Abstract

Plant salt glands are nature’s desalination devices that harbour potentially useful information pertaining to salt and water transport during secretion. As part of the program toward deciphering secretion mechanisms in salt glands, we used shotgun proteomics to compare the protein profiles of salt gland-enriched (isolated epidermal peels) and salt gland-deprived (mesophyll) tissues of the mangrove species Avicennia officinalis. The purpose of the work is to identify proteins that are present in the salt gland-enriched tissues. An average of 2189 and 977 proteins were identified from the epidermal peel and mesophyll tissues, respectively. Among these, 2188 proteins were identified in salt gland-enriched tissues and a total of 1032 selected proteins were categorized by Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. This paper reports for the first time the proteomic analysis of salt gland-enriched tissues of a mangrove tree species. Candidate proteins that may play a role in the desalination process of the mangrove salt glands and their potential localization were identified. Information obtained from this study paves the way for future proteomic research aiming at elucidating the molecular mechanism underlying secretion in plant salt glands. The data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD000771.

Introduction

Plants growing in saline environment have to cope with the constant exposure to high levels of salt and limited availability of freshwater. In some halophytic plant species (i.e., plants that are able to tolerate salt concentrations as high as 500–1000mM), there exists specialized microscopic structures located predominantly on the leaves and stems that are able to remove salts from the internal tissues and deposit them on the leaf surfaces [1,2]. Known as the salt glands, they are nature’s desalination devices offering alternative routes for excess ion elimination through secretion, an adaptive feature that favours species inhabiting saline environment. Many of the salt gland studies focused on their secretory nature (e.g., [3–8]). The mechanism underlying such a desalination process, however, remains unclear.

Previous studies by us [9,10] focused on the salt glands of a commonly found mangrove tree species in Singapore (Avicennia officinalis L) [11,12]. By making use of an epidermal system developed, we discovered a unique secretory pattern [10] that had been considered as an example of high resolution measurements of secretions that may lead to a general understanding on the mechanism of fluid secretion in both plant and animal systems [13]. This species grows in intertidal zones and has to cope with periodic exposure to fluctuating salinities [14]. We hypothesize that salt glands function as salt and water bi-regulatory units and the salt glands of this species offer an excellent platform to investigate their dynamic responses and molecular underpinnings to fluctuating salinities. Modern high throughput proteomics tools allow more detailed quantitative information, both temporal and spatial expression of proteins, to be obtained [15]. Recent studies in search of salt-responsive proteins in mangroves have also adopted a proteomic approach [16–18]. These studies, however, focused on the non-secretors (i.e., Bruguiera gymnorhiza, Kandelia candel) that do not have salt glands on their epidermal surfaces. Due to technical challenges faced in obtaining proteins directly from salt glands, a recent proteomic paper published by our group [19] focused on the plasma membrane and tonoplast proteins extracted from the leaves of A. officinalis. All these studies reported thus far have adopted a gel-based analysis approach.

In this study, as a continuous effort to better understand how water and salt are transported via the salt glands, we have adopted a shotgun approach to look into the proteome of salt-gland enriched tissues of the mangrove tree species A. officinalis. By removing the bulk of the leaf tissues (i.e., mesophyll tissues) devoid of salt glands, proteins from tissues that are rich in salt glands could be successfully obtained. To compensate for the technical limitations in obtaining large amounts of proteins from salt-gland-rich tissues, the shotgun approach adopted in this study allows simplified handling of samples with more exhaustive digestion and avoidance of sample loss in the gel matrix [20]. The data obtained via this approach offers a glimpse into the proteome of salt gland-rich materials and serves as a platform for identifying pool of proteins that could be involved in the desalination process of the mangrove salt glands.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and protein extraction

The leaves of A. officinalis were required for the isolation of salt gland-enriched tissues (i.e., adaxial epidermal peels) for subsequent protein extractions. Shoots of A. officinalis were first collected from the mangrove swamp at Berlayer Creek (Sungei Berlayer, Labrador, Singapore; 1.27°N; 103.80°E; permit for collection granted by Keppel Club, Singapore). For each biological replicate, the adaxial epidermal peels, which harbour the salt glands, were separated from the mesophyll tissues of ~20 leaves collected from several shoots according to Tan et al. [9]. Briefly, abaxial epidermal layers of excised leaves were removed, the leaves cut into segments before the leaf strips floated on enzyme mixture (pH 5.7; filter-sterilized) containing 0.1% (w/v) Pectolyase Y-23 (Seishin Pharmaceutical, Japan), 1.0% (w/v) Driselase (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 1.0% (w/v) Cellulase Y-C (Kikkoman Corporation, Japan) were vacuum infiltrated for 10 min and incubated in the dark at 30°C, 30 rpm for 1 h. The adaxial epidermal peels were easily detached from the mesophyll tissues after enzyme treatment. These peels were then rinsed, the remnants of mesophyll-palisade layers gently scraped off using a scalpel to obtain adaxial peels devoid of chlorophyll-containing cells and were collected separately from the mesophyll tissues. Three biological replicates were prepared. Total protein was extracted separately from these tissues by grinding them in liquid nitrogen and resuspending in buffer containing 25mM triethylammonium bicarbonate, 8M urea, 2% Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate [21]. The samples were then sonicated on ice for 30min, centrifuged (16000×g) at 15°C for 1h before supernatants were collected. Proteins were estimated using RCDC Protein Assay Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) to compensate for interfering compounds in the samples.

Sample preparation and LC-MS/MS analysis

Each sample (300μg) was reduced by 5mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for 1h and alkylated with 10mM methyl methanethiosulfonate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for 10min. The samples were then trypsin-digested (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) overnight at 37°C in a trypsin-to-protein ratio of 1:20 (W:W).

The first dimension peptide separation, which included removal of SDS and other contaminants, was carried out on a LC-10A1 Prominence Modular HPLC (Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). The digested sample (100μg) was diluted with 5ml strong cation-exchange mobile phase A [10mM potassium phosphate in 25% acetonitrile (ACN), pH 3.0] before solution was passed through a 3μm PolySULFOETHYL A column (35mm × 4.6mm; PolyLC Inc., Columbia, MD). Peptides were separated by gradient formed by mobile phase A and B (500mM KCl and 10mM potassium phosphate in 25% ACN, pH 3.0),: 0–0% mobile phase A in 10min, 0–36% mobile phase B in 80min, 36–70% mobile phase B in 30min, 70–100% mobile phase B in 1min, 100–100% mobile phase B in 10min and 0–0% mobile phase B in 10min, each at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The digested peptides (100μg) separated were combined to 8 fractions (~12.5μg proteins/fraction), desalted with Sep-Pak Classic C18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), lyophilized before a second-dimension reversed-phase (RP) chromatography was carried out on Eksigent nanoLC Ultra and ChiPLC-nanoflex (Eksigent, Dublin, CA, USA).

Desalted samples were reconstituted with 15μl diluent [2% ACN, 0.05% formic acid (FA)], 5μl of which was loaded on 200μm × 0.5mm trap column and eluted onto analytical 75μm × 150mm column. Both columns were made of Repro-Sil-Pur C18-AQ, 3μm (Eksigent, Dr. Maisch, Germany). Peptides were separated by gradient formed by mobile phase A (2% ACN, 0.1% FA) and B (98% ACN, 0.1% FA): 5–12% mobile phase B in 20min, 12–30% mobile phase B in 40min, 30–90% mobile phase B in 2min, each at a flow rate of 300nl/min. The MS analysis was performed on TripleTOF 5600 system (AB SCIEX, Foster City, CA, USA) in Information Dependent Mode. MS spectra were acquired across mass range of 400–1800m/z in high resolution mode (> 30000) using 250ms accumulation time/spectrum. A maximum of 20 precursors/cycle was chosen for fragmentation from each MS spectrum with 100ms minimum accumulation time for each precursor and dynamic exclusion for 15s. Tandem mass spectra were recorded in high sensitivity mode (resolution > 15000) with rolling collision energy on.

