Abstract

This work aims to compare the curative effect of transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (TUSPLC) and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (FPLC). 200 patients with cholecystolithiasis were enrolled in this study. They were randomly divided into TUSPLC group and FPLC group, 100 cases in each group, and the TUSPLC and FPLC was performed, respectively. The surgical time, intraoperative complication, conversions rate, postoperative pain, postoperative analgesic drug use, incision infection, postoperative hospitalization time and postoperative cosmetic results in two groups were compared. The total conversion rate, conversion rate with Nassar grade II, and conversion rate with Nassar grade III in TUSPLC group were significantly higher than FPLC group (P < 0.01), and the incision cosmetic result after 1 month in TUSPLC group was obviously better than FPLC group (P < 0.01), but the surgical time in TUSPLC group was significantly longer than FPLC group (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference of incision infection, intraoperative complication, and postoperative hospitalization time, incision pain in postoperative first and second day, postoperative use of analgesia drug and incision cosmetic result on discharge day between two groups (P > 0.05). TUSPLC has obvious advantage in treatment of Nassar grade I patients with cholecystolithiasis. It can be used as a supplement for standard laparoscopic gallbladder surgery. It is safe and feasible, without abdominal scar, thus achieving to excellent cosmetic result and high satisfaction in patients.

Keywords: Single-port, four-port, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, comparative study

Introduction

Classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has basically replaced the traditional laparotomy [1]. After years of development, LC has obtained great progress in surgical techniques and indications. So far, LC has experienced four-port method [2], three-port method [3], and two-port method [4]. Due to small trauma and quick recovery, the minimally invasive effect has been fully affirmed. LC has become the gold standard in treatment of benign gallbladder diseases for a long time. In recent years, with the development of minimally invasive technique, transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (TUSPLC) based on the traditional LC technique has appeared. However, the lengths of surgical time are inconsistent due to different surgical apparatus and operational proficiency degree. Podolsky et al. [5] have used self-designed puncture apparatus to perform 5 cases of TUSPLC, with average surgical time of 120 min. Rao et al. [6] have completed 17 cases of TUSPLC using R-Port device, and the average surgical time is 40 mim. In Tacchino et al. report [7], the average surgical time of TUSPLC is 50 min. Overall, with the development of technology, the surgical time of TUSPLC is being shortened gradually.

TUSPLC is proved to be feasible in treatment of gallbladder diseases [8-19], and can improve the cosmetic effect, reduce postoperative pain, shortened postoperative hospitalization time, and improve postoperative life quality [16,19]. However, Mynster et al. [20] believe that, this technique has problems such as interference between equipment and patient, increased operational difficulty, prolonged surgical time, and so on. So it is a new kind of “children’s toy”, and whether it is really beneficial to patients needs to be further confirmed by prospective random control study. Connor et al. [21] believe that, when popularizing a new technique, whether it is really beneficial to patients should be firstly considered. There is no evidence for that the benefit of TUSPLC outweighs the potential risk, and abolition of three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (TPLC) is not necessarily a true progress. Therefore, whether TUSPLC is better than four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (FPLC), and whether it is a development direction in abdominal surgery in the future, need to be quantified and confirmed by relevant clinical data. In addition, whether the surgical time, intraoperative complication, intraoperative conversion rate, postoperative pain, postoperative use of analgesic drug, incision infection, postoperative hospital stay, postoperative cosmetic result in TUSPLC and FPLC are different, still needs to be further confirmed. In this study, 200 patients with cholecystolithiasis in our hospital from January 2010 to December 2011 were divided into TUSPLC group and FPLC group. Based on the difficulty grading of LC, the differences between TUSPLC and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (FPLC) were compared, and the advantage of TUSPLC was observed. At the same time, the indications of TUSPLC were investigated, to reduce the incidence of bile duct injury due to excessive demand of cosmetic result.

Materials and methods

General data

200 patients with cholecystolithiasis in our hospital from January 2010 to December 2011 were enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) aged 18-70 years, body mass index (BMI) ≤ 25 kg/m; 2) no history of surgery on lower digestive tract and pelvic cavity; 3) American Society of Anesthesiologists score (ASA) score: I-III; 4) Nassar grade [22]: I-III (no acute cholecystitis history; Table 1). Exclusion criteria [11] were as follows for: 1) hepatic cirrhosis; 2) peritonitis; 3) history of upper abdominal surgery; 4) complicated with other diseases such as cystic abscess, acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis and biliary calculi; 5) high-risk group of general anesthesia.

