Abstract

The unfolded protein response (UPR) regulates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis and protects cells from ER stress. IRE1α is a central regulator of the UPR that activates the transcription factor XBP1s through an unconventional splicing mechanism using its endoribonuclease activity. IRE1α also cleaves certain mRNAs containing XBP1-like secondary structures to promote the degradation of these mRNAs, a process known as regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD). We show here that the mRNA of CReP/Ppp1r15b, a regulatory subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) phosphatase, is a RIDD substrate. eIF2α plays a central role in the integrated stress response by mediating the translational attenuation to decrease the stress level in the cell. CReP expression was markedly suppressed in XBP1-deficient mice livers due to hyperactivated IRE1α. Decreased CReP expression caused the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation and the attenuation of protein synthesis in XBP1-deficient livers. ER stress also suppressed CReP expression in an IRE1α-dependent manner, which increased eIF2α phosphorylation and consequently attenuated protein synthesis. Taken together, the results of our study reveal a novel function of IRE1α in the regulation of eIF2α phosphorylation and the translational control.

INTRODUCTION

Overloading with excess cargo proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) exceeding its folding capacity triggers the ER stress response, which is also known as the unfolded protein response (UPR) (1, 2). UPR is comprised of several intracellular signaling pathways that promote the restoration of the ER homeostasis through multiple mechanisms including the induction of ER chaperones, the activation of ER-associated degradation (ERAD) of misfolded proteins, and and inhibition of protein synthesis (1, 3). The UPR consists of three branches that are initiated by ER transmembrane sensor proteins: inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) (3, 4). These UPR branches are simultaneously activated by ER stress in parallel and cooperatively resolve the stress.

IRE1α is an evolutionarily well-conserved protein that possesses Ser/Thr kinase and endoribonuclease activities. IRE1α is oligomerized and autophosphorylated in response to ER stress and induces an unconventional splicing of XBP1 mRNA using its endoribonuclease activity to generate the transcription factor XBP1s, which plays a central role in the UPR (5). XBP1s increases the protein folding capacity of ER by activating the transcription of ER chaperones and other genes involved in the protein secretory pathway (6–8). IRE1α also cleaves several mRNAs triggering the degradation of the cleaved mRNA by cytosolic nucleases, a pathway known as regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD) (9–11). Based on the finding that a majority of the RIDD substrates in D. melanogaster were mRNAs encoding transmembrane and secretory proteins, RIDD was initially proposed as a mechanism to reduce the ER stress by decreasing the input of the secretory cargo proteins into ER (12). However, subsequent studies in mammalian cells revealed that RIDD targets exhibited a wide range of subcellular localization and biological functions and varied in different cell types (9–11, 13–17). A growing number of studies demonstrate that RIDD plays a role in drug and lipid metabolism in the liver (13, 14), neural regulation of vascular regeneration (15), antigen presentation function of CD8α+ dendritic cells (16), insulin synthesis in β cells (11, 17), and ER stress-induced cell death (11).

PERK-mediated phosphorylation of the α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) causes the inhibition of general protein translation, which is expected to decrease the burden on the ER (18–20). Increased eIF2α phosphorylation represses the guanine nucleotide-exchange function of eIF2B, interfering with the formation of the eIF2/GTP/Met-tRNAi ternary complex required for translation initiation (21, 22). eIF2α phosphorylation is also regulated by phosphatase complexes which are composed of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1c) and a regulatory subunit, GADD34 or CReP (23, 24). CReP is a constitutively expressed regulatory subunit which is believed to determine the basal level of eIF2α phosphorylation, whereas ER stress-inducible GADD34 is important for the negative feedback regulation of eIF2α phosphorylation in the recovery phase of the stress response (23, 24). GADD34 is transcriptionally activated by ATF4 which is induced by PERK-eIF2α pathway and stimulates the dephosphorylation of eIF2α during prolonged ER stress (25). On the other hand, it remains poorly understood whether CReP expression and activity are regulated by external and internal signals, and if so, how they impact eIF2α phosphorylation.

In this study, we identified CReP mRNA as a RIDD target. We also demonstrated that IRE1α-mediated degradation of CReP mRNA contributed to the increase in eIF2α phosphorylation during ER stress. Hence, ER stress increased eIF2α phosphorylation via two distinct mechanisms: increased phosphorylation by PERK and decreased dephosphorylation due to IRE1α-mediated CReP downregulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Xbp1flox (26) and Ern1flox (27) mice carrying floxed Xbp1 and Ern1 (IRE1α) genes were crossed with albumin-cre transgenic mice [C57BL/6-Tg(Alb-cre)21Mgn/J mice; Jackson Laboratory] to generate hepatocyte-specific XBP1 (Xbp1Δ) and IRE1α (Ire1Δ) knockout mice. Tunicamycin was diluted in 150 mM dextrose at 200 μg/ml and intraperitoneally injected into mice at 2 mg/kg (body weight). Animal experiments were approved and performed according to the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Cornell Medical College. In vivo delivery of lipidoid-formulated small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) into XBP1 knockout mice has been previously described (13, 14).

Western blotting.

Liver tissues were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50 mM NaF) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). The homogenates were centrifuged twice at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants were analyzed as total lysates. Liver nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (26). Briefly, liver tissues were homogenized in homogenization buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.3 M sucrose, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.74 mM spermidine, protease inhibitors) and mixed with 2 volumes of cushion buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.1 mM EGTA, 2.2 M sucrose, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.74 mM spermidine, 1 μg of aprotinin/ml, 2 μg of leupeptin/ml). The mixture was overlaid on a 2-ml cushion buffer in a 14-by-89-mm tube and centrifuged at 77,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C in a Beckman SW41 Ti rotor. Precipitated nuclei were resuspended in RIPA buffer, briefly sonicated, and cleared by centrifugation for 5 min. Total protein lysates of cultured cells were prepared in RIPA buffer. Protein lysates were resolved on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. For Phos-tag gel electrophoresis, Phos-tag reagent (NARD Institute, Ltd.) and MnCl2 were added to the gel to final concentrations of 12.5 and 100 μM, respectively. The membrane was blocked in 5% nonfat milk in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in the blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed with TBST, incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies), developed using chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico; Pierce), and visualized using a digital imaging system (Fluorchem E; ProteinSimple). Individual bands were quantified with AlphaView software and normalized by signals of Hsp90. The primary antibodies used were anti-CReP (14634-1-AP; Proteintech), anti-eIF2α (sc-11386; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-phospho-eIF2α (catalog no. 9721; Cell Signaling), anti-Hsp90 (sc-7947; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-IRE1α (catalog no. 3294; Cell Signaling), anti-lamin B1 (sc-56145; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-PERK (catalog no. 3192; Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-PERK (catalog no. 3179; Cell Signaling), anti-GCN2 (catalog no. 3302; Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-GCN2 (AF87605; R&D Systems), and anti-PKR (sc-6282; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-phospho-PKR (sc-101784; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies and rabbit serum raised against a synthetic XBP1 peptide (EDTFANELFPQLISV).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted using Qiazol reagent (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR green fluorescent reagent and the Mx3005P system (Stratagene). The relative amounts of mRNAs were calculated from the threshold cycle (CT) values by using β-actin as a control.

