Abstract

Background

Global longitudinal strain (GLS) has emerged as a superior method for detecting left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction compared to ejection fraction (EF) on the basis that it is less operator dependent and more reproducible. The 2-dimensional strain (2DS) method is easily measured and integrated into a standard echocardiogram. This study aimed to determine the relationship between GLS and traditional and chronic kidney disease (CKD)-related risk factors of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with CKD.

Methods

A cross sectional study of patients with moderate CKD stages 3 and 4 (n = 136). Clinical characteristics, anthropometric, biochemical data including markers of inflammation [C-reactive protein (CRP)], uremic toxins [indoxyl sulphate (IS), p-cresyl sulphate (PCS)], and arterial stiffness [pulse wave velocity (PWV)] were measured. Inducible ischemia was detected using exercise stress echocardiogram. GLS was determined from 3 standard apical views using 2-dimensional speckle tracking and EF was measured using Simpson’s rule. Associations between GLS and traditional and CKD-related risk factors were explored using multivariate models.

Results

The study population parameters included: age 59.4 ± 9.8 years, 58 % male, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 44.4 ± 10.1 ml/min/1.73 m2, GLS −18.3 ± 3.6 % and EF 65.8 % ± 7.8 %. This study demonstrated that GLS correlated with diabetes (r = 0.21, p = 0.01), history of heart failure (r = 0.20, p = 0.01), free IS (r = 0.24, p = 0.005) free PCS (r = 0.23, p = 0.007), body mass index (BMI) (r = 0.28, p < 0.001), and PWV (r = 0.24, p = 0.009). Following adjustment for demographic, baseline co-morbidities and laboratory parameters,GLS was independently associated with free IS, BMI and arterial stiffness (R2 for model = 0.30, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

In the CKD cohort, LV systolic function assessed using GLS was associated with uremic toxins, obesity and arterial stiffness.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0098-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Left ventricular function, Global longitudinal strain, Arterial stiffness, Obesity, Uremic toxins

Background

Global longitudinal strain (GLS) has emerged as an objective and more reproducible imaging modality to quantify subtle disturbances in left ventricular (LV) function [1]. GLS detects subendocardial contractility and viability which often precedes an overt impairment of LV function measured by ejection fraction (EF) [2]. It is increasingly reported to be a powerful prognostic tool over other measures of systolic function in various clinical settings including myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy and valvular heart disease [3–5]. In parallel with these observations, GLS was shown to be a superior predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) mortality in patients with CKD [6–8].

The pathogenesis of CV disease in CKD is complex and uniquely different resulting in a progressive change in myocardial composition and function [9]. Traditional ‘Framingham’ risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity and hypercholesterolemia are highly prevalent in patients with CKD [10] and remain an important component of patient management; however, they do not completely account for the accelerated CV risk in CKD. Renal-specific disturbances known as ‘non traditional risk factors’, including vascular calcification, abnormal bone mineral metabolism (BMM), anemia, hemodynamic overload, inflammation and uremic toxins are putative contributors to cardiac remodeling [11–14]. Similar hemodynamic and metabolic changes also predisposes to arterial stiffening [15]. Whilst arterial and cardiac remodeling can occur in parallel in CKD, arterial stiffness may lead to poor ventricular compliance and hemodynamic decompensation [16, 17].

Early evidence suggests that GLS may have a role in detecting uremic related cardiac remodeling. Kramann et al. reported that strain parameters not only detected LV contractile abnormalities but also correlated with the severity of interstitial myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy in rat models with uremic cardiomyopathy [8]. There is, however, a lack of information on the association of GLS with CV risk factors in the CKD cohort. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to characterize the association of GLS with traditional and CKD-related risk factors. The current study hypothesized that GLS will be associated with traditional and CKD-related CV risk factors in patients with CKD stage 3 and 4.

Methods

Study design

Patients aged 18 or over with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, attending the outpatient department of Princess Alexandra Hospital Renal Unit (Brisbane, Australia), were invited to participate. These patients were recruited as part of the open-label randomized controlled trial Longitudinal Assessment of Numerous Discrete Modifications of Atherosclerotic Risk factors in Kidney disease (LANDMARK) 3 study, powered for vascular structure and function end-points. The current study included 136 patients who completed the baseline visit and had cardiovascular imaging prior to the intervention of exercise and dietary modification and comprised of 84 % of the overall LANDMARK 3 study population. The study protocol was approved by the Princess Alexandra Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 2007/190) and was registered at www.anzctr.org.au (Registration Number ANZCTR12608000337370). All of the participants provided written informed consent. Clinical, biochemical and echocardiographic assessments were collected at the time of enrollment for this study.

Clinical assessment

Demographic data, including an assessment of risk factor status and history of CV disease were recorded; all prescribed and non-prescribed medications were documented. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia were defined by the use of antihypertensive or lipid-lowering therapy, respectively. Diabetes was defined by a history of this diagnosis or use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin. During the baseline visit, patients had anthropometric assessment, including height (meters) and weight (kilograms). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared. Overweight and obesity were defined using World Health Organization (WHO) Classification [18]. Previous CV event was defined as a history of documented myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, or hospital admission with acute coronary syndrome (ischemic chest pain and/or electrocardiographic [ECG] changes suggestive of ischemia with no elevation in cardiac enzymes), peripheral vascular disease including peripheral revascularization procedure or amputation due to ischemia. Blood pressure (BP) was the average of three seated measurements taken after a 5-minute rest.

