Abstract

The persistence of natural metapopulations may depend on subpopulations that exist at the edges of species ranges, removed from anthropogenic stress. Mesophotic coral ecosystems (30–150 m) are buffered from disturbance by depth and distance, and are potentially massive reservoirs of coral diversity and fecundity; yet we know little about the reproductive capabilities of their constituent species and the potential for these marginal environments to influence patterns of coral reef persistence. We investigated the reproductive performance of the threatened depth-generalist coral Orbicella faveolata over the extent of its vertical range to assess mesophotic contributions to regional larval pools. Over equal habitat area, mesophotic coral populations were found to produce over an order of magnitude more eggs than nearby shallow populations. Positive changes with depth in both population abundance and polyp fecundity contributed to this discrepancy. Relative larval pool contributions of deeper living corals will likely increase as shallow habitats further degrade due to climate change and local habitat degradation. This is a compelling example of the potential for marginal habitat to be critical to metapopulation persistence as reproductive refugia.

Reproductive performance can influence patterns of population persistence across a species’ range, and thus, understanding how reproductive performance changes across environmental gradients is central to the study of evolutionary ecology and to the successful management of natural populations and threatened species1. Species range is often used as a biogeographic term, describing the large scale limits of a species distribution over the two-dimensional surface of the earth, and often in reference to latitudinal clines2,3. The conventional understanding, termed Brown’s Principle, suggests that favorable environmental conditions near the center of a species’ biogeographic range results in higher individual reproductive success and, subsequently, higher population abundance than towards the edges of a biogeographic range4. However, not all species distributions follow this “abundant center” pattern, with many showing higher densities towards a range margin, or heterogeneous densities throughout the range5,6,7. Additionally, high adult abundances may not always be coupled with high individual performance and reproductive capacity8. This may be particularly true in marine species that possess a pelagic larval phase capable of dispersing larvae over large distances, and for which population densities may be influenced more by oceanographic conditions affecting connectivity and recruitment than by local environmental conditions and adult reproductive performance7,9.

For many species, biophysical characteristics that influence fitness and distribution can vary more dramatically over short vertical distances, such as elevation or depth, than they do over large horizontal distances. Again, there may be a supposition that individual performance should be maximum near the centers of vertical species ranges4,10. However, Brown’s Principle is not always immediately intuitive over vertical habitat ranges, particularly in the ocean where species distributions may be bounded by the sea surface, and resources such as light are maximum at this boundary. In light dependent corals it could be expected that individual success wanes at the deeper ends of species vertical ranges where critical resources, such as light, are more limiting. Yet we find that population abundance may be greatest at the deepest margins of the range in some light dependent coral species, such as Orbicella spp.11,12,13,14, and bimodal depth-related growth maxima have been observed in other depth-generalist species15.

Exceptions to Brown’s Principle may be of particular importance to coral reef persistence, as individuals at the edge of a species’ vertical range may become proportionately more important in declining populations. Shallow coral reefs are at escalating risk of habitat degradation16,17,18, yet mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) between 30 and 150 meters depth are buffered from many stressors, particularly coral thermal bleaching19,20,21. This observation, and the considerable overlap of scleractinian coral species between MCEs (30–50 m) and shallow reefs (<30 m) in the Caribbean (~70%;14), has given rise to the Deep Reef Refugia Hypothesis (DRRH)22,23, that posits a depth refugia for shallow water coral species and a stable pool of reproductively capable corals that could assist in shallow water recovery, thus increasing resilience after disturbance.

We know little about coral reproduction at MCE depths, including whether MCE corals are reproductively competent, how their reproductive effort changes with depth, and whether that reproductive effort results in successful recruitment or larval exchange22. The little available information largely suggests reduced fecundity with increasing depth. For example, in some brooding corals reproductive output decreases with depth, and this is likely due to phototrophic energy limitations24,25; however, this relationship may not be consistent for all brooding species in all locations26. Information regarding depth-fecundity relationships in broadcasting species is extremely rare and has not been accomplished in mesophotic depths, though no change in polyp-specific gamete production in the broadcasting species O. faveolata was found over the first half of its depth range (3–18 m)27. A decline in reproductive output with depth could suggest minimal MCE contributions to regional larval pools and diminish the validity of the DRRH. However, the high abundance of depth generalist coral species in MCE reefs combined with the observation that the extent of known MCEs is large14 and in some areas may surpass the total area of shallow water reefs (authors, unpub. data), could suggest high reproductive output despite potential light limitations. This may be especially true if energetic constraints are relaxed by increasing heterotrophy15,28. Indeed, there is potential that MCEs produce more coral gametes than shallow reefs depending on how abundance and reproductive capacity vary with depth.

Our study resolves the reproductive uncertainty over depth for the important—and recently listed as threatened29—Caribbean broadcast spawning coral Orbicella spp. in the US Virgin Islands (USVI) (Fig. 1) and makes estimates of depth-specific contributions to regional reproductive output. Unlike previous studies that have examined coral fecundity and depth at the scale of individual polyps or colonies, the current study expanded these parameters to make realistic estimates of the relative egg production of O. faveolata across its depth range by scaling ova production by population estimates. Our findings suggest that complex interacting environmental gradients and disturbance regimes complicate the application of Brown’s Principle in vertical marine environments, and challenge the assertion that coral growth optima and light saturation correlate to fecundity optima. Here we reaffirm the potential importance of mesophotic coral reefs as larval resources in regional metapopulations.

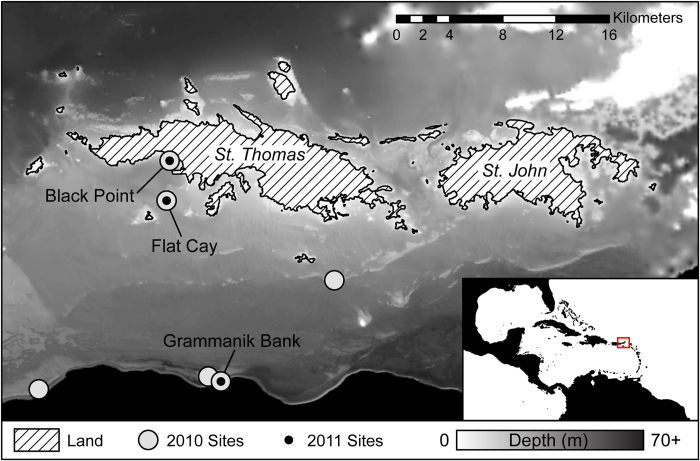

Figure 1. The northern US Virgin Islands of St. Thomas and St. John.

