Abstract

One of the characteristics of the CNS is the lack of a classical lymphatic drainage system. Although it is now accepted that the CNS undergoes constant immune surveillance that takes place within the meningeal compartment1–3, the mechanisms governing the entrance and exit of immune cells from the CNS remain poorly understood4–6. In searching for T cell gateways into and out of the meninges, we discovered functional lymphatic vessels lining the dural sinuses. These structures express all of the molecular hallmarks of lymphatic endothelial cells, are able to carry both fluid and immune cells from the CSF, and are connected to the deep cervical lymph nodes. The unique location of these vessels may have impeded their discovery to date, thereby contributing to the long-held concept of the absence of lymphatic vasculature in the CNS. The discovery of the CNS lymphatic system may call for a reassessment of basic assumptions in neuroimmunology and shed new light on the etiology of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases associated with immune system dysfunction.

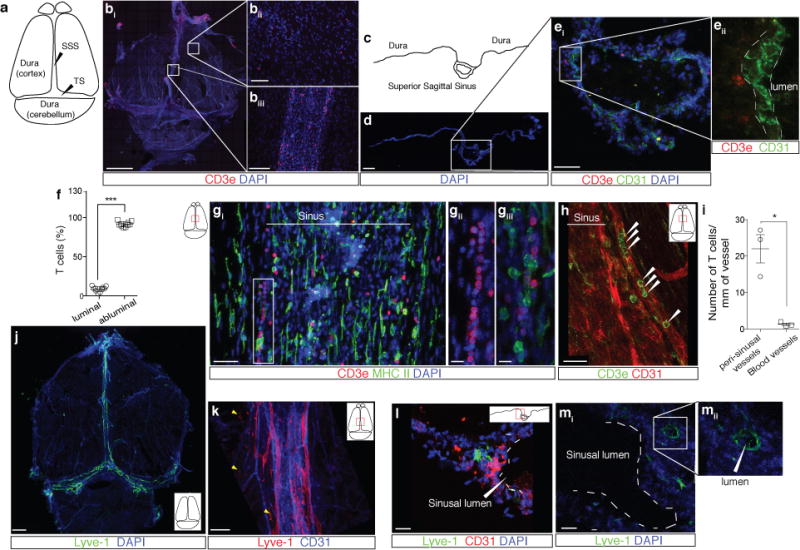

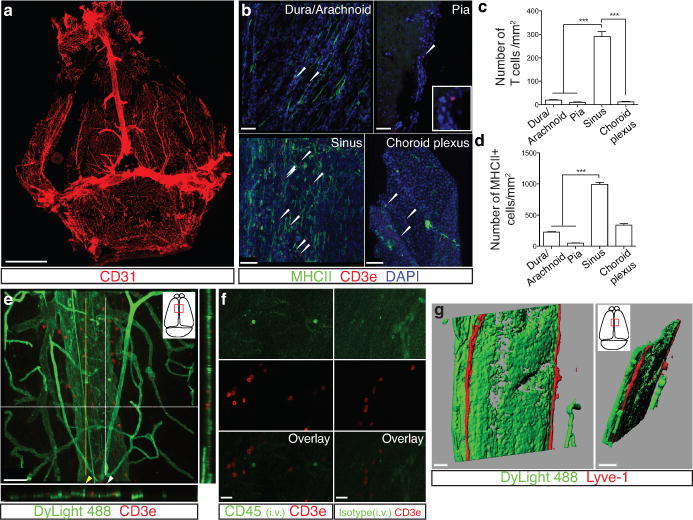

Seeking to identify routes responsible for the recirculation of surveying meningeal immune cells, we investigated the meningeal spaces and the immune cells that occupy these spaces. First, a whole-mount preparation of dissected mouse brain meninges was developed (Fig. 1a) and stained by immunohistochemistry for endothelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 1a), T cells (Fig. 1b) and MHCII-expressing cells (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Labeling of these cells revealed a restricted partitioning of immune cells throughout the meningeal compartments, with a high concentration of cells found in close proximity to the dural sinuses (Fig. 1b; Extended Data Fig. 1b–d).

Figure 1. Abluminal distribution of meningeal T cells and identification of Lyve-1 expressing vessels adjacent to the dural sinuses.

a. Schematic representation of the whole mount dissection of the dura mater. (SSS: Superior Sagittal Sinus; TS: Transverse Sinus) b. Representative images of CD3e labeling in whole mount meninges (scale bar = 2,000 μm). bii–biii. Higher magnification of the boxes highlighted in bi (scale bar = 90μm (bii) or 150 μm (biii)). c. Schematic representation of a coronal section of whole mount meninges. d. Representative image of a coronal section of whole mount meninges (scale bar = 200μm). e. Representative images of CD3e and CD31 immunolabeling in a coronal section of whole-mount meninges. Scale bar = 100 μm. eii. Higher magnification of the box highlighted in ei (scale bar = 30μm). f. Quantification of the percentage of sinusal T cells localized abluminally vs. luminally to the superior sagittal sinus (mean ± SEM; n = 18 fields analyzed from 3 independent animals; ***p=0.0008, Mann-Whitney test). g. Representative images of CD3e and MHCII-expressing cells around the superior sagittal sinus (meningeal cartoons here and elsewhere depict the location of the presented images; scale bar = 50 μm). gii. Higher magnification of the box highlighted in gi (scale bar = 10 μm). giii. High magnification of CD3 and MHCII-expressing cells (scale bar = 10 μm). h. Representative image of CD31 and CD3e labeling around the superior sagittal sinus (scale bar = 30 μm). i. Quantification of the number of T cells per mm of vessels in the perisinusal CD31+ vessels and in similar diameter meningeal blood vessels (mean ± SEM; n = 3 animals; *p=0.05; One-tailed Mann-Whitney test). j. Representative image of Lyve-1 labeling on whole-mount meninges (scale bar = 1,000 μm). k. Higher magnification of Lyve-1 expressing vessels (scale bar = 70 μm); arrowheads indicate Lyve-1+ macrophages. l. Representative images of CD31 and Lyve-1 labeling of a coronal section of the superior sagittal sinus (scale bar = 70 μm). mi. Higher magnification of a Lyve-1 positive vessel presenting a conduit-like structure (scale bar = 50 μm). mii. Higher magnification of the Lyve-1+ vessel presented in panel mi; arrowhead points to the lumen of the vessel.

The dural sinuses drain blood from both the internal and the external veins of the brain into the internal jugular veins. The exact localization of the T lymphocytes around the sinuses was examined to rule out the possibility of artifacts caused by incomplete intracardial perfusion. Coronal sections of the dura mater (Fig. 1c, d) were stained for CD3e (T cells) and for CD31 (endothelial cells). Indeed, the vast majority of the T lymphocytes near the sinuses were abluminal (Fig. 1e). To confirm this finding, mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with DyLight 488 lectin or fluorescent anti-CD45 antibody prior to sacrifice and the abluminal localization was confirmed (Extended Data Fig. 1e, f) and quantified (Fig. 1f). Unexpectedly, a portion of T cells (and of MHCII-expressing cells) was aligned linearly in CD31 expressing structures along the sinuses (only few cells were evident in meningeal blood vessels of similar diameter), suggesting a unique function for these perisinusal vessels (Fig. 1g–i).