Biochemical assessment

Blood for biochemical analyses was obtained from 10-hour fasting venous samples taken at the baseline visit. Serum concentrations of creatinine, albumin, urate, calcium (corrected for albumin as total calcium − [(Albumin-40)*0.02]), phosphate, parathyroid hormone (PTH), glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), hemoglobin, and lipids [total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins (LDL), high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and triglyceride] were determined using standard automated techniques. For this study, eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease- Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [19]. Uremic toxins, indoxyl sulphate (IS) and p-cresyl sulphate (PCS), total and free, were measured using the latest ultra- performance liquid chromatography and fluorescence detection method [20].

Exercise stress echocardiogram and vascular imaging

All patients underwent baseline 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography, and six standard views were acquired digitally in a stress protocol. A suitable treadmill protocol for each patient was selected based on Duke Activity Status Index. Patients exercised to maximal capacity, aiming for an age predicted heart rate of >85 %. Echocardiography was repeated immediately post exercise to look for regional abnormalities indicative of inducible ischemia. The resting echocardiographic parameters and stress echo images were analysed off-line side by side by an experienced cardiologist to determine any wall motion abnormalities provoked by stress.

GLS measurements were performed offline using commercially available dedicated automated software (EchoPAC PC, version 11, GE Healthcare, Horten, Norway). Speckles were tracked frame by-frame throughout the LV wall during the cardiac cycle and basal, mid, and apical regions of interest were created. Segments that failed to track were manually adjusted by the operator. GLS was calculated as the mean strain of all 18 segments. Previous studies have demonstrated that healthy individuals have GLS ranging from −16 to −19 % [21, 22]. A cut off at −16 % has been shown to provide important risk stratification and prognostic value [23]. Therefore, in our study we defined impaired GLS as > −16 % (a less negative value reflects a more impaired GLS). Intra- and inter-observer variation for GLS and EF were assessed by intra-class correlation co-efficient (ICC) and compared using Z-scores and Bland Altman plots as published elsewhere [24]. End-diastolic and end-systolic volumes were used to calculate EF by Simpson biplane method from the apical 4- and 2-chamber views [25]. LV mass was calculated with the formula: LV mass = 0.8 × {1.04 [([LV internal dimension + septal wall thickness + posterior wall thickness] 3 − LV internal dimension3)] + 0.6 g. Left ventricular mass was indexed to height2.7, and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as ≥51 g/m2.7 for both sexes [26]. Diastolic function was assessed using indices of LV relaxation [E/A; ratio of early (E) and late (A) diastolic transmitral flow velocities and e’; septal mitral annular peak velocities] and LV compliance (E/e’).

Aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV), expressed in meters/second (m/s), was measured using a non-invasive tonometer (SphygomoCor 2000; AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) placed over the carotid and femoral arteries at rest. Pressure signals were calibrated using brachial BP and measurements were taken of the distance of the carotid and femoral pulses from a fixed point (the suprasternal notch). The PWV was then calculated using the foot-to-foot method, gated to the cardiac cycle using a 3-lead electrocardiograph [27].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to represent characteristics at the entry of the study. The data were assessed for normality of distribution and transformed as appropriate. CRP, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, PTH, PWV, IS and PCS were log transformed. Results were expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables and median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed variables. Analysis was carried out by dividing the patients into 2 groups; one with preserved and the other with impaired GLS. Differences between the 2 groups were analysed by chi-square test for categorical data, unpaired t-test for continuous normally distributed data and Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous non-normally distributed data. A sensitivity analysis was done by dividing patients according to above and below the median values of GLS (−18.4 %) to determine whether the observed associations were still robust utilizing a different threshold. The degree of association between GLS as a continuous variable and the variables of interest was assessed using Pearson’s correlation for continuous normally distributed variables and Spearman’s correlation for categorical and non-normally distributed variables. Independent associations with GLS were assessed using stepwise multivariable regression analysis with backward elimination. To further evaluate the relationship between GLS and PWV, a series of linear regression models were constructed using GLS as a dependent variable. The first model included PWV as the sole predictor. Subsequent models were constructed by first adding traditional risk factors as predictors, then CKD-related risk factors, and finally echocardiographic parameters. Multi-colinearity was tested using variable inflation factor measurement. Data were analysed using a standard statistical software program (Stata 13; www.stata.com). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all described analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The study included 136 participants (58 % male with a mean age of 59.4 ± 9.8 years and eGFR of 44.4 ± 10.1 mL/min/1.73 m2). In this cohort, 67.6 % were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2), 42.7 % had diabetes, 94.9 % had hypertension and 39.7 % had a previous cardiac event. Participants were stratified according to preserved and impaired GLS: preserved GLS ≤ −16 % and impaired GLS > −16 % (a less negative GLS value reflects a more impaired GLS). The association between GLS and clinical characteristics based on cardiac risk factors are shown in Table 1. Participants with impaired GLS had a higher prevalence of diabetes and obesity, higher BMI, uremic toxin (free PCS) and aortic PWV. There was a trend towards an association between inducible cardiac ischemia and impaired GLS (p = 0.05). However, impaired GLS was not associated with age, gender, hypertension, previous CV events or other ‘CKD-related’ risk factors. There were also no differences between the GLS groups in the use of cardiac/anti-hypertensive medications.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 136 patients according to preserved and impaired GLS

