Abstract

Oxygen minimum zones are major sites of fixed nitrogen loss in the ocean. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of anaerobic ammonium oxidation, anammox, in pelagic nitrogen removal. Sources of ammonium for the anammox reaction, however, remain controversial, as heterotrophic denitrification and alternative anaerobic pathways of organic matter remineralization cannot account for the ammonium requirements of reported anammox rates. Here, we explore the significance of microaerobic respiration as a source of ammonium during organic matter degradation in the oxygen-deficient waters off Namibia and Peru. Experiments with additions of double-labelled oxygen revealed high aerobic activity in the upper OMZs, likely controlled by surface organic matter export. Consistently observed oxygen consumption in samples retrieved throughout the lower OMZs hints at efficient exploitation of vertically and laterally advected, oxygenated waters in this zone by aerobic microorganisms. In accordance, metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses identified genes encoding for aerobic terminal oxidases and demonstrated their expression by diverse microbial communities, even in virtually anoxic waters. Our results suggest that microaerobic respiration is a major mode of organic matter remineralization and source of ammonium (~45-100%) in the upper oxygen minimum zones, and reconcile hitherto observed mismatches between ammonium producing and consuming processes therein.

Introduction

Most of the organic matter in the world’s oceans is remineralized via aerobic respiration by heterotrophic microorganisms. Only when oxygen (O2) becomes scarce, microorganisms use thermodynamically less favourable electron acceptors, predominantly nitrate (NO3 -), for the oxidation of organic matter [1]. Large, permanently O2-depleted water masses favouring NO3 - respiration, so-called oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), are found in association with tropical and subtropical upwelling systems [2]. These regions are characterized by high surface productivity and thus strong O2 depletion via degradation of sinking organic matter at mid-depth, exacerbated by limited O2 replenishment [3]. Nitrate respiration in OMZs accounts for ~20–40% of global oceanic nitrogen (N) loss [4]. The N-deficient OMZ waters (relative to phosphorus) are eventually upwelled and result in largely N-limited surface primary production at low latitudes [5]. Hence, despite a combined volume of only ~1% (O2 ≤20 μmol l-1) of the global ocean [1], OMZs play an important role in regulating phytoplankton nutrient availability, and thus carbon (C) fixation in the oceans.

Traditionally, OMZ N-loss has been attributed to heterotrophic denitrification [6–8], the step-wise reduction of NO3 - to dinitrogen gas (N2) coupled to the oxidation of organic matter by facultative anaerobes at low O2 tensions [9]. In the last decade, however, numerous studies have identified anammox, the anaerobic oxidation of NH4 + with nitrite (NO2 -), as a major N2-forming pathway in OMZs, often exceeding N-loss via denitrification [10–14]. Assuming denitrification to be the only N-remineralization pathway in OMZs, anammox activity therein should be constrained by the amount of NH4 + released during heterotrophic denitrification [15,16]. The apparent decoupling of the two processes requires sources of NH4 + other than denitrification. Alternative anaerobic NH4 +-producing pathways in OMZs include heterotrophic NO3 - reduction to NO2 -, dissimilatory NO3 - reduction to NH4 + (DNRA) and sulphate reduction coupled to organic matter degradation [13,17–19]; yet, rates reported for these processes are neither sufficient to fully account for estimated remineralization of sinking organic matter in OMZs [14] nor to explain the NH4 + demands of concurrent anammox activity. Particularly large imbalances between NH4 + sources and sinks persist at the upper OMZ boundaries, where rates of anammox as well as aerobic NH4 + oxidation often peak [14,17,20,21].

Microaerobic respiration of organic matter has been suggested to provide the “missing” NH4 + in the upper OMZs [14,17]. Owing to the detection limit of conventional O2 measurements, remineralization of organic matter below ~5 μmol l-1 of O2 is commonly believed to proceed via NO3 - respiration [22]. However, during a recent hydrochemical survey of the South Pacific OMZ with switchable trace amount oxygen (STOX) sensors, accumulations of NO2 -, considered a proxy for active NO3 - respiration, were only observed at O2 levels <50 nmol l-1 [23]. At the same time, O2-dependent nitrification at O2 levels ≤1 μmol l-1 in OMZs hints at aerobic microbial respiration to be well adapted to nanomolar O2 concentrations [14,24,25]. In accordance, highly sensitive measurements of (microbial) O2 consumption in the OMZs off Chile and Mexico recently revealed apparent half-saturation coefficients (Km) for aerobic respiration of ~10–200 nmol O2 l-1 [26].

Highly efficient O2 scavenging is a prerequisite for maintaining anoxic conditions in OMZs against the transport of O2-bearing water masses via turbulent mixing, local downwelling or lateral advection. Fundamentally, the balance between microbial O2 uptake and downward O2 transport via turbulent diffusion results in a gradual decrease of O2 and the typical oxycline formation. In such a simplistic setting, sub-oxycline waters quickly become functionally anoxic [23]. Intrusions, local downwelling and lateral advection of oxygenated water masses, however, provide effective means of O2 transport into the OMZ interior [27,28]. To maintain anoxia in OMZs, such O2 injections must either be rare events or well-adapted, opportunistic microbial communities must rapidly draw down any O2 available.

Here, we assessed the potential of microaerobic respiration and the importance of aerobic organic matter degradation as a source of NH4 + in the OMZs off Namibia and Peru, using an 18-18O2 labelling approach suitable for O2 consumption measurements at low O2 concentrations [29]. Rate measurements were complemented by analyses of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes from the South Pacific OMZ, for presence and expression of key-functional genes involved in aerobic respiration. Further, we explored the effects of O2 depletion associated with marine snow particles on microbial respiration, by combining 18-18O2 labelling experiments with in-situ particle size analysis and modelling of aggregate-size-dependent respiration.

Materials and Methods

Water sampling and physico-chemical measurements

Samples were taken on cruises M76-2 and M77-3 over the Namibian shelf (May to June 2008) and in the OMZ off Peru (December 2008 to January 2009), respectively, on board R/V Meteor (Table 1). Seawater was collected with either a conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) rosette system fitted with 10-L Niskin bottles or a pump-CTD system (depth range: ~375 m). Off Namibia, a custom-built bottom water sampler [30] was used to collect additional samples from the benthic boundary layer (BBL). Oxygen was measured with a conventional amperometric microsensor and a CTD-mounted switchable trace amount oxygen (STOX) sensor [31] (detection limit: 50–100 nmol l-1) for high-accuracy O2 measurements at selected depths. Continuous vertical profiles of chlorophyll a were obtained fluorometrically and calibrated against discrete values derived from acetone extraction. Ammonium concentrations were determined fluorometrically [32] on discrete high-resolution samples (1–2 m). Samples for particulate organic nitrogen (PON) were filtered onto pre-combusted GF/F filters (Whatman), stored frozen, and measured on an elemental analyzer (EURO EA and Thermo Flash EA, 1112 Series) after drying and decalcification with fuming hydrochloric acid.

Table 1. Overview of sampling locations and times for the various types of data considered in this study.

| Cruise | OMZ | Lat/Lon | Year | Season | Data obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteor 76–2 | Namibia | 19–23°S/12-14°E | 2008 | Austral autumn | O2 consumption rates, N-cycling rates |

| MOOMZ-1 [34] | Chile | 20°07’S/70°23’W | 2008 | Austral winter | Terminal respiratory oxidase gene and transcript abundance |

| Meteor 77–3 | Peru | 4–16°S/75-84°W | 2008–2009 | Austral summer | O2 consumption rates, N-cycling rates, terminal respiratory oxidase gene abundance |

| Meteor 93 | Peru | 12–14°S /76-79°W | 2013 | Austral summer | In-situ particle size spectra |

Particle abundances and size distributions were measured during cruise M93 (February to March 2013) to the central Peruvian OMZ (Table 1), using an Underwater Vision Profiler (UVP5) [33]. A total of 138 UVP5 profiles, quantifying particles with an equivalent spherical diameter (ESD) of 0.06–26.8 mm, were obtained.

