Abstract

Background:

Pediatric obesity is one of the predisposing risk factors for many non-communicable diseases.

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to estimate the national prevalence of general and abdominal obesity among Iranian children and adolescents.

Patients and Methods:

This cross-sectional nation-wide study was performed in 30 provinces in Iran among 14880 school students aged 6 – 18 years, selected by multistage random cluster sampling. The World Health Organization growth curve was used to categorize Body Mass Index (BMI). Obesity was defined as BMI equal to or higher than the age- and gender-specific 95th percentile; abdominal obesity was considered as waist-to-height ratio of more than 0.5.

Results:

Data of 13486 out of 14880 invited students were complete (response rate of 90.6%). They consisted of 6543 girls and 75.6% urban residents, and had a mean age of 12.45 (95% CI: 12.40 - 12.51) years. The prevalence rate of general and abdominal obesity was 11.89% (13.58% of boys vs. 10.15% of girls) and 19.12% (20.41% of boys vs. 17.79% of girls), respectively. The highest frequency of obesity was found in the middle school students (13.87% general and 20.84% abdominal obesity). The highest prevalence of general obesity was found in Boushehr (19%) followed by Guilan and Mazandaran (18.3%, 18.3%), while the lowest prevalence was observed in Hormozgan (2.6%). The highest frequency of abdominal obesity was found in Mazandaran (30.2%), Ardabil (29.2%) and Tehran (27.9%). Provinces such as Sistan-Baloochestan (8.4%), Hormozagan (7.4%), and Kerman (11.4%) had the lowest prevalence of abdominal obesity. The Southern and South Eastern provinces had the lowest prevalence of general obesity (2.6% and 5.6%) and abdominal obesity (7.4% and 8.8%). Moreover, the highest prevalence of obesity was found in North and North West Iran by maximum frequency of 18.3% general obesity and 30.2% of abdominal obesity.

Conclusions:

The results showed a high prevalence of general and abdominal obesity among boys living in the Northern provinces of Iran. The present study provides insights that policy makers should consider action-oriented interventions for prevention and control of childhood obesity at national and sub-national level.

Keywords: Overweight, Obesity, Prevalence, Child, Adolescent, Iran

1. Background

Obesity and being overweight are increasing rapidly in the developed and developing countries (1, 2). It is estimated that by 2030 up to 57.8% of the world’s adults would suffer from being overweight or obese (2). Along with adulthood obesity, childhood obesity has also emerged as an epidemic health problem in both developed and developing countries (3, 4). Increase in population size and age and urbanization and a noticeable change in lifestyle had led to an elevated overweight and obesity, especially in developing countries (2). Iran, as a developing country, has been undergoing a rapid phase of urbanization and lifestyle changing especially vis-a-vis nutrition transition in the past few decades, contributing to increasing prevalence of obesity (5, 6). The problem of obesity has not only effected the adults’ life, but the health condition of children. Childhood abdominal obesity would lead not to only obstructive sleep apnea with subsequent increase in the accumulation of carbon dioxide, but an increase in the prevalence of high blood pressure and fatty liver (7, 8). Central obesity could serve as a leading cause of type 1 diabetes and higher levels of LDL-cholesterol (7, 9, 10). Moreover, it can be associated with a low bone mass especially among adolescents and increased risk of allergic diseases in childhood (11-13).

It can be argued that obesity in children and adolescents connects with adiposity in adulthood and consequently might increase the prevalence of several non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases at much earlier stage of life (1, 14). Therefore, it is important to track the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents, as this information is essential for local and public health programming and health policies.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to present the national estimation of general and abdominal obesity among a nationally representative sample of Iranian children and adolescents.

3. Patients and Methods

The data of this study were collected as a part of the “national survey of school student high risk behaviors” (2011 - 2012), as the fourth survey of the school-based surveillance system entitled Childhood and Adolescence Surveillance and PreventIon of Adult Non-communicable Disease (CASPIAN-IV) study. This school-based nationwide health survey was conducted in 30 provinces of Iran. Details on the study protocol have been defined before (15), and herein we report it in brief.