| Preserved GLS | Impaired GLS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (GLS ≤ −16 %) | (GLS > −16 %) | ||

| N = 106 | N = 30 | ||

| Traditional risk factors | |||

| Age (years) | 58.9 ± 10.1 | 61.1 ± 8.3 | 0.3 |

| Male (%) | 58(55) | 21(70) | 0.1 |

| Current or previous smoker (%) | 70(66) | 20(67) | 0.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 38(36) | 20(67) | 0.003 |

| Fasting Glucose (mmol/L) | 6.6 ± 3.0 | 7.9 ± 3.9 | 0.04 |

| Hypertension (%) | 102(96) | 27(90) | 0.1 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 70(67) | 22(73) | 0.7 |

| -Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 0.3 |

| -LDL (mmol/L) | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Previous CV events (%) | 40(37.7) | 14(46.7) | 0.3 |

| History of HF (%) | 2(1.9) | 3(10) | 0.07 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) | 32.4 ± 6.4 | 35.8 ± 6.2 | 0.008 |

| Normal: BMI <25 | 6(5.7) | 0(0) | 0.03 |

| Overweight: 25 ≤ BMI < 30 (%) | 33(31) | 5(17) | |

| Class 1 Obesity: 30 ≤ BMI < 35 (%) | 39(37) | 9(30) | |

| Class II and III: Obesity BMI ≥ 35 (%) | 28(26) | 16(53) | |

| Blood Pressure (BP)(mmHg) | |||

| Systolic BP | 137 ± 19 | 142 ± 27 | 0.3 |

| Diastolic BP | 81 ± 11 | 82 ± 14 | 0.7 |

| Inducible Ischemia on ESE (%) | 6(6) | 5(17) | 0.05 |

| CKD related risk factors | |||

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 44.3 ± 10.1 | 44.4 ± 10.4 | 0.9 |

| Urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (g/mol) | 39(11–100) | 19(14–88) | 0.9 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.3(1.4-6.8) | 4.4(2.4-7.3) | 0.2 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.6 ± 3.6 | 37.4 ± 4.7 | 0.8 |

| Urate (mmol/L) | 0.46 ± 0.1 | 0.45 ± 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 132 ± 15 | 131 ± 16 | 0.9 |

| Corrected calcium (mmol/L) | 2.35 ± 0.1 | 2.33 ± 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.11 ± 0.17 | 1.15 ± 0.16 | 0.2 |

| PTH (pmol/L) | 8(6–13) | 12(7–16) | 0.2 |

| Free indoxyl sulphate (μmol/L) | 0.31(0.22-0.50) | 0.37(0.30-0.51) | 0.07 |

| Free P-cresyl sulphate (μmol/L) | 1.38(0.71-2.14) | 1.90(1.43-2.61) | 0.01 |

| Pulse wave velocity (m/s) | 9.0(7.3-10.7) | 10.4(9.1-13) | 0.03 |

| Medication | |||

| ACEi/ARB (%) | 88(84.6) | 26(89.7) | 0.5 |

| Βeta blockers (%) | 41(39.4) | 11(37.9) | 0.9 |

| Calcium channel blockers (%) | 49(47) | 15(51.7) | 0.7 |

| Diuretics (%) | 39(38.7) | 14(48.3) | 0.4 |

Data are mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or number (%)

GLS; global longitudinal strain, LDL; low density lipoprotein, CV; cardiovascular, HF; heart failure, CKD; chronic kidney disease, eGFR; estimated glomerular filtration rate, CRP; C-reactive protein, PTH; parathyroid hormone, ACEi; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB; angiotensin receptor blocker, ESE; exercise stress echocardiogram

Relationship between GLS and with indices of LV structure and function

Mean EF was 65.8 ± 7.8 % and mean GLS was −18.3 ± 3.6 %. Notably, 49 % of participants had LVH, primarily with concentric hypertrophy. Table 2 presents the association of GLS and echocardiographic parameters. Impaired GLS was associated with lower EF, higher left ventricular mass index (LVMI), higher left ventricular end systolic volume (LVESV), poorer left ventricular relaxation and compliance (assessed using e’ and E/e’). There was no association between GLS and left atrial (LA) volume or LV geometry.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic characteristic according to impaired and preserved GLS

| Preserved GLS | Impaired GLS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (GLS ≤ −16 %) | (GLS > −16 %) | ||

| N = 106 | N = 30 | ||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 67.6 ± 6.9 | 59.5 ± 7.5 | <0.001 |

