As the range of the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) expands into southern Quebec, cases of Lyme disease – caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted by blacklegged ticks – are also expected to rise. The authors of this article aimed to compare the experience, knowledge and practices regarding Lyme disease of physicians in Montérégie, a region affected by Lyme disease, with phyisicians in other regions not yet affected by the disease.

Keywords: Lyme disease; Health knowledge, attitudes, practice; Quebec

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Public health authorities in Quebec have responded to the progressive emergence of Lyme disease (LD) with surveillance activities and education for family physicians (FPs) who are key actors in both vigilance and case management.

OBJECTIVES:

To describe FPs’ clinical experience with LD, their degree of knowledge, and their practices in two areas, one with known infected tick populations (Montérégie) and one without (regions nearby Montérégie).

METHODS:

In the present descriptive cross-sectional study, FPs were recruited during educational sessions. They were asked to complete a questionnaire assessing their clinical experience with Lyme disease, their knowledge of signs and symptoms of LD, and their familiarity with accepted guidelines for diagnosing and treating LD in two clinical scenarios (tick bite and erythema migrans).

RESULTS:

A total of 201 FPs participated, mostly from Montérégie (n=151). Overall, results revealed a moderate lack of knowledge and suboptimal practices rather than systematically insufficient knowledge or inadequate practices. A majority of participants agreed to more education on LD. As expected, FPs from Montérégie had a higher clinical experience with tick bites (57% versus 25%), better knowledge of LD endemic areas in Canada and erythema migrans characteristics, and better management of erythema migrans (72% versus 50%).

CONCLUSION:

The present study documented the inappropriate intention to order serology tests for tick bites and the unjustified intention to use tick analysis for diagnostic purposes. Such practices should be discouraged because they are unnecessary and overuse collective laboratory and medical resources. In addition, public health authorities must pursue their education efforts regarding FPs to optimize case management.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Les autorités en santé publique du Québec ont répondu à l’émergence progressive de la maladie de Lyme (ML) par des activités de surveillance et des formations pour les médecins de famille (MF), qui sont des acteurs majeurs en matière de vigilance et de prise en charge.

OBJECTIFS :

Décrire l’expérience clinique des MF à l’égard de la ML, leur degré de connaissances et leurs pratiques dans deux régions, l’une comptant des populations connues de tiques infectées (Montérégie) et l’autre n’en comptant pas (régions à proximité de la Montérégie).

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Dans la présente étude transversale descriptive, les MF ont été recrutés pendant des séances de formation. Ils ont été invités à remplir un questionnaire visant à évaluer leur expérience clinique de la ML, leurs connaissances des signes et symptômes de cette maladie et leurs connaissances des directives acceptées pour diagnostiquer et traiter la ML pour deux scénarios cliniques (piqûre de tique et érythème migrant).

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, 201 MF ont participé, la plupart provenant de la Montérégie (n=151). Dans l’ensemble, les résultats ont révélé un manque modéré de connaissances et des pratiques sous-optimales plutôt que des connaissances systématiquement insuffisantes ou des pratiques inadéquates. La majorité des participants ont convenu avoir besoin de plus de formation sur la ML. Comme prévu, les MF de la Montérégie avaient une plus grande expérience clinique des piqûres de tique (57 % par rapport à 25 %), connaissaient mieux les régions endémiques de la ML au Canada et les caractéristiques de l’érythème migrant et prenaient mieux en charge l’érythème migrant (72 % par rapport à 50 %).

CONCLUSION :

La présente étude a permis de constater l’intention inappropriée de demander des tests sérologiques après une piqûre de tique et d’analyser les tiques pour corroborer le diagnostic de ML. Il faut décourager ces pratiques, car elles sont inutiles et favorisent la surutilisation collective des laboratoires et des ressources médicales. Par ailleurs, les autorités en santé publique doivent poursuivre leurs efforts de formation auprès des MF pour optimiser la prise en charge des cas.

