Abstract

We describe the sexual behaviors of women at elevated risk of HIV acquisition who reside in areas of high HIV prevalence and poverty in the US. Participants in HPTN 064, a prospective HIV incidence study, provided information about participants’ sexual behaviors and male sexual partners in the past 6 months at baseline, 6- and 12-months. Independent predictors of consistent or increased temporal patterns for three high-risk sexual behaviors were assessed separately: exchange sex, unprotected anal intercourse [UAI] and concurrent partnerships. The baseline prevalence of each behavior was >30% among the 2,099 participants, 88% reported partner(s) with > one HIV risk characteristic and both individual and partner risk characteristics decreased over time. Less than high school education and food insecurity predicted consistent/increased engagement in exchange sex and UAI, and partner's concurrency predicted participant concurrency. Our results demonstrate how interpersonal and social factors may influence sustained high-risk behavior by individuals and suggest that further study of the economic issues related to HIV risk could inform future prevention interventions.

Keywords: sexual risk behaviors, longitudinal patterns, women in the US, exchange sex, unprotected anal intercourse, concurrent partnerships

Introduction

The HIV epidemic in the United States, now past the thirty year mark, remains entrenched. Women, who constitute approximately one-quarter of people living with HIV/AIDS, acquire HIV predominantly via heterosexual activity (1), and Black and Hispanic women bear a disproportionate share of the epidemic (1, 2). There is growing appreciation that HIV acquisition, especially among women, is determined by the geographic and demographic characteristics of sexual networks as well as by individual sexual behaviors (3).

The role of sexual networks in HIV acquisition among women depends on several factors, including the HIV risk characteristics and HIV prevalence of the male sexual partners in their network (3, 4). Partner characteristics such as prior incarceration, injection drug use and concurrent partnerships confer risk to the woman primarily because they are associated with HIV infection in the partner. HIV-infected partners who are unaware of their infection are not on treatment and therefore more likely to transmit, a situation more prevalent among black men and women than among whites (2, 5, 6). Incarceration rates are higher among black men than white men (7, 8), and HIV prevalence among the incarcerated is higher than in the general population (9). Moreover, not only do high incarceration rates among black men disrupt stable sexual partnerships, but they also contribute to the low male-to-female sex ratio observed in some communities (10). Low male-to-female sex ratios are associated with concurrent partnerships (11, 12), which, in turn, promote transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (10, 12, 13).

Sexual behaviors, specifically inconsistent condom use (14), anal intercourse (15-18), concurrent partnerships (16, 19) and exchange sex (20) have been associated with HIV transmission and/or prevalence. Cross-sectional studies have estimated the one-year prevalence of these risk behaviors among the general population of women, age 20-39 years, in the US at 21-23% for anal sex (21), 8% for concurrent partnerships (19) and 2% for exchange sex (19). Among urban, heterosexual women at elevated risk of HIV acquisition the reported one-year prevalence rates are higher, 38% for anal sex and 41% for exchange sex (22). The few studies that have assessed longitudinal patterns of sexual risk behaviors, particularly among women at elevated risk, have focused on adolescents (23) or have a small sample size (24). Thus, there is little information about how these specific sexual risk behaviors may change over time and what initial factors predict sustained patterns of engaging in a given risk behavior. Identifying such factors may help inform HIV prevention interventions for women.

The HPTN 064 study was conducted in 2009-2010 to assess HIV incidence and to describe behaviors among US women at elevated risk for HIV infection who resided in areas of poverty and high HIV prevalence (25). In this report, we describe the reported sexual risk behaviors of HPTN 064 participants and the reported characteristics of their male sexual partners. We examine the longitudinal patterns and predictors of exchange sex, unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) and concurrent partnerships and assesse baseline factors predictive of sustained or increased, engagement in these three behaviors over time in order to characterize those women who may be in most need of prevention interventions. The analysis is informed by the Socioecologic Framework (SEF) (26) which acknowledges that health behaviors and related outcomes are influenced by multiple facets of the physical and social environment (27, 28). We explore two levels of the SEF: the individual (i.e., the participant's behaviors), and the interpersonal (i.e., characteristics of male sex partners) and their associations with temporal patterns of sexual risk behaviors.

Methods

Study Design

HPTN 064 was a multisite, longitudinal observational HIV seroincidence study. Details about the study design, including participant screening, enrollment, follow-up, as well as laboratory methods have been previously reported (25, 29).

In brief, in order to be eligible, individuals had to self-identify as women, age 18-44 years, who resided in census tracts or zip codes that ranked in the top 30th percentile of HIV prevalence and had >25% of inhabitants living in poverty within six geographic locations of the US (Atlanta, GA; Baltimore, MD; New York City, NY; Newark, NJ; Raleigh-Durham, NC; Washington, DC) (30). They also had to report at least one episode of unprotected vaginal and/or anal sex with a man in the six months before enrollment; agree to undergo HIV rapid testing; and had to report at least one of the following in the prior six months: individual risk behaviors (exchange sex [defined below], sexually transmitted infection (STI) history, drug use, binge drinking [four or more drinks in one sitting], alcohol dependence, incarceration in the past five years) or a partner with at least one high-risk characteristic (drug use, incarceration history in past five years, STI history, HIV-positive diagnosis, binge drinking or alcohol dependence). Exclusion criteria included self-reported history of previous positive results on an HIV test. Using venue-based sampling, eligible women were enrolled between May 2009 and July 2010 from 10 communities in the six geographic areas. The study was approved by institutional review boards at each site and collaborating institutions, and a certificate of confidentiality was obtained.

