Abstract

Bioaccumulation of methylmercury in the aquatic food web is governed in part by the methylation of inorganic divalent mercury (Hg(II)) by anaerobic microorganisms. In sulfidic settings, a small fraction of total Hg(II) is typically bioavailable to methylating microorganisms. Quantification of this fraction is difficult due to uncertainties in the speciation of Hg(II) and the mechanisms of uptake by methylating microbes. However, recent studies have shown that the bioavailable fraction is likely to include a portion of Hg(II) associated with solid phases, that is, nanostructured mercuric sulfides. Moreover, addition of thiols to suspensions of methylating cultures coincides with increased uptake into cells and methylmercury production. Here, we present a thiol-based selective extraction assay to provide information on the bioavailable Hg fraction in sediments. In the procedure, sediment samples were exposed to a nitrogen-purged solution of glutathione (GSH) for 30 min and the amount of GSH-leachable mercury was quantified. In nine sediment samples from a marine location, the relative GSH-leachable mercury concentration was strongly correlated to the relative amount of methylmercury in the sediments (r2=0.91, p<0.0001) across an order of magnitude of methylmercury concentration values. The approach was further applied to anaerobic sediment slurry microcosm experiments in which sediments were cultured under the same microbial growth conditions but were amended with multiple forms of Hg with a known spectrum of bioavailability. GSH-leachable Hg concentrations increased with observed methylmercury concentrations in the microcosms, matching the trend of species bioavailability in our previous work. Results suggest that a thiol-based selective leaching approach is an improvement compared with other proposed methods to assess Hg bioavailability in sediment and that this approach could provide a basis for comparison of sites where Hg methylation is a concern.

Key words: : bioavailability, glutathione, marine sediment, mercury

Introduction

Mercury is known to be toxic to humans and wildlife, particularly in the form of methylmercury (Clarkson, 1997, 2002). The conversion of inorganic divalent mercury (Hg(II)) to methylmercury (MeHg) is generally regarded as an important step toward food web biomagnification (Merritt and Amirbahman, 2009). The generation of MeHg in aquatic environments is mediated by anaerobic microorganisms (Gilmour et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013). However, quantifying the fraction of Hg(II) available for methylation is difficult, because a number of factors such as pH, porewater sulfide, and organic carbon concentrations affect the speciation, reactivity, and bioavailability of mercury to methylating microorganisms (Skyllberg, 2008; Hsu-Kim et al., 2013). To better predict the methylation potential of mercury in sediment, knowledge of the bioavailable fraction of mercury is needed.

Many methods have been proposed to quantify the bioavailable fraction of mercury in natural sediments (For this study, the context of the term mercury bioavailability is intended specifically for methylating microorganisms.). These approaches have included chemical equilibrium speciation models (Benoit et al., 1999a, 1999b; Drott et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2007) and chemical extraction methods (Bloom et al., 2003; Marvin-DiPasquale et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2013). The equilibrium speciation modeling approach has limitations in natural settings where poorly defined reactions for Hg speciation complicate the interpretation of results. For instance, mercury is capable of forming nanoscale particles with sulfide, and previous studies have shown that nanoparticulate HgS is more bioavailable for methylating bacteria when compared with their microparticulate counterparts (Zhang et al., 2012). This difference between nanoscale and microcrystalline phases is not predicted based on equilibrium solubility and cannot be explained entirely by the dissolution of Hg into bulk water (Zhang et al., 2012, 2014; Pham et al., 2014). In addition, the formation rate of nanoparticulate HgS is influenced by the amount of dissolved sulfide and natural organic matter (Deonarine and Hsu-Kim, 2009; Slowey, 2010; Gerbig et al., 2011; Graham et al., 2012a; Pham et al., 2014). Thus, to accurately quantify methylation, the system dynamics must be considered, which is beyond the capability of today's chemical speciation models.

Chemical extractions techniques for quantifying bioavailable Hg most notably include selective sequential extraction (SSE) (Bloom et al., 2003) and reactive mercury approaches (Marvin-DiPasquale et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2013). The SSE approach seeks to divide sediment-bound mercury into “biogeochemically relevant” species using acid and base extraction mixtures. In the development of this approach (Bloom et al., 2003), a positive correlation was observed between the amount of mercury extracted in a strong base solution (1 N KOH) and the amount of MeHg in the sediment samples, suggesting that some description of bioavailable Hg could be obtained with this extraction step. Previous work with this method has also indicated that geochemically distinct forms of Hg in soil and sediment particles (e.g., HgCl2, Hg-organic matter complexes, Hg0, HgS particles) can be distinguished by these five selective extractions (Kim et al., 2003).

Reactive mercury methods involve the quantification of tin-reducible mercury [i.e., reactive with stannous chloride (Marvin-DiPasquale et al., 2009)] or mercury that can be ethylated [i.e., reactive with sodium tetraethylborate (Liang et al., 2013)] under operationally defined conditions. The reactive Hg fraction is then presumed to represent or correlate to the bioavailable Hg fraction, although the basis for this assumption is unclear.

All of these chemical extraction approaches lack experimental validation such as methylation experiments where Hg bioavailability is carefully varied under the same microbial activities with respect to methylation and demethylation. Moreover, they utilize extraction reagents that do not mimic any part of the mercury dissolution or biouptake process in sediments. Thus, a robust method for quantifying the bioavailable fraction of total sediment mercury will greatly improve our ability to compare risks at multiple sites.

Previous studies have shown that the presence of thiols such as glutathione (GSH) and cysteine can enhance the bioavailability of Hg to certain methylating microorganisms (Schaefer et al., 2011; Graham et al., 2012b). Moreover, the reactivity of dissolved and particulate Hg sulfides with thiols correlated with differences in net methylation potential by methylating microorganisms (Zhang et al., 2012). Likewise, a number of recent studies point to thiols as the site for mercury binding to the cell envelope of methylating bacteria (Joe-Wong et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2013; Dunham-Cheatham et al., 2014, 2015). While the interactions between Hg and thiols in these studies and the mechanism of Hg uptake by the cell remain unknown, we hypothesize that a simple thiol-based selective extraction could be used to approximate the bioavailable fraction of Hg in anaerobic settings.