Peptide identification and quantification was performed with ProteinPilot 4.5 software Revision 1656 (AB SCIEX) using the Paragon database search algorithm (4.5.0.0) and integrated false discovery rate (FDR) analysis function. The obtained MS/MS spectra were then searched against a database created [i.e., derived from transcriptome sequencing of salt gland–enriched tissues (i.e., adaxial epidermal peels of A. officinalis, with a total 174552 entries including both normal and decoy sequences)]. The following search parameters were adopted: Sample Type—Identification; Cys Alkylation—MMTS; Digestion—trypsin; Special Factors—None; Species—None. The processing was specified as follows: ID Focus—Biological Modifications; Search Effort—Thorough; Detected Protein Threshold—0.05 (10.0%). Identified proteins for each biological replicate were selected based on a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 1%.

For Gene Ontology (GO) studies [22], proteins identified in the salt gland-enriched tissues and that are present in at least two of the biological replicates were selected for further analysis. These selected proteins were first submitted to the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) website (http://www.uniprot.org/help/uniprotkb) to retrieve the corresponding UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot entries and only annotated entities (i.e., with matched Swiss-Prot ID) were consolidated for GO analysis.

Results

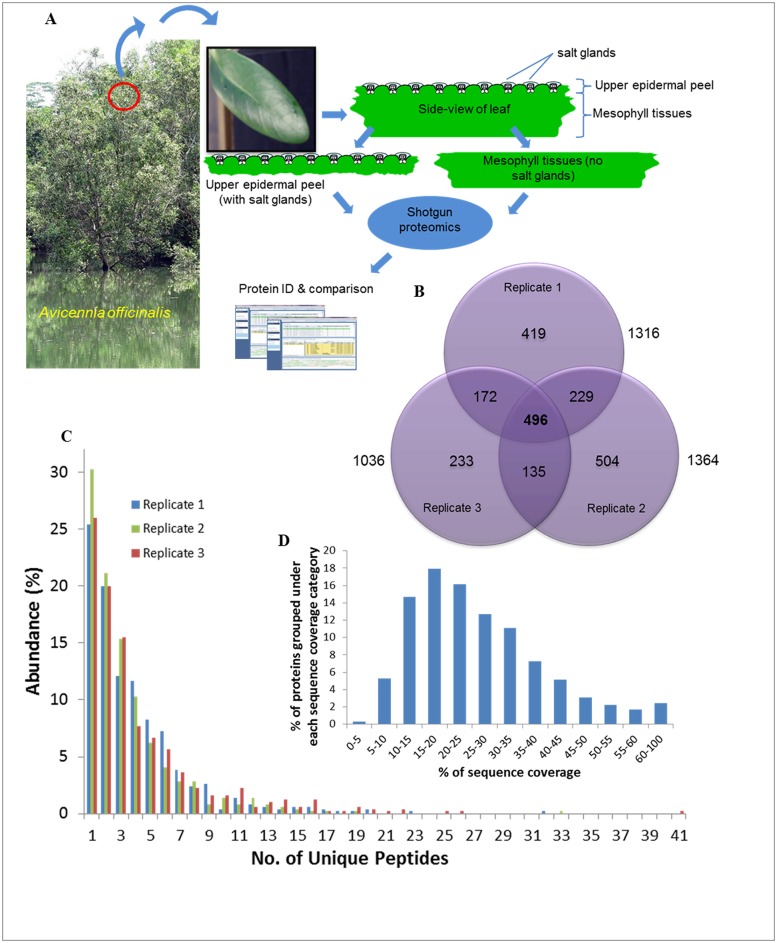

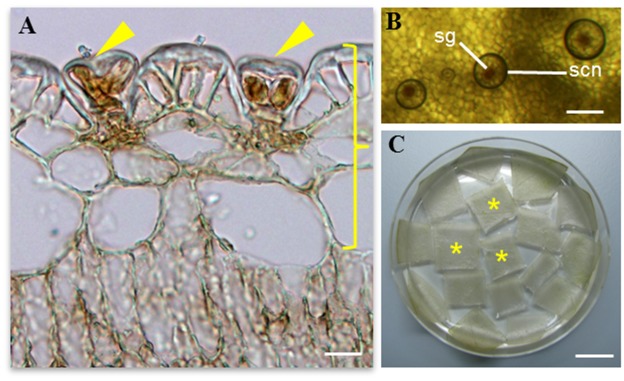

The salt glands of Avicennia officinalis are microscopic (20–40 μm) structures found on the epidermal leaf surfaces (Fig 1A). They can secrete droplets of salt solutions, which appear circular in shape above the salt glands under a layer of oil when the adaxial (upper) epidermal peel (which harbours the salt glands) was viewed from the top (Fig 1B). These adaxial epidermal peels that are enriched with salt glands (Fig 1C) thus serve as good starting materials for the study of the salt gland proteome. To achieve this, proteins from both the adaxial epidermal peels (salt gland-enriched) and mesophyll tissues (salt gland-deprived) were extracted and compared (Fig 2A). For each extraction, approximately 2 mg proteins/g tissues and 9 mg proteins/g tissues were obtained from the epidermal peels and mesophyll tissues, respectively. A 2DLC/MS/MS analysis was performed on each of the trypsin-digested samples and identified proteins for each biological replicate were selected (< 1% FDR; S1–S6 Tables). An average of 2189 ± 128 (Table 1 and S1–S3 Tables) and 977 ± 150 (Table 1 and S4–S6 Tables) proteins were observed from the epidermal peels and mesophyll tissues, respectively. To obtain a list of proteins from salt gland-enriched tissues, only proteins that are found in epidermal peels but not in mesophyll tissues were considered. Data were sorted using nwCompare [23], with proteins found in any biological replicates for each tissue type taken into consideration and those extracted from epidermal peels and can be identified from mesophyll tissues eliminated. Using this approach, 2188 proteins are identified in salt gland-enriched tissues (Fig 2B and see S7 Table). Of these, 496 proteins were commonly found in all biological replicates, 536 proteins observed in two out of three biological replicates while remaining 1156 were present in one of the biological replicates (Fig 2B). Among the 496 proteins that were commonly found in all three biological replicates analysed, more than 25% of the proteins with at least one unique peptide was identified, while ~50% of the proteins with 2–5 unique peptides and the rest with at least 6 unique peptides identified (Fig 2C). By looking at the distribution of protein sequence coverage, more than 65% of the proteins identified showed a sequence coverage of 15–40% (Fig 2D).

Fig 1. Salt glands of the mangrove species Avicennia officinalis.

(A) Transverse section of leaf showing the adaxial (upper) epidermal layer with two salt glands (arrows). (B) Secretion (scn) above the salt gland (sg) can be observed from the top view of the adaxial epidermal layer. (C) The salt gland-enriched epidermal peels (*) as indicated by the right brace in (A) were obtained from the leaves for subsequent protein extraction and downstream proteomic analysis. Scale bars: 20μm (A), 100μm (B), 1cm (C).

Fig 2. Identification and analysis of salt gland-enriched proteome.

(A) The experimental approach for generation of a salt gland-enriched proteome through the use of two distinct set of samples: total proteins from the adaxial (upper) epidermal peels (with salt glands) and from the mesophyll tissues (no salt glands). (B) The number of proteins that are identified in salt gland-enriched epidermal peels from three biological replicates is presented in the Venn diagram. Identified proteins from the salt gland-enriched tissues that were present in all the three biological replicates were grouped according to the number of unique peptides (C) and % sequence coverage (D). The identified proteins (D) were classified according to the protein’s sequence coverage.

