 | (50.3 ± 19.4)% | (82.8 ± 15.7)% | (32.1 ± 14.8)% | 66.0 ± 20.5)% |

| Esomeprazole | 12 | 12 | 2.53 ± 1.08 | 2.95 ± 0.87 | (27.3 ± 18.5)% | (37.7 ± 10.8)% | (12.6 ± 11.1)% | 22.1 ± 9.2)% | |

| p – values | < 0.004 | < 0.0001 | < 0.009 | < 0.0001 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | |||

NS: Nonsignificant

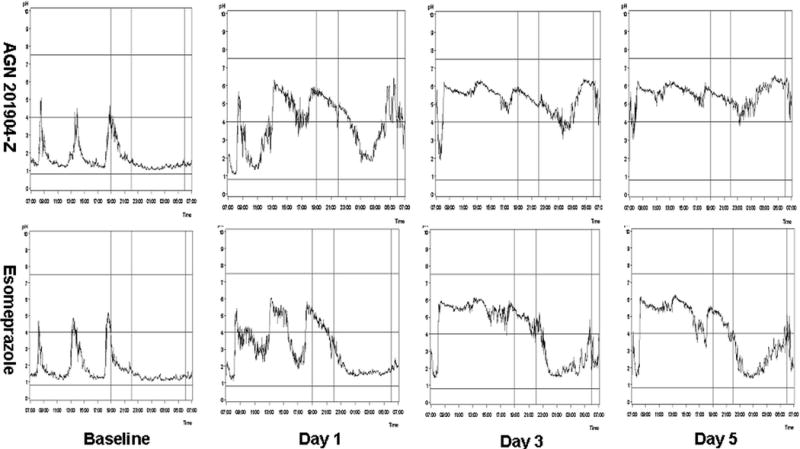

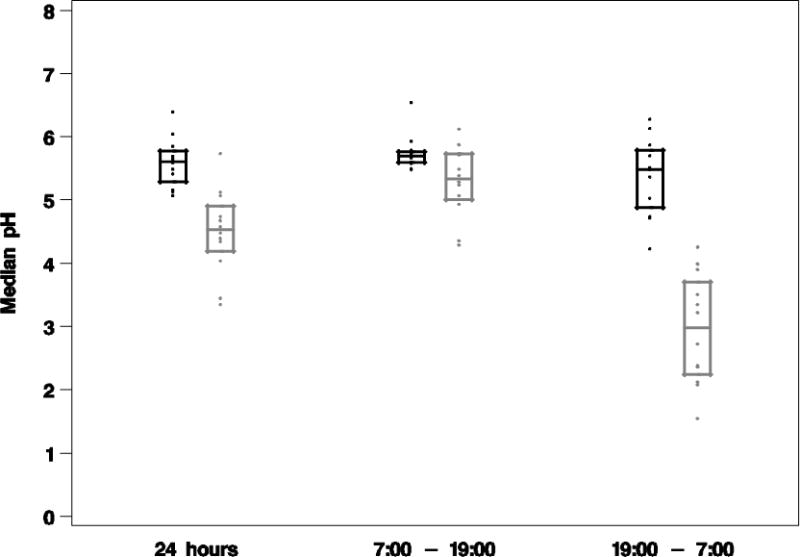

At presumed steady state, on day 5, both 24-h and nocturnal median pH and % time with pH ≥4 and ≥5 were significantly higher for AGN 201904-Z than for esomeprazole (p<0.0001). By day 5, AGN 201904-Z provided 1.5 times higher 24-h % time with pH ≥4 and 1.7 times higher 24-h % time with pH ≥5 as well as 2.2 times nocturnal % time with pH ≥4 and 2.9 times nocturnal % time with pH ≥5 than esomeprazole. Figure 2 shows the median pH profile for AGN 201904-Z as compared to esomeprazole at different stages of study. Already, on day 1, the pH profile following treatment with AGN 201904-Z was superior to that of esomeprazole and by day 3 there was remarkable improvement of nocturnal pH control. By day 5, AGN 201904-Z resulted in a median pH of 5.59 whereas esomeprazole resulted in a median pH of 4.50. Nocturnal median pH was maintained at 5.38 by AGN 201904-Z whereas esomeprazole achieved a median pH of 2.97.

Figure 2.

