Abstract

A critical element of successful sexual reproduction is the generation of sexually dimorphic adult reproductive organs, the testis and ovary, which produce functional gametes. The examination of different vertebrate species shows that the adult gonad is remarkably similar in its morphology across different phylogenetic classes. Surprisingly, however, the cellular and molecular programs employed to create similar organs are not evolutionarily conserved. We highlight the mechanisms used by different vertebrate model systems to generate the somatic architecture necessary to support gametogenesis. In addition, we examine the different vertebrate patterns of germ cell migration from their site of origin to colonize the gonad, and highlight their roles in sex-specific morphogenesis. We also discuss the plasticity of the adult gonad and consider how different genetic and environmental conditions can induce transitions between testis and ovary morphology.

Keywords: sex determination, germ cell, testis, ovary, sex reversal

INTRODUCTION

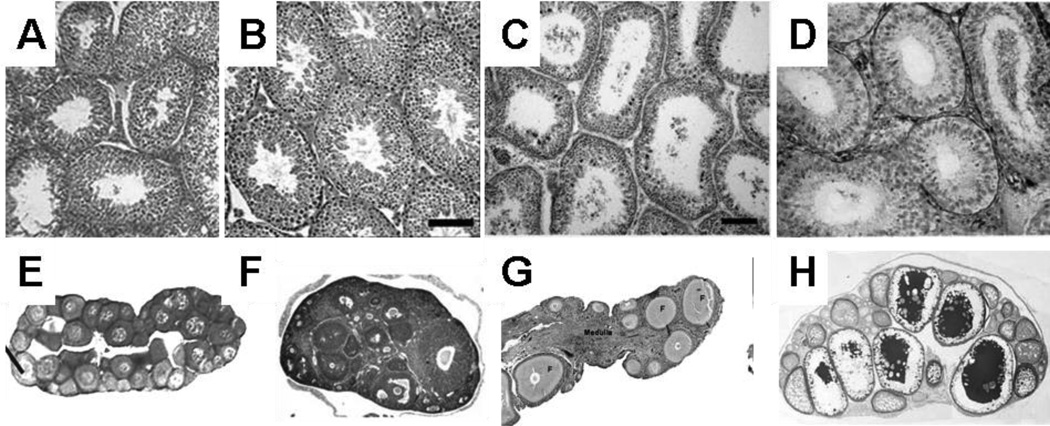

The propagation of all vertebrate species depends on the development of reproductive organs that support the differentiation of the germ cell lineage into two types of functional gametes: sperm and eggs. The morphological structures of the adult testis and ovary show a remarkable level of similarity across vertebrates (Figure 1). The testis is organized into testis cord structures in which somatic cells surround cohorts of germ cells that differentiate asynchronously to produce a continual supply of mature sperm. Spermatogonial stem cells persist in adulthood and renew the population of differentiating sperm throughout reproductive life. The steroidogenic cells are located outside and between testis cord structures, and they are the source of testosterone.

Figure 1.

Comparison of adult testis (a--d) and ovarian (e--h) structure in various species. (a) Human testis (image courtesy of Dr. Darl Swartz, Department of Animal Science, Purdue University). (b) Mouse testis (image from Zhang et al. 2003, copyright Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA). (c) Chicken testis (image from Song & Silversides 2007, used with permission from Poultry Science). (d) Musk turtle (Sternotherus odoratus) testis (image from Risley 1938, reprinted with permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.). (e) American leopard frog (Rana pipiens) ovary (image from Hayes et al. 2003, reproduced with permission from Environmental Health Perspectives). (f) Mouse ovary (image from Hosaka et al. 2004, copyright Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA). (g) Chicken ovary (image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Caceci, Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine). (h) Medaka ovary (image from Kurokawa et al. 2007, copyright Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA).

Ovaries show a similar conservation at this level of organization across species, with a characteristic cortical-medullary structure. Oocytes develop in the cortex, surrounded by granulosa cells and steroidogenic cells. In mammalian species, most experiments suggest that the oocyte population is not renewable (originally proposed by Zuckermann 1951). However, this is not true in egg-laying vertebrates in which oogonial stem cells are strongly implicated [and in some cases have been identified; for example, (Falconi et al. 2007, Grier 2000)].

Granulosa cell: –somatic support cell of the ovary that forms part of the follicle

In all vertebrates, the testis and ovary develop from the embryonic gonad, which is initially bipotential (referred to as indifferent in older literature). At some point during its development, this bipotential primordium makes a fate decision, referred to as primary sex determination, to differentiate as either a testis or an ovary. Once primary sex determination occurs, the production of hormones by the testis or ovary influences the differentiation of male and female secondary sex characteristics including the internal sex ducts, the external genitalia, and other sexually dimorphic features, such as pigmentation and body size.

Primary sex determination: –development of sexual phenotype in the somatic cells of the gonad

Bipotential (Indifferent): –undifferentiated state of the gonadal primordium that can develop into testis or ovary

The central importance of reproduction to survival of the species might have been predicted to be associated with a high conservation of the developmental process. However, despite the conservation of the structural morphology of the adult testis and ovary, the conservation of a common bipotential primordium, and the conservation of the overall logic of sex determination, there is a surprising amount of diversity in the signals that initiate primary sex determination and the mechanisms that lead to morphological development of the testis and ovary. In humans, the Y chromosome diverts the bipotential gonad primordium toward the male developmental pathway. Whereas this type of heterogametic (XX female/XY male) genetic sex determination (GSD) is common to all mammals and found among some other vertebrate classes, it is by no means the sole method of sex determination. In other phylogenetic groups, GSD operates in a manner in which the female is the heterogametic sex (ZZ male/ZW female). Additionally, in some groups, temperature, social or population status, or other extrinsic factors determine the sex of embryos, termed environmental sex determination (ESD). For a more detailed discussion of GSD and ESD mechanisms and transitions between them, we refer the reader to recent reviews and primary references therein (Barske & Capel 2008, Janzen & Phillips 2006, Marshall Graves 2008, Valenzuela 2008).

Genetic sex determination (GSD): – when chromosomal elements direct sexual phenotype regardless of environment

Environmental sex determination (ESD): – when extrinsic factors (e.g., temperature or behavioral cues) direct sexual phenotype

At the level of morphological development, vertebrates achieve differentiation of a testis or ovary through surprisingly different processes. In this discussion, we compare and contrast the various mechanisms that lead to the morphogenesis of the testis and ovary in vertebrate species, consider the role of germ cells in gonad development, and highlight the remarkable plasticity of this unique, bipotential organ.

MECHANISMS OF GONAD MORPHOGENESIS IN VARIOUS SPECIES

The architecture of the adult testis and ovary is very similar across a broad spectrum of vertebrate species. Here we discuss several model organisms and how somatic structures in the testis and ovary are generated. We highlight the differences in the cellular mechanisms during embryonic gonad development of the mouse, chick, turtle, and fish, and how these different mechanisms lead to the formation of the adult gonad.

Initial gonad formation and sex determination

Among mammals, sex determination and gonad morphogenesis have been studied most extensively in the mouse (Figure 2). The presumptive gonads begin as swellings of the epithelium overlaying the coelomic surface of the mesonephros at 10.0 days post coitum (dpc). Subsequent cell divisions within this epithelium give rise to much of the somatic component of the gonad (Karl & Capel 1998, Schmahl et al. 2000), although contributions from the mesonephros prior to 11.5 dpc have not been ruled out. At first, this bipotential primordium is morphologically indistinguishable between genetic males (XY) and females (XX).

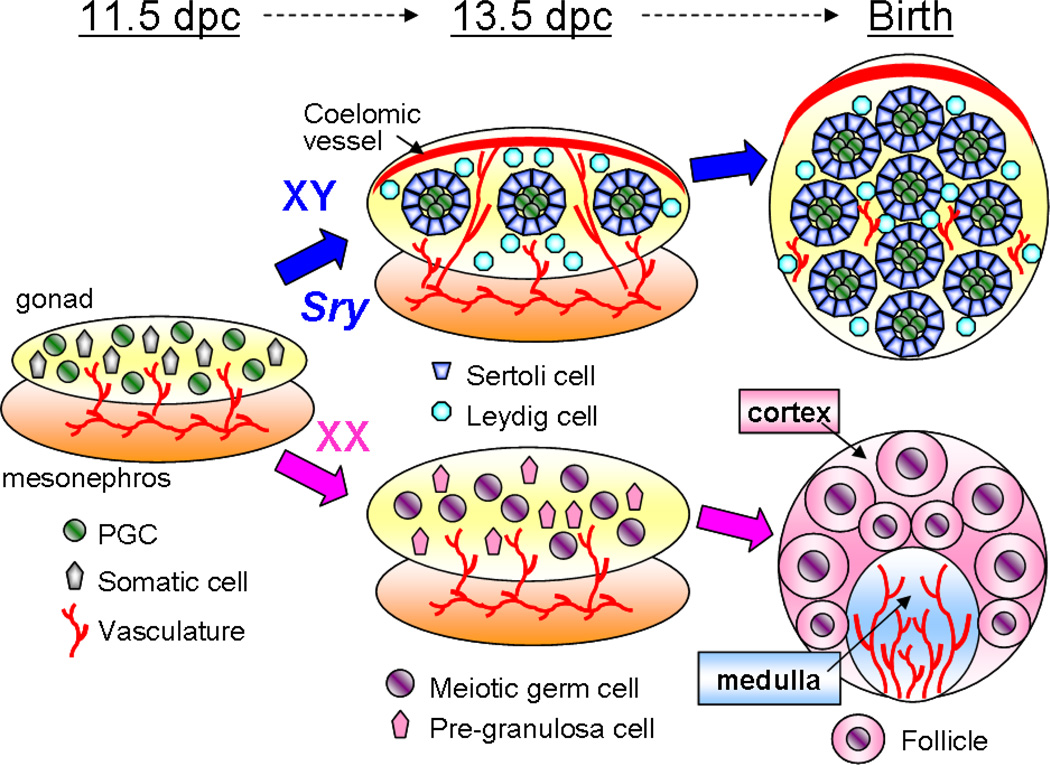

Figure 2.

Overview of mouse gonad morphogenesis. The expression of Sry directs development of the bipotential gonad toward the testis pathway. Characteristic testis morphology includes formation of testis cords, the coelomic arterial vessel, and Leydig cells. Characteristics of the ovary include entry of germ cells into meiosis, establishment of cortical and medullar domains, and folliculogenesis.

