Abstract

Objective

Prostate cancer affects couples’ sexual intimacy, but men rarely use recommended pro-erectile aids. Our mixed methods study aimed to identify couples’ pre-prostatectomy barriers to sexual recovery.

Methods

Interviews about anticipated sexual recovery were paired with surveys: the Dyadic Assessment Scale, Protective Buffering Scale, Expanded Prostate Index Composite, Sexual Experience Questionnaire (men), Female Sexual Function Index. Barriers were derived using Grounded Theory. Quantitative data triangulated qualitative findings.

Results

Heterosexual couples (28) participated. Men were 62, partners 58 years old on average. Pre-existing and diagnosis-related barriers included aging-related sexual dysfunction, inadequate sexual problemsolving skills, stressors, worry, avoidance of planning for sexual recovery, dislike of ‘assisted’ sex. Participants endorsed moderate/high marital satisfaction (Mean DAS: men=110.0, SD ±11.4, partners=114.1, SD±12.1) and communication (Mean PBS: men=24.5.2, SD±6.1, partners=25.1, SD±6.2). Men reported mild ED and incontinence (Mean EPIC: 76.6, SD±.21.5; 88.4, SD±18.2, respectively). Men’s couple sexual satisfaction was lowest (Mean SEX-Q: 60.1, SD±26.9). Mean Total FSFI was low (21.6, SD±7.8).

Conclusions

Heterosexual couples face prostatectomy-related sexual side-effects having experienced developmental sexual losses. Couples use avoidant strategies to defend against worry about cancer and anticipated prostatectomy-related sexual changes. These barriers are modifiable if couples can learn to cope with sexual losses and accept sexual rehabilitation strategies.

Introduction

Although nearly all men treated surgically for early-stage prostate cancer can enjoy long term survival (Siegel et al., 2012), the sexual treatment side-effects persist (Benson, Serefoglu, & Hellstrom, 2012). Patients’ and their partners’ distress about men’s erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy (RP) has been well documented (Couper, Bloch, Love, Duchesne, et al., 2006; Couper, Bloch, Love, Macvean, et al., 2006; Garos, Kluck, & Aronoff, 2007; Hedestig, Sandman, Tomic, & Widmark, 2005; Katz, 2007). The sexual distress experienced by couples goes beyond the physiological loss of the man’s penile erections. Sexuality also includes the psychological and social dimensions (Bober & Varela, 2012; Tierney, 2008). Without acknowledging, measuring and addressing these interdependent factors, improving sexual health outcomes among men treated with RP will remain an elusive goal.

Couples facing a prostate cancer diagnosis may have already experienced age related sexual losses, including the man’s erectile dysfunction (Walz et al., 2008) and the female partners’ menopause with loss of libido and dyspareunia (Lindau et al., 2007). The impact of female sexual function on men’s sexual function after prostatectomy has been noted (Moskovic et al., 2010), but the role of menopause in couples’ sexual recovery after prostatectomy has not been studied in depth. Data on couples’ difficulties coping with sexual concerns after cancer treatment suggest that improvements in sexual health outcomes following RP require a focus on the couple, not just the patient (Sanders, Pedro, Bantum, & Galbraith, 2006; Scott & Kayser, 2009; Wootten et al., 2007).

Despite distress about erectile dysfunction, most patients never try aids to erections or discontinue their use soon after surgery (Miller et al., 2006) and partners may not encourage help-seeking (Neese, Schover, Klein, Zippe, & Kupelian, 2003). The reasons for this are not well understood, but resisting help for sexual problems poses a barrier to resumption of sexual intimacy. Another potential barrier has been described - men’s overly optimistic expectations of erection recovery (Symon et al., 2006; Wittmann et al., 2011). This list is unlikely to be exhaustive. It fueled our interest in discovering barriers to couples’ sexual recovery.