Determination of O2 consumption rates

Microaerobic respiration in the Namibian as well as the coastal and offshore Peruvian OMZ was measured as the consumption of 18-18O2 in time-series incubations. At each station, up to six depths were chosen for 18-18O2 labelling experiments (S1 Table). A detailed description of the experimental procedure is given in reference [29]. Briefly, Helium-purged water samples were adjusted to the following 18-18O2 concentrations by adding a defined volume of sterile-filtered seawater containing ~1 mmol 18-18O2 l-1 (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany): ~2.5 μmol l-1 (Namibian OMZ), ~2.5–7.5 μmol l-1 (upper Peruvian OMZ) and ~1 μmol l-1 (Peruvian OMZ core). At selected stations, additional O2 sensitivity assays were carried out, in which replicate samples were adjusted to different 18-18O2 concentrations in the range of ~0.5–20 μmol l-1 (S2 Table). Following O2 adjustment, subsamples were filled into 12-ml Exetainers (Labco, UK), using Helium overpressure to avoid 16-16O2 contaminations. One Exetainer each was sacrificed to determine initial total O2 (18-18O2 + 16-16O2) concentrations with a fast-responding Clark-type O2 microsensor (MPI Bremen; detection limit: ~0.5 μmol l-1). Samples were incubated in the dark at mean in-situ temperatures and duplicates were inactivated after ~0, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h by adding saturated mercuric chloride. Final 18-18O2 concentrations were determined using membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS; GAM200, IPI) in a shore-based laboratory. A two-point calibration was performed based on the 16-16O2 reading for air-saturated water pumped across the inlet membrane and the 18-18O2-background signal with the pump turned off. Oxygen consumption rates were calculated from the slope of linear regression of 18-18O2 concentrations as a function of time and corrected for 16-16O2 background concentrations. Samples incubated for ~48 h were not considered if a non-linear decrease of 18-18O2 was observed for the final incubation period (24–48 h).

Modelling of O2 consumption rates

The diffusive O2 flux at the upper OMZ boundary was calculated from turbulent diffusivity and the O2 concentration gradient according to Fick’s law. Oxygen consumption rates were then estimated from O2 flux gradients. A more detailed description of the modelling approach is given in the S1 File.

Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses

In the Peruvian OMZ, large-volume samples (>300 L) for nucleic acid extraction were collected onto 0.22-μm Durapore Membrane filters (Millipore), after passing an 8-μm pre-filter, using in-situ pumps (WTS-LV, McLane). Upon recovery, filters were immediately frozen and stored at -80°C until further analysis. DNA was extracted using a chloroform-phenol extraction protocol [35]. Sequencing of 2.5-μg DNA samples was done on a GS-FLX 454 pyrosequencer (Roche). A detailed description of the raw read processing as well as the functional (cytochrome oxidase type) and taxonomic sequence assignment is given in the S1 File.

Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data from the Chilean OMZ (<1.6 μm fraction; Table 1) were provided by F. Stewart and E. DeLong. For further details on sample collection, sequencing and sequence post-processing please refer to reference [34]. Here, BLAST hits for all non-replicate, non-rRNA sequences (DNA and cDNA) were analysed for gene abundance and expression of the various types of cytochrome oxidases and their taxonomic assignments.

Results and Discussion

Oxygen distributions

The stations investigated on the Namibian shelf (19°S-23°S) were characterized by high surface chlorophyll a concentrations, i.e. high primary productivity, at the time of sampling [25]. Oxygen concentrations in the surface waters ranged from ~150 to 250 μmol l-1 and gradually declined to ≤15 μmol l-1 (here used as a cut-off for the upper OMZ boundary) at ~65–85 m depth (Fig 1a and S1 Fig). At two sampling sites (station 225 and 252), steep O2 gradients in the upper OMZ as well as non-detectable levels of O2 (≤100 nmol l-1) by STOX sensor measurements in the lower OMZ (S1 Table), indicated apparently anoxic conditions over the shelf. In contrast, O2 concentrations in the lower micromolar range (~2–6 μmol l-1) persisted throughout the OMZ at nearby stations (231 and 243). Both O2 and density gradients indicated a rather weak stratification of the Namibian shelf waters, facilitating vertical mixing of more oxygenated surface waters into the OMZ.

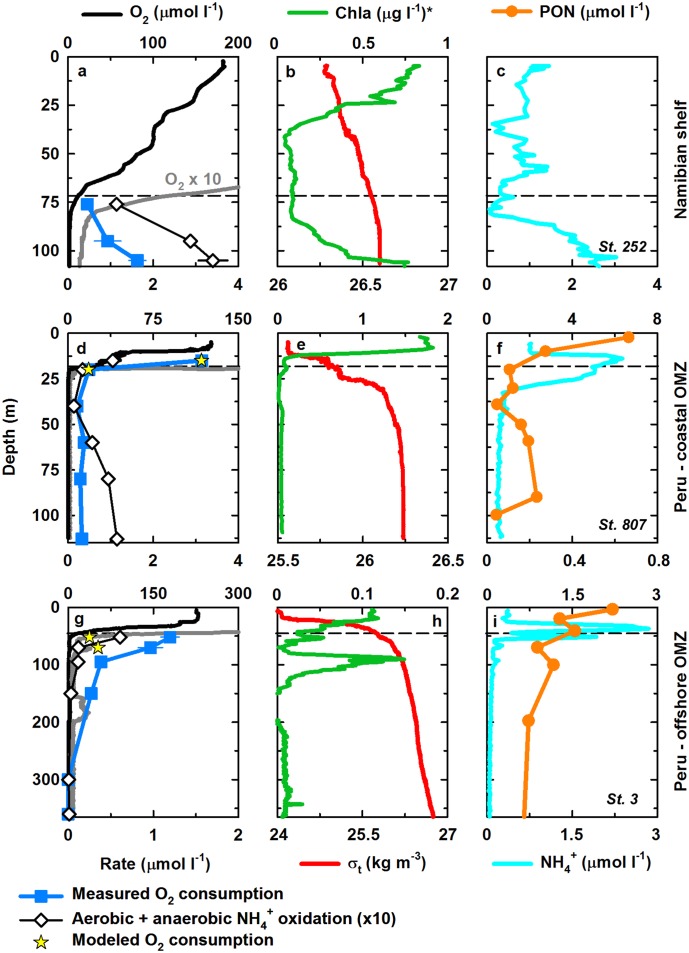

Fig 1. Physicochemical zonation and rates of microbial respiration in the OMZs off Namibia and Peru.

(a-c) Namibian shelf (station 252, 111m). (d-f) Peruvian coastal OMZ (station 807, 115 m). (g-i) Offshore Peruvian OMZ (station 3, 4697 m). Dashed lines indicate the upper OMZ boundary (O2 ≤15 μmol l-1). Previously determined rates of aerobic and anaerobic NH4 + oxidation [14,24,25] are tenfold magnified. Please note the differences in scale between stations. *Chlorophyll a concentrations in panel b in relative units.