Table 1. Number of proteins identified from adaxial (upper) epidermal peels and mesophyll tissues of the leaves of A. officinalis.

| Average no. of proteins identified (±SE) | |

|---|---|

| Epidermal peels | 2189 ± 128 |

| Mesophyll tissues | 977 ± 150 |

Three biological replicates from each type of tissues were prepared and the protein profiles compared using a shotgun approach. Results are presented as mean ± SE.

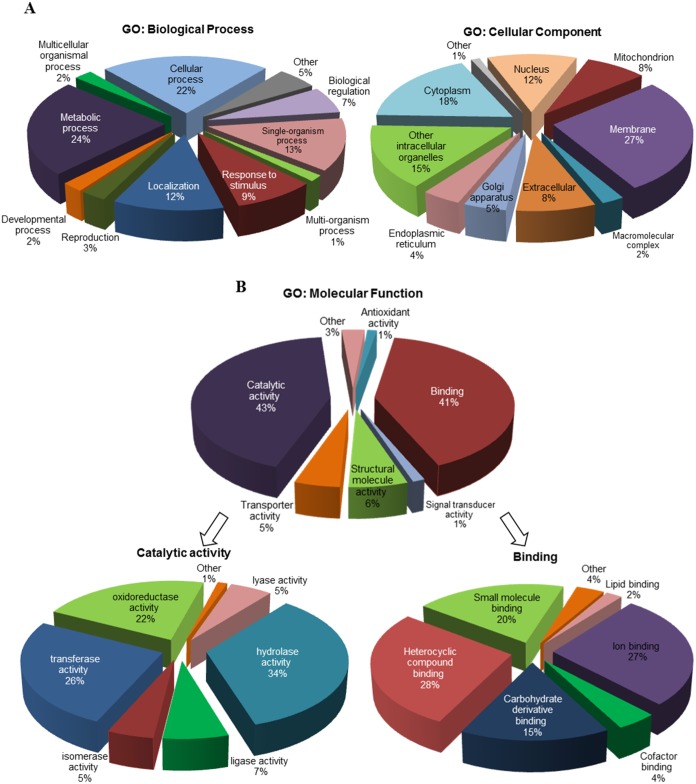

To better understand the functions of proteins identified in salt gland-enriched tissues, proteins that are present in at least two of the biological replicates were selected from the list of 2188 proteins for GO analysis [22]. A total of 1032 selected proteins (see S8 Table) were analysed and information were retrieved from the UniProt Knowledgebase website (http://www.uniprot.org/help/uniprotkb). The proteins were annotated based on three organizing principles of GO (Fig 3). They were characterised by their function in diverse biological processes, with 11 sub-categories identified (Fig 3A). Majority of these proteins were predicted to participate in metabolic (24%), cellular (22%) or single-organism (13%) processes or were responding to stimulus (9%), if not involved in localization (12%) (Fig 3A).

Fig 3. GO annotation of proteins identified in salt gland-enriched tissues of A. officinalis.

A total of 1032 proteins were analysed. The proteins were classified based on GO for (A) biological process, cellular component and (B) molecular function. The major subcategories of molecular function (B) are shown in more detail on the left and right sides below the corresponding subcategories.

Cellular component analysis showed proteins analysed belong to 10 cellular compartments (Fig 3A). More than 70% of them were identified to be localized in membranes (27%), cytoplasm (18%), intracellular organelles (15%) or nuclei (12%) while 8% of them are extracellular proteins. For molecular function classification, 592 proteins had been assigned with 873 GO terms and seven sub-categories were identified (Fig 3B). Among them, catalytic activity (43%) and binding (41%) were the most abundant functions. Seven sub-categories were identified for proteins with catalytic activity, with majority of them (> 80%) involved in hydrolase (34%), transferase (26%) and oxidoreductase (22%) activities. For binding proteins, most were involved in heterocyclic compound (28%), ion (27%), small molecule (20%) and carbohydrate derivative (15%) binding.

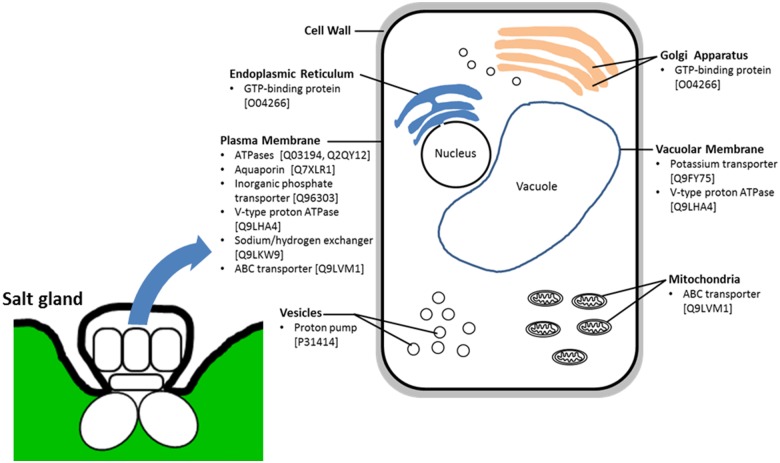

Among the list of proteins, many heat shock proteins (HSPs) or proteins related to carbohydrate and energy metabolism (e.g., ATPases, ATP synthases, aconitate hydratases, GTP-binding proteins) were identified (Table 2 and S8 Table). Proteins (Table 2). Membrane proteins such as aquaporins, transporters/exchangers, channels and pumps were also observed in the salt gland-rich tissues (Table 2). Kinases, leucine-rich repeat proteins, 14-3-3-like protein and calreticulin commonly involved in signal transduction pathways had also been identified in this study (Table 2 and S8 Table). Candidate proteins that are of interest to us pertaining to the secretory process of salt glands include ATPases (e.g., Swissprot ID: Q03194, Q2QY12), transporters (e.g., Swissprot ID: Q96303, Q9LKW9, Q9LVM1 Q9FY75), aquaporins (e.g., Swissprot ID: Q7XLR1) and GTP-binding proteins (e.g., Swissprot ID: O04266). Based on GO analysis, most of these proteins were predicted to be localized to the plasma membrane while some were expected to be found in the tonoplast, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus or endoplasmic reticulum (Fig 4).

Table 2. Selected list of proteins identified from salt gland-enriched epidermal tissues of A. officinalis.

