Abstract

Background and Purpose

Transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels play important roles in a broad array of physiological functions and are involved in various diseases. However, due to a lack of potent subtype-specific inhibitors the exact roles of TRPC channels in physiological and pathophysiological conditions have not been elucidated.

Experimental Approach

Using fluorescence membrane potential and Ca2+ assays and electrophysiological recordings, we characterized new 2-aminobenzimidazole-based small molecule inhibitors of TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels identified from cell-based fluorescence high-throughput screening.

Key Results

The original compound, M084, was a potent inhibitor of both TRPC4 and TRPC5, but was also a weak inhibitor of TRPC3. Structural modifications of the lead compound resulted in the identification of analogues with improved potency and selectivity for TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels. The aminobenzimidazole derivatives rapidly inhibited the TRPC4- and TRPC5-mediated currents when applied from the extracellular side and this inhibition was independent of the mode of activation of these channels. The compounds effectively blocked the plateau potential mediated by TRPC4-containing channels in mouse lateral septal neurons, but did not affect the activity of heterologously expressed TRPA1, TRPM8, TRPV1 or TRPV3 channels or that of the native voltage-gated Na+, K+ and Ca2+ channels in dissociated neurons.

Conclusions and Implications

The TRPC4/C5-selective inhibitors developed here represent novel and useful pharmaceutical tools for investigation of physiological and pathophysiological functions of TRPC4/C5 channels.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | ||

|---|---|---|

| GPCRsa | Ion channelsb | |

| μ receptor | TRPA1 | TRPM8 |

| 5-HT1A receptor | TRPC1 | TRPV1 |

| M2 receptor | TRPC2 | TRPV3 |

| M3 receptor | TRPC3 | Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels |

| M5 receptor | TRPC4 | Voltage-gated K+ channels |

| TRPC5 | Voltage-gated Na+ channels | |

| TRPC6 | ||

| TRPC7 |

| LIGANDS | |

|---|---|

| 2-APB | Flufenamic acid (FFA) |

| 5-HT | Menthol |

| Capsaicin | ML204 |

| Carbachol (CCh) | Riluzole |

| DAMGO | SKF96365 |

| DHPG |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,bAlexander et al., 2013a, b).

Introduction

The superfamily of transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels in mammals consists of six subfamilies: TRPC (canonical), TRPV (vanilloid), TRPM (melastatin), TRPA (ankyrin), TRPP (polycystin) and TRPML (mucolipin; Montell et al., 2002). TRPC channels are typically activated downstream from stimulation of PLC (Plant and Schaefer, 2003; Trebak et al., 2007). However, which step(s) or constituent(s) of the PLC pathway is the most critical for TRPC activation is not well defined. The mammalian TRPC family has seven members, TRPC1–7, and based on sequence similarities, they are separated into four groups: TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC3/C6/C7 and TRPC4/C5. TRPC2 is a pseudogene in humans. TRPC3/C6/C7 can be directly activated by diacylglycerols (Hofmann et al., 1999). TRPC4/C5 appears to respond to receptors that activate Gi/o signalling in addition to the Gq/11-PLC pathway (Jeon et al., 2008; 2012; Otsuguro et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2014). Because PLC activation is commonly achieved by the stimulation of GPCRs or receptor tyrosine kinases, the TRPC channels are also referred to as receptor-operated channels (Plant and Schaefer, 2003).

Functionally, TRPC channels are non-selective cation channels that mediate Na+ and Ca2+ entry into cells, leading to membrane depolarization and an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). The rise in Na+ level at the cytoplasmic side could also be important for Na+-dependent transport (Eder et al., 2005). However, because of a lack of pharmacological tools, the physiological roles of TRPC can often only be determined in studies in TRPC mutant animals or in human patients who bear naturally occurring mutations in TRPC genes. These studies have generated a long list of TRPC-dependent functions, including neurotransmission, fear response and neurodegeneration in the nervous system (Munsch et al., 2003; Riccio et al., 2009; 2014; Phelan et al., 2012), excitation and contraction coupling and muscle tone of smooth muscles (Welsh et al., 2002; Tsvilovskyy et al., 2009), as well as regulation of endothelial permeability in the vasculature and filtration in the kidney (Tiruppathi et al., 2002; Winn et al., 2005). Currently, the roles of TRPC channels in normal and pathological conditions are under extensive investigation.

The scarcity of TRPC probes has severely hampered the characterization of these channels in their assembly, function and role in pathophysiology. Using a cell-based high-throughput fluorescence assay to screen for TRPC4 probes from the Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) supported by the Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network (MLPCN), we have identified a small group of compounds that act as antagonists of TRPC4. We have previously reported that ML204, a quinoline compound, potently and selectively inhibited TRPC4 with an IC50 value of 0.96 μM (Miller et al., 2011a). ML204 was later shown to inhibit visceral pain in a dose-dependent manner (Westlund et al., 2014) and to protect kidney filter function (Schaldecker et al., 2013). Here, we describe the characterization and optimization of an (amino)benzimidazole-based compound, M084, from the same screen. Although not as potent as ML204, the M084 derived compounds have improved stability and kinetics for inhibiting TRPC4/C5. Hence, M084 provides an alternative structural scaffold for further development of more potent TRPC4/C5-selective antagonists.

Methods

Cell lines and cell culture

HEK293 cells were grown in DMEM (high glucose) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U·mL−1 penicillin, and 100 μg·mL−1 streptomycin at 37°C, 5% CO2. The stable cell line that inducibly expressed human TRPA1 was made and used as described previously (Hu et al., 2009). Rat TRPV1 was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells seeded in wells of 96-well plates and these cells were used for the Ca2+ assay 20 h post-transfection as described previously (Hu et al., 2004). Stable cell lines that express human TRPC3, or mouse TRPC4β, TRPC5, TRPC6, TRPC7, TRPV3 or TRPM8 were established as described previously (Miller et al., 2011a) and maintained in the above medium supplemented with G418 (400 μg·mL−1; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels were also co-expressed with μ receptors or 5-HT1A receptors in these stable cell lines. The TRPC6 cell line also stably expressed the M5 muscarinic receptor. For all GPCRs, the receptor cDNA was placed in the pIREShyg2 vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) and the cell lines stably co-expressing TRPCs and GPCRs were maintained in the medium containing 400 μg·mL−1 G418 and 50 μg·mL−1 hygromycin B (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA). For the stable cell line co-expressing TRPC1 and TRPC4, human TRPC1 cDNA was placed in a modified pIRESneo vector (Clontech) with the neomycin-resistant gene replaced by the zeocin-resistant one and transfected to the stable cell line that expressed TRPC4β and the M2 receptor. The cells were maintained in 100 μg·mL−1 zeocin (Invitrogen), in addition to G418 and hygromycin B. The nomenclature for receptors and ion channels conforms to BJP's Concise Guide to Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2013a, b).

Fluorescence Ca2+ and membrane potential assays

HEK293 cells stably expressing the desired channel and receptor types were seeded in wells of 96-well plates pre-coated with polyornithine (20 μg·mL−1, molecular weight >30 000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 1 × 105 cells per well and grown for >16 h. Cells were loaded with either Fluo 4-AM to monitor intracellular Ca2+ changes or the FLIPR membrane potential dye (FMP, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) to monitor membrane potential changes by using the FlexStation microplate reader (Molecular Devices) following previously described protocols (Hu et al., 2004; Otsuguro et al., 2008). Either the original FMP or FLIPR membrane potential dye II (FMP II) was used. The extracellular solution for all FlexStation assays contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose and 10 HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.4 by NaOH. Probenecid (2 mM) was included in all Ca2+ assays except for TRPV1. Assays were run at 32°C, except for TRPV1 and TRPA1, which were carried out at room temperature (∼22°C).

