Abstract

Background

Pediatricians underestimate the prevalence of substance misuse among children and adolescents and often fail to screen for and intervene in practice. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends training in Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), but training outcomes and skill acquisition are rarely assessed.

Objective

We compared the effects of online versus in-person SBIRT training on pediatrics residents' knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and skills.

Methods

Forty pediatrics residents were randomized to receive either online or in-person training. Skills were assessed by pre- and posttraining standardized patient interviews that were coded for SBIRT-adherent and -nonadherent behaviors and global skills by 2 trained coders. Thirty-two residents also completed pre- and postsurveys of their substance use knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (KABs). Two-way repeated measures multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) and analyses of variance (ANOVAs) estimates were used to assess group differences in skill acquisition and KABs.

Results

Findings indicated that both groups demonstrated skill improvement from pre- to postassessment. Results indicated that both groups increased their knowledge, self-reported behaviors, confidence, and readiness with no significant between-group differences. Follow-up univariate analyses indicated that, while both groups increased their SBIRT-adherent skills, the online training group displayed more “undesirable” behaviors posttraining.

Conclusions

The current study indicates that brief training, online or in-person, can increase pediatrics residents' SBIRT skills, knowledge, self-reported behaviors, confidence, and readiness. The findings further indicate that in-person training may have incremental benefit in teaching residents what not to do.

What was known and gap

Approximately one third of pediatric residencies offer training to prepare physicians to identify and address substance abuse, yet the impact of training on knowledge and skills often is not assessed.

What is new

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) training increased residents' knowledge, self-reported behaviors, and confidence.

Limitations

Single institution study, small sample, and lack of data for performance in practice reduce generalizability.

Bottom line

Online and in-person training increased residents' skills and confidence. In-person training was more effective for teaching residents what not to do.

Introduction

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recommends universal screening, brief intervention, and/or referral to treatment (SBIRT) for risky substance use as part of routine health care.1 Pediatricians play an important role in the prevention of risky substance use and related problems among children and adolescents,2–6 yet pediatricians often underestimate substance use and fail to appropriately screen for risk.7,8 Providers report lack of confidence in their skills to manage substance abuse as a barrier,9 highlighting the need for quality training in SBIRT.

SBIRT includes several steps: (1) screening, or quickly assessing for substance use risk and the need for intervention or referral; (2) brief intervention, or increasing patients' awareness of the impact of substance use and enhancing motivation for behavioral change; and (3) referral to treatment, providing access to specialty care.10 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends pediatricians become knowledgeable about SBIRT, and 32% of pediatrics residency directors reported requiring any substance use content in their programs.11

To address training needs, SAMHSA funded 17 medical residency SBIRT training cooperatives10 with training implemented in multiple residency programs through in-person training and/or online modules. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of resident SBIRT training, including a recent study which demonstrated increases in knowledge and skills for internal medicine residents.12 Significant time constraints in residency education make the addition of new content challenging for program directors; many have addressed this challenge by implementing computer-based training.13 There are limited studies comparing online to in-person residency training in medical education literature. Findings support equal or slightly better performance in learners trained online than that in peers with face-to-face instruction.14,15 Evidence of the efficacy of online training in SBIRT could allow broader curriculum implementation. To date, no studies have compared the 2 approaches in a SBIRT curriculum. We compared online versus in-person training for SBIRT to determine whether the type of training impacts pediatrics residents' knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and skills in implementing SBIRT, as assessed by pre- and posttraining standardized patient (SP) interactions.