Cell culture and transfection.

Hepa1-6, HeLa, HEK293T, IRE1α−/−, IRE1α−/−; IRE1α-HA, PERK−/−, and HRI−/− murine embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. IRE1α−/−; IRE1α-HA cells were generated by transducing IRE1α−/− cells with MSCVhygro-IRE1α-HA retrovirus and selected with 200 μg of hygromycin/ml, as described previously (28). Cells were transfected with plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For siRNA knockdown, Hepa1-6 cells were transfected with IRE1α (target sequences, 5′-AUGCCGAAGUUCAGAUGGADTSDT-3′), CReP (target sequences, 5′-GUAUGAAACGGCUAGAAUU-3′), or control luciferase siRNA using the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) and harvested 72 h later.

Lentiviral shRNA.

pLKO.1puro lentiviral vectors containing shRNAs for mouse XBP1 (target sequences, 5′-CCAGGAGTTAAGAACACGCTT-3′), mouse CReP (target sequences, 5′-CCAACTCCGATAATGAAGAAT-3′) were obtained from Broad Institute. pLKO.1 shRNA vector for human CReP was purchased from Open Biosystems (RHS4533-EG84919). Lentiviruses were produced by transient transfectoion into HEK293T cells of the vectors and pCMV Δ8.9 and pMD VSV-G packaging plasmids. Target cells were infected with the viruses in the presence of 8 μg of Polybrene/ml and selected with 3 μg of puromycin/ml.

Cloning of CReP plasmid.

CReP cDNA was PCR amplified from pYX-Asc CReP (catalog no. BC058078; Open Biosystems) plasmid which contained a T nucleotide deletion in the coding region (nucleotide 1817) and inserted into pCMV-SPORT6 plasmid. The T nucleotide deletion was corrected by QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

In vitro IRE1α-mediated mRNA cleavage assays.

Cleavage of in vitro-transcribed CReP mRNA by recombinant IRE1α was tested as described previously (17). Briefly, pCMV-SPORT6 CReP plasmid was linearized by BmgBI digestion and incubated with SP6 polymerase (Invitrogen) to produce CReP RNA. The in vitro-transcribed RNAs were incubated with recombinant IRE1α protein containing the cytosolic domain of human IRE1α, resolved on 1.2% denaturing agarose gel containing 0.67% formaldehyde, and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

GEF activity of eIF2B and polysome analysis.

Guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity was measured as previously described using eIF2 purified from rat liver as a substrate (29). Briefly, eIF2 was incubated with [3H]GDP, and the resulting eIF2-[3H]GDP complex was stabilized by the addition of MgCl2. The complex was incubated with cell homogenate and nonradioactive GDP, and at various times aliquots of the mixture were removed and filtered through nitrocellulose disks. The amount of eIF2-[3H]GDP complex bound to the disks was assessed by liquid scintillation counting. eIF2B activity was calculated as the rate of exchange of [3H]GDP for nonradioactive GDP. Polysome analyses were performed by centrifuging cell homogenates through linear sucrose gradients, followed by fractionation of the gradients as described previously (29).

Metabolic labeling.

HeLa cells were transfected with CReP (siGENOME SMARTpool; Dharmacon) or control luciferase siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Life Technologies). After 72 h of transfection, the cells were pulse-labeled with 100 μCi of [35S]methionine/ml in complete medium for various times. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

RESULTS

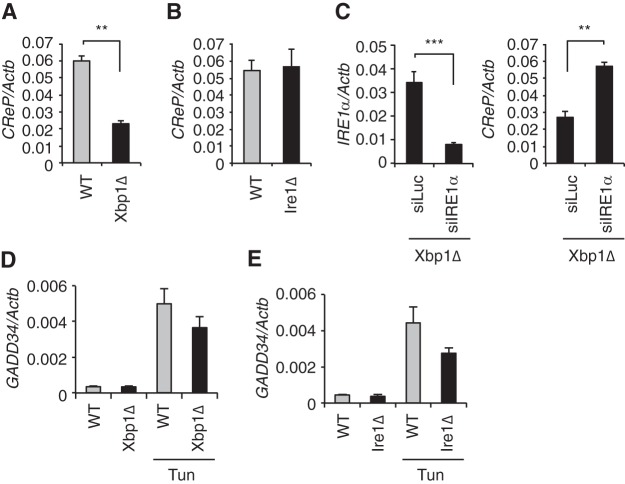

Decreased expression of CReP, a regulatory subunit of eIF2α phosphatase, in XBP1 knockout liver.

We previously demonstrated that the loss of XBP1 increased both the activity and the abundance of IRE1α in the liver presumably due to the decreased expression of XBP1-dependent ER chaperones such as ERdj4 and BiP (26). A comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles in livers from XBP1- and IRE1α knockout mice identified a group of RIDD target mRNAs that are cleaved by IRE1α (13). Interestingly, constitutive repressor of eIF2α phosphorylation (CReP/Ppp1r15b) mRNA was identified as a potential RIDD target, since its abundance was decreased in XBP1 knockout (Fig. 1A) but not in IRE1α knockout livers compared to wild-type (WT) controls (Fig. 1B). Silencing of IRE1α in XBP1 knockout livers restored the expression of CReP mRNA to WT level (Fig. 1C). In contrast, neither basal nor tunicamycin-induced GADD34 expression were affected by the loss of XBP1 or IRE1α (Fig. 1D and E), indicating the specific regulation of CReP mRNA turnover by IRE1α.

FIG 1.