Electrophysiological recordings

HEK293 cells stably expressing the desired TRPC channels were seeded in 35 mm dishes one day before whole-cell recordings were performed. Recording pipettes were pulled from standard wall borosilicate tubing with filament (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, USA) to 2–4 MΩ when filled with a pipette solution containing (in mM) 110 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 6.46 CaCl2, 10 BAPTA, (with the estimated free [Ca2+] of ∼400 nM), 10 HEPES, with the pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH, and placed in the bath solution of the same composition as the extracellular solution used for the Ca2+ assay. Isolated cells were voltage-clamped in the whole-cell mode using an EPC9 (HEKA Instruments, Bellmore, NY, USA) amplifier. Voltage commands were made from the PatchMaster program (version 2.60; HEKA), and currents were recorded at 5 kHz. Voltage ramps of either 200 or 500 ms to −100 mV after a brief (20 ms) step to +100 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV were applied every 1 or 2 s. Cells were continuously perfused with the bath solution through a gravity-driven multi-outlet device with the desired outlet placed about 50 μm away from the cell being recorded. Drugs were diluted in the extracellular solution to the desired final concentrations and applied to the cell through perfusion.

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the US National Institutes of Health. The use of mice and animal protocols were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 12 animals were used for this study. Preparation of mouse brain slices and recordings of agonist-evoked plateau potential from lateral septal neurons in brain slices by whole-cell current clamp methods were as described previously (Tian et al., 2014).

Isolation of mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons and whole-cell recordings to test the effects of the compound on voltage-gated Na+, K+ and Ca2+ channels in isolated DRG neurons were essentially carried out as previously described (Miller et al., 2011a). For Na+ channels, the pipette solution had (in mM) 140 CsCl, 5 NaCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 2 Na-ATP, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2; bath had 35 NaCl, 110 choline-Cl, 1.2 MgCl2, 0.15 CaCl2, 0.2 CdCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. For K+ channels, the pipette solution had (in mM): 130 K-methanesulfonate, 7 KCl, 0.05 EGTA, 1 Na2ATP, 3 MgATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2; bath had 140 choline-Cl, 5 KCl, 2 CoCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. For Ca2+ channels (in mM), pipette solution had (in mM) 117 CsCl, 1.8 MgCl2, 9 EGTA, 14 Tris-creatine phosphate,4 MgATP, 0.3 TrisGTP, 9 HEPES, pH 7.2; bath had 130 tetraethylammonium-Cl, 10 BaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.0004 tetrodotoxin, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. Voltage protocols are shown in the figure.

Compounds and combinatorial chemical library synthesis

A series of novel 2-aminobenzimidazole derivatives were prepared as reported previously (Zhu et al., 2013). Most of the compounds were synthesized from the commercially available 2-chloro-1H benzo[d]imidazole and amines using methyl-1-butanol or MeOH as the solvent under microwave irradiation. A small number of compounds was purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich and ChemBridge (San Diego, CA, USA). The structures and sources of all compounds tested in the current study are listed in Table 1. 2-Amino-6-(trifluoromethoxy)benzothiazole (riluzole) was from Matrix Scientific (Columbia, SC, USA). Capsaicin, carbamoylcholine (carbachol or CCh), [D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-Enkephalin (DAMGO), flufenamic acid (FFA), 5-HT, menthol were from Sigma-Aldrich. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2APB) was from Cayman Chemical Co (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Table 1.

SAR evaluation of benzimidazole derivatives on TRPC4

Benzimidazole backbone Benzimidazole backbone | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Position 2 | Position 1 | Position 5 | Source | Inhibition at 22 μM |

| M084 |  |

-H | -H | Resynthesized | 93% |

| 2 | -NH2 | -H | -H | SA: 171778 | No |

| 3 |  |

-H | -H | SA: 572721 | No |

| 4 |  |

-H | -H | SA: L200263 | 13% |

| 5 | -NH2 |  |

-H | SA: L202517 | 24% |

| 6 |  |

-H | -H | SA: S441503 | No |

| 7 |  |

-H | -H | SA: S62597 | No |

| 8 |  |

|

-H | SA: T320684 | 21% |

| 9 |  |

-H | -Cl | SA: T320722 | 92% |

| 10 |  |

-H | -Cl | SA: T135674 | No |

| 11 |  |

-H | -Cl | SA: T320625 | No |

| 12 |  |

-H | -Cl | SA: T320633 | No |

| 13 |  |

-H | -H | SA: T320676 | 94% |

| 14 |  |

-H | -H | CB: 4003377 | No |

| 15 |  |

-H | -H | CB: 4033874 | No |

| 16 |  |

-H | -H | CB: 4034369 | 87% |

| 17 |  |

-H | -H | CB: 4034623 | 95% |

| 18 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 19 |  |

-CH3 | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 20 |  |

-CH3 | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 21 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 22 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 23 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 24 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 25 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | No |

| 26 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | 31% |

| 27 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | 80% |

| 28 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | 97% |

| 29 |  |

-H | -H | New synthesis | No |

Functional assay performed by fluorescence membrane potential measurements of DAMGO-evoked response in cells co-expressing TRPC4β and μ receptors. CB, ChemBridge; SA, Sigma-Aldrich.

Results

M084 selectively inhibits TRPC4 and TRPC5

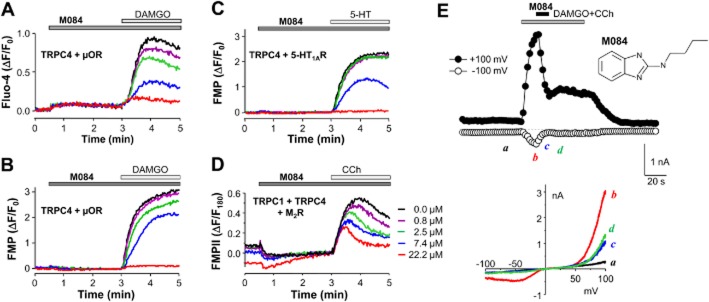

Using a stable HEK293 cell line co-expressing mouse TRPC4β and μ-opioid receptors, we conducted high-throughput screening for compounds that affect TRPC4 channel function by measuring μ receptor agonist, DAMGO, evoked intracellular Ca2+ rise (Miller et al., 2011a, b). One of the primary hits (CID 284016) identified from the screening of a total of 305 000 compounds in the MLSMR library was n-butyl-1h-benzimidazol-2-amine (M084, Figure 1E inset). The compound was resynthesized and tested for activity on TRPC4β channels stably co-expressed with μ receptors using the Ca2+ assay (Figure 1A), from which the IC50 was estimated to be 3.7 ± 0.5 μM (n = 10) when DAMGO was used at 0.1 μM. Using the same cell line, we also performed a fluorescence membrane potential assay, which represents a different assay from the primary screening. As shown in Figure 1B, with the cells loaded with the FMP, DAMGO (0.1 μM) induced a robust increase in fluorescence intensity in the cells expressing TRPC4 + μ receptors, indicating membrane depolarization. This response was specific for μ receptor-mediated TRPC4 activation as DAMGO failed to induce fluorescence increases in cells that expressed either TRPC4β or μ receptors alone or wild-type HEK293 cells (data not shown, but see Miller et al., 2011b). Pre-incubation with M084 did not cause any appreciable change in the fluorescence signal but attenuated the DAMGO-evoked increase in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50 = 10.3 ± 0.5 μM, n = 12, Table 2). Similarly, in cells that co-expressed TRPC4β with 5-HT1A receptors, the fluorescence increase evoked by 5-HT (1 μM) was also inhibited by pre-incubation with M084 (Figure 1C). In addition, M084 inhibited CCh (1 μM)-evoked membrane depolarization in cells that co-expressed TRPC1, TRPC4β and M2 receptors in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1D), with an estimated IC50 of 8.3 ± 1.7 μM (n = 6), suggesting that the compound also acts on the TRPC1/C4 heteromeric channels. In whole-cell voltage clamp recordings, co-application of DAMGO (0.1 μM) and CCh (10 μM), which acts at endogenous Gq/11-coupled muscarinic receptors to facilitate TRPC4-mediated currents triggered through stimulation of Gi/o signalling, to the TRPC4β/μ receptor co-expressing cells elicited a double rectifying current with an ‘N-shaped’ current–voltage (I–V) relationship, typical of TRPC4/C5-mediated currents (Figure 1E). Application of M084 (8 μM) immediately decreased the currents, which recovered only moderately and slowly upon washout of M084 (Figure 1E). These results confirmed that M084 is an inhibitor of the TRPC4-containing channels.

