Abstract

Purpose

Graves' orbitopathy (GO) is associated with changes in the appearance of the eyes and visual dysfunction. Patients report feeling socially isolated and unable to continue with day-to-day activities. This study aimed at investigating the demographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors associated with quality of life in patients presenting for orbital decompression surgery.

Methods

One-hundred and twenty-three adults with GO due for orbital decompression at Moorfields Eye Hospital London were recruited prospectively. Clinical measures including treatment history, exophthalmos, optic neuropathy, and diplopia were taken by an ophthalmologist. Participants completed psychosocial questionnaires, including the Graves' Ophthalmopathy Quality of Life Scale (GO-QOL), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and the Derriford Appearance Scale. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to identify predictors of quality of life.

Results

Higher levels of potential cases of clinical anxiety (37%) and depression (26%) were found in this study sample than in patients with other chronic diseases or facial disfigurements. A total of 55% of the variance in GO-QOL visual function scores was explained by the regression model; age, asymmetrical GO and depressed mood were significant unique contributors. In all, 75% of the variance in GO-QOL appearance scores was explained by the regression model; gender, appearance-related cognitions and depressed mood were significant unique contributors.

Conclusion

Appearance-related quality of life and mood were particularly affected in this sample. Predominantly psychosocial characteristics were associated with quality of life. It is important when planning surgery for patients that clinicians be aware of factors that could potentially influence outcomes.

Introduction

Graves' orbitopathy (GO) is an autoimmune thyroid disorder that affects the eyes. An estimated 25–50% of patients with Graves' disease develop GO.1 The most common early symptom of GO is a noticeable change in the appearance of the eyes, including redness of the eyelids, swelling, and disfiguring proptosis.2

Patients with GO report feeling stared at by others and socially isolated as a consequence of their changed appearance3 and this has a significant impact on mood.4 There is also growing evidence that GO has a detrimental impact on vision-related daily functioning including reading, watching TV, and driving.5, 6, 7 People with GO have been found to have a poorer quality of life than patients with other chronic conditions including diabetes, emphysema, and heart failure.4, 8 Although it is important to establish the impact GO may have on a patient's well-being, it is equally important to understand what factors explain how some people live within normal levels of mood and experience a better quality of life than others.

There is mixed evidence to support an association between clinical factors and quality of life in GO. For instance, although Park et al7 found that poorer quality of life was associated with more severe disease, including diplopia and dry eyes, Kulig et al9 failed to replicate these findings either before or after treatment for GO. Recent literature about appearance and disfigurement has suggested significant variability amongst individuals with disfiguring conditions—with many adjusting positively to living with a visible difference—and that psychological processes rather than objective measurements can better explain this variability in adjustment.10, 11 In GO, Kahaly et al4 found that depressive coping, trivialising the condition, and higher levels of emotional distress were associated with poorer physical and mental quality of life. However, other psychosocial variables, identified within a framework for adjustment to disfigurement as proposed by The Appearance Research Collaboration,11 have not been investigated within the GO population. The framework suggests that a number of intervening cognitive processes, individual to each patient, might help explain the quality of life in people with a disfiguring condition.

It was hypothesised that there will be large variation in quality of life between individuals with GO, and that intervening psychosocial processes would better explain this variation than demographic or clinical factors.

Materials and methods

Participants

Patients were recruited from Moorfields Eye Hospital, London. Eligible patients aged 18 years or more with a consultant-led diagnosis of GO, and having been listed for orbital decompression surgery, were invited to participate in the study by a researcher (SW). Patients were excluded if they were considered by the consultant ophthalmologist to have inadequate comprehension of written and spoken English, or were suffering from psychiatric or co-morbid health conditions that rendered them too ill or distressed to take part.

Study design

A prospective cross-sectional design was used.

Measures

Demographics

Self-reported age, gender, marital status, and ethnicity were collected.

Clinical measures

The clinical measures assessed when patients were listed for surgery included ophthalmic disease duration, thyroid function, treatment history, laterality of GO and planned surgery, smoking status, upper and lower margin-reflex distance (MRD1 and MRD2; mm), and the presence of corneal superficial punctate keratopathy, diplopia, and/or signs of hydraulic orbital disease. Disease activity was measured using the Clinical Activity Scale,12 a 10-item measure covering four of the five classic signs of inflammation (pain, redness, swelling, and impaired ocular function). Visual acuity was measured for each eye using a Snellen Chart. This was converted to the log of the minimal angle of resolution, ranging between −0.20 and 2.1, with a score of 2.2 assigned to patients with vision of counting fingers or worse. Optic neuropathy was identified using Ishihara colour testing and the presence of a relative afferent pupillary defect. Proptosis was measured using an Oculus exophthalmometer (in mm), and the degree of asymmetry gauged from the difference between each eye (in mm).

