Abstract

The therapy of autoinflammatory syndromes is an excellent example of the power of translational research. Recent advances in our understanding of the molecular and immunologic basis of this newly identified classification of disease have allowed for the application of novel, effective, targeted treatments with life-changing effects on patients. Although colchicine and TNF-α inhibitors are important therapies for specific autoinflammatory syndromes, the novel IL-1–targeted drugs are particularly effective for many of these diseases. Recently, the pharmaceutical industry has adopted a strategy of confirming the efficacy of new targeted drugs in often-ignored patients with orphan diseases, and US Food and Drug Administration policies have allowed for accelerated approval of these drugs, creating a win-win situation for patients and industry. This article reviews the general approach to the therapy of autoinflammatory diseases, focusing on current approved therapies and novel approaches that might be used in the future.

Keywords: Autoinflammatory, IL-1, inflammasome

The traditional clinical classification of immune-mediated diseases, including allergy, immunodeficiency, and autoimmunity, is based on differences in immunologic mechanisms and clinical symptomatology and has defined the medical specialties caring for patients with immune-mediated illnesses for more than 60 years. However, in the last 10 years, a new category of immunologic disease, known as autoinflammatory diseases, has been created to account for disorders that did not fit well into the classical disease groups.1 Although patients with these disorders can present with classic rheumatologic symptoms, including inflammation involving the joints, skin, muscles, and eyes, the underlying inflammatory mechanisms do not involve autoantibodies or antigen-specific T cells.2 Some patients also display episodic or precipitated symptoms, including urticaria and conjunctivitis, similar to those seen in allergic patients, but there is no evidence of IgE-mediated inflammation. Recurrent fever is a common feature of both autoinflammatory disorders and infections caused by immune deficiency. However, insufficient immune response to pathogens is not an immunologic characteristic of autoinflammatory diseases.

The autoinflammatory disorders are characterized by dysregulation of innate immunity, the arm of the immune system considered to be more primitive and less specific. Instead of lymphocyte or antibody responses to specific antigens based on a memory of prior exposure, innate immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells, sense conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns. The primary effectors of the innate immune response are myeloid cells, such as neutrophils and monocytes, and proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α.3 Cells from patients with some autoinflammatory disorders appear to be hypersensitive to exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns and endogenous danger-associated molecular patterns or constitutively active, resulting in uncontrolled cytokine-mediated inflammation. The possible triggers or mechanisms underlying the increased innate immune responses have begun to be elucidated after advances in the genetic basis of these disorders. The role of the adaptive immune system in the pathophysiology of these disorders is still unclear.4

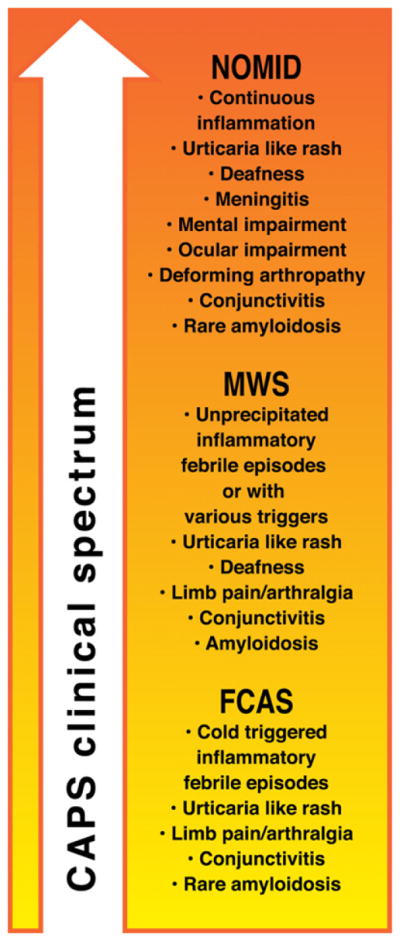

The diseases for which the autoinflammatory label was first applied are the hereditary fever disorders (Table I),5–57 including familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), and hyper-IgD syndrome. In addition, the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) have been included in this family and encompass a spectrum of diseases, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), the mildest form; Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), which is of intermediate severity; and neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID), the most severe phenotype (Fig. 1). Each of the hereditary fever diseases is characterized by recurrent episodes of systemic inflammation, including fever and other constitutional symptoms, as well as specific tissue inflammation, including joint and skin symptoms.2,61 However, there are specific clinical features for each syndrome that might help the clinician to differentiate and direct appropriate diagnostic tests.3 There are several recent reviews that describe the diagnostic approach to recurrent fever patients, but this is beyond the scope of this review.62

TABLE I.

Autoinflammatory disease therapies

| Clinical studies (adults/children) | No. of patients | Observations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hereditary fever disorders | |||

| FMF | Colchicine-controlled trials, adults8–10 | >100 | Episode number |

| Colchicine open-label trials, children11,12 | >100 | Episode number, inflammatory markers | |

| Anakinra case reports, both20–25 | <10 | All symptoms, inflammatory markers | |

| Rilonacept trial in progress | |||

| TRAPS | Etanercept small trials, both7,13 | >10 | Steroid dose, inflammatory markers |

| Anakinra case reports, both14,29,30 | <10 | Episode number, inflammatory markers | |

| Hyper-IgD syndrome with periodic fever | Anakinra case reports, both26–28 | <10 | All symptoms, inflammatory markers |

| CAPS | |||

| FCAS | Anakinra open-label trials, both16,17 | >10 | All symptoms, inflammatory markers |

| Rilonacept controlled trials, both18 | <100 | All symptoms, inflammatory markers | |

| Canakinumab controlled trials, both19 | <100 | All symptoms, inflammatory markers | |

| MWS | Anakinra open-label trials, both16 | >10 | Most symptoms, inflammatory markers |

| Rilonacept controlled trials, both18 | <10 | Most symptoms, inflammatory markers | |

| Canakinumab controlled trials, both19 | >10 | Most symptoms, inflammatory markers | |

| NOMID | Anakinra open-label trial, children15 | >10 | Most symptoms, inflammatory markers |

| Canakinumab trials in progress | |||

| Other hereditary disorders | |||

| Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne | Anakinra case reports, both33,34 | <10 | Skin symptoms |

| Blau syndrome | Anakinra case reports, adults31,32 | <10 | Symptoms in 1 patient but not all |

| Deficiency of IL-1 receptor antagonist | Anakinra case reports, children5,6 | >10 | All symptoms, inflammatory markers |

| Pseudogout | Anakinra case reports, adults37,38 | <10 | All symptoms |

| Nonhereditary disorders | |||

| Schnitzler syndrome | Anakinra case reports, adults39–45 | <10 | Skin symptoms |

| Systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Anakinra trials, children46–48 | <100 | Most symptoms and steroid dose in some |

| Rilonacept trials in progress | |||

| Canakinumab trials in progress | |||

| Adult-onset Still disease | Anakinra case reports, adults49–56 | >10 | Most symptoms and inflammatory markers |

| Acute gout | Anakinra small trials, adults35,36 | >10 | Symptoms in most |

| Chronic gout | Rilonacept controlled trial, adults57 | >10 | Symptoms in most |

FIG. 1.