The objective of this study was to test this hypothesis through the development of a GSH-based selective leaching protocol as a surrogate measure of the bioavailable mercury fraction in natural sediments. We first tested two experimental variables (e.g., leaching time, solid-water ratio) and quantified how they might affect leachable Hg concentrations from sediments. From these experiments, we chose a specific selective extraction protocol that was applied to a collection of sediment samples from a marine location and correlated the leachable fraction of mercury to sediment MeHg. This thiol-based approach was compared with the SSE method proposed by Bloom et al. (2003). The GSH-leaching protocol was then applied to a series of sediment slurries that were spiked with multiple forms of mercury (dissolved, nanoparticulate HgS, and microparticulate HgS) that have varying degrees of bioavailability (Zhang et al., 2012).

Materials and Methods

Sediment samples

Sediment samples were obtained from nine locations (enumerated as MS-1 to MS-9) from the same marine water body in August 2012. The water depth at the site was ∼55–75 m, with surface and bottom temperatures of 29.5°C and 27°C, respectively. At all sampling locations, dissolved oxygen was not detectable beneath the sediment surface layer, and dissolved sulfide was also not detectable (<1 μM), indicating anoxic but not extremely reducing conditions (per communication with site managers). The precise location of the site cannot be disclosed due to contractual agreements with the site managers.

The top layer of sediment (approximately the top 5 cm) was collected in triplicate by Van Veen-type grab samplers, packed into acid-cleaned polyethylene containers with Teflon lined caps, immediately frozen at −20°C, and transported to the lab at Duke University for further analysis. Samples from each site were thawed at 4°C, analyzed for total Hg and MeHg contents, and used in the GSH-selective leaching experiment. Sediment moisture content was determined by drying samples at 110°C for 24 h.

SSEs were performed on sediments from five out of the nine sites (MS-1–MS-5). Sample mass limitation prevented us from performing sequential extractions with the other sites (see next for further description of methods). Likewise, solid-water Hg partitioning measurements were performed for a subset of samples (MS-1, -2, -8, and -9) that were available for this characterization. For these samples, the aqueous phase was separated from the solid phase by centrifugation (6,700 g for 5 min) or by ultracentrifugation (360,000 g for 1 h). Our previous study (Zhang et al., 2014) demonstrated that centrifugation of sediments yielded separation of large particles (>500 nm hydrodynamic diameter) from the supernatant, but that dissolved and colloidal particles (e.g., 25 nm aggregates of HgS nanoparticles) remained suspended in solution. Ultracentrifugation enabled sedimentation of nanoscale and larger particles from solution. Sediment–water Hg distribution ratios KD were calculated from the solid-phase Hg concentration divided by the aqueous-phase Hg concentration (as defined by either centrifugation or ultracentrifugation).

Materials

Ultrapure water (>18 MΩ cm; Millipore Milli-Q) was used to prepare all stock solutions. All glassware was soaked in 1 N HCl overnight for acid cleaning, followed by at least three water rinses before use. Trace metal-grade acids were used for all pH adjustments. All Hg particle solutions were contained in borosilicate vials with PTFE-lined screw caps.

A Hg(II) stock solution was made by dissolving Hg(NO3)2 in 0.1 M HNO3. Na2S stock solutions were prepared daily by first washing crystals of Na2S·9H2O with water purged for 20 min with high-purity N2 gas, drying the crystals with a lint-free tissue, followed by weighing and dissolving into degassed water. The Na2S stocks were stored at 4°C when not in use. The stock solution of Suwannee River (SR) humic acid (International Humic Substances Society) was prepared in a solution with the pH adjusted to 7. The sample was filtered with a 0.2 μm nylon syringe filter (VWR). The concentration of dissolved organic carbon in the humic acid stock after filtration was measured using a total organic carbon analyzer (Shimadzu TOC 500 total organic carbon analyzer).

HgS nanoparticles were synthesized according to a previous study (Zhang et al., 2012). In summary, 50 μM Hg(NO3)2 and 50 μM Na2S were added to a buffer solution containing 10 mg-C/L SR humic acid, 0.1 M NaNO3, and 4 mM sodium 4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-ethanesulfonate (adjusted to pH 7.5). The buffer solution was filtered with a 0.2 μm syringe nylon filter (VWR) before the addition of Hg and sulfide. The HgS stock solution was aged for 24 h at room temperature before use in the experiments. According to previous work (Pham et al., 2014), stocks prepared in this manner resulted in nanoparticles of a metacinnabar-like composition with a primary particle diameter of ∼5 nm and a hydrodynamic diameter of 33 nm.

A microparticulate HgS stock suspension was synthesized by adding dissolved Hg(NO3)2 and dissolved Na2S to obtain a final Hg concentration of 300 μM and a sulfide concentration of 400 μM. The suspension was mixed vigorously for 5 min until the particles were formed, and then the solution was aged for an additional 24 h under static conditions (Pham et al., 2014). Previous characterization by Pham et al. showed that the particles comprised crystalline β-HgS. The particles were not separated from the solution before use in the experiments, and thus excess sulfide was transferred to a final concentration of 0.6 μM sulfide in the seawater and sediment slurry mixtures.

Synthetic seawater (Instant Ocean) was prepared by dissolving 22 g/L in ultrapure water. The synthetic seawater was purged with N2 each day before use.

GSH selective extraction tests

Selective extractions involved the use of a GSH solution in synthetic seawater to leach Hg from the sediment samples. The development of the method first tested a range of sediment:water ratios. Then, experiments were performed to test a range of extraction times before application of a single protocol to all nine marine sediment (MS) samples. All experiments were performed in an anaerobic chamber (90% N2, 5% CO2, and 5% H2 atmosphere; Coy Labs).

