Abstract

The bioelectrical properties and resulting metabolic demands of electrogenic cells are determined by their morphology and the subcellular localization of ion channels. The electric organ cells (electrocytes) of the electric fish Eigenmannia virescens generate action potentials (APs) with Na+ currents >10 μA and repolarize the AP with Na+-activated K+ (KNa) channels. To better understand the role of morphology and ion channel localization in determining the metabolic cost of electrocyte APs, we used two-photon three-dimensional imaging to determine the fine cellular morphology and immunohistochemistry to localize the electrocytes' ion channels, ionotropic receptors, and Na+-K+-ATPases. We found that electrocytes are highly polarized cells ∼1.5 mm in anterior-posterior length and ∼0.6 mm in diameter, containing ∼30,000 nuclei along the cell periphery. The cell's innervated posterior region is deeply invaginated and vascularized with complex ultrastructural features, whereas the anterior region is relatively smooth. Cholinergic receptors and Na+ channels are restricted to the innervated posterior region, whereas inward rectifier K+ channels and the KNa channels that terminate the electrocyte AP are localized to the anterior region, separated by >1 mm from the only sources of Na+ influx. In other systems, submicrometer spatial coupling of Na+ and KNa channels is necessary for KNa channel activation. However, our computational simulations showed that KNa channels at a great distance from Na+ influx can still terminate the AP, suggesting that KNa channels can be activated by distant sources of Na+ influx and overturning a long-standing assumption that AP-generating ion channels are restricted to the electrocyte's posterior face.

Keywords: three-dimensional electrolyte morphology, action potential energy efficiency, ion channel compartmentalization, sodium-activated potassium channels

action potentials (APs) are transient changes in membrane voltage that are typically initiated by inward Na+ current (INa) and terminated by outward K+ current (IK). These currents are driven by ionic concentration gradients across the cell membrane (Bean 2007) and transmembrane Na+-K+-ATPases consume energy to restore the ionic gradients after each AP. Total Na+ influx during the AP determines ATPase activity and therefore the resulting metabolic cost of the AP (Attwell and Laughlin 2001; Howarth et al. 2012; Niven and Laughlin 2008). Any temporal overlap of inward INa and outward IK reduces energy efficiency, but this overlap is often necessary in fast-spiking cells, where the need to maintain brief APs requires that IK begins while INa is still active to terminate the AP quickly. This incomplete inactivation of Na+ channels during AP repolarization can result in the entry of twice as much Na+ as the theoretical minimum, significantly reducing energy efficiency at high AP frequencies (Carter and Bean 2009).

The weakly electric fish Eigenmannia virescens generates electric organ discharges (EODs) to navigate and communicate in darkness (Hopkins 1974). Because they generate APs at steady frequencies of 200–600 Hz (Scheich 1977) with underlying Na+ currents that can exceed 10 μA (Markham et al. 2013), the electric organ cells (electroctyes) create extremely high metabolic demands (Lewis et al. 2014). High rates of ATP hydrolysis by the Na+-K+-ATPases are therefore necessary to remove Na+ from the cell between APs. The simultaneous APs of >1,000 electrocytes during each EOD further magnify the metabolic cost of signal production, and as a result, EOD amplitude is highly sensitive to metabolic stress (Reardon et al. 2011).

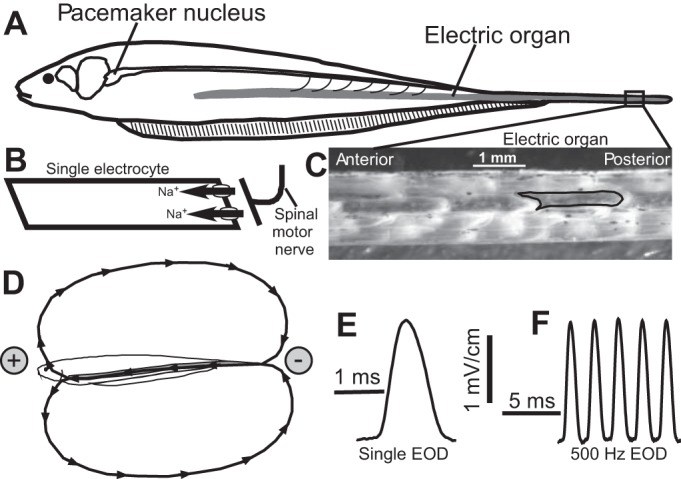

Eigenmannia virescens electrocytes are large cells >1 mm in length, each innervated by spinal motoneurons at a cholinergic synapse on the morphologically complex posterior membrane (Fig. 1B) (Schwartz et al. 1975). Only the posterior membrane generates an AP, with the anterior membrane presumed to be electrically passive (Bennett 1961, 1971). These findings together led to a long-standing assumption that the ion channels responsible for producing the AP are restricted to the posterior region of the cell. Electrocytes express an inwardly rectifying K+ current, a voltage-gated Na+ current, and a Na+-activated K+ (KNa) current that terminates the AP. The expression of KNa channels instead of voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channels increases AP energy efficiency by reducing the overlap of INa and IK during the electrocyte AP (Markham et al. 2013). Early biochemical studies identified Na+-K+-ATPases expressed on both the anterior and posterior membranes (Denizot 1982), but the spatial distribution of the cholinergic receptors and ion channels is not yet known. A full account of the electrocyte's fine morphology and distribution of ionotropic receptors and ion channels is a crucial first step toward understanding the interplay of the ionic currents that determine the spatiotemporal dynamics of intracellular Na+ concentrations that regulate KNa channel activation, ATPase activity, and, ultimately, the metabolic burden of EOD production.

