Abstract

Dental mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a reliable and promising cell source for the regeneration of tooth,bone and other tissues . However, the molecular mechanisms underlying their differentiation are still largely unknown, which restricts their further wide application. Here, we investigate regulatory function of homeobox gene MEIS2 in the osteogenic differentiation potential of MSCs using stem cells from apical papilla (SCAPs) and dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) by loss-of-function experiments. Our findings demonstrated that knockdown of MEIS2 in SCAPs and DPSCs decreased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and mineralization, and inhibited the mRNA expression of ALP, bone sialoprotein (BSP), and osteocalcin (OCN). Besides, depletion of MEIS2 resulted in reduced expression of the key osteogenesis-related transcription factor, osterix (OSX) but not in the expression of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2). Furthermore, MEIS2 expression significantly increased during osteogenic induction and was strongly upregulated by BMP4 stimulation. Taken together, these results indicated that MEIS2 played an essential role in maintaining osteogenic differentiation potential of dental tissue- derived MSCs. These findings will provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying directed differentiation of MSCs, and identify a potential target gene in dental tissues derived MSCs for promoting the tissue regeneration.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cell, osteogenic differentiation, MEIS2, homeobox gene, tooth

Introduction

The discovery of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), originally isolated from bone marrow, was a giant breakthrough in medicine and opened a new door for alternative therapies of various diseases for their potencies of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation. The successful isolation and identification of stem cells from the dental tissues, such as DPSCs [1], stem cells from exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs) [2], periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) [3], dental follicle progenitor cells (DFPCs) [4] and SCAPs [5], has proven diverse populations of MSCs that exist in non-bone marrow tissues. Dental MSCs are not only easily accessible, but also possessing osteo/dentinogenic differentiation potentials as bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. When delivered in vivo, dental MSCs could generate bone/dentin-like mineralized tissues and be capable of repairing bone or tooth defects [6,7]. These make them promising and powerful candidates for therapy including bone and tooth regeneration. However, the mechanisms in osteo/dentinogenic differentiation of dental MSCs remain elusive, which has largely restricted their further potential application.

Homeobox genes, originally identified in drosophila but rapidly found in all animal species as well as in fungi and plants, are homologous genes highly conserved during evolution across lineages. Homeobox genes are characterized by a conserved 180 bp DNA sequence coding for a 60aa DNA-binding homeodomain. Homeodomain proteins are transcription factors that can activate or inhibit transcription of downstream genes through the DNA binding. Recent studies show that homeobox genes play crucially regulatory roles in the process of maxillofacial and dental development. It’s reported that prior to tooth development, homeobox genes had been expressed in the mesenchyme of the first branchial arch, and were subsequently expressed in different stages during odontogenesis, involving in both temporal and spatial control of dentition formation [8-10]. Distal-less homeobox5 (DLX5) was found as a requisite for mineralization of tooth. In Dlx5-/-mice, both maxillary and mandibular molars were malformed and had poorly mineralized crowns and both sets of incisors were shortened and misshapen [11]. In Pbx1-deficient mice, absence of pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox proteins 1 (Pbx1) caused precocious endochondral ossification and abnormal bone formation by perturbing chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation [12]. Homeobox a10 (Hoxa10) could mediate chromatin hyperacetylation and trimethyl histone K4 (H3K4) methylation, induce expression of osteogenic genes through activation of Runx2, or directly regulate other osteoblastic phenotypic genes, and contribute to the onset of osteogenesis and subsequent bone formation [13]. More importantly, it has been reported that homeobox gene msh-like 1 (Msx1) is essential for the proliferation and differentiation of dental mesenchymal cells at cap stage. Knockdown of Msx1 resulted in decreased cell proliferation but enhanced odontoblast differentiation [14]. The DLX2 gene is highly expressed in dental tissue-derived MSCs. It’s reported that DLX2 promotes the osteogenic differentiation potential of stem cells from apical papilla while knock-down of DLX2 in SCAPs decreased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and mineralization [15]. Homeodomain protein HOXA10 and TALE-family protein PBX1 form coregulatory complexes. They are expressed in osteoprogenitors and mediated regulation of osteoblast commitment and the related gene expression. Overexpression of HOXA10 increased the expression of osteoblast-related genes, osteoblast differentiation and mineralization; expression of PBX1 impaired osteogenic commitment of pluripotent cells and the differentiation of osteoblasts. It’s proposed that PBX1 probably attenuated the activity of HOXA10 as an activator of osteoblast-related genes, which functioned to establish the proper timing of gene expression during osteogenesis and resulted in proper matrix maturation and mineral deposition in differentiated osteoblasts [16]. Other recent studies also have showed that homeobox gene DLX5 and HOXC6 function as key regulators in the lineage commitment of MSCs into osteoblasts [15,17,18], indicating that homeobox genes play essential roles in the development of hard tissue and the odonto/osteogenic differentiation of stem cells.

