Abstract

Background

Communication and courtesy are important elements of consultations, but there is limited published data about the quality of trainee consults.

Objectives

This study assessed residents' views on consult interactions, evaluated the impact of the consult interactions on patient care, and developed and implemented a pocket card and training on trainee consults.

Methods

We surveyed resident and fellow physicians at Mount Sinai Hospital to assess perceptions, created a CONSULT card that uses a mnemonic for key elements, and developed a training session for how to call consults. We also conducted a consult training session using the CONSULT card as part of orientation in 2011 for all interns. We assessed the acceptability, feasibility, and sustainability of this intervention.

Results

Of 1001 trainees, 403 (40%) responded. Respondents reported that the most important components of calling consults included giving patient name, medical record number, and location (91%), and giving a clear question/reason (89%). Respondents also reported that these behaviors are done consistently for only 64%, and 10% of consults, respectively. Trainees reported that consult interactions affect the timeliness of treatment (62%), timeliness of tests performed (57%), appropriateness of diagnosis (56%), and discharge planning (49%). Approximately 300 interns attended the consult training session, and their feedback demonstrated acceptability and utility of the session.

Conclusions

Trainees believe that consult interactions impact patient care, but important components of the consult call are often missing. Our training and CONSULT card is an acceptable, feasible, and novel training intervention. Once developed, the training session and CONSULT card require minimal faculty time to deliver.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument used in this study.

Introduction

Physician engagement in interprofessional consults that involve high-quality communication and courtesy is a critical aspect of patient care.1,2 Clear communication is critical for conveying the reason for the consultation and requires understanding of pertinent medical information as well as displaying good interpersonal skills.3 With the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education's new milestones,4 skills in consultation are more explicitly defined, requiring that medical residents “[provide] consultation services for patients with basic and complex clinical problems.”5 Yet physician trainees often are undertrained and underprepared for consult interactions.3,4,6,7 Standardizing the information communicated during consultations may improve the quality of consults, and through this, patient care.3,8–10

The aim of this study was to develop and assess the feasibility of a training session and pocket guide for calling consults. The goals were (1) to assess residents' views on calling and responding to consults and the impact of consults on patient care, and (2) to develop a feasible, robust, and innovative method of training in calling consultations.

Methods

The study was performed at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York between October 2010 and December 2011. The 1001 eligible participants were all medical, surgical, and other residents and fellows.

Intervention

Our intervention development began with trainee focus groups about consults from October 2010 to January 2011 (results will be reported in a separate manuscript). Next, we developed a survey using the focus group findings, the literature,1 and institutional guidelines.11 The survey was reviewed by experts in the field and was pilot tested with 33 medicine residents to assess understanding and ease of completion. The survey assessed trainees' views on the importance and frequency of experiencing specific consult components during initial consult calls and a consultant's response using a 4-point Likert scale. The final section consisted of 6 questions on the impact of consultation interactions on patient care (provided as online supplemental material (524.3KB, docx) ). The survey was fielded to trainees from April to May 2011 using SurveyMonkey.

