Abstract

PURPOSE

Sexual activity is an important component of quality of life for women across their lifespan. Prior studies show a decline in sexual activity with age, but these studies often fail to consider the role of sexual satisfaction. The aim of this study is to give updated prevalence estimates of sexual activity among women and to elucidate factors associated with sexual activity and sexual satisfaction.

METHODS

We report a cross-sectional analysis of the second wave of a nationally representative sample of US adults aged 28 to 84 years, the Survey of Midlife Development in the United States. The survey used self-administered questionnaires to assess demographic data, self-rated physical and mental health, medical problems and medication use, relationship factors, and sexual activity and satisfaction.

RESULTS

Of 2,116 women who answered the questions regarding sexuality, 1,345 (61.8%) women were sexually active in the previous 6 months. The proportion of women who were sexually active decreased with advancing age. Women who were married or cohabitating had approximately 8 times higher odds of being sexually active (odds ratio = 7.91, 95% CI, 4.16–15.04; P <.001). Among women aged 60 years and older who were married or cohabitating, most (59.0%) were sexually active. Among women who were sexually active, higher relationship satisfaction (P <.001), better communication (P = .011), and higher importance of sex P = .040) were related to higher sexual satisfaction, but age was not (P = .79).

CONCLUSIONS

A considerable proportion of midlife and older women remain sexually active if they have a partner available. Psychosocial factors (relationship satisfaction, communication with romantic partner, and importance of sex) matter more to sexual satisfaction than aging among midlife and older women.

Keywords: women’s health, sexuality, aging, female sexual function, sexual satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

The US population is aging. By 2030, there will be about 72.1 million individuals aged 65 years and older in the United States, representing 19% of the population.1 In 2011 the first baby boomers turned 65 years old. As this unique population moves through midlife and into older age, there is an increased interest in how sexuality changes with aging.

There is a strong link between a healthy sex life and higher quality of life as individuals age.2–7 Prior studies on the relationship between sexuality and aging in women have shown a decrease in sexual activity and sexual function with time.5,8–13 These studies, however, have limitations: (1) small sample sizes; (2) a focus only frequency of sexual activity and include no information on sexual satisfaction, despite sexual satisfaction also being important to women14,15; and (3) the use of clinical practice–based samples, which may include more women with sexual function complaints or medical problems than the general population.

In this study, we used the second wave of a nationally representative sample (the Study of Midlife Development in the United States, MIDUS II) of women aged 28 to 84 years to examine the prevalence of sexual activity by age. We identified the correlates of both sexual activity and sexual satisfaction, as well as the relationship between sexual activity and sexual satisfaction.

METHODS

Population

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using data from MIDUS II (2004–2006). The first wave of MIDUS included a random-digit dialing sample of 7,108 individuals in the mainland United States. For each household contacted, 1 respondent between the ages of 25 and 74 years was randomly selected. Older people and men were oversampled. Non–English-speaking and institutionalized individuals were excluded. Of the 7,108 adults in the first wave, 4,963 were successfully interviewed in MIDUS II (mortality-adjusted response rate 75%).16 Only women were included in the current analysis. All participants provided informed consent, and the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison approved the study.

Measures

Participants completed a telephone interview and self-administered questionnaires regarding demographics, physical and mental health, and sexuality. Women were asked how many sexual partners they had in the previous 12 months. If they answered any number greater than 0, they were asked, “Over the past 6 months, on average, how often have you had sex with someone?” A specific definition of sex was not given in the survey, and so interpretation was up to the individual. Individuals who answered never or not at all were considered sexually inactive; all others were considered sexually active, unless they did not answer the question.