Psychosocial measures

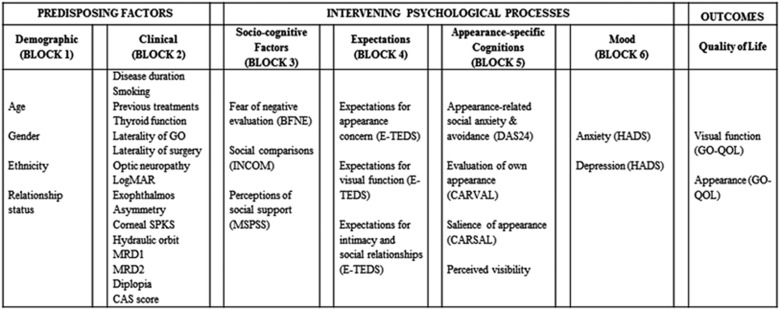

Self-report questionnaires were completed by participants at the time they were listed for surgery. The questionnaires chosen for this study were based on a proposed framework of adjustment to GO developed by the research team (Figure 1) adapted from The Appearance Research Collaboration's framework.11 Existing validated measures were used where possible, and brief versions of questionnaires were adopted to reduce participant burden.

Figure 1.

The potential variables to be used in hierarchical multiple regressions to explore factors associated with quality-of-life scores. The framework is adapted from The Appearance Research Collaboration.11

Primary outcome measure

Quality of life was measured using the Australian version of Graves' Ophthalmopathy Quality of Life Questionnaire (GO-QOL).7 The GO-QOL is made up of two subscales: ‘vision-related' and ‘appearance-related' quality of life.5 The GO-QOL has been found to be a valid and reliable disease-specific measure of quality of life with high internal consistency (α=0.86 for the visual function scale and α=0.82 for the appearance scale).13 Subscale scores were calculated by following the questionnaire guidelines,13 and higher scores on each subscale indicate better health-related quality of life.

Socio-cognitive factors

The Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale14 was used to measure anxiety about others' opinions. This 12-item brief version correlates highly with the original scale (α=0.96), and higher scores indicate a greater fear of negative evaluation from others.

The Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure15 measures how well respondents feel they are doing in life when comparing him or herself with others. This 11-item scale has been demonstrated to have good internal consistency (α=0.83), and higher scores indicate a greater tendency to make social comparisons.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support16 measures subjective levels of social support from family, friends, and significant others. The overall scale has demonstrated good internal consistency (α=0.88) and test–retest reliability (r=0.85). Higher scores on each 4-item subscale indicate greater perceived social support.

Patient expectations of treatment

Expectations of GO surgery: In the absence of a GO-specific measure of a patients' expectations of treatment, an existing questionnaire—the Expectations of Strabismus Surgery Questionnaire17—was adapted with the items being reviewed for relevance to GO. The 23-item questionnaire assessed patients' expectations in relation to three domains: ‘appearance concerns', ‘visual functioning', and ‘intimacy and social relationships'. Participants were instructed to rate how they expected surgery to change these aspects of their lives, for instance ‘my vision' on a Likert scale from 1 (‘Made considerably worse') to 5 (‘Considerably improve'). Higher scores indicate a greater expectation for these areas to improve after surgery.

Appearance-specific cognitions

The Derriford Appearance Scale18 measures the impact of appearance-related distress including social anxiety and avoidance. This measure has demonstrated high internal consistency (α=0.92) and good test–retest reliability (r=0.82), and higher scores represent greater levels of appearance-related distress and social avoidance.

The Valence and Salience of Appearance scales (CARVAL & CARSAL)19 measure how an individual evaluates his or her own physical appearance (CARVAL) and the extent to which physical appearance is important to the individual (CARSAL). Higher scores on each brief measure indicate a more negative self-evaluation of appearance and that greater value is placed on appearance, respectively. Both questionnaires have demonstrated high internal consistency (Pearson's r correlations between 0.72 and 0.84).

Perceived Visibility of GO: patients were asked to rate how visible they felt their proptosis was to other people on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (‘Not at all visible') to 7 (‘Extremely visible').

