Abstract

Hepatitis C virus infects nearly 3% of the world population and is often referred as a silent epidemic. It is a leading cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in endemic countries. Although antiviral drugs are now available, they are not readily accessible to marginalized social groups and developing nations that are disproportionally impacted by HCV. To stop the HCV pandemic, a vaccine is needed. Recent advances in HCV research have provided new opportunities for studying HCV neutralizing antibodies and their subsequent use for rational vaccine design. It is now recognized that neutralizing antibodies to conserved antigenic sites of the virus can cross-neutralize diverse HCV genotypes and protect against infection in vivo. Structural characterization of the neutralizing epitopes has provided valuable information for design of candidate immunogens.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was identified to be the causative agent of non-A non-B hepatitis in 1989 [1]. It is estimated that HCV infects nearly 3% of the world population [2-5]. In the US, the national rate of symptomatic HCV infection declined and began to level around 2005 [6]. However, HCV had overtaken HIV as a cause of death between 1999-2007 [7]. Perhaps the most alarming trend is the increasing number of cases in the 15-24 year age group [8,9]. HCV infection is considered a silent killer because it can be transmitted to new hosts unnoticed and can take up to 20-40 years before severe clinical symptoms develop. Potent direct acting antivirals (DAAs) against different viral targets have recently been developed [10-13]. However, access to therapy has historically been low, partly due to poor HCV awareness, diagnosis and high drug cost [14-16]. To solve the global HCV problem, more effective and affordable drugs against HCV, as well as an effective vaccine, are needed.

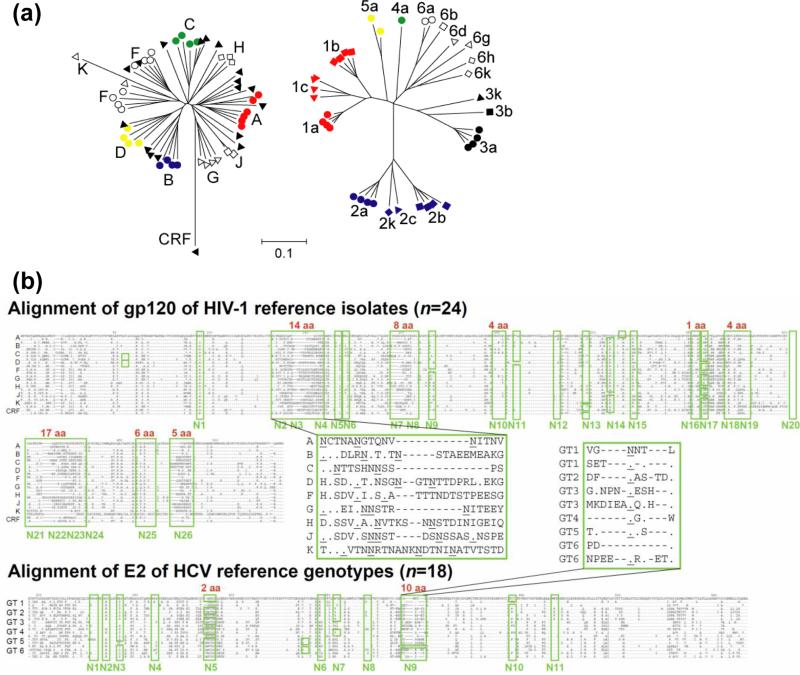

The extreme genetic diversity of circulating HCV is a major roadblock to an HCV vaccine [17] (Figure 1). To overcome this challenge, a broadly effective vaccine must target conserved B and T cell epitopes. Ongoing research on a T cell-based vaccine showed that prime-boost immunization with heterologous viral vectors presenting non-structural antigens of HCV could elicit high levels of functional T cells in healthy volunteers. The prophylactic efficacy of this vaccine candidate is currently under evaluation in a Staged Phase I/II Clinical Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01436357) [18,19]. A subunit vaccine candidate based on the viral envelope glycoprotein complex E1E2 had been investigated in a Phase I Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT00500747) [20-23]. The majority of the subjects did not produce neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) despite the antigens appearing to perform reasonably well in mouse, guinea pig and chimpanzee models [24,25].

Figure 1. Comparison of antigenic variability of HIV-1 and HCV Env.

(a) Phylogeny relationships of envelope glycoprotein amino-acid sequences of HIV (left) and HCV (right) reference viruses inferred by the neighbor-joining method (MEGA4 software). Genotype/subtype reference virus sequences were downloaded from the LANL HIV and HCV sequence database. Scale bar indicates the fraction of amino-acid substitutions. HCV genotypes are generally more diverse than HIV-1 clades. (b) The glycan shield of HIV-1 is more variable than HCV. The number of N-linked glycosylation sites on HIV-1 gp120 ranges from 18-33 (average 25), and from 10-11 sites on HCV E2. Approximately one site is present for every 21 and 33 residues of gp120 and E2, respectively. The relative positions of N-linked glycosylation sites (boxed in green and numbered underneath) and the levels of amino acid insertions within the glycosylation regions (red numbers above green boxes) are marked on the reference HIV-1 gp120 or HCV E2 sequence alignments. Selected sequences are shown in insets to highlight the level of variations around N2-4 of gp120 and N9 of E2. Residues identical to the top sequences and insertions are indicated by ‘.’ and ‘-‘, respectively. Asparagines in the putative glycosylation sites are underlined. Consequently, HIV-1 can change its glycosylation pattern in many more ways than HCV to escape antibody neutralization.

Studying HCV neutralizing antibody responses

Previously, HCV nAbs were difficult to study because of the lack of a laboratory assay to measure antibody neutralization of virus and a small animal model for studying viral infection. Since nAbs to HCV target the viral envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2, anti-viral antibody activity was determined by a “neutralizing of binding (NOB)” assay to measure the ability of an antibody sample to inhibit E2 binding to human cell lines bearing the viral receptor CD81 [26]. This assay was later found not to fully represent the biological activity of nAbs. It is noted that some antibodies can block E2 binding to CD81 but do not neutralize (e.g. mAb AR1A) [27]. The observation implies the presence of antigenic sites accessible on isolated E1E2 but not on the virus. In the last 10-15 years, the development of the HCV pseudotyped virus (HCVpp) [28-30] and cell culture virus (HCVcc) [31-34] systems, and humanized mouse models susceptible to HCV infection [35-40], have greatly enhanced the study of anti-HCV antibodies. Early works of Purcell et al. [41-43] and Houghton et al. [25,44] established the importance of nAbs in HCV protection. Recently, however, using these viral systems, multiple research groups reported the positive correlation of early induction of nAbs and viral control/clearance in humans [45-47]. The viral systems also help explain the poor results of an early clinical trial of the nAb HCV-AbXTL68 for prevention of recurrent HCV in liver transplant patients [48,49]. The nAb was later found to be only moderately neutralizing in the HCVpp assay (~50% virus neutralization at 20 µg/ml nAb) despite showing promising results in multiple surrogate assays [50,51]. Of note, these in vitro viral systems do not fully recapitulate the envelope composition of infectious virions from infected humans. HCV is known to be associated with apolipoproteins, particularly ApoE, and this association is speculated to play a role in masking E1E2 neutralizing epitopes [52-57]. Further studies of the subtle differences between the virus particles produced in vitro and the exact composition of viral and host proteins on native HCV virions will be crucial for the field [55,58]. Nevertheless, these assays have accelerated identification of broadly nAbs (bnAbs) that cross-neutralize diverse HCV genotypes [27,59-64], protect animal models from HCV challenge in passive transfer experiments [27,65-67], and even delay viral rebound following liver transplantation in HCV patients [68].

