Abstract

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is highly prevalent among patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), and the relationship between SDB and CVD may be bidirectional. However, SDB remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. One of the major barriers identified by cardiologists is lack of satisfaction with SDB therapy. This situation could be the result of the discordance between treatment and the pathophysiological characteristics of SDB. This condition is caused by multiple pathophysiological mechanisms, which could be classified into upper airway anatomic compromise, pharyngeal dilator muscle dysfunction, and ventilatory control instability. However, the effective treatment of SDB remains limited, and positive airway pressure therapy is still the mainstay of the treatment. Therefore, we review the pathophysiological characteristics of SDB in this article, and we propose to provide individualized treatment of SDB based on the underlying mechanism. This approach requires further study but could potentially improve adherence and success of therapy.

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) with daytime sleepiness was previously estimated to affect 4% of men and 2% of women in North America.1 However, recent data suggest that SDB is considerably more common at present, affecting approximately 13% of men and 6% of women. This increase is likely the result of increasing rates of obesity, an aging population, and improvements in technology to detect subtle respiratory events.2–4

The increasing prevalence is alarming, given the existing knowledge about the role of SDB as a cardiometabolic risk factor. SDB contributes to the development and progression of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, including heart failure, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality.5–8 These associations have been explained by multiple proposed mechanisms, although intermittent hypoxemia in SDB has emerged as the most prominent. Specifically, recurrent hypoxemia followed by reoxygenation resembles repetitive ischemia and reperfusion injury, which leads to sympathetic nervous system overactivity, systemic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and subsequent endothelial dysfunction.9–12 During an obstructive apnea event, strenuous inspiratory effort against an occluded upper airway leads to sympathetic overactivity, and the resultant negative intrathoracic pressure increases left ventricular afterload and right ventricular preload, which chronically increases myocardial oxygen demand and causes ventricular remodelling.13–15 Arousal at the end of an apneic episode also increases sympathetic activity and suppresses vagal tone, triggering the surge in blood pressure and heart rate.16

Emerging evidence suggests a reciprocal relationship in which cardiovascular disease (CVD) also leads to SDB (Fig. 1). Fluid redistributes from the extremities to the neck region because of the gravity effect of positional change from upright to supine during sleep and may contribute to upper airway edema and increased neck circumference, thus leading to upper airway mechanical obstruction.17 Optimization of diuresis and congestive heart failure (CHF) management should be the first-line treatment for these patients, because diuresis with furosemide and spironolactone in a nonrandomized trial demonstrated enlarged upper airway diameter and reduction in the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI).18 Furthermore, cardiac dysfunction may lead to ventilatory control instability, which is well known to cause central sleep apnea (CSA) and Cheyne-Stokes respiration (CSR), but may also result in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (Fig. 2).19,20 Also, pulmonary congestion enhances chemoreflex sensitivity and pulmonary irritant receptors, which result in unstable ventilatory control.21–23 Therefore, there seems to be at least a bidirectional relationship between SDB and CVD,24 if not a vicious cycle. Moreover, treatment of OSA has been associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes.25–27 Studies have demonstrated that treating OSA decreases recurrence of atrial fibrillation after ablation and cardioversion.28,29 The most recent 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association guidelines also made class IIa recommendations on the treatment of OSA in patients with heart failure.30

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the bidirectional relationship between sleep disordered breathing and congestive heart failure. RAS, reninangiotensin system; CSA, central sleep apnea; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide.

Figure 2.

(A) Recording of an unattended portable monitor demonstrates Cheyne-Stokes respiration during sleep in a patient with congestive heart failure. (B) An example of central sleep apnea from an unattended portable recording during sleep. (C) An example of obstructive sleep apnea from an unattended portable recording during sleep.