3.1. Study Population and Sampling Framework

The study population consisted of 14,880 school students, aged 6 - 18. They were selected by multistage, cluster sampling method from urban and rural areas of different cities in 30 provinces of the country (48 clusters of 10 students in each province). Stratification was executed in each province according to the residence area (urban/rural) and school grade (elementary/intermediate/high school). The sampling was proportional to size with equal sex ratio, namely, a selection of boys and girls from each province in equal numbers, and the ratios in urban and rural areas corresponded to the population of students in those related sites. In this way, the number of samples in rural/urban areas and in each school grade was divided equally to the population of students in each grade. Cluster sampling with equal clusters was used in each province to scope the required sample size. Clusters concluded the level of schools, including 10 sample units (students and their parents) in each cluster. The maximum sample size that could provide a proper estimate of all risk factors of interest was selected resulting in the sample size of 480 students in each province. Therefore, a total of 48 clusters of 10 subjects in each of the provinces, and a total of 14,880 students were selected.

3.2. Assessment of Anthropometric Measures

Information about weight, height, and waist circumference was recorded by trained health care professionals under standard protocol and by using zero-calibrated instruments. Weight was measured to the nearest 200 g shoeless and lightly dressed condition. Height was measured in standing position, barefoot and shoulders touching the wall and recorded to the nearest 0.2 cm (16). Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight (Kg) divided by height squared (m²). Waist Circumference (WC) was measured by a non-elastic tape and recorded to the nearest 0.2 cm at the end of expiration at the midpoint between the top of iliac crest and the lowest rib in standing position. The World Health Organization (WHO) growth curve was used to categorize BMI [15]. In the current study, overweight and obesity were defined as the age- and gender-specific BMI of 85th -94th percentiles and equal or higher than the 95th percentile, respectively; whereas, abdominal obesity was considered as waist circumference to height ratio (WHtR) to be more than 0.5 (15)

3.3. Statistical Analysis

We used survey data analysis methods in the STATA Corp. 2011, STATA Statistical Software (Release 12. College Station, TX: STATA Corp LP. Package). Moreover, descriptive analysis was used to determine the percentage of abdominal obesity, overweight and general obesity among children and adolescents.

4. Results

The population of this survey consisted of 14,880 children and adolescents (participation rate 90.6%) including 49.2% girls and 75.6% urban inhabitants. Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) of the age was 12.47 ± 3.36 years, without significant difference between boys (12.36 ± 3.40 years) and girls (12.58 ± 3.32 years). Anthropometric characteristics of children and adolescents are presented in Table 1. The Mean ± SD of WHtR and BMI of participants was 0.46 ± 0.06 and 18.85 ± 4.41 (Kg/m²) respectively. In terms of gender, the mean (95% CI) of WHtR of girls was (0.45, CI: 0.45 - 0.45) without significant difference with boys. The mean (95% CI) of BMI in girls (18.9 Kg/m², CI: 18.7 - 19.1) was higher than in boys (18.7 Kg/m², CI: 18.5 - 18.9), but this difference was not significant (P = 0.1).

Table 1. Anthropometric Characteristics of a Nationally Representative Sample of Iranian Children and Adolescents: the CASPIAN-IV Study a.

| Characteristics | Total b | Boys c | Girls c | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 12.47 (3.36) | 12.3 (12.1-12.6) | 12.5 (12.3-12.8) | 0.2 |

| Weight, kg | 42.4 (17.06) | 43.07 (41.9-44.2) | 41.7 (40.7-42.6) | 0.06 |

| Height, cm | 146.99 (18.10) | 148.1 (146.8 - 149.5) | 145.7 (144.6 - 146.8) | 0.005 d |

| Waist circumference, cm | 67.02 (11.96) | 67.8 (67.1 - 68.5) | 66.1 (65.6 - 66.7) | < 0.001 d |

| Waist/height | 0.46 ( 0.06) | 0.46 (0.45 - 0.46) | 0.45 (0.45 - 0.45) | 0.03 d |

| BMI, kg/m² | 18.85 (4.41) | 18.7 (18.5 - 18.9) | 18.9 (18.7 - 19.1) | 0.1 |

a Abbreviations: BMI; Body Mass Index, CI; Confidence Interval, SD; Standard Deviation.

b Values are presented as Mean (SD).

c Values are presented as (Mean, CI).

d P value ˂ 0.05 was considered as significant.

