Abstract

Spirituality and gratitude are associated with wellbeing. Few if any studies have examined the role of gratitude in heart failure (HF) patients or whether it is a mechanism through which spirituality may exert its beneficial effects on physical and mental health in this clinical population. This study examined associations bet ween gratitude, spiritual wellbeing, sleep, mood, fatigue, cardiac-specific self-efficacy, and inflammation in 186 men and women with Stage B asymptomatic HF (age 66.5 years ±10). In correlational analysis, gratitude was associated with better sleep (r=-.25, p<0.01), less depressed mood (r=-.41, p<0.01), less fatigue (r=-.46, p<0.01), and better self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function (r=.42, p<0.01). Patients expressing more gratitude also had lower levels of inflammatory biomarkers (r=-.17, p<0.05). We further explored relationships among these variables by examining a putative pathway to determine whether spirituality exerts its beneficial effects through gratitude. We found that gratitude fully mediated the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and sleep quality (z=−2.35, SE=.03, p=.02) and also the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and depressed mood (z=−4.00, SE=.075, p<.001). Gratitude also partially mediated the relationships between spiritual wellbeing and fatigue (z=−3.85, SE=.18, p<.001), and between spiritual wellbeing and self-efficacy (z=2.91, SE=.04, p=.003). In sum, we report that gratitude and spiritual wellbeing are related to better mood and sleep, less fatigue, and more self-efficacy, and that gratitude fully or partially mediates the beneficial effects of spiritual wellbeing on these endpoints. Efforts to increase gratitude may be a treatment for improving wellbeing in HF patients’ lives and be of potential clinical value.

Keywords: heart failure, gratitude, spiritual wellbeing, mood, inflammation, sleep

INTRODUCTION

“Gratitude unlocks the fullness of life... It turns denial into acceptance, chaos into order, confusion into clarity... It turns problems into gifts, failures into success, and mistakes into important events. Gratitude makes sense of our past, brings peace for today and creates a vision for tomorrow.”

Melodie Beattie

Heart Failure (HF) is a major public health concern, affecting over 6 million Americans, with rates expected to nearly triple over the next few decades as the population ages (Krum & Stewart, 2006). It is the end stage of most cardiac anomalies, with the annual number of hospitalizations exceeding 1 million, and U.S. direct costs exceeding $40 billion/year (Desai & Stevenson, 2012; G. Wang, Zhang, Ayala, Wall, & Fang, 2010).

In the field of behavioral cardiology (Rozanski, 2014), there is increasing interest in examining associations between positive psychological attributes such as spirituality and gratitude, potential mechanisms of their action, and importantly, associations with clinical outcomes (Dubois et al., 2012; Huffman et al., 2011; Sacco, Park, Suresh, & Bliss, 2014). In many populations, spirituality and/or religious wellness are associated with better mental and physical health. In a recent meta-analytic review, for example, Bonelli and Koenig (2013) reported that religious/spiritual involvement is correlated with better mental health, including less depression (Bonelli & Koenig, 2013), although such associations are not always observed (Morgenstern et al., 2011). In patients with symptomatic HF, there is a positive correlation between spiritual wellbeing and better mental health (Whelan-Gales, Quinn Griffin, Maloni, & Fitzpatrick, 2009). Additionally, symptomatic HF patients with higher measures of spiritual wellbeing have better HF-related health status (Bekelman et al., 2009).

Therapeutically, there is increasing recognition of the value of embracing multidisciplinary therapeutic approaches in HF that include spirituality as part of more routine psychosocial support (Naghi, Philip, Phan, Cleenewerck, & Schwarz, 2012). Spirituality-based interventions for improving mood and wellbeing in cardiovascular disease populations have shown promising outcomes and demonstrated good adherence in several pilot studies. For example, Delaney et al (2011) reported reduced depression scores among community-dwelling patients with cardiovascular disease following an individualized one-month spirituality-based intervention on health-related outcomes (Delaney, Barrere, & Helming, 2011). Warber et al. (Warber et al., 2011) examined the effects of a nondenominational spiritual retreat on depression and other measures of wellbeing in post acute coronary syndrome patients. A four-day spiritual retreat intervention included guided imagery, meditation, drumming, journal writing, and nature-based activities. A control intervention included nutrition education, exercise, and stress management. Both retreat groups received follow-up phone coaching biweekly for up to three months. Compared with the control group, patients assigned to the spiritual retreat group had significantly lower depression scores post-intervention, which were maintained 3 months later.

Gratitude is considered a positive psychological factor that has also been associated with wellbeing in some populations. According to Bussing et al., in clinical populations feelings of gratitude and awe facilitate perceptions and cognitions that go beyond the focus of the illness and include positive aspects of one's personal and interpersonal reality even in the face of disease (Bussing et al., 2014). According to Wood et al., gratitude is part of a wider life orientation towards noticing and appreciating the positive aspects of life (Wood, Froh, & Geraghty, 2010). Gratitude can be attributed to an external source such as an animal, person, or nonhuman (e.g., God, the cosmos), and may be part of a vaster perspective of noticing and appreciating the positive in the world (Wood et al., 2010). There are individual differences in dispositional gratitude, which entails how frequently and intensely people experience the emotion of gratitude, the range of events which elicit the emotion, and in the interpretation of social situations (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002; Wood, Maltby, Stewart, Linley, & Joseph, 2008). Longitudinal studies suggest that higher levels of gratitude are directly linked to improvements in perceived social support as well as reduced stress and depression, and that these direct effects are not explained by personality factors (Wood et al., 2008).