Current study

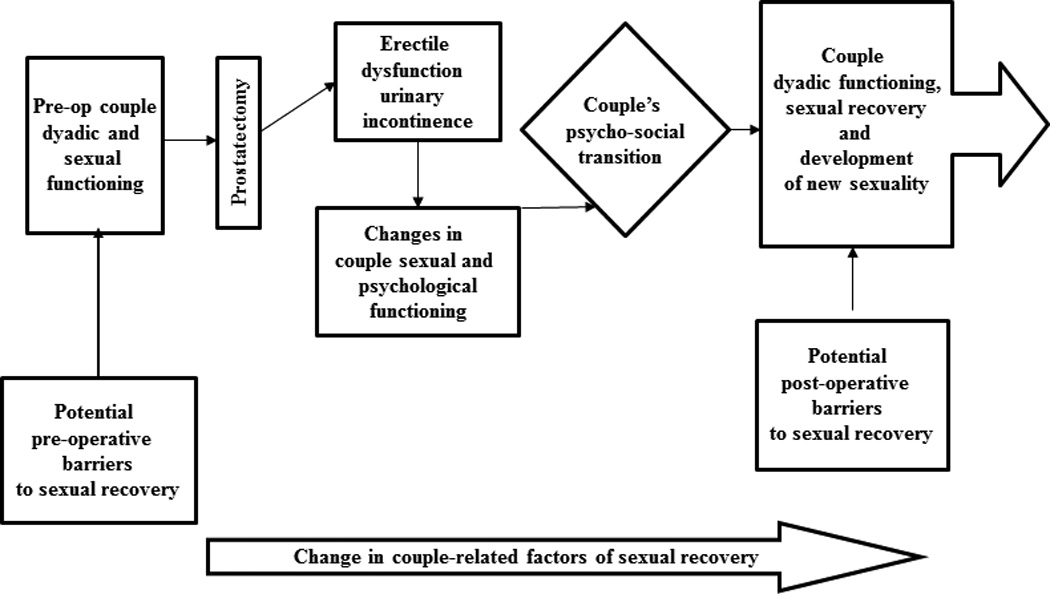

We developed a couple-centered conceptual model of sexual recovery, grounded in the literature on loss and grief and built on empirical studies of sexual losses and intimacy recovery among female cancer survivors (Manne & Badr, 2008; Parkes, 1971; Scott & Kayser, 2009; Wilmoth, 2001). In this model, the couple jointly absorbs the assault of cancer. The diagnosis of prostate cancer and treatment with its sequelae represent a life-altering psycho-social transition which, by definition, involves losses that must be grieved and mourned in order to be overcome (Wittmann, Foley, & Balon, 2011). Following this psycho-social transition, the couple moves as a unit toward sexual recovery and new sexuality which includes the use rehabilitative strategies (medical and psychosocial) unless barriers hinder the process (Figure 1). We examined pre-existing potential barriers that couples bring to the surgery for prostate cancer and to the recovery of sexual intimacy afterwards.

Figure 1.

%lodel of Couples’ Sexual Recovery after Radical Prostatectomy

Method

Design

A mixed method design was used for this study. Quantitative and qualitative data were obtained from patients and their partners prior to surgery to discover barriers that couples may bring to the post-prostatectomy sexual recovery.

Participants

Men diagnosed with prostate cancer who chose surgery in a mid-western academic cancer center were approached via a telephone call before surgery to participate in the study. The goal was to recruit 25 couples in order to reach qualitative theoretical data saturation (Guest G, 2006). Inclusion criteria for patients were: spoke English, not cognitively impaired, willing to sign informed consent, with a partner willing to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria for partners were: partnered with a man diagnosed with prostate cancer opting for surgery, spoke English, not cognitively impaired, and willing to sign informed consent. One hundred and eight couples were eligible; 28 couples participated in the study (26% response rate). Of those who did not participate, 31 did not return researchers’ calls. Others declined participation because the partner was not interested (10), patient not interested (8), distance from medical center (9), no time (5), choice of radiation treatment (2) and other reasons (15).

Procedure

Recruited couples met with one of the investigators (DW), a PhD prepared social worker and a certified sex therapist, to collect survey data and conduct the research interview at the cancer center. After signing informed consent approved by the cancer center’s Institutional Review Board, participants filled out questionnaires individually. Next, a couple-focused interview was followed by brief interviews with patients and partners separately. Afterwards, couples were debriefed regarding their comfort with the session. The interviews were recorded digitally, uploaded on a computer and transcribed. The interviewer recorded impressions of the couple and the interview in memos after each session.

Measurement

Validated measures were used to assess individuals’ sexual function, dyadic satisfaction, and couple communication prior to surgery. Qualitative semi-structured interviews examined couples’ anticipation of post-operative sexual recovery.

Quantitative Assessments

Demographic information was collected from all participants and patients’ clinical data were obtained from a prostate cancer database in our institution.