Hyperactivated IRE1α suppressed CReP expression in XBP1-deficient liver. (A and B) qRT-PCR analysis of CReP mRNA in liver of Xbp1Δ, Ire1Δ, and the littermate control (WT) mice (n = 3 to 5 mice per group). (C) Hepatic IRE1α and CReP mRNA levels measured 8 days after siRNA injection of Xbp1LKO mice (n = 3 to 5 per group). (D and E) Mice were untreated or injected with tunicamycin 6 h prior to sacrifice. GADD34 mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

CReP mRNA is a RIDD target.

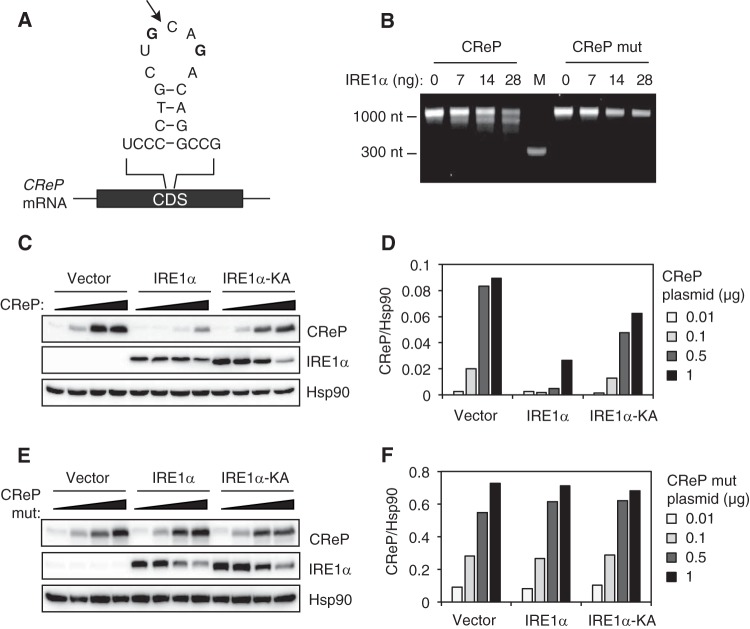

Analysis of the secondary structure of mouse CReP mRNA predicted the presence of an XBP1-like hairpin structure containing the consensus sequences (5′-CUGCAG-3′) required for the cleavage by IRE1α (Fig. 2A). To directly demonstrate that CReP mRNA was cleaved by IRE1α, we performed an in vitro cleavage assay. Recombinant IRE1α efficiently cleaved the CReP mRNA into multiple small fragments which were further degraded in the presence of high dose of IRE1α, suggesting that CReP mRNA was cleaved by IRE1α at multiple sites (Fig. 2B). Mutation in the predicted IRE1α-cleavage site diminished the cleavage of CReP mRNA (Fig. 2B), indicating that IRE1α indeed recognized this hairpin structure among many in CReP mRNA to induce the degradation.

FIG 2.

CReP mRNA is cleaved by IRE1α. (A) Predicted secondary structure of a putative IRE1α cleavage site in CReP mRNA. An arrow indicates the predicted cleavage site. Two G residues in boldface were changed to an A to generate the mutant construct. (B) CReP RNA generated by in vitro transcription was incubated with indicated amounts of recombinant IRE1α, and separated on a denaturing agarose gel. The data are representative of three independent experiments. M, molecular weight marker. (C and E) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pCMV-SPORT6-CReP or pCMV-SPORT6-CReP mutant, together with empty, WT, or K599A mutant IRE1α plasmids. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection for Western blot analysis. (D and F) Quantification of CReP abundance normalized to Hsp90. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

To further validate CReP mRNA as a RIDD substrate, a CReP expression plasmid was transfected into HEK293T cells, together with WT or K599A mutant IRE1α lacking both kinase and RNase activities (30). CReP expression was decreased by the cotransfected WT IRE1α but not by K599A mutant IRE1α (Fig. 2C and D). On the other hand, the expression of the mutant CReP in which the predicted IRE1α cleavage site was destroyed was unaffected by the cotransfected IRE1α (Fig. 2E and F). These data indicate that the hairpin region is critical for IRE1α-mediated degradation of CReP mRNA. Interestingly, increasing doses of CReP plasmid decreased the expression of cotransfected WT and K599A mutant IRE1α, likely reflecting an inhibitory role of CReP in global protein translation.

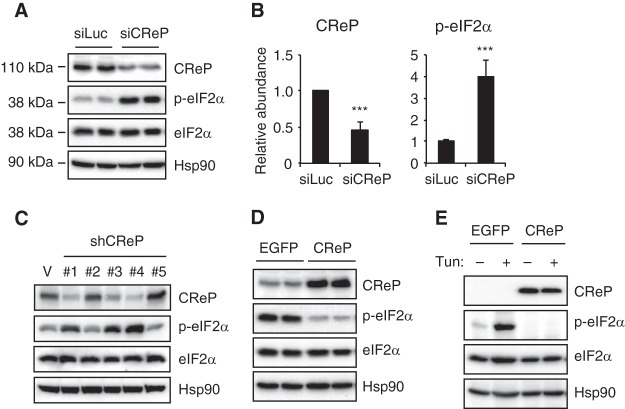

Suppression of CReP expression increased eIF2α phosphorylation in XBP1 knockout liver.

We next investigated the correlation between CReP abundance and eIF2α phosphorylation. CReP silencing by siRNA transfection markedly increased eIF2α phosphorylation in mouse Hepa1-6 hepatoma cells (Fig. 3A and B). Increased eIF2α phosphorylation was also observed by stable expression of CReP shRNA in human HeLa cells (Fig. 3C). Notably, different shRNAs exhibited various degrees of CReP knockdown efficiency, which correlated well with the degree of eIF2α phosphorylation. In contrast, CReP overexpression almost completely abolished the basal eIF2α phosphorylation in Hepa1-6 cells (Fig. 3D). Tunicamycin-induced eIF2α phosphorylation was also completely abolished by CReP overexpression (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that the abundance of CReP is a critical determinant of eIF2α phosphorylation, and the decreased expression of CReP increased eIF2α phosphorylation in XBP1-deficient livers.

FIG 3.