Despite the large burden of disease and the close association with CVD, SDB continues to be under-recognized and thus undertreated. Based on a 2011 American College of Cardiology Foundation survey among cardiologists, the major barriers to referring patients to sleep centres are lack of satisfaction with the effectiveness of sleep apnea therapy, the cost of a sleep study, and concerns over managing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy.31 Here, we focus on reviewing potential future SDB treatment with a new approach based on pathophysiological mechanisms of SDB (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mechanistic approach for treatment of sleep disordered breathing. ASV, adaptive servoventilation; CHF, congestive heart failure; EPAP, expiratory PAP; HGNS, hypoglossal nerve stimulator; MAD, mandibular advancement device; OPT, oral pressure therapy; PAP, positive airway pressure.

Behavioral Intervention for CPAP Adherence

Despite the large burden of disease, therapy for SDB remains unsatisfactory. CPAP is the treatment of choice, especially for OSA.32 Although CPAP therapy can be transformative for many patients, tolerance and adherence to CPAP have been a major hindrance for proper treatment of SDB for a major portion of patients.33–35 As many as 83% of patients who begin CPAP therapy are not optimally treated in that they do not use their CPAP device for even a minimum threshold of 4 hours per night on at least 70% of nights.34,36 This problem has led to studies testing interventions that include patient education,37,38 intensive support,39–41 behavioral therapies based on motivational interviewing,42 and cognitive behavioral therapy.43

Several studies have shown that intervention for treatment adherence needs to start as early as possible. Adherence in the first weeks predicts adherence at 6 months, which predicts long-term adherence.44 Further, those who have been able to maintain adherence tend to see greater symptom reductions.45 Despite this knowledge, adherence still remains poor, and behavioral approaches remain underused. Despite mounting evidence that these approaches can be helpful, efficacy of these interventions is suboptimal when they are available, and, in many cases patients do not have access to these interventions.35

A more mechanistic approach to SDB therapy may aid in this regard by more properly aligning patients with treatments and obviating the need for CPAP when an alternative can be provided. It should be noted, however, that alternative treatments also require adherence, and thus further study is clearly required.

Mechanistic Approach to SDB Therapy

Although CPAP has emerged as the first line of treatment, the problems associated with adherence have led to the exploration of alternative therapies such as oral appliances and upper airway surgery.32 These alternative therapies have variable efficacy, however, and it is difficult to reliably predict the rates or degree of response to these therapies based solely on clinical examination or baseline polysomnographic results.32,46 Thus, new therapeutic approaches and targets are greatly needed.

To improve treatment, the emerging concept is to provide individualized therapy for patients with SDB based on underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. Key causes of SDB could be classified into upper airway anatomical compromise, pharyngeal dilator muscle dysfunction, and ventilatory control instability. If we could accurately classify patients based on the primary causes of their SDB, targeted and individualized therapy could be offered to improve long-term therapeutic effectiveness.

Upper Airway Narrowing and Obstruction

Anatomic compromise

OSA is characterized by recurrent upper airway narrowing and closure. Traditionally, a narrowed upper airway resulting from various anatomic causes, such as thickened lateral pharyngeal walls from obesity, or from genetic predisposition, have been proposed to be the major mechanism for OSA.47–49 If anatomic narrowing is the predominant factor, it is plausible to suggest that surgical procedures to correct the anatomic narrowing could be effective treatment. In practice, however, surgical interventions have demonstrated limited effectiveness in unselected patients.32 The upper airway is a dynamic structure, balanced by neuromuscular activities and compensatory reflexes during sleep.50,51 The narrowest point of the pharynx during wakefulness is not necessarily the critical point of narrowing during sleep.50,52 Thus, despite ongoing efforts, no optimal clinical evaluation or investigation to predict the outcomes of surgical treatment of OSA on an individual basis has been identified.32

Recently, computer modelling with finite element analysis has been applied to evaluate the impact of surgical manipulations on individual upper airway anatomy.53–55 The baseline upper airway anatomy is constructed based on the individual patient’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and physiological measurement. It is hypothesized that with computer modelling of postsurgical upper airway changes, the surgical effect on the upper airway with specific procedures such as mandibular advancement or uvulopalatopharyngoplasty might be predicted with better accuracy. This approach has been validated in other areas using brain imaging for neurosurgery,56,57 but it needs further evaluation to apply to OSA treatment. If the outcome of a future surgical intervention could be predicted on an individual basis, patients might be able to avoid an ineffective procedure. Similarly, this concept could be used for oral appliance selection.54