Fig. 1.

Electric organ discharge (EOD) in Eigenmannia virescens. A: the EOD is produced by the coordinated action potentials (APs) of the electrocytes in the electric organ (EO). A medullary pacemaker nucleus controls the electrocyte APs via spinal electromotor neurons that innervate the electrocytes. B: simplified schematic of an electrocyte. These are large cells, >1 mm in length, innervated by a cholinergic synapse on the posterior end of the cell. Activation of the cholinergic synapse initiates the AP when Na+ enters the cell via voltage-gated Na+ channels. The cell geometry causes the Na+ current to move along the rostral-caudal body axis. C: a section of EO from the tail, with skin removed to expose the electrocytes, which are densely packed within the EO. A single electrocyte is outlined in black. D: the simultaneous APs of all electrocytes in the EO generate current that moves forward toward the head, following a return path through the water to the tail. By convention, current moving toward the head is measured as positive (upward). E: a single EOD waveform corresponds to 1 cycle of APs in the EO. F: the EOD waveform from a fish with EOD frequency of ∼500 Hz.

We therefore used confocal laser-scanning fluorescence microscopy and immunohistochemistry to identify the electrocyte's fine three-dimensional (3D) structure and the subcellular localization of their cholinergic receptors, ion channels, and ion transporters. We found that cholinergic receptors and Na+ channels were restricted to the innervated posterior region, whereas inward rectifier K+ channels and KNa channels were localized over 1 mm away in the anterior region. Confirming earlier results (Denizot 1982), Na+-K+-ATPases were densely expressed on both the posterior and anterior membranes. These findings are unexpected because KNa channels that terminate the electrocyte AP and the anterior-membrane Na+-K+-ATPases are separated by more than a millimeter from the only sources of Na+ influx that would activate them. Our computational simulations of electrocyte APs and Na+ dynamics confirm that KNa channels, even at a distance of more than 1 mm from Na+ influx, can terminate the electrocyte AP and maintain high-frequency firing. This discovery is particularly surprising in light of data from other systems where micrometer-scale spatial coupling of KNa and Na+ channels is necessary for KNa channel activation (Budelli et al. 2009; Hage and Salkoff 2012).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Fish were wild-caught male and female E. virescens (glass knifefish). Animals were from tropical South America, obtained from tropical fish importers, and ranged in size from 12 to 19 cm. Fish were housed in groups of 4–10 in 40- or 10-liter tanks in a recirculating aquarium system at 28 ± 1°C with water conductivity of 200–500 μS/cm. The EOD of E. virescens is a sinusoidal wave with a frequency of 250–600 Hz (Fig. 1F). Each positive-going pulse of the wave is a single EOD (Fig. 1, D and E), and these occur at regular intervals under the control of a medullary pacemaker nucleus (Fig. 1, A and B).

We harvested electric organ (EO) tissue from E. virescens by cutting off a small (1–2 cm) piece of the narrow tail filament, consisting of only soft tissue and composed almost entirely of the EO (Fig. 1C). This brief procedure lasts less than 15 s and is performed without anesthesia because induction and recovery from immersion anesthesia are more harmful to the fish than the tail-clip itself. The tail and EO regenerate within 2 mo.

To obtain mouse brains for validating antibodies used in the present study, five C57BL/6J mice (stock no. 664; Jackson Laboratory) were deeply anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation [5% (vol/vol) isoflurane in oxygen] and then decapitated, and brains were quickly removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

All methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Oklahoma and complied with the guidelines given in the Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Confocal Imaging and 3D Reconstructions

Microinjection.

We harvested an ∼2-cm section of the tail, removed the overlying skin, and pinned the exposed EO tissue in a Sylgard (Dow Corning)-coated petri dish containing normal saline (in mM: 114 NaCl, 2 KCl, 4 CaCl2·2H2O, 2 MgCl2·6H2O, 2 HEPES, and 6 glucose; pH to 7.2 with NaOH). Temperature of the preparation was stable at room temperature (22 ± 1°C). Rhodamine B or Alexa Fluor 594 dextran (10,000 MW; Life Technologies) were prepared as a 1% (wt/vol) solution in water. Precipitate within the dextran solution was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 5 min. Microinjections were performed using an automatic nanoliter injector (Nanoject II; Drummond Scientific). Micropipettes for injection were drawn from borosilicate glass capillaries (Drummond Scientific) with a laser micropipette puller (model P-2000; Sutter Instruments). We injected 13.8 nl of dextran solution into the cytoplasm of 4–5 electrocytes in each sample of EO with the constant injection speed of 23 nl/s. The EO tissue with rhodamine B or Alexa Fluor 594 dextran-injected electroctyes was then held in normal saline at room temperature (22 ± 1°C) for 15 min until the dextran fully diffused into injected electrocytes. We then proceeded immediately to image the live cells directly or to fix and section the tissue before mounting and imaging.

Vibratome sectioning.

We fixed the Alexa Fluor 594 dextran-injected EO tissue in 2% paraformaldehyde buffered with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C and washed six times for 15 min each in 1× PBS. The EO tissue was then embedded in 3% agar, trimmed, and glued to a vibratome chuck with cyanoacrylate. The chuck was mounted on a vibratome (Leica Series 1000), and 100-μm sections were cut and mounted on microscope slides using VectaShield with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories).

Confocal imaging.

