Abstract

The evaluation of liquefaction potential of soil due to an earthquake is an important step in geosciences. This article examines the capability of Minimax Probability Machine (MPM) for the prediction of seismic liquefaction potential of soil based on the Cone Penetration Test (CPT) data. The dataset has been taken from Chi–Chi earthquake. MPM is developed based on the use of hyperplanes. It has been adopted as a classification tool. This article uses two models (MODEL I and MODEL II). MODEL I employs Cone Resistance (qc) and Cyclic Stress Ratio (CSR) as input variables. qc and Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA) have been taken as inputs for MODEL II. The developed MPM gives 100% accuracy. The results show that the developed MPM can predict liquefaction potential of soil based on qc and PGA.

Keywords: Liquefaction, Cone Penetration Test, Minimax Probability Machine, Artificial Intelligence

Introduction

Liquefaction causes lot of damages during earthquake. So, the prediction of liquefaction potential of soil due to an earthquake is an important step for earthquake hazard mitigation. There are various techniques available for the determination of liquefaction potential of soil in the literature [1–13]. However, available methods have some limitations [14]. Researchers used Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques for the prediction of liquefaction susceptibility of soil [14–25].

This article adopts Cone Penetration Test (CPT) based Minimax Probability Machine (MPM) for the prediction of seismic liquefaction potential of soil. The datasets have been collected from Chi–Chi earthquake at Taiwan. MPP is developed by Lanckriet et al. [26]. MPM is constructed in probabilistic framework. This article uses MPM as a classification problem. It has been successfully adopted for modeling different problems in engineering [27–29]. The magnitude of earthquake was 7.6. The epicenter of earthquake was at 23.87°N and 120.75E [30]. Extensive liquefaction was observed at Yuanlin, Wufeng, and Nantou. Many CPT tests were conducted after the earthquake [30]. Two models (MODEL I and MODEL II) have been used to get best performance. MODEL I adopts Cone Resistance (qc) and Cyclic Stress Ratio (CSR) as input variables. qc and Peck Ground Acceleration (PGA) have been used as inputs of the MODEL II. The database has been collected from the work of Ku et al. [31]. In this database, liquefaction is observed in 46 sites. The remaining 88 sites are non-liquefied. The developed MPM has been applied for the global data [16]. This article gives charts for classifying liquefiable and non-liquefiable soil.

Details of MPM

In MPM, it is assumed that positive definite covariance matrices exist in each of the two classes. In MPM, the probability of misclassification of future data is minimized [26]. In MPM, following optimal hyperplane is used for separating the two classes of points.

| (1) |

In MPM, the following optimization problem is constructed [20]:

| (2) |

where α is called the worst-case accuracy.

The above optimization problem (2) is solved by Lagrangian Multiplier. So, it takes the following form.

| (3) |

The optimization problem (3) is written in the following form:

| (4) |

The above optimization problem (4) is solved by convex programming technique.

To develop the above MPM, non-liquefied sites are denoted by +1 and liquefied sites are denoted by −1. In MPM, training dataset is adopted to develop the model and a testing is employed to verify the developed MPM. Ninety-four datasets have been adopted as training datasets. The 40 remaining datasets have been employed as testing datasets.

In this article, the datasets are scaled between 0 and 1. This study adopts radial basis function (where σ is width of radial basis function) as kernel function for developing the MPM. This article employs MATLAB software for constructing MPM.

Results and discussion

The success of MPM depends on the choice of proper value of σ. This study adopts trial and error approach for the determination of the design value of σ. Training and testing performance have been determined by using the following equation.

