Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to assess treatment outcomes of the Invisalign and compare results with braces. Methods: One hundred and fifty-two adult orthodontic patients, referred to two Orthodontic Specialist Clinics, were randomized to receive either invisalign or brace treatment. All patients were evaluated by using methods from the American Board of Orthodontics Phase III examination. The discrepancy index was used to analyze pretreatment records to control for initial severity of malocclusion. The objective grading system was used to systematically grade posttreatment records. The Wilcoxon 2-sample tests were used to evaluate treatment outcome of Invisalign and braces. Results: The total mean scores of the objective grading system categories were improved after treatment in both groups. The improvements were not statistically significant in scores for alignment, marginal ridges, occlusal relations, over jet, inter-proximal contacts, and root angulation. Invisalign scores were consistently lower than braces scores for buccolingual inclination and occlusal contacts. Conclusions: The overall improvement in OGS scores indicate that both Invisalign and fixed appliances were successful in treating Class I adult extraction cases in this sample.

Keywords: ABO model grading system, invisalign, orthodontic, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Since the introduction of the Invisalign system to the public in 1999, it has become a popular treatment choice for clinicians because of the aesthetics and comfort of the removable clear aligners compared with traditional appliances. However, there was also a concern has arisen among dentists regarding the efficacy of Invisalign treatment. Several studies have shown significant limitations of this technique, especially in treating complex malocclusions, whereas other studies have reported successfully treated cases with this removable appliance [1-4]. A systematic review conducted to determine the treatment effects of the Invisalign system showed that no strong conclusions could be made regarding the treatment effects of Invisalign appliances [5]. Therefore, clinical trials were still required to investigate the effectiveness of the Invisalign system.

Djeu [6] conducted the first retrospective study to compare the outcomes of Invisalign treatment to those of fixed appliances by using the objective grading system of the American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) in a case-controlled study. The results showed that treatment with fixed appliances was significantly more effective than treatment with Invisalign. Invisalignwas least successful in correcting occlusal contacts, posterior torque, and anteroposterior relationships when compared with these entities treated with fixed appliances. Others found the similar results. Chisari and co-workers [7] reported that only 57% of the programmed movement of a single incisor was actually achieved over a course of an 8-week experimental period. In comparison, Kravitz [8] described just a 41% mean accuracy of tooth movement.

Invisalign treatment of extraction case has been reported in few studies that demonstrated successful treatment of four cases of premolar extraction using this appliance [9,10]. However, a case report of upper first premolar extractions showed that space closures of extraction were the result of crown tipping of the adjacent teeth rather than bodily movement. This led to a need to continue the treatment with a phase of fixed appliance therapy to achieve the desired tooth movements [11]. Other case studies have indicated that it was possible to use Invisalign appliances in conjunction with orthognathic surgery to treat severe skeletal jaw discrepancies [12,13].

However, most of past studies have not included a control group or used objective methods to characterize pretreatment malocclusions or evaluate posttreatment results, leaving some doubt among clinicians about the suitability of the appliances. McNamara and others have stressed the importance of continuing studies to expand the understanding of the appropriateness of Invisalign [14-16]. In particular, there has been a paucity of treatment outcome assessments of Invisalign in case-controlled settings. This lack of research has made it difficult for clinicians to objectively characterize the efficacy of Invisalign relative to standard fixed appliances. The few articles in the literature have mainly been case reports and descriptions of the use of the system [17-21].

The main aim of this study was to assess treatment outcomes of the Invisalign system by comparing the results of Invisalign treatment with that of fixed appliances in Class I adult extraction cases.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients aged over 18 yrs; (2) extraction treatment; (3) patients who consented to the research procedures and signed an informed consent; and (4) availability of pre- and post-treatment dental study models and panoramic films with good quality; (5) classified as being severity in complexity with a score of 25 using the Discrepancy Index (DI) of the ABO phase III clinical examination; (6) class I occlusion. Individuals were excluded if: (1) they had undergone previous orthodontic treatment; (2) they had impacted teeth; (3) they were diagnosed concurrently as having systemic diseases; (4) they need for orthognathic surgery. Individuals who failed to comply with the two-month follow-up were excluded and classified as drop-out cases. The intention-to-treat (ITT) was included in the data analysis.