In the OMZ off Peru (6°S-16°S), stations covered a wider range of productivity regimes [14]. Sampling sites ranged from highly productive, shallow coastal stations to more oligotrophic, deep offshore ones, as indicated by more than tenfold different chlorophyll a levels between stations (Fig 1e and 1h, S1 Fig). Off the central Peruvian coast, surface water O2 concentrations were as low as ~125 μmol l-1 (station 807) and rapidly declined to ≤15 μmol l-1 at ~20–30 m depth. Further offshore, the oxic mixed layer was more extensive, with the upper OMZ boundary typically located at ~50–70 m depth. Non-detectable O2 levels in the lower OMZ by STOX sensor measurements (≤50 nmol l-1; S1 Table) and cross-calibration of the data obtained by conventional O2 sensors with the STOX sensor data, indicated the onset of anoxia ~20–50 m below the OMZ boundary. In agreement, extensive STOX measurements during a recent hydrochemical survey of the South Pacific OMZ showed these waters to be O2-depleted down to at least 10 nmol l-1 [23]. Generally pronounced pycnoclines indicated a stronger vertical stratification off Peru, as compared to the Namibian shelf OMZ, and thus reduced mixing across the upper OMZ boundary. Further offshore, episodic lateral advection of O2-enriched waters into the lower OMZ was however clearly evident from local O2 maxima (5–25 μmol l-1) at 50–100 m below the oxycline (station 3 and 36; Fig 1g and S1 Fig).

Oxygen consumption rates

On the Namibian shelf, aerobic respiration was measured at four sampling sites in 18-18O2 labelling experiments, from the upper OMZ boundary down to the sediment-water interface (S1 Table). Oxygen consumption rates were fairly consistent between stations and depths, typically ranging from ~0.15 to 0.5 μmol O2 l-1 d-1, and showed no significant correlation with in-situ O2 concentrations (Spearman p >0.05). The latter may, at least in part, owe to the uniform 18-18O2 adjustments (~2.5 μmol l-1) of the incubations irrespective of in-situ O2 levels, thus stimulating or inhibiting aerobic respiration compared to in-situ activity. Noticeably higher rates (~1–1.6 μmol O2 l-1 d-1) were observed at one station (252) in the lower OMZ and the shelf bottom waters. In this zone, enhanced potential for aerobic respiration likely resulted from a high availability of fresh organic matter, as indicated by high chlorophyll a levels in the lower OMZ (Fig 1b).

Off Peru, 18-18O2 labelling experiments were carried out at seven stations, with 18-18O2 adjustments aimed at mimicking the O2 gradient from the upper OMZ boundary towards the OMZ core. Here, the incubations revealed a significant correlation between O2 consumption rates and in-situ O2 concentrations (Spearman R = 0.76, p ≤0.001), i.e. high aerobic respiration at the upper OMZ boundary and rapidly decreasing rates towards the OMZ core (Fig 1d and 1g, S1 Fig). Maximum O2 consumption rates in the upper OMZ waters were >3 μmol O2 l-1 d-1 near the Peruvian coast and declined to ~1 μmol O2 l-1 d-1 at the open ocean stations (S1 Table), consistent with observed shelf-offshore gradients in export production for the region [14]. In the lower (anoxic) Peruvian OMZ, potential rates of aerobic respiration showed little variability within and between stations, and typically ranged from ~0.2 to 0.4 μmol O2 l-1 d-1. At the stations furthest offshore, i.e. the least productive ones (station 3 and 5), O2 consumption in the core of the OMZ was below the detection limit of the 18-18O2 labelling approach employed here (~0.1 μmol O2 l-1 d-1).

Given the methodological challenges of accurately determining O2 concentrations in the lower micromolar range [29,31], very few direct measurements of aerobic respiration in OMZs exist for comparison. Oxygen consumption rates of similar magnitude (~0.5–2 μmol O2 l-1 d-1), have recently been measured using STOX sensors in low-O2 waters of the productive North and South Pacific coastal OMZs [26,31]. Earlier estimates of aerobic respiration in the Eastern Pacific upwelling regions based on particle flux attenuations [36] also compare well with upper OMZ respiration rates determined in this study. Calculating O2 flux gradients provides another indirect approach to estimate O2 consumption rates. Here, respiration rates were modelled for incubation depths near the upper OMZ boundary at selected stations off Peru (Fig 1d and 1g, S1 Fig). Modelled rates matched measured ones (±5%) at two sites (station 807 and station 36 at 90 m), but were significantly lower (~65–90%) for the remaining sampling locations. Higher experimentally determined O2 consumption rates may partially owe to a stimulation of aerobic respiration by slightly elevated 18-18O2 levels in the incubations compared to O2 concentrations in-situ. On the other hand, lower modelled respiration rates are expected since the diffusion-controlled 1-D model implies steady state conditions, and balances the rates with the vertical diffusive transport only. Any additional advective O2 transport and related transient effects are neglected, resulting in either similar or lower modelled respiration rates compared to measured ones. Indeed, local sub-oxycline O2 maxima can be observed at several stations (Fig 1g and S1 Fig), the majority of which are likely associated with advective O2 transport. In some instances, locally elevated O2 concentrations might indicate photosynthetic O2 production within the OMZ (Fig 1g and 1h) [26].

Overall, the lateral distribution of aerobic respiration at the upper OMZ boundaries, i.e. at micromolar O2 levels, appears to be largely controlled by the availability of organic matter, as indicated by maximum O2 consumption rates in organic-rich coastal waters (Fig 1f and 1i) [14,29]. Less variable, but significant potential for aerobic respiration was also consistently measurable in samples from apparently anoxic depths, particularly in the core of the Peruvian OMZ. Here, actual rates of microbial O2 consumption can be expected to primarily depend on the presence or absence of trace O2 concentrations. A recent study concluded that the South Pacific OMZ core is largely functionally anoxic and possibly only contains picomolar concentrations of O2, due to efficient O2 scavenging by microorganisms [23]. At the same time, however, the traditional view of largely static O2-deficient zones increasingly shifts towards temporally more dynamic OMZs. Large-scale observations indicate episodic O2 injections into the Peruvian OMZ via intrusions of oxygenated surface waters or mixing events, such as related to eddy activity [27,28]. Further, O2-bearing water layers surrounded by hundreds of meters of anoxic waters indicate lateral O2 supply into the OMZs (Fig 1g) [26]. These pulses of O2 can, at least temporarily, sustain aerobic respiration in otherwise anoxic waters. The total flux of O2 via episodic O2 injections is difficult to assess since the frequency of observations of sub-oxycline O2 maxima is likely reduced due to dispersion and efficient microbial O2 consumption. However, the importance of such transient O2 transport is indicated by recent biogeochemical modelling of the South Pacific OMZ, which hints at substantial aerobic organic matter degradation in the OMZ, and lateral advection as an important source of O2 for aerobic respiration therein [37].