Table 1.

Nassar grade of LC

| Nassar grade★ | Gallbladder | Cystic duct structure | Adhesion degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Soft, no adhesion | Clear, thin | Little adhesion in gallbladder neck or Hartmann bag |

| II | Mucous cyst, cystic stone | Rich in fat | Little adhesion in gallbladder body |

| III | Deep gallbladder fossa, atrophy, acute cholecystitis, Hartmann bag, common bile duct adhesion, impacted stones | Anatomic abnormalities, short gallbladder tube, expansion, secluded location | The Tight adhesion in gallbladder bottom, hepatic flexure of colon or duodenum |

| IV | Fully enclosed, purulent, gangrene, block | No clear position | Fibrous tissue encasing gallbladder, hepatic flexure of colon or duodenum adhesion |

Difficulty grading for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

200 patients were randomly divided into TUSPLC group (40 males and 60 females; aged 18-68 years, average 47.5 years; disease course, 1 month to 10 years) and FPLC group (44 males and 56 females; aged 20-70 years, average 50.5 years; disease course ranging from 2 weeks to 12 years). There were 12 and 8 cases complicated with diabetes in FPLC group and TUSPLC group, respectively, and 16 cases and 15 cases complicated with hypertension in two groups, respectively, with 2 cases with multiple complications in each group. Before surgery, the preoperative fasting blood glucose was controlled below 10 mmol/L, with blood pressure below 140/90 mmHg. There was no significant difference of in gender, age, BMI, ASA score and Nassar grade between two groups (P < 0.05).

Research design

All patients were treated by unified perioperative management, without knowing what kind of surgical mode. According to preliminary laparoscopic detection results and difficulty in LC (Nassar grade, Table 1), patients were divided into Nassar I, II and III group (patients with IV grade were excluded), according to which the TUSPLC and FPLC was performed, respectively. The pain scores of operative day, postoperative first day, and postoperative second day were detected using visual analogue scale (VAS) scoring, with range from 1 score (mild pain) to 10 score (sharp pain). The incision pain on postoperative first, second day and postoperative first month was expressed by grade VI, VII and VIII, respectively. It also was evaluated by whether using analgesic drugs. Postoperative incision cosmetic result was evaluated by VAS scoring, ranging from 0% (worst) to 100% (best). The cosmetic results on discharge day and postoperative one month were expressed by grade IX and X, respectively.

Surgical methods

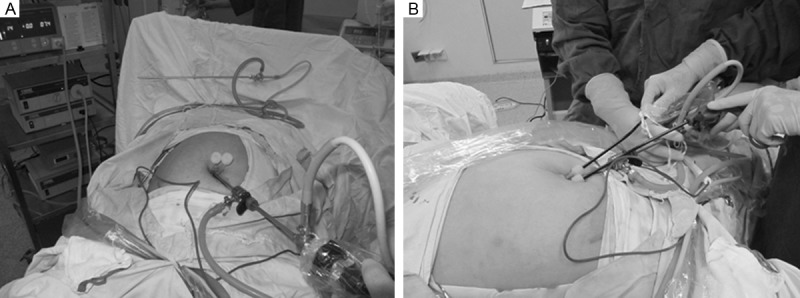

TUSPLC group: under intravenous anesthesia (head side elevated 20-30°, leaning to left 15°), the laparoscopic operation channel was established and pneumoperitoneum was maintained. A 1.5 cm arc incision was made on lower umbilicus edge, and the rectus sheath was exposed, presenting triangle shape. A 5 mm trocar was directly inserted through the central incision to establish pneumoperitoneum and to observe the abdominal cavity. Other two 5 mm trocars were inserted at upper left and right side of first trocar, respectively. The subcutaneous three channels were not mutually connected, and rectus abdominis and rectus sheath were used to prevent gas leakage. The reusable soft trocar (Hangzhou Tonglu Medical Equipment Factory, Hangzhou, China) was inserted (Figure 1A), and the intra-abdominal pressure was maintained at 12-15 mmHg. Two single-port laparoscopes were inserted through the left and right trocar (one for traction and exposure, and the other for dissec tion and separation, Figure 1B). The gallbladder was applied by the forceps to expose the Calot’s triangle, followed by alternate separation using flexible electric hook and separating forceps. The front and rear layer of mesocyst was separated, and the Calot’s triangle was dissected for full isolation of cystic artery and cystic duct, followed by closure and cut-off using 5 mm Ti-clip. The gallbladder was placed in specimen bag. The fascia between trocars was incised, and the specimen bag and gallbladder were taken out through umbilical incision, followed by closing fascia and skin incision.