Myeloid ecotropic insertion site 2 (MEIS2), also known as MRG1, is a homeobox gene belonging to the three amino-acid loop extension (TALE) superclass. It contains a conserved homothorax (Hth) domain, which mediates interaction with PBX and allows for efficient DNA binding [19]. As an evolutionary conserved transcription factor, MEIS2 has been shown to participate in some developmental processes during embryogenesis, including development of proximal-distal limb patterning [20], heart [21], brain [22-24] and so on. For instance, MEIS2 is the only known transcriptional regulator so far that is capable to direct tectal fate specification and whose expression specifically marks the tectal anlage at mid to late somite stages [25]. MEIS2 is also showed to play an essential role in maintaining proliferation and regulating fate specification of retinal progenitor cells in chick and mouse embryos [26]. However, at present, functional role of MEIS2 in differentiation of MSCs, especially, the ddental tissue- derived MSCs, hasn’t been reported. Here, by loss-of-function study, we used SCAPs and DPSCs to investigate the function of MEIS2 in osteogenic differentiation potential of MSCs. Our results showed that depletion of MEIS2 inhibited the osteogenic differentiation potential in SCAPs and DPSCs, indicated that MEIS2 played an essential role in maintaining osteogenic differentiation potential of dental tissue- derived MSCs.

Material and methods

Cell cultures and viral infection

Human tooth tissues from impact third molars were obtained under approved guidelines set by the Beijing Stomatological Hospital, Capital Medical University with informed patient consent. The isolation, culture and identification of SCAPs and DPSCs were performed as previously reported [27,28]. Briefly, the third molars were first disinfected with 75% ethanol and then washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). SCAPs were gently separated from the apical papilla of the root, while DPSCs were separated from crown pulp. MSCs then respectively digested in a solution of 3 mg/ml collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ, USA) and 4 mg/ml Dispase (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 1 hour at 37°C. Single-cell suspensions were obtained by passing the cells through a 70 μm strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Then they were grown in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C in DMEM alpha modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 2 mmol/l glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The culture medium was changed every 3 days. Cells at passage 3-5 were used in subsequent experiments.

Plasmid construction and viral infection

The plasmids were constructed with standard methods; all structures were verified by appropriate restriction digest and/or sequencing. Short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) with the complementary sequences of the target genes were subcloned into the the pSIREN retroviral vector (Clontech Labtoratories, Mountain View, CA, USA) or pLKO.1 lentiviral vector (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA). Viral packaging was prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol using 293T cells (BD Clontech). For viral infections, MSCs were plated overnight, and then infected with lentiviruses or retroviruses in the presence of polybrene (6 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 6 h. After 48 h, infected cells were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A Luciferase shRNA (Lucsh) was used as control. The target sequences for the shRNAs were: Luciferase shRNA, 5’-gtgcgttgctagtaccaac-3’; MEIS2 shRNA1, 5’-ggaaccacactggagatca-3’; MEIS2 shRNA2, 5’-gcttctgccaccgatacat-3’; sterile alpha motif domain containing 4 (SMAD4) shRNA (SMAD4sh), 5’-cattggatgggaggcttca-3’; A scramble shRNA (Scramsh) was purchased from Addgene.

Alkaline phosphatase and alizarin red detection

Cells were grown in osteogenic-inducing medium using the STEMPRO Osteogenesis Differentiation Kit (Invitrogen). ALP activity was assayed with an ALP activity kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma-Aldrich). Signals were normalized based on protein concentrations. For detecting mineralization, cells were induced for 3 weeks, fixed with 70% ethanol, and stained with 2% Alizarin red (Sigma-Aldrich). To quantitatively determine calcium, Alizarin Red was destained with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride in 10 mM sodium phosphate for 30 minutes at room temperature. The concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 562 nm on a microplate reader and comparing to a standard calcium curve with calcium dilutions in the same solution. The final calcium level in each group was normalized to the total protein concentration detected in a duplicate plate [27].

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from SCAP cells with Trizol reagents (Invitrogen). We synthesized cDNA from 2 μg aliquots of RNA, random hexamers or oligo (dT), and reverse transcriptase, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR reactions were performed with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and an IcycleriQ Multi-color Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The expression of genes was calculated by the method of 2-ΔΔCT as described previously [29]. The primers for specific genes were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in the Real-time RT-PCR

| Gene Symbol | Primer Sequences (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| GAPDH-F | CGGACCAATACGACCAAATCCG |

| GAPDH-R | AGCCACATCGCTCAGACACC |

| MEIS2-F | cggatGCCTAGATCACTTTCTTATCcG |

| MEIS2-R | TCTGCGCTCCAATAAACTCCTGGCT |

| BSP-F | CAGGCCACGATATTATCTTTACA |

| BSP-R | CTCCTCTTCTTCCTCCTCCTC |

| OSX-F | CCTCCTCAGCTCACCTTCTC |

| OSX-R | GTTGGGAGCCCAAATAGAAA |

| ALP-F | GACCTCCTCGGAAGACACTC |

| ALP-R | TGAAGGGCTTCTTGTCTGTG |

| OCN-F | Agcaaaggtgcagcctttgt |

| OCN-R | gcgcctgggtctcttcact |

| SMAD4-F | GGTTGCACATAGGCAAAGGT |

| SMAD4-R | TGACCCAAACATCACCTTCA |

Statistics

All statistical calculations were performed with SPSS13.0 statistical software. The student’s t test or Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test were performed to determine statistical significance. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Depletion of MEIS2 inhibited osteogenic differentiation potential in SCAPs