Blinded

Eligible patients were randomized into two groups via a computer generated sequence performed by SAS (Statistical Analysis System): Invisalign group and brace group. The randomization sequences were stored in opaque envelopes by two clinicians who were not involved in the enrollment, intervention implementation, or outcome assessments. The outcome assessors and statisticians were blinded to the allocation.

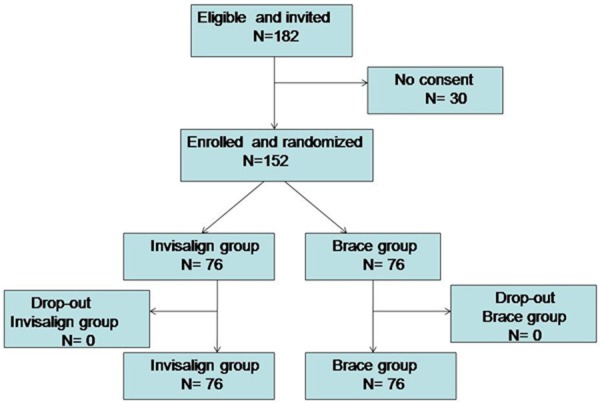

Before data collection, a power index calculation determined that 48 patients would be needed in each group to achieve 80% power. At last, a total of 182 Invisalign and bracket cases obtained from four orthodontist in the Second Affiliated Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine, were planned to participate in the study. Of the 182 cases retrieved, 152 met the inclusion criteria, and 76 (45 female and 27 male patients, 35.2+7.3 y) invisalign who had treated solely with removable Invisalign appliances and 76 (45 female and 27 male patients, 32.2+8.3 y) braces who were fully treated with 3 M brackets (Gemini brand, 3 M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) formed the sample for this study. The difference in the mean age and gender of subjects in both groups were not statistically significant. A detailed flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for participants and dropouts in the trial.

Treatment procedures

For the invisalign group, the Invisalign treatment protocol used for this sample involved the insertion of a series of aligners with instructions for wear 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The aligners were changed every 2 weeks. Malocclusions were corrected with no over-correction introduced. Inter-proximal reduction using diamond strips, if need, was undertaken based on the individual case.

In the brace group, participants received routine fixed appliance treatment. No additional anchorage appliance such as headgears was used during the study period. Elastics were employed for both groups if necessary.

Outcomes assessment

Pre-treatment records were assessed with the DI. Pre-treatment study casts and lateral cephalograms were analyzed by measurements in 10 categories to objectively score severity of malocclusion, in according with the ABO (www.americanboardortho.org). The DI measurements are lingual posterior crossbite, crowding, overjet, cephalometrics, occlusion, anterior open bite, overbite, lateral open bite, buccal posterior crossbite, and other. Points were awarded for deviations from ideal in each category, and the sum of the points gave the DI score. Accordance to the ABO discrepancy index guidelines, a DI score of 7-15 is considered mild, 16-24 is moderated, and 25 or greater is severe.

The primary outcome was measured by the ABO-OGS. The ABO-OGS was used to score both pre- and post-treatment models to determine the outcomes of the Invisalign treatment and braces. The OGS comprises eight categories: buccolingual inclination, occlusal relations, alignment, interproximal contacts, marginal ridges, occlusal contacts, over jet, and root angulation. All measurements were made manually using an ABO measure gauge and by a single operator who was blinded to the type of treatment. Based on the ABO guidelines, a case that scored more than 30 points would likely fail, a case that scored less than 20 points would mostly pass the phase III examination, and a case that scored between 20 and 30 points would be considered a borderline case and might pass or fail.

Statistical analysis

In order to test the reliability and reproducibility of all data, error study analysis were conducted. 15 patient records were selected randomly, retraced and remeasured by the same examiner at an interval of 2 weeks and then compared with the original measurements. Correlation coefficients for the measures were greater than 0.95, which show a great reliability and reproducibility.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS13.0 software (SPSS, Califonia). Chi-square tests were used to determine whether there were any differences in distributions between the Invisalign and braces groups with regard to severity of malocclusion and number of OGS passing scores. Wilcoxon 2-sample tests ascertained whether there was a significant difference between the groups with regard to DI categories, DI score, OGS categories, and OGS score. An alpha error of 0.05 was used as the level of statistical significance for all analyses.

Result

The mean DI scores for the groups were similar, and there was no statistically significant difference between them. The average DI scores were 18.67 for Invisalign patients and 19.85 for braces patients (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups for any of the 10 DI categories.