A novel oral pressure therapy (OPT) system that provides negative pressure through gentle suction to the oral cavity has been shown to reduce AHI moderately in selected patients with OSA in preliminary studies.58,59 This new therapy increases the size of the retropalatal airway by drawing the soft palate and tongue forward.60 It should be noted that OPT may decrease the retroglossal airway caliber, so further study will be required to determine for whom this therapy may be a viable alternative for upper airway anatomic compromise with intolerance of CPAP therapy.60,61

Muscular control of upper airway

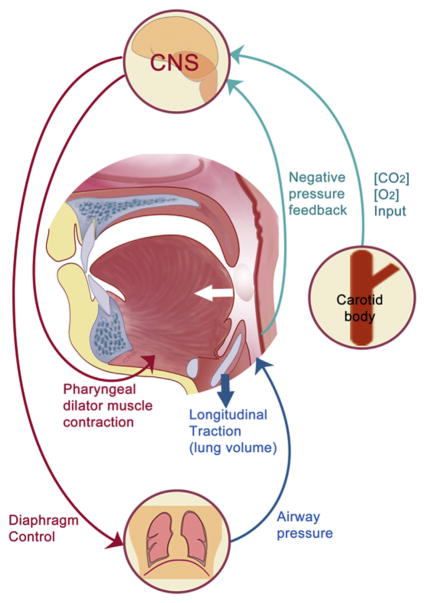

During wakefulness, the pharyngeal dilator muscles, including the genioglossus and tensor palatini muscles, are critical in maintaining airway patency.62 Upper airway muscles are activated by brain stem motor neurons and in response to respiratory stimuli, including pressure changes and CO2 level through compensatory reflexes (Fig. 4).63,64 However, decreases in brain stem motor neuron activity and attenuation of protective reflexes during sleep lead to a decrease in pharyngeal dilator muscle activity, which results in collapse or flow limitation in those anatomically vulnerable.65,66

Figure 4.

Neuromuscular control of upper airway patency. CNS, central nervous system.

Responsiveness of the pharyngeal dilator muscles to stimuli during sleep is highly variable in patients with OSA.67 In patients with minimal responsiveness of the pharyngeal dilator muscles during sleep, arousal is generally required to restore airway patency.68 It has been observed that most patients with OSA have some period of stable breathing, which is associated with elevated activity in the genioglossus muscle.67,69 This finding further suggests that the genioglossus muscle is both necessary and sufficient to stabilize breathing during sleep. The neural circuitry activating the genioglossus in response to negative intrapharyngeal pressure has recently been discovered in the periobex region of the medulla.70,71 This region of neurons contains heavy cholinergic staining,71 suggesting acetylcholine may be a potential therapeutic target for selected patients with OSA. It is possible that cholinergic agents might improve the responsiveness of the negative pressure reflex. Targeting this cholinergic pathway may improve OSA in selected patients with minimal responsiveness of the pharyngeal dilator muscle. Although the mechanism of acetylcholine on genioglossus control is still unclear, some preliminary clinical data have shown efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in OSA.72

The pharyngeal dilator muscles receive constant input from the hypoglossal motor nucleus and the motor branch of the trigeminal nerve.65 During sleep, the activity of brain stem motor neurons decreases during sleep, especially during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.73 The neurochemistry of these brain stem regions is complex, involving serotonergic, adrenergic, cholinergic, and histaminergic systems.74 There are potential pharmacologic targets that could be hypothesized to enhance the brain stem motor neuron output to the pharyngeal dilator muscles, but further research is needed.72 In addition, activation of the genioglossus muscle by hypoglossal nerve stimulation through an implantable device has been shown to be effective in reducing AHI and quality of life in a subset of patients with OSA.75,76

