Abstract

We describe a novel device that can be used for the transcervical transfer of embryos into pseudopregnant female mice. This nonsurgical embryo transfer (NSET) device is as efficient as standard surgical embryo transfer in the production of transgenic mice, and can also be used for the transfer of embryonic stem cell–containing chimeric blastocysts and cryopreserved embryos. In addition to the elimination of surgery, recipient females do not have to be anesthetized. The NSET device eliminates a painful surgical procedure as well as potential complications associated with anesthesia/post-operative care, reduces the technical expertise and equipment needed for surgical transfer, and represents substantial cost savings and regulatory reduction. NSET technology provides an easy and rapid alternative to surgical embryo transfer.

Keywords: transgenic mice, embryonic stem cells, mouse surgery, embryo transfer, chimeric mice, cryopreservation

Introduction

The ability to manipulate the mouse germline via gene transfer and targeted gene modification has dramatically advanced the use of mice in biomedical research (1–3). However, these strategies of genetic manipulation require the surgical transfer of embryos and lead to pain and distress for the females that serve as embryo recipients. In addition, potential problems with anesthesia and post-operative recovery, and possible post-surgical infection, require that considerable time be spent to monitor these recipient females (4,5). Furthermore, specialized surgical equipment, the need for some facilities to perform sterile procedures, and the substantial training needed for proficiency in uterine and oviduct surgery restrict the number of institutions where such procedures can be performed (6). The time and effort spent with paperwork required for compliance with regulatory guidelines is also an issue with surgical embryo transfer in rodents. To eliminate many of these problems, we have developed a device that can be used for the transcervical transfer of embryos into pseudopregnant female mice, which we call a nonsurgical embryo transfer (NSET) device.

Using a handmade device, our data indicate that NSET-mediated embryo transfer is as effective as surgical embryo transfer. Based on prototype devices, we have manufactured an NSET device that is sterile, more uniform in size, and more stable than the handmade device. NSET technology results in a dramatic reduction in the time and expertise required for the production of genetically modified mice. In addition, this technology eliminates surgery and the potential complications associated with anesthesia/post-operative care, and represents substantial cost savings and regulatory reduction.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 X C3H F1/Hsd (B6C3F1), C57BL/6N/Hsd (BL/6), and Crl:CD1(ICR) (CD-1) mice were purchased from Charles River (Frederick, MD, USA) or Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Mice were housed in positive individual ventilation (PIV) or microisolator cages with water and chow provided ad libitum and maintained on a 14 h/10 h light/dark cycle. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, following guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health.

Embryos and embryonic stem (ES) cells

Embryos were removed from pregnant female mice that had been superovulated using pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and mated to males using standard conditions as described (6). Embryos were cultured in potassium simplex optimized medium (KSOM) media (Cat. no. MR-106-D; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The R1 ES cell line was obtained from Dr. Andras Nagy (Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), cultured on mouse embryo (broblasts and used for the production of chimeric embryos by embryo aggregation (7).

NSET devices

Handmade prototype NSET devices were generated using P-2 pipet tips (Model no. 4826; Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and BD Angiocath I.V. catheters (Becton-Dickinson, Sandy, UT, USA). The P-2 pipet tip was inserted into the catheter (Supplementary Figures 1A and 1B) or the catheter tip was glued to the end of the P-2 pipet tip (Supplementary Figure 1C). The polyolefin speculum is 0.4 in (1.016 cm) in length. Initial testing was performed on euthanized female mice. Based on these results, further studies were performed on live animals; the data described in this paper were generated using handmade NSET devices. The manufactured NSET device was developed by ParaTechs Corp. (Lexington, KY, USA) based on results with prototype devices. Using specifications provided by ParaTechs Corp., the devices were produced by Martech Medical Products (Harleysville, PA, USA). The catheter tip is extruded from Teflon-FEP (DuPont, Wilmington, DE, USA) and the hub component is molded with polyethylene (a prototype is shown in Figure 1). The length of the tip and hub are 1.025 in (2.60 cm) and 0.625 in (1.588 cm), respectively. The outside and inside diameters of the tip are 0.03 in (0.076 cm) and 0.02 in (0.051 cm), respectively, and the tip is tapered at the end. The speculum is extruded from polyethylene and is 0.4 in (1.016 cm) long with outside and inside diameters of 0.162 in (0.411 cm) and 0.140 in (0.356 cm), respectively. The single-use NSET device and speculum are packaged in a clean room in a Tyvek (DuPont) pouch, followed by ethylene oxide sterilization, and are commercially available from ParaTechs Corp. (Cat. no. 859–218–6541). Details about embryo transfer using NSET technology can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1. Manufactured NSET device.

