Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Health care systems need effective models to manage chronic diseases like tobacco dependence across transitions in care. Hospitalizations provide opportunities for smokers to quit, but research suggests that hospital-delivered interventions are effective only if treatment continues after discharge.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether an intervention to sustain tobacco treatment after hospital discharge increases smoking cessation rates over standard care.

DESIGN

A randomized controlled trial conducted from August 2010-November 2012 compared Sustained Care, a post-discharge tobacco cessation intervention, vs. Standard Care among hospitalized adult smokers who received a tobacco dependence intervention in the hospital and wanted to quit smoking after discharge.

SETTING

Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

PARTICIPANTS

397 hospitalized daily smokers (mean age 53 years, 48% male, 81% nonhispanic white). 92% of eligible patients and 44% of screened patients enrolled.

INTERVENTION

Sustained Care participants received automated interactive voice response telephone calls and their choice of free FDA-approved cessation medication for 90 days. The automated calls promoted cessation, provided medication management, and triaged smokers for additional counseling. Standard Care patients received recommendations for post-discharge pharmacotherapy and counseling.

MAIN OUTCOMES

Biochemically-validated past 7-day tobacco abstinence 6 months after discharge (primary outcome); self-reported tobacco abstinence and smoking cessation treatment use at 1, 3, and 6 months.

RESULTS

Smokers assigned to Sustained Care (n=198) used more counseling and more pharmacotherapy at each follow-up than those assigned to Standard Care (n=199). Biochemically-validated 7-day tobacco abstinence at 6 months was higher with Sustained Care than Standard Care (26% vs. 15%; RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.14–2.56, p=0.009; NNT=9.4, 95% CI 6.4–35.5). Using multiple imputation for missing outcomes, the RR was 1.55 (95%CI 1.03–2.21, p=0.038). Sustained Care also produced higher self-reported continuous abstinence rates for 6 months after discharge (27% vs. 16%; RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.15–2.51, p=0.007).

CONCLUSION

Among hospitalized adult smokers who planned to quit smoking, a post-discharge intervention providing automated telephone calls and free medication resulted in higher rates of smoking cessation at 6 months compared with a standard recommendation to use counseling and medication after discharge. These findings, if replicated, suggest an approach to help achieve sustained smoking cessation after a hospital stay.

Keywords: Inpatients, hospitalization, smoking cessation, nicotine dependence, nicotine addiction, tobacco use, interactive voice response, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the United States’ leading preventable cause of death.1 The U.S. Public Health Service’s clinical practice guideline recommends offering tobacco cessation counseling and pharmacotherapy to smokers in every health care setting.2 For the nearly 4 million smokers hospitalized each year, a hospital stay offers a good opportunity to quit smoking because all hospitals are now smoke-free, requiring patients to abstain temporarily from tobacco use.3 Simultaneously, their illness, especially if tobacco-related, can enhance their motivation to quit. Providing tobacco cessation treatment in the hospital increases long-term smoking cessation rates after discharge, but evidence suggests that this requires treatment to be sustained for over a month after discharge.3 In 2012, the Joint Commission adopted a tobacco cessation hospital quality measure, endorsed by the National Quality Forum in 2014, that requires hospitals to document patients’ smoking status and offer hospitalized smokers tobacco cessation counseling and pharmacotherapy.4 ,5

Hospitals’ major challenge to providing evidence-based care is identifying how to sustain tobacco treatment after discharge.3 This represents a broader challenge facing health care systems, coordinating the management of patients with chronic diseases as they transition between inpatient and outpatient care.6,7 For smokers, sustaining cessation treatment after discharge has additional challenges. Nicotine replacement, the most widely used pharmacotherapy, is not consistently covered by health insurers. Free tobacco quitlines, the most accessible counseling resource, are poorly linked to health care systems.8

To address these gaps, we designed an intervention using interactive voice response technology9–11 to facilitate the delivery of evidence-based tobacco cessation counseling and medication after hospital discharge. The goal was to create a low-cost translatable system requiring minimal health system personnel to implement. We compared this Sustained Care intervention to Standard Care in a randomized clinical trial. The hypothesis was that Sustained Care would increase the proportion of individuals who used evidence-based tobacco cessation treatment and were tobacco abstinent 6 months after hospital discharge.

Methods

The Helping HAND (Hospital-initiated Assistance for Nicotine Dependence) trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners HealthCare and registered with the National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Registry (NCT01177176). A detailed study protocol has been published.12

Setting and Subjects

The study was conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a 900-bed hospital in Boston, MA. Adults (≥18 years old) who were admitted to MGH were eligible if they were current smokers (smoked ≥1 cigarette daily in the month before admission), received smoking cessation counseling in the hospital, stated that they planned to try to quit smoking after discharge, and agreed to accept a smoking cessation medication. Patients were excluded if they had no telephone; an expected hospital stay of <24 hours; past 12-month substance use other than tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana, or were admitted for an alcohol or drug overdose; could not give informed consent or participate in counseling due to psychiatric or cognitive impairment or communication barrier; were admitted to the obstetric or psychiatric units; had an estimated life expectancy of <12 months; or medical instability.

All MGH patients have their smoking status electronically documented at admission, generating a roster of hospitalized smokers accessed daily by Tobacco Treatment Service counselors who aim to visit every hospitalized smoker. They ensure adequate withdrawal symptom management with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and offer to assist smokers who plan to stay quit after discharge. Counselors screened smokers for study eligibility and referred the smoker to research staff to confirm eligibility, obtain informed consent, conduct the baseline assessment, and assign the participant to study condition.