Couple adjustment

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS)

(Sharpley, 2004) was used to measure the quality of couples’ dyadic relationship. The DAS is a 32-item Likert scale with four domains: consensus, affect, satisfaction and cohesion. A higher score indicates better dyadic adjustment. The total score has an established reliability and validity (Sharpley, 2004). This study’s reliability was Cronbach α = 0.87.

Couple communication

The Protective Buffering Scale (PBS)

(Manne et al., 2004), a 10-item Likert scale was used to assess couples’ tendency to avoid discussing upsetting topics as they relate to cancer. A higher score means more avoidance of such discussions. The scale is reliable and has been validated with cancer patients. The Cronbach reliability in this study was α = 0.76.

Male sexual function

The Expanded Prostate Index Composite - Short Form (EPIC-SF)

(Wei, Dunn, Litwin, Sandler, & Sanda, 2000) assesses side-effects of prostate cancer treatment on a Likert Scale. It comprises five domains: urinary incontinence, urinary irritability, hormonal, bowel, and sexual function. Only the domains affected by RP, sexual function (S) and urinary incontinence (UIN), are reported. The sexual function domains assess desire, arousal, erection quality, orgasm and satisfaction. Higher scores indicate higher function. It has been validated and is reliable. In this study the Cronbach reliability for sexual function was α = 0.90, for urinary incontinence α = 0.90.

Male sexual satisfaction

The Sexual Experience Questionnaire (SEX-Q)

(Mulhall et al., 2008) measures men’s sexual satisfaction on three subscales: quality of erection, one’s own sexuality and sex with a partner. Participants endorse statements on a Likert scale. Higher scores indicate a higher level of satisfaction. It has established validity and reliability. The Cronbach reliability in this study was α = 0.90.

Female sexual function

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)

(Rosen et al., 2000) was used to measure women’s sexual function. Women respond to statements on a Likert scale. Six domains are assessed: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain. Higher scores indicate higher level of sexual function. A total score sums the domain scores. The scale has been validated and is reliable. Total score Cronbach reliability in this study was α = 0.96.

Qualitative Interviews

Interview guides were developed based on the review of the literature, the clinical experience of the investigators and feedback from a qualitative research expert. Some examples of questions that were presented to couples were: “As you are getting ready for surgery, can you describe your thoughts about it and any concerns?” “How do you think your experience of side-effects associated with erectile functioning … … will affect you as a couple?” “How do you think you and your partner will cope emotionally with the sexual changes?” … “Can you think of anything that could get in the way of your recovering your sexual relationship?”

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis plan

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample, men’s clinical characteristics and mean scores on the survey measures. Clinical data from 45 of approached non-participants were available for comparison. Quantitative findings contributed to the trustworthiness of the qualitative data through triangulation.

Qualitative analysis plan

Modified Grounded Theory was used to analyze the qualitative data (LaRossa, 2005). An analytic team, including a co-principal investigator (DW), a PhD prepared clinical social worker, a PhD developmental psychologist (JM, PhD), an oncology social worker (MM) and two consecutive social work interns (JG, KL) met regularly to analyze the interviews. At all levels of analysis, codes, themes and categories were reached through consensus. Starting with open coding which identified meaningful word units that represented potential barriers, the team proceeded to organize the codes thematically. Further categorization summarized the data at a higher conceptual level and helped develop a narrative about couples’ experience of pre-operative barriers to sexual recovery. The interview guides were amended iteratively, based on analytic findings after each interview and the emergence of new categories in the process. Trustworthiness of the data was secured by maintaining an audit trail, post-interview memos, random checks of transcription accuracy, and the investigators’ expertise as physicians, nurses and social workers in working with this population.

Results

Sample characteristics

Twenty eight heterosexual couples completed both quantitative and qualitative portions of the study. The description of the participants is presented in Table 1. Men’s mean age was 62.2, partners’ mean age was 58.4. The couples were married for 37 years on average. Seventy one percent of the patients and 58% of the partners were educated beyond high school. The couples’ mode yearly income was $90,000 and higher, ranging from $30,000 to higher than $90,000. One patient was African American, another was Asian. One partner was African American, another was Hispanic. All other participants were white. These characteristics reflect the population treated at this cancer treatment center. The men’s clinical characteristics indicated that most had early stage prostate cancer. They were relatively healthy overall and their clinical characteristics were not significantly different from men who refused participation.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics (N-28 couples)

| Demographic Characteristic |

Men | Partners | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Mean(SD/range) | 62.2 (6.2/50–74) | 58.4 (7.4/38–70) | ||

