Abstract

Delayed post-pancreaticoduodenectomy hemorrhage (PPH) is a rare but life threatening complication with high mortality. In this retrospective study, we aimed to evaluate the safety, efficacy and utility of interventional treatment of delayed PPH. From January 2008 to December 2013, 357 patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD). 21 patients (5.9%) suffered from the delayed PPH. 18 patients underwent diagnostic angiography and endovascular treatment, either transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE, n = 10) or covered stent placement (CSP, n = 8), and 3 patients underwent laparotomy. The mean time of hemorrhage was 21.4 days. In 10 patients received TAE treatments, 3 got liver damage and 2 presented liver abscesses with 1 died of severe infection and multi-organ failure. Re-bleeding was occurred in 4 of 10 TAE patients. 8 patients received CSP got thoroughly bleeding control and without any ischemic or re-bleeding complications. 2 of 3 laporotomy patients presented hemorrhage recurrence. In all 6 re-bleeding patients, 2 were saved by CSP, while the other 4 died (TAE in 3 and conservative treatment in 1). Early intervention plays an important role of saving patients from delayed PPH. The CSP is considered a fist-line treatment for delayed PPH and an appropriate solution for hemorrhage recurrence. TAE only could be performed in whom placing a covered stent is technically difficult.

Keywords: Pancreaticoduodenectomy, delayed post-pancreaticoduodenectomy hemorrhage, endovascular intervention, covered stent, TAE

Introduction

Post-pancreaticoduodenectomy hemorrhage (PPH) is a less common but potentially life threatening complication with reported incidences between 6-10% and mortality rates of 20-50% in most series [1-5]. The International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) proposed a classification systemic diagnosis and to evaluate the severity of the PPH in 2007 [6]. According to this criteria, early PPH (less than, or equal to, 24 h after the end of the operation) is mostly due to technical failure, incomplete homeostasis, or insufficient management of coagulation disorders, and delayed PPH (greater than 24 h after the end of the operation) mostly caused by pseudoaneurysm rupture with inflammatory erosion of the arterial wall or erosive bleeding of skeletonized vessels [6-8].

Although endovascular interventions (EI) managed by percutaneous angiographic, is considered an increasing role in the successful management of PPH, there is no consensus regarding. EI can be performed in the form of transarterial embolization (TAE) or CSP [9]. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the safety, efficacy and utility of interventional treatment of delayed PPH.

Patients and methods

From January 2008 to December 2013, 357 patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for periampullary tumors (tumors confined to the head of the pancreas, ampulla, distal common bile duct, or papilla) at the Department of Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, Ren Ji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the data of 21 patients who were diagnosed as delayed PPH from the 357 patients. Eighteen of these 21 patients were managed by EI procedure using either TAE (n = 10) or covered stent placement (CSP, n = 8), the others by laporotomy.

The following data were collected: population (age, sex, and indications for PD), hemorrhage characteristics and clinical representation included time of onset, clinical manifestations, bleeding sites, sentinel bleeding (SB), pancreatic fistula (PF), management (diagnostic procedure, units of blood transfused, need for resuscitation, treatment), length of stay in intensive care unit (ICU) and outcomes.

Complications’ definition

The term of SB was first presented in 1991 [10]. It was defined as minor bleeding from the abdominal or nasogastric tube drainage or by the presence of melena or hematemesis. It always happens before the onset of massive delayed PPH and requires no emergency interventions.

Amylase level was measured in the fluid from the drain ducts. It was defined as PF that the amylase levels of drain were three or more times higher than the normal level of serum and the volume of drain more than 10 milliliter per 24 hours.

Surgical procedure

All patients received the classic Whipple resection after resectable assessment. Pancreaticojejunostomy was performed by an end-to-side duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, hepaticojejunostomy was manual anastomosed end-to-side. The gastroduodenal artery (GDA) was ligated with nonabsorbable stitches. A multi-punched silicone drain was placed close to the pancreatic and biliary anastomoses. Somatostatin was routinely administrated in 5 days postoperatively.

