Abstract

Background

Little is known about the barriers faced by families of children with birth defects in obtaining healthcare. We examined reported perceived barriers to care and satisfaction with care among mothers of children with orofacial clefts.

Methods

In 2006, a validated barriers to care mail/phone survey was administered in North Carolina to all resident mothers of children with orofacial clefts born between 2001 and 2004. Potential participants were identified using the North Carolina Birth Defects Monitoring Program, an active, state-wide, population-based birth defects registry. Five barriers to care subscales were examined: pragmatics, skills, marginalization, expectations, and knowledge/beliefs. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted using chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. Results were stratified by cleft type and presence of other birth defects.

Results

Of 475 eligible participants, 51.6% (n = 245) responded. The six most commonly reported perceived barriers to care were all part of the pragmatics subscale: having to take time off work (45.3%); long waits in the waiting rooms (37.6%); taking care of household responsibilities (29.7%); meeting other family members' needs (29.5%); waiting too many days for appointments (27.0%); and cost (25.0%). Most respondents (72.3%, 175/242) felt “very satisfied” with their child's cleft care.

Conclusion

Although most participants reported being satisfied with their child's care, many perceived barriers to care were identified. Due to the limited understanding and paucity of research on barriers to care for children with birth defects, including orofacial clefts, additional research on barriers to care and factors associated with them are needed.

Keywords: health services accessibility, access to health care, orofacial clefts, cleft lip, cleft palate, birth defects

Introduction

Orofacial clefts (OFCs) are one of the most prevalent birth defects in the United States, occurring in approximately one of every 960 live births (Parker et al., 2010). Orofacial clefts include cleft lip, cleft palate, and cleft lip with cleft palate. Children with OFCs often require multiple surgeries, procedures, and follow-up care after their initial surgical repair due to potential feeding problems, speech and language development, and may need additional dental and orthodontic care compared with children without OFCs (Nackashi et al., 2002; Riski, 2002; ACPA, 2009).

Previous research has shown that children with special health care needs (CSHCN) tend to face more barriers to healthcare than children without special health care needs (Newacheck et al., 2000, 2002; McPherson et al., 2004; Strickland et al., 2004, 2009; van Dyck et al., 2004; Newacheck and Kim, 2005; Skinner and Slifkin, 2007; Chiri and Warfield, 2012; Romaire et al., 2012). Furthermore, access to care is critically important for these children's quality of life, outcomes, and well-being (Seid et al., 2004; Ngui and Flores, 2006; Skinner and Slifkin, 2007; Yu and Sing, 2009; Kerfeld et al., 2011). In a recent review of CSHCN and barriers to care literature, Nelson et al. (2012) found a lack of research on the experiences of care delivery, organization, and outcomes. In addition, children with a primary diagnosis of a craniofacial birth defect were most impacted by cost and accessibility of care and competing demands compared with children with a different primary diagnosis, with the exception of cerebral palsy (Nelson et al., 2012). While high parental satisfaction was previously reported, how satisfaction was defined and conceptualized may be problematic in these previous studies (Nelson et al., 2012). Moreover, most previous studies only sampled one hospital or center and did not collect data using validated instruments (Nelson et al., 2012).

In an expert meeting sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, experts determined that access to care for children with OFCs was a public health research priority (Yazdy et al., 2007). Research into barriers to care among specific populations, like families of children with birth defects, is needed to better understand disparities in access to care (Yazdy et al., 2007; Strauss and Cassell, 2009; Wehby and Cassell, 2010; Nelson et al., 2011). Currently, little research exists on barriers to and disparities in access to care for children with OFCs.

In 2006, a qualitative assessment of maternal perceptions on barriers to care was conducted using a statewide, population-based birth defects registry and a validated barriers to care survey. The study was conducted to assess maternal perspectives on perceived barriers to care for children with OFCs and identify potential problems accessing cleft care, using open-ended and close-ended responses. Results on the open-ended response and travel time and distance were previously published (Cassell et al., 2012, 2013).

The purpose of this study was to examine commonly reported perceived barriers to care for children with OFCs and determine any maternal, child, and system characteristics associated with potential barriers. To our knowledge, no study has examined barriers to care specifically for children with OFCs, using a validated and reliable barriers to care questionnaire with a sample drawn from a statewide, population-based birth defects registry.

Materials and Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND SAMPLE

Children who were born in North Carolina between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2004, and diagnosed with an OFC during their first year of life and captured by the North Carolina Birth Defects Monitoring Program (NCBDMP), were eligible for this study. The NCBDMP, an active, state-wide, population-based birth defects registry, captures births from all nonmilitary North Carolina hospitals and links vital statistics, hospital discharge, and health service use data to each infant with a birth defect (NBDPN, 2011). Children with OFCs were identified from the NCBDMP using diagnostic codes from the British Pediatric Association (749.000–749.290). Potential participants were excluded if the mothers lived outside of North Carolina, had a child with an OFC that died at any point, or if the child with OFC was adopted.

SURVEY INSTRUMENT

The questionnaire was developed, pilot tested, and distributed in both English and Spanish. Questionnaires were mailed between May and October 2006. Initially, the maternal residential address on the birth certificate was used to mail the surveys for all mothers of identified children with OFCs. Respondents received the survey, a recruitment letter, and a fact sheet about the study. If no response was received after 1 month, subjects were traced using publicly accessible national search databases and North Carolina health services databases. After 2 to 3 months of no response, respondents were contacted by means of telephone by trained phone interviewers. Participants who completed the survey were given a $10 gift card to a major retail store.