At day 5, the proportion of subjects with at least 12 hours pH ≥4 during the 24-h period was 100% (12/12) for AGN 201904-Z and 83.3% (10/12) for esomeprazole (p > 0.05). However, 100% (12/12) of the AGN 201904-Z group and 25% (3/12) in esomeprazole group maintained a pH ≥5 (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test) for at least 12 hours in 24-hr.

At day 3, 91.7% (11/12) of subjects in the AGN 201904-Z group had at least 16 h with pH ≥4 compared with 16.7% (2/12) in esomeprazole group (p=0.0006, Fisher’s exact test). At day 5, the proportion was 91.7% (11/12) and 8.3% (1/12) respectively (p<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test).

Nocturnal acid breakthrough (NAB)

On day 1, all subjects had episodes of NAB irrespective of medication (table 1, figure 2). On day 3, 50.0% of the subjects in AGN 201904-Z group showed NAB compared to 91.7% in esomeprazole group (p=nonsignificant, Chi-square). On day 5, the proportion of subjects with NAB was significantly lower in the AGN 201904-Z group (25.0%) versus esomeprazole group (100%) (p=0.0003, Fisher’s exact test). In addition, the mean duration of NAB was significantly less for AGN 201904-Z than esomeprazole at day 1 (2:49 min versus 5:06 min, p=0.005).

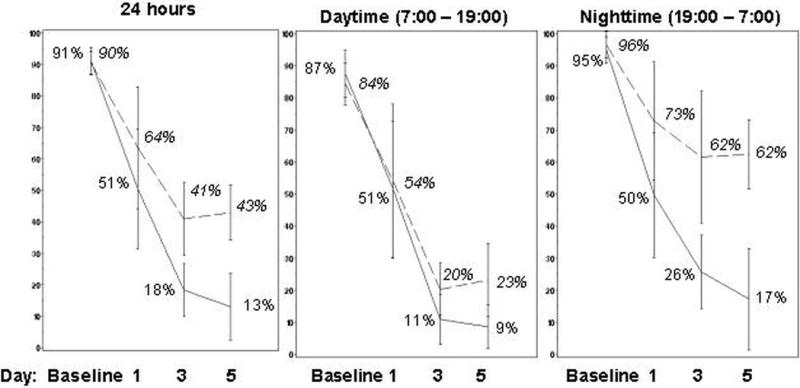

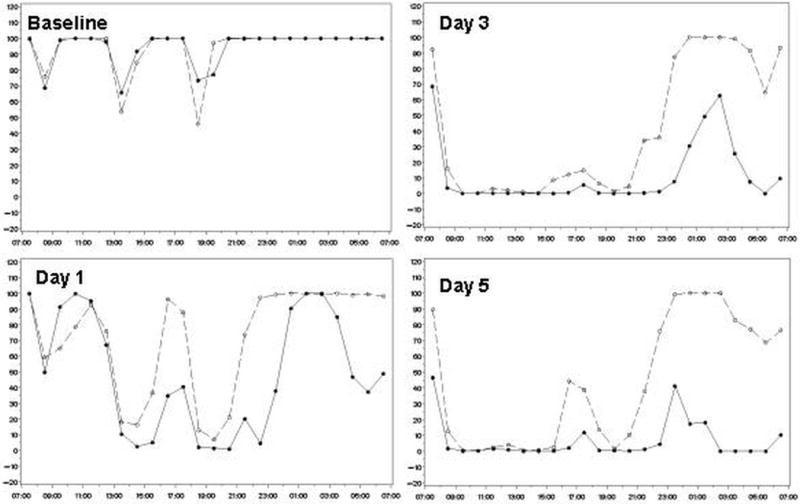

It seems likely that damage to the esophagus occurs when relatively acidic gastric contents are refluxed. Hence, we analyzed the data for the times when intragastric pH was <4.0 and <3.0. The mean percentage of time that intragastric pH was maintained at ≥3 was significantly higher in the AGN 201904‐Z group compared with the esomeprazole group during the nighttime period on days 1, 3, and 5 (66.8%, 85.0%, 90.0 versus 38.0%, 51.1%, and 49.6% respectively, p<0.001). Figure 3 (supplementary materials) depicts the average proportion of time with pH <4 in the two study groups at baseline and at days 1, 3 and 5. AGN 201904-Z provided a better dose-dependent acid suppression over 5 days as compared with esomeprazole. This difference is significant for the nocturnal period where 62% of the esomeprazole treated volunteers had acidity of pH <4.0 as compared to the 17% of the AGN 201904-Z treatment group. Figure 4 presents the median percentage of time with pH <4 for every hour in two study groups. While the baseline acidity for the two groups is comparable, after 3 and 5 days of therapy AGN 201904-Z provided a relatively consistent pH ≥4 while esomeprazole failed to provide such an optimal nocturnal environment with pH ≥4 in the afternoon and at night.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Interindividual Variability