Live electrocytes were imaged in situ on a Leica TCS SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope, with a Coherent Chameleon mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser and a ×25/0.95NA dipping objective. The images were acquired as serial sections through the entire electrocyte using intensity compensation via increasing detector gain. The entire electrocyte was imaged using a 2 × 4 tiled scan with a 30% overlap between adjacent images. The images were then rendered using a 3D shaded projection in Avizo Fire 8.0.1 (FEI Visualization Sciences Group).

Fixed electrocyte sections were imaged on a Leica TCS SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope using a ×63/1.3NA glycerol objective with a correction collar and an argon laser, a 488-nm laser line to observe tissue autofluorescence, and a DPSS 561-nm laser line to excite the Alexa 594. The images were acquired via serial sections with a voxel size of 160 × 160 × 160 nm and intensity compensation via increasing laser output. The images were then rendered using Imaris ×64 7.6.5 (Bitplane). Electrocyte nuclei were counted by determining the number of DAPI-stained nuclei colocalized with Alexa 594 within an image series from the anterior end, posterior end, or cell body and then extrapolating to the total observed volume of each electrocyte region.

Western Blot

EOs and mouse brains were isolated from animals and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissues were ground into fine powder using a prechilled pestle in a mortar filled with liquid nitrogen. Mouse brain (15 mg) and E. virescens EO tissue powder (100 mg) were dissolved in 1 ml of 1× NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (Life Technologies) containing 2.5% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethonal (Amresco) and then heated at 70°C for 10 min. After heating, protein samples were centrifuged at 17,000 g for 10 min to remove DNA. The collected supernatants were run on a NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris protein gradient gel (Life Technologies) and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using an iBlot dry blotting system (Life Technologies). Membranes were blocked in 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST; Sigma-Aldrich) and 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature under agitation. After blocking, membranes were sequentially incubated with primary antibodies diluted in TBST containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.02% sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich) including rabbit polyclonal anti-kcnt1 (1:200; Aviva Systems Biology), rabbit polyclonal anti-pan Nav (1:200; Alomone Labs), and mouse monoclonal antibody against the α-subunit of Na+-K+-ATPase [a5; 1:1,000; developed by D. M. Fambrough (Lebovitz et al. 1989) and obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) at University of Iowa] at room temperature for 2 h under agitation. After primary antibody incubation, membranes were washed three times for 5 min with TBST. Membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted in TBST containing 5% nonfat dry milk (1:5,000 and 1:2,000 for goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, respectively) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, proteins on the membrane were detected using the Amersham ECL prime Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare) and imaged with a Chemi Doc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad). Exposure time was selected manually depending on the observed signal intensity. The membranes stained with polyclonal anti-pan Nav and mouse monoclonal antibody against the α-subunit of Na+-K+-ATPase were cut to separate the EO and mouse brain strips and then exposed separately because of the large difference in signal intensity between E. virescens EO and mouse brain. Molecular weights of the detected protein were determined by loading Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope standards (Bio-Rad) together with protein samples into the same gel. Final processing of the images was performed with ImageJ for 64-bit Windows (version 1.44B; National Institutes of Health).

Immunohistochemistry

Sections of EO were embedded completely in OCT compound, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen-chilled isopentane (Sigma-Aldrich), and stored at −80°C until further processing. Serial longitudinal sections (15–20 μm thick) were cut at −25°C using a cabinet cryostat (Leica CM 1900), mounted on gelatin-subbed slides, and air-dried overnight at room temperature. Tissue sections were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) buffered with 1× PBS for 20 min, subsequently washed 3 times for 5 min each in 1× PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST; Sigma-Aldrich), blocked in PBST containing 2% bovine serum albumin and 5% goat normal serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in PBST. After primary antibody incubation, tissue sections were washed as described above and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488- or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted 1:200 in PBST for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Sections were then washed and air dried. Slides were mounted using VectaShield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and kept in the dark at 4°C.

A rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100) against an intracellular epitope of Nav1.x channels (anti-pan Nav; Alomone Labs) was used to label voltage-gated Na+ channels. A mouse monoclonal antibody (1:100) against a5 [developed by D. M. Fambrough (Lebovitz et al. 1989), and obtained from the DSHB at University of Iowa] was used to label Na+-K+-ATPase. A rat antibody (1:10) against the muscle-type acetylcholine nicotinic receptor [mAb 35; developed by J. Lindstrom (Tzartos et al. 1981) and obtained from DSHB at University of Iowa] was used to label acetylcholine receptors. A mouse monoclonal antibody (1:100) against neurofilament-associated antigen (3A10; developed by T. Jessel and J. Dodd, and obtained from DSHB at University of Iowa) was used to label axon terminals. A rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200) against KNa channel (anti-Kcnt1; Aviva Systems Biology) was used to label KNa channels. A mouse monoclonal antibody (1:100) against inward-rectifier K+ channel 6.2 (B-9; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to label ATP-sensitive inward rectifier K+ channels.

Immunohistochemistry slides were imaged on a Zeiss ApoTome.2 microscope with ×5/0.16NA and ×10/0.45NA dry objectives. Images were acquired with a Zeiss AxioCam MRm camera and then processed by Zeiss AxioVision Rel. 4.8. We used structured illumination to create optical sections of our fluorescent samples. Final processing of the images was performed with ImageJ for 64-bit Windows (version 1.44B; National Institutes of Health).