The clinical continuum of CAPS, including NOMID, MWS, and FCAS.

In the last decade, there have been major advances in our knowledge of the genetic basis and pathogenesis of the hereditary fever disorders. This has resulted in an expansion of the autoinflammatory disease category to include diseases with related genetic abnormalities but different clinical features, such as Blau syndrome, the syndrome of pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne, mevalonic aciduria, pseudogout,61 and the recently described deficiency of IL-1 receptor antagonist.5,6 Further expansion of the category has resulted from the elucidation of the biology of several more common and complex diseases, such as gout, Crohn disease, systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and adult-onset Still disease. Finally, the expanding autoinflammatory disease family now includes other systemic inflammatory diseases with similar clinical features, such as Schnitzler syndrome, Behçet disease, and the syndrome of periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (Table I).3 The accompanying review in this journal focuses on the genetics and biology of the growing family of auto-inflammatory syndromes, whereas this review focuses on current and future therapy.

GENERAL THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

The primary treatment goal of reduction of inflammation in the autoinflammatory syndromes is similar to the clinical management of allergic and autoimmune diseases. Therefore it is not surprising that there is significant overlap in the therapeutic approaches for all of these conditions. Like most inflammatory diseases, the autoinflammatory disorders have features of chronic inflammation with effects on quality of life caused by constitutional symptoms and the potential for significant long-term morbidity, such as systemic amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis.63,64 Similar to many classic inflammatory disorders, the autoinflammatory diseases are also often characterized by episodic symptomatic flares that are either unpredictable or elicited by specific triggers, such as cold exposure in patients with FCAS.65 Therefore optimal therapies for the autoinflammatory diseases should be effective at both decreasing chronic inflammation and preventing acute flares but safe enough to be used for extended periods of time in these lifelong disorders. Until recently, controlled trials in patients with autoinflammatory syndromes were uncommon because of disease rarity and consequently a lack of pharmaceutical industry interest. This has changed in the last few years through the efforts of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) orphan disease program and industry recognition of the advantages of treating rare diseases as a proof of concept.

The pharmacologic approach to autoinflammatory disorders also parallels that of other inflammatory diseases. Traditional drugs, such as colchicine, used commonly in gout for centuries, are also the standard of care for FMF.66 Recent advances in targeting specific cytokines, such as TNF-α, have had a major effect on the care of patients with autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, but also have had a similar influence on the treatment of autoinflammatory disorders, including TRAPS and inflammatory bowel disease.7 However, corticosteroids, used commonly in both allergic and autoimmune diseases, are often not effective in the primarily innate immune-driven autoinflammatory syndromes, such as FMF and CAPS, and newer drugs that target IL-1 and have had only a modest effect on the therapy of autoimmune disease are increasingly seen as the drug of choice for most autoinflammatory diseases.67

COLCHICINE

The therapy with the most important and widespread effect on autoinflammatory disorders is colchicine, a medication extracted from the meadow saffron and used since the first century for rheumatologic diseases, such as gout.66 The serendipitous discovery of its effectiveness in the treatment of FMF in the early 1970s68 and subsequent well-designed clinical trials demonstrating efficacy at preventing acute FMF episodes and chronic inflammation–driven systemic amyloidosis have resulted in significantly decreased morbidity and mortality throughout the world in thousands of patients because of its wide availability and low cost (Table I).8–12 Although there are clear side effects caused by colchicine toxicity, including gastrointestinal, hematologic, and neuromuscular symptoms, it can be used safely in most patients if dosed appropriately and specific interacting drugs are avoided. Although colchicine has been the standard of care for FMF for more than 25 years, it was only recently that the FDA approved this ancient drug for gout and FMF.

The primary mechanism of action of colchicine is believed to be the inhibition of microtubule polymerization by binding to tubulin, which blocks cell mitosis in cells such as neutrophils. This is supported by the finding of decreased late-phase leukocyte accumulation in tissue from patients with FMF.69 However, more recent data suggest that colchicine has additional anti-inflammatory mechanisms involving altered expression of adhesion molecules and chemotactic factors. Colchicine also has an effect on uric acid crystal deposition and possibly on the generation of reactive oxygen species,70 factors that might play a role in the activation of pathways involved in other autoinflammatory disorders. Although colchicine is the standard of care for FMF, it is not effective in some patients with FMF or many patients with other autoinflammatory diseases and cannot be used in some patients because of side effects or concurrent medical conditions.

TARGETING TNF-α IN AUTOINFLAMMATORY DISEASE

The first translational success story in the autoinflammatory syndromes began with the positional cloning of the gene for TNF receptor 1 as the cause of TRAPS.1 Although the mechanisms involved in increased TNF-α–mediated inflammation in TRAPS are still unclear, this discovery prompted the use of available TNF-targeted therapies in these patients. Two open-label trials of etanercept, a soluble TNF receptor antagonist approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, in patients with TRAPS confirmed its clinical efficacy in preventing symptomatic episodes.7,13 However, further therapeutic experience demonstrated persistence of chronic subclinical inflammation and development of systemic amyloidosis in some patients while receiving the therapy. Surprisingly, the use of other TNF-α–directed therapies with presumed enhanced potency, such as mAbs to TNF-α commonly used in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, resulted in worsening of disease in some patients with TRAPS.71,72 Recent experiences suggest that the mechanisms involved in TRAPS intersect with the IL-1 pathway (Table I).14