Figure 1.

A: Soft trocar placement; B: Application of intraoperative devices.

FPLC group: under intravenous anesthesia, the pneumoperitoneum was performed using Veress needle. The intra-abdominal pressure was maintained at 12-15 mmHg. The bladder was excised using traditional method. After surgery, the drainage tube was placed according to the situation of gallbladder bed seepage.

Observation indexes

Surgical time, intraoperative complications, intraoperative conversion rate, postoperative analgesic drug use, incision pain on postoperative first and second day, incision infection, postoperative hospital stay, incision cosmetic results and incision pain on postoperative 1 month were strictly recorded and compared.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 statistical software. t-test and chi-square test were performed for analyzing the measurement data and enumeration data, respectively. Postoperative pain, postoperative hospital stay, incision cosmetic results and incision pain on postoperative 1 month in two groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

In TUSPLC group, due to inflammation around gallbladder and cystic duct structure variation, the gallbladder triangle anatomy was difficult in 16 patients. So two-port method or four-port method or laparotomy method was performed. The surgery was successfully completed in other cases, without bile duct injury. All cases were cured, without death. In FPLC group, 1 case was with difficulty in gallbladder triangle dissection and severe adhesion, so the laparotomy was conducted. The surgery was successfully completed in other cases. The observation indexes in two groups were shown in Tables 2, 3. In one month follow-up, the postoperative incision cosmetic result and incision pain in TUSPLC group was obviously better than FPLC group (p < 0.01). Due to surgical difficulty and high technical requirements, the surgical time in TUSPLC group was longer than FPLC group (P < 0.05). However, with the improvement of operation channel and instruments, the surgical time in TUSPLC group was significantly reduced compared with using old tools. The total conversion rate, conversion rate with Nassar grade II, and conversion rate with Nassar grade III in TUSPLC group were significantly higher than the FPLC group (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference of incision infection, intraoperative complication, postoperative hospital stay, infection pain in postoperative first day and day of surgery, postoperative use of analgesia drug and incision cosmetic effect on discharged day between two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2). All cases were followed up for 1 month, and no residual biliary tract stone, biliary stricture or incision infection was observed. In TUSPLC group, there was no surgical scar in umbilical part, achieving a therapeutic efficacy of minimal invasion, with no abdominal scar. It was safe and feasible.

Table 2.

Comparison of curative effect of two groups

| Intraoperative and postoperative indexes | TUSPLC group | FPLC group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical time (min) | 43.8 ± 2.69 | 36.1 ± 4.89 | <0.01 | |

| Intraoperative complications (cases, %) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Postoperative pain | VI* | 2.22 ± 1.73 | 2.33 ± 1.52 | 0.385 |

| VII★ | 2.39 ± 1.70 | 2.43 ± 1.62 | 0.354 | |

| VIII▲ | 1.61 ± 0.68 | 2.47 ± 1.56 | 0.002 | |

| Analgesic drug use on operative day | 3 | 4 | 0.830 | |

| Postoperative hospitalization time (day) | 3.81 ± 0.85 | 3.86 ± 0.76 | 0.889 | |

| Postoperative-cosmetic-result | IX♦ | 0.822 ± 0.076 | 0.808 ± 0.086 | 0.102 |

| X● | 0.904 ± 0.06 | 0.882 ± 0.047 | 0.003 | |

| Intraoperative total conversion rate | 16 | 2 | 0.001 | |

| Incision infection | 0 | 0 | ||

Note: Data were expressed as mean ± SD;

day of surgery;

first postoperative day;

first month in follow-up;

discharge day;

first month in follow-up.

Table 3.