Assignment to Condition

Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to Sustained Care or Standard Care in permuted blocks of 8, stratified by daily cigarette consumption (< 10 vs. ≥ 10) and admitting service (cardiac vs. other). Treatment assignment was concealed in sequentially numbered sealed envelopes within each stratum. Research staff opened the next envelope corresponding to the participant’s randomization stratum.

Intervention

The Sustained Care condition had two components designed to reduce patient barriers to completing a full course of the tobacco treatment after discharge. First, a 30-day supply of free FDA-approved tobacco cessation medication was provided at discharge, refillable twice for up to 90 days of treatment. Medication was chosen by the patient and smoking counselor during the inpatient visit. It could include single agents (nicotine patch, gum, lozenge, or bupropion or varenicline) or a combination of these. Second, 5 automated outbound interactive voice response telephone calls (2, 14, 30, 60, and 90 days after discharge) provided advice and support messages that prompted smokers to stay quit, encouraged proper use and adherence to cessation medication, offered medication refills, and triaged smokers to a return call from a live counselor for additional support. The automated telephone script encouraged participants to request a call-back from a counselor if they had low confidence in their ability to stay quit, resumed smoking but still wanted to quit, needed a medication refill, had problems with medication, or stopped using medication. A trained counselor made the return calls using a standardized protocol.12 A fax sent to patients’ primary care clinicians informed them of the treatment program.

Standard Care provided smokers with a specific post-discharge medication recommendation and advice to call a free telephone quitline (1-800-QUIT-NOW). A note in the chart advised hospital physicians to prescribe the medication upon discharge.

Measures/Assessments

Baseline measures included demographic factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education), health insurance, smoking history (cigarettes/day, Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence, other tobacco products), prior use of tobacco cessation treatment, perceived importance of and confidence in quitting (10-point Likert scales), presence of a smoker at home, alcohol use (AUDIT-C), and the 8-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).13–15 Race/ethnicity was assessed by patient self-report. Hospital records provided primary discharge diagnosis, length of stay, smoking cessation medication use in hospital and the counselor’s recommendation for post-discharge tobacco cessation medication. Participants were called 1, 3, and 6 months after discharge. A telephone interviewer collected data on tobacco use status and tobacco cessation treatment use. We defined tobacco cessation treatment to include any FDA-approved pharmacotherapy (including NRT, bupropion, or varenicline) or cessation counseling provided by a doctor, nurse, MGH or community counselor, or state telephone quitline). Participants were reimbursed $20 per completed survey.

The primary outcome was biochemically-validated 7-day point prevalence tobacco abstinence 6 months after discharge. Tobacco abstinence was defined as abstinence from any tobacco product including electronic cigarettes. To verify self-reported abstinence at 6 months, patients were asked to provide a mailed saliva sample for assay of cotinine, a nicotine metabolite, and reimbursed $50 for the sample.16 Participants using NRT had an in-person measurement of expired air carbon monoxide (CO). Self-reported abstinence was considered verified if saliva cotinine was ≤10 ng/ml or CO<9 ppm.17 Secondary smoking status outcomes were self-reported 7-day point prevalence and continuous abstinence at 1, 3, and 6 months post-discharge.

Analysis

A sample of 330 was planned to provide 83% power to detect a 15% difference (20% vs 35%) in the primary outcome. The sample was increased to 400 without interim analysis to add statistical power. Analyses were done using an intent-to-treat approach using SAS version 9.3 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We compared participants’ characteristics by group using two-sample t-tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and chi-square tests. A two-sided p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. According to the pre-specified protocol,12 we conducted cross-sectional analyses at each follow-up point, comparing rates of tobacco treatment and cessation between study groups using chi-square tests, and calculated the number needed to treat.18 Secondarily, we conducted a longitudinal analysis using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) techniques that included data from all follow-up times to assess the overall intervention impact. Per pre-specified protocol,12 patients with missing outcomes at follow-up (including those who died) or whose self-reported abstinence was not biochemically validated were counted as smokers in the primary analysis. We conducted a sensitivity analysis using previously-published methods to assess the relationship between alternate approaches to imputation and effect size.19 We also used multiple imputation for the missing primary outcome measure, using age, gender, whether the patient had a smoking-related disease, and the smoking outcome at 3 months as predictors in a logistic regression model. The final inference was combined from 5 sets of imputed samples.

We explored the effect of the intervention in subgroups of participants defined post-hoc by age (<55/≥55 years), gender, race (nonhispanic white vs. others), cigarettes/day (<10/≥10), discharge diagnosis (circulatory disease vs. other, smoking-related disease1 vs. other), hospital length of stay (<5/≥5 d), nicotine replacement use during hospitalization, and depression symptoms (CES-D-8, <16/≥16). We tested the interaction between study group and each subgroup using Breslow-Day tests.