Gratitude has theological origins and the importance of its development and practice is emphasized in the majority of world religions. Prayer frequency has been found to increase gratitude, (Lambert, Graham, & Fincham, 2009) and in this way gratitude may serve as a pathway through which spirituality exerts its known positive effects on physical and mental health.

The American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) heart failure (HF) staging system denotes “Stage B patients” as asymptomatic but at high risk for developing symptomatic (Stage C) HF (Hunt, Abraham, et al., 2005). Stage B consists of patients who have developed structural heart disease (e.g., previous myocardial infarction, asymptomatic valvular disease) with specific left ventricular (LV) dysfunction that is associated with inflammation and the development of HF but who have never shown signs or symptoms of HF. Stage C HF further includes both structural or functional abnormality, increased inflammation, and exercise limitation from dyspnea or fatigue while Stage D includes severe ‘end-stage’ HF (Eisen, Benderly, Behar, Goldbourt, & Haim, 2014; Viganego & Le Jemtel, 2007). The ACC/AHA HF staging system emphasizes both the evolution and the progression of chronic HF and seeks to identify and implement early therapeutic interventions to ultimately reduce morbidity and mortality (Hunt, American College of, & American Heart Association Task Force on Practice, 2005). The stage B level of disease presents an important therapeutic window into potentially halting disease progression and improving quality of life. Progression from stage B HF to symptomatic HF is associated with a 5-fold increase in mortality risk (Ammar et al., 2007).

Within the growing field of studying relationships between gratitude and wellbeing, few studies have examined HF populations, and this is despite recent studies describing the importance of psychosocial resources such as gratitude in alleviating the struggles associated with living with symptomatic HF (Sacco et al., 2014). The purpose of this study therefore was to examine associations between spiritual wellbeing, gratitude, and physical and mental health in stage B HF patients and to examine a potential pathway (i.e., gratitude) through which spiritual wellbeing may promote physical and mental health benefits.

METHODS

Subjects

The sample consisted of 186 men and women with AHA/ACC classification Stage B HF with a diagnosis for at least 3 months. Patients were recruited from the cardiology clinics at the University of California San Diego Medical Centers and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS). Presence of Stage B HF was defined as structural heart disease based on recommendations and cut-points from the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines (Lang et al., 2005), including LV hypertrophy (defined as mean LV wall thickness of septum and posterior wall ≥ 12mm), LV enlargement (at least moderate in severity, defined as LV end diastolic diameter ≥ 64 mm in men or ≥ 58 mm in women, or LV mass index ≥ 132 in men or ≥ 109 in women), LV systolic dysfunction (defined as LV ejection fraction <55% or wall motion abnormality), LV diastolic dysfunction, asymptomatic valvular heart disease of at least moderate severity, or previous myocardial infarction, but without signs or symptoms of HF. Left ventricular ejection fraction (%LVEF) was assessed by echocardiography as part of the patient’s routine medical evaluation.

Protocol

The protocol was approved by the UCSD and VASDHS Institutional Review Boards and participants gave written informed consent. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. Upon presentation to the laboratory, a blood draw was obtained using a 21 or 23-gauge butterfly needle and participants completed a packet of psychosocial questionnaires.

Measures

Gratitude

Gratitude was assessed with the GQ-6 (Froh et al., 2011; McCullough et al., 2002). The GQ-6 is a psychometrically sound self-administered 6-item scale designed to measure trait gratitude. Internal consistency of the GQ-6 in this cardiac population was high, with a Cronbach's α of 0.92.

Spiritual Wellbeing

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACITsp12) was used to assess spiritual wellbeing (Peterman, Fitchett, Brady, Hernandez, & Cella, 2002). The FACITsp12 is a 12-item scale designed to measure the extent to which patients experienced spiritual wellbeing over the past week. Internal consistency reliability coefficients have ranged from .81 to .88, and convergent validity estimates show moderate to strong correlations with other measures of spirituality and religiousness (Peterman et al. 2002). In this cohort, Cronbach's α for the FACITsp12 was 0.85.

Depressive symptom severity

Symptoms of depression were assessed with the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-1a) where scores ≥10 indicate possible clinical depression (Beck, 1978). The BDI assesses symptoms related to sadness, feelings of guilt, suicidal ideation, and changes in appetite and body weight, among other characteristics. The BDI shows high reliability and structural validity and capacity to discriminate between depressed and non-depressed subjects with broad applicability for research and clinical practice worldwide (Y. P. Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). The BDI Cronbach's α for this sample was 0.85.

