Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells for initiating immune responses. DC maturation can be induced by exposing of immature DC to pathogen products or pro-inflammatory factor, which dramatically enhances the ability of DC to activate Ag-specific T cells. In this study, a recombinant calreticulin fragment 39-272 (rCRT/39-272) covering the lectin-like N domain and partial P domain of murine CRT has been expressed and purified in Escherichia coli. Functional analysis studies revealed that rCRT/39-272 has potent immunostimulatory activities in both activating human monocytes and B cells to secrete cytokines. rCRT/39-272 can drive the activation of bone marrow derived DC in TLR4/CD14 dependent way, as indicated by secretion of cytokines IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β. Exposure of DC to rCRT/39-272 induces P-Akt, suggesting that rCRT/39-272 induces maturation of DC through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. The results suggest that soluble rCRT/39-272 is a potent stimulatory agent to DC maturation in TLR4/CD14 and PI3K/Akt dependent pathway. It may play important roles in initiating cellular immunity in vivo and the T cell response in vitro. Thus it could be used for study of DC-based tumor vaccines.

Keywords: Calreticulin, DC, TLR4/CD14, PI3K/Akt

Introduction

Calreticulin (CRT) is a highly conserved soluble protein in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that plays very important roles in regulation of cellular functions [1]. CRT binds to Ca2+ with high affinity and is crucial for regulating Ca2+ homeostasis [2]. Similar to other molecular chaperones, CRT can help newly synthesized polypeptide chain folding correctly and transporting to the cell membrane. Although CRT is an ER-resident protein, it also appears on the membrane of many kinds of cells such as lymphocytes, neutrophils and apoptotic cells. The cell surface CRT (csCRT) participates into the cell adhesion, clearance of apoptotic cells, anti-tumor immune response, and immuno-modulatory process [3-8]. Previously studies have revealed that soluble CRT can be detected in the sera of patient with auto-immune diseases, which indicates CRT may have direct stimulatory functions to immune cells in vivo and may participate in the pathogenesis of auto-immune diseases [9]. Additionally, CRT is a molecular chaperone that has potent immunological activity [10,11]. Chaperones are proposed to shuttle their associated peptides into antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to induce peptide-specific adaptive immune responses, while eliciting the co-stimulatory responses including dendritic cells (DCs) activation and cytokine production [12]. Recent study indicates that chaperones can activate the innate immune system, possibly through DCs, which is sufficient to elicit tumor rejection [6,13]. As an endogenous signal, chaperons released from dying cells may also exacerbate autoimmune diseases [12,14,15]. It has been proposed that CRT may facilitate induction of the immune response through interaction with DCs [16]. Therefore, in this study a recombinant CRT fragment (rCRT/39-272) was used to analyze the putative stimulatory effects on bone marrow derived DCs from BALB/c mice.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice (4-6 weeks) were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Science (Beijing, China). C3H/HeN and C3H/HeJ mice were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China). CD14 knock-out mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). All animals were reared under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Department of Immunology, Peking University.

Recombinant proteins

Expression and purification of rCRT/39-272 and the recombinant GFP (rEGFP) using the E. coli system were performed as previously described [9]. Expression of the recombinant proteins were determined by Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gels and Western blotting.

Generation of immDCs

The cells culture medium was RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml), L-glutamine (2 mM), and 2-ME (5×10-5 M).

BALB/c mouse bone marrow cells were flushed out from the femur and tibiae. The red blood cells (RBC) were lysed with ACK lysis buffer. Then, bone marrow cells (5×106 cells/well) were incubated in 6-well flat bottomed plates (Falcon, USA) in RPMI 1640 medium at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 5 days. The recombinant mouse GM-CSF (rmGM-CSF, PeproTech EC Ltd, UK) was added to the culture (20 ng/ml). At day 3, the medium was replaced with 3.5 ml of fresh medium containing rmGM-CSF. At day 5, the non-adherent cells were harvested.