Aerobic terminal oxidases gene abundance and expression

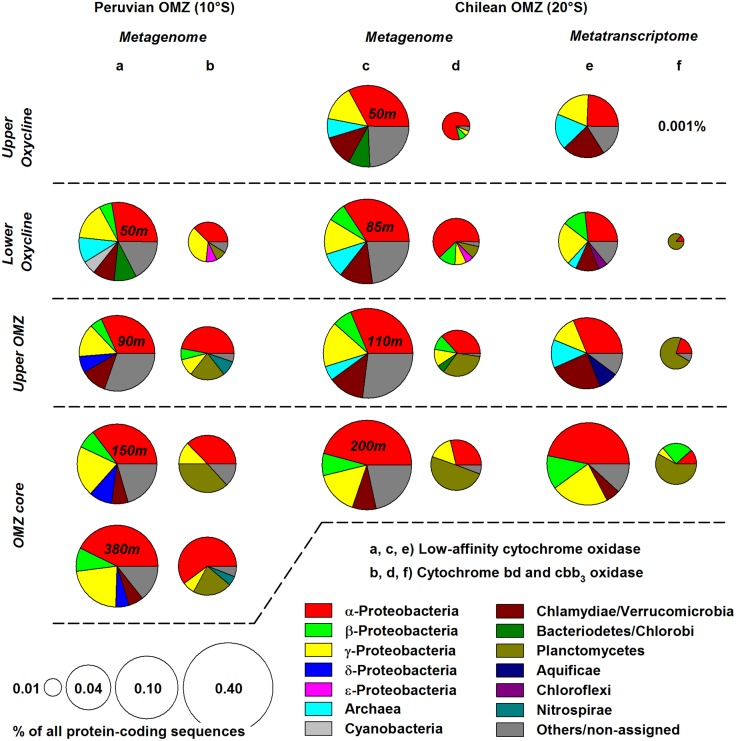

Identification of cytochrome oxidases, catalysing the terminal electron transfer during oxic respiration, in the South Pacific OMZ provided further evidence for active aerobic respiration at near-anoxic levels of O2. Metagenomes obtained in the Peruvian offshore OMZ (station 3) as well as metagenomes and metatranscriptomes previously collected off Chile [34], revealed presence and expression of genes encoding for low-affinity cytochrome c oxidases (Km ~200 nmol O2 l-1) as well as high-affinity cytochrome bd and cbb 3 oxidases (Km <10 nmol O2 l-1) [38] from the oxycline down to the OMZ core (Fig 2 and S3 Table).

Fig 2. Abundance of genes and transcripts encoding for terminal respiratory oxidases in the ETSP OMZ.

(a, b) Abundance of low-affinity (cytochrome c oxidase) and high-affinity (cytochrome bd and cbb3 oxidase) aerobic oxidases in the Peruvian OMZ (station 3). (c-f) Abundance and expression of cytochrome oxidase genes in the OMZ off Chile during cruise MOOMZ-1 [34]. Taxonomic affiliations of cytochrome oxidases are shown on domain, phylum or class level if represented by at least 5% of oxidase-coding sequences. Exact abundance and expression levels as well as taxonomic assignments of the individual types of cytochrome oxidases are given in S3 Table.

In all samples investigated, the majority of aerobic oxidase genes and gene transcripts were of the common low-affinity type (68–99%). Cytochrome c oxidases could largely be assigned to the phylum of Proteobacteria (mostly Alpha-, Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria), which is generally dominant in OMZs [39], followed by the Chlamydiae-Verrucomicrobia group. Consistent with a prior study [34], one of the most abundant taxa was the heterotrophic marine genus Pelagibacter (Alphaproteobacteria), accounting for up to 12% and 15% of all respiratory oxidase genes and gene transcripts, respectively, in the Chilean OMZ oxycline. In general, heterotrophs appeared to dominate the low-affinity type microbial community, yet also a number of cytochrome c oxidases strongly similar to those of marine chemo- and photoautotrophic prokaryotes were identified. Most notably, cytochrome c oxidases of the archaeal NH4 + oxidizer Nitrosopumilus maritimus were highly abundant and expressed (2–5% and 4–15% of all aerobic oxidase DNA and RNA sequences, respectively) in the oxycline and upper OMZ off Peru and Chile. In this zone, N. maritimus abundances, NH4 +-oxidizing activity as well as archaeal ammonia monooxygenase subunit A gene and transcript numbers are generally elevated [14,17,34,40,41]. Further, low-affinity oxidase genes and gene transcripts of NH4 +-oxidizing (Nitrosococcus and Nitrosomonas) and NO2 --oxidizing bacteria (Nitrobacter, Nitrococcus and Nitrospira) were detected throughout the OMZ, in line with active bacterial nitrification in the South Pacific [14,17,42] and other oceanic OMZs [25,43,44]. In addition, DNA and RNA sequences collected in the Peruvian and Chilean OMZ, respectively, matched cyanobacterial cytochrome c oxidases, mostly of the genus Prochlorococcus; off Peru, noticeably high abundances (1–5% of all aerobic oxidase DNA sequences) coincided with the deep chlorophyll a maximum (Fig 1h) as well as previously identified Prochlorococcus-specific marker pigments [45] at this station. These low-light-adapted cyanobacteria are widely distributed across the major OMZs [46,47], and likely also provide a local source of O2 via oxygenic photosynthesis well below the oxycline [26].

A large variety of aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms have adapted to microoxic environments by evolving terminal respiratory oxidases with high O2 affinities [38]. For example, the cytochrome bd oxidase of Escherichia coli with an apparent Km value of 3–8 nmol O2 l-1 is maximally expressed under microaerobic conditions [48,49], permitting aerobic growth at lower nanomolar, possibly even picomolar O2 concentrations [50]. Another high-affinity respiratory oxidase, the cytochrome cbb 3 oxidase, has a similarly low Km value of 7 nmol O2 l-1 [51]. Off the Peruvian and Chilean coasts, DNA and RNA sequences of both types of high-affinity oxidases could mostly be assigned to auto- and heterotrophic alpha-, beta and gammaproteobacterial taxa (e.g. Rosebacter, Ralstonia and sulphur-oxidizing symbionts, respectively) as well as Planctomycetes (Fig 2 and S3 Table). In the OMZ and lower oxycline, cytochrome bd and cbb 3 oxidases closely resembling those of the anammox bacterium Candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis (Planctomycetes) were present in particularly high abundances (up to 49% and 86% of all high-affinity type DNA and RNA sequences, respectively). Presumably, the O2-sensitive anammox bacteria [52] use high-affinity cytochrome oxidases as a means of detoxification [53], enabling them to remain active in a broader O2 regime [24]. Further, in the Peruvian OMZ metagenomes on average 6% of high-affinity oxidases identified were strongly similar to the cytochrome bd oxidase of the NO2 - oxidizer Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii, in line with active NO2 - oxidation at sub-micromolar O2 levels in the South Pacific OMZ [14,23].

Along the O2 gradients investigated, the relative abundance of aerobic oxidase genes and gene transcripts increased from the oxycline towards the lower OMZ. High-affinity cytochrome oxidases were particularly enriched in (near) anoxic zone samples, on both DNA and RNA level. Off Peru and Chile, the ratio of high-affinity to low-affinity oxidase-coding genes increased from 0.14 (50 m) to 0.31 (90–380 m) and 0.01 (50 m) to 0.12 (85-200m), respectively. Most notably, cytochrome bd and cbb 3 oxidase transcripts in the Chilean OMZ accounted for only 0.001% of all protein-coding sequences at the upper oxycline (~100 μmol O2 l-1) [34], while showing a 30-fold higher relative abundance (0.03%) in the presumably anoxic OMZ core (Fig 2f). A recent metatranscriptomic study of a sulphidic event off central Peru, similarly revealed a distinct trend of increasing cytochrome cbb 3 oxidase expression as O2 concentrations decreased [54]. Intriguingly, the ratio of high-affinity to low-affinity oxidase transcripts peaked at the lower oxycline and upper OMZ (0.17; 0 < O2 ≤10 μmol l-1). At the more oxygenated upper oxycline and at the OMZ core, where the diffusive O2 flux can be expected to equal zero, high-affinity type fractions were significantly reduced (0.12 and 0.04, respectively). Enhanced expression of high-affinity oxidases in the microoxic transition zone overlying the O2-depleted OMZ core clearly demonstrates the capacity of microorganisms to exploit sub-micromolar O2 concentrations. In corroboration, apparent Km values for aerobic respiration of 10–200 nmol O2 l-1 have recently been reported for the North and South Pacific OMZs [26,31]. Further, identification of cytochrome oxidase genes and gene transcripts revealed broadly similar microbial community compositions between the Chilean and Peruvian OMZ, suggesting microaerobic respiration to be a universal feature of oceanic OMZs. Hence, although O2 concentrations in OMZs remain largely below detection, O2-dependent nitrification and heterotrophic aerobic respiration still proceed, due to efficient O2 scavenging of microbial communities that are well adapted to these (transiently) microoxic environments.