Methods

Pediatrics residents at the University of Maryland Medical Center received SBIRT training as part of a SAMHSA-funded program. Training competencies were developed using motivational interviewing principles and SAMHSA guidelines.11,16 Pediatric-specific information was consistent with the AAP's “Substance Abuse SBIRT for Pediatricians” policy statement.2

Measures

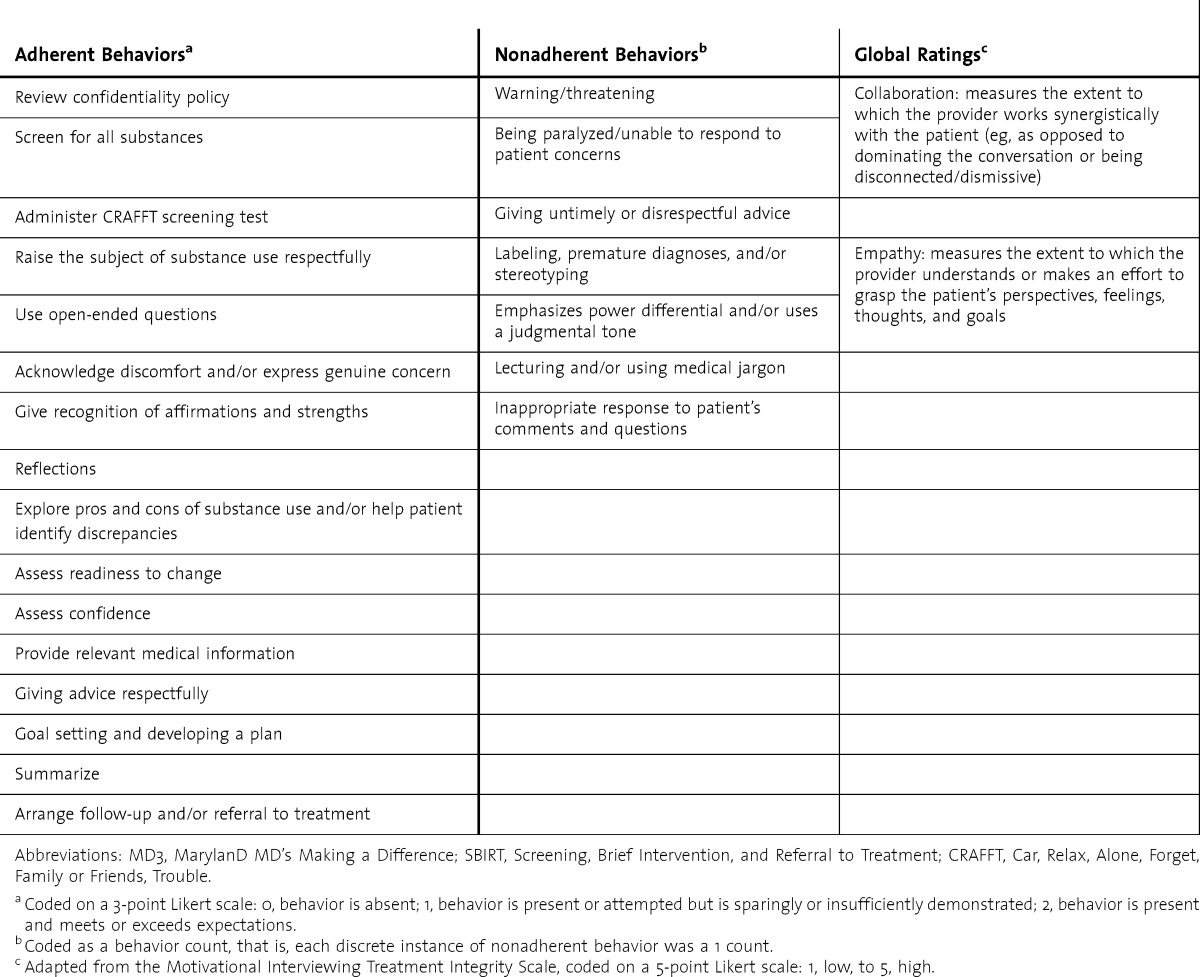

SBIRT skills were evaluated during taped interactions with SPs' pre- and posttraining. Tapes were coded using the MarylanD MD's Making a Difference (MD3) SBIRT coding scale,17 adapted for use with adolescent patients and used to evaluate 16 SBIRT-adherent (“desirable”) behaviors, 7 SBIRT-nonadherent (“undesirable”) behaviors, and 2 global skills (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Skills Assessed With the Adapted MD3 SBIRT Coding Scale