Table 1.

Pretreatment Discrepancy Index scores for the Invisalign and Brace group

| Measurement | Invisalign | Braces | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Overjet | 3.41 | 1.45 | 3.43 | 2.13 | 0.56 |

| Overbite | 1.53 | 1.08 | 1.62 | 1.32 | 0.87 |

| Anterior open bite | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.64 | 1.21 | 0.90 |

| Lateral open bite | 0.32 | 1.47 | 0.46 | 1.85 | 0.78 |

| Crowding | 5.24 | 2.33 | 5.05 | 2.21 | 0.86 |

| Occlusion | 3.65 | 1.87 | 3.79 | 1.34 | 0.77 |

| Lingual posterior crossbite | 1.41 | 1.01 | 1.36 | 1.20 | 0.78 |

| Buccal posterior crossbite | 0.52 | 1.13 | 0.66 | 1.12 | 0.92 |

| Cephalometrics | 9.35 | 3.23 | 9.80 | 4.12 | 0.23 |

| Other | 0.45 | 1.10 | 0.38 | 1.02 | 0.35 |

| DI score | 26.54 | 7.58 | 28.19 | 8.46 | 0.92 |

Table 2 showed the results for the pre- and post-treatment comparisons using the OGS measurements, the mean ranks for all categories improved after treatment. Overall, significant improvements in the total OGS scores were found post-treatment in both groups.

Table 2.

OGS scores changes in invisalign and brace group

| Measurement | Invisalign Group | Sig | Brace Group | Sig | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T2-T1 | P | T1 | T2 | T2-T1 | P | |||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Mean + SD | Mean + SD | Mean + SD | Mean + SD | Mean + SD | Mean + SD | |||||

| Alignment | 14.26+3.45 | 4.35+3.15 | -9.91+3.56 | .001 | *** | 15.23+3.14 | 4.73+4.12 | -10.50+4.25 | .000 | *** |

| Marginal ridges | 4.56+2.35 | 1.81+3.46 | -2.75+2.13 | .002 | *** | 5.35+4.36 | 1.56+2.89 | -3.79+1.89 | .000 | *** |

| Buccolingual inclination | 7.25+1.02 | 3.70+1.01 | -3.55+1.36 | .001 | *** | 8.82+1.98 | 2.97+1.13 | -5.85+2.68 | .000 | *** |

| Occlusal contacts | 6.13+3.33 | 4.25+3.32 | -1.88+0.13 | 0.32 | NS | 7.22+2.20 | 3.32+4.22 | -3.90+1.12 | .000 | *** |

| Occlusal relations | 6.31+1.36 | 4.35+1.44 | -1.96+1.10 | 0.068 | NS | 6.37+2.18 | 3.40+1.23 | -2.93+1.12 | .000 | *** |

| Overjet | 8.60+2.13 | 3.83+2.65 | -4.77+2.13 | 0.001 | *** | 8.38+1.46 | 2.68+1.23 | -5.7+1.20 | .000 | *** |

| Interproximal contacts | 1.02+1.56 | 0.15+4.32 | -0.87+1.46 | 0.000 | *** | 1.10+1.22 | 0.10+3.88 | -1.00+0.68 | .000 | *** |

| Root angulation | 6.84+1.87 | 2.05+1.58 | -4.79+1.45 | 0.000 | *** | 6.21+1.46 | 1.35+1.25 | -4.68+2.32 | .000 | *** |

| OGS score | 54.97+8.33 | 24.49+7.45 | -30.48+9.23 | 0.000 | *** | 58.68+8.36 | 20.11+6.24 | -38.57+8.87 | .000 | *** |

**P<0.05;

P<0.001;

NS indicates not significant.

The OGS score and six of the 8 OGS categories had no statistically significant differences between the groups. The 2 OGS categories that had scores with a statistically significant difference between the groups were buccolingual inclination and occlusal contacts, Table 3.

Table 3.

