Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Are prospectively assessed dietary factors, including overall diet quality, macronutrients and micronutrients, associated with luteal phase deficiency (LPD) in healthy reproductive aged women with regular menstrual cycles?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS), fiber and isoflavone intake were positively associated with LPD while selenium was negatively associated with LPD after adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

LPD may increase the risk of infertility and early miscarriage. Prior research has shown positive associations between LPD and low energy availability, either through high dietary restraint alone or in conjunction with high energy expenditure via exercise, but few studies with adequate sample sizes have been conducted investigating dietary factors and LPD among healthy, eumenorrheic women.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

The BioCycle Study (2005–2007) prospectively enrolled 259 women from Western New York state, USA, and followed them for one (n = 9) or two (n = 250) menstrual cycles.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Women aged 18–44 years, with self-reported BMI between 18 and 35 kg/m2 and cycle lengths between 21 and 35 days, were included in the study. Participants completed baseline questionnaires, four 24-h dietary recalls per cycle and daily diaries capturing vigorous exercise, perceived stress and sleep; they also provided up to eight fasting serum samples during clinic visits timed to specific phases of the menstrual cycle using a fertility monitor. Cycles were included for this analysis if the peak serum luteal progesterone was >1 ng/ml and a urine or serum LH surge was detected. Associations between prospectively assessed diet quality, macronutrients and micronutrients and LPD (defined as luteal duration <10 days) were evaluated using generalized linear models adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

LPD occurred in 41 (8.9%) of the 463 cycles from 246 women in the final analysis. After adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake, LPD was positively associated with MDS, adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.70 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.17, 2.48), P = 0.01. In separate macro- and micronutrient adjusted models, increased fiber and isoflavone intake showed modest positive associations with LPD: fiber (per g), aOR: 1.10 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.23), P = 0.07; and isoflavones (per 10 mg), aOR: 1.38 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.92), P = 0.06. In contrast, selenium (per 10 mcg) was inversely associated with LPD, aOR: 0.80 (95% CI: 0.65, 0.97), P = 0.03. Additional adjustments for relevant lifestyle factors including vigorous exercise, perceived stress and sleep did not appreciably alter estimates.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

The number of LPD cycles was limited, and thus these findings are exploratory. We relied on participant self-report of their medical history to apply exclusion criteria; it is possible that we admitted to the study women with a gynecologic or medical disease who were unaware of their diagnosis.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Our study suggests that diet quality may be associated with LPD among healthy eumenorrheic women. As LPD may contribute to infertility and early miscarriage, further research is warranted to elucidate how dietary factors, such as MDS, may influence LPD. The inverse association we found with selenium is supported by previous research and deserves further investigation to determine whether this finding has pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. No competing interests declared.

Keywords: luteal phase deficiency, menstrual cycle, Mediterranean diet, fiber, selenium

Introduction

Luteal phase deficiency (LPD) refers to inadequate progesterone secretion by the corpus luteum, which may render the endometrium less receptive to implantation and result in infertility or early pregnancy loss (Arredondo and Noble, 2006; Sonntag and Ludwig, 2012; Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2015). The prevalence of LPD ranges from 4 to 9% in healthy women of reproductive age (Lenton et al., 1984; Smith et al., 1985; Schliep et al., 2014). Previous analysis has shown an association between lower mean estradiol, LH and FSH concentrations in LPD cycles compared with normal cycles (Schliep et al., 2014). The potential for an adverse impact on reproductive outcomes warrants further investigation into factors that may be associated with LPD so that preventive strategies via diet or lifestyle modifications or minimally invasive treatments might be implemented.

Several studies indicate that low energy availability, either through high dietary restraint alone (Schweiger et al., 1987; Schweiger et al., 1992) or in conjunction with high energy expenditure via exercise (Williams et al., 2001, 2015; De Souza et al., 2007), increases the risk of LPD, while limited research indicates a link between antioxidant supplementation and decreased risk of LPD and subsequent increase in clinical pregnancy rates (Henmi et al., 2003). The Mediterranean diet has been associated with several important health outcomes including reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Rees et al., 2013; Koloverou et al., 2014); however, little is known about the relationship between the Mediterranean diet and reproductive outcomes. Previous studies have also shown that diets high in fiber and/or low in fat are associated with decreased progesterone concentrations (Boyd et al., 1997; Barr, 1999; Dorgan et al., 2003); however, no previous studies have attempted to clarify whether overall diet quality or specific macro- or micronutrients are associated with LPD using standard diagnostic criteria over more than one cycle. Additionally, previous studies directly assessing dietary factors and LPD are restricted to clinical populations with known infertility, which limits generalizability (Henmi et al., 2003). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to prospectively investigate the association between dietary factors, including overall diet quality, macronutrients and micronutrients, and LPD in a population-based cohort of healthy women using gold-standard methods for both exposure and outcome assessments while accounting for important well-measured confounding factors.

Methods

Study population

The BioCycle Study was a prospective cohort study of menstrual cycle, diet and lifestyle characteristics of 259 healthy eumenorrheic women of reproductive age who were followed for one (n = 9) or two (n = 250) menstrual cycles (Wactawski-Wende et al., 2009). Study participants were recruited from premenopausal female volunteers aged 18–44 years in New York, USA, who had a self-reported cycle length between 21 and 35 days for the past 6 months, no use of oral contraceptives or oral hormonal therapy during the past 3 months, no use of parenteral hormonal contraceptives or intrauterine devices in the past 1 year, no pregnancy within the past 6 months and expressed willingness to adhere to study protocol for clinic visits and study questionnaires. Volunteers who had a chronic illness (e.g. diabetes mellitus, liver or kidney disease), had ever sought infertility treatment, had a previous diagnosis of endometriosis, polycystic ovary disease or uterine fibroids, had gynecologic surgery in the past 12 months, had an untreated gynecologic infection in the past 6 months or who planned to conceive within 3 months were excluded. Participants were also excluded if they planned to restrict their diet to lose weight in the next 3 months, were unwilling to stop regular intake of vitamin and/or mineral supplements during cycle visit months, had a history of intestinal malabsorption (e.g. Crohn's disease) or consumed a diet high in soy products.