These proteins are identified in the epidermal tissues but not in the mesophyll tissues of A. officinalis and only those that are present in two out of the three biological replicates are selected for further anlaysis. The full list of proteins is presented in S8 Table.

| Unused ProtScore* | % Coverage # | Peptides (95%) ^ | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | gi Acession No. | Swiss-Prot ID | Contig No. | T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | Protein Description | Species |

| 1 | gi|3912949 | O49996 | CL15843.Contig3_All | 2.27 | 8.00 | 12.21 | 42.90 | 34.30 | 52.70 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 14-3-3-like protein D | Nicotiana tabacum |

| 2 | gi|224136700 | Q9LT08 | CL5021.Contig4_All | 7.70 | 3.95 | 4.36 | 32.10 | 33.00 | 22.10 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 14 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 3 | gi|3914467 | P93768 | Unigene16875_All | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.36 | 30.30 | 30.30 | 30.30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 3 | Nicotiana tabacum |

| 4 | gi|350538091 | O04059 | CL2261.Contig1_All | 7.52 | 11.08 | 6.18 | 22.30 | 19.20 | 20.80 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone kinase | Solanum lycopersicum |

| 5 | gi|255584390 | Q9LVM1 | CL12689.Contig2_All | 0.91 | 2.66 | 2.00 | 8.90 | 13.80 | 15.40 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ABC transporter B family member 25 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 6 | gi|255552969 | Q9M1H3 | Unigene32800_All | 4.88 | 5.62 | 2.01 | 18.40 | 17.60 | 18.20 | 4 | 3 | 1 | ABC transporter F family member 4 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 7 | gi|296090419 | Q7PC87 | CL4209.Contig1_All | 4.00 | 2.01 | 21.16 | 44.40 | 46.80 | 53.60 | 8 | 10 | 13 | ABC transporter G family member 34 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 8 | gi|359484370 | Q8RXE7 | Unigene4379_All | 4.83 | 2.00 | 2.18 | 19.20 | 15.10 | 13.60 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein AGD14 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 9 | gi|255546541 | Q56YU0 | CL13289.Contig1_All | 3.08 | 4.09 | 6.02 | 21.10 | 25.90 | 19.70 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 2 member C4 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 10 | gi|297823651 | Q0PGJ6 | CL5791.Contig3_All | 4.87 | 8.40 | 9.74 | 39.20 | 47.70 | 52.30 | 6 | 7 | 7 | Aldo-keto reductase family 4 member C9 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 11 | gi|50345961 | Q7XSQ9 | CL16514.Contig4_All | 4.00 | 4.01 | 6.03 | 39.50 | 43.00 | 36.00 | 12 | 12 | 22 | Aquaporin PIP1-2 | Oryza sativa subsp. japonica |

| 12 | gi|17940742 | Q7XLR1 | Unigene32737_All | 4.00 | 2.09 | 2.00 | 29.60 | 33.70 | 27.60 | 7 | 5 | 4 | Aquaporin PIP2-6 | Oryza sativa subsp. japonica |

| 13 | gi|255541428 | CL8427.Contig3_All | 4.09 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 16.40 | 11.60 | 6.20 | 4 | 2 | 1 | Arsenical pump-driving atpase | Ricinus communis | |

| 14 | gi|2493046 | Q40089 | CL7437.Contig2_All | 6.89 | 5.65 | 12.70 | 26.10 | 46.80 | 53.70 | 4 | 5 | 9 | ATP synthase subunit delta' | Ipomoea batatas |

| 15 | gi|225454791 | Unigene6969_All | 3.38 | 4.00 | 1.54 | 47.10 | 40.20 | 14.90 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3-B | Vitis vinifera | |

| 16 | gi|224145672 | P28583 | CL274.Contig2_All | 2.39 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 15.50 | 22.00 | 17.40 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Calcium-dependent protein kinase SK5 | Glycine max |

| 17 | gi|225466204 | Q9CAL3 | CL14803.Contig3_All | 4.96 | 4.87 | 8.92 | 18.60 | 22.90 | 23.10 | 3 | 3 | 5 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase 2 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 18 | gi|225452304 | Q93ZC9 | Unigene4267_All | 2.33 | 3.39 | 4.71 | 12.10 | 11.20 | 34.00 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Glucuronokinase 1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 19 | gi|225445585 | CL12018.Contig2_All | 3.12 | 2.33 | 2.04 | 16.20 | 15.80 | 12.00 | 3 | 1 | 1 | GTPase-activating protein gyp7-like | Vitis vinifera | |

| 20 | gi|351721140 | O64477 | Unigene30402_All | 2.03 | 2.92 | 3.18 | 10.10 | 14.00 | 11.90 | 1 | 2 | 2 | G-type lectin S-receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At2g19130 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 21 | gi|296081939 | F4JMJ1 | CL2876.Contig1_All | 13.17 | 7.78 | 18.76 | 40.10 | 32.60 | 41.30 | 11 | 7 | 10 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 17 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 22 | gi|224099789 | Q9SKY8 | CL2714.Contig2_All | 4.14 | 2.01 | 2.44 | 17.60 | 4.20 | 9.10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 23 | gi|45331281 | P09189 | CL2270.Contig3_All | 6.03 | 4.34 | 8.12 | 56.00 | 52.10 | 59.00 | 32 | 33 | 41 | Heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein | Petunia hybrida |

| 24 | gi|240255879 | CL2610.Contig2_All | 4.06 | 4.00 | 6.00 | 44.80 | 44.80 | 63.20 | 2 | 2 | 3 | Heat shock factor binding protein | Arabidopsis thaliana | |

| 25 | gi|356540381 | Q43468 | CL13990.Contig2_All | 2.09 | 6.00 | 2.03 | 53.40 | 52.30 | 40.40 | 4 | 4 | 3 | Heat shock protein STI | Glycine max |

| 26 | gi|359473854 | Unigene32812_All | 2.14 | 2.09 | 4.00 | 28.70 | 25.30 | 14.30 | 2 | 1 | 2 | hsp70 nucleotide exchange factor FES1 | Vitis vinifera | |

| 27 | gi|297793865 | Q9FM19 | Unigene2776_All | 3.72 | 3.91 | 9.97 | 32.20 | 40.10 | 40.80 | 6 | 7 | 11 | Hypersensitive-induced response protein 1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 28 | gi|255576916 | O48788 | Unigene6256_All | 3.02 | 2.41 | 2.00 | 27.50 | 27.50 | 24.40 | 4 | 4 | 2 | Inactive receptor kinase At2g26730 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 29 | gi|2208908 | Q96303 | CL8176.Contig2_All | 12.13 | 12.15 | 4.64 | 18.10 | 17.50 | 21.40 | 9 | 8 | 7 | Inorganic phosphate transporter 1–4 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 30 | gi|357440961 | Q8GYF4 | CL8176.Contig4_All | 6.32 | 6.68 | 10.07 | 19.80 | 18.50 | 22.20 | 7 | 6 | 6 | Inorganic phosphate transporter 1–5 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 31 | gi|297740564 | C0LGE0 | CL3330.Contig3_All | 20.94 | 18.55 | 25.32 | 29.50 | 26.70 | 31.40 | 13 | 12 | 17 | LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At1g07650 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 32 | gi|224112549 | C0LGG9 | Unigene4496_All | 2.01 | 2.05 | 2.00 | 22.00 | 26.00 | 17.10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At1g53440 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 33 | gi|359485959 | C0LGH3 | CL2732.Contig3_All | 4.65 | 7.56 | 5.09 | 25.50 | 15.20 | 18.80 | 4 | 4 | 4 | LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At1g56140 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 34 | gi|359493576 | C0LGQ5 | Unigene30432_All | 6.19 | 5.03 | 11.29 | 31.70 | 27.00 | 34.60 | 5 | 4 | 7 | LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase GSO1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 35 | gi|225444063 | CL8211.Contig2_All | 12.44 | 7.93 | 11.21 | 33.80 | 29.40 | 37.30 | 7 | 4 | 8 | obg-like ATPase 1 | Vitis vinifera | |

| 36 | gi|13785471 | Q9T074 | CL2927.Contig4_All | 22.73 | 13.53 | 24.38 | 36.50 | 26.90 | 40.80 | 17 | 8 | 16 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase [ATP] | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 37 | gi|225442595 | Q66GQ3 | CL2133.Contig8_All | 9.92 | 12.24 | 17.14 | 33.00 | 34.90 | 32.50 | 5 | 8 | 11 | Protein disulfide isomerase-like 1–6 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 38 | gi|225459342 | Q69SA9 | CL4543.Contig4_All | 0.86 | 2.84 | 2.29 | 22.20 | 29.60 | 22.20 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Protein disulfide isomerase-like 5–4 | Oryza sativa subsp. japonica |