Figure 1.

M084 inhibited agonist-evoked TRPC4 activity. (A–C) Pretreatment with M084 inhibited TRPC4-mediated Ca2+ influx (A) and membrane depolarization (B, C) in a concentration-dependent manner. HEK293 cells stably co-expressing TRPC4β and μ receptors (μOR) (A, B) or 5-HT1A receptors (C) were seeded in wells of 96-well plates, loaded with Fluo-4 (A) or FMP (B, C) and fluorescence read in a microplate reader. M084 at different concentrations and buffer alone (0 μM) were added as indicated for 2.5 min before DAMGO (0.1 μM, A, B) or 5-HT (1 μM, C) was introduced. Increases in fluorescence intensity indicate intracellular Ca2+ elevation (A) or membrane depolarization (B, C). (D) Similar to (B) and (C), but cells stably co-expressed TRPC1, TRPC4β and M2 receptors. FMP II was used and stimulation was by CCh (1 μM). Because high concentrations of M084 caused a slow fluorescence increase in these cells, the fluorescence changes were normalized to the fluorescence intensity immediately preceding CCh addition (F180) instead of that in the beginning of the experiment (F0) as in all other examples. The same colour code for M084 concentrations is used for all traces shown in (A–D). (E) M084 inhibited TRPC4 currents. Representative traces showing currents at +100 and −100 mV evoked by co-application of DAMGO (0.1 μM) and CCh (10 μM) to a cell that co-expressed TRPC4β and μ receptors. M084 (8 μM) was added as indicated. Currents were elicited by 500 ms voltage ramps from +100 to −100 mV from the holding potential of 0 mV applied every 2 s. Dashed line indicates zero current. I–V relationships obtained from the voltage ramps at the time points indicated are shown below the time courses. Inset shows the structure of M084. Representative of seven experiments with similar results.

Table 2.

IC50 values (μM) for effects of 2-aminobenzimidazole compounds on TRPC3/C4/C5/C6

| TRPC4β + μ receptors (vs. DAMGO) | TRPC5 + μ receptors (vs. DAMGO) | TRPC6 + M5 receptors (vs. CCh) | TRPC3 (vs. CCh) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M084 | 10.3 ± 0.5 (n = 12) | 8.2 ± 0.7 (n = 12) | 59.6 ± 16.3 (n = 6) | 48.6 ± 9.5 (n = 6) |

| 9 | 4.1 ± 0.6 (n = 12) | 3.1 ± 0.5 (n = 12) | 57.1 ± 9.5 (n = 6) | 30.4 ± 5.3 (n = 6) |

| 13 | 5.2 ± 0.7 (n = 12) | 6.6 ± 0.9 (n = 12) | 63.8 ± 17.1 (n = 6) | 19.3 ± 0.6 (n = 6) |

| 16 | 11.0 ± 1.0 (n = 12) | 11.1 ± 1.1 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) |

| 17 | 5.5 ± 0.5 (n = 12) | 8.0 ± 1.0 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) |

| 27 | 10.2 ± 1.4 (n = 12) | 12.4 ± 1.3 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) |

| 28 | 4.3 ± 0.4 (n = 12) | 3.5 ± 0.3 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) | >100 (n = 6) |

Fluorescence membrane potential measurements on stable TRPC cell lines were performed as in Figure 3 using either FMP or FMP II. Agonist-evoked fluorescence increases (AUC) were normalized to that from the control pretreated with the buffer alone. For TRPC5, the remaining fluorescence intensity in the highest concentration of the antagonist for each set of experiments was assumed to represent no activity and used for baseline subtraction for calculating the AUC. Data points were fitted with the Hill equation to determine IC50 values, expressed as means ± SEM for the numbers of measurements indicted in parentheses.

TRPC5 is a close homologue of TRPC4 but it shows constitutive activity when expressed in HEK293 cells (Yamada et al., 2000; Zeng et al., 2004). The application of M084 to cells that stably co-expressed TRPC5 and μ receptors immediately led to decreases in fluorescence intensity in a concentration-dependent manner in the membrane potential assay (Figure 2A), indicative of blockade of TRPC5-mediated basal activity in these cells. At the highest concentration tested (22 μM), M084 also inhibited the DAMGO-induced fluorescence increase, but at lower concentrations, there was no obvious inhibitory effect. In fact, lower concentrations of M084 actually increased the DAMGO-evoked fluorescence increase (Figure 2A, see 0.8, 2.5 and 7.4 μM M084), probably because the partial inhibition of the constitutive currents produced a lower membrane potential preceding the DAMGO addition. Overall, these data suggest that M084 also inhibits TRPC5. Supporting this conclusion, M084 (8 μM) rapidly inhibited DAMGO/CCh-evoked whole-cell currents in cells that co-expressed TRPC5 and μ receptors (Figure 2B). In contrast, M084 only weakly inhibited TRPC3-mediated currents and had an even smaller inhibitory effect on TRPC6 channels, as shown by CCh-induced membrane depolarization in cells that stably expressed human TRPC3 alone or mouse TRPC6 together with the Gq/11-coupled M5 muscarinic receptor (Figure 2C, 2D). The M5 receptor was introduced because the stable monoclonal TRPC6 cell line had a poor response to CCh as compared with the wild-type HEK293 cells (data not shown). These data indicate that among the related TRPC channels, M084 is relatively selective for TRPC4 and TRPC5. M084 exhibited a very good solubility in aqueous buffers and had a relatively quick inhibitory action on these channels. However, the potency of M084 was low, with IC50 values of 10.3 ± 0.5 and 8.2 ± 0.7 μM for TRPC4 and TRPC5, respectively, as determined by the FMP assay using DAMGO to stimulate Gi/o via the co-expressed μ receptor (Table 2). In addition, M084 displayed a weak but clear inhibitory effect on TRPC3, with an IC50 of ∼50 μM (Table 2). Therefore, we searched and synthesized structural analogues of M084 in order to identify more potent and selective inhibitors for TRPC4 and/or TRPC5.

Figure 2.

M084 inhibited TRPC5 activity and exhibited minimal effects on TRPC3 and TRPC6. (A) M084 inhibited basal activity of TRPC5. Similar to Figure 1B, but the fluorescence membrane potential assay was performed using cells that stably co-expressed TRPC5 and μ receptors. The addition of M084 reduced the basal fluorescence in a concentration-dependent manner. (B) M084 inhibited TRPC5 currents. Similar to Figure 1E, but for a cell that co-expressed TRPC5 and μ receptors and voltage ramps were applied every 1 s. Currents were induced by the co-application of DAMGO (0.1 μM) and CCh (10 μM). Addition of M084 (8 μM) in the presence of DAMGO and CCh immediately suppressed the currents, which partially recovered upon washout of M084. I–V relationships obtained from the voltage ramps at the time points indicated are shown below the time courses. Representative of five experiments with similar results. (C and D) M084 weakly inhibited TRPC3 (C) and TRPC6 (D). Similar to Figure 1B, but the fluorescence membrane potential assay was performed using cells that stably expressed human TRPC3 (C) or co-expressed mouse TRPC6 and M5 muscarinic receptors (M5R, D). The addition of M084 caused little fluorescence change and CCh-evoked membrane depolarization was only weakly inhibited by M084. The concentrations of CCh used were 100 μM (C) and 0.3 μM (D).