| LVESV (ml) | 25.7 ± 11.7 | 33.2 ± 20.8 | 0.01 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 75.4 ± 23.9 | 80.1 ± 33.6 | 0.4 |

| LVESD (mm) | 2.81 ± 0.53 | 3.01 ± 0.83 | 0.1 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 4.77 ± 0.58 | 4.79 ± 0.87 | 0.9 |

| LVMI (g/m2.7) | 50.3 ± 11.7 | 56.3 ± 20.7 | 0.04 |

| RWT | 0.49 ± 0.12 | 0.51 ± 0.11 | 0.3 |

| LVH (LVMI ≥ 51 g/m2.7) | 53(50) | 16(53) | 0.8 |

| - eccentric LVH | 8(15) | 2(13) | |

| - concentric LVH | 45(85) | 14(87) | |

| LV compliance | |||

| - E/e’ | 12.3 ± 4.2 | 15.5 ± 10.9 | 0.02 |

| LV relaxation | |||

| - E/A | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.2 |

| - e’ (cm/s) | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.007 |

| LA volume (ml) | 61.5 ± 19.4 | 62.0 ± 23.2 | 0.9 |

GLS; global longitudinal strain, LVESV; left ventricular end systolic volume, LVEDV; left ventricular end diastolic volume, LVESD; left ventricular end systolic diameter, LVEDD; left ventricular end diastolic diameter, LVMI; left ventricular mass index, RWT; relative wall thickness, LVH; left ventricular hypertrophy, LA; left atrial

Traditional and CKD-related risk factors as predictors of GLS

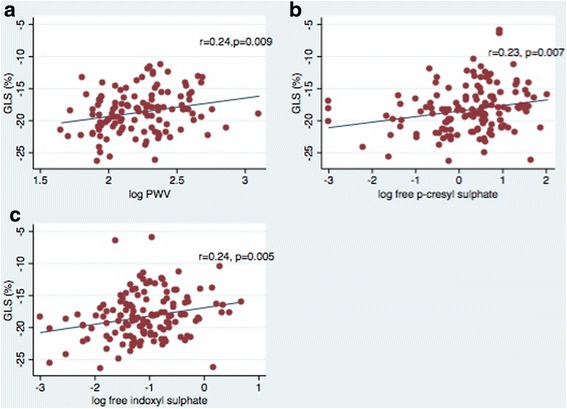

Table 3 represents the bivariate and adjusted associations between GLS and relevant CV risk factors. In bivariate analysis, GLS correlated with several important traditional risk factors including history of diabetes, heart failure (HF) and BMI. In addition, GLS also correlated with CKD-related risk factors (Fig. 1a-c) including free IS (r = 0.24, p = 0.005), free PCS (r = 0.23, p = 0.007) and PWV (r = 0.24, p = 0.009). Using stepwise linear regression adjusting for demographic, traditional and CKD-related risk factors, GLS remained independently associated with aortic PWV, free IS and BMI (R2 for model = 0.30, p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Bivariate and Multivariate association with Global Longitudinal Strain

| Variable | Bivariate Analysis | Multivariate Model (R2 = 0.30, n = 114 p < 0.0001) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | #Â coefficient (95 % CI) | p | |

| Traditional risk factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.01 | 0.9 | −0.06(−0.13,0.01) | 0.1 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.92(−0.23,2.07) | 0.1 |

| Smoking history | 0.0004 | 0.99 | ||

| Hypertension | −0.09 | 0.3 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.21 | 0.01 | ||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.06 | 0.47 | ||

| Previous CV events | 0.07 | 0.43 | ||

| HF | 0.2 | 0.01 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.1(0.02,0.2) | 0.02 |

| Peripheral systolic BP (mmHg) | 0.08 | 0.3 | −0.28(−0.07,0.01) | 0.1 |

| Peripheral diastolic BP (mmHg) | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.06(−0.002, −0.13) | 0.06 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||

| Inducible ischemia on ESE (%) | 0.14 | 0.1 | 2.05(−0.03,4.12) | 0.05 |

| CKD- related risk factors | ||||

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 0.04 | 0.6 | ||

| Urine PCR (g/mol)^ | 0.08 | 0.4 | ||

| CRP (mg/L)^ | 0.16 | 0.07 | ||

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.01 | 0.9 | ||

| Calcium (mmol/L) | −0.13 | 0.2 | −4.8(−9.6,0.06) | 0.05 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 0.09 | 0.3 | ||

| PTH (pmol/L)^ | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||

| Urate (mmol/L) | −0.1 | 0.9 | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 0.03 | 0.7 | ||

| Free ICS (μmol/L)^ | 0.24 | 0.005 | 0.9(0.07,1.68) | 0.03 |

| Free PCS (μmol/L)^ | 0.23 | 0.007 | ||

| PWV (m/s)^ | 0.24 | 0.009 | 3.29(0.53,6.03) | 0.02 |

CI; confidence interval, HF; heart failure, BMI; body mass index, BP; blood pressure; CKD; chronic kidney disease, eGFR; estimated glomerular filtration rate, ESE; exercise stress echocardiogram, PCR; protein-to-creatinine ratio, CRP; C-reactive protein, PTH; parathyroid hormone, ICS; indoxyl sulphate, PCS; p-cresyl sulphate; PWV pulse wave velocity