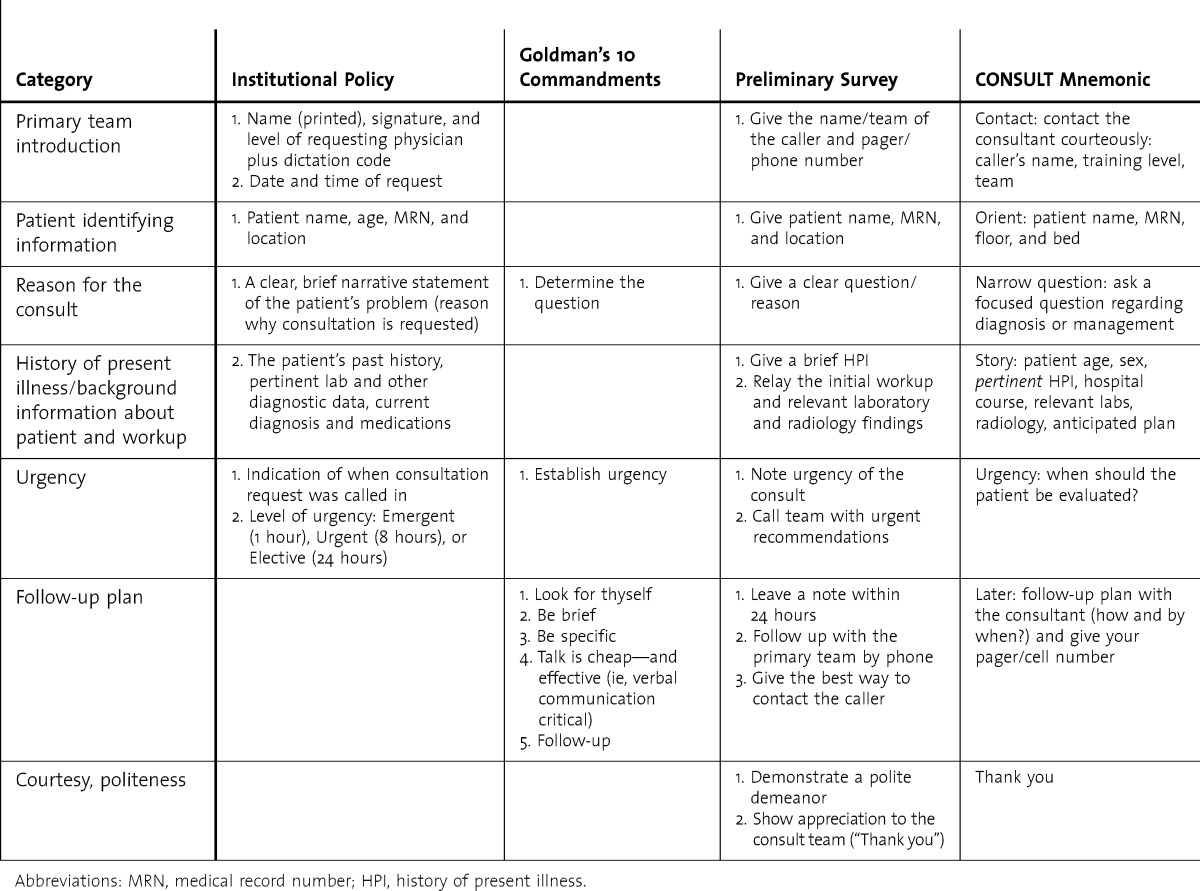

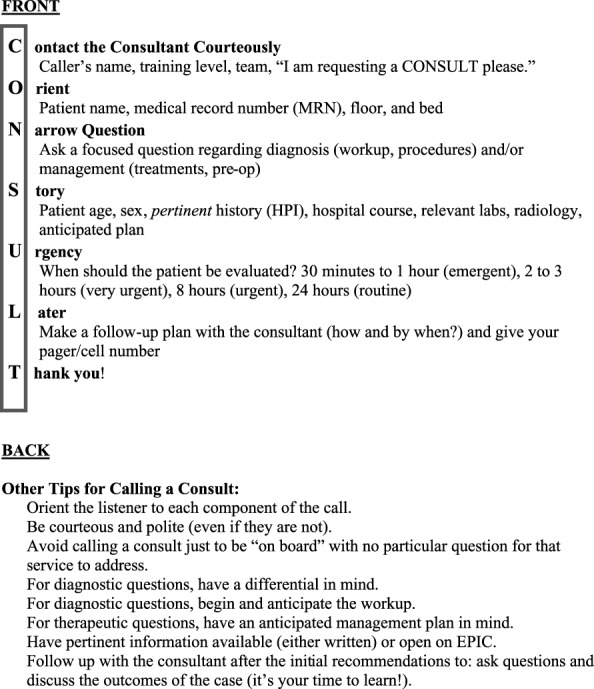

Using the results from the focus group and the survey, the authors developed a mnemonic tool to guide trainees in calling consults. Two investigators determined items using an iterative process via consensus; disagreements were resolved via negotiation or with the help of the third author when needed. Authors determined components that were most critical to the consult call by reviewing items rated “most important” by approximately 50% or more of the trainees in both the consult call and the response sections (table 1). The items rated most highly in our survey were compared with components addressed in Goldman's 10 Commandments1 and our institutional policy11 to create items in 7 categories. Investigators then ordered the categories. For example, because “reason for consult” is the most critical component of the consult call, yet is often overlooked, this should happen early on during the consult call, right after the introduction of the team and patient. Finally, the categories were crafted into phrases that fit into the CONSULT mnemonic (a word easily remembered in this context): Contact the consultant courteously, Orient (to the patient), Narrow question, Story (history of present illness and hospital course), Urgency, Later (plan for follow-up), and Thank you. The CONSULT card included the mnemonic, examples of phrasing, and important tips for the caller (figure).

TABLE 1.

Development of the Consult Mnemonic Using Institutional Guidelines,12 10 Commandments of Consultations,1 and Preliminary Survey

FIGURE.

CONSULT Card (Front and Back)

Our 40-minute training session consisted of 2 prerecorded videos of acted scenes demonstrating a poor quality and a high-quality consult, an interactive didactic session in which interns were asked to comment on the videos and their own experiences with consult interactions, and a role-play session in which interns were given cases and asked to practice calling consults with a partner. During orientation in July 2011, all 300 incoming interns were required to participate in a consult training session and were given the CONSULT card.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mount Sinai Hospital.

Analysis

We aggregated trainees' views about consults and perceived impact on patient care from the survey. We also assessed intern participation in the training session, feasibility of the development and teaching of the training session, acceptability of the intervention, and sustainability of the curriculum.

Results

Of 1001 residents and fellows, 403 (40%) responded. Trainees were evenly distributed across sex, postgraduate year, and residency type. Although many of the items were deemed very important, some components were not consistently done. For example, while a clear question was rated very important by most, only 10% (40 of 398) of trainees who responded felt that this was always done (table 2). The majority of respondents reported a large impact of the consultation interaction on timeliness of treatment (62%, 243 of 394), timeliness of tests performed (57%, 226 of 396), appropriateness of diagnosis of the patient (56%, 223 of 398), and discharge planning (49%, 196 of 398).