In addition to the cardiovascular system, lymphatics represent a distinct and prominent vascular system in the body7,8. Prompted by our observations, the perisinusal vessels were tested for markers associated with lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC). Whole-mount meninges from adult mice were immunostained for the LEC marker, Lyve-1. Two to three Lyve-1-expressing vessels were identified running parallel to the dural sinuses (Fig. 1j, k). Analysis of coronal sections labeled for Lyve-1 and the endothelial cell marker, CD31, revealed that Lyve-1 vessels are located adjacent to the sinus (Fig. 1l) and exhibit a distinct lumen (Fig. 1m). Intravenous injection of DyLight 488 lectin prior to sacrifice confirmed that these Lyve-1+ vessels do not belong to the cardiovasculature (Extended Data Fig. 1g, Supplementary Video 1).

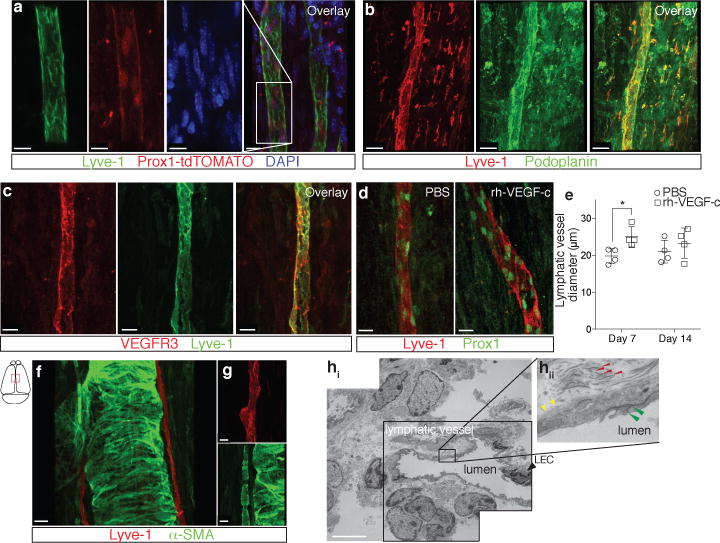

The lymphatic character of the perisinusal vessels was further interrogated by assessing the presence of several classical LEC markers. Expression of the main LEC transcription factor, Prox1, was indeed detectable in the Lyve-1+ vessels using both immunostaining in wild type mice (Extended Data Fig. 2a) and in transgenic mice expressing tdTomato (tdT) under the Prox1 promoter (Prox1tdT; Fig. 2a). Similar to peripheral lymphatics, the Lyve-1 vessels were also found to express podoplanin (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 2b, c) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3) (Fig. 2c, Extended Fig. 2d). Injection of VEGFR3-specific recombinant VEGF-c into the cisterna magna resulted in an increase in the diameter of the meningeal lymphatic vessels, when examined 7 days after the injection (Fig. 2d, e, Extended Data Fig. 2e), suggesting a functional role of VEGFR3 on meningeal LECs. Finally, the presence of LECs in the meninges was confirmed by flow cytometry; a CD45–CD31+podoplanin+ population of cells (LECs) was detected in the dura mater, and is similar to that found in the skin and diaphragm (Extended Data Fig. 3). We identified a potentially similar structure in human dura (Lyve-1+podoplanin+CD68–; Extended Data Fig. 4), but further studies will be necessary to fully assess and characterize the location and organization of meningeal lymphatic vessels in the human CNS.

Figure 2. Molecular and structural characterization of meningeal lymphatic vessels.

a. Representative images of Prox1 expression in the nuclei of Lyve-1+ vessels in the dural sinuses of Prox1tdT mice (scale bar = 10 μm). b. Representative images of podoplanin and Lyve-1 labeling on dural sinuses (scale bar = 40 μm). c. Representative images of VEGFR3 and Lyve-1 staining on dural sinuses (scale bar = 20 μm). d–e. Adult mice were injected i.c.v. (cisterna magna) with 4μg of rhVEGF-c (Cys156Ser) or with PBS. Meninges were harvested 7 and 14 days after the injection. d. Representative images of Lyve-1 and Prox1 labeling of meninges at day 7 after injection (scale bar = 30μm). e. Quantification of the meningeal lymphatic vessel diameter (mean ± SEM; n = 4 mice each group; *p<0.05 Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test). f–g. Representative images of smooth muscle cells (alpha-smooth muscle actin; α-SMA) and Lyve-1 labeling on dural sinuses (scale bars = 50μm (g) or 20μm (h)). h. Representative low power micrograph (transmission EM) of a meningeal lymphatic vessel (scale bar = 5 μm); hii. Higher magnification of the box highlighted in hi; yellow arrowheads – basement membrane; red arrowheads – anchoring filaments (collagen fibers); green arrowheads – cellular junction.

Two types of afferent lymphatic vessels exist – initial and collecting. They differ anatomically (i.e. the presence or absence of surrounding smooth muscle cells and lymphatic valves), in their expression pattern of adhesion molecules7,9,10, and in their permissiveness to fluid and cell entry9. In contrast to the sinuses, the meningeal lymphatic vessels are devoid of smooth muscle cells (Fig. 2f, g). Furthermore, meningeal lymphatic vessels were also positive for the immune-cell chemoattractant protein, CCL2111,12 (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Unlike the blood vessels that exhibit continuous pattern of Claudin-5 and VE-cadherin, the meningeal lymphatic vessels exhibited a punctate expression pattern of these molecules similarly to diaphragm lymphatic vessels9 (Extended Data Fig. 5b–f). Also, expression of integrin-α9, which is characteristic of lymphatic valves13, was not found on meningeal lymphatic vessels, but was readily detectable in the skin lymphatic network (Extended Data Fig. 5g, h). Collectively, these findings indicate that the meningeal lymphatics possess anatomical and molecular features characteristic of initial lymphatic vessels. Furthermore, electron microscopy of whole-mount meninges revealed typical ultrastructural characteristics14 of the lymphatic vessels, which exhibited a non-continuous basement membrane surrounded by anchoring filaments (Fig. 2h, Extended Data 5i).

While possessing many of the same attributes as peripheral lymphatic vessels, the general organization and distribution of the meningeal lymphatic vasculature displays certain unique features. The meningeal lymphatic network appears to start from both eyes and track above the olfactory bulb prior to aligning adjacent to the sinuses (Supplementary Video 2). Compared to the diaphragm, the meningeal lymphatic network covers less of the tissue and forms a less complex network composed of narrower vessels (Extended Data Fig. 5.j; Supplementary Video 2). The vessels are larger and more complex in the transverse sinuses than in the superior sagittal sinus (Extended Data Fig. 5.j). The differences in the vessel network could be due to the environment in which the vessels reside – the high CSF pressure in the CNS compared to the interstitial fluid pressure in peripheral tissues could affect the branching of the vessels and also limit their expansion.