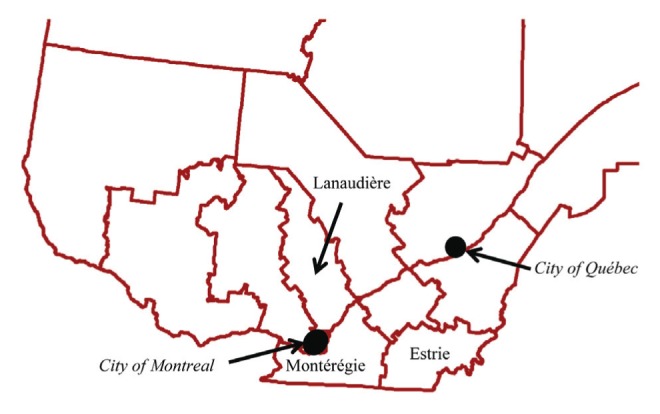

Lyme disease is a vector-borne zoonotic disease caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted by the tick Ixodes scapularis in the northeastern region of the United States bordering Canada (1), where this illness is endemic. It is the first tick-borne disease that has emerged in southwestern Quebec, more specifically in the region of Montérégie (2–4) (Figure 1). In 2008, a predictive model mapped high-risk regions for I scapularis establishment in the southern area of Quebec (5). Five areas were further confirmed by active surveillance in south-central Montérégie and along the Saint Lawrence River in Montérégie (3). None have been confirmed in the region of Estrie. The Lanaudière region was not sampled at that time because it was further away from the high-risk areas for tick establishment identified by the model. From 2010 to 2012, southern Quebec regional public health authorities conducted an awareness campaign of Lyme disease for family physicians and informed them about the areas with established tick populations in Montérégie. Since then, surveillance activities support that ticks have become established in high-risk areas further north and east of Montérégie (6). Lyme disease has been a reportable disease in Quebec since November 2003. Between 2004 and 2012 inclusively, 138 cases have been reported, with 101 of the cases contracted outside the province, 31 contracted indigenously and six unknown. Most of the indigenous cases occurred after exposure to the Montérégie region (27 of 31) (7). Despite the low number of reported cases, the average number of serologies for Lyme disease processed by the public health laboratory increased from 1380 in 2004 to 2600 in 2012 (B Serhir, Laboratoire national de santé publique du Quebec, personal communication, 2012). The annual number of positive serologies for new patients corresponds grossly to the number of declared cases of Lyme disease. Twenty-five patients with a positive serology were identified in 2011 and 43 were identified in 2012.

Figure 1).

Regions of Quebec included in the present study

Because of its emergence in southern Quebec, it is important to ensure that front-line practitioners know how best to manage these cases. A descriptive study of Quebec family physicians was performed to describe their clinical experience related to Lyme disease, their knowledge of the disease, and their familiarity with practices regarding the diagnosis and management of cases to validate whether these practices are compliant with the most recent guidelines (8). The value of such a study is to improve general practitioners’ knowledge and practices concerning this emerging disease and, if necessary, to optimize the management of individual patients and the use of collective resources.

METHODS

The present study was cross-sectional, descriptive and exploratory in nature. The target population was all family physicians whose principal place of practice was within Montérégie or within Estrie and Lanaudière, which are both border regions in southern Quebec. Family physicians were recruited during continuing medical education activities. Of the 15 professional associations contacted, 11 were interested in participating and seven allowed the authors to contact their members during the study period from May to September 2012. The study was briefly explained to the family physicians by one of the authors and they were invited to participate. Those who accepted provided the data for the study on site immediately. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Faculty of Medicine of the Université de Montréal (Montreal, Quebec; certificate 12-063-CERES-D) as well as by the ethics committees of relevant groups.

The measuring instrument used for data collection was a self-administered, anonymous two-page questionnaire featuring 19 questions: six questions on their profile; one question on their clinical experience with Lyme disease during the past year; five questions regarding their clinical practice; five questions regarding their knowledge; and two questions regarding their need for information. ‘Clinical experience with Lyme disease’ refers to whether a physician has encountered a patient who presents at least one feature of potential exposure to Lyme disease or has signs of exposure such as a tick on the body, tick bites, erythema migrans, etc. The questionnaire used was modelled after those used by Magri et al (9) and Henry et al (10) for the assessment of knowledge, beliefs and practices regarding Lyme disease. The authors merged and translated the questionnaires, and modified the questions regarding practice to take into account the frequent use of serological diagnosis in Quebec and the low number of cases actually diagnosed. To adapt to a region in which Lyme disease is emerging, clinical vignette answers included ‘don’t know’ and ‘need information’ as well as an answer combining the simultaneous prescription of serology and antibiotics. The resulting questionnaire was then reviewed by five experts in the field and pretested using a convenience sample of 10 family physicians before minor changes were made to obtain the final version (Supplementary Figure 1; go to www.pulsus.com).