Considerable mesophotic habitat (30–150 m) exists on the broad insular platform, and well-mapped linear coral habitat exists on submerged banks near the shelf edge south of St. Thomas11,13,14. Sample sites from 2010 (gray) ranged in depth from 6–43 m. In 2011 a subset of 2010 sites were visited weekly for five weeks bracketing spawning in August: Black Point (5–10 m), Flat Cay (15–22 m), and Grammanik Bank (35–40 m). Map created using ArcGIS 10.

Results

Gametogenesis and fecundity

O. faveolata colonies sampled from three depths—shallow (5–10 m), mid-depth (15–22 m) and mesophotic (35–40 m) (n ≥ 25 over five weeks)—were found to contain both male and female gametes, which were visually indistinguishable by depth (Fig. 2). Spermaries of stages II-V and oocytes/ova of stages II–IV30 were identified in corals from all sites (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Stage I spermaries and oocytes were also observed at all sites; however, they are not included in this analysis due to difficulty in identification of these early stage gametes. Analysis of spermatogenesis suggested development from earlier stage spermaries in late July and early August to late stage mature spermaries prior to spawning at all sites (Fig. 3). Late stage spermaries were absent (lost) from coral tissues at all sites one week after full moon, which indicated these populations had spawned. In some cases, remnant stage V spermaries were observed with free spermatozoa in the mesentery, which is evidence of spawning behavior, and suggests these spermaries were residual after spawning occurred (the presence of remnant sperm is thus not represented in Fig. 3, also see Supplementary Fig. S2). Specifically, at the mesophotic site 60% of colonies contained stage V spermaries on the 19th of August, and by the 25th of August no colonies contained intact stage V spermaries. Both shallow and mid-depth sites experienced similar losses of stage V spermaries from 40% of colonies. Additional evidence of spawning was present in tissues from all sites in the last week of sampling, including wasted mesenteries. The presence of early stage spermaries increased in colonies at all sites late in August, suggesting a second spawn in September (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Histological cross-sections of fully fecund O. faveolata polyps just prior to spawning (week 4) from each site.

From left to right, in order of descending depth, Black Point (8 m), Flat Cay (19 m) and Grammanik Bank (39 m). In each example the polyp has at least 12 ripe gonads, all ova are stage IV (stained gold), and spermaries are stage V (stained red). Bar = 500 μm. See Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Fig. S3 for further reproductive structure identification.

Figure 3. O. faveolata gametogenic stages of spermaries (left column) and oocytes (right column) observed in histological sections collected weekly (July 28th to August 26th 2011, 5 sampling times) from three sites: a shallow near-shore site (red); an offshore island mid-depth site (green); and a mesophotic submerged bank site (blue).

Gametocytes were staged as I–V for spermaries and I–IV for oocytes33, however only stages II and later are shown. Plots represent the percentage of colonies that contained each stage. n = 5 or more for each date at each site. Note that colonies can simultaneously contain gametocytes of different stages. The lunar cycle is shown below the x-axis, as well as a black bar that represents expected spawning dates 6–9 days after full moon in August 2011.

By the first week of sampling in 2011 (just before new moon) over 75% of colonies from each site contained stage II oocytes (Fig. 3). Colonies rapidly lost stage II oocytes as they developed into stage III and IV oocytes/ova throughout the sampling period. This development was delayed but more rapid in mesophotic colonies (Figs 3 and 4). Histological evidence of spawning characterized by the loss of stage IV ova from coral tissue was seen in mesophotic colonies, of which 100% contained stage IV ova just prior to the time of expected spawning, and 60% contained stage IV ova one week later. A loss of stage IV ova was also observed in shallow colonies during this time. There was evidence of ova retention and development beyond the date of August 2011 spawning at all sites, again suggesting an additional September spawn.

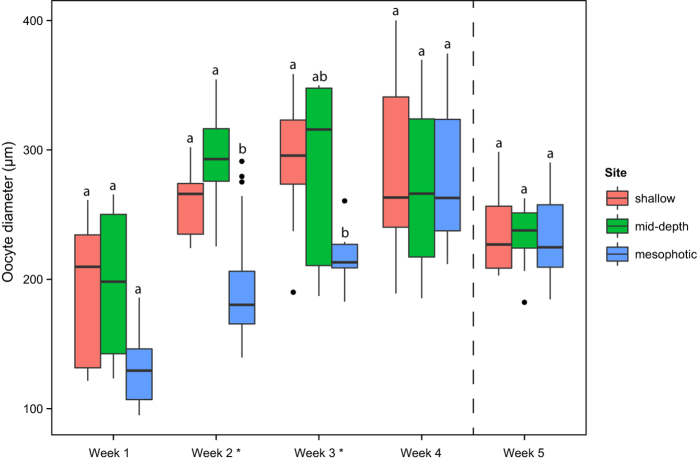

Figure 4. Boxplot of O. faveolata oocyte/ova diameters measured from histological sections from each site each sampling week.

Upper and lower hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles, bars correspond to medians and whiskers extend to the highest and lowest values within 1.5 IQR (inter-quartile range). Data beyond whiskers are outliers represented as dots. Significant differences between sites were found in weeks 2 and 3 (multiple comparisons from linear mixed effect models, step-wise adjusted; see Table 1 for more information and exact adjusted p-values). The dotted line denotes that spawning was expected between weeks 4 and 5. Oocytes (likely stage III) were retained beyond expected spawning in August at all sites.

Oocyte/ovum diameters were measured from ~3 random oocytes/ova in each of ~3 gravid polyps per colony. Oocyte diameters increased during the first three weeks of sampling at all sites. During weeks two and three, oocytes measured from mesophotic corals were significantly smaller than those from shallow corals, and significantly smaller than those from mid-depth corals in week two (multiple comparisons from linear mixed effect models within weeks, step-wise adjusted; see Table 1 for more information and exact adjusted p-values) (Fig. 4). However, by week four there were no significant differences in oocyte/ovum diameter between sites, and the same was true for week five, post August spawning. At week four, mean oocyte/ova diameters (±SD) for shallow, mid-depth and mesophotic corals were 283.36 μm (61.93), 265.77 μm (59.22), and 275.01 μm (45.60), respectively.