Sleep Quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality (Smyth, 2000). The PSQI is widely used in sleep research and measures sleep disturbance and usual sleep habits and has high internal reliability and construct validity (Carpenter & Andrykowski, 1998). In addition to component scores in domains of subjective sleep quality, latency and duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction, the PSQI also yields a global score (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). Cronbach's α for the PSQI global score was 0.83.

Fatigue

The Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-sf) was used to assess total fatigue (Stein, Jacobsen, Blanchard, & Thors, 2004). The MFSI has strong psychometric properties and is useful in medically ill and non-medically ill individuals (Donovan et al., 2014). Cronbach's α for the MFSI-sf was 0.87.

Self-Efficacy

The Cardiac Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (CSEQ) examines the role of patient self-efficacy for patients with coronary heart disease. The CSEQ has two factors (Control Symptoms and Maintain Function) and has high internal consistency and good convergent and discriminant validity (Sullivan, Russo Katon, 1998). We used the CSEQ-Maintain Function (mf) scale, and Cronbach's α was 0.85.

Inflammatory Markers

Inflammation is implicated in the pathogenesis of HF and inflammatory biomarkers are used for risk stratification and prognosis (Bouras et al., 2014). We therefore assessed a relevant panel of inflammatory biomarkers known to be involved in adverse remodeling of the heart and the progression to heart failure, including CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-gamma & ST2 (Cosper, Harvey, & Leinwand, 2012; Huang, Yang, Xiang, & Wang, 2014; Seljeflot, Nilsson, Westheim, Bratseth, & Arnesen, 2011; Sun et al., 2014). Whole blood was preserved with EDTA, and following centrifugation, the plasma was stored at -80o C until assay. Circulating levels of these biomarkers were determined by commercial ELISA (MSD, Rockville, MD). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients were <5%.

Statistical Analyses

Prior to statistical analyses all data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; no transformations were conducted. Correlational and mediation analyses were run using SPSS software packages (version 22.0) (IBM, Armonk, NY). The SPSS Dimension Reduction factor analysis program was used to calculate a composite inflammatory index score comprised of circulating levels of CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-gamma & ST2. The resultant factor score Eigenvalue was 3.23, accounting for 53.8% of inflammatory variance. We examined mediation using the approach outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). Using this mediation strategy, a series of regression analyses were run: first regressing the dependent variable on the independent variable (Step 1/Path c), next regressing the mediating variable on the independent variable (Step 2/Path a), and last regressing the dependent variable on both the mediating variable (Step 3/Path b) and the independent variable (Step 4/Path c’). We further examined the significance of the product of the path coefficients [(a*b) an estimate of the indirect effect] using the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents biological, medical, psychosocial, and inflammatory biomarker characteristics of the patients.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, Medical, Psychosocial, and Inflammatory Biomarker Characteristics of Study Participants

| Age [years] | 66.4 (10.3) |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 30.2 (5.6) |

| Gender (% men) | 95.3% |

| Systolic blood pressure [mmHg] | 134.2 (18.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure [mmHg] | 77.1 (11.9) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction [%] | 64.8% (8.95) |

| Concomitant disease | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.4% |

| Myocardial infarction | 17% |

| Medications | |

| ACE inhibitors | 39.1% |

| Beta blockers | 44.2% |

| Calcium channel blockers score | 20.1% |

| Statin | 55.0% |

| Aspirin | 39.0% |

| Diuretics | 32.1% |

| Anti-arrhythmic | 3.9% |

| Warfarin | 10.6% |

| Digoxin | 2.0% |

| Psychosocial | |

| Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) | 5.65 ± 1.09 |

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-sp12) | 12.07 ± 5.71 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-1a) | 8.84 ± 8.14 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | 8.92 ± 3.32 |

| Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory—Short Form (MFSI-sf) | 29.69 ± 21 |

| Cardiac Self-Efficacy Questionnaire—Maintain Function subscale | 16.08 ± 4.94 |

| Inflammatory Biomarkers | |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 6.04 (9.2) |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 2.21 (2.1) |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 4.25 (3.0) |

| IFN-gamma (ng/ml) | 2.39 (5.3) |

| ST-2 (pg/ml) | 17.9 (8.2) |

(n= 186; mean ± SD or percentage value)

Correlational Analyses

Gratitude was associated with better sleep (p<0.01), less depressed mood (p<0.01), less fatigue (p<0.01), and better self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function (p<0.01). Patients expressing more gratitude also had lower levels of the inflammatory biomarker index (p<0.05). Spiritual wellbeing was associated with better sleep p<0.01), less depressed mood (p<0.01), less fatigue (p<0.01), and better self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function (p<0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations

| Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) | Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-sp12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) | ||

| Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-sp12) | .55** | |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-1a) | −.46** | −.35** |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | −.32** | −.28** |

| Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory—Short Form (MFSI-sf) | −.50** | −.50** |

| Cardiac Self-Efficacy Questionnaire—Maintain Function subscale (CSEQ-mf) | .43** | .46*** |

| Inflammatory Index (CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-gamma & ST2) | −.17* | −.10 |

p < .001

p<.05

Gratitude as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Spirituality and Physical and Mental Health