We prospectively tracked the direct costs of delivering Sustained Care exclusive of research costs. Costs included the interactive voice response service, up to 90 days of medication (using the price paid by our institution), mailing medication refills, personnel time, and office space. Personnel time included time for database construction and management, counselor training, time spent offering the intervention, tracking patients, managing medications in the hospital and post-discharge, and reaching out to and counseling patients post-discharge. The value of staff time was based on salary and fringe benefits. Office space, computer, and telephone cost was based on institutional charges. We calculated the incremental cost-per-quit and cost-per-patient of delivering Sustained Care compared to Standard Care from a health system perspective. We evaluated costs under 2 scenarios. In the first, the hospital paid for all medications, reflecting how the trial was conducted. In the second, we assumed the hospital could bill insurers for smoking cessation medications, as should be possible with near-universal coverage of smoking cessation medications under the Affordable Care Act.20

Results

Recruitment and retention

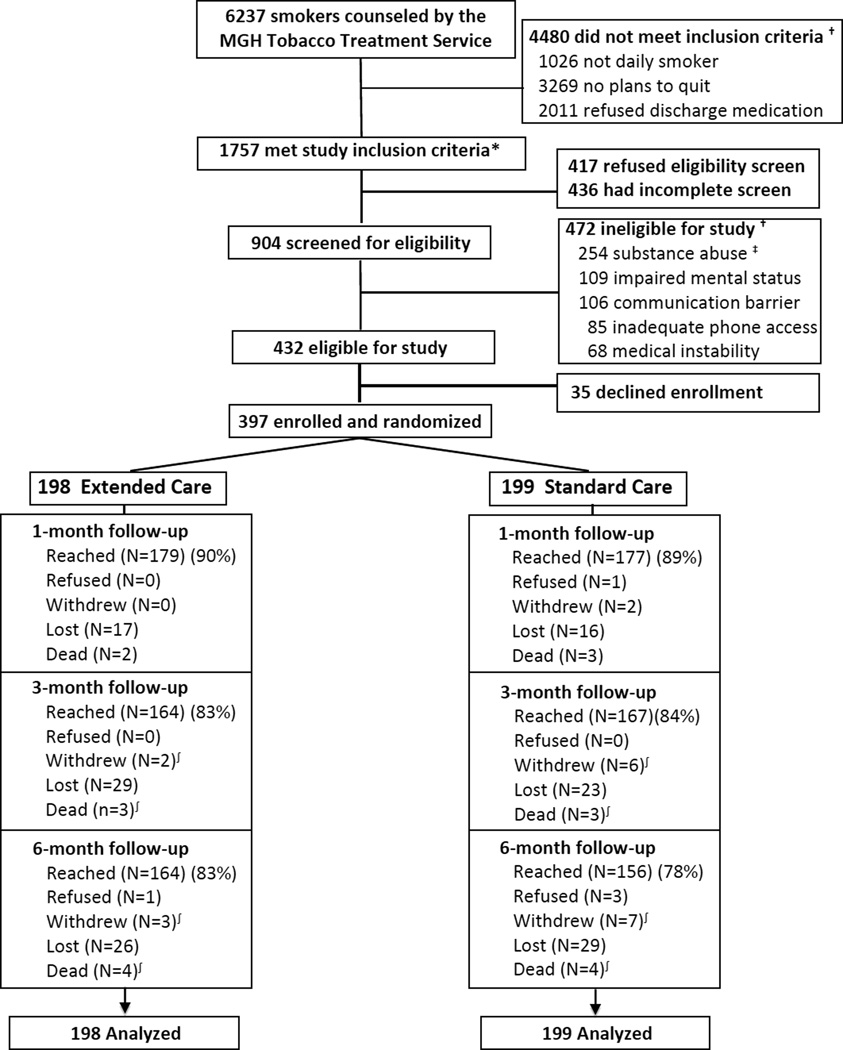

Between August 11, 2010, and April 17, 2012, MGH TTS staff counseled 6237 inpatient smokers, and 1757 (28%) of them met initial study inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of these 1757, 904 (51%) completed screening for eligibility and 432 (48%) of those screened were eligible for the study. Figure 1 displays the most common reasons for ineligibility. A total of 397 patients (92% of those eligible, 44% of those screened) consented to enroll and were randomly assigned to receive Sustained Care (n=198) or Standard Care (n=199) after discharge. Follow-up survey completion rates were 90% at 1 month, 83% at 3 months, and 81% at 6 months, with no statistically significant difference by study group (Figure 1). Participants lost to follow-up were younger (mean 50 vs. 53 years, p=.04) but did not differ in gender, cigarettes/day, or admission to the cardiac service. Eight participants (2%) died, 4 in each group. Among self-reported nonsmokers, 78% provided a biological sample for confirmation (79% of Sustained Care, 77% of Standard Care), and abstinence was confirmed in 85% of these samples (86% of Sustained Care, 83% of Standard Care). These rates did not differ significantly by group.

Figure 1.

Study Flow (CONSORT) diagram

Footnotes:

*Study inclusion criteria: ≥18 yo, daily smoker, plans to quit and will accept cessation medication after discharge.

† Patients may have had more than one reason for study ineligibility.

‡ Substance abuse refers to past-year illicit drug use (except marijuana) or alcohol or drug overdose as reason for current admission.

∫ Numbers of patients who withdrew and died are cumulative.

Baseline characteristics and hospital stay

Baseline characteristics and hospital course were comparable between study groups (Table 1). Participants’ mean age was 53 years; 48% were males, 81% were nonhispanic whites, and 51% had a high school education or less. Participants smoked a mean of 16.7 cigarettes daily. Median hospital stay was 5 days (IQR, 3–7 days). The primary discharge diagnoses encompassed a range of organ systems, but circulatory disease, comprising cardiovascular, peripheral vascular, and cerebrovascular diagnoses, was the largest single category (38%). For 45% of participants, the primary discharge diagnosis was a smoking-related disease1 (defined in Table 1 footnote). Tobacco cessation treatment in the hospital did not differ by group; mean counseling time was 25 minutes (range, 9–50), and 67% of participants used an in-hospital cessation medication, generally NRT used to manage nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Post-discharge medication recommendations did not differ by study group (Table 1) and usually continued the use of NRT started in the hospital.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants by Treatment Group