| (5) |

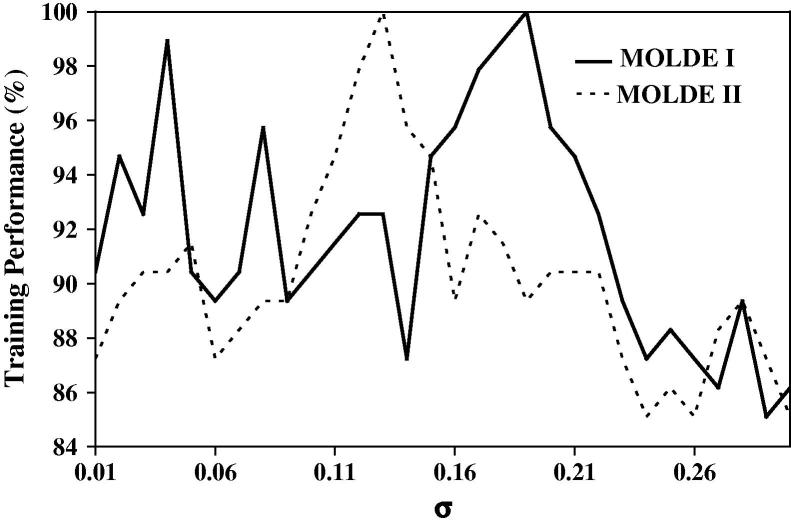

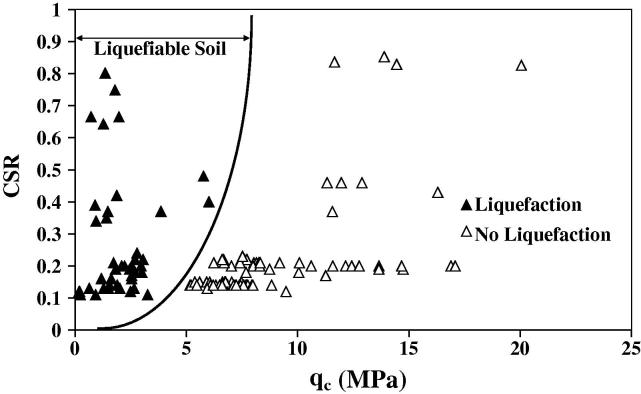

Fig. 1 shows the effect of σ on training performance (%) for MODEL I. It is observed from Fig. 1 that the developed MPM gives best training performance at σ = 0.19 for MODEL I. The developed MPM gives 100% training performance. The performance of testing dataset is also 100%. Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the performance of MPM for training and testing dataset respectively. The classification of MPM has been plotted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Effect of σ on training performance (%).

Table 1.

Performance of training dataset.

| qc (MPa) | PGA(gal) | CSR | Actual class | Predicted class |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODEL I | MODEL II | ||||

| 1.27 | 774 | 0.643 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 0.72 | 774 | 0.665 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 1.35 | 774 | 0.802 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 11.66 | 774 | 0.836 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13.89 | 774 | 0.853 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 20.05 | 774 | 0.826 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.94 | 420 | 0.34 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 1.47 | 420 | 0.37 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 11.56 | 420 | 0.37 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12.89 | 420 | 0.46 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 16.3 | 420 | 0.43 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.41 | 420 | 0.35 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 11.96 | 420 | 0.46 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.87 | 420 | 0.42 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 5.77 | 420 | 0.48 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 2.54 | 188 | 0.17 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 7.46 | 188 | 0.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.62 | 188 | 0.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.03 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.02 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.72 | 188 | 0.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.68 | 188 | 0.18 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.22 | 188 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 12.15 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.54 | 188 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 8.15 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10.08 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12.43 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.62 | 188 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 2.45 | 188 | 0.19 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 6.7 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13.65 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 17.08 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.66 | 188 | 0.18 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 8.25 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.41 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.54 | 188 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 12.77 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.18 | 188 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 2.96 | 188 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 8 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.74 | 188 | 0.19 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11.26 | 188 | 0.17 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.52 | 207 | 0.23 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.61 | 188 | 0.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.3 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.32 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 188 | 0.18 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 2.09 | 188 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 2.78 | 188 | 0.24 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 3.05 | 188 | 0.22 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 14.67 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10.61 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13.65 | 188 | 0.19 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.28 | 121 | 0.13 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 0.64 | 121 | 0.13 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 5.16 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3.26 | 121 | 0.11 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 7.4 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.04 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.47 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.54 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.64 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.59 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.85 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.68 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.21 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.18 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.91 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.38 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.99 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.38 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.41 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.73 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.49 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.47 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.92 | 121 | 0.11 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 1.5 | 121 | 0.13 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 6.05 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.76 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.49 | 121 | 0.12 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 1.89 | 121 | 0.14 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 1.54 | 121 | 0.14 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 7.43 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.61 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.12 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.08 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9.48 | 121 | 0.12 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.2 | 121 | 0.12 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 5.93 | 121 | 0.13 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.57 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.24 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.21 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.83 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 2.