Computational Simulations

We modeled the E. virescens electrocyte as a three-compartment cell consisting of an active posterior compartment, a passive central compartment, and an active anterior compartment. We used the Hodgkin-Huxley formalism to simulate ionic currents and changes in membrane voltage. We also applied a simplified model of Na+ entry, diffusion, and pumping to simulate changes in Na+ concentrations in the three compartments. Simulated cholinergic synaptic current was applied only to the posterior compartment. The capacitance was 48.0 nF for the posterior compartment and 18.0 nF for the anterior compartment. We based these values on the surface areas of the posterior 0.35 mm and anterior 0.2 mm of the electrocyte, respectively, with surface areas determined from confocal 3D reconstructions of electrocytes. The central compartment capacitance was 18 nF, estimated as the surface area of a cylinder 0.95 mm long and 0.6 mm in diameter, dimensions determined by our imaging data. Differential equations were coded in Matlab (The MathWorks) and integrated using Euler's method with integration time steps of 5 × 10−8 s. All model parameters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameter values for the electrocyte model

| Posterior Compartment |

Anterior Compartment |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| gL | 40 μS | gL | 20 μS |

| ḡSyn | 600 μS | ḡKNa | 8,000 μS |

| τ | 0.07 ms | kαn | 1.209 ms−1 |

| ηαn | 0.00948 mV−1 | ||

| ḡNa | 700 μS | kβn | 0.4448 ms−1 |

| γ | 0.05 | ηβn | −0.01552 mV−1 |

| kαm | 13.6 ms−1 | kf | 50 mM−1•ms−1 |

| ηαm | 0.0037 mV−1 | kb | 200 ms−1 |

| kβm | 0.6894 ms−1 | ||

| ηβm | −0.0763 mV−1 | ḡR | 100 μS |

| kαh | 0.00165 ms−1 | ηR | 0.22 mV−1 |

| ηαh | −0.1656 mV−1 | ||

| kβh | 1.493 ms−1 | δ | 0.0019 mm2/s |

| ηβh | 0.11 mV−1 | bA | 0.7 mM·ms−1 |

| p | 5 mM·ms−1 | ||

| δ | 0.0019 mm2/s | ||

| bP | 0.3 mM·ms−1 | ||

See text for definitions.

The passive central compartment's current balance equation included only passive leak (IL), fixed at 5 μS, and coupling to the two active compartments:

| (1) |

where Cm is membrane capacitance, VA, VC, and VP are the anterior, central, and posterior compartment membrane voltage, and gw is the coupling conductance, fixed at 322 μS.

The current balance equations for the posterior and anterior active compartments were, respectively,

| (2) |

| (3) |

where ISyn represents synaptic current, INa is Na+ current, IKNa is the Na+-activated K+ current, and IR is the inward-rectifier K+ current. For all three compartments, IL is the leak current, which is given by Eq. 4:

| (4) |

where ḡL is the leak conductance. The posterior compartment synaptic current, ISyn, is given by Eq. 5:

| (5) |

where ḡSyn is the synaptic conductance and the time series gSyn(t) is a series of 10 alpha waveforms generated using the discrete time equation (Graham and Redman 1993):

| (6) |

where T is the integration time step and τ is the time constant. The binary series x(n) specifies the onset times of the synaptic inputs, and the resulting time series gSyn(n) was normalized such that 0 ≤ gSyn(n) ≤ 1.

The equation for INa was divided into a transient component (INaT) and a persistent component (INaP) as in Eqs. 7 and 8,

| (7) |

| (8) |

where ḡNa is the sodium conductance and 0 < γ < 1. ENa, the Na+ equilibrium potential, was allowed to vary with changing Na+ concentrations in the posterior compartment ([NaP]) according to the equation ENa = 25.7 ln (114/[NaP]), assuming 114 mM extracellular Na+ and a temperature of 25°C.

The anterior compartment K+ currents are given by Eqs. 9 and 10:

| (9) |

| (10) |

The gating variables m, n, and h in Eqs. 7–9 are given by Eqs. 11–13, where j = m, n, or h and α, β, and k are rate constants:

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

We modeled the Na+ dependence of IKNa with the gating variable, s, which is determined by the Na+ concentration in the bulk cytoplasm in the anterior compartment ([NaA]), according to Eq. 14:

| (14) |

We modeled Na+ concentrations in each compartment on the basis of the compartmental volumes, which were 4.2 × 107, 2.7 × 108, and 1.7 × 107 μm3 for the posterior, central, and anterior compartments, respectively. The posterior and anterior compartment volumes were measured from our 3D reconstructions of electrocytes, whereas the central compartment volume was estimated as the volume of a cylinder 0.95 mm long and 0.6 mm in diameter. The initial Na+ concentration in all three compartments was 15 mM. The equation for Na+ concentration in the posterior compartment is

| (15) |

where VP is the posterior compartment volume, p represents sodium leak, and q is moles of Na+ ions entering through the cholinergic receptors and Na+ channels, given by Eq. 16:

| (16) |

wherein the integrated Na+ current, dt(2ISyn + INa) in nanoampere-milliseconds (nA·ms), is multiplied by 10−12 to yield coulombs, divided by the elementary charge on a monovalent cation, e, to yield the number of Na+ ions, and divided by Avogadro's constant, L, to yield moles of Na+. ISyn was multiplied by 2 in Eq. 16 to account for Na+ entry associated with ISyn where gSyn arises from cholinergic receptors, assuming the Na+ permeability is twice that of the K+ permeability. Diffusion of Na+ between compartments is governed by δ (the diffusion rate constant), the difference in Na+ concentration between the compartments, and the ratio of their volumes (λ). Na+ removal is modeled by the fractional pumping rate bP, representing the rate at which Na+ is pumped out of the posterior compartment to the extracellular space.