Mood

The Hospital Anxiety & Depression scale (HADS)20 has been designed to screen for depression and anxiety in patients with health problems. Higher total subscale scores on this valid and reliable measure indicate greater levels of anxious or depressed mood. Cut-off scores were also applied to identify non-cases (0–7), doubtful cases (8–10), and cases of possible clinical anxiety or depression (scores of 11 and over).

Statistical analysis

Using G*Power (version 3.1.7, Franz Faul, Universitat Kiel, Kiel, Germany), it was estimated that between 64 and 97 patients would be needed to achieve a power of 90% with effect sizes of 0.45 and 0.9 for the GO-QOL appearance and GO-QOL visual function subscales, respectively.13

All other statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 21 (IBM UK Ltd, Portsmouth, UK). Levels of missing data, analysed using Little's Missing Completely at Random test, were shown to be Missing Completely at Random (χ2=7127, df=8177, P=1.000), with 11.9% of the data missing at item level. Multiple imputation was undertaken, and 10 imputed data sets were generated. Scale scores for the psychosocial variables were re-calculated and the analysis was conducted on all 10 data sets and the results were pooled.

Univariate linear regressions were performed to explore the relationship between each of the independent variables and the GO-QOL subscale scores (dependent variables). Hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted using only the variables that were found to be significantly associated with each GO-QOL subscale. The hierarchy used to enter the predictors into the regression was based on the framework outlined in Figure 1. Cohen's f2 was used to calculate effect sizes for each of these regressions.21 The variables were also examined for multicollinearity, linearity, and homoscedasticity. Multicollinearity was identified using VIF scores provided in SPSS after each regression analysis, with scores above 10 indicating multicollinearity.22 Histograms and normal probability plots were assessed for linearity and homoscedasticity.

Statement of ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the North London Research Ethics Committee (reference 11/H0724/6). We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Results

Among 192 patients identified as eligible for the study, 135 (70%) agreed to take part, and 123 of the 135 enrolled (91%) returned their questionnaire. Two participants' data were removed from analysis because of high proportions of missing data (>50%).

The descriptive characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample.

| Variable | n (%) | Range | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22–79 | 47.1±12.3 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 33 (27) | ||

| Female | 88 (73) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 11 (9.1) | ||

| White British/Irish/other | 95 (78) | ||

| Black African/Caribbean/other | 15 (12) | ||

| Relationship status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 73 (60) | ||

| Single/other | 48 (40) | ||

| Disease duration (months) | 4–336 | 62.01±42 | |

| Laterality of GO | |||

| Bilateral | 101 (83) | ||

| Unilateral | 20 (17) | ||

| Laterality of planned surgery | |||

| Bilateral | 79 (65) | ||

| Unilateral | 42 (35) | ||

| Treatment history | |||

| Previous immunosuppressants | 58 (48) | ||

| Previous radiotherapy | 18 (15) | ||

| Previous eyelid or orbital surgery | 14 (12) | ||

| Thyroid function | |||

| Stable | 106 (88) | ||

| Unstable | 15 (12) | ||

| Visual acuity (LogMAR conversion)a | 0–2 | 0.1±0.4 | |

| Superficial punctate keratopathy | 39 (32) | ||

| Hydraulic orbital signs | 25 (21) | ||

| Optic neuropathy | 15 (12) | ||

| Diplopia | 62 (51) | ||

| Marginal reflex distance 1 (mm)a | 1.5–13 | 5.9±2.1 | |

| Marginal reflex distance 2 (mm)a | 4–11 | 6.7±1.4 | |

| Exophthalmometry (mm)a | 15–33 | 23.7±2.7 | |

| Asymmetry (mm) | 0–8 | 1.8±1.8 | |

| Clinical activity score | 0–9 | 1.12±1.9 | |

| Smokers | 38 (31) | ||

A worst eye analysis was conducted on these variables, based on the amount of proptosis.

Summary statistics for the psychosocial variables are shown in Table 2. Possible cases of clinical depression were detected in 26% of patients, and 37% had possible clinical levels of anxiety; 25 (21%) participants experienced both. The large standard deviations for both GO-QOL subscales indicate great variability in adjustment from patient to patient.