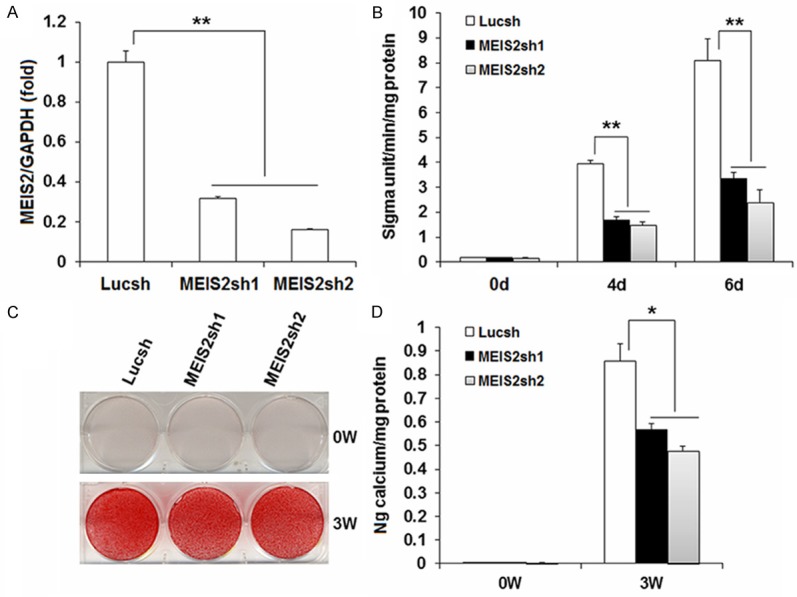

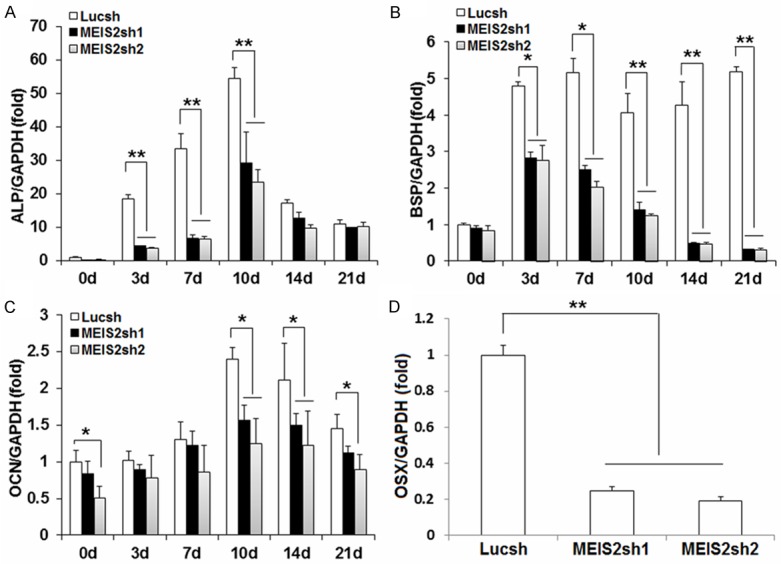

In order to investigate the function of MEIS2 in SCAPs, we designed two short hairpin RNAs to target MEIS2 and introduced them into SCAPs with retroviral infection (MEIS2sh1 and MEIS2sh2, respectively). After selection, the knockdown efficiency (70% in MEIS2sh1 and 85% in MEIS2sh2) was verified by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 1A). Next, we examined whether MEIS2 intrinsically affected the osteogenic differentiation potential of SCAPs. Transduced SCAPs were cultured in osteogenic-inducing medium, examined ALP activity on 0, 4, 6 days, stained Alizarin Red and detected calcium in 0 and 3 weeks. The results indicated that the depletion of MEIS2 markedly reduced ALP activity, an early marker for osteogenic differentiation in SCAPs (Figure 1B), and significantly deceased mineralization determined by Alizarin Red staining and quantitative calcium measurements (Figure 1C, 1D). Consistent with that, real-time RT-PCR results showed that the osteogenic marker gene ALP was strongly reduced when MEIS2 were knocked down on 3, 7, 10 days after induction (Figure 2A). Other osteogenic marker genes, BSP and OCN, which encode extracellular matrix proteins of bone, were also significantly reduced after induction (Figure 2B, 2C). On the third day BSP was decreased by about 40% while on the 21th day it dropped by approximately 90% after induction. Changes of OCN after induction took place earlier but slightly than BSP. At the beginning day of induction, OCN quickly declined by 20% in MEIS2sh1 and 50% in MEIS2sh2 and on the day 21, it reduced by 26% in MEIS2sh1 and 40% in MEIS2sh2. Next, we examined the expression of OSX and RUNX2 which are important key transcription factors for regulating osteogenic differentiation. It found that the mRNA level of OSX was decreased by about 80% when MEIS2 were knocked down (Figure 2D). However, the mRNA level of RUNX2 was not obviously changed (data not show). Notably, inhibition of MEIS2sh to osteogenic differentiation of SCAPs seemed dose-dependent because almost all the osteogenic differentiation markers described above were decreased more in the MEIS2sh2 group than those in the MEIS2sh1 group.