The solid–water ratio for the extraction experiments was first tested by placing 10 mL of degassed synthetic seawater in a set of 15 mL glass vials and variable amounts of sediment (1, 2, and 8 g wet weight [w.w.]) from site MS-4. GSH was added to a final concentration of 1 mM in each vial and mixed end-over-end for 0.5, 1.5, and 3 h. After each mixing time point, a vial was centrifuged at 3,000 g for 5 min, the supernatant was filtered using a 0.22 μm polyethersulfone (PES) filter (Tisch), and 1 mL of this filtered supernatant was diluted in 20 mL of ultrapure water and acidified with 2% (v/v) BrCl before total dissolved Hg analysis. In addition, 1 mL of solution was filtered for measurements of dissolved GSH (Hsu-Kim, 2007). The GSH-leachable Hg for a specific leaching time point was calculated as the dissolved concentration of Hg in the sample minus the dissolved concentration of Hg in a sediment-seawater solution without GSH. The aqueous concentration of leachable Hg (in ng/L) was then multiplied by the solid–liquid ratio to convert the value to a dry sediment weight concentration of leachable Hg (in ng/g).

After the experimental test of sediment–water ratios, a wider range of mixing/leaching times was tested using three different sediments (MS-1, -4, and -5). Each vial contained 10 mL of degassed water, 1 g (w.w.) of sediment, and 1 mM GSH. The sediment–water slurries were mixed end-over-end, and individual vials were sacrificed at 0.5 h, 1, 2, 4, and 7 days of mixing times for analysis of leachable Hg concentration. A separate control experiment was performed where GSH was added to a solution of degassed synthetic seawater without sediment to track the potential loss of dissolved GSH over time via oxidation or sorption to the container.

For comparison of all nine sediment samples, the GSH selective extraction procedure involved 1 g of sediment, 10 mL of degassed synthetic seawater, and 1 mM of GSH. The vials were mixed for 30 min, and the aqueous phase was separated by centrifugation at 3,000 g and 0.22 μm filtration. These samples were preserved for Hg and GSH analysis, as described later in the chemical analysis section.

Hg-GSH complexes are expected to be in the form of HgH2(GSH)22− complexes at pH 7–8 (Hsu and Sedlak, 2003) and have the potential to sorb to sediment particles. The occurrence of this was tested in supplementary experiments with MS-4 sediments. First, a Hg-GSH solution was prepared by adding dissolved Hg(II) to a concentration of 200 nM in ultrapure water. Dissolved GSH was then added to a concentration of 100 mM. The solution was mixed end-over-end several times and held at room temperature for 1 h. This Hg-GSH stock solution (100 μL) was further diluted into 10 mL degassed seawater and 1 g of sediment (MS-4) to a final concentration of 2 nM Hg (4 ng Hg/g sediment) and 1 mM GSH. The Hg concentration was chosen based on the results of the selective extraction tests for MS-4 to replicate the concentration of dissolved Hg observed in the GSH-seawater-sediment mixtures. Samples were continuously mixed end-over-end for 30 min at 30 rpm. Filtered (0.22 μm nylon) supernatant from the mixture was then preserved and analyzed for total dissolved Hg concentration.

Anaerobic sediment slurry microcosms

Slurry microcosm experiments were performed to compare the GSH-extractable Hg concentration and the net production of methylmercury in sediments spiked with known mercury species with variable bioavailability. The microcosm incubation was similar to the method reported in Zhang et al. (2014) but was slightly modified to address the specific questions of this study. The MS-6 sediment was selected due to its relatively low total mercury concentration (1.7 μg/g dry weight) compared with the other sample sites. Synthetic seawater for the microcosms was amended with 10 mM pyruvate (as electron donor) and resazurin (0.002% wt/vol) (a redox indicator) and then purged with N2 for 2 h before it was mixed with the sediment samples in an anaerobic chamber.

The slurries were prepared by placing 30 g (w.w.) of sediment into glass, gas-tight jars and mixed with 75 mL seawater (amended with pyruvate and resazurin). These microcosms were used later to quantify the production of MeHg after amending with inorganic Hg. Replicate batches of the microcosms were prepared by using a smaller total volume but the same ratios of sediment, synthetic seawater, and added mercury (4 g sediment in 10 mL seawater). These smaller microcosms were used for analysis by the GSH selective extraction procedure. The sediment-seawater mixtures were then closed with gas-tight caps and incubated in the dark at room temperature (21–23°C) for 5 days. All handling of the sediments and subsequent slurry experiments were conducted in an anaerobic chamber.

At the end of the 5-day incubation period, the resazurin redox indicator was transformed from a pink color to no color, indicating that anaerobic conditions had developed in the microcosms [i.e., <−51 mV (Reddy et al., 2007)]. The sediment slurries were then spiked with mercury to a concentration of 3.7 μg/g of sediment, representing two times the amount of ambient Hg in the original sediment. Mercury was added to the slurry as one of the following: dissolved Hg, HgS nanoparticles, and HgS microparticles. In addition, two sets of controls were performed and incubated in parallel with the methylation experiments: (1) A slurry consisting of sediment, synthetic seawater, and no additional mercury (i.e., Hg blank); (2) A slurry of sediment, synthetic seawater, and 20 mM of sodium molybdate, a sulfate reduction inhibitor (Fleming et al., 2006) that was added 1 day before addition of dissolved Hg (i.e., molybdate control). After the addition of mercury, all slurries were incubated statically in the dark till 7 days at room temperature.

During the course of the slurry microcosm experiment, duplicate samples of the larger microcosms were sacrificed for analysis of total MeHg and other dissolved analytes. At each time point, these slurries were first mixed end-over-end and the large sediment particles were allowed to settle for 20 min. Liquid aliquots were withdrawn, filtered through 0.2 μm nylon filters, and preserved for measurements of total Hg content, sulfate, acid volatile sulfide (AVS), Fe(II), and major cations (Na+, Mg2+, K+, FeT, Mn2+, etc.). This filtration step was performed in an anaerobic chamber. The remainder of the slurry was thoroughly mixed end-over-end, partitioned into 40 mL vials, and stored at −20°C until MeHg analysis.

For the smaller-volume microcosms, GSH was spiked to a concentration of 1 mM at the same sampling time points than the corresponding larger-volume microcosms. The leachable Hg concentration was quantified using the GSH-selective extraction procedure applied to the nine MS samples (as described in the GSH selective extraction tests section).

Sequential extractions

SSEs (Bloom et al., 2003) were performed on duplicates of samples from five sites (MS-1–MS-5). These samples were chosen due to similarities in sampling location and adequate supply of sediment mass.