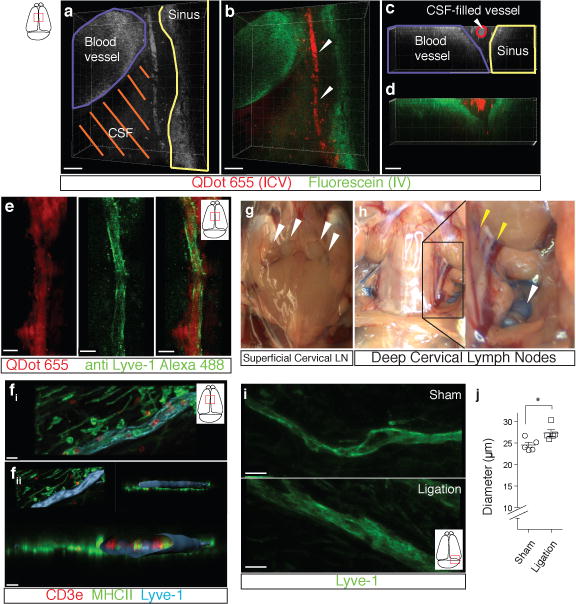

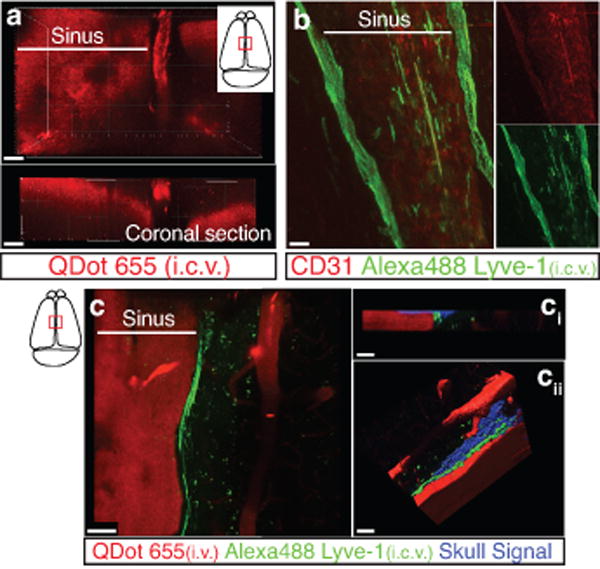

Next, the functional capability of the meningeal lymphatics to carry fluid and cells from the meninges/CSF was examined. Anesthetized adult mice were simultaneously injected with fluorescein i.v. and with fluorescent tracer dye (QDot655) intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.), and then imaged through thinned skull by multiphoton microscopy. Vessels filled with QDot655, but not with fluorescein, were seen aligned along the superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 3a–d; Supplementary Video 3), suggesting that non-cardiovascular vessels drain CSF. This CSF drainage into meningeal vessels may occur in addition to the previously described CSF filtration into the dural sinuses via arachnoid granulations15,16 (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Injection of alexa488-conjugated anti-Lyve-1 antibody i.c.v. labeled the meningeal lymphatic vessels (Extended Data Fig. 6b, c; Supplementary Video 4). Moreover, co-injection of a QDot655 and an alexa488-conjugated anti-Lyve-1 antibody i.c.v. demonstrated that the meningeal lymphatic vessels were indeed filled with QDot655, and thus were draining the CSF (Fig. 3e). Imaging of the QDot655-filled lymphatic vessels revealed a slower flow rate but similar direction of flow in the meningeal lymphatics compared to the adjacent blood vessels (Supplementary Video 5), similar to what is observed outside of the CNS17.

Figure 3. Functional characterization of meningeal lymphatic vessels.

a–d. Representative z-stacks of the superior sagittal sinus of adult mice injected intravenously (i.v.) with fluorescein and intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) with QDot655 (n = 3 mice). a–b Low magnification images are presented showing fluorescein labeling in a meningeal blood vessel and in the superior sagittal sinus. In contrast, QDot655 labeling is prominent in the perisinusal vessel. c–d. Coronal section of the z-stack presented in panels a and b (scale bar = 20μm c–d). e. Representative z-stack of CSF-filled vessel from a mouse injected i.c.v. with both QDot655 and alexa488-conjugated anti-Lyve-1 antibody (n =3 mice; scale bar = 30μm). fi. Representative image of immunolabeling for CD3e and MHCII along with Lyve-1 in the meninges (scale bar = 15μm). fii. Representative image of a 3D reconstruction of the meningeal lymphatic vessels showing the luminal localization of the CD3e and MHCII-expressing cells (scale bar = 20 μm). g–h. Adult mice were injected i.c.v. with 5μl of 10% Evans blue. Superficial cervical lymph nodes (g) and deep cervical lymph nodes (h) were analyzed 30 min after injection (n = 5 mice); white arrowheads indicate the lymph nodes (g–h); yellow arrowheads indicate the Evans blue filled vessels arising near the internal jugular vein into the deep cervical lymph nodes (h). i–j. The collecting vessels draining into the deep cervical lymph nodes (yellow arrowheads in h) were ligated or sham-operated. Eight hours after the ligation, the meninges were collected and immunolabeled for Lyve-1. Representative images of immunolabeling for Lyve-1 in the transverse sinus of ligated and sham-operated mice (i; scale bar = 30 μm). Dot plots represent measurement of the meningeal lymphatic vessel diameters (j; mean ± SEM; n = 5 mice each group from 2 independent experiments; *p=0.031; Mann-Whitney test).

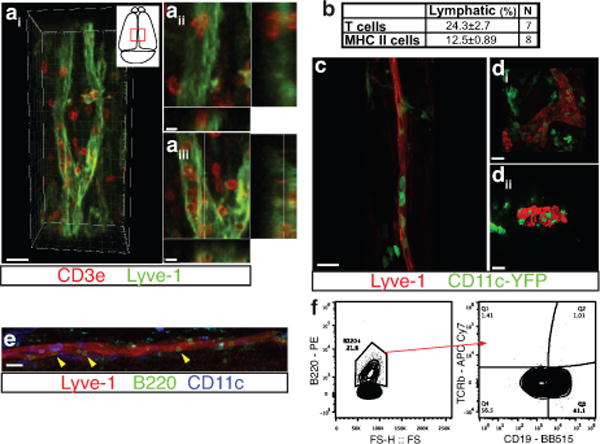

Classic lymphatic vessels, in addition to draining interstitial fluids, allow cells to travel from tissues to draining lymph nodes18. We therefore examined whether the meningeal lymphatic vessels were capable of carrying leukocytes. Immunohistochemical analysis of whole-mount meninges revealed that ~24% of all sinusal T cells and ~12% of all sinusal MHCII+ cells were found within these vessels (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Fig. 7a, b). Moreover, CD11c+ cells and B220+ cells are also found in the meningeal lymphatic vessels of naïve mice (Extended Data Fig. 7c–f).

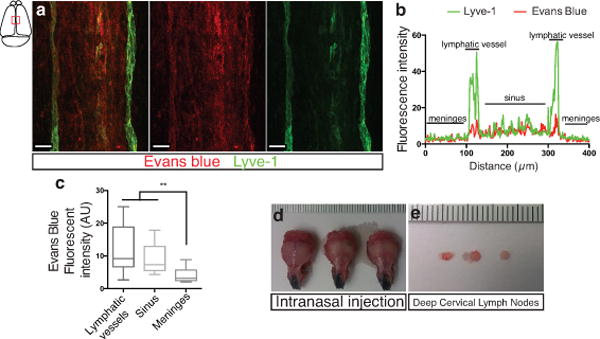

Cellular and soluble constituents of the CSF have been shown to elicit immune responses in the cervical lymph nodes19–22. Their proposed path is via the cribriform plate into lymphatics within the nasal mucosa23. To determine whether meningeal lymphatic vessels communicate with deep cervical lymph nodes directly, we injected mice with Evans blue i.c.v. and examined peripheral lymph nodes for the presence of the dye over a two hour period. Thirty minutes after injection, Evans blue was detected in the meningeal lymphatic vessels and the sinus, as expected (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c), and had also drained into the deep cervical lymph nodes (dCLN) (Fig. 3g, h), but not the superficial lymph nodes. At later time points, Evans blue was also present in the superficial lymph nodes (data not shown). Virtually no Evans blue was seen in the surrounding non-lymphatic tissue at the time points tested. Interestingly, no Evans blue was detected in the dCLN 30 min after direct injection into the nasal mucosa (Extended Data Fig. 8d, e), suggesting that meningeal lymphatic vessels and not nasal mucosa lymphatic vessels represent the primary route for drainage of CSF-derived soluble and cellular constituents into the dCLN during this time frame.