Cytokine production assays

Freshly prepared C3H/HeN and C3H/HeJ mouse, C57 and CD14 knock-out mouse immDCs were stimulated with rCRT/39-272 (30 μg/ml to 1 μg/ml), LPS(3 μg/ml) in RPMI 1640 medium for 24 h at 37°C. The concentrations of IL-12/IL-23 (P40) and IL-1β, MCP-1 in the culture supernatant were determined using ELISA kits (eBioscience, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard curves were established using corresponding mouse recombinant standard substance.

Flow cytometric analysis

DC was collected, washed with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, USA) in PBS. The cells (1×106 cells/tube) were incubated for 40 min at 4°C with 1 μl of FITC-conjugated antibodies. After washing, the cells were subjected to analysis using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACScan, Becton-Dickinson, Rutherford, NJ, USA).

Western blotting

Proteins were separated in 12% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes at a constant current of 300 mA using a Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The Akt Rabbit mAb and Phospho-Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling, USA) were used. After three washes with TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, blots were incubated for 1 h with HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, USA). The signals were visualized using the ECL detection system as recommended by the manufacturer (Applygen Technologies, Beijing, China).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. The results were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the independent samples t test or two-sided, paired t test between groups using the SPSS 14.0 program (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

rCRT/39–272 activates DCs and induces the phenotypic maturation of DCs in vitro

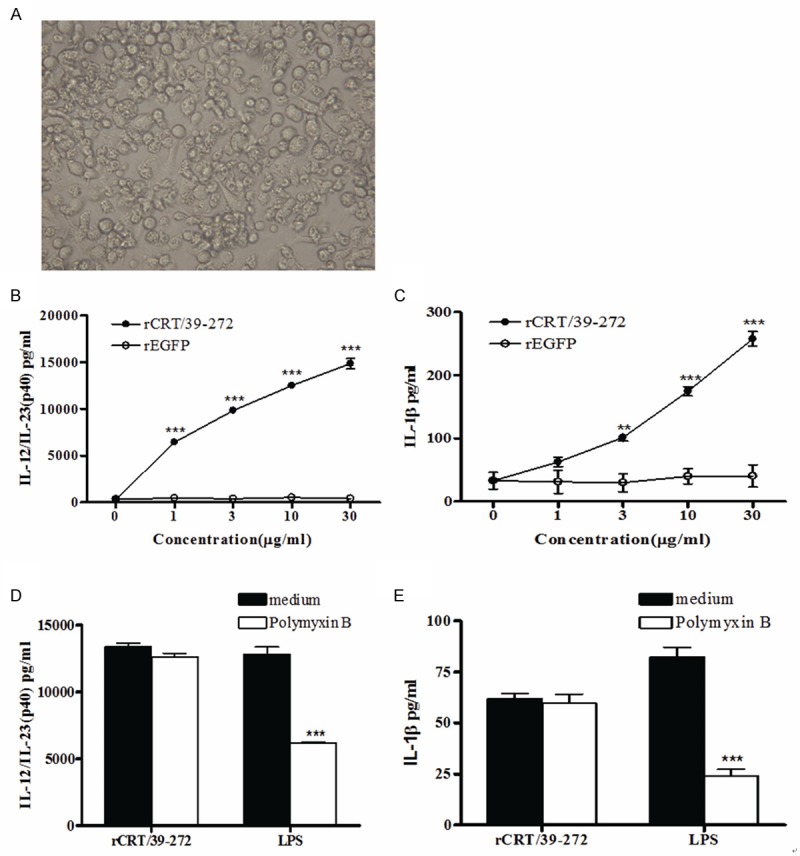

Activation of DCs is the initial step in mediating adaptive immune response. Activated DCs present antigen peptide-MHC complexes to initiate the proliferation and differentiation of naïve T cells [17]. Immature DCs (immDCs) induced from BALB/c mouse bone marrow cells using recombinant murine GM-CSF (rmGM-CSF) were used to study the stimulatory functions of rCRT/39-272. After 5 days culture period in vitro, the induced immDCs have classical DC morphology (Figure 1A). immDCs were treated with rCRT/39-272 in vitro for 24 h and the secreted cytokines in culture