| Characteristic | Sustained Care N=198 |

Standard Care N=199 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (mean years, SD) | 53.9 | 11.7 | 51.2 | 12.4 |

| Sex (male) | 102 | 51.5 | 91 | 45.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White nonhispanic | 156 | 78.8 | 166 | 83.4 |

| Black nonhispanic | 8 | 4.0 | 10 | 5.0 |

| Hispanic | 11 | 5.6 | 11 | 5.5 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Native American | 8 | 4.0 | 5 | 2.5 |

| Other/unknown | 10 | 5.1 | 7 | 3.5 |

| Education | ||||

| High school/GED or less | 99 | 50.0 | 105 | 52.8 |

| Some college | 60 | 30.3 | 67 | 33.7 |

| College graduate | 39 | 19.7 | 26 | 13.1 |

| Health Insurance | ||||

| Commercial | 97 | 49.0 | 85 | 42.7 |

| Medicare | 56 | 28.3 | 54 | 27.1 |

| Medicaid | 33 | 16.7 | 43 | 21.6 |

| Other | 8 | 4.0 | 14 | 7.0 |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Cigarettes/day (mean, SD) | 17.1 | 10.0 | 16.3 | 10.4 |

| Past 30 day use of | ||||

| Non-cigarette tobacco product | 7 | 3.5 | 5 | 2.5 |

| Electronic cigarette | 11 | 5.6 | 12 | 6.0 |

| Marijuana | 27 | 13.6 | 32 | 16.1 |

| FTND* (mean, SD) | 5.0 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 2.2 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Depression symptoms (CESD-R†)(mean, SD) | 9.3 | 5.7 | 10.3 | 5.8 |

| Alcohol use (AUDIT-C‡)(mean, SD) | 3.4 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 2.6 |

| Quitting history and predictors | ||||

| Prior use of | ||||

| Nicotine replacement | 118 | 59.6 | 131 | 65.8 |

| Bupropion | 25 | 12.6 | 38 | 19.1 |

| Varenicline | 51 | 25.8 | 54 | 27.1 |

| Smoking counseling | 3 | 1.5 | 12 | 6.0 |

| Live with smoker | 79 | 39.9 | 86 | 43.2 |

| Importance to quit now (0–10) (mean, SD) | 9.4 | 1.3 | 9.5 | 1.1 |

| Confidence to resist urge to smoke in any situation (0–10) (mean, SD) | 7.3 | 2.2 | 7.4 | 2.3 |

| Hospital course | ||||

| Length of stay (days) (median, IQR) | 5 | 3–7 | 4 | 3–7 |

| Primary discharge diagnosis | ||||

| Smoking related disease∫ | 90 | 45.5 | 89 | 44.7 |

| ICD-9 groups | ||||

| Circulatory§ | 71 | 35.9 | 80 | 40.2 |

| Injury / poisoning | 29 | 14.6 | 23 | 11.6 |

| Respiratory | 23 | 11.6 | 16 | 8.0 |

| Neoplasm | 17 | 8.6 | 17 | 8.5 |

| Digestive | 14 | 7.1 | 13 | 6.5 |

| Endocrine | 8 | 4.0 | 7 | 3.5 |

| Musculoskeletal | 10 | 5.1 | 11 | 5.5 |

| Neurological | 8 | 4.0 | 4 | 2.0 |

| Genitourinary | 3 | 1.5 | 6 | 3.0 |

| Other | 15 | 7.6 | 21 | 10.6 |

| Used smoking cessation medication in hospital | ||||

| Nicotine replacement | 130 | 65.7 | 125 | 62.8 |

| Bupropion | 2 | 1.0 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Varenicline | 7 | 3.5 | 9 | 4.5 |

| Post-discharge medication recommendation by hospital counselor | ||||

| Nicotine replacement | 191 | 96.5 | 191 | 96.0 |

| Bupropion | 14 | 7.1 | 12 | 6.0 |

| Varenicline | 13 | 6.6 | 13 | 6.5 |

FTND: Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (range 0–10).13 Higher values indicate greater nicotine dependence.

CESD-R: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (8 items, range 0–24).15 Higher values indicate more depressive symptoms.

AUDIT-C (3 items, range, 0–12).14 Higher values indicate more alcohol use.

Circulatory includes cardiovascular, peripheral vascular, and cerebrovascular diseases.

Smoking-related diseases are those specified in the 2014 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report.1 These include neoplasms (ICD-9 codes 140–151, 157, 161, 162, 180, 188, 189, 204–208), cardiovascular diseases (ICD-9 codes: 410–414, 390–398, 415–417, 420–429, 430–438, 440–448), respiratory diseases (ICD-9 480–492, 496), and perinatal conditions (ICD-9 765, 769, 798.0).