Figure 1.

Knockdown of MEIS2 inhibited osteogenic potential in SCAPs. SCAPs were infected with short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) that silenced MEIS2 with different knockdown efficiency or Luciferase shRNA (Lucsh). Real-time RT-PCR showed MEIS2 expression (30% left in MEIS2sh1 and 15% left in MEIS2sh2). GAPDH was used as an internal control (A). The knock-down of MEIS2 reduced alkaline phosphatase activity (B), Alizarin red staining (C) and calcium quantitative analysis (D) in SCAPs. Analysis of variance was performed to determine statistical significance. All error bars represent s.d. (n=3). *P ≤ 0.05. **P ≤ 0.01.

Figure 2.

Knockdown of MEIS2 reduced the expression of osteogenic related genes in SCAPs. Real-time RT-PCR results showed depletion of MEIS2 reduced the expression of ALP (A), BSP (B), OCN (C), and OSX (D). GAPDH was used as an internal control. Analysis of variance was performed to determine statistical significance. All error bars represent s.d. (n=3). *P ≤ 0.05. **P ≤ 0.01.

BMP signaling induced MEIS2 expression

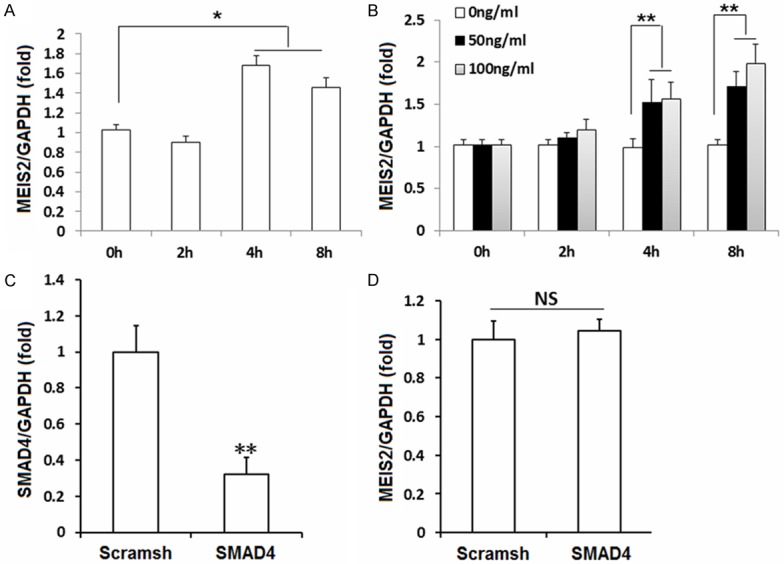

To explore the possible mechanisms of MEIS2 in osteogenic differentiation potential in SCAPs, we first examined the expression of MEIS2 in SCAPs during osteogenisis process and found that MEIS2 was significantly up-regulated (more than 1.6 times) in SCAPs when cultured with osteogenic-inducing medium (Figure 3A). We further loaded three different concentrations of BMP4 (0, 50, 100 ng/ml) in basic culture medium. We found that MEIS2 was strongly induced in SCAPs after BMP4 treatment (Figure 3B). For example, at the eighth hour, expression of MEIS2 was increased by 1.7 times in medium with 50 ng/ml BMP4 and increased by 1.9 times in medium with 100 ng/ml BMP4. Last, we examined the effects of SMAD4 on MEIS2 expression. It’s demonstrated that knockdown of SMAD4 had no obvious effect on MEIS2 transcription (Figure 3C, 3D). Taken together, these findings suggested that MEIS2 act as a downstream DNA-binding protein in BMP signaling cascade but its transcriptional activity may be independent of the regulation of SMAD4.

Figure 3.

BMP signaling induced MEIS2 expression. MEIS2 was significantly up-regulated in SCAPs when cultured with osteogenic-inducing medium (A). MEIS2 was strongly induced in SCAPs immediately after treated with different concentrations of BMP4 (0, 50, 100 ng/ml respectively.) in basic culture medium (B). Real-time RT-PCR results showed that knockdown of SMAD4 had no obvious effect on MEIS2 expression (C, D). GAPDH was used as an internal control. Analysis of variance (A, B) or student’s t test (C, D) was performed to determine statistical significance. All error bars represent s.d. (n=3). *P ≤ 0.05. **P ≤ 0.01.

