Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the impact of mesalamine administration on inflammatory response in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis.

METHODS: We conducted a single centre retrospective cohort study on patients admitted to our surgical department between January 2012 and May 2014 with a computed tomography -confirmed diagnosis of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. A total of 50 patients were included in the analysis, 20 (study group) had received 3.2 g/d of mesalamine starting from the day of admission in addition to the usual standard treatment, 30 (control group) had received standard therapy alone. Data was retrieved from a prospective database. Our primary study endpoints were: C reactive protein mean levels over time and their variation from baseline (ΔCRP) over the first three days of treatment. Secondary end points included: mean white blood cell and neutrophile count over time, time before regaining of regular bowel movements (passing of stools), time before reintroduction of food intake, intensity of lower abdominal pain over time, analgesic consumption and length of hospital stay.

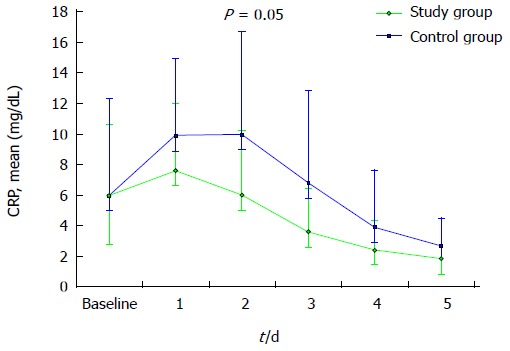

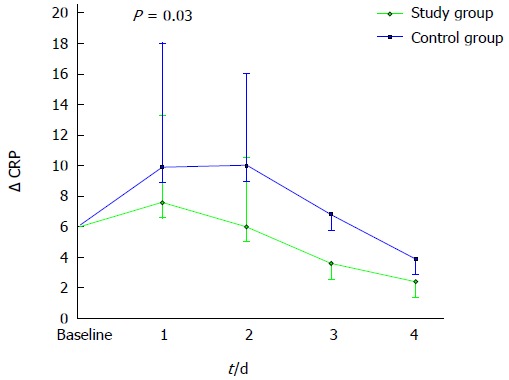

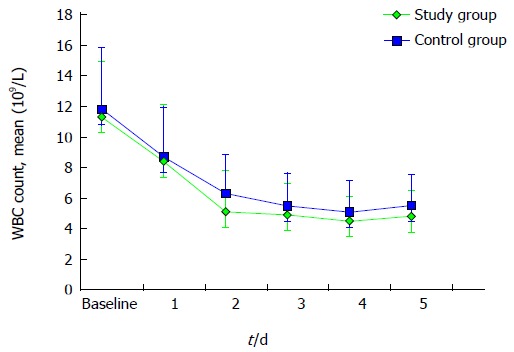

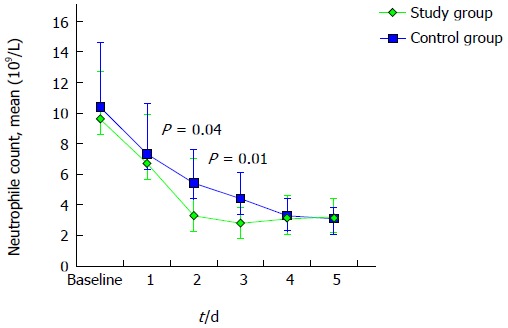

RESULTS: Patients characteristics and inflammatory parameters were similar at baseline in the two groups. The evaluation of CRP levels over time showed, in treated patients, a distinct trend towards a faster decrease compared to controls. This difference approached statistical significance on day 2 (mean CRP 6.0 +/- 4.2 mg/dL and 10.0 +/- 6.7 mg/dL respectively in study group vs controls, P = 0.055). ΔCRP evaluation evidenced a significantly greater increment of this inflammatory marker in the control group on day 1 (P = 0.03). A similar trend towards a faster resolution of inflammation was observed evaluating the total white blood cell count. Neutrophile levels were significantly lower in treated patients on day 2 and on day 3 (P < 0.05 for both comparisons). Mesalamine administration was also associated with an earlier reintroduction of food intake (median 1.5 d and 3 d, study group vs controls respectively, P < 0.001) and with a shorter hospital stay (median 5 d and 5.5 d, study group vs controls respectively, P = 0.03).