Ethical approval

The University at Buffalo Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study and served as the IRB designated by the National Institutes of Health under a reliance agreement. All participants gave written informed consent.

Enrollment visit

At the enrollment visit, anthropometrics (including height and weight) were measured and participants completed questionnaires about age, race, marital status, education level, annual household income, age at menarche, parity, prescription hormone use and sexual activity (defined as vaginal intercourse). Participants were instructed in the use of the fertility monitor (Clearblue® Easy Fertility Monitor; Inverness Medical, Waltham, MA, USA), which was used as a validated tool to estimate ovulation (Behre et al., 2000) and coordinate clinic visits with menstrual cycle events (Howards et al., 2009). The monitor assessed urinary estrone-3-glucuronide (E3G) and LH starting on menstrual cycle day 6 and daily thereafter for 10–20 days, depending on the timing of the LH surge. Participants were given a daily diary and instructions to bring the diary to all subsequent clinic visits and to record bleeding dates, vigorous exercise (minutes/day), smoking habits (cigarettes/day), perceived stress (not stressful [1], a little stressful [2], very stressful [3]), sleep (hours/minutes, including nap time) and fertility monitor results (low, high or peak fertility indication). Vigorous exercise was defined as activities performed for at least 10 consecutive minutes which participants felt required hard physical effort and resulted in increased work of breathing.

Subsequent clinic visits

Clinic visits were scheduled between 7:30 and 8:00 a.m. to minimize diurnal variability in hormone measurements and corresponded to the following phases of the menstrual cycle: menses, mid-follicular, late follicular, LH surge, expected ovulation and early, mid- and late luteal phases. Initial visits were scheduled using an algorithm that adjusted for self-reported cycle length; mid-cycle visit schedules were adjusting using the fertility monitor results. The peak fertility day as indicated by the monitor was used for the late follicular phase visit and the following 2 days for the LH surge and ovulation visits. At each visit, fasting blood samples were taken (with serum stored at −80°C within 90 min of collection), daily diaries were reviewed, and fertility monitor data were downloaded. At the end of the follow-up period, body composition was determined with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scans (software version 12.4.1; Hologic Discovery Elite, Waltham, MA, USA) and total percentage body fat was derived.

Hormone measurements

Serum progesterone and LH concentrations were measured by solid-phase chemiluminescent enzymatic immunoassay on the DPC IMMULITE® 2000 analyzer (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL, USA) at Kaleida Health Laboratories, Buffalo, NY, USA. Reported coefficients of variation were <5% for LH and <14% for progesterone.

Dietary assessment

Participants completed a 24-h dietary recall (24HDR) during the clinic visits corresponding to menstruation, the mid-follicular phase, estimated day of ovulation and the mid-luteal phase for a total of up to eight 24HDRs over two cycles. Previous studies have confirmed the use of 24HDR as a valid measurement of dietary exposures (Patterson et al., 1999; Schatzkin et al., 2003; Subar et al., 2003). Food and beverage intakes (including caffeinated beverages and alcohol) were collected and nutrient data were analyzed by using the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR; version 2005; Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota) (Schakel et al., 1988). Trained dietary interviewers, using open-ended questions and visual amount-estimation tools, captured food and beverage quantities consumed. The NDSR takes into account food and beverage type, brand (when necessary) and serving size in calculating nutrient information. Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS) (Gaskins et al., 2010), food and beverage components and macronutrients/micronutrients were calculated for each dietary assessment.

LPD assessment

Cycles were included in this analysis if cycle length was not missing and if the cycles were ovulatory, which we defined as any cycle with progesterone >1 ng/ml that was preceded by a urine LH surge detected by the home fertility monitor and/or a serum LH surge. We selected the cutoff of 1 ng/ml based on experimental models of LPD that indicate that the minimum progesterone concentration required to sustain endometrial maturation may be lower than previously thought (Usadi et al., 2008; Fritz and Speroff, 2011). Prior validation research comparing the Clearblue® Easy Fertility Monitor with transvaginal ultrasonography has shown that, in most cycles, ovulation occurs on the day after the peak day as indicated by the monitor (Behre et al., 2000). Consequently, the day of ovulation was assigned using the day of the urine LH surge from the fertility monitor, or the day of the serum LH maximum value when fertility monitor data were not available, plus 1 day. The luteal phase was defined as beginning on the day after ovulation and ending on the day prior to the start of the next menses. LPD was defined as luteal phase duration <10 days, as this definition provides reasonable overlap with definitions that include measurements of peak luteal progesterone ≤10 ng/ml and is clinically easier to measure (Jones, 2008; Sonntag and Ludwig, 2012; Schliep et al., 2014). Nevertheless, we also included a sensitivity analysis using a combined definition of LPD: luteal length <10 days and peak luteal progesterone ≤10 ng/ml (Jordan et al., 1994; Malcolm and Cumming, 2003).

Statistical analysis

Participant demographic and lifestyle characteristics, averaged over the study, were compared by LPD status (zero, one or two LPD cycles) with Student's t-test or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test and χ2 or Fisher's exact tests used to evaluate differences. Associations between cycle-average dietary factors and LPD were examined using generalized linear models (taking into account multiple cycles from the same woman) while adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake. Reported P-values are differences in mean levels between LPD cycles versus normal cycles, with non-normally distributed dietary factors log transformed prior to statistical analysis. Variables that showed marginally significant associations (P<0.15) in the bivariate analysis were selected for inclusion in one of three multivariable models: the first examining overall diet quality; the second, macronutrients and the third, micronutrients. All models were adjusted for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake.