Sexual satisfaction was assessed by the question, “How would you rate the sexual aspect of your life these days?” Responses were rated using a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 = worst to 10 = best. Prior sexual satisfaction was assessed by the question, “Looking back 10 years ago, how would you rate the sexual aspect of your life at that time?” using the same 0-to-10 scale. Importance of sex was assessed by the question, “To what extent would you say that sexual expression is an important part of your relationships?” Responses were rated using a Likert scale ranging from a lot to some to a little to not at all. Women who were married or living with someone in a marriage-like relationship were considered romantically partnered. Menopausal status was assigned based on self-reported bleeding status using a modification of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop classification.17 Women who had a hysterectomy but still had 1 or 2 ovaries and women who had bilateral oophorectomy were considered as separate groups. Medication use and pain with intercourse in the prior 30 days was evaluated by self-report. Depression status was assessed using a validated self-report scale based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Revision diagnosis of depression.18,19 Communication was evaluated by the question, “How much can you open up to your spouse or partner if you need to talk about your worries?” with a 4-point Likert scale ranging from a lot to not at all.

Statistical Analyses

Means, medians, standard deviations, and percentages, as appropriate, were used to describe sexually inactive and sexually active women. Poststratification weights based on race, age, and education status provided by the MIDUS II study group20 were used to present means and percentages for the general population. Because no sampling was conducted for the second wave follow-up study, only population-based adjustment weights were created for MIDUS II. Sexual activity was considered as a dichotomous variable (any/none). The sexual satisfaction variable was divided into 3 levels (0–3, 4–7, 8–10). Univariate logistic regression was used to examine factors that may be related to sexual activity based on published literature. Factors related to the outcome at P <.10 were entered into a multivariate model. Romantic partner factors, such as partner age and health status, were highly collinear with whether the respondent was married or cohabitating and were not included in the multivariate model of sexual activity. Univariate ordinal logistic regression was used to examine factors that may be related to sexual satisfaction. Factors related to the outcome at P <0.10 were entered into a multivariate model. The final model met the proportional odds assumption. Analyses of sexual satisfaction were restricted to women who were sexually active in the prior 6 months. Sampling weights were not significantly related to either sexual activity or sexual satisfaction and were not used in the regression models. All statistical analyses were conducted with StataSE 13.0 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

Demographics

Of 2,647 women in MIDUS II, more than one-half, 1,475 (55.7%), reported having at least 1 sexual partner in the past year, 641 (25.2%) had no sexual partner in the past year, 116 (4.4%) refused to answer the question, and 408 (15.4%) had missing data. Women who refused to answer the question were older (P <.001), more likely to be postmenopausal (P = .005), less likely to be romantically partnered (P <.001), and had lower income (P <.001), lower education status (P <.001), and poorer health (P = .023) than those who answered. Women for whom data were missing were younger (P <.001), more likely to be racial minorities (P <.001), and had poorer physical (P = .003) and mental health (P = .007) than those who responded.