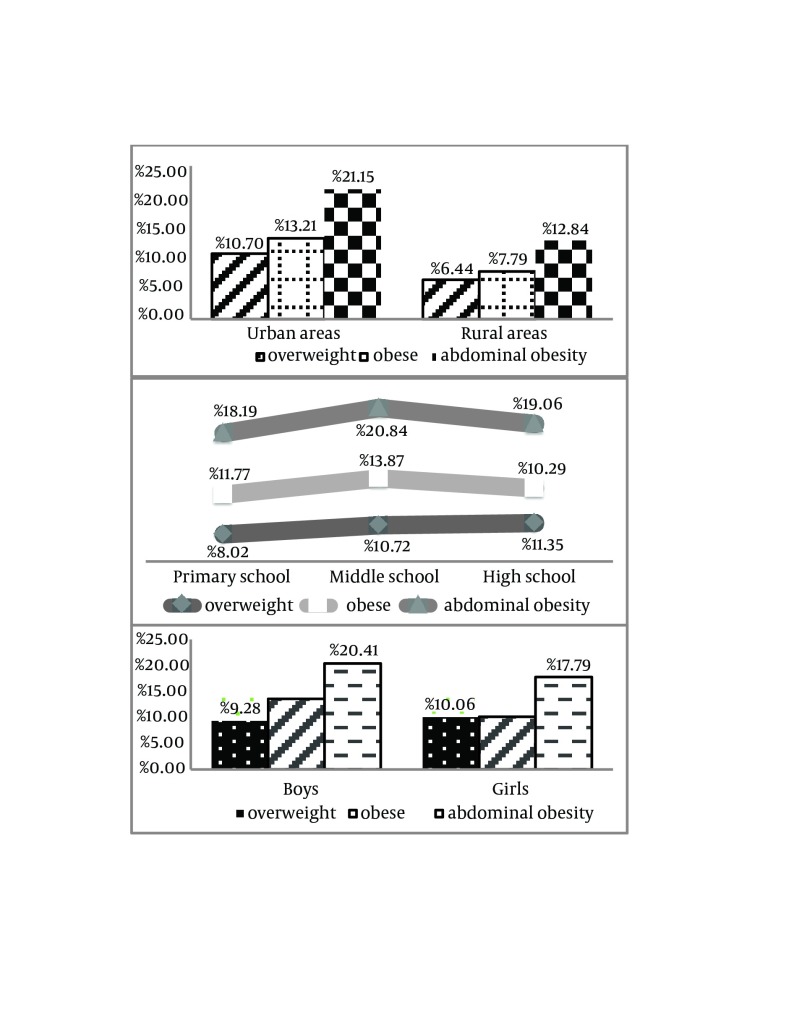

The prevalence of overweight, general and abdominal obesity was 9.66%, 11.89, and 19.12%, respectively. Based on gender difference, however, the prevalence of general and abdominal obesity was significantly higher among boys than girls [13.58% of boys vs. 10.15% of girls for general obesity (P < 0.001) and 20.41% vs. 17.79% for abdominal obesity (P = 0.006) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence of Overweight, General and Abdominal Obesity Among a Nationally Representative Sample of Iranian Children and Adolescents: the CASPIAN-IV Study.

Overall, 10.7% of students in urban areas were overweight, 13.21% were generally obese and 21.15% were abdominally obese. The prevalence of overweight and abdominal obesity was higher among students in urban areas than in rural areas (P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

The prevalence of overweight among children ranged from 8.02% in Primordial school to 11.35% in high school students (P < 0.001). The obesity prevalence increased from Primordial to intermediate school (11.77 to 13.87%) followed by a descending trend up to 10.29% among high school students (P < 0.001). Among the three school levels, the prevalence of general obesity was higher in middle school students. The prevalence of abdominal obesity increased from 18.19% in Primordial school to 20.84% in middle school; and then, it showed a decreasing trend up to 19.06% in high school students (P = 0.07) (Figure 1).