| Length of relationship (SD) | 33.8 (13.3/4–54) | 33.7 (14.3/4–54) | ||

| Education beyond HS (%) | 20 (71) | 17 (61) | ||

| Income (Range) | 90+K (below 30 – 90+) | 90+K (below 30 – 90+) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity N (%) | ||||

| White | 26 (93) | 26 (93) | ||

| Asian | 1 (3) | 0 | ||

| Hispanic | 0 | 1 (3) | ||

| African American | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | ||

| Clinical Characteristic (men only) | Study participants | Non-participants N=44 | p value | |

| Pre-operative PSA (Range) | 7.1 (1.3 –19.3) | 6.1(1.1 – 13.0) | 0.22 | |

| Pre-operative Gleason Score | ||||

| 6 | 11 | 20 | 0.14 | |

| 7 | 13 | 23 | ||

| 8 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 9 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Clinical Stage | ||||

| T1b | 2 | 0 | 0.55 | |

| T1c | 20 | 39 | ||

| T2a | 4 | 4 | ||

| T2b | 2 | 1 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| 0 | 22 | 35 | 0.47 | |

| 1 | 2 | 6 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 0 | ||

Quantitative Assessment of Couple Variables

Table 2 describes men’s and partners’ functional scores. On the Dyadic Adjustment Scale, men’s and partners’ average scores were 111.0 and 114.1, respectively. These scores are typical of married couples, slightly higher than average scores of married couples in the DAS validations studies (Sharpley, 2004; Spanier, 1976) and subsequent studies reported in the DAS User’s Manual (Spanier, 1989, 2001). The difference between the patients’ and partners’ DAS scores was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Functional status of the study participants (N = 28 couples)

| Variable | Men | Partners | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | P value | |

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) | 111.0 | 11.4 | 82–127 | 114.1 | 12.1 | 83–127 | NS |

| Protective Buffering (PB) | 25.2 | 6.1 | 16–39 | 25.1 | 6.2 | 14–39 | NS |

| Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) | Participants | Non-participants (N = 44) | |||||

| Sexual function (S) | 76.6 | 21.5 | 32–100 | 69.3 | 26.9 | 6–100 | 0.22 |

| Urinary Incontinence (UIN) | 88.4 | 18.2 | 54 – 100 | 94.2 | 11.7 | 54–100 | 0.16 |

| Sexual Experience Questionnaire (SEX-Q) | |||||||

| Satisfaction with quality of erection | 65.3 | 22.8 | 20.8–100 | ||||

| Satisfaction with individual sexual experience | 73.2 | 15.9 | 50.0–100 | ||||

| Satisfaction with couple sexual experience | 60.1 | 26.9 | 0–100 | ||||

| Mean | SD | Range | |||||

| Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | |||||||

| Desire | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.2–5.4 | ||||

| Arousal | 3.9 | 1.8 | 0–6 | ||||

| Lubrication | 4.1 | 2.1 | 0–6 | ||||

| Orgasm | 3.9 | 2.1 | 0–6 | ||||

| Satisfaction | 4.3 | 1.4 | 1.2–6 | ||||

| Pain | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0–6 | ||||

| Total | 21.6 | 7.8 | 3.6–32 | ||||

On the Protective Buffering Scale, men’s and partners’ average total scores were 25.2, and 25.1, respectively, and were not statistically significantly different from one another. Without an established cut off point for this scale regarding openness, these couples can be considered to be moderately open (possible score range is 10 – 50).

Men’s average sexual function score on EPIC was 76.6 and placed them into the mild erectile dysfunction range (Wheat, Hedgepeth, He, Zhang, & Wood, 2009) prior to surgery. Urinary incontinence average score was 86.4 representing mild to moderate problems prior to surgery. Their functional scores were not significantly different from the non-participants. On the Sexual Satisfaction Scale, men’s average score of 65.3 in the ‘satisfaction with erection’ domain represents mild dissatisfaction. Their average score of 73.2 in the ‘satisfaction with individual sexual activity’ domain represented fairly high satisfaction. The average score on the ‘satisfaction with the couple sexual experience’ is the lowest at 60.1. Forty percent of men were using phosphodiesterase inhibitors.

On the FSFI, women’s overall average score was 21.6. The combination of very low average score for Pain with Intercourse of 1.9, meaning greater pain, and a moderate level of sexual satisfaction with a mean score of 4.3 on average is surprising and counterintuitive.

