Abstract

Terpenes and alkaloids are ever-growing classes of natural products that provide new molecular structures which inspire chemists and possess a broad range of biological activity. Terpenoid-alkaloids originate from the same prenyl units that construct terpene skeletons. However, during biosynthesis, a nitrogen atom (or atoms) is introduced in the form of β-aminoethanol, ethylamine, or methylamine. Nitrogen incorporation can occur either before, during, or after the cyclase phase. The outcome of this unique biosynthesis is the formation of natural products containing unprecedented structures. These complex structural motifs expose current limitations in organic chemistry, thus providing opportunities for invention. This review focuses on total syntheses of terpenoid-alkaloids and unique issues presented by this class of natural products. More specifically, it examines how these syntheses relate to the way terpenoid-alkaloids are made in Nature. Developments in chemistry that have facilitated these syntheses are emphasized, as well as chemical technology needed to conquer those that evade synthesis.

Keywords: Alkaloids, Biomimetic synthesis, C–H activation, Natural products, Total synthesis

1. Introduction

Terpenoid-alkaloids are most simplistically described as aminated terpenes or even “azaterpenes”. For this reason, they have been dubbed pseudo- or crypto-alkaloids.1 Pseudo, meaning false, accurately describes the biosynthetic origins of these alkaloids, which are constructed from prenyl units rather than amino acids. Crypto, meaning hidden, refers to the close resemblance these molecules bear to the terpenoids they originate from. In contrast with true alkaloids, which are derived from amino acid precursors, the nitrogen sources for terpenoid-alkaloids are methylamine, ethylamine, and β-aminoethanol. Biosynthesis of these molecules begins with the same prenyl units that are transformed into terpenoids. As in terpene synthesis, prenyl units are first linked together to form relatively simple, phosphorylated hydrocarbon chains of varying lengths. These chains then undergo enzyme-mediated cyclizations and Wagner-Meerwein rearrangements during a cyclase phase. The formed carbocyclic skeletons are functionalized in a subsequent oxidase phase and, in some cases, undergo further rearrangement. The “twist” that occurs during biosynthesis, either in the cyclase phase or the oxidase phase, is the introduction of nitrogen in one of the forms listed above. Upon introduction of nitrogen atom(s), the molecule can no longer be considered a terpene and becomes classified as a terpenoid-alkaloid.

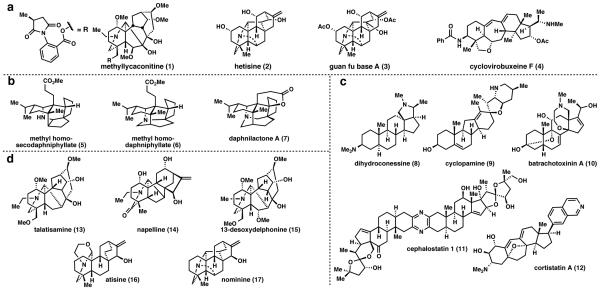

Of the 20,000+ alkaloids and 55,000+ terpenes isolated to date,2 only a few thousand molecules originating from a mere handful of natural product families qualify as terpenoid-alkaloids. These families include the smaller sesquiterpenoid-alkaloids such as dendrobine and pumiliotoxins, diterpenoid-alkaloids originating from the atisane and kaurane terpenoid families, and triterpenoidalkaloids which either manifest themselves as steroidalkaloids or Daphniphyllum alkaloids. Though limited in number, terpenoid-alkaloids possess a broad range of biological activity. Terpenoid-alkaloids have been utilized for many years as traditional medicines in China, Japan, Russia, Mongolia, and India.1 Conversely, they have been used since ancient times as poisons used for hunting and, later, in homicides.3 Methyllycaconitine (1) (Fig. 1a), the diterpenoid-alkaloid primarily responsible for the toxicity of Larkspurs, causes the majority of cattle deaths in western North America.4 More practically speaking, some diterpenoid-alkaloids, including hetisine (2) are competent insect repellants.5 Plants known to contain diterpenoid-alkaloids can ameliorate morphine withdrawal syndrome, aiding in recovery from addiction.6 Guan fu base A (3) has been clinically developed in China for therapeutic treatment of arrhythmia.7 Diterpenoid-alkaloids also possess antiinflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-epileptoform, and antiparasite activity.3 Buxaceae steroid-alkaloids have been used in Pakistan to treat malaria, leishmaniasis, and rheumatism.8 Several of them, including cyclovirobuxeine F (4), are antibacterials.9 Cortistatin A (12) has been highlighted for its anti-angiogenic properties that can treat cancer and blindness,10 as well as cephalostatin 1 (11) for its potential to be a highly selective anticancer therapeutic.11 While these molecules possess almost no structural homology with heterocycle-laden small-molecule therapeutics, the pharmacological properties of select terpenoid-alkaloids render them worthy candidates for further development.12

Figure 1.

(a) Biologically active terpenoid-alkaloids. Representation terpanoid-alkaloids prepared via total synthesis. (b) Representation examples of triterpanoid-alkaloids from the Daphniphyllum genus of plants. (c) Selected structurally compelx, biologically active steroid-alkaloids. (d) C19- and Ca20-di1erpanoid-alkaloids from the atisane and kaurane diterpane families represent the largest group of terpanoid alkaloids.

Beyond their biological activities and therapeutic potential, terpenoid-alkaloids possess intriguing structures that have challenged organic chemists since the first terpenoid-alkaloids were elucidated unambiguously in the 1950s. When and how the nitrogen atom(s) in these molecules is(are) incorporated in nature can steer the synthetic chemist towards a biomimetic approach. Conversely, at times the biosynthetic nitrogen incorporation may seem too daunting a process to recreate in the laboratory and a completely abiotic, and at times superior, approach must be devised. Also, when the nitrogen atom is incorporated in the molecules’ post-cyclase phase, it may be advantageous to work from cyclized precursors, if they are easily synthesized or commercially available. This is especially true for steroid-alkaloids, lending them well to a semi-synthetic or two-phase synthetic approach.13 Often, successful strategies require the implementation of modem chemistry on very complex systems. These syntheses highlight powerful C-H activation methods and logic, creative solutions to remote functionalization, and beautiful cascade reactions, as well as staggering re-creations ofbiomimetic transformations.

The total syntheses discussed in this review encompass nearly all of the previously stated categories of terpenoid-alkaloids with the exception of sesquiterpenoid-alkaloids. This review will first address Daphniphyllum alkaloid syntheses (Fig. 1b), then examples of steroid-alkaloid syntheses (Fig. 1e), and, finally, diterpenoid-alkaloid syntheses (Fig. 1d). Due to space limitations, only key chemical transformations will be discussed. In each case, the merits and disadvantages of biomimetic approaches will be examined as well as how advances in chemical science have improved, facilitated, or even made possible the syntheses of these molecules.

Phil S. Baran was born in New Jersey in 1977 and received his undergraduate education from New York University with Professor David I. Schuster in 1997. After earning his PhD with Professor K. C. Nicolaou at TSRI in 2001. he pursued postdoctoral studies with Professor E. J. Corey at Harvard until 2003. at which point he began his independent career at TSRI. rising to the rank of Professor in 2008. His laboratory is dedicated to the study of fundamental organic chemistry through the auspices of natural product total synthesis.

Emily Cherney received her BS in chemistry with a minor in music performance from TCNJ in 2007. where she conducted research in heterocyclic chemistry with Professor David A. Hunt. After graduating from TCNJ. she spent two years as a medicinal chemist first at PTC Therapeutics and then Bristol-Myers Squibb. She is currently a graduate student pursuing the total synthesis of natural products with Professor Phil S. Baran at TSRI. where she is supported by an NSF predoctoral fellowship.