OGS scores reflecting mean points lost for deviation from ideal

| Measurement | Invisalign | Braces | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Alignment | -9.91 | 3.56 | -10.50 | 4.25 | 0.14 |

| Marginal ridges | -2.75 | 2.13 | -3.79 | 1.89 | 0.21 |

| Buccolingual inclination | -3.55 | 1.36 | -5.85 | 2.68 | 0.002*** |

| Occlusal contacts | -1.88 | 0.13 | -3.90 | 1.12 | 0.000*** |

| Occlusal relations | -1.96 | 1.10 | -2.93 | 1.12 | 0.42 |

| Overjet | -4.77 | 2.13 | -5.70 | 1.20 | 0.38 |

| Interproximal contacts | -0.87 | 1.46 | -1.00 | 0.68 | 0.87 |

| Root angulation | -4.79 | 1.45 | -4.68 | 2.32 | 0.12 |

| OGS score | -30.48 | 9.23 | -38.57 | 8.87 | 0.25 |

**P<0.05;

P<0.001;

NS indicates not significant.

According to the ABO, a case can lose only 30 or fewer points to receive a passing grade. In the Invisalign group, 48 cases received passing grades, and 24 received failing grades. In the braces group, 60 received passing grades, and 20 received failing grades. There was no statistically significant difference between the passing rate of the Invisalign group and the passing rate of the braces group (Table 4). However, Invisalign required longer treatment duration compared to Braces. Invisalign patients were treated for 31.5 months, whereas Braces patients required 22 months.

Table 4.

Number of cases receiving passing scores (<30 points lost on OGS)

| Invisalign | Brace | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pass | 48 (66.67%) | 60 (75%) | |

| Fail | 24 (33.33%) | 20 (25%) | |

| Total | 72 (100%) | 80 (100%) | 0.52 |

Discussion

The present study was performed to assess treatment outcomes of the Invisalign and compare results with braces in extraction subjects. The results revealed that most of OGS categories had no statistically significant differences between the groups.

It is not suprised to find that Invisalign treatment duration was 44% longer than Brace treatment. Those thought the duration for Invisalign was shorter than brace was probably due to the fact that all the patients were nonextraction. Our results suggest that Invisalign treatment might not be quicker than fixed appliances for premolar extraction patients.

The OGS was used to measure post-treatment patient records to accurately assess treatment outcome of both therapies. A statistically significant improvement in the total OGS scores was found between the pre- and post-treatment in both groups. But there was no statistically significant difference was found between the 2 groups. This improvement indicates that both appliances provides useful orthodontic treatment of moderate-to-severity malocclusion.

Of the eight OGS categories evaluated, only occlusal contacts and buccolingual inclination showed a statistically significant differences between the groups. Although Invisalign and fixed appliances had similar scores on alignment, marginal ridges, interproximal contacts, occlusal relationships, overjet and root angulation, braces therapy had significantly superior scores for correcting buccolingual inclination and occlusal contacts.

The similar OGS scores between Invisalign and braces for alignment and interproximal contacts were expected. The removable aligners are known to consistently produce adequate space closure of up to 6 mm by progressively tipping teeth into spaces in small increments. In terms of alignment, Invisalign has also had success with straightening arches by derotating teeth, especially when composite attachments are bonded to premolars. In previous reports [6,8], these results were largely anecdotal; they have now been confirmed in this study.

However, the similar OGS scores for marginal ridges and root angulation were not expected. The alignment of marginal ridges requires vertical control during tooth movement; braces would presumably do this better than removable aligners. Fixed appliances should have an advantage because of the ability to make precise wire adjustments within 0.5 mm to intrude or extrude teeth as necessary; it has been thought that removable aligners cannot be this accurate [16,17]. In our study, it was shown that the Invisalign and braces groups received comparable scores for the marginal ridge category, indicating that Invisalign indeed can level arches as well as fixed appliances.

The shared success in achieving good root angulation was also surprising. Many study thought that if premolar extraction patients had been included, the Invisalign cases would probably have lost more points than the braces cases for root angulation [9]. Generally, removable aligners can easily tip crowns but cannot tip roots because of the lack of control of tooth movement, especially translating roots through bone. The results of this study, however, indicated no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. This finding might be due to the using of correct attachment could be very good to control the movement of root of extraction patients in the sample. This study confirmed that invisalign could achieve good result in extraction cases.

Previous studies have agreed that occlusal relationships and over jet are not successfully treated with Invisalign alone [4-15]. However, the result showed that invisalign might be ability to adequately correct large anteroposterior (A-P) discrepancies as well as braces. The reason was probably because it is non-extraction plan in previous studies, however, in this study, we could use extraction space to adjust overjet and with the mastering of the doctor to the invisalign technology, we can better use the invisalign to control teeth movement.