HCV neutralizing epitopes for immunogen design

E2 antigenicity

HCV nAbs and viral escape mechanisms have been reviewed recently [69-74]. Here we aim to discuss information that is complementary to these reviews and to introduce concepts that are relevant to rational vaccine design. A collection of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to E1 and E2 used by many labs in the field have also been summarized elsewhere [74-76]. Regarding the antigenicity of the HCV enveloped glycoproteins, Keck et al. first proposed three immunogenic domains in E2 similar to the antigenic structural and functional domains of other flavivirus envelope E glycoproteins [77-80]. E2 was designated as having Domains A, B and C based on binding of non-competing mAbs isolated from humans, and these domains were later expanded to include antigenic Domains D and E [63,64,81]. Examples of mAbs to the different Domains are CBH4B, CBH5, CBH7, HC84-1 and HC33.1, respectively. The epitopes of some of the mAbs have been mapped by site-directed mutagenesis, selection of escape mutants, mass spectrometry, and protein crystallography [70,81-86]. However, the recently determined structures of E2 from two different HCV genotypes do not support the analogy between hepacivirus E2 and flavivirus E proteins [87,88].

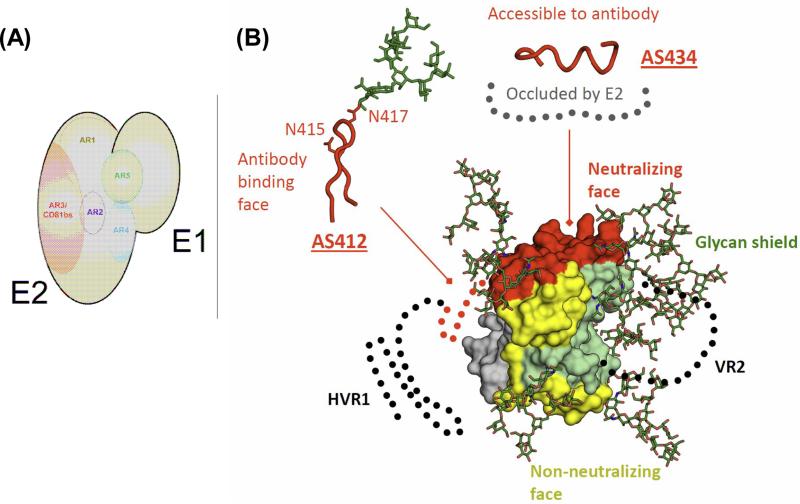

Our lab has isolated a panel of human mAbs to discontinuous epitopes on E1E2 by phage-display [27,65]. Based on cross-competition between the mAbs binding to E1E2, the epitopes recognized by the mAbs were grouped into 5 clusters, or antigenic regions (ARs) (Figure 2A). Antigenic regions 1, 2 and 3 (AR1-3) are present on E2, and AR4 and AR5 on the E1E2 complex. AR1 is proximal to the CD81 binding site on E2 (E2 CD81bs). However, AR1 is not conserved and is probably not exposed on the viral surface. The mAbs to AR1 only bind genotype 1 HCV and do not have significant neutralizing activity. Interestingly, mAb AR1A competes strongly with mAb AR1B in E2 binding, but only mAb AR1A blocks E2-CD81 interactions [27]. AR2 is distal from the E2 CD81bs and is exposed on E2 because mAb AR2A can neutralize several HCV isolates. AR3 is conserved and overlaps with E2 CD81bs. Multiple mAbs to AR3 can cross-neutralize diverse HCV genotypes. AR4 and AR5 are present only on the E1E2 complex and are adjacent to each other. Mapping data suggest that they may be binding near the stalk region of E2 and interacting with the N-terminal region of E1 [65]. In passive transfer experiments using humanized mouse models, mAbs to AR3 and AR4 offered significant levels of protection against challenge by multiple HCV genotypes [27,65,67].

FIGURE 2. Antigenicity of HCV Env.

(A) Antigenic regions of E1E2 complex. The viral envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 form non-covalent heterodimers. A panel of human mAbs isolated from an HCV-immune antibody library by phage display defines 5 distinct antigen regions (ARs) on the E1E2 complex [27,65]. AR1, AR2 and AR3 are present on E2, and AR4 and AR5 on the E1E2 complex. AR3 overlaps with CD81bs on E2. Several mAbs to AR3 and AR4 cross-neutralize diverse HCV genotypes and protect against HCV infection in small animal models. (B) Antigenic surface of E2c. The molecular surface of the E2c structure is colored according to known properties: green, glycan face; grey, occluded face; yellow, non-neutralizing face; and red, neutralizing face. The conserved, accessible neutralizing face contains the E2 CD81bs, AS412 and AS434, and is the prime target for structure-based immunogen design [86,87,94-97,101].

This antibody panel guided us to systematically truncate the N and C termini, substitute the flexible variable region 2 with a short linker, and remove N448 and N576 glycosylation sites, of the wildtype E2 of the prototypic genotype 1a H77 to generate the E2 core domain (E2c) [87]. E2c in complex with bnAb AR3C was able to produce diffraction-quality protein crystals for determination of the first E2 structure. The structure reveals a novel protein fold of E2c consisting of a central β-sandwich flanked by an N-terminal front layer and a C-terminal back layer. The front layer consists of mostly strands and a short helix that packs against both the central beta-sandwich and the back layer. The back layer contains antiparallel β-sheets and short helices. Importantly, the structure and the antibody panel roughly define four faces of E2c: glycan, occluded, non-neutralizing and neutralizing (Figure 2B). The accessible neutralizing face overlaps with E2 CD81bs and identifies a relatively large and conserved antigenic surface for immunogen design. The novel fold of E2 was later confirmed by the Marcotrigiano lab using an E2 derived from genotype 2a HCV with different truncations [88].

In addition to the above attempts to describe the antigenicity of HCV envelope glycoproteins, Zhang et al. proposed the presence of two “epitopes” at E2 residues 412-419 (“epitope I”) and 434-446 (“epitope II”) that played important roles in regulating antibody neutralization of HCV [89,90]. Strictly speaking, these two E2 regions could be more accurately described as “antigenic sites” instead of “epitopes” since no mAb was generated in their studies to define the epitopes. Using peptides corresponding to these two antigenic sites, the Zhang group isolated or depleted antibody fractions specific to the two antigenic sites from human and chimp antisera. They observed that antibodies to E2 antigenic site 412-419 (named AS412 here) could neutralize HCV but the neutralizing effect was negated by antibodies to E2 antigenic site 434-446 (named AS434 here) [89,90]. The authors suggested the presence of “interfering antibodies” to HCV nAbs and, therefore, for vaccine design, that it was important to avoid eliciting antibodies to AS434. Using mAbs to different E2 antigenic sites, Sautto et al. observed mild “interference” of mAb AP33 (to AS412) by mAb e509 (to AS434) [91]. However, the significant levels of “interference” reported by Zhang et al. have not been reproduced to date by two other leading labs in HCV antibody research [63,64,92].