Endovascular intervention procedure

EI was performed using either TAE or CSP when PPH was identified, according to the site of bleeding, the vascular anatomy and the devices available. We firstly salvaged patients with intravenous fluids and administration of blood products, till hemodynamic been provisionally stable. The measurement of electrocardiogram and blood pressure were monitored during the whole procedure. All the procedures were carried out in the angiography suite (INNOVA-4100 IQ, GE, USA), and performed under local anesthesia (2% lidocaine).

A 5-French sheath was used to form a femoral access. A 5-French pigtail catheter (Cordis, the Netherlands) was inserted into the abdominal aorta via the access and placed at the level of the 12th thoracic vertebrate. Then the aortography was performed. The celiac trunk, hepatic artery, splenic artery, and superior mesenteric artery were selectively catheterized. Both arterial and portal venous phases were assessed to confirm the bleeding site and the patency of portal vein before EI in all patients. The anatomic variations presentation, the bleeding site, and the diameter and length of the arteries were detected.

TAE was performed using soft platinum microcoils (Hilal microcoils or Tornado microcoils, Cook, USA) of various lengths and diameters. When without pseudoaneurysm, both proximal and distal part to the bleeding site should be embolized. The TAE continuously performed until no contrast agent extravasation. The procedure of cover stent placement was a little complex. A covered stent (Fluency, Bard, USA) with appropriate diameter and length was deployed into the distal part of the bleeding site through an 8 Fr sheath within a 0.035 inch, 300-cm-long guide-wire. Then the stent was properly released to the proximal site of the bleeding site, which was post dilated by inflated balloon (6/20-mm Powerflex 3, Cordis, the Netherlands) to a pressure of 8 atmospheres. If one failed, a second or even a third covered stent was placed in a coaxial overlapping manner to exclude the site of the bleeding or pseudoaneurysm completely. Angiography was repeated to confirm no sign of contrast medium extravasation, and patency of the artery if covered stent elected.

Follow up

All patients accepted EI were sent to the ICU closely monitored. Broad-spectrum antibiotic and blood transfusion were used as needed. Blood routine and biochemistry test were performed every day. An abdominal CT scan was implemented 3-5 days after EI and whenever any complication was suspected. If any signs suggested recurrence of bleeding, EI procedure was performed again if possible. The patients were followed with laboratory blood tests and abdominal enhanced CT scan 2 months after discharge.

Results

29 patients of 357 presented PPH both early and delayed PPH with a rate of 8.1%. The mean age of patients was 62.7 years with the range between 36 and 87 years. The detailed demographic data and the main characteristics are shown in Table 1. Eight patients presented early PPH with a rate of 2.2%, and 21 patients suffered from the delayed PPH with a rate of 5.9%.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of PPH (early and delayed PPH)

| Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | |

| Mean | 62.7 |

| Range | 36-84 |

| Gender | |

| Men | 24 (82.8) |

| Women | 5 (17.2) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Pancreatic head cancer | 14 (48.3) |

| Papilla cancer | 8 (27.6) |

| Common bile duct cancer | 3 (10.3) |

| Ampullary cance | 2 (6.9) |

| Other benign disease | 2 (6.9) |

| ASA | |

| I | 3 (10.3) |

| II | 22 (75.9) |

| III | 4 (13.8) |

| Bleeding time | |

| Early PPH | 8 (27.6) |

| Delay PPH | 21 (72.4) |

The clinical data of 21 delayed PPH are shown in Table 2. The mean time of hemorrhage was 21.4 days (from 2 to 87). Bleeding from the abdominal drain duct was the most common presentation (n = 11, 52.4%). Fifteen patients (71.4%) were identified PF with drain biochemical tests, one was grade A, the others were grade B. The microbiological culture of abdominal drain fluid confirmed 16 positive with various pathogens. SB was presented in 9 of the 21 patients (47.6%) with average 14.3 days (from 2 to 27 days) after PD. Six cases (66.7%) of SB were observed in abdominal drain, 2 in nasogastric tube and 1 in feces. Of these 9 patients, 7 (77.8%) presented both PF and positive results of pathogen culture. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA), which was the most common pathogen of nosocomial infection in our department, was found in abdominal drain in 5 SB patients.

Table 2.