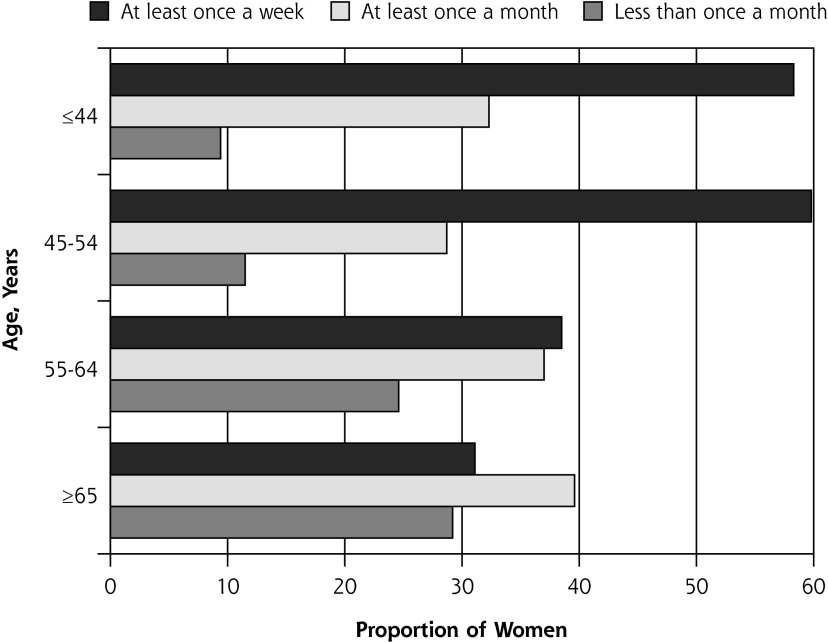

Of 1,799 romantically partnered women in MIDUS II, 1,202 were sexually active. Of 804 women who were not romantically partnered, 135 were sexually active. Of all women who responded to the questions regarding sex, 1,345 (61.8%) were sexually active (Figure 1). Characteristics of sexually inactive and active women are summarized in Table 1. The mean ages of sexually inactive women and sexually active women were 62.0 years (SD = 11.8 years) and 51.8 years (SD = 10.9 years), respectively. Most respondents were white, and approximately one-half the sample either naturally or surgically postmenopausal.

Figure 1.

Partner status, sexual activity, and sexual satisfaction of women in MIDUS II (The Survey of Midlife Development in the United States).

Note: Of 31 women who had missing data regarding partner status, 23 were not sexually active, and 8 were sexually active. Satisfaction is based on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 indicates the lowest level of sexual satisfaction.

a Partnered = married or living together in a marriage-like relationship.

b Any sexual activity with a partner in the prior 6 months.

c Weighted mean estimate, based on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 indicating the least amount of satisfaction.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sexually Inactive and Sexually Active Women in MIDUS II (n = 2,116)

| Variable | Sexually Inactive | Sexually Active | P Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No. | Weighted %a | No. | Weighted %a | ||

| All women in MIDUS II | 771 | 38.2 | 1,345 | 61.8 | — |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.0 (11.8) | 51.8 (10.9) | <.001 | ||

| Sexual orientation | .002 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 771 | 95.2 | 1,313 | 97.5 | |

| Homosexual or bisexual | 28 | 4.9 | 22 | 2.5 | |

| Race | .20 | ||||

| White | 692 | 87.6 | 1,240 | 88.9 | |

| Black and/or African American | 38 | 8.9 | 49 | 7.4 | |

| Other | 36 | 3.6 | 51 | 3.7 | |

| Hispanic | .60 | ||||

| No | 748 | 96.8 | 1,298 | 95.7 | |

| Yes | 21 | 3.2 | 42 | 4.3 | |

| Total annual household income, mean (SD), $c | 42,749 (44,753) | 79,874 (61,201) | <.001 | ||

| Highest education completed | <.001 | ||||

| Some high school or less | 65 | 17.9 | 55 | 7.9 | |

| Completed high school or GED | 257 | 34.9 | 370 | 38.0 | |

| Some college | 167 | 19.7 | 306 | 20.1 | |

| Completed college degree | 155 | 15.9 | 386 | 20.2 | |

| Graduate or postgraduate professional school | 125 | 11.6 | 226 | 13.8 | |

| Married or cohabitating | <.001 | ||||

| No | 480 | 67.5 | 135 | 12.9 | |

| Yes | 268 | 32.5 | 1,202 | 87.1 | |

| Romantic partner age, mean (SD), y | 66.3 (11.9) | 54.7 (11.8) | <.001 | ||

| Chronic conditions, mean (SD), No. | 3.3 (3.1) | 2.3 (2.2) | <.001 | ||

| Menopausal status | <.001 | ||||

| Premenopausal | 58 | 8.3 | 331 | 29.6 | |

| Perimenopausal | 40 | 6.9 | 213 | 18.4 | |

| Postmenopausal | 347 | 41.8 | 352 | 24.2 | |

| Hysterectomy, one or both ovaries intact | 116 | 19.8 | 161 | 13.9 | |

| Bilateral oophorectomy | 169 | 23.2 | 208 | 13.9 | |

GED = General Educational Development test completion; MIDUS = Survey of Midlife Development in the United States.