supernatants, IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β, was measured by cytokine quantitative ELISA. As a result, rCRT/39-272 upregulated the secretion of p40 and IL-1β in a dose-dependent way, however, rEGFP, a protein expressed and purified using the same system, had no obvious effect to activate DCs to secrete cytokines (Figure 1B, 1C). To exclude the possibility that the rCRT/39-272 form E. coli system may have endogenous LPS contamination, polymyxin B (a LPS antagonist blocking the LPS effect) was added to the culture in the presence of rCRT/39-272 or LPS. As shown in Figure 1D and 1E, addition of polymyxin B could effectively inhibit the IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β secretion by LPS stimulated DCs but not rCRT/39-272 stimulated DCs.

Figure 1.

rCRT/39-272 stimulates DCs to secrete cytokines. ImmDCs were induced from BALB/c mouse bone marrow cells using 20 ng/ml GM-CSF for 5 days, and the morphology of induced immDCs is shown (A). ImmDCs (5×104 cells/well) were stimulated with either rCRT/39-272 or rEGFP (1, 3, 10 or 30 μg/ml) in triplicate wells in 96-well plates for 24 h. The culture supernatants were then harvested and quantitatively assessed for the content of IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β using ELISA kit (B, C). ImmDCs were stimulated with rCRT/39-272 (10 μg/ml) or LPS (3 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of polymyxin B at 10 μg/ml in triplicate wells in 96-well plates for 24 h. The culture supernatants were then harvested and quantitatively assessed for the content of IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β using ELISA kit (D, E). Results were presented as the mean concentration (μg/ml) ± SD of triplicate wells. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

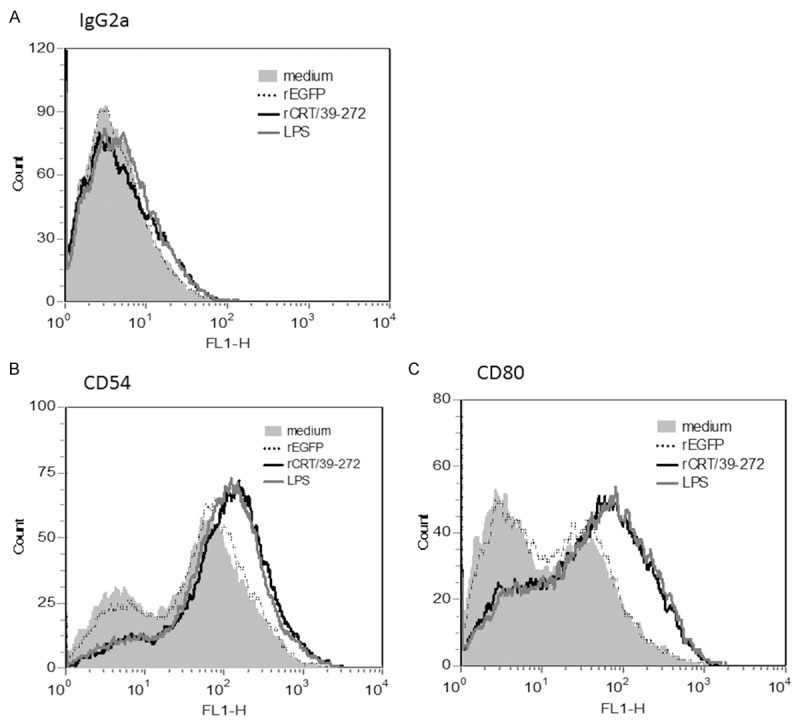

When exposed to various stimuli, immDCs can differentiate into mature DCs (mDCs), which evokes T cell response in vivo. ImmDCs have a strong ability to efficiently capture antigens and endocytosis, but maDCs have reduced this ability, and the stimulus for maturation influences the types of subsequent immune response [18,19]. To investigate the effects of rCRT/39-272 on the maturation of immDCs in vitro, phenotypic of immDCs followed by rCRT/39-272 stimulation was studied. Treatment with rCRT/39-272 led to the up-regulation of CD54 and CD80 (Figure 2) as well as CD40 expression, but not CD83, CD86 and MHC class II expression (data not shown).