Depletion of MEIS2 inhibited osteogenic differentiation potential in DPSCs

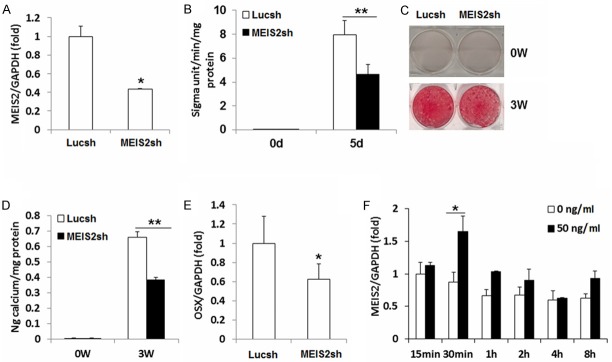

To confirm that MEIS2 is indeed crucial in maintaining osteogenic differentiation potential of dental tissue- derived MSCs, we further depleted MEIS2 in DPSCs and investigated the changes of their osteogenic differentiation potential. Similar effects with those in SCAPs were observed in DPSCs. Transduced DPSCs with 60% knockdown efficiency (Figure 4A) had a decreased ALP activity (Figure 4B), mineralization also determined by Alizarin Red staining (Figure 4C) and quantitative calcium measurements (Figure 4D), compared to the control group (Lucsh). Besides, the expression of the key transcription factor, OSX, was down-regulated by 40% when MEIS2 depleted (Figure 4E). MEIS2 was also significantly induced in DPSCs immediately following BMP4 (50 ng/ml) loaded in basic culture medium (Figure 4F). Collectively, these observations further confirmed our hypothesis that MEIS2 was important in maintaining osteogenic differentiation potential of dental tissue derived MSCs.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of MEIS2 inhibited osteogenic potential in DPSCs. DPSCs were infected with short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) that silenced MEIS2 (MEIS2sh) or Luciferse shRNA (Lucsh). Real-time RT-PCR showed MEIS2 expression. GAPDH was used as an internal control (A). The knock-down of MEIS2 reduced alkaline phosphatase activity (B), Alizarin red staining (C) and calcium quantitative analysis (D) in DPSCs. Real-time RT-PCR showed decreased OSX expression after depletion of MEIS2 in DPSCs. GAPDH was used as an internal control (E). Real-time RT-PCR showed MEIS2 was strongly induced in DPSCs immediately after loading BMP4 (50 ng/ml) in basic culture medium (F). Student’s t test was performed to determine statistical significance. All error bars represent s.d. (n=3). *P ≤ 0.05. **P ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

MEIS2 is a critical member of homeobox genes and plays a key role in regulating cell fate. Evidence for the potential function of MEIS2 in controlling differentiation of stem cells involved in its critical roles in regulating the differentiation of embryonic stem cells into the cardiac, brain, and retinal cell lineage. Here, we present evidence to extend the functions of homeobox gene MEIS2 to be a critical regulator in maintaining osteogenic differentiation of postnatal MSCs in vitro.

The commitment of MSCs into osteogenic lineages requires activation of multiple transcription factors [30,31]. Runx2 and Osx are two of the key transcription factors necessary for the osteogenic differentiation [32-34]. Genetic and molecular studies have shown that Runx2 functions as an early transcriptional regulator of osteogenesis directing the differentiation of MSCs into an osteoblastic lineage [35]. After differentiating into preosteoblasts, Runx2 and Osx can drive them into immature osteoblasts and produce bone matrix. Then, Runx2 inhibits maturation of osteoblast and transition into osteocytes [34]. As a downstream gene of Runx2, Osx is anther transcription factor, which is essential at the early and late stages of osteogenesis [36-38] and, specifically expressed in all developing bones [39]. In the process of osteogenesis, ALP, OCN, BSP are the distinctive and key proteins of bone extracellular matrix. ALP is an enzyme mainly participating in hydrolysis of pyrophosphate during the early and late stage of osteogenesis. The activity of ALP indicates the extent of differentiation of preosteoblasts into osteoblasts; therefore, it’s identified as an early marker of osteogenesis. OCN and BSP are both important markers in the later stage of osteogenic differentiation, suggesting mature of osteoblasts.

In the present study, by loss-of-function experiment, we found that targeted depletion of MEIS2 by short hairpin RNA markedly reduced ALP activity in a dose-dependent manner in SCAPs, consistent with the following Alizarin Red staining and quantitative calcium measurements. These results indicated that MEIS2 was important in maintaining normal osteogenic differentiation of dental MSCs. Next, by real-time RT-PCR, we identified the important osteogenic marker genes and found that loss of MEIS2 largely decreased ALP, BSP and OCN, which encode extracellular matrix proteins during osteogenesis. We further examined the expressions of OSX and RUNX2, which are the important key transcription factors for regulating osteogenic differentiation. It revealed that depletion of MEIS2 evoked the significant down-regulation of OSX, but didn’t affect RUNX2 expression, indicating that regulation of MEIS2 on osteogenesis didn’t mediate by RUNX2, but by its downstream transcription factor OSX. MEIS2 evoked the activity of OSX, driving the preosteoblasts into osteoblasts and producing bone matrix like ALP, BSP and OCN. In parallel, results of additional experiments from DPSCs were consistent with those from SCAPs, further confirming our supposition that MEIS2 was a critical factor for osteogenic differentiation potential of MSCs.