CReP abundance inversely correlates with eIF2α phosphorylation. (A) Hepa1-6 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting luciferase or CReP. Representative Western blot images of duplicate samples are shown. (B) Quantification CReP protein and eIF2α phosphorylation (n = 5 per group). (C) HeLa cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing different CReP shRNAs. CReP and phosphorylated eIF2α were measured by Western blotting. (D) Hepa1-6 cells were transfected with pCMV-SPORT6-EGFP or -CReP plasmids. eIF2α phosphorylation was measured by Western blotting. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmids, treated with tunicamycin for 2 h, and analyzed by Western blotting.

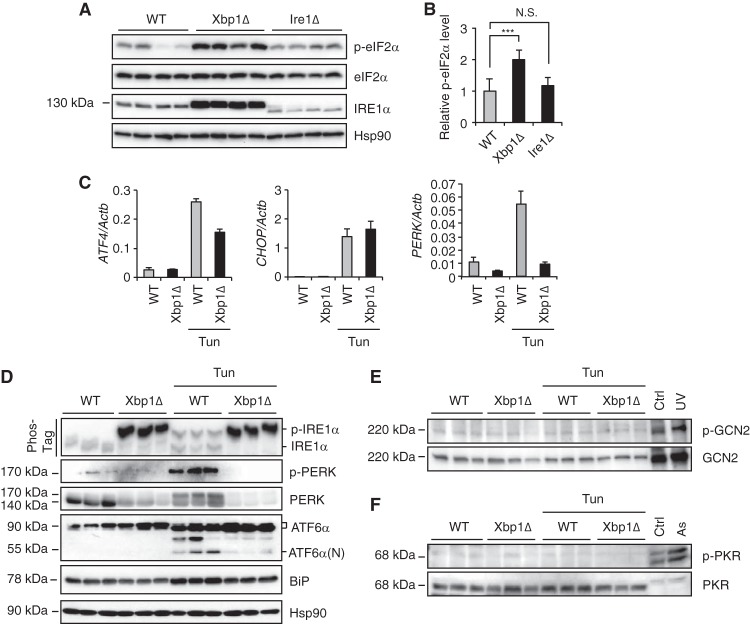

To determine whether the downregulation of CReP increased eIF2α phosphorylation in XBP1 knockout livers, we performed Western blotting on liver lysates from XBP1- and IRE1α knockout mice. Consistent with the decrease in CReP abundance, eIF2α phosphorylation was markedly increased in XBP1 knockout livers (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, eIF2α phosphorylation was not increased in IRE1α-deficient liver (Fig. 4A and B), suggesting that the hyperactivation of IRE1α rather than the loss of XBP1s is responsible for the increased eIF2α phosphorylation in XBP1-deficient livers. Notably, despite constitutive eIF2α phosphorylation, PERK-dependent ATF4 or CHOP were not induced in XBP1-deficient livers but strongly induced by tunicamycin in both WT and XBP1 knockout livers (Fig. 4C), suggesting that eIF2α phosphorylation was not sufficient for the activation of the ATF4-CHOP pathway. BiP/Grp78, which plays a central role in UPR sensing, was slightly downregulated in XBP1 knockout livers (Fig. 4C).

FIG 4.

Downregulation of CReP expression increased eIF2α phosphorylation in XBP1 knockout liver. (A) Liver lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis. Representative images are shown for four individual mice per group. Note that Ire1Δ mice produce mutant IRE1α missing 64 amino acid residues in the RNase domain. (B) CReP protein levels were quantified from immunoblots of 10 mice per group. ***, P < 0.001, N.S., not significant. (C) Xbp1Δ, and the littermate control (WT) mice were untreated or injected with tunicamycin 6 h prior to sacrifice. Hepatic ATF4, CHOP, and PERK mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR (n = 3 to 5 mice per group). (D) WT and Xbp1Δ mice were untreated or injected with tunicamycin (2 mg/kg) 6 h prior to sacrifice. Liver lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Phos-tag gel electrophoresis was performed for an IRE1α Western blot (top panel). Representative images are shown for three individual mice per group. (E and F) Western blotting of GCN2 and PKR proteins. HeLa cells treated with UV (300 J/m2) or sodium arsenite (As, 100 μM) for 4 h were used as positive controls.

The level of eIF2α phosphorylation is determined by the balance between kinase and phosphatase activities. To exclude the possibility that eIF2α kinases are activated in XBP1 knockout liver to increase eIF2α phosphorylation, we examined activation of PERK, GCN2, and PKR kinases by Western blotting using phospho-specific antibodies. In contrast to marked phosphorylation of IRE1α as shown by the slow migration of the phosphorylated IRE1α on a Phos-Tag SDS-PAGE gel, we unexpectedly found that the abundance of PERK protein was markedly reduced in XBP1 knockout livers, which correlated with PERK mRNA expression (Fig. 4C and D). The980 phosphorylated PERK species was also hardly detectable in XBP1 knockout livers even after tunicamycin treatment. The mechanism by which XBP1 deficiency caused the reduction of PERK abundance, as well as its impact on eIF2α phosphorylation, remains to be further investigated. Other eIF2α kinases, such as GCN2 or PKR, were also not activated in XBP1-deficient livers (Fig. 4E and F). These data suggest that the constitutive eIF2α phosphorylation in XBP1 knockout liver is due to suppression of eIF2α phosphatase activity secondary to the decrease of CReP abundance, rather than activation of eIF2α kinases.

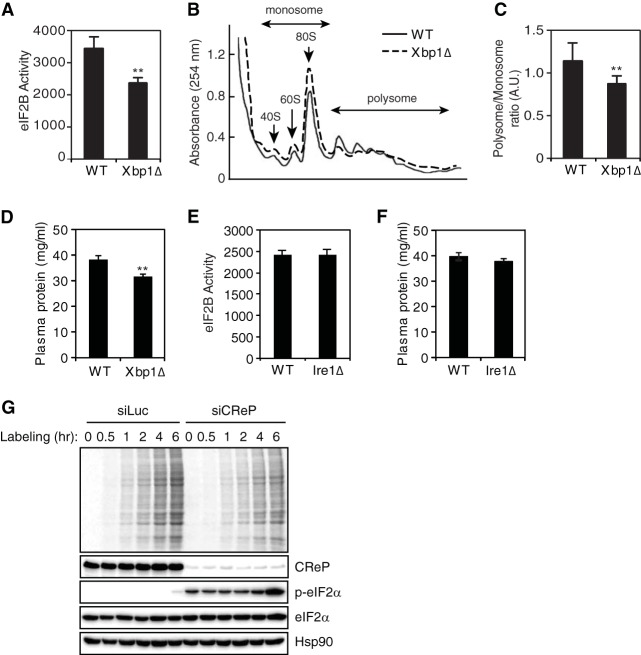

Hyperactivated IRE1α diminishes protein synthesis in XBP1-deficient liver.