We examined the possibility of a nonlinear relationship or threshold effect between dietary factors and LPD in two ways: (i) non-parametrically with restricted cubic splines, adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake (Durrleman and Simon, 1989); and (ii) generating quartiles and calculating P values for trend by taking the median value of the quartiles and analyzing as a continuous variable via the adjusted generalized linear models. Finally, sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of our findings by (i) adjusting for additional potential confounding factors including race, education, previous hormonal contraceptive use, smoking, vigorous exercise, sleep and perceived stress; and (ii) using a more stringent definition of LPD as previously described (luteal duration <10 days and peak luteal progesterone ≤10 ng/ml) (Schliep et al., 2014). Analyses were completed in Stata /IC 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SAS, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the 476 cycles with menstrual cycle length information from the 259 study participants, there were 13 cycles (2.7%) from 13 women (5.0%) considered anovulatory, based on luteal progesterone measurements <1 ng/ml. These were excluded from our analyses, leaving 246 women contributing 463 cycles. Compliance with study protocol was excellent, with 94% of women completing at least seven visits per cycle, 100% of women completing at least five visits per cycle and 84% of women having complete fertility monitor data for two cycles. All of the covariates assessed had at least a 95% response rate. The average age of study participants was 27.6 years (SD, 8.2 years; range, 18–44 years). Sixty percent of participants self-identified as white, 20% as black, 13% as Asian and 7% as other race. Most participants were unmarried (74%) and had completed high school (88%). Age, sexual activity and hormonal contraceptive use prior to study entry were inversely associated with LPD while vigorous exercise was positively associated with LPD (all P < 0.05, Table I).

Table I.

Characteristics of women by number of LPD cycles.1

| Women with normal cycles | Women with at least one LPD cycle | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women (n [%]) | 213 (86.6) | 33 (13.4) | Na |

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 28.1 (8.2) | 24.8 (7.9) | 0.04 |

| <20 (n [%]) | 24 (75.0) | 8 (25.0) | 0.11 |

| 20–24 (n [%]) | 76 (84.4) | 14 (15.6) | |

| 25–29 (n [%]) | 36 (90.0) | 4 (10.0) | |

| 30+ (n [%]) | 77 (91.7) | 7 (8.3) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 121 (82.3) | 26 (17.7) | 0.03 |

| Black | 47 (95.9) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Asian | 28 (84.9) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Other | 17 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean [SD]) | 24.2 (3.9) | 23.8 (3.6) | 0.62 |

| Underweight (<18.5) (n [%]) | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.17 |

| Normal (≥18.5 to <25) (n [%]) | 126 (83.4) | 25 (16.6) | |

| Overweight (≥25 to <30) (n [%]) | 58 (93.6) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Obese (≥30) (n [%]) | 21 (84.0) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Percentage body fat (mean [SD]) | 29.9 (6.1) | 27.6 (5.0) | 0.05 |

| High school graduate or more (n [%]) | 184 (85.2) | 32 (14.8) | 0.09 |

| Annual household income (n [%]) | |||

| <$19 999 | 50 (94.3) | 3 (5.7) | 0.14 |

| $20 000–39 999 | 53 (88.3) | 7 (11.7) | |

| $40 000–74 999 | 56 (81.2) | 13 (18.8) | |

| $75 000–99 999 | 36 (90.0) | 4 (10.0) | |

| $100 000+ | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Sexually active (n [%]) | |||

| Ever | 171 (90.5) | 18 (9.5) | 0.002 |

| Never | 42 (73.7) | 15 (26.3) | |

| Marital status (n [%]) | |||

| Single | 154 (85.1) | 27 (14.9) | 0.25 |

| Married | 59 (90.8) | 6 (9.2) | |

| Age at menarche (years) (mean [SD]) | 12.4 (1.3) | 12.6 (1.1) | 0.37 |

| Parity (n [%]) | |||

| Nulliparous | 152 (84.4) | 28 (15.6) | 0.10 |

| Parous | 61 (92.4) | 5 (7.6) | |

| OC use, ever (n [%]) | |||

| Ever | 122 (90.4) | 13 (9.6) | 0.05 |

| Never | 89 (84.7) | 20 (18.4) | |

| Smoking (n [%]) | |||

| None | 170 (85.4) | 29 (14.6) | 0.69 |

| <1 cigarette/day | 33 (91.7) | 3 (8.3) | |

| ≥1 cigarette/day | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Vigorous exercise (minutes) (median [IQR]) | 8.5 (1.4, 17.4) | 15.1 (2.9, 33.1) | 0.02 |

| Sleep per day (h) (mean [SD]) | 7.4 (0.9) | 7.6 (0.9) | 0.25 |

| Perceived stress tertile (n [%]) | |||

| Low | 74 (35) | 8 (24) | 0.39 |

| Moderate | 71 (33) | 11 (33) | |

| High | 68 (32) | 14 (42) | |

LPD: defined as luteal phase duration <10 days. Continuous variables are shown as mean ± SD (unless noted otherwise) and comparison between groups was made using Student's t-test or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test where appropriate. Categorical variables are shown as number (percentage) and associations were assessed using χ2 or Fisher's exact test.