AS412

Notably, these two E2 antigenic sites (AS412 and AS434) are now considered prime targets for vaccine design [62,63,87,93-97] (Figure 2B). AS412 is highly conserved, contains residues critical for CD81 receptor binding, and is occasionally targeted by antibodies isolated from human and animal sera [21,62,93,98,99]. Crystal structures of the AS412 peptide bound to bnAbs HCV1, AP33, hu5B3.v3 and MRCT10.v362 all indicate that epitope I folds as a short β-hairpin loop [94-97]. These antibodies recognize the same, hydrophobic face of the hairpin, burying its bulky residues in the antibody heavy and light chain combining sites. Some variation in the angle of approach by the antibodies to the peptide is observed, indicating this epitope is well exposed. Surprisingly, a glycosylation site at Asn417 is situated on the opposite face of the peptide that is recognized by the antibodies, suggesting that this hairpin loop is not packed against the protein but extends into solvent with some level of flexibility. This may explain why AS412 is disordered in the crystal structure of E2 bound to AR3C. Escape mutations to bnAbs targeting AS412 have been noted by different laboratories [66,68,97,100]. One interesting feature in AS412 is the presence of an unusual sequon of a N-linked glycosylation signal (underscored) at Asn417 (-Asn415-Thr416-Asn417-Gly418-Ser419-) [97]. A point mutation to Ser417 or Thr417 can shift the N-linked glycan to Asn415 (-Asn415-Thr416-Ser/Thr417-Gly418- Ser419-). Asn415 is situated in the antibody bound face and the shift of this N-linked glycan effectively masks the epitope from recognition by the above AS412-specific bnAbs. Interestingly, recent structural studies of the rat mAb 3/11 and human mAb HC33.1 to AS412 revealed two different, extended conformations [101,102]. Rat mAb 3/11 was previously reported to be moderately neutralizing [103]. In the new study, it was found to be as potent as mAb AP33 although it is still susceptible to the glycan-shift escape mutation [101]. In contrast, the human mAb HC33.1 disrupts the β-hairpin loop using a long heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 (HCDR3) and that the side chain of Asn415 is solvent exposed [102]. As a result, bnAb HC33.1 can tolerate the Asn417 to Asn415 glycan-shift mutation. Nevertheless, escape mutations within and outside AS412 in response to bnAb HC33.1 selection have also been identified [81]. Therefore, though AS412 is a promising target because of its well-defined conformations, it will be necessary to target multiple epitopes to minimize virus escape in vaccine design. Further study is also needed to assess the flexibility of AS412 and whether immunogen design should consider the different conformations.

AS434

AS434 consists of a short helix that is packed against the back layer of E2c [86,87] (see below). Crystal structures have revealed that bnAbs AR3C, HC84-1 and HC84-27 recognize a common face of the helix. Although HC84-1 and HC84-27 were crystallized with short peptides whereas AR3C was crystallized with the E2 protein, the epitope adopts a nearly equivalent helical conformation in these structures. Differences are apparent in the strands extending out from the helix in the peptide structures compared to the E2c structure. However, the strand regions of the free peptides may not represent the native conformation since they are not constrained by the rest of the E2 protein or important points of contact with the antibodies. In vitro, it is suggested that HCV cannot easily generate escape mutants to bnAbs to AS434 [63]. Weakly neutralizing mAb #8 has also been isolated that recognizes the AS434 helix from another angle of approach that would result in severe clashes with the rest of E2c [104]. Deng et al. suggested that AS434 may shift between open and closed conformations that facilitate immune evasion, although this seems unlikely due to the tight backing between the front layer and the rest of the E2 protein. However, if conformational flexibility does play a role in dampening an effective antibody response, then protein-engineering efforts to stabilize this region may be critical for vaccine development.

E1 antigenicity

E1 is known to be less immunogenic than E2 during infection [105,106] and few mAbs have been reported to E1 [61,75,76,107,108]. Neutralizing activities had been identified for mAbs H-111 recognizing E1 N-terminal antigenic site 192-202 (AS192) [108], and IGH506 and IGH526 recognizing E1 antigenic site 313-327 (AS313) [61]. It has been extremely difficult to study E1 because of the inability to produce stable, folded recombinant E1. Previous studies showed that the folding of E1 and E2 is inter-dependent [109-111] and the non-covalent heterodimer is stabilized by their transmembrane domains [112-114] and ectodomains [65]. Folded E1 can only be produced as an E1E2 complex [114,115]. In contrast, soluble E2 monomers have been produced independent of E1 by us and others [114-121]. Such biochemical properties suggest to us that E2 may serve as a chaperone protein for E1 folding and probably also as an accessory protein for E1 functions. We speculate that, in viral entry, E2 serves as the receptor binding protein while E1 may serve as the fusion protein to facilitate membrane fusion. However, the biochemical data reported on E1 as a fusion protein have not been conclusive [122-131]. Recently, the Stuart group determined the crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of E1 (residues 192-270) revealing a novel fold that is incompatible with class II fusion proteins [132,133]. Surprisingly, the E1 fragments formed oligomers linked by disulfide bonds. It is unclear if unpaired cysteines may play a role in HCV entry [134,135]. In this E1 structure, AS192 targeted by mAb H-111 forms part of a β-hairpin involving in the dimerization of the E1 fragments [133].

Conclusion

A major advance in drug discovery in recent decades has been the application of X-ray crystallography to elucidate the structures of target proteins to guide the design of small molecules that bind tightly with high specificity. Presently, there is much effort to translate this approach to vaccine design, particularly against highly variable viral pathogens such as HIV and influenza that have their surface antigens cloaked by N-linked glycans and variable loops. This effort has been driven by the isolation of exceptionally potent bnAbs that interact with “sites of vulnerability” that are conserved across viral strains, are not immunodominant in the context of the wild-type, full-length antigen. The recent discovery of HCV bnAbs and their corresponding epitope structures can be used to guide protein engineering to optimize the presentation of the epitopes within their correct conformational contexts as vaccine immunogens. Since bnAbs to HCV can be elicited in mice, HCV appears to be an excellent model to evaluate a structure-based vaccine approach and other new concepts in B cell epitope vaccine design [136-140].

Highlights.

In vitro: HCV pseudotyped virus (HCVpp) and cell culture HCV (HCVcc) were developed in 2003 and 2005 for the study of neutralizing antibodies to HCV.

In vivo: The chimpanzee model supports HCV replication but is largely unavailable for research. Several humanized mouse models are being developed as a possible replacement.

Several structures of linear peptides spanning neutralizing epitopes have been determined.

An accessible and conserved face for antibody neutralization was identified from the crystal structure of the core domain of the E2 envelope glycoprotein.