Structure and activity relationship (SAR) of M084

We tested a total of 28 structural analogues of M084, obtained either from commercial sources or through new synthesis (Table 1), against the TRPC4β/μ receptor expressing cells using the FMP assay. The results revealed that the amino group linked to position 2 of the benzimidazole backbone was an absolute requirement for activity. This could be either a primary (M084 and compound 27) or secondary amine in the form of a ring structure either as a piperidine (compounds 9, 13, 16 and 28) or a pyrrolidine (17). Therefore, the 2-aminobenzimidazol skeleton forms the basic scaffold required for inhibiting TRPC4. Generally, a carbonyl functional group and π system were not well tolerated at the amino position of benzimidazole, as indicated by, for example, acylation (4 and 10), aromatic substitution (7, 18, 25 and 29) or addition of alcohol or ether (3 and 22) or the substituted morpholine (15); neither was an additional amine, such as the aliphatic heteroalkane chains on the amino position (23 and 24) and the substituted piperazine (11 and 12), tolerated. Dialkylation of the amine (20, 21 and 25) also resulted in the loss of the inhibitory effect on TRPC4. Pyrrolidine and methylpiperidine at position 2 of the benzimidazole backbone appeared to work slightly better than the original n-butylamine, suggesting that the n-butyl chain might loop around to interact with the channel. This is supported by the inhibitory action of compound (cpd) 27, in which the primary amine is sterically hindered. However, the piperidine has to be linked with the benzimidazole backbone via the amino group (16) instead of an alkyl group (14), further emphasizing that 2-aminobenzimidazole is an essential scaffold. The methyl group of the methylpiperidine could be added at either the fourth (9 and 13) or the second position (28) of the piperidine. Modifications at position 1 of the benzimidazole backbone tended to reduce the inhibitory effect on TRPC4 (e.g. cpds 8 and 19), while substitution of the proton with Cl− at position 5 of the benzimidazole backbone was well tolerated (compare cpds 9 and 13).

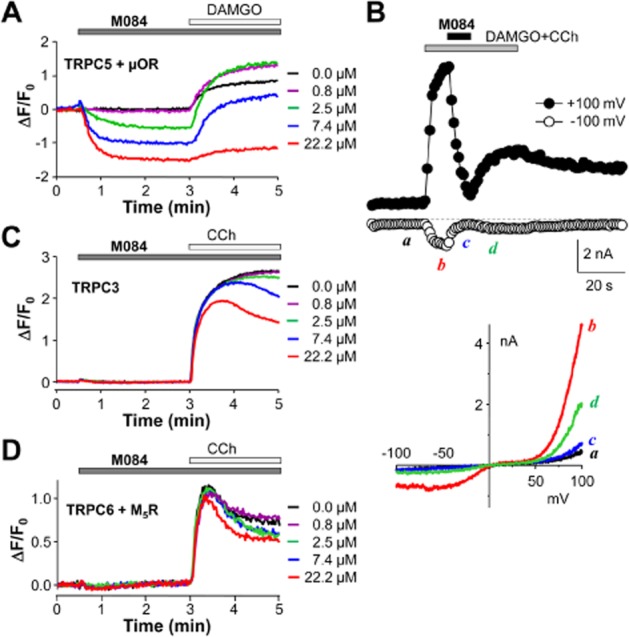

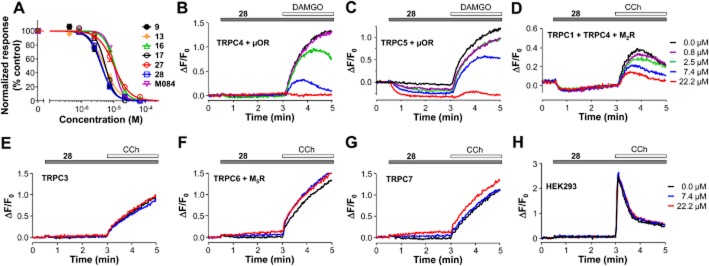

We determined the IC50 values for cpds 9, 13, 16, 17, 27 and 28 on DAMGO-induced depolarization in cells that co-expressed TRPC4β and μ receptors (Figure 3A and Table 2). Cpds 9, 13, 17 and 28 showed improved potency over the original compound, with about a 50% decrease in IC50 values. A similar improvement was also found for cpds 9, 13 and 28 against TRPC5 activated by DAMGO through the co-expressed μ receptors (Table 2). However, both cpd 9 and cpd 13 still showed weak inhibition of TRPC3 and slight inhibition of TRPC6 channels at high concentrations (Table 2). In contrast, cpds 16, 17, 27 and 28 did not inhibit TRPC3 or TRPC6 (Table 2). Cpd 28 also inhibited CCh-evoked membrane depolarization in cells that co-expressed TRPC1, TRPC4β and M2 receptors (Figure 3D), with an estimated IC50 of 11.0 ± 1.7 μM (n = 6). Although the IC50 value was not an improvement on that obtained with M084, the analogue cpd 28 did not induce the slow depolarization seen with the high concentrations of M084 on the TRPC1/C4 heteromeric channel (compare 22.2 μM traces in Figures 1D and 3D). In addition, cpd 28 did not affect CCh-induced Ca2+ responses in wild-type HEK293 cells (Figure 3H) and it did not inhibit CCh-evoked membrane depolarization mediated through TRPC7 (Figure 3G). Example traces for the effects of cpd 28 on TRPC3, C4, C1/C4, C5, C6 and C7, as measured by agonist-evoked membrane depolarization using the FMP II are shown in Figure 3B–G. Note that FMP II exhibited slower kinetics and gave smaller fold fluorescence increases in response to TRPC channel-mediated membrane depolarization than the original FMP dye; however, it also yielded a smaller decrease in fluorescence upon inhibition of the constitutive activity of TRPC5 in response to application of the antagonist (compare Figures 2A and 3C).

Figure 3.

Structural analogues of M084 inhibited TRPC4 and TRPC5. (A) Concentration-dependence of the inhibitory effects of M084 and its structural analogues on DAMGO-evoked membrane depolarization in the stable HKE293 cell line that co-expressed TRPC4β and μ receptors. Fluorescence membrane potential assays were performed as in Figure 1B using the aminobenzimidazole compounds as indicated. DAMGO (0.1 μM)-evoked fluorescence increases (AUC) were normalized to that of the control pretreated with the buffer alone. Data are means ± SEM for n = 12 measurements for all compounds. Data points were fitted with the Hill equation. (B–G) Representative traces of the fluorescence membrane potential assays using FMP II performed on cells that expressed TRPC4β and μ receptors (B), TRPC5 and μ receptors (C), TRPC1, TRPC4β and M2 receptors (D), TRPC3 only (E), TRPC6 and M5 receptors (F) or TRPC7 only (G). Compound 28 was applied as indicated and the respective receptor agonist was added 2.5 min later. Receptor agonist concentrations used were: DAMGO, 0.1 μM (B and C), CCh, 0.3 μM (F), 1 μM (D) and 100 μM (E, G). Note the concentration-dependent suppression of DAMGO-evoked depolarization for TRPC4β (B), TRPC5 (C) and TRPC1/C4 (D) by compound 28, as well as the decrease in basal fluorescence for TRPC5-expressing cells (C). The compound did not inhibit CCh-evoked responses for TRPC3 (E), TRPC6 (F) and TRPC7 (G). (H) Compound 28 did not affect CCh-evoked Ca2+ responses in wild -type HEK293 cells. Untransfected cells were seeded in wells of a 96-well plate, loaded with Fluo-4 and fluorescence read in a microplate reader. Compound 28 or buffer alone (0 μM) was applied as indicated. The addition of CCh (100 μM) immediately increased fluorescence, indicating a rise in [Ca2+]i, which was unaffected by the pretreatment with the compound. The same colour code for compound 28 concentrations is used for all traces shown in (B–H).