Note: There were 531 women in MIDUS II who did not answer the questions regarding sexual activity.

Weighted percentages use information regarding age, race, and education to estimates for the general US population.

For sexually inactive vs active women, using the t test, χ2, or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

Assessed in 2004–2006.

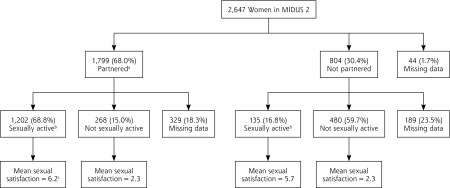

The proportion of women who were sexually active decreased with older age (Table 2). Most (61.2%) romantically partnered women were sexually active, including 59.0% of women aged 60 years and older. Frequency of sexual activity differed by age, with older women reporting less frequent sexual activity than younger women (Figure 2). Overall, 51.9% of the sexually active women had sex at least once a week, and 84.7% had sex at least once a month.

Table 2.

Proportion of Women in MIDUS II Who Were Sexually Active in the Previous 6 Months, by Age

| Age, Years | All Women in MIDUS II | Women Who Are Married or Cohabitating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No. | Raw % | Weighted % | No. | Raw % | Weighted % | |

| ≤39 | 190 | 88.8 | 89.7 | 157 | 97.5 | 95.7 |

| 40–49 | 429 | 80.8 | 74.6 | 397 | 92.3 | 89.9 |

| 50–59 | 396 | 67.6 | 64.9 | 356 | 86.4 | 86.8 |

| 60–69 | 240 | 51.4 | 48.6 | 212 | 70.7 | 68.4 |

| 70–79 | 79 | 30.6 | 21.1 | 69 | 48.6 | 41.3 |

| ≥80 | 11 | 18.3 | 14.6 | 11 | 44.0 | 36.8 |

MIDUS = Survey of Midlife Development in the United States.

Figure 2.

Frequency of sexual activity among sexually active women in the Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II), by age (n = 1,345).

Factors Associated With Sexual Activity

In multivariate models, women who were married or cohabitating had approximately 8 times the odds of being sexually active (odds ration [OR] = 7.91, 95% CI, 4.16–15.04; P <.001), Table 3. Importance of sex was also strongly related to sexual activity (P <.001); women who rated sex as more important were more likely to be sexually active. Other factors associated with being sexually active were lack of depression, higher prior sexual satisfaction, younger age, and lower body mass index.

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Being Sexually Active in the Previous 6 Months (vs Not) Among Women in MIDUS II, Multivariate Model (n = 2,116)

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P Value | Overall P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Married or cohabitating (yes) | 7.91 (4.16–15.04) | <.001 | |

| Importance of sex | <.001 | ||

| A lot | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Some | 1.10 (0.52–2.33) | .81 | |

| A little | 0.38 (0.17–0.81) | .012 | |

| Not at all | 0.06 (0.03–0.14) | <.001 | |

| Age | 0.95 (0.92, 0.99) | .002 | |

| Previous sexual satisfactiona | .007 | ||

| 0–2 | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| 3–5 | 1.61 (0.67–3.87) | .29 | |

| 6–8 | 2.88 (1.22–6.51) | .016 | |

| 9–10 | 2.89 (1.21–6.51) | .034 | |

| Body mass index | 0.96 (0.92–0.99) | .027 | |

| Depression (yes)b | 0.36 (0.18–0.73) | .005 | |

| Menopausal status | .65 | ||

| Premenopausal | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Perimenopausal | 1.50 (0.57–3.93) | .41 | |

| Postmenopausal | 0.90(0.35–2.30) | .83 | |

| Hysterectomy, one or both ovaries intact | 1.04 (0.36–3.00) | .94 | |

| Bilateral oophorectomy | 1.39 (0.46–4.14) | .56 |

BMI = body mass index; MIDUS = Survey of Midlife Development in the United States; OR = odds ratio.

Note: Adjusted for income, sexual orientation, education level, physical health, antidepressant use, and history of sexual assault.