The central compartment's Na+ concentration was affected only by diffusion to and from the posterior and anterior compartments as in Eq. 17:

| (17) |

The posterior compartment Na+ concentration is given by Eq. 18:

| (18) |

which includes diffusion to and from the central compartment, as well as bA, which gives the fractional rate at which Na+ is pumped from the anterior compartment to the extracellular space.

RESULTS

Gross Electrocyte Morphology

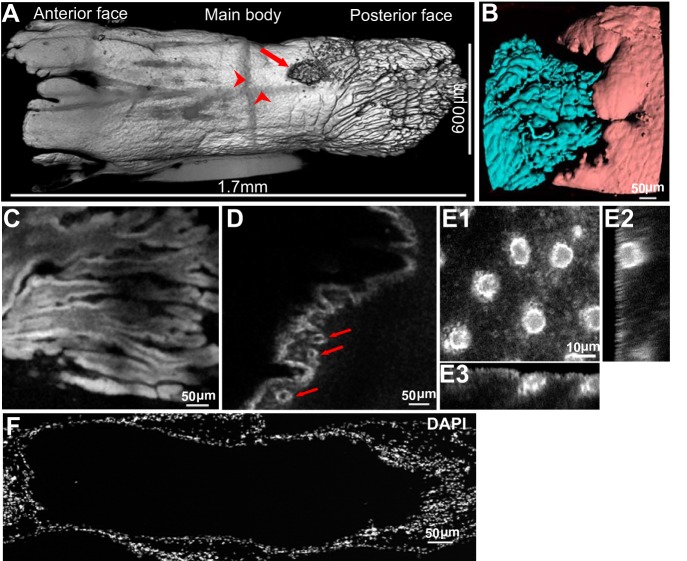

In E. virescens, the EO runs longitudinally along the body and extends into the caudal tail filament (Fig. 1A). Several rows of electrocytes are densely packed in the EO (Fig. 1C). We injected rhodamine B dextran (10,000 MW) into single electrocytes within an isolated section of EO, allowed 15 min for the dextran to fully diffuse, and then imaged the cell on a Leica TCS SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope. Three-dimensional reconstructions of these cells show that electrocytes are large cylinder-like cells ∼1.5 mm in length and 600 μm in diameter (Fig. 2A). The electrocyte's surface structure is not uniform, and based on differences in surface structure, we divided the cell into three regions: the posterior face, the main body, and the anterior face (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Movie 1). (Supplementary data for this article is available online at the Journal of Neurophysiology website.) The space between adjacent electrocytes along the rostral-caudal axis is ∼30 μm, and the posterior face of each electrocyte is surrounded by the anterior face of the adjacent cell (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Gross morphology of E. virescens electrocytes. A: 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction from serial confocal scanning through a live electrocyte injected with rhodamine B dextran (10,000 MW). Arrow indicates site of dextran injection. Darkened horizontal and vertical lines (arrowheads) are artifacts caused by the image tile overlap. Full 3D image is shown in Supplemental Movie 1. B: a segmented autofluorescence image of the junction between two adjoining electrocytes with the posterior face of one electrocyte at left (cyan) and the anterior face of the adjacent electrocyte (pink) at right. C: a single optical section of the posterior face from a rhodamine B dextran-injected electrocyte. The posterior face contains deep invaginations, dramatically increasing the surface area of the cell. Additional detail is shown in Supplemental Movie 2. D: A single optical section of the anterior face from a rhodamine B dextran-injected electrocyte. Arrows indicate penetrating capillary structures within the anterior face. See also Supplemental Movie 3. E: orthogonal sectional views of the spherical structures beneath the membrane of the cell body. E1 shows view looking down at the cell surface. E2 shows a single Y-Z image orthogonal to view in E1, and E3 is a single X-Z image orthogonal to views in E1 and E2. F: a single 20 μm-thick electrocyte section stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to label nuclei (posterior is at right).

The surface of the posterior face was densely occupied by narrow invaginations that extended longitudinally into the cell ∼300 μm, resulting in a pronounced increase in membrane surface area (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Movie 2). The anterior face usually contained three large lobes with smaller papillary extensions. In addition, a network of capillaries was observed embedded immediately underneath the ruffled anterior membrane (Figs. 2D and 3B2; Supplementary Movie 3). In contrast to the posterior and anterior faces, the surface of the main body is relatively smooth, with an array of spherical structures just beneath the membrane (Fig. 2E).

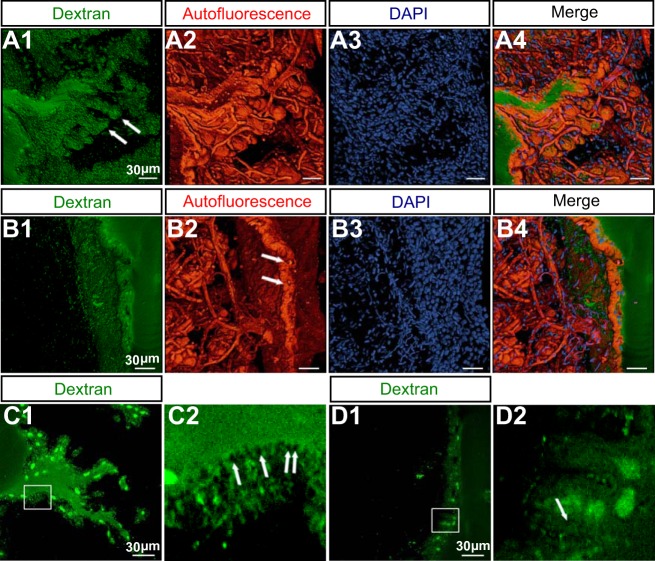

Fig. 3.