Residents completed self-reported knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (KAB) questionnaires before and after training. The knowledge portion included 6 multiple-choice questions addressing SBIRT facts. The attitudes section consisted of 24 questions addressing substance use beliefs,18,19 and the behaviors portion included 20 questions addressing the frequency with which residents performed substance use–related aspects of patient care for each substance type, using a 5-point Likert scale. The KAB also included 9 questions assessing confidence to perform SBIRT activities and 2 questions assessing readiness to screen and provide brief interventions, both using an 11-point Likert scale.

Procedures

All residents completed SP interviews pre- and posttraining within 3 weeks after SBIRT training. Immediately prior to the pretraining interview, residents completed a KAB questionnaire. Residents were then instructed to conduct the SBIRT protocol with a teenage SP who reported drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes. Four teenagers were trained as SPs with identical patient information. All SP interactions lasted 10 minutes and were videotaped.

After the first SP interview, residents were assigned to either in-person or online training. Condition assignments were partially based on practical (ie, scheduling) factors and were not truly random. However, training assignment was not associated with any specific resident characteristics, level of experience, or other variables.

Posttraining SP interviews were conducted within 3 weeks following training and involved the same case. The posttraining KAB questionnaire was e-mailed to residents in both training groups 6 to 8 months posttraining to capture longer term changes in knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported behaviors.

Training Conditions

Online

After the pretraining SP interaction, residents in the online condition were sent instructions by e-mail for completing 5 online modules consisting of voice-narrated slideshow presentations, with a total run time of 120 minutes. Modules were developed by project leaders with expertise in SBIRT, were tailored to pediatrics,20,21 and included case examples, videos, and links to additional resources (www.sbirt.umaryland.edu). Module completion was confirmed via mandatory 3-question assessments. All residents completed all 5 modules.

In-Person

Residents in the in-person group attended a 2-hour training session. The content was the same as online training but was delivered as a lecture by MD- and PhD-level trainers. Two example videos were shown, and residents completed role play exercises in pairs with instructor feedback.

Coding SP Tapes

Two graduate students with MD3 SBIRT coding scale experience independently coded the 40 pre- and 40 postresident SP interactions. A random sample of 16 tapes was independently coded by both coders to assess interrater reliability using a 2-way random model intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), estimated separately for adherent behaviors, nonadherent behaviors, and global ratings. Coders were blinded to whether a tape was pre- or posttraining and which tapes were double-coded. Only audio was used in coding, following previously described procedures.22

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0 software (IBM Corp). Two-way repeated measures multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were estimated to assess for differences in SP skill acquisition between training groups and over time. Dependent variables were adherent and nonadherent behaviors in 1 pair of analyses and global ratings of collaboration and empathy in another. If analyses indicated significant pre/post changes, univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were estimated to determine which dependent variable(s) differences emerged. In addition, a series of 2-way repeated measures ANOVAs were estimated to assess for differences in KAB variables between training groups and over time (within-subject and pre versus post).

Results

Forty-two pediatrics residents received SBIRT training; 2 did not complete SP interviews and were excluded from analyses. There were 16 (40%) postgraduate year (PGY)-1s, 14 (35%) PGY-2s, and 10 (25%) PGY-3s distributed across the 18 residents in the online group and 22 in the in-person group. There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 training conditions on demographic variables.

SBIRT Skills

Interrater reliability for the 16 double-coded tapes was in the “excellent” range,23 with ICC values of 0.95 for adherent behaviors, 0.96 for nonadherent behaviors, and 0.84 for global ratings. Distribution of the SP skills data was not significantly different from a normal distribution according to a Shapiro-Wilk test (P > .05).