Figure 2.

rCRT/39-27 treatment induces phenotypic maturation of immDCs. Bone marrow-derived innDCs from BALB/c mouse (5×105 cells/well) were either stimulated with rCRT/39-272 (30 μg/ml), rEGFP (30 μg/ml), LPS (10 μg/ml) or medium alone in 24-well plates for 24 h. The cells were then collected and washed with cold PBS and stained with PE conjugated anti-mouse CD11c, as well as FITC conjugated anti-mouse CD54 (B), CD80 (C) or isotype control (A). CD11c-positive cells were gated as DCs. Shaded histogram represent DCs treated with medium alone, dotted lines, dashed lines and solid lines represent DCs treated with rEGFP, LPS and rCRT/39-272 respectively. Results represented one of three independent experiments.

TLR4/CD14 signaling pathway is involved in the rCRT/39-272 activation of immDCs

The biological activity of rCRT/39-272 is similar to LPS, which activates B cells and macrophages mainly through the TLR4/CD14 pathway [9,10,20]. So we next investigated whether the activation of immDCs by rCRT/39-272 is also TLR4/CD14 dependent. CD14 and TLR4 deficient mice were used to check the proposal.

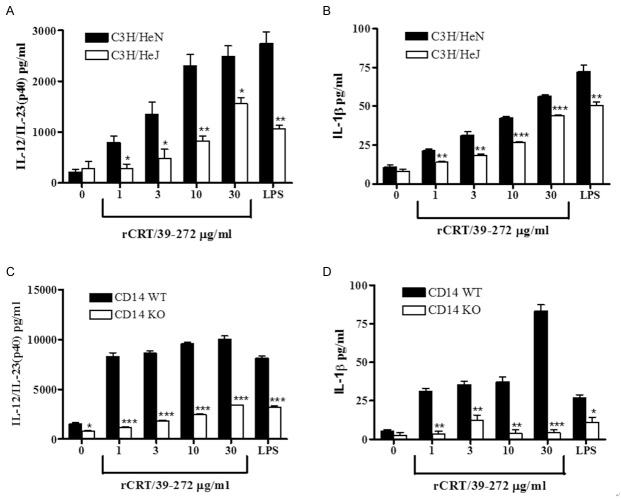

Two pairs of mice were used to test the stimulatory function of rCRT/39-272, one was C3H/HeJ mice (expressing nonfunctional mutant TLR4) and C3H/HeN mice (expressing wide-type TLR4), and the other was wild type C57BL/6 mice (CD14 wildtype) and CD14 knock-out mice with C57BL/6 background. After stimulated by rCRT/39-272 at gradient concentration for 24 h, DCs from C3H/HeJ mice produced much less IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β (Figure 3A and 3B) compared with that from C3H/HeN mice. As expected, the same result was also observed in the other pair of mice that rCRT/39-272 treated DCs from CD14 WT mice produced more cytokines than that from CD14 knock-out mice (Figure 3C and 3D). Thus we concluded that rCRT/39-272 activates mouse DCs mainly through the TLR4/CD14 pathway.

Figure 3.