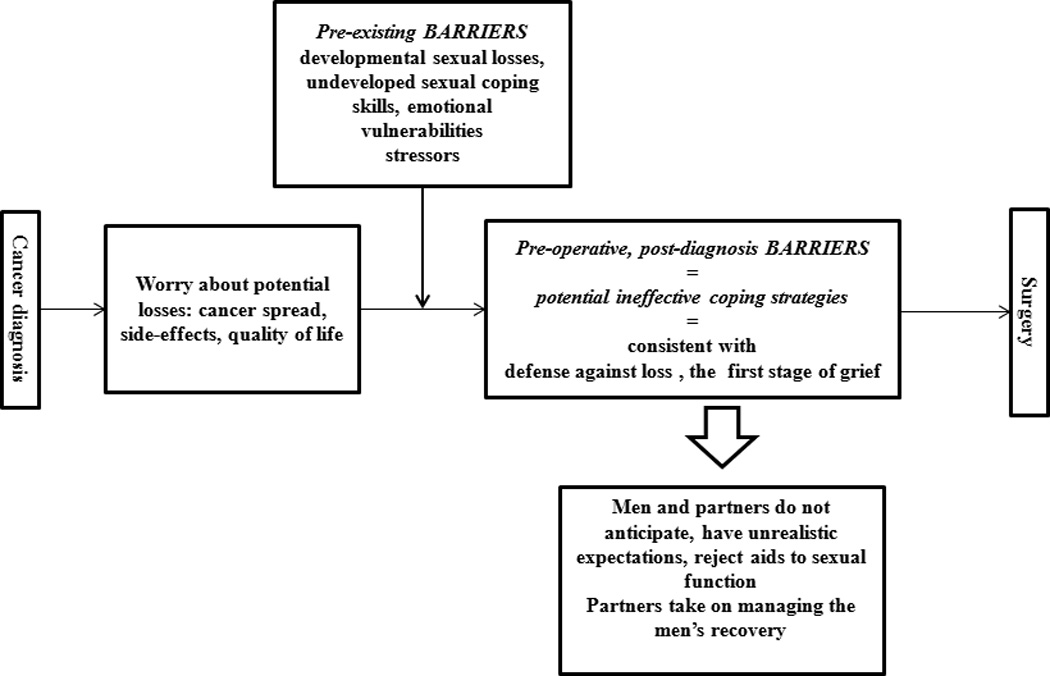

Qualitative Assessment of Pre-operative Barriers

Two major content areas emerged from the data: potential barriers related to developmental stage and potential barriers pertaining to couples’ reaction to the diagnosis (Figure 2). Within barriers related to developmental stage, three subthemes were identified: 1) Aging related sexual losses and lesser emphasis on sexuality, 2) Undeveloped skills for maintaining sexual intimacy, and 3) Stressors. Four sub-themes emerged as a reaction to diagnosis: 1) Worry, 2) Avoidant coping strategies, 3) Difficulty accepting “artificially assisted” sex, 4) Partners’ assumption of responsibility for men’s sexual recovery and men’s reliance on the partners.

Figure 2.

Potential pre-operative barriers to couples’ sexual recovery

Potential Barriers Related to Developmental Stage Prior to Surgery

Aging-related sexual losses and lesser emphasis on sexuality

Nearly two thirds of the couples reported pre-operative sexual losses. Women had lost interest in sexual activity due to menopausal changes or to comorbidities. Some women grieved the losses, others accepted them. Although some men also experienced age-related suboptimal erections, they retained sexual desire and could enhance erections by using phosphodiasterase inhibitors. Consequently, couples experienced a discrepancy in their sexual desire.

Partner: “‥ Menopause and hysterectomy ended it. I loved sex, I was passionate … “

Patient: “…my problem during sex is, I lose an erection because I'm afraid if I don't ejaculate soon I'm going to be hurting her … the next thing I know, I've lost the erection.”

Undeveloped skills for maintaining sexual intimacy

For the vast majority of couples, pre-operative sexual activity had been non-verbal. Thus couples did not have language or ease for a discussion of sexual problems. Some reported that they did not know what their partner experienced sexually. Some women continued to have sex despite discomfort and lack of pleasure.

Partner: "… I almost never…tell him I don't want to make love…and you know, sometimes it is not exactly what I'd have on my mind but it's ok."

Patient: “2025; Uh, there was lots of times … that I would have preferred to have sex but it just wasn't worth the hassle…."

Stressors

As an age cohort, these couples were facing prostate cancer just before or during retirement. Many had responsibility for aging parents or grandchildren, some had financial problems. These burdens created weariness even before sexual recovery became relevant.