Performance of testing dataset.

| qc (MPa) | PGA(gal) | CSR | Actual class | Predicted class |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODEL I | MODEL II | ||||

| 1.79 | 774 | 0.749 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 14.45 | 774 | 0.829 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11.32 | 420 | 0.46 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.01 | 420 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 0.9 | 420 | 0.39 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 8.27 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.7 | 188 | 0.18 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 6.67 | 188 | 0.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.23 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.62 | 188 | 0.18 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 16.89 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9.19 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.82 | 188 | 0.19 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 8.3 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.73 | 207 | 0.21 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 10.05 | 188 | 0.18 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.61 | 188 | 0.19 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 11.58 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.69 | 188 | 0.22 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 14.74 | 188 | 0.19 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.46 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.65 | 121 | 0.13 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 7.68 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.58 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.12 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.62 | 121 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.03 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.32 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.64 | 121 | 0.13 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 2.01 | 121 | 0.13 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 7.72 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.76 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.94 | 121 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.18 | 121 | 0.12 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 1.97 | 774 | 0.665 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 3.86 | 420 | 0.37 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 6.8 | 188 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.01 | 188 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.23 | 121 | 0.11 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 6.83 | 207 | 0.23 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Fig. 2.

Plot between CSR and qc.

For MODEL II, the effect of σ on training performance has been shown in Fig. 1. It is clear from Fig. 2 that the best training performance has been achieved at σ = 0.13. The developed MPM produces 100% training as well as testing performance. So, the developed MODEL II gives same performance as given by MODEL II. The performance of MPM for training and testing dataset has been depicted in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

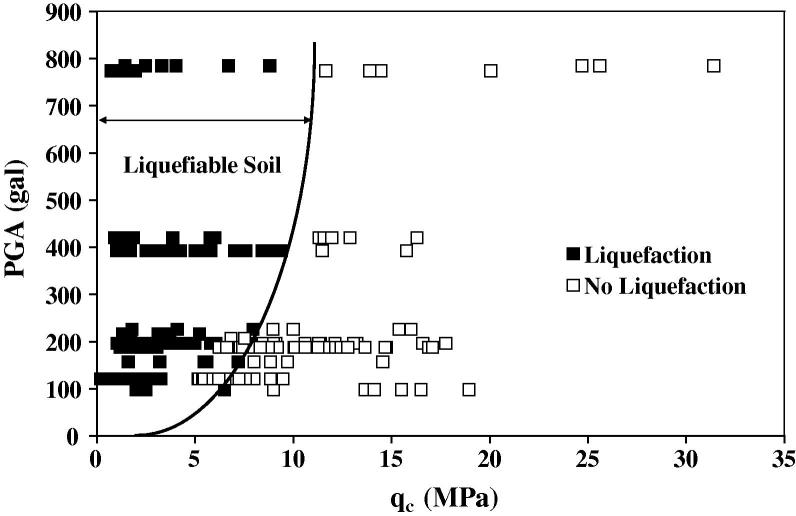

Fig. 3 plots the results of MODEL II. The generalization capability of developed MODEL II has been examined by the global datasets [16]. These global datasets consists information about liquefiable and non-liquefiable soil of five earthquakes. The developed MODEL II correctly classifies 100 datasets out of 109. Therefore, the developed MPM shows good generalization capability. Table 3 shows the performance of global data.

Fig. 3.

Plot between PGA and qc.

Table 3.

Performance of the global data [16].

| Site | qc (MPa) | PGA (g) | Actual class | Predicted class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawagishicho | 3.2 | 0.16 | −1 | 1 |

| Kawagishicho | 1.6 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 |

| Kawagishicho | 7.2 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 |

| Kawagishicho | 5.6 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 |

| Kawagishicho | 5.45 | 0.16 | −1 | 1 |

| Kawagishicho | 8.84 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 |

| Kawagishicho | 9.7 | 0.16 | −1 | −1 |

| Kawagishicho | 8 | 0.16 | 1 | 1 |

| Kawagishicho | 14.55 | 0.16 | 1 | 1 |

| Noshirocho | 10 | 0.23 | 1 | −1 |

| Noshirocho | 16 | 0.23 | 1 | 1 |

| Noshirocho | 15.38 | 0.23 | 1 | 1 |

| Noshirocho | 1.79 | 0.23 | −1 | −1 |

| Noshirocho | 4.1 | 0.23 | −1 | −1 |

| Noshirocho | 7.95 | 0.23 | −1 | −1 |

| Noshirocho | 8.97 | 0.23 | −1 | −1 |

| T-10 | 1.7 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-10 | 9.4 | 0.4 | −1 | 1 |

| T-10 | 5.7 | 0.4 | −1 | 1 |

| T-10 | 7.6 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-11 | 1.5 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-11 | 1 | 0.4 | −1 | 1 |

| T-11 | 5 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-12 | 2.5 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-12 | 2.6 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-12 | 3.2 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-12 | 5.8 | 0.4 | −1 | 1 |

| T-12 | 3.5 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-12 | 8.4 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-13 | 1.7 | 0.4 | −1 | 1 |

| T-13 | 3.5 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-13 | 4.1 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-14 | 5.5 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-14 | 9 | 0.4 | −1 | 1 |