Since eIF2α phosphorylation represses global protein synthesis, we sought to determine whether the protein synthesis rate was decreased by the loss of XBP1 in the liver. We first measured the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of eIF2B which is suppressed by the phosphorylated eIF2α (21, 22). Consistent with the marked increase in phosphorylated eIF2α, eIF2B activity was decreased in XBP1-deficient livers compared to the WT control (Fig. 5A). The proportion of RNA present in polysomes was also decreased in XBP1-deficient livers, indicating that the number of ribosomes actively translating mRNA was decreased in the absence of XBP1 due to increased eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 5B and C). Accordingly, protein concentrations in plasma were significantly reduced in the liver-specific XBP1 knockout mice compared to WT littermate controls (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, neither liver eIF2B activity nor plasma protein concentrations were significantly altered in IRE1α knockout mice (Fig. 5E and F). The effect of decreased CreP abundance on eIF2α phosphorylation and global protein synthesis was further examined in vitro. Consistent with the decreased protein synthesis associated with reduced CReP level in XBP1-deficient livers, CReP silencing increased eIF2α phosphorylation leading the reduction in protein synthesis in HeLa (Fig. 5G). These data indicate that the increased eIF2α phosphorylation caused by IRE1α hyperactivatation diminishes the rate of protein synthesis in the XBP1-deficient liver.

FIG 5.

Hyperactivated IRE1α diminishes protein synthesis in XBP1-deficient liver. (A and E) eIF2B activity in liver lysates (n = 3 or 4 mice per group). (B) Sucrose density gradient analysis of polysome profiles. Fractions representing monosomes and polyribosomes are indicated. The data shown are from representative experiments performed on 3 or 4 mice/group. (C) The polysome/monosome ratio was calculated. (D and F). Plasma protein concentration determined by BCA assay (n = 7 or 8 mice per group). (G) HeLa cells were transfected with control or CReP siRNA. After 72 h of transfection, the cells were incubated labeling medium containing [35S]methionine for the indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by autoradiography or Western blotting. **, P < 0.01.

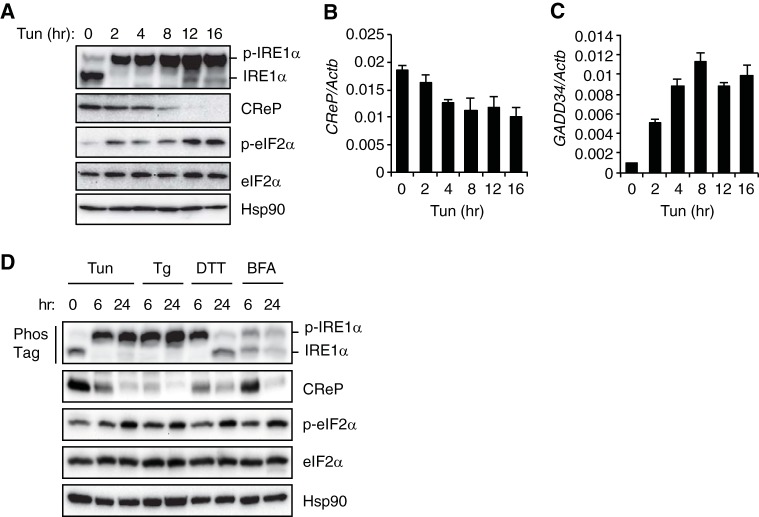

IRE1α-mediated degradation of CReP mRNA contributes to the increased eIF2α phosphorylation in ER stress response.

Since IRE1α cleaved CReP mRNA and induced its degradation, we next sought to determine whether ER stress decreased the abundance of CReP through IRE1α activation. Hepa1-6 mouse hepatoma cells abundantly express IRE1α that is strongly activated by tunicamycin treatment (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, tunicamycin treatment gradually decreased CReP protein and mRNA abundance and increased eIF2α phosphorylation and GADD34 mRNA expression (Fig. 6A to C). Notably, while CReP mRNA was decreased by ∼40%, reaching a nadir within 4 h of tunicamycint treatment, CReP protein was continuously decreased to near undetectable level by 16 h of tunicamycint treatment (Fig. 6A and B), suggesting that CReP expression would be regulated at multiple levels. Treatment of Hepa1-6 cells with other ER stress inducers, such as thapsigargin, DTT, or brefeldin A, also increased the abundance of phosphorylated IRE1α and phosphorylated eIF2α (Fig. 6D). In contrast, these reagents decreased CReP expression, exhibiting an inverse correlation with eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that the suppression of CReP expression could contribute to the ER stress-induced eIF2α phosphorylation.

FIG 6.

ER stress decreases the abundance of CReP mRNA and protein. (A) Time course of the effect of tunicamycin (2 μg/ml) on CReP abundance and eIF2α phosphorylation in Hepa1-6 cells. (B and C) The CReP (B) and GADD34 (C) mRNA levels in tunicamycin-treated Hepa1-6 cells determined by qRT-PCR. (D) Hepa1-6 cells were treated with tunicamycin (2 μg/ml; Tun), thapsigargin (1 μM; Tg), dithiothreitol (2 mM; DTT), or brefeldin A (5 μg/ml; BFA) and harvested 6 or 24 h later. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. IRE1α phosphorylation was measured by Phos-tag Western blotting.