Table 1. Results of multiple comparisons among sites (depths) from linear mixed effects models of O. faveolataoocyte/ova diameters within weeks.

| Post-hoc comparison | Observations | Adjusted P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | shallow—mid-depth | 108 | 0.977 |

| mid-depth—mesophotic | 0.209 | ||

| shallow—mesophotic | 0.363 | ||

| Week 2 | shallow—mid-depth | 120 | 0.1166 |

| mid-depth > mesophotic | <0.0001* | ||

| shallow > mesophotic | 0.0047* | ||

| Week 3 | shallow—mid-depth | 105 | 0.9804 |

| mid-depth—mesophotic | 0.0621 | ||

| shallow > mesophotic | 0.0208* | ||

| Week 4 | shallow—mid-depth | 147 | 0.739 |

| mid-depth—mesophotic | 0.904 | ||

| shallow—mesophotic | 0.946 | ||

| Week 5 | shallow—mid-depth | 102 | 0.999 |

| mid-depth—mesophotic | 0.947 | ||

| shallow—mesophotic | 0.957 |

Note that spawning was evident between weeks 4 and 5. See also Fig. 4. Oocyte observations were nested within colonies to avoid pseudoreplication. Asterisks denote significant comparisons and a rejection of the null hypothesis of equal oocyte diameter between depths with an alpha of 0.05. p-values are step-wise adjusted.

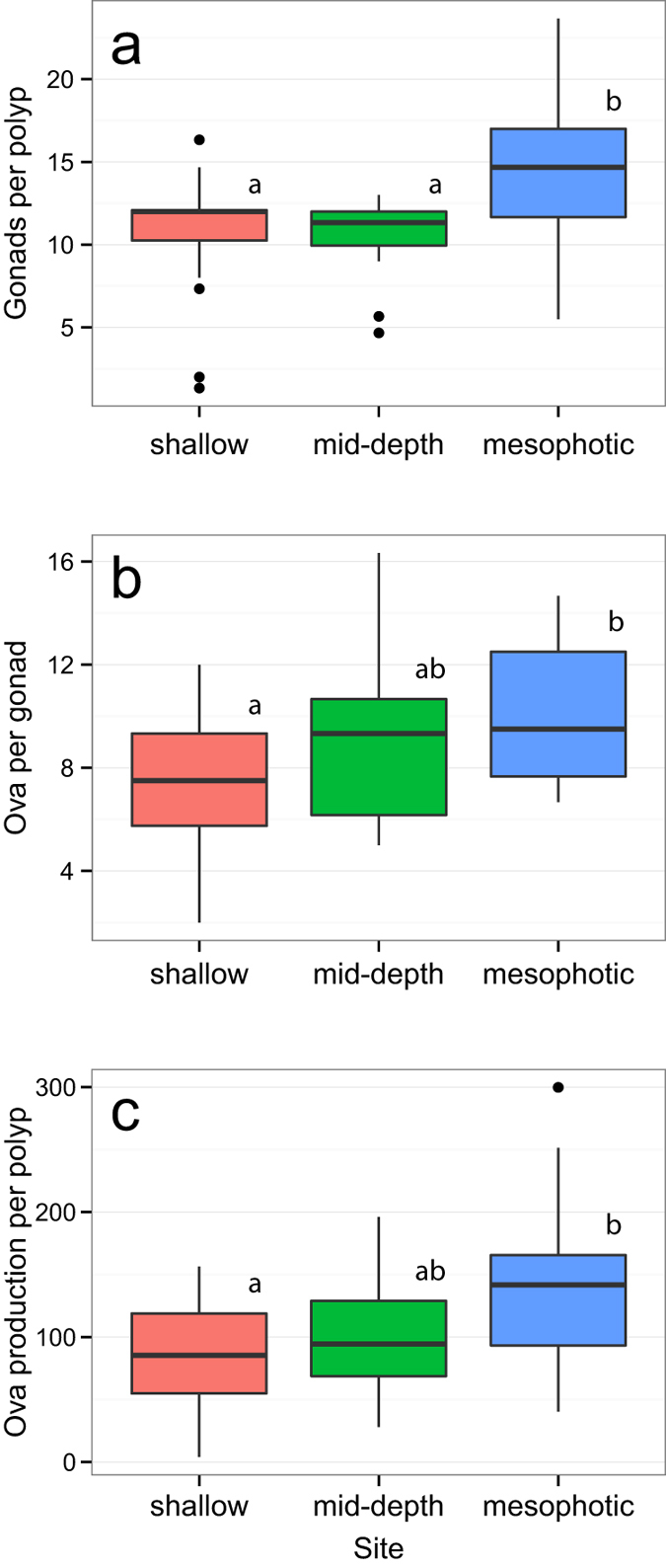

Fecundity per polyp was estimated as the product of the average number of gonads per polyp in cross-section and the average number of oocytes or ova per gonad in longitudinal section for 2–3 polyps per orientation per sample. The number of gonads per polyp, the number of oocytes/ova per gonad and the product of these two estimates were pooled between weeks 1 through 4 (pre-spawning samples). The pooled results were non-normal after log-transformation (Levene Tests, p > 0.5). The number of gonads per polyp is generally 12 (one gonad per septa), however mesophotic colonies had significantly more gonads per polyp than either shallow or mid-depth corals (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA/Bonferroni method, p = 0.0028; post-hoc comparison, mesophotic > mid-depth and mesophotic > shallow, p = 0.001 and 0.033, respectively) (Table 2, Fig. 5). Polyps from all sites were sometimes found to have as many as 24 gonads (two gonads per septa). The number of oocytes/ova per gonad generally ranged from 8–12 (maximum recorded was 19), however polyps in mesophotic corals had significantly more oocytes/ova per gonad than shallow corals (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA/Bonferroni method, p = 0.046; post-hoc comparison, p = 0.028) (Table 2, Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S3). There was no difference found in oocytes/ova per gonad between mesophotic and mid-depth colonies, or between mid-depth and shallow colonies.