Oxygen sensitivity of aerobic respiration

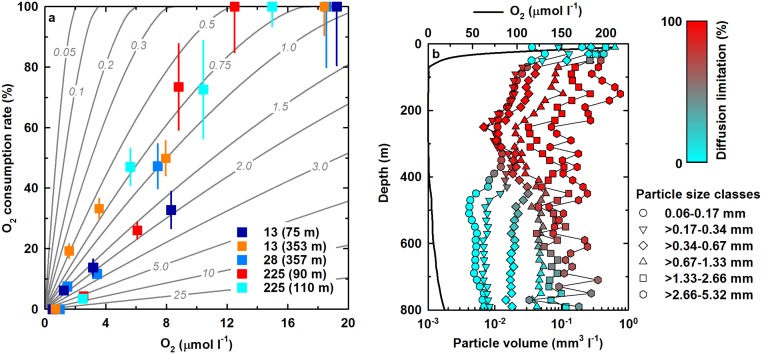

At the upper OMZ boundaries, steep O2 gradients mark the transition from oxic to anoxic environments. Experiments simulating changing O2 concentrations (~0.5–20 μmol l-1) in this transition zone, revealed a near-linear decrease of O2 consumptions rates with decreasing levels of O2 in the Namibian and Peruvian OMZ (Fig 3a and S2 Table); a surprising result, given that Km values of aerobic respiratory oxidases are two to three orders of magnitude lower than ambient O2 concentrations in the incubations. Recent studies targeting aerobic NH3 and NO2 - oxidation, showed both processes to be also mostly insensitive to decreasing O2 concentrations over the same range [14,24,25]. Assuming O2 consumption in our experiments to be largely coupled to heterotrophic activity, the apparent high O2 sensitivity observed here may result from O2 diffusion limitation of aggregate-associated organic matter respiration [29].

Fig 3. Oxygen sensitivity of aerobic respiration and OMZ particle size distributions.

(a) O2 sensitivity assays in the Namibian (station 225) and Peruvian OMZ (stations 13 and 28) during cruises M76 and M77-3, respectively. Oxygen consumption rates are given as percentages of the highest rate observed (= 100%) among all O2 treatments (see S2 Table for absolute rates). Error bars for O2 consumption rates are standard errors calculated from linear regression. Isolines (grey) indicate diffusion-limited respiration rates inside aggregates of 0.01–25 mm in diameter. A detailed description of how aggregate-size-dependent rates were calculated is included in the S1 File. (b) Vertical distribution of particle volumes (20 m bins) for six size classes between 0.06 and 5.32 mm (ESD) in the central Peruvian OMZ (12.62°S/77.55°W) during cruise M93. Color shading indicates diffusion limitation of aerobic respiration inside particles. For clarity, particles >5.32 mm are not depicted here. A more general overview of particle size distributions in the ETSP OMZ is given in S2 Fig.

High fluxes of particulate matter [36] and pronounced O2 deficiency in OMZs provide ideal conditions for the development of O2-depleted microenvironments [55,56]. Anoxic microniches inside marine snow aggregates have been suggested to exist at environmental O2 concentrations up to several tens of micromoles [57–59], thereby extending the effective anoxic OMZ volume [24]. In-situ particle size spectra in the Peruvian OMZ show a large fraction of particles larger than ~0.9 mm (Fig 3b, S2 Fig), above which size-dependent model results indicate diffusion-limited respiration for O2 ≤20 μmol l-1 (Fig 3a and 3b). Moreover, organic-rich aggregates are hot-spots of microbial activity [60], and large fractions of heterotrophic taxa in OMZs are particle-associated [61,62]. Hence, actual O2 levels encountered by much of the aerobic heterotrophic microbial community may be significantly lower than measured bulk concentrations. Likewise, anaerobic microorganisms that can be found in association with particles in OMZs, such as anammox bacteria [61], may in fact be exposed to O2 concentrations much lower than ambient levels. Indeed, a recent study revealed a tight coupling of aerobic and anaerobic N-cycling processes within cyanobacterial aggregates, and suggests aggregates to be important sites of N-loss at low ambient O2 [59]. Oxygen-reduced microniches might explain the observed apparent low O2 affinity and high O2 tolerance (>>1 μmol l-1) of aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms in OMZs, respectively, under stagnant experimental conditions [24]. Their true Km values for O2 as well as O2 sensitivities are more likely in the nanomolar range, i.e. closer to those reported from culture studies and stirred environmental samples, in which microbial O2 exposure equals ambient O2 levels [26,38,50,52,63].

Ammonium release by microaerobic organic matter respiration

Recent reports from major oceanic OMZs have shown that rates of both aerobic and anaerobic NH4 + oxidation (anammox) often peak near the upper OMZ boundary [13,14,17]. At the same time, anaerobic sources of NH4 + are generally insufficient to fully explain ammonium oxidation rates in this zone. Particularly denitrification, traditionally regarded as the major N-remineralization pathway in OMZs, remained largely undetectable in these studies. In light of so-far unidentified sources of NH4 +, the overall significance of anammox in OMZ N-loss has been questioned [64]. Instead, spatial variability in organic matter fluxes as well as in organic matter stoichiometry have been suggested to result in patchy and thus often missed denitrifying activity [16,65]. We compared the O2 consumption rates determined in this study with previously reported N-cycling rates for the same sampling sites [14,24,25]. In contrast to the proposed large-scale constraint of anammox activity by N-release via denitrification [16], our data suggest ammonium oxidation in the upper OMZs to be largely coupled to microaerobic organic matter remineralization.

Enhanced O2 consumption in the upper Peruvian OMZ coincided with a marked decrease in PON and concomitantly high NH4 + concentrations (~0.5–2 μmol l-1) in this zone (Fig 1f and 1i, S1 Fig), clearly indicating organic matter remineralization via aerobic respiration. For both the upper Peruvian and Namibian OMZ, on average 80% of measured O2 consumption were estimated to be due to the activity of heterotrophic microorganisms, when taking into account O2 consumption via aerobic NH4 + and NO2 - oxidation (Table 2). Compared to anaerobic remineralization pathways in this zone, these heterotrophic O2 consumption rates accounted for ~45–100% of organic matter degradation (assuming Redfield stoichiometry: C/N = 6.6), with the remainder mainly attributable to NO3 - reduction to NO2 -. Further, in waters off both Namibia and Peru rates of heterotrophic oxic respiration, and thus aerobic NH4 + release, were significantly correlated to rates of total (aerobic + anaerobic) NH4 + oxidation (Spearman R = 0.69 and 0.50, respectively, p <0.01), emphasizing the tight coupling of NH4 + producing and consuming processes in OMZs (Fig 1a, 1d and 1g, S1 Fig). Near the upper OMZ boundaries, aerobic as well as anaerobic NH4 + sources and sinks resulted in net rates of -36 to 365 nmol NH4 + l-1 d-1 (Table 2). Aerobic organic matter respiration could on average account for 91% of the NH4 + production.