CONCLUSION: Despite its limitations, this study suggests that mesalamine may allow for a faster recovery and for a reduction of inflammatory response in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis.

Keywords: Acute diverticulitis, Inflammatory bowel disease, 5-ASA, Benign colonic disease

Core tip: Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis is the most common presentation of symptomatic diverticular disease. Taking the lead from evidence suggesting that acute uncomplicated diverticulitis may represent a form of inflammatory bowel disease, our study investigated, to our knowledge for the first time, the impact of oral mesalamine administration on early inflammatory parameters. When compared to standard therapy alone, mesalamine addition seemed to allow for a faster decrease of inflammation and for a faster recovery of the patients. Despite the limitations inherent in the study design, the results may , in our opinion, constitute the basis for future randomized, placebo-controlled, studies.

INTRODUCTION

Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis is the most common presentation of symptomatic diverticular disease and represents an important economical burden for the health-care systems of western countries[1-6]. Notions about the pathogenesis of this disease are still controversial and so is the choice of the best treatment strategy[7,8]. Most guidelines[9-11] indicate bowel rest, intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics as standard treatment, however, evidence supporting this kind of recommendation is scarce and of low quality[12,13]. Some authors have suggested that this condition may arise from an inflammatory process rather than from an infective one, thus supporting a rationale for the use of anti-inflammatory drugs[14]. A number of studies have explored the role of 5-ASA preparations, and especially of mesalamine in treating chronic symptoms and reducing the rate of recurrence after a first episode of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis, with promising but inconsistent results[15-20]. Evidence regarding the effectiveness of this drug during the acute phase of the disease, however, is still scarce. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of high dosage mesalamine administration in modulating the inflammatory response in acute uncomplicated left-sided diverticulitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study on patients diagnosed with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and admitted to our surgical department between January 2012 and May 2014. Data was retrieved from an institutional prospective database and covered the period of hospitalization.

The patients considered for evaluation were aged over 18 years, had a computed tomography (CT) scan-confirmed diagnosis of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis (staged Hinchey 1A or 1B) and had received 3.2 g/d of mesalamine for the duration of their in-hospital stay in addition to the usual standard therapy. They were compared to a group of controls admitted to our department at the same period of time with a CT-confirmed diagnosis of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and treated without mesalamine. Exclusion criteria were: a known history of peptic ulcer, recent surgery on the gastrointestinal tract, inflammatory bowel disease, short bowel syndrome or other condition causing malabsorption or altered bowel mobility, endometriosis/dysmenorrhea, major medical or psychiatric diseases, immunodepression, recent consumption (during the preceding 4 wk) of antibiotics, steroids or products containing mesalamine. In accordance with with current guidelines, all patients were prescribed broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and fluid support by the attending surgeon, who was also in charge of deciding the timing for the resumption of oral food intake and discharge. In the period of interest, our internal protocol for antibiotic therapy included a combination of quinolones and metronidazole given intravenously to all patients that were not allergic or intolerant. Recovery was assessed on the basis of a clinical decision.

The decision to add mesalamine to the standard therapy was taken independently by the attending physician, on the basis of evidence that relates mesalamine administration in such a setting to a possible improvement of long-term symptoms[15-17]. Treated patients received 3.2 g of mesalamine/d by way of two 800 mg tablets (Asamax, Astellas Pharma Inc, Chuo-ku, TKY, Japan) subministered twice daily. The dosing schedule was chosen in accordance with the existing data regarding the use of mesalamine in acute ulcerative colitis (UC) that indicates a daily dosage of between 2.4 g/die and 4.8 g/die to be a safe and effective induction therapy for patients with mild to moderately active UC[21] and in conformity with the most recent trials on the use of mesalamine in diverticular disease[20,22]. A daily administration regimen was preferred on the basis of evidence that it is more effective in inducing and maintaining remission than cyclical administration[23]. The length of treatment prosecution following hospital discharge was defined for each patient by the attending physician.