The SSE method entails a five-step sequence of extractions involving deionized water (F1), 0.1 M CH3COOH+0.01 M HCl (F2), 1 M KOH (F3), 12 M HNO3 (F4), and aqua regia (F5). In summary, the F1 step involved the addition of 40 mL deionized water to a vial containing 0.4 g (w.w.) sediment and mixed end-over-end for 24 h at room temperature. Samples were then centrifuged for 40 min at 3,000 g, and the supernatant was decanted. The supernatant was filtered with a 0.4 μm nitrocellulose filter (VWR), diluted in ultrapure water (1:20 dilution), and acidified with 200 μL (1% v/v) BrCl. An additional 40 mL of ultrapure water was added to the vial with decanted sediment and mixed for 10 min. The supernatant was extracted by centrifugation/filtration and preserved with BrCl (1% v/v). The supernatants of the two deionized water extracts were combined for Hg analysis and are referred to as the F1 fraction. The sediment sample was then sequentially subjected to the next extraction solvents (F2, F3, F4, and F5) using the same reagent volume, mixing time, and extraction procedure. The F3 extracts, which comprised diluted KOH, were preserved with a larger concentration of BrCl (10% v/v) to ensure acidification.

Chemical analysis

Detailed descriptions of the analysis methods are in the Supplementary Data section. In summary, the concentration of total mercury (THg) in liquid samples was quantified by stannous chloride reduction, gold amalgamation, and cold vapor atomic fluorescence spectrometry (CVAFS) (Gill and Fitzgerald, 1987). For THg concentrations in sediments, the samples were first digested in hot aqua regia followed by analysis with CVAFS. Methylmercury in sediment was extracted by acid-dichloromethane leaching and aqueous back extraction (Cai et al., 1996) and analyzed by ethylation, gas chromatographic separation, pyrolysis, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (BrooksRand MERX and Agilent 7700). The measured MeHg concentration value was corrected based on extraction efficiencies of an Me201Hg internal standard that was spiked into the samples before the initial extraction step. Other supplementary constituents were also measured in the filtered microcosm water. These include sulfate concentration, dissolved Fe(II) via colorimetry, major cations, and AVS.

For the analysis of GSH in filtered slurry water, 1 mL of sample was preserved with 100 μL of 2.0 mM 2-2-dithiobis(5-nitropyridine) (DTNP) in acetonitrile and 50 μL of 0.5 M sodium acetate (pH adjusted to 6) to form a stable disulfide derivative (Vairavamurthy and Mopper, 1990). The derivatized GSH samples were measured within 48 h using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Varian, Alltech Altima C18 Column) coupled with UV absorbance detection, as previously described (Vairavamurthy and Mopper, 1990; Hsu-Kim, 2007).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the SciPy package in the Python programming language (Jones et al., 2001). Normality of the data was calculated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Non-normal data (as determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test, i.e., p-value above 0.01) were transformed using natural logarithms for the correlation calculations. Relationships between sediment MeHg concentration, total sediment mercury, GSH leachable mercury, and other transformations of these variables were investigated and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. Relationships were considered significant at p<0.05.

Results and Discussion

Development of GSH extraction protocol

The first series of leaching experiments indicated that the amount of GSH-extractable Hg depended on the sediment–water ratio and the extraction time. For the mixtures of 2 and 8 g of sediment added to 10 mL of degassed synthetic seawater, the maximum leachable Hg concentrations were observed at the 0.5 h time point (Fig. 1A). At later time points (1.5 and 3 h) in these samples, the leachable mercury concentrations decreased. For samples containing 1 g of sediment added to 10 mL of degassed synthetic seawater, there was an increase in leachable Hg concentrations throughout the experiment.

FIG. 1.

Glutathione (GSH)-leachable Hg results for sediments mixed in N2-purged synthetic sweater and spiked with 1 mM GSH. (A) MS-4 sediment sample subjected to three different amounts of sediment for the same volume of seawater (10 mL); (B) Three different sediment samples (1 g) mixed with 10 mL of the GSH-seawater extractant for a wider time frame.

The data in Fig. 1A generally showed that increases in sediment–water ratio resulted in lower leachable Hg concentrations. This observation could be caused by sorption of the dissolved Hg-GSH complexes to the sediment. Likewise, dissolved GSH could be sorbing to sediment particles and/or consumed by the native microorganisms. These processes would result in less dissolved GSH available to induce dissolution of Hg. For the purposes of establishing a single GSH-extraction protocol to all of the sediment samples, we chose a sediment-to-water ratio of 1 g of sediment to 10 mL of seawater as a condition to maximize the leachable Hg concentration.

Further experiments to assess the importance of GSH reaction time (from 0.5 to 168 h) indicated that the change in GSH-extractable Hg concentration with time varied between the three sediments tested (MS-1, -4, and -5 shown in Fig. 1B). For the MS-1 and MS-5 sample, the leachable Hg concentrations increased and then decreased with time, while in the MS-4 sample the leachable Hg concentration appeared to decrease over all time points except the last one at 168 h. Moreover, the peak in leachable Hg concentration for MS-5 occurred at 96 h, and this time point corresponded to minimal leachable Hg contents for MS-1 and MS-4 sediments.

The dissolved GSH concentrations in the mixtures shown in Fig. 1B were less than the detection limit of 2.5 μM at 3 h of leaching time, indicating that at least 99% of the added GSH (1 mM) was not in the dissolved phase. In addition, in tests to assess the sorption of Hg-GSH complexes to sediments, after 3 h the concentration of Hg (added as 2 nM Hg-GSH complexes) had dropped to 0.5 nM, indicating adsorption of Hg-GSH complexes to the sediment. Collectively, these results and the data shown in Fig. 1B indicated that the addition of GSH to the sediment-seawater mixtures resulted in fast desorption or dissolution of Hg followed by re-sorption of Hg-GSH complexes over the experimental time frame. Furthermore, excess GSH was likely consumed by microorganisms in the microcosms or sorbing to the sediments, particularly over multiple days of mixing. Because of these interfering factors, a short reaction time of 0.5 h was chosen for comparisons of all nine sediment samples and for the microcosm experiments.