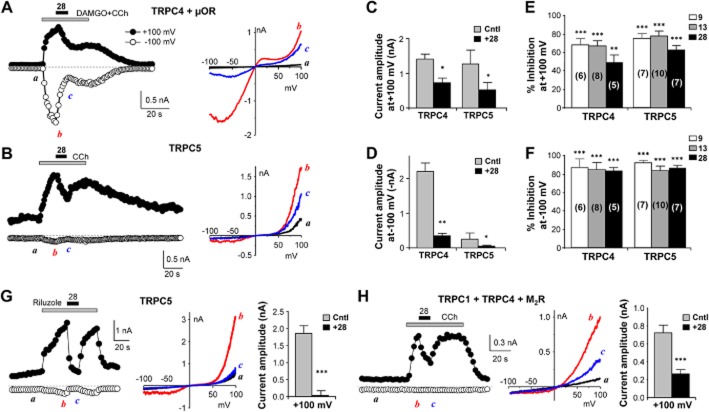

In whole-cell recordings, acute application of cpd 28 (10 μM) led to inhibition of TRPC4β-mediated currents activated by co-stimulation of Gi/o and Gq/11 pathways with DAMGO (0.1 μM) plus CCh (30 μM) in cells that co-expressed TRPC4β and μ receptors (Figure 4A). It also inhibited TRPC5 currents activated by CCh (100 μM) via endogenous muscarinic receptors in the TRPC5-expressing cells (Figure 4B). Note the much smaller inward currents at negative potentials for TRPC5 in the absence of Gi/o stimulation. For both TRPC4 and TRPC5, the inhibition by cpd 28 was more pronounced at negative than at positive potentials (Figure 4C–F). Quantification of the degree of inhibition by cpd 28 at −100 mV and +100 mV revealed 83.4 ± 4.1 and 48.9 ± 8.6% reduction of TRPC4 and 86.8 ± 3.5 and 62.7 ± 4.8% reduction of TRPC5 currents respectively (Figure 4E, 4F). A similar inhibition of TRPC4 and TRPC5 currents was also observed with the acute application of cpds 9 and 13 (Figure 4E, 4F). Recently, riluzole was shown to activate TRPC5 independently of receptor/PLC activation (Richter et al., 2014a). Application of cpd 28 (10 μM) also caused instantaneous inhibition of riluzole-evoked TRPC5-mediated currents (Figure 4G). In addition, in the cells co-expressing TRPC1/C4/M2 receptors, cpd 28 (10 μM) also strongly depressed the current evoked by CCh (Figure 4H).

Figure 4.

M084 analogues inhibited agonist-evoked TRPC4 and TRPC5 currents. (A) Compound 28 inhibited TRPC4 currents. Similar to Figure 1E, but the voltage ramp was 200 ms and repeated every 1 s. Currents were elicited by the co-application of DAMGO (0.1 μM) and CCh (30 μM) in a cell that co-expressed TRPC4β and μ receptors. Compound 28 (10 μM) was applied as indicated after the currents had developed and this led to immediate decreases of currents at both positive and negative potentials. I–V relationships obtained from the voltage ramps at the time points indicated are shown to the right. (B) Similar to (A), but for a cell that expressed only TRPC5. The currents were elicited by 100 μM CCh. Compound 28 decreased the CCh-evoked currents. (C and D) Current amplitudes immediately before (control, Cntl) and at the end of the application of compound 28 (+28) for TRPC4 and TRPC5 at +100 mV (C) and −100 mV (D). Data are means ± SEM for five TRPC4-expressing and seven TRPC5-expressing cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus control (Cntl) by paired t-test. (E and F) % inhibition of agonist-evoked currents by compounds 9, 13 and 28 for TRPC4 and TRPC5 under the same protocol as shown in (A and B) at +100 mV (E) and −100 mV (F). Data (means ± SEM) for compound 28 were derived from (C and D). Data for compounds 9 and 13 were from separate experiments using cells that co-expressed μ receptors with either TRPC4β or TRPC5. Currents were elicited by co-stimulation with DAMGO (0.1 μM) and CCh (10 μM). Numbers of cells are indicated in parentheses. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one sample t-tests comparing with 100% (no inhibition). (G) Compound 28 inhibited riluzole-induced TRPC5 currents. Similar to (B), but riluzole (50 μM) was applied to elicit TRPC5 currents. Summary data (means ± SEM, n = 6) for current amplitudes immediately before (Cntl) and at the end of compound 28 (10 μM) application (+28) are shown on the right. ***P < 0.001 versus Cntl by paired t-test. (H) Similar to (G), but the cells expressed TRPC1, TRPC4β and M2 receptors, and currents were evoked by CCh (10 μM). Summary data also represent n = 6 cells.

Pre-exposure of the cells to cpd 28 for ∼30 s also strongly inhibited the activation of TRPC4β induced by co-stimulation with DAMGO and CCh by ∼80 and 98% at +100 and −100 mV respectively (Figure 5A–C). Similarly, pretreatment with cpd 28 also blocked the CCh-evoked TRPC5 currents by ∼85 and 90% at +100 and −100 mV respectively (Figure 5D–F). Noticeably, bath application of cpd 28 also reduced the constitutive outward current in TRPC5-expressing cells (Figure 5E), consistent with the observed fluorescence membrane potential measurements (Figure 3C). By contrast, pretreatment with cpd 28 did not significantly alter the CCh-evoked TRPC6 currents in cells that co-expressed TRPC6 and M5 receptors (Figure 5G–I), confirming that it lacks an effect on TRPC6. Therefore, the results from the electrophysiological experiments corroborate the conclusions from the fluorescence membrane potential assay that cpds 9, 13 and 28 are TRPC4/C5 blockers and cpd 28 has an improved selectivity over M084 on the TRPC4/C5 subgroup of TRPC channels. The fast onset of action of these drugs makes them ideally suited for electrophysiological experiments to isolate currents mediated by native TRPC4/C5 channels.

Figure 5.

Pretreatment with compound 28 suppressed activation of TRPC4 and TRPC5 but not TRPC6 induced by agonist stimulation. (A–C) Currents evoked by DAMGO (0.1 μM) and CCh (30 μM) in cells that co-expressed TRPC4β and μ receptors without (A) or with (B) pretreatment with compound 28 (10 μM) for ∼30 s. Compound 28 was also present throughout the exposure to the agonists. Shown are time courses of currents at +100 and −100 mV (left) and I–V relationships obtained by the voltage ramp protocol (same as Figure 4A) before (black trace) and during (red trace) agonist stimulation (right). Summary data (means ± SEM) for agonist-induced peak current amplitudes (absolute values) at +100 and −100 mV are shown in (C); n = 7 for control, n = 5 for +28. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001 versus control by unpaired t-test. (D–F) Similar to A–C, but the cells expressed TRPC5 and the agonist was CCh (100 μM). Note the decrease in basal current at +100 mV upon application of compound 28 (E). The I–V curve for basal current before addition of compound 28 (grey trace) is indicated by the solid arrow, while that for current in the presence of compound 28 but before CCh (black trace) is indicated by the open arrowhead. For summary in (F), n = 7 for control, n = 6 for +28. *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001 versus control by unpaired t-test. (G–I) Similar to (A–C), but the cells co-expressed TRPC6 and M5 receptors and the agonist was CCh (3 μM). For summary in (I), n = 6 for control, n = 6 for +28.

M084 and its analogues have minimal effect on related channels

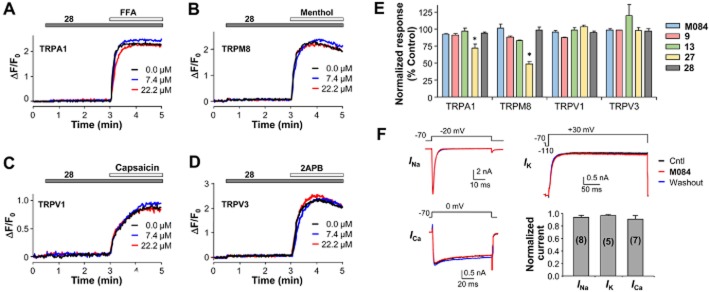

Using stable cell lines that expressed TRPA1, TRPM8, TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels, we examined the effects of M084 and a number of its analogues, cpds 9, 13, 27 and 28, on these distantly related TRP channels. The cells were loaded with Fluo-4 and then stimulated with the respective agonist for each channel, with changes in [Ca2+]i monitored by a fluorescence plate reader. As exemplified in Figure 6A–D for cpd 28 and summarized in Figure 6E for all five compounds, M084 and cpds 9, 13 and 28 showed neither agonistic nor antagonistic effects on the TRP channels tested. Cpd 27 was ineffective on TRPV1 and TRPV3, but moderately inhibited TRPA1 and TRPM8. The inhibitory effect on TRPM8 was not very surprising as a number of benzimidazole-containing compounds have been shown to be potent antagonists of TRPM8 (Parks et al., 2011; Calvo et al., 2012). Furthermore, using freshly isolated mouse DRG neurons, we recorded native voltage-gated Na+, K+ and Ca2+ currents and found that M084 had no effect on these channels (Figure 6F). These data further confirm the selectivity of the M084 series of compounds on TRPC, especially TRPC4/C5 channels.