Patient: “…I worry about the middle one (son) … we could sell the bar, ok, cause that's part of my retirement but I've got to worry about him, so that's another stressful thing…”

Partner: “‥ I think some of that is diminished desire but sometimes I think that’s as much environmental … working, we have two adult sons living at home with us. My mother is declining rapidly …”

Potential Barriers Pertaining to Couples’ Responses to the Diagnosis

Some barriers were emerging as couples coped with the cancer diagnosis and were anticipating surgery.

Worry

Ninety one percent of the couples endorsed worry during the pre-operative period, some worried about cancer spread, others about coping with the side-effects.

Patient: "…I'm very active physically…and you hope … that you're not debilitated for some reason… “

Partner: " ‥Oh definitely I'm worried about incontinence …"

Patient: (loss of erection)”… it’s always the bravado of being able to … satisfy your … wife, um, if I can’t ‥ it would also be psychologically (hard for) me that I’m not able to do that…“

Avoidant coping strategies

Eighty six percent of the couples deferred thinking about the side-effects of RP. However, when they did think forward, they were very optimistic.

Patient: (losing erectile function) “. ‥ no, I haven’t thought of it …, that it would be a loss I guess. I haven’t gone that far …“.

Partner: ” I guess I don’t think that’s going to happen (erectile dysfunction) and that’s why I haven’t thought about it.”

Difficulty accepting the idea of “artificially” assisted sex

Couples had difficulty seeing themselves as having unspontaneous ex and using erectile aids such medications, vacuum devices, injections, or suppositories or lubricants during sexual activity: 77% either rejected at least some methodologies.

Patient: “ ‥ My personal feeling is I don't want to have to use that stuff (vacuum erectile device)…I just think it's not human, it's not natural…”

Partner: "There was that one time when you know I was trying creams and all kinds of things…that was yucky."

Partners’ assumption of responsibility for men’s sexual recovery and men’s reliance on partners

Partners often spoke on behalf of the men and expected to have to manage men’s emotions about sexual recovery, their needs, and anticipated difficulties, such as men’s likely frustration and impatience during the recovery or their potential non-compliance with penile rehabilitation. Men acknowledged the partners’ role, sometimes as a normal expectation in their relationship.

Partner: “… I think that he’s going to feel a lot of frustration … I think I’m just going to be wanting to protect him from hurting himself …“

Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Despite sexual function discrepancy in some couples and men’s dissatisfaction with couple sexuality on the SEX-Q pre-operatively, men and partners did not speak of sexual dissatisfaction. Rather, they spoke of acceptance of their sexual difficulties and hope to address them in the context of working on the man’s erectile dysfunction after surgery.

Overall, there was a congruence/”spilling over” between men and partners in their perception of some barriers, particularly in terms of having overly optimistic expectations of sexual outcomes and in the appraisal of external stressors. However, partners’ were more aware than men of the men’s likelihood to be impatient and frustrated in the recovery period and partners had more fear about cancer not being eradicated than the men.

Discussion

Heterosexual couples in this study were in long term, stable relationships before surgery, but they had a number of pre-existing vulnerabilities: aging-related sexual losses, partners’ lower interest in sex, lack of skills for maintaining mutually satisfying sexual activity and stressors.

Both qualitative and quantitative data indicate that patient and partners had discrepant sexual function preoperatively which has potential implications for post-prostatectomy couple sexual recovery as noted by some researchers (Shindel, Quayle, Yan, Husain, & Naughton, 2005). Women endorsement of reasonably high sexual satisfaction despite significant pain with intercourse and only moderate arousal and lubrication suggests that women base post-menopausal sexual satisfaction on factors other than sexual function, e.g., emotional intimacy with the partner, as has been suggested by Basson’s model of female sexual arousal (Basson, 2002). Making love less often may be a way for couples to cope with aging related functional challenges without disconnecting sexually. However, infrequent sexual activity may be a barrier to working on sexual recovery which requires attention and focus on sexual interactions after surgery.

Men’s low satisfaction with couple sexuality, as measured by the SEX-Q, may corroborate the findings although not conclusions of an earlier study by Shindel et al. (Shindel, et al., 2005). They found that men’s sexual satisfaction was correlated with the woman’s lower sexual pain and concluded that a firmer penis may enable a more comfortable penetration. Clinical experience suggests that women’s post-menopausal thin and fragile walls are likely to be abraded thin by a firm penis; we conclude from their and our findings that a man whose partner is not in pain is simply more able to enjoy the sexual interaction. Some couples adapted to aging related sexual changes by placing lower priority on their sexual activity.

