Abstract

Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM) usually occurs after viral infections or vaccination. Its occurrence after Plasmodium vivax infection is extremely uncommon. We report the case of an 8-year-old girl who had choreo-athetoid movements and ataxia after recovery from P.vivax infection. Diagnosis of ADEM was made on the basis of magnetic resonance imaging findings. The child responded to corticosteroids with complete neurological recovery.

Key words: Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, malaria; post-malaria neurological syndrome, Plasmodium vivax

Introduction

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a monophasic, immune medited, inflammatory and demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) with diffuse neurological signs and multifocal white matter lesions on neuroimaging.1,2 It usually occurs within 2 days to 4 weeks following a viral infection or vaccination.3,4 In some patients, no antecedent trigger can be identified. An autoimmune reaction of T-cells against myelin basic protein, triggered by viral infection or vaccination, has been suggested as a possible pathogenesis.5 Post-malarial ADEM has been previously reported as a complication of Plasmodium falciparum. To the best of our knowledge, only a single case of ADEM following treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria has been reported in pediatric literature.6

Case Report

An 8-year old female child presented with complaints of fever and vomiting for 2 days and an episode of generalized tonic clonic seizure on the day of admission. Her mother and sibling were also admitted to our hospital with diagnosis of severe malaria. Vitals revealed tachycardia and hypotension. On general physical examination, the child had mild pallor with no sign of icterus, cyanosis, edema or lymphadenopathy. Respiratory, cardiovascular and abdominal examinations were normal. Neurological examination showed that the child was drowsy with hypertonia, hyper-reflexia and positive Babinski response. There were no meningeal or cerebellar signs.

Investigations showed hemoglobin 9.8 g/dL, white blood cell count 9.8×103/µL and platelets 0.37×109/µL. Peripheral smear examination showed multiple trophozoites of P.vivax along with thrombocytopenia. Differential leucocyte count was 60% neutrophils, 30% lymphocytes, 3% eosinophils and 7% monocytes. Rapid malaria antigen tests (RMAT) was also positive for P.vivax. Serum biochemistry including blood sugar, renal and liver function tests were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was normal.

Child was managed in intensive care unit with supportive care for hypotension with crystalloids and ionotropes. In view of peripheral smear and RMAT suggestive of P.vivax, the child was started on intravenous artesunate (as per the guidelines of National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, India, for severe malaria).7

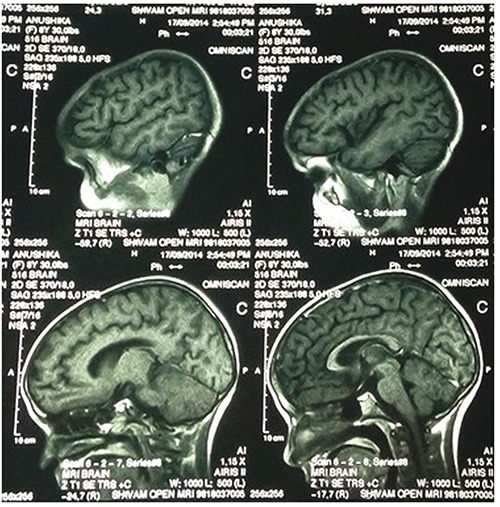

The child responded well and was shifted to pediatric ward after one week of admission. Patient did not have any neurological deficit and repeat peripheral smears showed parasitological clearance. On day 15 of illness, the child presented with abnormal movements in form of ataxia and choreo-athetoid movements of limbs. There were no meningeal signs or cranial nerve palsies. Deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated and Babinski sign was present. Repeat peripheral blood smear examination did not show any malarial parasite. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain with contrast showed high intensity signals in subcortical, cortical, left parietal, periventricular regions and pons (Figure 1). In view of temporal relationship and latency of symptoms and MRI findings, diagnosis of post malaria ADEM (secondary to P.vivax) was made. Patient was started on prednisolone at 2 mg/kg/day for 7 days and tapered over one week. Choreoathetoid movements decreased and ataxia improved. After 2 weeks of discharge, patient had no neurological sequelae.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showing high-intensity signals in subcortical, cortical, left parietal, periventricular regions and pons.

Discussion

Severe malaria is known to be classically caused by P.falciparum species, but in recent years, P.vivax is being increasingly recognized as a cause of severe malaria in children.8 ADEM has been reported in literature as a complication of falciparum malaria (Table 1).4,6,9-12 Only a single case of P.vivax malaria followed by ADEM has been reported in pediatric age group.6 This case reiterates the importance of neurological complications occurring even after recovery from P.vivax in concordance with the changing epidemiology of malaria.

Table 1.