Data Collection and Quantitative Measures

Participants received routine HIV testing and counseling, with access to free condoms, and completed an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) at baseline and at 6-month intervals, with six or twelve months of follow-up, depending on when they enrolled in the study (25). ACASI was used to collect data on individual- and interpersonal-level characteristics, including age, level of education, annual income, employment status, and incarceration history, as well as information about alcohol and substance use, mental health symptoms (depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], defined per Radloff (31) and Prins (32), respectively) and social support. Information on sexual behaviors in the prior six months and about the characteristics of the three most recent male partners during the prior six months was also solicited via ACASI from all participants and is the source of the data on individual behaviors and partner characteristics reported in this paper.

Participants were asked about total number of male sexual partners in the previous six months and of these, how many partners were a result of needing to exchange commodities for sex; and for each of the three most recent male sexual partners in the prior six months, information was collected on the dates of first and last sex, condom use and the HIV risk characteristics of that partner. The ACASI asked the participant to report whether each of her last three partners had a concurrent relationship in the past six months, i.e., sex with others while the partner was in a sexual relationship with the participant [response choices: definitely did, probably did, probably did not, or definitely did not]. The ACASI also asked the participant “ Do you consider yourself to be ‘a commercial sex worker (prostitute)?’ ” [response choices: Yes, No, Don't know]. A high-risk sex partner was defined as a partner who had one or more of the following HIV risk characteristics, as reported by the participant: unknown or HIV-seropositive status; concurrency (referred to as partner's concurrency below); any history of injection drug use; or a history of incarceration (jail and/or prison > 24 hours).

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes for this analysis were (i) among all participants at each study visit, the prevalence of exchange sex, UAI and participant concurrency; (ii) among all participants at each study visit, the prevalence of four partner high-risk characteristics as reported by participants (unknown or positive HIV serostatus, history of incarceration, history of injection drug use, or having other sexual partners (“partner concurrency”); and (iii) among participants with complete data at all three visits, the temporal patterns for each of the three individual sexual behaviors and the predictors of high-risk temporal patterns. These specific sexual risk behaviors and partner characteristics were selected for analysis because existing literature links each behavior to HIV transmission and/or prevalence, as described above.

In this analysis, exchange sex was defined as sex with at least one sexual partner in the previous six months in exchange for money or for commodities such as food, shelter or drugs, each posed as a separate question. UAI was based on reporting any anal sex without the use of a condom during the last six months. Participant concurrency was determined by comparing the dates (recorded as month and year) of first and last sexual intercourse for the most recent partners described in the ACASI (up to a maximum of three in the prior six months). A participant's partnership was defined as concurrent if the month of first sexual intercourse with one partner occurred before the month of last intercourse with another partner. Participants with non-concurrent partnerships had to have complete data on the timing of all reported partnerships and the dates could not overlap; those with incomplete data were excluded from the concurrency analyses. Partner concurrency was defined by the participant reporting that any of her last three partners “definitely did” have sex with another person during the course of her sexual relationship with him.

We defined a priori temporal patterns based on existing literature, as described above, for each of the three individual sexual behaviors of interest (Table II) in order to distinguish among consistent, increased, decreased and inconsistent patterns for each behavior. Specifically, participant's behavior based on measurements at baseline, 6- and 12-month visits, were summarized into a single “pattern” per participant for exchange sex, anal sex and participant concurrency, with each behavior analyzed separately. Summarizing repeated measurements into a single summary statistic for each individual is a common approach to the analysis of longitudinal data (33). Consistent or increased reporting of a behavior over the course of the study defined a high-risk temporal pattern while a consistent lack or decreased reporting of a behavior over the course of the study defined a low-risk temporal pattern. Those who reported a behavior at baseline and the 12-month visit but not at the 6-month visit, or vice versa, were categorized as having an inconsistent temporal pattern.

Baseline predictors of having a high-risk temporal pattern as compared to a low-risk pattern were assessed separately for each behavior. Predictors fell into one of two levels of the SEF (individual or intrapersonal). The selection of these levels was based on the substantial literature highlighting the importance of individual and interpersonal risk factors in HIV transmission and acquisition (14-18) (16, 19, 20). Patterns were analyzed among participants with complete data about each behavior in the prior six months at all three study visits, i.e., during a period spanning 18 months. Participants with inconsistent temporal patterns were excluded from this portion of the analysis.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS (Version 9.2, Cary, NC). Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to examine the presence of significant trends in sexual risk behavior over the course of the study period. Bivariate analyses using independent t-tests and chi-square analyses as appropriate were conducted. Baseline demographic, mental health, substance use, individual sexual risk, and partner risk characteristics associated with high-risk temporal patterns were assessed separately for exchange sex, anal sex and participant concurrency. Factors associated (p < 0.10) in bivariate analyses with having a high-risk temporal pattern for exchange sex, anal sex or participant concurrency were included in corresponding multivariate logistic regression models. Exchange sex, anal sex and participant concurrency were each assessed separately. Lastly, sensitivity analyses using bivariate t-tests and chi-square analyses were conducted to compare baseline characteristics between individuals who completed their scheduled follow-up versus those who were lost to follow-up. As previously described in Adimora et al. (34), analysis of concurrency data is limited by missing dates, however, for all other variables, missing data comprise approximately 1% of most responses (25). Our analyses assume that missing data are missing at random.