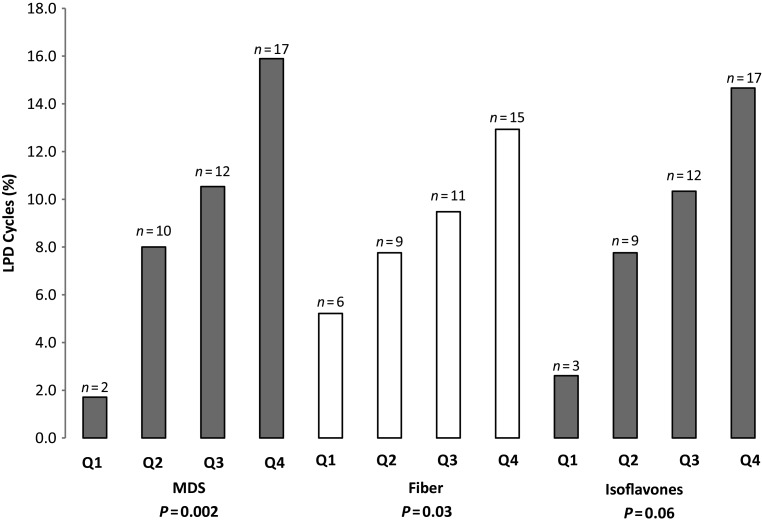

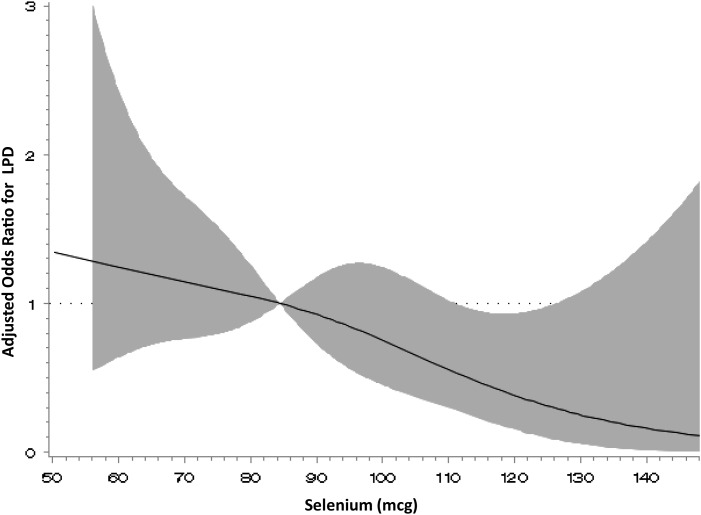

Of the 463 cycles, 41 (8.9%) met criteria for LPD (Table II). Higher MDS was observed for LPD cycles compared with normal cycles (3.5 versus 2.8, P = 0.01, Table II) after adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake. Higher intakes of vegetable protein (24.5 versus 21.2 g, P = 0.03) and fiber (16.7 versus 13.2 g, P = 0.001) were also observed in LPD cycles after adjustment, as were higher servings of fruits and vegetables, and higher isoflavone and vitamin B6 intake in LPD cycles as well (P = 0.05 for all, Table II). Higher iron intake was marginally associated with LPD (P = 0.07, Table II). Vitamin and antioxidant intake, except in the case of selenium, tended to be higher in LPD cycles than during normal cycles after adjustment, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, selenium consumption was higher in normal cycles than in LPD cycles (89.3 versus 81.8 mcg, P = 0.05). Additional adjustment for demographic and lifestyle factors including race, education, previous hormonal contraceptive use, smoking, vigorous exercise, sleep and perceived stress did not appreciably alter the estimates. Using restricted cubic spline regression, there was no evidence of significant nonlinearity between dietary factors and LPD. The adjusted trend analyses for significant diet quality and macronutrients revealed an apparent positive linear relationship for MDS (P = 0.002), fiber (P = 0.03) and isoflavone (P = 0.06) quartiles and LPD (Fig. 1). Selenium showed an inverse relationship with LPD (Fig. 2); however, a significant inverse association with LPD was only seen at intakes >110 mcg.

Table II.

Dietary characteristics of women by LPD cycles.1

| Luteal phase duration |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 days | ≥10 days | P | |||

| Number of cycles (n [%]) | 41 (8.9) | 422 (91.1) | na | ||

| Diet quality | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | |

| Mediterranean diet score | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.3 (2.8, 4.3) | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.8 (2.0, 3.5) | 0.01 |

| Macronutrients | |||||

| Fat (g) | 61.1 ± 17.7 | 57.7 (48.2, 71.0) | 62.5 ± 22.2 | 61.2 (47.1, 73.0) | 0.93 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 20.3 ± 6.9 | 19.5 (15.9, 24.6) | 21.5 ± 8.6 | 20.4 (15.9, 26.5) | 0.74 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 22.9 ± 7.5 | 21.4 (17.2, 27.7) | 23.0 ± 8.5 | 22.3 (17.5, 27.6) | 0.72 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g) | 13.0 ± 4.6 | 12.3 (9.7, 16.1) | 12.9 ± 5.4 | 12.1 (9.5, 15.5) | 0.92 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (g) | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 0.79 |

| Protein (g) | 62.9 ± 17.7 | 63.7 (50.7, 74.8) | 62.5 ± 18.7 | 60.8 (50.0, 73.9) | 0.98 |

| Vegetable protein (g) | 24.5 ± 10.8 | 20.6 (17.2, 32.6) | 21.2 ± 7.5 | 20.2 (15.8, 25.0) | 0.03 |

| Animal protein (g) | 38.2 ± 19.3 | 36.8 (25.2, 53.3) | 41.1 ± 16.9 | 39.9 (30.0, 51.3) | 0.30 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 202.8 ± 58.3 | 210.0 (153.5, 235.2) | 201.8 ± 54.7 | 197.4 (165.3, 234.3) | 0.62 |

| Total fructose (g) | 34.5 ± 14.0 | 34.1 (22.7, 45.5) | 35.5 ± 15.2 | 33.9 (24.3, 45.3) | 0.99 |

| Added sugars (g) | 50.8 ± 24.5 | 49.0 (33.5, 73.1) | 58.4 ± 28.9 | 55.1 (37.5, 76.3) | 0.145 |

| Fiber (g) | 16.7 ± 8.0 | 13.4 (12.0, 20.6) | 13.2 ± 5.2 | 12.6 (9.3, 15.7) | 0.001 |

| Dairy (servings) | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.4 (0.7, 2.0) | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.4 (0.9, 2.0) | 0.65 |

| Low fat dairy | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.2 (0.0, 0.6) | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.2 (0.0, 0.5) | 0.71 |

| Reduced fat dairy | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.6) | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.3 (0.2, 0.3) | 0.21 |

| High fat dairy | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.6 (0.1, 1.1) | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.0) | 0.72 |

| Fruits and vegetables | 4.3 (1.9) | 3.8 (3.1, 5.6) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.4 (2.3, 4.6) | 0.18 |

| ≥5 servings (n [%]) | 26 (7.1) | 341 (92.9) | 0.05 | ||

| <5 servings (n [%]) | 15 (16.0) | 79 (84.0) | |||

| Micronutrients | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 7027 ± 6824 | 5102 (3746, 7752) | 5500 ± 4278 | 4101 (2588, 7138) | 0.13 |