DCs activated by rCRT/39-272 is TLR4/CD14 dependent. Bone marrow-derived DCs (5×104 cells/well) from C3H/HeN and C3H/HeJ (TLR4 knock out) mice (A, B), CD14 WT (wild type) and CD14 KO (knockout) mice (C, D) were stimulated with either rCRT/39-272 at different concentrations (0 μg/ml to 30 μg/ml) or LPS (3 μg/ml) in triplicates for 24 h. The culture supernatants were collected after 24 h of incubation and the concentration of IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β was determined by ELISA at OD492 nm. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate cultures from one of the three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is involved in the maturation of DCs by rCRT/39-272

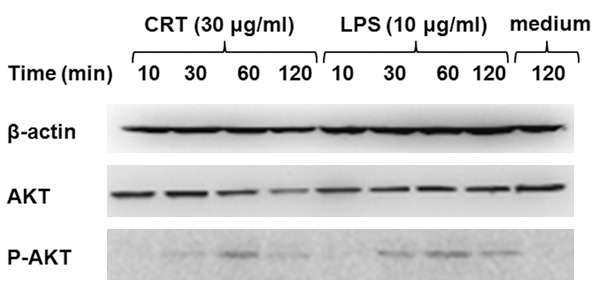

Next we further examined the mechanisms involved in the activation of DCs by rCRT/39-272. Since the PI3K/Akt pathway is another pathway downstream of TLR4 [21], it may be important in mediating rCRT/39-272 induced DC maturation. To determine whether the PI3K/Akt pathway is involved during the maturation of DCs by rCRT/39-272, we detected the levels of phosphorylated Akt by Western blot. As shown in Figure 4, the basal levels of phosphorylated Akt in DCs were low, whereas they were profoundly increased upon exposure to either rCRT/39-272 or LPS. The expression of phosphorylated Akt peaked at 60 min after rCRT/39-272 treatment and was declined thereafter. Thus the phosphorylation of Akt was time-dependent upon stimulation and the PI3K/Akt pathway is activated in rCRT/39-272 treated DCs. These data indicated that PI3K/Akt pathway is also involved in the maturation of DCs induced by rCRT/39-272.

Figure 4.

rCRT/39-272 activates DCs through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. BALB/c mouse bone marrow-derived DCs were stimulated with rCRT/39-272 (30 μg/ml) , LPS (10 μg/ml) or medium alone in 24-well plates for indicated times (10 min, 30 min, 60 min and 120 min) at 37°C. Cells were then collected and cell lysate was run on SDS-PAGE gels followed by Western blotting using rabbit Abs against mouse Akt, phospho-Akt and β-actin. Peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG Abs were used for detection, and the results visualized by chemiluminescence and recorded using a CCD system.

Discussion

Our previous study showed that rCRT/39-272 is capable of driving the proliferation of mouse B cells and promoting cytokine secretion of mouse macrophages and human PBMC in vitro [9]. In this study we mainly investigated the immunological function of rCRT/39-272 on immDCs induced with rmGM-CSF from BALB/c mouse bone marrow cells. Maturation of DCs is important for priming T cell responses since the process increases the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the secretion of cytokines, including IL-12/IL-23 and IL-1β, which could induce T cell differentiation [22,23]. We found that rCRT/39-272 activated immDCs to secrete high levels of IL-12/IL-23 (p40) and IL-1β. IL-12 is a Th1 type cytokine which can induce strong Th1 response both in vivo and in vitro [24]. The maturation of rCRT/39-272 stimulated DCs was analyzed by the elevated expression of costimulatory molecules CD40, CD54 and CD80. DCs activated by rCRT/39-272 treatment are partially via the TLR4/CD14 signaling pathway, which is proved by the lower responses to secrete cytokines of DCs from TLR4 mutant C3H/HeJ mice and CD14 knock-out C57BL/6 mice compared with wild-type C3H/HeN and wildtype C57BL/6 mice. We further confirmed that the maturation of DCs by rCRT/39-272 stimulation is also through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