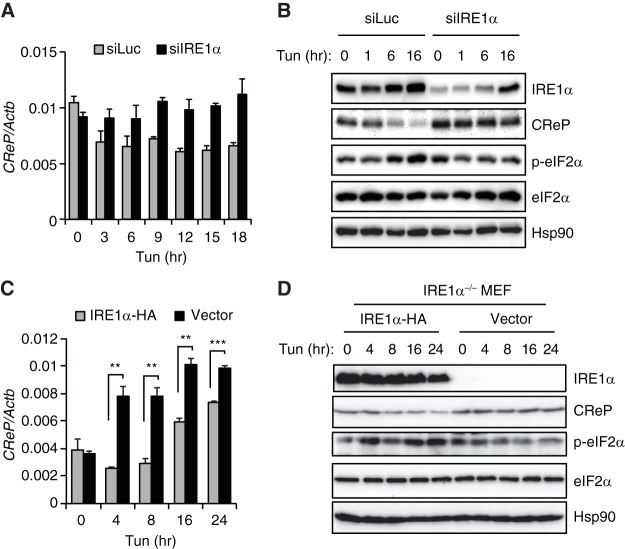

To investigate the role of IREα in the suppression of CReP expression and the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation in the ER stress response, we silenced IRE1α using siRNA. Tunicamycin decreased the abundance of CReP mRNA and protein, and increased eIF2α phosphorylation in control siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 7A and B). IRE1α siRNA inhibited the tunicamycin-mediated suppression of CReP expression and the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 7A and B), suggesting that ER stress-activated IRE1α decreased CReP abundance, leading to the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation. IRE1α knockout cells exhibited a modest induction of CReP mRNA upon tunicamycin treatment, suggesting that CReP transcription could be activated by ER stress in certain cells (Fig. 7C). However, CReP protein was not increased by tunicamycin in these cells (Fig. 7D), implicating multiple mechanisms to regulate CReP abundance (e.g., protein stability). Nonetheless, human IRE1α-reconstituted cells exhibited significantly lower CReP mRNA and protein expression and higher eIF2α phosphorylation compared to the control cells upon tunicamycin treatment, suggesting that IRE1α could suppress CReP expression by RIDD, increasing eIF2α phosphorylation during ER stress (Fig. 7C and D).

FIG 7.

IRE1α-mediated degradation of CReP mRNA contributes to the decrease of CReP abundance by ER stress. (A) Hepa1-6 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting luciferase or IRE1α and treated with tunicamycin. (B) qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses were performed with the indicated primers and antibodies. (C and D) IRE1α −/− MEF cells reconstituted with empty vector or hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged IRE1α were treated with tunicamycin. CReP mRNA and protein levels were determined. The IRE1α, total eIF2α, and phospho-eIF2α levels were also determined.

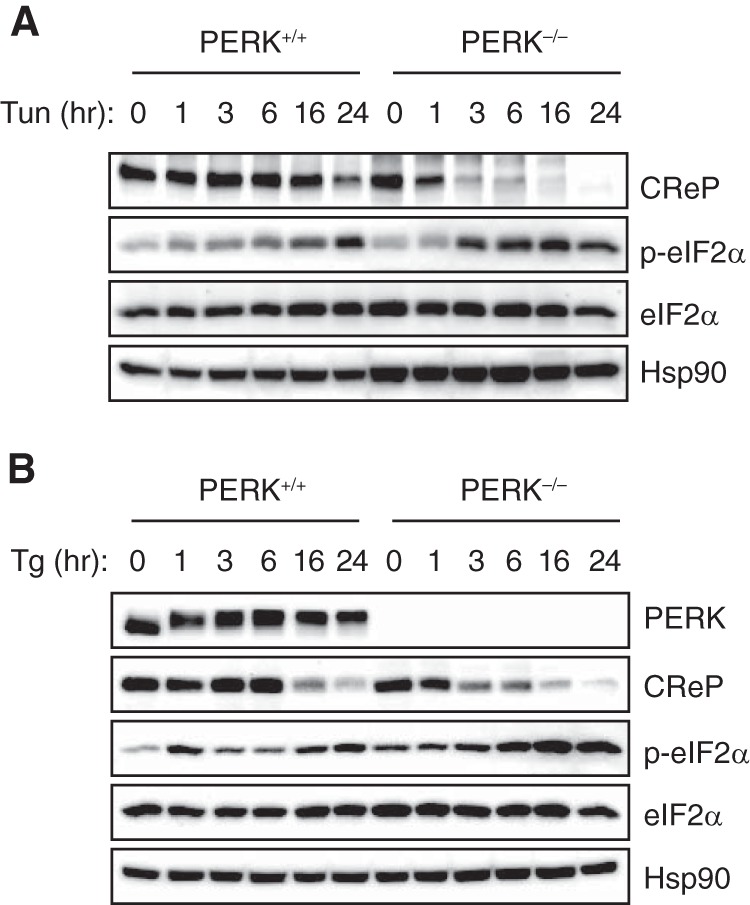

We next sought to determine whether CReP downregulation contributes to eIF2α phosphorylation during ER stress independent of PERK. Consistent with the direct role of PERK in eIF2α phosphorylation, PERK knockout MEF cells exhibited reduced eIF2α phosphorylation compared to WT cells within 1 h of tunicamycin or thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 8). However, prolonged treatment with tunicamycin or thapsigargin suppressed CReP expression and induced eIF2α phosphorylation in both PERK+/+ and PERK−/− cells (Fig. 8). In summary, our study reveals an unappreciated role of IRE1α in the regulation of eIF2α phosphorylation independent of PERK kinase.

FIG 8.

IRE1α-mediated degradation of CReP mRNA occurs independent of PERK. (A and B) PERK knockout and control MEFs were treated with tunicamycin (2 μg/ml) (A) or thapsigargin (1 μM) (B). The levels of eIF2α and phospho-eIF2α were determined by Western blotting.

DISCUSSION

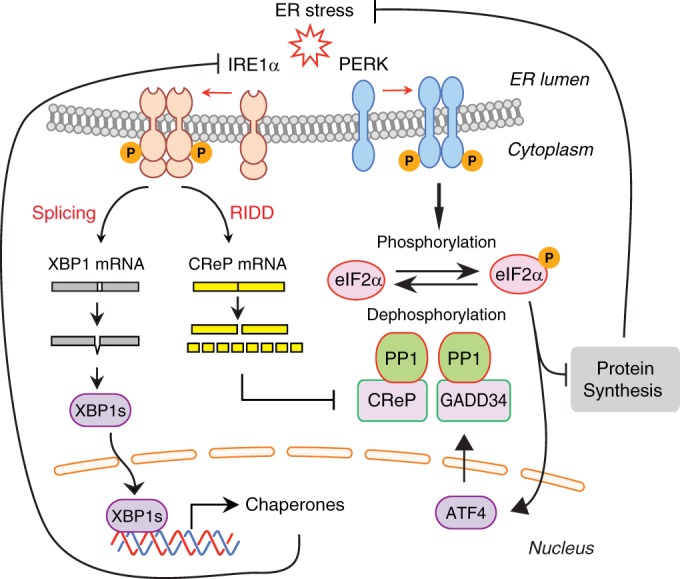

IRE1α-XBP1 and PERK-eIF2α UPR branches have been considered parallel pathways that are independently activated by ER stress (1, 2). Unexpectedly, we found that IRE1α controlled eIF2α phosphorylation by suppressing the expression of CReP regulatory subunit of the eIF2α phosphatase. CReP mRNA was cleaved by IRE1α and subsequently degraded most likely by cellular nucleases, a process known as RIDD. We showed that hyperactivated IRE1α in XBP1-deficient livers suppressed CReP expression, leading to the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation and the attenuation of protein synthesis. We also showed that IRE1α-dependent CReP degradation contributed to the increased eIF2α phosphorylation in the ER stress response. Taken together, the results of our study revealed a novel function of IRE1α in the regulation of eIF2α phosphorylation and translational control (Fig. 9).