Results

Baseline characteristics, sexual behaviors and partner risk characteristics

Among the total 2,099 participants who enrolled in HPTN 064, the median age was 29 years, 86% were black, 44% had an annual household income of less than $10,000 and 46% reported being concerned about having sufficient food for themselves and/or their families over the past 6 months (Table I). Illicit drug use and binge drinking, each at least weekly, PTSD and depressive symptoms were each reported at enrollment by approximately one-fourth of participants. Most participants (82%) reported unprotected sex at the last episode of vaginal intercourse. In the six months prior to enrollment, the median number of sexual partners was 2 (IQR 1-3) and more than one-third of participants (38%) reported at least one episode of anal sex; of these, 80% reported UAI at the last episode of anal sex. While 6% of all participants considered themselves to be commercial sex workers, 37% reported exchanging sex for food, shelter, drugs or money. Almost half (40%) reported concurrent partnerships (Table I).

Table I.

Prevalence of baseline characteristics among women in HPTN 064 (n = 2099)

| Characteristics | N | %a or IQR |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, years | 29 | IQR: 23-38 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 245 | 12 |

| African-American race | 1802 | 86 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 777 | 37 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 772 | 37 |

| More than high school graduate | 550 | 26 |

| Unemployed | 1357 | 65 |

| Household Income | ||

| $10,000 or less | 933 | 44 |

| $10,001 to $20,000 | 225 | 11 |

| $20,001 or More | 197 | 9 |

| refused/don't know/no answer | 744 | 35 |

| Incarceration in last 5 years* | 848 | 40 |

| Binge drinking at least weekly in past 6 months* b | 498 | 24 |

| Substance abuse at least weekly in the past 6 months* | 459 | 22 |

| Depressive symptoms c | 692 | 36 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder d | 600 | 29 |

| Food insecurity for themselves and/or their families in past 6 months. | 971 | 46 |

| Individual Sexual Risk Behaviors | ||

| Median number # of partners in past 6 months [IQR] | 2 | IQR: 1-3 |

| Unprotected sex at last episode of vaginal sex | 1698 | 82% |

| Any anal sex in past 6 months | 796 | 38% |

| UAI at last episode of anal sex | 637 | 31% |

| Any UAI in last 6 months | 730 | 35% |

| Concurrent partnerships (CP) in past 6 monthse | 656 | 40% |

| Commercial sex worker | 117 | 6% |

| Exchange of sex for money or commodities in past 6 mo.* | 776 | 37% |

| Sexual abuse in past 6 months | 148 | 7% |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 1631 | 79% |

| Homosexual | 35 | 2% |

| Bisexual | 348 | 17% |

| Other/Not Sure/Missing | 85 | 4% |

| Self-reported STI (gonorrhea, syphilis, or chlamydia) in past 6 mo. * | 232 | 11% |

| Partner Sexual Risk Characteristics f | ||

| HIV status of last vaginal sex partner | ||

| HIV-negative | 1199 | 57% |

| HIV-positive* | 27 | 1% |

| HIV status unknown | 865 | 41% |

| Partners' concurrency in past 6 months | 763 | 36% |

| Injection drug use in past 6 months | 175 | 8% |

| Any incarceration * | 1434 | 68% |

| Reporting male partner(s) with at least one risk characteristic g | 1853 | 88% |

Values are presented as numbers (percentages) unless otherwise indicated.

part of eligibility criteria

percentages are based on number of participants with non-missing data; missing data comprise approximately 1% of most responses, as described in Hodder et al.; 18

binge drinking: defined as ≥4 alcoholic beverages on one occasion;

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression Scale (CES-D) was administered, with a score of ≥7 (on 8-item scale) indicating psychological distress or depressive symptoms; 21

The Primary Care PTSD screen was administered, with a score >3 denoting PTSD;22

at baseline, 1628 participants had complete data on the timing of all reported partnerships;

partner characteristics are as reported by the participants;

risk characteristics: unknown or positive HIV serostatus, partners’ concurrency, infection drug use in past 6 months and/or any incarceration.

Most participants reported having male sexual partners in the prior six months with one or more HIV risk characteristics (Table I). While only 27 (1%) participants reported that their last vaginal or anal sex partner was HIV-infected, 41% did not know the HIV status of their last vaginal sex partner, and 58% did not know the HIV status of at least one of their last three partners. Most participants (68%) reported having partners who had ever been incarcerated, 36% reported partners’ concurrency, but only 8% reported that their partner had a history of IDU. Taken together, the vast majority (88%) reported having at least one recent male sex partner(s) with at least one of the HIV risk characteristics listed above.