Clinical manifestations about patients with delayed PPH

| Patient NO. | Age (yr)/Sex | Surgery indication | SB at POD (day) | Presentation of SB | PF | Culture of drain | Bleeding at POD (day) | Presentation of bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36/M | Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor | 21 | Abdominal drain | Yes | KPN and EC | 25 | Abdominal drain |

| 2* | 54/M | Carcinoma of the papilla | 22 | Abdominal drain | Yes | PA and KPN | 27 | Abdominal drain |

| 3 | 62/M | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | 24 | Abdominal drain | Yes | PA and EF | 27 | Hematemesis and melena |

| 4 | 72/F | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | - | No | No | EC | 41 | Melena |

| 5 | 67/M | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | - | No | No | PA | 20 | Abdominal drain |

| 6* | 77/M | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | 13 | Abdominal drain | Yes | EF | 19 | Abdominal drain |

| 7 | 46/M | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | 27 | No | No | PA and EC | 38 | Abdominal drain and hematemesis |

| 8* | 57/M | Distal bile cholangiocarcinoma | - | Nasogastric tube | Yes | PA | 87 | Hematemesis and melena |

| 9 | 73/M | Ampullary carcinoma | - | No | No | No | 28 | Hematemesis |

| 10* | 77/M | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | 4 | Abdominal drain | Yes | No | 18 | Abdominal drain and nasogastric tube |

| 11 | 71/M | Distal bile cholangiocarcinoma | - | No | Yes | PA | 9 | Abdominal drain |

| 12 | 58/M | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | 7 | No | No | EF | 10 | Abdominal drain, Hematemesis and melena |

| 13 | 53/M | Carcinoma of the papilla | 9 | Melena | Yes | PA and KPN | 10 | Melena |

| 14* | 75/M | Carcinoma of the papilla | 14 | Nasogastric tube | Yes | EC and CA | 16 | Nasogastric tube |

| 15 | 80/F | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | - | No | No | No | 21 | Hematemesis |

| 16 | 54/M | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | - | No | Yes | KPN | 22 | Abdominal drain and nasogastric tube |

| 17* | 69/M | Carcinoma of the papilla | 2 | Abdominal drain | No | No | 3 | Nasogastric tube |

| 18 | 70/M | Carcinoma of the papilla | - | No | Yes | PA | 6 | Abdominal drain |

| 19 | 45/M | Carcinoma of the papilla | - | No | Yes | No | 2 | Abdominal drain and nasogastric tube |

| 20 | 69/F | Carcinoma of the papilla | - | No | Yes | EC | 14 | Nasogastric tube and hematemesis |

| 21 | 68/F | Carcinoma Of Pancreatic head | - | No | Yes | No | 7 | Nasogastric tube |

POD: Postoperative day; PF: pancreatic fistula; SB: Sentinel bleeding; KPN: Klebsiella pneumonia; EC: Escherichia Coli; PA: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; EF: Enterococcus faecium; CA: Candida albicans;

patients with hemorrhage recurrence.

The initial sites of hemorrhage were seen in Table 3: stump of gastroduodenal artery (GDA, n = 10, Figures 1, 2 and 3), common hepatic artery (CHA, n = 6), CHA and stump of GDA (n = 1), proper hepatic artery (PHA, n = 1), branch of superior mesenteric artery (SMA, n = 1), inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA, n = 1), splenic artery (SA, n = 1). Of the 10 patients treated with TAE, re-bleeding occurred in 4, liver damage in 3, and liver abscess in 2. Two of the 3 patients received laporotomy presented hemorrhage recurrence. No re-hemorrhage was occurred in all 8 patients with the CSP treatments (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Data of clinical intervention in patients with delayed PPH

| Patient NO. | Bleeding site | Transfusion (RCS and FFP unit) | Management | NO. of Coils | Follow-up (time after management) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Branch of SMA | 8 + 6 | TAE | 1 | Survived to the present |

| 2* | PHA | 6 + 6 | TAE | 3 | 3 days, re-bleeding |

| 3 | Stump of GDA | 13 + 10 | CSP | - | Survived to discharge; 13 months, die of tumor metastasis |

| 4 | Stump of GDA | 10 + 8 | CSP | - | Survived to discharge; 18 months, die of tumor metastasis |