The tip is made from FEP and the hub is molded from polyethylene. The hub is designed to fit securely on the end of a P-2 Pipetman. The tip is tapered to facilitate passage through the cervix, and the length of the device is maximized to pass the cervix and not damage the uterine wall.

Results and discussion

Several papers described methods for the transcervical transfer of embryos into pseudopregnant female mice a number of years ago; these earlier methods generally used rigid (i.e., glass) tubes (8–11). We initially attempted similar approaches as a means of performing nonsurgical embryo transfer. Problems we encountered with similar glass tubes included volume control, locating and damaging the cervix, and inserting the device to a consistent depth without puncturing the uterus. Reasoning that flexible tubing would be more amenable to embryo transfer, we developed several prototype needles from catheters attached to a 2-μL pipet tip, which could then be used with a P-2 Pipetman pipet (Gilson, Middleton, WI, USA) to allow for the transcervical transfer of controlled volumes (Supplementary Figure 1). Experiments performed on euthanized female CD-1 female mice indicated that the 24-gauge, 3/4-in catheter (Becton Dickinson) (Supplementary Figure 1B) was best at penetrating the cervix without damaging the uterus.

To test whether the embryos transferred using the NSET device developed to term, a series of experiments were performed. Fertilized eggs were obtained from the mating of B6C3F1 mice and incubated at 37°C in KSOM media in the presence of 5% CO2 prior to NSET transfer into pseudopregnant CD-1 females, 2.5 days post coitus (dpc) with vasectomized males. Initially, embryonic day 0.5 (e0.5) B6C3F1 embryos were allowed to develop in vitro to the blastocyst stage (e3.5) before NSET-mediated transcervical transfer into 2.5 dpc females. Roughly 95% of the embryos developed to blastocysts when cultured in vitro. Twenty embryos were transferred to each of six pseudopregnant CD-1 females, and five of these had pups (83%). A total of 40 pups were born, which represents 33% of the transferred blastocysts. We also transferred embryos that had developed from e0.5 to the morula stage (e2.5) in vitro. When transferred to pseudopregnant 2.5 dpc females, ~15% (29 of 200) of these morula-stage embryos developed to term. When we transferred two-cell embryos that had developed overnight (24 h), <1% (1/166) developed to term, as expected, since other studies suggested that these embryos would not survive when transplanted to the uterus (11). Based on these results, all future studies were performed with e3.5 embryos transferred to 2.5 dpc pseudopregnant females.

The transcervical transfer itself is quite straightforward (Figure 2; see Supplementary Materials for a detailed protocol). Embryos are collected and transferred to a media drop (15 μL) placed in a plastic Petri dish [BD Falcon (Cat. no. 351029; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) or similar]. The NSET device, attached to a P-2 Pipetman, is then used to draw 1.8 μL of media containing the embryos (which can be readily visualized using a dissecting microscope). A speculum is inserted into the vagina and positioned around the cervix. The catheter is then inserted into the speculum and through the cervix. At this stage, the media containing the embryos is ejected from the catheter into one of the uterine horns. The entire procedure takes several seconds. The recipient pseudopregnant females are not anesthetized and exhibit no apparent discomfort. The procedure requires no special equipment and little training, and can be performed in a laminar flow hood if necessary. Getting through the cervix requires some practice, but does not require the level of expertise or equipment that is needed for surgical transfer techniques. Importantly, recipient females are not subjected to the stress and pain of surgery, anesthesia is not required, and post-operative complications such as infection are not a concern. The NSET device randomly enters one of the two uterine horns, since transferred embryos always develop in a single uterine horn. A video of this procedure, demonstrating its ease and speed, can be found online at http://www.uky.edu/~magree00/MousePipet.avi.

Figure 2. Transcervical transfer of embryos in unanesthetized pseudopregnant female mice.

The NSET device (shown in Supplementary Figure 1B) is inserted into the speculum and through the cervix, and the media containing embryos is ejected into one of the uterine horns. The entire process takes several seconds.

In order to develop the NSET technique as a potential replacement for embryo transfer surgery, we optimized several parameters and compared the success rate of NSET to standard surgical procedures. To optimize the number of pups born relative to the number of embryos transferred, we removed one-cell embryos from pregnant mice and allowed them to incubate for three days in KSOM media. The resulting blastocysts were transferred to 2.5 dpc pseudopregnant females. The data indicate the transfer of 12 or 24 blastocysts results in smaller litter sizes than the transfer of 16 or 20 blastocysts. Transfer of 16 or 20 blastocysts resulted in average litters of ~7 live pups in either case, although the percentage of live pups was higher with 16 blastocysts (28.3% versus 20.7%). Based on the percentage of live pups and the litter size, 20 blastocysts were transferred in subsequent experiments. In comparison, 27.3% of embryos became live pups when performing standard surgical transfer of embryos. We also evaluated embryo transfer success as a function of the weight and age of the recipient CD-1 females. We had optimal success with recipient females that weighed ≥26 g and were ≥60 days old.