After prostate cancer diagnosis, couples worry about surgery and surgery side effects. They cope by postponing thinking about side-effects, holding overly optimistic expectations of erectile and sexual recovery, and by rejecting the idea of unspontaneous assisted sex as artificial and unnatural. Although these seemingly avoidant strategies may appear maladaptive, they are consistent with the initial reaction to loss which is disbelief, and a wish to not accept the reality of the loss. These wishes complicate grief only when they persist in the form of longing for the past at the cost of adaptation to current circumstances. In prostate cancer, this form of anticipatory grief needs to be treated with respect until a post-prostatectomy adaptation is fully understood.

Partners’ pre-operative assumption that they will have to manage the men’s recovery was an interesting finding because it squarely put partners into the role of a caregiver along with that of a sexual partner at a time when they have less desire and increased role demands. It represents an emotional complexity of involvement that may be quite challenging to manage during the post-operative phase. It also adds a dimension to Couper’s and colleagues’ finding that partners are distressed earlier than men (Couper, Bloch, Love, Duchesne, et al., 2006).

Although all couples told us that sexual recovery was important to them, they preferred not to anticipate it. From a clinical perspective, postponing thinking about it can be a way of coping with anticipated loss. Or it may represent a lack of confidence based on not having coped well with sexual losses after menopause.

Helplessness in sexual problem solving, refusal to use erectile aids and a wish to not accept potential sexual losses after prostatectomy can become barriers to couples’ sexual recovery if they persist and are not addressed as such. Couples can be taught about grief and mourning of sexual losses, and about enhancing women’s post-menopausal sexual viability. As men learn about aids to erections, women can be taught methods for enhancing lubrication and reducing pain during intercourse. Basson’s model of female (Basson, 2002) arousal, attuned to sexuality based on intention rather than spontaneity, is relevant both to men who need assistance with erections and their post-menopausal partners. It is challenging to introduce these topics and important not to expect that couples will focus on these potential barriers while they anticipate surgery. However, when quality of life issues become more salient after prostatectomy, having an alliance with providers who had foreseen these issues can normalize them and go a long way toward addressing them productively afterwards. In that sense, these potential barriers can become modifiable.

It is important to note that this study focused on perceived barriers to couples’ sexual recovery prior to having surgery. In the interviews, couples clearly evidenced strengths as they anticipated surgery as well. Their absence in this report reflects the research question rather than an overall assessment of the couples’ functioning.

The strength of this study is its reliance on couples’ voices for the understanding of the potential barriers to their sexual recovery after prostate cancer surgery. The sample size helped reach theoretical saturation and makes the findings trustworthy. The quantitative data confirmed the qualitative findings about sexual function discrepancy and women’s discomfort with sexual penetration. The limitations of the study are selection bias due to participation of couples interested in sexual recovery, a non-diverse sample, and the fact that these potential perceived barriers cannot be clearly endorsed unless the post-operative findings confirm them. The relatively high refusal rate for participation in this study may be explained by possible discomfort that middle age and older couples may have regarding discussions of sexuality. It is also likely that couples who anticipate surgery for cancer may consider sexuality with more interest after surgery.

Clinical implications

As they approach surgery for prostate cancer and its sexual side-effects, couples need education that addresses the rationale for sexual rehabilitation and emotional coping with the effect of the loss of erectile function on their sexual relationship. Information about resources for sexual recovery should be available prior to surgery. Although it may not be fully meaningful prior to treatment, the availability of such education and resources can provide a framework within which couple can work on sexual recovery afterwards.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work was funded by a grant of the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Healthcare Research (MICHR) Pilot and Collaborative Grant Program UL1RR024986 and by the University of Michigan Cancer Center

Footnotes

Disclosures: Daniela Wittmann owns $4000 worth of Pfizer stock James Montie serves on the Advisory Board of Histosonics, Inc