| 5 | Stump of GDA | 14 + 12 | TAE | 2 | Liver damage, survived to discharge; 6 months, die of cerebral infarction |

| 6* | CHA | 4 + 6 | TAE | 4 | Liver damage; 2 days, re-bleeding |

| 7 | CHA & Stump of GDA | 8 + 10 | CSP | - | Survived to discharge; 10 months, die of tumor metastasis |

| 8* | Stump of GDA | 8 + 14 | TAE | 3 | 14 days, re-bleeding |

| 9# | CHA | 6 + 4 | TAE | 2 | 5 days, liver abscess; 24 days, die of severe infection & multiorgan failure |

| 10* | Stump of GDA | 18 + 10 | Laporotomy (suture & re-build) | - | 47 days, re-bleeding |

| 11 | stump of IPDA | 8 + 12 | TAE | 2 | Survived to discharge; 15 months, die of tumor metastasis |

| 12 | Stump of GDA | 12 + 14 | CSP | - | Survived to discharge; 21 months, die of tumor metastasis |

| 13 | Stump of GDA | 4 + 8 | TAE | 1 | Liver damage, survived to the present |

| 14* | CHA | 8 + 6 | TAE | 4 | 7days, liver abscess; 16 days, re-bleeding |

| 15 | Stump of GDA | 15 + 14 | CSP | - | Survived to discharge; 7 months, die of tumor metastasis |

| 16 | Stump of GDA | 15 + 10 | CSP | - | Survived to discharge; 3 months, die of tumor metastasis |

| 17* | CHA | 14 + 12 | Laporotomy (suture & re-build) | - | 21 hours, re-bleeding |

| 18 | Splenic artery | 6 + 10 | TAE | 2 | Survived to discharge; 29 months, die of acute pulmonary embolism |

| 19 | Stump of GDA | 12 + 14 | Laporotomy (suture) | - | Survived to the present |

| 20 | CHA | 12 + 8 | CSP | - | Survived to the present |

| 21 | CHA | 7 + 4 | CSP | - | Survived to discharge; 9 months, die of tumor metastasis |

CHA: common hepatic artery; GDA: gastroduodenal artery; IPDA: inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery; SMA:superior mesenteric artery; PD: pancreaticoduodenectomy; PHA: proper hepatic artery; TAE: transcatheter arterial embolization; CPS: covered stent placement; RCS: red blood cell suspension; FFP: fresh frozen plasma;

patients with hemorrhage recurrence;

patients with a dead outcome.

Figure 1.

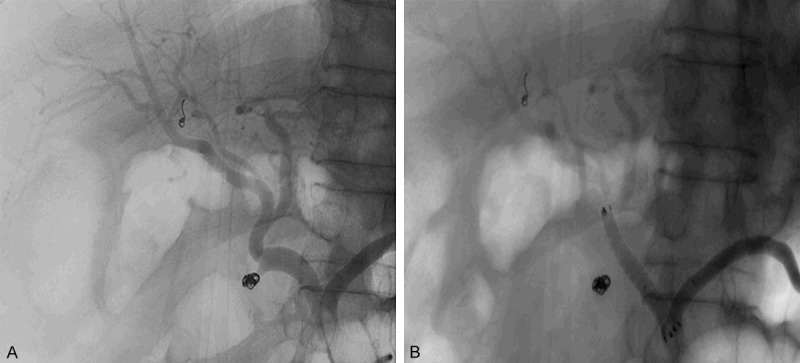

Patient No. 2. A 54-year-old male with adenocarcinoma of the papilla underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Selective angiography was performed and TAE was processed in the stump of GDA. But the hemorrhage reoccurred in 3 days. A. The coil was still at the right site, and no diffusion of contrast agent was come to light. B. Covered stent was placed in the main trunk of CHA, and perfusion of the stump of GDA disappeared immediately.

Figure 2.