Sex-specific gonad differentiation begins when Sry (sex determining region of the Y chromosome) is expressed in a subset of somatic cells in the XY gonad between 10.5—and 12.0 dpc (Gubbay et al. 1990, Hacker et al. 1995, Koopman et al. 1990). Somatic cells that express Sry become Sertoli cells, the supporting cell lineage that associates intimately with the germline throughout spermatogenesis. Sry encodes a high mobility group (HMG) transcription factor that activates transcription of Sox9 (Sekido et al. 2004, Sekido & Lovell-Badge 2008). Sox9 encodes another closely related HMG transcription factor, and is necessary and sufficient for male development (Chaboissier et al. 2004, Vidal et al. 2001). Although Sry is restricted to mammals, Sox9 is associated with the testis pathway of numerous vertebrate species, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role for Sox9 in male differentiation (for a cross-species review, see Morrish & Sinclair 2002).

Sertoli cell: –somatic support cell of the testis that will be in close association with germ cells and support spermatogenesis throughout life

Testis differentiation

Downstream of Sox9, multiple aspects of male gonadogenesis have been characterized, including male-specific proliferation of the coelomic epithelium, formation of tubular testis cords, and the formation of a hallmark coelomic arterial vessel by 12.5 dpc (Brennan et al. 2002, Martineau et al. 1997, Schmahl et al. 2000). Lineage tracing experiments showed that the proliferation of the coelomic epithelium occurs in waves before and after 11.5 dpc. During the first wave, daughter cells from this epithelium delaminate and give rise to Sertoli cells; and in the second wave, exclusively to interstitial cells (Karl & Capel 1998, Schmahl et al. 2000). By 12.5 dpc, Sertoli cells and germ cells aggregate away from interstitial cells to form solid testis cords surrounded by a basal lamina. In this testis cord environment, primordial germ cells (PGCs) enter mitotic arrest beginning around 13.5 dpc and do not resume mitotic divisions until after birth. Testis cords remodel during fetal life and hollow out soon after birth to form the seminiferous tubules of the adult testis. Peritubular myoid cells in the interstitial space differentiate just after 12.5 dpc and encase testis cords throughout life.

Primordial germ cell (PGC): – the progenitor of sperm or eggs that has not yet sexually differentiated or entered meiosis

Between 12.5 and 13.5 dpc, a subset of interstitial cells also begins to differentiate into Leydig cells, which can be defined by morphology and the expression of steroidogenic enzymes such as 3β-HSD and p450 SCC. Clusters of Leydig cells are often found adjacent to vasculature, where they secrete hormones into the systemic circulation that virilize XY embryos. Although treatment of embryos with hormones can affect the primary sex determination decision in egg-laying species (see below) and in metatherian mammals (Coveney et al. 2001), this does not occur in eutherian mammals (McLachlan et al. 1975, Yasuda et al. 1985).

The complex male-specific vascular network in mice is formed via endothelial cell migration from the mesonephros into the gonad (Brennan et al. 2002, Combes et al. 2009, Cool et al. 2008, Coveney et al. 2008). The mesonephros is required for the assembly of testis cords, though sex determination and Sertoli cell specification are not affected in its absence (Buehr et al. 1993, Merchant-Larios et al. 1993, Tilmann & Capel 1999). When mesonephric cell migration was blocked using a permeable filter between the gonad and mesonephros, testis cords failed to form (Buehr et al. 1993), likely owing to failure of vascularization. In fact, specifically blocking the formation of the gonad vasculature at early stages of testis formation prevents the formation of testis cords, which suggests that endothelial cells are the mesonephric cell population that plays the critical inductive role in de novo cord morphogenesis (Cool et al. 2008, Combes et al. 2009).

Ovarian differentiation

In XX mouse gonads, no morphological differentiation is apparent when their XY counterparts are undergoing morphogenesis. Instead, PGCs remain evenly dispersed throughout the gonad and enter meiosis starting at 13.5 dpc, under the influence of retinoic acid signaling (Bowles et al. 2006). Few morphological changes have been described in the nascent ovary until a few days before birth, at which time many germ cells in the medullary regions undergo apoptosis, resulting in an enrichment of germ cells in the cortical region (Yao et al. 2004b). So-called cyst-like ovigerous cords have been observed in the late-stage fetal ovary (Merchant 1975, Pepling & Spradling 1998, Ruby et al. 1969). They consist of multiple germ cells adhered together in chains and surrounded by somatic cells (Pepling & Spradling 1998, 2001). Folliculogenesis occurs at perinatal stages. Each of the surviving germ cells is enclosed by several somatic follicle cells to form a primordial follicle. By this stage, vasculature, connective tissue, and other uncharacterized somatic cells are concentrated in the medullary zone. Experiments in mammals suggest that follicle (granulosa) cells are derived from the same lineage as Sertoli cells (Albrecht & Eicher 2001, Couse et al. 1999, Ito et al. 2006), although this has not been determined conclusively.

Follicle: –the basic unit of the ovary, which contains the oocyte surrounded by somatic cells

Other species

Although the mouse system may be the most thoroughly studied in the field of mammalian testis morphogenesis, it may not be representative of all mammals. Whereas cord formation is a male-specific phenomenon in the mouse, it has been noted that cords of epithelial cells interspersed with mesenchymal cells are present in undifferentiated male and female gonads in humans, macaques, and pigs (Fouquet & Dang 1980, Francavilla et al. 1990, Pelliniemi & Lauteala 1981, Satoh 1991). We refer to these cord-like structures that are formed in both sexes prior to overt sex determination or sexual differentiation of the gonad as primitive sex cords. As we highlight below, the presence of primitive sex cords in both sexes during bipotential stages seems to be a nearly universal aspect of vertebrate gonad morphogenesis, although their location is not always consistent.

Initial gonad formation and sex determination

Whereas some aspects of chick gonad differentiation (Figure 3) are similar or analogous to mammals, one main difference is in their mechanism of sex determination, which depends on a ZZ/ZW GSD system. Similar to mammalian systems, the presumptive gonads in the chick embryo are derived from the intermediate mesoderm on the surface of the mesonephros (which serves as a kidney in nonmammalian species). As in the mouse, the gonad is initially in a bipotential phase in which male and female gonads are morphologically indistinguishable. By day 4.5 of development, the gonad primordium (unlike the mouse) is already made up of two basic compartments: the cortex and the medulla. The cortex is derived from proliferation of the coelomic epithelium, and the medullary zone is made up of primitive sex cords interspersed with mesenchymal cells (Clinton & Haines 1999, Smith & Sinclair 2004).

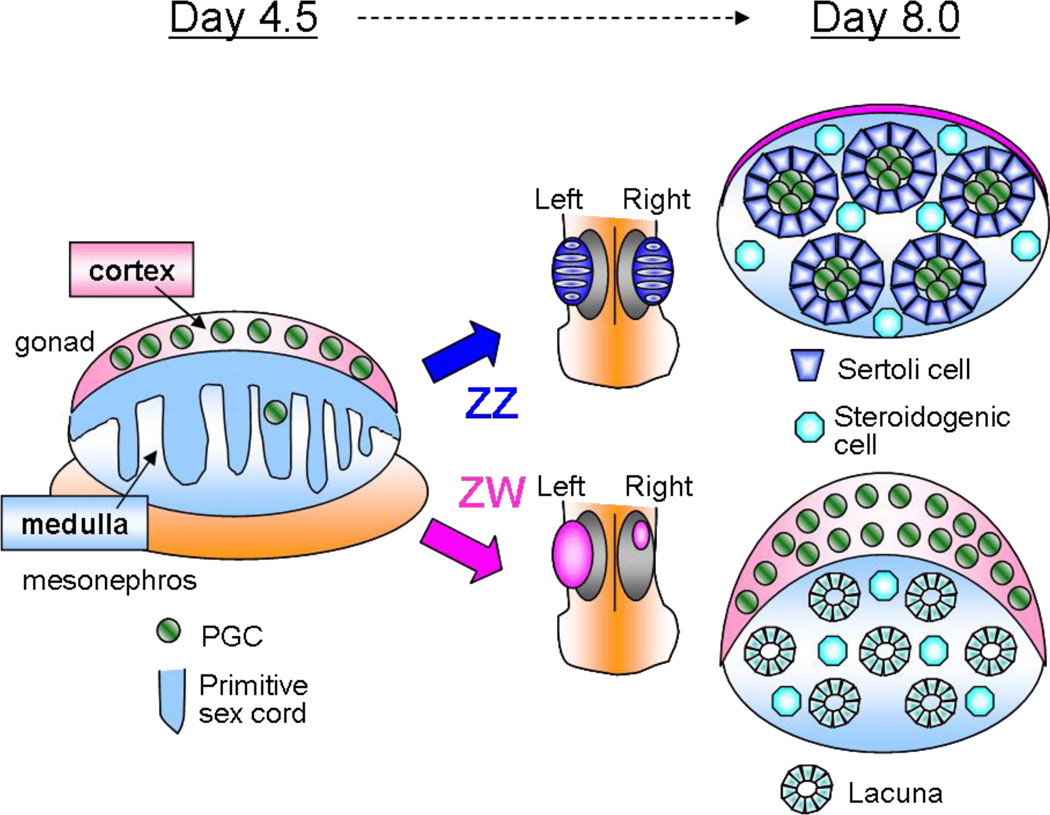

Figure 3.

Overview of chick gonad morphogenesis. The bipotential gonad is compartmentalized into a cortex and medulla. Primitive sex cords develop into testis cords in the ZZ (male) gonad and lacunae in the ZW (female) gonad. In the female, only the left gonad grows into a functional ovary. The cortical domain expands in the ovary, whereas it regresses in the testis.

By day 6.5, the morphological differences between testes and ovaries are readily apparent. In ZZ males, the PGCs associate with somatic cells in the medullary cords, which proliferate and differentiate into Sertoli cells (similar to the situation in mouse, in which Sertoli cells are in constant close contact with PGCs). The medullary cords then expand in size and become seminiferous cords in the adult testis. In contrast to mammals, no hallmark vasculature is present in the nascent testis. In ZW females, PGCs remain in the cortical region, where they undergo meiosis later in development and eventually form follicles.

Although the same cell types are present in mouse and chick gonads, their origins may be different, and are still a matter of controversy. Using electroporation of an injected lacZ reporter plasmid] or a dye to label coelomic epithelial and mesonephric cells in the chick ZZ gonad, Sekido and Lovell-Badge showed that mesonephric cells contributed to Sertoli cells, steroidogenic cells, and other interstitial cells, whereas labeled coelomic epithelial cells only gave rise to nonsteroidogenic interstitial cells (Sekido & Lovell-Badge 2007). In contrast to this study, other reports suggested that proliferating coelomic epithelial cells give rise to the primitive sex cords (Merchant-Larios et al. 1984, Rodemer-Lenz 1989, Smith & Sinclair 2004). Ultrastructural analysis revealed a common basal lamina between the coelomic epithelium and the primitive sex cords (Merchant-Larios et al. 1984), suggesting that either the epithelium directly gives rise to the primitive sex cords or there is a union of epithelial and medullary cells at some point during gonad morphogenesis that forms the definitive testis cords.