The process that commitment of mesenchymal stem cells to osteoblast lineages in vivo is usually mediated by a variety of extracellular signals, including canonical WNT signals and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) [31,40,41]. Homeodomain proteins have been identified as downstream targets or regulators of osteogenic BMP signaling [42-44]. Therefore, we further investigated the effects of BMP4 on the expression of MEIS2 in SCAPs and DPSCs. We found that MEIS2 was strongly stimulated immediately following BMP4 treatment, indicating that MEIS2 enhancing the osteogenic differentiation of SCAPs and DPSCs may be mediated by BMP signaling. With similar mechanism, Hoxa10 played a vital role in regulating formation and maintenance of bone tissues [45,46]. Previous study showed that Hoxa10 was markedly stimulated in osteoblasts after BMP2 treatment, coincident with the robust expression of Runx2 [47]. However, in our findings, it was with no change in the expression of RUNX2, probably because that osteogenic differentiation of SCAPs and DPSCs mediated by MEIS2 is independent of RUNX2. Furthermore, we examined the effects of SMAD4, a key mediator of BMP canonical signaling pathway, on MEIS2 expression and found that knockdown of SMAD4 didn’t result in decrease of MEIS2 transcription, suggesting that SMAD4 was not required in BMP4-induced MEIS2 expression. Evidence from previous studies showed that canonical SMAD signaling had different effects on the expression of homeobox genes during odontogenesis. It’s demonstrated that canonical SMAD signaling played a positive role in regulating BMP4-induced DLX2 activity, and depletion of SMAD4 decreased the expressions of DLX2 after BMP4 stimulation [15]. On the contrary, all the 39 paralogous proteins in HOX family were BMPs downstream transcription factors but Smads oppose Hox transcriptional activities. For example, Smad6 was found to inhibit Hoxc8- and Hoxb7-induced osteoprotegerin (OPG) transactivation [44]. However, consistent with our findings, the expression of homeobox gene Msx1 in dental mesenchymal cells during odontogenesis was also independent of Smad4. In the absence of Smad4, BMPs were still able to induce phospho-Smad1/5/8 nuclear translocation and direct binding to the Msx1 promoter in dental mesenchymal cells [48]. Based on these findings, we could believe that MEIS2 probably act as a downstream DNA-binding protein in BMP signaling cascade, and we could further speculate that an atypical canonical BMP signaling (SMAD4-independent) pathway may be regulate homeobox gene MEIS2 in the dental mesenchyme during odontogenesis. Yet future work will deserve to elucidate precise signaling pathways and regulation mechanisms of MEIS2 in osteogenic differentiation of MSCs.

Dental tissues have been identified as easily accessible sources of multipotent postnatal stem cells. Dental tissue derived MSCs are using as a new and powerful tool in dental/bone tissue engineering [49]. DPSCs had the ability to differentiate into osteoblasts and endothelial cells, and form the woven bone [50]. When transplanted into immunocompromised rats, DPSCs generated bone tissue with an integral microcirculation, similar to that of mature bone [51]. This ability of DPSCs in osteogenesis as well as their high proliferation rate makes them good candidates for the study of bone formation [52]. SCAPs, combined with PDLSCs in hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate (HA/TCP) scaffolds, when transplanted into the socket of swine, could regenerate a bio-root structure capable of supporting a porcelain crown and exhibited normal functions [53]. Therefore, SCAPs and DPSCs are believed to have broad prospects as novel seed cells for bone and dental regeneration [54]. However, the mechanisms of osteogenic differentiation of dental MSCs are still largely unknown, which have largely restricted their further wide application in regeneration. Our studies provide in vitro evidence that MEIS2 functions as a positive regulator in maintenance of the osteogenic differentiation of dental MSCs and implicate a promising gene target to improve the process of osteogenesis.