Lung volume

During sleep, upper airway resistance increases and functional residual capacity decreases normally. However, recent investigations indicate that end-expiratory lung volume (EELV) correlates with upper airway stability because increases in EELV provide traction caudally on the upper airway, which decreases its collapsibility.77–79 EELV might be another mechanism linking obesity and upper airway stability, because central adiposity of the viscera and chest decreases EELV.80 One of the novel therapies that applies this concept is the nasal expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) device, which consists of small 1-way valves that are fitted through the nostrils to generate EPAP by spontaneous breathing.81 Other manipulations of EELV through extrathoracic pressure, medications, or electrical stimulation of the phrenic nerve have not been systematically studied; however, results of EELV manipulation have thus far been disappointing.79

Ventilatory Control Instability

Arousal threshold

Ventilation is tightly controlled with multiple feedback loops to maintain oxygen and carbon dioxide levels within narrow ranges. The transition from wakefulness to sleep is an inherently unstable period of ventilatory control because of multiple physiological changes, such as chemosensitivity to CO2, with sleep onset.51 Even in healthy individuals, an irregular breathing pattern with apnea/hypopnea at sleep onset may occur.82,83 Similarly, ventilatory control can become unstable during arousal, depending on arousal threshold and ventilatory response to arousal, which could lead to increases in apnea/hypopnea.84 Arousal threshold is defined as the propensity to awaken from sleep; some individuals who have low arousal threshold (ie, easy to wake up) may experience repetitive apnea or CSA as the individual oscillates between wakefulness and sleep.64,84 In contrast, arousal also serves as a protective mechanism and individuals with a high arousal threshold (ie, difficult to wake up) may experience profound hypoxemia and hypercapnia preceding arousal.68,84 Therefore, increasing the arousal threshold could theoretically be beneficial to stabilize the breathing for certain patients, but this approach could be deleterious and worsen nocturnal hypoxemia for others. Sedative hypnotic agents such as trazodone and eszopiclone have shown various effects, including increases of the apneic threshold and improvement in AHI in small studies.85,86 These medications could potentially be used as adjuvant therapy for SDB if patients who may benefit from manipulation of the arousal threshold could be identified.

Loop gain

Loop gain of the ventilatory control system is a concept developed from the engineering field and is used to describe the ventilatory system response (changes in ventilation) to a ventilatory disturbance (such as apnea or hypopnea) within a negative feedback control system.87 A high loop gain system is susceptible to ventilatory oscillations and instability, and this concept is important to the pathogenesis of both OSA and CSA.20,51 Patients with CHF are at risk for the development of a Cheyne-Stokes breathing (CSB) pattern, a characteristic crescendo-decrescendo ventilatory pattern.88 This pattern is thought to result from a combination of high loop gain resulting from delayed circulatory time and heightened chemosensitivity caused by pulmonary congestion and decreased cardiac function.21,51 Thus, optimization of cardiac function and elimination of pulmonary congestion are the primary therapy for CSB. Cardiac function optimization occurs through medications,88–90 devices such as cardiac resynchronization therapy,91 or even heart transplantation.92 For patients with residual CSB despite maximal cardiac treatment, nasal CPAP may be helpful by reducing cardiac preload and afterload, although positive outcome data are lacking.93 Adaptive servoventilation (ASV) is similar to CPAP, except that it automatically adjusts pressure support based on monitoring of ventilation; this approach has emerged as a therapy for stabilizing ventilation and decreasing AHI in CSR.94,95 Three large-scale randomized controlled trials (NCT01128816, NCT00733343, and NCT01807897) are currently under way to assess clinical outcomes of ASV treatment for CSB/CSA in CHF. Other miscellaneous therapies, including oxygen, increased dead space, and inspired carbon dioxide, have improved AHI in an effort to decrease the loop gain of the feedback system.96,97 Similarly, acetazolamide and theophylline have shown comparable effects.98,99 However, more studies are required to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of these treatment options.