The survey instrument was adapted from a previous questionnaire that was designed to measure parental experiences that may impact access to care, ability to follow medical instructions, and the clinical encounter (Seid et al., 2004, 2009). The questionnaire was developed from a literature review, focus groups, and cognitive interviews with both English and Spanish speaking parents of children with chronic health conditions. The feasibility, internal consistency, and construct validity of the questionnaire were confirmed through pilot testing (Seid et al., 2004). This survey measures perceived barriers to care as multidimensional constructs on five subscales: (1) pragmatics, which included the logistical or cost related problems (9 constructs); (2) skills, which included learned strategies used to interact with the healthcare system (7 constructs); (3) marginalization, which was negative experiences within the healthcare system that parents internalize (10 constructs); (4) expectations of receiving poor quality care (6 constructs); and (5) knowledge/beliefs about popular ideas about treatment or the nature of illness that differs from mainstream medicine (four constructs) (Seid et al., 2004). We used these same five subscales in our analyses.

Thirty-nine of the total 76 open- and closed-ended survey items were specific barriers taken almost directly from the Seid et al. (2004) validated questionnaire. Thirty-five of these questions were analyzed on the five barriers to care subscales. Additional questions focused on demographic characteristics, health services use, and satisfaction of the care received. For potential perceived barriers within the five subscales, survey respondents were asked “How often were each of the following barriers a problem in the past 12 months when trying to get primary cleft or craniofacial care for your child with facial differences?” (Primary cleft or craniofacial care is the first location where receive services or the location where receive most services.) Answers were scored on a five-point Likert scale: never, almost never, sometimes, often, and almost always. Respondents could also answer not applicable. If respondents left an answer blank or marked not applicable, they were omitted from the denominator for that question only.

We also examined satisfaction with care and whether or not primary cleft and craniofacial care worked well for the child in the last 12 months in comparison with the barriers to care subscales. Due to small numbers for the question on satisfaction, we collapsed the five Likert-scale into two categories: (1) “very satisfied” and “satisfied”; and (2) “neither satisfied or dissatisfied,” “dissatisfied,” and “very dissatisfied” (Seid et al., 2004; Cassell et al., 2013).

Race and ethnicity questions were asked separately in the survey. Racial/ethnic categories included on the survey were: White, Hispanic, Black/African-American, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian. We also included an open-ended “Other” category where respondents could enter their race/ethnicity, and respondents could select all that applied. Due to small numbers, we created a mutually exclusive race/ethnicity variable with categories of “non-Hispanic White” and “Other.” Thirteen respondents selected more than one race category, all 13 selected White as one of those categories and did not check Hispanic. We recoded these 13 respondents into the non-Hispanic White category (Cassell et al., 2013).

Information on health insurance coverage for both the mother and child was collected as a binary variable (yes/no). If yes, the respondents were asked to report the primary health insurance type for both the mother and child. (Primary was defined as the plan that pays the medical bills first or pays most of the medical bills.) Private insurance included enrollment in the State Employee Health Plan or any private health insurance plan purchased through an employer or directly from an insurance company. Public health insurance included the following programs: North Carolina Health Choice (state Children's Health Insurance Program), Medicaid, Carolina ACCESS, or Health Check. Military insurance included Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services, TRICARE, or the Veteran's Administration.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics and demographic information were categorized as maternal, child, or system characteristics. Maternal characteristics included age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, marital status, number of children in the household, and number of CSHCN in the household. Child characteristics included sex, age, race/ethnicity, cleft type and the presence of other birth defects, low birth weight (<2500 grams), and preterm birth (<37 weeks). Nonisolated OFCs were categorized as an OFC diagnosis with the presence of any additional, major or minor, birth defect. If no other birth defect was present except the OFC, the OFC was categorized as isolated. System characteristics consisted of maternal and child health coverage status (yes/no) and primary insurance provider, travel time and distance to primary cleft or craniofacial center, and primary (main) language spoken in the household. One-way travel time and distance were dichotomized (≤ 60 min or >60 min and ≤60 miles or >60 miles, respectively). All data were from the survey except the child's sex, child's OFC diagnosis (cleft type and presence of other birth defects), birth weight, and gestational age, which were obtained from the birth certificate and/or the medical record. Because 24 respondents (9.8%) had missing maternal age or had illogical responses, we imputed mother's date of birth from the North Carolina vital records and calculated maternal age.

For the perceived barriers to care questions, the five-point Likert scale was collapsed and dichotomized into never/almost never (reference category) and sometimes/often/almost always due to the frequency distributions. We reclassified the sometimes/often/almost always as “ever having a problem” accessing cleft care. We also analyzed the mother's and child's insurance status by race/ethnicity, cleft phenotype, and satisfaction with cleft care to determine if there were any differences.

Bivariate analyses were conducted using chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. No multivariable analyses were conducted due to insufficient sample sizes. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals were received from the North Carolina Division of Public Health IRB and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Public Health and Nursing IRB.

Results

Of the 475 eligible participants, 245 (51.6%) responded. Of the remaining 230 that did not participate, 205 (89.1%) were lost to follow-up due to unavailable or inaccurate phone and address information and 25 (10.9%) were contacted but refused to participate. It was possible that for the 205 eligible participants lost to follow-up, we had the correct phone and address information; however, they chose not to participate.

Respondents and nonrespondents only differed in regards to maternal race/ethnicity (p < 0.0001) and maternal education (p < 0.0001); respondents were more likely to be non-Hispanic White and have more than a high school education. No significant differences were observed in maternal age, child's age, child's sex, cleft type, presence of other birth defects, low birth weight or preterm birth (Cassell et al., 2013).