Use of tobacco cessation treatment after discharge

Table 2 displays participants’ self-reported use of tobacco cessation treatment at 1, 3, and 6 months after discharge. Patients with missing data are counted as having received no treatment. We obtained similar findings when the analysis excluded patients with missing data. Participants in the Sustained Care group, compared to the Standard Care group, were more likely to use tobacco cessation treatment in the month after hospital discharge (83% vs. 63%; RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.16–1.49, p<.001), including both pharmacotherapy (79% vs. 59%; RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.17–1.54, p<.001) and counseling (37% vs. 23%; RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.19–2.23, p=.002). The cumulative use of both treatments increased over 6 months, and rates of both remained higher in the Sustained Care group through 6 months. Sustained Care participants accepted a median of 4 of the 5 IVR calls. In both groups, the post-discharge medication was predominantly combination NRT. Bupropion and varenicline were each used by ≤5.5% of participants, with no difference in use by study group (data not shown). Participants in the Sustained Care group, compared to the Standard Care group, also had a longer duration of medication use. In the Sustained Care group, 61% of participants completed ≥8 weeks of the 12 week treatment course, compared to 37% in the Standard Care group (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Use of Smoking Cessation Treatment after Hospital Discharge by Treatment Group*

| Outcome Measure | Sustained Care N=198 |

Standard Care N=199 |

P | Relative Risk |

95% Confidence Interval |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Use of any smoking cessation treatment† (%) | |||||||

| 1 month | 164 | 82.8 | 125 | 62.8 | <.0001 | 1.32 | 1.16–1.49 |

| 3 months (cumulative) | 172 | 86.9 | 152 | 76.4 | .009 | 1.14 | 1.03–1.25 |

| 6 months (cumulative) | 178 | 89.9 | 160 | 80.4 | .011 | 1.12 | 1.03–1.21 |

| Use of any smoking cessation counseling† (%) | |||||||

| 1 month | 73 | 36.9 | 45 | 22.6 | .002 | 1.63 | 1.19–2.23 |

| 3 months (cumulative) | 114 | 57.6 | 82 | 41.2 | .001 | 1.40 | 1.14–1.71 |

| 6 months (cumulative) | 136 | 68.7 | 102 | 51.3 | .0005 | 1.34 | 1.14–1.58 |

| Use of any smoking cessation medication† (%) | |||||||

| 1 month | 156 | 78.8 | 117 | 58.8 | <.0001 | 1.34 | 1.17–1.54 |

| 3 months (cumulative) | 164 | 82.8 | 132 | 66.3 | .0002 | 1.25 | 1.11–1.40 |

| 6 months (cumulative) | 170 | 85.9 | 140 | 70.4 | .0002 | 1.22 | 1.10–1.36 |

| Use of nicotine replacement‡(%) | |||||||

| 1 month | 147 | 74.2 | 110 | 55.3 | <.0001 | 1.34 | 1.16–1.56 |

| 3 months (cumulative) | 155 | 78.3 | 123 | 61.8 | .0004 | 1.27 | 1.11–1.44 |

| 6 months (cumulative) | 161 | 81.3 | 130 | 65.3 | .0004 | 1.24 | 1.10–1.41 |

| Duration of medication use (%) | |||||||

| 2 weeks or more | 146 | 73.7 | 103 | 51.8 | <.0001 | 1.42 | 1.22–1.67 |

| 4 weeks or more | 137 | 69.2 | 90 | 45.2 | <.0001 | 1.53 | 1.28–1.83 |

| 8 weeks or more | 120 | 60.6 | 73 | 36.7 | <.0001 | 1.65 | 1.33–2.05 |

Participants lost to follow-up or with missing data are counted as having received no treatment. An alternate analysis excluding patients with missing data produced similar results.

Smoking cessation treatment includes counseling or any FDA-approved pharmacotherapy. Smoking cessation counseling could be provided by a doctor, nurse, hospital or community counselor, or state telephone quitline. Smoking cessation medication includes nicotine replacement products, bupropion, or varenicline. They could be used as single agents or in combination.

There were no between-group differences for bupropion or varenicline, which were each used by ≤5.5% of study participants.

Tobacco cessation

Table 3 displays the tobacco cessation outcomes. More Sustained Care than Standard Care participants achieved the primary outcome, biochemically-confirmed past 7-day tobacco abstinence at 6-month follow-up (26% vs. 15%, RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.14–2.56, risk difference 11%, 95% CI 3–19%, p<.009). The number needed to treat was 9.4 (95% CI 5.4–35.5). Conclusions did not change in sensitivity analyses done to account for different scenarios of missing outcome data19 (See Online Supplement). When multiple imputation was applied to missing biochemical outcomes, the combined rate ratio was 1.55 (95%CI 1.03–2.21, p=0.038) with 5 sets of imputed samples.

Table 3.

Tobacco abstinence rates after discharge, by group*

| Outcome Measure | Sustained Care N=198 |

Standard Care N=199 |

P | Relative Risk |

95% Confidence Interval |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Biochemically confirmed† | |||||||

| Abstinent for the past 7 days† (%) | |||||||

| 6 months | 51 | 25.8 | 30 | 15.1 | .009 | 1.71 | 1.14–2.56 |

| Self-report | |||||||

| Abstinent for the past 7 days‡ (%) | |||||||

| 1 month | 103 | 52.0 | 78 | 39.2 | .012 | 1.33 | 1.07–1.65 |

| 3 months | 89 | 44.9 | 73 | 36.7 | .100 | 1.23 | 0.96–1.56 |

| 6 months | 81 | 40.9 | 56 | 28.1 | .008 | 1.45 | 1.10–1.92 |

| Abstinent since hospital discharge‡ (%) | |||||||

| 1 month | 91 | 46.0 | 66 | 33.2 | .010 | 1.39 | 1.08–1.78 |

| 3 months | 67 | 33.8 | 47 | 23.6 | .027 | 1.43 | 1.04–1.97 |

| 6 months | 54 | 27.3 | 32 | 16.1 | .007 | 1.70 | 1.15–2.51 |

Participants with missing outcome data are counted as smokers in these analyses.

Pre-specified primary outcome measure: self-reported past 7 day tobacco abstinence at 6 month follow-up confirmed by saliva cotinine <=10 ng/ml or CO < 9ppm. Participants are counted as smokers if they do not provide a biological sample or exceed cutoffs.

includes no reported use of cigarettes, other tobacco products, or electronic cigarettes.