^log transformed

#The coefficient notes the per unit change in GLS

Fig. 1.

a-c: The association between global longitudinal strain (GLS) and a aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV), b free p-cresyl sulphate and c free indoxyl sulphate

Left ventricular –arterial association

To further distinguish the association between GLS and arterial stiffness, we compared regression and squared correlation coefficients for these parameters adjusting for traditional risk factors, CKD-related risk factors and echocardiographic parameters (Table 4). There was a statistically significant association between GLS and aortic PWV, which remained following adjustment for relevant traditional risk factors (Model 2: age, gender, diabetes, systolic BP, diastolic BP, HF, BMI, inducible ischemia) and CKD-related risk factors (Model 3: addition of eGFR, CRP, corrected calcium and uremic toxins to Model 2). The independent association between GLS and PWV also persisted following adjustment for relevant echocardiographic parameters (Model 4: addition of EF, LVMI and E/e’ to Model 3) with a decrease in the correlation coefficient.

Table 4.

Multivariate regression models for GLS: assessing the independent contribution of aortic stiffness

| Model R2 | #Â coefficient (95 % CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Unadjusted PWV | 0.06 | 2.9(0.72,5.04) | 0.009 |

| 2: 1+ traditional risk factors* | 0.26 | 3.2(0.57,5.81) | 0.01 |

| 3: 2+ CKD-related risk factors** | 0.30 | 3.34(0.54,6.15) | 0.02 |

| 4: 3+ echo parameters*** | 0.44 | 2.3(0.48,4.06) | 0.01 |

*Traditional risk factors include age, gender, diabetes, heart failure, BMI, systolic BP, diastolic BP, inducible ischemia

**CKD related risk factors include eGFR, CRP, free IS, free PCS, corrected calcium

***Echocardiogram parameters: EF, E/e’, LVMI

#The coefficient notes the per unit change in GLS, PWV; pulse wave velocity, CKD; chronic kidney disease, CI; confidence interval

Sensitivity analysis

The associations between GLS, clinical characteristics and indices of LV structure and function were repeated with a GLS cut –off at median value of −18.4 % (Additional file 1: Table S1A and S2A). Participants with lower GLS (> − 18.4 %) were still found to have higher BMI, uremic toxins (free IS and free PCS) and aortic PWV.

Discussion

This study showed in patients with established CKD stage 3 and 4, LV systolic function assessed by GLS was independently associated with aortic PWV, uremic toxins and BMI. Other traditional risk factors did not demonstrate an association with GLS. Importantly, to our knowledge this is the first study to identify the highly significant association between aortic stiffness and GLS.

There are few studies that have assessed clinical factors associated with GLS in the general population. The current study explored the associations between risk factors and GLS in CKD. In a meta-analysis, Yingchoncharoen et al. found systolic BP was an important source of variation in GLS values [28]. Dalen et al. have also reported that among healthy individuals increasing age and male gender were associated with worse GLS [29]. The current findings did not show significant associations between GLS and SBP, age or gender. There are several possible explanations for these differences including our study cohort consisted of CKD patients that have many distinctive characteristics compared to the general population. A history of hypertension was universal and BP was well controlled in this study cohort. In addition, historical values of BP readings were not available for comparison and the relatively small sample size could account for the lack of association between GLS and BP seen in this study.

CKD is a unique risk factor for cardiac remodeling; studies have demonstrated that this occurs early and is significantly worse in CKD patients compared to non-CKD [30, 31]. The structural changes are characterized by cardiomyocyte cell loss and hypertrophy, increased wall stress, dilatation or thinning of ventricular wall, scar formation and myocardial fibrosis which progresses to a maladaptive response and results in functional decompensation [32, 33]. Previous work has also demonstrated that hemodynamic and metabolic changes associated with the uremic milieu can result in endothelial dysfunction and a cascade of vascular injury in this cohort [34–36]. Endothelial dysfunction is a major pathogenic mechanism for exaggerated atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis resulting in reduced vascular and myocardial compliance, increased vascular calcification and stiffening [37]. Arterial stiffness, assessed using PWV, has been widely described and is associated with adverse CV outcome in CKD [38, 39]. It has been hypothesized that arterial stiffness may have deleterious effects on LV filling pressure resulting in greater LV wall stress and stiffness and subsequent injury to the subendocardium which is highly sensitive to wall stress and myocardial oxygen demand [40]. As GLS quantifies longitudinal contraction, especially in the subendocardial fibers, it may be a more sensitive marker of systolic dysfunction occurring prior to overt clinical disease [2, 41]. In this study, the independent association of arterial stiffness and GLS persisted following adjustment for inducible ischemia, LVMI, EF and indices of diastolic function. Whilst classically vascular stiffness is directly related to ventricular stiffness and diastolic function, our study indicates that LV systolic function can be compromised in response to ventricular- vascular stiffening in patients with moderate CKD.