Table 2. Ammonium budget for the upper Namibian and Peruvian OMZ considering aerobic and anaerobic NH4 +-producing and consuming processes.

For the sake of clarity, standard errors for the individual processes determined at each station are not listed here (typically ~10% of the measured rate). Directly measured rates are in italics, the remainder were inferred from idealized stoichiometries (see S1 File for further details). Liberation of NH4 + from organic matter via oxic as well as NO3 - respiration accounts for bacterial N-uptake assuming a growth efficiency of 0.15 [66] and a C/N ratio of 6.6 for the heterotrophic community [67,68].

| Namibian OMZ | Peruvian OMZ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station | 243 | 252 | 805 | 807 | 811 | 3 4 | 5 | 13 | 36 |

| Site characteristics | |||||||||

| Water depth (m) | 103 | 111 | 999 | 115 | 145 | 4,697 | 4,525 | 356 | 2,845 |

| Depth sampled (m) | 80 | 76 | 62 | 15 | 54 | 52 | 75 | 38 | 90 |

| O2 (μmol l-1) | 7.59 | 1.11 | 7.46 | ~20 | 4.16 | 4.01 | 2.60 | 3.40 | 1.49 |

| NH4 + (μmol l-1) | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 1.27 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Aerobic N cycling (nmol N l -1 d -1 ) | |||||||||

| NH 3 oxidation 1 | 21 | 93 | 89 | 49 | 13 | 60 | 5.8 | 14 | 35 |

| NO 2 - oxidation 1 | 74 | 112 | 38 | 928 | 70 | 35 | 32 | 29 | 186 |

| O 2 consumption (nmol O 2 l -1 d -1 ) | |||||||||

| Total oxic respiration | 230 | 450 | 541 | 3,136 | 605 | 1,195 | 730 | 990 | 1,060 |

| Heterotrophic oxic respiration 2 | 161 | 254 | 389 | 2,599 | 552 | 1087 | 706 | 954 | 915 |

| Anaerobic N cycling (nmol N l -1 d -1 ) | |||||||||

| NO 3 - reduction 1 | 17 | 370 | 18 | 1,010 | 0.0 | 40 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 42 |

| DNRA 1 | 0.0 | 12 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| Anammox 1 | 25 | 42 | 0.0 | 112 | 9.6 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 2.3 |

| NH 4 + sinks (nmol NH 4 + l -1 d -1 ) | |||||||||

| NH 3 oxidation | -21 | -93 | -89 | -49 | -13 | -60 | -5.8 | -14 | -35 |

| Anammox | -13 | -21 | 0.0 | -56 | -4.8 | -0.8 | -2.0 | -1.8 | -1.2 |

| NH 4 + sources (nmol NH 4 + l -1 d -1 ) | |||||||||

| Heterotrophic oxic respiration 3 | 21 | 33 | 50 | 333 | 71 | 139 | 91 | 122 | 117 |

| NO3 - reduction 3 | 1.1 | 24 | 1.1 | 65 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 |

| DNRA 3 | 0 | 17 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 |

| Net NH 4 + rate (nmol l -1 d -1 ) | -12 (±11) | -45 (±30) | -37 (±20) | 295 (±76) | 53 (±22) | 81 (±20) | 83 (±11) | 107 (±22) | 85 (±22) |

2 Heterotrophic oxic respiration = Total oxic respiration– 1.5 * NH3 oxidation– 0.5 * NO2 - oxidation.

3 Heterotrophic oxic respiration: O2/NH4 + = 106/16; NO3 - reduction: NO3 -/NH4 + = 212/16; DNRA: NO3 -/NH4 + = 53/69.

4 Station sampled for metagenomic analysis (Fig 2).

Obviously, estimates of NH4 + liberation from organic matter are highly sensitive to changes in the C/N ratio. Considering non-Redfieldian C/N ratios of 5.3 and 10.6, as observed for surface particulate matter in the Peruvian OMZ [45], results in an increase of 55% and a decrease of 61%, respectively, in aerobic NH4 + release (assuming a constant O2/C ratio). Regardless of the C/N scenario chosen, sufficient NH4 + is provided to fuel 90–100% of the combined demands of aerobic and anaerobic NH4 + oxidation at five out of six stations in the Peruvian OMZ. More negative NH4 + balances are observed for the shallow Namibian shelf OMZ. Here, sedimentary NH4 + release likely plays a more important role in driving N-loss via anammox (Fig 1c).

Conclusions

In summary, extensive rate measurements combined with metagenomic as well as metatranscriptomic analyses show widespread potential for microaerobic respiration in the Namibian and South Pacific OMZs. Microorganisms inhabiting the OMZ use high-affinity respiratory oxidases to exploit traces amounts of O2, brought in via intrusions of oxygenated surface waters, lateral advection of O2-bearing water masses, or produced locally by low-light adapted phytoplankton. At the upper OMZ boundary, where micromolar O2 concentrations persist, microaerobic respiration is the major mode of organic matter degradation and primary source of NH4 + for aerobic NH4 + oxidation and N-loss via anammox. The close spatial coupling of aerobic and anaerobic pathways in (O2-carrying) OMZ waters is likely facilitated by formation of O2-reduced microniches in sinking aggregates.

In current biogeochemical models, remineralization of organic matter exported to the OMZs is largely coupled to denitrification, typically resulting in overestimated N-loss from tropical and subtropical upwelling systems [22,69]. Denitrification by facultative anaerobic heterotrophs, however, only occurs under (near) anoxic conditions [63], and a large fraction of sinking organic matter is remineralized in more oxic upper OMZ waters. Considering aerobic microbial respiration as a major mode of remineralization of export production in this zone might help to improve model-based assessments of the current oceanic N-balance [37], as well as the effects of globally expanding OMZs and changing productivities on the ocean’s future N-budget.

Supporting Information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the governments of Namibia and Peru for access to their territorial waters. Our sincere thanks go to the cruise leaders Kay Emeis (M76-2) and Martin Frank (M77-3) as well as the crews of the cruises on board R/V Meteor for their support at sea. We are grateful for the technical and analytical assistance of Gabriele Klockgether, Daniela Franzke, Violeta Leon, Linda Sin, Jasmin Franz, Pelin Yilmaz, Nicole Pinnow, Sergio Contreras, Aurelien Paulmier, Andreas Ellrott and Volker Meyer. Frank Stewart and Ed DeLong are particularly thanked for providing metagenome and metatranscriptome sequence data from the Chilean OMZ. We thank Lars Stemmann for providing the UVP5.