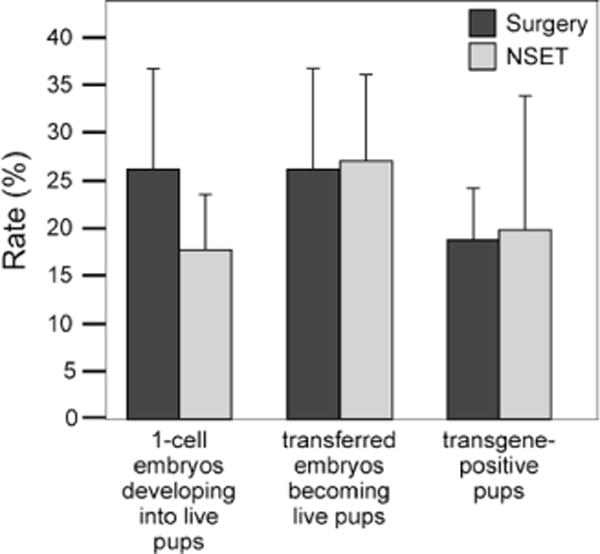

Using these optimized parameters, we then tested whether NSET could be used for producing transgenic mice by DNA microinjection. We directly compared the surgical and nonsurgical transfer of embryos that had been injected with five different transgenes that were purified using cesium chloride (CsCl, Cat. no. C-3032; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) ultracentrifugation or Qiagen kits (QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit, Cat. no. 28706; Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). For each DNA, injections were performed in one-cell B6C3F1 embryos, which were then split into two groups. The first group of embryos was surgically transferred to the oviducts of 0.5 dpc recipient females on the day of injection; 30 embryos were transferred per mouse (into one oviduct, which was our standard procedure). The second group of embryos was incubated to the blastocyst stage (e3.5) before nonsurgical transfer to 2.5 dpc recipient females (20 embryos were transferred per mouse). This data indicates that the surgical and nonsurgical procedures are roughly equivalent with regard to generating transgenic offspring (Figure 3). Of the surgically transferred embryos, 25% became live pups. Of these, the number of pups that were transgenic ranged 13–25%, with an overall rate of ~19%. These numbers are consistent with the historical success rate of our transgenic facility (data not shown). While 25% of the embryos transferred using NSET became live pups, this represented 17% of the one-cell embryos. This means that ~1/3 of the injected embryos did not survive the in vitro culturing prior to NSET transfer. However, we did find that 20% of the pups born using NSET were transgenic, indicating no substantial difference in the success of generating transgenic founder mice between surgical and NSET-mediated embryo transfer.

Figure 3. NSET versus surgical embryo transfer for the production of transgenic founder mice.

Fertilized eggs (e0.5) were removed from B6C3F1 females and injected with DNA. Embryos were either surgically transferred or incubated to the blastocyst stage (e3.5) at 37°C in KSOM media in the presence of 5% CO2 prior to NSET-mediated transfer into pseudopregnant 2.5 dpc CD1 mice. Five different transgenes were purified at different times using Qiagen kits (DNAs #1, #4, and #5) or by CsCl ultracentrifugation (DNAs #2 and #3).

We also determined whether NSET technology could be used to generate chimeric mice from embryonic stem (ES) cell–containing embryos. Chimeric aggregates were generated using the techniques described by Nagy and colleagues (6) using morulae from C57Bl/6 or B6C3F1 mice. These were transferred using NSET to nine recipient CD-1 pseudopregnant females in four separate experiments. Pups were born to six recipients, and the percentage that developed to term in five of these was quite reasonable (50–65%). Chimerism of the pups was evident based on coat color variegation (C57Bl/6 and B6C3F1 mice are black and agouti, respectively, whereas CD-1 are albino). Based on these results, we tested whether ES cell–containing chimeric mice could be generated using the NSET device. Using the R1 ES cells in which the enhancer region of the α-fetoprotein gene had been deleted using standard technology, we obtained chimeric mice, as judged by coat color. We were able to obtain germline transmission of the enhancer-deleted allele from one of the ES cell–derived chimeric males (L. Jin. L. Long, M.A.G. and B.T.S., unpublished data). Furthermore, cryopreserved embryos have been successfully transferred using the NSET device (data not shown).