Table 2. Scores for the psychosocial measures at baseline for the study sample.

| Variable | Min | Max | Max possible | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO-QOL appearance score | 0 | 93.8 | 100 | 36.3 | 24.1 |

| GOQOL visual function score | 2.8 | 100 | 100 | 64.0 | 26.7 |

| BFNE | 14 | 60 | 60 | 38 | 9.2 |

| INCOM | 16 | 54 | 55 | 36 | 7.2 |

| MSPSS family | 4 | 20 | 20 | 15.3 | 4.5 |

| MSPSS friends | 4 | 20 | 20 | 15.2 | 4.2 |

| MSPSS significant other | 4 | 20 | 20 | 15.6 | 5.2 |

| CARSAL | 5 | 30 | 30 | 25.2 | 4.7 |

| CARVAL | 11 | 48 | 48 | 38.7 | 8.4 |

| DAS24 | 22 | 83 | 96 | 51.3 | 13 |

| Men (n=33) | 22 | 83 | 96 | 50.7 | 15 |

| Women (n=88) | 22 | 83 | 96 | 51.6 | 12 |

| Visibility | 1 | 7 | 7 | 5.7 | 1.5 |

| HADS depression | 1 | 21 | 21 | 9.2 | 4.9 |

| HADS anxiety | 0 | 19 | 21 | 7.6 | 4.7 |

Ten of the original 36 variables were significantly associated with the GO-QOL visual function subscale using univariate analyses: age (F1,119=16.6, P<0.001, f2=0.14), optic neuropathy (F1,119=15.8, P<0.001, f2=0.15), log of the minimal angle of resolution (F1,119=15.6, P<0.001, f2=0.12), previous immunosuppression (F1,119=11.1, P=0.001, f2=0.09), asymmetrical GO (F1,119=6.12, P=0.015, f2=0.05), hydraulic orbit (F1,119=9.22, P=0.003, f2=0.06), diplopia (F1,119=7.77, P=0.006, f2=0.07), Clinical Activity Scale (F1,119=6.22, P=0.014, f2=0.05), appearance-related social anxiety and avoidance (F1,119=3.95, P=0.049, f2=0.06), anxiety (F1,119=12.9, P<0.001, f2=0.11), and depression (F1,119=41.6, P<0.001, f2=0.36).

After entry of these variables into the model in the order shown in Figure 1, 55% of the observed sample variation in GO-QOL visual function score was accounted for (R2=0.55, F1,119=9.89, P<0.001, f2=0.8). Beta-coefficients indicated that age, asymmetrical GO, and depression made significant unique contributions to the model, above other factors (Table 3).

Table 3. The final step of a hierarchical multiple regression model, with GO-QOL visual function score as the dependent variable.

| B | SE B | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 119.49 | 13.78 | 8.67 | 0.000** |

| Age | −0.50 | 0.19 | −2.63 | 0.009* |

| LogMAR | −11.28 | 6.45 | −1.75 | 0.080 |

| CAS | −1.92 | 1.31 | −1.46 | 0.144 |

| Asymmetry | −2.25 | 1.13 | −2.00 | 0.046* |

| Optic neuropathy | −4.09 | 9.54 | −0.43 | 0.669 |

| Hydraulic orbit | 2.55 | 6.47 | 0.39 | 0.694 |

| Previous immunomodulation | −6.79 | 4.90 | −1.38 | 0.168 |

| Diplopia | −4.39 | 4.29 | −1.02 | 0.307 |

| DAS24 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.815 |

| HADS anxiety | −0.69 | 0.58 | −1.20 | 0.231 |

| HADS depression | −2.41 | 0.59 | −4.10 | 0.000** |

*P<0.05, **P<0.001.

Univariate analyses indicated that 13/36 variables were significantly associated with GO-QOL appearance: age (F1,119=5.42, P=0.022, f2=0.05), gender (F1,119=8.13, P=0.005, f2=0.07), previous surgery (F1,119=5.55, P=0.020, f2=0.06), family support (F1,119=5.12, P=0.025, f2=0.04), friends support (F1,119=7.39, P=0.008, f2=0.06), fear of negative evaluation (F1,119=58.8, P<0.001, f2=0.52), social comparison (F1,119=12.2, P=0.001, f2=0.11), appearance-related social anxiety and avoidance (F1,119=60.0, P<0.001, f2=0.59), salience of appearance (F1,119=64.6, P<0.001, f2=0.51), valence of appearance (F1,119=98.9, P<0.001, f2=0.76), perceived visibility (F1,119=27.5, P<0.001, f2=0.24), anxiety (F1,119=42.2, P<0.001, f2=0.39), and depression (F1,119=70.5, P<0.001, f2=0.57).

After entry of the variables using the same model as before, 75% of the observed sample variation in GO-QOL appearance scores was accounted for (R2=0.75, F13,107=20.7, P<0.001, f2=2.3). Beta-coefficients indicated that gender, appearance-related social anxiety and social avoidance, salience of appearance, valence of appearance, perceived visibility of GO, and depression all made significant contributions to the model (Table 4).