2. Triterpenoid Alkaloids

Daphniphyllum alkaloids are the only known alkaloids derived from triterpenes aside from steroid-alkaloids. The first C30-type Daphniphyllum alkaloid was reported in 1909 by Yagi and was given the name daphnimacrine. 14 However, it was not until 1966 that Hirata and Yamamurareported the first structural elucidation of a C30-type Daphniphyllum alkaloid which was appropriately named daphniphylline. 15 Since this initial report in 1966, over 200 Daphniphyllum alkaloids possessin several unique skeletons had been reported as of 2009. 16 It was not until twenty years later, in 1986, that Heathcock et al. completed the first total synthesis of a Dafhniphyllum alkaloid: methyl homodaphniphyllate (6).17

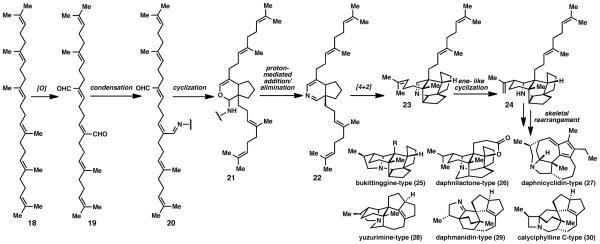

The proposed biosynthesis of these molecules begins with squalene (18) (Fig. 2). Rather than epoxidation and cyclization to a steroid framework, squalene is oxidized chemoselectively to dialdehyde 19. Condensation of this dialdehyde with a primary amine followed by cyclization and addition/elimination leads to the 6,5-fused ring system (22) containing a dihydropyridine ring. Diels–Alder cycloaddition followed by an ene-type cyclization completes the "aza"-cyclase phase that produces the carbon skeleton (24) of the Daphniphyllum alkaloids. This basic skeleton can rearrange to no less than thirteen other skeletons including the secodaphniphylline (5), bukittinggine (25), daphnilactone (26), daphnicyclidin (27), yuzurimine ps), daphmanidin (29), and calyciphylline (30) alkaloids.1 To date, only daphniphylline (6), secodaphniphylline (5), daphnilactone (7), and bukittinggine (25) type alkaloids have been prepared via total synthesis. 17,18 Additionally, inter-conversion between skeletons has been achieved by Heathcock et al.19

Figure 2.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway for the production of Daphniphyllum alkaloids.

The biological activity of these molecules has not been well studied, however, several molecules show cytotoxicity against tumor cell lines as well as antioxidant activity and vasorelaxant effects. (For more information, see ref. 15 and references therein.)

2.1. (+)-Methyl homodaphniphyllate (6) (Heathcock, 1986)

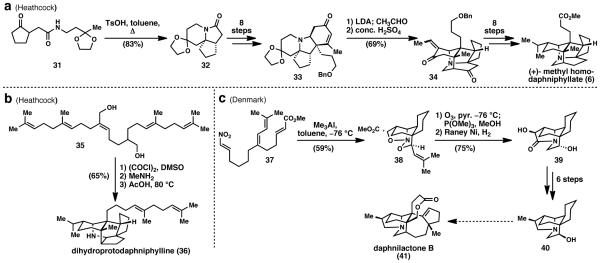

Methyl homodaphniphyllate (6) was Heathcock’s first synthesis of a Daphniphyllum alkaloid (Scheme 1a).17 This synthesis began with amide 31 which is formed via amidation between keto-acid and primary amine precursors. Heating amide 31 in anhydrous toluene in the presence of p-toluenesulfonic acid gave tricyclic lactam 32 in 83% yield. In 8 steps, lactam 32 was converted to enone 33. Formylation with lithium diisopropylamide and acetaldehyde provided a diastereomeric mixture of aldol products. These served as substrates for the key cascade reaction, which proceeded when the aldol products were treated with concentrated sulfuric acid. Heathcock writes, “A complex series of transformations ensues including dehydration, deketalization, and intramolecular Michael addition,”17 which provided desired product 34 in 69% overall yield from enone 33. While impressive, it is important to note that only a single carbon–carbon bond needed to form in order to convert 33 (a relatively complex substrate in its own right) to 34. Intermediate 34 was elaborated to the natural product via further redox and functional group manipulations in 8 steps. Thus, the synthesis was completed in a total of 20 steps.

Scheme 1.

2.2. Dihydro-proto-daphniphylline (36) (Heathcock, 1992)

Between 1986 and 1992, Heathcock and colleagues published the biomimetic total syntheses of several other Daphniphyllum alkaloids including (±)-methyl homosecodaphniphyllate (5), (±)-daphnilactone A (7), and (−)-secodaphniphylline.18 In his account of the synthesis of dihydroprotodaphniphylline (36), Heathcock not only detailed a biosynthetic hypothesis (which is generally accepted and shown in Fig. 2), but also demonstrated its feasibility.18g Diol 35 (Scheme 1b) underwent Swern oxidation to intercept the dihydro-version of the proposed biosynthetic intermediate 19 in Fig. 2. The resulting dialdehyde was then condensed with methylamine and heated with acetic acid, which directly provided the dihydro protodaphniphylline (36) in an impressive 65% yield. This cascade formed five rings, four carbon–carbon bonds, and two carbon–nitrogen bonds. It served as a successful recreation of the “aza”-cyclase phase used in nature and provided what is believed to be the common biosynthetic precursor to all 200+ related alkaloids.16 It is a beautiful example of how knowledge of a molecule’s biosynthesis can be used to make extremely complex skeletons efficiently.

2.3. Approach towards daphnilactone B (41) (Denmark, 2006)

With a biomimetic approach, the chemist can only meet, but never beat the efficiency of nature. In order to devise a superior approach, the Denmark laboratory presented an abiotic approach highlighting their nitro-1,3-dipole cycloaddition methodology.20 Using this methodology, branched tetraene 37 was converted to tetracycle 38 in a single step. This strategy could prove viable if the resulting cyclized product (40) would allow further elaboration onto the natural product.

It may seem that the lessons this class of molecules can teach the synthetic chemist have been exhausted, however, many members of this natural product family have not yet been synthesized. Indeed, a sea of opportunity still exists in this area for invention and discovery.

3. Steroid-Alkaloids

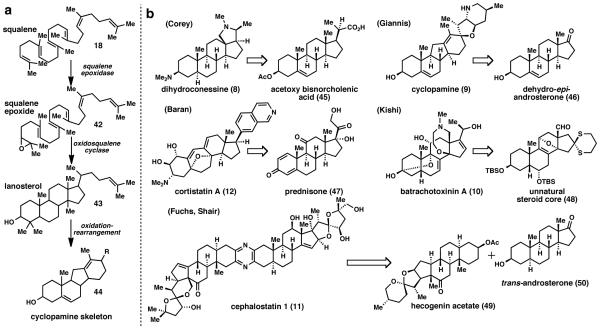

From a biosynthetic perspective, steroid-alkaloids present a completely different challenge when compared to triterpenoid-alkaloids. The unique “aza”-cyclase phase of triterpenoid-alkaloids was previously unknown and perhaps not readily apparent when the first structures were reported. In contrast, the cyclase phase for steroid-alkaloids is identical to the cyclase phase for steroids, which is well understood (Fig. 3a). Squalene (18) is epoxidized to 42 and then undergoes cation-π cyclization to give lanosterol (43). Beyond this, further oxidations, nitrogen introduction, and skeletal rearrangements can occur, as in the case of cyclopamine skeleton (44). Cation-π cyclizations have been well studied and used extensively in synthesis since the birth of the Stork–Eschenmoser hypothesis in 1955.21 Perhaps the most classic example of this is Johnson’s synthesis of progesterone in 1971,22 but it is still featured in present day syntheses such as Corey’s synthesis of lupeol in 2009.23

Figure 3.

a) Biosynthesis of the cyclopamine (9) skeleton b) Simplified steroidal architectures used in the construction of steroid-alkaloids, a large number of which are available commercially or in far greater abundance from nature (with the exception of the steroid-based skeletal precursor to batrachotoxinin A (10) which required non-biomimetic synthesis).