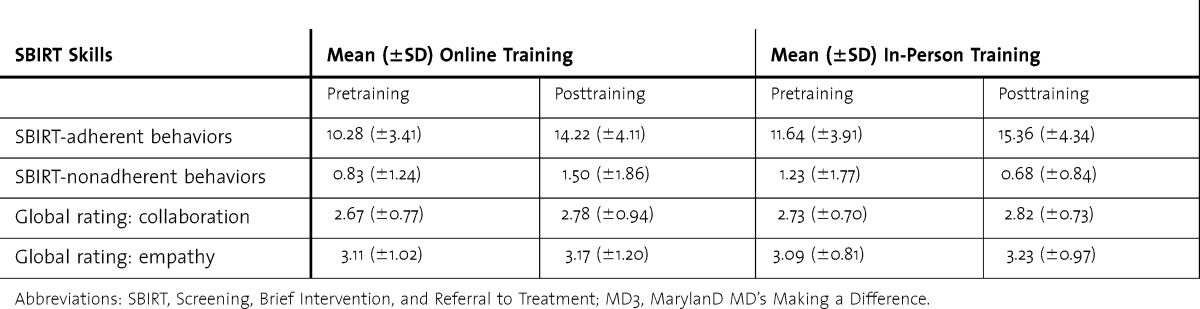

Means and standard deviations of SBIRT skills are presented in table 2. There were no statistically significant differences between SBIRT skills in the randomized groups prior to training.

TABLE 2.