REGULATION OF THE IL-1 PATHWAY

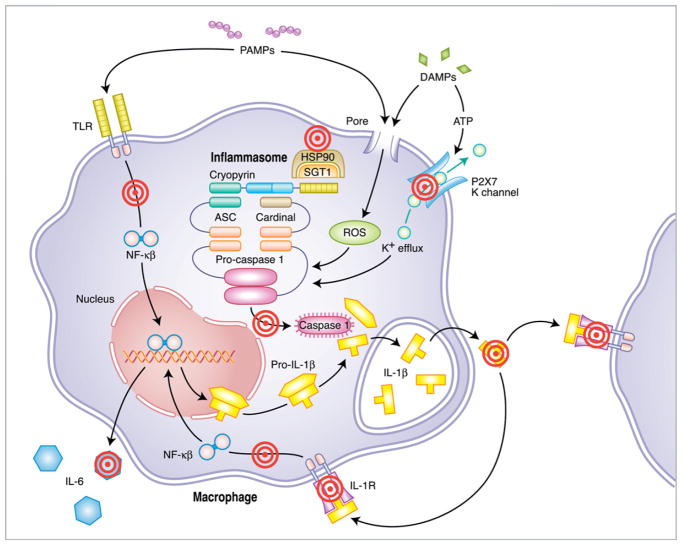

IL-1, previously known as leukocytic pyrogen, was implicated in the pathogenesis of fever at its original discovery 40 years ago.73 It has now been implicated as an important mediator in multiple inflammatory diseases.74 However, the specific mechanisms regulating the release of active IL-1β remained unclear until the recent description of the inflammasome, a protein complex that activates caspase 1, allowing for the posttranslational cleavage of pro–IL-1β to its mature releasable form.75 Once released, IL-1β exerts its effects by binding to the IL-1 receptor expressed on numerous cell types, resulting in the activation of nuclear factor κB signaling pathways that lead to an inflammatory cascade involving multiple cytokines, such as IL-6 (Fig. 2). This process is highly regulated at several levels to prevent uncontrolled IL-1–mediated inflammation, and therefore it provides a number of targets for pharmacotherapy.76

FIG. 2.

Targeting the multistepped pathways of IL-1β–mediated inflammation. The inflammasome is an intracellular protein complex that is activated by numerous pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). This activation involves several hypothesized mechanisms, including potassium efflux secondary to ATP-gated channels, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and membrane perturbation. Activation of the inflammasome leads to the cleavage and activation of caspase 1, which cleaves pro–IL-1β to its mature active form, which is subsequently released from the cell. Once released, IL-1β binds to the IL-1 receptor, leading to downstream signaling and a cascade of inflammation involving other proinflammatory cytokines. Pro–IL-1β expression is driven by Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation and autocrine IL-1 receptor activation. There are several points along this pathway that can be targeted to inhibit IL-1–mediated inflammation, including specific inflammasome triggers, common activation mechanisms, specific components of the inflammasome, inflammasome stability, caspase 1, IL-1β release, binding of IL-1β to the IL-1 receptor, IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) signaling transduction, and downstream proinflammatory cytokines. ASC, apoptosis associated speck-like protein including a caspase 1 activation and recruitment domain (CARD); Cardinal, CARD inhibitor of NF-κB activation ligand; HSP90, heat shock protein 90; NF-κB, nuclear factor κ-light chain enhancer of activated B cells; SGT1, suppressor of G2 allele of skp1.

There are numerous proposed exogenous and endogenous activators of the inflammasome, including specific bacterial and viral pathogens and specific endogenous danger signals, such as ATP,77 uric acid crystals,78 and asbestos.79 The wide variety of potential triggers suggests that there is a common mechanism that activates the inflammasome, and possibilities include reactive oxygen species,80 cell membrane perturbation, and potassium efflux. The components of the inflammasome are intracellular and include cryopyrin (also known as NALP3), adaptor proteins (ASC and Cardinal), and chaperone proteins (HSP90 and SGT1).75,81 Once cryopyrin is activated, oligomerization of these protein components occurs through several specific protein-protein interaction domains to form a multimeric complex, which binds to and activates caspase 1, allowing for the cleavage of pro–IL-1β (Fig. 2).82 The mechanisms involved in the subsequent cellular release of mature IL-1β are still unclear. Mature IL-1β can then bind to the IL-1 receptor but must compete with a natural inhibitor known as IL-1 receptor antagonist.76

IL-1–TARGETED THERAPY

The clear role of IL-1 in the host response to infection made it an obvious target for the treatment of septic shock, an acute multi-system inflammatory condition with significant morbidity and mortality. The cloning of the gene for the IL-1 receptor antagonist allowed for the development of a recombinant form, known as anakinra, as a therapeutic anti-inflammatory agent. The initial experience with IL-1 receptor antagonist in septic patients was promising, but larger trials failed to show significant efficacy in this complex, multiphase inflammatory response.83 Anakinra was later studied in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, in whom it showed statistically and clinically significant improvement in inflammatory symptoms but only modest efficacy compared with other biologic therapies. Since its approval in 2001, it has been used primarily in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who do not have an adequate response to TNF-targeted therapy.84 However, the ready availability of anakinra allowed for proof-of-concept trials in many of the autoinflammatory diseases, where it has had a major effect, despite its use being limited to off-label indications.

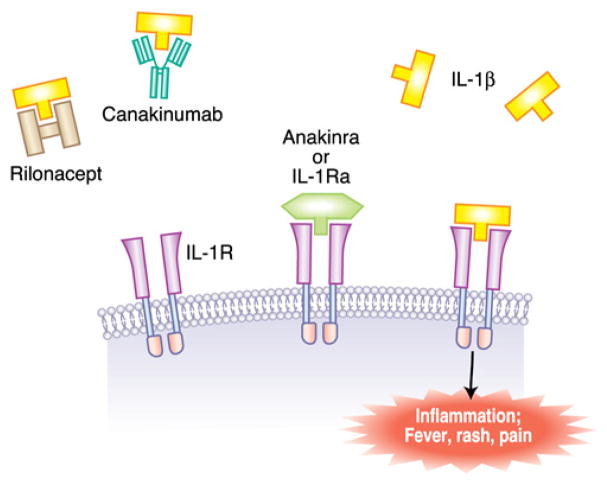

Anakinra has several pharmacologic features that might limit its effectiveness, including a short half-life requiring daily injections and common painful injection-site reactions. Therefore many physicians believed that an IL-1–targeted compound with more favorable pharmacokinetics might be more effective in blocking inflammation. This concept encouraged the development of longer-acting IL-1–targeted drugs, such as rilonacept and canakinumab, for use in inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Rilonacept is a recombinant fusion protein consisting of portions of the IL-1 receptor and the IL-1 receptor accessory protein in line with an IgG Fc region. This combination results in a drug with high affinity for IL-1β and a half-life of more than 8 days, allowing for weekly injections.85 Canakinumab is a humanized mAb to IL-1β with a half-life of more than 3 weeks and pharmacokinetic data suggesting extended effective dosing frequencies of more than 2 months (Table II).86 Both of these drugs were initially developed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, but inconsistent or modest efficacy and failure to identify biomarkers that predict response resulted in a redirection of efforts toward the orphan disease CAPS and others (Fig. 3).