Comparison of Patient number and interoperation conversion rate with Nassar grading

| Patient number with Nassar grade | TUSPLC group | FPLC group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 80 | 79 | NS | |

| II | 13 | 14 | NS | |

| III | 7 | 7 | NS | |

| Intraoperative conversion rate | Nassar grade I | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Nassar grade II | 10# | 1 | 0.000 | |

| Nassar grade III | 6# | 1 | 0.008 | |

Note: P < 0.01 compared to FPLC group. #conversion rate of two-port method and four-port method.

Discussion

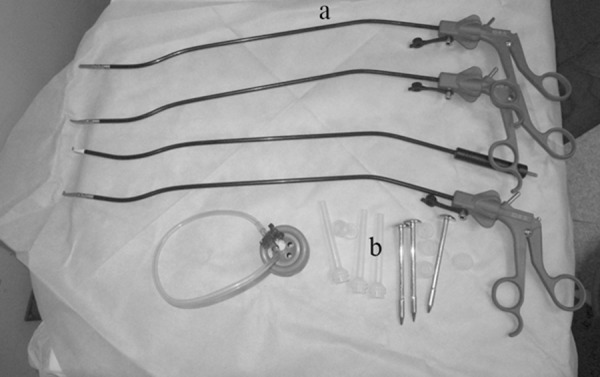

Rapid improvement of endoscopic technique has promoted the development of surgery to more minimally invasive and cosmetic direction. The traditional laparoscopic surgery has transferred from classic four-port method to miniature laparoscopic operation [23] to TUSPLC [12], which is known as E-NOTES, a type of NOTES [24], and also known as TUES [25]. NOTES needs special equipment, and must incise the stomach, rectum, vagina or bladder and other organs. This inevitably increases the complications and surgical risk, and reduces the minimally invasive effect. So it is difficult to be popularized in short time. Compared with NOTES, the advantages of E-NOTES are that, the operation is relatively simple and safe, and it is only performed in patients’ hidden part. There is only a 1.5 cm incision in umbilical region. After healing, the incision scar is difficult to be observed due to natural umbilical barrier. So it is easy to be accepted by patients. According to present situation of single-port laparoscopic surgery, we apply the reusable laparoscopic soft trocar (5 mm diameter), combined with a series of domestic reusable bent laparoscopic instruments (Hangzhou Tonglu Medical Equipment Factory, Hangzhou, China) (Figure 2), and have obtained good surgical result. In the early stage in application of this surgery, the ordinary endoscopic equipments are used, and the surgical time is extended to 1.5-3.0 h. The main reason may be related to unskilled technology in early stage and inherent disadvantages of TUSPLC such as lack of triangle erect position, limited operation space and equipment activity degree. However, since we use a series of domestic reusable single-port laparoscopic instruments (Hangzhou Tonglu Medical Equipment Factory, Hangzhou, China), the triangular area on rectus sheath surface in deep incision is isolated, and three channels are established, with an inverted triangle among them (the distance is about 5-10 mm). So two 5 mm laparoscopic soft trocars can be placed in, which can prevent the gas leakage. In addition, the reusable bent rigid laparoscopic instruments are applied, which can restore the best operating angle of “triangle” in conventional laparoscopic operation, reduce the mutual interference between devices, avoid the crowding of instrument handle with camera handle. This ensures adequate handle activity range, contributing to surgical operation. With accumulation of patient number, the operator has good laparoscopic operation basis and rich experience, so the surgical time in TUSPLC group is significantly reduced. In this study, although the surgical time in TUSPLC group is longer than FPLC group (43.8 ± 2.69 vs 36.1 ± 4.89, P < 0.01), it is close to the mean surgical time of traditional FPLC method. As reported in literatures [26,27], the average surgical time of TUSPLC is 50.8 min (23-120 min) or 80.76 min (51-156 min). Compared with them, the surgical time of TUSPLC in this study decreases significantly, with satisfactory curative effect.

Figure 2.

a: Flexible laparoscopic equipment; b: Reusable soft trocar.