Laboratory assessments of serum white blood cells (WBC), neutrophiles and C reactive protein (CRP) levels where performed and evaluated with reference to the normal ranges applied locally. The administration of analgesic medication was taken into account and registered for each day. A 0-10 Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) score for lower abdominal pain was assigned daily following usual ward practice. Time before recovery of normal bowel function (passing of stools) and time before resumption of oral food intake were also recorded. All clinical and biochemical data were reported on a case-report form and entered into the database.

The primary endpoints of the study included mean daily levels of serum CRP and their variation during the first three days of in-patient treatment. Variation was defined as the difference between CRP mean values for each day of treatment and baseline. Baseline levels were defined using the results of laboratory assessments done in the emergency room during the initial patient evaluation. Secondary endpoints were: daily WBC and neutrophile count, intensity of lower abdominal pain over time, analgesic consumption, time before recovery of normal bowel function (passing of stools), time before resumption of oral food intake and length of in-hospital stay.

Descriptive statistics for continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD as well as median (range). Discrete data were summarized as numbers and percentages. For continuous variables, the t-test or the Mann-Whitney test were used, depending on normality distribution assumption. For categorical variables the χ2 test was used.

For all statistical analyses, a two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses was carried out using the Epi Info 3.5.1 software package for Windows and the SPSS Statistics 22.0 standard software package.

RESULTS

During the period of interest, 50 eligible patients were admitted to our surgical department with a CT-confirmed diagnosis of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. 20 were treated with mesalamine in addition to the usual standard theraphy while 30 patients received standard therapy alone.

Baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. A compared analysis shows that the two groups are balanced in terms of age, sex and co-morbidities. Mean age was 59.9 ± 15.7 years in the study group and 66.5 ± 15.4 years in the control group; 60% (12/20) of study patients and 63.3% (19/30) of control patients were women. The most frequent co-morbid conditions were type 2 diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension. Other conditions included: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), kidney failure, asthma, coronary artery disease and glaucoma. The average Body Mass Index (BMI) appeared to be higher in the control group (mean 24.8 ± 3.8 kg/m2 for the study group and 28.9 ± 5.8 kg/m2 for the control group, P = 0.01). A known history of prior episodes of diverticulitis was more frequent in the study group than among controls (positive history in 5/20 patients, 25.0% in the study group and 1/30 patients, 3.4% in the control group), along with a higher incidence of Hinchey IB diverticulitis, which was recorded in 5/20 patients (25%) in the study group and in 2/30 patients (6.7%) in the control group (P = 0.07). Time from the outbreak of the first symptoms to admission was comparable in the two groups. Baseline levels for inflammatory parameters and scores for lower abdominal pain were found to be similar in the two groups. Namely, mean CRP at the time of admission was 6.0 ± 4.6 mg/dL and 6.0 ± 6.3 mg/dL in the study group and in controls, respectively, (P = 0.41).

Table 1.

Baseline

| Study patients | Control patients | P value | |

| (n = 20) | (n = 30) | ||

| Age (yr)1 | 59.9 ± 15.7 | 66.5 ± 15.4 | 0.15 |

| Sex (F)2 | 12 (60.0) | 19 (63.3) | 0.81 |

| BMI (kg/m²)1 | 24.8 ± 3.8 | 28.9 ± 5.8 | 0.01 |

| Arterial hypertension2 | 11 (55) | 13 (43.3) | 0.42 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus2 | 1 (5) | 5 (16.7) | 0.21 |

| Recurrent episode2 | 5 (25) | 1 (3.4) | 0.02 |

| Hinchey IB2 | 5 (25) | 2 (6.7) | 0.07 |

| Time to admission (d)1 | 2.3 ± 2.1 | 2.3 ± 2 | 0.99 |

| CRP (mg/dL)3 | 6 ± 4.6 | 6 ± 6.3 | 0.41 |

| WBC (109/L)1 | 12.5 ± 3.6 | 13 ± 4 | 0.62 |

| Neutrophiles (109/L)1 | 9.6 ± 3.1 | 10.4 ± 4.2 | 0.45 |

| Pain (NRS score)3 | 3.9 ± 2.8 | 4.5 ± 2.4 | 0.55 |

Data as mean ± SD, t-test;

Data as n (%), χ2 test;

Data as mean ± SD, Mann Whitney test.