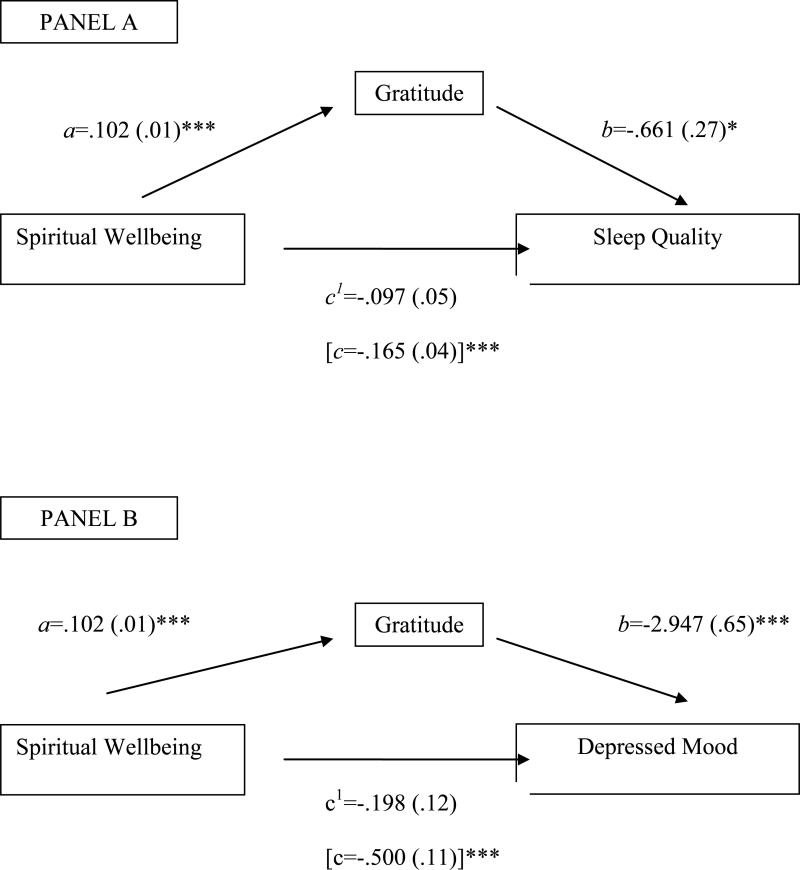

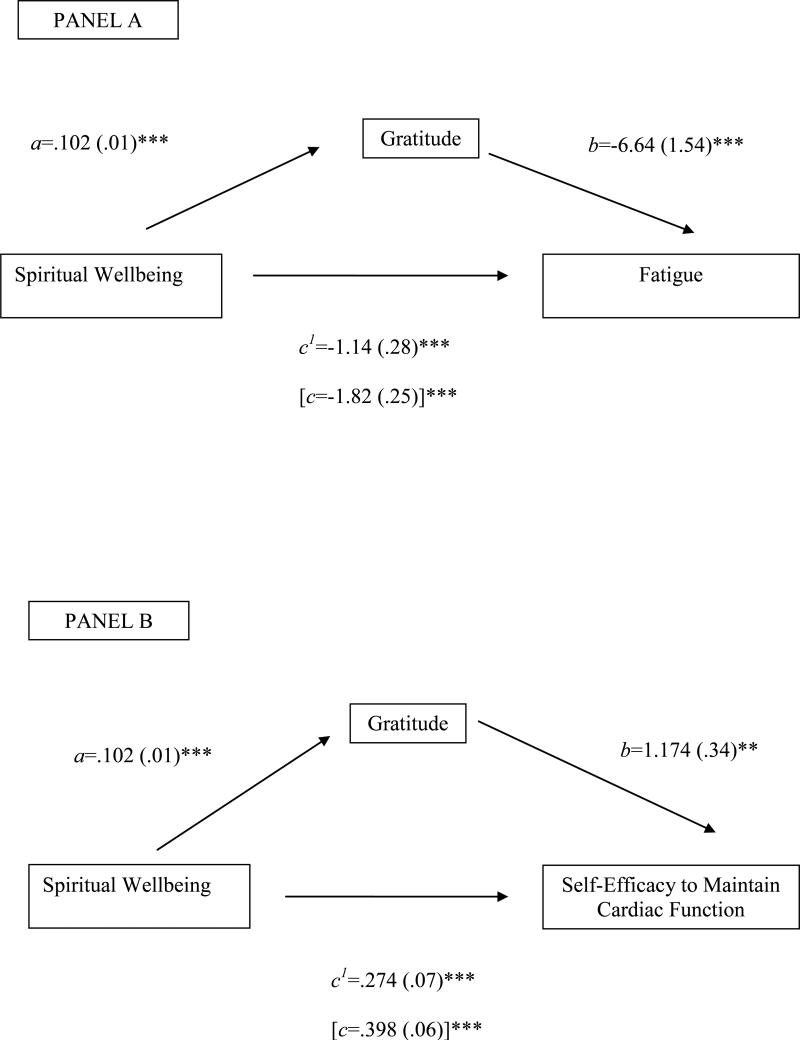

Mediation analyses were conducted to examine whether gratitude mediates the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and aspects of physical and mental health. These effects were as follows (Figures 1 and 2):

Figure 1.