Self-reported tobacco abstinence rates were also higher for Sustained Care than for Standard Care for both point-prevalence (past 7-day) abstinence and continuous abstinence. Self-reported past 7-day abstinence rates were 52% vs. 39% at 1 month (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.07–1.65, p=.012) and 41% vs. 28% at 6 months (RR 1.45, 95% CI, 1.10–1.92, p=.008). Overall, the RR was 1.32 (95%CI 1.09–1.58, p=.007) in a longitudinal analysis using the GEE technique. Self-reported continuous tobacco abstinence after hospital discharge was higher for Sustained Care than Standard Care at each follow-up assessment: 1 month (46% vs. 33%, RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.08–1.77, p=.01), 3 months (34% vs. 24%, RR 1.43, 95%CI 1.09–1.97, p=.027) and 6 months (27% vs. 16%, RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.15–2.51, p=.007). Overall, the RR was 1.49 (95%CI 1.13–1.89, p=.005) in a longitudinal analysis using the GEE technique. The median duration of self-reported continuous tobacco abstinence after hospital discharge was longer in the Sustained Care group (28 days; IQR, 5–175 d) than in the Standard Care group (18 days, IQR, 5–96 d) although not statistically significant (p=.079).

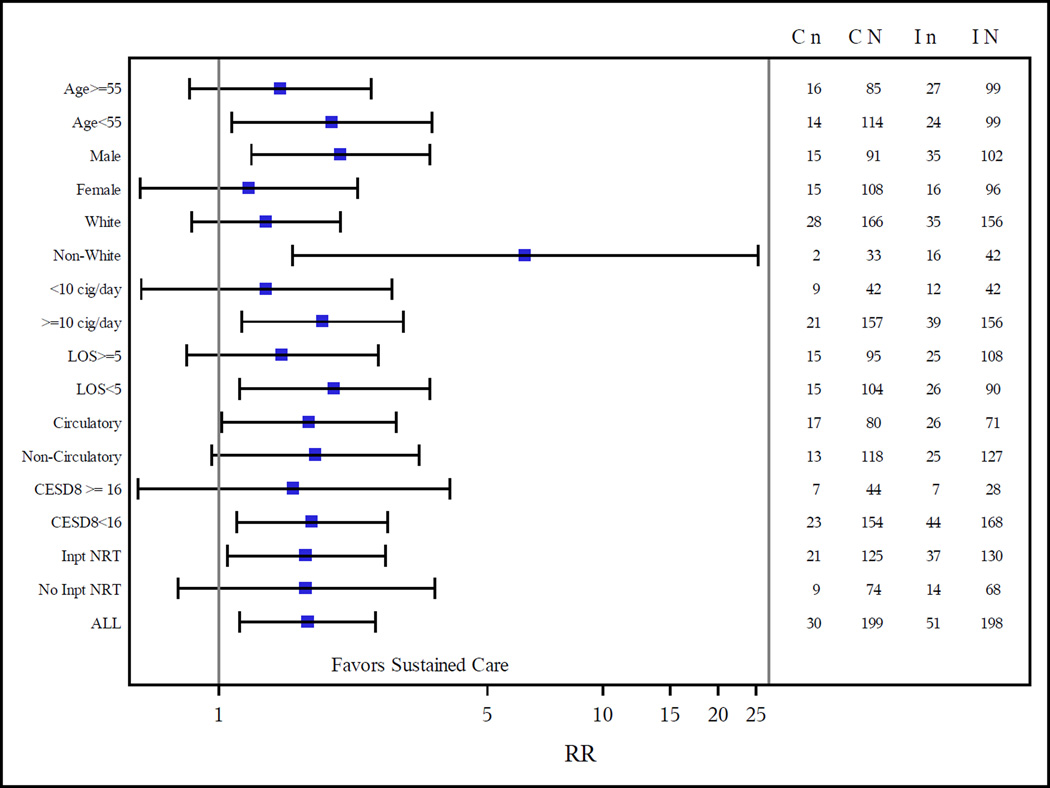

The magnitude of the intervention effect was generally similar across subgroups (Figure 3). The only statistically significant interaction with study group was race (p=.016). The intervention had a stronger effect in nonwhites than in whites; the validated 6-month smoking cessation rate for Sustained Care vs. Standard Care conditions was 38% vs. 6% among 75 non-whites (p=.001) and 22% vs. 17% among 322 whites (p=.26).

Cost-per-quit

For this trial, the hospital provided Sustained Care to approximately 100 smokers annually for 2 years. At this patient volume, the hospital’s estimated incremental cost-per-quit was $4910 (Year 1) and $2670 (subsequent years), while incremental per-patient costs were $540 (Year 1) and $294 (subsequent years). Year 1 costs were primarily for building the telephone system and training staff. Medication purchase was the main cost in subsequent years. The Affordable Care Act now requires insurers to cover all FDA-approved smoking cessation medications.20,33 Assuming that insurers cover this cost, the estimated incremental cost-per-quit from the hospital’s perspective would be $3217 (Year 1) and $997 (subsequent years). The cost-per-patient would be $354 (Year1) and $108 (subsequent years). The complete cost-effectiveness analysis is presented in the Online Supplement.