The full-length of CRT is 46 kDa and the 416 amino acid sequence contains three domains: N domain, P domain and C domain. N domain (amino acid 18-197) is a lectin-like globular domain which can associate with glycoproteins like lectins [11,25,26]. Our pervious study have revealed that rCRT/39-272 (containing N domain) could bind with various glycoproteins, including carrageenan, alginic acids, and hyaluronic acids, but not with LPS [9]. CRT has similar immuno-biological activities with heat shock proteins (HSPs), and can be classified to HSPs superfamily [27,28], although no obvious structural homology had been found betwwen CRT and HSPs. HSPs have been reported to be able to activate APCs and modulating innate and adaptive immune responses [10]. When cells undergo activation, infection, necrosis and so on, HSPs can be up-regulated and translocated to the membrane or released to the outer environment [29-35]. For example, extra-cellular Hsp60 has been shown to induce the maturation of human and murine DCs and macrophages, as indicated by up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of the proinflammatory cytokines in these cells [36,37]. Moreover, exposure of CRT on cell surface of apoptotic cells or tumor cells is required for the recognition and engulfment of these cells by macrophages and thus activates the anti-tumor immune response [5,38,39]. Therefore csCRT may act as an immunostimulatory factor to activate immune cells in vivo. We found that CRT is expressed on the surface of many kinds of cells, including DCs, macrophages, U937, Raji and P815, but the function of CRT on these cells are not completely clear [4-6,8,40,41].