Table 2. Fecundity estimates for each site in 2011.

| 2011 |

Site |

Mean (±SE) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Point (shallow) | Flat Cay (mid-depth) | Grammanik Bank (mesophotic) | Overall P | |

| Depth (m) | 5–10 | 15–22 | 35–40 | |

| Colonies | 20 | 20 | 19 | |

| Gonads*polyp−1 | 10.78 (±0.83)a | 10.58 (±0.48)a | 14.39 (±0.97)b | <0.01* |

| Ova*gonad−1 | 7.48 (±0.59)a | 9.19 (±0.72)ab | 9.91 (±0.60)b | 0.046* |

| Ova*polyp−1 | 87.05 (±10.10)a | 99.72 (±10.15)a | 144.43 (±15.91)b | 0.021* |

Data was pooled from weeks 1 through 4 of sampling (prior to expected spawning). Means and standard deviations are shown, however non-parametric significant differences between sites are noted by lowercase letters (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA/Bonferroni method, alpha = 0.05).

Figure 5. O. faveolata fecundity estimates and comparisons between 2011 study sites.

The number of (A) ripe gonads and the number of (B) oocytes/ova per gonad were estimated for three polyps per sample. Ova production per polyp (C) is the product of the number of ripe gonads multiplied by the number of oocytes/ova per gonad. Data was pooled from sampling weeks 1 through 4. Comparisons were made with Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs and the Bonferroni post-hoc method to arrive at adjusted p-values. Significant results are noted using lower-case letters in each boxplot (p < 0.05). See Fig. 4 for explanation of boxplot.

The product of gonads per polyp and ova per gonad provided an estimate of polyp fecundity, which was found to be heterogeneous across sites, with mesophotic corals having significantly higher oocyte/ovum production per polyp than shallow corals (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA/Bonferroni method, p = 0.021; post-hoc comparison, p = 0.009) (Table 2, Fig. 5). Again, no difference was found between mesophotic and mid-depth colonies, or mid-depth and shallow colonies; however, there was a significant increasing linear relationship between fecundity and depth (p < 0.001, R2 = 0.18, Fig. 6a). No significant relationship was found between oocyte/ovum production per polyp and the surface area of sampled colonies.

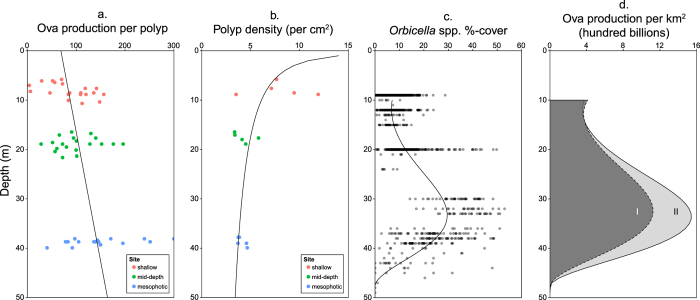

Figure 6. Regressions over depth of polyp fecundity, polyp-spacing, Orbicella spp. coral cover, and the resulting product which estimates the number of ova produced over a 1 km2 unit reef over depth.

(a) A significant positive linear relationship was found between per polyp ova production and depth (p = 0.001, R2 = 0.18). (b) Mid-depth and mesophotic corals were found to have similar polyp-spacing, whereas shallow corals had significantly higher polyp densities (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.012, N = 15). A significant negative linear relationship was found after log transformation (p = 0.014, R2 = 0.381). (c) Third degree polynomial model of Orbicella spp. coral cover versus depth (p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.51). Orbicella spp. cover is used as a proxy for O. faveolata cover. (d) Expected Orbicella spp. reproductive output from hypothetical 1 km2 USVI reefs over depth. (I) Assumes equal polyp fecundity over depth27 (96 eggs per polyp32); (II) assumes empirically estimated depth-specific fecundity.

Reproductive capability

The third order polynomial model fitted to Orbicella spp. coral cover versus depth (p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.51, Fig. 6c) indicates that coral cover increases with depth nonlinearly until ~30 m where it stabilizes at ~28% until a depth of ~40 m where coral cover begins to decline dramatically. By 50 m depth Orbicella spp. coral cover drops to zero. Shallow corals had significantly higher numbers of polyps per cm2 (on average, nearly twice) compared to both mid-depth and mesophotic corals, which were not significantly different from each other (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.012). The same data was log-transformed and a linear regression with depth was performed (p = 0.014, R2 = 0.381, Fig. 6b).

The resulting regression models from the previous three analyses (oocyte/ovum production per polyp, coral cover, and the number of polyps per cm2) were used to estimate the number of ova produced within a hypothetical 1 km2 reef area with increasing depth from 10–50 m (equation 2, Fig. 6). For comparison, an additional scenario assuming equal ova production at all depths was also estimated (Fig. 6d).

Ova production is estimated to be an order of magnitude greater at 35 m than at 10 m (1.146*1012, or over 300% more ova per km2). Higher fecundity in mesophotic corals resulted in 41% (443 billion) more ova produced per km2 at 35 m than a scenario assuming equal fecundity. Thus, higher mesophotic coral cover accounts for 163.5% (667 billion) more ova produced per km2 at 35 m compared to at 10 m.

Spawning observations

Video observations in the field in August and September 2012 showed mesophotic spawning in Orbicella spp. On August 11th, 9 nights after full moon, spawning was observed in an O. faveolata colony at 38 m at ~21:00. In addition, gamete bundles were observed in the water column. On the evening of September 7th (7 nights after full moon), a full-colony spawn of O. franksi was captured on video at ~38 m at 20:49 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Spawning behavior was also observed in O. faveolata partial colonies kept in the laboratory. On the evening of August 10th (8 nights after full moon) one mesophotic colony of ten released gamete bundles at ~21:00, and one shallow colony of ten released gamete bundles about 2 hours later at ~23:00. These were not whole-fragment spawns. On September 7th (7 nights after full moon) four of ten mesophotic colonies and three of ten shallow colonies released gamete bundles in whole-fragment spawns. Mesophotic colonies released gametes between 20:00 and 20:45, whereas shallow colonies released gametes between 21:45 and 22:30, with “dribbles” occurring as late as 23:20.