Figure 1 represents CRP plasma levels over time. A distinct trend towards a faster decrease of this parameter can be evidenced in study patients if compared to controls. This difference approached statistical significance on day 2 (mean CRP 6.0 ± 4.2 mg/dL and 10.0 ± 6.7 mg/dL, in study group and controls, respectively, P = 0.05).

Figure 1.

C reactive protein levels. Mean C reactive protein (CRP) levels, over time, in the two groups.

We evaluated the variation of CRP levels over the first three days (ΔCRP). This parameter represents the differential between CRP measurements obtained daily and expressed as a mean value for each group and CRP at baseline. As shown in Figure 2, a significantly greater increment of Δ CRP was observed in control patients on day 1 (ΔCRP 1.4 ± 2.7 mg/dL and 4.7 ± 6.0 mg/dL in study group and controls, respectively, P = 0.03).

Figure 2.

C reactive protein mean levels over time and their variation from baseline. C reactive protein (CRP) variation from baseline, over time, in the two groups. Δ CRP = mean CRP - mean CRP at baseline.

A similar trend towards a faster resolution of inflammation was observed evaluating the total WBC and neutrophile count, as described in Figures 3 and 4. Mean neutrophile levels were significantly lower in treated patients on day 2 (P = 0.04) and on day 3 (P = 0.01).

Figure 3.

White blood cells count. Mean white blood cells (WBC) count, over time, in the two groups.

Figure 4.

Neutrophile count. Mean neutrophile count, over time, in the two groups.

The evaluated clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 2. A shorter time to resumption of oral food intake (median 1 d, range 1-4 d and median 3 d, range 1-5 d for the study group and controls, respectively, P < 0.001) and a reduced length of in-hospital stay (median 5 d, range 3-6 and median 5.5 d, range 4-12 d for the study group and controls, respectively, P = 0.03) were observed in treated patients when compared to controls.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes

| Study group | Control group | P value1 | |||

|

(n = 20) |

(n = 30) |

||||

| mean ± SD | Median (range) | mean ± SD | Median (range) | ||

| Time before recovery of bowel function (d) | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 1.5 (1-4) | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 3 (0-7) | 0.29 |

| Time before resumption of food intake (d) | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1 (1-4) | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 3 (1-5) | < 0.001 |

| Length of in-hospital stay (d) | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 5 (3-6) | 6 ± 2.1 | 5.5 (4-12) | 0.03 |

Mann-Whitney test.

Pain levels for both groups decreased rapidly from baseline during in-hospital treatment; a difference in favor of control patients was found on day 3 (mean NRS score 1.1 ± 1.4 and 0.4 ± 1.1, study group and controls, respectively, P = 0.05) while a trend towards a more consistent analgesic consumption, though not statistically significant, was observed in controls (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pain and analgesics consumption n (%)

| Study patients | Control patients | P value | ||||

|

(n = 20) |

(n = 30) |

|||||

| Median (range) | mean ± SD | Median (range) | mean ± SD | |||

| Pain (NRS score) | Day 1 | 2 (0-7) | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 2 (0-8) | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 0.411 |

| Day 2 | 1.5 (0-8) | 1.9 ± 2.3 | 0 (0-4) | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.141 | |

| Day 3 | 0 (0-3) | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 0 (0-5) | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 0.051 | |

| Analgesy | Day 1 | 11 (55) | 22 (73.3) | 0.182 | ||

| Day 2 | 13 (65) | 19 (63.3) | 0.902 | |||

| Day 3 | 7 (35) | 14 (46.7) | 0.412 | |||

Mann-Whitney test;

Date is χ2 test. Analgesy represents the proportion of patients assuming pain medications.