The present study also demonstrated that increasing BMI was associated with worsening GLS in patients with moderate CKD. Obesity is an established risk factor for cardiomyopathy and is a growing problem in CKD. Obesity results in various metabolic and neuro-humoral alterations that can augment myocardial remodeling. Excessive free fatty acids through alteration of fatty acid β-oxidation rates has been shown to increase myocardial oxygen consumption and impair myocardial contractility [42]. Obesity is related to activation of inflammatory cytokines, especially tumour necrosis factor (TNF), that contribute to fibrotic changes of the myocardium [43]. Activation of the sympathetic and renin-aldosterone system is also widely demonstrated in obese persons and can further facilitate cardiac damage [44]. Some of these factors co-exist or are attenuated in CKD patients [45]. As a result, there are numerous maladaptive changes of the myocardium that overlap between CKD and obesity, including abnormal LV relaxation, hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis [46].

CKD- related risk factors are increasingly thought to amplify the multifaceted mechanisms of cardiovascular disease. Accordingly, this study showed a novel and independent association between the free circulating concentrations of uremic toxin IS and worsening GLS in this cohort with moderate CKD. Protein bound uremic toxins, such as IS and PCS, have been shown to accumulate with progression of CKD and are associated with adverse CV outcomes [47]. IS and PCS are both by-product of bacterial protein fermentation in the large bowel and are not efficiently cleared in the presence of kidney disease. Although these toxins are primarily protein-bound, their free fraction, which is the unbound metabolically active component, increases with deterioration of kidney function [48]. Further, these toxins have been closely linked to the synthesis of inflammatory mediators and up-regulation of inflammation among CKD patients [49, 50]. In vitro studies demonstrate exposure to free IS and PCS results in activation of the Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-kB) pathway [49] and exposure to IS in particular stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, with subsequent fibrotic, oxidative and pro-inflammatory effects on the myocardium [14].

Myocardial ischemia is a pivotal factor for cardiac remodeling in CKD and GLS was previously reported to provide prognostic information on myocardial ischemia and infarct size [51]. This study observed a trend towards an association between GLS and myocardial ischemia (p = 0.05).

This investigation is a comprehensive analysis of CV risk factors and GLS. However, a cause-effect relationship was unable to be identified due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. In this study traditional risk factors were well controlled which may have limited our ability to detect associations between these parameters and GLS. Moreover, the study was limited to subjects with an eGFR of 25 – 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and included only 30 patients with impaired GLS. Even though a large number of patient characteristics were adjusted for, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded. Larger studies are required to further explore associations with GLS in CKD.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the associations of multiple traditional and CKD-related risk factors with LV systolic function assessed using GLS in patients with CKD. LV systolic function assessed using GLS was associated with uremic toxins, obesity and arterial stiffness. Future studies are required to assess whether therapeutic strategies to modify these CV risk factors can result in improved LV function.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Lisa Ditterich and Ann King (research nurses) for their time and effort in recruitment and assistance for acquisition of data. This study was supported in part by a grant (455832) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Abbreviations

- GLS

Global longitudinal strain

- LV

Left ventricular

- EF

Ejection fraction

- 2-DS

2-dimensional strain

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- IS

Indoxyl sulphate

- PCS

P-cresyl sulphate

- PWV

Pulse wave velocity

- eGFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- BMI

Body mass index

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CV

Cardiovascular

- BMM

Bone mineral metabolism

- WHO

World Health Organization

- ECG

Electrocardiographic

- BP

Blood pressure

- LDL

Low-density lipoproteins

- HDL

High-density lipoproteins

- PTH

Parathyroid hormone

- CKD-EPI

Chronic Kidney Disease- Epidemiology Collaboration

- LVH

Left ventricular hypertrophy

- LVMI

Left ventricular mass index

- LVESV

Left ventricular end systolic volume

- HF

Heart failure

- TNF

Tumour necrosis factor

- NF-kB

Nuclear Factor-kappa B

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

Additional file

A: Clinical characteristics of 136 patients according to GLS values above and below the median. Table S2. A: Echocardiographic characteristic according values above and below the median.

Footnotes

Competing interests

CMH has received research funding from Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd and Fresenius Medical Care. She has received travel grants from Amgen Australia. NMI has received research funding from Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd, Roche Pharmaceuticals and Amgen in the form of peer-reviewed grants. She has also received travel grants from Shire Australia, Alexion Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. RK has received speaking honoraria from Shire Australia. TS has acted as a consultant to Medtronic and Novartis Pharmaceuticals. WP has received research funding from Roche Pharmaceuticals in the form of peer-reviewed grants, and travel grants from Shire Australia and Shire UK. However, the current study was not supported by those grants. The remaining authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Authors’ contributions

NMI, CMH, JC, KLC, KST: Participated in study design and helped to draft the manuscript. RK, TS, KSB, BAH, RL, WP, MR: were involved in recruitment, carried out blood testing, cardiac and vascular imaging and helped to draft the manuscript. RK and EMP: performed statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rathika Krishnasamy, Email: Rathika.Krishnasamy@health.qld.gov.au.