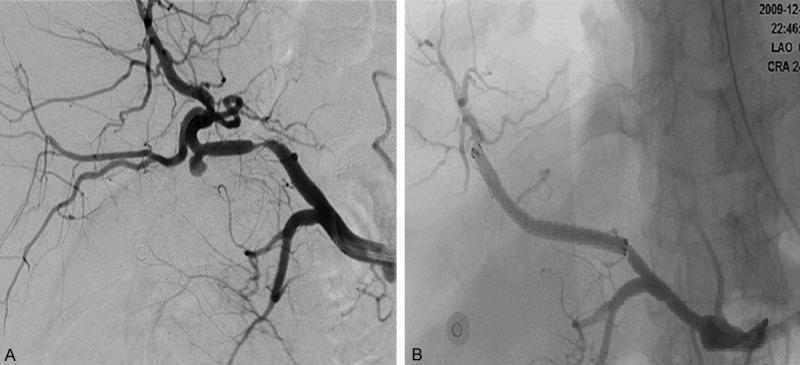

Patient No. 12. A 58-year-old male with Carcinoma of Pancreatic head underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. A. Contrast extravasation was observed at the stump of GDA without a pseudoaneurysm formation. B. Angiography after CSP procedure.

Figure 3.

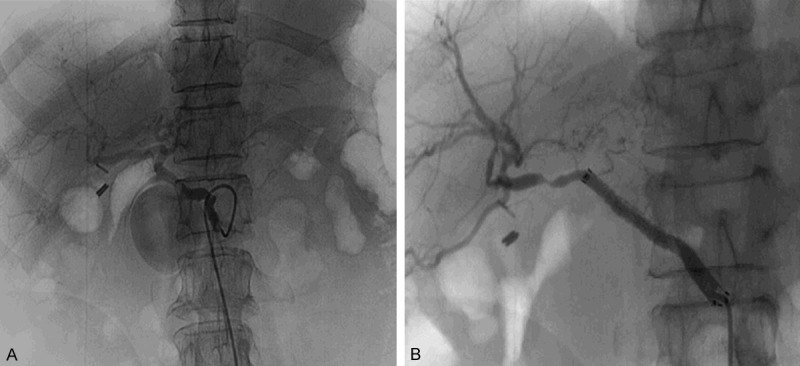

Patient No. 4. A 72-year-old female with Carcinoma of Pancreatic head underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Delayed PPH happened 41 days after surgery with a great lot of melena. A. A distinct pseudoaneurysm of the GDA stump was revealed by angiography. B. Angiography after CSP procedure.

The managements and outcomes of re-bleeding patients were described in Table 4. It was negatively founded both by CT and angiography in patient NO. 2 (Figure 1), but hemorrhage was existed certified by clinical manifestations. The stent was tentatively placed into the CHA to cover the stump of GDA, which was the most likely site of re-bleeding. Then, the presentation of bleeding stopped and the hemodynamic stability was retrieved. In patient No. 8, the intestinal mucosa was developed with contrast agent extravasation from the stump of GDA when angiography was carried out. This sign directly demonstrated the existence of the fistula between stump of GDA and the anastomotic stoma. The bleeding was stopped by placement of stent in the CHA to cover the fistula. Because of the severe infection and unstable hemodynamic situation, conservative treatment was administrated to patient No. 14, who died of uncontrolled re-bleeding finally. The other 3 re-bleeding patients accepted TAE as the final intervention and all died of uncontrolled bleeding and/or multi-organ failure.

Table 4.

Management and outcome of re-bleeding patients

| Patient NO. | Presentation of re-bleeding | Bleeding site | Management | Follow-up (time after management) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Abdominal drain | No active bleeding | CSP | Survived to the present |

| 6# | Abdominal drain | CHA | TAE | died of multi-organ failure |

| 8 | Melena | CHA-intestinal fistula | CSP | Survived to discharge; 4 months, died of tumor metastasis |

| 10# | Abdominal drain | Stump of GDA | TAE | died of uncontrolled bleeding and multi-organ failure |

| 14# | Hematemesis | ---- | Conservative treatment | died of uncontrolled bleeding |

| 17# | Hematemesis | CHA | TAE | died of uncontrolled bleeding and multi-organ failure |

CHA: common hepatic artery; GDA: gastroduodenal artery; TAE: transcatheter arterial embolization; CPS: covered stent placement;

patients with a dead outcome.