Acknowledgement

Support for this work was provided by NIH grants R01 AI079031 and R01 AI106005 and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology at The Scripps Research Institute. This is TSRI manuscript number 29050.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244 doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–567. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavanchy D. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, Brown A, Cooke GS, Pybus OG, Barnes E. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61:77–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.27259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thursz M, Fontanet A. HCV transmission in industrialized countries and resource-constrained areas. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:28–35. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis - United States, 2005. MMWR. 200756:SS–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012156:271–278. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leuchner L, Lindstrom H, Burstein GR, Mulhern KE, Rocchio EM, Johnson G, Schaffzin J, Smith P. Use of enhanced surveillance for hepatitis C virus infection to detect a cluster among young injection-drug users - New York, November 2004-April 2007. MMWR. 200857:517–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC Hepatitis C virus infection among young adolescents and young adults - Massachusetts, 2002-2009. MMWR. 201160:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Jacobson IM. Antiviral therapy with nucleotide polymerase inhibitors for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61:S91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feeney ER, Chung RT. Antiviral treatment of hepatitis C. Br Med J. 2014;348:g3308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gane EJ, Agarwal K. Directly acting antivirals (DAAs) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in liver transplant patients: “a flood of opportunity”. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:994–1002. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawlotsky JM. New hepatitis C therapies: the toolbox, strategies, and challenges. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1176–1192. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volk ML, Tocco R, Saini S, Lok AS. Public health impact of antiviral therapy for hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;50:1750–1755. doi: 10.1002/hep.23220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanwal F, Hoang T, Spiegel BM, Eisen S, Dominitz JA, Gifford A, Goetz M, Asch SM. Predictors of treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection - role of patient versus nonpatient factors. Hepatology. 2007;46:1741–1749. doi: 10.1002/hep.21927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemoine M, Thursz M. Hepatitis C, a global issue: access to care and new therapeutic and preventive approaches in resource-constrained areas. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:89–97. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17*.Kuiken C, Simmonds P. Nomenclature and numbering of the hepatitis C virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;510:33–53. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-394-3_4. [This paper reviewed the numbering system of the nucleotides and amino-acid residues of the HCV genome using the prototypic genotype 1a strain H77.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes E, Folgori A, Capone S, Swadling L, Aston S, Kurioka A, Meyer J, Huddart R, Smith K, Townsend R, et al. Novel adenovirus-based vaccines induce broad and sustained T cell responses to HCV in man. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:115ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.Swadling L, Capone S, Antrobus RD, Brown A, Richardson R, Newell EW, Halliday J, Kelly C, Bowen D, Fergusson J, et al. A human vaccine strategy based on chimpanzee adenoviral and MVA vectors that primes, boosts, and sustains functional HCV-specific T cell memory. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:261ra153. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009185. [This manuscript reported the most potent antiviral T cell responses to HCV elicted in human volunteers by adenoviral vector-primed and poxviral vector-boost vaccination.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frey SE, Houghton M, Coates S, Abrignani S, Chien D, Rosa D, Pileri P, Ray R, Di Bisceglie AM, Rinella P, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of HCV E1E2 vaccine adjuvanted with MF59 administered to healthy adults. Vaccine. 2010;28:6367–6373. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray R, Meyer K, Banerjee A, Basu A, Coates S, Abrignani S, Houghton M, Frey SE, Belshe RB. Characterization of antibodies induced by vaccination with hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:862–866. doi: 10.1086/655902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer K, Banerjee A, Frey SE, Belshe RB, Ray R. A weak neutralizing antibody response to hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein enhances virus infection. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law JL, Chen C, Wong J, Hockman D, Santer DM, Frey SE, Belshe RB, Wakita T, Bukh J, Jones CT, et al. A hepatitis C virus (HCV) vaccine comprising envelope glycoproteins gpE1/gpE2 derived from a single isolate elicits broad cross-genotype neutralizing antibodies in humans. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamataki Z, Coates S, Evans MJ, Wininger M, Crawford K, Dong C, Fong YL, Chien D, Abrignani S, Balfe P, et al. Hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein immunization of rodents elicits cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine. 2007;25:7773–7784. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reali E, Houghton M, Abrignani S. In: Hepatitis C virus vaccines. In Vaccines. edn Fifth Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit O, editors. 1187-1199. Saunders Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosa D, Campagnoli S, Moretto C, Guenzi E, Cousens L, Chin M, Dong C, Weiner AJ, Lau JY, Choo QL, et al. A quantitative test to estimate neutralizing antibodies to the hepatitis C virus: cytofluorimetric assessment of envelope glycoprotein 2 binding to target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1759–1763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Law M, Maruyama T, Lewis J, Giang E, Tarr AW, Stamataki Z, Gastaminza P, Chisari FV, Jones IM, Fox RI, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nat Med. 2008;14:25–27. doi: 10.1038/nm1698. [This paper provided the first evidence that bnAbs can protect against HCV quasispecies in the human liver chimeric mouse model.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagging LM, Meyer K, Westin J, Wejstal R, Norkrans G, Lindh M, Ray R. Neutralization of pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus expressing hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein 1 or 2 by serum from patients. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1165–1169. doi: 10.1086/339679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29*.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1-E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:633–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021756. [This manuscript is one of the first 2 reports of the HCVpp virus system.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Hsu M, Zhang J, Flint M, Logvinoff C, Cheng-Mayer C, Rice CM, McKeating JA. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7271–7276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832180100. [This manuscript is one of the first two reports of the HCVpp virus system.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, Wieland SF, Uprichard SL, Wakita T, Chisari FV. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [This manuscript is one of the first three reports of the HCVcc virus system.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, Hynes RO, Burton DR, McKeating JA, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [This manuscript is one of the first three reports of the HCVcc virus system.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33**.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Krausslich HG, Mizokami M, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med. 2005;11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [This manuscript is one of the first three reports of the HCVcc virus system. The molecular clone JFH-1 was originally isolated in the Wakita lab.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Yi M, Villanueva RA, Thomas DL, Wakita T, Lemon SM. Production of infectious genotype 1a hepatitis C virus (Hutchinson strain) in cultured human hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2310–2315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510727103. [This manuscript is one of the first reports of the development of a non-genotype 2a HCVcc.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Mercer DF, Schiller DE, Elliott JF, Douglas DN, Hao C, Rinfret A, Addison WR, Fischer KP, Churchill TA, Lakey JR, et al. Hepatitis C virus replication in mice with chimeric human livers. Nat Med. 2001;7:927–933. doi: 10.1038/90968. [This is the first report of using human liver chimeric mice for studying complete HCV replication.