Carmel M. Hawley, Email: Carmel.Hawley@health.qld.gov.au

Tony Stanton, Email: t.stanton@uq.edu.au.

Elaine M. Pascoe, Email: e.pascoe@uq.edu.au

Katrina L. Campbell, Email: Katrina.Campbell@health.qld.gov.au

Megan Rossi, Email: Megan.Rossi@health.qld.gov.au.

William Petchey, Email: willpetchey@doctors.org.uk.

Ken-Soon Tan, Email: Ken-Soon.Tan@health.qld.gov.au.

Kassia S. Beetham, Email: k.weston@uq.edu.au

Jeff S. Coombes, Email: jcoombes@uq.edu.au

Rodel Leano, Email: r.leano@uq.edu.au.

Brian A. Haluska, Email: b.haluska@uq.edu.au

Nicole M. Isbel, Email: Nikky.Isbel@health.qld.gov.au

References

- 1.Kalam K, Otahal P, Marwick TH. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart. 2014;100(21):1673–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Buckberg G, Hoffman JI, Mahajan A, Saleh S, Coghlan C. Cardiac mechanics revisited: the relationship of cardiac architecture to ventricular function. Circulation. 2008;118(24):2571–2587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.754424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ersboll M, Valeur N, Mogensen UM, Andersen MJ, Moller JE, Velazquez EJ, et al. Prediction of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions from global left ventricular longitudinal strain in patients with acute myocardial infarction and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2365–2373. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito M, Okayama H, Yoshii T, Higashi H, Morioka H, Hiasa G, et al. Clinical significance of global two-dimensional strain as a surrogate parameter of myocardial fibrosis and cardiac events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13(7):617–623. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartko PE, Heinze G, Graf S, Clavel MA, Khorsand A, Bergler-Klein J, et al. Two-dimensional strain for the assessment of left ventricular function in low flow-low gradient aortic stenosis, relationship to hemodynamics, and outcome: a substudy of the multicenter TOPAS study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(2):268–276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.980201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnasamy R, Isbel NM, Hawley CM, Pascoe EM, Leano R, Haluska BA, Stanton T. The association between left ventricular global longitudinal strain, renal impairment and all-cause mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(6):1218–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Liu YW, Su CT, Sung JM, Wang SP, Su YR, Yang CS, Tsai LM, Chen JH, Tsai WC. Association of Left Ventricular Longitudinal Strain with Mortality among Stable Hemodialysis Patients with Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(9):1564–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Kramann R, Erpenbeck J, Schneider RK, Rohl AB, Hein M, Brandenburg VM, van Diepen M, Dekker F, Marx N, Floege J et al.: Speckle Tracking Echocardiography Detects Uremic Cardiomyopathy Early and Predicts Cardiovascular Mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(10):2351–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Menon V, Gul A, Sarnak MJ. Cardiovascular risk factors in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(4):1413–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Powe NR, Levey AS, Fink NE, Martin A, et al. Traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors in dialysis patients compared with the general population: the CHOICE Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(7):1918–1927. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000019641.41496.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.London GM. Cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure: pathophysiologic aspects. Semin Dial. 2003;16(2):85–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139X.2003.16023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigrist M, Bungay P, Taal MW, McIntyre CW. Vascular calcification and cardiovascular function in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(3):707–714. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, Patterson DJ, Seliger SL, Young B, et al. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2005;16(2):520–528. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lekawanvijit S, Adrahtas A, Kelly DJ, Kompa AR, Wang BH, Krum H. Does indoxyl sulfate, a uraemic toxin, have direct effects on cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes? European heart journal. 2010;31(14):1771–1779. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbons GH, Dzau VJ. The emerging concept of vascular remodeling. The New England journal of medicine. 1994;330(20):1431–1438. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405193302008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards NC, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP. Aortic distensibility and arterial-ventricular coupling in early chronic kidney disease: a pattern resembling heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart. 2008;94(8):1038–1043. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.137539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.London GM, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Blacher J, Marchais SJ, Darne B, et al. Alterations of left ventricular hypertrophy in and survival of patients receiving hemodialysis: follow-up of an interventional study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2001;12(12):2759–2767. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12122759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation (WHO technical report series). 2000, 894:i-xii, 1–253. [PubMed]