| Beta carotene equivalents (mcg) | 3479 ± 4007 | 2379 (1444, 3913) | 2538 ± 2446 | 1708 (833, 3444) | 0.16 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | 0.05 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 83.7 ± 45.4 | 75.2 (51.6, 98.5) | 68.7 ± 41.4 | 59.7 (38.7, 91.2) | 0.30 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 7.2 ± 4.2 | 5.7 (4.5, 7.9) | 6.1 ± 3.6 | 5.2 (4.0, 7.0) | 0.16 |

| Lycopene (mcg) | 5704 ± 5292 | 4234 (2491, 7493) | 4360 ± 4329 | 3399 (1683, 6014) | 0.80 |

| Selenium (mcg) | 81.8 ± 22.9 | 83.2 (67.7, 91.5) | 89.3 ± 27.4 | 84.9 (69.0, 107.0) | 0.05 |

| Lutein and zeaxanthin (mcg) | 2375 ± 3234 | 1647 (670, 2551) | 1706 ± 1701 | 1132 (704, 2067) | 0.63 |

| Iron (mg) | 13.6 ± 5.0 | 13.2 (10.1, 15.0) | 12.3 ± 5.1 | 11.1 (9.0, 14.5) | 0.07 |

| Isoflavones (mg) | 7.3 ± 13.1 | 1.1 (0.5, 7.3) | 2.6 ± 6.7 | 0.5 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.05 |

| Caffeine (g) | 86.0 ± 87.7 | 57.7 (6.9, 145.2) | 95.6 ± 100.4 | 61.0 (15.2, 152.9) | 0.34 |

| Alcohol (g) | 2.2 ± 4.3 | 0.1 (0.0, 2.7) | 2.8 ± 6.2 | 0.1 (0.0, 3.2) | 0.98 |

Generalized linear models (taking into account multiple cycles from the same woman) were used to assess association between each variable and LPD while adjusting for age at screening interview, percentage body fat and total energy intake. Dietary characteristics were calculated from 24-h dietary recall corresponding to menses, mid-follicular, expected ovulation and mid-luteal phase visits and then averaged over the cycle. All P-values are differences in mean values. Dietary factors that were not normally distributed were log transformed prior to statistical analysis for differences.

Figure 1.

Relationship between MDS, fiber and isoflavone quartiles and LPD. P values for trend were calculated by taking the median value of the quartiles and analyzing as a continuous variable via generalized linear models adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake. The analyses revealed an apparent positive linear relationship for MDS (β = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.17, 0.75; P = 0.002), fiber (β = 0.09; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.18; P = 0.03) and isoflavone (β = 0.13; 95% CI: −0.01, 0.28; P = 0.06) quartiles and LPD defined as luteal phase duration <10 versus ≥10 days.

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratio for selenium intake and LPD using restricted cubic spline analysis. P-value for nonlinear relationship = 0.42. Reference is median selenium intake, 84.4 mcg. The curve is adjusted for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake. The spline has four knot points located at 52.4, 76.0. 94.0 and 138.6 mcg.

In the diet quality, macronutrient, and micronutrient multivariate models (including dietary factors marginally significant [P < 0.15]), for every unit increase in MDS dietary score there was a 1.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.17–2.48) increased odds of LPD after adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake (Table III). In the macronutrient model that included age, percentage body fat, total energy intake, vegetable protein, added sugars, fiber (all continuous) and fruit and vegetable intake (five or more daily compared with less than five), fiber (per g) had a marginally significant association with LPD (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.10, 95% CI: 0.99–1.23). In the micronutrient model, selenium (per 10 mcg) retained a significant inverse association with LPD (aOR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.65–0.97), while increased isoflavone intake (per mg) was modestly associated with LPD (aOR: 1.38; 95% CI: 0.99–1.92). Similar associations were observed for cycles with luteal duration <10 days and peak luteal progesterone ≤10 ng/ml (n = 38/463 [8.2%] cycles; aOR for MDS: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.13–2.44; aOR for fiber (per g), 1.10; 95% CI: 0.99–1.23; aOR for selenium (per mcg), 0.79; 95% CI: 0.64–0.97) (Table IV).

Table III.

Relationship between selected dietary factors and LPD, defined as luteal phase duration <10 versus ≥ 10 days.1

| Diet quality |

Macronutrients |

Micronutrients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 0.03 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.99) | 0.03 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 0.11 |

| Body fat (%) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.03) | 0.30 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 0.31 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | 0.11 |

| Total energy (per 100 kcal) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) | 0.32 | 0.92 (0.79, 1.06) | 0.23 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16) | 0.79 |

| Mediterranean Diet Score | 1.70 (1.17, 2.48) | 0.006 | — | — | ||

| Vegetable protein (g) | — | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 0.94 | — | ||

| Added sugars (g) | — | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.29 | — | ||

| Fiber (g) | — | 1.10 (0.99, 1.23) | 0.07 | — | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake (≥5 servings versus <5) | — | 1.58 (0.60, 4.20) | 0.36 | — | ||

| Vitamin A (per 100 IU) | — | — | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.14 | ||

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | — | — | 1.22 (0.49, 3.05) | 0.68 | ||

| Selenium (per 10 mcg) | — | — | 0.80 (0.65, 0.97) | 0.03 | ||

| Iron (per 10 mg) | — | — | 1.33 (0.49, 3.66) | 0.56 | ||

| Isoflavones (per 10 mg) | — | — | 1.38 (0.99, 1.92) | 0.06 | ||

Variables were included in the generalized linear multivariable model if prior research demonstrated an association with luteal phase duration <10 days (e.g. age and body fat) or the bivariate association in this study was marginally significant (P<0.15). OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Table IV.