Whereas cell migration from the mesonephros is essential for male-specific development in the mouse (Buehr et al. 1993, Tilmann & Capel 1999), experiments in which the chick mesonephros was removed did not hinder normal gonad differentiation (Merchant-Larios et al. 1984). Additionally, quail-chick chimera studies confirmed that gonad development does not depend on the mesonephros, although quail mesonephric cells could enter the chick gonad in those experiments (Rodemer et al. 1986,Rodemer-Lenz 1989). More recent xenograft experiments using a labeled mouse mesonephros also provided evidence for mesonephric cell migration into the male chicken gonad (Smith et al. 2005). Some of the migrating cells were endothelial in the xenografts, but developing chicken testes normally do not show sex-specific vascularization such as the coelomic vessel that is characteristic of the mouse testis (Smith et al. 2005). There is no evidence that cell migration directs testis cord formation in the chick testis, in which the development of cords occurs by expansion of the preexisting medullary cords, presumably based on a different set of inductive cues than in the mouse. It is possible that mesonephric endothelial cell migration is specific to mammals.

Asymmetric ovarian formation

In a rather unique phenomenon among vertebrates, ZW female embryos exhibit asymmetric gonad differentiation in which only the left gonad develops into an ovary, whereas the right gonad regresses and fails to differentiate further. In the left female gonad, as opposed to the male, the cortical compartment undergoes extensive proliferation and growth in size, whereas the medullary cords become hollow and form lacunae. In the right gonad, medullary cords vacuolate and form lacunae, but the cortical region fails to undergo the characteristic proliferation of the left gonad. The cells of the lacunae may help absorb and clear out large amounts of yolk from bursting follicles in the chicken ovary (Nili & Kelly 1996).

Lacuna: a lumen or cavity, often surrounded by epithelial cells

The asymmetric development of the gonads in chick is regulated by the Pitx2 transcription factor, which is asymmetrically localized to the left gonad and is sufficient to rescue the right gonad from degeneration (Guioli & Lovell-Badge 2007). The mechanism of asymmetry is mediated via retinoic acid (RA) signaling. RA is only produced in the right gonad, where it suppresses SF-1 and estrogen receptor alpha. In the absence of RA in the left gonad, cyclin D1 is upregulated and stimulates cell division (Ishimaru et al. 2008, Rodriguez-Leon et al. 2008).

Initial gonad formation and sex determination

Another model system that has been used to study sex determination and gonad development is the red-eared slider turtle, Trachemys scripta (Figure 4). Similar to other reptiles and most crocodilians, sex determination in T. scripta is sensitive to temperature (Bull & Vogt 1981, Wibbels et al. 1991), as opposed to the genetic mechanisms of mouse and chick. In T. scripta, eggs incubated in the laboratory at 26°C, the male-producing temperature (MPT), yield nearly 100% males, whereas those incubated at 31°C, the female-producing temperature (FPT), yield nearly all females. Although underlying genetic variation surely exists, and probably influences sex determination under natural conditions, it can be overridden by incubation temperature.

Male-producing temperature (MPT): –incubation temperature at which 100% of eggs hatch as males

Female-producing temperature (FPT): –incubation temperature at which 100% of eggs hatch as females

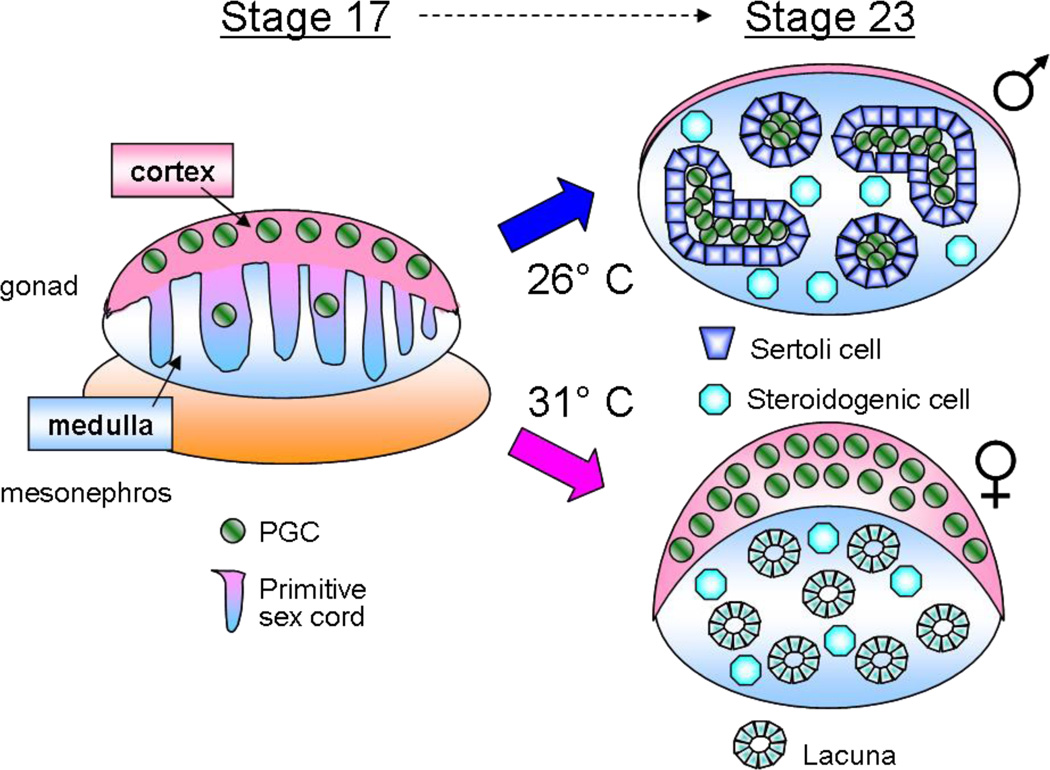

Figure 4.

Overview of turtle (T. scripta) gonad morphogenesis. Incubation of eggs at 26°C, the male-producing temperature (MPT), leads to regression of the cortical domain, whereas incubation at 31°C, the female-producing temperature (FPT), leads to expansion of the cortical domain. Primitive sex cords are continuous with the coelomic epithelium and exist in all gonads at the bipotential stage. They become testis cords at the MPT and lacunae at the FPT.

As in the mouse and chick, the gonad primordia of the turtle arise as paired swellings on the surface of the mesonephric kidney and are initially indistinguishable between the sexes. From the earliest stages, PGCs are mainly localized in the thickened coelomic epithelium (Yao et al. 2004a). This is in contrast to mice, in which germ cells are scattered throughout the gonad and are rarely localized in the coelomic epithelium. As the bipotential gonad thickens, primitive sex cords continuous with the coelomic epithelium are evident at both the MPT and FPT. At the FPT, germ cells stay in the surface cortical domain of the gonad and the remnants of the degenerating sex cords form lacunae in the medullary region. However, at the MPT, the sex cords are populated by PGCs, expand, sever their connections to the coelomic epithelium, and differentiate into mature Sertoli cell-lined testis cords (Yao et al. 2004a). As in the mouse, an increase in proliferation of somatic cells is associated with the male pathway (for a review, see Yao & Capel 2005).

Mechanism of sex cord formation

Whereas lineage tracing experiments in the mouse demonstrated that proliferating coelomic epithelial cells delaminated and entered the interior of the gonad (Karl & Capel 1998), lineage tracing of the coelomic epithelium in the turtle indicated that clonal progeny of labeled cells stay close to the original labeled populations (Yao et al. 2004a). This result suggested that turtle sex cords arise by invagination of the coelomic epithelium rather than by de novo assembly. Consistent with this hypothesis, anti-laminin antibody localization shows that the basal laminae of the sex cords are at first continuous with the lamina of the coelomic epithelium (Yao et al. 2004a).

This evidence suggests that the origin of primitive sex cords in turtles is different from other species in which these structures are seen histologically deep in the medullary region, well separated from the coelomic epithelium (Satoh 1991). Whereas mesonephric cell migration is required for testis cord formation in the mouse, xenografts using GFP-expressing mouse mesonephric tissue apposed to a turtle gonad did not result in any mesonephric cell migration (Yao et al. 2004a). Although this result may be inconclusive owing to potential incompatibility of the tissues between turtles and mice, other evidence is consistent with this result. Experiments with a different turtle species (Lepidochelys olivacea) showed that gonads removed from the mesonephros could still develop testis cords (Moreno-Mendoza et al. 2001), similar to results in chick (see above). These data support the possibility that the migration of mesonephric endothelial cells is only required in systems in which de novo assembly of testis cords occurs. Species in which primitive sex cords exist and differentiate into mature testis cords (e.g., chick and turtle) rely on fundamentally different inductive mechanisms to assemble cord structures, despite the fact that the structure of adult testis cords appears quite similar across all vertebrates.

Fish

Fish species exhibit a stunning variety of sex determination schemes and gonad morphogenetic mechanisms. There are gonochoristic species, hermaphroditic species, and several species that have the ability to switch sexes multiple times during the course of their life. The plasticity of sex determination and sexual phenotype in fish demonstrates an extreme adaptability that is well suited to a changing aquatic environment. Despite this great diversity among fish species, two model systems have been the focus of much attention in the field of gonad development: the zebrafish, Danio rerio, and the medaka, Oryzias latipes.

Gonochoristic: –a species that can only exhibit one sexual phenotype or produce one type of gamete at a time

Hermaphroditic: –a species that can simultaneously exhibit male and female phenotypes or produce eggs and sperm at the same time

Zebrafish sex determination

In contrast to mammals and chickens, which have clearly heteromorphic sex chromosomes (XX/XY and ZZ/ZW), zebrafish do not have clearly identifiable sex chromosomes (Sola & Gornung 2001, Traut & Winking 2001). However, experiments indicate a genetic component to sex determination that is probably polygenic and complex. In addition to some form of complex genetic sex determination, zebrafish sex is sensitive to environmental influences. High temperature, addition of aromatase inhibitor, and addition of exogenous estrogen have been reported to effectively induce sex reversal in zebrafish embryos (Fenske et al. 2005, Fenske & Segner 2004, Uchida et al. 2004). Hypoxic conditions are implicated in an increased expression of male steroidogenic enzymes such as 3β-HSD and CYP11A, leading to a male sex-biased population (Shang et al. 2006). In addition, population density and food availability are linked to biased sex ratios (Lawrence et al. 2007).