Based on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 indicates the lowest level of sexual satisfaction.

Depression in the prior 12 months, based on validated scale developed by Wang et al.19

We conducted a sensitivity analysis for missing data regarding sexual activity. We repeated the analysis assuming all women who had missing data regarding sexual activity were sexually active, and then repeated the analysis assuming all women who had missing data regarding sexual activity were not sexually active. Results, including which variables were significant at the P <.05 level, were similar to those of the primary analysis.

Factors Associated With Sexual Satisfaction

Mean sexual satisfaction was much higher among sexually active women than among sexually inactive women (Figure 1). Weighted mean satisfaction for sexually active and inactive women (including women both with and without romantic partners) was 6.2 vs 2.3, respectively. Factors associated with higher sexual satisfaction among sexually active women in the multivariate model included higher relationship satisfaction, better communication, higher ratings of the importance of sex, more frequent sex, higher prior sexual satisfaction, absence of dyspareunia, and absence of antidepressant use (Table 4). Age and menopausal status were not related to sexual satisfaction in multivariate models.

Table 4.

Factors Associated With Current Sexual Satisfaction Among Sexually Active Women in MIDUS II, Multivariate Model (n = 1,334)

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P Value | Overall P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | .79 | |

| Relationship with romantic partner | <.001 | ||

| Excellent | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Very good | 0.38 (0.23–0.61) | <.001 | |

| Good | 0.22 (0.11–0.44) | <.001 | |

| Fair or poor | 0.16 (0.05–0.48) | .001 | |

| How much can you open up to romantic partner | .011 | ||

| A lot | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Some | 1.07 (0.68–1.69) | .78 | |

| A little | 0.88 (0.38–2.02) | .76 | |

| Not at all | 0.01 (0.00–0.15) | .001 | |

| Importance of sex | .040 | ||

| A lot | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Some | 0.67 (0.41–1.11) | .124 | |

| A little | 0.43 (0.22–0.84) | .013 | |

| Not at all | 0.22 (0.06–0.83) | .025 | |

| Frequency of sex | .040 | ||

| Two or more times a week | 2.93 (1.63–5.27) | <.001 | |

| Once a week | 1.30 (0.78–2.17) | .32 | |

| Two or three times a month | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Once a month | 0.29 (0.14–0.59) | .001 | |

| Less often than once a month | 0.13 (0.06–0.27) | <.001 | |

| Previous sexual satisfaction | <.001 | ||

| 0–3 | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| 4–7 | 1.00 (0.49–2.01) | .99 | |

| 8–10 | 2.25 (1.11–4.54) | .024 | |

| Pain with intercourse (yes) | 0.53 (0.36–0.78) | .001 | |

| Antidepressant use (yes) | 0.57 (0.35–0.92) | .021 | |

| Menopausal status | .44 | ||

| Premenopausal | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Perimenopausal | 0.64 (0.35–1.16) | .138 | |

| Postmenopausal | 1.08 (0.55–2.14) | .82 | |

| Hysterectomy, one or both ovaries intact | 0.77 (0.38–1.56) | .47 | |

| Hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy | 1.05 (0.51–2.17) | .89 |

OR = odds ratio; MIDUS = Survey of Midlife Development in the United States.

Note: MIDUS II adjusted for history of sexual assault, respondent physical and mental health, body mass index, romantic partner’s physical and mental health.

Based on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 indicates the lowest level of sexual satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

In this large cross-sectional study of adult women, we found that the proportion of women who were sexually active in the previous 6 months decreased with age. If they were romantically partnered, however, 61.2% were sexually active, including 59.0% of women aged 60 years and older. Romantic partner status was the factor most strongly related to whether a woman was sexually active or not. Among the women who were sexually active, psychosocial factors (such as relationship satisfaction, communication with her romantic partner, and importance of sex) were significantly related to sexual satisfaction, whereas age and menopausal status were not.