Discussion

Depth provides a reproductive refuge for a threatened depth-generalist coral species in the Caribbean. Our study suggests that MCEs in the USVI have far greater orbicellid gamete output per area than nearby shallow water reefs, despite reduced solar radiation and contrary to established relationships for some brooding corals. USVI orbicellid abundance and reproductive capacity throughout its vertical range appears to be an exception to Brown’s Principle, and USVI MCEs may be a compelling example of poorly understood marginal habitat that is crucial to population persistence. By resolving the depth-fecundity relationship for O. faveolata, we have addressed an information gap in evaluating the potential for MCEs to serve as refugia for this species22,23,31.

A novel result of this study was that mesophotic O. faveolata coral polyps were in fact more fecund than shallower corals, and that fecundity increased linearly with depth. No differences in the number of gonads per polyp or the number of oocytes per gonad were found between shallow (5–10 m) and mid-depth (15–22 m) sites, corroborating previous findings27, and in these depths O. faveolata fecundity estimates fell within the ranges recorded by previous studies27,32,33,34. However, the highest estimated fecundities in this study—all from MCE corals—nearly doubled previously recorded maximum values, and fecundity estimates were significantly greater in MCE corals than in shallow corals.

There are three potential explanations for the less than intuitive depth-fecundity relationship found in this study that appears to violate Brown’s Principle. First, it is possible that environmental conditions conducive to reproductive energy allocation in this species are decoupled from light saturation. Energy may not be limiting at depth, as assumed based on the sharply attenuated light fields in mesophotic environments. The Caribbean coral Madracis mirabilis showed bimodal growth in Jamaica, with peaks in shallow water (10 m) and at mesophotic depths (30 m)15. The latter peak in growth corresponded with the summer chlorophyll maximum layer depth at the first thermocline, which may have offered a consistent source of heterotrophically derived energy. Although heterotrophy has been shown to be insufficient to meet total metabolic needs in shallow O. faveolata35, mesophotic Orbicella spp. in the USVI are associated with the chlorophyll maximum layer before and during reproductive periods and bottom currents can be stronger than in shallow water habitats, potentially increasing advective food supply14. In addition, temperatures are lower in mesophotic environments by 1 °C or more during reproductive periods14, which could lower metabolic demands and allow more investment in reproduction. Thus, Orbicella spp. in mesophotic environments of the Caribbean may be less energetically limited than shallow water corals, which could enable them to allocate relatively more energy into reproduction. The same may apply to other coral species in mesophotic environments associated with the first thermocline.

A second non-exclusive hypothesis is that the depth-fecundity relationships seen in O. faveolata may have to do with differential disturbance regimes across depths in the USVI. The relatively low disturbance and stress experienced by mesophotic coral reefs12,13,23,31,36 may allow corals entering reproductive phases to divert energy otherwise allocated for growth and colony maintenance. As a terrestrial corollary, some plants are capable of separating periods of growth from periods of fruiting when in stable, low variability environments in order to maximize reproductive potential, with ‘seed years’ in trees being a particularly good example37. It is possible that low disturbance and stress in USVI mesophotic environments—due to relatively consistent solar irradiation and temperature, low thermal bleaching incidence and reduced storm damage—results in the temporary cessation of growth and tissue maintenance and near-maximum gamete production during O. faveolata reproductive periods. Indeed, in 2010 shallow water Orbicella spp. in the USVI experienced a mean of 4.1 (±0.7 SEM, n = 8 sites) degree heating weeks and an elevated prevalence of stark white bleaching of 48.2% (±6.8, n = 10), whereas mesophotic corals experienced 0.1 (±0.1, n = 4) degree heating weeks and a non-elevated bleaching prevalence of 16.0% (±3.2, n = 4) (authors, unpub. data) which potentially contributed to the discrepancies observed in shallow and deep coral reproductive capacity in the following year. Nonetheless, measured fecundities close to published literature values in shallow colonies suggest that shallow water stress in 2010 could not explain all differences observed between depths.

A third explanation for higher fecundity in MCEs, which opposes the first two hypotheses, is that variation in habitat quality in mesophotic ecosystems increases adaptive pressure on reproductive synchrony, reproductive energy allocation and dispersal38. Contrary to the conventional understanding that physiological stress reduces reproductive output39, physiological stress encountered at the limits of a species’ range may in some instances induce increases in reproductive output7,10, suggesting the potential for adjustments in phenotypes. While many types of physiological stress and disturbance may be reduced in MCEs, the fact that the MCE orbicellids are at the maximum depth of their vertical range suggests a hard physiological barrier to survival, such as photosynthetic energy contribution at reduced light. Additionally, the delayed but rapid development of oocytes observed in mesophotic O. faveolata histological sections may imply that mesophotic colonies that have entered a reproductive phase divert a greater proportion of metabolic energy to reproduction than do shallow colonies. If this is the case, mesophotic O. faveolata may be particularly vulnerable to mortality from disease or physical damage during or directly after reproductive cycles due to energetic limitations akin to those experienced by corals after bleaching stress40,41.

Video collected in the field and laboratory in 2012 suggests synchronous spawning on the order of hours and days of O. faveolata at sites separated by ~11 km horizontally and ~30 m vertically. Mesophotic O. faveolata colonies spawned earlier (~1 hr) than shallow colonies when observed in the laboratory. Although laboratory conditions may skew spawning synchrony due to altered light cycles and separation from conspecifics, earlier spawning in deeper-living corals may also be due to truncated daylight hours at depth and an earlier sunset cue.

Histological analysis of gametogenesis and direct observations of O. faveolata spawning behavior support the assertion that spawning at shallow, mid-depth and mesophotic sites is synchronous within days, if not hours. It is unlikely that direct hybridization occurs between mesophotic and shallow O. faveolata colonies in the Northern USVI, despite the potential for synchronous gametogenesis and spawning behavior. Considerable horizontal distances separate the habitats in most cases and it is not likely that unfertilized gametes would meet. However, hybridization could be likely on wall or seamount habitats42, where buoyant or swimming gametes may have a greater potential of fertilization with conspecifics from a wide range of depths. The potential for deep and shallow hybridization in different habitat types warrants future investigation, and has implications for population connectivity and rates of coral adaptation, speciation and evolution.