It has always been a puzzling feature of PPI based acid control that there is considerable inter-individual variability. In part, this may be due to variability in absorption and time of stimulation of acid secretion. A prolonged residence time of omeprazole in the blood might reduce this variability. Figure 5 depicts the median pH and 95% confidence interval profile for two study groups at day 5 for 24-hr, diurnal and nocturnal periods. Treatment with AGN 201904-Z was associated with a reduced variability of the pH response as compared to esomeprazole, particularly at night.

Figure 5.

Serum Gastrin

There were no significant differences between the treatment groups. However, in both treatment groups, serum gastrin levels were significantly higher on day 6 after dosing than at baseline. The mean change in serum gastrin levels was 27.0 ng/L (95% CI) in the AGN-201904 group (p=0.008, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and 38.5 ng/L (95% CI) in the esomeprazole group (p=0.016, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

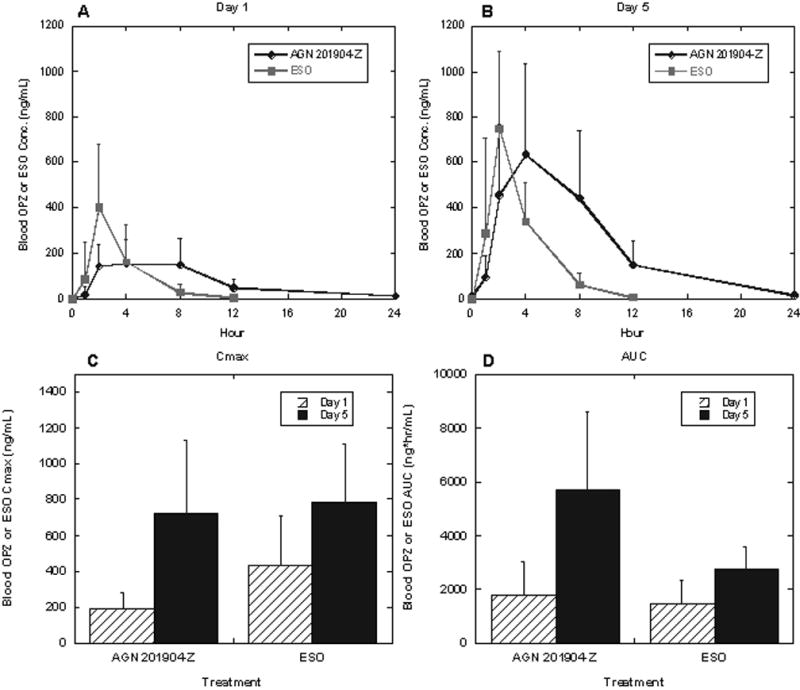

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetic parameters of AGN 201904-Z, omeprazole and esomeprazole following the respective treatments on day 1 and 5 are summarized in Table 3 and those for blood omeprazole levels are summarized graphically in figure 6.

Table 3.

Whole blood pharmacokinetic parameters of AGN 201904-Z 201904, omeprazole, and esomeprazole at Days 1 and 5.

| Treatment | Day | Cmax (ng/mL) |

Tmax (hr) |

AUC0-t (ng·hr/mL) |

AUCa (ng·hr/mL) |

T1/2 (hr) |

CL/Fb (L/hr) |

MRT (hr) |

Day 5/Day 1 Cmax Ratiod,e | Day 5/Day 1 AUC Ratioa,e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGN 201904-Z 600 mg | AGN 201904 | |||||||||