While the mastery of cation-π cyclizations has been crucial for synthesizing more complex steroids, it is also true that many steroids are commercially available. Given that many of these materials are abundant and inexpensive, it is logical that chemists in industry and academia would use these materials as starting points in their syntheses. Indeed, as recently as 2006, twenty of the top 200 brand name drugs on the U.S. market were semi-synthetic steroids (none were produced by total synthesis).

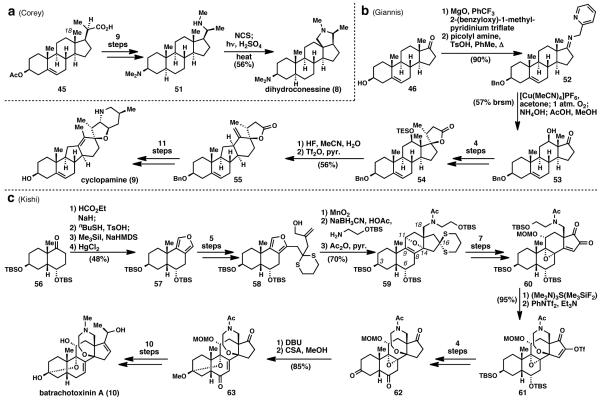

The semi-synthetic approach allows the chemist to address some of the most exciting problems in the synthesis of steroid-alkaloids, which, from a biosynthetic perspective, are introduced during the oxidase phase. For example, Corey’s synthesis of dihydroconessine (8)24 (Fig. 3b) begins with acetoxy bisnorcholenic acid (45). More recently, syntheses of cyclopamine (9),25 cortistatin A (12),26 and cephalostatin 1 (11)27 have all started with readily available steroid scaffolds including dehydro-epi-androsterone (46), prednisone (47), and hecogenin acetate (49), each of which are complex natural products in their own right. Worthy of note in the cases of cortistatin A and cyclopamine, skeletal rearrangements that occurred in Nature were recreated to synthesize the necessary carbon frameworks in the natural products. Batrachotoxinin A (10) presented a difficult, unusual oxidation pattern that could not be elaborated from a natural steroid precursor, leading the Kishi group to synthesize a customized steroid core (48) with the necessary functionality pre-installed.28

As the syntheses below are discussed, we believe that the most interesting transformations are those which oxidize the carbon skeleton. In biosynthesis, these transformations occur during the oxidase phase, a feat complicated by the nitrogen atom(s) in the case of steroid-alkaloids.

3.1. Dihydroconessine (8) (Corey, 1958)

Conessine’s structure was correctly proposed for the first time in 1952 by Haworth.29 During this time period, holarrhimine and aldosterone were also reported. These molecules all presented a similar, unique challenge: functionalization of the unactivated C18 methyl group (Scheme 2a). At the time, no expedient or direct solution to this problem existed. Serving as one of the first examples of C–H activation of an unactivated methyl group in total synthesis, Corey’s synthesis of dihydroconessine (8),24 in conjunction with work by Jeger, Arigoni, and co-workers,30 presented an expedient solution. The synthesis commenced from 3β-acetoxybisnorcholenic acid and, in 9 steps, was elaborated to amine 51.

Scheme 2.

This key substrate was then subjected to Hoffman–Löffler–Freytag (HLF) reaction conditions,31 forming the N-chloro derivative, which then underwent homolytic cleavage and 1,5-hydrogen abstraction. The resulting alkyl radical abstracted a chlorine atom intermolecularly, which was ultimately displaced by the secondary amine to form the C18-C20 amine bridge in conessine. Perhaps the only concession made was the reduction of the olefin in steroid 45 due to its incompatibility with the key HLF reaction, representing its current limitation in chemoselectivity. Regardless, knowledge of a suitable precursor, which presumably closely resembles the true biosynthetic precursor to this natural product, allowed the more challenging problems presented by the oxidase phase of this molecule to be quickly addressed and ultimately mastered. This work served as a prelude to an explosion of research pertaining to the remote functionalization of steroids, from the work of Barton32a-d and Breslow32e-g in the 1960s and 1970s to dozens of research groups presently. The logic of this timeless approach has been featured in recent syntheses and studies, including Shibanuma’s strategy toward kobusine34 and Giannis’ cyclopamine (9) synthesis.25

3.2. Cyclopamine (9) (Giannis, 2009)

First reported in 1957, cyclopamine (9) was identified as the component in Veratrum californicum responsible for the birth of lambs with cyclopia.35 While synthetic studies by Johnson et al.36 and Masamune et al.37 in the 1960s provided approaches towards cyclopamine (9), it was not until 2009 that Giannis and co-workers provided its expedient, biomimetic total synthesis (Scheme 2b).25 Starting with dehydro-epi-androsterone (46), benzyl protection and condensation gave the 2-picolylimine directing group (Schönecker directing group)33 on 52. Treatment with tetrakis(acetonitrilo)copper(I) hexafluorophosphate and molecular oxygen provided the 12β-hydroxyl group functionality that the commercially available core lacked. Alcohol 53 was then elaborated to pentacyclic lactone 54 in four steps. Treatment of 54 with hydrogen fluoride in acetonitrile and water unveiled the free 12β-hydroxyl group, which was subjected to trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride in pyridine. Heating to 50 °C induced the desired biomimetic Wagner–Meerwein-type rearrangement to the C-nor-D-homo skeleton 55 possessed by the natural product. In eleven subsequent steps, intermediate 55 was successfully elaborated to cyclopamine (9) in a total of 20 steps and 1% overall yield.

The featured transformations in the synthesis are the copper-mediated C–H activation/hydroxylation and cationic ring contraction/expansion. These transformations are extremely empowering because they address difficulties in functionality and the C-nor-D-homo skeleton installed during the oxidase phase of biosynthesis. Overcoming these challenges enabled the use of a commercially available steroid. This efficient total synthesis could allow access to unnatural analogues of cyclopamine (9) with potential therapeutic value in the treatment of cancer due to cyclopamine’s inhibitory affect on the hedgehog signaling pathway. The clever rearrangement utilized in this synthesis will facilitate the synthesis of other C-nor-D-homo steroids from commercially available precursors.

3.3. Batrachotoxin (10) (Kishi, 1998)

Batrachotoxin and batrachotoxinin A (10) (Scheme 2c) are isolated from the skins of poison arrow frogs and New Guinea birds in minute quantities.38 Both are potent neurotoxins by acting as irreversible Na+-channel activators.39 The highly oxidized, steroid-based structures of these molecules were determined via X-ray analysis and reported in 1968.40 Kishi reported the first and only total synthesis of batrachotoxinin A (10) in 1998, which constitutes a formal synthesis of batrachotoxin as well.28 Distinctive structural features of these molecules include a hemiketal at C3 and a fused oxazapane ring. These features, partnered with other unique sites of oxidation in the molecule, rendered a semi-synthetic two-phase approach from a commercially available steroid unfeasible. For this reason, a total synthesis of the A-D ring system containing the necessary functionality for elaboration to the natural product was first developed.