Phrenic nerve stimulation, which was previously used for ventilatory failure caused by congenital impairment or spinal cord injuries, has recently shown effective modulation of ventilation for CSB/CSA in patients with CHF in 2 recent small trials.100,101 It was postulated that unilateral phrenic nerve stimulation may attenuate minute ventilation and reduce the oscillation of the CO2 level. More evidence from long-term outcomes is needed in the context of treatment of CSA.61

Personalized Characterization of the Pathophysiological Traits

Recent advances have been made in quantifying the pathophysiological traits of OSA discussed earlier in individual patients with noninvasive techniques similar to study of CPAP titration.102,103 With these trait measurements, afflicted patients can be further categorized into 4 groups, each of which has a different estimated response to various therapies.104 Furthermore, an integrative model was developed to provide mathematical prediction for therapy based on the pathophysiological traits.105 However, the technique to measure these pathophysiological traits is currently limited to the research setting. Therefore, some recent research has demonstrated methods using regular polysomnography tracings to quantify these pathophysiologic traits such as arousal threshold or loop gain.106,107 For example, some of the CPAP nonresponders may have a low arousal threshold, which can be identified by simply reviewing the nadir oxygen saturation, AHI, and fraction of the AHI that showed hypopnea on clinical polysomnography.107 For these patients with a low arousal threshold, sedatives such as eszopiclone or trazodone may increase the arousal threshold and decrease the AHI.85,86 In the foreseeable future, clinicians will be able to tailor SDB treatment based on polysomnography data with an integrated computer model that identifies the pathophysiological traits and the treatment options with a predicted individualized response rate. This vision of personalized medicine for SDB is ambitious but attainable, at least for some patients.

Conclusions

SDB and CVD are closely interlinked. Untreated SDB is a risk factor for the development or progression of CVD, and CVD is also a risk factor for both OSA and CSA. Because variable pathophysiological mechanisms contribute to SDB, a mechanistic approach for treatment may potentially improve the effectiveness and efficacy of current and emerging therapies for SDB. Further efforts involving the use of knowledge about individual-level pathogenesis to guide treatment in SDB is urgently needed given the considerable burden of untreated disease. Further, treatment approaches that more closely align with specific pathogenesis may more directly address the disease at an individualized level and increase adherence to therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

A.M. is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosselet JJ, Norman RG, Ayappa I, Rapoport DM. Detection of flow limitation with a nasal cannula/pressure transducer system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1461–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9708008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McTigue K, Kuller L. Cardiovascular risk factors, mortality, and overweight. JAMA. 2008;299:1260–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1260-c. author reply 1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tufik S, Santos-Silva R, Taddei JA, Bittencourt LR. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the Sao Paulo Epidemiologic Sleep Study. Sleep Med. 2010;11:441–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gami AS, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hung J, Whitford EG, Parsons RW, Hillman DR. Association of sleep apnoea with myocardial infarction in men. Lancet. 1990;336:261–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91799-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep. 2008;31:1071–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavie L. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome—an oxidative stress disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:35–51. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan S, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Selective activation of inflammatory pathways by intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Circulation. 2005;112:2660–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.556746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walford GA, Moussignac RL, Scribner AW, Loscalzo J, Leopold JA. Hypoxia potentiates nitric oxide-mediated apoptosis in endothelial cells via peroxynitrite-induced activation of mitochondria-dependent and -independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4425–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnoea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet. 2009;373:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley TD, Hall MJ, Ando S, Floras JS. Hemodynamic effects of simulated obstructive apneas in humans with and without heart failure. Chest. 2001;119:1827–35. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.6.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usui K, Parker JD, Newton GE, et al. Left ventricular structural adaptations to obstructive sleep apnea in dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1170–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-320OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horner RL, Brooks D, Kozar LF, Tse S, Phillipson EA. Immediate effects of arousal from sleep on cardiac autonomic outflow in the absence of breathing in dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:151–62. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yumino D, Redolfi S, Ruttanaumpawan P, et al. Nocturnal rostral fluid shift: a unifying concept for the pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea in men with heart failure. Circulation. 2010;121:1598–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.902452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucca CB, Brussino L, Battisti A, et al. Diuretics in obstructive sleep apnea with diastolic heart failure. Chest. 2007;132:440–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tkacova R, Niroumand M, Lorenzi-Filho G, Bradley TD. Overnight shift from obstructive to central apneas in patients with heart failure: role of PCO2 and circulatory delay. Circulation. 2001;103:238–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Younes M, Ostrowski M, Thompson W, Leslie C, Shewchuk W. Chemical control stability in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1181–90. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2007013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Javaheri S. A mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:949–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorenzi-Filho G, Azevedo ER, Parker JD, Bradley TD. Relationship of carbon dioxide tension in arterial blood to pulmonary wedge pressure in heart failure. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:37–40. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00214502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun SY, Wang W, Zucker IH, Schultz HD. Enhanced peripheral chemoreflex function in conscious rabbits with pacing-induced heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1264–72. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasai T, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: a bidirectional relationship. Circulation. 2012;126:1495–510. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arzt M, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP) Circulation. 2007;115:3173–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javaheri S, Caref EB, Chen E, Tong KB, Abraham WT. Sleep apnea testing and outcomes in a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:539–46. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0406OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fein AS, Shvilkin A, Shah D, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:300–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;107:2589–94. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068337.25994.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang E, Loo G, Lee CH. [Accessed October 15, 2014];Sleep Apnea and the Heart—the Singapore Experience. Available at: http://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2014/07/18/15/46/sleep-apnea-and-the-heart-the-singapore-experience?w_nav=S.