FIG 9.

Model for the regulation eIF2α phosphorylation by IRE1α. Upon activation IRE1α cleaves XBP1 mRNA to induce an unconventional splicing, which generates XBP1s transcription factor. IRE1α also cleaves CReP mRNA which contains a XBP1-like stem-loop structure. IRE1α-cleaved CReP mRNA is degraded by cellular RNases. CReP acts as a cofactor for eIF2α phosphatase. Reduction in CReP protein abundance impedes eIF2α dephosphorylation, leading to the accumulation of phosphorylated eIF2α species. Upon ER stress, eIF2α phosphorylation is also increased by direct phosphorylation by PERK kinase. Increased eIF2α phosphorylation by CReP downregulation or PERK activation attenuates protein synthesis to reduce the stress damage. PERK also induces GADD34, constituting a negative-feedback loop for eIF2α phosphorylation.

Since eIF2α plays a central role in the host response to diverse stress signals, four kinases, PERK, GCN2, PKR, and HRI that are activated by distinct stress signals and phosphorylate eIF2α attracted much attention as key regulators of eIF2α phosphorylation (31). In contrast, dephosphorylation of eIF2α has received less attention as a control mechanism except the feedback inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation by ER stress-inducible GADD34 (23, 24). CReP has been considered a constitutive PP1 activator (24). In the present study, we demonstrated that CReP abundance was negatively regulated by IRE1α. Modulation of CReP abundance by RNA interference or gene overexpression had a major impact on eIF2α phosphorylation such that CReP abundance and eIF2α phosphorylation exhibited a strong inverse correlation. This suggested that CReP abundance was a critical determinant of eIF2α phosphorylation. eIF2α phosphorylation is known to be increased under various stressful conditions to suppress mRNA translation (31). Further studies will determine the relative contributions by eIF2α kinases and phosphatases to eIF2α phosphorylation status under different physiological and pathological conditions.

Although we demonstrated that IRE1α could regulate eIF2α phosphorylation via CReP mRNA degradation, it is not known whether this occurs in normal physiological or pathological conditions. One caveat is that RIDD requires hyperactivation of IRE1α which can be induced by chemical ER stress inducers or by the loss of XBP1 in certain cell types (32). Although IRE1α activation has been reported in numerous studies investigating the role of UPR in the development of secretory cells and the pathological conditions associated with protein misfolding in ER, the involvement of RIDD has not been carefully assessed. Further studies will define the relative contributions by RIDD and XBP1s downstream of IRE1α in the physiological UPR.

ATF4 is induced by ER stress at both transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation facilitates ATF4 translation through a mechanism involving the short open reading frames in the 5′ untranslated region (33). Ablation of PERK or S51A mutation of eIF2α precluding PERK-mediated phosphorylation abolished ATF4 protein induction by ER stress, suggesting that ATF4 is posttranscriptionally regulated by the PERK-eIF2α pathway (33, 34). Interestingly, however, despite the increased eIF2α phosphorylation, neither ATF4 nor its downstream CHOP was induced in XBP1-deficient livers, indicating that eIF2α phosphorylation was not sufficient for the activation of ATF4 pathway. These data are in accordance with previous reports showing that UV irradiation strongly induces IF2α phosphorylation but not ATF4 or CHOP proteins (35, 36). It is notable that ATF4 mRNA abundance is increased by ER stress or amino acid starvation but not by UV irradiation or CReP depletion. Taken together, these data suggest that the transcriptional activation is critical for the expression of ATF4 proteins and warrants further investigation focusing on the mechanism of transcriptional control of ATF4.