| T-15 | 7 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-15 | 1.18 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-15 | 4.24 | 0.4 | −1 | −1 |

| T-16 | 11.47 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 |

| T-16 | 15.76 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 |

| T-17 | 11.39 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| T-17 | 12.12 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| T-17 | 17.76 | 0.2 | 1 | −1 |

| T-23 | 2.65 | 0.2 | −1 | 1 |

| T-24 | 4.4 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-24 | 3 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-25 | 9 | 0.2 | −1 | 1 |

| T-26 | 2 | 0.1 | −1 | −1 |

| T-27 | 1.1 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-28 | 15.5 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| T-28 | 6.5 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| T-29 | 9 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| T-29 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| T-29 | 16.5 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| T-30 | 13.65 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| L-1 | 8.47 | 0.2 | 1 | −1 |

| L-1 | 4.55 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| L-1 | 5.79 | 0.2 | 1 | −1 |

| L-2 | 2.48 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| L-2 | 1.57 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| L-2 | 1.45 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| L-2 | 2.15 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| L-2 | 2.6 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| L-3 | 2.73 | 0.2 | −1 | 1 |

| L-3 | 1.78 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| L-5 | 7.64 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| Heber Road | 25.6 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

| A1 | 24.7 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

| A1 | 31.4 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

| A2 | 1.43 | 0.8 | −1 | −1 |

| A2 | 2.48 | 0.8 | −1 | 1 |

| A3 | 4.03 | 0.8 | −1 | −1 |

| A3 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

| A4 | 8.8 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

| A4 | 6.7 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

| T-18 | 1.65 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-18 | 3.65 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-19 | 1.03 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-19 | 5 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-19 | 2.91 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-19 | 6.06 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-20 | 13.24 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| T-20 | 13.06 | 0.2 | 1 | −1 |

| T-20 | 16.59 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| T-21 | 10.59 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| T-21 | 9.12 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| T-21 | 11.29 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| T-22 | 1.94 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-22 | 5 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-23 | 2.24 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-30 | 14.12 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| T-30 | 18.94 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| T-31 | 3.52 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-31 | 2.73 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-32 | 3.29 | 0.2 | −1 | 1 |

| T-32 | 4.12 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-32 | 2.94 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-33 | 3 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-33 | 5.85 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-33 | 9 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-34 | 1.8 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-35 | 2.55 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-35 | 4.5 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-35 | 4.24 | 0.2 | −1 | −1 |

| T-36 | 8 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| Dimbovitza site | 5.22 | 0.22 | −1 | 1 |

| Dimbovitza site | 3.73 | 0.22 | −1 | −1 |

| Dimbovitza site | 3.11 | 0.22 | −1 | −1 |

| Dimbovitza site | 1.32 | 0.22 | −1 | −1 |

| Dimbovitza site | 5.22 | 0.22 | −1 | −1 |

Conclusions

This article successfully applied MPM for the determination of seismic liquefaction potential of soil. Two models (MODEL I and MODEL II) have been tried to get best performance. The performance of MPM for MODEL I and II is excellent. This study shows that the developed MPM can predict liquefaction potential of soil based on qc and PGA. Geotechnical engineers can use the developed charts for the determination of seismic liquefaction potential of soil. The developed MPM shows good generalization capability. MPM model can be adopted for modeling different problems in geosciences.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Seed H.B., Idriss I.M. Analysis of soil liquefaction: Niigata earthquake. J Soil Mech Found Div ASCE. 1967;93(3):83–108. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seed H.B., Idriss I.M. Simplified procedure for evaluating soil liquefaction potential. J Soil Mech Found Div ASCE. 1971;97(9):1249–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seed H.B., Idriss I.M., Arango I. Evaluation of liquefaction potential using field performance data. J Geotech Eng Div ASCE. 1983;109(3):458–482. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seed HB, Tokimatsu K, Harder LF, Chung RM. Influence of SPT procedures in soil liquefaction resistance evaluation. Rep. No. UCB/EERC-84/15, Earthquake Eng Res Ctr, California: Univ. of California, Berkeley; 1984.

- 5.Youd T.L., Idriss I.M., Andrus R.D., Arango I., Castro G., Christian J.T. Liquefaction resistance of soils: summary report from the 1996 NCEER and 1998 NCEER/NSF workshops on evaluation of liquefaction resistance of soils. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng ASCE. 2001;127(10):817–833. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson P.K., Campanella R.G. Liquefaction potential of sands using the cone penetration test. J Geotech Div ASCE. 1985;111(3):384–407. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrus R.D., Stokoe K.H. Liquefaction resistance of soils from shear wave velocity. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng ASCE. 2000;108,126(11):1015–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavallaro A, Grasso S, Maugeri M, Motta E. An innovative low-cost SDMT marine investigation for the evaluation of the liquefaction potential in the Genova Harbour (Italy). In: Proceedings of the 4th international conference on geotechnical and geophysical site characterization; 2013. ISC’4 – ISBN: 978-0-415-62136-6, At Porto de Galinhas.