To make the A-D ring core, decalin 56 was converted to furan 57 employing the method of Garst and Spencer.41 In five steps, furan 57 was converted into allylic alcohol 58. Oxidation of 58 with manganese oxide gave the corresponding enal, which directly underwent intramolecular [4+2] cycloaddition. Reductive amination followed by acetylation of the cycloadduct gave amide 59. Intermediate 59 contains the steroidal core of the molecule with necessary sites of oxidation (at Carbons 3, 6, 8, 9, 11, 14, 16, and 18) as well as a nitrogen atom. Selective deprotection of the primary alcohol, followed by oxo-Michael addition and trapping with N-phenyltriflimide thereby formed the oxazapane ring in 61. Intermediate 61 was then carried forward to epoxide 62 in 4 steps. Treatment with 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene opened the epoxide, and subjection to camphorsulfonic acid in methanol provided ketal 63, which could be elaborated to batrachotoxinin A (10) in 10 additional steps. While Kishi’s synthesis of batrachotoxinin A is inarguably a landmark in total synthesis, it is possible that future advancements in oxidation chemistry could allow for an expedient, semi-synthetic approach toward this molecule starting from a commercial steroid.

3.4. Cephalostatin 1 (11) (Fuchs, 1998; Shair, 2010)

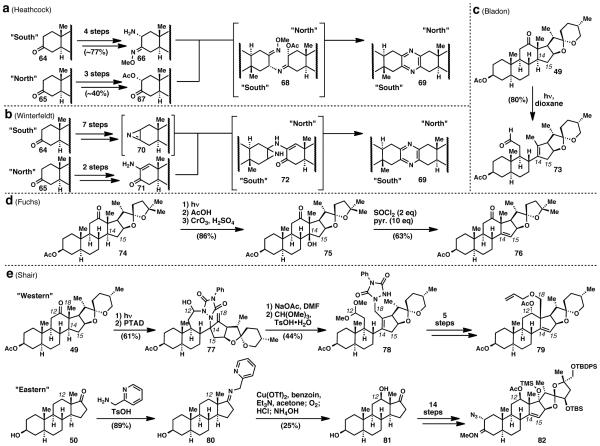

Cephalostatin 1 (11), first reported in 1988, represents the most potent cytotoxic member of the cephalostatin family and the closely related ritterazine natural product family.11 Cephalostatin 1 (11) has the potential to be a highly selective anticancer therapeutic, but is only available from Nature in extremely small quantities. These pseudo-dimeric steroidal pyrazines represent a unique challenge for synthesis on several levels. In pursuit of a highly convergent approach, the Heathcock and Winterfeldt groups first developed reactions for the synthesis of unsymmetric pyrazines that would allow for the controlled dimerization of the eastern and western (or northern and southern) regions of the molecule.42 Heathcock (Scheme 3a) and co-workers found that a unique southern portion (64) could be elaborated to an amino oxime (66) and the northern portion (65) could be elaborated to a keto acetate (67). When heated together in toluene, unsymmetric pyrazines (69) were formed in good yield via intermediate 68. Winterfeldt (Scheme 3b) and colleagues discovered that unsymmetric pyrazines (69) could be synthesized from reaction between azirine 70 and aminoenone 71 via intermediate 72.

Scheme 3.

With the unsymmetric dimerization barrier hurdled, the next challenge was to install the proper functionality on both of the unique regions of the molecule. Once again, these challenges had been overcome by Nature during the oxidase phase. If one were to start from commercially available steroids, the first challenge would be to effect a D-ring dehydrogenation to install an olefin between C14 and C15 (Scheme 3c). The next obstacle would be the C–H activations of the unactivated C12 methylene group and the C18 methyl group, both of which had been functionalized in previous syntheses of dihydroconessine (8) and cyclopamine (9), respectively.

The solution to the dehydrogenation problem of the D-ring was found in the work by Bladon and co-workers (Scheme 3c).43 Bladon found that irradiation of hecogenin acetate 49, a readily available, known biosynthetic precursor to cephalostatin 1, gave photolysis product 73. Fuchs capitalized on this observation (Scheme 3d) by treating the photolysis product of 74 with 75% acetic acid to effect an intramolecular Prins cyclization, which installed the tertiary alcohol at C14.27b Jones oxidation of the resulting diol gave keto alcohol 75. When treated with thionyl chloride and pyridine, the tertiary alcohol underwent elimination to give the desired Δ14 moiety in 76. Similar strategies were employed by Fuchs to complete several cephalostatins and ritterazines, including the first total synthesis of cephalostatin 1 (11) in 1998.27b

Over a decade later, the second and only other synthesis of cephalostatin 1 (11) was reported by Shair and co-workers. 27f To craft the western portion of the molecule (Scheme 3e), the Shair group modified the Bladon fragmentation in an elegant way. Rather than cyclizing enal 73 directly, the C18 methyl group was oxidized at this point since it was allylic and therefore activated—an opportunity that would not present itself again in the synthesis. After extensive experimentation, the Shair team found that treatment with PTAD not only performed the desired ene reaction, but also formed a seven-membered aminal 77. Opening of the acetal with sodium acetate quickly led to a [2,3]–sigmatropic rearrangement, and the resulting aldehyde was protected as the dimethyl acetal 78 with methyl orthoformate. This intermediate could be easily elaborated to “western half” 79 in five steps, delivering not only the oxidized C18 methyl group but also the Δ14 moiety. For the eastern region of the molecule, a Schönecker oxidation33 was employed to activate the C12 methylene and install the 12β-hydroxyl group. Similar to the cyclopamine synthesis, trans-androsterone (50) was used and condensed to give the 2-picolylimine. Treatment with copper(II) triflate and benzoin followed by molecular oxygen gave the necessary 12β-hydroxy compound 81, which was further elaborated to the eastern half (82) of the molecule in 14 steps. Thus, cephalostatin 1 (11) was successfully completed by developing a unsymmetric dimerization reaction, as well as innovative reactions to install challenging “oxidase” functionality onto commercially available steroid skeletons.

3.5. Cortistatins

The cortistatins (especially cortistatin A (12)) possess highly desirable biological activity, most important of which is the inhibition of angiogenesis.10 Although the structure of the cortistatins was only disclosed in 2006, syntheses from several different research groups have been disclosed, the first of the syntheses being published in 2008. Due to the vast quantity of research done in this area as well as other reviews that have already addressed these syntheses, they will not be covered in appreciable detail in this review. However, these syntheses are a wonderful study from the vantage point of biomimetic, semisynthetic, and abiotic approaches towards these molecules. As has been demonstrated previously, C–H functionalization and biomimetic rearrangements that mimic those occurring in the biosynthetic oxidase phase, have been key to the evolution of the synthesis of steroid-alkaloids, and cortistatins are no exceptions to this trend. (For syntheses and reviews please see reference 44 and references therein.)