Data Availability

NCBI Sequence Read Archive submission (SUB910041, SUB910044, SUB910045, and SUB910046) and all other relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors were supported by the following funders: TK, GL, CL, HS, DKD, HH, RK, JLR, RS, MIG, MMK: DFG-funded Sonderforschungsbereich 754 “Climate-Biogeochemistry Interactions in the Tropical Ocean” (www.sfb754.de); TK, GL, MMJ, MH, MMMK: Max Planck Society (www.mpg.de); TK: Canada Excellence Research Chair in Ocean Science and Technology (http://www.cerc.gc.ca/chairholders-titulaires/wallace-eng.aspx); NPR: European Research Council (http://erc.europa.eu), grant 267233, and Danish Council for Independent Research: Natural Sciences (http://ufm.dk/en/research-and-innovation/councils-and-commissions/the-danish-council-for-independent-research/the-council-1/the-danish-council-for-independent-research-natural-sciences), grants 10-083140 and 272-07-0057. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Lam P, Kuypers MMM. Microbial Nitrogen Cycling Processes in Oxygen Minimum Zones. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2011;3: 317–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Helly JJ, Levin LA. Global distribution of naturally occurring marine hypoxia on continental margins. Deep Res. 2004;51: 1159–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karstensen J, Stramma L, Visbeck M. Oxygen minimum zones in the eastern tropical Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Progr Ocean. 2008;77: 331–350. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gruber N. The Dynamics of the Marine Nitrogen Cycle and its Influence on Atmospheric CO2 In: Follows M, Oguz T, editors. The ocean carbon cycle and climate, NATO ASI Series. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic; 2004. pp. 97–148. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moore CM, Mills MM, Arrigo KR, Berman-Frank I, Bopp L, Boyd PW, et al. Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat Geosci. 2013;6: 701–710. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cline JD, Richards FA. Oxygen Deficient Conditions and Nitrate Reduction in the Eastern Tropical North Pacific Ocean. Limnol Ocean. American Society of Limnology and Oceanography; 1972;17: 885–900. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Codispoti LA, Packard TT. Denitrification Rates in the Eastern Tropical South-Pacific. J Mar Res. 1980;38: 453–477. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Naqvi SWA. Some aspects of the oxygen-deficient conditions and denitrification in the Arabian Sea. J Mar Res. 1987;45: 1049–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zumft WG. Cell Biology and Molecular Basis of Denitrification. Microbiol Molec Biol Rev. 1997;61: 533–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuypers MMM, Lavik G, Woebken D, Schmid M, Fuchs BM, Amann R, et al. Massive nitrogen loss from the Benguela upwelling system through anaerobic ammonium oxidation. PNAS. 2005;102: 6478–6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thamdrup B, Dalsgaard T, Jensen MM, Ulloa O, Farias L, Escribano R. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation in the oxygen-deficient waters off northern Chile. Limnol Ocean. 2006;51: 2145–2156. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hamersley MR, Lavik G, Woebken D, Rattray JE, Lam P, Hopmans EC, et al. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation in the Peruvian oxygen minimum zone. Limnol Ocean. 2007;52: 923–933. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jensen MM, Lam P, Revsbech NP, Nagel B, Gaye B, Jetten MSM, et al. Intensive nitrogen loss over the Omani Shelf due to anammox coupled with dissimilatory nitrite reduction to ammonium. ISME J. International Society for Microbial Ecology; 2011;5: 1660–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalvelage T, Lavik G, Lam P, Contreras S, Arteaga L, Löscher CR, et al. Nitrogen cycling driven by organic matter export in the South Pacific oxygen minimum zone. Nat Geosci. 2013;6: 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dalsgaard T, Canfield DE, Petersen J, Thamdrup B, Acuna-Gonzalez J. N2 production by the anammox reaction in the anoxic water column of Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica. Nature. 2003;422: 606–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Babbin AR, Keil RG, Devol AH, Ward BB. Organic Matter Stoichiometry, Flux, and Oxygen Control Nitrogen Loss in the Ocean. Science. 2014;344: 406–408. 10.1126/science.1248364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lam P, Lavik G, Jensen MM, van De Vossenberg J, Schmid M, Woebken D, et al. Revising the nitrogen cycle in the Peruvian oxygen minimum zone. PNAS. 2009;106: 4752–4757. 10.1073/pnas.0812444106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lipschultz F, Wofsy SC, Ward BB, Codispoti LA, Friedrich G, Elkins JW. Bacterial transformations of inorganic nitrogen in the oxygen-deficient waters of the Eastern Tropical South Pacific Ocean. Deep Res. 1990;37: 1513–1541. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Canfield DE, Stewart FJ, Thamdrup B, De Brabandere L, Dalsgaard T, Delong EF, et al. A Cryptic Sulfur Cycle in Oxygen-Minimum Zone Waters off the Chilean Coast. Science. 2010;330: 1375–1378. 10.1126/science.1196889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dalsgaard T, Thamdrup B, Farıas L, Revsbech NP. Anammox and denitrification in the oxygen minimum zone of the eastern South Pacific. Limnol Ocean. 2012;57: 1331–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Brabandere L, Canfield DE, Dalsgaard T, Friederich GE, Revsbech NP, Ulloa O, et al. Vertical partitioning of nitrogen-loss processes across the oxic-anoxic interface of an oceanic oxygen minimum zone. Environ Microbiol. 2013; 1462–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paulmier A, Kriest I, Oschlies A. Stoichiometries of remineralisation and denitrification in global biogeochemical ocean models. Biogeosciences. 2009;6: 2539–2566. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thamdrup B, Dalsgaard T, Revsbech NP. Widespread functional anoxia in the oxygen minimum zone of the eastern South Pacific. Deep Res I. Elsevier; 2012;65. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalvelage T, Jensen MM, Contreras S, Revsbech NP, Lam P, Günter M, et al. Oxygen Sensitivity of Anammox and Coupled N-Cycle Processes in Oxygen Minimum Zones. PLoS One. 2011;6: e29299 10.1371/journal.pone.0029299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Füssel J, Lam P, Lavik G, Jensen MM, Holtappels M, Günter M, et al. Nitrite oxidation in the Namibian oxygen minimum zone. ISME J. 2012;6: 1200–1209. 10.1038/ismej.2011.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tiano L, Garcia-Robledo E, Dalsgaard T, Devol AH, Ward BB, Ulloa O, et al. Oxygen distribution and aerobic respiration in the north and south eastern tropical Pacific oxygen minimum zones. Deep Sea Res I. 2014;94: 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whitmire AL, Letelier RM, Villagrán V, Ulloa O. Autonomous observations of in vivo fluorescence and particle backscattering in an oceanic oxygen minimum zone. Opt Express. 2009;17: 21992–22004. 10.1364/OE.17.021992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bertrand A, Ballón M, Chaigneau A. Acoustic Observation of Living Organisms Reveals the Upper Limit of the Oxygen Minimum Zone. PLoS One. 2010;5: e10330 10.1371/journal.pone.0010330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holtappels M, Tiano L, Kalvelage T, Lavik G, Revsbech NP, Kuypers MMM. Aquatic Respiration Rate Measurements at Low Oxygen Concentrations. Ivanovic Z, editor. PLoS One. 2014;9: e89369 10.1371/journal.pone.0089369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holtappels M, Kuypers MMM, Schlüter M, Brüchert V. Measurement and interpretation of solute concentration gradients in the benthic boundary layer. Limnol Ocean Methods. 2011;9: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Revsbech NP, Larsen LH, Gundersen J, Dalsgaard T, Ulloa O, Thamdrup B. Determination of ultra-low oxygen concentrations in oxygen minimum zones by the STOX sensor. Limnol Ocean Methods. 2009;7: 371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Holmes RM, Aminot A, Keroul R, Hooker BA, Peterson BJ. A simple and precise method for measuring ammonium in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1999;56: 1801–1808. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Picheral M, Guidi L, Stemmann L, Karl DM, Iddaoud G, Gorsky G. The Underwater Vision Profiler 5: An advanced instrument for high spatial resolution studies of particle size spectra and zooplankton. Limnol Ocean Methods. 