Longitudinal patterns of sexual behavior

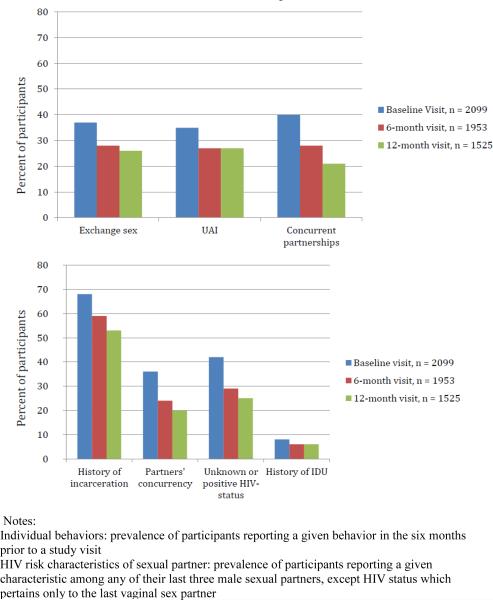

Of the 2,099 participants enrolled at baseline, 1,953 and 1,525 completed the 6- and 12- month visits, respectively, reflecting the design of the study and retention rates at 6-months and 12-months of 93% and 94%, respectively; a total of 158 participants did not complete study follow-up visits as scheduled. As depicted in Figure 1, there were statistically significant decreases in the overall prevalence of the three high-risk individual sexual behaviors among all participants, namely, UAI (35% at baseline to 27% by the 12-month visit), exchange sex (37% to 26%) and participant concurrency (40% to 21%) [p < 0.0001 for each high-risk behavior,]. Similarly, significant decreases in partner risk characteristics were observed between the baseline and 12-month visits for partner incarceration and for unknown or positive HIV status of partners (68% to 53%, and 42% to 25%, respectively; p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

a. Prevalence of individual sexual risk behaviors over time

b. Prevalence of HIV risk characteristics of sexual partners over time

To assess whether the decreases in prevalence were related to retaining women who reported fewer risk behaviors and fewer partners with risk characteristics compared to those who were not retained in the study, we examined the prevalence of the three selected risk behaviors at baseline among the 158 women who did not complete follow-up visits as scheduled versus the 1941 who did. We found no difference in the prevalence of exchange sex or UAI but we did find a smaller proportion of those who were not retained reported concurrent partners compared to those who completed all visits as scheduled (31% vs 41%, p =0.035). We also examined the prevalence of each of the three high-risk behaviors among the 1,498 participants who completed both the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits and found the prevalence and the trends over time were no different from the overall group (data not shown).

We assessed the prevalence of different longitudinal patterns for each sexual risk behavior among those participants with complete data at baseline, 6- and 12-month visits [exchange sex (n = 1,450); UAI (n = 1,498); and participant concurrency (n = 845)], and the results are displayed in Table II. The prevalence of high-risk, low-risk and inconsistent temporal patterns were similar for each behavior. High-risk temporal patterns occurred in about one-fifth of participants (exchange sex: 23%, UAI: 21%, and participant concurrency: 17%). Low-risk patterns were common: a consistently low-risk pattern occurred in about half of participants (50%, 48% and 46% for each respective behavior) and a decreased risk pattern was reported by another one-fifth of the group (20%, 20% and 27%, respectively), i.e., no reports of the given behavior at either the last one or two visits. A minority of participants reported inconsistent temporal patterns (8%, 12% and 10%, respectively).

The variables independently associated with a high-risk temporal pattern, compared to a low-risk pattern, differed for each sexual behavior (Table III). There were several predictors of a high-risk temporal pattern for exchange sex and these included (adjusted odds ratios (aOR) listed from largest to smallest magnitude): less than high school education (aOR 2.22; 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.48, 3.32]), food insecurity (aOR 1.77; 95% CI [1.30, 2.39]), having a partner with unknown HIV status (aOR 1.52; 95% CI [1.12, 2.06]), depressive symptoms (aOR 1.51; 95% CI [1.09, 2.09]), prior incarceration of the participant (aOR 1.48; 95% CI [1.09, 2.00]), binge drinking (aOR 1.38; 95% CI [1.001, 1.91] and older age (aOR 1.23 for every 5 year increase; 95% CI [1.11, 1.36]). Predictors of a high-risk temporal pattern for UAI were Hispanic ethnicity, less than high school education and food insecurity (aOR 2.14; 95% CI [1.35, 3.39]; 1.63 [1.15, 2.33] and 1.41 [1.07, 1.85], respectively). Partner's concurrency was the only predictor of a high-risk temporal pattern for participant concurrency (1.78; 95% CI [1.21, 2.64]).

Table III.