| 39 | gi|359494074 | CL2740.Contig3_All | 2.01 | 6.22 | 4.06 | 39.20 | 60.80 | 46.00 | 6 | 4 | 6 | Protein grpE-like | Vitis vinifera | |

| 40 | gi|45433315 | P31569 | CL4418.Contig4_All | 4.00 | 1.76 | 3.06 | 29.60 | 30.10 | 23.60 | 6 | 5 | 6 | Protein ycf2 | Oenothera villaricae |

| 41 | gi|357445105 | B9DFG5 | Unigene196_All | 2.00 | 6.02 | 7.52 | 22.80 | 20.10 | 41.40 | 6 | 4 | 4 | PTI1-like tyrosine-protein kinase 3 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 42 | gi|242064260 | Q06572 | CL6187.Contig3_All | 4.00 | 4.01 | 2.00 | 10.10 | 32.40 | 26.30 | 2 | 3 | 1 | Pyrophosphate-energized vacuolar membrane proton pump | Hordeum vulgare |

| 43 | gi|356526237 | P31414 | CL3527.Contig3_All | 2.01 | 2.00 | 4.35 | 11.00 | 39.70 | 37.00 | 2 | 2 | 4 | Pyrophosphate-energized vacuolar membrane proton pump 1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 44 | gi|359477316 | Q42736 | CL384.Contig14_All | 4.08 | 10.48 | 2.04 | 18.90 | 21.00 | 21.80 | 6 | 6 | 6 | Pyruvate, phosphate dikinase | Flaveria pringlei |

| 45 | gi|258678027 | Q9M651 | CL13915.Contig4_All | 1.19 | 2.01 | 2.00 | 25.60 | 31.80 | 18.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | RAN GTPase-activating protein 2 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 46 | gi|7672732 | P43298 | CL15187.Contig2_All | 3.87 | 4.05 | 6.86 | 15.10 | 17.60 | 12.40 | 3 | 2 | 4 | Receptor protein kinase TMK1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 47 | gi|224087891 | Q9SCZ4 | CL2320.Contig9_All | 2.00 | 1.42 | 2.00 | 8.20 | 9.50 | 6.70 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Receptor-like protein kinase FERONIA | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 48 | gi|225427230 | Q944A7 | CL5141.Contig1_All | 4.19 | 5.46 | 1.57 | 28.10 | 22.00 | 21.30 | 4 | 3 | 1 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase At4g35230 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 49 | gi|225426412 | Q9FHD7 | CL7376.Contig1_All | 2.59 | 7.34 | 8.62 | 11.30 | 25.50 | 25.70 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase At5g41260 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 50 | gi|145327199 | Q9CAR3 | CL8777.Contig2_All | 2.73 | 2.08 | 2.00 | 13.80 | 12.90 | 18.40 | 2 | 1 | 1 | SNF1-related protein kinase regulatory subunit gamma-1-like | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 51 | gi|194696644 | Q84TI7 | Unigene26174_All | 2.57 | 2.20 | 2.51 | 24.30 | 38.60 | 37.10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Sodium transporter HKT1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 52 | gi|359495505 | Q9LRB0 | CL315.Contig4_All | 2.00 | 0.74 | 2.00 | 11.60 | 17.60 | 6.80 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Sphingoid long-chain bases kinase 1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 53 | gi|225443039 | CL10751.Contig1_All | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 5.20 | 12.30 | 11.90 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Uncharacterized membrane protein YMR155W | Vitis vinifera | |

| 54 | gi|255542872 | Q8LGG8 | Unigene11881_All | 0.73 | 1.41 | 2.00 | 12.00 | 16.40 | 22.00 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Universal stress protein A-like protein | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 55 | gi|255556366 | Q8LGG8 | Unigene2529_All | 11.58 | 1.08 | 10.10 | 54.80 | 36.90 | 38.20 | 9 | 5 | 7 | Universal stress protein A-like protein | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 56 | gi|255554204 | O23016 | CL6704.Contig3_All | 2.99 | 3.24 | 2.35 | 23.20 | 23.80 | 19.20 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Voltage-gated potassium channel subunit beta | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 57 | gi|357501685 | Q9LHA4 | CL3237.Contig3_All | 9.72 | 1.48 | 12.15 | 18.50 | 22.50 | 21.70 | 6 | 6 | 6 | V-type proton ATPase subunit d2 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 58 | gi|225463325 | Q9ZQX4 | Unigene24187_All | 8.32 | 11.16 | 9.34 | 43.90 | 50.00 | 38.50 | 5 | 7 | 6 | V-type proton ATPase subunit F | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 59 | gi|225432878 | Q0WNY5 | CL3494.Contig3_All | 6.01 | 5.30 | 5.91 | 21.00 | 22.10 | 20.80 | 3 | 4 | 3 | Wall-associated receptor kinase-like 18 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 60 | gi|124221924 | Q9LZM4 | CL6319.Contig3_All | 15.22 | 6.29 | 8.21 | 23.30 | 24.50 | 28.10 | 7 | 3 | 6 | Wall-associated receptor kinase-like 20 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| 61 | gi|255569405 | Q8RXN0 | CL4681.Contig3_All | 6.01 | 1.81 | 18.60 | 15.70 | 3 | 1 | ABC transporter G family member 11 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 62 | gi|171854675 | P49608 | CL2995.Contig26_All | 2.00 | 2.00 | 29.80 | 14.60 | 1 | 1 | Aconitate hydratase | Cucurbita maxima | |||

| 63 | gi|18076583 | Q8S9L6 | CL9653.Contig1_All | 2.00 | 2.01 | 9.90 | 11.00 | 1 | 1 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase 29 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 64 | gi|225445342 | CL13252.Contig2_All | 0.85 | 3.64 | 10.50 | 7.40 | 2 | 4 | dnaJ homolog subfamily C member 13-like | Vitis vinifera | ||||

| 65 | gi|255556438 | Q9SEE5 | Unigene35913_All | 2.00 | 2.00 | 18.40 | 22.60 | 3 | 3 | Galactokinase | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 66 | gi|225463623 | CL14543.Contig1_All | 3.87 | 1.70 | 18.30 | 9.00 | 3 | 2 | Glycerol kinase isoform 1 | Vitis vinifera | ||||

| 67 | gi|359497728 | Q9ASS4 | CL4159.Contig1_All | 2.22 | 3.37 | 21.00 | 24.50 | 3 | 3 | Inactive leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase At5g48380 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 68 | gi|255552774 | O04567 | Unigene22230_All | 1.41 | 0.55 | 8.60 | 19.50 | 1 | 2 | Inactive receptor kinase At1g27190 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 69 | gi|255586379 | Q9LVM0 | CL2318.Contig1_All | 2.00 | 3.46 | 13.80 | 17.10 | 1 | 2 | Inactive receptor kinase At5g58300 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 70 | gi|225423806 | Q9LI83 | CL3370.Contig1_All | 2.00 | 1.61 | 8.90 | 8.20 | 1 | 1 | Phospholipid-transporting ATPase 10 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 71 | gi|359485026 | Q03194 | CL16623.Contig1_All | 2.16 | 0.83 | 24.60 | 18.20 | 3 | 2 | Plasma membrane ATPase 4 | Nicotiana plumbaginifolia | |||

| 72 | gi|125535713 | Q2QY12 | Unigene37237_All | 0.79 | 2.00 | 28.40 | 35.80 | 1 | 1 | Plasma membrane-type calcium-transporting ATPase 4 | Oryza sativa subsp. japonica | |||