Based on the results with our handmade NSET devices, we have manufactured NSET devices under current good manufacturing practices (cGMP) guidelines, with the catheter tip extruded from Teflon-FEP (DuPont) and the hub component molded using polyethylene (Figure 1). The speculums are extruded from polyethylene. Components are packaged under clean room conditions and sterilized. The manufactured NSET devices are sterile, more uniform in size, and more stable than the handmade devices. The manufactured NSET device has been tested in several experiments to generate transgenic mice and our preliminary data indicates that this works as well as the handmade devices (data not shown).

In summary, we have shown that NSET-mediated embryo transfer is equally efficient to standard oviduct transfer for the production of transgenic mice via microinjection. We have also successfully used this technology to transfer ES cell–containing blastocysts and cryopreserved embryos. One potential drawback with nonsurgical embryo transfer is that the status of the ovaries and uteri cannot be evaluated for inflammation, so embryos may occasionally be transferred into females where embryo development is unlikely to occur. NSET technology removes the pain and distress associated with the surgical transfer of embryos; eliminates the need for anesthesia, surgery, and post-operative recovery (and their potential complications, such as infections); and reduces the time required to monitor animals following surgery. The elimination of a surgical procedure represents a substantial refinement in embryo transfer [one of the three ‘Rs’ of animal research (reduction, refinement, and replacement) with the stated goal of improving humane treatment of experimental animals (12)]. NSET technology represents a substantial savings in time and eliminates the need for sterilization of specialized surgical equipment. Finally, NSET technology is substantially easier than uterine and oviduct surgery, thus requiring less training, and should facilitate efforts to manage and transport lines by embryo and sperm cryopreservation (13–16). This reduction in the level of expertise and specialized facilities required for surgical transfer could allow a greater number of institutions to participate in work involving genetically modified mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a PHS grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant no. R21 RR19693). We thank Bruce Webb and Martha Peterson for critically reviewing the manuscript and for their helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Authors B.T.S. and M.A.G. are listed as co-inventors of the patent for the NSET device (Patent no. 12/454.805). S.B. is employed by ParaTechs Corp., which manufactures and distributes the NSET device. This paper is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy.

Supplementary material for this article is available at www.BioTechniques.com/article/113257.

References

- 1.Bockamp E, Maringer M, Spangenberg C, Fees S, Fraser S, Eshkind L, Oesch F, Zabel B. Of mice and models: improved animal models for biomedical research. Physiol Genomics. 2002;11:115–132. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00067.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capecchi MR. Gene targeting in mice: functional analysis of the Mamm. Genome for the twenty-first century. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:507–512. doi: 10.1038/nrg1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon JW, Scangos GA, Plotkin DJ, Barbosa JA, Ruddle FH. Genetic transformation of mouse embryos by microinjection of purified DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7380–7384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson CA, Flecknell PA. Anaesthesia and post-operative analgesia following experimental surgery in laboratory rodents: are we making progress? Altern Lab Anim. 2005;33:119–127. doi: 10.1177/026119290503300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stokes EL, Flecknell PA, Richardson CA. Reported analgesic and anaesthetic administration to rodents undergoing experimental surgical procedures. Lab Anim. 2009;43:149–154. doi: 10.1258/la.2008.008020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagy A, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer R. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. CSH Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beatty RA. Transplantation of mouse eggs. Nature. 1951;168:995. doi: 10.1038/168995a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsk L, Larsson KS. A simple method for nonsurgical blastocyst transfer in mice. J Reprod Fertil. 1974;37:393–398. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0370393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moler TL, Donahue SE, Anderson GB. A simple technique for nonsurgical embryo transfer in mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1979;29:353–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarkowski AK. Experimental studies on regulation in the development of isolated blastomeres of mouse eggs. Acta Theriol. 1959;3:191–267. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zurlo J, Urdacille D, Goldberg AM. The three Rs: the way forward. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104:878–880. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krueger KL, Fujiwara Y. The use of buprenorphine as an analgesic after rodent embryo transfer. Lab Anim (NY) 2008;37:87–90. doi: 10.1038/laban0208-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahabir E, Bauer B, Schmidt J. Rodent and germplasm trafficking: risks of microbial contamination in a high-tech biomedical world. ILAR journal / National Research Council. Inst Lab Anim Res J. 2008;49:347–355. doi: 10.1093/ilar.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostermeier GC, Wiles MV, Farley JS, Taft RA. Conserving, distributing and managing genetically modified mouse lines by sperm cryopreservation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw JM, Nakagata N. Cryopreservation of transgenic mouse lines. Methods Mol Biol. 2002;180:207–228. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-178-7:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.