Descriptive analyses were performed by dividing the respondents into two regions (Montérégie and outside Montérégie), taking into account that known populations of ticks carrying the Lyme disease agent were established only in Montérégie at the time. Proportions between the regions were compared using a Fisher’s exact test computed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, USA) with the significance level set at 0.05, and the 95% CIs around the proportions were calculated with an approximation of normal distribution. In addition, multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used to probe the existence of general practitioner subgroups within the data by finding similar answer profiles. MCA is a descriptive statistical technique designed to explore and visualize the relationships between ≥3 categorical variables (11). Beyond the intensive mathematical computation, the most interesting output of MCA is the representation of the several categorical variables on a two-dimensional map that minimizes deformation and underscores the relationships between categories of the variables included in the analysis. Each category is plotted on the map and interpreted based exclusively on their location. The two axes and the distances between points have no straightforward interpretation. Points in the middle of the figure, close to the axis origin, reveal categories that have no remarkable association with any other categories. On the other hand, points located away from the origin and found in approximately the same direction highlight some notable associations between the categories they represent. The analyzed variables were the management of a tick bite case, the identification and analysis of a tick for the diagnosis of Lyme disease, the recognition of erythema migrans, the management of erythema migrans, fever and erythema migrans as symptoms of the first stages of Lyme disease, as well as clinical experience with potential cases of Lyme disease. MCA was conducted using XLStat 2007.5 software (Addinsoft, France).

RESULTS

Participants were recruited during the course of 10 continuing medical education events between May and September 2012, three of which included a presentation on Lyme disease, among other topics. Physicians working in private practice, in hospitals and in local community service centers were reached. In total, 201 general practitioners answered the questionnaire, for a participation rate of 59% (ranging from 28% to 100%). Of the 201 participants, 151 (75%) practised in Montérégie and represented 11% of the general practitioners in this region (ranging from 3% to 19%) according to subregion. Compared with provincial statistics, the respondents had, on average, a higher number of years of practice (four or five additional years), and were more often in front-line practice exclusively, thus less so in hospitals (Table 1). This sample can be considered representative for the objectives of the present study.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents and comparison with regional and provincial data

| Present study, Montérégie | Present study, other regions | Province of Québec (13) | Province of Québec (14) | Montérégie (14) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 151 | 50 | 1525 | 7719 | 1427 |

| Women*, % | 53 (45–61)† | 68 (52–81) | 47 | NA | 55 |

| Average number of years in practice | 24.2 (22.3–26.0) | 23.1 (19.2–27.0) | NA | 19 | 19.2 |

| First-line practice exclusively, % | 60 (51–68) | 68 (52–81) | NA | 38 (37–39) | NA |

| Second-line practice exclusively, % | 7 (3–12) | 7 (2–18) | NA | 21 (20–22) | NA |

| Average number of patients seen per week | 78 (71–85) | 83 (69–97) | 81 (78–83) | NA | NA |

Data presented as mean (95% CI) unless otherwise indicated;

Of the 201 respondents overall, 14 from Montérégie and nine from the other regions did not specify sex; NA Not applicable