Assessment of GSH selective extraction as an indicator of bioavailability in sediments

A single GSH-leachable Hg protocol (1 g of sediment to 10 mL of seawater, 0.5 h leaching time) was applied to the MS-1–MS-9 samples. These nine sediment samples contained a range of total Hg concentrations (from 1.7 to 85 mg/kg) and MeHg concentrations (from 141 to 1,220 ng/kg), as shown in Table 1. Data normalization was carried out after thorough analysis of the data (e.g., GSH leachable Hg, sediment MeHg contents) using the Shapiro–Wilkes test and quantile-quantile (q-q) plots (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). The results indicated that the data were normally distributed if log transformed; thus, transformed data were used for all correlations (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Table 1.

Total Mercury, Methylmercury, and Selective Extraction Concentrations for Both GSH extraction and SSE Methods Applied to Nine Sediment Samples from the Same Water Body in a Marine Location

| Site | Wet:dry mass ratio | Total Hg (μg/g) | MeHg (pg/g) | % Total Hg as MeHg | GSH leachable Hg (ng/g) | % Total Hg as GSH-leachable | % of SSE-extractable Hg in F3 fraction | % Total Hg in F3 fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2 | 3 | 3 | — | 2 | — | 2 | 2 |

| MS-1 | 1.34 | 12.2 (5.9) | 194 (27) | 0.0016 | 8.4 (1.5) | 0.07 | 10.1 (4.8) | 1.91 |

| MS-2 | 1.18 | 15.8 (3.8) | 991 (520) | 0.0063 | 34.6 (0.5) | 0.22 | 1.8 (0.3) | 1.52 |

| MS-3 | 1.12 | 52.6 (9.2) | 572 (300) | 0.0011 | 19.7 (2.1) | 0.04 | 10.4 (2.3) | 1.37 |

| MS-4 | 1.28 | 16.7 (2.8) | 488 (63) | 0.0029 | 26.2 (0.8) | 0.16 | 1.8 (0.5) | 3.13 |

| MS-5 | 1.43 | 85 (22) | 775 (36) | 0.0009 | 31.3 (4.1) | 0.04 | 14.4 (5.3) | 2.00 |

| MS-6 | 1.30 | 1.7 (1.1) | 327 (16) | 0.0190 | 22.0 (0.4) | 1.28 | — | — |

| MS-7 | 1.19 | 20.8 (4.1) | 508 (72) | 0.0024 | 49.0 (7.5) | 0.24 | — | — |

| MS-8 | 1.12 | 78 (38) | 404 (27) | 0.0005 | 19.0 (2.2) | 0.02 | — | — |

| MS-9 | 1.41 | 33.7 (3.1) | 1215 (339) | 0.0036 | 127.0 (63.3) | 0.38 | — | — |

Standard deviation values for measured parameters are shown in parentheses.

GSH, glutathione; MS, marine sediment; SSE, selective sequential extraction.

FIG. 2.

Correlations between (A) methylmercury (MeHg) and the GSH-leachable Hg concentrations; (B) the fractions of total mercury as MeHg and GSH-leachable for sediments obtained from a marine location (MS-1–MS-9 shown in Table 1); and (C) the fraction of total Hg extracted by selective sequential extraction (SSE) that was observed in the F3 fraction for MS-1–MS-5 samples. Linear correlation lines and r2 value were calculated for log-transformed data. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

The GSH-leachable Hg measurements for these nine samples positively correlated with the ambient MeHg concentrations in the corresponding sediments (Fig. 2A) (r2=0.70, p=0.005). The sediments also had large differences in the total mercury concentration. Thus, the MeHg and GSH-leachable Hg values were normalized to the total Hg concentrations, and the resulting correlation, shown in Fig. 2B, was improved (r2=0.91, p<10−4).

The amount of MeHg in the sediment did not correlate (r2=0.17, p=0.27) with the concentration of total Hg (Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating that the sediments differed in mercury speciation and/or biological activity. In addition, there was no significant correlation between the GSH-leachable Hg concentration and total Hg (r2=0.03, p=0.65) (Supplementary Fig. S3), further demonstrating that mercury speciation in the tested sediments varied considerably.

Previous researchers have used the solid–water Hg partition ratio KD, which is used as a proxy for Hg bioavailability (Hammerschmidt and Fitzgerald, 2004), but in our study we did not observe a correlation between KD values and MeHg concentration. The comparisons yielded insignificant correlations if the aqueous fraction for the KD measurement was defined by centrifugation at 6,700 g for 5 min (r2=0.03, p=0.47) and also by ultracentrifugation (r2=0.003, p=0.96). The “native” dissolved Hg concentrations in the samples were generally 102–104 times less than the GSH-leachable Hg concentration (depending on the centrifugation method). We note, however, that the sample number for this comparison was small (n=4) and the fractionation methods for our study (centrifugation and ultracentrifugation) differ from other studies that separated samples with a 0.2 or 0.45 μm filter. Overall, the lack of correlations as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3 [and also in our previous study (Zhang et al., 2014)] indicated that sediment total and porewater Hg concentrations were not adequate predictors of mercury bioavailability and methylation potential in sediments.

Selective sequential extraction

The results of the sequential extractions (Fig. 3) indicated that the majority of the mercury present in tested sediments resided in fractions F4 and F5 (nitric acid and aqua regia, respectively). These fractions typically correspond to particulate, non-labile species such as HgS(s) (Bloom et al., 2003). The relative Hg concentrations extracted in fraction F3 were plotted versus percent of total Hg as MeHg (Fig. 2C), resulting in a negative trend (r2=0.85, p=0.026). A similar comparison with the combination of F1+F2+F3 also yielded a negative, but statistically insignificant correlation (r2=0.72, p=0.07; Supplementary Fig. S4). This result was the direct opposite of the observations reported in previous research by Bloom et al. (2003) in which the % of extractable Hg in the F3 fraction positively correlated with the % as MeHg. This discrepancy could be due to the low values of the F3 fraction determined for the samples in our study: All were less than 10% of the total Hg and were near the low end of the range observed by Bloom et al. (between 0% and 80%). In the Bloom et al. study, several samples were clustered at the low range of F3 values (i.e., less than 10%), which could improve the overall correlation coefficient without strongly fitting each of the samples in the lower range.

FIG. 3.