4. Diterpenoid Alkaloids

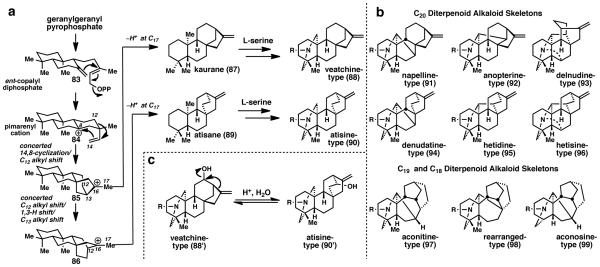

Diterpenoid-alkaloids are derived from the kaurane and atisane diterpenoid families. While the biosynthesis of these diterpenoids is generally understood, specific details of the biosynthetic processes are still unclear.1,45 Most recently, Tantillo and co-workers proposed a biosynthetic hypothesis that did not invoke secondary carbocations (Fig. 4a). 46 As had been previously proposed and confirmed by the isolation of ent-copalyl diphosphate (83), these molecules originate from geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, which is cyclized under enzymatic mediation. Next, generation of the pimarenyl cation (84) occurs via loss of pyrophosphate and cyclization. Tantillo then proposed that a series of concerted shifts occur to first generate tertiary carbocation 85, which, after elimination of a proton, gives the kaurane skeleton (87). Alternatively, tertiary carbocation 85 can undergo another set of concerted rearrangements to give a new tertiary carbocation (86), which provides the atisane skeleton (89) after proton elimination (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Proposed biosynthetic pathway for the production of diterpene alkaloids. (b) Commonly occurring kaurane– and atisane–type diterpene alkaloid skeletons found in Nature. (c) Hypothetical conversion between skeletons.

These hydrocarbon skeletons are then oxidized and a nitrogen atom derived from L-serine is incorporated into the molecule in the form of β-aminoethanol45a to subsequently form a piperidine ring. In the kaurane (87) series, this forms the skeleton of veatchine-type C20 terpenoid-alkaloids (88), and in the atisane (89) series the atisine-type skeleton (90) is formed. Subsequently, further oxidations can occur and more complex C20 diterpenoid-alkaloid skeletons can form (Fig. 4b), as well as loss of carbon atom(s) to form C19 and C18 diterpenoid-alkaloids. To further complicate these complex biosynthetic pathways, the veatchine (88’) and atisine (90’) skeletons can theoretically interconvert (Fig. 4c) making precise determinations in the biosynthetic route nearly impossible to decipher.

Of the nearly eighty C18-diterpenoid alkaloids reported as of July 2008, with lappaconitine being the first reported member of this family in 1922,47 not a single one has yet been prepared by total synthesis. Currently, the biological activity profiles of C18 diterpenoid-alkaloids remain unexplored, with the only exception being lappaconitine itself: it has been profiled and clinically developed as both an antiarrhythmic and non-narcotic analgesic drug.48,49 Interestingly, Wang et al.50 report that lappaconitine may prevent arrhythmias induced by aconitine—a related C19-diterpenoid alkaloid.

As of July 2008, about 700 naturally occurring C19-diterpenoid alkaloids had been identified. Aconite alkaloids are notorious, covert human poisons, however, other C19-diterpenoid alkaloids possess analgesic, anesthetic, antiarrhythmic, antifibrillatory, and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as the ability to repel insects.45b Like lappaconitine, some can counter the arrhythmic effects of aconitine poisoning and this has prevented death in animals poisoned with lethal doses of aconitine. 51,52 So far, only the work of Wiesner has resulted in the successful total syntheses of several C19-diterpenoid alkaloids possessing a variety of skeletons.

About 400 C20 diterpenoid-alkaloids have been isolated to date. They possess a broad range of bioactivity including analgesic, antiarrhythmic, antifibrillatory, and anti-inflammatory activity, as well as toxicity.1 Of all of the carbo-skeletons possessed by C20 diterpenoid-alkaloids, only atisine-, veatchine-, napelline, and hetisine-type alkaloids have been prepared via total synthesis. Although these molecules have been known for several decades, unlike triterpenoid-alkaloids, their cyclase phase skeletons are not easily replicated or commercially available. Thus, oxidation of these skeletons has not been well studied. This places the state of the art in synthesis logic for these systems somewhat behind that practiced for steroid-alkaloids. It is for this reason that pursuing a synthesis of these molecules has high potential to advance the field of organic chemistry.

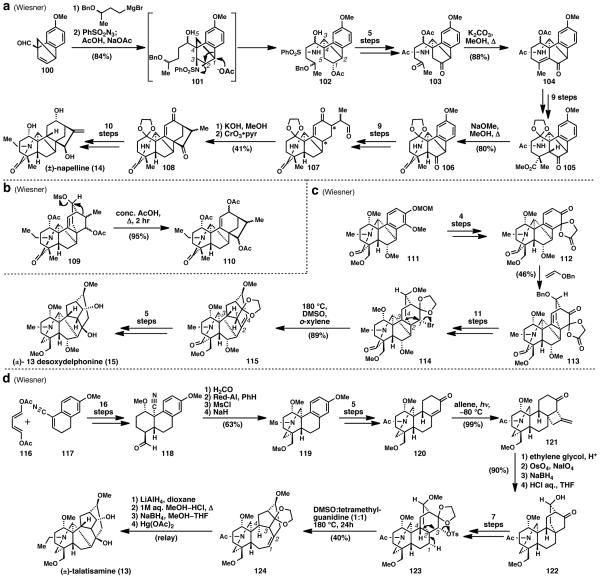

4.1. Wiesner Syntheses: Napelline (14), Deoxydelphonine (15), and Talatisamine (13)

The three diterpenoid-alkaloids that best highlight Wiesner’s landmark work on aconitine alkaloids are the C20 alkaloid napelline (14),53 and the C19 alkaloids deoxydelphonine (15)54 and talatisamine (13).55 The total synthesis of napelline (Scheme 4a) commences from aldehyde 100. Grignard addition followed by aziridination with phenyl sulfonyl azide gives phenyl sulfonyl aziridine 101. This compound is directly treated with acetic acid and sodium acetate, which induces acetolysis and rearrangement to sulfonamide 102. Sulfonamide 102 was then carried forward to diketone 103 and underwent aldol condensation in the presence of potassium carbonate in methanol to form the A-ring of napelline (104). In 9 steps, this material was converted to methyl ester 105, which, upon treatment with sodium methoxide, formed the lactone ring in the pentacyclic structure of napelline (106). An additional 9 steps afforded enone-aldehyde 107. Heating in methanol with potassium hydroxide caused a vinyligous aldol condensation to close the sixth and final ring in napelline (14). Oxidation then gave diketone 108 which was converted to (±)-napelline (14) in 10 steps. In a later study,53c the Wiesner group was able to convert a molecule with the atisane-based denudatine skeleton (109) to the kaurane-based napelline skeleton (110), by heating in acetic acid (Scheme 4b) via a process similar to the proposed biomimetic transformation shown in Fig. 4c.

Scheme 4.

A similar biomimetic conversion between different natural product skeletons was demonstrated in Wiesner’s synthesis of 13-desoxydelphinone (15) (Scheme 4c).54 Advanced intermediate 111 was dearomatized to generate conjugated dienone 112 in four steps. Cycloaddition with benzyl vinyl ether gave [2.2.2]bicyclic system 113, which closely resembles the denudatine skeleton in the atisane series (Fig. 4b). In 11 steps, this compound was converted to ketal 114. This advanced, highly oxidized intermediate was then heated in a mixture of DMSO and o-xylene to invoke a rearrangement to the needed aconitine skeleton (115) in an impressive 89% yield. Such a transformation may indeed be biomimetic in nature. This rearrangement product was quickly elaborated to (±)-13-desoxydelphinone (15) in five additional steps.