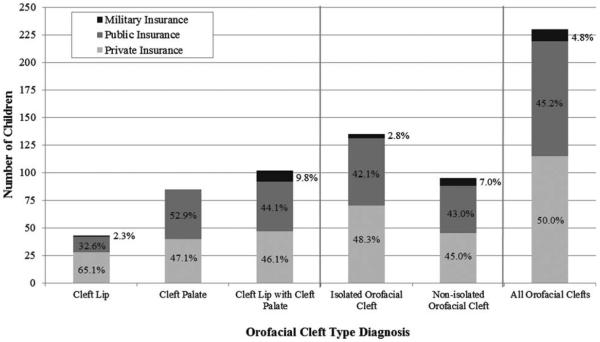

The majority of survey respondents were biological mothers (97.1%; n = 238), non-Hispanic White (83.3%; n = 204), ≤35 years old (72.2%; n = 177), married (69.4%; n = 170) and currently employed (57.6%; n = 141). Approximately 19% (n = 46) of infants were born preterm and 17.1% (n = 42) were born low birth weight. Approximately 80% of the children were between 2 and 4 years old at the time of the survey (n = 197) and 57.6% (n = 141) of them were male. Approximately 45% (n = 109) of children had cleft lip with cleft palate, and among all children with OFC, 59.2% (n = 145) had an isolated OFC. In most households, the child diagnosed with an OFC was the only child with special healthcare needs (69.8%; n = 171). Among all children with OFC that had health insurance, 46.9% (n = 115) had private insurance and 42.4% (n = 104) had public health insurance (Table 1). Among children with cleft lip only, 65.1% had private insurance; children with cleft lip with cleft palate and cleft palate only had smaller proportions of private health insurance coverage, 46.1% and 47.1%, respectively. Among those with isolated OFCs, approximately 48% of children had private health insurance. There were no statistically significant differences observed by cleft type and isolated versus nonisolated OFCs with the child's primary health insurance type (Fig. 1). However, there were statistical differences between the mother's and child's race and primary health insurance, p = 0.02 and p < 0.0001, respectively (results not shown).

TABLE 1.

Selected Maternal, Child, and System Characteristics of Survey Respondents and Their Children With Orofacial Clefts (OFC) in North Carolina, 2001–2004

| Characteristics (N=245) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | ||

| Agea | ||

| < 30 years old | 92 | 37.6 |

| 30–35 years old | 85 | 34.7 |

| > 36 years old | 68 | 27.8 |

| Education | ||

| Elementary and some high school | 28 | 11.4 |

| High school graduate | 57 | 23.3 |

| Some college | 77 | 31.4 |

| College graduate | 81 | 33.1 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.8 |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||

| White | 204 | 83.3 |

| Non-White/othera | 41 | 16.7 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 | 4.9 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 233 | 95.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 170 | 69.4 |

| Previously married | 39 | 15.9 |

| Never married | 34 | 13.9 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.8 |

| Annual household income (before taxes) | ||

| ≤ $19,999 | 70 | 28.6 |

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 72 | 29.4 |

| ≥ $50,000 | 92 | 37.6 |

| Missing | 11 | 4.5 |

| Number of CSNCN in householdd | ||

| None | 171 | 69.8 |

| ≥1 child | 70 | 28.6 |

| Missing | 4 | 1.6 |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 2 years old (13–24 months) | 60 | 24.5 |

| 3 years old (25–36 months) | 75 | 30.6 |

| 4 years old (37–48 months) | 62 | 25.3 |

| 5 years old (49–60 months) | 30 | 12.2 |

| 6 years old (61–72 months) | 18 | 7.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 199 | 81.2 |

| Non-White/Otherc | 46 | 18.8 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 | 5.7 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 231 | 94.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 141 | 57.6 |

| Female | 104 | 42.4 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | ||

| Yes | 46 | 18.8 |

| No | 199 | 81.2 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 grams) | ||

| Yes | 42 | 17.1 |

| No | 203 | 82.9 |

| Cleft type | ||

| Cleft lip only | 47 | 19.2 |

| Cleft palate only | 89 | 36.3 |

| Cleft lip with cleft palate | 109 | 44.5 |

| Presence of other birth defects | ||

| Yes (non-isolated orofacial cleft) | 100 | 40.8 |

| No (isolated orofacial cleft) | 145 | 59.2 |

| System characteristics | ||

| Child's primary health insurancee | ||

| Private health insurance | 115 | 46.9 |

| Public health insurance | 104 | 42.4 |

| Military | 11 | 4.5 |

| Uninsured | 14 | 5.7 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.4 |

| Mother's primary health insurancee | ||

| Private health insurance | 140 | 57.1 |

| Public health insurance | 40 | 16.3 |

| Military | 9 | 3.7 |

| Uninsured | 52 | 21.2 |

| Missing | 4 | 1.6 |

| Native/primary language spoken in household | ||

| English | 231 | 94.3 |

| Other | 11 | 4.5 |

| Missing | 3 | 1.2 |

| Average one-way travel timef (N= 242) | ||

| 0–60 min | 125 | 51.7 |

| ≥61 min | 117 | 48.3 |

| Average one-way travel distancef (N= 232) | ||

| 0–60 miles | 149 | 64.2 |

| ≥61 miles | 83 | 35.8 |

24 respondents had missing mother's age or had illogical response, so used North Carolina vital statistics data to impute maternal age.

13 respondents (5.3%) marked White plus one other race, but were categorized as White for analysis.

`Other' included Hispanic, Black/African American, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander or an open-ended `Other' option.

Other than the child with an orofacial cleft.

Private health insurance = enrollment in the State Employee Health Plan or a private health insurance plan purchased from an employer or directly from an insurance company; Public health insurance = enrollment in North Carolina Health Choice (State Children's Health Insurance Program), Medicaid, Carolina ACCESS or Health Check; Military insurance = enrollment in Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services, TRICARE (formerly Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services) or the Veteran's Administration.

Previously published results from Cassell et al., 2013.