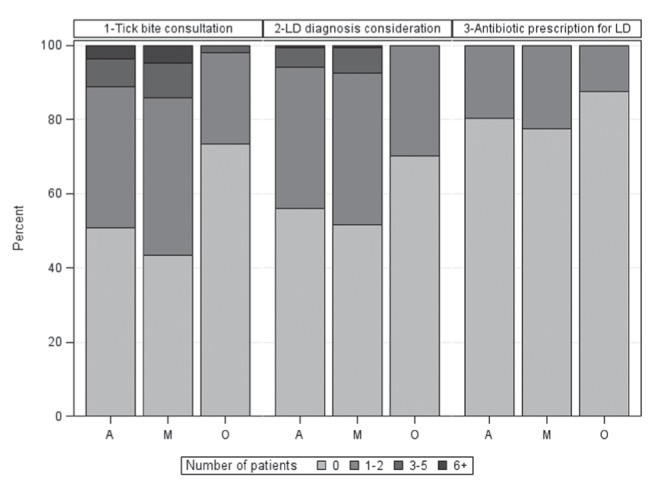

Answers regarding clinical experience with Lyme disease are presented in Figure 2. Fifty-one percent of the respondents had never experienced a tick bite consultation, 56% had never considered a diagnosis of Lyme disease and 80% had never prescribed antibiotics for Lyme disease. Most of the respondents with clinical experience were exposed to one or two cases. The proportion of respondents who had been consulted at least once for a tick bite was higher in Montérégie than in the others regions (57% [95% CI 48% to 65%] versus 27% [95% CI 15% to 41%]). The answers regarding management of cases are presented in Table 2. In the case of a consultation for a tick bite without any symptoms or other conditions, respondents were divided between the suggested answers – 30% of them needed information to manage the case and 26% chose the right answer (absence of serology and antibiotics, education of the patient and follow-up as needed). Four percent of the respondents decided to treat patients with antibiotics, which is not a routine procedure but may be offered for prevention of Lyme disease after a recognized tick bite in an area with a prevalence of ticks infected with B burgdorferi >20%. Twenty-one percent of physicians said that they would have managed the case differently if the same patient had been bitten in a known endemic area, while 34% had no opinion. Faced with erythema migrans, 66% correctly chose to prescribe antibiotics (with or without serology), while 25% needed more information to manage the case. Respondents from Montérégie and others regions differed with regard to their answers to the tick bite and erythema migrans questions. Compared with physicians from other regions, a lower proportion of respondents from Montérégie needed information to manage the patient and a higher proportion chose an appropriate management of erythema migrans by prescribing antibiotics (with or without serology) (72% [95% CI 64% to 79%] versus 50% [95% CI 38% to 63%]).

Figure 2).

Number of different patients seen in 2011 by family physicians in three clinical situations (tick bite consultation, Lyme disease [LD] diagnosis consideration, antibiotic prescription for LD) and according to region. A All; M Montérégie; O Other

TABLE 2.

Respondents’ practice regarding Lyme disease according to region

| Scenario | Montérégie (n=151) | Other regions (n=50) | Total (n=201) |

|---|---|---|---|

| You have a patient with a known tick bite, no symptoms, and normal findings on examination. What do you do or what would you do? (one choice only) | |||

| Serology for Lyme disease | 26 (17) | 5 (10) | 31 (16) |

| Antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease | 8 (5) | 0 (0) | 8 (4) |

| Serology and antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease | 34 (23) | 7 (14) | 41 (21) |

| No serology, no antibiotics, educate patient, follow up as needed | 41 (27) | 10 (20) | 51 (26) |

| I need more information to manage this patient | 34 (23) | 26 (53) | 60 (30) |

| Other action or treatment* | 7 (5) | 1 (2) | 8 (4) |

| Knowing that a patient’s tick bite occurred in an endemic area (an area with numerous ticks infected with Borrelia burgdorferi), does your patient management differ?† | |||

| No | 54 (47) | 9 (39) | 63 (45) |

| Yes (action added to their initial answer) | 21 (18) | 8 (35) | 29 (21) |

| Add serology and/or antibiotic | 18 | 8 | 26 |

| Tick analysis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| No serology, no antibiotics, educate patient, follow up as needed | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| No serology, antibiotics only | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Do not know, no answer, information needed | 41 (35) | 6 (26) | 47 (34) |

| You diagnose erythema migrans (erythematous skin lesion typical of Lyme disease) in a patient. | |||

| What do you do or what would you do? (one choice only) | |||

| Serology for Lyme disease | 11 (7) | 5 (10) | 16 (8) |

| Antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease | 8 (5) | 3 (6) | 11 (5) |

| Serology and antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease | 101 (67) | 22 (44) | 123 (61) |

| No serology, no antibiotics, educate patient, follow up as needed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I need more information to manage this patient | 31 (21) | 20 (40) | 51 (25) |

| Other action or treatment | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Data presented as n (%) or n. Number of respondents per vignette may differ from the total number of respondents because of a few missing answers

Action or treatment proposed: seven respondents mentioned an action related to ticks (tick identification and/or tick testing for B burgdorferi) and one respondent mentioned antibioprophylaxis;

Respondents needing information to manage a patient with a tick bite were removed from data.