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azuma H, Paulk N, Ranade A, Dorrell C, Al-Dhalimy M, Ellis E, Strom S, Kay MA, Finegold M, Grompe M. Robust expansion of human hepatocytes in Fah(−/−)/Rag2(−/−)/Il2rg(−/−) mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:903–910. doi: 10.1038/nbt1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bissig KD, Wieland SF, Tran P, Isogawa M, Le TT, Chisari FV, Verma IM. Human liver chimeric mice provide a model for hepatitis B and C virus infection and treatment. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:924–930. doi: 10.1172/JCI40094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*.Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Robbins JB, Barry WT, Feng Q, Mu K, Jones CT, Schoggins JW, Catanese MT, Burton DR, et al. A genetically humanized mouse model for hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2011;474:208–211. doi: 10.1038/nature10168. [This is the first report of developing an immunocompetent, genetically humanized mice susceptible to HCV viral entry.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Washburn ML, Bility MT, Zhang L, Kovalev GI, Buntzman A, Frelinger JA, Barry W, Ploss A, Rice CM, Su L. A humanized mouse model to study hepatitis C virus infection, immune response, and liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1334–1344. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Donovan BM, Labitt RN, Budell WC, Friling T, Vogt A, Catanese MT, Satoh T, Kawai T, et al. Completion of the entire hepatitis C virus life cycle in genetically humanized mice. Nature. 2013;501:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature12427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41*.Farci P, Alter HJ, Wong DC, Miller RH, Govindarajan S, Engle R, Shapiro M, Purcell RH. Prevention of hepatitis C virus infection in chimpanzees after antibody-mediated in vitro neutralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7792–7796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7792. [An early study of the Purcell group demonstrating the protective role of nAbs in vivo.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farci P, Shimoda A, Wong D, Cabezon T, De Gioannis D, Strazzera A, Shimizu Y, Shapiro M, Alter HJ, Purcell RH. Prevention of hepatitis C virus infection in chimpanzees by hyperimmune serum against the hypervariable region 1 of the envelope 2 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15394–15399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Yu MY, Bartosch B, Zhang P, Guo ZP, Renzi PM, Shen LM, Granier C, Feinstone SM, Cosset FL, Purcell RH. Neutralizing antibodies to hepatitis C virus (HCV) in immune globulins derived from anti-HCV-positive plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7705–7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402458101. [An interesting study by the Purcell group that nAbs existing in the contaminated blood play a role in preventing HCV transmission before universal screening of HCV of donated blood.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Choo QL, Kuo G, Ralston R, Weiner A, Chien D, Van Nest G, Han J, Berger K, Thudium K, Kuo C, et al. Vaccination of chimpanzees against infection by the hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1294–1298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1294. [An early study of the Houghton group establishing the protective role of HCV nAbs in vivo.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavillette D, Morice Y, Germanidis G, Donot P, Soulier A, Pagkalos E, Sakellariou G, Intrator L, Bartosch B, Pawlotsky JM, et al. Human serum facilitates hepatitis C virus infection, and neutralizing responses inversely correlate with viral replication kinetics at the acute phase of hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:6023–6034. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6023-6034.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46*.Pestka JM, Zeisel MB, Blaser E, Schurmann P, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Patel AH, Meisel H, Baumert J, Viazov S, et al. Rapid induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and viral clearance in a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607026104. [One of the recent studies demonstrating a positive correlation of nAbs measured by the recent viral system and HCV protection in humans.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osburn WO, Snider AE, Wells BL, Latanich R, Bailey JR, Thomas DL, Cox AL, Ray SC. Clearance of hepatitis C infection is associated with the early appearance of broad neutralizing antibody responses. Hepatology. 2014;59:2140–2151. doi: 10.1002/hep.27013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schiano TD, Charlton M, Younossi Z, Galun E, Pruett T, Tur-Kaspa R, Eren R, Dagan S, Graham N, Williams PV, et al. Monoclonal antibody HCV-AbXTL68 in patients undergoing liver transplantation for HCV: results of a phase 2 randomized study. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1381–1389. doi: 10.1002/lt.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galun E, Terrault NA, Eren R, Zauberman A, Nussbaum O, Terkieltaub D, Zohar M, Buchnik R, Ackerman Z, Safadi R, et al. Clinical evaluation (Phase I) of a human monoclonal antibody against hepatitis C virus: safety and antiviral activity. J Hepatol. 2007;46:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ilan E, Arazi J, Nussbaum O, Zauberman A, Eren R, Lubin I, Neville L, Ben-Moshe O, Kischitzky A, Litchi A, et al. The hepatitis C virus (HCV)-Trimera mouse: a model for evaluation of agents against HCV. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:153–161. doi: 10.1086/338266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Eren R, Landstein D, Terkieltaub D, Nussbaum O, Zauberman A, Ben-Porath J, Gopher J, Buchnick R, Kovjazin R, Rosenthal-Galili Z, et al. Preclinical evaluation of two neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies against hepatitis C virus (HCV): a potential treatment to prevent HCV reinfection in liver transplant patients. J Virol. 2006;80:2654–2664. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2654-2664.2006. [The study showed the weak neutralizing activity of HCV-AbXTL68 which likely explains its failure to impact recurrent HCV in the clinical trial.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang KS, Jiang J, Cai Z, Luo G. Human apolipoprotein e is required for infectivity and production of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. J Virol. 2007;81:13783–13793. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01091-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gastaminza P, Dryden KA, Boyd B, Wood MR, Law M, Yeager M, Chisari FV. Ultrastructural and biophysical characterization of hepatitis C virus particles produced in cell culture. J Virol. 2010;84:10999–11009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00526-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazumdar B, Banerjee A, Meyer K, Ray R. Hepatitis C virus E1 envelope glycoprotein interacts with apolipoproteins in facilitating entry into hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2011;54:1149–1156. doi: 10.1002/hep.24523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55*.Catanese MT, Uryu K, Kopp M, Edwards TJ, Andrus L, Rice WJ, Silvestry M, Kuhn RJ, Rice CM. Ultrastructural analysis of hepatitis C virus particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9505–9510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307527110. [One of the best attempts in the field to study the surface of HCV virions by EM and cryo-EM.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bassendine MF, Sheridan DA, Bridge SH, Felmlee DJ, Neely RD. Lipids and HCV. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyer A, Dumans A, Beaumont E, Etienne L, Roingeard P, Meunier JC. The association of hepatitis C virus glycoproteins with apolipoproteins E and B early in assembly is conserved in lipoviral particles. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:18904–18913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.538256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vieyres G, Dubuisson J, Pietschmann T. Incorporation of hepatitis C virus E1 and E2 glycoproteins: the keystones on a peculiar virion. Viruses. 2014;6:1149–1187. doi: 10.3390/v6031149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schofield DJ, Bartosch B, Shimizu YK, Allander T, Alter HJ, Emerson SU, Cosset FL, Purcell RH. Human monoclonal antibodies that react with the E2 glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus and possess neutralizing activity. Hepatology. 2005;42:1055–1062. doi: 10.1002/hep.20906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johansson DX, Voisset C, Tarr AW, Aung M, Ball JK, Dubuisson J, Persson MA. Human combinatorial libraries yield rare antibodies that broadly neutralize hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16269–16274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705522104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meunier JC, Russell RS, Goossens V, Priem S, Walter H, Depla E, Union A, Faulk KN, Bukh J, Emerson SU, et al. Isolation and characterization of broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to the e1 glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2008;82:966–973. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01872-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Broering TJ, Garrity KA, Boatright NK, Sloan SE, Sandor F, Thomas WD, Jr., Szabo G, Finberg RW, Ambrosino DM, Babcock GJ. Identification and characterization of broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies directed against the E2 envelope glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2009;83:12473–12482. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01138-09. [This paper described the isolation of bnAb HCV1 which was later shown to protect the chimpanzee model from challenge by a primary HCV inoculum and to significantly delay recurrent HCV in liver transplant patients.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63*.Keck ZY, Xia J, Wang Y, Wang W, Krey T, Prentoe J, Carlsen T, Li AY, Patel AH, Lemon SM, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies to a novel cluster of conformational epitopes on HCV E2 with resistance to neutralization escape in a genotype 2a isolate. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002653.. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002653. [This paper described the discovery and characterization of the HC84 series of bnAbs which target AS434 and block the production of escape mutants in cell culture.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64*.Keck Z, Wang W, Wang Y, Lau P, Carlsen TH, Prentoe J, Xia J, Patel AH, Bukh J, Foung SK. Cooperativity in virus neutralization by human monoclonal antibodies to two adjacent regions located at the amino terminus of hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein. J Virol. 2013;87:37–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01941-12. [This paper disproved the “interfering antibody” hypothesis.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65**.Giang E, Dorner M, Prentoe JC, Dreux M, Evans MJ, Bukh J, Rice CM, Ploss A, Burton DR, Law M. Human broadly neutralizing antibodies to the envelope glycoprotein complex of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114927109. [This paper described the isolation and characterization of bnAb AR4A to the E1E2 complex, and reported the potential association of E1 N-terminal region to the E2 stalk region.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66*.Morin TJ, Broering TJ, Leav BA, Blair BM, Rowley KJ, Boucher EN, Wang Y, Cheslock PS, Knauber M, Olsen DB, et al. Human monoclonal antibody HCV1 effectively prevents and treats HCV infection in chimpanzees. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002895. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002895. [This paper demonstrated the protective role of bnAb HCV1 against HCV in the chimpanzee model.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67*.de Jong YP, Dorner M, Mommersteeg MC, Xiao JW, Balazs AB, Robbins JB, Winer BY, Gerges S, Vega K, Labitt RN, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies abrogate established hepatitis C virus infection. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:254ra129. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009512. [This study made a surprising observation that bnAbs can treat established HCV infection in the humanized mouse model. The results suggested that HCV survival may depend on continuous spreading to new cells.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68*.Chung RT, Gordon FD, Curry MP, Schiano TD, Emre S, Corey K, Markmann JF, Hertl M, Pomposelli JJ, Pomfret EA, et al. Human monoclonal antibody MBL-HCV1 delays HCV viral rebound following liver transplantation: a randomized controlled study. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1047–1054. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12083. [This paper demonstrated the antiviral effect of bnAb HCV1 against recurrent HCV in humans.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Di Lorenzo C, Angus AG, Patel AH. Hepatitis C virus evasion mechanisms from neutralizing antibodies. Viruses. 2011;3:2280–2300. doi: 10.3390/v3112280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Y, Keck ZY, Foung SK. Neutralizing antibody response to hepatitis C virus. Viruses. 2011;3:2127–2145. doi: 10.3390/v3112127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fafi-Kremer S, Fauvelle C, Felmlee DJ, Zeisel MB, Lepiller Q, Fofana I, Heydmann L, Stoll-Keller F, Baumert TF. Neutralizing antibodies and pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Viruses. 2012;4:2016–2030. doi: 10.3390/v4102016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wahid A, Dubuisson J. Virus-neutralizing antibodies to hepatitis C virus. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:369–376. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Drummer HE. Challenges to the development of vaccines to hepatitis C virus that elicit neutralizing antibodies. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:329. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ball JK, Tarr AW, McKeating JA. The past, present and future of neutralizing antibodies for hepatitis C virus. Antiviral Res. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wellnitz S, Klumpp B, Barth H, Ito S, Depla E, Dubuisson J, Blum HE, Baumert TF. Binding of hepatitis C virus-like particles derived from infectious clone H77C to defined human cell lines. J Virol. 2002;76:1181–1193. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1181-1193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Triyatni M, Vergalla J, Davis AR, Hadlock KG, Foung SK, Liang TJ. Structural features of envelope proteins on hepatitis C virus-like particles as determined by anti-envelope monoclonal antibodies and CD81 binding. Virology. 2002;298:124–132. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Keck ZY, Op De Beeck A, Hadlock KG, Xia J, Li TK, Dubuisson J, Foung SK. Hepatitis C virus E2 has three immunogenic domains containing conformational epitopes with distinct properties and biological functions. J Virol. 2004;78:9224–9232. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9224-9232.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Keck ZY, Li TK, Xia J, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Dubuisson J, Foung SK. Analysis of a highly flexible conformational immunogenic domain a in hepatitis C virus E2. J Virol. 2005;79:13199–13208. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13199-13208.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keck ZY, Li TK, Xia J, Gal-Tanamy M, Olson O, Li SH, Patel AH, Ball JK, Lemon SM, Foung SK. Definition of a conserved immunodominant domain on hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein by neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2008;82:6061–6066. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02475-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Keck ZY, Machida K, Lai MM, Ball JK, Patel AH, Foung SK. Therapeutic control of hepatitis C virus: the role of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;317:1–38. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72146-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Keck ZY, Angus AG, Wang W, Lau P, Wang Y, Gatherer D, Patel AH, Foung SK. Non-random escape pathways from a broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibody map to a highly conserved region on the hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein encompassing amino acids 412-423. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004297. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Keck ZY, Olson O, Gal-Tanamy M, Xia J, Patel AH, Dreux M, Cosset FL, Lemon SM, Foung SK. A point mutation leading to hepatitis C virus escape from neutralization by a monoclonal antibody to a conserved conformational epitope. J Virol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00252-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Owsianka AM, Tarr AW, Keck ZY, Li TK, Witteveldt J, Adair R, Foung SK, Ball JK, Patel AH. Broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to the hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:653–659. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83386-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Iacob RE, Keck Z, Olson O, Foung SK, Tomer KB. Structural elucidation of critical residues involved in binding of human monoclonal antibodies to hepatitis C virus E2 envelope glycoprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Keck ZY, Saha A, Xia J, Wang Y, Lau P, Krey T, Rey FA, Foung SK. Mapping a region of hepatitis C virus E2 that is responsible for escape from neutralizing antibodies and a core CD81-binding region that does not tolerate neutralization escape mutations. J Virol. 2011;85:10451–10463. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05259-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86*.Krey T, Meola A, Keck ZY, Damier-Piolle L, Foung SK, Rey FA. Structural basis of HCV neutralization by human monoclonal antibodies resistant to viral neutralization escape. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003364. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003364. [This paper reported the structure of E2 AS434 in complex with bnAb HC84-1.