Trait gratitude significantly mediated the relationships between spiritual wellbeing and sleep quality and spiritual wellbeing and depressed mood. Path values are unstandardized regression coefficients with SE in parentheses. Mediated (indirect) effects were derived from the product of paths a and b and examined using the Sobel test (1982). Panel A: Trait gratitude fully mediated the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and sleep quality (z=−2.45, SE=.03, p=.02). Panel B: Trait gratitude fully mediated the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and depressed mood (z=-4.00, SE=.08, p<.001). *p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 2.

Trait gratitude significantly mediated the relationships between spiritual wellbeing and fatigue and spiritual wellbeing and self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function. Path values are unstandardized regression coefficients with SE in parentheses. Mediated (indirect) effects were derived from the product of paths a and b and examined using the Sobel test (1982). Panel A: Trait gratitude partially mediated the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and fatigue (z=−3.849, SE=.18, p<.001). Panel B: Trait gratitude partially mediated the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and cardiac-specific self-efficacy (z=2.91, SE=.04, p<.01). *p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001.

Sleep

In Step 1 of the mediation model, the regression of subjective sleep quality (PSQI) on spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12) was significant (R2 =.08, β =-.284, t(166)=−3.82, p<.001). Step 2 showed that the regression of spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12) on the mediator, trait gratitude (GQ-6), was also significant (R2 =.31, β =.552, t(169)=8.58, p<.001). Step 3 of the mediation process showed that the mediator, trait gratitude (GQ-6), controlling spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12), was significantly related to sleep quality (PSQI) (R2 =.11, β =-.213, t(167)=−2.42, p=.02). Step 4 of the analyses revealed that, when controlling for trait gratitude (GQ-6), spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12) no longer remained a significant predictor of subjective sleep quality (PSQI) (R2 = .11, β =-.167, t(167)=1.89, p=.06), indicating that the beneficial effect of spirituality on sleep exerts its effect through gratitude. We further examined the strength of the indirect or mediated effect using the Sobel test and confirmed its significance (z=-2.35, SE=.03, p=.02).

Depressed Mood

In Step 1, we regressed depressed mood (BDI) on spiritual wellbeing (FACITSP12) and this relationship was significant (R2 =.13, β =-.355, t(157)=−4.765, p<.001). Step 2 outputs are the same in all 4 mediation models. Step 3 demonstrated that the mediator, trait gratitude (GQ-6) was related to depressed mood (BDI) when controlling for spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12) (R2 = .23, β =−3.84, t(158)=−4.536, p<.001). Step 4 indicated that when controlling for trait gratitude (GQ-6), the relationship between spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12) and depressed mood (BDI) is no longer significant (R2 = .23, β =-.384, t(156)=−1.663, p=.10), indicating that gratitude fully mediates the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and depressed mood. We again confirmed the significance of the mediation using the Sobel test (z=−4.00, SE=.075, p<.001).

Fatigue

When examining fatigue (MFSI-sf), there was again evidence of relationship with spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12) (R2 =.25, β =-.499, t(163)=−7.342, p<.001) in Step 1, and Step 3 again demonstrated a relationship between trait gratitude (GQ-6) and fatigue (MFSI-sf) when controlling for spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12), (R2 = .33, β=-.335, t(162)=−4.318, p<.001). However, Step 4 revealed that the relationship between spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12) and fatigue (MFSI-sf) remains significant controlling for the putative mediator, gratitude (GQ-6) (R2 = .33, β =-.312, t(162)=−4.020, p<.001). Although the c1 path remains significant, the Sobel test of the indirect or mediated pathway was also significant (z=−3.85, SE=.18, p<.001), providing evidence to suggest that gratitude partially mediates the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and fatigue.

Self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function

In our analyses examining self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function (CSEQ-mf), in Step 1 there was a significant relationship with spiritual wellbeing (FACITSP12) (R2=.21, β =.456, t(159)=6.453, p<.001). In Step 3, there was evidence of a relationship between trait gratitude (GQ-6) and self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function (CSEQ-mf) when controlling for spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-SP12), (R2 = .25, β=.256, t(158))=3.10, p=.002. In Step 4, the relationship between spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-sp12) and self-efficacy to maintain cardiac function (CSEQ-mf) remains significant when controlling for our hypothesized mediator, gratitude (GQ-6 (R2 = .25, β =.314, t(158)=3.087, p<.001). Again though, the Sobel test of the indirect or mediated pathway was also significant (z=2.91, SE=.04, p=.003), suggesting that gratitude partially mediates the relationship between spirituality and cardiac-specific self-efficacy.

Inflammatory Index

In our mediation analyses examining inflammation, there was no relationship between spiritual wellbeing and the inflammatory index (R2 = .01, β=−1.02, t(140)=−1.21, p=23). Similarly, Step 3 and 4 of the mediation analyses were not significant and consequently no relationship between spirituality and inflammation for gratitude to potentially mediate.