SBIRT Skill Rating on the MD3 SBIRT Coding Scale Pre- and Posttraining

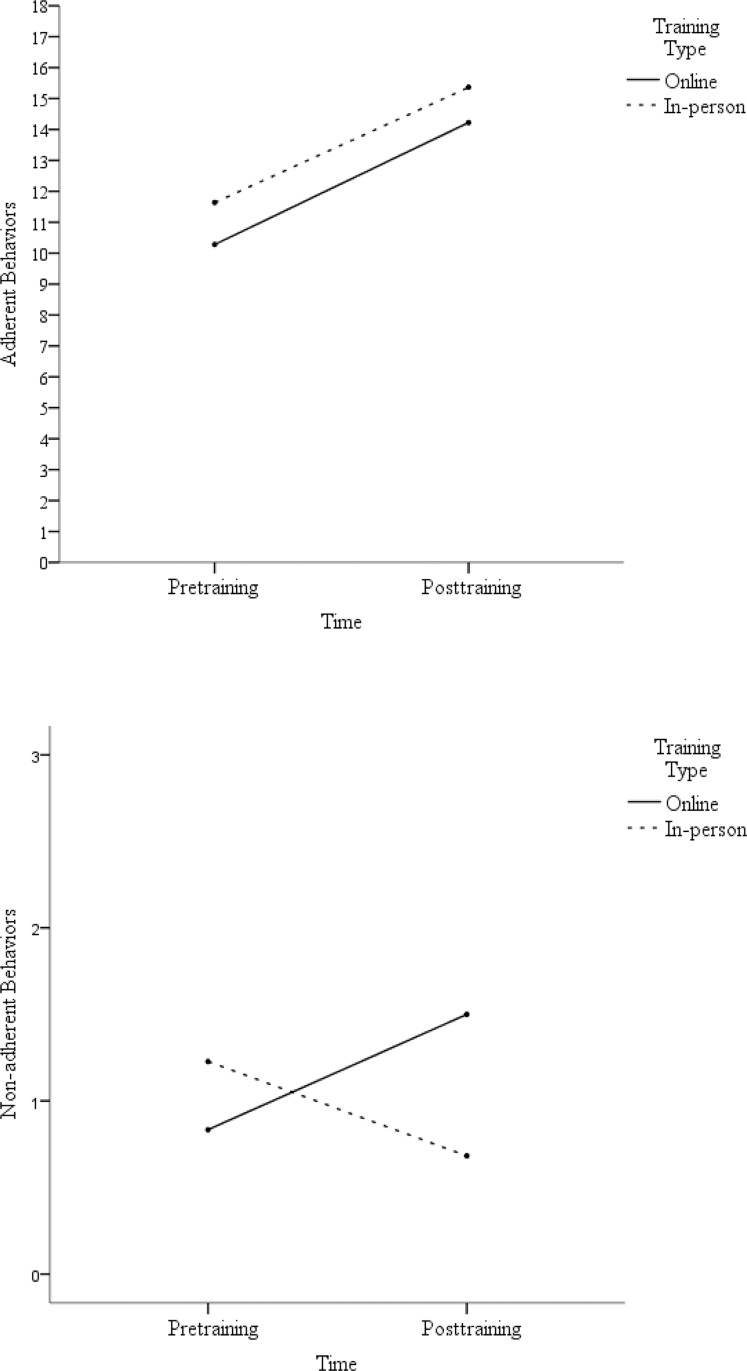

There were no differences between groups in adherent versus nonadherent behaviors before or after training, but both groups showed significant improvement from pre- to posttraining (P < .001). Both groups increased their adherent skills from pre- to posttraining (F1,38 = 32.98, P < .001) and did not differ by training type (f i g u r e). Nonadherent behaviors changed from pre- to posttraining. This change differed by training type (F1,38 = 4.87, P < .05), with the online group displaying more nonadherent behaviors posttraining (mean = 1.50, SD = 1.86) than the in-person group (mean = 0.68, SD = 0.84) (f i g u r e ). The largest increase in nonadherent behaviors among the online group was for “lecturing and/or using medical jargon,” with 17% (3 of 18) of residents displaying this behavior in pretraining, compared to 39% (7 of 18) of residents in posttraining. Although the online group displayed fewer nonadherent behaviors pretraining, this difference was not statistically significant (table 2).

FIGURE.

Change in SBIRT-Adherent and -Nonadherent Behaviors Displayed During SP Interactions Pre- and Posttraining by Training Type

Abbreviations: SBIRT, Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment; SP, standardized patient.

There were no significant differences in global ratings (P > .05), levels of collaboration, or empathy displayed during SP interviews, either between training groups or from pre- to posttraining.