Comparison results of postoperative pain with VAS scoring between traditional LC and TUSPLC showed that, in the 1st and 2nd postoperative day, there is no significant difference of incision pain between two groups (grade VI, 2.33 ± 1.52 vs 2.22 ± 1.73, P = 0.385; grade VII, 2.43 ± 1.62 vs 2.39 ± 1.70, P = 0.354), with comparative analgesic drug use (3 vs 4, P = 0.830). Tsimoyiannis et al. [28] find that, the incision pain at postoperative 12th h in TUSPLC group was markedly relieved, with significantly decreased shoulder pain at postoperative 6th h and disappearance of all pain at postoperative 24th h, and the amount of used analgesic is significantly reduced. This is contrary to our research results, which may be related to surgical incision length and apparatus prepared in our department. In TUSPLC group of this study, the 1.5 cm incision around the umbilicus is made, and the rectus sheath is exposed. Then three 5 mm trocars are directly inserted through the central incision. The single-hole apparatus occupies small space, and not excessively pulls the abdominal muscle and surrounding skin. So at the day of surgery, the pain sense in patients in TUSPLC group is comparative with FPLC group. This is consistent with the view of Saad et al. [29]. However, there is no significant difference of amount of used analgesic drugs at the day of surgery between two groups. This may be due to the relatively low pain level which can be endured by patients.

According to our results, in follow-up of one month, the incision pain in FPLC group are significantly higher than TUSPLC group (1.61 ± 0.68 vs 2.47 ± 1.56, P = 0.002), which may be related to trocar placement. For FPLC, 1 cm trocar is placed in right side below cartilago ensiformis. This position is convenient to get gallbladder. If gallbladder is full of stones or the stone is greater than 1 cm. Expanding the incision and cutting rectus abdominis and nerve tissue below cartilago ensiformis are needed, leading pain under cartilago ensiformis. However, TUSPLC method does not need this operation. The umbilical incision size is about 1.5 cm. If the gallbladder stone is larger, the navel subcutaneous three ports can be fused to increase the incision. In addition, there is no muscle nerve tissue below umbilicus, so the pain is not obvious. On the first and second postoperative day, there is no significant difference of pain between two groups. On the first postoperative month, the cosmetic result in TUSPLC group is better than FPLC group (0.904 ± 0.882 vs 0.06 ± 0.047, P = 0.003). The reason is that, in TUSPLC group, the umbilical scar is almost invisible, while that in FPLC group affects the final cosmetic result. The instruments used in TUSPLC are cheaper, without using expensive special equipment. In addition, the operating apparatus are reusable. The incision infection, intraoperative complications, postoperative hospitalization time, postoperative pain on first and second day, postoperative analgesia drug use and incision cosmetic effect on discharge day in TUSPLC group are comparative to those in FPLC group, which is consistent with previous studies [16,19,30]. These are easy to be accepted by patients, and no postoperative bleeding, bile leakage, bile duct injury or incision infection occurs, indicating that TUSPLC is safe, feasible and effective. One month follow-up after indicates that, in TUSPLC group, the umbilical incision can be concealed by umbilicus fold, with no obvious abdominal scar. So the beauty effect is obvious, with litter psychological impact on patients. However, in 16 patients with Neisser II and III in TUSPLC group, the anatomic variation, deep gallbladder fossa, atrophy, Hartmann bag and common bile duct adhesion or impacted stones, gallbladder bottom tight adhesion, and the mild intestinal adhesion of hepatic flexure of colon and duodenum lead to uncertain surgical safety in a confined space. So the two-port method and four-port method is performed, companied with laparotomy. There is significant difference between TUSPLC group and FPLC group (χ2 = 11.966, P = 0.001) (Table 3). The reason may be that, TUSPLC has defects such as lack of triangle erect position, limited operation space and equipment activity, leading to some difficulties in anatomy of gallbladder triangle. So the intraoperative conversion rate is higher than that in FPLC group. This indicates that, the advantage of TUSPLC is presented in patients with Neisser classification I, but not Neisser grade II and III.