CSHCN, children with special healthcare needs.

FIGURE 1.

Among children with health insurance, distribution of parent-reported health insurance types by orofacial cleft (OFC) diagnosis for children with OFCs in North Carolina, 2001–2004. Nonisolated OFCs were defined as an OFC diagnosis with the presence of any additional, major or minor, birth defect, and OFCs were considered isolated if no other birth defect was present.

Table 2 includes a complete ranking of the 35 potential perceived barriers to care with the corresponding subscales assessed in our questionnaire. The most commonly reported perceived barriers to care included: having to take time off work (45.3%); long waits in waiting rooms (37.6%); taking care of household responsibilities (29.7%); having to meet the needs of other family members (29.5%); waiting extended periods of time for appointments (27.0%); and cost (25.0%). The least common perceived barriers to care were: having doctors not fluent in the native language (3.1%), doctors providing instructions that seemed wrong (3.5%), doctors not believing in home or traditional remedies (3.5%), and perceived judgment based on appearance, ancestry, or accent (3.9%).

TABLE 2.

Rank-Ordered (Highest to Lowest) Perceived Barriers to Care Reported as “Almost Always/Often/Sometimes” a Problem Among Parents of Children With Orofacial Clefts in North Carolina, 2001–2004

| Ranking | Survey questions | N | Totala | Percentage | Subscale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Having to take time off work | 86 | 190 | 45.3 | Pragmatics |

| 2 | Having to wait too long in waiting room | 77 | 205 | 37.6 | Pragmatics |

| 3 | Having to take care of household responsibilities | 55 | 185 | 29.7 | Pragmatics |

| 4 | Meeting the needs of other family members | 56 | 190 | 29.5 | Pragmatics |

| 5 | Having to wait too many days for an appointment | 54 | 200 | 27.0 | Pragmatics |

| 6 | Cost of primary cleft or craniofacial careb | 49 | 196 | 25.0 | Pragmatics |

| 7 | Not knowing what to expect from one visit to the next | 42 | 208 | 20.2 | Marginalization |

| 8 | Having enough information about how care works | 42 | 209 | 20.1 | Skills |

| 9 | Getting hold of the doctor's office or clinic by phone | 40 | 208 | 19.2 | Pragmatics |

| 10 | Getting to the doctor's office | 39 | 205 | 19.0 | Pragmatics |

| 11 | Needing to be more `savvy' or knowledgeable about care | 37 | 207 | 17.9 | Skills |

| 12 | Lack of communication between doctors involved with care | 28 | 205 | 13.7 | Expectations |

| 13 | Being rushed through visits | 28 | 209 | 13.4 | Marginalization |

| 14 | Getting care after hours or on weekends | 18 | 139 | 13.0 | Pragmatics |

| 15 | Getting questions answered | 27 | 209 | 12.9 | Marginalization |

| 16 | Getting enough help with paperwork or forms | 26 | 202 | 12.9 | Skills |

| 17 | Worrying that care is not right for child | 26 | 206 | 12.6 | Expectations |

| 18 | Doctors/nurses speaking too technical or medical | 24 | 205 | 11.7 | Skills |

| 19 | Getting a thorough examination | 22 | 207 | 10.6 | Expectations |

| 20 | Getting doctor to listen | 20 | 208 | 9.6 | Marginalization |

| 21 | Rude office staff | 19 | 208 | 9.1 | Marginalization |

| 22 | Getting referrals to specialists | 17 | 200 | 8.5 | Skills |

| 23 | Mistakes made by doctors/nurses | 17 | 206 | 8.3 | Expectations |

| 24 | Understanding doctor's orders | 17 | 208 | 8.2 | Skills |

| 25 | Doctors/nurses have different ideas about health | 16 | 204 | 7.8 | Knowledge and Beliefs |

| 26 | Feeling like doctors are trying to give minimal service | 16 | 208 | 7.7 | Marginalization |

| 27 | Offices and staff not child-friendly | 14 | 208 | 6.7 | Expectations |

| 28 | Intimidating doctors | 13 | 208 | 6.3 | Marginalization |

| 29 | Impatient doctors | 12 | 207 | 5.8 | Marginalization |

| 30 | Disagreeing with doctor's orders | 12 | 207 | 5.8 | Knowledge and Beliefs |

| 31 | Uncaring office staff | 12 | 208 | 5.8 | Marginalization |

| 32 | Being judged on appearance, ancestry or accent | 8 | 207 | 3.9 | Marginalization |

| 33 | Doctors not believing in home/traditional remedies | 6 | 174 | 3.5 | Knowledge and Beliefs |

| 34 | Doctors giving instructions that seem wrong | 7 | 203 | 3.5 | Knowledge and Beliefs |

| 35 | Doctors not fluent in native language | 6 | 191 | 3.1 | Skills |

Total refers to the number of responses analyzed; missing and `not applicable' responses were omitted from the analysis.

Primary cleft or craniofacial care was the first location where received services or the location where received most services.

For satisfaction with cleft care, 97.5% (236/242) reported being “very satisfied” or “satisfied” and 2.5% (6/242) reported being “neither satisfied or dissatisfied,” “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with the overall primary cleft or craniofacial care their child received. Due to insufficient sample sizes with dissatisfaction with care, we were not able to stratify results by cleft phenotype (cleft lip with cleft palate, cleft palate only, cleft lip only, and isolated vs. nonisolated OFCs) or any other characteristics (results not shown).

Approximately 87% (161/186) of mothers reported that their child's care “often” or “almost always” worked well for them in the last 12 months. There were statistical differences between how often care worked well (never/almost never vs. sometimes/often/almost always) and maternal race (p = 0.0002), maternal ethnicity (p = 0.0019), child's race (p = 0.0006), presence of other birth defects (p = 0.0075), and primary language spoken in the household (p = 0.0227). No significant differences were observed when responses were stratified by cleft phenotype (results not shown).