Our estimates regarding prevalence of sexual activity in midlife and older women are similar to reported estimates, which range from 53% to 79% depending on the population studied.11,21,22 Among women who were romantically partnered, the prevalence of sexual activity was high, even for women in their 70s and 80s. Prior studies have suggested that lack of a romantic partner is one of the most common reasons sexual inactivity in this population.8,23,24 Our study reinforced this relationship. As women move through midlife and older age, they may lose romantic partners to death, divorce, or separation, and become sexually inactive. Some women, however, may still participate in sexual activity outside a cohabitating romantic relationship; about 13% of sexually active women in MIDUS II were not married or cohabitating.

Loss of a partner is only one reason why women may be less likely to engage in sexual activity as they age. Advancing age may bring new health concerns in the woman or her partner, or menopausal changes, such as vaginal dryness, could affect sexual activity. In this analysis, the relationship between increasing age and decreasing sexual activity persisted, even when controlling for these factors and others. One reason may be a birth cohort effect—attitudes towards female sexuality have become more progressive during the past 5 decades,25 and women born in later decades may be more likely to participate in sexual activity at every age or more likely to report being sexually active on a survey. Longitudinal studies using a broad age range of women are necessary to untangle the effects of birth cohort from aging.

Our findings suggest that those women who do remain sexually active with age are able to maintain sexual satisfaction through the years despite the changes of menopause and aging. Women may adapt to these physical changes by changing their sexual behavior. For example, women who develop vaginal dryness may incorporate types of sexual activity other than penile-vaginal intercourse or incorporate therapeutic aids, such as lubricants. Women may also place more emphasis on other aspects of sex, such as emotional closeness, and less emphasis on physical sensations.26,27 These recalibrations in expectations surrounding sex may allow older women to feel sexually satisfied even if their sex lives are different from those of their younger years.

In contrast to age, psychosocial factors (relationship satisfaction, quality of communication with one’s romantic partner, and importance of sex) are highly related to sexual satisfaction. Prior studies have also shown a close connection between relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction, 6,23,28–34 but few studies have examined communication in particular.30,35 We find here that good communication between romantic partners in general, not just in relation to sex, was associated with higher sexual satisfaction.

Sexual satisfaction was lower among women who were not sexually active in the previous 6 months. It may be that these women would prefer to be active but lack a partner or have other interfering factors. It is also possible that low sexual satisfaction led to sexual inactivity, or that sexually inactive women are unsure how to respond to the question and mark “0” even if they are not sexually dissatisfied.

Our study has several limitations. This study is cross-sectional, so causality cannot be determined. Second, a validated measure of sexual satisfaction was not used. Third, MIDUS II had limited numbers of racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities. Finally, about 20% women did not respond to the questions regarding sexual activity, which may result in bias.

Health care professionals should be aware that many women maintain or want to maintain a satisfying sex life into middle age and beyond. Clinicians should ask women about sexual activity and sexual satisfaction and work with women to develop strategies to maintain a satisfying sex life with aging, including ways to improve relationship satisfaction and communication, such as relationship therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the investigators, staff, and individuals who participated in MIDUS. The authors also wish to thank Sonya Borerro, Joyce Chang, Kevin Kraemer, and Melissa McNeil, who made suggestions for revisions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: MIDUS was funded by the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development and the National Institute of Health’s National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166). The MIDUS data set is maintained and distributed by the National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging (NACDA) within the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). NACDA is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided to the primary author by the Department of Veteran’s Affairs.

Previous presentations: We presented an earlier version of these data as a poster presentation at the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) national conference in San Diego, California in April of 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Aging Statistics 2013 Updated May 8, 2013; cited 2013 Aug 8, 2013. http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/.