Assuming equal habitat area, it appears that over 85% of Orbicella spp. (and O. faveolata specifically) ova in the USVI are produced below 20 m, and over 50% are produced between 30 m and 50 m, in MCEs. However, this likely underestimates mesophotic contributions in the USVI. A large MCE south of St. Thomas has been characterized13,14, where coral habitat extent is nearly half the total shallow coral reef extent in St. Thomas and St. John combined (mapped by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Center of Coastal Monitoring and Assessment). The true extent of MCEs in the USVI, and indeed in the Caribbean basin, is unknown, but there is potential that MCEs rival or surpass shallow reefs in habitat area43, which would imply even greater larval contributions from MCEs than suggested here.

In addition, the relative contribution of mesophotic larvae to regional larval pools could be increasing with shallow water reef degradation. Shallow reefs in the USVI and Puerto Rico experienced a nearly 10% absolute loss of coral cover between 1975 and 200044, and an additional relative 48%–61.8% loss in coral cover in shallow reefs after the 2005 bleaching and disease event40,45. The impacts on shallow water coral cover were greatest in Orbicella spp.45. USVI MCEs and mesophotic orbicellids appear to have been spared this fate14, and growing disparity in coral cover between shallow and mesophotic coral reefs suggests that the proportion of all coral reef larvae produced in MCEs will continue to grow.

Fertilization—a crucial step in the reproductive cycle—was not addressed in this study. The physical conditions of deep and shallow environments may create disparate fertilization conditions for corals in a number of ways, the most obvious being for broadcast spawning species such as O. faveolata. Traditionally it is understood that O. faveolata gamete bundles rise to the air-sea boundary where fertilization occurs after they are concentrated and break apart. Depth, therefore, may limit fertilization success in this species, as gamete bundles may break apart, disperse or be preyed upon before they reach the sea surface. Understanding the effects of depth on fertilization rates of corals is important for accurately estimating larval load, and will be the focus of future research.

Similarly, larval survivorship and post-settlement mortality have implications for the refugia potential of MCEs. For example, Agaricia agaricites larvae taken from different depths show differential survivorship when exposed to UVB radiation46. Larvae of mesophotic origin may have different rates of pelagic and post-settlement mortality as compared to larvae from shallower habitats, which must be quantified if we hope to understand how MCEs contribute to coral reef resilience through larval exchange. Studies suggest that both coral and endosymbiont genetic connectivity vary by location and by species, and in some species speciation may be occurring across depth47,48,49,50; thus, refugia habitat will likely require a suite of overlapping protective characteristics as well as larval exchange with adjacent habitats.

The dispersal of orbicellid larvae between MCEs and shallower habitats was not addressed in this study, however study of Montastraea cavernosa—another broadcasting species—in the USVI has suggested that genetic mixing across depth may occur50, and biophysical modeling suggests that vertical migration of orbicellid larvae between coral reefs in the USVI is possible51. In order for MCEs to behave as functional refugia and contribute to coral reef resilience, they must contribute to the demography of coral reefs in general, and more study of how these systems interact and exchange larvae with adjacent habitats is necessary. As shallow coral habitats continue to be degraded and fragmented, MCEs may prove to be more and more important as potential sources of coral reef larvae, and it is crucial that these habitats be given adequate conservation attention despite being located at the limits of many species ranges. Continued evaluation of the potential for mesophotic reproductive refugia to provide coral reef larvae to both shallow and mesophotic environments will aid in discerning the complex roles these marginal—but not negligible—coral reefs have played, do play and will play in Caribbean coral reef metapopulations.

Methods

To test our hypotheses we selected shallow, mid-depth and MCE coral reefs off the south side of St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands (USVI) in 2011 and 2012 (Fig. 1). This is an ideal area to study questions concerning the DRRH because the broad insular shelf and shelf edge support extensive MCEs. MCEs of the northern USVI between depths of 30–45 m are predominantly composed (>85% by cover) of members of Orbicella spp.14, the principal shallow and mid-depth structural reef-building scleractinian corals in the Caribbean52. We chose the species O. faveolata to test hypotheses concerning the reproductive potential of MCEs. This species is ideal because O. faveolata is a depth-generalist that can be abundant in shallow habitats and has been shown to be extremely abundant in MCEs in the USVI14. Its threatened status29 also allows for inferences regarding deep refugia.

O. faveolata is simultaneously hermaphroditic, with each polyp producing egg and sperm concurrently. Each colony typically spawns once a year, about one week after full moon in either August or September, and in some areas as late as October. Spawning usually lasts for under an hour, and during spawning egg and sperm bundles are extruded from the oral cavity of the polyp and float to the ocean surface where eventually they break apart and potentially cross-fertilize32,33,53.

Sample collection

Preliminary sampling occurred in August 2010 to determine if mesophotic O. faveolata populations were gravid when expected. 70–80% of colonies sampled were reproductively active (i.e. contained gametes) at all sites from 6–39 m depth, just prior to expected spawning dates (See Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Supplementary Table S1). In July and August 2011, O. faveolata colonies were randomly sampled at three sites over five weeks (n ≥ 5 site−1 week−1, N = 77). The three sites included a shallow inshore site (Black Point, 5–8 m), a mid-depth off-shore island site (Flat Cay, 16–21 m), and a mesophotic site (Grammanik Bank, 37–40 m) (Fig. 1). All tissues were fixed in zinc-buffered formalin (Z-Fix) for 24 hours, rinsed in fresh water for 24 hours, and stored in 70% EtOH until processing. The surface area of each sampled coral colony was estimated to ensure that depth-fecundity relationships were not confounded by fecundity-size relationships (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Supplementary Fig. S4).

In 2012 partial colonies of O. faveolata were collected several days before predicted spawning in both August and September from a mesophotic site (35–40 m, n = 10) and a shallow site (5–10 m, n = 10) for laboratory observation. These samples were kept in temperature-controlled (27 °C+/−1 °C) flow-through seawater tables and were exposed to near-natural light cycles. In the evenings throughout the potential spawning window, these partial colonies were observed for spawning behavior in isolated glass jars. Additionally, video systems were deployed in August and September 6–9 days after full moon to capture video of in situ spawning behavior in an MCE. Video systems were built using two GoPro HD (http://www.gopro.com) cameras and external lights mounted on a weighted plastic frame. The system was deployed from a boat using a Sea Viewer drop camera to guide the placement on top of an O. faveolata colony. The drop camera was subsequently pulled free and the system was allowed to record through the potential spawning window on a given night.