TABLE 2.

Trainees' Views on the Importance and Frequency of Consult Components by Consulter and Consultant

The survey findings were a key input in the development of the CONSULT card. Estimated faculty time to develop the card and didactic session was approximately 30 hours. Time needed for session delivery is 1 hour per session (15-minute prep, 45-minute delivery time) and is longer for new instructors (1-hour prep). The cost for 300 CONSULT cards is $100.

Comments from residents demonstrated benefit and acceptability. Residents appreciated the review of the standard protocol, the focus on key elements of the consult, and the opportunity for practice during the session. The training and CONSULT card have continued to be a part of the annual intern orientation for 4 years, and a video was recorded as an online module for future orientations. The session is also taught to fourth-year medical students during their introduction to internship clerkship. Anecdotally, the card is used by interns after the training session; many fourth-year medical students commented that the cards are very useful and the multiple modalities of teaching were interesting and interactive.

Discussion

The focused training and the CONSULT card have a number of strengths. The tool was developed in a sequential and multimodal approach, using results from earlier phases of the study to inform subsequent sections as well as institutional policy and literature. The unique educational approach was brief, engaging, interactive, and can target many trainees at one time. The card also gave a lasting reminder of the mnemonic tool for future use. In addition, the training and CONSULT card are easy to use and feasible to integrate into physician training. The upkeep of the training is just 15 to 60 minutes of preparation each year, demonstrating sustainability. The most novel component of the intervention is highlighting the importance of courtesy between the consultant and consulter, which has not been included in consult mnemonics currently in the literature.12,13

There are several limitations to this study. We did not use a validated survey instrument, and misunderstanding the survey questions could affect the results. The study was conducted at a single institution, limiting generalizability. In the future, the impact of the training and CONSULT card on trainees' direct skills in calling consults, as well as the impact on patient outcomes, such as time to appropriate testing or discharge, should be evaluated. It also may be beneficial to develop a training intervention targeted toward the consultants to focus on collaboration and teaching during consult encounters.

Conclusion

Residents from multiple disciplines believed that consult interactions have a major impact on patient care. A brief institutional training session and mnemonic-based CONSULT card were developed based on literature, resident input, and institutional policy. These tools were found to be acceptable and feasible across specialties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Deborah Korenstein, MD, Adjunct Associate Professor of Medicine, General Internal Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Footnotes

Anna Podolsky, AB, is a Medical Student, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; David T. Stern, MD, PhD, is Professor of Medicine and Vice-Chair for Education and Academic Affairs, Department of Medicine, New York University Langone Medical Center, and Chief of the Medicine Service, VA NY Harbor Healthcare-Manhattan; and Lauren Peccoralo, MD, MPH, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Funding: Funding for this project was provided by the Northeast Group on Educational Affairs (NEGEA).

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

This research was previously presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Denver, CO, April 2013, as a poster presentation; at the NEGEA Annual Retreat in New York, NY, April 2013, as a short communication; and at the NEGEA Annual Retreat in Boston, MA, March 2012, as a poster presentation.

References

- 1.Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go S, Richards DM, Watson WA. Enhancing medical student consultation request skills in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):659–662. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern DT. Practicing what we preach? An analysis of the curriculum of values in medical education. Am J Med. 1998;104(6):569–575. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan G, Simpson D, Cooney T, Beresin E. A milestone in the milestones movement: the JGME Milestones Supplement. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1 suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.4300/JGME-05-01s1-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Internal Medicine. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler CS, Chan T, Loeb JM, Malka T. I'm clear, you're clear, we're all clear: improving consultation communication skills in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):753–758. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ff953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee T, Pappius EM, Goldman L. Impact of inter-physician communication on the effectiveness of medical consultations. Am J Med. 1983;74(1):106–112. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson SD. Principles of generalist-specialist relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(suppl 1):13–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Peterson LA, Studdert DM. Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2030–2036. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foy R, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, Suttorp M, Seelig M, Shanman R, et al. Meta-analysis: effect of interactive communication between collaborating primary care physicians and specialists. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):247–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-4-201002160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mount Sinai Hospital. Institutional Guidelines. http://intranet1.mountsinai.org/admin_policies/rules_regs/body_rules_regs09.html#_Toc22524129. Accessed August 31, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler CS, Afshar Y, Sardar G, Yudkowsky R, Ankel F, Schwartz A. A prospective, randomized, controlled study demonstrating a novel, effective model of transfer of care between physicians: the 5 Cs of consultation. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(8):968–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan T, Orlich D, Kulasegaram K, Sherbino J. Understanding communication between emergency and consulting physicians: a qualitative study that describes and defines the essential elements of the emergency department consultationreferral process for the junior learner. CJEM. 2013;15(1):42–51. doi: 10.2310/8000.2012.120762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.