Bivariate analyses were conducted on the six most commonly perceived barriers to care and maternal, child, and system characteristics (Table 3). Having to take time off of work was associated with the number of CSHCN in the home (p = 0.005), child's primary health insurance (p = 0.05) and travel time and distance (p = 0.005 and p = 0.02, respectively). Extended waiting in the waiting room was associated with maternal age (p = 0.05), maternal education level (p = 0.005), marital status (p=0.04), the number of CSHCN in the home (p = 0.03), child's sex (p = 0.002), and child's health insurance type (p = 0.007). Having to take care of household responsibilities was associated with the number of CSHCN (p = 0.005) and travel time (p = 0.01). Difficulty meeting the needs of other family members was associated with the number of CSHCN in the home (p = 0.001) and travel time to cleft and craniofacial care (p = 0.02). Cost of care was associated with household income (p = 0.002), marital status (p = 0.05), and mother's and child's primary health insurance type (p = 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Having to wait long periods of time for an appointment was not significantly associated with any characteristics (Table 3). Travel time was associated with 50% (3/6) of the most commonly reported barriers to care. No significant differences were observed when responses were stratified by cleft phenotype (results not shown).

TABLE 3.

Top Six Most Commonly Reported Perceived Barriers to Care: Frequencies of “Never” (Never/Almost Never) vs. “Ever” (Sometimes/Often/Almost Always) a Problem by Selected Maternal, Child, and System Characteristics

| Barrier to care | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Characteristics | Having to take time off work | Having to wait too long in waiting room | Having to take care of household responsibilities | Meeting the needs of other family members | Having to wait too many days for an appointment | Cost of primary cleft/craniofacial caree | ||||||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Agea | p-value: 0.40 | p-value: 0.05 | p-value: 0.47 | p-value: 0.30 | p-value: 0.19 | p-value: 0.21 | ||||||

| < 30 years old | 35 | 37 | 54 | 24 | 50 | 24 | 55 | 20 | 51 | 26 | 59 | 16 |

| 30–35 years old | 40 | 27 | 47 | 25 | 50 | 16 | 48 | 17 | 54 | 18 | 53 | 15 |

| > 36 years old | 29 | 22 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 15 | 31 | 19 | 41 | 10 | 35 | 18 |

| Education | p-value: 0.66 | p-value: 0.005 | p-value: 0.25 | p-value: 0.23 | p-value: 0.10 | p-value: 0.22 | ||||||

| Elementary and some high school | 11 | 11 | 14 | 9 | 17 | 6 | 13 | 8 | 17 | 6 | 19 | 4 |

| High school graduate | 27 | 18 | 33 | 17 | 35 | 10 | 37 | 8 | 35 | 14 | 40 | 7 |

| Some college | 29 | 29 | 49 | 14 | 42 | 15 | 42 | 19 | 44 | 16 | 42 | 17 |

| College graduate | 37 | 26 | 32 | 35 | 36 | 23 | 41 | 21 | 48 | 18 | 46 | 19 |

| Raceb | p-value: 0.84 | p-value: 0.58 | p-value: 0.44 | p-value: 0.76 | p-value: 0.94 | p-value: 0.07 | ||||||

| White | 87 | 71 | 106 | 66 | 110 | 44 | 110 | 47 | 121 | 45 | 119 | 45 |

| Non-White/Otherc | 17 | 15 | 22 | 11 | 20 | 11 | 24 | 9 | 25 | 9 | 28 | 4 |

| Ethnicity | p-value: 0.90 | p-value: 0.46 | p-value: 0.76 | p-value: 0.97 | p-value: 0.90 | p-value: 0.40 | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 2 | 2 | 7 3 | 3 | 6 2 | 2 | 7 1 | 1 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 100 | 83 | 124 | 73 | 124 | 53 | 127 | 53 | 140 | 52 | 140 | 48 |

| Marital status | p-value: 0.64 | p-value: 0.04 | p-value: 0.59 | p-value: 0.94 | p-value: 0.47 | p-value: 0.05 | ||||||

| Currently married | 69 | 61 | 83 | 61 | 87 | 39 | 91 | 38 | 101 | 37 | 98 | 40 |

| Previously married | 19 | 12 | 25 | 7 | 25 | 7 | 23 | 9 | 25 | 7 | 28 | 4 |

| Never married | 16 | 11 | 20 | 7 | 18 | 8 | 19 | 9 | 180 | 10 | 21 | 3 |

| Annual household income (before taxes) | p-value: 0.09 | p-value: 0.59 | p-value: 0.55 | p-value: 0.58 | p-value: 0.96 | p-value: 0.002 | ||||||

| < $19,999 | 31 | 20 | 37 | 17 | 40 | 13 | 36 | 18 | 41 | 14 | 49 | 4 |

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 24 | 33 | 40 | 24 | 39 | 20 | 39 | 19 | 46 | 17 | 43 | 16 |

| > $50,000 | 43 | 30 | 46 | 31 | 46 | 19 | 52 | 18 | 52 | 20 | 49 | 26 |

| Number of CSHCN in household | p-value: 0.005 | p-value: 0.03 | p-value: 0.005 | p-value: 0.001 | p-value: 0.08 | p-value: 0.78 | ||||||

| None | 81 | 51 | 95 | 47 | 99 | 31 | 100 | 29 | 107 | 33 | 105 | 34 |

| >1 child | 21 | 33 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 23 | 31 | 26 | 36 | 20 | 39 | 10 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age | p-value: 0.13 | p-value: 0.09 | p-value: 0.84 | p-value: 0.89 | p-value: 0.34 | p-value: 0.13 | ||||||