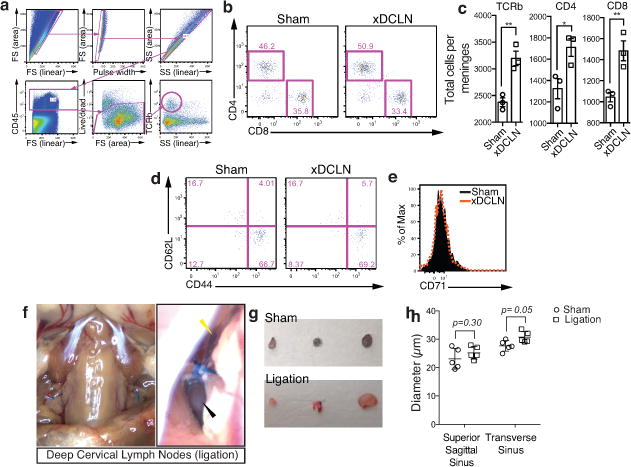

Resection of the dCLN affected the T cell compartment of the meninges, resulting in an increase in the number of meningeal T cells (Extended Data Fig. 9a–e). This presumably resulted from an inability of T cells to drain from the meningeal spaces, consistent with a direct connection between the meninges and the dCLN. To further demonstrate this connection, we ligated the lymph vessels that drain into the dCLNs (Extended Data Fig. 9f), and injected the mice i.c.v. with Evans blue. No accumulation of Evans blue was evident in the dCLN of ligated mice, as opposed to dye accumulation in the sham operated controls (Extended Data Fig. 9g). Moreover, an increase in the diameter of the meningeal lymphatic vessels was observed (Fig. 3i, j; Extended Data Fig. 9h), similar to lymphedema observed in peripheral tissues24. These results further suggest physical connection between the meningeal lymphatic vessels and the dCLN.

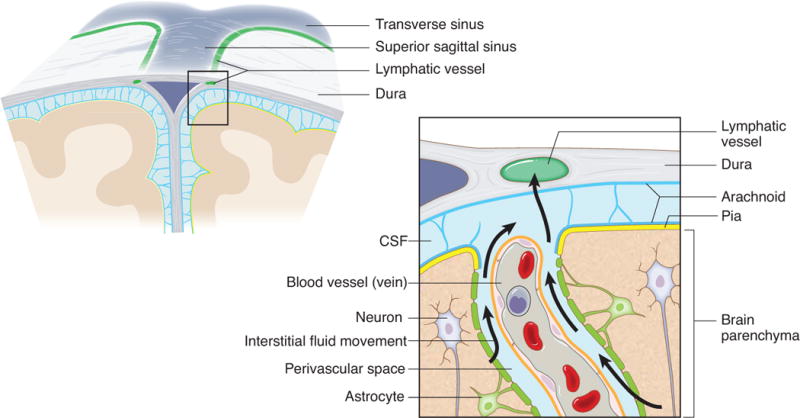

Drainage of the CSF into the periphery has been a subject of interest for decades and several routes have been described regarding how CSF can leave the CNS25,23. The newly discovered meningeal lymphatics are a novel path for CSF drainage and represent a more conventional path for immune cells to egress the CNS. Our findings may represent the second step in the drainage of the interstitial fluid from the brain parenchyma into the periphery after it has been drained into the CSF through the recently discovered glymphatic system26,27 (Extended Data Fig. 10).

The presence of a functional and classical lymphatic system in the CNS suggests that current dogmas regarding brain tolerance and the immune privilege of the brain should be revisited. Malfunction of the meningeal lymphatic vessels could be a root cause of a variety of neurological disorders in which altered immunity is a fundamental player such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and some forms of primary lymphedema that are associated with neurological disorders28–30.

Methods

Animals

Male and female C57Bl/6, NOD.Cd11c-YFP and Prox1tdT mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and were housed in temperature and humidity controlled rooms, maintained on a 12h/12h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00am). All strains were kept in identical housing conditions. All procedures complied with regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Virginia. Only adult animals (eight to ten weeks) were used in this study. Sample size was chosen in accordance with similar, previously published experiment. Animals from different cages in the same experimental group were selected to assure randomization. For all experiments, investigators were blinded from the time of sacrifice to the end of the analysis.

Human samples

Autopsy specimens of human dura including the superior sagittal sinus were obtained from the Departments of Pathology and Neurosurgery at the University of Virginia. All samples are from consenting patients that gave no restriction to the use of their body for research and teaching (through the Virginia Anatomical Board, Richmond, VA). All obtained samples were fixed and stored in a 10% formalin solution for prolonged time periods.

Meninges immunohistochemistry

Mice were euthanized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of Euthasol and perfused with 0.1M of PBS for 5 min. Skin was removed from the head and the muscle were stripped of the bone. After removal of the mandibles and the skull rostral to maxillae, the top of the skull was removed with surgical scissors. Whole mount meninges were fixed while still attached to the skull cap in PBS with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24h at 4°C or in 1:1 ethanol:acetone solution for 20 min at −20°C depending on the antibody. The dura/arachnoid was then dissected from the skullcap. For analysis of the pia mater, brains extracted from the skull were flash frozen, and 40μm-thick transverse sections were sliced using a cryostat (Leica). Choroid plexus was dissected out of the ventricles of non-fixed brain and fixed with 2% PFA in PBS for 24h. For coronal sectioning of whole mount meninges, 100 μl of matrigel (Corning) was injected into the dural sinuses prior to dissection. The meninges (dura mater/arachnoid) were dissected from the skullcap, flash frozen, and 10 μm thick sections were cut using a cryostat, and the slices were placed on gelatin-coated slides.

Whole mounts and sections were incubated with PBS containing 2% of normal serum (either goat or chicken), 1% BSA, 0.1% Triton-X-100 and 0.05% of Tween 20 for 1h at room temperature (RT), followed by incubation with appropriate dilutions of primary antibodies: anti-CD31 (eBioscience, clone 390, 1:100); anti-CD3e (eBioscience, clone 17A2, 1:500), anti-MHC II (eBioscience, clone M5/114.15.2, 1:500), anti-Lyve-1 (eBioscience, clone ALY7, 1:200), anti-Prox1 (Angiobio, 11-002, 1:500), anti-podoplanin (eBioscience, clone 8.1.1, 1:100), anti-VEGFR3 (R&D Systems, AF743, 1:100), anti-αSMA (Sigma-Aldrich, clone 1A4, 1:500), anti-VE-Cadherin (eBioscience, clone BV13 1:100), anti-Claudin-5 (Molecular Probes, 352588, 1:200), anti-CCL21 (R&D Systems, AF457, 1:100), anti integrin-α9 (R&D Systems, AF3827, 1:100), anti-B220 (eBioscience, clone RA3-6B2, 1:100), anti CD11c (eBioscience, clone N418, 1:100) O/N at 4°C in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0,5% Triton-X-100. Whole mounts and sections were then washed 3 times for 5 min at RT in PBS followed by incubation with Alexa-fluor 488/594/647 chicken/goat anti rabbit/goat IgG antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:1000) or PE/Cy3 conjugated streptavidin (eBioscience, 1:1000) for 1h at RT in PBS with 1% BSA and 0,5% Triton-X-100. After 5 min in 1:10 000 DAPI reagent, whole mount and section were washed with PBS and mounted with Aqua-Mount (Lerner) under coverslips. For the pre-absorption experiments, the anti-VEGFR3 and anti-podoplanin antibodies were incubated respectively with recombinant mouse VEGFR3 (743-R3-100, R&D Systems) or recombinant mouse podoplanin (3244-PL-050, R&D Systems) at the concentration ratio of 1:10 O/N at 4°C in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.5% Triton-X-100 prior to staining.