| 1 | 3.40 ± 2.60 | 1.81 ± 0.41c | 3.69 ± 2.95 | NC | NC | NC | NC | 1.44 ± 1.16c | NC | |

| 5 | 4.94 ± 3.73 | 2.18 ± 0.98c | 8.91 ± 6.46 | 11.8 ± 7.08 | NC | NC | NC | |||

| Omeprazole | ||||||||||

| 1 | 188 ± 95.3 | 4.67 ± 2.61 | 1710 ± 1200 | 1790 ± 1240 | 4.53 ± 1.42 | 330 ± 297 | 8.27 ± 2.00 | 3.98 ± 1.57 | 4.05 ± 2.20 | |

| 5 | 726 ± 405 | 4.17 ± 2.48 | 5710 ± 2880 | 5710 ± 2880 | 3.78 ± 1.30 | 82.1 ± 56.9 | 7.28 ± 0.93 | |||

| esomeprazole 40 mg | Esomeprazole | |||||||||

| 1 | 430 ± 278 | 2.17 ± 0.58 | 1280 ± 890 | 1500 ± 840d | 1.33 ± 0.27d | 42.4 ± 38.0d | 3.10 ± 0.78d | 3.32 ± 3.56 | 3.14 ± 3.38d | |

| 5 | 783 ± 324 | 2.25 ± 0.87 | 2710 ± 860 | 2730 ± 860 | 1.99 ± 1.33c | 15.2 ± 5.2c | 3.60 ± 1.55c | |||

| p-value (omeprazole vs. esomeprazole) | 1 | 0.0028 | 0.0054 | NS | NS | <0.0001 | 0.0065 | NA | ||

| 5 | NS | 0.0308 | 0.0055 | 0.0058 | 0.0037 | 0.0018 | ||||

NS: Non significant

Mean ± SD; N=12/treatment; NC = not calculable

AUC0-∞ after 1st dose and AUC0-24 after 5th dose;

Oral clearance for AGN 201904-Z 201904 and esomeprazole; apparent oral clearance for omeprazole

N=11;

N=10

Mean ± SD of within subject ratio

Figure 6.

AGN 201910-Z Pharmacokinetics

Systemic AGN 201904-Z exposure was very low following single (day 1) and repeated (day 5) oral dosing with 600mg AGN 201904-Z. Peak concentrations were less than 4.94 ± 3.73 ng/mL (N = 12), which generally declined to undetectable levels by 8 hours postdose. Hence, exposure to the prodrug is minimal and there is essentially quantitative conversion to omeprazole of the absorbed chemical.

Omeprazole Pharmacokinetics

Omeprazole was the dominant species in blood after AGN 201904-Z dosing. Following single and repeated doses, blood concentrations peaked between 4.67 and 4.17 hours post dose and declined with a mean apparent half-life of 4.53 and 3.78 hours, respectively (N = 12). Systemic omeprazole exposure appeared to increase following repeated dosing as has been described for omeprazole.19 The time that blood omeprazole concentrations were above 50ng/mL increased from 10.5 ± 5.3 hours on day 1 to 18.1 ± 4.1 hours on day 5.

Esomeprazole Pharmacokinetics

Following single and repeated oral dosing with 40mg esomeprazole, blood esomeprazole concentrations peaked at 2.17 and 2.55 hours post dose and then declined log-linearly with a mean apparent half-life of 1.33 to 1.99 hours, respectively. Blood esomeprazole concentrations were generally below the lower limit of quantitation after 12 hours. As seen with omeprazole after dosing with AGN 201910-Z, systemic drug exposure appeared to increase with repeated esomeprazole dosing.

The improvement in pH control on day 1 occurs with a lower Cmax for AGN 201910-Z than for esomeprazole and can be ascribed to the longer dwell time of omeprazole in the blood. After 5-days of dosing, the mean plasma concentration of omeprazole after AGN 201904-Z was higher compared to esomeprazole (mean AUCt 5710 ± 2880 ng.h/ml vs 2710 ± 856 ng.h/ml, respectively) accounting for the increase in pH control. The maximal concentration of omeprazole was not significantly different from esomeprazole (726 ± 405 ng/ml vs 783 ± 324 ng/ml, respectively) as shown in figure 6. This illustrates the advantage of slow absorption of AGN 210904-Z in providing a maintained above-threshold level without an increase in Cmax.