DISCUSSION

The traditional pathogenic model for diverticular disease has recently been challenged. Evidence exists showing, in patients suffering from diverticular disease, the presence of chronic microscopic and macroscopic inflammatory alterations of the mucosa, similar to those found in inflammatory bowel disease which may contribute to the genesis of this condition[24,25]. Moreover, a recent trial in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis has shown a lack of effect of intravenous antibiotics, suggesting a possible role of inflammation in determining the genesis and the course of this condition[13]. For these reasons, a new interest has risen for the potential use of anti-inflammatory medication in such a setting.

A number of studies have shown that mesalamine (alone or in combination with antibiotics) could represent a promising therapeutic option for treating chronic symptoms and preventing recurrence in diverticular disease. Two four-armed open label trials[15,16] have shown mesalamine to be more effective than rifaximin in achieving symptomatic relief over a 3 mo period. A randomized open label study by Tursi et al[17] demonstrated an 85% reduction in recurrent attacks of diverticulitis in patients treated with a combination of mesalamine and rifaximine as compared to rifaximine alone, a result which was consistent with a previous open label study on the effects of Mesalamine supplementation after a first attack of acute diverticulitis[18]. More recently, an intermittent prophylaxis with Mesalamine was shown to be more effective than placebo in controlling chronic symptoms and to allow for a reduction in the consumption of additional gastrointestinal drugs[19]. One large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial[20] employing a high dosage of mesalamine (3 g/d) administered from the day of admission to patients suffering from acute uncomplicated diverticulitis showed, on a long term evaluation, a higher rate of complete relief from chronic symptoms in patients that had received mesalamine. Similar findings were evidenced by a study of similar design that evaluated the effects of a 2.4 g/die mesalamine administration during a symptomatic flare of uncomplicated divericular disease[22]. The potential role of this drug in modulating acute inflammatory response, however, has not been further determined.

This retrospective cohort study is the first, to our knowledge, to evaluate the impact of mesalamine on early inflammatory response in uncomplicated diverticulitis. As an acute-phase reactant, CRP is strictly related to the inflammatory stimulus, its values increase and decrease promptly due to its short half-life[26]. This parameter has been shown to be the best marker in assessing response to therapy in acute diverticulitis as well as a useful tool for diagnosis[27]. It also correlates with the severity of the disease and with the presence of complications[28,29]. In our population we observed baseline CRP levels comparable to those described by other authors as well as a more rapid decrease of the same levels, over time, in the study group. The relative advantage for patients treated with Mesalamine over patients that had received antibiotics alone may be attributable to the anti-inflammatory properties of Mesalamine and be conductible to a preponderant pathogenic role of inflammation in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis.The similar trend observed over time for the WBC and neutrophile count seems to offer further confirmation of this interpretation.

Data on the length of in-hospital stay and time to resumption of oral food intake are not easly comparable to other studies since they are strongly influenced by local policies. Gastrointestinal transit is known to be altered in a variety of mucosal inflammatory conditions of the gut. In vivo and in vitro studies suggest that mediators such as interleukin 1β and interleukin 6, modulation of the lymphocyte function via the major histocompatibility complex II and neural modulation of intestinal inflammation through pro-inflammatory molecules could all play a role in this phenomenon[30]. In light of these studies, the observed trend towards an earlier recovery of bowel function and earlier resumption of oral food intake in treated patients may be attributable to a faster reduction of local inflammation. This may possibly have ultimately led to the earlier discharge of the patients. Several limitations inherent in the study design, however, should be taken into account when evaluating clinical outcomes. The absence of randomization and blinding and the lack of strict criteria for discharge may have led to an overestimation of these results.

Our study did not show any advantage for study patients over controls with reference to abdominal pain scores. This was in contrast with two previous studies[19,22] that showed that mesalamine may relieve symptoms during symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD).This discrepancy might be related to the different mechanisms that may underlie pain generation in acute and in chronic settings.In fact, it has been suggested that the pathogenesis of pain in SUDD patients, could be related, at least in part, to changes in neuromuscular function[31] secondary to chronic low-grade inflammation rather than to an acute inflammatory process. Moreover, the absence of regulation of the concomitant use of analgesics has already been cited as a potential confounding factor[22]. Their higher consumption in the control group may have influenced the proportion of patients reporting symptomatic improvement. A stricter definition of the rules for the clinical management of patients, with special reference to timing for discharge and re-feeding and to criteria for pain assessment and antibiotic prescription, would be useful when evaluating clinical parameters.