For human samples, formalin-fixed superior sagittal sinuses were dissected in 2 mm thick sections and fixed overnight (O/N) in PBS with 4% PFA. Tissues were then embedded in OCT and 10 μm thick sections were sliced onto gelatin-coated slides on a cryostat (Leica). Antigen retrieval was performed by incubation of the slides for 20 min in sodium citrate buffer pH 6.0 at 80° C. After washing with PBS, endogenous biotins were blocked with a 30 min incubation in PBS with 3% H2O2, then the slides were blocked in PBS containing 2% of normal goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% Triton-X-100 and 0.05% Tween 20 for 1h at RT. Slides were then incubated O/N at 4°C with anti-Lyve-1 (ab36993, Abcam, 1:200), anti-podoplanin (HPA007534, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:200) or anti-CD68 (HPA048982, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:1000) diluted in PBS with 1% BSA and 0.5% Triton-X-100. Sections were then washed 3 times for 5 minutes at RT in PBS followed by incubation with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, 1:1000) for 1h at RT, then for 30 min at RT with ABC kit solutions (VECTASTAIN, Vector Labs). Slides were then incubated with the peroxidase substrate DAB (Sigma-Aldrich) for several minutes, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted in Cytoseal 60 (Thermo Scientific) under coverslips. Nine human samples were labeled and analyzed; the lymphatic structures were identified in two of them.

Image analysis

Images were acquired with a Leica TCS SP8 confocal system (Leica Microsystems) using the LAS AF Software. For the images of the complete whole mount, images were acquired with a 10× objective with 0.25 NA. Other confocal images were acquired using a 20× objective with 0.70 NA or a 40× oil immersion objective with 1.30 NA. All images were acquired with at a 512×512 pixel resolution and with a z-step of 4μm. Quantitative assessments were performed using FIJI software (NIH). Percentage of luminal T cells was determined by counting the number of T cells with luminal localization in the sinuses area. T cell density was established by dividing the number of T lymphocytes by the area of meninges. Prox1-positive cell density was defined by dividing the number of Prox1 nuclei by the area of lymphatic vessels. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Specific statistical tests are presented in the text for each experiment. Outlier samples were eliminated using the Grubbs’ test with a significance level of 0.01 (only for the rh-VEGF-c experiment). No estimate of variation between groups was performed.

Electron Microscopy

Meninges were harvested as previously described and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, and post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1M cacodylate buffer with 0.15% potassium ferrocyanide. After rinsing in buffer, the tissue was dehydrated through a series of graded ethanol to propylene oxide, infiltrated and embedded in epoxy resin and polymerized at 70°C O/N. Semi-thin sections (0.5 microns) were stained with toluidine blue for light microscope examination. Ultrathin sections (80nm) were cut (Integrated microscopy center, University of Memphis) and imaged using the Tecnai TF20 TEM with an AMT XR41 camera (Extended Data Fig. 5i; Integrated microscopy center, University of Memphis) or using the Tecnai F20 TEM with an UltraScan CCD camera (Fig. 2h; Advanced Microscopy core, University of Virginia).

Multiphoton microscopy

Mice were anaesthetized by ketamine/xylazine injection i.p. and injected i.c.v. (into the cisterna magna) with 5μl of QDot655 (Invitrogen) or 5μl of Alexa488-conjugated anti-Lyve-1 antibody (ALY7, eBioscience). Mice were co-injected i.v. with 25μl of 10% fluorescein sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich) or 5μl of QDot655 (Invitrogen). Meningeal lymphatic vessels were imaged through a thinned skull preparation. The core temperature of the mice was monitored and maintained at 37°C. Imaging was performed with a Leica TCS SP8 multiphoton microscopy system (Leica Microsystems) equipped with a Chameleon Ultra II tunable Ti:sapphire laser (Coherent). GFP and QDot655 were excited with an excitation wavelength of 880 nm. Images were obtained using a 25× water immersion objective with 0.95 NA and external HyD non-descanned detectors (Leica Microsystems). Four-dimensional imaging data were collected by obtaining images from the x, y, and z-planes over time. The resulting images were analyzed with Imaris software (Bitplane).

Labeling of the vascular compartment

To assess the abluminal localization of the sinusal T cells, mice were injected i.v. with 10μg of FITC-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody (eBioscience, clone 30-F11) or control isotype 1h prior to euthanasia. To assess that the meningeal lymphatic vessels are not part of the cardiovasculature, mice were injected with 100μl of DyLight 488 Lycopersicon Esculentum Lectin (Vector Laboratories) 5 min prior to euthanasia.

In vivo VEGFR3 activation

Mice were injected i.c.v. with 4μg of rh-VEGF-c (Cys156Ser, R&D Systems) or with PBS. Meninges were harvested 7 and 14 days after the injection.

Evans blue injection and detection

Mice were anaesthetized by ketamine/xylazine injection i.p., and then 5μl of 10% Evans blue (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected i.c.v. into the cisterna magna or intranasally. Thirty minutes after injection, mice were euthanized with CO2 and the CNS draining lymph nodes were dissected for assessment of Evans blue content. The dura mater was also harvested to analyze Evans Blue localization using confocal microscopy. The intensity of the Evans blue was measured using the plot profile function of FIJI.

Flow cytometric analysis of meninges

Mice were perfused with 0.1M PBS for 5min. Heads were removed and skulls were quickly stripped. Mandibles were removed, as well as all skull material rostral to maxillae. Surgical scissors were used to remove the top of the skull, cutting clockwise, beginning and ending inferior to the right post-tympanic hook. Meninges (dura mater, arachnoid and pia mater) were carefully removed from the interior aspect of the skulls and surfaces of the brain with Dumont #5 forceps (Fine Science Tools). Meninges were gently pressed through 70μm nylon mesh cell strainers with sterile plastic plunger (BD Biosciences) to yield a single cell suspension. For lymphatic endothelial cells isolation, meninges (along with diaphragm and ear skin) were digested for 1h in 0.41U/ml of Liberase TM (Roche) and 60U/ml of DNAse1. Cells were then centrifuged at 280g at 4°C for 10 min, the supernatant was removed and cells were resuspended in ice-cold FACS buffer (pH 7,4; 0.1M PBS; 1mM EDTA: 1% BSA). Cells were stained for extracellular marker with antibodies to CD45-PacificBlue (BD Bioscience), CD45-PE-Cy7 or eFluor 450 (eBioscience), TCRβ-Alexa780 (eBioscience), CD4-Alexa488 (eBioscience), CD8-PerCPCy5.5 (eBioscience), CD44-APC (eBioscience), CD62L-PE (eBioscience), CD71-APC (eBioscience), podoplanin-PE (eBioscience), CD31-Alexa647 (eBioscience), B220-PE (eBioscience), CD19-BB515 (BD Bioscience). Except for the lymphatic endothelial cells identification experiment, all cells were fixed in 1% PFA in 0.1M pH 7.4 PBS. Fluorescence data were collected with a CyAn ADP High-Performance Flow Cytometer (Dako) or a Gallios (Beckman Coulter) then analyzed using Flowjo software (Treestar). To obtain accurate cells counts, single cells were gated using the height, area and the pulse width of the forward and side scatter, then cells were selected for being live cells using the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). The cells were then gated for the appropriate markers for cell type (Extended Data Fig. 3,9). Experiments were performed on meninges from n = 3 mice per group. Data processing was done with Excel and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism.