- 32.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Jr, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gay P, Weaver T, Loube D, et al. Evaluation of positive airway pressure treatment for sleep related breathing disorders in adults. Sleep. 2006;29:381–401. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weaver TE, Kribbs NB, Pack AI, et al. Night-to-night variability in CPAP use over the first three months of treatment. Sleep. 1997;20:278–83. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.4.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wozniak DR, Lasserson TJ, Smith I. Educational, supportive and behavioural interventions to improve usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD007736. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007736.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:173–8. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-119MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golay A, Girard A, Grandin S, et al. A new educational program for patients suffering from sleep apnea syndrome. Patient education and counseling. 2006;60:220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiese H, Boethel C, Phillips B, et al. CPAP compliance: video education may help! Sleep Med. 2005;6:171–4. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hui DS, Chan JK, Choy DK, et al. Effects of augmented continuous positive airway pressure education and support on compliance and outcome in a Chinese population. Chest. 2000;117:1410–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stepnowsky CJ, Palau JJ, Marler MR, Gifford AL. Pilot randomized trial of the effect of wireless telemonitoring on compliance and treatment efficacy in obstructive sleep apnea. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoy CJ, Vennelle M, Kingshott RN, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Can intensive support improve continuous positive airway pressure use in patients with the sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1096–100. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9808008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aloia MS, Smith K, Arnedt JT, et al. Brief behavioral therapies reduce early positive airway pressure discontinuation rates in sleep apnea syndrome: preliminary findings. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5:89–104. doi: 10.1080/15402000701190549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richards D, Bartlett DJ, Wong K, Malouff J, Grunstein RR. Increased adherence to CPAP with a group cognitive behavioral treatment intervention: a randomized trial. Sleep. 2007;30:635–40. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Zeller M, Severo M, Santos AC, Drummond M. 5-years APAP adherence in OSA patients—do first impressions matter? Respir Med. 2013;107:2046–52. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30:711–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, Schmidt-Nowara W. Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep. 2006;29:244–62. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fogel RB, Malhotra A, Dalagiorgou G, et al. Anatomic and physiologic predictors of apnea severity in morbidly obese subjects. Sleep. 2003;26:150–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwab RJ, Gupta KB, Gefter WB, et al. Upper airway and soft tissue anatomy in normal subjects and patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Significance of the lateral pharyngeal walls. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1673–89. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.5.7582313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwab RJ, Pasirstein M, Kaplan L, et al. Family aggregation of upper airway soft tissue structures in normal subjects and patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:453–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1736OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckert DJ, Malhotra A. Pathophysiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:144–53. doi: 10.1513/pats.200707-114MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White DP. Pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1363–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1631SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haponik EF, Smith PL, Bohlman ME, et al. Computerized tomography in obstructive sleep apnea. Correlation of airway size with physiology during sleep and wakefulness. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:221–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Y, Malhotra A, White DP. Computational simulation of human upper airway collapse using a pressure-/state-dependent model of genioglossal muscle contraction under laminar flow conditions. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1138–48. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00668.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Y, White DP, Malhotra A. The impact of anatomic manipulations on pharyngeal collapse: results from a computational model of the normal human upper airway. Chest. 2005;128:1324–30. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Y, White DP, Malhotra A. Use of computational modeling to predict responses to upper airway surgery in obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:648–53. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318030ca55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hagemann A, Rohr K, Stiehl HS. Coupling of fluid and elastic models for biomechanical simulations of brain deformations using FEM. Med Image Anal. 2002;6:375–88. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(02)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park HK, Dujovny M, Park T, Diaz FG. Application of finite element analysis in neurosurgery. Child Nerv Dys. 2001;17:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s003819900245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colrain I, Bogan R, Becker P, et al. A multi-center evaluation of oral pressure therapy for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Paper presented at: 21st Congress of the European Sleep Research Society; September 4–8, 2012; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwab RJ, Kim C, Siegel L, et al. Mechanism of action of a novel device using oral pressure therapy (OPT) for the treatment of OSA. Paper presented at: American Thoracic Society 2012 International Conference; May 18–23, 2012; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwab RJ, Kim C, Siegel L, et al. Examining the mechanism of action of a new device using oral pressure therapy for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2014;37:1237–47. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park JG, Morgenthaler TM, Gay PC. Novel and emerging nonpositive airway pressure therapies for sleep apnea. Chest. 2013;144:1946–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mezzanotte WS, Tangel DJ, White DP. Waking genioglossal electromyogram in sleep apnea patients versus normal controls (a neuromuscular compensatory mechanism) J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1571–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hudgel DW, Martin RJ, Johnson B, Hill P. Mechanics of the respiratory system and breathing pattern during sleep in normal humans. J Appl Physiol. 1984;56:133–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stanchina ML, Malhotra A, Fogel RB, et al. Genioglossus muscle responsiveness to chemical and mechanical stimuli during non-rapid eye movement sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:945–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2108076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horner RL. Motor control of the pharyngeal musculature and implications for the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1996;19:827–53. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.10.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horner RL. The neuropharmacology of upper airway motor control in the awake and asleep states: implications for obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir Res. 2001;2:286–94. doi: 10.1186/rr71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jordan AS, White DP, Lo YL, et al. Airway dilator muscle activity and lung volume during stable breathing in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2009;32:361–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillipson EA, Sullivan CE. Arousal: the forgotten response to respiratory stimuli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:807–9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.5.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berry RB, Gleeson K. Respiratory arousal from sleep: mechanisms and significance. Sleep. 1997;20:654–75. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.8.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chamberlin NL, Eikermann M, Fassbender P, White DP, Malhotra A. Genioglossus premotoneurons and the negative pressure reflex in rats. J Physiol. 2007;579:515–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Volgin DV, Rukhadze I, Kubin L. Hypoglossal premotor neurons of the intermediate medullary reticular region express cholinergic markers. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1576–84. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90670.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moraes W, Poyares D, Sukys-Claudino L, Guilleminault C, Tufik S. Donepezil improves obstructive sleep apnea in Alzheimer disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Chest. 2008;133:677–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wiegand L, Zwillich CW, Wiegand D, White DP. Changes in upper airway muscle activation and ventilation during phasic REM sleep in normal men. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:488–97. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.2.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwartz JR, Roth T. Neurophysiology of sleep and wakefulness: basic science and clinical implications. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6:367–78. doi: 10.2174/157015908787386050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mwenge GB, Rombaux P, Dury M, Lengele B, Rodenstein D. Targeted hypoglossal neurostimulation for obstructive sleep apnoea: a 1-year pilot study. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:360–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00042412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Strollo PJ, Jr, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, et al. Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:139–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Begle RL, Badr S, Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Effect of lung inflation on pulmonary resistance during NREM sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:854–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.4_Pt_1.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heinzer RC, Stanchina ML, Malhotra A, et al. Lung volume and continuous positive airway pressure requirements in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:114–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-552OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heinzer RC, Stanchina ML, Malhotra A, et al. Effect of increased lung volume on sleep disordered breathing in patients with sleep apnoea. Thorax. 2006;61:435–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.052084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ray CS, Sue DY, Bray G, Hansen JE, Wasserman K. Effects of obesity on respiratory function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:501–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Braga CW, Chen Q, Burschtin OE, Rapoport DM, Ayappa I. Changes in lung volume and upper airway using MRI during application of nasal expiratory positive airway pressure in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:1400–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00218.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dunai J, Wilkinson M, Trinder J. Interaction of chemical and state effects on ventilation during sleep onset. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:2235–43. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.5.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khoo MC, Gottschalk A, Pack AI. Sleep-induced periodic breathing and apnea: a theoretical study. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:2014–24. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.5.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Younes M. Role of arousals in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:623–33. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200307-1023OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eckert DJ, Owens RL, Kehlmann GB, et al. Eszopiclone increases the respiratory arousal threshold and lowers the apnoea/hypopnoea index in obstructive sleep apnoea patients with a low arousal threshold. Clin Sci. 2011;120:505–14. doi: 10.1042/CS20100588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heinzer RC, White DP, Jordan AS, et al. Trazodone increases arousal threshold in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1308–12. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00067607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cherniack NS. Respiratory dysrhythmias during sleep. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:325–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108063050606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Solin P, Bergin P, Richardson M, et al. Influence of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure on central apnea in heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99:1574–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.12.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baylor P, Tayloe D, Owen D, Sanders C. Cardiac failure presenting as sleep apnea. Elimination of apnea following medical management of cardiac failure. Chest. 1988;94:1298–300. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.6.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dark DS, Pingleton SK, Kerby GR, et al. Breathing pattern abnormalities and arterial oxygen desaturation during sleep in the congestive heart failure syndrome. Improvement following medical therapy. Chest. 1987;91:833–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sinha AM, Skobel EC, Breithardt OA, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy improves central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mansfield DR, Solin P, Roebuck T, et al. The effect of successful heart transplant treatment of heart failure on central sleep apnea. Chest. 2003;124:1675–81. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2025–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pepperell JC, Maskell NA, Jones DR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of adaptive ventilation for Cheyne-Stokes breathing in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1109–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200212-1476OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Teschler H, Dohring J, Wang YM, Berthon-Jones M. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation: a novel treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:614–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.9908114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lorenzi-Filho G, Rankin F, Bies I, Douglas Bradley T. Effects of inhaled carbon dioxide and oxygen on cheynestokes respiration in patients with heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1490–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9810040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wellman A, Malhotra A, Jordan AS, et al. Effect of oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea: role of loop gain. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;162:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Javaheri S. Acetazolamide improves central sleep apnea in heart failure: a double-blind, prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:234–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1035OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Wexler L, et al. Effect of theophylline on sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:562–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ponikowski P, Javaheri S, Michalkiewicz D, et al. Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation for the treatment of central sleep apnoea in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:889–94. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang XL, Ding N, Wang H, et al. Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation in patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration and congestive heart failure: a safety and proof-of-concept study. Chest. 2012;142:927–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wellman A, Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, et al. A method for measuring and modeling the physiological traits causing obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110:1627–37. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00972.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wellman A, Edwards BA, Sands SA, et al. A simplified method for determining phenotypic traits in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114:911–22. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00747.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eckert DJ, White DP, Jordan AS, Malhotra A, Wellman A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:996–1004. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0448OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Owens RL, Edwards BA, Eckert DJ, et al. An integrative model of physiological traits can be used to predict obstructive sleep apnea and response to non positive airway pressure therapy. [Accessed December 18, 2014];Sleep. 2014 doi: 10.5665/sleep.4750. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Terrill PI, Edwards BA, Nemati S, et al. Quantifying the ventilatory control contribution to sleep apnoea using polysomnography. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:408–18. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00062914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Edwards BA, Eckert DJ, McSharry DG, et al. Clinical predictors of the respiratory arousal threshold in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1293–300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0718OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]