TABLE II.

FDA-approved IL-1–targeted therapies

| Compound | Structure | Target | Half-life | Dosing frequency | Other features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anakinra (Kineret) | Recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist | IL-1 receptor | 4–6 h | Daily | Common painful injection-site reactions |

| Rilonacept (Arcalyst) | Fusion protein, including IL-1 receptor and IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1 TRAP) | IL-1β (also IL-1α and IL-1Ra) | 8.6 d | Weekly | Minor injection-site reactions |

| Canakinumab (Ilaris) | Humanized mAb to IL-1β | IL-1β | 28 d | 2 mo | Minimal injection-site reactions |

FIG. 3.

Mechanisms of IL-1–targeted therapy. Current therapy is directed at IL-1B, including rilonacept and canakinumab or the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) with anakinra, a recombinant form of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra).

TARGETING IL-1 IN PATIENTS WITH CAPS

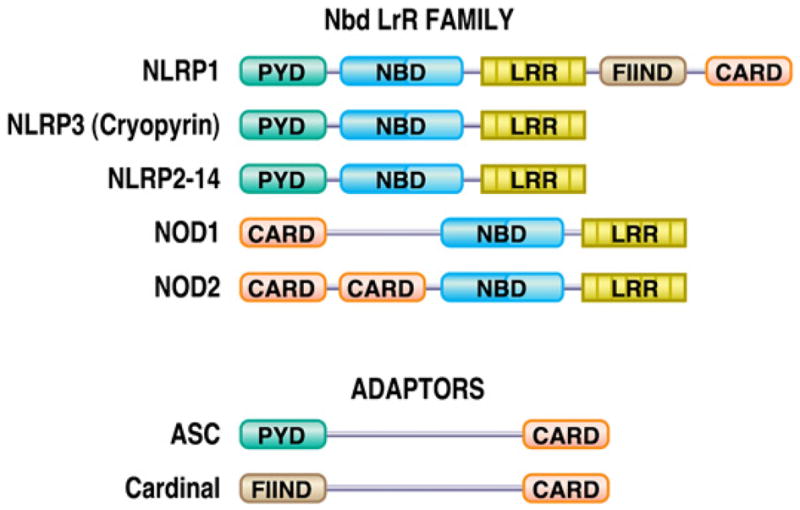

The identification of a major role for IL-1 in the pathogenesis of CAPS was the culmination of an international translational effort of several groups involving human disease genetics, genomics, molecular biology, and clinical immunology. Classic linkage analysis led to the discovery of the novel NLRP3 (CIAS1) gene as the cause of the 3 previously distinct types of CAPS, including FCAS, MWS, and NOMID.87–91 At the same time, several groups were mining the genome for genes with conserved protein domain structures with similarities to molecules regulating apoptosis and innate immune function, resulting in the identification of a new protein family known as nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeats (NLRs) that includes cryopyrin (Fig. 4).92–94 In vitro studies with recombinant cryopyrin and other NLRs demonstrated interactions with specific adaptor proteins that play a role in the activation of caspase 1 and pro–IL-1β cleavage.75,95 Ex vivo studies with mononuclear cells from patients with CAPS confirmed increased IL-1β release and provided the final preclinical studies before introduction into patients with CAPS.96,97

FIG. 4.

Protein domain structure of NLRs, including pyrin domains (PYD), nucleotide-binding domains (NBD), leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains, caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARD), and a domain with function to find (FIIND). ASC, apoptosis associated speck-like protein containing a caspase 1 activation and recruitment domain (CARD); Cardinal, CARD inhibitor of NF-κB activation ligand; NLRP, nucleotide binding domain, leucine rich repeat domain, pyrin domain; NOD, nucleotide oligomerization domain.

Anakinra in patients with CAPS

Hawkins et al98 were the first to treat patients with CAPS with anakinra, resulting in immediate reduction of MWS-related symptoms and a reduction in serum inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and SAA, which is often associated with the development of amyloidosis. Anakinra was also shown to prevent cold-induced symptoms when administered to patients with FCAS before a cold room challenge. These studies revealed a role of the skin in the pathogenesis of disease and showed that disease-associated serum IL-6 levels were completely dependent on IL-1β.65 These initial reports in patients with MWS and FCAS had an immediate effect on the treatment of patients with CAPS. However, some of the most dramatic therapeutic responses to anakinra were observed in patients with NOMID, the most severe form of CAPS.99

Since these initial reports, similar responses to anakinra have been observed in patients with CAPS to anakinra therapy with a variety of doses and treatment regimens. Some patients have required more than 3 mg/kg/d,15 whereas others have responded to doses as low as 0.3 mg/kg/d.100 Certain patients could be dosed every other day, whereas others required twice-daily dosing. Some patients with FCAS have limited anakinra therapy to specific environmental exposures or seasons to decrease the frequency of the often painful injections. All patients with CAPS have a response to therapy if treated with a high enough dose. In the one NOMID case in which anakinra was reported to be ineffective, dosing was not increased to greater than 1.6 mg/kg/d.101 In addition to improvement in daily symptoms and systemic markers of inflammation, some patients have also experienced resolution or significant improvement in long-term complications, such as hearing15,102 and vision loss103 and amyloidosis-related renal disease.16,104 However, no improvement has been observed in the abnormal bone growth characteristic of NOMID.15

Many open-label trials of anakinra therapy have now been reported in patients with CAPS, confirming persistent efficacy.16,17 The most definitive and comprehensive report of anakinra treatment in patients with CAPS is the study led by Goldbach-Mansky15 in patients with NOMID. Significant reductions in clinical symptoms and systemic inflammation was observed with anakinra therapy for more than 6 months. In addition to improved growth and quality of life, improvements in hearing and decreases in CSF pressure and cochlear or leptomeningeal enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging were also observed. Anakinra has become the standard of care for patients with NOMID, despite a lack of FDA approval and limited interest by the manufacturer. However, its use was limited in most patients with FCAS because of the requirement for frequent dosing and painful injection-site reactions (Table I).

Newer IL-1–targeted therapies in patients with CAPS

Although anakinra was able to achieve FDA approval for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, its modest efficacy and limited market share was discouraging for developers of novel IL-1 inhibitors. However, the remarkable success of IL-1 inhibition in patients with CAPS and the orphan disease development program at the FDA provided an excellent opportunity for collaborative studies between industry and the physicians that care for patients with CAPS, with a common goal of bringing effective treatments to patients in a timely fashion. Two novel biologic agents, rilonacept and canakinumab, have now been approved for CAPS (Fig. 3).