Fine structure of E. virescens electrocytes. A: 3D reconstruction of membrane papillae within a single invagination from serial confocal scans through a fixed 100-μm-thick section of EO tissue. A1 shows the intracellular structure identified by injection of Alexa Fluor 594 dextran (10,000 MW). Arrows point to the spines projecting from membrane papillae. In A2, tissue autofluorescence reveals that the spines shown in A1 are wrapped by capillaries. DAPI stains the multiple nuclei in A3. Channel images A1–A3 are opaquely superimposed in A4. B: 3D reconstruction of the junction between adjacent electrocytes from serial confocal scans through a 100-μm-thick section of fixed EO tissue. B1 shows the anterior face of the electrocyte injected with Alexa Fluor 594 dextran. Blood vessels occupy the space between adjacent electrocytes in B2, and arrows indicate the capillaries penetrating the anterior face. DAPI labels nuclei in B3. Channel images B1–B3 are merged in B4. C: the posterior-face membrane is mostly occupied by vesicles. C1 is an optical section from the serial confocal scans of the posterior face shown in A1. The region outlined in white in C1 is enlarged in C2, where arrows indicate vesicles. D: few vesicles are found on the surface of the anterior face. D1 is an optical section from the serial confocal scans of the anterior face shown in B1. The region outlined in white in D1 is enlarged in D2. Green circular structures in C and D are nuclei. Arrows indicate vesicles.

Electrocytes are multinucleated cells formed by the fusion of skeletal myocytes during development (Bennett 1970; Unguez and Zakon 1998a, 2002; Zakon and Unguez 1999), resulting in a syncytium with nuclei localized to the surface of the electrocyte (Machado et al. 1976). Our images of DAPI-stained nuclei colocalized with Alexa Fluor 594 within our 3D reconstruction confirm that the nuclei of E. virescens electroctyes are densely distributed in a thin layer near the membrane (Fig. 2F; see Fig. 3A for colocalization). The combination of whole cell 3D imaging and high-resolution imaging of smaller electrocyte sections in the present study allowed us to estimate the number of nuclei within a single electrocyte by two distinct methods, both of which indicated that each electrocyte has ∼30,000 nuclei.

The first method we used was to create an isosurface around the whole cell image of the electrocyte (Fig. 2A). This allowed us to measure the surface area of the entire electrocyte, which was 4.5 × 106 μm2. We then counted the number of nuclei per unit surface area in a single high-resolution image of the cell body and found that there were 220 nuclei per 2.8 × 104 μm2 of cell surface area. This method thereby yielded (4.5 × 106 μm2)(220 nuclei/2.8 × 104 μm2) = 35,000 nuclei in the electrocyte.

To validate the above estimation, we used an alternate approach to estimate the number of nuclei within an electrocyte by modeling the electrocyte with simple geometries, with the anterior end and cell body approximated as a hollow cylinder with a paraboloid scooped out at the anterior end, and the posterior end as a solid paraboloid. The anterior end had a cupped shape, with nuclei along the surface, so the surface area was approximated as a paraboloid with a measured radius of 365 μm and a depth of 144 μm, giving a surface area of 4.8 × 105 μm2. We then counted the number of nuclei in a single high-resolution image of the anterior region with 1.5 × 104 μm2 of surface area and found 170 nuclei, giving a total of (4.8 × 105 μm2)(170 nuclei/1.5 × 104 μm2) = 5.4 × 103 nuclei in the anterior end. The central compartment end was approximated as a hollow cylinder with a measured length of 1.0 × 103 μm and a measured diameter of 600 μm. Therefore, the total number of nuclei on the cell body would be (600 μm)π(1,000 μm)(220 nuclei/2.8 × 104 μm2) = 1.5 × 104 nuclei in the central compartment. For the posterior end, since the invaginations penetrate back to the cell body, resulting in nuclei being located throughout the posterior end, we modeled the posterior end as a solid paraboloid. The paraboloid had a measured length of 590 μm and a radius of 215 μm, giving a total volume of 8.6 × 107 μm3. We then measured the number of nuclei in a 7.0 × 106 μm3 image. To ensure that we only measured electrocyte nuclei, we only counted nuclei that were colocalized with Alexa Fluor 594. In the sample volume, we counted 1,000 nuclei. Extrapolated over the whole posterior end, there would therefore be (8.6 × 107 μm3)(1,000 nuclei/7.0 × 106 μm3) = 1.2 × 104 nuclei in the posterior region. Taken together, these quantities sum to 32,000 nuclei per electrocyte, which is in close concordance with our estimate based on the first method.

Fine Structure of the Electrocyte

We investigated the fine structure of the posterior and anterior faces by imaging 100-μm-thick serial sections of a paraformaldehyde-fixed EO sample that contained a single target electrocyte filled with Alexa Fluor 594 dextran. Electrocytes, vasculature, and pigment cells within the EO also emit a broad autofluorescence spectrum when excited by a 488-nm laser line. We took advantage of this autofluorescence to image tissue adjoining the Alexa Fluor 594 dextran-injected cell.