Figure 6.

M084 and its analogues did not inhibit other channels. (A–D) Compound 28 had no effect on TRPA1, TRPM8, TRPV1 and TRPV3. HEK293 cells stably expressing human TRPA1 (A), mouse TRPM8 (B), mouse TRPV3 (D) or transiently expressing rat TRPV1 (C) were seeded in wells of 96-well plates, loaded with Fluo-4, and the fluorescence read in a microplate reader for assessing changes in [Ca2+]i. Compound 28 (7.4 and 22.2 μM) or buffer alone (0 μM) was added as indicated for 2.5 min before the application of the corresponding agonist: FFA (100 μM, A), menthol (200 μM, B), capsaicin (1 μM, C), 2APB (200 μM, D). (E) Summary (means ± SEM) for agonist-induced Fluo-4 fluorescence changes in cells that expressed TRPA1, TRPM8, TRPV1 and TRPV3 in the presence of 22.2 μM M084 and its analogues, compounds 9, 13, 27 and 28. Agonists and their concentrations are the same as shown in (A–D). Integrated fluorescence changes (AUC) were normalized to that in the absence of the 2-aminobenzimidazole drug (control); n = 6 measurements for each. Only compound 27 showed moderate inhibition of TRPA1 and TRPM8. *P < 0.05 versus corresponding control. (F) Representative current traces of voltage-gated Na+, K+ and Ca2+ channels (INa, IK, ICa) before (black traces) and during (red traces) the application of M084 (30 μM) and after its washout (blue traces), recorded from dissociated mouse DRG neurons. Voltage protocols are shown above the traces. Current traces are overlaid for comparison, with the one during M084 application placed in the front. Histogram shows means ± SEM of current densities, at step voltages that yielded the maximal currents, in the presence of M084 normalized to the average values before M084 and after washout to correct for rundown in some cells. Number of cells tested are shown in parentheses.

M084 and its analogues inhibit native TRPC4-like activity in lateral septal neurons

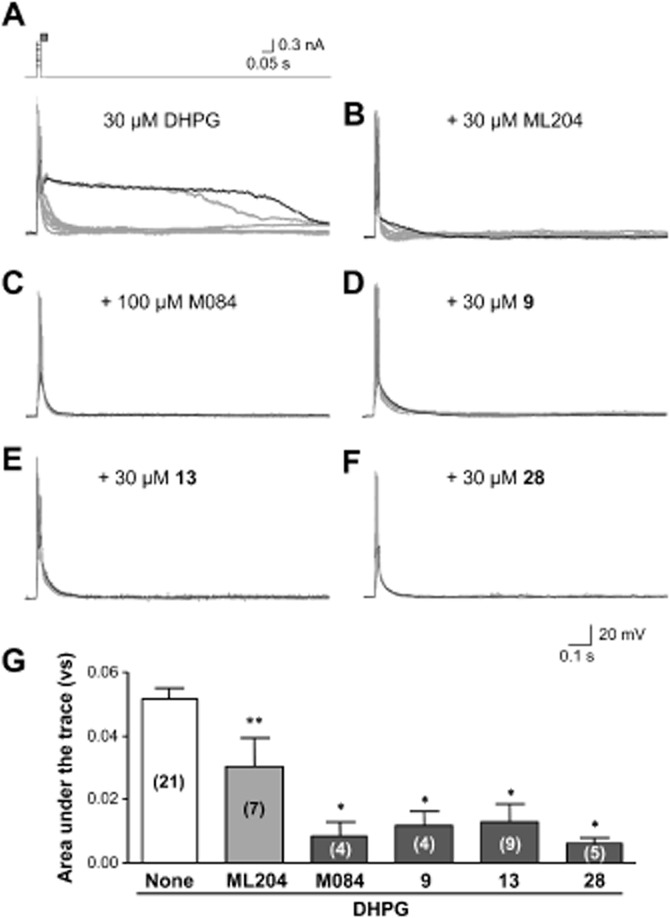

We and others have shown that TRPC4-containing channels mediate a plateau potential response when stimulated by the agonist of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors, (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) or (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid, in rodent lateral septal neurons (Phelan et al., 2012; Tian et al., 2014). This response was greatly facilitated by the injection of a positive current while DHPG (30 μM) was applied (Figure 7A). While co-application of the previously reported TRPC4/C5 blocker, ML204 (30 μM), significantly suppressed the DHPG-induced plateau depolarization (Figure 7B, 7G), the inhibition was incomplete, probably because of the slow mechanism of action and the relatively poor aqueous stability of the compound. In contrast, when co-applied without pre-incubation, M084 (100 μM) and its analogues, cpds 9, 13 and 28 (all at 30 μM), inhibited the DHPG-induced plateau depolarization by ∼80% (Figure 7C–G), demonstrating the effectiveness of these blockers in acute suppression of native TRPC4-containing channels, in agreement with their actions on heterologously expressed channels.

Figure 7.

M084 and analogues inhibited TRPC4-mediated plateau potentials in lateral septal neurons. (A) Plateau potentials evoked by pressure ejection of DHPG (30 μM) and concomitant current injection in lateral septal neurons. The lateral septal neuron in mouse brain slice was held at −80 mV under whole-cell current clamp mode. A series of nine current injections (20 ms, 0.2–1 nA, with a 0.1-nA increment and 1.3 s intervals) were applied immediately before initiation of DHPG ejection (5–20 psi, 30 ms; current protocol and time of DHPG application, indicated by the grey bar, are shown in upper panel). Traces from all nine sweeps are overlaid, with the one that yielded the maximal depolarization response shown in black (lower panel). (B–F) Similar to A, but DHPG was co-ejected with ML204 (B), M084 (C), compound 9 (D), 13 (E) or 28 (F). (G) Summary of maximal depolarization response, as determined by the area under the trace from the sweep with the longest depolarization period. Data are means ± SEM for the numbers of neurons indicated in parentheses. All drugs were used at 30 μM except for M084, which was used at 100 μM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with DHPG alone.

Discussion and conclusions

Small molecular probes for TRPCs are of critical value for analysing physiological and pathophysiological functions of these channels. Because of the lack of specific inhibitors, the testing of native TRPC channel functions has been limited to the use of non-specific blockers, such as SKF96365 and 2APB and occasionally FFA (Merritt et al., 1990; Inoue et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2004). However, these compounds have low potency on TRPC channels and are either equally effective or better antagonists of other non-TRPC targets (Merritt et al., 1990; Singh et al., 2010). Therefore, several groups have tried to identify novel small molecular probes for TRPC channels (Kiyonaka et al., 2009; Majeed et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2011a; Miehe et al., 2012; Schleifer et al., 2012; Urban et al., 2012; Washburn et al., 2013; Richter et al., 2014a, b). Previously, we have reported the characterization of ML204 as a selective inhibitor of TRPC4/C5 (Miller et al., 2011a). Furthermore, others have found ML204 to be useful for demonstrating the involvement of native TRPC4 and/or TRPC5 channels in visceral pain (Westlund et al., 2014), the disruption of the kidney filtration barrier (Schaldecker et al., 2013) and in the regulation of neuronal excitability (Zhang et al., 2013; Kolaj et al., 2014).