Deep cervical lymph node resection, ligation and sham surgery

Eight-week old mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine, shaved at the neck and cleaned with iodine and 70% ethanol, and an ophthalmic solution was put on the eyes to prevent drying. An incision was made midline 5mm superior to the clavicle. The sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) was retracted, and the deep cervical lymph node was removed with forceps. For the ligation experiment, the collecting lymphatic vessels anterior to the deep cervical lymph nodes were ligated using a nylon suture (9-0 Ethilon black 6”VAS100-4). Sham-operated mice received the incision and had the SCM retracted, but were not ligated or the lymph nodes were not removed. Mice were then sutured and allowed to recover on a heating pad until responsive. Post surgery, mice were given analgesic to the drinking water: 50mg/l for 3 days post surgery and 0.16mg for the next 2 weeks.

Extended Data

Extended Figure 1. Meningeal immunity and lymphatic vessels in the dural sinuses.

a. Representative image of CD31 staining in whole mount meninges (scale bar = 2,000 μm). b. Representative images of T cells (CD3e, arrowheads) in the dura/arachnoid, pia, dural sinuses, and choroid plexus (scale bar = 70 μm). c. Quantification of T cell density in different meningeal compartments (mean ± SEM; n =6 animals each group; ***p<0.001; Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test). d. Quantification of MHCII-expressing cells in different meningeal compartments (mean ± SEM; n = 6 animals each group; ***p<0.001; Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test). e. Adult mice were injected i.v. with 100μl of DyLight 488 lectin 5 min prior to sacrifice to enable labeling of the cardiovascular system. Meninges were harvested and stained with anti-CD3e. Representative orthogonal images of T cell localization in the lumen (white arrowhead) and outside of the sinus (yellow arrowhead; n=2 mice; scale bar = 70 μm). f. Adult mice were injected i.v. with 10μg of FITC-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody or FITC-conjugated isotype antibody. Meninges were harvested one hour after the injection and labeled with anti-CD3e. Representative images of CD3e immunolabeling around dural sinuses are shown. CD45 positive cells do not co-localize with CD3+ cells (a), suggesting an abluminal localization of the later (n = 2 mice each group; scale bar = 20 μm). g. Representative 3D reconstruction of the lymphatic vessels localization around the superior sagittal sinus. Adult mice were injected i.v. with 100μl of DyLight 488 lectin 5 min prior to sacrifice in order to stain the cardiovascular system. Meninges were harvested and labeled with anti-Lyve-1. The lack of lectin staining in the Lyve-1-positive meningeal lymphatic vessels suggests that they are independent of the cardiovascular system (n = 3 mice; scale bars = 50 μm and 120 μm). The mounting of the whole meninges results in the flattening of the sinus, thus it does not appear tubular.

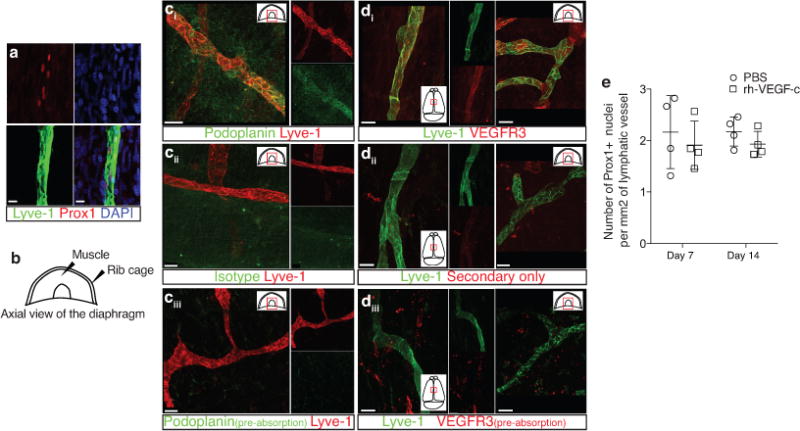

Extended Figure 2. Identification, characterization and validation of the expression of classical lymphatic endothelial cell markers by the meningeal lymphatic vessels.

a. Representative images of Prox1 labeling on meningeal Lyve-1 expressing vessels (n = 3 mice; scale bar = 10 μm). b. Schematic representation of the whole mount dissection of the diaphragm. c. Characterization of the specificity of the podoplanin antibody. Representative images of whole mount diaphragm labeled with anti-Lyve-1 and anti-podoplanin (ci), control isotype (cii) or the anti-podoplanin pre-incubated overnight with a saturated concentration of recombinant podoplanin protein (ciii; scale bar = 20 μm). d. Characterization of the specificity of the VEGFR3 antibody. Representative images of whole mount diaphragm and dura mater labeled with anti-Lyve-1 and anti-VEGFR3 (di), secondary antibody only (dii), or the anti-VEGFR3 pre-incubated overnight with a saturated concentration of recombinant VEGFR3 protein (diii; scale bar = 20 μm). e. Quantification of the number of Prox1+ nuclei per mm2 of lymphatic vessel (mean ± SEM; n = 4 animals each group).

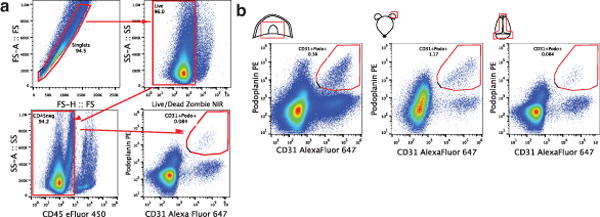

Extended Figure 3. Identification of the meningeal lymphatic endothelial cell population by flow cytometry.

a. FACS analysis of the lymphatic endothelial cells in diaphragm, skin (ear), and dural sinuses. Gating strategy employed to identify lymphatic endothelial cells (CD31+podoplanin+). Lymphatic endothelial cells are identified as singlet, live cells, CD45 negative and CD31+podoplanin+. b. Representative dot plots for lymphatic endothelial cells (CD31+podoplanin+) in the diaphragm, skin, and dura mater of adult mice.