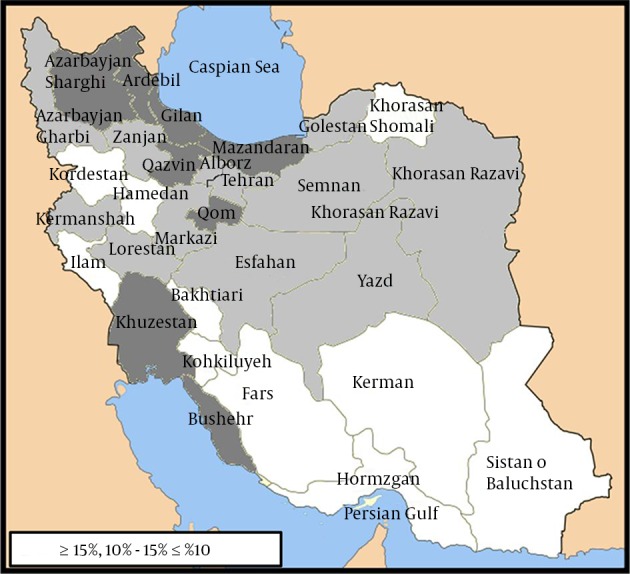

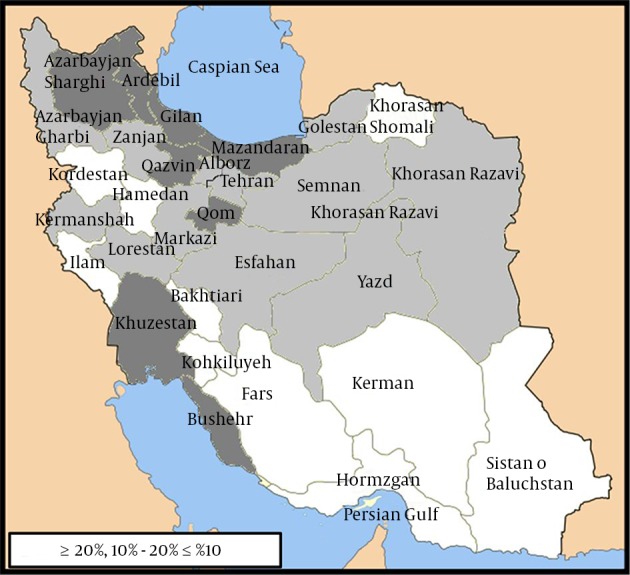

Considerable variations were documented in the prevalence of obesity across the country, the highest prevalence of general obesity was found in Boushehr (19%) followed by Guilan and Mazandaran (18.3%, 18.3%), while the lowest prevalence was observed in Hormozgan (2.6%). The highest frequency of abdominal obesity was found in Mazandaran (30.2%), Ardabil (29.2%) and Tehran (27.9%). Provinces such as Hormozagan (7.4%), Sistan-Baloochestan (8.4%) and Kerman (11.4%), however, showed the lowest prevalence of central adiposity. Across the country, the Southern and South Eastern provinces had the lowest prevalence of general obesity (2.6% and 5.6%) and abdominal adiposity (7.4% and 8.8%). Moreover, the highest prevalence of obesity was found in North and North West of Iran by maximum frequency of 18.3% general obesity and 30.2% of abdominal adiposity (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Prevalence of General Obesity Among a Nationally Representative of Iranian Children and Adolescents in Different Provinces of Iran, 2012: the CASPIAN- IV Study.

Figure 3. Prevalence of Abdominal Obesity Among a Nationally Representative of Iranian Children and Adolescents in Different Provinces of Iran, 2012: the CASPIAN-IV Study.

5. Discussion

This national, cross-sectional study presents data on different BMI categories and waist circumference in a large sample of Iranian children and adolescents aged 6 – 18. The prevalence of general and abdominal obesity was 11.89% and 19.12%. The result of the first national study on obesity in 2008, indicated that based on the Center for Disease Control (CDC), International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) and national cut-offs the prevalence of obesity among 6 -18 year old students was 4.5%, 2.9% and 4.79%, respectively (17). The obesity prevalence in a study conducted by Ziaoddini et al. (18) illustrated that about 3.5% of 6-year-old children were affected by obesity. In the current study, the prevalence of general and abdominal obesity was higher among boys (13.58% and 20.41%, respectively) than girls (10.15% and 17.79%, respectively). In the present study the prevalence of abdominal and general adiposity in three levels of education was 19.36% and 11.97%, respectively with higher frequency of abdominal and general obesity in middle school students. The first national study on the obesity prevalence has illustrated the higher frequency of general obesity among boys than girls (national cut offs: 2.4% vs. 2.39%; CDC: 2.5% vs. 2% and IOTF criteria: 1.6% vs. 1.3%) and the rate of general obesity in three levels of Primordial, middle and high school was 4.4%, 3.1% and 2.6%, respectively with the higher prevalence among Primordial school students (17).