Safety

Both drugs were well tolerated. No serious adverse events were reported during or after the study. A total of 8 minor adverse events was considered to be possibly related to treatment (6 with AGN 201904-Z and 2 with esomeprazole) and 4 were unrelated (one with AGN 201904-Z and 3 with esomeprazole). The most frequent adverse event was headache, which was reported in 3 patients (all with AGN 201904-Z). The other adverse effects included flatulence, abdominal distention, upper abdominal pain, hunger, and epistaxis with AGN 201904-Z and flatulence, dyspepsia, dizziness, and somnolence with esomeprazole. No clinically significant mean changes from baseline were observed for physical examination or routine laboratory assessments, all of which remained normal during and after the study period, nor were such changes significantly different between dosing groups.

Discussion

This is the first randomized, open-label, parallel group, investigator-blinded gastric pH study to evaluate the effect of AGN 201904-Z comparing suppression of gastric acid secretion with esomeprazole. We have shown that AGN 201904-Z significantly improves all indices of acid suppression, including median pH, percentage of time pH ≥4 and ≥5, excursions of pH to < 4.0 and frequency and duration of NAB during a five-day trial of once-daily therapy when compared with esomeprazole in healthy male volunteers.

The superiority of AGN 201904-Z to esomeprazole in acid suppression can be attributed to its pharmacokinetics that, following slow absorption and rapid conversion to omeprazole, provide a longer plasma half-life and dwell time after oral administration once a day. The pharmacokinetic analysis in our study showed that the AUC and T1/2 achieved with AGN 201904-Z are higher than those achieved with esomeprazole. AGN 201904-Z showed a 3.4-fold longer half-life than esomeprazole on day 1 and this was 1.9-fold longer on day 5. Also, the dwell time of omeprazole above a threshold of 50ng/ml from dosing with AGN 201910-Z was prolonged, being also twice that of esomeprazole.

Our group recently compared the efficacy of tenatoprazole 30 mg/d with that of esomeprazole 40 mg/d (n=30) in 30 H. pylori negative healthy male volunteers. In this study tenatoprazole, which has a longer plasma half-life in comparison to other currently marketed PPIs, showed a superior effect in producing longer acid-suppression and a shorter period of NAB.20 The results of our current study also show that AGN 201904-Z produced more prolonged acid suppression and reduced the time with pH <4.0. The mean 24-h and nocturnal percentage of time with pH ≥4 were 87% and 83% respectively after 5-day therapy with AGN 201904-Z. Studies of tenatoprazole and AGN 201904-Z, which both have a long plasma residence time, provide evidence that a PPI with long plasma half-life provides better acid suppression in normal individuals.

By day 5, AGN 201904-Z resulted in a 24 h median pH of 5.59, an acidity level that is well above that required (pH ~5.0) to activate acid sensitive ion channels (ASICs) that are thought to be responsible for pain in the proximal esophagus. Esomeprazole resulted in a 24 h median pH of 4.5, resulting in an acidity level that is above the ASIC activation threshold. Nocturnal pH was maintained at 5.38 by AGN 201904-Z, whereas esomeprazole achieved a median pH of 2.95 which would allow activation of ASICs.10 This consistent control of pH is promising for better symptom relief in patients without endoscopic evidence of erosive esophagitis particularly at night.

Although PPIs are covalent inhibitors, there is remarkable inter-individual variability in the response of intragastric pH. This may be due to differences in timing of peak gastric acid secretion and the presence of the drug in the blood.12 With the long residence time of AGN 201910-Z there should be a decreased inter-individual variability as shown in figure 5.

The dwell time of omeprazole on day 1 at >50ng/ml was 10.5 h compared to <8h for esomeprazole accounting for the superiority of AGN 201904-Z even with a lower Cmax on day 1. By day 5, the dwell time of omeprazole at >50ng/ml was 18.1 h as compared to 8 h for esomeprazole. Nevertheless, the Cmax was approximately equivalent for the two drugs at 5 days, emphasizing the importance of the continuing presence of the drug in the blood for effective intragastric pH control and consistency of response as well as the benefit of a CMA-PPI compared to the PPI itself, where prolonged exposure does not require a higher Cmax.