Participants’ knowledge of Lyme disease and the expression of their need for information on the subject are presented in Table 3. Asked about the existence of Lyme disease in their practice region, 78% (95% CI 71% to 84%) of participants from Montérégie responded affirmatively (which is true according to the known population of ticks established in 2011–2012 in this region) compared with 53% (95% CI [39% to 67%]) for those from the other regions (where there was no known population of ticks established in 2011–2012, but where passerine birds could drop off infected ticks). Asked about their knowledge of endemic areas, 52% of all respondents declared knowing those in Canada, 66% in the United States and 10% in Europe. The proportions of those who did not answer were 16%, 9% and 31%, respectively. There appears to be a higher proportion of respondents who did not know the endemic areas in Canada in regions other than Montérégie (49% [95% CI 35% to 63%] versus 27% [95% CI 20% to 34%]). Regarding the characteristic that did not correspond to erythema migrans, 40% answered correctly among the four options suggested, while 26% indicated not knowing. There appears to be a higher proportion of respondents from Montérégie than from the other regions who knew characteristics of erythema migrans (46% [95% CI 38% to 54%] versus 24% [95% CI 12% to 36%]). Sending a tick taken from a patient to the laboratory for identification and searching for B burgdorferi was considered to be useful for the diagnosis of Lyme disease (which is false) by 69% of respondents and useful for identifying the areas at risk in the province of Quebec (which is true) by 88%. Regarding the symptoms associated with Lyme disease, a majority (≥75%) answered accurately for erythema migrans, fever, myalgia and arthralgia, while a minority (≤36%) answered accurately for atrioventricular block, cranial neuritis and diarrhea (the latter is not a symptom of Lyme disease). For these three symptoms, 42% to 52% of respondents indicated not knowing. A majority of respondents (≥84%) expressed a need for information for each of the three topics suggested: recognizing erythema migrans, laboratory tests and treatment. For providing this information, continuing medical education activity was chosen by 73% of respondents, medical literature by 63% and website by 48%. Physicians reported using various information sources on Lyme disease during the study period, with a preference for their public health newsletter (51%), a website (46%) or another professional (colleague, infectious disease specialist or public health physician) (26%). Eleven percent said they did not have any source of information at the time (7% in Montérégie and 22% in the other regions).

TABLE 3.

Respondents’ beliefs and knowledge regarding Lyme disease (LD)

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Believed a patient could contract LD in his practice region | |||

| Montérégie | 113 (78) | 10 (7) | 21 (15) |

| Other regions | 25 (53) | 13 (28) | 9 (19) |

| Total | 138 (72) | 23 (12) | 30 (16) |

| Knew LD-endemic areas in the United States | 129 (66) | 47 (24) | 18 (9) |

| Knew LD-endemic areas in Canada | 101 (52) | 64 (33) | 31 (16) |

| Knew LD-endemic areas in Europe | 18 (10) | 109 (59) | 57 (31) |

| Recognized characteristics that define erythema migrans (bull’s-eye lesion, expanding lesion [≥5 cm], occurs in 60% to 80% of cases, no pain) | 80 (40) | 67 (34) | 52 (26) |

| Believed that tick identification and tick testing for Borrelia burgdorferi is a decision tool for LD diagnosis | 133 (69) | 28 (14)* | 33 (17) |

| Believed that tick identification and tick testing for B burgdorferi is used to identify LD risk zones in Quebec | 173 (88)* | 3 (2) | 21 (11) |

| Recognized early signs and symptoms related to early stage LD | |||

| Fever | 131 (75)* | 21 (12) | 22 (13) |

| Erythema migrans | 169 (91)* | 7 (4) | 10 (5) |

| Myalgia and arthralgia | 126 (71)* | 31 (18) | 20 (11) |

| Auriculoventricular heart block | 7 (5)* | 75 (50) | 69 (46) |

| Cranial neuritis | 21 (14)* | 68 (44) | 64 (42) |

| Recognized early signs and symptoms not related to early stage LD | |||

| Diarrhea | 55 (36)* | 18 (12) | 80 (52) |

Data presented as n (%).