Current results illustrated that the Southern and South Eastern provinces had the lowest prevalence of general and abdominal obesity, while the highest prevalence of obesity was found in Northern provinces with 18.3% of general and 30.2% of abdominal obesity. The results of this study correspond with Ziaoddini et al. (2010) who found the lowest prevalence of obesity among young children of this area (18). In disease mapping study among Iranian population aged 15 - 64, the greatest prevalence of obesity was found in Mazandaran for males 17.8% and 29.8% for females whereas the lowest prevalence was documented in Sistan-Baloochestan and Hormozgan provinces (19). Compared with children and adolescents in the current study, the prevalence of obesity was 22.5% among adults in North Iran and the prevalence of obesity was similarly higher among females than males [30.3% vs. 15.4% (P < 0.01)] (20). Although the frequency of obesity was lower than 10% among children in South Iran, among adults living in this region it has a high frequency of about 50% (58.2% of females vs. 45.3% of males) (21).

The increasing rate in the percentage general obesity among Iranian children and adolescents compared to 2008, provides alarming evidence for health care system in order to pay considerable attention to education, prevention, screening, and control of general and abdominal adiposity from early life. In this regard, Primordial care providers can help preventing the obesity-associated disorders through comprehensive assessment and management of weight disorders among children at national level.

The latest national data from the Middle-East region revealed that the obesity is epidemic in several Middle Eastern countries such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Oman, Turkey, Bahrain and Jordan. Moreover, the results showed that the obesity-associated co-morbidities in these countries are growing as well (22). A report from the United States published in 2012 highlighted that the prevalence of obesity among 2 - 19 year-old boys and girls was 18.6% and 15.0% respectively. In addition, the report also illustrated the dramatic increment in the obesity prevalence from 14.0% to 18.6% among boys, and from 13.8% to 15.0% among girls in 1999 - 2000 and from 2000 to 2009 (23). Among Canadian adolescents aged 12 - 19, the rate of central obesity increased from 1.8% to 12.8% during 1981 – 2009 (24). Similarly a review study by de Moraes et al. (2011) demonstrated that more than 10% of 10 - 19 year-old adolescents suffered from abdominal obesity with its highest prevalence rate among boys (25). Furthermore, findings of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis study among Iranian children and adolescents revealed a lower prevalence of obesity and a higher frequency of overweight among girls with a higher rate of excess body weight among children aged 2 to11 compared to their older counterparts (26). According to the above-mentioned studies, along with the growing prevalence of general and abdominal obesity among Iranian children and adolescents, the similar results have also been observed in other parts of the world in recent years such as the USA, Canada and Middle-Eastern countries (22-24).

The vicious cycle of obesity and metabolic disease could negatively affect the health of the coming generations (27). The most important cause of the higher prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents is related to the lifestyle alterations including rapid changes in food pattern consumption, extra energy intake from fast food and fatty snacks, as well as lower energy expenditure and sedentary lifestyle, family history of obesity, psychological health problems, screen time and sleep patterns (27-31).

Hence, lifestyle modifications and regular physical activities, social education, and nutrition interventions are considered as the most important urgent action strategies to cope with childhood obesity. Furthermore, it is necessary to evaluate the community recourses and identify useful strategies for preventing the obesity epidemic. We need through and helpful information regarding general and central obesity collected by health care professionals, researchers, school health coaches, community organizations, food industries, and government should we aim to modify the environmental inappropriate contributors to extra weight gain. In addition, obesity mapping is a valuable tool that enables us to evaluate and recognize the high-risk regions of abdominal and general obesity, conduct therapeutics, intervention, and finally provide extra educational programs.

One of the limitations of this study is its cross-sectional design, which cannot determine any cause and effect relationship. However, it is possible to generalize the results of this study to rural/urban Iranian students due to the study design and proportional to population sample size calculation and sampling.