The more prolonged acid-suppression with AGN 201904-Z suggests that it should provide a better control of nocturnal symptoms with a single dose. AGN 201904-Z provided a percentage of time pH ≥4 more than 2 times greater than esomeprazole during the nighttime period after 5 days of treatment. AGN 201904-Z also resulted in fewer subjects showing NAB compared to esomeprazole after 3 days. It reduced by 75% the number of subjects with NAB at day 5. Moreover, the duration of nighttime with pH ≥4 was also significantly longer with AGN 201904-Z than esomeprazole at day 1, 3 and 5. Therefore, AGN 201904-Z may have a faster onset of action and the potential to control NAB more effectively than esomeprazole, as demonstrated by significantly greater pH control with AGN 201904‐Z starting after the first dose. Furthermore, inter-individual variability was significantly less with AGN 201910-Z for any of the intragastric pH parameters assessed.

The mean apparent half-life of omeprazole from AGN201904‐Z was 3.78 hours, which was twice that of esomeprazole (1.99 hours) after 5days of dosing. The omeprazole Cmax and AUC values were much higher (200-fold and 616-fold, respectively) than those of the parent drug AGN201904-Z, indicating extensive conversion of AGN201904-Z to omeprazole. The mean AGN201904-Z Cmax value was only 1% that of omeprazole and the mean AUC value was only 0.3% that of omeprazole after 5 days of dosing. Hence there is minimal exposure to the pro-drug.

The clinical effect of PPIs is related to the degree of acid suppression and time with pH ≥4 and failure of PPIs in clinical practice has been attributed to a short duration of action although the half life of proton pump itself has been also an arguable point.2–5 Controlling acid effectively over the whole 24-h period due to the longer plasma residence time might offer a promise for better treatment of acid-related disorders, although this needs to be evaluated in a well-designed clinical trial.21–23

Moreover, it has been believed that pepsin activity is dependent to the pH of gastric juice and the highest activity is seen at pH 2 and is detectable to a pH 5, although some minimal activity is still seen in pH 5–7.24,25 As shown in table 2 and figure 2 at day 5 subjects receiving once daily AG- 201904-Z had an reasonable 24-h acid control beyond this level while subjects receiving esomeprazole could not achieve a consistent 24-h acid control especially for the nocturnal period. The potential to provide an environment with minimal or zero pepsin activity might also lead to an improvement in the treatment acid-related disorders.

Moreover, as shown in figure 2, in subjects receiving AGN-201904-Z a marked reduction in the inter-individual variability of pH values was achieved after 5 days. Although, at baseline, mean pH was mostly scattered around pH 1 to 2 it gradually shifted to around pH 6 after 5 days with AGN 201904-Z. However the distribution of pH provided by esomeprazole remained fairly wide and ranged from 1 to 7 after the same period with a considerable number of recordings with low pH values even after 5 days. This difference was more evident during the nighttime period where the distribution of pH provided by AGN-201904-Z still remained higher than pH 4 but pH due to esomeprazole had a nighttime downward peak under pH 2.

The ability of AGN-201904-Z to produce a greater % time with pH >4 was consistently increasing during the study but this was not the case for esomeprazole. Thus, AGN-201904-Z might be not only suitable for short-term therapy based on its early onset of action, but also a good candidate for long-term therapy based on its consistency in dose-related acid suppression.

In conclusion, we have shown more prolonged anti-secretory effect of AGN 201904-Z as compared to esomeprazole. No adverse events were seen. AGN 201904-Z achieved 1.5 times longer 24-hr and 2.2 longer nocturnal time with pH ≥4 than esomeprazole did. It also improved the other indices of acid suppression. Pharmacokinetic data provided the biological explanation for this superiority. Thus, AGN 201904-Z may provide greater clinical efficacy with true once daily dosing, particularly for patients in whom other marketed PPIs are less effective and in whom more effective acid suppression is required. More clinical trials in patients with acid-related disorders are needed to show its efficacy in clinical improvement.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03725.x (this link will take you to the article abstract).

Acknowledgments

(i) This study was funded in full by Allergan, Inc. Irvine CA.

Footnotes

Authors’ conflict of interests

(i) Richard H. Hunt has served as occasional consultant and investigator to Allergan and occasional consultant, speaker, and investigator to AstraZeneca, Altana/Nycomed, Negma-Lerads and TAP.

(ii) David Armstrong has served as investigator to Allergan and consultant, investigator and speaker to AstraZeneca, Altana/Nycomed, Negma-Lerads and Abbott Laboratories.

(iii) George Sachs has served as consultant for Allergan and Negma-Lerads.

(iv) Jai Moo Shin has served as consultant for Negma-Lerads.