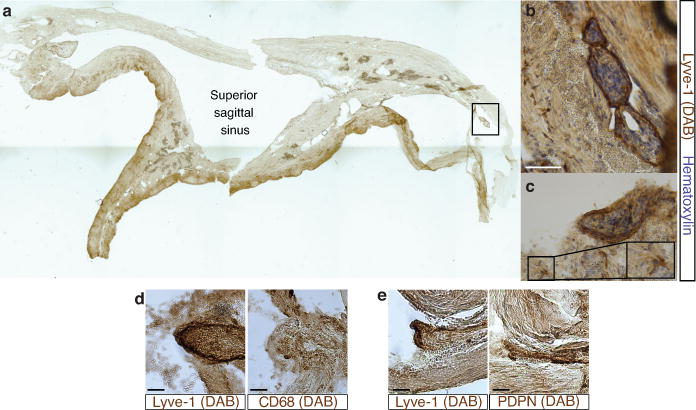

Extended Figure 4. Pilot identification of lymphatic vessels in human dura.

a. Representative image of a formalin-fixed coronal section of human superior sagittal sinus. b–c. Representative images of Lyve-1 staining on coronal section of human superior sagittal sinus (scale bar = 100 μm). The box in c highlights the presence of Lyve-1 expressing macrophages in human meninges, as seen in mice. d. Representative images of Lyve-1 and CD68 staining of coronal sections of human superior sagittal sinus. Note the absence of CD68 positivity on Lyve-1 positive structures (scale bar = 50 μm). e. Representative images of podoplanin and Lyve-1 staining of coronal sections of human superior sagittal sinus (scale bar = 50 μm).

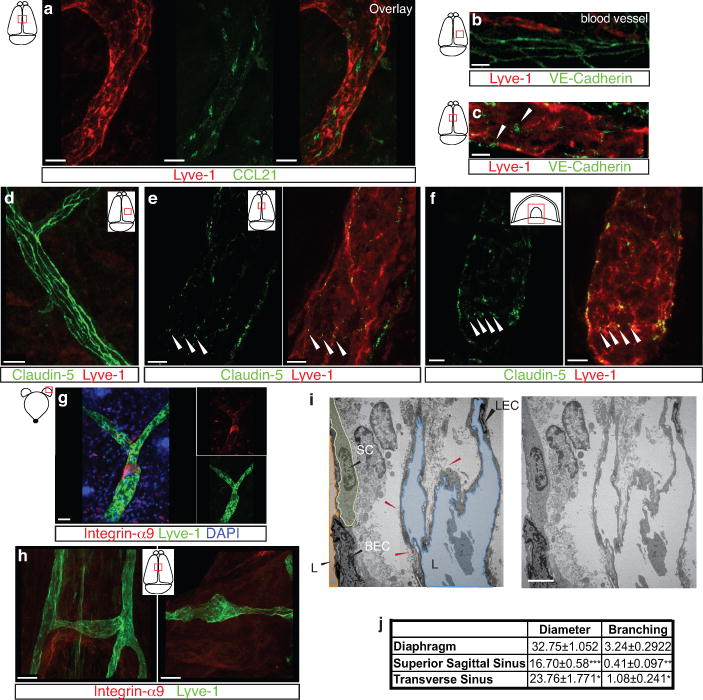

Extended Figure 5. Initial lymphatic features of meningeal lymphatic vessels.

a. Representative images of CCL21 and Lyve-1 labeling of the meningeal lymphatic vessels (scale bar = 10 μm). b–c . Representative images of VE-Cadherin and Lyve-1 staining on meningeal blood vessels (b) and meningeal lymphatic vessels (c), arrowheads point to the VE-Cadherin aggregates; scale bar = 10 μm). d–f. Representative images of Claudin-5 and Lyve-1 staining on meningeal blood (d) and lymphatic (e) vessels, and diaphragm lymphatic vessels (f); arrowheads point to Claudin-5 aggregates (scale bar = 10 μm). g–h. Representative images of integrin-α9 and Lyve-1 labeling on skin (g; ear) and meninges whole mount (h). Scale bar = 40 μm. No integrin-α9 expressing valves were detected in the meningeal lymphatic vessels. i. Representative low power micrographs (transmission EM) of the meningeal lymphatic vessels (scale bar = 2 μm); (L = lumen; SC = supporting cell; LEC = lymphatic endothelial cell; BEC = sinusal endothelial cell). Red arrowheads point to anchoring filaments. j. Table summarizing morphological features of the lymphatic network in different regions of the meninges and the diaphragm. Diameters are expressed in μm and branching as number of branches per mm of vessel; (mean ± SEM; n = 4 animals each group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; Two way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test). For statistics, the presented comparisons were between the diaphragm and the superior sagittal sinus and between the superior sagittal sinus and the transverse sinuses.

Extended Figure 6. Drainage of CSF into the meningeal lymphatic vessels.

a. Representative z-stack of QDot655 filled CSF drainage both in the blood vasculature (sinus) and in the meningeal lymphatic vessels after i.c.v. injection (scale bar = 20 μm). b. Representative images of CD31 and Lyve-1 immunostaining on whole mount meninges. Adult mice were injected i.c.v. with 2.5μg of Alexa 488 conjugated anti-Lyve-1 antibody. Thirty minutes after the injection, the meninges were harvested and stained with CD31. Injected in vivo, the Lyve-1 antibody illuminates the lymphatic vessels (scale bar = 20 μm). c. Representative z-stack of superior sagittal sinus of adult mice injected i.v. with QDot655 and i.c.v. with alexa488 conjugated anti-Lyve-1 antibody. ci. Coronal section of the z-stack presented in panel c. The signal from the remaining skull and/or collagen-rich structure above the meninges was recorded (blue). cii. 3D reconstruction of the z-stack presented in panel c showing the localization of the meningeal lymphatic vessels under the skull (scale bar = 50μm).

Extended Figure 7. Meningeal lymphatic vessels carrying immune cells.

a. Representative images of T cells (CD3e) and lymphatic endothelial cells (Lyve-1) on dural sinuses (scale bar=20μm). aii–aiii. Orthogonal sections representing T cell localization around (aii) and within (aiii) the Lyve-1 structures (scale bar=5μm). b. Quantification of the sinusal T cells and MHCII-expressing cells within the lymphatic vessels (mean ± SEM, n = 7–8 mice). c–d. Representative images of Lyve-1 staining on dural meninges from CD11cYFP mice (scale bar = 20μm). CD11c-positive cells (most probably dendritic cells) can be found inside the meningeal lymphatic vessels. e. Representative images of B220+ cells and lymphatic endothelial cells (Lyve-1) immunolabeling in the meninges (yellow arrowheads indicate B220+CD11c– cells; scale bar=20 μm). f. Representative dot plots of B220+ cells (gated on singlets, live, CD45+) within the dural sinuses expressing CD19; ~40% of the B220+ cells express CD19.

Extended Figure 8. Drainage of Evans blue from the meningeal lymphatics but not the nasal mucosa into the deep cervical lymph nodes.

a–c. Adult mice were injected i.c.v. with 5μl of 10% Evans blue. The meninges were harvested 30 min after injection and Evans blue localization was assessed by confocal microscopy. a. Representative images of Evans blue localization in both the sinus and the meningeal lymphatic vessels (n = 9 mice; scale bar = 40 μm). b. Representative profile of Evans blue and Lyve-1 relative fluorescence intensity on a cross-section of the image presented in panel a. c. Quantification of the average intensity of Evans blue in the sinus, the lymphatic vessels and the meninges of adult mice (mean ± SEM, n = 16 analyzed fields from 4 independent animals; **p<0.01, Kruskall-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). d–e. Adult mice were injected intranasally with 5μl of 10% Evans blue. The successful targeting of the nasal mucosa (d) and the lack of accumulation of Evans blue in the deep cervical lymph nodes (e) 30 min after the injection are demonstrated.