Another aconitine alkaloid, talatisamine (13) (Scheme 4d), was synthesized featuring a similar rearrangement.55 Starting from diene 116 and nitrile 117, tricycle 118 was synthesized in 16 steps. This compound underwent formylation and reduction to give a primary alcohol from the aldehyde and a primary amine from the nitrile. Treatment with mesyl chloride then provided a triply mesylated product. Deprotonation of the sulfonamide led to displacement of the proximal mesylate to form 119, which contains the piperidine ring of talatisamine (13). Compound 119 was then converted to enone 120 in five steps, after which it underwent photoaddition with allene to give the [2+2] photoadduct 121 in nearly quantitative yield. Ethylene glycol protection followed by oxidative cleavage of the terminal olefin gave a cyclobutanone, which was reduced with sodium borohydride to give a cyclobutanol as a mixture of diastereomers. Deprotection of the ketal with acid caused an immediate retro-aldol/aldol process to give the [2.2.2] system in compound 122. In seven steps, this compound was carried forth to compound 123. This intermediate was then rearranged, in a similar manner to compound 114, with heating in DMSO and tetramethylguanidine to convert the atisine-like skeleton in 123 to the aconitine-like skeleton in 124. This racemic relay synthesis was completed from an intermediate obtained via degradation of the natural product.

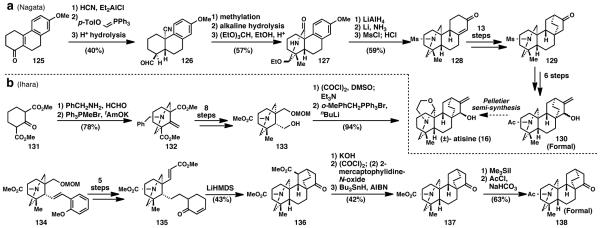

4.2. Atisine (16) (Nagata, 1963; Ihara, 1988)

Atisine (16) is the archetypal and least oxidized atisine-type alkaloid. Its first total synthesis was completed in 1963 by Nagata56 and constituted a formal total synthesis by intercepting Pelletier’s intermediate from a prior semisynthesis in 1956.57 Several syntheses followed, but the most recent was reported by Ihara 25 years later in 1988.58 In Nagata’s synthesis, hydrogen cyanide was added to enone 125 via a 1,4-addition. Wittig olefination provided the vinyl p-tolylether, which was hydrolyzed to give the formyl group in compound 126. Methylation followed by alkaline hydrolysis and ethylation provided epimeric ethoxy lactam 127. Lactam 127 was reduced with lithium aluminum hydride and then further reduced with lithium and ammonia. Hydrolysis of the resulting vinyl methyl ether with concomitant isomerization of the olefin gave enone 128 after sulfonamide formation. From enone 128, 13 steps were required to reach ketone 129, which contained the [2.2.2] system in atisine (16). Another 6 steps provided the correct functionality on allylic alcohol 130. Compound 130 intercepted Pelletier’s intermediate.

Ihara’s synthesis approached atisine (16) in a more convergent manner.58 Diester 131, in the presence of formaldehyde and benzylamine gave a piperidine via a double Mannich reaction. Wittig methylenation provided the exocyclic olefin in intermediate 132, which was converted to primary alcohol 133 in eight steps. Swern oxidation and another Wittig reaction gave trans-olefin 134 and was elaborated to the key substrate 135 in five subsequent steps. Treatment of this compound with lithium hexamethyldisilazide affected a double-Michael addition to give the nearly completed atisine skeleton 136 in 43% yield. From 136, radical decarboxylation, deprotection and acetylation gave ketone 138, which also intercepted one of Pelletier’s intermediates and constituted a formal total synthesis. This synthesis demonstrates the efficiency of convergence in synthesis as well as the ability to rapidly generate complexity by carefully crafting tandem reactions.

While both of these syntheses reach the same target, 25 years of advancement in synthesis led to a more convergent, simplified, and ideal synthesis. In 2013 another 25 years will have passed, and perhaps an even more ideal route to these molecules will present itself—one that has the ability to construct other atisine-type natural products.

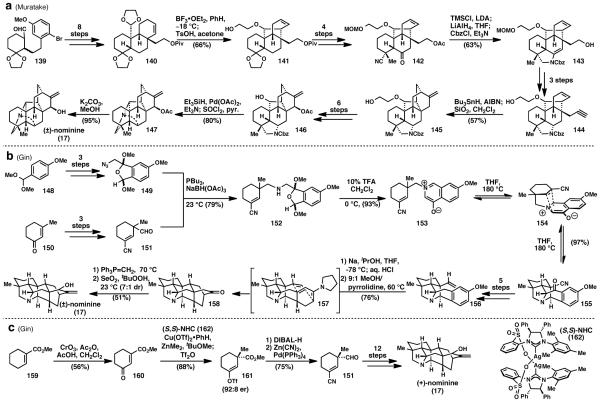

4.3. Nominine (17) (Muratake, 2004; Gin, 2006)

Nominine (17) is a hetisine-type C20 diterpenoid alkaloid. While being less oxidized than other members of the hetisine family, it still possesses one of the most complex skeletons presented by diterpenoid-alkaloids.1 It was among the first hetisine alkaloids reported in 1956 by Saito et.al. 59 The first total synthesis of this molecule, which was also the first total synthesis of a hetisine alkaloid was completed almost 50 years later by the Muratake group in 2004.60 The second, and only other, synthesis was reported by Gin and Peese in 2006. 61 No other hetisine alkaloids have been synthesized to date.

Muratake’s synthesis (Scheme 6a) commenced from 139, which after an eight step sequence was elaborated to key intermediate 140.60 Treatment with boron trifluoride etherate effected an acetal-ene reaction, which forged the C14-C20 bond in nominine (17). The resulting alcohol was carried onto ketone nitrile 142. Formation of the corresponding silyl enol ether and reduction of the nitrile to the primary amine, followed by cyclization and Cbz-protection gave 143 and created the necessary N–C6 bond. The primary alcohol is converted to a terminal alkyne (144) and a 6-exo radical cyclization is effected with tributyltin hydride and AIBN, thereby forming the [2.2.2] bicyclic system in 145 with the exocyclic olefin already in place. Conversion of 145 to the secondary alcohol 146 then allowed Muratake to form the N–C14 bond via deprotection of the Cbz-protected amine and displacement, thus completing the skeleton of nominine (17). Deprotection of the acetyl group unveiled (±)-nominine (17) in 40 steps overall.

Scheme 6.

Gin’s synthesis employed a completely abiotic, convergent approach.61 Azide 149, available in 3 steps from acetal 148, and aldehyde 151, obtained in 3 steps from 150, were joined via reductive amination to give amine 152. Treatment with acid induced a condensation to form zwitterion 153, which underwent an intramolecular [2+3] dipolar cycloaddition when heated in THF. While two products originally form based of the face of attack by the dipole (as shown on compound 154), the mixture can be funnelled into the desired product (155) in good yield. In five steps, this cycloadduct was converted to olefin 156. Birch reduction, followed by an acid induced isomerization and enamine formation, led to an intramolecular Diels– Alder reaction which formed the [2.2.2] bicyclic system in product 158. These two remarkable cycloaddition reactions were able to form all of the daunting C–C and C–N bonds present in nominine (17) including the C14–C20, N–C6, and N–C14 bonds. Wittig methylenation and allylic oxidation with selenium dioxide provided (±)-nominine (17) in 15 steps overall. This route was later rendered enantioselective by preparing enantioenriched intermediate 151 (Scheme 6c).62 The key step for this endeavour was an asymmetric conjugate addition developed by Hoveyda63 employing the (S,S)-NHC (162) catalyst shown above to give vinyl triflate 161. This compound was elaborated to yield the previously synthesized aldehyde 151 in optically pure form. From this intermediate, the same synthetic route was followed with effective stereochemical relay to form all the remaining stereocenters in the molecule in a diastereoselective fashion. Thus, the first enantioselective synthesis of (+)-nominine (17) was completed in a total of 16 steps.