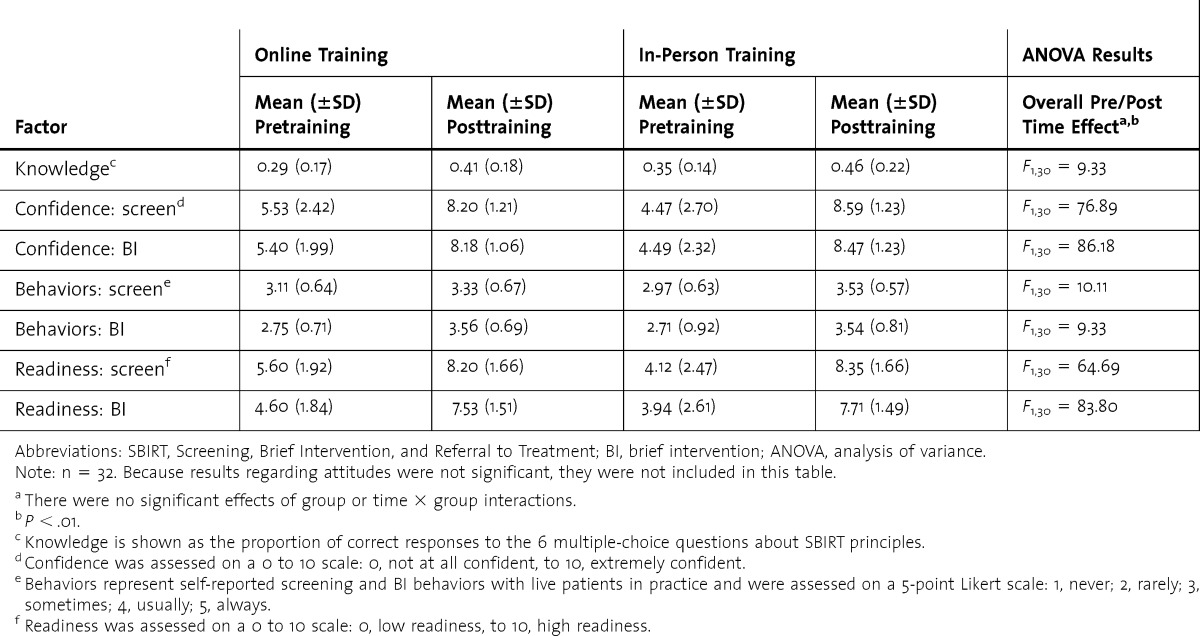

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors

A subsample of 32 residents completed both pre- and post-KAB surveys (15 in the online training group, 17 in the in-person training group, and 8 were omitted due to noncompletion of post-KAB survey). There were no significant differences between the 32 residents with complete data and the 8 residents without a postassessment on any preassessment measure, training assignment, pre- or post-SP ratings, or demographic variable, except that noncompleters were more likely to be men (38% versus 10%, P < .05).

There were no significant differences between any KAB variables pretraining for either group (table 3). For knowledge, self-reported behaviors, confidence, and readiness, findings indicated that both groups changed from pre- to posttraining but did not differ by group. For attitudes, there were no significant differences either between training groups or from pre- to posttraining.

TABLE 3.

Changes From Pre- to Posttraining in Residents' SBIRT Knowledge, SBIRT Confidence, Current Self-Reported Screening, BI Behaviors, and Self-Reported Readiness to Screen and Do BIs

Discussion

In this study, both in-person and online SBIRT training effectively increased pediatrics residents' SBIRT skills, knowledge, self-reported behaviors, confidence, and readiness. Further investigation, however, revealed a nuanced interaction of training type and time for undesirable behaviors; the online training group showed a slight increase whereas the in-person training group showed a reduction. This suggests that in-person training may be superior to online training in teaching residents what not to do. The reasons for this discrepancy are not clear, but it might be attributable to the role play, practice, and feedback that the in-person group received, which contributed to greater confidence or a stronger grasp of SBIRT goals.

Additionally, although specific SBIRT skills increased, neither group demonstrated a change in global ratings of collaboration or empathy, suggesting training did not impact overall communication style. This is not surprising given the brevity of the training, and is consistent with previous studies.24,25

Another finding was that neither group's attitudes about substance use treatment changed from pre- to posttraining. This is likely due to the focus on skill acquisition rather than attitude change. It also is possible that there was a brief change in attitudes that was not sustained over 6 months.

This study has several limitations. We did not include a no-training control group that would have allowed us to rule out changes contributable to time only. Another limitation was the use of identical SP cases in pre- and postassessments, which could have contributed to practice effects. We did not perform a power calculation to determine the minimum number of subjects needed per group. The small sample size and single institution cohort raise questions about the generalizability of the findings. Finally, our study did not evaluate actual resident performance, and there is evidence to show that increased confidence does lead to improved clinical performance.26

Conclusion

Pediatrics residents' SBIRT skills, knowledge, self-reported behaviors, and perceived confidence and readiness can be improved through both in-person and online training. Online training is feasible and does not require designated training space or teachers. There may be a benefit to in-person training in minimizing undesirable behaviors. Future research should explore the utility of online and in-person training to maximize SBIRT implementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Katherine Earley for her instrumental support on the MD3 project, and Emily Foxen-Craft for coding assistance.

Footnotes

Erin L. Giudice, MD, is Assistant Professor and Pediatric Residency Program Director, Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland School of Medicine; Linda O. Lewin, MD, is Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland School of Medicine; Christopher Welsh, MD, is Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine; Taylor Berens Crouch, MA, is a Doctoral Candidate, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland Baltimore County; Katherine S.Wright, MA, is a Doctoral Candidate, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland Baltimore County; Janine Delahanty, PhD, is Research Scientist, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland Baltimore County; and Carlo C. DiClemente, PhD, ABPP, is Presidential Research Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland Baltimore County.