Extended Figure 9. Effects of deep cervical lymph node resection and of the lymphatic vessels ligation on the meningeal immune compartment.

a–e. The deep cervical lymph nodes were resected (xDCLN) or sham-operated. Three weeks after resection, the meninges were harvested, single cells isolated, and analyzed for T cell content by flow cytometry. a. Gating strategy to analyze meningeal T cells. Meningeal T cells are selected for singlets, CD45+, live cells and TCRβ+. b. Representative dot plot for CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in meninges of sham and xDCLN mice. c. Quantification of total T cells (TCRβ+), CD4+ and CD8+ in the meninges of xDCLN and sham mice (mean ± SEM; n = 3 animals each group; *p=0.018; **p=0.006 (CD8) p=0.003 (TCRb); Student’s T test; a representative experiment, out of two independently performed, is presented). d. Representative expression of CD62L and CD44 by CD4࿕ T cells phenotype in sham and xDCLN mice (n = 3 mice/group). e. Representative histogram for CD71 expression by meningeal CD4࿕ T cells in sham and xDCLN mice (n = 3 mice/group). f. Representative images of the ligation surgery. To highlight the lymph vessels, Evans blue was injected i.c.v. prior to the surgery. Black arrowhead points to the node, yellow arrowhead points to the ligated Evans blue filled vessels. g. Sham-operated or ligated animals were injected i.c.v. with 5μl of 10% Evans blue. The deep cervical lymph nodes were harvested 30 min after the injection and analyzed for Evans blue content. Representative images of the Evans blue accumulation in the deep cervical lymph nodes of the sham-operated and ligated animals are presented. h. Quantification of the meningeal lymphatic vessel diameter in the superior sagittal sinus and the transverse sinuses in sham mice and after ligation of the collecting lymphatic vessels (mean ± SEM, n = 5 mice/group; Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

Extended Figure 10. Connection between the glymphatic system and the meningeal lymphatic system.

A schematic representation of a connection between the glymphatic system, responsible for collecting of the interstitial fluids from within the CNS parenchyma to CSF, and our newly identified meningeal lymphatic vessels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shirley Smith for editing the manuscript. Dr. V. Engelhard (Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer biology, University of Virginia) for initial discussions and suggestions on lymphatic endothelial cell specific markers. We also thank the members of the Kipnis lab, Brain Immunology and Glia (BIG) center, and the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Virginia (especially Dr. John Lukens) for their valuable comments during multiple discussions of this work. Lawrence Holland and Dr. Beatriz Lopes (Department of Pathology, University of Virginia) provided the human samples. This work was funded by “Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale” to A.L. and by The National Institutes of Health (R01AG034113 and R01NS061973) to J.K.

Footnotes

All authors declare no financial interests or conflict of interests.

Author Contributions

A.L performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to experimental design and manuscript writing. I.S. performed all the surgeries and intracerebroventricular injections. T.K. assisted with the experiments and the analysis of the data. J.D.E, S.J.R. and J.D.P participated in the discussions and helped with the experimental design. N.C.D performed the xDCLN experiment. D.C. contributed to the imaging and the analysis of the electron microscopy images. J.W.M. contributed with data analysis of the human samples. K.S.L. contributed to experimental design and to manuscript editing. T.H.H. assisted to the intravital imaging experiment, contributed to experimental design and to manuscript editing. J.K. designed the study, assisted with data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ransohoff RM, Engelhardt B. The anatomical and cellular basis of immune surveillance in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:623–635. doi: 10.1038/nri3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kipnis J, Gadani S, Derecki NC. Pro-cognitive properties of T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:663–669. doi: 10.1038/nri3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shechter R, London A, Schwartz M. Orchestrated leukocyte recruitment to immune-privileged sites: absolute barriers versus educational gates. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:206–218. doi: 10.1038/nri3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldmann J, et al. T cells traffic from brain to cervical lymph nodes via the cribroid plate and the nasal mucosa. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:797–801. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaminski M, et al. Migration of monocytes after intracerebral injection at entorhinal cortex lesion site. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:31–39. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0511241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. The ins and outs of T-lymphocyte trafficking to the CNS: anatomical sites and molecular mechanisms. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alitalo K. The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat Med. 2011;17:1371–1380. doi: 10.1038/nm.2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Oliver G. Current views on the function of the lymphatic vasculature in health and disease. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2115–2126. doi: 10.1101/gad.1955910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baluk P, et al. Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2349–2362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerjaschki D. The lymphatic vasculature revisited. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:874–877. doi: 10.1172/JCI74854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debes GF, et al. Chemokine receptor CCR7 required for T lymphocyte exit from peripheral tissues. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:889–894. doi: 10.1038/ni1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber M, et al. Interstitial dendritic cell guidance by haptotactic chemokine gradients. Science. 2013;339:328–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1228456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazigou E, et al. Integrin-alpha9 is required for fibronectin matrix assembly during lymphatic valve morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2009;17:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koina ME, et al. Evidence for Lymphatics in the Developing and Adult Human Choroid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:1310–1327. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johanson CE, et al. Multiplicity of cerebrospinal fluid functions: New challenges in health and disease. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2008;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weller RO, Djuanda E, Yow H-Y, Carare RO. Lymphatic drainage of the brain and the pathophysiology of neurological disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2009;117:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu N-F, Lu Q, Jiang Z-H, Wang C-G, Zhou J-G. Anatomic and functional evaluation of the lymphatics and lymph nodes in diagnosis of lymphatic circulation disorders with contrast magnetic resonance lymphangiography. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:980–987. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girard J-P, Moussion C, Förster R. HEVs, lymphatics and homeostatic immune cell trafficking in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:762–773. doi: 10.1038/nri3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weller RO, Galea I, Carare RO, Minagar A. Pathophysiology of the lymphatic drainage of the central nervous system: Implications for pathogenesis and therapy of multiple sclerosis. Pathophysiol Off J Int Soc Pathophysiol ISP. 2010;17:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathieu E, Gupta N, Macdonald RL, Ai J, Yücel YH. In vivo imaging of lymphatic drainage of cerebrospinal fluid in mouse. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2013;10:35. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cserr HF, Harling-Berg CJ, Knopf PM. Drainage of brain extracellular fluid into blood and deep cervical lymph and its immunological significance. Brain Pathol Zurich Switz. 1992;2:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1992.tb00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris MG, et al. Immune privilege of the CNS is not the consequence of limited antigen sampling. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4422. doi: 10.1038/srep04422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laman JD, Weller RO. Drainage of cells and soluble antigen from the CNS to regional lymph nodes. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol Off J Soc NeuroImmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:840–856. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9470-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider M, Ny A, Ruiz de Almodovar C, Carmeliet P. A new mouse model to study acquired lymphedema. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kida S, Pantazis A, Weller RO. CSF drains directly from the subarachnoid space into nasal lymphatics in the rat. Anatomy, histology and immunological significance. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1993;19:480–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie L, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang L, et al. Evaluating glymphatic pathway function utilizing clinically relevant intrathecal infusion of CSF tracer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:107. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berton M, et al. Generalized lymphedema associated with neurologic signs (GLANS) syndrome: A new entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akiyama H, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hohlfeld R, Wekerle H. Immunological update on multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14:299–304. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.