In conclusion, with the improvement of single-port laparoscopic operational channel and application of reusable single-port laparoscopic instruments, TUSPLC technique is more suitable for patients with Nassar grade I, with greater advantage in cosmetic result and incision pain after 1 postoperative month. So it has significant clinical application value. However, in order to ensure the surgical safety of operation, its indication should be strictly applied. Larger multi-center clinical research should be conducted for further investigating the advantage and diagnostic standard of TUSPLC.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Harrell AG, Heniford BT. Minimally invasive abdominal suegery: luxet veritas past, present, and future. Am J Sueg. 2005;190:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer O, Küpker W, Felberbaum R, Gerling W, Diedrich K. Small-diameter-laparoscopy (SDL) using a microlaparoscope. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996;13:298–305. doi: 10.1007/BF02070142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leggett PL, Bissell CD, Churchman-Winn R, Ahn C. Three-port microlaparoscopic cholecystectomy in 159 patients. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:293–296. doi: 10.1007/s004640000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagayat T. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy via two ports, using the “Twin-port” system. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:76–80. doi: 10.1007/s005340170053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Podolsky ER, Rottman SJ, Poblete H, King SA, Curcillo PG. Single port access (SPA) cholecystectomy: a completely transumbilical approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:219–222. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao PP, Bhagwat SM, Rane A, Rao PP. The feasibility of single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a pilot study of 20 cases. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10:336–340. doi: 10.1080/13651820802276622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tacchzno R, Greco F, Matera D. Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: surgery without avisible scar. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:896–899. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0147-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow A, Purkayastha S, Paraskeva P. Appendicectomy and cholecystectomy using single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS): the first UK experience. Surg Innov. 2009;16:211–217. doi: 10.1177/1553350609344413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tai HC, Lin CD, Wu CC, Tsai YC, Yang SS. Homemade transumbilical port: an alternative access for laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) Surg Endosc. 2010;24:705–708. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romanelli JR, Earle DB. Single-port laparoscopic surgery: an overview. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1419–1427. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0463-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong TH, You YK, Lee KH. Transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: scarless cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1393–1397. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langwieler TE, Nimmesgern T, Back M. Single-port access in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1138–1141. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucher P, Pugin F, Buchs N, Ostermann S, Charara F, Morel P. Single port access laparoscopic cholecystectomy (with video) World J Surg. 2009;33:1015–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9874-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gumbs AA, Milone L, Sinha P, Bessler M. Totally transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:533–534. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curcillo PG 2nd, King SA, Podolsky ER, Rottman SJ. Single port access (SPA) minimal access surgery through a single incision. Surg Technol Int. 2009;18:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez JM, Morton CA, Ross S, Albrink M, Rosemurgy AS. Laparoendoscopic single site cholecystectomy: the first 100 patients. Am Surg. 2009;75:681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kommu SS, Chakravarti A, Luscombe CJ, Golash A, Desai MM, Kaouk JH, Gill IS, Cadeddu JA, Rané A. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) and NOTES; standardised platforms in nomenclature. BJU Int. 2009;103:701–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08433_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucher P, Pugin F, Morel P. From single-port access to laparoscopic single-site cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:234–235. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill SI, Advincula AP, Aron M. White paper consensus statement of the Consortium for Laparo-Endoscopic Single-Site (LESS) Surgery. In: Gill SI, editor. Consortium establishes criteria for singleport surgery. Ren Urol News; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mynster T, Wille-jcrgensen P. Single incision laparoscopic surgery: new “toys for boys”? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:351. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connor S. Single-port-access cholecystectomy: history should not be allowed to repeat. World J Surg. 2009;33:1020–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9951-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nassar AHM, Ashkar KA, Mohamed AY, Hafiz AA. Is laparoscopic cholecystectomy possible without video technology? Minim Invasive. Ther Allied Technol. 1995;4:63–65. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karabacak O, Tiras MB, Taner MZ, Guner H, Yildiz A, Yildirim M. Small diameter versus conventional laparoscopy: a prospective, self-controlled study. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2399–2401. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.11.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canes D, Desai MM, Aron M, Haber GP, Goel RK, Stein RJ, Kaouk JH, Gill IS. Transumbilical single-port surgery: evolution and current status. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1020–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu JF. Scarless endoscopic surgery: NOTES or TUES. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1898–1899. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9551-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivas H, Varela E, Scott D. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial evaluation of a large series of patients. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1403–1412. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romanelli JR, Roshek TB 3rd, Lynn DC, Earle DB. Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1374–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsimoyiannis EC, Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos G, Farantos C, Benetatos N, Mavridou P, Manataki A. Different pain scores in single transumbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy velrsus classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1842–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0887-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saad S, Strassel V, Sauerland S. Randomized clinical trial of single-port, minilaparoscopic and conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2013;100:339–349. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lirici MM, Califano AD, Angelini P, Corcione F. Laparo-endoscopic single site cholecystectomy versus standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a pilot randomized trial. Am J Surg. 2011;202:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]