| 2 years old (13–24 months) | 33 | 19 | 42 | 14 | 38 | 15 | 40 | 13 | 41 | 15 | 43 | 11 |

| 3 years old (25–36 months) | 23 | 34 | 39 | 22 | 38 | 16 | 37 | 18 | 37 | 21 | 38 | 19 |

| 4 years old (37–48 months) | 25 | 18 | 24 | 25 | 30 | 15 | 29 | 14 | 38 | 11 | 33 | 14 |

| 5 years old (49–60 months) | 15 | 9 | 14 | 11 | 14 | 7 | 18 | 7 | 18 | 5 | 23 | 2 |

| 6 years old (61–72 months) | 8 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 3 |

| Raceb | p-value: 0.78 | p-value: 0.64 | p-value: 0.60 | p-value: 0.94 | p-value: 0.83 | p-value: 0.07 | ||||||

| White | 83 | 70 | 103 | 64 | 106 | 43 | 107 | 45 | 117 | 44 | 115 | 44 |

| Non-White/Otherc | 21 | 16 | 25 | 13 | 24 | 12 | 27 | 11 | 29 | 10 | 32 | 5 |

| Ethnicity | p-value: 0.76 | p-value: 0.93 | p-value: 0.49 | p-value: 0.73 | p-value: 0.50 | p-value: 0.21 | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 1 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 99 | 81 | 121 | 73 | 122 | 53 | 125 | 53 | 137 | 52 | 137 | 48 |

| Sex | p-value: 0.56 | p-value: 0.002 | p-value: 0.62 | p-value: 0.12 | p-value: 0.34 | p-value: 0.24 | ||||||

| Male | 60 | 46 | 83 | 33 | 76 | 30 | 81 | 27 | 81 | 34 | 86 | 24 |

| Female | 44 | 40 | 45 | 44 | 54 | 25 | 53 | 29 | 65 | 20 | 61 | 25 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | p-value: 0.63 | p-value: 0.22 | p-value: 0.13 | p-value: 0.28 | p-value: 0.38 | p-value: 0.47 | ||||||

| Yes | 20 | 19 | 29 | 12 | 32 | 8 | 31 | 9 | 27 | 13 | 31 | 8 |

| No | 84 | 67 | 99 | 65 | 98 | 47 | 103 | 47 | 119 | 41 | 116 | 41 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 grams) | p-value: 0.72 | p-value: 0.77 | p-value: 0.71 | p-value: 0.99 | p-value: 0.73 | p-value: 0.18 | ||||||

| Yes | 19 | 14 | 22 | 12 | 23 | 11 | 24 | 10 | 24 | 10 | 27 | 5 |

| No | 85 | 72 | 106 | 65 | 107 | 44 | 110 | 46 | 122 | 44 | 120 | 44 |

| Cleft type | p-value: 0.09 | p-value: 0.88 | p-value: 0.94 | p-value: 0.55 | p-value: 0.32 | p-value: 0.61 | ||||||

| Cleft lip only | 21 | 10 | 21 | 14 | 21 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 24 | 9 | 22 | 10 |

| Cleft palate only | 37 | 25 | 41 | 26 | 46 | 18 | 46 | 16 | 44 | 22 | 50 | 14 |

| Cleft lip with cleft palate | 46 | 51 | 66 | 37 | 63 | 28 | 65 | 32 | 78 | 23 | 75 | 25 |

| Presence of other birth defects | p-value: 0.21 | p-value: 0.33 | p-value: 0.12 | p-value: 0.56 | p-value: 0.16 | p-value: 0.80 | ||||||

| Yes (non-isolated orofacial cleft) | 65 | 46 | 51 | 36 | 50 | 28 | 56 | 26 | 57 | 27 | 63 | 20 |

| No (isolated orofacial cleft) | 39 | 40 | 77 | 41 | 80 | 27 | 78 | 30 | 89 | 27 | 84 | 29 |

| System characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Mother's primary health insurance | p-value: 0.11 | p-value: 0.17 | p-value: 0.85 | p-value: 0.39 | p-value: 0.75 | p-value: 0.01 | ||||||

| Private insurance | 60 | 53 | 67 | 55 | 73 | 31 | 80 | 30 | 84 | 32 | 81 | 38 |

| Public health insurance | 21 | 11 | 24 | 10 | 24 | 9 | 23 | 10 | 23 | 11 | 30 | 2 |

| Military | 2 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| Child's primary health insuranced | p-value: 0.05 | p-value: 0.007 | p-value: 0.17 | p-value: 0.18 | p-value: 0.63 | p-value: <0.0001 | ||||||

| Private health insurance | 51 | 41 | 50 | 47 | 55 | 25 | 63 | 25 | 67 | 24 | 57 | 38 |

| Public health insurance | 48 | 31 | 65 | 23 | 65 | 20 | 62 | 22 | 66 | 23 | 79 | 4 |

| Military | 2 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| Native/primary language in household | p-value: 0.38 | p-value: 0.97 | p-value: 0.78 | p-value: 0.80 | p-value: 0.88 | p-value: 0.43 | ||||||

| English | 99 | 82 | 23 | 72 | 124 | 52 | 127 | 53 | 138 | 52 | 140 | 46 |

| Other | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| System Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Average one-way travel time | p-value: 0.05 | p-value: 0.40 | p-value: 0.01 | p-value: 0.02 | p-value: 0.69 | p-value: 0.56 | ||||||

| 0–60 min | 61 | 33 | 66 | 35 | 73 | 20 | 76 | 21 | 71 | 28 | 73 | 22 |

| ≥ 61 min | 43 | 53 | 62 | 42 | 57 | 35 | 58 | 35 | 75 | 26 | 74 | 27 |

| Average one-way travel distance | p-value: 0.02 | p-value: 0.96 | p-value: 0.08 | p-value: 0.39 | p-value: 0.11 | p-value: 1.0 | ||||||

| 0–60 miles | 72 | 44 | 78 | 46 | 85 | 30 | 85 | 32 | 84 | 37 | 90 | 30 |

| ≥ 61 miles | 29 | 37 | 45 | 27 | 38 | 24 | 44 | 22 | 56 | 14 | 51 | 17 |

Bold P-values designate statistically significant results.