Zebrafish initial gonad formation

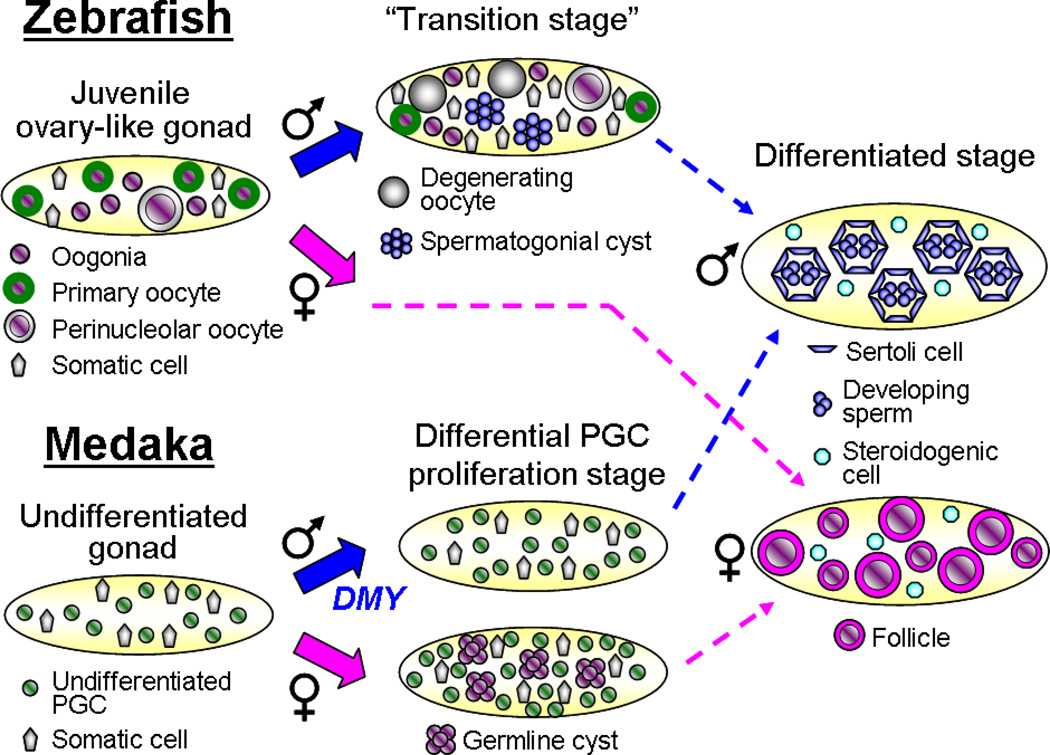

Zebrafish gonad formation (Figure 5) is classified as juvenile hermaphroditism, or more specifically, protogyny, in which all embryonic gonads, regardless of genetic elements, begin as presumptive ovaries (Takahashi 1977). Because rearing conditions can affect growth and development of zebrafish, there are reported discrepancies in the duration of the bipotential period: anywhere from 5 weeks postfertilization (pf) to 11 weeks pf or later (e.g., (Maack & Segner 2003, Slanchev et al. 2005, Takahashi 1977, Uchida et al. 2002)). A detailed description of zebrafish morphological development has been previously published (Maack & Segner 2003). PGCs are initially clustered in groups of 10–20 cells in association with the somatic gonadal mesoderm. After arrival in the gonad, three types of germ cells are observed, and all are consistent with a female fate according to morphological and cytological criteria: oogonia (type 1), early meiotic stage primary oocytes (type 2), and perinucleolar oocytes (type 3).

Protogyny: –sex change in the direction from female to male (as opposed to protandry)

Figure 5.

Overview of zebrafish (D. rerio) and medaka (O. latipes) gonad morphogenesis. All undifferentiated zebrafish gonads have ovarian characteristics and undergo a transition in males in which oocytes degenerate while spermatogenic cysts begin to form. The absence of this transition state indicates commitment to ovarian development. In medaka, increased PGC proliferation and generation of cyst-like germ cell clusters are the first indicators of female sex determination and occur prior to any somatic sexual dimorphism. In gonads differentiating as testes, PGC proliferation is much lower.

Zebrafish transition to sexual dimorphism

Gonads containing mostly oogonia and early meiotic stage primary oocytes are considered indifferent gonads, whereas those containing a complement of perinucleolar oocytes are classified as ovaries. During the bipotential period, some gonads are categorized as altered ovaries owing to a decrease in oocyte number and some aberrant oocyte morphology. In these gonads, oocytes are no longer tightly packed together, and their shape is irregular and indicative of degeneration. Uchida and colleagues demonstrated that the loss of primary oocytes in the juvenile ovary is mediated by apoptosis (Uchida et al. 2002). The number of apoptotic oocytes is significantly higher in presumptive males than in females, leading to the hypothesis that apoptosis of germ cells is the mechanism for breakdown of female structures that might hinder testis formation. Additionally, the number of somatic stromal cells dramatically increases in altered ovaries. Gonads are characterized as presumptive testes when they contain few perinucleolar oocytes, and instead possess numbers of undifferentiated germ cells that are sometimes organized around a central lumen, reminiscent of spermatogonial cysts. Presumptive testes contain cyst-like clusters of spermatocytes and spermatids among degenerating oocytes, representing a transition stage in which male and female tissues are in close proximity to each other. Further differentiation of testes is marked by a peripheral localization of somatic stromal cells and an array of developmental stages of sperm. Occasionally, a few degenerative oocytes are still present in testis tissue, but these disappear by adult stages.

Medaka sex determination

In contrast to zebrafish, the medaka, O. latipes, has an XX/XY genetic method of sex determination similar to mammals. As in mammals, there is a dominant sex-determining gene on the Y chromosome called DMY (Matsuda et al. 2002, 2007). Based on loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments, DMY is necessary and sufficient to trigger testis development and male sex determination in this species. DMY is a homolog of the mammalian Dmrt1 gene that is involved in testis differentiation in mice (Raymond et al. 2000), suggesting some conservation of the overall machinery of testis development. DMY and mammalian Dmrt1 share a DM zinc-finger-like DNA-binding domain that was originally found in the sex-determining genes doublesex in Drosophila and mab-3 in C. elegans (Raymond et al. 1998). However, in mouse, Dmrt1 appears to be downstream of the primary sex determination steps. Although it first appeared that DMY might represent a global master sex determination switch in fish, the DMY gene is absent in other fish species, even some other Oryzias medaka species (Kondo et al. 2003, Volff et al. 2003). The identification of a primary sex-determining gene completely unrelated to mammalian Sry suggests that the entry point into the male pathway may vary in different species. DMY and Sry may not have the same cellular functions, but both establish genetic cascades that trigger the male pathway (see Barske & Capel 2008).

Regardless of the well-defined genetic basis for sex determination in medaka, there is a great deal of plasticity in sex determination in this species. For example, administration of estradiol to early embryos causes sex reversal (Iwamatsu et al. 2005, Kobayashi & Iwamatsu 2005), highlighting the importance of hormones in sex determination, especially in aquatic and egg-laying species. This effect has ecological significance, as industrial pollutants often act as estrogen mimetics and thus can adversely affect reproduction in wild fish species.

Medaka mechanism of gonad sexual dimorphism

The mechanism of gonad development in medaka (Figure 5) provides a contrast to zebrafish. Whereas zebrafish undergoes protogynous juvenile hermaphroditism, medaka achieves gonochorism in a more direct manner. Prior to any somatic morphological difference between the sexes, the first sexual dimorphism in the medaka gonad is an increase in the number of PGCs in the female gonad by stage 38 (prior to hatching) (first noted in Satoh & Egami 1972; onset of sexual dimorphism quantitated in Kobayashi et al. 2004). In addition, meiosis is first observed in female germ cells one day after hatching (dah), whereas spermatogenesis begins around 20 dah. Not only is the rate of proliferation different between the sexes, but the pattern of PGC division is also distinct. Two types of proliferation occur: In type I, PGCs intermittently and independently proliferate in a linear manner, whereas in type II, cells synchronously divide to increase their numbers in an exponential fashion (Saito et al. 2007, Tanaka et al. 2008). Type I division daughter PGCs all appear identical to one another, and are found isolated in the gonad surrounded by somatic cells. In type II division, PGCs form clusters of cells reminiscent of germline cysts formed via incomplete cytokinesis. In the early XY gonad, only type I PGCs are present, whereas in XX gonads, both types are present. Whereas sexual dimorphism of germ cell proliferation likely reflects dimorphism of local or systemic signals, no earlier dimorphic somatic markers or morphology are known.

The first sex-specific morphology observed is the formation of the acinus, the precursor of the testis seminiferous tubule, in the XY gonad at around 10 dah (Kanamori et al. 1985), even though the first expression of the sex-determining switch DMY is observed well before hatching (Kobayashi et al. 2004). This is also in contrast to mammals, in which testis cord formation is initiated immediately after the expression of Sry. Another difference worth noting is the Sox9 expression patterns of the two species. The expression of Sox9a2 (a medaka testis-specific isoform of Sox9) is maintained in both sexes early on in medaka, even during the time points when germ cell number dimorphism is evident. However, Sox9a2 becomes male-specific when the acinus forms (10 dah) (Nakamoto et al. 2005), consistent with the idea that the male-specific function of Sox9a2, like mammalian Sox9, is to initiate (or maintain) tubule morphogenesis in the testis. Prior to sexual differentiation, there do not appear to be any primitive sex cords in medaka (Yamamoto 1953). Therefore testis tubules likely form, as in mouse, via de novo assembly.

GERM CELLS IN GONAD FORMATION

Germ Cell Migration

In all vertebrates, germ cells arise at a distant site, travel to the gonad, and arrive during the bipotential stage. However, the manner in which they arrive in the somatic compartment of the gonad is distinct and is impacted not only by the manner of specification of the germline, but also the physical path the PGCs travel through the embryo (for a more detailed review, see Molyneaux & Wylie 2004).