(v) Edward Lee is an employee of Allergan Pharmaceutical, Irvine CA.

(vi) Diane Tang-Liu is an employee of Allergan Pharmaceutical, Irvine CA.

Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article:

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Bell NJ, Hunt RH. Progress with proton pump inhibition. Yale J Biol Med. 1992 Nov-Dec;65(6):649–57. discussion 689–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones DB, Howden CW, Burget DW, Kerr GD, Hunt RH. Acid suppression in duodenal ulcer: A meta-analysis to define optimal dosing with antisecretory drugs. Gut. 1987;28:1120–27. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.9.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howden CW, Jones DB, Peace KE, Burget DW, Hunt RH. The treatment of gastric ulcer with antisecretory drugs. Relationship of pharmacological effect to healing rates. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:619–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01798367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burget DW, Chiverton SG, Hunt RH. Is there an optimal degree of acid suppression for healing of duodenal ulcers? A model of the relationship between ulcer healing and acid suppression. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:345–51. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell NJ, Hunt RH. Role of gastric acid suppression in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1992;33:118–24. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, et al. Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:575–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, Maton P, Breiter JR, Hwang C, Marino V, Hamelin B, Levine JG, Esomeprazole Study. Investigators. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar;96(3):656–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.3600_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawley J, Hamelin B, Gallagher E. How satisfied are chronic heartburn sufferers with the results they get from prescription strength heartburn medication? Gastroenterology. 2000;118:A210. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean BB, Gano AD, Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:656–64. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holzer P. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. V. Acid sensing in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007 Mar;292(3):G699–705. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00517.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson P, Hawkey CJ, Stack WA. Proton pump inhibitors. Pharmacology and rationale for use in gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs. 1998;56(3):307–35. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachs G, Shin JM, Howden CW. Review article: the clinical pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:s2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02943.x. 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, Pedersen SA, Liedman B, Hatlebakk JG, Julkonen R, Levander K, Carlsson J, Lamm M, Wiklund I. Continued (5-year) followup of a randomized clinical study comparing antireflux surgery and omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:172–9. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt RH. Review article: the unmet needs in delayed-release proton-pump inhibitor therapy in 2005. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Dec;22(Suppl 3):10–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allergan. Pharmacokinetics and excretion of 14C-AGN 201904-Z following single intravenous and oral administration to Beagle dogs. 2003 Jun; (Unpublished data) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allergan. Collection of samples to access the systemic pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of omeprazole in Cynomologus monkeys. 2003 Sep; (Unpublished data) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allergan. Pharmacokinetics of omeprazole and AGN 201904-Z 201904 following a single intravenous administration of omeprazole and single intravenous and oral administration of AGN 201904-Z to Sprague Dawley rats. 2003 Aug; (Unpublished data) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allergan. Pharmacokinetic screening: Pharmacokinetics of AGN 201904-Z after a single intravenous and oral dosage to male Beagle dogs. 2003 Aug; (Unpublished data) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersson T, Andren K, Cederberg C, Lagerstrom PO, Lundborg P, Skanberg I. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of omeprazole after single and repeated oral administration in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990 May;29(5):557–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt RH, Armstrong D, James C, Chowdhury SK, Yuan Y, Fiorentini P, Taccoen A, Cohen P. Effect on intragastric pH of a PPI with a prolonged plasma half-life: comparison between tenatoprazole and esomeprazole on the duration of acid suppression in healthy male volunteers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1949–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin JM, Choo YM, Sachs G. Chemistry of covalent inhibition of the gastric (H+, K+)-ATPase by proton pump inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7800–11. doi: 10.1021/ja049607w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardner JD, Rodriguez-Stanley S, Robinson M. Integrated acidity and the pathophysiology of GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1363–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouatu-Lascar R, Fitzgerald RC, Triadafilopoulos G. Differentiation and proliferation in Barrett’s esophagus and the effects of acid suppression. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:327–35. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hillman LC, Chiragakis L, Shadbolt B, Kaye GL, Clarke AC. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy and the development of dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Med J Aust. 2004;180:387–91. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen A, Pearson JP, Blackburn A, Coan RM, Hutton DA, Mall AS. Pepsins and the mucus barrier in peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;146:50–7. doi: 10.3109/00365528809099130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03725.x (this link will take you to the article abstract).