Discussion

The Helping HAND trial demonstrated the effectiveness of a program to promote long-term tobacco cessation among hospitalized cigarette smokers who received an inpatient tobacco dependence intervention and expressed an interest in post-discharge cessation treatment. The intervention aimed to sustain the tobacco cessation treatment that had begun in the hospital. It succeeded in improving smokers’ use of both counseling and pharmacotherapy after discharge, and it increased by 71% the proportion of patients with biochemically-confirmed tobacco abstinence 6 months after discharge, a standard measure of long-term smoking cessation. The intervention appeared to be effective across a broad range of smokers and provided high-value care at relatively low cost. Hospitals could adopt this model to help meet the Joint Commission’s tobacco cessation hospital quality standard.4,5 The intervention could also be incorporated into care delivery models that aim to improve population health by coordinating the care of smokers with other chronic diseases across transitions of care.6,7,21,22

The intervention used interactive voice response technology to automate telephone calls, providing an efficient, low-cost way to systematically maintain contact with smokers after hospital discharge. In a previous study, we provided automated calls for one month after hospital discharge to all smokers, regardless of their intention to quit.11 It was feasible but did not increase smoking cessation rates. The current study focused the intervention on smokers who planned to quit, extended automated telephone calls for three months and paired them with smoking cessation medication provided at no cost to patients at discharge. It also expanded the scope of automated calls to monitor and promote medication adherence and facilitate medication refills. Sustained Care increased smokers’ use of both counseling and pharmacotherapy after discharge, which may have mediated the improved smoking cessation rates.

Interactive voice response technology has been used in health care systems to assess post-discharge surgical outcomes and to deliver care to individuals with chronic diseases like diabetes.10,23 It has been a component of smoking interventions in ambulatory care and the community.24–27 Our program was based on a Canadian model that offered tobacco cessation counseling by interactive voice response calls after discharge.28,29 That model improved 6-month continuous abstinence rates over baseline rates in a pre-post evaluation in 6 hospitals.29 Our program extends the Canadian model by offering medication at no cost to patients at discharge and by adding a medication adherence component to the IVR system. Our study also used the stronger design of a randomized controlled trial.

Pharmacotherapy was used after discharge by most smokers in both study groups, probably because the inpatient smoking counselor encouraged NRT use in hospital and made a post-discharge medication recommendation for all participants.30 However, the Sustained Care program increased the duration of pharmacotherapy use after discharge. Sixty-one percent of smokers in the Sustained Care group used medication for 8 or more weeks of a 12-week course, whereas nearly half (48%) of smokers in the Standard Care group used it for 2 weeks or less. The longer treatment duration likely contributed to the 70% higher quit rate in the Sustained Care group. The magnitude of the improvement is at the higher end of the 50–70% relative increase in cessation rates produced by nicotine replacement overall, probably reflecting good medication adherence, use of combination NRT over a single NRT product, and the concomitant use of counseling.31,32

This study has several limitations. First, we cannot separate the independent contributions of free medication and interactive voice response support to the treatment effect. A future study with a factorial design could test this, although an interaction between the two factors is possible because automated calls provide both medication adherence support and cessation counseling. Second, our results apply only to hospitalized smokers who plan to quit after discharge. Future trials could assess whether the intervention can also benefit smokers who are not planning to quit, but those smokers may have limited interest accepting calls or in taking cessation medication even if it is offered to them at no cost. Third, the study was conducted at one hospital which limits the generalizability of the findings. We are replicating the study in a multi-site trial.34 Finally, 19% of participants were lost to follow-up by the 6-month assessment and 22% of those not smoking did not provide a saliva sample for verification. Considering the low-contact nature of the trial, our follow-up rates compare favorably to those of other hospital-based trials.3 Furthermore, our results are not subject to bias due to differential follow-up rates by study group.

Conclusions

Among hospitalized adult smokers who planned to quit smoking, a post-discharge intervention that included automated telephone calls and free medication resulted in higher sustained smoking cessation rates than standard post-discharge advice to use smoking cessation medication and counseling. These findings, if replicated, suggest a translatable low-cost approach to achieving sustained smoking cessation after a hospital stay.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Effect of the intervention in subgroups

Footnotes:

RR=Relative Risk, with 95% confidence limits shown.

C n = the number of patients with 7d abstinence in Standard Care (control group);

C N = the total number of patients in Standard Care (control group);

I n = the number of patients with 7d abstinence from Sustained Care (intervention group);

I N is the total number of patients in Sustained Care (intervention group).

LOS = length of hospital stay.

Inpt NRT = inpatient nicotine replacement therapy.

CESD8= Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (8-item version) 15

Circulatory includes cardiovascular, peripheral vascular, and cerebrovascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

TelAsk Technologies of Ottawa, Canada, developed and provided the IVR services and was compensated for this work by the NHLBI grant that funded the project.

This study is part of the Consortium of Hospitals Advancing Research on Tobacco (CHART) initiative, jointly sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Drug Abuse and NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research.35 We are grateful to our NHLBI project officers, William Riley, PhD, and Catherine Stoney, PhD, for guidance. We did not compensate them for their contributions.

Funding

NIH/NHLBI grants #RC1 HL099668 and #K24 HL004440. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Rigotti had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT 01177176

Contributions

Design and conduct of the study: Drs. Rigotti, Regan, Levy, Japuntich, Chang, Park, Singer, Mr. Viana, Ms. Reyen, Ms. Kelley.

Data collection: Joseph Viana. Other research assistants (Molly Korotkin, Joanna Streck, and Justyna Tymoszczuk) collected data as part of their salaried jobs supported by the grant. MGH Tobacco Treatment Service counselors Beth Ewy, MPH; Caitlin McCann, BA; Nancy McCleary, RN; Kathleen McKool, RN, MSN, and Jean Mizer, RN) screened patients for eligibility as part of their positions funded by Massachusetts General Hospital.