Rilonacept, also known as IL-1 TRAP, was initially studied in a pilot trial, with 5 patients with FCAS treated with weekly subcutaneous doses. This study demonstrated clear clinical and laboratory responses similar to those observed with daily anakinra105 and was the foundation for the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 44 patients with FCAS and MWS18 using a novel, validated, self-reporting daily diary to derive a key symptom score that was the primary clinical end point of the study.106 Significant differences were observed between active drug and placebo in key symptom scores, number of flares, and CRP and SAA concentrations in both the treatment and withdrawal phase of this 2-part multicenter study in the United States. The primary side effect noted was injection-site reactions in the treatment group that never resulted in drug discontinuation. There was also a trend toward increased infection frequency in the first phase of the study.18 This consistent clinical response and favorable safety profile led to FDA orphan drug approval in 2008 for patients with FCAS and MWS older than 12 years. Similar efficacy was maintained throughout an 18-month open-label extension study; however, 2 deaths were reported in this study phase (one from pneumococcal meningitis and the other from coronary artery disease) that highlight potential risks of targeting IL-1.107 Now more than 100 US patients with CAPS (approximately 30% of the estimated US CAPS population) are currently taking rilonacept.

Initial pharmacokinetic studies of canakinumab in patients with CAPS were performed with intravenous administration. Initial reports suggested prolonged clinical efficacy beyond what was expected based on the drug’s half-life. Mathematic pharmacokinetic modeling showed a feedback mechanism in which IL-1β production was driven primarily by IL-1β,108 and this model was used to determine the every 8-week subcutaneous dosing in the pivotal trial in 31 patients with MWS and NOMID.19 In this trial all active drug–treated patients remained in remission, whereas 81% of those receiving placebo had disease flares. In an open-label phase 97% of treated patients had complete or near-complete clinical response and reduction of CRP and SAA to normal levels. The only side effect noted was an increased frequency of infection, and the only reported severe adverse events included urosepsis and vertigo.19 Based on these results, the FDA approved canakinumab in 2009 for patients with FCAS and MWS older than 4 years. Preliminary results of an open-label extension study suggest continued effectiveness. Studies of canakinumab in patients with NOMID are underway (Table 1).

IL-1–TARGETED THERAPY IN OTHER AUTOINFLAMMATORY DISEASES

The successful use of IL-1 inhibitors in patients with CAPS and translational studies suggesting a role for IL-1 in other autoinflammatory diseases has prompted its use in the other inherited autoinflammatory syndromes and several more common autoinflammatory disorders. Anakinra has been used to prevent attacks and reduce systemic inflammatory markers in patients with colchicine-resistant FMF,20–25 hyper-IgD syndrome,26–28 and even etanercept-resistant TRAPS.14,29,30 Similar remarkable responses were also reported in patients with Blau syndrome,31,32 pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne6,33,34 and deficiency of IL-1 receptor antagonist.5,6 Anakinra has also been shown to be effective during acute gout episodes,35,36 chronic gout,35 and pseudogout37,38 and in the management of Schnitzler syndrome,39–45 systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis,46–48 and adult-onset Still disease.49–56 Rilonacept was reported to be effective at reducing chronic gout associated joint pain, as well as CRP levels, in a recent pilot study.57 Rilonacept and canakinumab are currently in clinical trials for systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, with promising results (Table I).

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF TARGETED BIOLOGIC THERAPIES

Many of the anti-inflammatory targeted drugs have ideal therapeutic properties of efficient inhibition of disease-related pathways with limited off-target adverse events. However, clinical experience with anticytokine drugs has revealed on-target side effects and shown the important roles of specific cytokines in the host response to infection. Although drugs inhibiting the TNF-α pathway are now used extensively for the therapy of rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, increased rates of opportunistic infections due to mycobacteria and fungi, and mild-to-severe bacterial and viral infections have been observed in large trials and during postmarketing surveillance studies in these populations. However, many of these infections have been associated with the concomitant use of other immune-modulating drugs and might be related to infections associated with the underlying disease.58 Similarly, slightly increased rates of mild-to-severe bacterial and viral infections have been observed in large trials and during postmarketing surveillance with anakinra in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but there does not appear to be an increased risk from opportunistic infections.58 It is not clear whether the safety experience with newer longer acting anti–IL-1–targeted drugs or with any biologic therapy in autoinflammatory diseases, in which there might be fewer concomitant therapies, will be similar to what has been observed in these large diverse populations. Increased rates of upper respiratory tract infections and reports of severe bacterial infections (meningitis and urosepsis) have been observed in the small CAPS trials with both rilonacept and canakinumab. All of these biologic drugs are injectable and can be associated with injection-site reactions. However, this is much less of a problem with the newer IL-1 medicines.

NOVEL THERAPEUTIC TARGETS FOR AUTOINFLAMMATORY DISEASES

The elucidation of the multistep mechanisms involved in IL-1β release reveals a number of possible targets at different steps in the pathway (Fig. 2). Studies demonstrating the involvement of ATP,77,59 potassium efflux,60 uric acid,78 or reactive oxygen species79,80 in the activation of the inflammasome point to a role for drugs targeting purine receptors (P2X7 inhibitors), potassium channels (glyburide like compounds), or uric acid levels (uricosuric agents). Drugs with membrane-stabilizing function or antioxidant properties might also be successful in blocking steps upstream of the inflammasome. These drugs could be very effective at blocking several common inflammasome-mediated disorders but might not have a role in the treatment of autoinflammatory disorders because of mutations in the inflammasome pathway resulting in hyperactive or constitutive activation that is not dependent on upstream activators.

The identification of heat shock protein chaperones in the inflammasome complex suggests a role for drugs targeting these molecules81 or other therapies that might affect inflammasome stability or function. Caspase 1 inhibitors are currently in development and have shown promise in CAPS ex vivo models97 but have been limited by side effects and dosing issues for in vivo therapy. Theoretically, targeting the inflammasome directly could have the best efficacy and safety profile for autoinflammatory diseases, such as CAPS, because of the effect on other inflammasome-mediated cytokines, such as IL-18; however, the existence of several different inflammasomes consisting of closely related NLRs might require significant specificity.

The complex mechanisms of lysosomal IL-1β release or signal transduction pathways of IL-1 receptor signaling (eg, mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal regulated kinase or NF κB) also provide a number of potential therapeutic targets, which could have effects on additional cytokine-mediated inflammation. Finally, biologic agents targeting downstream cytokines, such as IL-6, might also have a role in the therapy of autoinflammatory diseases (Fig. 2). Each of these approaches might have certain advantages over currently available therapy, including oral routes, lower costs, or better side effect profiles. It is also possible that approaches involving combination therapies will have the most success.