The occlusal contact and buccolingual inclination scores for Invisalign were statistically significantly worse than for braces. Certain types of tooth movement, such as extrusion, may be difficult with Invisalign, which probably makes adequate occlusal contacts difficult to achieve using aligners. In addition, the thickness of the aligners over the occlusal surfaces of the teeth might interfere with the settling of the occlusion. Therefore, the use of auxiliaries such as interarch elastics was advocated at the end of the treatment to obtain better occlusal contacts. Furthermore, the results indicated that Invisalign might not sufficiently produce root torque, especially in the posterior region where buccolingual inclination is measured. This problem has been addressed by using the combination technique in conjunction with fixed appliances.

This study is subject to several limitations. The sample size of this study was small and the limited records that fit the inclusion criteria. Thus, the statistical power to detect differences was reduced. In addition, because Invisalign is a relatively new technique, the patients in that group were the first ones treated by the orthodontist. There have been refinements in the technique since then, and practitioners have had 5 years of additional experience. On the other hand, the braces group included patients treated by the orthodontist after decades of experience. Any technique requires a learning curve, and treatment outcome is only as good as the operator’s proficiency, no matter what appliance is used. Therefore, the patients in the braces group might have had an inherent advantage over those in the Invisalign group because of differences in the orthodontist’s experience between the types of treatment.

Conclusions

1. OGS scores were similar in both groups for alignment, marginal ridges, occlusal relations, over jet, interproximal contacts, and root angulation.

2. Invisalign OGS scores for occlusal contacts and buccolingual inclination were not as good as those for braces.

3. The overall improvement in the OGS scores indicates that Invisalign appliances as well as braces were equally successful in treating Class I adult extraction cases.

Acknowledgements

Research partially supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant # Y2110400).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, BeGole E, Obrez A, Agran B. How well does Invisalign work? A prospective clinical study evaluating the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Womack WR. Four-premolar extraction treatment with Invisalign. J Clin Orthod. 2006;40:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Womack WR, Day RH. Surgical-orthodontic treatment using the Invisalign system. J Clin Orthod. 2008;42:237–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamatovic M. A retrospective evaluation of the effectiveness of the Invisalign appliance using the PAR and irregularity indices. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto (Canada); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagravere MO, Flores-Mir C. The treatment effects of Invisalign orthodontic aligners: a systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1724–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djeu G, Shelton C, Maganzini A. Outcome assessment of Invisalign and traditional orthodontic treatment compared with the American Board of Orthodontics objective grading system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisari JR, McGorray SP, Nair M, Wheeler TT. Variables affecting orthodontic tooth movement with clear aligners. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145(Suppl):S82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, Begole E, Obrez A, Agran B. How well does Invisalign work? A prospective clinical study evaluating the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Womack WR. Four-premolar extraction treatment with Invisalign. J Clin Orthod. 2006;40:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honn M, Goz G. A premolar extraction case using the Invisalign system. J Orofac Orthop. 2006;67:385–94. doi: 10.1007/s00056-006-0609-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giancotti A, Greco M, Mampieri G. Extraction treatment using Invisalign technique. Prog Orthod. 2006;7:32–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Womack WR, Day RH. Surgical-orthodontic treatment using the Invisalign system. J Clin Orthod. 2008;42:237–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd RL. Surgical-orthodontic treatment of two skeletal Class III patients with Invisalign and fixed appliances. J Clin Orthod. 2005;39:245–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNamara JA, Brudon WL. Orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics. Ann Arbor (Mich): Needham Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescott TM, Miller R. Interview with Align Technology executives. Interview by David L Turpin. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:19A–20A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlaskalic V, Boyd RL. Clinical evolution of the Invisalign appliance. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2002;10:769–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong BH. Invisalign A to Z. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;121:540–1. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.123036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd RL, Nelson G. Orthodontic treatment of complex malocclusions with the Invisalign appliance. Semin Orthod. 2001;7:274–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo E, Miller RJ. Automated custom-manufacturing technology in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:578–81. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.S0889540603000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen AH. Accelerated Invisalign treatment. J Clin Orthod. 2001;35:381–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyd RL, Miller RJ, Vlaskalic V. The Invisalign system in adult orthodontics: mild crowding and space closure spaces. J Clin Orthod. 2000;34:203–12. [Google Scholar]