Fractionation of Hg based on SSE (Bloom et al., 2003) for MS-1–MS-5 marine sediment (MS) samples.

We also note that the total extractable Hg by the SSE method (i.e., F1+F2+F3+F4+F5) did not correspond to the total Hg concentration quantified by an independent method (aqua regia acid digestion at 90°C). The SSE recoveries varied from 13% to 170% of the total Hg (Fig. 3). This discrepancy is likely caused by incomplete extraction of Hg during the SSE method, and perhaps incomplete dissolution of Hg at the last F5 step that involved aqua regia digestion at room temperature. Another possible contribution to the discrepancy is sample heterogeneity—the relative standard deviation of total Hg concentrations ranged from 15% to 50% in triplicate aliquots of the same sediment sample (Table 1). Nevertheless, in a comparison of the percentage of F3 (normalized to total Hg, not SSE-extractable Hg) to the relative amount of MeHg, the resulting correlation was insignificant (r2=0.02, p=0.80).

The combined results of our SSE experiments and those of Bloom et al. (2003) indicate that a broad range of F3 fractions may be required to obtain an overall parameter correlation. For the sediments in our study, the SSE approach did not provide a strong indicator of mercury bioavailability in sediments. More importantly, there were analytical challenges in selective extraction procedure that resulted in incomplete recovery of total Hg from sediment samples, and this could signify that the reagent mixtures for the SSE method need to be modified for different sample characteristics. In addition, there are a number of difficulties that make the SSE approach less desirable, including a long experimental time (5 days), the extractant media complexity (strong acids and bases), and the fact that the dissolution of Hg in 1 N KOH (fraction F3) does not have a strong link to the processes that cause sediment-bound Hg to be bioavailable to methylating microorganisms.

Mercury bioavailability and methylation in sediment slurry microcosms

The GSH leachability test with the sediment samples indicated that this approach may provide a simplified and more reliable approach for assessing bioavailable mercury in sediments. However, MeHg concentrations in sediments reflect simultaneous methylation and demethylation processes and do not necessarily depend solely on Hg bioavailability. Thus, we performed additional anaerobic sediment slurry microcosm experiments in which the microbial community (i.e., methylators and demethylators) was controlled under varying levels of Hg bioavailability.

The microcosm experiments with MS-6 sediments resulted in trends of MeHg production that were consistent with our previous work (Zhang et al., 2014). The net MeHg production in the microcosms varied based on the form of Hg added (dissolved, HgS nanoparticles and microparticles), as shown in Fig. 4. Concentrations of MeHg in slurries amended with dissolved and nanoparticulate HgS were 6.5 and 3.5 times higher than in the Hg blank controls. There was no significant increase in the net MeHg production in slurries amended with HgS microparticles relative to the Hg blank, indicating that the ambient mercury in the sediments was not labile.

FIG. 4.

Net production of methylmercury (MeHg) in anaerobic MS-6 sediment slurries amended with 2 μg/g mercury as dissolved Hg, HgS nanoparticles, or HgS microparticles. The error bars represent the range for duplicate biological samples. The molybdate control was spiked with 2 μg/g dissolved Hg. Anaerobic slurries were held static in the dark at room temperature until sampling.

In slurries treated with molybdate, the MeHg concentration after 7 days was similar to the mercury blank and was only 10% of the MeHg concentrations in slurries with the same mercury addition (i.e., dissolved Hg). Molybdate is a sulfate reduction inhibitor that can limit the growth of sulfate reducers (Compeau and Bartha, 1985; King et al., 1999). However, the addition of molybdate did not decrease sulfate reduction rates (Supplementary Fig. S5) and perhaps even increased the sulfide production rate (Supplementary Fig. S6). Thus, the methylating community cannot be conclusively identified for this experiment.

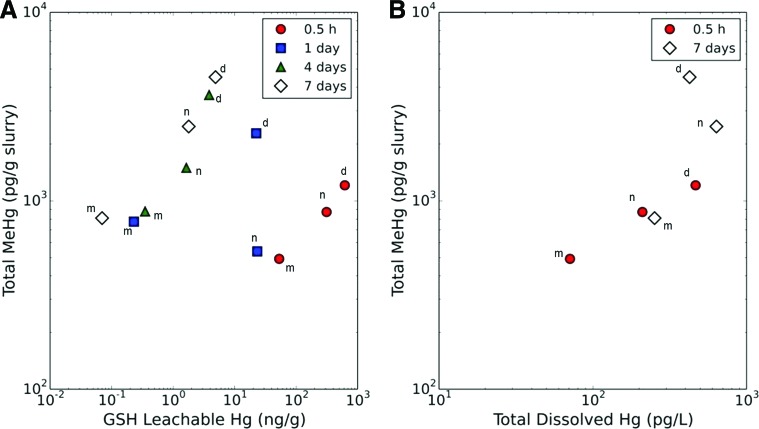

GSH-leachable Hg concentrations at most sampling time points during the incubation (i.e., 0.5 h, 4 and 7 days) corresponded with the type of Hg added and the MeHg concentration (Fig. 5A). 0.5 h after the Hg amendment, less than 1% of the added mercury remained in the dissolved fraction (i.e., passing through a 0.2 μm filter), suggesting that the added dissolved and nanoparticulate HgS had readily adsorbed to or aggregated with the sediment particles. The MeHg concentration at three time points increased with the GSH-leachable concentration of Hg at the given time (Fig. 5A). An exception to this trend was observed with the 1-day time point, corresponding to a nanoparticulate HgS-amended slurry. This observation is likely the result of a loss in anaerobic conditions in this microcosm, which was suggested by a slight pink hue of oxidized resazurin in the slurry microcosm. In addition, the GSH-leachable Hg concentration appeared to decrease with incubation time for each type of Hg treatment (Fig. 5A). This trend indicated that the Hg speciation changed during the microcosm incubation and perhaps that Hg bioavailablity for methylation was decreasing with time.

FIG. 5.

Relationship between MeHg concentration in sediment slurries and (A) GSH-leachable mercury content; (B) total dissolved Hg concentrations (i.e., passing through a 0.2 μm filter) in the slurries for each incubation time point. Slurries were prepared with a ratio of 2.5 mL synthetic seawater per g of sediment (w.w.). Each set of symbols corresponds to measurements at a given time. Individual data points are labeled for the type of Hg that was added to the slurry: dissolved Hg (d), nanoparticulate HgS (n), and microparticulate HgS (m).