- 2.Edwards JB. Sexuality, a marriage, and well-being: the middle years. In: Rossi A, ed. Sexuality Across the Lifespan. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 1994: 233–260. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). AARP/Modern Maturity Sexuality Study. Atlanta, GA: NFO Research, Inc, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. ; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(1):39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprecher S. Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. J Sex Res. 2002;39(3):190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson-King D. Sexual satisfaction and marital well-being in the first years of marriage. J Soc Pers Relat. 1994;11(4):509–534. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess R, Conroy MB, Ness R, et al. Association of lifestyle and relationship factors with sexual functioning of women during midlife. J Sex Med. 2009;6(5):1358–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osborn M, Hawton K, Gath D. Sexual dysfunction among middle aged women in the community. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296 (6627):959–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawton K, Gath D, Day A. Sexual function in a community sample of middle-aged women with partners: effects of age, marital, socioeconomic, psychiatric, gynecological, and menopausal factors. Arch Sex Behav. 1994;23(4):375–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeiffer E, Verwoerdt A, Davis GC. Sexual behavior in middle life. Am J Psychiatry. 1972;128(10):1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hällström T. Sexuality in the climacteric. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1977; 4(1):227–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennerstein L, Dudley E, Burger H. Are changes in sexual functioning during midlife due to aging or menopause? Fertil Steril. 2001; 76(3):456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young MDG, Luquis R, Young T. Correlates of sexual satisfaction in marriage. Can J Hum Sex. 1998;7(2):115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen RC, Bachmann GA. Sexual well-being, happiness, and satisfaction, in women: the case for a new conceptual paradigm. J Sex Marital Ther. 2008;34(4):291–297, discussion 298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryff C, Almeida DM, Ayanian JS, et al. National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II), 2004–2006: Descriptions of MIDUS Samples. Washington, DC: National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Park City, Utah, July, 2001. Menopause. 2001;8(6):402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed Washington, DC: APA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(5): 284–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryff C, Almeida DM, Ayanian JS, et al. National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II), 2004–2006: Documentation of Post-stratification Weights Created at MIDUS 2. Washington, DC: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cain VSJC, Johannes CB, Avis NE, et al. Sexual functioning and practices in a multi-ethnic study of midlife women: baseline results from SWAN. J Sex Res. 2003;40(3):266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsiglio WDD, Donnelly D. Sexual relations in later life: a national study of married persons. J Gerontol. 1991;46(6):S338–S344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avis NE, Zhao X, Johannes CB, Ory M, Brockwell S, Greendale GA. Correlates of sexual function among multi-ethnic middle-aged women: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause. 2005;12(4):385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes R, Dennerstein L. The impact of aging on sexual function and sexual dysfunction in women: a review of population-based studies. J Sex Med. 2005;2(3):317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercer CHTC, Tanton C, Prah P, et al. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet. 2013;382(9907):1781–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winterich JA. Sex, menopause, and culture: Sexual orientation and the meaning of menopause for women’s sex lives. Gend Soc. 2003;17(4):627–642. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginsberg TB, Pomerantz SC, Kramer-Feeley V. Sexuality in older adults: behaviours and preferences. Age Ageing. 2005;34(5):475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byers ES. Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: a longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. J Sex Res. 2005;42(2):113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trudel G. Sexuality and marital life: results of a survey. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(3):229–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yela C. Predictors of and factors related to loving and sexual satisfaction for men and women. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 2000;50(1):235–243. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrance K-A, Byers ES. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Pers Relatsh. 1995;2(4):267–285. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen W, Blekesaune M. Sexual satisfaction in young adulthood: Cohabitation, committed dating or unattached lie? Acta Sociol. 2003;46(3):179–193. [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacNeil S, Byers S. The relationship between sexual problems, communication, and sexual satisfaction. Can J Hum Sex. 1997;6(4): 227–283. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young M, Denny G, Young T, Luquis R. Sexual satisfaction among married women age 50 and older. Psychol Rep. 2000;86(3 Pt 2): 1107–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cupach WR, Comstock R. Satisfaction with sexual communication in marriage: Links to sexual satisfaction and dyadic adjustment. J Soc Pers Relat. 1990;7(2):179–186. [Google Scholar]