Multivariable Analysis: Individual and partner characteristics associated with high-risk temporal patterns compared to low-risk temporal patterns for individual sexual behaviors [adjusted odds ratio and 95% CI]

| Individual Behaviors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange Sex | UAI | Participant's Concurrency | |

| Individual Characteristics* | n = 1333 | n = 1325 | n = 761 |

| Median age, increase in age by 5 years | 1.23 [1.11, 1.36] | 1.06 [0.97, 1.15] | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 2.14 [1.35, 3.39] | 1.71 [0.96, 3.05] | |

| African-American Race | 1.00 [0.64, 1.56] | ||

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 2.22 [1.48, 3.32] | 1.63 [1.15, 2.33] | |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 1.18 [0.79, 1.77] | 1.35 [0.95, 1.93] | |

| More than high school graduate (ref) | |||

| Unemployed | 1.24 [0.88, 1.73] | ||

| Income | |||

| $10,000 or less | 1.86 [0.998, 3.46] | ||

| $10,001 to $20,000 | 1.46 [0.71, 3.02] | ||

| $20,001 or More | |||

| Refused/don't know/no answer | 1.61 [0.85, 3.08] | ||

| Prior incarceration | 1.48 [1.09, 2.00] | ||

| Binge drinking in the past 6 months | 1.38 [1.001, 1.91] | 1.22 [0.90, 1.65] | 1.39 [0.90, 2.15] |

| Substance abuse in the past 6 months | 1.37 [0.95, 1.98] | 1.13 [0.81, 1.59] | 1.28 [0.81, 2.02] |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.51 [1.09, 2.09] | 1.34 [0.90, 2.01] | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1.10 [0.79, 1.55] | 1.12 [0.83, 1.50] | |

| Number of partners in past 6 months (+1) | 1.02 [0.999, 1.03] | ||

| Sexual abuse in past 6 months | 1.34 [0.80, 2.22] | ||

| Concern about having sufficient food | 1.77 [1.30, 2.39] | 1.41 [1.07, 1.85] | |

| Partner Characteristics | |||

| HIV Status of last vaginal sex partner | |||

| HIV-negative (ref) | |||

| HIV-positive | 1.12 [0.34, 3.69] | ||

| HIV status unknown | 1.52 [1.12, 2.06] | ||

| Partners' concurrency in past 6 months | 1.78 [1.21, 2.64] | ||

| Injection drug use in past 6 months | 0.94 [0.58, 1.52] | ||

| Any Incarceration | 1.49 [0.88, 2.51] | ||

| Prevalence of reporting male partner(s) with at least one risk characteristic | 1.31 [0.77, 2.23] | 1.30 [0.53, 3.18] | |

Variables with univariate p<0.1 were included in the multivariate model.

Adjusted odds ratios in bold face font indicate statistical significance, with 95% CI excluding 1.000

Discussion

This study presents one of the few longitudinal analyses of sexual behaviors among women in the US at elevated risk of HIV infection (24, 35, 36). We found that high-risk individual behaviors of exchange sex, unprotected anal intercourse and concurrent partnerships were common, each reported by approximately one-third of participants. High-risk interpersonal factors, namely sexual partners with high-risk characteristics, such as unknown HIV status and prior incarceration, were even more common, reported by as many as half of participants. The prevalence of individual high-risk behaviors decreased over time and the predictors of reporting sustained or increased engagement in these behaviors varied. This description of individual sexual risk behaviors and partner risk characteristics provides a detailed context for the HIV incidence results previously reported from this cohort of women (25).

As exchange of sex for commodities and having a partner with a history of incarceration or injection drug use were part of the enrollment criteria, the high prevalence of these risk factors is not unexpected and indicates the study succeeded in reaching its target population. However, other sexual behaviors and partner characteristics not directly part of the enrollment criteria were also prevalent, namely participant's concurrency, partner's concurrency or a partner with unknown HIV serostatus. These findings suggest that these factors may be linked together and may contribute to a complex and risky sexual network (3, 37).

Despite the lack of any intervention in the HPTN 064 study beyond routine HIV risk-reduction counseling at 6-month intervals, the prevalence of all three individual, self-reported high-risk behaviors and all four male partner characteristics decreased significantly over 18 months. This is similar to our findings on unprotected vaginal sex at last vaginal sex in this cohort where condom use at last vaginal sex increased from 18% at baseline to 35% at 6 months and 37% at 12 months (25). The observed decreases may have been due to regression to the mean, behavioral changes due to the counseling provided in the study or due to a Hawthorne effect, or a combination of all of these. Decreases in risk behavior among participants in HIV prevention studies have been noted previously, including among participants in the control arms of interventional studies (35, 38, 39). If the decreased prevalence of high-risk behaviors reported in this observational study are attributable to study participation (counseling or Hawthorne effect) then the annual HIV incidence observed in HPTN 064 (0.32%)(25) would underestimate the actual incidence in this population.