Twenty-four respondents had missing mother's age or had illogical response, so used North Carolina vital statistics data to impute maternal age.

Thirteen respondents (5.3%) marked White plus one other race, but were categorized as White for analysis.

`Other' included Hispanic, Black/African American, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander or an open-ended `Other' option.

Private health insurance = enrollment in the State Employee Health Plan or a private health insurance plan purchased from an employer or directly from an insurance company; Public health insurance = enrollment in North Carolina Health Choice (State Children's Health Insurance Program), Medicaid, Carolina ACCESS or Health Check; Military insurance = enrollment in Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services, TRICARE (formerly Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services) or the Veteran's Administration.

Primary cleft or craniofacial care was the first location where received services or the location where received most services.

Commonly associated maternal, child, and system characteristics for each of the five barrier subscales (pragmatics, skills, marginalization, expectations, and knowledge/beliefs) were also assessed. Over 40% of the pragmatic questions in Table 2 were significantly associated with travel time (4/9) and the number of CSHCN in the home (4/9), p < 0.05. Over 40% of skills-based questions were associated with household income (4/7), mother's and child's ethnicity (4/7 each), maternal health insurance coverage status (5/7), and primary language in the household (4/7), p < 0.05. Questions in the marginalization subscale were associated with maternal ethnicity (5/10), maternal healthcare coverage status (4/10), and primary language in the household (5/10), p < 0.05. Fifty-percent of knowledge and beliefs barriers (2/4) were associated with maternal healthcare coverage status, p < 0.05. There were no commonalities in characteristics associated with the expectation barriers subscale. Maternal health insurance status was significantly associated with three of the five barrier subscales and 34.3% (12/35) of all the barrier questions examined in the survey.

Discussion

Overall, the majority of perceived barriers to cleft and craniofacial care fell within the pragmatics subscale; eight of the ten most frequently reported barriers were in the pragmatics subscale, including the top six. Some of the greatest concerns for parents of children with OFCs are those of logistics and cost. Travel time was significantly associated with pragmatic barriers to care, which was unsurprising given that almost half of survey respondents traveled more than 1 hr to receive cleft and craniofacial care for their child in a previous study using the same data (Cassell et al., 2012, 2013). Mothers of children diagnosed with a cleft lip with cleft palate were almost three times more likely to travel greater distances when compared with mothers of children with cleft lip only (Cassell et al., 2012). These findings suggest that families of children requiring more intensive and complex care needed to travel farther to receive necessary cleft and craniofacial care.

Three of the five barrier subscales (skills, marginalization, and knowledge/beliefs) were associated with maternal healthcare coverage status. Maternal healthcare coverage, specifically a lack of coverage, has been associated with barriers to care and overall dissatisfaction of care for CSHCN (Ngui and Flores, 2006). Further research is needed on the impact of health insurance coverage and type of health insurance to better assess and address the concerns of parents of children with birth defects. While language barriers were not considered a major barrier to care, which could be due to the large proportion of respondents reporting English as their primary language, language barriers have been shown to be associated with more unmet needs, inadequate insurance, and a lack of care in CSHCN (Yu et al., 2004).

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Due to study limitations including the small sample size and the lack of variation in reported satisfaction of cleft care, an assessment of barriers to care and how they affect overall satisfaction could not be conducted. Our population of interest was specific to parents of children with OFCs in North Carolina, which may limit the generalizability of these results. However, the characteristics of our study sample were similar to that of mothers of children with OFCs in North Carolina overall, suggesting that our sample was representative of the population of interest. Additionally, parents may not be aware of all types of care needed for their child, which could lead to incorrect reporting of satisfaction and barriers to care. In addition, we cannot be certain of how parents interpreted “primary cleft and craniofacial care.” Parents could have interpreted this as the first place services were received or the place where most services were received. Self-reported data can introduce bias; however, studies have shown that maternal reports for child health care use are relatively accurate (D'Souza-Vazirani et al., 2005; Pless and Pless, 1995). Finally, because the survey was conducted in 2006, before the economic recession and the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, barriers to care (particularly concerning cost and logistics) and system characteristics (health insurance coverage for the mother and child) may have changed (Ghandour et al., 2014).

STUDY STRENGTHS

A strength of this study was that we used an active, state-wide, population-based birth defects registry to obtain the study population. Surveillance data allowed us to obtain and verify demographic information and access medical records to verify cleft diagnoses and presence of additional birth defects. Additionally, we used a validated barriers to care survey instrument that was developed in both English and Spanish (Seid et al., 2004). By using a validated survey, it allowed for both additional assurance that our perceived barriers were assessed appropriately and that these results potentially can be compared with barriers of care research in different populations of children with birth defects. Our study also sampled parents of children of varying ages. As pointed out by Nelson et al. (2012), most previous research focused on parent perceptions and experiences at the time of diagnosis. Our analysis examined barriers to care within the past year for children aged 2 to 6 and reported concerns that occur throughout childhood and not just after birth.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

While the majority of mothers reported being satisfied with their child's cleft and craniofacial care, this questionnaire provided insight into the perceived barriers and concerns of parents of children with OFCs. Improving access and availability of services and increasing the number of facilities may minimize the time needed to obtain care for children with OFCs and may alleviate some of the most common concerns for affected families. It is also important to emphasize the need for continuous quality health insurance for families with children with OFCs and other birth defects because healthcare coverage was associated with almost 50% of all the barriers assessed in this analysis.