Slurries amended with dissolved Hg resulted in higher final concentrations of dissolved Hg (defined by passing through a 0.2 μm filter) than those amended with HgS nanoparticles, HgS microparticles, and the Hg blank controls (Fig. 5B). However, less than 1.59 ng/g of total mercury added to the slurries was quantified in the filtered supernatant of the microcosms. In other words, more than 99% of the added Hg had aggregated, sorbed to sediment particles, or sorbed to the container regardless of the type of mercury added. The amount of dissolved Hg in slurries did correlate with the MeHg concentration at 0.5 days (Fig. 5B, p=0.04), but no correlation was observed at 7 days (Fig. 5B, p=0.58). Moreover, the mass of dissolved Hg per g of sediment in the slurry was 102–105 less than the GSH-extractable Hg concentration in the same respective slurry. Collectively, this result indicated that the dissolved Hg concentration was insufficient for explaining differences in net MeHg production between the slurries with HgS nanoparticles and dissolved mercury added. However, the use of only two time points does not allow for sufficient deduction of overall trends.

One possible explanation for rapid sorption of dissolved mercury or aggregation of nanoparticulate mercury to large particles is the presence of other metal sulfides, such as iron sulfide, at relatively higher concentrations than mercury. The dissolved sulfate concentration was ∼20 mM in the microcosm samples and did not change measurably during the incubation (Supplementary Fig. S5). The AVS concentrations in the filtered supernatant were observed to increase from levels that were below detection (<0.1 μM) immediately after Hg was added to the microcosms and increased to concentrations of 0.55–7.1 μM after 7 days (Supplementary Fig. S6). This result indicated some degree of sulfide production that would be available to precipitate with metals such as Fe.

Fe(II) concentrations in filtered slurry water (Supplementary Fig. S7) showed a decline with time for each of the slurry amendments. Measurements of Fe(II) could not be made in samples containing molybdate due to interferences in the measurement method. In addition to the decline in dissolved ferrous iron, a noticeable surficial black layer was present atop the sediment, indicating formation of iron sulfide precipitates. Iron likely controlled sulfide speciation, leading to possible changes in dissolved Hg speciation and mercury bioavailability. Thus, the use of dissolved Hg concentration in the<0.2 μm filtered fraction of porewater may not be an appropriate measure of bioavailable mercury, as shown in other studies (Hsu-Kim et al., 2013).

Environmental implications

Quantification of bioavailable mercury in sediments is a vital step in assessing the Hg methylation potential at field sites. Our proposal to use a GSH selective extraction method is the first one to be grounded in the fundamental mechanisms of bioavailability (i.e., the presence of thiols in solution coincided with Hg uptake by methylating organisms). However, we recognize that the extraction method involved a relatively short reaction time with GSH (30 min) that may be short relative to time scales relevant for Hg bioavailability and microbial uptake. Nevertheless, results of the experiments indicated that GSH-extractable Hg measurements may be a good approximation for bioavailability. These results included a correlation between GSH-leachable Hg concentrations and MeHg concentrations in sediments from a similar site and also consistent patterns in microcosm studies using well-defined mercury species that have distinct methylation potentials. The overall results suggest that reactivity with GSH could be used as a proxy for bioavailable mercury in sediments.

GSH-leachable Hg and MeHg concentrations in nine natural sediments showed a statistically significant correlation. However, it must be noted that this approach was only tested on a small selection of sediments from the same marine location. Further analysis is required to see whether a single correlation plot can be observed across several types of environments and ranges of total Hg and MeHg concentrations. We hypothesize that this correlation is not likely to hold as more sites are compared and as the activity of microorganisms that produce and degrade MeHg varies greatly between settings. These processes also influence the observed MeHg concentrations in sediments. Additional work could also involve controlled microcosm experiments that test more types of Hg with a wider range of methylation potentials. Further work should also address the physical explanation for the observed correlation, particularly in regards to the mechanism(s) by which GSH leaches Hg from sediments. An understanding of why dissolved GSH was decreasing over time in the sediment mixtures would better inform the applicability of the method in diverse environments.

Despite some shortcomings, the GSH selective extraction approach may provide a starting point for evaluating Hg bioavailability in sediments. The GSH extraction method in its current form could be used for comparing areas with similar microbial activity or redox potential at the same geographic location. This information could be used to prioritize remediation efforts. The ability to rank impacted sites would enable engineers to prioritize large-scale remediation projects where treatment of all sites is infeasible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.L.T. was supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science Graduate Fellowship Program (DOE SCGF), made possible in part by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, and administered by ORISE-ORAU under Contract No. DE-AC05-06OR23100. This work was also supported in part by the U.S. Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (ER-1744), the Department of Energy Early Career Scientist program (DE-SC0006938), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES024344).

Supplementary Data

The supplementary data contain additional data plots and statistical analyses.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Benoit J.M., Gilmour C.C., Mason R.P., and Heyes A. (1999a). Sulfide controls on mercury speciation and bioavailability to methylating bacteria in sediment pore waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 951 [Google Scholar]

- Benoit J.M., Mason R.P., and Gilmour C.C. (1999b). Estimation of mercury-sulfide speciation in sediment pore waters using octanol-water partitioning and implications for availability to methylating bacteria. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 18, 2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom N.S., Preus E., Katon J., and Hiltner M. (2003). Selective extractions to assess the biogeochemically relevant fractionation of inorganic mercury in sediment and soils. Anal. Chim. Acta 479, 233 [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Jaffé R., Alli A., and Jones R.D. (1996). Determination of organomercury compounds in aqueous samples by capillary gas chromatography-atomic fluorescence spectrometry following solid-phase extraction. Anal. Chim. Acta 334, 251 [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson T.W. (1997). The toxicology of mercury. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 34, 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson T.W. (2002). The three modern faces of mercury. Environ. Health Perspect. 110, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compeau G.C., and Bartha R. (1985). Sulfate-reducing bacteria: Principal methylators of mercury in anoxic estuarine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50, 498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deonarine A., and Hsu-Kim H. (2009). Precipitation of mercuric sulfide nanoparticles in NOM-containing water: Implications for the natural environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drott A., Lambertsson L., Bjorn E., and Skyllberg U. (2007). Importance of dissolved neutral mercury sulfides for methyl mercury production in contaminated sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham-Cheatham S., Farrell B., Mishra B., Myneni S., and Fein J.B. (2014). The effect of chloride on the adsorption of Hg onto three bacterial species. Chem. Geol. 373, 106 [Google Scholar]