Discussion

With the development of the surgical techniques, the mortality of PD decreased dramatically over the past decades [6,11,12]. However, the overall morbidity is still high at 50%-60% even in experienced centers [13-16]. Severe delayed PPH is a rare but life threatening complication with reported morbidity between 6-10% and associated with a high mortality up to 60% [1-5,17,18]. In this study, the morbidity of delayed PPH was 5.9%, which was slightly lower than those reported in the literatures. The end-to-side duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy, which has a lower morbidity of PF, is the only anastomotic method we adopted in this series and may play an important role in this satisfying result.

According to the previous literatures [2,12,19,20], the morbidity of SB was ranged from 33%-73% in delayed PPH cases and the subsequent hemorrhage had a mortality rate of over 50% [1]. In our study, SB was presented in 50% (9/18) delayed PPH patients. And all re-bleeding (n = 6) and died (n = 4) patients were included in these 9 cases. SB, combined with PF and/or intro-abdominal infection was demonstrated in most of the patients with the miserable results (Tables 2, 4). Thus, SB should be aggressively diagnosed and rigorously monitored for hemorrhagic complications to be avoided, especially when a patient manifested SB, PF, and/or intro-abdominal infection together.

Although endovascular techniques have improved over the recent decades, there is no consensus about the procedures of delayed PPH except for immediate resuscitation of hemodynamic stability. Many clinicians have demonstrated that TAE is an effective treatment for delayed PPH [9,21-24]. Meanwhile, in order to avoid ischemia of embolized organs, CSP has been considered as a valid alternative to TAE [2,25-28]. TAE is a relatively easier interventional procedure using coils to embolize the vessel, but a general angiography was required to assess the perfusion status of the distal organ supplied by the embolized artery. If TAE in CHA is needed, the portal blood flow is required to be confirmed by development of portal venous in angiography. In this study, 3 patients with TAE in CHA got liver damage by elevation of aminotransferases, and the other 2 presented liver abscess with 1 died of severe infection and multi-organ failure (Table 3).

Hemorrhage recurrence is another severe complication of TAE. In this study, re-bleeding was occurred in 4 of 10 TAE patients. Of these 4 cases, 2 recovered from re-hemorrhage by CSP and 2 died of uncontrolled bleeding and multi-organ failure, respectively. Hemorrhage recurrence may be caused by incomplete embolization, migration of the coils, and re-dredged of the bleeding artery. Even if a pseudoaneurysm or bleeding vessel is completely embolized, the shake of organ intro-abdominal activation may induce coil compressed or migration [2,29]. In this series, the intestinal mucosa development was observed during angiography in patient NO.8, which suggested an artery-intestinal fistula formation. TAE is not suitable for this patient because of the higher possibility of re-bleeding induced by detachment of the coils. For the same reason, TAE is not recommended in patients with a big crevasse, which to be embolized by more than 3 coils by the assessment of angiography (Table 3).

CSP was reported in a few series handling delayed PPH [24,30]. CSP may be not feasible, which is mainly due to the restriction of anatomic reasons. In those with a tortuous celiac or common hepatic artery, celiac artery stenosis or fine common hepatic artery, it may be difficult to push a covered stent into the proper site. The preservation of arterial blood flow is the most obvious advantage of CSP to deal with pseudoaneurysms of the main trunk of CHA or SMA [20,31], and the redundant portal venous angiography is unnecessary when the CSP is performed. In this study, all patients received CSP (n = 8) got thoroughly bleeding control and without any ischemic complications.

Due to its safety, CPS could be used to handle some uncertain and tricky complications. Patient No. 2 got critical re-bleeding after the TAE treatment at the stump of GDA, but nothing positive was observed in the following emergency angiography. It seemed that bleeding had stopped spontaneously because of hemodynamic instability. Trying to resolve the dilemma, covered stents were empirically placed in the main trunk of CHA to seal the possible bleeding site, and the patient quickly recovered from hypotension and was discharged successfully.