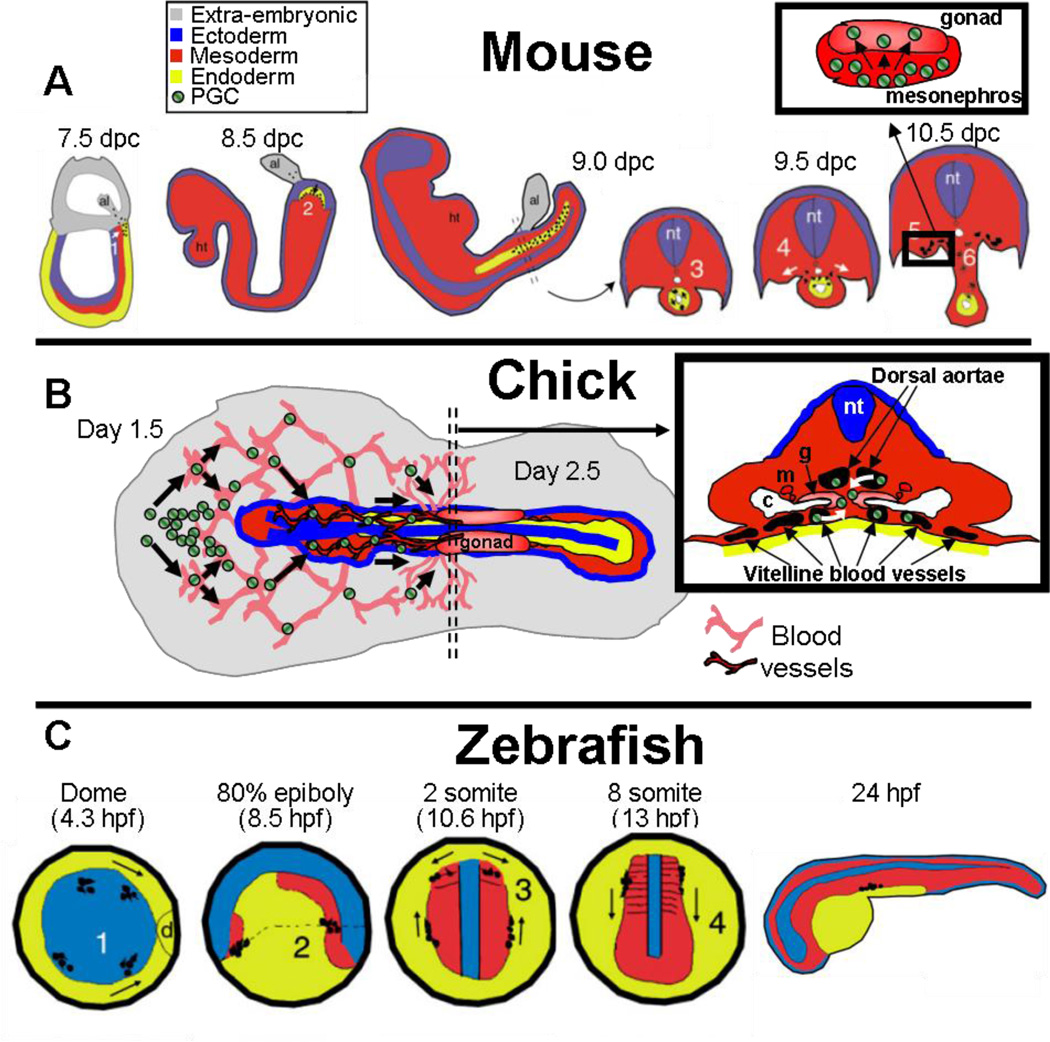

Mouse

In mouse (Figure 6a), a cluster of PGCs arises in the epiblast near the base of the allantois around 7.25 dpc, as a result of induction by nearby somatic cells (for reviews, see Durcova-Hills & Capel 2008, McLaren 2003). PGCs divide and migrate through the gut and dorsal mesentery to colonize the gonadal primordium between 10.5—and 11.5 dpc (Molyneaux et al. 2001), and enter the gonad in a path through the mesonephric tissue (Figure 6a). By 11.5 dpc, somatic and germ cells are randomly interspersed throughout the gonad anlagen. At this stage, germ cells show no preference for any domain of the gonad in either sex, but are rarely seen near the coelomic epithelium.

Figure 6.

Different mechanisms of germ cell migration to the gonad in different species. (a) In mice, germ cells are specified at the base of the allantois (al) and enter the gut endoderm (1–2), after which they are passively transported by gut extension, and migrate out the dorsal mesentery to arrive in the gonadal mesoderm (3–6). ht, heart; nt, neural tube. Inset shows migration of the germ cells through the mesonephros into the gonad. (b) In chick, germ cells aggregate in the anterior extraembryonic region, and then enter into the extraembryonic vascular system. Germ cells then extravasate (or pass through the walls of a blood vessel into the surrounding tissue) through the dorsal aortae or through the extraembryonic vitelline vessels into the region near the coelomic epithelium of the presumptive gonad. c, coelom; g, gonad; m, mesonephric ducts/tubules; nt, neural tube. Germ cells not to scale. (c) In zebrafish, germ cells are specified in four clusters during early cleavage stages. They first move dorsally (d) during gastrulation (1), and then collect at the head-trunk mesoderm border (2). After proceeding toward an intermediate target in the lateral plate mesoderm (3), the germ cells migrate posteriorly to the gonad (4). The details of their entry into the gonad are unknown. Images in (a) and (c) were reproduced from Molyneaux & Wylie 2004, with permission of The International Journal of Developmental Biology. Germ cells in low-magnification images in (a) and (c) are represented by small black dots.

Chick

In chicks, as in mammals, the PGCs migrate long distances to colonize the gonad, yet they utilize a distinct mechanism. Rather than migrating through the gut mesentery as in mouse, chick PGCs travel through the bloodstream to arrive in the gonad (Meyer 1964; Nakamura et al. 2007; Tsunekawa et al. 2000; Ukeshima et al. 1987, 1991) (Figure 6b). At first, PGCs aggregate in the extraembryonic region anterior to the head and then enter extraembryonic blood vessels, and travel posteriorly. The germ cells can enter the gonadal mesoderm either by traveling through embryo via the dorsal aorta or through the extensive network of extraembryonic vitelline vessels that leads into the region immediately anterior to the gonadal mesoderm. After extravasating from smaller capillaries near the coelomic epithelial surface, PGCs migrate into the somatic component of the gonad. In addition to immunohistochemical localization of Vasa-expressing cells within blood vessels, anti-Vasa immunostaining of circulating blood samples confirms that PGCs are indeed in the bloodstream (Nakamura et al. 2007). PGCs are initially concentrated in the chick coelomic epithelial surface upon initial colonization of the gonad (Fujimoto et al. 1976), in contrast to their more interior position in the mouse.

Turtle

Although germ cell origin and migration in turtles has not been thoroughly characterized, previous studies have shown that PGCs migrate through the dorsal mesentery to colonize the gonad (Pieau et al. 1999), similar to mice. However, in contrast to mice, germ cells in the early undifferentiated T. scripta gonad are concentrated in the coelomic surface domain rather than the mesonephros (Yao et al. 2004a). Although the initial location of germ cells in undifferentiated chick and turtle gonads are similar, there have been no reports of bloodstream-mediated germ cell migration in the turtle. The localization of PGCs in the cortical region versus their dispersion throughout the tissue likely reflects basic differences in domain organization in gonads of different species.

Zebrafish

Zebrafish illustrate yet another way in which germ cells can colonize the gonad (Figure 6c). As in other lower vertebrates and Drosophila, zebrafish germ cells are specified by an allocation of cytoplasmic determinants including the RNA-binding protein Vasa. PGCs arise at multiple places in the embryo, within four clusters located at the intersections of the first two cleavage planes during embryogenesis (Braat et al. 1999, Yoon et al. 1997). PGCs then migrate from four unique cluster points in the embryo to their final residence at the site of the somatic component of the gonad by 24 hours pf, using multiple intermediate target sites along the way (Weidinger et al. 1999). The exact mechanisms of germ cell entry into the gonad are unclear, because markers of the somatic gonad are unknown at very early stages. However, reports in both zebrafish and medaka have documented germ cells associated with the gut and mesentery during final migration stages (Braat et al. 1999, Hamaguchi 1982), suggesting some similarity to the route mouse germ cells take to colonize the gonad.

Requirement for Germ Cells in Gonad Differentiation

In addition to unique mechanisms of germ cell migration and colonization of the gonad, there are also different roles for germ cells in the morphogenesis of the gonad. In some species, the presence of germ cells is required for primary sex determination, whereas in others it is required at later differentiation stages or not at all (Table 1).

Mammals

The reliance of the somatic gonad on the presence of germ cells is complex in mammals. Agametic XY mouse and rat gonads do not undergo early sex reversal (Coulombre & Russell 1954, Handel & Eppig 1979, Merchant 1975, Mintz & Russell 1957), because germ cells are not required in males for testis cord formation or for the production of male hormones. However, the loss of meiotic germ cells in perinatal ovaries causes disruptions in postnatal ovarian structure and folliculogenesis (Guigon et al. 2005, Mazaud Guittot et al. 2006, Merchant 1975, Merchant-Larios & Centeno 1981). This observation is consistent with humans, in which sterile XO females who have lost germ cells prior to adulthood [Turner syndrome (Turner 1938)] have only a streak-like gonad with no overt ovarian morphology. Similar transformation of the ovary is also seen in menopausal and chemotherapy-treated individuals who have lost oocytes (Howell & Shalet 1998, Koyama et al. 1977, Vanderhyden 2005) (see below for further discussion).

Female germ cells in mouse can also act early in gonadogenesis to inhibit testis formation (Yao et al. 2003), suggesting a conserved role for germ cells to stabilize, if not promote, an ovarian fate. Germ cells do not seem to be required for ovarian morphology until perinatal stages, but these results are difficult to interpret given that early ovarian morphology has no clear landmarks.

Chick

Using the criteria of morphology and hormone production, it appears that chick embryonic gonadal development also can proceed in the absence of germ cells. In experiments in which the removal of the anterior germinal crescent eliminated nearly all PGCs from the embryo, ovary and testis differentiation occurred normally until up to 20 days of incubation (near the time of hatching) (McCarrey & Abbott 1978). In addition to this morphological assessment, a functional analysis found that steroid hormone production and reproductive duct differentiation in both sexes were unaffected in agametic gonads (McCarrey & Abbott 1982). Adult male chickens that were sterilized by gamma irradiation showed normal testis morphology, with Sertoli-cell-lined seminiferous tubules and Leydig cells (Trefil et al. 2003, 2006). In addition, these testes were capable of producing sperm after transplantation of donor spermatogenic stem cells, providing further evidence for normal somatic testis function in the absence of germ cells (Trefil et al. 2006). However, adult female chickens that had been exposed to 3H-thymidine during embryonic stages, which causes sterilization of the left ovary (Callebaut 1968), showed signs of masculinization. In addition to male-specific plumage and comb, the ovary showed abnormal structure and the presence of testis-like tubules (Callebaut 1969). These results are similar to observations in mice, in which germ cells are not required in the testis, but are critical for ovarian function.