References

- Basson R. A model of women's sexual arousal. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2002;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/009262302317250963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson CR, Serefoglu EC, Hellstrom WJ. Sexual Dysfunction Following Radical Prostatectomy. Journal of Andrology. 2012 doi: 10.2164/jandrol.112.016790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(30):3712–3719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couper JW, Bloch S, Love A, Duchesne G, Macvean M, Kissane DW. The psychosocial impact of prostate cancer on patients and their partners. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;185(8):428–432. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couper JW, Bloch S, Love A, Macvean M, Duchesne GM, Kissane D. Psychosocial adjustment of female partners of men with prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2006;15(11):937–953. doi: 10.1002/pon.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garos S, Kluck A, Aronoff D. Prostate cancer patients and their partners: differences in satisfaction indices and psychological variables. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2007;4(5):1394–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hedestig O, Sandman PO, Tomic R, Widmark A. Living after radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer: a qualitative analysis of patient narratives. Acta Oncologica. 2005;44(7):679–686. doi: 10.1080/02841860500326000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A. Quality of life for men with prostate cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2007;30(4):302–308. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281726.87490.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRossa R. Grounded theory methods and qualitative family research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(4):837–857. [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O'Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(8):762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples' psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Ostroff J, Rini C, Fox K, Goldstein L, Grana G. The interpersonal process model of intimacy: the role of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and partner responsiveness in interactions between breast cancer patients and their partners. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(4):589–599. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DC, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Montie JE, Pimentel H, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Use of medications or devices for erectile dysfunction among long-term prostate cancer treatment survivors: potential influence of sexual motivation and/or indifference. Urology. 2006;68(1):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskovic DJ, Mohamed O, Sathyamoorthy K, Miles BJ, Link RE, Lipshultz LI, Khera M. The female factor: predicting compliance with a post-prostatectomy erectile preservation program. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(11):3659–3665. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall JP, King R, Kirby M, Hvidsten K, Symonds T, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC. Evaluating the sexual experience in men: validation of the sexual experience questionnaire. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(2):365–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese LE, Schover LR, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Finding help for sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment: a phone survey of men's and women's perspectives. Psychooncology. 2003;12(5):463–473. doi: 10.1002/pon.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes CM. Psycho-social transitions: a field for study. Social Science Medicine. 1971;5(2):101–115. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(71)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, D'Agostino R., Jr The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S, Pedro LW, Bantum EO, Galbraith ME. Couples surviving prostate cancer: Long-term intimacy needs and concerns following treatment. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2006;10(4):503–508. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JL, Kayser K. A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women's sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer Journal. 2009;15(1):48–56. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819585df. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819585df [doi]00130404-200902000-00010 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley CF, Cross DG. A psychometric evaluation of the Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2004;44:739–747. [Google Scholar]

- Shindel A, Quayle S, Yan Y, Husain A, Naughton C. Sexual dysfunction in female partners of men who have undergone radical prostatectomy correlates with sexual dysfunction of the male partner. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2005;2(6):833–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00148.x. discussion 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, Ward E. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012;62(4):220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1976;38(1):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS): User's Manual. New York, Toronto: MHS; 1989, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Symon Z, Daignault S, Symon R, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, Sandler HM. Measuring patients' expectations regarding health-related quality-of-life outcomes associated with prostate cancer surgery or radiotherapy. Urology. 2006;68(6):1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney DK. Sexuality: a quality-of-life issue for cancer survivors. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2008;24(2):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz J, Perrotte P, Suardi N, Hutterer G, Jeldres C, Benard F, Karakiewicz PI. Baseline prevalence of erectile dysfunction in a prostate cancer screening population. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(2):428–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheat JC, Hedgepeth RC, He C, Zhang L, Wood DP., Jr Clinical interpretation of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite-Short Form sexual summary score. Journal of Urology. 2009;182(6):2844–2849. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.088. doi: S0022-5347(09)02123-5 [pii]10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.088 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth MC. The aftermath of breast cancer: an altered sexual self. Cancer Nursing. 2001;24(4):278–286. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann D, Foley S, Balon R. A biopsychosocial approach to sexual recovery after prostate cancer surgery: the role of grief and mourning. Journal of Sex and Marital Theraphy. 2011;37(2):130–144. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.560538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann D, He C, Coelho M, Hollenbeck B, Montie JE, Wood DP., Jr Patient preoperative expectations of urinary, bowel, hormonal and sexual functioning do not match actual outcomes 1 year after radical prostatectomy. Journal of Urology. 2011;186(2):494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootten AC, Burney S, Foroudi F, Frydenberg M, Coleman G, Ng KT. Psychological adjustment of survivors of localised prostate cancer: investigating the role of dyadic adjustment, cognitive appraisal and coping style. Psychooncology. 2007;16(11):994–1002. doi: 10.1002/pon.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]