DCs are the most APCs, containing up to 100-fold higher levels of MHC-peptide complexes on the cell surface in comparison to other APCs, such as B cells and macrophages [17], which prompt it an eligible tumor vaccine. Experiments using DCs pulsed with tumor-specific antigens or tumor-derived proteins obtained some success in inducing effective anti-tumor responses [42-45]. Maturation of the DCs is necessary for DC-based cancer vaccines since maDCs have a stable phenotype and can prime T-cell responses effectively [46,47]. Since our results showed that rCRT/39-272 has a strong immunological activity to activate BALB/c mouse bone marrow derived DCs and induce the maturation of immDCs, the use of CRT as DC activator is a promising approach for the immunotherapy of cancers and the roles of CRT-activated DCs in anti-tumor vaccine needs further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30890142/31070781), Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Province Higher Education Institutions, and National Key Basic Research Programs (2007CB512406/2010CB529102).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Michalak M, Corbett EF, Mesaeli N, Nakamura K, Opas M. Calreticulin: one protein, one gene, many functions. Biochem J. 1999;2:281–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krause KH, Michalak M. Calreticulin. Cell. 1997;88:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81884-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns K, Helgason CD, Bleackley RC, Michalak M. Calreticulin in T-lymphocytes. Identification of calreticulin in T-lymphocytes and demonstration that activation of T cells correlates with increased levels of calreticulin mRNA and protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19039–19042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho JH, Homma KJ, Kanegasaki S, Natori S. Activation of human monocyte cell line U937 via cell surface calreticulin. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:148–152. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0148:aohmcl>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardai SJ, McPhillips KA, Frasch SC, Janssen WJ, Starefeldt A, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Bratton DL, Oldenborg PA, Michalak M, Henson PM. Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell. 2005;123:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, Fimia GM, Apetoh L, Perfettini JL, Castedo M, Mignot G, Panaretakis T, Casares N, Métivier D, Larochette N, van Endert P, Ciccosanti F, Piacentini M, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med. 2007;13:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porcellini S, Traggiai E, Schenk U, Ferrera D, Matteoli M, Lanzavecchia A, Michalak M, Grassi F. Regulation of peripheral T cell activation by calreticulin. J Exp Med. 2006;203:461–471. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng G, Aldridge ME, Tian X, Seiler D, Zhang X, Jin Y, Rao J, Li W, Chen D, Langford MP, Duggan C, Belldegrun AS, Dubinett SM. Dendritic cell surface calreticulin is a receptor for NY-ESO-1: direct interactions between tumor-associated antigen and the innate immune system. J Immunol. 2006;177:3582–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong C, Qiu X, Li Y, Huang Q, Zhong Z, Zhang Y, Liu X, Sun L, Lv P, Gao XM. Functional analysis of recombinant calreticulin fragment 39-272: implications for immunobiological activities of calreticulin in health and disease. J Immunol. 2010;185:4561–459. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osterloh A, Kalinke U, Weiss S, Fleischer B, Breloer M. Synergistic and differential modulation of immune responses by Hsp60 and lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4669–4680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vassilakos A, Michalak M, Lehrman MA, Williams DB. Oligosaccharide binding characteristics of the molecular chaperones calnexin and calreticulin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3480–3490. doi: 10.1021/bi972465g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava P. Roles of heat-shock proteins in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nri749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker-LePain JC, Sarzotti M, Fields TA, Li CY, Nicchitta CV. GRP94 (gp96) and GRP94 N-terminal geldanamycin binding domain elicit tissue nonrestricted tumor suppression. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1447–1459. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eggleton P, Llewellyn DH. Pathophysiological roles of calreticulin in autoimmune disease. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:466–473. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Routsias JG, Tzioufas AG. The role of chaperone proteins in autoimmunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1088:52–64. doi: 10.1196/annals.1366.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rzepecka J, Rausch S, Klotz C, Schnöller C, Kornprobst T, Hagen J, Ignatius R, Lucius R, Hartmann S. Calreticulin from the intestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus is a Th2-skewing protein and interacts with murine scavenger receptor-A. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1109–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pulendran B, Banchereau J, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski C. Modulating the immune response with dendritic cells and their growth factors. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinchuk LM, Lee SR, Filipov NM. In vitro atrazine exposure affects the phenotypic and functional maturation of dendritic cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;223:206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaddis DE, Michalek SM, Katz J. Requirement of TLR4 and CD14 in dendritic cell activation by Hemagglutinin B from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2493–2504. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz S, Ayala V, Santillán G, Boland R. Activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through P2Y receptors by extracellular ATP is involved in osteoblastic cell proliferation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;513:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.St John EP, Martinson J, Simoes JA, Landay AL, Spear GT. Dendritic cell activation and maturation induced by mucosal fluid from women with bacterial vaginosis. Clin Immunol. 2007;125:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Napolitani G, Rinaldi A, Bertoni F, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Selected Toll-like receptor agonist combinations synergistically trigger a T help er type 1-polarizing program in dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:769–776. doi: 10.1038/ni1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jähn PS, Zänker KS, Schmitz J, Dzionek A. BDCA-2 signaling inhibits TLR-9-agonist-induced plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation and antigen presentation. Cell Immunol. 