Histological preparations

Samples were decalcified using 10% HCl solution and 0.5 g/L EDTA. This solution was replaced every 24 hours until all calcium carbonate had been dissolved, after which tissue was stored in 70% EtOH. A tissue processor (Sakura Tissue-Tek II) was used to dehydrate and parafinize tissues. Parafinized tissue was arranged for cross and longitudinal sectioning and embedded in paraffin blocks using a tissue embedding station (Sakura Tissue-Tek TEC). Blocks were then sectioned on a Leica RM2235 microtome with 4 micron thickness at five depths, beginning just below the oral opening, with subsequent sections occurring every 100 microns. Sections were arranged on microscope slides stained using a modified Heidenhain’s aniline blue stain.

Reproductive characteristics

O. faveolata histological sections were analyzed for (1) presence/absence of male and female gonads and gametes of each reproductive stage30 (complementary staging techniques are also becoming more commonly used54); (2) the fecundity, or number of oocytes or ova per gonad, and the number of gonads per polyp27,33,55; as well as (3) the diameter and condition of oocytes. Observations were made using both standard light microscopy and an Olympus VS120-S5 digital slide scanner. Measurements were made using Fiji software (ImageJ).

The number of polyps per surface area was estimated for a subsample of colonies in order to account for increased polyp spacing with depth56,57. A white light 3D scanner (3D3 Solutions HDI Advance) was used to digitize samples in high resolution. Polyps were enumerated on the scans in Leios 3D data processing software. Those digital surfaces were smoothed to find a basal surface area (Supplementary Fig. S5).

O. faveolata fecundity per cm2 (F) was estimated as the product of:

F = (eggs * gonad−1) * (gonads * polyp−1) * (polyps * cm−2)

In order to derive depth-specific unit reef egg production, estimates of percent coral cover were calculated from diver video transects performed at each site from 2001–201258. Orbicella spp. coral cover was used as a proxy for O. faveolata coral cover since it is often difficult to distinguish Orbicella species from video at mesophotic depths. It is expected that O. faveolata cover trends with total Orbicella species cover in this area. This data was plotted against depth (square root-transformed) and a third-order polynomial model was fitted to the result. The products of equation 1 were then multiplied by estimated coral cover at each depth to approximate the number of eggs per 1 km2 unit reef as a function of depth.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Holstein, D. M. et al. Fertile fathoms: Deep reproductive refugia for threatened shallow corals. Sci. Rep. 5, 12407; doi: 10.1038/srep12407 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by the US National Science Foundation-Virgin Islands Experimental Program to stimulate Competitive Research (to TBS, CBP, DMH and JG) and the Black Coral Penalty Fund (TBS). Further support was provided through the Natural Environmental Research Council and EU FORCE project and the National Science Foundation OCE-0928423 (to CBP). V. Brandtneris contributed to field operations, and A. Moulding and D.A. Renegar provided expertise in coral histology. D. Manzello and I. Enochs provided access to the 3D3 Solutions HDI Advance 3D scanner. P. Ruiz and S. Philip provided access to the Olympus VS120-S5 digital slide scanner. The research herein reflects the views of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.M.H., C.B.P. and T.B.S. designed the study; D.M.H. conducted the analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; D.M.H., T.B.S. and J.G. collected data; all authors contributed substantially to revisions.

References

- Gaston K. J. The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges . (Oxford University Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Sexton J. P., McIntyre P. J., Angert A. L. & Rice K. J. Evolution and Ecology of Species Range Limits. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40, 415–436 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. J., Jenkinson L. S., Lawton J. H., Shorrocks B. & Wood S. Making mistakes when predicting shifts in species range in response to global warming. Nature 391, 783–787 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. H. On the Relationship between Abundance and Distribution of Species. Am. Nat. 124, 255–279 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S. A test of Brown’s principle in the intertidal limpet Collisella scabra (Gould, 1846). J. Biogeogr. 32, 1583–1589 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Sagarin R. D. & Gaines S. D. The ‘abundant centre’ distribution: to what extent is it a biogeographical rule? Ecol. Lett. 5, 137–147 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Lester S. E., Gaines S. D. & Kinlan B. P. Reproduction on the edge: large-scale patterns of individual performance in a marine invertebrate. Ecology 88, 2229–39 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horne B. Density as a misleading indicator of habitat quality. J. Wildl. Manage. 47, 893–901 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Botsford L. Physical influences on recruitment to California Current invertebrate populations on multiple scales. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 58, 1081–1091 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Milla R., Giménez-Benavides L., Escudero A. & Reich P. B. Intra- and interspecific performance in growth and reproduction increase with altitude: a case study with two Saxifraga species from northern Spain. Funct. Ecol. 23, 111–118 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R. et al. Characterizing the deep insular shelf coral reef habitat of the Hind Bank marine conservation district (US Virgin Islands) using the Seabed autonomous underwater vehicle. Cont. Shelf Res. 26, 194–205 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Menza C., Kendall M. & Hile S. The deeper we go the less we know. Rev. Biol. Trop. 56, 11–24 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. B. et al. Assessing coral reef health across onshore to offshore stress gradients in the US Virgin Islands. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 56, 1983–91 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. B. et al. Benthic structure and cryptic mortality in a Caribbean mesophotic coral reef bank system, the Hind Bank Marine Conservation District, U.S. Virgin Islands. Coral Reefs 29, 289–308 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Leichter J. & Genovese S. Intermittent upwelling and subsidized growth of the scleractinian coral Madracis mirabilis on the deep fore-reef slope of Discovery Bay, Jamaica. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 316, 95–103 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi J. M., Connolly S. R., Marshall D. J. & Cohen A. L. Projecting coral reef futures under global warming and ocean acidification. Science 333, 418–22 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T. P., Graham N. a J., Jackson J. B. C., Mumby P. J. & Steneck R. S. Rising to the challenge of sustaining coral reef resilience. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Personal Ed. 25, 633–642 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012. (Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, IUCN, 2014).