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to quantify and assess perceived barriers of care for parents of children with OFCs using a population-based, state-wide sample from a birth defects registry and a validated barriers to care questionnaire. State-wide, population-based birth defects surveillance systems provide a large base population, can allow researchers to obtain access to medical records and other health services use information, and may provide the opportunity to generalize results to other populations. Future research assessing barriers to care and identifying interventions to improve access for parents and families of children with OFCs and other birth defects could draw on both surveillance programs and validated questionnaires.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the time and effort survey participants put into completing the surveys and providing thoughtful insight into the barriers they face when trying to receive cleft care for their child. We also thank the entire staff of the NCBDMP for their invaluable help, the phone interviewers with the North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics, and Eleanor Howell, Cinda Meyer, and Vanessa White for assisting in data collection and preliminary data analysis. The authors also thank Cara Mai and Richard Olney for coding assistance. Finally, the authors thank Michael Seid for allowing the use of his validated barriers to care survey instrument.

Supported in part by grant number U50/CCU422096 by the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conference presentations Parts of this manuscript were presented at the Florida Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association annual meeting, September 28–30, 2012. St. Petersburg, FL; North American Craniofacial Family Conference / AmeriFace Meeting, July 24–27, 2011, Las Vegas, NV; American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association annual meeting April 14–18, 2008, in Philadelphia, PA; National Birth Defects Prevention Network Annual Meeting, February 11–13, 2008. Washington, DC; and Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Conference Annual Meeting, December 11–14, 2007, Atlanta, GA.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA) Parameters for the evaluation and treatment of patients with cleft lip/palate or other craniofacial anomalies. ACPA; Chapel Hill, NC: 2009. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell CH, Mendez DD, Strauss RP. Maternal perspectives: qualitative responses about perceived barriers to care among children with orofacial clefts in North Carolina. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2012;49:262–269. doi: 10.1597/09-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell CH, Krohmer A, Mendez DD, et al. Factors associated with distance and time traveled to cleft and craniofacial care. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2013;97:685–695. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiri G, Warfield ME. Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1081–1091. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Vazirani D, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM. Validity of maternal report of acute health care use for children younger than 3 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:167–172. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour RM, Hirai AH, Blumberg SJ, et al. Financial and nonfinancial burden among families of children with special health care needs (CSHCN): changes between 2001 and 2009–2010. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerfeld CI, Hoffman JM, Ciol MA, Kartin D. Delayed or forgone care and dissatisfaction with care for children with special health care needs: the role of perceived cultural competency of health care providers. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:487–496. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Weissman G, Strickland BB, et al. Implementing community-based systems of services for children and youths with special health care needs: how well are we doing? Pediatrics. 2004;113:1538–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackashi JA, Dedlow ER, Wood-Dixon V. Health care for children with cleft lip and palate: comprehensive services and infant feeding. In: Wyszynski DF, editor. Cleft lip and palate: from origin to treatment. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- National Birth Defects Prevention Network (NBDPN) State birth defects surveillance program directory. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:1028–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW, McManus M, Fox HB, et al. Access to health care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2000;105:760–766. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:10–17. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW, Hung YY, Wright KK. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to care for children with special health care needs. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:247–254. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0247:raedia>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LP, Getzin A, Graham D, et al. Unmet dental needs and barriers to care for children with significant special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson P, Glenny AM, Kirk S, Caress AL. Parents' experiences of caring for a child with a cleft lip and/or palate: a review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:6–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngui EM, Flores G. Satisfaction with care and ease of using heath care services among parents of children with special health care needs: the roles of race/ethnicity, insurance, language, and adequacy of family-centered care. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1184–1196. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, et al. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:1008–1016. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pless CE, Pless IB. How well they remember: the accuracy of parent reports. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:553–558. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170180083016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riski JE. Evaluation and management of speech, language, and articulation disorders. In: Wyszynski DF, editor. Cleft lip and palate: from origin to treatment. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- Romaire MA, Bell JF, Grossman DC. Medical home access and health care use and expenditures among children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:323–330. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seid M, Sobo EJ, Gelhard LR, Varni JW. Parents' reports of barriers to care for children with special health care needs: development and validation of the barriers to care questionnaire. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:323–331. doi: 10.1367/A03-198R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seid M, Opipari-Arrigan L, Gelhard LR, et al. Barriers to care questionnaire: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change among parents of children with asthma. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner AC, Slifkin RT. Rural/urban differences in barriers to and burden of care for children with special health care needs. J Rural Heath. 2007;23:150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss RP, Cassell CH. Critical issues in craniofacial care: quality of life, costs of care, and implications of prenatal diagnosis. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland B, McPherson M, Weissman G, et al. Access to the medical home: results of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1485–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland BB, Singh GK, Kogan MD, et al. Access to the medical home: new findings from the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e996–e1004. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dyck PC, Kogan MD, McPherson MG, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:884–890. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehby GL, Cassell CH. The impact of orofacial clefts of quality of life and healthcare use and costs. Oral Dis. 2010;16:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdy MM, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Frias JL. Priorities for future public health research in orofacial clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007;44:351–357. doi: 10.1597/06-233.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SM, Nyman RM, Kogan MD, et al. Parent's language of interview and access to care for children with special health care needs. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:181–187. doi: 10.1367/A03-094R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SM, Sing GK. Household language use and health care access, unmet need, and family impact among children with special health care needs (CSHCN) Pediatrics. 2009;124:S414–S419. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1255M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]