5. Outlook

“...you can really go much too long a distance when you try to use vigorously unnatural chemistry to make a natural compound. Nature did not have so much freedom in producing her natural products.” – Albert Eschenmoser

In this review, we have taken a broad view of the biosynthesis and total synthesis of terpenes that, through a “twist” of fate, have emerged as alkaloids. These so-called terpenoid-alkaloids have been a wellspring of inspiration and discovery for chemists and biologists alike. As the wise quote from Eschenmoser mentions, much can be learned from Nature’s synthesis of these molecules. Heathcock’s two approaches to the Daphniphyllum alkaloids demonstrate this wisdom while Gin’s landmark synthesis of nominine (17) shows how a completely abiotic approach can also be incredibly efficient. Future efforts in this area may well benefit from capitalizing on both the overall logic of biosynthesis (i.e. the big picture) and the invention-oriented spirit of a retrosynthetic analysis predicated on novel disconnections.

Scheme 5.

References

- [1].Wang F-P, Liiang X-T. In: The Alkaloids, Chemistry and Biology. Cordell GA, editor. Vol. 59. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 2002. pp. 1–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Maimone TJ, Baran PS. Nat. Chem. Bio. 2007;3:396–407. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Baggaley KH, Roberts AD, Szabo LF. In: Dictionary of Alkaloids. 2nd Buckingham J, editor. CRC Press; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang F-P, Chen Q-H, Liu X-Y. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:529–570. doi: 10.1039/b916679c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pfister JA, Gardner DR, Panter KE, Manners GD, Ralphs MH, Stegelmeier BL, Schoch TK. J. Nat. Toxins. 1999;8:81–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ulubelen A, Meriçli AH, Meriçli F, Kilinçer N, Ferizli AG, Emekci M, Pelletier SW. Phytother. Res. 2001;15:170–171. doi: 10.1002/ptr.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Zafar S, Ahmad MA, Siddiqui TA. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;78:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rahman S, Khan RA, Kumar A. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2002;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-2-6. 1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zafar S, Ahmad MA, Siddiqui TA. Fitoterapia. 2002;73:553–556. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yang X, Wang G, Ling S, Qiu N, Wang G, Zhu J, Lie J. J. Chromatogr., B: Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2000;740:273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Devkota KP, Lenta BN, Fokou PA, Sewald N. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008;25:612–630. doi: 10.1039/b704958g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li H-J, Jiang Y, Li P. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006;23:735–752. doi: 10.1039/b609306j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ata A, Andersh BJ. In: The Alkaloids, Chemistry and Biology. Cordell GA, editor. Vol. 66. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 2008. pp. 191–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Aoki S, Watanabe Y, Sanagawa M, Setiawan A, Kotoku N, Kobayashi M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3148–3149. doi: 10.1021/ja057404h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Watanabe Y, Aoki S, Tanabe D, Setiawan A, Kobayashi M. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4074–4079. [Google Scholar]; c) Aoki S, Watanabe Y, Tanabe D, Setiawan A, Arai M, Kobayashi M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:4485–4488. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pettit GR, Inoue M, Kamano Y, Herald DL, Arm C, Dufresne C, Christie ND, Schmidt JM, Doubek DL, Krupa TS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:2006–2007. [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Bello-Ramírez AM, Buendia-Orozco J, Nava-Ocampo AA. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003;17:575–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bello-Ramírez AM, Nava-Ocampo AA. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;18:699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bello-Ramírez AM, Nava-Ocampo AA. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;18:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Turabekova MA, Rasulev RB. Molecules. 2004;9:1194–1207. doi: 10.3390/91201194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Turabekova MA, Rasulev RB, Dzhakhangirov FN, Salikhov SI. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008;25:310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ishihara Y, Baran PS. Synlett. 2010;12:1733–1745. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yagi S. Kyoto Igaku Zasshi. 1909;6:208–222. [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Sakabe N, Irikawa H, Sakurai H, Hirata Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1966;7:963–964. [Google Scholar]; b) Sakabe N, Hirata Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1966;7:965–968. [Google Scholar]; c) Yamamura S, Irikawa H, Hirata Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;8:3361–3364. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Irikawa H, Sakabe N, Yamamura S, Hirata Y. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:5691–5700. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(68)88167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kobayashi J, Kubota T. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:936–962. doi: 10.1039/b813006j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Heathcock CH, Davidsen SK, Mills S, Sanner MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:5650–5651. [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Ruggeri RB, Hansen MM, Heathcock CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:8734–8736. [Google Scholar]; b) Ruggeri RB, McClure KF, Heathcock CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:1530–1531. [Google Scholar]; c) Ruggeri RB, Heathcock CH. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:3714–3715. [Google Scholar]; d) Stafford JA, Heathcock CH. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:5433–5434. [Google Scholar]; e) Heathcock CH, Davidsen SK, Mills SG, Sanner MA. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2531–2544. [Google Scholar]; f) Heathcock CH, Hansen MM, Ruggeri RB, Kath JC. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2544–2553. [Google Scholar]; g) Heathcock CH, Piettre S, Ruggeri RB, Ragan JA, Kath JC. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2554–2566. [Google Scholar]; h) Heathcock CH, Stafford JA. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2566–2574. [Google Scholar]; i) Heathcock CH, Stafford JA, Clark DL. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2575–2585. [Google Scholar]; j) Heathcock CH, Ruggeri RB, McClure KF. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2585–2594. [Google Scholar]; k) Heathcock CH, Kath JC, Ruggeri RB. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:1120–1130. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Heathcock CH, Joe D. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:1131–1142. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Denmark SE, Baiazitov RY. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:593–605. doi: 10.1021/jo052001l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Stork G, Burgstrahler AW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:5068–5077. [Google Scholar]; b) Eschenmoser A, Ruzicka L, Jeger O, Arigoni D. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1955;38:1890–1904. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Johnson WS, Gravestock MB, McCarry BE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:4332–4334. doi: 10.1021/ja00746a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Surendra K, Corey EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13928–13929. doi: 10.1021/ja906335u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Corey EJ, Hertler WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81:5209–5212. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Giannis A, Heretsch P, Sarli V, Stößel A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7911–7914. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shenvi RA, Guerrero CA, Shi J, Li C-C, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7241–7243. doi: 10.1021/ja8023466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Jeong JU, Sutton SC, Kim S, Fuchs PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10157–10158. [Google Scholar]; b) LaCour TG, Guo C, Bhandaru S, Boyd MR, Fuchs PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1998;120:692–707. [Google Scholar]; c) Jeong JU, Guo C, Fuchs PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2071–2084. [Google Scholar]; d) Lee S, Fuchs PL. Org. Lett. 2002;4:317–318. doi: 10.1021/ol016572l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Phillips ST, Shair MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6589–6598. doi: 10.1021/ja0705487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Fortner KC, Kato D, Tanaka Y, Shair MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:275–280. doi: 10.1021/ja906996c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Grinsteiner TJ, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron Letters. 1994;35:8333–8336. [Google Scholar]; b) Grinsteiner TJ, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron Letters. 1994;35:8337–8340. [Google Scholar]; c) Kurosu M, Marcin LR, Grinsteiner TJ, Kishi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:6627–6628. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Haworth RD, McKenna J, Powell RG, Whitefield GH. Chemistry & Industry. 1952:215–216. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Buchschacher P, Kalvoda J, Arigoni D, Jeger O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1958:2905–2906. [Google Scholar]