- 9.Maugeri M., Grasso S. Liquefaction potential evaluation at Catania Harbour (Italy) WIT Trans Built Environ. 2013;132:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monaco P., Totani G., Totani F., Grasso S., Maugeri M. Site effects and site amplification due to the 2009 Abruzzo earthquake. Earthquake Resist Eng Struct. 2009;VIII [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monaco P., Santucci de Magistris F., Grasso S., Marchetti S., Maugeri M., Totani G. Analysis of the liquefaction phenomena in the village of Vittorito (L’Aquila) Bull Earthquake Eng. 2011;9:231–261. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grasso S., Maugeri M. The seismic microzonation of the city of Catania (Italy) for the Etna Scenario Earthquake (M¼6.2) of February 20 1818. Earthquake Spectra. 2012;28(2):573–594. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grasso S., Maugeri M. The Seismic Dilatometer Marchetti Test (SDMT) for evaluating liquefaction potential under cyclic loading. Geotech Earthquake Eng Soil Dyn. 2008;IV:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samui P. Support vector machine applied to settlement of shallow foundations on cohesionless soils. Comput Goetech. 2008;35(3):419–427. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh A.T.C. Seismic liquefaction potential assessed by neural network. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng. 1994;120(9):1467–1480. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh A.T.C. Neural-network modeling of CPT seismic liquefaction data. J Geotech Eng. 1996;122(1):70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal G, Chameau JA, Bourdeau PL. Assessing the liquefaction susceptibility at a site based on information from penetration testing. Kartam N, Flood I, Garrett JH, editors. Artificial neural networks for civil engineers: fundamentals and applications, USA: New York; 1997. p. 185–214.

- 18.Ali H.E., Najjar Y.M. Neuronet-based approach for assessing liquefaction potential of soils. Transp Res Rec. 1998;1633:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najjar Y.M., Ali H.E. CPT-based liquefaction potential assessment: a neuronet approach. Geotech Spec Publ ASCE. 1998;1:542–553. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ural DN, Saka H. Liquefaction assessment by neural networks. Electronic J Geotech Engrg. <http://geotech.civen.okstate.edu/ejge/ppr9803/index.html>.

- 21.Juang C.H., Chen C.J. CPT-based liquefaction evaluation using artificial neural networks. Comput-Aid Civ Infra Eng. 1999;14(3):221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goh A.T.C. Probabilistic neural network for evaluating seismic liquefaction potential. Can Geotech J. 2002;39(39):219–232. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Javadi A.A., Rezania M., MousaviNezhad M. Evaluation of liquefaction induced lateral displacements using genetic programming. Comput Geotech. 2006;33:222–233. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young-Su K., Byung-Tak K. Use of artificial neural networks in the prediction of liquefaction resistance of sands. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng. 2006;132(11):1502–1504. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goh A.T.C., Goh S.H. Support vector machines: their use in geotechnical engineering as illustrated using seismic liquefaction data. Comput Geotech. 2007;34(5):410–421. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanckriet G.R.G., El Ghaoui L., Bhattacharyya C., Jordan M.I. Minimax probability machine. In: Dietterich T.G., Becker S., Ghahramani Z., editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 14. Cambridge: MA; MIT Press: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiangyang M., Taiyi Z. A novel minimax probability machine. Info Tech J. 2009;8(4):615–618. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J., Wang S.T., Deng Z.H., Qi Y.S. Image thresholding based on minimax probability criterion. Pattern Recogn Artif Intell. 2010;23(6):880–884. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Z., Wang Z., Sun X. Face recognition based on optimal kernel minimax probability machine. J Theor Appl Inf Tech. 2013;48(3):1645–1651. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juang C.H., Yuan H., Lee D.H., Ku C.S. Assessing CPT-based methods for liquefaction evaluation with emphasis on the cases from the Chi–Chi, Taiwan, earthquake. Soil Dyn Earthquake Eng. 2002;22(3):241–258. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ku C.S., Lee D.H., Wu J.H. Evaluation of soil liquefaction in the Chi–Chi Taiwan earthquake using CPT. Soil Dyn Earthquake Eng. 2004;24:659–673. [Google Scholar]