Potential limitations inherent to the study design were a possible selection bias and the limited sample size. Nevertheless, these preliminary results suggest that mesalamine may possibly be effective in treating acute uncomplicated diverticulitis, allowing for a faster recovery and for a more rapid decrease of certain objective inflammatory markers. This could possibly lead to an earlier discharge with benefit to the patient and a reduction in health-care costs. Further, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials are needed to obtain confirmation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mrs. Mabel Evaetta Morton for her support in the language revision of the manuscript.

COMMENTS

Background

Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis is the most common presentation of symptomatic diverticular disease. At present, treatment consists in bowel rest, broad-spectrum antibiotics and intravenous fluids, often in an in-hospital setting. The clinical course is characterized by the progressive decrease of inflammatory parameters and of local pain. Usually, the reintroduction of solid food intake and the discharge of patients are decided on clinical basis.

Research frontiers

Recently, evidence has been provided showing similarities between acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and inflammatory bowel diseases, supporting the idea that local inflammation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of both conditions. This suggests a potential role for anti-inflammatory compounds, such as mesalamine, in this disease.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Despite the positive results observed in long-term mesalamine administration in patients suffering from diverticular disease, the effects on inflammatory parameters during the acute flare have not been thoroughly investigated so far. In this retrospective analysis, the authors observed a beneficial effect of mesalamine on inflammation, consisting in lower serum CRP levels and in their faster decrease in treated patients, if compared to controls. The earlier resumption of solid food intake and the shorter hospital stay the authors observed in treated patients, also seemed consistent with a faster resolution of local inflammation.

Applications

This retrospective cohort study, despite the limitations intrinsic to the study design and despite the limited sample size, has shown a potential role for mesalamine administration in speeding the resolution of acute inflammation in patients suffering from acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. This would allow for shorter hospitalization with benefit to the patients and a reduction in health care costs.

Terminology

Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: Self-limited and confined inflammation of diverticula in the absence of abscess, macroperforation, fistula or peritonitis. Symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: Symptomatic diverticulosis characterized by abdominal symptoms (abdominal pain, particularly in the lower left abdominal quadrant and alteration of bowel habits) without macroscopic signs of inflammation (no mucosal inflammation on colonoscopy, no increase in erythrocyte sedimentation rate or CRP, no fever).

Peer-review

The authors described the first experience in using high doses of mesalamine in speeding resolution of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis on a retrospective analysis. Authors found that mesalamine supplementation, when compared to standard therapy alone, seemed to allow for a faster decrease of acute inflammatory parameters and for a faster recovery of the patients. These results are described for the first time and, despite the retrospective design of the study, are of interest for clinical practice

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: Because of the retrospective design, approval of the ethic commission was not required in our institution.

Informed consent statement: Not required for retrospective study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no existing conflict of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: February 12, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Article in press: May 7, 2015