Relationship between selected dietary factors and LPD, defined as luteal phase duration <10 versus ≥ 10 days and luteal progesterone ≤10 ng/ml.1

| Diet quality |

Macronutrients |

Micronutrients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | 0.02 | 0.91 (0.84, 0.98) | 0.02 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.01) | 0.07 |

| Body fat (%) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 0.44 | 0.97 (0.90, 1.05) | 0.50 | 0.95 (0.87, 1.03) | 0.19 |

| Total energy (per 100 kcal) | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) | 0.57 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.06) | 0.23 | 1.05 (0.91, 1.20) | 0.52 |

| Mediterranean Diet Score | 1.66 (1.13, 2.44) | 0.01 | — | — | ||

| Vegetable protein (g) | — | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 0.78 | — | ||

| Added sugars (g) | — | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.50 | — | ||

| Fiber (g) | — | 1.10 (0.99, 1.23) | 0.08 | — | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake (≥5 servings versus <5) | — | 1.63 (0.61, 4.36) | 0.33 | — | ||

| Vitamin A (per 100 IU) | — | — | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.11 | ||

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | — | — | 1.16 (0.46, 2.95) | 0.75 | ||

| Selenium (per 10 mcg) | — | — | 0.79 (0.64, 0.97) | 0.02 | ||

| Iron (per 10 mg) | — | — | 1.38 (0.50, 3.82) | 0.53 | ||

| Isoflavones (per 10 mg) | — | — | 1.40 (1.00, 1.96) | 0.05 | ||

Variables were included in the generalized linear multivariable model if prior research demonstrated an association with luteal phase duration <10 days (e.g. age and body fat) or the bivariate association in this study was marginally significant (P<0.15).

Discussion

In this prospective study of healthy women with no reported menstrual problems, we found that dietary characteristics were associated with LPD, with the Mediterranean diet, vegetable protein, fiber and isoflavone intake associated with increased LPD and selenium associated with decreased LPD after adjusting for age, percentage body fat and total energy intake. The effects of MDS, isoflavones and selenium persisted after adjusting for other dietary factors in the multivariable models, while fiber retained a modest association. Since LPD may contribute to infertility and early pregnancy loss (Li et al., 2000; Potdar and Konje, 2005), these associations warrant further study to better define the relationship between dietary factors and LPD and to determine if altering dietary habits can decrease the occurrence of LPD and improve fertility and pregnancy outcomes.

Global measures of diet quality, such as the MDS, are associated with decreased risk of important health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease (Knoops et al., 2004; Rees et al., 2013); however, the influence of such dietary patterns on the menstrual cycle and reproductive physiology is not clear. Studies have found that Mediterranean dietary patterns improve libido in women with the metabolic syndrome, possibly due to changes in endothelial function and decreased inflammation (Esposito et al., 2007). Our study found an association between higher MDS and higher odds of luteal phase dysfunction after adjusting for age, body fat and total energy intake. This contrasts with the previously described protective effects on cardiovascular and libido (Esposito et al., 2007; Rees et al., 2013).

While it is difficult to determine which component of the MDS (alone or in combination) drives the association with LPD, this effect may be related to the high levels of dietary fiber inherent in the Mediterranean diet, which relies on high intake of vegetable protein and whole grains. We have previously demonstrated an association between higher dietary fiber intake, lower reproductive hormone concentrations and increased risk of sporadic anovulation in the BioCycle Study (Gaskins et al., 2009). These findings reflect the complex relationship between diet, gut micro-organisms and enterohepatic circulation of reproductive hormones. Dietary fiber has many effects on enteral micro-organisms including altering the carbohydrate substrates available to bacteria, thereby altering species composition and population size, and altering the pH of the colonic environment by favoring fermentation (Flint, 2012). Prior research has demonstrated decreased levels of β-glucuronidase activity in vegetarians with high fiber intake (Goldin et al., 1982), which may decrease the deconjugation and reabsorption of reproductive hormones in the colon (Flores et al., 2012) and thereby decrease serum levels of progesterone and increase the risk of LPD. These findings are consistent with an important relationship between fiber, gut micro-organisms and reproductive physiology.

Although other global measurements of diet composition such as the ‘fertility diet’ (high in monounsaturated fats, vegetable protein, iron, high-fat dairy and multivitamins while low in trans fats, animal protein and low-fat dairy) have been associated with decreased risk of ovulatory infertility (Chavarro et al., 2007), we did not find significant associations with LPD and total or type of dairy or total or type of fat. We did find trends towards associations between increased iron and vegetable protein consumption and LPD after adjusting for age, body fat and total energy intake. This may indicate that ovulatory infertility and LPD have different underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms or that the effect of the combination of these dietary components is different than the effect of each component individually.

The finding that dietary selenium was significantly associated with lower odds of LPD is intriguing. In the clinical LPD micronutrient model, a 10 μg increase in average daily selenium consumption decreased the odds of LPD by 20% (aOR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.65–0.97), with a consumption of twice the daily recommended amount (110 mcg) resulting in a 77% reduction (aOR: 0.23; 95% CI: 0.08, 0.66). Prior research has shown associations between selenium deficiency and male-factor infertility (Hawkes and Turek, 2001; Safarinejad and Safarinejad, 2009), pre-eclampsia (Rayman et al., 2003; Ghaemi et al., 2013) and preterm labor (Rayman et al., 2011). Two small studies have investigated the association between serum selenium and luteal progesterone concentrations, one among 44 adolescents (mean age, 14.5 ± 0.5 years) (Zagrodzki et al., 2007) and the other among 36 young women (mean age, 23.5 ± 0.6) (Zagrodzki and Ratajczak, 2008), with only the adolescent study revealing a significant positive correlation. Our study represents the first report of an association between selenium with progesterone levels and menstrual cycle dysfunction in a relatively large population of healthy young women. This highlights the importance of oxidative stress on female reproductive physiology and may inform future clinical trials examining whether increased dietary selenium can improve menstrual cycle function, fertility and reproductive outcomes (Agarwal et al., 2012; Showell et al., 2013).

The apparently protective effect of increasing age in the multivariable models (Table III) should be interpreted with caution given the young population in our study. As menstrual cycle disturbances occur with increased frequency at the extremes of reproductive life, the exclusion of perimenopausal women may belie the increased frequency of LPD that would be expected in this age group (World Health Organization Task Force on Adolescent Reproductive Health, 1986; MacNaughton et al., 1992). Given previous research demonstrating a relationship between age and menstrual cycle disturbances (MacNaughton et al., 1992), we adjusted our findings with respect to dietary factors and LPD to account for age.