Translational control is a rapid and effective way for the cell to respond to many different stresses. For example, suppression of translation by phosphorylated eIF2α lessens the burden on ER, while a protective gene expression program is activated to curtail the stress damage (3). It has been shown that CReP silencing increased the viability of the cells under oxidative stress, peroxynitrite stress, and ER stress, underscoring the cytoprotective effects of the attenuation of protein synthesis in the stress response (24). On the other hand, in vivo function of CReP remains poorly understood. CReP knockout mice showed severe growth retardation and perinatal lethality, precluding the exploration of the pathophysiological roles of CReP (37). It would be interesting to test if the increased eIF2α phosphorylation owing to CReP depletion in a cell-type-specific manner is beneficial to the cell viability and secretory function of osteoblasts and pancreatic acinar cells and beta cells contrasting to the phenotypes of PERK or eIF2α mutant mice (38–41). Pharmacological augmentation of eIF2α phosphorylation has been also shown to protect cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis (42, 43). Interestingly, two small molecules that promote eIF2α phosphorylation, salubrinal and gaunabenz, were shown to inhibit dephosphorylation of eIF2α, implicating that eIF2α phosphatase complex is a feasible pharmacological target. Given the tight control of eIF2α phosphorylation by CReP, targeting CReP function by small molecule inhibitors would be a novel therapeutic strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Lydia Kutzler for performing the eIF2B assays, Sharon Rannels for polysome analysis, David Ron for IRE1α−/− and PERK−/− MEFs, Douglas Cavener for GCN2−/− MEFs, and Michael Park for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK089211 (A.-H.L.) and R01DK15658 (S.R.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Walter P, Ron D. 2011. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hetz C, Martinon F, Rodriguez D, Glimcher LH. 2011. The unfolded protein response: integrating stress signals through the stress sensor IRE1α. Physiological Rev 91:1219–1243. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ron D, Walter P. 2007. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. 2005. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem 74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner BM, Pincus D, Gotthardt K, Gallagher CM, Walter P. 2013. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensing in the unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5:a013169. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acosta-Alvear D, Zhou Y, Blais A, Tsikitis M, Lents NH, Arias C, Lennon CJ, Kluger Y, Dynlacht BD. 2007. XBP1 controls diverse cell type- and condition-specific transcriptional regulatory networks. Mol Cell 27:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee A-H, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. 2003. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol 23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaffer AL, Shapiro-Shelef M, Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Qian SB, Zhao H, Yu X, Yang L, Tan BK, Rosenwald A, Hurt EM, Petroulakis E, Sonenberg N, Yewdell JW, Calame K, Glimcher LH, Staudt LM. 2004. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity 21:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter P, Weissman JS. 2009. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oikawa D, Tokuda M, Hosoda A, Iwawaki T. 2010. Identification of a consensus element recognized and cleaved by IRE1α. Nucleic Acids Res 38:6265–6273. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han D, Lerner AG, Vande Walle L, Upton J-P, Xu W, Hagen A, Backes BJ, Oakes SA, Papa FR. 2009. IRE1α kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell 138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollien J, Weissman JS. 2006. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science 313:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.So J-S, Hur Kyu Y, Tarrio M, Ruda V, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Fitzgerald K, Koteliansky V, Lichtman Andrew H, Iwawaki T, Glimcher Laurie H, Lee A-H. 2012. Silencing of lipid metabolism genes through IRE1α-mediated mRNA decay lowers plasma lipids in mice. Cell Metab 16:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hur KY, So J-S, Ruda V, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Fitzgerald K, Koteliansky V, Iwawaki T, Glimcher LH, Lee A-H. 2012. IRE1α activation protects mice against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. J Exp Med 209:307–318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binet F, Mawambo G, Sitaras N, Tetreault N, Lapalme E, Favret S, Cerani A, Leboeuf D, Tremblay S, Rezende F, Juan AM, Stahl A, Joyal JS, Milot E, Kaufman RJ, Guimond M, Kennedy TE, Sapieha P. 2013. Neuronal ER stress impedes myeloid-cell-induced vascular regeneration through IRE1α degradation of netrin-1. Cell Metab 17:353–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osorio F, Tavernier SJ, Hoffmann E, Saeys Y, Martens L, Vetters J, Delrue I, De Rycke R, Parthoens E, Pouliot P, Iwawaki T, Janssens S, Lambrecht BN. 2014. The unfolded-protein-response sensor IRE-1α regulates the function of CD8α+ dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 15:248–257. doi: 10.1038/ni.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee AH, Heidtman K, Hotamisligil GS, Glimcher LH. 2011. Dual and opposing roles of the unfolded protein response regulated by IRE1α and XBP1 in proinsulin processing and insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:8885–8890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105564108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. 1999. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori K. 2000. Tripartite management of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 101:451–454. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ron D, Harding HP. 2012. Protein-folding homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum and nutritional regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4:a013177. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinnebusch AG. 2000. Mechanism and regulation of initiator methionyl-tRNA binding to ribosomes in translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Monogr Arch 2000:503–527. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pavitt GD, Ron D. 2012. New insights into translational regulation in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4:a012278. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novoa I, Zeng H, Harding HP, Ron D. 2001. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2α. J Cell Biol 153:1011–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jousse Cl., Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Lu P, Zhang Y, Harding HP, Ron D. 2003. Inhibition of a constitutive translation initiation factor 2α phosphatase, CReP, promotes survival of stressed cells. J Cell Biol 163:767–775. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Y, Hendershot LM. 2003. Delineation of a negative feedback regulatory loop that controls protein translation during endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem 278:34864–34873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee A-H, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, Glimcher LH. 2008. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science 320:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwawaki T, Akai R, Yamanaka S, Kohno K. 2009. Function of IRE1α in the placenta is essential for placental development and embryonic viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:16657–16662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903775106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hetz C, Bernasconi P, Fisher J, Lee AH, Bassik MC, Antonsson B, Brandt GS, Iwakoshi NN, Schinzel A, Glimcher LH, Korsmeyer SJ. 2006. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK modulate the unfolded protein response by a direct interaction with IRE1α. Science 312:572–576. doi: 10.1126/science.1123480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimball SR, Everson WV, Flaim KE, Jefferson LS. 1989. Initiation of protein synthesis in a cell-free system prepared from rat hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 256:C28–C34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tirasophon W, Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. 1998. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes Dev 12:1812–1824. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baird TD, Wek RC. 2012. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 phosphorylation and translational control in metabolism. Adv Nutr 3:307–321. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maurel M, Chevet E, Tavernier J, Gerlo S. 2014. Getting RIDD of RNA: IRE1 in cell fate regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 39:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D. 2000. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell 6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheuner D, Song B, McEwen E, Liu C, Laybutt R, Gillespie P, Saunders T, Bonner-Weir S, Kaufman RJ. 2001. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell 7:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dey S, Baird TD, Zhou D, Palam LR, Spandau DF, Wek RC. 2010. Both transcriptional regulation and translational control of ATF4 are central to the integrated stress response. J Biol Chem 285:33165–33174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang HY, Wek RC. 2005. GCN2 phosphorylation of eIF2α activates NF-κB in response to UV irradiation. Biochem J 385:371–380. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Scheuner D, Chen J-J, Kaufman RJ, Ron D. 2009. Ppp1r15 gene knockout reveals an essential role for translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) dephosphorylation in mammalian development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:1832–1837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809632106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Jungries R, Chung P, Plesken H, Sabatini DD, Ron D. 2001. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in Perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol Cell 7:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang P, McGrath B, Li S, Frank A, Zambito F, Reinert J, Gannon M, Ma K, McNaughton K, Cavener DR. 2002. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol Cell Biol 22:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3864-3874.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei J, Sheng X, Feng D, McGrath B, Cavener DR. 2008. PERK is essential for neonatal skeletal development to regulate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Physiol 217:693–707. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W, Feng D, Li Y, Iida K, McGrath B, Cavener DR. 2006. PERK EIF2AK3 control of pancreatic beta cell differentiation and proliferation is required for postnatal glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab 4:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boyce M, Bryant KF, Jousse Cl Long K, Harding HP, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Ma D, Coen DM, Ron D, Yuan J. 2005. A selective inhibitor of eIF2α dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science 307:935–939. doi: 10.1126/science.1101902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsaytler P, Harding HP, Ron D, Bertolotti A. 2011. Selective inhibition of a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 restores proteostasis. Science 332:91–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1201396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]