P- Reviewer: Cologne KG, Tursi A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, Adams E, Cronin K, Goodman C, Gemmen E, Shah S, Avdic A, Rubin R. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–1511. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martel J, Raskin JB. History, incidence, and epidemiology of diverticulosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1125–1127. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181865f18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Painter NS, Burkitt DP. Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of Western civilization. Br Med J. 1971;2:450–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5759.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jun S, Stollman N. Epidemiology of diverticular disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:529–542. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delvaux M. Diverticular disease of the colon in Europe: epidemiology, impact on citizen health and prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18 Suppl 3:71–74. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-0673.2003.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papagrigoriadis S, Debrah S, Koreli A, Husain A. Impact of diverticular disease on hospital costs and activity. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:81–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humes DJ, Spiller RC. Review article: The pathogenesis and management of acute colonic diverticulitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:359–370. doi: 10.1111/apt.12596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tursi A. New physiopathological and therapeutic approaches to diverticular disease: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:1005–1017. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.903922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stollman NH, Raskin JB. Diagnosis and management of diverticular disease of the colon in adults. Ad Hoc Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3110–3121. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rafferty J, Shellito P, Hyman NH, Buie WD. Practice parameters for sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:939–944. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andeweg CS, Mulder IM, Felt-Bersma RJ, Verbon A, van der Wilt GJ, van Goor H, Lange JF, Stoker J, Boermeester MA, Bleichrodt RP. Guidelines of diagnostics and treatment of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis. Dig Surg. 2013;30:278–292. doi: 10.1159/000354035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Korte N, Unlü C, Boermeester MA, Cuesta MA, Vrouenreats BC, Stockmann HB. Use of antibiotics in uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2011;98:761–767. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, Haapaniemi S, Smedh K. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:532–539. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tursi A, Papagrigoriadis S. Review article: the current and evolving treatment of colonic diverticular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:532–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Mario F, Aragona G, Leandro G, Comparato G, Fanigliulo L, Cavallaro LG, Cavestro GM, Iori V, Maino M, Moussa AM, et al. Efficacy of mesalazine in the treatment of symptomatic diverticular disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:581–586. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2478-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comparato G, Fanigliulo L, Cavallaro LG, Aragona G, Cavestro GM, Iori V, Maino M, Mazzocchi G, Muzzetto P, Colla G, et al. Prevention of complications and symptomatic recurrences in diverticular disease with mesalazine: a 12-month follow-up. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2934–2941. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Daffinà R. Long-term treatment with mesalazine and rifaximin versus rifaximin alone for patients with recurrent attacks of acute diverticulitis of colon. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:510–515. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trepsi E, Colla C, Panizza P, Polino MG, Venturini A, Bottani G, De Vecchi P, Matti C. [Therapeutic and prophylactic role of mesalazine (5-ASA) in symptomatic diverticular disease of the large intestine. 4 year follow-up results] Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 1999;45:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parente F, Bargiggia S, Prada A, Bortoli A, Giacosa A, Germanà B, Ferrari A, Casella G, De Pretis G, Miori G. Intermittent treatment with mesalazine in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence: a randomised multicentre pilot double-blind placebo-controlled study of 24-month duration. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1423–1431. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stollman N, Magowan S, Shanahan F, Quigley EM. A randomized controlled study of mesalamine after acute diverticulitis: results of the DIVA trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:621–629. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31828003f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feagan BG, Macdonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD000543. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000543.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruis W, Meier E, Schumacher M, Mickisch O, Greinwald R, Mueller R. Randomised clinical trial: mesalazine (Salofalk granules) for uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon--a placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:680–690. doi: 10.1111/apt.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Elisei W. Continuous versus cyclic mesalazine therapy for patients affected by recurrent symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:671–674. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghorai S, Ulbright TM, Rex DK. Endoscopic findings of diverticular inflammation in colonoscopy patients without clinical acute diverticulitis: prevalence and endoscopic spectrum. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:802–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Elisei W, Giorgetti GM, Inchingolo CD, Danese S, Aiello F. Assessment and grading of mucosal inflammation in colonic diverticular disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:699–703. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180653ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tursi A. Biomarkers in diverticular diseases of the colon. Dig Dis. 2012;30:12–18. doi: 10.1159/000335695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridgway PF, Latif A, Shabbir J, Ofriokuma F, Hurley MJ, Evoy D, O’Mahony JB, Mealy K. Randomized controlled trial of oral vs intravenous therapy for the clinically diagnosed acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:941–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andeweg CS, Knobben L, Hendriks JC, Bleichrodt RP, van Goor H. How to diagnose acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis: proposal for a clinical scoring system. Ann Surg. 2011;253:940–946. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182113614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tursi A, Elisei W, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Aiello F. Predictive value of serologic markers of degree of histologic damage in acute uncomplicated colonic diverticulitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:702–706. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181dad979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins SM. The immunomodulation of enteric neuromuscular function: implications for motility and inflammatory disorders. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1683–1699. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson J, Scholefield JH, Spiller RC. Origin of symptoms in diverticular disease. Br J Surg. 2003;90:899–908. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]