- Glynn P. W. Coral reef bleaching: facts, hypotheses and implications. Glob. Chang. Biol. 1, 177–509 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Riegl B. & Piller W. E. Possible refugia for reefs in times of environmental stress. Int. J. Earth Sci. 92, 520–531 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- West J. M. & Salm R. V. Resistance and Resilience to Coral Bleaching: Implications for Coral Reef Conservation and Management. Conserv. Biol. 17, 956–967 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts P., Ridgway T., Sampayo E. M. & Hoegh-Guldberg O. Assessing the ‘deep reef refugia’ hypothesis: focus on Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs 29, 309–327 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Lesser M. P., Slattery M. & Leichter J. J. Ecology of mesophotic coral reefs. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 375, 1–8 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Kojis B. L. & Quinn N. J. Season and depth variation in fecundity of Acropora palifera at two reefs in Papua New Guinea. Coral Reefs 3, 165–172 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Rinkevich B. & Loya Y. Variability in the pattern of sexual reproduction of the coral Stylophora pistillata at Eilat, Red Sea: A long-term study. Biol. Bull. 173, 335–344 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Richmond R. H. Energetic relationships and biogeographical differences among fecundity, growth and reproduction in the reef coral Pocillopora damicornis. Bull. Mar. Sci. 41, 594–604 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Villinski J. T. Depth-independent reproductive characteristics for the Caribbean reef-building coral Montastraea faveolata. Mar. Biol. 142, 1043–1053 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Lesser M. P. et al. Photoacclimatization by the coral Montastraea cavernosa in the mesophotic zone: light, food, and genetics. Ecology 91, 990–1003 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOAA. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Final Listing Determinations on Proposal to List 66 Reef-building Coral Species and to Reclassify Elkhorn and Staghorn Corals (2014).

- Szmant A. M. Sexual reproduction of Favia fragum (Esper): Lunar patterns of Gametogenesis, embryogenesis and planularion in Puerto Rico. Bull. Mar. Sci. 37, 880–892 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Slattery M., Lesser M. P., Brazeau D., Stokes M. D. & Leichter J. J. Connectivity and stability of mesophotic coral reefs. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 408, 32–41 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Szmant A. M., Weil E., Miller M. W. & Colon D. E. Hybridization within the species complex of the scleractinan coral Montastraea annularis. Mar. Biol. 129, 561–572 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Szmant A. A. M. Sexual reproduction by the Caribbean reef corals Montastrea annularis and M. cavernosa. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 74, 13–25 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Van Veghel M. L. J. & Kahmann M. E. H. Reproductive characteristics of the polymorphic Caribbean reef building coral Montastrea annularis. II. Fecundity and colony structure. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 109, 221–227 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Grottoli A. G. et al. The cumulative impact of annual coral bleaching can turn some coral species winners into losers. Glob. Chang. Biol. (2014). 10.1111/gcb.12658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak R., Nieuwland G. & Meesters E. Coral reef crisis in deep and shallow reefs: 30 years of constancy and change in reefs of Curacao and Bonaire. Coral reefs 24, 475–479 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Wolgast L. J. & Zeide B. Reproduction of Trees in a Variable Environment. Bot. Gaz. 144, 260–262 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Darling E., Samis K. E. & Eckert C. G. Increased seed dispersal potential towards geographic range limits in a Pacific coast dune plant. New Phytol. 178, 424–35 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend C. R., Harper J. L. & Begon M. Essentials of ecology. (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. et al. Coral disease following massive bleaching in 2005 causes 60% decline in coral cover on reefs in the US Virgin Islands. Coral Reefs 28, 925–937 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill D. J. et al. A connection between colony biomass and death in Caribbean reef-building corals. PLoS One 6, e29535 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vize P. D. Deepwater broadcast spawning by Montastraea cavernosa, Montastraea franksi, and Diploria strigosa at the Flower Garden Banks, Gulf of Mexico. Coral Reefs 25, 169–171 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Locker S. D. et al. Geomorphology of mesophotic coral ecosystems: current perspectives on morphology, distribution, and mapping strategies. Coral Reefs 29, 329–345 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Gardner T. a, Côté I. M., Gill J. a, Grant A. & Watkinson A. R. Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science (80−.) 301, 958–60 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. B. et al. Convergent mortality responses of Caribbean coral species to seawater warming. Ecosphere 4, art87 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Gleason D. F. & Wellington G. M. Variation in UVB sensitivity of planula larvae of the coral Agaricia agaricites along a depth gradient. Mar. Biol. 123, 693–703 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts P. et al. Deep down on a Caribbean reef: lower mesophotic depths harbor a specialized coral-endosymbiont community. Sci. Rep. 5, 7652 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts P. et al. Genetic divergence across habitats in the widespread coral Seriatopora hystrix and its associated Symbiodinium. PLoS One 5, e10871 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prada C. & Hellberg M. E. Long prereproductive selection and divergence by depth in a Caribbean candelabrum coral. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano X. et al. Geographic differences in vertical connectivity in the Caribbean coral Montastraea cavernosa despite high levels of horizontal connectivity at shallow depths. Mol. Ecol. 23, 4226–40 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein D. M. Vertical Connectivity in Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems. (University of Miami, 2013).

- Goreau T. F. The Ecology of Jamaican Coral Reefs I. Species Composition and Zonation. Ecology 40, 67–90 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- Szmant A. Reproductive ecology of Caribbean reef corals. Coral Reefs 5, 43–54 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Baird a. H., Blakeway D. R., Hurley T. J. & Stoddart J. a. Seasonality of coral reproduction in the Dampier Archipelago, northern Western Australia. Mar. Biol. 158, 275–285 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Van Veghel M. L. J. Reproductive characteristics of the polymorphic Caribbean reef building coral Montastrea annularis. I. Gametogenesis and spawning behavior. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 109, 209–219 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Dustan P. Distribution of zooxanthellae and photosynthetic chloroplast pigments of the reef-building coral Montastrea annularis Ellis and Solander in relation to depth on a West Indian coral reef. Bull. Mar. Sci. 29, 79–95 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Graus R. R. & Macintyre I. G. Variation in Growth Forms of the Reef Coral Montastrea annularis (Ellis and Solander): A Quantitative Evaluation of Growth Response to Light Distribution Using Computer Simulation. Smithson. Contrib. to Mar. Sci. 12, 441–464 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. B. et al. The United States Virgin Islands Territorial Coral Reef Monitoring Program. 2011 Annual Report (2011).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.