Funding: This work was funded by Medical Residency Cooperative Agreement training grant 1U79T1020257-01 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment: What is SBIRT. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy S Kokotailo P; Committee on Substance Abuse. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1330–1340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke H, Leonardi-Bee J, Hashim A, Pine-Abata H, Chen Y, McKeever T, et al. Prenatal and passive smoke exposure and incidence of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):735–744. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. Helping families thrive: key policies to promote tobacco-free environments for families, March 2009. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. http://tobacco-cessation.org/sf/pdfs/pub/Final%20Final%20Indicator%20with%20all%20edits%203-30-09.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hum AM, Robinson LA, Jackson AA, Ali KS. Physician communication regarding smoking and adolescent tobacco use. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):e1368–e1374. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson CR, Sherritt L, Gates E, Knight JR. Are clinical impressions of adolescent substance use accurate. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e536–e540. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpern-Felsher BL, Ozer EM, Millstein SG, Wibbelsman CJ, Fuster CD, Elster AB, et al. Preventive services in a health maintenance organization: how well do pediatricians screen and educate adolescent patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(2):173–179. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elwy A, Horton N, Saitz R. Physicians' attitudes toward unhealthy alcohol use and self-efficacy for screening and counseling as predictors of their counseling and primary care patients' drinking outcomes. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013;8(1):8–17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. White Paper: Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral To Treatment (SBIRT) In Behavioral Healthcare. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 2011. http://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sbirtwhitepaper_0.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaacson JH, Fleming M, Kraus M, Kahn R, Mundt M. A national survey of training in substance use disorders in residency programs. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(6):912–915. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satterfield J, O'Sullivan P, Satre D, Tsoh JY, Batki SL, McCance-Katz EF, et al. Using standardized patients to evaluate SBIRT knowledge and skill acquisition for internal medicine residents. Subst Abuse. 2012;33(3):303–307. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.640103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drolet B, Whittle S, Khokhar M, Fischer S, Pallant A. Approval and perceived impact of duty hour regulations: survey of pediatric program directors. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):819–824. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Means B, Toyama Y, Murphy R, Bakia M, Jones K. Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies. Washington DC: US Department of Education; 2010. Center for Technology in Learning. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis J, Chryssafidou E, Zamora J, Davies D, Khan K, Coomarasamy A. Computer-based teaching is as good as face to face lecture-based teaching of evidence based medicine: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiClemente CC, Crouch TB, Norwood AE, Delahanty J, Welsh C. Evaluating training of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) for substance use: reliability of the MD3 SBIRT coding scale. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014 Nov 17 doi: 10.1037/adb0000022. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chappel JN, Veach TL, Krug RS. The Substance Abuse Attitude Survey: an instrument for measuring attitudes. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46(1):48–52. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorman DM, Cartwright AK. Implications of using the composite and short versions of the Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception questionnaire (AAPPQ) Br J Addict. 1991;86(3):327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47(9):1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moyers T, Miller WR, Hendrickson SM. How does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):590–598. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Special section: normative assessment. Psych Assess. 1994;6(4):284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evangeli M, Engelbrecht S, Swartz L, Turner K, Forsberg L, Soka N. An evaluation of a brief motivational interviewing training course for HIV/AIDS counsellors in Western Cape Province, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):189–196. doi: 10.1080/09540120802002471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansink R, Braspenning J, Laurant M, Keizer E, Elwyn G, Weijden Tv, et al. Minimal improvement of nurses' motivational interviewing skills in routine diabetes care one year after training: a cluster randomized trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):44–52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers LQ, Bailey JE, Gutin B, Johnson KC, Levine MA, Milan F, et al. Teaching resident physicians to provide exercise counseling: a needs assessment. Acad Med. 2002;77(8):841–844. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200208000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]