Data management: Dr. Regan

Data analysis: Dr. Chang, Dr. Levy

Manuscript drafting: Dr. Rigotti

Interpretation of the data and manuscript review and approval: Drs. Rigotti, Regan, Levy, Japuntich, Chang, Park, Singer, Mr. Viana, Ms. Reyen, Ms. Kelley.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Dr. Rigotti has been an unpaid consultant for Pfizer, Inc and Alere Wellbeing, Inc., regarding smoking cessation and receives royalties from UpToDate for reviews on smoking cessation. Pfizer paid for Dr. Rigotti’s travel expenses to attend a consultant meeting for which she received no honorarium. Dr. Park has a grant from Pfizer to provide free varenicline for use in a trial funded by NCI. Dr. Levy has been a paid consultant to CVS, Inc., to provide expertise on tobacco policy. Dr. Singer has been a paid consultant for Pfizer, Inc., but on matters separate from smoking cessation. No other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Accessed 1/18/14]. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. May, [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigotti NA, Clair C, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. [Accessed February 20, 2014];Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (5) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub3. Available from EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews at http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=coch&NEWS=N&AN=00075320-100000000-01256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Fiore MC, Goplerud E, Schroeder SA. The Joint Commission’s new tobacco cessation measures – will hospitals do the right thing? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1172–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1115176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Quality Forum. [Accessed March 10, 2014];NQF endorses behavioral health measures. 2014 Mar 7; http://www.qualityforum.org/News_And_Resources/Press_Releases/2014/NQF_Endorses_Behavioral_Health_Measures.aspx.

- 6.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care – a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1064–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutten LJ, Davis K, Squiers L, Augustson E, Blake K. Physician awareness and referral to national smoking cessation quitlines and web-based resources. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:79–81. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0163-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oake N, Jennings A, vanWalraven C, Forster AJ. Interactive voice response systems for improving delivery of ambulatory care. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:383–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forster AJ, Boyle L, Shojania KG, Feasby TE, vanWalraven C. Identifying patients with post-discharge care problems using an interactive voice response system. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:520–525. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan S, Reyen M, Lockhart A, Richards AE, Rigotti NA. An interactive voice response system to continue a hospital-based smoking cessation intervention after discharge. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:255–260. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Japuntich S, Regan S, Viana J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of postdischarge interventions for hospitalized smokers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:124. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melchior LA, Huba GJ, Brown VB, Reback CJ. A short depression index for women. Educ Psychol Meas. 1993;53:1117–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 16.SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1728–1733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806303182605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Demirtas H. Analysis of binary outcomes with missing data: missing = smoking, last observation carried forward, and a little multiple imputation. Addiction. 2007:1564–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Labor. [Accessed June 11, 2014];FAQs about Affordable Care Act Implementation (Part XIX) -- Q5. 2014 http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/faqs/faq-aca19.html.

- 21.Gourevitch MN. Population health and the academic medical center: the time is right. Acad Med. 2014;89:544–549. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public health. 2003;93:380–383. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piette JD, Weinberger M, McPhee SJ. The effect of automated calls with telephone nurse followup on patient-centered outcomes of diabetes care: a randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 2000;38:218–230. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDaniel AM, Benson PL, Roesener GH, Martindale J. An integrated computer-based system to support nicotine dependence treatment in primary care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S57–S66. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papadakis S, McDonald PW, Pipe AL, Letherdale ST, Reid RD, Brown KS. Effectiveness of telephone-based follow-up support delivered in combination with a multi-component smoking cessation intervention in family practice: a cluster-randomized trial. Preventive Med. 2013;56:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brendryen H, Kraft P. Happy ending: a randomized controlled trial of a digital multi-media smoking cessation intervention. Addiction. 2008;103:478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlini BH, McDaniel AM, Weaver MT, Kauffman RM, Cerutti B, Stratton RM, Zbikowski SM. Reaching out, inviting back: using interactive voice response (IVR) technology to recycle relapsed smokers back to Quitline treatment – a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:507. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid RD, Pipe AL, Quinlan B, Oda J. Interactive voice response telephony to promote smoking cessation in patients with heart disease: a pilot study. Patient Education & Counseling. 2007;66:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid RD, Mullen K, D'Angelo MES, Aitken DA, Papadakis S, Haley PM, McLaughlin CA, Pipe AL. Smoking cessation for hospitalized smokers: An evaluation of the “Ottawa Model”. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:11–18. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regan S, Reyen M, Richards AE, Lockhart AC, Liebman AK, Rigotti NA. Nicotine replacement therapy use at home after use during a hospitalization. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:885–889. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub4. Art. No.: CD000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(10) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub2. Art. No.: CD008286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonough JE, Adashi EY. Realizing the promise of the Affordable Care Act—January 1, 2014. JAMA. 2014;311:569–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.286067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Comparative Effectiveness of Post-Discharge Strategies for Hospitalized Smokers (Helping HAND2). Clinicaltrials.gov # NCT01714323. [ http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=%23NCT01714323&recr=&rslt=&type=&cond=&intr=&titles=&outc=&spons=&lead=&id=&state1=&cntry1=&state2=&cntry2=&state3=&cntry3=&locn=&gndr=&rcv_s=&rcv_e=&lup_s=&lup_e=provide URL]

- 35.Riley WT, Stevens VJ, Zhu SH, Morgan G, Grossman D. Overview of the consortium of hospitals advancing research on tobacco (CHART) Trials. 2012;13:122. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-122. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.