DISCUSSION

In stage B asymptomatic HF patients, we found that gratitude was related to better mood and sleep, more self-efficacy, and lower fatigue and inflammation. Spiritual wellbeing was related to each of these as well, with the exception of the inflammatory index. When examining these relationships in more depth, we found that gratitude fully mediated the beneficial effects of spiritual wellbeing on sleep and depressed mood and partially mediated the relationships between spiritual wellbeing and fatigue and spiritual wellbeing and cardiac-specific self-efficacy. Stage B patients are asymptomatic but at high risk for developing symptomatic (Stage C) HF, and thus present an opportunity to implement early therapeutic interventions to ultimately reduce morbidity and mortality (Hunt, American College of, et al., 2005). Interventions designed to increase gratitude do improve psychological wellbeing (Wood et al., 2010).

Research findings from gratitude studies suggest that gratitude, due to its orientation towards positive appraisal, is likely incompatible with the “negative triad” of beliefs associated with depression (Evans et al., 2005). Indeed, gratitude is related to both hedonic wellbeing (i.e., “subjective wellbeing” as characterized by higher positive affect, lower negative affect, and life satisfaction) and eudaimonic wellbeing (i.e., “psychological wellbeing”, characterized by aspects such as environmental mastery, personal autonomy, purpose in life, positive relations with others, and personal growth (Evans et al., 2005; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). In turn, both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing have been linked to reduced likelihood of depression (e.g., (Pressman & Cohen, 2005; Wood et al., 2008), as well as alterations in immune function associated with improved health (Ryff, Singer, & Dienberg Love, 2004). Thus one potential pathway by which gratitude may promote wellbeing, as well as better cardiovascular health in HF, is through the enhancement of both subjective (hedonic) and psychological (eudaimonic) wellbeing (Wood et al., 2010). Importantly, a recent review reports that wellbeing is associated with improved cardiovascular health, with hedonic wellbeing noted to be associated with improved biological function and restorative health behaviors; the authors noted a need for more data on the potential impact of eudaimonic wellbeing on cardiovascular outcomes (Boehm & Kubzansky, 2012).

Another potential pathway by which gratitude may enhance health is via shifts in affective perceptions of daily life events from negative to positive. The chronic hassles and uplifts scale is an index of daily perceptions of events as either hassles (negative) or uplifts (positive), and has been found to correlate with mood, health, and positive affect (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). In a study by our group, we reported independent relationships of uplifts (frequency and intensity) and inflammatory markers that were independent of sociodemographic, behavioral, medical and psychological variables such as hassles, depression, and perceived stress. (Jain, Mills, von Kanel, Hong, & Dimsdale, 2007), suggesting that positive perceptions of daily life events is uniquely associated with inflammation. Gratitude may reduce inflammatory markers in Stage B HF patients through changes in affective perceptions of daily life.

Gratitude was associated with lower depressed mood scores in these patients, and mediated the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and mood. Prior studies report that self-rated spiritual wellbeing is strongly and independently associated with fewer depressive symptoms in stage B HF patients (Peterman et al., 2002). This is clinically significant since the presence of depressive symptoms in cardiovascular diseases such as HF is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular hospitalization and mortality (Johnson et al., 2012; Kato et al., 2012; Rutledge, Reis, Linke, Greenberg, & Mills, 2006). Typical risk factors associated with depression in HF include increasing age, poor physical fitness, poor sleep, fatigue, and inflammation (Alosco et al., 2013; Jimenez & Mills, 2012; Mills et al., 2009; Shimizu, Suzuki, Okumura, & Yamada, 2013; Sin, 2012) (Kupper, Widdershoven, & Pedersen, 2012; Tang, Yu, & Yeh, 2010). For stage B HF patients, finding correlates of depressive symptoms is particularly important as an avenue for potentially forestalling development of symptomatic Stage C disease, which is significantly associated with poorer quality of life and increased morbidity and mortality (Ammar et al., 2007). In terms of gratitude interventions, in a recent double-blind randomized controlled trial in health care practitioners, Cheng et al. showed that a four-week gratitude journaling intervention, as compared to journaling about hassles, led to a significant reduction in stress and improved mood (Cheng, Tsui, & Lam, 2014). Other interventions focusing on “thoughts of gratitude” reveal that gratitude interventions have a significant effect on improving daily positive emotions (Ouweneel, Le Blanc, & Schaufeli, 2014). Few studies, however, have examined the potential benefits of gratitude interventions for HF despite studies describing the importance of gratitude in alleviating the struggles associated with living with HF (Sacco et al., 2014). Sacco et al. developed an 8-week phone-based positive psychology intervention for patients hospitalized with acute cardiac disease (acute coronary syndrome or decompensated heart failure), which was comprised of positive psychology exercises adapted for this population with a focus on gratitude, optimism, and kindness. Their initial findings include that the intervention is well accepted in cardiac patients; further outcome data are pending (Sacco et al., 2014).

It is worth noting that while gratitude is considered a positive psychological factor, it is not necessarily good for all people under all circumstances, e.g., displaced gratitude under conditions of exploitation; gratitude with discernment is worth cultivating. As far as the scientific literature, the vast majority of research demonstrates positive, not negative, consequences of gratitude and that cultivating gratitude doesn’t necessarily reduce seeing the negative features of life but rather offers or encourages seeing the positive in life (Eaton, Bradley, & Morrissey, 2014; Wood et al., 2008).