2010;265:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiro RG, Zhu Q, Bhoyroo V, Söling HD. Definition of the lectin-like properties of the molecular chaperone, calreticulin, and demonstration of its copurification with endomannosidase from rat liver Golgi. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11588–11594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson SP, Williams DB. Delineation of the lectin site of the molecular chaperone calreticulin. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005;10:242–251. doi: 10.1379/CSC-126.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallin RP, Lundqvist A, Moré SH, von Bonin A, Kiessling R, Ljunggren HG. Heat-shock proteins as activators of the innate immune system. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pockley AG. Heat shock proteins as regulators of the immune response. Lancet. 2003;362:469–476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin CA, Kurkowski DL, Valentino AM, Santiago-Schwarz F. Increased intracellular, cell surface, and secreted inducible heat shock protein 70 responses are triggered during the monocyte to dendritic cell (DC) transition by cytokines independently of heat stress and infection and may positively regulate DC growth. J Immunol. 2009;183:388–399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cid C, Regidor I, Poveda PD, Alcazar A. Expression of heat shock protein 90 at the cell surface in human neuroblastoma cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:321–327. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melendez K, Wallen ES, Edwards BS, Mobarak CD, Bear DG, Moseley PL. Heat shock protein 70 and glycoprotein 96 are differentially expressed on the surface of malignant and nonmalignant breast cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2006;11:334–342. doi: 10.1379/CSC-187.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin CA, Carsons SE, Kowalewski R, Bernstein D, Valentino M, Santiago-Schwarz F. Santiago-Schwarz, Aberrant extracellular and dendritic cell (DC) surface expression of heat shock protein (hsp) 70 in the rheumatoid joint: possible mechanisms of hsp/DC-mediated cross-priming. J Immunol. 2003;171:5736–5742. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross C, Koelch W, DeMaio A, Arispe N, Multhoff G. Cell surface-bound heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) mediates perforin-independent apoptosis by specific binding and uptake of granzyme B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41173–41181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai J, Liu B, Caudill MM, Zheng H, Qiao Y, Podack ER, Li Z. Cell surface expression of heat shock protein gp96 enhances cross-presentation of cellular antigens and the generation of tumor-specific T cell memory. Cancer Immun. 2003;3:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen-Sfady M, Nussbaum G, Pevsner-Fischer M, Mor F, Carmi P, Zanin-Zhorov A, Lider O, Cohen IR. Heat shock protein 60 activates B cells via the TLR4-MyD88 pathway. J Immunol. 2005;175:3594–3602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flohé SB, Brüggemann J, Lendemans S, Nikulina M, Meierhoff G, Flohé S, Kolb H. Human heat shock protein 6 0 induces maturation of dendritic cells versus a Th1-promoting phenotype. J Immunol. 2003;170:2340–2348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kol A, Lichtman AH, Finberg RW, Libby P, Kurt-Jones EA. Cutting edge: heat shock protein (HSP) 60 activates the innate immune response: CD14 is an essential receptor for HSP60 activation of mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:13–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alyamkina EA, Nikolin VP, Popova NA, Dolgova EV, Proskurina AS, Orishchenko KE, Efremov YR, Chernykh ER, Ostanin AA, Sidorov SV, Ponomarenko DM, Zagrebelniy SN, Bogachev SS, Shurdov MA. A strategy of tumor treatment in mice with doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide combination based on dendritic cell activation by human double-stranded DNA preparation. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2010;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obeid M, Panaretakis T, Tesniere A, Joza N, Tufi R, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Leveraging the immune system during chemotherapy: moving calreticulin to the cell surface converts apoptotic death from “silent” to immunogenic. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7941–7944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goicoechea S, Orr AW, Pallero MA, Eggleton P, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin mediates focal adhesion disassembly through interactions with cell surface calreticulin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36358–36368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke C, Smyth MJ. Calreticulin exposure increases cancer immunogenicity. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:192–193. doi: 10.1038/nbt0207-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiramoto JS, Tsung K, Bedolli M, Norton JA, Hirose R. Antitumor immunity induced by dendritic cell-based vaccination is dependent on interferon-gamma and interleukin-12. J Surg Res. 2004;116:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kugler A, Stuhler G, Walden P, Zöller G, Zobywalski A, Brossart P, Trefzer U, Ullrich S, Müller CA, Becker V, Gross AJ, Hemmerlein B, Kanz L, Müller GA, Ringert RH. Regression of human metastatic renal cell carcinoma after vaccination with tumor cell-dendritic cell hybrids. Nat Med. 2000;6:332–336. doi: 10.1038/73193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bellone M, Cantarella D, Castiglioni P, Crosti MC, Ronchetti A, Moro M, Garancini MP, Casorati G, Dellabona P. Relevance of the tumor antigen in the validation of three vaccination strategies for melanoma. J Immunol. 2000;165:2651–2656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein C, Bueler H, Mulligan RC. Comparative analysis of genetically modified dendritic cells and tumor cells as therapeutic cancer vaccines. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1699–1708. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trepiakas R, Pedersen AE, Met O, Hansen MH, Berntsen A, Svane IM. Comparison of alpha-Type-1 polarizing and standard dendritic cell cytokine cocktail for maturation of therapeutic monocyte-derived dendritic cell preparations from cancer patients. Vaccine. 2008;26:2824–2832. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Scharenborg NM, Engelen LP, Ruiter DJ, Gerritsen MJ, Croockewit S, Britten CM, Torensma R, Adema GJ, Figdor CG, Punt CJ. Maturation of dendritic cells is a prerequisite for inducing immune responses in advanced melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5091–5100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]