Our images of the posterior face showed that the surface of each invagination contained many small spine-like structures ∼50 μm in length. The spines terminate in an enlarged sphere ∼20 μm in diameter (Fig. 3A). Blood vessels occupy the space between electroctyes, with the majority penetrating into the invaginations of the posterior face, although a smaller number contact the anterior face (Fig. 3, A2 and B2, respectively). Capillaries occupy much of the space within each posterior-face invagination, and the spines within the invaginations are largely enveloped by these capillaries. The fine structure of the anterior face (Fig. 3B) is generally less complex than that of the posterior face, with the unique feature that capillaries appear to reside within enclosed, tubelike structures proximal to the anterior face membrane (Fig. 3B2). An additional and striking difference between the anterior and posterior faces is that the posterior-face membrane is densely occupied by vesicles, which are exceedingly less abundant on the anterior face (Fig. 3, C and D).

Subcellular Localization of Cholinergic Receptors, Ion Channels, and Ion Transporters

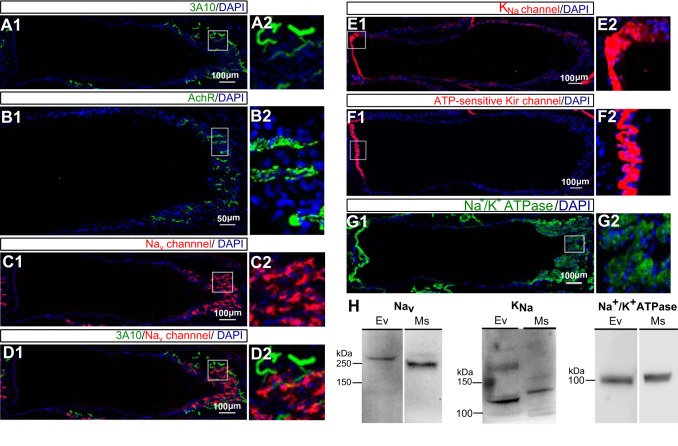

In gymnotiforms, electrocyte APs are controlled by a medullary pacemaker nucleus via spinal electromotor neurons that innervate each electrocyte (Fig. 1A). Labeling of spinal nerves with the antibody 3A10 against neurofilament-associated antigen (Unguez and Zakon 1998b) showed that only the posterior face is innervated and that the innervation occurs throughout the posterior face (Fig. 4A). We also found that acetylcholine receptors were clustered only on the posterior face (Fig. 4B). Given that the cholinergic synapses are restricted to the posterior membrane, we hypothesized that the other ion channels also would be localized on the posterior membrane.

Fig. 4.

Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry staining of acetylcholine receptors, ion channels, and Na+-K+-ATPases in E. virescens electrocytes. A–G: expression patterns of acetylcholine receptors, ion channels, and Na+-K+-ATPases. DAPI (blue) labels the electrocyte nuclei in A–G; the regions outlined in white in A1–G1 are enlarged in A2–G2. A: only the posterior face (right) is innervated by spinal electromotor neurons. The axons of innervating neurons are labeled with 3A10 (green). B: acetylcholine receptors (green) are clustered only on the posterior face (right). C: voltage-gated Na+ channels (red) are localized only on the posterior face (right). D: an electrocyte is co-labeled with 3A10 (green) and voltage-gated Na+ channels (red). E: Na+-activated K+ (KNa) channels (red) are only expressed on the anterior face (left). F; ATP-sensitive inward-rectifier K+ channels (red) are localized on the anterior face (left). G: Na+-K+-ATPases (green) are expressed on both anterior and posterior faces. H: Western blot analysis to confirm the specificity of rabbit polyclonal anti-Nav (left), rabbit polyclonal anti-kcnt1 (middle), and mouse monoclonal anti-α-subunit of Na+-K+-ATPase (right) in E. virescens EO and mouse brain. In EO, a band was labeled with anti-Nav at ∼250 kDa, which is slightly larger than that labeled in mouse brain (left). Anti-kcnt1 detected a band in EO at ∼130 kDa, which is slightly smaller than that detected in mouse brain (middle). A band at 100 kDa was detected with anti-α-subunit of Na+-K+-ATPase in both EO and mouse brain (right). Ev, E. virescens; Ms, mouse brain.

We labeled voltage-gated Na+ channels (Nav) with a pan-Nav antibody raised against an epitope identical in all isoforms of Nav1 and found that Nav channels were expressed only on the electrocyte's posterior face (Fig. 4C). To ensure these signals are not from the innervating axons, we co-stained Nav channels with 3A10 and found no colocalization between them (Fig. 4D). The expression pattern of acetylcholine receptors and Nav channels indicates that the posterior face is the only entrance site for Na+ influx and the site of AP initiation.

Based on electrophysiological and molecular evidence that electrocytes express inward-rectifier and KNa channels (Markham et al. 2013), we immunolabeled both channels and, to our surprise, found that both are localized only to the anterior face (Fig. 4, E and F). Immunolabeling of Na+-K+-ATPase α-subunits showed that these are found on both the anterior and posterior faces, another unusual arrangement given that the sources of Na+ influx are restricted to the posterior membrane (Fig. 4G).

Given the counterintuitive spatial separation of the Na+ channels, KNa channels, and Na+-K+-ATPases, we performed Western blot analyses to ensure that these antibodies indeed specifically labeled the proteins of interest. Western blot of E. virescens EO and mouse brain whole cell lysate labeled with polyclonal anti-Nav detected specific bands of ∼250 kDa (the predicted molecular mass of Nav channels) in both tissues (Fig. 4H). Similarly, polyclonal anti-kcnt1 (KNa) and monoclonal anti-Na+-K+-ATPase α-subunit labeled bands of ∼130 and 100 kDa, respectively, in both EO and mouse brain (Fig. 4H). These molecular masses correspond with the predicted molecular masses of KNa channels and Na+-K+-ATPase α-subunits.