The M084 series of compounds reported here represents a different hit from the same screen that identified ML204, in which a cell-based assay was used to monitor the DAMGO-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i mediated by mouse TRPC4β activated by the co-expressed Gi/o-coupled μ receptors (Miller et al., 2011a, b). The primary hit, M084, contains a 2-aminobenzimidazole scaffold. Through SAR studies, we have shown that the amine at the second position of benzimidazole is essential for the inhibitory action on TRPC4, indicating that indeed the basic structural backbone for this series is 2-aminobenzimidazole. This differs from the series of benzimidazole-containing antagonists for TRPM8, in which an amino group is typically not present at such a position (Parks et al., 2011; Calvo et al., 2012). However, just the 2-aminobenzimidazole backbone itself (cpd 2) exhibited no activity on TRPC4. The addition of a four-carbon alkyl radical (n-butyl) or the joining of the amine by four or five carbons to form pyrrolidine or piperidine, respectively, was necessary to confer the inhibition on TRPC4. This suggests that a ring-shaped structure around the amine may be important for binding to and/or the inhibitory action on the TRPC channel. It is possible that the n-butyl chain of M084 also loops around to form a pseudo ‘ring-shaped’ structure when binding to the channel. This explains the lower apparent affinity of M084, based on the IC50 value, than its analogues with the pyrrolidine or piperidine substitution. Yet, we found that methylpiperidine worked better than piperidine in this position. Although the addition of a methyl group at either the second or the fourth position of the piperidine worked equally well on TRPC4 and C5, the methyl group at the fourth position seems to confer some activity, albeit weak, on TRPC3 and TRPC6. Thus, cpds without a methyl at the fourth position, cpds 16, 17 and 28, did not show any appreciable inhibition of TRPC3 and TRPC6 at 22 μM. Also interesting is that although the substitution of the n-butylamine with a sterically hindered primary amine (cpd 27) was allowed, other substitutions, for example, aromatic structures, acylation, dialkylation and introduction of alcohol, ether or additional amine, all resulted in the loss of inhibitory action on TRPC4. Therefore, a heterocyclic aliphatic amine attached to the second position of a benzimidazol backbone forms the basic structure for binding to and/or inhibiting TRPC4/C5 channels. The requirement for a heterocyclic aliphatic amine is similar to the SAR profile of ML204 (Miller et al., 2011a), suggesting that the two series of compounds may share a similar mechanism of action. Therefore, even though the original hits ML204 and M084 did not look alike, their inhibitory action on TRPC channels probably involves pyrrolidine- or piperidine-like structures with a methyl group allowed at certain positions. The quinoline (ML204) and benzimidazol (M084) backbones are probably not essential for binding to the channels and the inhibitory action, but may influence the compound's stability and its kinetics for interaction with the channels.

The M084 series was found to inhibit homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5 as well as heteromeric TRPC1/C4 channels in both the fluorescence membrane potential assay and whole-cell voltage clamp recordings. The inhibition was not dependent on the receptor type employed to trigger channel activation. Importantly, the activation of TRPC4 or TRPC5 by the Gi/o-coupled μ receptor or 5-HT1A receptor, and also that of TRPC5 by the endogenous Gq/11-coupled muscarinic receptors, as well as its direct agonist, riluzole, were all inhibited by M084 and its analogues. Furthermore, the constitutive activity of TRPC5 was reduced by these compounds in both the fluorescence membrane potential and electrophysiological assays. These, together with the finding that only some, but not all of these inhibitors weakly blocked Gq/11-mediated activation of TRPC3 and TRPC6, suggest a direct inhibitory effect of the aminobenzimidazole compounds on TRPC4/C5 channels.

We found that M084 and its analogues were relatively selective for TRPC, especially TRPC4/C5, channels. At the highest concentration tested (22 μM), these compounds did not affect the functions of TRPA1, TRPM8, TRPV1 and TRPV3 heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells in Ca2+ influx assays. In whole-cell recordings of mouse DRG neurons, M084 did not significantly alter the current density of voltage-gated Na+, K+ or Ca2+ channels. Importantly, unlike ML204 (Miller et al., 2011a), cpd 28 did not affect intracellular Ca2+ release induced through activation of endogenous muscarinic receptors. Among the analogues analysed here, cpd 28 yielded lowest IC50 values against TRPC4 and TRPC5 and showed no inhibitory effect on TRPC3/C6/C7, indicating that it is an excellent selective inhibitor of TRPC4 and TRPC5. In electrophysiological recordings, all of the aminobenzimidazole compounds produced an immediate inhibition of TRPC4 and TRPC5 currents following bath application, indicating a direct and fast action by the compounds. This feature is particularly important in electrophysiological studies to determine the contribution of native TRPC4/C5 channels. Indeed, recordings of DHPG-induced plateau potential in mouse lateral septal neurons demonstrated the effectiveness of M084 and its analogues, cpds 9, 13 and 28, at inhibiting native TRPC4-containing channels. Under the conditions used for these experiments, the M084 series exhibited a better inhibitory effect than ML204, suggesting improved stability and/or action kinetics. Curiously, however, we have found that cpds 16 and 28 blocked butyrylcholinesterase in a cell-free assay at similar to or slightly better potency than their inhibition of TRPC4 or TRPC5 functions (Zhu et al., 2013). A recent study also showed that ML204 inhibited acetylcholinesterase in the cell-free assay with a similar potency to its inhibition of TRPC4 (Antolín and Mestres, 2015). Although the cholinesterases are not known to regulate TRPC channels, caution should be taken when using these compounds to study native TRPC4/C5 function in the presence of cholinesterase activities. Since cpd 27 exhibited no effect on cholinesterases (Zhu et al., 2013), it may be used as an alternative or an additional control to confirm the involvement of TRPC4/C5 channels. However, other off-target effects of cpd 27, for example, TRPA1 and TRPM8, should also be carefully evaluated before a conclusion is reached. Further improvements in the aminobenzimidazoles may yield compounds with a higher potency and better selectivity against TRPC4 and/or TRPC5.

Pharmacological tools are essential for revealing the function of TRP channels. The compounds currently available tend to broadly affect voltage-gated channels, intracellular Ca2+ release channels, chloride channels and/or multiple types of TRP channels from several subfamilies (Merritt et al., 1990; Hofmann et al., 1999; Inoue et al., 2001). Therefore, the identification of isoform-specific probes for TRP channels is important for advancing the studies and understanding of these channels. Because TRPC4/C5 channels are involved in various diseases (von Spiczak et al., 2010; Jung et al., 2011; Schaldecker et al., 2013), the pharmacological tools may also have therapeutic potential. The specific TRPC4/C5 inhibitors reported here should be excellent tools for physiological and pathological studies defining the functional significance of TRPC4/C5-containing channels and may facilitate the development of therapeutics targeting TRPC channels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Corey Hopkins for the initial evaluation of the lead compounds and suggestions on structural analogues. This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NS056942, NS092377 and DK081654 to M. X. Z., U54 MH084691 to M. L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81373254 and 21390402 to X. Hong), Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan Province (2012FB181 and 2014BC011 to H. R. L.), postdoctoral fellowship from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (to Y. L.), predoctoral fellowship from American Heart Association-Southwest Affiliate (to D. P. T.), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (to C. Q.) and Innovation Seed Fund of Wuhan University School of Medicine (to X. Hong).