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87**.Kong L, Giang E, Nieusma T, Kadam RU, Cogburn KE, Hua Y, Dai X, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Ward AB, et al. Hepatitis C virus E2 envelope glycoprotein core structure. Science. 2013;342:1090–1094. doi: 10.1126/science.1243876. [This first report of the E2 core domain (genotype 1a) surprisingly revealed a novel protein fold that was inconsistent with the previous proposal of E2 as a class II fusion protein. The study also reveals the different E2 antigenic surfaces, providing important information for vaccine design.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88**.Khan AG, Whidby J, Miller MT, Scarborough H, Zatorski AV, Cygan A, Price AA, Yost SA, Bohannon CD, Jacob J, et al. Structure of the core ectodomain of the hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein 2. Nature. 2014;509:381–384. doi: 10.1038/nature13117. [This paper reported another E2 core structure (genotype 2a) with a highly similar architecture as in the Kong et al. study, confirming the unusual protein fold of E2c.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang P, Wu CG, Mihalik K, Virata-Theimer ML, Yu MY, Alter HJ, Feinstone SM. Hepatitis C virus epitope-specific neutralizing antibodies in Igs prepared from human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8449–8454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703039104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang P, Zhong L, Struble EB, Watanabe H, Kachko A, Mihalik K, Virata-Theimer ML, Alter HJ, Feinstone S, Major M. Depletion of interfering antibodies in chronic hepatitis C patients and vaccinated chimpanzees reveals broad cross-genotype neutralizing activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7537–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sautto G, Mancini N, Diotti RA, Solforosi L, Clementi M, Burioni R. Anti-hepatitis C virus E2 (HCV/E2) glycoprotein monoclonal antibodies and neutralization interference. Antiviral Res. 2012;96:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92*.Tarr AW, Urbanowicz RA, Jayaraj D, Brown RJ, McKeating JA, Irving WL, Ball JK. Naturally occurring antibodies that recognize linear epitopes in the amino terminus of the hepatitis C virus e2 protein confer noninterfering, additive neutralization. J Virol. 2012;86:2739–2749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06492-11. [This paper disproved the “interfering antibody” hypothesis.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Owsianka A, Tarr AW, Juttla VS, Lavillette D, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Ball JK, Patel AH. Monoclonal antibody AP33 defines a broadly neutralizing epitope on the hepatitis C virus E2 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 2005;79:11095–11104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11095-11104.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94**.Kong L, Giang E, Robbins JB, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Law M. Structural basis of hepatitis C virus neutralization by broadly neutralizing antibody HCV1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9499–9504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202924109. [This paper reported the first structure of the bnAb HCV1 in complex with the AS412 peptide. The peptide formed a β-hairpin with the bnAb bound to its hydrophobic face. The structure provides very useful information for immunogen design.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95*.Kong L, Giang E, Nieusma T, Robbins JB, Deller MC, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA, Law M. Structure of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2 antigenic site 412 to 423 in complex with antibody AP33. J Virol. 2012;86:13085–13088. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01939-12. [This paper reported the second structure of the AS412 peptide in complex wtih bnAb AP33. The peptide structure is essentially the same as the HCV1 epitope.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96*.Potter JA, Owsianka AM, Jeffery N, Matthews DJ, Keck ZY, Lau P, Foung SK, Taylor GL, Patel AH. Toward a hepatitis C virus vaccine: the structural basis of hepatitis C virus neutralization by AP33, a broadly neutralizing antibody. J Virol. 2012;86:12923–12932. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02052-12. [This paper reported a second structure of the AS412 peptide in complex wtih bnAb AP33 around the same time.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pantua H, Diao J, Ultsch M, Hazen M, Mathieu M, McCutcheon K, Takeda K, Date S, Cheung TK, Phung Q, et al. Glycan shifting on hepatitis C virus (HCV) E2 glycoprotein is a mechanism for escape from broadly neutralizing antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:1899–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tarr AW, Owsianka AM, Jayaraj D, Brown RJ, Hickling TP, Irving WL, Patel AH, Ball JK. Determination of the human antibody response to the epitope defined by the hepatitis C virus-neutralizing monoclonal antibody AP33. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2991–3001. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ruwona TB, Giang E, Nieusma T, Law M. Fine mapping of murine antibody responses to immunization with a novel soluble form of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein complex. J Virol. 2014;88:10459–10471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01584-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gal-Tanamy M, Keck ZY, Yi M, McKeating JA, Patel AH, Foung SK, Lemon SM. In vitro selection of a neutralization-resistant hepatitis C virus escape mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19450–19455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809879105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meola A, Tarr AW, England P, Meredith LW, McClure CP, Foung SK, McKeating JA, Ball JK, Rey FA, Krey T. Structural flexibility of a conserved antigenic region in hepatitis C virus glycoprotein e2 recognized by broadly neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2015;89:2170–2181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02190-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102**.Li Y, Pierce BG, Wang Q, Keck ZY, Fuerst TR, Foung SK, Mariuzza RA. Structural Basis for Penetration of the Glycan Shield of Hepatitis C Virus E2 Glycoprotein by a Broadly Neutralizing Human Antibody. J Biol Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.643528. Epub 2015/03/05. [This study reported an alternative structure of AS412 recognized by the human bnAb HC33.1. The structure explains the relative resistance of this mAb to the glycan shift mutation at AS412.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tarr AW, Owsianka AM, Timms JM, McClure CP, Brown RJ, Hickling TP, Pietschmann T, Bartenschlager R, Patel AH, Ball JK. Characterization of the hepatitis C virus E2 epitope defined by the broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody AP33. Hepatology. 2006;43:592–601. doi: 10.1002/hep.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Deng L, Zhong L, Struble E, Duan H, Ma L, Harman C, Yan H, Virata-Theimer ML, Zhao Z, Feinstone S, et al. Structural evidence for a bifurcated mode of action in the antibody-mediated neutralization of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7418–7422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305306110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kohara M, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Maki N, Asano K, Yamaguchi K, Miki K, Tanaka S, Hattori N, Matsuura Y, Saito I, et al. Expression and characterization of glycoprotein gp35 of hepatitis C virus using recombinant vaccinia virus. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2313–2318. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-9-2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chien DY, Choo QL, Ralston R, Spaete R, Tong M, Houghton M, Kuo G. Persistence of HCV despite antibodies to both putative envelope glycoproteins. Lancet. 1993;342:933. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91983-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dubuisson J, Hsu HH, Cheung RC, Greenberg HB, Russell DG, Rice CM. Formation and intracellular localization of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein complexes expressed by recombinant vaccinia and Sindbis viruses. J Virol. 1994;68:6147–6160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6147-6160.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Keck ZY, Sung VM, Perkins S, Rowe J, Paul S, Liang TJ, Lai MM, Foung SK. Human monoclonal antibody to hepatitis C virus E1 glycoprotein that blocks virus attachment and viral infectivity. J Virol. 2004;78:7257–7263. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.7257-7263.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Meunier JC, Fournillier A, Choukhi A, Cahour A, Cocquerel L, Dubuisson J, Wychowski C. Analysis of the glycosylation sites of hepatitis C virus (HCV) glycoprotein E1 and the influence of E1 glycans on the formation of the HCV glycoprotein complex. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:887–896. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Voisset C, Dubuisson J. Functional hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins. Biol Cell. 2004;96:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brazzoli M, Helenius A, Foung SK, Houghton M, Abrignani S, Merola M. Folding and dimerization of hepatitis C virus E1 and E2 glycoproteins in stably transfected CHO cells. Virology. 2005;332:438–453. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cocquerel L, Meunier JC, Op de Beeck A, Bonte D, Wychowski C, Dubuisson J. Coexpression of hepatitis C virus envelope proteins E1 and E2 in cis improves the stability of membrane insertion of E2. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1629–1635. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-7-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Deleersnyder V, Pillez A, Wychowski C, Blight K, Xu J, Hahn YS, Rice CM, Dubuisson J. Formation of native hepatitis C virus glycoprotein complexes. J Virol. 1997;71:697–704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.697-704.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Patel J, Patel AH, McLauchlan J. The transmembrane domain of the hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein is required for correct folding of the E1 glycoprotein and native complex formation. Virology. 2001;279:58–68. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Michalak JP, Wychowski C, Choukhi A, Meunier JC, Ung S, Rice CM, Dubuisson J. Characterization of truncated forms of hepatitis C virus glycoproteins. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2299–2306. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-9-2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Flint M, Dubuisson J, Maidens C, Harrop R, Guile GR, Borrow P, McKeating JA. Functional characterization of intracellular and secreted forms of a truncated hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein. J Virol. 2000;74:702–709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.702-709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Patel AH, Wood J, Penin F, Dubuisson J, McKeating JA. Construction and characterization of chimeric hepatitis C virus E2 glycoproteins: analysis of regions critical for glycoprotein aggregation and CD81 binding. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2873–2883. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-12-2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Heile JM, Fong YL, Rosa D, Berger K, Saletti G, Campagnoli S, Bensi G, Capo S, Coates S, Crawford K, et al. Evaluation of hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2 for vaccine design: an endoplasmic reticulum-retained recombinant protein is superior to secreted recombinant protein and DNA-based vaccine candidates. J Virol. 2000;74:6885–6892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6885-6892.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bartosch B, Cosset FL. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus. Virology. 2006;348:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Krey T, d'Alayer J, Kikuti CM, Saulnier A, Damier-Piolle L, Petitpas I, Johansson DX, Tawar RG, Baron B, Robert B, et al. The disulfide bonds in glycoprotein E2 of hepatitis C virus reveal the tertiary organization of the molecule. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000762. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Whidby J, Mateu G, Scarborough H, Demeler B, Grakoui A, Marcotrigiano J. Blocking hepatitis C virus infection with recombinant form of envelope protein 2 ectodomain. J Virol. 2009;83:11078–11089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00800-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Flint M, Thomas JM, Maidens CM, Shotton C, Levy S, Barclay WS, McKeating JA. Functional analysis of cell surface-expressed hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein. J Virol. 1999;73:6782–6790. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6782-6790.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lavillette D, Pecheur EI, Donot P, Fresquet J, Molle J, Corbau R, Dreux M, Penin F, Cosset FL. Characterization of fusion determinants points to the involvement of three discrete regions of both E1 and E2 glycoproteins in the membrane fusion process of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2007;81:8752–8765. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02642-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Garry RF, Dash S. Proteomics computational analyses suggest that hepatitis C virus E1 and pestivirus E2 envelope glycoproteins are truncated class II fusion proteins. Virology. 2003;307:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Perez-Berna AJ, Moreno MR, Guillen J, Bernabeu A, Villalain J. The membrane-active regions of the hepatitis C virus E1 and E2 envelope glycoproteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3755–3768. doi: 10.1021/bi0523963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bruni R, Costantino A, Tritarelli E, Marcantonio C, Ciccozzi M, Rapicetta M, El Sawaf G, Giuliani A, Ciccaglione AR. A computational approach identifies two regions of Hepatitis C Virus E1 protein as interacting domains involved in viral fusion process. BMC Struct Biol. 2009;9:48. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-9-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li HF, Huang CH, Ai LS, Chuang CK, Chen SS. Mutagenesis of the fusion peptide-like domain of hepatitis C virus E1 glycoprotein: involvement in cell fusion and virus entry. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:89. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Taylor A, O'Leary JM, Pollock S, Zitzmann N. Conservation of hydrophobicity within viral envelope glycoproteins reveals a putative hepatitis C virus fusion peptide. Protein Pept Lett. 2009;16:815–822. doi: 10.2174/092986609788681779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Russell RS, Kawaguchi K, Meunier JC, Takikawa S, Faulk K, Bukh J, Purcell RH, Emerson SU. Mutational analysis of the hepatitis C virus E1 glycoprotein in retroviral pseudoparticles and cell-culture-derived H77/JFH1 chimeric infectious virus particles. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:621–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yu X, Qiao M, Atanasov I, Hu Z, Kato T, Liang TJ, Zhou ZH. Cryo-electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstructions of hepatitis C virus particles. Virology. 2007;367:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Drummer HE, Boo I, Poumbourios P. Mutagenesis of a conserved fusion peptide-like motif and membrane-proximal heptad-repeat region of hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E1. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1144–1148. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132*.El Omari K, Iourin O, Kadlec J, Fearn R, Hall DR, Harlos K, Grimes JM, Stuart DI. Pushing the limits of sulfur SAD phasing: de novo structure solution of the N-terminal domain of the ectodomain of HCV E1. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70:2197–2203. doi: 10.1107/S139900471401339X. [This paper reported the crystal structure of the N-terminal region of E1. The structure is unusual and showed that E1 formed previously unknown intermolecular disufide bridges.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.El Omari K, Iourin O, Kadlec J, Sutton G, Harlos K, Grimes JM, Stuart DI. Unexpected structure for the N-terminal domain of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E1. Nat Comm. 2014;5:4874. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fraser J, Boo I, Poumbourios P, Drummer HE. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 contain reduced cysteine residues essential for virus entry. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:31984–31992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wahid A, Helle F, Descamps V, Duverlie G, Penin F, Dubuisson J. Disulfide bonds in hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E1 control the assembly and entry functions of E2 glycoprotein. J Virol. 2013;87:1605–1617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02659-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Haynes BF, Kelsoe G, Harrison SC, Kepler TB. B-cell-lineage immunogen design in vaccine development with HIV-1 as a case study. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:423–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Burton DR, Ahmed R, Barouch DH, Butera ST, Crotty S, Godzik A, Kaufmann DE, McElrath MJ, Nussenzweig MC, Pulendran B, et al. A blueprint for HIV vaccine discovery. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Koff WC, Burton DR, Johnson PR, Walker BD, King CR, Nabel GJ, Ahmed R, Bhan MK, Plotkin SA. Accelerating next-generation vaccine development for global disease prevention. Science. 2013;340:1232910. doi: 10.1126/science.1232910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Nabel GJ. Designing tomorrow's vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:551–560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jardine J, Julien JP, Menis S, Ota T, Kalyuzhniy O, McGuire A, Sok D, Huang PS, MacPherson S, Jones M, et al. Rational HIV immunogen design to target specific germline B cell receptors. Science. 2013;340:711–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1234150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]