SUMMARY

The recent recognition of a new class of immunologic disorders known as autoinflammatory diseases has changed the way we look at pathologic inflammation and allowed for a better understanding of the mechanisms regulating the innate immune system. This disease category has now expanded from the original rare, inherited, recurrent fever syndromes to include much more common diseases. Translational research concerning the single-gene autoinflammatory disorders has not only improved our knowledge of pathophysiology but has rapidly led to improved diagnosis and therapy of the patients with these diseases and holds promise to improve future treatment for more complex auto-inflammatory disease, such as gout and systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The availability of targeted therapies for proinflammatory cytokines, such as anakinra for IL-1β, allowed for hypothesis testing and drove the development of newer IL-1β–directed therapies, including rilonacept and canakinumab. Future therapies will take advantage of our expanding knowledge of the inflammatory mechanisms involved in both rare and common autoinflammatory diseases.

What do we know?

Autoinflammatory disorders are primarily driven by the innate immune system and include rare inherited syndromes and more common and genetically complex inflammatory diseases.

Translational research has advanced our understanding of the cause of inherited autoinflammatory syndromes and has led to effective targeted therapy with significant clinical effect.

Colchicine is still the standard of care for FMF and is used widely around the world.

IL-1 is one of the central mediators of autoinflammatory diseases and is the target of 3 approved biologic therapies, including anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab.

What is still unknown?

The underlying genetic basis and pathophysiologic mechanisms for many inherited autoinflammatory syndromes

Specific mechanisms underlying the activation of the inflammasome

The long-term efficacy and safety of IL-1–targeted therapies

The role of novel upstream and downstream inflammasome-targeted therapies in the future