2010;8: 462–473. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stewart FJ, Ulloa O, Delong EF. Microbial metatranscriptomics in a permanent marine oxygen minimum zone. Environ Microbiol. 2011;14: 23–40. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weiland N, Löscher C, Metzger R, Schmitz R. Construction and Screening of Marine Metagenomic Libraries In: Streit WR, Rolf D, editors. Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press; 2010. pp. 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Suess E. Particulate Organic-Carbon Flux in the Oceans—Surface Productivity and Oxygen Utilization. Nature. 1980;288: 260–263. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su B, Pahlow M, Wagner H, Oschlies A. What prevents nitrogen depletion in the oxygen minimum zone of the eastern tropical South Pacific? Biogeosciences. 2015;12: 1113–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morris RL, Schmidt TM. Shallow breathing: bacterial life at low O2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11: 205–212. 10.1038/nrmicro2970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wright JJ, Konwar KM, Hallam SJ. Microbial ecology of expanding oxygen minimum zones. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10: 381–394. 10.1038/nrmicro2778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Belmar L, Molina V, Ulloa O. Abundance and phylogenetic identity of archaeoplankton in the permanent oxygen minimum zone of the eastern tropical South Pacific. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2011;78: 314–326. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Löscher CR, Kock A, Koenneke M, LaRoche J, Bange HW, Schmitz RA. Production of oceanic nitrous oxide by ammonia-oxidizing archaea. Biogeosciences. 2012;9: 2419–2429. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ward BB, Glover HE, Lipschultz F. Chemoautotrophic Activity and Nitrification in the Oxygen Minimum Zone off Peru. Deep Res. 1989;36: 1031–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Beman JM, Shih JL, Popp BN. Nitrite oxidation in the upper water column and oxygen minimum zone of the eastern tropical North Pacific Ocean. ISME J. 2013;7: 2192–2205. 10.1038/ismej.2013.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lam P, Jensen MM, Kock A, Lettmann KA, Plancherel Y, Lavik G, et al. Origin and fate of the secondary nitrite maximum in the Arabian Sea. Biogeosciences. 2011;8: 1565–1577. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Franz J, Krahmann G, Lavik G, Grasse P, Dittmar T, Riebesell U. Dynamics and stoichiometry of nutrients and phytoplankton in waters influenced by the oxygen minimum zone in the eastern tropical Pacific. Deep Res I. 2012;62: 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goericke R, Olson RJ, Shalapyonok A. A novel niche for Prochlorococcus sp. in low-light suboxic environments in the Arabian Sea and the Eastern Tropical North Pacific. Deep Res I. 2000;47: 1183–1205. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lavin P, González B, Santibáñez JF, Scanlan DJ, Ulloa O. Novel lineages of Prochlorococcus thrive within the oxygen minimum zone of the eastern tropical South Pacific. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2010;2: 728–738. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. D´mello R, Hill S, Poolel RK. The cytochrome bd quinol oxidase in Escherichia coli has an extremely high oxygen affinity and two oxygen-binding haems: implications for regulation of activity in vivo by oxygen inhibition. Microbiology. 1996;142: 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tseng CP, Albrecht J, Gunsalus RP. Effect of microaerophilic cell growth conditions on expression of the aerobic (cyoABCDE and cydAB) and anaerobic (narGHJI, frdABCD, and dmsABC) respiratory pathway genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178: 1094–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stolper DA, Revsbech NP, Canfield DE. Aerobic growth at nanomolar oxygen concentrations. PNAS. 2010;107: 18755–18760. 10.1073/pnas.1013435107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Preisig O, Zufferey R, Appleby CA, Thöny-Meyer L, Hennecke H. A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178: 1532–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Strous M, Van Gerven E, Kuenen JG, Jetten M. Effects of Aerobic and Microaerobic Conditions on Anaerobic Ammonium-Oxidizing (Anammox) Sludge. App Environ Microbiol. 1997;63: 2446–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Das A, Silaghi-Dumitrescu R, Ljungdahl LG, Kurtz DMJ. Cytochrome bd Oxidase, Oxidative Stress, and Dioxygen Tolerance of the Strictly Anaerobic Bacterium Moorella thermoacetica. J Bacteriol. 2005;187: 2020–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schunck H, Lavik G, Desai DK, Großkopf T, Kalvelage T, Löscher CR, et al. Giant Hydrogen Sulfide Plume in the Oxygen Minimum Zone off Peru Supports Chemolithoautotrophy. PLoS One. 2013;8: e68661 10.1371/journal.pone.0068661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alldredge AL, Cohen Y. Can Microscale Chemical Patches Persist in the Sea? Microelectrode Study of Marine Snow, Fecal Pellets. Science. 1987;235: 689–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ploug H. Small-scale oxygen fluxes and remineralization in sinking aggregates. Limnol Ocean. 2001;46: 1624–1631. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shanks AL, Reeder ML. Reducing microzones and sulfide production in marine snow. Mar Ecol Progr Ser. 1993;96: 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ploug H, Kühl M, Buchholz-Cleven B, Jörgensen BB. Anoxic aggregates—an ephemeral phenomenon in the pelagic environment? Aquat Microb Ecol. 1997;13: 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Klawonn I, Bonaglia S, Brüchert V, Ploug H. Aerobic and anaerobic nitrogen transformation processes in N2-fixing cyanobacterial aggregates. ISME J. 2015;9: 1456–66. 10.1038/ismej.2014.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stocker R. Marine Microbes See a Sea of Gradients. Science. 2012;388: 628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Woebken D, Fuchs BA, Kuypers MAA, Amann R. Potential interactions of particle-associated anammox bacteria with bacterial and archaeal partners in the Namibian upwelling system. App Environ Microbiol. 2007;73: 4648–4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ganesh S, Parris DJ, Delong EF, Fallon SJ. Metagenomic analysis of size-fractioned picoplankton in a marine oxygen minimum zone. ISME J. 2014;8: 187–211. 10.1038/ismej.2013.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dalsgaard T, Stewart FJ, Thamdrup B, De Brabandere L, Revsbech NP, Ulloa O, et al. Oxygen at Nanomolar Levels Reversibly Suppresses Process Rates and Gene Expression in Anammox and Denitrification in the Oxygen Minimum Zone off Northern Chile. MBio. 2014;5: e01966–14. 10.1128/mBio.01966-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ward BB. How Nitrogen Is Lost. Science. 2013;341: 352–353. 10.1126/science.1240314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ward BB, Tuit CB, Jayakumar A, Rich JJ, Moffett J, Naqvi SWA. Organic carbon, and not copper, controls denitrification in oxygen minimum zones of the ocean. Deep Res I. 2008;55: 1672–1683. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Levipan HA, Quinones RA, Urrutia H. A time series of prokaryote secondary production in the oxygen minimum zone of the Humboldt current system, off central Chile. Progr Ocean. 2007;75: 531–549. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gundersen K, Heldal M, Norland S, Purdie DA, Knap AH. Elemental C, N, and P cell content of individual bacteria collected at the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS) site. Limnol Ocean. 2002;47: 1525–1530. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fukuda R, Ogawa H, Nagat T, Koike I. Direct Determination of Carbon and Nitrogen Contents of Natural Bacterial Assemblages in Marine Environments. App Environm Microbiol. 1998;64: 3352–3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Landolfi A, Dietze H, Koeve W, Oschlies A. Overlooked runaway feedback in the marine nitrogen cycle: the vicious cycle. Biogeosciences. 2013;10: 1351–1363. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

NCBI Sequence Read Archive submission (SUB910041, SUB910044, SUB910045, and SUB910046) and all other relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.