Our study's strengths include its prospective nature and the assessment of many different dietary and lifestyle variables as well as hormonal parameters via repeated measures timed to specific phases of the menstrual cycle. Study limitations include a relatively small number of outcomes compared with the number of parameters in the final multivariable model, which may result in overfitting, and multiple comparisons, which may increase the probability of a type I error beyond 0.05. We relied on participant self-report of their medical history to apply exclusion criteria; it is possible that we admitted to the study women with a gynecologic or medical disease who were unaware of their diagnosis. The number of LPD cycles also limited the number of factors for which we could adjust, which may lead to residual confounding. Although studies have shown that a fertility monitor is reasonably accurate at identifying the ovulation date (Behre et al., 2000), the calculation of luteal phase length based on an ovulation date established by a fertility monitor and/or serum LH surge may result in misclassification. In regards to exposure assessment, we were limited in our assessment of the effects of micronutrients, particularly at potentially toxic levels, on LPD, since women participating in the BioCycle Study had to be willing to stop regular intake of vitamin and/or mineral supplements and were excluded if they reported a high soy-based diet. Additionally, our dietary assessment relied on 24 h dietary recalls at four points during each cycle; if these recalls did not reflect dietary patterns on other days during the cycle, this could distort our results. However, multiple recalls are the gold standard for assessing dietary patterns and we found that within-woman variation of reported dietary patterns was minimal across cycles. Lastly, our study focused on the near-term effects of dietary patterns on the concurrent menstrual cycle; further longitudinal research, using gold-standard measures of assessment, is needed to examine whether habitual intake of certain foods, macronutrients and/ or micronutrients may influence menstrual cycle function.

In conclusion, in this sample of healthy women of reproductive age, Mediterranean-style diets including high amounts of fruits and vegetables, isoflavones and vegetable protein were positively associated with LPD while selenium was negatively associated with LPD after adjusting for age, body fat and total energy intake. These relationships warrant further study, particularly to determine if alterations in diet (for example, consuming less of a Mediterranean-style diet) may influence menstrual cycle function, fertility and pregnancy outcomes. Our results emphasize the complex and multifaceted effects of diet and lifestyle on female endocrinology and menstrual cycle function and highlight the need for further research into the pathophysiologic mechanism, clinical implications and treatment options for LPD.

Authors' roles

M.A.A. and K.C.S. had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. J.W.-W. was involved in the study concept and design, acquisition of data and study supervision. M.A.A., K.C.S., J.W.-W., J.B.S., S.M.Z., R.G.R., L.A.S., N.J.P., R.K., A.O.H. and S.L.M. were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. M.A.A., K.C.S. and S.L.M. were involved in the drafting of the manuscript. M.A.A., K.C.S., J.W.-W., J.B.S., S.M.Z., R.G.R., L.A.S., N.J.P., R.K., A.O.H. and S.L.M. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

None declared. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the Department of Defense or the US Government.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff at the Epidemiology Branch, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the University of Buffalo for their assistance and the BioCycle study participants for their involvement.