Abbreviations used

- CAPS

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- FCAS

Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- FMF

Familial Mediterranean fever

- MWS

Muckle-Wells syndrome

- NLR

Nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat

- NOMID

Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease

- SAA

Systemic amyloid A

- TRAPS

TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome

References

- 1.McDermott MF, Aksentijevich I, Galon J, McDermott EM, Ogunkolade BW, Centola M, et al. Germline mutations in the extracellular domains of the 55 kDa TNF receptor, TNFR1, define a family of dominantly inherited autoinflammatory syndromes. Cell. 1999;97:133–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDermott MF, Aksentijevich I. The autoinflammatory syndromes. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:511–6. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masters SL, Simon A, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease*. Ann Rev Immunol. 2009;27:621–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brydges SD, Mueller JL, McGeough MD, Pena CA, Misaghi A, Gandhi C, et al. Inflammasome-mediated disease animal models reveal roles for innate but not adaptive immunity. 2009;30:875–87. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aksentijevich I, Masters SL, Ferguson PJ, Dancey P, Frenkel J, van Royen-Kerkhoff A, et al. An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2426–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy S, Jia S, Geoffrey R, Lorier R, Suchi M, Broeckel U, et al. An autoinflammatory disease due to homozygous deletion of the IL1RN locus. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2438–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hull KM, Aksentijevich I, Singh HK. Efficacy of etanercept for the treatment of patients with TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) [abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(suppl):S378. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinarello C, Wolff S, Goldfinger S, Dale D, Alling D. Colchicine therapy for familial Mediterranean fever. A double-blind trial. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:934–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197410312911804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein R, Schwabe A. Prophylactic colchicine therapy in familial Mediterranean fever. A controlled, double-blind study. Ann Intern Med. 1974;81:792–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-81-6-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zemer D, Revach M, Pras M, Modan B, Schor S, Sohar E, et al. A controlled trial of colchicine in preventing attacks of familial Mediterranean fever. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:932–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197410312911803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majeed HA, Carroll JE, Khuffash FA, Hijazi Z. Long-term colchicine prophylaxis in children with familial Mediterranean fever (recurrent hereditary polyserositis) J Pediatr. 1990;116:997–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80667-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zemer D, Livneh A, Danon YL, Pras M, Sohar E. Long-term colchicine treatment in children with familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:973–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drewe E, McDermott EM, Powell PT, Isaacs JD, Powell RJ. Prospective study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1B fusion protein, and case study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A fusion protein, in tumour necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): clinical and laboratory findings in a series of seven patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:235–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon A, Bodar EJ, van der Hilst JC, van der Meer JW, Fiselier TJ, Cuppen MP, et al. Beneficial response to interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in traps. Am J Med. 2004;117:208–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, Gelabert A, Jones J, Rubin BI, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:581–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leslie KS, Lachmann HJ, Bruning E, McGrath JA, Bybee A, Gallimore JR, et al. Phenotype, genotype, and sustained response to anakinra in 22 patients with auto-inflammatory disease associated with CIAS-1/NALP3 mutations. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1591–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.12.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross JB, Finlayson LA, Klotz PJ, Langley RG, Gaudet R, Thompson K, et al. Use of anakinra (Kineret) in the treatment of familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome with a 16-month follow-up. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:8–16. doi: 10.2310/7750.2008.07050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman HM, Throne ML, Amar NJ, Sebai M, Kivitz AJ, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilonacept (interleukin-1 Trap) in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: results from two sequential placebo-controlled studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2443–52. doi: 10.1002/art.23687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Leslie KS, Hachulla E, Quartier P, et al. Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2416–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser C, Pohl G, Haslinger I, Knapp S, Rowczenio D, Russel T, et al. Successful treatment of familial Mediterranean fever with anakinra and outcome after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:676–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belkhir R, Moulonguet-Doleris L, Hachulla E, Prinseau J, Baglin A, Hanslik T. Treatment of familial Mediterranean fever with anakinra. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:825–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gattringer R, Lagler H, Gattringer KB, Knapp S, Burgmann H, Winkler S, et al. Anakinra in two adolescent female patients suffering from colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever: effective but risky. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:912–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuijk LM, Govers AMAP, Hofhuis WJD, Frenkel J. Effective treatment of a colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever patient with anakinra. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1545–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitroulis I, Papadopoulos VP, Konstantinidis T, Ritis K. Anakinra suppresses familial Mediterranean fever crises in a colchicine-resistant patient. Neth J Med. 2008;66:489–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roldan R, Ruiz AM, Miranda MD, Collantes E. Anakinra: new therapeutic approach in children with familial Mediterranean fever resistant to colchicine. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:504–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodar EJ, van der Hilst JC, Drenth JP, van der Meer JW, Simon A. Effect of etanercept and anakinra on inflammatory attacks in the hyper-IgD syndrome: introducing a vaccination provocation model. Neth J Med. 2005;63:260–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cailliez M, Garaix F, Rousset-Rouvière C, Bruno D, Kone-Paut I, Sarles J, et al. Anakinra is safe and effective in controlling hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D syndrome-associated febrile crisis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:763. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigante D, Ansuini V, Bertoni B, Pugliese A, Avallone L, Federico G, et al. Treatment with anakinra in the hyperimmunoglobulinemia D/periodic fever syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2006;27:97–100. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gattorno M, Pelagatti MA, Meini A, Obici L, Barcellona R, Federici S, et al. Persistent efficacy of anakinra in patients with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1516–20. doi: 10.1002/art.23475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sacré K, Brihaye B, Lidove O, Papo T, Pocidalo MA, Cuisset L, et al. Dramatic improvement following interleukin 1beta blockade in tumor necrosis factor receptor-1-associated syndrome (TRAPS) resistant to anti-TNF-alpha therapy. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:357–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aróstegui JI, Arnal C, Merino R, Modesto C, Antonia Carballo M, Moreno P, et al. NOD2 gene-associated pediatric granulomatous arthritis: clinical diversity, novel and recurrent mutations, and evidence of clinical improvement with interleukin-1 blockade in a Spanish cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3805–13. doi: 10.1002/art.22966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin TM, Zhang Z, Kurz P, Rose CD, Chen H, Lu H, et al. The NOD2 defect in Blau syndrome does not result in excess interleukin-1 activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:611–8. doi: 10.1002/art.24222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brenner M, Ruzicka T, Plewig G, Thomas P, Herzer P. Targeted treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum in PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne) syndrome with the recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1199–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dierselhuis MP, Frenkel J, Wulffraat NM, Boelens JJ. Anakinra for flares of pyogenic arthritis in PAPA syndrome. Rheumatology. 2005;44:406. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGonagle D, Tan AL, Shankaranarayana S, Madden J, Emery P, McDermott MF. Management of treatment resistant inflammation of acute on chronic tophaceous gout with anakinra. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1683–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.073759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R28. doi: 10.1186/ar2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Announ N, Palmer G, Guerne P-A, Gabay C. Anakinra is a possible alternative in the treatment and prevention of acute attacks of pseudogout in end-stage renal failure. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:424–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGonagle D, Tan AL, Madden J, Emery P, McDermott MF. Successful treatment of resistant pseudogout with anakinra. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:631–3. doi: 10.1002/art.23119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Koning HD, Bodar EJ, Simon A, van der Hilst JCH, Netea MG, van der Meer JWM. Beneficial response to anakinra and thalidomide in Schnitzler’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:542–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.045245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilson M, Abad S, Larroche C, Dhote R. Treatment of Schnitzler’s syndrome with anakinra. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stefan WS, Markus G, Thomas AL, Gisela B. Prompt response of refractory Schnitzler syndrome to treatment with anakinra. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(suppl):S120–S102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devlin LA, Wright G, Edgar JD. A rare cause of a common symptom, anakinra is effective in the urticaria of Schnitzler syndrome: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:348. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dybowski F, Sepp N, Bergerhausen HJ, Braun J. Successful use of anakinra to treat refractory Schnitzler’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:354–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elisabeth E, Maike Ml, Inga K, Jochen B, Thomas S. Schnitzler syndrome: treatment failure to rituximab but response to anakinra. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:361–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Rachamalla R, Saini SS. Remission of Schnitzler syndrome after treatment with anakinra. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:617–9. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gattorno M, Piccini A, Lasiglië D, Tassi S, Brisca G, Carta S, et al. The pattern of response to anti-interleukin-1 treatment distinguishes two subsets of patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1505–15. doi: 10.1002/art.23437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lequerre T, Quartier P, Rosellini D, Alaoui F, De Bandt M, Mejjad O, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) treatment in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis or adult onset Still disease: preliminary experience in France. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:302–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohlsson V, Baildam E, Foster H, Jandial S, Pain C, Strike H, et al. Anakinra treatment for systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SOJIA) Rheumatology. 2008;47:555–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fitzgerald AA, Leclercq SA, Yan A, Homik JE, Dinarello CA. Rapid responses to anakinra in patients with refractory adult-onset Still’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1794–803. doi: 10.1002/art.