In conclusion, the foregoing observations collectively revealed that MEIS2 was an important transcriptional factor regulator in osteogenic commitment of dental tissue derived MSCs, and BMP signaling might account for this ability of MEIS2. The present study sheds light on the mechanisms of osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, yet more detailed analysis deserves our further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Beijing Municipal Government (No. Z121100005212004, PXM 2013_014226_000055, PXM 2013_014226_000021, PXM 2013_014226_07_000080, TJSHG201310025005 to S.L.W.).and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81371109 to D.Y. L.).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG, Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13625–13630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240309797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miura M, Gronthos S, Zhao M, Lu B, Fisher LW, Robey PG, Shi S. SHED: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5807–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937635100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, Young M, Robey PG, Wang CY, Shi S. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet. 2004;364:149–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morsczeck C, Gotz W, Schierholz J, Zeilhofer F, Kuhn U, Mohl C, Sippel C, Hoffmann KH. Isolation of precursor cells (PCs) from human dental follicle of wisdom teeth. Matrix Biology. 2005;24:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Yamaza T, Tuan RS, Wang S, Shi S, Huang GT. Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: a pilot study. J Endod. 2008;34:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang J, Sonoyama W, Wang Z, Jin Q, Zhang C, Krebsbach PH, Giannobile W, Shi S, Wang CY. Noncanonical Wnt-4 signaling enhances bone regeneration of mesenchymal stem cells in craniofacial defects through activation of p38 MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30938–30948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Zheng Y, Ding G, Fang D, Zhang C, Bartold PM, Gronthos S, Shi S, Wang S. Periodontal ligament stem cell-mediated treatment for periodontitis in miniature swine. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1065–1073. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostowska A, Kobielak A, Trzeciak WH. Molecular basis of non-syndromic tooth agenesis: mutations of MSX1 and PAX9 reflect their role in patterning human dentition. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:365–370. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vieira AR, Meira R, Modesto A, Murray JC. MSX1, PAX9, and TGFA contribute to tooth agenesis in humans. J Dent Res. 2004;83:723–727. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson D. The function and evolution of Msx genes: pointers and paradoxes. Trends Genet. 1995;11:405–411. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Depew MJ, Liu JK, Long JE, Presley R, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA, Rubenstein JL. Dlx5 regulates regional development of the branchial arches and sensory capsules. Development. 1999;126:3831–3846. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selleri L, Depew MJ, Jacobs Y, Chanda SK, Tsang KY, Cheah KS, Rubenstein JL, O’Gorman S, Cleary ML. Requirement for Pbx1 in skeletal patterning and programming chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Development. 2001;128:3543–3557. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan MQ, Tare R, Lee SH, Mandeville M, Weiner B, Montecino M, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. HOXA10 controls osteoblastogenesis by directly activating bone regulatory and phenotypic genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3337–3352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01544-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng XY, Zhao YM, Wang WJ, Ge LH. Msx1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of mouse dental mesenchymal cells in culture. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121:412–420. doi: 10.1111/eos.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qu B, Liu O, Fang X, Zhang H, Wang Y, Quan H, Zhang J, Zhou J, Zuo J, Tang J, Tang Z. Distal-less homeobox 2 promotes the osteogenic differentiation potential of stem cells from apical papilla. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;357:133–143. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1833-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon JA, Hassan MQ, Koss M, Montecino M, Selleri L, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. Epigenetic regulation of early osteogenesis and mineralized tissue formation by a HOXA10-PBX1-associated complex. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011;194:146–150. doi: 10.1159/000324790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baek K, Baek JH. The transcription factors myeloid elf-1-like factor (MEF) and distal-less homeobox 5 (Dlx5) inversely regulate the differentiation of osteoblasts and adipocytes in bone marrow. Adipocyte. 2013;2:50–54. doi: 10.4161/adip.22019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye L, Fan Z, Yu B, Chang J, Al HK, Zhou X, Park NH, Wang CY. Histone demethylases KDM4B and KDM6B promotes osteogenic differentiation of human MSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyman-Walsh C, Bjerke GA, Wotton D. An autoinhibitory effect of the homothorax domain of Meis2. FEBS J. 2010;277:2584–2597. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-464X.2010.07668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercader N, Leonardo E, Azpiazu N, Serrano A, Morata G, Martinez C, Torres M. Conserved regulation of proximodistal limb axis development by Meis1/Hth. Nature. 1999;402:425–429. doi: 10.1038/46580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paige SL, Thomas S, Stoick-Cooper CL, Wang H, Maves L, Sandstrom R, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Pratt G, Keller G, Moon RT, Stamatoyannopoulos J, Murry CE. A temporal chromatin signature in human embryonic stem cells identifies regulators of cardiac development. Cell. 2012;151:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biemar F, Devos N, Martial JA, Driever W, Peers B. Cloning and expression of the TALE superclass homeobox Meis2 gene during zebrafish embryonic development. Mech Dev. 2001;109:427–431. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agoston Z, Schulte D. Meis2 competes with the Groucho co-repressor Tle4 for binding to Otx2 and specifies tectal fate without induction of a secondary midbrain-hindbrain boundary organizer. Development. 2009;136:3311–3322. doi: 10.1242/dev.037770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agoston Z, Li N, Haslinger A, Wizenmann A, Schulte D. Genetic and physical interaction of Meis2, Pax3 and Pax7 during dorsal midbrain development. BMC Dev Biol. 2012;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choe SK, Lu P, Nakamura M, Lee J, Sagerstrom CG. Meis cofactors control HDAC and CBP accessibility at Hox-regulated promoters during zebrafish embryogenesis. Dev Cell. 2009;17:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heine P, Dohle E, Bumsted-O’Brien K, Engelkamp D, Schulte D. Evidence for an evolutionary conserved role of homothorax/Meis1/2 during vertebrate retina development. Development. 