Correct answer

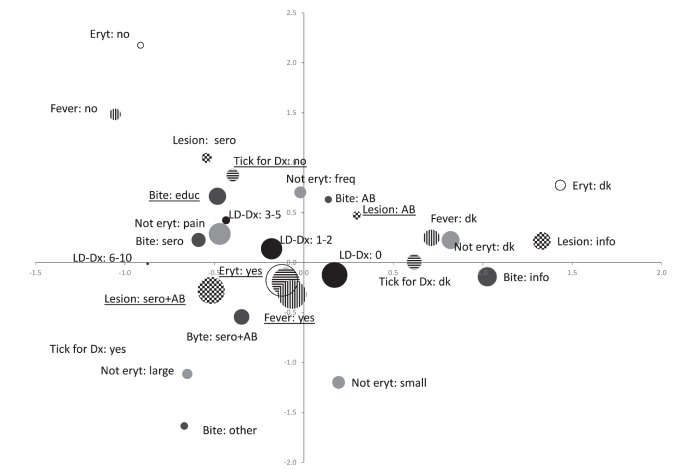

The MCA map shows four most striking features (Figure 3). Correct answers are not highly clustered, which means that physicians providing correct answers to all questions were uncommon. The answers indicating lack of knowledge (‘don’t know’ and ‘need more information’ combined) are clustered on the right side of the map, indicating a tendency of a lack of knowledge for several questions for some physicians. The bubbles showing the numbers of patients with possible Lyme disease seen in 2011 are distributed from the right to the left of the map and in the opposite direction of the answers, indicating a lack of knowledge and suggesting a positive relationship between the numbers of potential Lyme disease cases seen by physicians and their knowledge (whether accurate or not) about the disease. Finally, incorrect answers or those indicating a lack of knowledge are spread all over the map, indicating an absence of pattern for incorrect answers to several questions. This shows a moderate lack of knowledge among physicians rather than systematic insufficient knowledge or practices and shows that this gap tends to decrease with clinical experience.

Figure 3).

Map resulting from the multiple correspondence analysis of 151 general practitioners’ answers to six questions. The bubbles represent the relative location of each possible answer given for every question on the two-dimensional plan that shows most of the variability in the answers. The size of the bubbles is proportional to the number of respondents for the variable it represents. The questions were the following. 1) ‘When faced with a patient with a known tick bite but no symptoms and normal findings on examination, what do you do or what would you do?’ (dark gray bubble). The choices were ‘serology for Lyme disease’ (Bite: sero), ‘antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease’ (Bite: AB), ‘serology and antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease’ (Bite: sero+AB), ‘no serology, no antibiotics, educate patient, follow up as needed’ (Bite: educ), ‘I need more information to manage this patient’ (Bite: info), ‘other action or treatment’ (Bite: other). 2) ‘When faced with a patient with erythema migrans (erythematous skin lesion typical of Lyme disease), what do you do or what would you do?’ (checked bubble). The choices were ‘serology for Lyme disease’ (Lesion: sero), ‘antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease’ (Lesion: AB), ‘serology and antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease’ (Lesion: sero+AB), ‘no serology, no antibiotics, educate patient, follow up as needed’ (Lesion: educ), ‘I need more information to manage this patient’ (Lesion: info), ‘other action or treatment’ (Lesion: other). 3) ‘A patient brings you a tick that bit him/her. You send the tick to the laboratory for identification and to test for B burgdorferi. According to you, are the lab results useful for the diagnosis of Lyme disease?’ (horizontally striped bubble). Answer choices were ‘yes’ (Tick for Dx: yes), ‘no’ (Tick for Dx: no), and ‘don’t know’ (Tick for Dx: dk). 4) ‘What is the only characteristic that does not comply with the classical definition of erythema migrans?’ (light gray bubble). The choices were ‘bull’s-eye lesion’ (Not eryt: small), ‘expanding lesion larger than or equal to 5 cm’ (Not eryt: large), ‘lesion occurs in 60% to 80% of cases’ (Not eryt: freq), ‘painful lesion’ (Not eryt: pain), ‘don’t know’ (Not eryt: dk). 5) ‘In the case of fever, do you think the patient is in an acute phase of Lyme disease?’ (vertically striped bubble). The choices were ‘yes’ (Fever: yes), ‘no’ (Fever: no), or ‘don’t know’ (Fever: dk). 6) In a case of erythema migrans, do you think the patient is in an acute phase of Lyme disease?’ (white bubble). Choices were ‘yes’ (Eryt: yes), ‘no’ (Eryt: no), or ‘don’t know’ (Eryt: dk). Correct answers to the six questions are underlined on the map. Finally, the dark bubbles show the number of patients for whom the physician thought Lyme disease was a potential diagnosis during the year 2011 (LM-Dx: 0 patients, LM-Dx: 1–2 patients, LM-Dx: 3–5 patients and LM-Dx: 6–10 patients). See the figure highlights in the text.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, general practitioners’ clinical experience with Lyme disease in 2011 was relatively rare. In 2011, 49% of family physicians participating in the present study were consulted at least once for a tick bite and 44% considered a Lyme disease diagnosis at least once. Our study does not reveal any unsafe practices for the patient; however, it reveals some doctor misconceptions such as the intention to prescribe serology or antibiotherapy for a tick bite without any other symptoms and the intention to use tick analysis for human diagnostic purposes. Treatment of patients with antibiotics (doxycycline) is not a routine procedure but may be offered for prevention of Lyme disease after a recognized tick bite to adult patients and to children ≥8 years of age when all of the following circumstances exist: the attached tick can be reliably identified as an adult or nymphal I scapularis tick that is estimated to have been attached for ≥36 h on the basis of the tick’s degree of engorgement with blood or when there is certainty about the time of exposure to the tick; prophylaxis can be started within 72 h of the time that the tick was removed; ecological information indicates that the local prevalence of infection of these ticks with B burgdorferi is ≥20%; and doxycycline treatment is not contraindicated (8). In fact, antibiotic use for prevention of Lyme disease after a recognized tick bite is not recommended in Quebec because the prevalence of ticks infected with B burgdorferi is between 10% and 15%.