Longitudinal analyses of sexual behaviors among women in the US have seldom been reported, as noted above. We analyzed the predictors of sustained or increased engagement in high-risk behaviors over the course of the study in order to characterize those who may need prevention interventions beyond routine counseling and access to free condoms. High-risk temporal patterns occurred in less than one-quarter of participants and predictors of high-risk patterns varied for each of the three analyzed behaviors. Our results, when placed within the context of SEF, demonstrate how interpersonal and social factors may influence sustained high-risk behavior by individuals. The only common predictors were education and food insecurity: those with less than high school education and with food insecurity were more likely to report high-risk temporal patterns for both exchange sex and UAI. Our findings suggest food insecurity and less than high school education may be part of a complex set of economic issues related to HIV risk among women. The only baseline predictor for participant concurrency, however, was partner's concurrency. While little has been published about predictors of exchange sex and UAI over time among women, the finding on concurrent partnerships is consistent with prior studies (19, 25, 40, 41). Our study adds to these findings by demonstrating that it is a significant baseline predictor of consistently engaging in concurrent partnerships overtime. By placing an individual behavior such as participant concurrency within the context of interpersonal relationships, we were able to explain some of the individual variation in the behavior. Furthermore, existing literature speaks to the influence of perceived social/cultural norms related to concurrent partnerships that could also be driving this relationship (40-42).

More than one-third of participants reported at least one episode of anal sex in the prior 6 months, and among these participants, the majority reported UAI at the last episode. As noted above, the one-year prevalence of anal sex among the general population of women in the US is about 20% (21), and the prevalence of recent anal intercourse (past three months) has been estimated at 22% among women receiving services at an STI clinic (43). As noted above, complex economic pressures may promote engagement in unprotected anal sex among women in this cohort. In addition, our findings regarding Hispanic ethnicity as a baseline predictor of sustained engagement in UAI may also speak to cultural norms related to anal-sex among heterosexual couples, a topic with scant literature . The prevalence of UAI observed in this cohort underscores the need for HIV prevention approaches that will reduce the risk of HIV acquisition via anal intercourse for both women and for men. Future research exploring the multilevel predictors of sustained UAI could inform these prevention efforts.

The study had several strengths. The study successfully used venue-based recruitment to systematically sample young women representative of women in the US at elevated risk for HIV acquisition. We believe our findings apply to women in the US with high-risk characteristics and may inform future research studies aimed at decreasing sexual risk behaviors among this group. The study prospectively assessed sexual behaviors and the reported characteristics of male partners of women at elevated risk for HIV infection, allowing for a longitudinal analysis of behaviors among each participant, rather than a series of cross-sectional analyses. We established a priori temporal categories of risk behavior that allowed us to identify and analyze sustained and increased patterns as compared to decreased patterns.

The small number of incident HIV infections in HPTN 064 hindered our ability to identify specific sexual risk factors associated with new HIV infections. The HPTN 064 study found an overall annual HIV incidence of 0.32%, based on four participants who, at enrollment, had evidence of either recent or acute HIV and an additional four who seroconverted during follow-up; there were 32 (1.5%) prevalent infections newly diagnosed at enrollment. As previously described, reporting anal sex in past six months at baseline was not associated with incident HIV infection nor with prevalent HIV infection and the only partner risk factor associated with prevalent HIV infection in participants was known HIV infection of the partner (25).

Our longitudinal analysis was limited to those participants with complete data available at all three visits. Data were less complete for concurrent partnerships due to missing first and/or last dates of sexual intercourse for some partners. The limitations of assessing both concurrency and partners’ concurrency as perceived concurrency have been previously reported (34). Participants at highest risk of HIV acquisition may not have enrolled because of the study requirement to be available for a 6- and/or 12-month follow-up visit, therefore there may have been a bias toward including somewhat lower risk women. On the other hand, the baseline prevalence rates of sexual risk behaviors were substantial. It is noteworthy that sensitivity analyses indicated that the observed decreases in prevalence were not related to retaining women who reported fewer risk behaviors compared to those who were not retained in the study. In addition, the analyses examined individual and interpersonal predictors of risk patterns over time. It is possible that other multilevel factors, as informed by the SEF, such as neighborhood-level attributes, may also play an important role in women's HIV risk over time (44).

All studies based on self-reported sensitive behavioral data, including this one, are limited by recall bias and social desirability bias. The use of ACASI, however, rather than face-to-face interviews, may improve the reliability of the HPTN 064 data on sexual behavior and other sensitive topics (45).

In conclusion, the prevalence of high-risk sexual behaviors and high-risk male partners among women in HPTN 064 was substantial, reflecting the risky nature of their sexual networks as well as the enrollment criteria. These prevalence rates, however, all decreased over time without any specific intervention beyond participation in a study that included routine HIV counseling and testing and administration of a survey at 6-month intervals and monthly phone calls. Our findings suggest that among women at elevated risk of HIV acquisition, those who report food insecurity and lower educational attainment may require HIV prevention interventions that go beyond routine counseling, and further studies are needed to develop and implement effective economic and biomedical interventions.

Table IIa.

Illustration of categories used to classify temporal patterns for each risk behavior

| Study visit | Risk pattern | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did participant report specific risk behavior in the last six months? | Baseline | 6-month visit | 12-month visit | |

| High-risk pattern | ||||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Consistently high risk | |

| No | Yes | Yes | Increased risk | |

| No | No | Yes | Increased risk | |

| Low-risk pattern | ||||

| No | No | No | Consistently low risk | |

| Yes | No | No | Decreased risk | |

| Yes | Yes | No | Decreased risk | |

| Inconsistent pattern | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | Inconsistently low risk | |

| No | Yes | No | Inconsistently high risk | |

Table IIb.