Table 4. The final step of a hierarchical multiple regression model, with GO-QOL appearance-related score as the dependent variable.

| B | SE B | t | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 132.09 | 13.84 | 9.55 | 0.000** |

| Age | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 0.346 |

| Gender | 6.56 | 3.02 | 2.17 | 0.03* |

| Previous surgery | −5.04 | 5.08 | −0.99 | 0.325 |

| BFNE | −0.23 | 0.22 | −1.03 | 0.302 |

| INCOM | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.950 |

| MSPSS family | −0.29 | 0.34 | −0.87 | 0.382 |

| MSPSS friends | 0.56 | 0.37 | 1.53 | 0.127 |

| DAS24 | −0.39 | 0.13 | −2.93 | 0.004* |

| CARSAL | −1.23 | 0.33 | −3.69 | 0.000** |

| CARVAL | −0.58 | 0.21 | −2.76 | 0.006* |

| Perceived visibility | −2.75 | 0.96 | −2.86 | 0.004* |

| HADS anxiety | −0.05 | 0.39 | −0.14 | 0.891 |

| HADS depression | −1.12 | 0.43 | −2.60 | 0.009* |

*P<0.05, **P<0.001.

Discussion

This study investigated the factors that may be associated with quality of life in patients with GO presenting for orbital decompression surgery. It was found that being older, having asymmetrical proptosis, and having higher levels of depressed mood were associated with poorer vision-related quality of life. Similarly, a greater value being placed on appearance, a more negative evaluation of appearance, greater perceived visibility of GO, and having higher levels of depressed mood were all associated with poorer appearance-related quality of life.

Participants in this study experienced levels of anxiety and depression greater than the general population23 and those living with other visibly disfiguring conditions.24 GO-QOL visual function scores were comparable to normative values established in a previous GO sample,13 but GO-QOL appearance scores were considerably lower. These results suggest that, for many, the changed appearance caused by GO has a greater impact and is more debilitating than previously reported in the literature.

Appearance-related quality of life was significantly associated with gender. For women, the eyes might be regarded as central in perceived attractiveness, and changes in ocular appearance could have a detrimental influence on self-confidence and willingness to appear in photographs. Recent studies have suggested that women with visible differences, including strabismus, may experience higher levels of appearance-related distress than men,25, 26 which in turn could have an impact on their quality of life in this domain. Furthermore, age was found to be associated with vision-related quality of life, which might reflect the greater disease severity often found in older age.

Appearance-related cognitions were particularly important in predicting appearance-related quality of life. Increased social anxiety was associated with both poorer vision-related and appearance-related quality of life in this study, analogous to strabismus.27 Increased importance of appearance-related information, as well as having a poorer evaluation of one's own appearance, were also associated with quality of life in this sample. Terwee et al28 found in a study investigating perceptions of the severity of GO in different groups of observers and patients themselves that clinicians tended to under-rate, and patients over-rate, the severity of GO: This emphasises the importance of eliciting a patient's perspective during pre-surgical assessment to improve the chance of generating realistic patient expectations about what surgery can achieve.

A limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design, which does not enable causal direction to be established and longitudinal studies that follow patients over time are needed. If patients in this study were not euthyroid, present hyper- or hypothyroidism could have affected their quality of life. However, recent research found no difference in the quality of life of people with thyroid dysfunction compared with people with normal thyroid levels,29 and it is possible that this may not have biased the results of this study. It is also possible that quality of life may predict mood in GO. However, mood has been found to be a strong predictor of quality of life in strabismus,24 supporting the current findings. Furthermore, by exploring other factors that might explain variance in quality of life in this population, rather than examining quality of life and mood in isolation, this study has expanded on previous studies and has provided a new insight into the experiences of patients with GO.