Family physicians’ knowledge should be improved both on a clinical level (symptoms of Lyme disease and characteristics of erythema migrans) and on an epidemiological level (areas at risk). Multiple correspondence analysis shows a lack of general knowledge rather than inaccurate knowledge or practice. Physicians recognize their need for training on several aspects of diagnosis and treatment of this disease. Family physicians from Montérégie distinguish themselves from those of the other regions because more of them were consulted for a tick bite, knew characteristics of erythema migrans and Lyme disease endemic zones in Canada, and chose an appropriate management of erythema migrans by prescribing antibiotics (with or without serology).

Differences in practice observed between family physicians from Montérégie and those of the other regions may be due to their clinical experience with tick bites or potential cases of Lyme disease as well as to the work of local public health authorities to develop awareness. In Montérégie, the public health newsletter provided physicians in 2010 and 2012 with critical information on epidemiology and clinical management of Lyme disease and their website made available various tools and reference documents. Since 2011–2012 in Estrie, the information on Lyme disease for professionals was updated on their website while no specific communication was made in Lanaudière. There is a small difference between the number of physicians who prescribed antibiotics for Lyme disease (n=38, one to two patients each) and the number of cases reported to public health authorities for the same period (n=32 in 2011). This difference may be due to a biased estimate during the study or to the underreporting of cases. There may be under-reporting of cases in Quebec; however, this is limited because physicians were encouraged to declare erythema migrans with compatible exposure, and the majority of physicians prescribe a serology in the presence of erythema migrans and a positive result is automatically reported to public health by the laboratory. Among physicians who did not need information to manage a patient with a tick bite, the proportion of physicians with an accurate answer (absence of serology and antibiotics, education of the patient and second consultation if needed) is lower than in similar studies conducted in low endemic areas (10) or moderately endemic areas (9,12), the proportion of physicians using only antibiotics (prophylactic antibiotic therapy) is equal to similar studies, and the proportion of physicians requesting a serology (with or without antibiotics) is higher. Among the physicians not needing information to manage a patient with erythema migrans, the proportion of physicians who prescribe antibiotics is similar to the other study conducted in a low endemic area (10).