Turtle

Similar to chick, it appears that germ cells do not play an essential role in embryonic gonad morphogenesis in T. scripta; busulfan-mediated depletion of PGCs did not alter the morphological development of early testes or ovaries by the time of hatching (DiNapoli & Capel 2007). Because the period to sexual maturity is very long in T. scripta (3–4 years), the effect of germ cell loss on adult hormone levels, gonad characteristics, or secondary sex characteristics was not investigated.

Fish

There is a critical, active role of the germline in gonad differentiation of fish. Germ-cell-depleted medaka (Kurokawa et al. 2007) and zebrafish (Siegfried & Nusslein-Volhard 2008, Slanchev et al. 2005) invariably develop as adult males using criteria of body appearance and behavior. The loss of germ cells causes the loss of female-specific aromatase-expressing lineages and the gain of male-specific steroidogenic lineages (concomitant with the loss of aromatase expression) (Kurokawa et al. 2007). Initial development of the germ-cell-less gonad is unaffected prior to sex determination and differentiation stages. However, the male-specific genes sox9a and amh and the Leydig cell marker cyp11b are maintained, whereas female-specific genes such as foxL2 and aromatase are downregulated (Siegfried & Nusslein-Volhard 2008). Some debate is ongoing about the role of germ cells in male fish: In one report the agametic gonad remains rather undifferentiated (Slanchev et al. 2005), whereas another report documents normal testis tubule formation (Siegfried & Nusslein-Volhard 2008).

It is likely that a threshold of germ cells is required to stabilize the female fate in fish. Homozygosity of a null allele of zebrafish piwi (ziwi) caused complete germ cell loss and 100% phenotypic males (Houwing et al. 2007). Conversely, in a hotei medaka mutant, PGCs overproliferate and cause XY male-to-female sex reversal. The hotei mutation is a point mutation in the amh type II receptor gene (amhrII) (Morinaga et al. 2007). Based on these results, proliferating germ cells act either to recruit bipotential cells to the granulosa cell fate or to repress a predisposed male fate in fish.

PLASTICITY OF GONAD PHENOTYPES: THE TRANSITION BETWEEN TESTIS AND OVARY

Whereas all the species we have described so far are gonochoristic and present straightforward and rather stereotyped mechanisms for gonad morphogenesis, other species exhibit a great deal more plasticity in sex determination. These species, for example, certain seasonally breeding birds and rodents, show surprising flexibility in their adult gonad phenotype. Other species (mostly fish) even have the ability to change sex multiple times during adult life. The capability of these species to alter the balance of cell types in the gonad, or to switch between testis and ovary differentiation, is not only intriguing, but of great interest to the field of organogenesis.

Seasonal Breeders

Seasonal breeders adapt their behavior over the course of breeding and nonbreeding seasons. During the breeding season, aggressive behavior associated with territorial defense is suppressed to allow individuals of the opposite sex to come into close proximity for mating. This behavioral modulation is intimately linked to steroid hormones such as testosterone that regulate aggression and territoriality. The steroidogenic portion of the gonad, therefore, is in a dynamic state over the course of the year in order to meet the requirements of behavior in breeding (or nonbreeding) seasons. This plasticity in gonad phenotype is manifest in the size, activity, or differentiated state of the hormone-secreting cell populations, and demonstrates that even adult gonads can be subject to dramatic alterations in sex-specific morphology. In this section, we discuss specific examples of species in which seasonal expansion or regression of the testis and ovary occur.

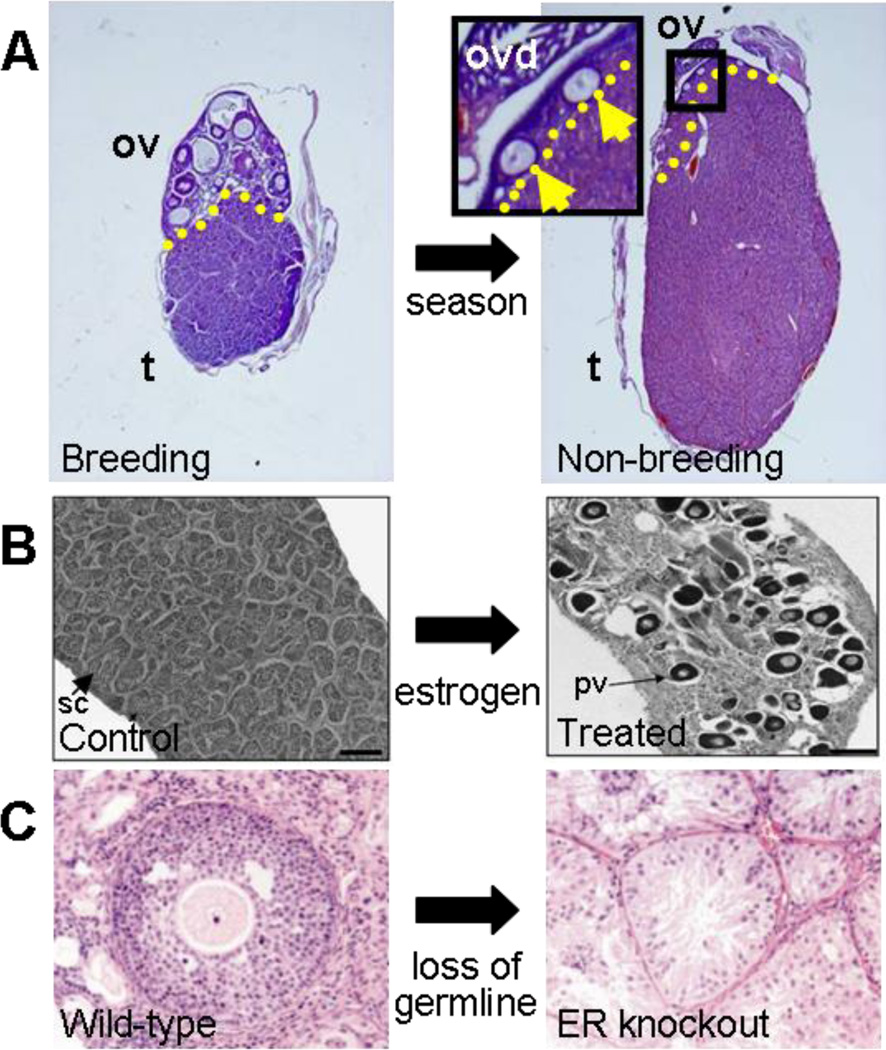

The European mole is an excellent example of the plasticity of gonad phenotype between testis and ovary. Although moles may appear morphologically and phylogenetically closely related to the mouse, the structure of the gonad is unique. The Talpa genus displays functional hermaphroditism. Female moles of this genus have bilateral ovotestes (Jimenez et al. 1993), which contain two distinct regions: an outer cortex in which germ cells and follicles reside and an interior agametic testis-like portion that occupies most of the gonad volume and is filled with Leydig cells and germ-cell-less testis-cord-like structures. It is thought that the testicular portion of the ovotestis is required for increased testosterone production during the nesting (nonbreeding) season, when female aggression protects offspring and territory. In fact, serum levels of testosterone in females during the nonbreeding season are similar to males and are lower during the breeding season (Jimenez et al. 1993, Whitworth et al. 1999). Consistent with this change in hormone level, the proportion of the gonad allocated to testicular or ovarian tissue changes over the course of the year (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Evidence for plasticity of adult gonad phenotypes. (a) Ovotestes of the female European mole (Talpa occidentalis). In the breeding-season ovotestis (left), about 50% of the gonad is dedicated to ovarian and 50% to testicular tissue. A distinct border is evident (yellow dashed line) between the ovarian portion (ov) with developing follicles and the testicular portion (t) with Leydig cells and testis cords. The nonbreeding-season ovotestis (right) shows a dramatic increase in the size of the testicular portion and a decrease in the ovarian portion, which contains only a few immature follicles (inset, arrows). Images courtesy of Dr. Rafael Jimenez, Department of Genetics, University of Granada, Spain. (b) An adult coral goby (Gobiodon erythrospilus) male control gonad (left) contains seminiferous cords with spermatocytes (sc). When treated with estradiol (right), the male changes sex to female, and the gonad converts to a functional ovary, with previtellogenic oocytes (pv) visible. Images from Kroon et al. 2005. Reprinted with permission of The Royal Society. (c) Wild-type mouse follicle (left) containing an oocyte surrounded by granulosa cells. In an estrogen receptor (ER) α/β knockout mutant mouse (right), folliculogenesis is disrupted and granulosa cells transdifferentiate into Sertoli-like cells that cluster to form testis-like tubules. Images from Couse et al. 1999. Reprinted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Long-distance migrating male birds display another seasonal adaptation that conserves energy for flying that would normally be used for spermatogenesis. These birds undergo massive testicular regression during migrating, nonbreeding seasons, and recrudescence during breeding seasons. Sylvia borin (African migratory garden warbler) has been studied for its fluctuation in testis size during migratory and nonmigratory seasons (Bauchinger et al. 2007, 2005). Testicular recrudescence beginning at the end of the migratory period was most obviously manifested by testis weight, diameter of seminiferous tubules, and progression of spermatogenesis. In addition to increased sperm production in breeding postmigratory animals, serum levels of testosterone were also increased (Bauchinger et al. 2007), suggesting that Leydig cells are also subject to migratory adaptation. The cellular and histological bases for seasonal gonadal adaptation have not been characterized, but studies in various species have implicated apoptosis or cellular atrophy of different cell types in the testis (Young & Nelson 2001). In any case, it is clear that there is significant plasticity of the differentiation status of somatic and germline components of the gonad in seasonal migratory species.

Recrudescence: –reappearance or regrowth after a period of absence or atrophy

Masculinized Females

The presence of a testis-like androgen-producing region in the XX gonad is not unique to seasonal breeders, but is also present in females of species such as the spotted hyena in which aggression is vital for reproductive success. Spotted hyena females are masculinized in their external reproductive apparatus (Lindeque & Skinner 1982). Hyena females possess no vulva, but do have a pseudoscrotum and an elongated peniform clitoris through which dangerous and prolonged births occur. The extent of hypermasculinization is also evident in that they are larger and more aggressive than their male counterparts. This aggression in females is evolutionarily advantageous, because more aggressive, highly androgen-producing females can gain social rank, obtain more food for their offspring, and raise more successful young to adulthood than meeker, lower-androgen-producing females (Dloniak et al. 2006). Like the European mole, the XX hyena gonad has a high capacity for androgen synthesis starting in late fetal stages as large clusters of medullary cells express steroidogenic enzymes such as 3β-HSD and P450c17 (Browne et al. 2006). The burst of androgen production from the gonad during fetal stages promotes virilization of external genitalia and perhaps also of the brain, leading to aggressive behavior during adulthood.