- [31].a) Hofmann AW. Ber. 1883;16:558–560. [Google Scholar]; b) Hofmann AW. Ber. 1885;18:5–23. [Google Scholar]; c) Hofmann AW. Ber. 1885;18:109–131. [Google Scholar]; d) Löffler K, Freytag C. Ber. 1909;42:3427–3431. [Google Scholar]

- [32].a) Barton DHR, Beaton JM, Geller LE, Pechet MM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:2640–2541. [Google Scholar]; b) Barton DHR, Beaton JM. J. Am.Chem. Soc. 1960;82:2641. [Google Scholar]; c) Barton DHR, Beaton JM, Geller LE, Pechet MM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961;83:4076–4083. [Google Scholar]; d) Akhtar M, Barton DHR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:1528–1536. [Google Scholar]; e) Breslow R, Baldwin SW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970;92:732–734. [Google Scholar]; f) Breslow R, Scholl PC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:2331–2333. [Google Scholar]; g) Breslow R, Corcoran RJ, Snider BB, Doll RJ, Khanna PL, Kaleya R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:905–915. doi: 10.1021/ja00445a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schönecker B, Zheldakova T, Liu Y, Kötteritzsch M, Günther W, Görls H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:3240–3244. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shibanuma Y, Okamoto T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985;33:3187–3194. [Google Scholar]

- [35].James LF, Panter KE, Garrield W, Molyneux RJ. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:3211–3230. doi: 10.1021/jf0308206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Johnson WS, Cox JM, Graham DW, Whitlock HW., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:4524–4526. [Google Scholar]

- [37].a) Masamune T, Tagasugi M, Murai A, Kobayashi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:4521–4523. [Google Scholar]; b) Masamune T, Mori Y, Takasagi M, Murai A, Ohuchi S, Sato N, Katsui N. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1965;38:1374–1378. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.38.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].a) Marki F, Witkop B. Experientia. 1963;19:329–338. doi: 10.1007/BF02152303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kaly JW, Witkop B, Bommer P, Biemann K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:124–126. doi: 10.1021/ja01079a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Tokuyama T, Daly JW. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:41–47. [Google Scholar]; d) Dumbacher JP, Beehler BM, Spande TF, Garraffo HM, Daly JW. Science. 1992;258:799–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1439786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Albuquerque EX, Daly JW, Witkop B. Science. 1971;172:995–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3987.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tokuyama T, Daly JW, Witkop B, Karle IL, Karle J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:1917–1918. doi: 10.1021/ja01009a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Garst ME, Spencer TA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:250–252. [Google Scholar]

- [42].a) Heathcock CH, Smith SC. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:6828–6839. [Google Scholar]; b) Drögemüller M, Jautelat R, Winterfeldt E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1996;35:1572–1574. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bladon P, McMeekin W, Williams IA. J. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:5727–5737. [Google Scholar]

- [44].a) Nicolaou, Sun Y-P, Peng X-S, Polet D, Chen DY-K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7310–7313. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shenvi RA, Guerrero CA, Shi J, Li C-C, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7241–7243. doi: 10.1021/ja8023466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lee HM, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Shair MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16864–16866. doi: 10.1021/ja8071918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Flyer AN, Si C, Myers AG. Nature Chemistry. 2010;2:886–892. doi: 10.1038/nchem.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yamashita S, Kitajima K, Iso K, Hirama M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:3277–3279. [Google Scholar]; f) Simmons EM, Hardin-Narayan AR, Guo S, Sarpong R. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4696–4700. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Nising CF, Bräse S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:9389–9391. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Sarpong R. Nature Chemistry. 2010;2:803–804. doi: 10.1038/nchem.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].a) Zhao P-J, Gao S, Fan L-M, Nie J-L, He H-P, Zeng Y, Shen Y-M, Hao X-J. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:645–649. doi: 10.1021/np800657j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang F-P, Chen Q-H. In: The Alkaloids, Chemistry and Biology. Cordell GA, editor. Vol. 69. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 2009. pp. 1–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hong YJ, Tantillo DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5375–5386. doi: 10.1021/ja9084786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schudze H, Ulfert F. Arch. Pharm. 1922;260:230–243. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Dzhakhangirov FN, Sokolov F, Verkhratskii AN. Allapinin-A New Antiarrhythmic Drug of Plant Origin, (Fan, Tashkent, Russia) 1993 [Google Scholar]

- [49].a) Liu JH, Zhu XY, Tang XC. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 1987;8:301–305. [Google Scholar]; b) Go X, Tang XC. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 1989;10:504–507. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wang PD, Ma XM, Zhang HL, Yang YM. Chin. Pharmacol. Bull. 1997;13:265–271. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Dzhakhangirov FN, Sultankhodzhaev MN, Tashkhodzha B, Salimov BT. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1997;33:190–202. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Salimov BT, Kuzibaeva ZK, Dzhakhangirov FN. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1996;32:366–368. [Google Scholar]

- [53].a) Wiesner K, Ho P-T, Tsai CSJ(P) Can. J. Chem. 1974;52:2353–2355. [Google Scholar]; b) Wiesner K, Ho P-T, Tsai CSJ(P), Lam Y-K. Can. J. Chem. 1974;52:2355–2357. [Google Scholar]; c) Sethi SP, Atwal KS, Marini-Bettolo RM, Tsai TYR, Wiesner K. Can. J. Chem. 1980;58:1889–1891. [Google Scholar]

- [54].a) Lee S-F, Sathe GM, Sy WW, Ho P-T, Wiesner K. Can. J. Chem. 1976;54:1039–1051. [Google Scholar]; b) Tsai TYR, Nambiar KP, Krikorian D, Botta M, Marini-Bettolo R, Wienser K. Can. J. Chem. 1979;57:2124–2134. [Google Scholar]; c) Wiesner K, Tsai TYR, Nambiar KP. Can. J. Chem. 1978;56:1451–1454. [Google Scholar]

- [55].a) Wiesner K, Tsai TYR, Huber K, Bolton SE, Vlahov R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:4990–4992. [Google Scholar]; b) Wiesner K. Pure Appl. Chem. 1975;41:93–112. [Google Scholar]

- [56].a) Nagata W, Sugasawa T, Narisada. T. Wakabayashi M, Hayase Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:2342–2343. [Google Scholar]; b) Nagata W, Sugasawa T, Narisada. T. Wakabayashi M, Hayase Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:1483–1499. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Pelletier SW, Jacobs WA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:4144–4145. [Google Scholar]; b) Pelletier SW, Parthasarathy PC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1963;4:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- [58].a) Ihara M, Suzuki M, Fukumoto K, Kametani T, Kabuto C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1963–1964. [Google Scholar]; b) Ihara M, Suzuki M, Fukumoto K, Kabuto C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:1164–1171. [Google Scholar]

- [59].a) Ochiai E, Okamoto T, Sakai S-I, Saito A. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1956;76:1414–1418. [Google Scholar]; b) Sakai S, Yamamoto I, Yamaguchi K, Takayama H, Ito M, Okamoto T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 30:4579–4582. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Muratake H, Natsume M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4646–4649. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Peese KM, Gin DY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8734–8735. doi: 10.1021/ja0625430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Peese KM, Gin DY. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:1654–1665. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Brown MK, May TL, Baxter CA, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1097–1100. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]