Prevalence of temporal patterns for sexual risk behaviors at baseline, 6- and 12-month visits*

| Temporal Patterns | Sexual risk behavior | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange Sex | UAI | Participant's Concurrency | ||||

| N=1450 | % | N=1498 | % | N=845 | % | |

| High-risk patterns | ||||||

| Consistently high risk (YYY**) | 231 | 16 | 159 | 11 | 88 | 10 |

| Increased risk over 2 visits (NYY) | 43 | 3 | 58 | 4 | 25 | 3 |

| Increased risk at last visit (NNY) | 53 | 4 | 94 | 6 | 34 | 4 |

| Sub-total | 327 | 23 | 311 | 21 | 147 | 17 |

| Low-risk patterns | ||||||

| Consistently low risk (NNN) | 719 | 50 | 713 | 48 | 385 | 46 |

| Decreased risk over 2 visits YNN) | 178 | 12 | 190 | 13 | 139 | 16 |

| Decreased risk at last visit YYN | 109 | 8 | 111 | 7 | 90 | 11 |

| Sub-total | 1006 | 69 | 1014 | 68 | 614 | 73 |

| Inconsistent patterns | ||||||

| Inconsistently high risk YNY | 44 | 3 | 85 | 6 | 32 | 4 |

| Inconsistently low risk NYN | 73 | 5 | 88 | 6 | 52 | 6 |

| Sub-total | 117 | 8 | 173 | 12 | 84 | 10 |

among participants with complete data for the specific behavior

Y: participant answered “Yes” to question about whether she had engaged in the specific behavior in the prior 6 months. N = participant answered “No” to question about whether she had engaged in the specific behavior in the prior 6 months. For example, NNN means participant answered “No” to each question at baseline, 6-month and 12-month visits.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants, community stakeholders, and staff from each study site. In addition, they acknowledge Lynda Emel, Jonathan Lucas, Nirupama Sista, Kathy Hinson, Elizabeth DiNenno, Ann O'Leary, Lisa Diane White, Waheedah Shabaaz-El, Quarraisha Abdool-Karim, and Sten Vermund., LeTanya Johnson-Lewis, Edward E. Telzak, Rita Sondengam, Cheryl Guity, Stephanie Lykes, Khadijah Abass, Eileen Rios, Manya Magnus, Christopher Chauncey Watson, Ilene Wiggins, Adongo Tia-Okwee, Joseph Eron, Cheryl Marcus, Valarie Hunter, and Christin Root.

Grant Support: By the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Institute of Mental Health (cooperative agreement no. UM1 AI068619, U01-AI068613, and UM1-AI068613); Centers for Innovative Research to Control AIDS, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University (5UM1Al069466); University of North Carolina Clinical Trials Unit (AI069423); University of North Carolina Clinical Trials Research Center of the Clinical and Translational Science Award (RR 025747); University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (AI050410); Emory University HIV/AIDS Clinical Trials Unit (5UO1AI069418), Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409), and Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR025008); Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS Clinical Trials Unit; Johns Hopkins Adult AIDS Clinical Trial Unit (AI069465), Johns Hopkins Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 25005); Robert W. Woodruff pre-doctoral fellowship of the Emory University Laney Graduate School; the National Institute of Mental Health (F31MH105238); and Columbia University Irving Institute Clinical and Translational Science Award TL1 TR000082-07.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, the HPTN, or its funders.