Bidirectional Sex Change

An even more extreme case of gonadal plasticity observed in the animal kingdom is bidirectional sex change. This phenomenon has been reported mostly in fish species, and is triggered by social or environmental conditions in which a sex change improves reproductive fitness or success (Kuwamura et al. 1994, Munday 2002). Bidirectional sex change in fish has been well documented in the goby family, in particular the genera Gobiodon or Paragobiodon (Nakashima et al. 1996, Sunobe & Nakazono 1993). Kroon and colleagues found that manipulating estrogen levels via the aromatase pathway in Gobiodon erythrospilus (coral goby) was sufficient to induce an adult sex change in which female gonads underwent spermatogenesis and male gonads exhibited oocyte formation (Kroon et al. 2005) (Figure 7b). In nature, behavioral control of sex differentiation in Lythrypnus dalli (bluebanded goby) and Trimma okinawae (Okinawa rubble goby) has also been documented. In both these species, one male is at the top of the social hierarchy, with multiple lower-ranking females in the harem. When the male exits the group, one female (usually the largest one) ascends to the top rank and sex reverses to a male (Kobayashi et al. 2005, Rodgers et al. 2005, Sunobe & Nakazono 1993). The cellular mechanisms of this transformation are not yet clear, but it is likely that apoptosis is involved and that there are some stem-like cells (both somatic and germline-derived) that can be co-opted to change fate and differentiate depending on the context of the gonad at that particular time. In fact, both L. dalli and T. okinawae possess remnants of both sexes in their gonads at all times, regardless of the functional sex at any given point (Kobayashi et al. 2005, Rodgers et al. 2005). Revealing the factors involved in maintaining such extreme plasticity would have far-reaching impacts on stem cell biology and organogenesis.

Bidirectional sex change: –switching between sexes more than once during an adult lifetime, but existing as only one sex at a time

Mammals

Many experiments indicate that the mammalian ovary can undergo a transformation to a testis-like structure in certain conditions, for example, when transferred beneath the male kidney capsule (Taketo-Hosotani et al. 1985; Taketo et al. 1984, 1993). Although the cellular mechanism for this dramatic transformation has not been thoroughly characterized, the loss of germ cells in rats also results in transdifferentiation of granulosa cells into Sertoli-like cells (Guigon et al. 2005, Mazaud Guittot et al. 2006). Similarly, in certain genetic mouse mutants, in which germ cells are lost by postnatal stages, such as Wnt4, aromatase, Foxl2, or estrogen receptor (ER)-α and ER-β ovaries, male-specific genes such as Sox9 and Amh are expressed ectopically in granulosa cells (Britt et al. 2002, Couse et al. 1999, Dupont et al. 2000, Ottolenghi et al. 2005, Vainio et al. 1999). These groups of transformed cells exhibit Sertoli-like cytology and can even form tubule-like structures in the ovary that appear very similar to testis cords (Britt et al. 2002, Couse et al. 1999) (Figure 7c). The stage at which germ cells or oocytes are lost may have a direct impact on the severity of the sex-reversal phenotype (Guigon & Magre 2006).

These remarkable changes in phenotype demonstrate that there is still plasticity in the somatic compartment of the vertebrate gonad, even in adult stages. There is a range in the capacity of gonadal cells to dedifferentiate and alter their phenotype in different species, although it is clear that the gonads in all the species we have discussed are potentially dynamic and labile in their phenotype. Sex reversals, either full or partial, may be an evolutionary remnant of a time in which a changing environment dictated a need for changing sex to improve chances for reproductive success.

CONCLUSION

Sex-determining mechanisms vary widely among vertebrates, ranging from a single, dominant male-determining gene to systems that are sensitive to temperature or other environmental influences. A unifying hypothesis is that this diversity overlays a fundamental antagonistic signaling system, as has been described in mammals (Kim & Capel 2006). A bistable system, characterized by multiple feedback loops, could be influenced by a primary imbalance generated by an input at one of many different points in the network. This could explain the wide variability in the primary switch that controls sex determination among vertebrates. Once an imbalance is initiated, it could be amplified and propagated by reinforcing signaling loops that canalize development along the ovary or testis pathway. Evidence that germ cells, supporting cells, and steroidogenic cells strongly influence each other’s differentiation suggests that any one of these cell types may play the lead role in initiating development of the testis or ovary (Barske & Capel 2008). This circular pattern of reinforcement might account for the variability in the order of cell differentiation and morphological changes seen among species. These hypotheses have not been investigated, and thus remain in the realm of theoretical possibilities.

The goal of sex determination in all vertebrates is the same: to produce functional, sexually dimorphic reproductive organs from a common primordium. It is striking that, despite the vast array of sex determination mechanisms, vertebrate adult testes and ovaries are astoundingly similar in structure. Yet the morphogenesis of these organs seems to be mechanistically different. In particular, testis cords can assemble de novo (as in mice), from invaginations of the surface epithelium (as in turtle), or from primitive cord-like structures in the medulla (as in chick). Whether there is a similar underlying mechanistic basis for testis cord formation is not yet clear. However, Sox9 expression seems to be a common thread, associated with the stabilization of cord structure in all species. As more genomes are sequenced, the variation in the order and types of morphogenetic events may present an opportunity to link molecular programs with specific morphogenetic processes. This will be an important direction for future research.

Although germ cells are dispensable for testis development, they are essential for the development and stabilization of adult ovarian architecture and steroidogenesis. The germline appears to play a lead role in differentiation of gonads in medaka and zebrafish, whereas its role seems to be secondary in mammals and needs further study in other species. Germ cell sexual dimorphism precedes any identified somatic cell dimorphisms in fish gonads. It will be important to understand whether sexual dimorphism of germ cell development is initiated by local or systemic signals in fish.

No other organ displays the plasticity of the gonad in response to seasonal and environmental cues, or the extreme regeneration capability seen in sex-reversing fishes in which the gonad can degenerate and reform as a gonad of the opposite sex. These features of gonad development may reflect the strong evolutionary drive toward adaptations that lead to reproductive success. They certainly provide an exciting vista onto fundamental developmental questions about organogenesis, cell fate determination, morphogenesis, evolutionary mechanisms, cellular interactions, regeneration, and stem cell biology.

Table 1. The requirement for germ cells in gonad sexual differentiation.

The role of germ cells was examined in the literature for four animal models in both fetal/embryonic and postnatal/adult stage testes and ovaries. Yes denotes that germ cells are required for gonad differentiation. No indicates that wild-type gonad morphology is observed in the absence of germ cells. n.d., not determined.

| Fetal/embryonic stages | Postnatal/adult stages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Testis | Ovary | Testis | Ovary |

| Mouse/rat | No---testis cord formation and normal Sertoli differentiation (Merchant 1975, Mintz & Russell 1957) | No---female ovigerous cords normal (Merchant 1975, Merchant-Larios & Centeno 1981) | No---seminiferous tubule formation and normal Sertoli cells (Coulombre & Russell 1954, Handel & Eppig 1979) | Yes---follicle degeneration and Sertoli-like cords (Britt et al. 2002, Couse et al. 1999, Merchant-Larios & Centeno 1981, Vainio et al. 1999) |

| Chick | No---normal testis cords, reproductive ducts, and hormones (McCarrey & Abbott 1978, 1982) | No---normal cortical expansion, reproductive ducts, and hormones (McCarrey & Abbott 1978, 1982) | No---seminiferous tubule formation; Leydig cells present (Trefil et al. 2006; Trefil et al. 2003) | Yes---masculinized external plumage and comb; abnormal ovary with testis-like cords (Callebaut 1969) |

| Turtle | No---normal testis cord formation (DiNapoli & Capel 2007) | No---normal cortex medulla and lacunae (DiNapoli & Capel 2007) | n.d. | n.d. |

| Fish | No---male-specific genes expressed (Kurokawa et al. 2007, Siegfried & Nusslein-Volhard 2008, Slanchev et al. 2005) | Yes---female-specific genes downregulated; no follicles (Kurokawa et al. 2007, Siegfried & Nusslein-Volhard 2008, Slanchev et al. 2005) | No---testis tubule formation; adult male pigmentation and mating behaviors (Kurokawa et al. 2007, Siegfried & Nusslein-Volhard 2008, Slanchev et al. 2005) | Yes---no follicles; tubules form; male-specific genes expressed (Kurokawa et al. 2007, Siegfried & Nusslein-Volhard 2008, Slanchev et al. 2005) |

SUMMARY POINTS.

Adult testis and ovary structures are similar across species, regardless of the sex-determining mechanism.

Although adult gonads appear similar in different species, the cellular and molecular mechanisms that are responsible for their morphogenesis are often not conserved.

In mice, gonadal cord-like structures are male-specific; cord formation in other species occurs by a sex-independent mechanism.

The pathway of germ cell entry into the gonadal mesoderm is distinct in different species: In the mouse, PGCs travel through gut mesentery and mesonephros, whereas PGCs in the chick enter the gonad through the vasculature.

Meiotic germ cells are required in most species (and perhaps in all species) to stabilize the ovarian fate.

Hormones in egg-laying vertebrates are sufficient to induce sex reversal during embryogenesis (and sometimes in adult stages in fish), but do not have this effect in eutherian mammals.

There is a significant amount of plasticity in the adult testis and ovary that can be influenced by hormones, loss of germline, or social conditions.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Investigation of how somatic--germ cell interactions in the ovary play a role in maintaining ovarian structure and function.

A detailed comparative analysis of the molecular signals during sex determination to establish correlations with morphological changes during testis and ovary differentiation.

How estrogen and other hormones can induce sex reversal in different species, and how the evolution of the placenta in eutherian mammals has affected the role of hormones in gonad morphogenesis.

How sex-reversing animals, such as goby and other fish, can maintain plasticity and regenerative capacity of their germline and/or gonadal soma and how this might be a key to understanding how stability in gonad phenotype is maintained in mammals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. D. Swartz, T. Caceci, and R. Jimenez for images. We also thank L. Barske, D. Maatouk, and S. Munger for helpful comments. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL63054 and HD39963) and the National Science Foundation (NSF-0849646) to B.C.