- Dunham-Cheatham S., Mishra B., Myneni S., and Fein J.B. (2015). The effect of natural organic matter on the adsorption of mercury to bacterial cells. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 150, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Fleming E.J., Mack E.E., Green P.G., and Nelson D.C. (2006). Mercury methylation from unexpected sources: Molybdate-inhibited freshwater sediments and an iron-reducing bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbig C.A., Kim C.S., Stegemeier J.P., Ryan J.N., and Aiken G.R. (2011). Formation of nanocolloidal metacinnabar in mercury-DOM-sulfide systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G.A., and Fitzgerald W.F. (1987). Picomolar mercury measurements in seawater and other materials using stannous chloride reduction and two-stage gold amalgamation with gas phase detection. Mar. Chem. 20, 227 [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour C.C., Podar M., Bullock A.L., Graham A.M., Brown S.D., Somenahally A.C., Johs A., Hurt R.A., Jr., Bailey K.L., and Elias D.A. (2013). Mercury methylation by novel microorganisms from new environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 11810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A.M., Aiken G.R., and Gilmour C.C. (2012a). Dissolved organic matter enhances microbial mercury methylation under sulfidic conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A.M., Bullock A.L., Maizel A.C., Elias D.A., and Gilmour C.C. (2012b). A detailed assessment of the kinetics of Hg-cell association, Hg methylation, and MeHg degradation in several Desulfovibrio species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt C.R., and Fitzgerald W.F. (2004). Geochemical controls on the production and distribution of methylmercury in near-shore marine sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol 38, 1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu-Kim H. (2007). Stability of metal-gluathione complexes during oxidation by hydrogen peroxide and Cu(II)-catalysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu-Kim H., Kucharzyk K.H., Zhang T., and Deshusses M.A. (2013). Mechanisms regulating mercury bioavailability for methylating microorganisms in the aquatic environment: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H., and Sedlak D.L. (2003). Strong Hg(II) complexation in municipal wastewater effluent and surface waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Lin H., Zheng W., Rao B., Feng X., Liang L., Elias D.A., and Gu B. (2013). Mercury reduction and cell-surface adsorption by Geobacter sulfurreducens PCA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 10922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe-Wong C., Shoenfelt E., Hauser E.J., Crompton N., and Myneni S.C.B. (2012). Estimation of reactive thiol concentrations in dissolved organic matter and bacterial cell membranes in aquatic systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 9854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E., Oliphant T., and Peterson P. (2001). SciPy: Open Source Scientific Tools for Python. Available at www.scipy.org

- Kim C.S., Bloom N.S., Rytuba J.J., and Brown G.E. (2003). Mercury speciation by X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy and sequential chemical extractions: A comparison of speciation methods. Environ. Sci. Technol 37, 5102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J.K., Saunders F.M., Lee R.F., and Jahnke R.A. (1999). Coupling mercury methylation rates to sulfate reduction rates in marine sediments. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 18, 1362 [Google Scholar]

- Liang L., Horvat M., Alvarez J., Young L., Kotnik J., and Zhang L. (2013). The challenge and its solution when determining biogeochemically reactive inorganix mercury (RHg): Getting the analytical method right. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 4, 623 [Google Scholar]

- Marvin-DiPasquale M.C., Lutz M.A., Brigham M.E., Krabbenhoft D.P., Aiken G.R., Orem W.H., and Hall B.D. (2009). Mercury cycling in streem ecosystems. 2. Benthic methylmercury production and bed sediment—Pore water partitioning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt K.A., and Amirbahman A. (2009). Mercury methylation dynamics in estuarine and coastal marine environments—A critical review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 96, 54 [Google Scholar]

- Miller C.L., Mason R.P., Gilmour C.C., and Heyes A. (2007). Influence of dissolved organic matter on the complexation of mercury under sulfidic conditions. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 26, 624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham A.L.-T., Morris A., Zhang T., Ticknor J., Levard C., and Hsu-Kim H. (2014). Precipitation of nanoscale mercuric sulfides in the presence of natural organic matter: Structural properties, aggregation, and biotransformation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 133, 204 [Google Scholar]

- Reddy C.A., Beveridge T.J., Breznak J.A., and Marzluf G. (2007). Methods for General and Molecular Microbiology. Washington, DC: ASM Press [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer J.K., Rocks S.S., Zheng W., Liang L., Gu B., and Morel F.M.M. (2011). Active transport, substrate specificity, and methylation of Hg(II) in anaerobic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 8714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skyllberg U. (2008). Competition among thiols and inorganic sulfides and polysulfides for Hg and MeHg in wetland soils and sediments under suboxic conditions: Illumination of controversies and implications for MeHg net production. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeo. 113 [Google Scholar]

- Slowey A.J. (2010). Rate of formation and dissolution of mercury sulfide nanoparticles: The dual role of natural organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 4693 [Google Scholar]

- Vairavamurthy A., and Mopper K. (1990). Field methods for determination of traces of thiols in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 236, 363 [Google Scholar]

- Yu R.Q., Reinfelder J.R., Hines M.E., and Barkay T. (2013). Mercury methylation by the methanogen Methanospirillum hungatei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Kim B., Levard C., Reinsch B.C., Lowry G.V., Deshusses M.A., and Hsu-Kim H. (2012). Methylation of mercury by bacteria exposed to dissolved, nanoparticulate, and microparticulate mercuric sulfides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 6950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Kucharzyk K.H., Kim B., Deshusses M.A., and Hsu-Kim H. (2014). Net methylation of mercury in estuarine sediment microcosms amended with dissolved, nanoparticulate, and microparticulate mercuric sulfides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16, 9133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.