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kötter I, Wacker A, Koch S, Henes J, Richter C, Engel A, et al. Anakinra in patients with treatment-resistant adult-onset Still’s disease: four case reports with serial cytokine measurements and a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;37:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudinskaya A, Trock DH. Successful treatment of a patient with refractory adult-onset still disease with anakinra. J Clin Rheumatol. 2003;9:330–2. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000089966.48691.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Godinho FMV, Santos MJP, da Silva JC. Refractory adult onset Still’s disease successfully treated with anakinra. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:647–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.026617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalliolias GD, Georgiou PE, Antonopoulos IA, Andonopoulos AP, Liossis S-NC. Anakinra treatment in patients with adult-onset Still’s disease is fast, effective, safe and steroid sparing: experience from an uncontrolled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:842–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maier J, Birkenfeld G, Pfirstinger J, Scholmerich J, Fleck M, Bruhl H. Effective treatment of steroid refractory adult-onset Still’s disease with anakinra. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:939–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Priori R, Ceccarelli F, Barone F, Iagnocco A, Valesini G. Clinical, biological and sonographic response to IL-1 blockade in adult-onset Still’s disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:933–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Youssef J, Lazaro E, Blanco P, Viallard JF. Blockade of interleukin 1 receptor in Still’s disease affects activation of peripheral T-lymphocytes. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2453–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terkeltaub R, Sundy JS, Schumacher HR, Murphy F, Bookbinder S, Biedermann S, et al. The IL-1 inhibitor rilonacept in treatment of chronic gouty arthritis: results of a placebo-controlled, monosequence crossover, nonrandomized, single-blind pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1613–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Botsios C. Safety of tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-1 blocking agents in rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duncan JA, Bergstralh DT, Wang Y, Willingham SB, Ye Z, Zimmermann AG, et al. Cryopyrin/NALP3 binds ATP/dATP, is an ATPase, and requires ATP binding to mediate inflammatory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8041–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611496104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brydges S, Kastner DL. The systemic autoinflammatory diseases: inborn errors of the innate immune system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;305:127–60. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29714-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoffman HM, Simon A. Recurrent febrile syndromes—what a rheumatologist needs to know. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:249–56. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ben-Chetrit E, Backenroth R. Amyloidosis induced, end stage renal disease in patients with familial Mediterranean fever is highly associated with point mutations in the MEFV gene. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:146–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.2.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dode C, Cuisset L, Delpech M, Grateau G. TNFRSF1A-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS) and renal amyloidosis. J Nephrol. 2003;16:435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoffman HM, Rosengren S, Boyle DL, Cho JY, Nayar J, Mueller JL, et al. Prevention of cold-associated acute inflammation in familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome by interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Lancet. 2004;364:1779–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17401-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ben-Chetrit E, Levy M. Colchicine: 1998 update. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;28:48–59. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoffman HM, Patel DD. Genomic-based therapy: targeting interleukin-1 for auto-inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:345–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goldfinger S. Colchicine for familial Mediterranean fever. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:1302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197212212872514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dinarello CA, Chusid MJ, Fauci AS, Gallin JI, Dale DC, Wolff SM. Effect of prophylactic colchicine therapy on leukocyte function in patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1976;19:618–22. doi: 10.1002/art.1780190315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molad Y. Update on colchicine and its mechanism of action. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002;4:252–6. doi: 10.1007/s11926-002-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drewe E, Powell RJ, McDermott EM. Comment on: failure of anti-TNF therapy in TNF receptor 1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) Rheumatology. 2007;46:1865–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nedjai B, Hitman G, Quillinan N, Coughlan R, Church L, McDermott MF, et al. Proinflammatory action of the antiinflammatory drug infliximab in tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:619–25. doi: 10.1002/art.24294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dinarello CA, Goldin NP, Wolff SM. Demonstration and characterization of two distinct human leukocytic pyrogens. J Exp Med. 1974;139:1369–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.6.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dinarello CA. The IL-1 family and inflammatory diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(suppl):S1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dinarello CA. Blocking IL-1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1355–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O’Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–32. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cassel SL, Eisenbarth SC, Iyer SS, Sadler JJ, Colegio OR, Tephly LA, et al. The Nalp3 inflammasome is essential for the development of silicosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9035–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803933105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mayor A, Martinon F, De Smedt T, Petrilli V, Tschopp J. A crucial function of SGT1 and HSP90 in inflammasome activity links mammalian and plant innate immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:497–503. doi: 10.1038/ni1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Ann Rev Immunol. 2009;27:229–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van der Poll T, van Deventer SJ. Cytokines and anticytokines in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999;13:413–26. ix. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mertens M, Singh JA. Anakinra for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1118–25. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoffman HM. Rilonacept for the treatment of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:519–31. doi: 10.1517/14712590902875518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Church LD, McDermott MF. Canakinumab, a fully-human mAb against IL-1beta for the potential treatment of inflammatory disorders. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2009;11:81–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein cause familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:301–5. doi: 10.1038/ng756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aganna E, Martinon F, Hawkins PN, Ross JB, Swan DC, Booth DR, et al. Association of mutations in the NALP3/CIAS1/PYPAF1 gene with a broad phenotype including recurrent fever, cold sensitivity, sensorineural deafness, and AA amyloidosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2445–52. doi: 10.1002/art.10509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, Chae JJ, Watford WT, Hofmann SR, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3340–8. doi: 10.1002/art.10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dode C, Le Du N, Cuisset L, Letourneur F, Berthelot JM, Vaudour G, et al. New mutations of CIAS1 that are responsible for Muckle-Wells syndrome and familial cold urticaria: a novel mutation underlies both syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1498–506. doi: 10.1086/340786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Feldmann J, Prieur AM, Quartier P, Berquin P, Certain S, Cortis E, et al. Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:198–203. doi: 10.1086/341357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bertin J, DiStefano PS. The PYRIN domain: a novel motif found in apoptosis and inflammation proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:1273–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Harton JA, Linhoff MW, Zhang J, Ting JP. Cutting edge: CATERPILLER: a large family of mammalian genes containing CARD, pyrin, nucleotide-binding, and leucine-rich repeat domains. J Immunol. 2002;169:4088–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tschopp J, Martinon F, Burns K. NALPs: a novel protein family involved in inflammation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:95–104. doi: 10.1038/nrm1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Manji GA, Wang L, Geddes BJ, Brown M, Merriam S, Al-Garawi A, et al. PY-PAF1: A PYRIN-containing Apaf1-like protein that assembles with ASC and regulates activation of NF-κB. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11570–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, McDermott MF, Hawkins PN, Tschopp J. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20:319–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stack JH, Beaumont K, Larsen PD, Straley KS, Henkel GW, Randle JC, et al. IL-converting enzyme/caspase-1 inhibitor VX-765 blocks the hypersensitive response to an inflammatory stimulus in monocytes from familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome patients. J Immunol. 2005;175:2630–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, McDermott MF. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in the Muckle-Wells syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2583–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200306193482523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frenkel J, Wulffraat NM, Kuis W. Anakinra in mutation-negative NOMID/CINCA syndrome: comment on the articles by Hawkins et al and Hoffman and Patel. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3738–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, Aganna E, McDermott MF. Spectrum of clinical features in Muckle-Wells syndrome and response to anakinra. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:607–12. doi: 10.1002/art.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Matsubara T, Hasegawa M, Shiraishi M, Hoffman HM, Ichiyama T, Tanaka T, et al. A severe case of chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2314–20. doi: 10.1002/art.21965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rynne M, Maclean C, Bybee A, McDermott MF, Emery P. Hearing improvement in a patient with variant Muckle-Wells syndrome in response to interleukin 1 receptor antagonism. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:533–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Alexander T, Klotz O, Feist E, Ruther K, Burmester GR, Pleyer U. Successful treatment of acute visual loss in Muckle-Wells syndrome with interleukin 1 receptor antagonist. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1245–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thornton BD, Hoffman HM, Bhat A, Don B. Successful treatment of renal amyloidosis due to familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome using an interleukin 1 receptor antagonist. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:477–81. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Goldbach-Mansky R, Shroff SD, Wilson M, Snyder C, Plehn S, Barham B, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the long-acting interleukin-1 inhibitor rilonacept (interleukin-1 trap) in patients with familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2432–42. doi: 10.1002/art.23620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hoffman HM, Wolfe F, Belomestnov P, Mellis SJ. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: development of a patient-reported outcomes instrument to assess the pattern and severity of clinical disease activity. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2531–43. doi: 10.1185/03007990802297495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hoffman HM, Throne ML, Amar NJ, Sebai M, Kivitz AJ, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilonacept (interleukin-1 trap) in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: results from two sequential placebo-controlled studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2443–52. doi: 10.1002/art.23687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lachmann HJ, Lowe P, Felix SD, Rordorf C, Leslie K, Madhoo S, et al. In vivo regulation of interleukin 1β in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1029–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]