- 19.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pretorius CJ, McWhinney BC, Sipinkoski B, Johnson LA, Rossi M, Campbell KL, et al. Reference ranges and biological variation of free and total serum indoxyl- and p-cresyl sulphate measured with a rapid UPLC fluorescence detection method. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2013;419:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marwick TH, Leano RL, Brown J, Sun JP, Hoffmann R, Lysyansky P, et al. Myocardial strain measurement with 2-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography: definition of normal range. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(1):80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bussadori C, Moreo A, Di Donato M, De Chiara B, Negura D, Dall’Aglio E, et al. A new 2D-based method for myocardial velocity strain and strain rate quantification in a normal adult and paediatric population: assessment of reference values. Cardiovascular ultrasound. 2009;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ternacle J, Berry M, Alonso E, Kloeckner M, Couetil JP, Rande JL, et al. Incremental value of global longitudinal strain for predicting early outcome after cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):77–84. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanton T, Leano R, Marwick TH. Prediction of all-cause mortality from global longitudinal speckle strain: comparison with ejection fraction and wall motion scoring. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(5):356–364. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.862334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Simone G, Daniels SR, Devereux RB, Meyer RA, Roman MJ, de Divitiis O, et al. Left ventricular mass and body size in normotensive children and adults: assessment of allometric relations and impact of overweight. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20(5):1251–1260. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90385-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blacher J, Asmar R, Djane S, London GM, Safar ME. Aortic pulse wave velocity as a marker of cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1999;33(5):1111–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.33.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yingchoncharoen T, Agarwal S, Popovic ZB, Marwick TH. Normal ranges of left ventricular strain: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(2):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalen H, Thorstensen A, Aase SA, Ingul CB, Torp H, Vatten LJ, et al. Segmental and global longitudinal strain and strain rate based on echocardiography of 1266 healthy individuals: the HUNT study in Norway. European journal of echocardiography : the journal of the Working Group on Echocardiography of the European Society of Cardiology. 2010;11(2):176–183. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathew J, Katz R, St John Sutton M, Dixit S, Gerstenfeld EP, Ghio S, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiac remodelling in patients with mild heart failure: results from the REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic Left vEntricular Dysfunction (REVERSE) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(12):1420–1428. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bongartz LG, Braam B, Gaillard CA, Cramer MJ, Goldschmeding R, Verhaar MC, et al. Target organ cross talk in cardiorenal syndrome: animal models. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303(9):F1253–F1263. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00392.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber KT, Brilla CG. Pathological hypertrophy and cardiac interstitium. Fibrosis and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Circulation. 1991;83(6):1849–1865. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.83.6.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Douglas PS, Morrow R, Ioli A, Reichek N. Left ventricular shape, afterload and survival in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13(2):311–315. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen NX, O’Neill KD, Duan D, Moe SM. Phosphorus and uremic serum up-regulate osteopontin expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Int. 2002;62(5):1724–1731. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ketteler M, Rothe H, Kruger T, Biggar PH, Schlieper G. Mechanisms and treatment of extraosseous calcification in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(9):509–516. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fliser D, Wiecek A, Suleymanlar G, Ortiz A, Massy Z, Lindholm B, et al. The dysfunctional endothelium in CKD and in cardiovascular disease: mapping the origin(s) of cardiovascular problems in CKD and of kidney disease in cardiovascular conditions for a research agenda. Kidney international supplements. 2011;1(1):6–9. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2011.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moody WE, Edwards NC, Madhani M, Chue CD, Steeds RP, Ferro CJ, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease in early-stage chronic kidney disease: cause or association? Atherosclerosis. 2012;223(1):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang MC, Tsai WC, Chen JY, Huang JJ. Stepwise increase in arterial stiffness corresponding with the stages of chronic kidney disease. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2005;45(3):494–501. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blacher J, Safar ME, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, London GM. Aortic pulse wave velocity index and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63(5):1852–1860. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris DA, Gailani M, Vaz Perez A, Blaschke F, Dietz R, Haverkamp W, et al. Left atrial systolic and diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2011;24(6):651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carabello BA, Spann JF. The uses and limitations of end-systolic indexes of left ventricular function. Circulation. 1984;69(5):1058–1064. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.69.5.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):207–258. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, De Block CE. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444(7121):875–880. doi: 10.1038/nature05487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harte A, McTernan P, Chetty R, Coppack S, Katz J, Smith S, et al. Insulin-mediated upregulation of the renin angiotensin system in human subcutaneous adipocytes is reduced by rosiglitazone. Circulation. 2005;111(15):1954–1961. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161954.17870.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahba IM, Mak RH. Obesity and obesity-initiated metabolic syndrome: mechanistic links to chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(3):550–562. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04071206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sowers JR, Whaley-Connell A, Hayden MR. The Role of Overweight and Obesity in the Cardiorenal Syndrome. Cardiorenal medicine. 2011;1(1):5–12. doi: 10.1159/000322822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Liabeuf S, Meert N, Glorieux G, Temmar M, et al. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2009;4(10):1551–1558. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03980609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossi M, Campbell KL, Johnson DW, Stanton T, Vesey DA, Coombes JS, et al. Protein-bound uremic toxins, inflammation and oxidative stress: a cross-sectional study in stage 3–4 chronic kidney disease. Arch Med Res. 2014;45(4):309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun CY, Hsu HH, Wu MS. p-Cresol sulfate and indoxyl sulfate induce similar cellular inflammatory gene expressions in cultured proximal renal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(1):70–78. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glorieux G, Vanholder R, Lameire N. Uraemic retention and apoptosis: what is the balance for the inflammatory status in uraemia? Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33(8):631–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ersboll M, Valeur N, Mogensen UM, Andersen MJ, Moller JE, Hassager C, et al. Relationship between left ventricular longitudinal deformation and clinical heart failure during admission for acute myocardial infarction: a two-dimensional speckle-tracking study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25(12):1280–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]