References

- 1.Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV surveillance supplemental report: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen M, Rhodes PH, Hall HI, Kilmarx PH, Branson BM, Valleroy LA. Prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection among persons aged≥ 13 years—National HIV Surveillance System, United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(02):57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodder SL, Justman J, Haley DF, Adimora AA, Fogel CI, Golin CE, et al. Challenges of a hidden epidemic: HIV prevention among women in the United States. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 1999;2010;55(Suppl 2):S69. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbbdf9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tillerson K. Explaining racial disparities in HIV/AIDS incidence among women in the U.S.: a systematic review. Statistics in medicine. 2008;27(20):4132–43. doi: 10.1002/sim.3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HIV prevalence estimates--United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(39):1073–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence --- 24 cities, United States, 2006-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(31):1045–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, Wang L, Liu TY, Mayer KH. The high prevalence of incarceration history among black men who have sex with men in the United States: associations and implications. American journal of public health. 2014;104(3):448–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson E, Sabol W. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, DC: 2012. Prisoners in 2011. NCJ 239808. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruschak LM. HIV in Prisons, 2001-2010. AIDS. 2012;20:25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Blankenship KM. Public health reports. Suppl 4. Vol. 125. Washington, DC: 2010. Associations of sex ratios and male incarceration rates with multiple opposite-sex partners: potential social determinants of HIV/STI transmission. pp. 70–80. 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Khan MR, Schwartz RJ, Miller WC. Sex ratio, poverty, and concurrent partnerships among men and women in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Annals of epidemiology. 2013;23(11):716–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Adimora AA. Sexual mixing patterns and heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans in the southeastern United States. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2009;52(1):114. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab5e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Liddon N, Fenton KA, Aral SO. Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal and oral sex in adolescents and adults in the United States. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007;196(12):1852–9. doi: 10.1086/522867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vincenzi I. A longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by heterosexual partners. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. The New England journal of medicine. 1994;331(6):341–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicolosi A, Correa Leite ML, Musicco M, Arici C, Gavazzeni G, Lazzarin A. The efficiency of male-to-female and female-to-male sexual transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus: a study of 730 stable couples. Italian Study Group on HIV Heterosexual Transmission. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 1994;5(6):570–5. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Risser JM, Padgett P, Wolverton M, Risser WL. Relationship between heterosexual anal sex, injection drug use and HIV infection among black men and women. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2009;20(5):310–4. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. International journal of epidemiology. 2010;39(4):1048–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novak RM, Metch B, Buchbinder S, Cabello R, Donastorg Y, Figoroa JP, et al. Risk behavior among women enrolled in a randomized controlled efficacy trial of an adenoviral vector vaccine to prevent HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2013;27(11):1763–70. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328360c83e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Khan MR, Schwartz RJ. Concurrent partnerships, nonmonogamous partners, and substance use among women in the United States. American journal of public health. 2011;101(1):128–36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Social science & medicine (1982) 2004;59(8):1581–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14-94. The journal of sexual medicine. 2010;7(Suppl 5):255–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenness SM, Begier EM, Neaigus A, Murrill CS, Wendel T, Hagan H. Unprotected anal intercourse and sexually transmitted diseases in high-risk heterosexual women. American journal of public health. 2011;101(4):745–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sales JM, Brown JL, Diclemente RJ, Rose E. Exploring Factors Associated with Nonchange in Condom Use Behavior following Participation in an STI/HIV Prevention Intervention for African-American Adolescent Females. AIDS research and treatment. 2012;2012:231417. doi: 10.1155/2012/231417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Knetch J, Hill J. Patterns of sexual risk behavior change among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients. Archives of sexual behavior. 2005;34(3):307–19. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-3119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodder SL, Justman J, Hughes JP, Wang J, Haley DF, Adimora AA, et al. HIV acquisition among women from selected areas of the United States: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2013;158(1):10–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior. 1988;15(4):351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA, Rosenthal SL. Prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: the importance of a socio-ecological perspective--a commentary. Public Health. 2005;119(9):825–36. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: a social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):210–24. doi: 10.1037/a0032704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eshleman SH, Hughes JP, Laeyendecker O, Wang J, Brookmeyer R, Johnson-Lewis L, et al. Use of a multifaceted approach to analyze HIV incidence in a cohort study of women in the United States: HIV Prevention Trials Network 064 Study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;207(2):223–31. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallagher KM, Sullivan PS, Lansky A, Onorato IM. Behavioral surveillance among people at risk for HIV infection in the U.S.: the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974) 2007;122(Suppl 1):32–8. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2004;9(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger S. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adimora AA, Hughes JP, Wang J, Haley DF, Golin CE, Magnus M, et al. Characteristics of multiple and concurrent partnerships among women at high risk for HIV infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2013 Sep 13; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a9c22a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartholow BN, Buchbinder S, Celum C, Goli V, Koblin B, Para M, et al. HIV sexual risk behavior over 36 months of follow-up in the world's first HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(1):90–101. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000143600.41363.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, Schackman BR, Matheson T, Das M, et al. Effect of risk-reduction counseling with rapid HIV testing on risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections: the AWARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(16):1701–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aral SO, Adimora AA, Fenton KA. Understanding and responding to disparities in HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in African Americans. The Lancet. 2008;372(9635):337–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guest G, Shattuck D, Johnson L, Akumatey B, Clarke EE, Chen PL, et al. Changes in sexual risk behavior among participants in a PrEP HIV prevention trial. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(12):1002–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaul R, Kimani J, Nagelkerke NJ, Fonck K, Keli F, MacDonald KS, et al. Reduced HIV risk-taking and low HIV incidence after enrollment and risk-reduction counseling in a sexually transmitted disease prevention trial in Nairobi, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(1):69–72. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200205010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nunn A, Dickman S, Cornwall A, Kwakwa H, Mayer KH, Rana A, et al. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African American women in Philadelphia: results from a qualitative study. Sexual health. 2012;9(3):288–96. doi: 10.1071/SH11099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grieb SM, Davey-Rothwell M, Latkin CA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among urban African American high-risk women with main sex partners. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):323–33. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9954-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poundstone KE, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD. The social epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Epidemiologic reviews. 2004;26:22–35. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satterwhite CL, Kamb ML, Metcalf C, Douglas JM, Jr., Malotte CK, Paul S, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and STD prevalence among heterosexual STD clinic attendees: 1993-1995 versus 1999-2000. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2007;34(10):815–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31805c751d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooper HL, Linton S, Haley DF, Kelley ME, Dauria EF, Karnes CC, et al. Changes in Exposure to Neighborhood Characteristics are Associated with Sexual Network Characteristics in a Cohort of Adults Relocating from Public Housing. AIDS Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0883-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher RJ. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research. 1993:303–15. [Google Scholar]