In conclusion, findings of this national study emphasizes the significance of the general and abdominal obesity prevalence among Iranian children and adolescents who live in different regions of the country. The results also indicated that the highest frequency of obesity was found in the Northern parts of the country. The high rate of obesity was documented in both genders. The findings of the present study provide insights for policy makers to consider action-oriented interventions for prevention and control of childhood obesity at national and sub-national levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the large team working with this national project, as well as the students, their parents and school principals who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 Suppl 1):S9–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(9):1431–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:62–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James WP. The epidemiology of obesity: the size of the problem. J Intern Med. 2008;263(4):336–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghassemi H, Harrison G, Mohammad K. An accelerated nutrition transition in Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1A):149–55. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azizi F, Ghanbarian A, Momenan AA, Hadaegh F, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, et al. Prevention of non-communicable disease in a population in nutrition transition: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study phase II. Trials. 2009;10:5. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss R, Kaufman FR. Metabolic complications of childhood obesity: identifying and mitigating the risk. Diabetes Care. 2008;31 Suppl 2:S310–6. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels SR. Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33 Suppl 1:S60–5. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kipping RR, Jago R, Lawlor DA. Obesity in children. Part 1: Epidemiology, measurement, risk factors, and screening. BMJ. 2008;337 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YS. Consequences of childhood obesity. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38(1):75–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray CS, Canoy D, Buchan I, Woodcock A, Simpson A, Custovic A. Body mass index in young children and allergic disease: gender differences in a longitudinal study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(1):78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tybor DJ, Lichtenstein AH, Dallal GE, Daniels SR, Must A. Independent effects of age-related changes in waist circumference and BMI z scores in predicting cardiovascular disease risk factors in a prospective cohort of adolescent females. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(2):392–401. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimitri P, Bishop N, Walsh JS, Eastell R. Obesity is a risk factor for fracture in children but is protective against fracture in adults: a paradox. Bone. 2012;50(2):457–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . World Health Organization's Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity, and Health: Turning Strategy into Action, The. World Health Organization; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood_consequences. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelishadi R, Heshmat R, Motlagh ME, Majdzadeh R, Keramatian K, Qorbani M, et al. Methodology and Early Findings of the Third Survey of CASPIAN Study: A National School-based Surveillance of Students' High Risk Behaviors. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(6):394–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Antropometric Standardization Reference Manual Human Kinetics Book. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL. 1988;4(3) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Majdzadeh R, Hosseini M, Gouya MM, et al. Thinness, overweight and obesity in a national sample of Iranian children and adolescents: CASPIAN Study. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34(1):44–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziaoddini H, Kelishadi R, Kamsari F, Mirmoghtadaee P, Poursafa P. First nationwide survey of prevalence of weight disorders in Iranian children at school entry. World J Pediatr. 2010;6(3):223–7. doi: 10.1007/s12519-010-0206-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farhadian M, Moghimbeigi A, Aliabadi M. Mapping the obesity in iran by bayesian spatial model. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(6):581–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veghari G, Joshaghani H, Niknezhad F, Sedaghat M, Hoseini A, Angizeh A, et al. Obesity in the north of Iran (south east of Caspian Sea). Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2010;36(3):100–1. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v36i3.6167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farshidi H, Nikparvar M, Zare S, Bushehri E, Eghbal Eftekhaari T. Obesity pattern in South of Iran: 2002-2006. ARYA Atheroscler. 2010;4(1) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilpi F, Webber L, Musaigner A, Aitsi-Selmi A, Marsh T, Rtveladze K, et al. Alarming predictions for obesity and non-communicable diseases in the Middle East. Public Health Nutrition. 2013;17(05):1078–86. doi: 10.1017/s1368980013000840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009-2010. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen I, Shields M, Craig CL, Tremblay MS. Prevalence and secular changes in abdominal obesity in Canadian adolescents and adults, 1981 to 2007-2009. Obes Rev. 2011;12(6):397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Moraes AC, Fadoni RP, Ricardi LM, Souza TC, Rosaneli CF, Nakashima AT, et al. Prevalence of abdominal obesity in adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12(2):69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelishadi R, Haghdoost AA, Sadeghirad B, Khajehkazemi R. Trend in the prevalence of obesity and overweight among Iranian children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2014;30(4):393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Obesity prevalence in the United States--up, down, or sideways? N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):987–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1009229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hakeem R. Socio-economic differences in height and body mass index of children and adults living in urban areas of Karachi, Pakistan. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55(5):400–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abalkhail B. Overweight and obesity among Saudi Arabian children and adolescents between 1994 and 2000. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8(4-5):470–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelishadi R, Pour MH, Sarraf-Zadegan N, Sadry GH, Ansari R, Alikhassy H, et al. Obesity and associated modifiable environmental factors in Iranian adolescents: Isfahan Healthy Heart Program - Heart Health Promotion from Childhood. Pediatr Int. 2003;45(4):435–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2003.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baygi F, Qorbani M, Dorosty AR, Kelishadi R, Asayesh H, Rezapour A, et al. Dietary predictors of childhood obesity in a representative sample of children in north east of Iran. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2013;15(7):501–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]