| 73 | gi|225448277 | Q9FY75 | CL2807.Contig2_All | 2.04 | 2.02 | 4.90 | 4.90 | 1 | 1 | Potassium transporter 7 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 74 | gi|147768303 | Q2MHE4 | CL2457.Contig4_All | 3.92 | 1.82 | 29.10 | 12.60 | 2 | 1 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase HT1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 75 | gi|255540259 | Q8LBB2 | CL2181.Contig2_All | 4.97 | 3.84 | 22.30 | 25.40 | 3 | 2 | SNF1-related protein kinase regulatory subunit gamma-1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 76 | gi|350535282 | Q9LKW9 | Unigene18167_All | 2.00 | 2.00 | 21.30 | 12.60 | 1 | 1 | Sodium/hydrogen exchanger 7 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 77 | gi|224141283 | Q8LGG8 | CL2994.Contig3_All | 2.00 | 2.20 | 16.60 | 14.90 | 1 | 1 | Universal stress protein A-like protein | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 78 | gi|285309967 | O04916 | CL2995.Contig22_All | 4.00 | 5.01 | 22.90 | 22.40 | 2 | 4 | Aconitate hydratase | Solanum tuberosum | |||

| 79 | gi|224119508 | Q9SYG7 | CL12585.Contig1_All | 2.76 | 2.47 | 11.80 | 15.90 | 3 | 1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 7 member B4 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 80 | gi|225438980 | O64816 | CL136.Contig4_All | 0.37 | 1.44 | 15.20 | 27.50 | 1 | 1 | Casein kinase II subunit alpha | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 81 | gi|224056853 | P46256 | Unigene21704_All | 6.08 | 5.67 | 31.00 | 36.80 | 8 | 10 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | Pisum sativum | |||

| 82 | gi|6563322 | O04266 | Unigene25085_All | 2.04 | 2.00 | 39.40 | 37.30 | 6 | 6 | GTP-binding protein SAR1A | Brassica campestris | |||

| 83 | gi|224113157 | O81832 | CL3993.Contig2_All | 2.01 | 2.00 | 12.80 | 13.90 | 2 | 2 | G-type lectin S-receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At4g27290 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 84 | gi|225435578 | Q39202 | CL16541.Contig3_All | 2.53 | 2.29 | 16.80 | 17.30 | 2 | 2 | G-type lectin S-receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase RLK1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 85 | gi|406870037 | P09189 | CL2270.Contig2_All | 2.78 | 3.55 | 76.20 | 78.10 | 5 | 8 | Heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein | Petunia hybrida | |||

| 86 | gi|1708314 | P51819 | CL1535.Contig1_All | 1.79 | 5.80 | 47.20 | 41.60 | 24 | 29 | Heat shock protein 83 | Ipomoea nil | |||

| 87 | gi|359493983 | C0LGN2 | Unigene56808_All | 5.42 | 2.00 | 18.20 | 19.20 | 3 | 1 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At3g14840 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 88 | gi|225447810 | C0LGH2 | CL11120.Contig8_All | 2.53 | 2.00 | 24.50 | 25.20 | 1 | 1 | LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At1g56130 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 89 | gi|255571730 | C0LGT6 | CL11164.Contig3_All | 0.92 | 6.30 | 26.80 | 23.60 | 1 | 3 | LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase EFR | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 90 | gi|255546773 | P98204 | CL587.Contig1_All | 2.00 | 0.48 | 12.80 | 18.50 | 1 | 1 | Phospholipid-transporting ATPase 1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 91 | gi|224095202 | Q9C660 | Unigene8986_All | 2.00 | 2.00 | 18.90 | 23.00 | 1 | 1 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase PERK10 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 92 | gi|356526137 | Q9LK03 | CL14215.Contig2_All | 2.00 | 2.00 | 26.50 | 20.00 | 1 | 1 | Proline-rich receptor-like protein kinase PERK2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 93 | gi|302783030 | Q67UF5 | CL3927.Contig4_All | 3.39 | 2.00 | 27.70 | 28.40 | 3 | 4 | Protein disulfide isomerase-like 2–3 | Oryza sativa subsp. japonica | |||

| 94 | gi|296088320 | Q35638 | Unigene54779_All | 1.52 | 1.17 | 29.00 | 21.40 | 1 | 1 | Rac-like GTP-binding protein RHO1 | Pisum sativum | |||

| 95 | gi|359479658 | CL6981.Contig1_All | 2.51 | 4.04 | 23.10 | 20.90 | 2 | 2 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase BUD32 homolog | Vitis vinifera | ||||

| 96 | gi|386870491 | P11796 | Unigene31392_All | 4.00 | 6.00 | 48.70 | 37.60 | 3 | 5 | Superoxide dismutase [Mn] | Nicotiana plumbaginifolia | |||

| 97 | gi|359496003 | CL13681.Contig2_All | 1.00 | 1.40 | 7.00 | 24.70 | 1 | 1 | Transaldolase-like | Vitis vinifera | ||||

| 98 | gi|224113019 | O82702 | Unigene35531_All | 1.55 | 2.09 | 67.50 | 48.10 | 12 | 9 | V-type proton ATPase subunit G 1 | Nicotiana tabacum | |||

| 99 | gi|44917147 | O49996 | Unigene34923_All | 2.00 | 6.00 | 45.20 | 62.10 | 3 | 10 | 14-3-3-like protein D | Nicotiana tabacum | |||

| 100 | gi|225465653 | CL3375.Contig1_All | 1.80 | 1.22 | 30.60 | 9.60 | 1 | 1 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1 | Vitis vinifera | ||||

| 101 | gi|225451255 | Unigene49648_All | 2.02 | 4.00 | 23.30 | 52.40 | 1 | 2 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 11 isoform 2 | Vitis vinifera | ||||

| 102 | gi|225427157 | Q8LPK2 | CL12866.Contig4_All | 2.92 | 2.01 | 12.80 | 19.40 | 2 | 1 | ABC transporter B family member 2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 103 | gi|296085461 | Q8LPJ4 | CL6385.Contig3_All | 2.93 | 6.88 | 15.00 | 22.90 | 4 | 4 | ABC transporter E family member 2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 104 | gi|2493046 | Q40089 | CL7437.Contig3_All | 10.51 | 7.86 | 56.90 | 53.40 | 9 | 7 | ATP synthase subunit delta' | Ipomoea batatas | |||

| 105 | gi|267631890 | P28582 | Unigene22237_All | 2.88 | 8.71 | 28.90 | 28.90 | 4 | 6 | Calcium-dependent protein kinase | Daucus carota | |||

| 106 | gi|11131745 | P93508 | Unigene55350_All | 0.54 | 1.17 | 18.30 | 8.70 | 1 | 1 | Calreticulin | Ricinus communis | |||

| 107 | gi|255566201 | CL6055.Contig2_All | 3.95 | 3.92 | 34.30 | 40.70 | 2 | 2 | Co-chaperone protein HscB | Ricinus communis | ||||

| 108 | gi|225462922 | Q8W207 | CL6827.Contig1_All | 1.23 | 2.00 | 12.10 | 23.20 | 1 | 2 | COP9 signalosome complex subunit 2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 109 | gi|225430043 | Q08298 | CL6583.Contig2_All | 6.00 | 4.00 | 33.60 | 15.20 | 3 | 4 | Dehydration-responsive protein RD22 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 110 | gi|359477103 | P22242 | Unigene33129_All | 8.04 | 5.58 | 19.70 | 37.50 | 4 | 3 | Desiccation-related protein PCC13-62 | Craterostigma plantagineum | |||

| 111 | gi|224120498 | P21616 | CL3527.Contig4_All | 2.00 | 4.00 | 56.90 | 55.60 | 1 | 2 | Pyrophosphate-energized vacuolar membrane proton pump | Vigna radiata var. radiata | |||

| 112 | gi|255562954 | Q2MHE4 | Unigene13016_All | 3.03 | 7.85 | 13.30 | 22.20 | 1 | 4 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase HT1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 113 | gi|225580057 | Q9XIC7 | CL10222.Contig1_All | 1.66 | 1.00 | 16.50 | 25.90 | 1 | 2 | Somatic embryogenesis receptor kinase 2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

| 114 | gi|75326539 | Q75VR1 | CL1554.Contig12_All | 2.74 | 1.33 | 10.30 | 15.30 | 2 | 1 | Two pore calcium channel protein 1A | Nicotiana tabacum | |||

| 115 | gi|148907059 | Q9LHA4 | CL3237.Contig1_All | 7.19 | 1.74 | 20.50 | 25.90 | 6 | 4 | V-type proton ATPase subunit d2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | |||