Summary

Gratitude and spiritual wellbeing are key positive factors to consider in this population. We documented that an attitude of gratitude is related to better mood and sleep, less fatigue, more self-efficacy, and a lower cellular inflammatory index. Untangling these relationships further, we found that higher trait gratitude mediates spiritual wellbeing's positive effects on better sleep and less depressed mood (and to a lesser degree fatigue and cardiac-specific self-efficacy). These are potentially important observations because depressed mood and poor sleep are associated with worse prognosis in HF as well as other cardiac populations and therefore interventions that increase levels of gratitude may have clinical implications for improving health outcomes (Canivet, Nilsson, Lindeberg, Karasek, & Ostergren, 2014; Huffman, Celano, Beach, Motiwala, & Januzzi, 2013; Rutledge et al., 2006). Given that interventions to increase gratitude are relatively simple and low-cost, efforts to increase gratitude in HF patients’ lives may be of potential clinical value and represent a treatment target for improving wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants HL-073355, HL-096784, and 1UL1RR031980-01 from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Greater Good Science Center, Berkeley, CA.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None.

Conflicts of Interest. None

REFERENCES

- Alosco ML, Spitznagel MB, van Dulmen M, Raz N, Cohen R, Sweet LH, Gunstad J. Depressive symptomatology, exercise adherence, and fitness are associated with reduced cognitive performance in heart failure. J Aging Health. 2013;25(3):459–477. doi: 10.1177/0898264312474039. doi: 10.1177/0898264312474039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar KA, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, Kors JA, Redfield MM, Burnett JC, Jr., Rodeheffer RJ. Prevalence and prognostic significance of heart failure stages: application of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association heart failure staging criteria in the community. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1563–1570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666818. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression inventory. Philadelphia. Center for Cognitive Therapy; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, Yamashita TE, Hutt E, Gottlieb SH, Kutner JS. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: a comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):592–598. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0931-y. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0931-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart's content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychol Bull. 2012;138(4):655–691. doi: 10.1037/a0027448. doi: 10.1037/a0027448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli RM, Koenig HG. Mental disorders, religion and spirituality 1990 to 2010: a systematic evidence-based review. J Relig Health. 2013;52(2):657–673. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9691-4. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9691-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouras G, Giannopoulos G, Hatzis G, Alexopoulos D, Leventopoulos G, Deftereos S. Inflammation and Chronic Heart Failure: From Biomarkers to Novel Anti-inflammatory Therapeutic Strategies. Med Chem. 2014 doi: 10.2174/1573406410666140318113325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing A, Wirth AG, Reiser F, Zahn A, Humbroich K, Gerbershagen K, Baumann K. Experience of gratitude, awe and beauty in life among patients with multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canivet C, Nilsson PM, Lindeberg SI, Karasek R, Ostergren PO. Insomnia increases risk for cardiovascular events in women and in men with low socioeconomic status: a longitudinal, register-based study. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(4):292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST, Tsui PK, Lam JH. Improving Mental Health in Health Care Practitioners: Randomized Controlled Trial of a Gratitude Intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0037895. doi: 10.1037/a0037895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosper PF, Harvey PA, Leinwand LA. Interferon-gamma causes cardiac myocyte atrophy via selective degradation of myosin heavy chain in a model of chronic myocarditis. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(6):2038–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.040. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney C, Barrere C, Helming M. The influence of a spirituality-based intervention on quality of life, depression, and anxiety in community-dwelling adults with cardiovascular disease: a pilot study. J Holist Nurs. 2011;29(1):21–32. doi: 10.1177/0898010110378356. doi: 10.1177/0898010110378356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Rehospitalization for heart failure: predict or prevent? Circulation. 2012;126(4):501–506. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.125435. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.125435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan KA, Stein KD, Lee M, Leach CR, Ilozumba O, Jacobsen PB. Systematic review of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form. Support Care Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2389-7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois CM, Beach SR, Kashdan TB, Nyer MB, Park ER, Celano CM, Huffman JC. Positive psychological attributes and cardiac outcomes: associations, mechanisms, and interventions. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(4):303–318. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.04.004. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton RJ, Bradley G, Morrissey S. Positive predispositions, quality of life and chronic illness. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(4):473–489. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.824593. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.824593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen A, Benderly M, Behar S, Goldbourt U, Haim M. Inflammation and future risk of symptomatic heart failure in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2014;167(5):707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.01.008. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Heron J, Lewis G, Araya R, Wolke D, team A. s. Negative self-schemas and the onset of depression in women: longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:302–307. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.302. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: implications for theory and research. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26(3):309–317. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Fan J, Emmons RA, Bono G, Huebner ES, Watkins P. Measuring gratitude in youth: assessing the psychometric properties of adult gratitude scales in children and adolescents. Psychol Assess. 2011;23(2):311–324. doi: 10.1037/a0021590. doi: 10.1037/a0021590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Yang D, Xiang M, Wang J. Role of interleukin-6 in regulation of immune responses to remodeling after myocardial infarction. Heart Fail Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9431-1. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, Celano CM, Beach SR, Motiwala SR, Januzzi JL. Depression and cardiac disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;2013:695925. doi: 10.1155/2013/695925. doi: 10.1155/2013/695925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, Mastromauro CA, Boehm JK, Seabrook R, Fricchione GL, Denninger JW, Lyubomirsky S. Development of a positive psychology intervention for patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Heart Int. 2011;6(2):e14. doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e14. doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Heart Rhythm S. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112(12):e154–235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SA, American College of C, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice, G. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(6):e1–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.022. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Mills PJ, von Kanel R, Hong S, Dimsdale JE. Effects of perceived stress and uplifts on inflammation and coagulability. Psychophysiology. 2007;44(1):154–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00480.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez JA, Mills PJ. Neuroimmune mechanisms of depression in heart failure. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;934:165–182. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-071-7_9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-071-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Basu S, Pisani BA, Avery EF, Mendez JC, Calvin JE, Jr., Powell LH. Depression predicts repeated heart failure hospitalizations. J Card Fail. 2012;18(3):246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.12.005. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato N, Kinugawa K, Shiga T, Hatano M, Takeda N, Imai Y, Nagai R. Depressive symptoms are common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiol. 2012;60(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.01.010. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krum H, Stewart S. Chronic heart failure: time to recognize this major public health problem. Med J Aust. 2006;184(4):147–148. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper N, Widdershoven JW, Pedersen SS. Cognitive/affective and somatic/affective symptom dimensions of depression are associated with current and future inflammation in heart failure patients. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.029. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert NM, Graham SM, Fincham FD. A prototype analysis of gratitude: varieties of gratitude experiences. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2009;35(9):1193–1207. doi: 10.1177/0146167209338071. doi: 10.1177/0146167209338071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, European Association of, E. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112–127. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE, Natarajan L, Ziegler MG, Maisel A, Greenberg BH. Sleep and health-related quality of life in heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2009;15(5):228–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00106.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern LB, Sanchez BN, Skolarus LE, Garcia N, Risser JM, Wing JJ, Lisabeth LD. Fatalism, optimism, spirituality, depressive symptoms, and stroke outcome: a population-based analysis. Stroke. 2011;42(12):3518–3523. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625491. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghi JJ, Philip KJ, Phan A, Cleenewerck L, Schwarz ER. The effects of spirituality and religion on outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure. J Relig Health. 2012;51(4):1124–1136. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouweneel E, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB. On being grateful and kind: results of two randomized controlled trials on study-related emotions and academic engagement. J Psychol. 2014;148(1):37–60. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.742854. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.742854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):925–971. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanski A. Behavioral cardiology: current advances and future directions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(1):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.047. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(8):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(4):719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH, Dienberg Love G. Positive health: connecting well-being with biology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1449):1383–1394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco SJ, Park CL, Suresh DP, Bliss D. Living with heart failure: psychosocial resources, meaning, gratitude and well-being. Heart Lung. 2014;43(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.01.012. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seljeflot I, Nilsson BB, Westheim AS, Bratseth V, Arnesen H. The L-arginine-asymmetric dimethylarginine ratio is strongly related to the severity of chronic heart failure. No effects of exercise training. J Card Fail. 2011;17(2):135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.09.003. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Suzuki M, Okumura H, Yamada S. Risk factors for onset of depression after heart failure hospitalization. J Cardiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.11.003. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin MK. Personal characteristics predictive of depressive symptoms in Hispanics with heart failure. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(8):522–527. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.687438. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.687438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth C. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Insight. 2000;25(3):97–98. doi: 10.1067/min.2000.107649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KD, Jacobsen PB, Blanchard CM, Thors C. Further validation of the multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory-short form. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun RR, Lu L, Liu M, Cao Y, Li XC, Liu H, Zhang PY. Biomarkers and heart disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18(19):2927–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang WR, Yu CY, Yeh SJ. Fatigue and its related factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(1-2):69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02959.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viganego F, Le Jemtel TH. Progression and management of chronic heart failure. Panminerva Med. 2007;49(3):109–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Zhang Z, Ayala C, Wall HK, Fang J. Costs of heart failure-related hospitalizations in patients aged 18 to 64 years. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(10):769–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YP, Gorenstein C. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: a comprehensive review. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35(4):416–431. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warber SL, Ingerman S, Moura VL, Wunder J, Northrop A, Gillespie BW, Rubenfire M. Healing the heart: a randomized pilot study of a spiritual retreat for depression in acute coronary syndrome patients. Explore (NY) 2011;7(4):222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2011.04.002. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan-Gales MA, Quinn Griffin MT, Maloni J, Fitzpatrick JJ. Spiritual well-being, spiritual practices, and depressive symptoms among elderly patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Geriatr Nurs. 2009;30(5):312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2009.04.001. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Stewart N, Linley PA, Joseph S. A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion. 2008;8(2):281–290. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.281. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]