2008;135:805–811. doi: 10.1242/dev.012088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan Z, Yamaza T, Lee JS, Yu J, Wang S, Fan G, Shi S, Wang CY. BCOR regulates mesenchymal stem cell function by epigenetic mechanisms. Nature Cell Biol. 2009;11:1002–1009. doi: 10.1038/ncb1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du J, Ma Y, Ma P, Wang S, Fan Z. Demethylation of epiregulin gene by histone demethylase FBXL11 and BCL6 corepressor inhibits osteo/dentinogenic differentiation. Stem Cells. 2013;31:126–136. doi: 10.1002/stem.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bustin SA. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25:169–193. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caplan AI. Adult mesenchymal stem cells for tissue engineering versus regenerative medicine. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:341–347. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lian JB, Stein GS, Javed A, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Montecino M, Hassan MQ, Gaur T, Lengner CJ, Young DW. Networks and hubs for the transcriptional control of osteoblastogenesis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek WY, Lee MA, Jung JW, Kim SY, Akiyama H, de Crombrugghe B, Kim JE. Positive regulation of adult bone formation by osteoblast-specific transcription factor osterix. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1055–1065. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaback LA, Soung DY, Naik A, Smith N, Schwarz EM, O’Keefe RJ, Drissi H. Osterix/Sp7 regulates mesenchymal stem cell mediated endochondral ossification. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:173–182. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komori T. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by transcription factors. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1233–1239. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karsenty G, Wagner EF. Reaching a genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Developmental Cell. 2002;2:389–406. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Celil AB, Campbell PG. BMP-2 and insulin-like growth factor-I mediate Osterix (Osx) expression in human mesenchymal stem cells via the MAPK and protein kinase D signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31353–31359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors. 2004;22:233–241. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulsamer A, Ortuno MJ, Ruiz S, Susperregui AR, Osses N, Rosa JL, Ventura F. BMP-2 induces Osterix expression through up-regulation of Dlx5 and its phosphorylation by p38. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3816–3826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng ZL, Sharff KA, Tang N, Song WX, Luo J, Luo X, Chen J, Bennett E, Reid R, Manning D, Xue A, Montag AG, Luu HH, Haydon RC, He TC. Regulation of osteogenic differentiation during skeletal development. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2001–2021. doi: 10.2741/2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canalis E, Deregowski V, Pereira RC, Gazzerro E. Signals that determine the fate of osteoblastic cells. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lengerke C, Schmitt S, Bowman TV, Jang IH, Maouche-Chretien L, McKinney-Freeman S, Davidson AJ, Hammerschmidt M, Rentzsch F, Green JB, Zon LI, Daley GQ. BMP and Wnt specify hematopoietic fate by activation of the Cdx-Hox pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Cao X. BMP signaling and skeletogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1068:26–40. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Nie S, Chang C, Qiu T, Cao X. Smads oppose Hox transcriptional activities. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:854–864. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duverger O, Morasso MI. Role of homeobox genes in the patterning, specification, and differentiation of ectodermal appendages in mammals. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:337–346. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hassan MQ, Saini S, Gordon JA, van Wijnen AJ, Montecino M, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. Molecular switches involving homeodomain proteins, HOXA10 and RUNX2 regulate osteoblastogenesis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189:122–125. doi: 10.1159/000151453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balint E, Lapointe D, Drissi H, van der Meijden C, Young DW, Avan WijnenJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. Phenotype discovery by gene expression profiling: mapping of biological processes linked to BMP-2-mediated osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:401–426. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang G, Yuan G, Ye W, Cho KW, Chen Y. An Atypical Canonical Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Signaling Pathway Regulates Msh Homeobox 1 (Msx1) Expression during Odontogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:31492–31502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.600064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng L, Ye L, Zhou XD. Mesenchymal stem cells and tooth engineering. Int J Oral Sci. 2009;1:6–12. doi: 10.4248/ijos.08032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laino G, D’Aquino R, Graziano A, Lanza V, Carinci F, Naro F, Pirozzi G, Papaccio G. A new population of human adult dental pulp stem cells: a useful source of living autologous fibrous bone tissue (LAB) J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1394–1402. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D’Aquino R, Graziano A, Sampaolesi M, Laino G, Pirozzi G, De Rosa A, Papaccio G. Human postnatal dental pulp cells co-differentiate into osteoblasts and endotheliocytes: a pivotal synergy leading to adult bone tissue formation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1162–1171. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamada Y, Nakamura S, Ito K, Sugito T, Yoshimi R, Nagasaka T, Ueda M. A feasibility of useful cell-based therapy by bone regeneration with deciduous tooth stem cells, dental pulp stem cells, or bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for clinical study using tissue engineering technology. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1891–1900. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D, Yamaza T, Seo BM, Zhang C, Liu H, Gronthos S, Wang CY, Wang S, Shi S. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS One. 2006;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrovic V, Stefanovic V. Dental tissue--new source for stem cells. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009;9:1167–1177. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]