T1: first biological replicate; T2: second biological replicate; T3: third biological replicate

*: Unused ProtScore = a measurement of all the peptide evidence for a protein that is not better explained by a higher ranking protein. It is the true indicator of protein confidence.

#: % Coverage = percentage of matching amino acids from identified peptides having confidence greater than 0 divided by the total number of amino acids in the sequence.

^: Peptides (95%) = number of distinct peptides having at least 95% confidence.

Fig 4. Schematic diagram of salt gland cell showing predicted cellular localization of selected list of 10 annotated proteins identified from salt gland-enriched epidermal tissues of A. officinalis.

The selected proteins were classified based on GO for cellular component and Swissprot ID of the proteins are included in parentheses.

Discussion

In this study, we adopted the state-of-the-art shotgun technique to look into the proteome of salt gland-rich tissues. This approach allows the fast detection of proteins from complex mixtures and is rapidly replacing commonly gel-based methods (e.g., two-dimensional gel electrophoresis coupling with MS) [20,24,25]. Through this approach, many more proteins could be obtained (i.e, 2188 proteins identified in salt gland-rich tissues; Fig 2B and S7 Table). Among them, many of the proteins that are known to play a role in defence and stress responses in plants (e.g., stress proteins, HSPs, co-chaperones, dehydration-responsive/desiccation-related proteins, AAA-ATPase) were identified in the salt gland-rich tissues in this study (Table 2 and S8 Table). HSPs, for examples, which are one of those proteins commonly identified in this study, are members of the molecular chaperones that help to protect the plants against stress (e.g., salt stress) by refolding the proteins and maintaining their native conformation, thus preventing irreversible protein aggregation during adverse conditions [17,19,26,27]. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase that had been identified and suggested to play a role in salt tolerance mechanisms that are common to both the glycophytes and mangrove plants [16] was also found in our salt gland-rich protein pools (Table 2). Proteins involved in signal transduction, such as 14-3-3-like protein and calreticulin that had been shown to be upregulated during salt stress in K. candel [17] and reported in the plasma membrane proteins (i.e., 14-3-3-like protein) of A. officinalis leaves [19] had also been identified herein in the salt gland-rich tissues (Table 2).

Earlier studies by Hill and Hill [28] and Faraday et al [29] looked into the ion fluxes of Limonium salt glands and possible involvement of ion pumps and channels during secretion had been suggested by Vassilyev and Stepanova [30]. Inhibitor studies investigating on the different types of ATPase activities or looking at various membrane proteins (channels, antiporters) during secretion had also been reported (e.g., [5,10,31–33]). Many membrane proteins (e.g., ABC transporters, sodium/potassium transporters, ATPases, aquaporins, proton pumps, sodium/hydrogen exchanger, ion channels) had been identified in the salt gland-rich protein pools (Table 2 and S8 Table) and could be involved during the desalination process. ABC transporters that are identified as one of the major transporters in our recent transcriptome study [34] and their abundance in the tonoplast and plasma membrane fractions of A. officinalis leaves [19] were also observed in the salt gland-rich protein pools in this study.

Secretion via the salt glands eliminates excess salts (predominantly Na+ and Cl-) from the plant tissues and is believed to be energy-requiring [2]. The identification of proteins associated to carbohydrate and energy metabolism (e.g., ATPases, ATP synthases, aconitate hydratases, GTP-binding proteins) in the salt gland-rich protein pools (Table 2 and S8 Table) suggest high metabolic rate within these plant tissues. Many of these proteins found in the salt gland-enriched tissues are involved in heterocyclic compound, ion and small molecule (e.g., ATP, GTP) binding (> 70%) and showed hydrolase, transferase and oxidoreductase activities (> 80%) (Figs 3 and 4, Table 2 and S8 Table) and the abundance of such proteins actually favours processes that are energy-dependent, including the desalination process in the salt glands. Determination of ATPase activities from leaves/leaf cells of salt gland-bearing species, for example, has been attempted in early studies [35,36]. Subsequent electrophysiological studies on Avicennia salt glands looked into possible ATPase activities [31,32]. Inhibitors of plasma membrane H+-ATPases (including orthovanadate) has been shown to inhibit salt secretion for both bicellular and multicellular glands [31,37]. High plasma membrane ATPase activity has been reported in the gland cells [38,39], suggesting possible role of plasma membrane P-type H+-ATPase in salt secretion. Recent studies on A. marina further suggest some dependence on increased ATPase and antiporter gene expression in nitric oxide-enhanced salt secretion [5].

A. officinalis under study is a salt gland-bearing tropical mangrove tree species growing towards the sea and needs to cope with ever-fluctuating salinities (0.5–35ppt) [2,40]. Taking into consideration that secretion removes not just salts, but involves an inevitable loss of water, the identification of water channels (i.e., aquaporins) at the protein level in this study further reinforce our earlier studies on the involvement of aquaporin during secretion in this species [10,34]. Salt glands of this species thus offer an excellent platform for studying dynamic responses in regulating salt and water during secretion under rapidly changing salinities. The identification of major proteins that can respond to stimulus and are involved in cellular processes enabling them to cope with dynamic salinity changes will help us understand the process better.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report the first proteomic analysis of salt gland-enriched tissues of a mangrove tree species. By comparing protein profiles of epidermal peels with mesophyll tissues, proteins found in salt gland-enriched tissues were identified, allowing GO analysis to be performed and a list of candidate proteins that could be involved in the desalination process identified. We believe that information obtained herein is valuable and can be used to dissect the molecular mechanisms that control the dynamics of secretion in mangrove salt glands.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository [41] with the dataset identifier PXD000771.

Supporting Information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge technical support provided by Protein & Proteomics Centre, DBS, NUS, thank Xing Fei, Qifeng for guidance on protein preparation and bioinformatic data analysis and Sai Mun for critically reading through the manuscript. We thank the PRIDE Team for assisting in the uploading of supplementary data.