Glossary

- 2-APB

2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- CCh

carbachol

- cpd

compound

- DHPG

(S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- FFA

flufenamic acid

- FMP

FLIPR membrane potential dye

- FMP II

FLIPR membrane potential dye II

- I–V

current–voltage

- MLSMR

Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository

- SAR

structure and activity relationship

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- TRPC

TRP canonical

Author contributions

O. M., M. L., X. Hong, H. R. L. and M. X. Z. designed the research; Y. Z., Y. L., C. Q., M. M., J. T., D. P. T., J. Z., Z. D., X. Hu, M. W. performed experiments; Y. Z., Y. L., M. M., J. T., M. W., O. M., X. Hong, M. X. Z., H. R. L. performed data analyses; Y. Z., Y. L., M. W., O. M., M. L., X. Hong, H. R. L. and M. X. Z. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have not any conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013b;170:1607–1651. doi: 10.1111/bph.12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antolín AA, Mestres J. Distant polypharmacology among MLP chemical probes. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:395–400. doi: 10.1021/cb500393m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo RR, Meegalla SK, Parks DJ, Parsons WH, Ballentine SK, Lubin ML, et al. Discovery of vinylcycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazole TRPM8 antagonists effective in the treatment of cold allodynia. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1903–1907. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder P, Poteser M, Romanin C, Groschner K. Na+ entry and modulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchange as a key mechanism of TRPC signaling. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:99–104. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature. 1999;397:259–263. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Tian J, Zhu Y, Wang C, Xiao R, Herz JM, et al. Activation of TRPA1 channels by fenamate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Pflugers Arch. 2009;459:579–592. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0749-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HZ, Gu Q, Wang C, Colton CK, Tang J, Kinoshita-Kawada M, et al. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate is a common activator of TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPV3. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35741–35748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Hara Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, et al. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular alpha1-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res. 2001;88:325–332. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JP, Lee KP, Park EJ, Sung TS, Kim BJ, Jeon JH, et al. The specific activation of TRPC4 by Gi protein subtype. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JP, Hong C, Park EJ, Jeon JH, Cho NH, Kim IG, et al. Selective Gαi subunits as novel direct activators of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC)4 and TRPC5 channels. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17029–17039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.326553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C, Gené GG, Tomás M, Plata C, Selent J, Pastor M, et al. A gain-of-function SNP in TRPC4 cation channel protects against myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:465–471. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kwak M, Jeon JP, Myeong J, Wie J, Hong C, et al. Isoform- and receptor-specific channel property of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC)1/4 channels. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:491–504. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1332-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyonaka S, Kato K, Nishida M, Mio K, Numaga T, Sawaguchi Y, et al. Selective and direct inhibition of TRPC3 channels underlies biological activities of a pyrazole compound. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5400–5405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808793106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaj M, Zhang L, Renaud LP. Novel coupling between TRPC-like and KNa channels modulates low threshold spike-induced afterpotentials in rat thalamic midline neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2014;86:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed Y, Amer MS, Agarwal AK, McKeown L, Porter KE, O'Regan DJ, et al. Stereo-selective inhibition of transient receptor potential TRPC5 cation channels by neuroactive steroids. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1509–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt JE, Armstrong WP, Benham CD, Hallam TJ, Jacob R, Jaxa-Chamiec A, et al. SK&F 96365, a novel inhibitor of receptor-mediated calcium entry. Biochem J. 1990;271:515–522. doi: 10.1042/bj2710515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miehe S, Crause P, Schmidt T, Löhn M, Kleemann HW, Licher T, et al. Inhibition of diacylglycerol-sensitive TRPC channels by synthetic and natural steroids. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Shi J, Zhu Y, Kustov M, Tian JB, Stevens A, et al. Identification of ML204, a novel potent antagonist that selectively modulates native TRPC4/C5 ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2011a;286:33436–33446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Wu M, Xu J, Weaver D, Li M, Zhu MX. High-throughput screening of TRPC channel ligands using cell-based assays. In: Zhu MX, editor. TRP Channels. Boca Raton, FL: CRC PressLlc; 2011b. In: (ed.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V. The TRP channels, a remarkably functional family. Cell. 2002;108:595–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch T, Freichel M, Flockerzi V, Pape HC. Contribution of transient receptor potential channels to the control of GABA release from dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16065–16070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535311100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuguro K, Tang J, Tang Y, Xiao R, Freichel M, Tsvilovskyy V, et al. Isoform-specific inhibition of TRPC4 channel by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10026–10036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707306200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks DJ, Parsons WH, Colburn RW, Meegalla SK, Ballentine SK, Illig CR, et al. Design and optimization of benzimidazole-containing transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) antagonists. J Med Chem. 2011;54:233–247. doi: 10.1021/jm101075v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan KD, Mock MM, Kretz O, Shwe UT, Kozhemyakin M, Greenfield LJ, et al. Heteromeric canonical transient receptor potential 1 and 4 channels play a critical role in epileptiform burst firing and seizure-induced neurodegeneration. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:384–392. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.075341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TD, Schaefer M. TRPC4 and TRPC5: receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channels. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A, Li Y, Moon J, Kim KS, Smith KS, Rudolph U, et al. Essential role for TRPC5 in amygdala function and fear-related behavior. Cell. 2009;137:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A, Li Y, Tsvetkov E, Gapon S, Yao GL, Smith KS, et al. Decreased anxiety-like behavior and Gαq/11-dependent responses in the amygdala of mice lacking TRPC4 channels. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3653–3667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2274-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JM, Schaefer M, Hill K. Riluzole activates TRPC5 channels independently of PLC activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2014a;171:158–170. doi: 10.1111/bph.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JM, Schaefer M, Hill K. Clemizole hydrochloride is a novel and potent inhibitor of transient receptor potential channel TRPC5. Mol Pharmacol. 2014b;86:514–521. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.093229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaldecker T, Kim S, Tarabanis C, Tian D, Hakroush S, Castonguay P, et al. Inhibition of the TRPC5 ion channel protects the kidney filter. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5298–5309. doi: 10.1172/JCI71165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer H, Doleschal B, Lichtenegger M, Oppenrieder R, Derler I, Frischauf I, et al. Novel pyrazole compounds for pharmacological discrimination between receptor-operated and store-operated Ca2+ entry pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:1712–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Hildebrand ME, Garcia E, Snutch TP. The transient receptor potential channel antagonist SKF96365 is a potent blocker of low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1464–1475. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Spiczak S, Muhle H, Helbig I, de Kovel CG, Hampe J, Gaus V, et al. Association study of TRPC4 as a candidate gene for generalized epilepsy with photosensitivity. Neuromolecular Med. 2010;12:292–299. doi: 10.1007/s12017-010-8122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Thakur DP, Lu Y, Zhu Y, Freichel M, Flockerzi V, et al. Dual depolarization responses generated within the same lateral septal neurons by TRPC4-containing channels. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:1301–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruppathi C, Freichel M, Vogel SM, Paria BC, Mehta D, Flockerzi V, et al. Impairment of store-operated Ca2+ entry in TRPC4−− mice interferes with increase in lung microvascular permeability. Circ Res. 2002;91:70–76. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000023391.40106.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebak M, Lemonnier L, Smyth JT, Vazquez G, Putney JW. Phospholipase C-coupled receptors and activation of TRPC channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007;179:593–614. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvilovskyy VV, Zholos AV, Aberle T, Philipp SE, Dietrich A, Zhu MX, et al. Deletion of TRPC4 and TRPC6 in mice impairs smooth muscle contraction and intestinal motility in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1415–1424. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban N, Hill K, Wang L, Kuebler WM, Schaefer M. Novel pharmacological TRPC inhibitors block hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction. Cell Calcium. 2012;51:194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn DG, Holt DA, Dodson J, McAtee JJ, Terrell LR, Barton L, et al. The discovery of potent blockers of the canonical transient receptor channels, TRPC3 and TRPC6, based on an anilino-thiazole pharmacophore. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:4979–4984. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DG, Morielli AD, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ Res. 2002;90:248–250. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.105662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund KN, Zhang LP, Ma F, Nesemeier R, Ruiz JC, Ostertag EM, et al. A rat knockout model implicates TRPC4 in visceral pain sensation. Neuroscience. 2014;262:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, Farrington MK, Creazzo T, Hawkins AF, et al. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science. 2005;308:1801–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1106215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Wakamori M, Hara Y, Takahashi Y, Konishi K, Imoto K, et al. Spontaneous single-channel activity of neuronal TRP5 channel recombinantly expressed in HEK293 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2000;285:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F, Xu SZ, Jackson PK, McHugh D, Kumar B, Fountain SJ, et al. Human TRPC5 channel activated by a multiplicity of signals in a single cell. J Physiol. 2004;559:739–750. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Kolaj M, Renaud LP. GIRK-like and TRPC-like conductances mediate thyrotropin-releasing hormone-induced increases in excitability in thalamic paraventricular nucleus neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2013;72:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Wu CF, Li X, Wu GS, Xie S, Hu QN, et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular modeling of substituted 2-aminobenzimidazoles as novel inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:4218–4224. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]