Surgical treatment of massive PPH is related to high mortality and morbidity, which could be up to 90% [11,30,32,33]. In our series, 2 of 3 patients received surgical operations were died from uncontrolled postoperative hemorrhage. Endoscopic procedure is always used in diagnosis and treatment in early PPH patients, and surgical intervention is opted when Endoscopy failed. When delayed PPH presented, EI procedures must be primarily considered rather than surgical interventions unless EI failed.

In summary, prompt and comprehensive assessment and early intervention are as an important role of saving patients from delayed PPH, even after minor bleeding (SB) episodes. SB must be aggressively diagnosed and rigorously monitored for massive hemorrhage to be avoided, especially with PF and/or intro-abdominal infection together. Because the covered stent is better at preserving arterial flow and get lower hemorrhage recurrence than TAE, it is considered a fist-line treatment modality in patients with delayed PPH. TAE could be performed in whom placing a covered stent is technically difficult. When an angiography shows negative but hemorrhage recurrence demonstrated existed after TAE, CSP sealing the possible bleeding lesions may be an appropriate solution and bring forth satisfactory results.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Young Medical Doctors Training and Funding Project of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Yekebas EF, Wolfram L, Cataldegirmen G, Habermann CR, Bogoevski D, Koenig AM, Kaifi J, Schurr PG, Bubenheim M, Nolte-Ernsting C, Adam G, Izbicki JR. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg. 2007;246:269–280. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000262953.77735.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer L, Bonmardion R, Marciano S, Hartung O, Ramis O, Chabert L, Leone M, Emungania O, Orsoni P, Barthet M, Berdah SV, Brunet C, Moutardier V. Results of non-operative therapy for delayed hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:922–928. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanc T, Cortes A, Goere D, Sibert A, Pessaux P, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. Hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: when is surgery still indicated? Am J Surg. 2007;194:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckardt AJ, Klein F, Adler A, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Warnick P, Bahra M, Wiedenmann B, Neuhaus P, Neumann K, Glanemann M. Management and outcomes of haemorrhage after pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreatojejunostomy. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1599–1607. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manas-Gomez MJ, Rodriguez-Revuelto R, Balsells-Valls J, Olsina-Kissler JJ, Caralt-Barba M, Perez-Lafuente M, Charco-Torra R. Post-pancreaticoduodenectomy hemorrhage. Incidence, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Surg. 2011;35:2543–2548. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Yeo CJ, Buchler MW. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limongelli P, Khorsandi SE, Pai M, Jackson JE, Tait P, Tierris J, Habib NA, Williamson RC, Jiao LR. Management of delayed postoperative hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1001–1007. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.1001. discussion 1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puppala S, Patel J, McPherson S, Nicholson A, Kessel D. Hemorrhagic complications after Whipple surgery: imaging and radiologic intervention. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:192–197. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miura F, Asano T, Amano H, Yoshida M, Toyota N, Wada K, Kato K, Yamazaki E, Kadowaki S, Shibuya M, Maeno S, Furui S, Takeshita K, Kotake Y, Takada T. Management of postoperative arterial hemorrhage after pancreato-biliary surgery according to the site of bleeding: re-laparotomy or interventional radiology. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodsky JT, Turnbull AD. Arterial hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. The ‘sentinel bleed’. Arch Surg. 1991;126:1037–1040. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410320127019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santoro R, Carlini M, Carboni F, Nicolas C, Santoro E. Delayed massive arterial hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer. Management of a life-threatening complication. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:2199–2204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon YS, Kim SW, Her KH, Park YC, Ahn YJ, Jang JY, Park SJ, Suh KS, Han JK, Lee KU, Park YH. Management of postoperative hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:2208–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braga M, Capretti G, Pecorelli N, Balzano G, Doglioni C, Ariotti R, Di Carlo V. A prognostic score to predict major complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;254:702–707. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823598fb. discussion 707-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pecorelli N, Balzano G, Capretti G, Zerbi A, Di Carlo V, Braga M. Effect of surgeon volume on outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomy in a high-volume hospital. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:518–523. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1777-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topal B, Fieuws S, Aerts R, Weerts J, Feryn T, Roeyen G, Bertrand C, Hubert C, Janssens M, Closset J Belgian Section of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:655–662. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayo SC, Gilson MM, Herman JM, Cameron JL, Nathan H, Edil BH, Choti MA, Schulick RD, Wolfgang CL, Pawlik TM. Management of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: national trends in patient selection, operative management, and use of adjuvant therapy. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagad RB, Koshariya M, Kawamoto J, Chude GS, Neeraj RV, Lygidakis NJ. Postoperative hemorrhage after major pancreatobiliary surgery: an update. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:729–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hur S, Yoon CJ, Kang SG, Dixon R, Han HS, Yoon YS, Cho JY. Transcatheter arterial embolization of gastroduodenal artery stump pseudoaneurysms after pancreaticoduodenectomy: safety and efficacy of two embolization techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treckmann J, Paul A, Sotiropoulos GC, Lang H, Ozcelik A, Saner F, Broelsch CE. Sentinel bleeding after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a disregarded sign. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:313–318. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding X, Zhu J, Zhu M, Li C, Jian W, Jiang J, Wang Z, Hu S, Jiang X. Therapeutic management of hemorrhage from visceral artery pseudoaneurysms after pancreatic surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1417–1425. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radeleff B, Noeldge G, Heye T, Schlieter M, Friess H, Richter GM, Kauffmann GW. Pseudoaneurysms of the common hepatic artery following pancreaticoduodenectomy: successful emergency embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:129–132. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen T, Matsuoka L, Heestand G, Palmer S, Mateo R, Genyk Y, Selby R, Sher L. Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms of the extrahepatic arterial vasculature: management and outcome. HPB (Oxford) 2006;8:458–464. doi: 10.1080/13651820600839993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Qiu YH, Luo XJ, Yi B, Jiang XQ, Tan WF, Yu Y, Wu MC. Treatment of massive pancreaticojejunal anastomotic hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1625–1629. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang MQ, Liu FY, Duan F, Wang ZJ, Song P, Fan QS. Stent-grafts placement for treatment of massive hemorrhage from ruptured hepatic artery after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3716–3722. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i29.3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasaki K, Ueda K, Nishiyama A, Yoshida K, Sako A, Sato M, Okumura M. Successful utilization of coronary covered stents to treat a common hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to pancreatic fistula after Whipple's procedure: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39:68–71. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaw LL Jr, Saeed M, Brunson M, Delaria GA, Dilley RB. Use of a stent graft for bleeding hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Asian J Surg. 2006;29:283–286. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mansueto G, D’Onofrio M, Iacono C, Rozzanigo U, Serio G, Procacci C. Gastroduodenal artery stump haemorrhage following pylorus-sparing Whipple procedure: treatment with covered stents. Dig Surg. 2002;19:237–240. doi: 10.1159/000064219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paci E, Antico E, Candelari R, Alborino S, Marmorale C, Landi E. Pseudoaneurysm of the common hepatic artery: treatment with a stent-graft. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2000;23:472–474. doi: 10.1007/s002700010107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loffroy R, Guiu B, D’Athis P, Mezzetta L, Gagnaire A, Jouve JL, Ortega-Deballon P, Cheynel N, Cercueil JP, Krausé D. Arterial embolotherapy for endoscopically unmanageable acute gastroduodenal hemorrhage: predictors of early rebleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakai M, Sato H, Sato M, Ikoma A, Sanda H, Nakata K, Minamiguchi H, Kawai N, Sonomura T, Nishimura Y, Okamura Y. Endovascular stenting and stent-graft repair of a hemorrhagic superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm and dissection associated with pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1381–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang ZJ, Wang MQ, Liu FY, Duan F, Song P, Fan QS. Role of interventional endovascular therapy for delayed hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:3110–3117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tessier DJ, Fowl RJ, Stone WM, McKusick MA, Abbas MA, Sarr MG, Nagorney DM, Cherry KJ, Gloviczki P. Iatrogenic hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms: an uncommon complication after hepatic, biliary, and pancreatic procedures. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17:663–669. doi: 10.1007/s10016-003-0075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bassi C, Falconi M, Salvia R, Mascetta G, Molinari E, Pederzoli P. Management of complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy in a high volume centre: results on 150 consecutive patients. Dig Surg. 2001;18:453–457. doi: 10.1159/000050193. discussion 458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]