List of cases of acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis reported after recovery from malaria.

| First author | Species | Age of patient | Time of neurological complication after recovery from malaria | MRI finding (T2-DWI) | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohsen4 | P. falciparum | 30y | 8 weeks | Hyperintensities in subcortical white matter of right frontal and temporal lobes and left cerebellar hemisphere | No steroids | Complete neurological recovery |

| Sharma9 | P. falciparum | 20y | 2 weeks | Hyperintensities of subcortical white matter, corpus callosum and midbrain | I/V methylprednisolone for 3 days | Complete neurological recovery |

| Rachita10 | P. falciparum | 4y | 1 week | Hyperintensities in cerebral hemisphere, subcortical white matter and midbrain | I/V methylprednisolone for 3days, then oral steroids | Complete neurological recovery |

| Agrawal11 | P. f alciparum | 12y | 16 days | Hyperintensities in perventricular white matter, centrum semiovale and genu of corpus callosum | I/V methylprednisolone for 5 days, then oral steroids | Complete neurological recovery |

| Koibuchi12 | P. vivax | 24y | 2 weeks | Hyperintensities in left cerebral cortex and subcortex | Complete neurological recovery | |

| Goyal6 | P. vivax | 18mo | 1 week | Diffuse white matter hyperintensities fof subcortical deep and periventricular white matter and both external capsules | I/V methylprednisolone for 3 days, then oral steroids for 2 weeks | Complete neurological recovery |

y, years; mo, months; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Post-malaria neurological syndrome (PMNS) was first described by Nguyen et al. as symptomatic malaria infection (initial blood smear positive for asexual forms of parasite), whose parasites have cleared from the peripheral blood and, in cerebral cases, had recovered consciousness fully, who developed neurological or psychiatric symptoms within two months of acute illness.13 Schnorf, et al. classified PMNS into 3 subtypes according to severity: i) mild and localized encephalopathy, characterized by isolated cerebellar ataxia or postural tremor; ii) diffuse, but relatively mild encephalopathic form, characterized by acute confusion or epileptic seizures; and iii) severe, corticosteroid-responsive encephalopathy, characterized by motor aphasia, generalized myoclonus, postural tremor, and cerebellar ataxia, resembling ADEM.14 PMNS and ADEM have striking similarities e.g. period of latency, multifocal neurological deficits, response to steroids and good prognosis.

Increase in levels of cytokines in cere-brospinal fluid, tumor necrosis factor- and interleukins 2 and 6 have been noted in severe malaria and PMNS.15 The latency to neurological involvement after eradication of parasite and response to corticosteroids in our patient support an immunological mechanism.

Conclusions

Recurrent or new appearance of neurological complications in a known patient of severe malaria should arouse suspicion of ADEM. Cranial MRI should be ordered for confirmation of the diagnosis. Definitive treatment should be instituted as the disease has a good outcome with negligible sequelae.

References

- 1.Murthy SNK, Faden HS, Cohen ME, Bakshi R. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. Pediatrics 2002;110:e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alper G. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. J Child Neurol 2012;27:1408-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Wal G, Verhagen WIM, Dofferhoff ASM. Neurological complications following Plasmodium falciparum infection. Neth J Med 2005;63:180-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohsen AH, McKendrick MW, Schmid ML, et al. Postmalaria neurological syndrome: a case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg RK. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Postgrad Med J 2003;79:11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal JP, Shah VB, Parmar S. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria. J Vector Borne Dis 2012;49:119-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Vector Borne Diseases Control programme. Diagnosis and treatment of malaria in India. 2013. Availabile from: http://nvbdcp.gov.in/Doc/Diagnosis-Treatment-Malaria-2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh H, Parakh A, Basu S, Rath B. Plasmodium vivax malaria: Is it actually benign? J Infect Public Health 2011;4:91-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma N, Varma S, Bhalla A. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after treatment of severe falciparum malaria. Indian J Med Sci 2008;62:69-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rachita S, Satyasundar M, Mrutunjaya D, Birakishore R. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)—a rare complication of falciparum malaria. Indian J Pediatr 2013;80:499-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal A, Goyal S. Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis in a child following malaria. Indian Pediatr 2012;49:922-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koibuchi T, Nakamura T, Miura T, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following Plasmodium vivax malaria. J Infect Chemother Off J Jpn Soc Chemother 2003;9:254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen TH, Day NP, Ly VC, et al. Post-malaria neurological syndrome. Lancet 1996;348:917-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnorf H, Diserens K, Schnyder H, et al. Corticosteroid-responsive postmalaria encephalopathy characterized by motor aphasia, myoclonus, and postural tremor. Arch Neurol 1998;55:417-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Silva HJ, Hoang P, Dalton H, et al. Immune activation during cerebellar dysfunction following Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1992;86:129-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]