KEY TERMS

- Bidirectional sex change

switching between sexes more than once during an adult lifetime, but existing as only one sex at a time

- Bipotential

undifferentiated state of the gonadal primordium that can develop into testis or ovary

- Environmental sex determination (ESD)

when extrinsic factors (e.g., temperature) direct sexual phenotype

- Female-producing temperature (FPT)

when temperature-dependent sex determination produces 100% female offspring

- Follicle

the basic unit of the ovary, which contains the oocyte surrounded by somatic cells

- Genetic sex determination (GSD)

when chromosomal elements direct sexual phenotype regardless of environment

- Gonochoristic

a species that can only exhibit one sexual phenotype or produce one type of gamete at a time

- Granulosa cell

somatic support cell of the ovary that forms part of the follicle

- Hermaphroditic

a species that can simultaneously exhibit male and female phenotypes or produce eggs and sperm at the same time

- Lacuna

a small hole or cavity in an anatomical structure

- Male-producing temperature (MPT)

when temperature-dependent sex determination produces 100% male offspring

- Primary sex determination

development of sexual phenotype in the somatic cells of the gonad

- Primordial germ cell (PGC)

the progenitor of sperm or eggs that has not yet sexually differentiated or entered meiosis

- Protogyny

sex change in the direction from female to male (as opposed to protandry)

- Recrudescence

reappearance or regrowth after a period of absence or atrophy

- Sertoli cell

somatic support cell of the testis that will be in close association with germ cells and support spermatogenesis throughout life

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any biases that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Contributor Information

Tony DeFalco, Email: t.defalco@cellbio.duke.edu.

Blanche Capel, Email: b.capel@cellbio.duke.edu.

LITERATURE CITED

- Albrecht KH, Eicher EM. Evidence that Sry is expressed in pre-Sertoli cells and Sertoli and granulosa cells have a common precursor. Dev. Biol. 2001;240:92–107. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barske LA, Capel B. Blurring the edges in vertebrate sex determination. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2008;18:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauchinger U, Van’t Hof T, Biebach H. Testicular development during long-distance spring migration. Horm. Behav. 2007;51:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauchinger U, Wohlmann A, Biebach H. Flexible remodeling of organ size during spring migration of the garden warbler (Sylvia borin) Zoology (Jena) 2005;108:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, Knight D, Smith C, Wilhelm D, Richman J, et al. Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science. 2006;312:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1125691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braat AK, Zandbergen T, van de Water S, Goos HJ, Zivkovic D. Characterization of zebrafish primordial germ cells: morphology and early distribution of vasa RNA. Dev. Dyn. 1999;216:153–167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199910)216:2<153::AID-DVDY6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J, Karl J, Capel B. Divergent vascular mechanisms downstream of Sry establish the arterial system in the XY gonad. Dev. Biol. 2002;244:418–428. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt KL, Kerr J, O’Donnell L, Jones ME, Drummond AE, et al. Estrogen regulates development of the somatic cell phenotype in the eutherian ovary. FASEB J. 2002;16:1389–1397. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0992com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne P, Place NJ, Vidal JD, Moore IT, Cunha GR, et al. Endocrine differentiation of fetal ovaries and testes of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta): timing of androgen-independent versus androgen-driven genital development. Reproduction. 2006;132:649–659. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehr M, Gu S, McLaren A. Mesonephric contribution to testis differentiation in the fetal mouse. Development. 1993;117:273–281. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.273. Demonstrated that mesonephric cell migration in the mouse is critical for testis cord formation.

- Bull JJ, Vogt RC. Temperature-sensitive periods of sex determination in Emydid turtles. J. Exp. Zool. 1981;218:435–440. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402180315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut M. Sterilization of the left ovary of the chicken and quail by the action of thymidine-3H during ovogenesis. Experientia. 1968;24:944–945. doi: 10.1007/BF02138672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut M. Partial masculinization of genetic female chickens (Gallus gallus) after incorporation of 3H-thymidine during the period of oogenesis. Experientia. 1969;25:435–436. doi: 10.1007/BF01899971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaboissier MC, Kobayashi A, Vidal VI, Lutzkendorf S, van de Kant HJ, et al. Functional analysis of Sox8 and Sox9 during sex determination in the mouse. Development. 2004;131:1891–1901. doi: 10.1242/dev.01087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton M, Haines LC. An overview of factors influencing sex determination and gonadal development in birds. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 1999;55:876–886. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7781-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes AN, Wilhelm D, Davidson T, Dejana E, Harley V, et al. Endothelial cell migration directs testis cord formation. Dev. Biol. 2009;326:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cool J, Carmona FD, Szucsik JC, Capel B. Peritubular myoid cells are not the migrating population required for testis cord formation in the XY gonad. Sex Dev. 2008;2:128–133. doi: 10.1159/000143430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombre JL, Russell ES. Analysis of the pleiotropism at the W-locus in the mouse: the effects of W and Wv substitution upon postnatal development of germ cells. J. Exp. Zool. 1954;126:277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Hewitt SC, Bunch DO, Sar M, Walker VR, et al. Postnatal sex reversal of the ovaries in mice lacking estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Science. 1999;286:2328–2331. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2328. Showed that knockout of mouse estrogen receptors caused transition of adult ovary to a testis-like phenotype.

- Coveney D, Cool J, Oliver T, Capel B. Four-dimensional analysis of vascularization during primary development of an organ, the gonad. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7212–7217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707674105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coveney D, Shaw G, Renfree MB. Estrogen-induced gonadal sex reversal in the tammar wallaby. Biol. Reprod. 2001;65:613–621. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.2.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNapoli L, Capel B. Germ cell depletion does not alter the morphogenesis of the fetal testis or ovary in the red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta) J. Exp. Zoolog. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2007;308:236–241. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dloniak SM, French JA, Holekamp KE. Rank-related maternal effects of androgens on behaviour in wild spotted hyaenas. Nature. 2006;440:1190–1193. doi: 10.1038/nature04540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Krust A, Gansmuller A, Dierich A, Chambon P, Mark M. Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development. 2000;127:4277–4291. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durcova-Hills G, Capel B. Chapter 6: development of germ cells in the mouse. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2008;83:185–212. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconi R, Dalpiaz D, Zaccanti F. Morphological aspects of gonadal morphogenesis in Bufo bufo (Amphibia anura): Bidder’s organ differentiation. Anat. Rec. 2007;290:801–813. doi: 10.1002/ar.20521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske M, Maack G, Schafers C, Segner H. An environmentally relevant concentration of estrogen induces arrest of male gonad development in zebrafish, Danio rerio. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005;24:1088–1098. doi: 10.1897/04-096r1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske M, Segner H. Aromatase modulation alters gonadal differentiation in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio) Aquat. Toxicol. 2004;67:105–126. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet JP, Dang DC. A comparative study of the development of the fetal testis and ovary in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 1980;20:1439–1459. doi: 10.1051/rnd:19800804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla S, Cordeschi G, Properzi G, Concordia N, Cappa F, Pozzi V. Ultrastructure of fetal human gonad before sexual differentiation and during early testicular and ovarian development. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. Pathol. 1990;22:389–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto T, Ukeshima A, Kiyofuji R. The origin, migration and morphology of the primordial germ cells in the chick embryo. Anat. Rec. 1976;185:139–145. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091850203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grier H. Ovarian germinal epithelium and folliculogenesis in the common snook, Centropomus undecimalis (Teleostei: Centropomidae) J. Morphol. 2000;243:265–281. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(200003)243:3<265::AID-JMOR4>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubbay J, Collignon J, Koopman P, Capel B, Economou A, et al. A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature. 1990;346:245–250. doi: 10.1038/346245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guigon CJ, Coudouel N, Mazaud-Guittot S, Forest MG, Magre S. Follicular cells acquire sertoli cell characteristics after oocyte loss. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2992–3004. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guigon CJ, Magre S. Contribution of germ cells to the differentiation and maturation of the ovary: insights from models of germ cell depletion. Biol. Reprod. 2006;74:450–458. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.047134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guioli S, Lovell-Badge R. PITX2 controls asymmetric gonadal development in both sexes of the chick and can rescue the degeneration of the right ovary. Development. 2007;134:4199–4208. doi: 10.1242/dev.010249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker A, Capel B, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Expression of Sry the mouse sex determining gene. Development. 1995;121:1603–1614. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi S. A light- and electron-microscopic study on the migration of primordial germ cells in the teleost, Oryzias latipes. Cell Tissue Res. 1982;227:139–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00206337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handel MA, Eppig JJ. Sertoli cell differentiation in the testes of mice genetically deficient in germ cells. Biol. Reprod. 1979;20:1031–1038. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod20.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes T, Haston K, Tsui M, Hoang A, Haeffele C, Vonk A. Atrazine-induced hermaphroditism at 0.1 ppb in American leopard frogs (Rana pipiens): laboratory and field evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003;111:568–575. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka T, Biggs WH, 3rd, Tieu D, Boyer AD, Varki NM, et al. Disruption of forkhead transcription factor (FOXO) family members in mice reveals their functional diversification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2975–2980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400093101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houwing S, Kamminga LM, Berezikov E, Cronembold D, Girard A, et al. A role for Piwi and piRNAs in germ cell maintenance and transposon silencing in Zebrafish. Cell. 2007;129:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell S, Shalet S. Gonadal damage from chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 1998;27:927–943. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y, Komatsu T, Kasahara M, Katoh-Fukui Y, Ogawa H, et al. Mechanism of asymmetric ovarian development in chick embryos. Development. 2008;135:677–685. doi: 10.1242/dev.012856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Yokouchi K, Yoshida K, Kano K, Naito K, et al. Investigation of the fate of Sry-expressing cells using an in vivo CreloxP system. Dev. Growth Differ. 2006;48:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamatsu T, Kobayashi H, Hamaguchi S, Sagegami R, Shuo T. Estradiol-17beta content in developing eggs and induced sex reversal of the medaka (Oryzias latipes) J. Exp. Zoolog. A Comp. Exp. Biol. 2005;303:161–167. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen FJ, Phillips PC. Exploring the evolution of environmental sex determination, especially in reptiles. J. Evol. Biol. 2006;19:1775–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez R, Burgos M, Sanchez A, Sinclair AH, Alarcon FJ, et al. Fertile females of the mole Talpa occidentalis are phenotypic intersexes with ovotestes. Development. 1993;118:1303–1311. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori A, Nagahama Y, Egami N. Development of the tissue architecture in the gonads of the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Zoolog. Sci. 1985;2:695–706. [Google Scholar]

- Karl J, Capel B. Sertoli cells of the mouse testis originate from the coelomic epithelium. Dev. Biol. 1998;203:323–333. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Capel B. Balancing the bipotential gonad between alternative organ fates: a new perspective on an old problem. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235:2292–2300. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]