One study limitation is the possible selection bias in terms of recruiting physicians with an interest in Lyme disease. Some physicians (n=47) were surveyed before training on Lyme disease; however, they have the same practices and knowledge as the other respondents. Recall bias exists for questions related to the number of cases in the past 12 months. The questionnaire was fine-scaled and there were very few answers in the higher categories. An overestimation for these questions is unlikely; an underestimation is possible, but is likely limited because a patient with suspected Lyme disease is noteworthy. The answers to the clinical vignettes may reflect what is medically expected rather than what would be done in reality. The options ‘don’t know’ and ‘need information was added to the questionnaire to limit this. Finally, some questions used a specific terminology, such as clinical manifestations in the early stages of Lyme disease, which may have been misinterpreted by some respondents.

CONCLUSION

The present study documents the inappropriate intention to order serology tests for tick bites and the unjustified intention to use tick analysis for diagnostic purposes, two practices that overuse the collective laboratory and medical resources. Public health authorities must provide more information to general practitioners to improve their knowledge and optimize management of cases. They must also communicate the usefulness of looking for ticks with B burgdorferi to keep our knowledge of risk areas current.

An increase in locally acquired cases was observed in Montérégie in 2013 and 2014, supporting the need to better inform family physicians. A follow-up study may be conducted to verify the impact of continuing information campaigns to raise awareness and improve practice. Research investigating the best methods for family physicians to acquire knowledge on slowly emerging diseases that do not manifest themselves as outbreaks would also be useful.

Footnotes

SOURCE OF FUNDING: This study was funded by the Fonds vert dans le cadre de l’Action 21 du Plan d’action 2006–2012 sur les changements climatiques du gouvernement du Quebec.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacon RM, Kiersten JK, Mead PS. Surveillance for Lyme disease-United States, 1992–2006. MMWR. 2008;57(SS10):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguon S, Milord F, Ogden NH, Trudel L, Lindsay LR, Bouchard C. Québec: Institut national de la santé publique du Québec; 2008. Étude épidémiologique sur les zoonoses transmises par les tiques dans le sud-ouest du Québec-Rapport de l’année 2007. < www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1139_EtudeZooonoses2007.pdf> (Accessed May 4, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguon S, Milord F, Trudel L, et al. Québec, QC: Institut national de la santé publique du Québec; 2009. Étude épidémiologique sur les zoonoses transmises par les tiques dans le sud-ouest du Québec – rapport de l’année 2008. < www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1140_EtudesZoonoses2008.pdf> (Accessed May 4, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden NH, Bouchard C, Kurtenbach K, et al. Active and passive surveillance and phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi elucidate the process of Lyme disease risk emergence in Canada. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:909–14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden N, St-Onge L, Barker I, et al. Risk maps for range expansion of the Lyme disease vector, Ixodes scapularis, in Canada now and with climate change. Int J Health Geogr. 2008;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrouillet C, Fortin A, Milord F, et al. Québec, QC: Institut national de la santé publique du Québec; 2014. Proposition d’un programme de surveillance intégré pour la maladie de Lyme et les autres maladies transmises par la tique Ixodes scapularis au Québec. < www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1819_Programme_Maladie_Lyme.pdf> (Accessed February 12, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milord F, Leblanc M-A, Markowski F, Rousseau M, Lévesque S, Dion R. Québec, QC: Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux; 2013. Flash Vigie: Surveillance de la maladie de Lyme au Québec – Bilan 2004–2012. < http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/acrobat/f/documentation/2006/06-271-02W-vol8_no5.pdf> (Accessed May 4, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wormser G, Dattwyler R, Shapiro E, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089–134. doi: 10.1086/508667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magri JM, Johnson MT, Herring TA, Greenblatt JF. Lyme disease knowledge, beliefs, and practices of New Hampshire primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:277–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry B, Crabtree A, Roth D, Blackman D, Morshed M. Lyme disease: Knowledge, beliefs, and practices of physicians in a low-endemic area. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e289–e95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenacre MJ. Theory and applications of correspondence analysis. London: Academic Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray T, Feder HM., Jr Management of tick bites and early Lyme disease: A survey of Connecticut physicians. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1367–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anonymous National Physician Survey. 2010. < http://nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/> (Accessed May 27, 2014).

- 14.Paré I, Ricard J. Le profil de pratique des médecins omnipraticiens québécois 2006–2007. 2e version. Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec, Québec, 2008. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec – ISBN 978-2-921361-51-4. < www.fmoq.org/fr/organization/clinical/resources/Lists/Billets/Post.aspx?ID=1> (Accessed May 4, 2014).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.