References

- Agarwal A, Aponte-Mellado A, Premkumar BJ, Shaman A, Gupta S. The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012;10:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo F, Noble LS. Endocrinology of recurrent pregnancy loss. Semin Reprod Med 2006;24:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr SI. Vegetarianism and menstrual cycle disturbances: is there an association? Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70:549s–554s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behre HM, Kuhlage J, Gassner C, Sonntag B, Schem C, Schneider HP, Nieschlag E. Prediction of ovulation by urinary hormone measurements with the home use ClearPlan Fertility Monitor: comparison with transvaginal ultrasound scans and serum hormone measurements. Hum Reprod 2000;15:2478–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd NF, Lockwood GA, Greenberg CV, Martin LJ, Tritchler DL. Effects of a low-fat high-carbohydrate diet on plasma sex hormones in premenopausal women: results from a randomized controlled trial. Canadian Diet and Breast Cancer Prevention Study Group. Br J Cancer 1997;76:127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Rosner BA, Willett WC. Diet and lifestyle in the prevention of ovulatory disorder infertility. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1050–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza MJ, Lee DK, VanHeest JL, Scheid JL, West SL, Williams NI. Severity of energy-related menstrual disturbances increases in proportion to indices of energy conservation in exercising women. Fertil Steril 2007;88:971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorgan JF, Hunsberger SA, McMahon RP, Kwiterovich PO Jr, Lauer RM, Van Horn L, Lasser NL, Stevens VJ, Friedman LA, Yanovski JA et al. Diet and sex hormones in girls: findings from a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med 1989;8:551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito K, Ciotola M, Giugliano F, Schisano B, Autorino R, Iuliano S, Vietri MT, Cioffi M, De Sio M, Giugliano D. Mediterranean diet improves sexual function in women with the metabolic syndrome. Int J Impot Res 2007;19:486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint HJ. The impact of nutrition on the human microbiome. Nutr Rev 2012;70(Suppl 1):S10–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores R, Shi J, Fuhrman B, Xu X, Veenstra TD, Gail MH, Gajer P, Ravel J, Goedert JJ. Fecal microbial determinants of fecal and systemic estrogens and estrogen metabolites: a cross-sectional study. J Transl Med 2012;10:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz M, Speroff L. Female infertility. In Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, 8th edn Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, 1162–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, Zhang C, Wactawski-Wende J, Hovey KM, Whitcomb BW, Howards PP, Perkins NJ, Yeung E, Schisterman EF. Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function: the BioCycle Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins AJ, Rovner AJ, Mumford SL, Yeung E, Browne RW, Trevisan M, Perkins NJ, Wactawski-Wende J, Schisterman EF. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and plasma concentrations of lipid peroxidation in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1461–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SZ, Forouhari S, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Sayadi M, Bakhshayeshkaram M, Vaziri F, Tavana Z. A prospective study of selenium concentration and risk of preeclampsia in pregnant Iranian women: a nested case-control study. Biol Trace Elem Res 2013;152:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin BR, Adlercreutz H, Gorbach SL, Warram JH, Dwyer JT, Swenson L, Woods MN. Estrogen excretion patterns and plasma levels in vegetarian and omnivorous women. N Engl J Med 1982;307:1542–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes WC, Turek PJ. Effects of dietary selenium on sperm motility in healthy men. J Androl 2001;22:764–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henmi H, Endo T, Kitajima Y, Manase K, Hata H, Kudo R. Effects of ascorbic acid supplementation on serum progesterone levels in patients with a luteal phase defect. Fertil Steril 2003;80:459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howards PP, Schisterman EF, Wactawski-Wende J, Reschke JE, Frazer AA, Hovey KM. Timing clinic visits to phases of the menstrual cycle by using a fertility monitor: the BioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HW., Jr Luteal-phase defect: the role of Georgeanna Seegar Jones. Fertil Steril 2008;90:e5–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan J, Craig K, Clifton DK, Soules MR. Luteal phase defect: the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods in common clinical use. Fertil Steril 1994;62:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoops KT, de Groot LC, Kromhout D, Perrin AE, Moreiras-Varela O, Menotti A, van Staveren WA. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. JAMA 2004;292:1433–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koloverou E, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Panagiotakos D. The effect of Mediterranean diet on the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies and 136,846 participants. Metabolism 2014;63:903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenton EA, Landgren BM, Sexton L. Normal variation in the length of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle: identification of the short luteal phase. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1984;91:685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TC, Spuijbroek MD, Tuckerman E, Anstie B, Loxley M, Laird S. Endocrinological and endometrial factors in recurrent miscarriage. BJOG 2000;107:1471–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNaughton J, Banah M, McCloud P, Hee J, Burger H. Age related changes in follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, oestradiol and immunoreactive inhibin in women of reproductive age. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1992;36:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm CE, Cumming DC. Does anovulation exist in eumenorrheic women? Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:317–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T. Measurement characteristics of the Women's Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol 1999;9:178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potdar N, Konje JC. The endocrinological basis of recurrent miscarriages. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2005;17:424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current clinical irrelevance of luteal phase deficiency: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2015;103:e27–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayman MP, Bode P, Redman CW. Low selenium status is associated with the occurrence of the pregnancy disease preeclampsia in women from the United Kingdom. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayman MP, Wijnen H, Vader H, Kooistra L, Pop V. Maternal selenium status during early gestation and risk for preterm birth. CMAJ 2011;183:549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees K, Hartley L, Flowers N, Clarke A, Hooper L, Thorogood M, Stranges S. ‘Mediterranean’ dietary pattern for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;8:CD009825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad MR, Safarinejad S. Efficacy of selenium and/or N-acetyl-cysteine for improving semen parameters in infertile men: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized study. J Urol 2009;181:741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schakel SF, Sievert YA, Buzzard IM. Sources of data for developing and maintaining a nutrient database. J Am Diet Assoc 1988;88:1268–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzkin A, Kipnis V, Carroll RJ, Midthune D, Subar AF, Bingham S, Schoeller DA, Troiano RP, Freedman LS. A comparison of a food frequency questionnaire with a 24-hour recall for use in an epidemiological cohort study: results from the biomarker-based Observing Protein and Energy Nutrition (OPEN) study. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:1054–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliep KC, Mumford SL, Hammoud AO, Stanford JB, Kissell KA, Sjaarda LA, Perkins NJ, Ahrens KA, Wactawski-Wende J, Mendola P et al. Luteal phase deficiency in regularly menstruating women: prevalence and overlap in identification based on clinical and biochemical diagnostic criteria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:E1007–E1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger U, Laessle R, Pfister H, Hoehl C, Schwingenschloegel M, Schweiger M, Pirke KM. Diet-induced menstrual irregularities: effects of age and weight loss. Fertil Steril 1987;48:746–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger U, Tuschl RJ, Platte P, Broocks A, Laessle RG, Pirke KM. Everyday eating behavior and menstrual function in young women. Fertil Steril 1992;57:771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showell MG, Brown J, Clarke J, Hart RJ. Antioxidants for female subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;8:CD007807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SK, Lenton EA, Landgren BM, Cooke ID. Is the short luteal phase a defective luteal phase? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1985;442:387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag B, Ludwig M. An integrated view on the luteal phase: diagnosis and treatment in subfertility. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;77:500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subar AF, Kipnis V, Troiano RP, Midthune D, Schoeller DA, Bingham S, Sharbaugh CO, Trabulsi J, Runswick S, Ballard-Barbash R et al. Using intake biomarkers to evaluate the extent of dietary misreporting in a large sample of adults: the OPEN study. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usadi RS, Groll JM, Lessey BA, Lininger RA, Zaino RJ, Fritz MA, Young SL. Endometrial development and function in experimentally induced luteal phase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4058–4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wactawski-Wende J, Schisterman EF, Hovey KM, Howards PP, Browne RW, Hediger M, Liu A, Trevisan M. BioCycle study: design of the longitudinal study of the oxidative stress and hormone variation during the menstrual cycle. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:171–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NI, Helmreich DL, Parfitt DB, Caston-Balderrama A, Cameron JL. Evidence for a causal role of low energy availability in the induction of menstrual cycle disturbances during strenuous exercise training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:5184–5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NI, Leidy HJ, Hill BR, Lieberman JL, Legro RS, De Souza MJ. Magnitude of daily energy deficit predicts frequency but not severity of menstrual disturbances associated with exercise and caloric restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015;308:E29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Task Force on Adolescent Reproductive Health. WHO multicenter study on menstrual and ovulatory patterns in adolescent girls. II. Longitudinal study of menstrual patterns in the early postmenarcheal period, duration of bleeding episodes and menstrual cycles. J Adolesc Health Care 1986;7:236–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagrodzki P, Ratajczak R. Selenium status, sex hormones, and thyroid function in young women. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2008;22:296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagrodzki P, Ratajczak R, Wietecha-Posluszny R. The interaction between selenium status, sex hormones, and thyroid metabolism in adolescent girls in the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle. Biol Trace Elem Res 2007;120:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]