Data Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD000771.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by research grants from Singapore National Research Foundation [under its Environmental & Water Technologies Strategic Research Programme administered by the Environment] & Water Industry Programme Office of the PUB, NRF-EWI-IRIS (2P 10004/81) (R-706-000-010-272) and (R-706-000-040-279) and the National University of Singapore (R-154-000-505-651). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Flowers TJ, Galal HK, Bromham L. Evolution of halophytes: multiple origins of salt tolerance in land plants. Funct Plant Biol. 2010;37: 604–612. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomson WW, Faraday CD, Oross JW. Salt glands In: Baker DA, Hall JL, editors. Solute transport in plant cells and tissues. England: Longman Scientific & Technical; 1988. pp. 498–537. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ma HY, Tian CY, Feng G, Yuan JF. Ability of multicellular salt glands in Tamarix species to secrete Na+ and K+ selectively. Sci China Life Sci. 2011;54: 282–289. 10.1007/s11427-011-4145-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Labidi N, Ammari M, Mssedi D, Benzerti M, Snoussi S, Abdelly C. Salt excretion in Suaeda fruticosa . Acta Biol Hung. 2010;61: 299–312. 10.1556/ABiol.61.2010.3.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen J, Xiao Q, Wu F, Dong X, He J, Pei Z, et al. Nitric oxide enhances salt secretion and Na+ sequestration in a mangrove plant, Avicennia marina, through increasing the expression of H+-ATPase and Na+/H+ antiporter under high salinity. Tree Physiol. 2010;30: 1570–1585. 10.1093/treephys/tpq086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hassine AB, Ghanem ME, Bouzid S, Lutts S. Abscisic acid has contrasting effects on salt excretion and polyamine concentrations of an inland and a coastal population of the Mediterranean xero-halophyte species Atriplex halimus . Ann Bot. 2009;104: 925–936. 10.1093/aob/mcp174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kobayashi H, Masaoka Y. Salt secretion in Rhodes grass (Chloris gayana Kunth) under conditions of excess magnesium. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2008;54: 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kobayashi H, Masaoka Y, Takahashi Y, Ide Y, Sato S. Ability of salt glands in Rhodes grass (Chloris gayana Kunth) to secrete Na+ and K+ . Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2007;53: 764–771. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tan WK, Lim TM, Loh CS. A simple, rapid method to isolate salt glands for three-dimensional visualization, fluorescence imaging and cytological studies. Plant Methods. 2010;6: 24 10.1186/1746-4811-6-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan WK, Lin Q, Lim TM, Kumar P, Loh CS. Dynamic secretion changes in the salt glands of the mangrove tree species Avicennia officinalis in response to a changing saline environment. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36: 1410–1422. 10.1111/pce.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chong KY, Tan HTW, Corlett RT. A checklist of the total vascular plant flora of Singapore: native, naturalised and cultivated species. Singapore: Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Polidoro BA, Carpenter KE, Collins L, Duke NC, Ellison AM, Ellison JC, et al. The loss of species: mangrove extinction risk and geographic areas of global concern. PLoS One. 2010;5: e10095 10.1371/journal.pone.0010095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tyerman SD. The devil in the detail of secretions. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36: 1407–1409. 10.1111/pce.12110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tomlinson PB. The botany of mangroves. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang H, Han B, Wang T, Chen S, Li H, Zhang Y, et al. Mechanisms of plant salt response: insights from proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2012;11: 49–67. 10.1021/pr200861w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tada Y, Kashimura T Proteomic analysis of salt-responsive proteins in the mangrove plant, Bruguiera gymnorhiza . Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50: 439–446. 10.1093/pcp/pcp002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang L, Liu X, Liang M, Tan F, Liang W, Chen Y, et al. Proteomic analysis of salt-responsive proteins in the leaves of mangrove Kandelia candel during short-term stress. PLoS One. 2014;9: e83141 10.1371/journal.pone.0083141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu Z, Chen J, Zheng H-L. Physiological and proteomic characterization of salt tolerance in a mangrove plant, Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (L.) Lam. Tree Physiol. 2012;32: 1378–1388. 10.1093/treephys/tps097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krishnamurthy P, Tan XF, Lim TK, Lim TM, Kumar PP, Loh CS, et al. Proteomic analysis of plasma membrane and tonoplast from the leaves of mangrove plant Avicennia officinalis . Proteomics. 2014;14: 2545–2557. 10.1002/pmic.201300527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geiser L, Dayon L, Vaezzadeh A, Hochstrasser D. Shotgun proteomics: A relative quantitative approach using off-gel electrophoresis and LC-MS/MS In: Walls D, Loughran ST, editors. Protein chromatography. Humana Press; 2011. pp. 459–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sadowski PG, Dunkley TP, Shadforth IP, Dupree P, Bessant C, Griffin JL, et al. Quantitative proteomic approach to study subcellular localization of membrane proteins. Nat Protoc. 2006;1: 1778–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25: 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pont F, Fournie JJ. Sorting protein lists with nwCompare: a simple and fast algorithm for n-way comparison of proteomic data files. Proteomics. 2010;10: 1091–1094. 10.1002/pmic.200900667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abdallah C, Dumas-Gaudot E, Renaut J, Sergeant K. Gel-based and gel-free quantitative proteomics approaches at a glance. Int J Plant Genomics. 2012;2012: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Delahunty C, Yates JR. Proteomics: A shotgun approach without two-dimensional gels. eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang W, Vinocur B, Shoseyov O, Altman A. Role of plant heat-shock proteins and molecular chaperones in the abiotic stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9: 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vierling E. The roles of heat-shock proteins in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42: 579–620. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hill AE, Hill BS. The electrogenic chloride pump of the Limonium salt gland. J Membrane Biol. 1973;12: 122–144. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Faraday CD, Quinton PM, Thomson WW. Ion fluxes across the transfusion zone of secreting Limonium salt glands determined from secretion rates, transfusion zone areas and plasmodesmatal frequencies. J Exp Bot. 1986;37: 482–494. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vassilyev AE, Stepanova AA. The ultrastructure of ion-secreting and non-secreting salt glands of Limonium platyphyllum . J Exp Bot. 1990;41: 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dschida WJ, Platt-Aloia KA, Thomson WW. Epidermal peels of Avicennia germinans (L.) Stearn: A useful system to study the function of salt glands. Ann Bot-London. 1992;70: 501–509. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balsamo RA, Adams ME, Thomson WW. Electrophysiology of the salt glands of Avicennia germinans . Int J Plant Sci. 1995;156: 658–667. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krishnamurthy P, Jyothi-Prakash PA, Qin L, He J, Lin Q, Loh CS, et al. Role of root hydrophobic barriers in salt exclusion of a mangrove plant Avicennia officinalis . Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37: 1656–1671. 10.1111/pce.12272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jyothi-Prakash PA, Mohanty B, Wijaya E, Lim TM, Lin Q, Loh CS, et al. Identification of salt gland-associated genes and characterization of a dehydrin from the salt secretor mangrove Avicennia officinalis . BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14: 291 10.1186/s12870-014-0291-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hill AE, Hill BS. The Limonium salt gland: A biophysical and structural study. Int Rev Cytol. 1973;35: 299–319. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kylin A, Gee R. Adenosine triphosphatase activities in leaves of the mangrove Avicennia nitida Jacq: influence of sodium to potassium ratios and salt concentrations. Plant Physiol. 1970;45: 169–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bhatti AS, Sarwar G. Secretion and uptake of salt ions by detached Leptochloa fusca L. Kunth (Kallar grass) leaves. Environ Exp Bot. 1993;33: 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Balsamo RA, Thomson WW. Isolation of mesophyll and secretory cell protoplasts of the halophyte Ceratostigma plumbaginoides (L.): A comparison of ATPase concentration and activity. Plant Cell Rep. 1996;15: 418–422. 10.1007/BF00232067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Naidoo Y, Naidoo G. Cytochemical localization of adenosine triphosphatase activity in salt glands of Sporobolus virginicus . S Afr J Bot. 1999;65: 370–373. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ng PKL, Sivasothi N. A guide to the mangroves of Singapore I, The ecosystem and plant diversity. Singapore: Singapore Science Centre; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vizcaíno JA, Côté RG, Csordas A, Dianes JA, Fabregat A, Foster JM, et al. The PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41: D1063–D1069. 10.1093/nar/gks1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD000771.