In conclusion, there was significant variation in quality of life in this sample, suggesting that some people adjust successfully to living with GO, but for others the impact is extreme. Contrary to conventional medical perspectives, this variation was predominantly accounted for by intervening cognitive processes, rather than objective measures. There was, however, evidence that older age and asymmetrical disease were associated with poorer vision-related quality of life. The high proportion of patients with potentially diagnosable clinical depression and anxiety should be of concern to clinicians, and it highlights the need for additional psychosocial support.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge those who funded the research (City University London and Moorfields Eye Hospital Special Trustees). The authors also thank colleagues at Moorfields Eye Hospital who assisted with recruitment and data collection for the study. DGE and GER received partial funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology at Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bahn RS, Heufelder AE. Pathogenesis of Graves' ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1468–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson AJ.Clinical manifestations. In: Wiersinga WM, Kahaly GJ (eds). Graves' Orbitopathy: A Multidisciplinary Approach — Questions and Answers Karger: Basel, Switzerland; 20101–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AL, Harder I. The impact of bodily change on social behaviour in patients with Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25 (2:341–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahaly GJ, Hardt J, Petrak F, Egle UT. Psychosocial factors in subjects with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2002;12 (3:237–239. doi: 10.1089/105072502753600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Lim HT, Lee SJ, Lee SY, Yoon JS. Assessing Graves' ophthalmopathy-specific quality of life in Korean patients. Eye. 2012;26 (4:544–551. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponto KA, Hommel G, Pitz S, Elflein H, Pfeiffer N, Kahaly GJ. Quality of life in a German Graves orbitopathy population. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152 (3:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JJ, Sullivan TJ, Mortimer RH, Wagenaar M, Perry-Keene DA. Assessing quality of life in Australian patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:75–78. doi: 10.1136/bjo.88.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerding MN, Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Koornneef L, Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM. Quality of life in patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy is markedly decreased: measurement by the medical outcomes study instrument. Thyroid. 1997;7 (6:885–889. doi: 10.1089/thy.1997.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulig G, Andrysiak-Mamos E, Sowinska-Przepiera E, Kulig J, Karakiewicz B, Brodowski J, et al. Quality of life assessment in patients with Graves' disease and progressive infiltrative ophthalmopathy during combined treatment with methylprednisolone and orbital radiotherapy. Endokrynol Pol. 2009;60 (3:158–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey N, Clarke A, White P, Wyn-Williams M, Garlick W. Altered body image: appearance-related concerns of people with visible disfigurement. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48 (5:443–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Thompson AR, Jenkinson E, Rumsey N, Newell R. CBT for Appearance Anxiety. John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mourits MP, Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM, Koornneef L. Clinical activity score as a guide in the management of patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. Clin Endocrinol. 1997;47:9–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2331047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Mourits MP, Gerding MN, Baldeschi L, Kalmann R, et al. Interpretation and validity of changes in scores on the Graves' ophthalmopathy quality of life questionnaire (GO-QOL) after different treatments. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;54 (3:391–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1983;9 (3:371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Buunk BP. Individual differences in social comparison: development of a scale of social comparison orientation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76 (1:129–142. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assess. 1988;52 (1:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- McBain HB, MacKenzie KA, Hancox J, Ezra DG, Adams GGW, Newman SP.Why do patients with strabismus choose to undergo realignment surgery and what are their expectations of post-surgical outcomes? Development of two questionnaires Br J Ophthalunder review.

- Carr T, Moss TP, Harris DL. The DAS24: a short form of the Derriford Appearance Scale DAS59 to measure individual responses to living with problems of appearance. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10:285–298. doi: 10.1348/135910705X27613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss TP, Rosser BA. The moderated relationship of appearance valence on appearance self-consciousness: development and testing of new measures of appearance schema components. PLoS One. 2012;7 (11:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP.The hospital anxiety and depression scale Acta Psychiatr Scand 198367361–370.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112 (1:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A.Discovering Statistics Using SPSS3rd ednSage: London, UK; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J, Henry J, Crombie C, Taylor EP. Brief report normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40 (4:429–434. doi: 10.1348/014466501163904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CR, Newell RJ. Factor structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in individuals with facial disfigurement. Psychol Health Med. 2004;9 (3:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey N, Clarke A, White P. Exploring the psychosocial concerns of outpatients with disfiguring conditions. J Wound Care. 2003;12 (7:247–252. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2003.12.7.26515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James H, Jenkinson E, Harrad R, Ezra DG, Newman S. Appearance concerns in ophthalmic patients. Eye. 2011;25:1039–1044. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain H, MacKenzie KA, Au C, Hancox J, Ezra DG, Adams GG, et al. Factors associated with quality of life and mood in adults with strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98 (4:550–555. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Bonsel GJ, Heisterkamp SH, Prummel MF, Baldeschi L, et al. Facial disfigurement: Is it in the eye of the beholder? A study in patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;58 (2:192–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver EI, van Loon HCM, Stienstra R, Links TP, Keers JC, Kema IP, et al. Thyroid hormone status and health-related quality of life in the lifelines cohort study. Thyroid. 2013;23 (9:1066–1073. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]