Numerical Simulations of Electrocyte Function

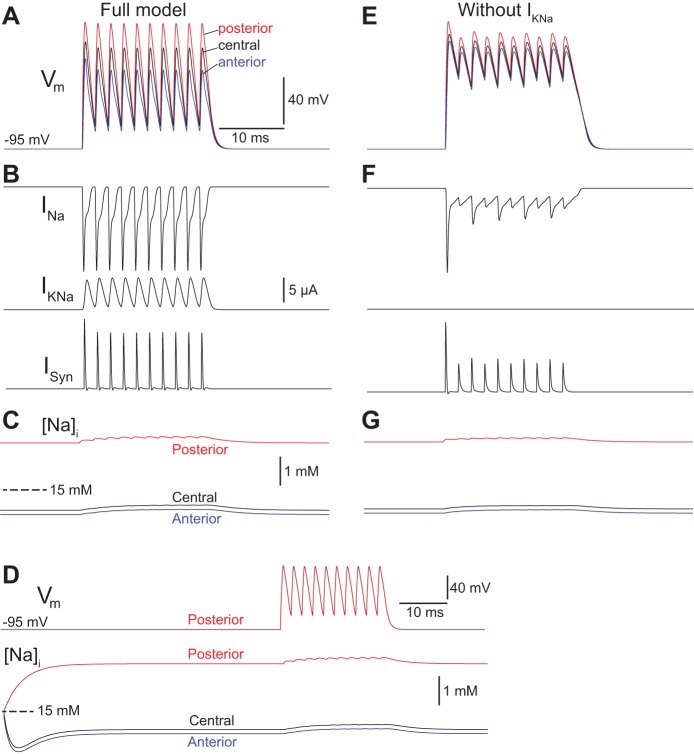

Given the unusually large separation of KNa channels from potential Na+ sources revealed by our imaging data, we used computational simulations of electrocyte action potentials and Na+ dynamics to test whether the high-frequency firing typical of E. virescens electrocytes could be reproduced in a model cell where the spatial arrangement of ion channels matched our imaging data. Our model cell had three compartments: an active posterior compartment, a passive central compartment, and an active anterior compartment. The passive properties of these compartments were guided by morphological measurements of their volumes and membrane areas. We estimated the coupling conductances between compartments on the basis of our measurements of the electrocyte's length and diameter.

The posterior compartment had linear leak current, synaptic current via cholinergic receptors, and voltage-gated Na+ current (IL, ISyn, and INa, respectively). The central compartment had only IL, and the anterior compartment had IL, inward-rectifier K+ current (IR), and KNa current (IKNa). Unlike previous simulations of IKNa where the Na+ sensitivity of the current arises from direct access to a localized persistent Na+ current (Brown et al. 2008; Markham et al. 2013), we modeled IKNa in this study such that its Na+ sensitivity was determined by the Na+ concentration in the bulk cytoplasm of the anterior compartment. Our model also simulated changes in intracellular Na+ in each compartment on the basis of Na+ influx resulting from a static Na+ leak, ISyn and INa in the posterior compartment, a fractional Na+ pumping rate in both the posterior and anterior compartments, and Na+ diffusion between all three compartments.

In the full model with all currents present according to the parameters in Table 1, the model cell maintained repetitive firing in response to 500-Hz synaptic stimulation (Fig. 5A). During these APs, INa reached peak currents of ∼15 μA, consistent with earlier experimental results (Lewis et al. 2014), and IKNa exhibited current magnitudes exceeding 5 μA (Fig. 5B), suggesting an important role in shaping the cell's firing pattern. Na+ concentrations in the three compartments did vary in response to Na+ influx, pumping, and diffusion, but only over a range of 1–2 mM (Fig. 5C). As a result, the fractional activation of IKNa due to Na+ concentrations in the anterior compartment remained fairly steady around 0.7 throughout the action potential train.

Fig. 5.

Computational simulations of electrocyte APs in a model electrocyte with (A–D) and without KNa channels (E–G). A: membrane potential (Vm) of the posterior (red), central (black), and anterior (blue) compartments of a model cell with KNa during a train of 10 APs elicited at 500 Hz by simulated synaptic conductances. B: time course of the Na+ current (INa), KNa current (IKNa), and synaptic current (ISyn) during the AP train shown in A. C: time course of internal Na+ concentrations ([Na+]i) in the posterior (red), central (black), and anterior (blue) compartments during the AP train shown in A. The different initial Na+ concentrations reflect the equilibrium of resting Na+ leak, pumping, and diffusion rates as shown in D. D: posterior Vm and time course of [Na+]i in the posterior (red), central (black), and anterior (blue) compartments during the same simulation shown in A, but on an expanded timescale that shows the initial changes in Na+ concentrations as the Na+ leak, pumping, and diffusion processes reach equilibrium. E: Vm of the posterior (red), central (black), and anterior (blue) compartments of a model cell without KNa during a train of 10 APs elicited at 500 Hz by simulated synaptic conductances. F: time course of INa, IKNa, and ISyn during the AP train shown in E. G: time course of [Na+]i in the posterior (red), central (black), and anterior (blue) compartments during the AP train shown in E. The different initial Na+ concentrations reflect the equilibrium of resting Na+ leak, pumping, and diffusion rates as shown in D.

To evaluate whether IKNa is a necessary component of AP repolarization in the model cell, we made a model cell with all of the same parameters as in Fig. 5, A–C, but set the conductance for IKNa to zero. This model cell could not maintain repetitive firing at 500 Hz (Fig. 5, D and E) and instead remained in a state of depolarized oscillation. These results provide evidence that IKNa in our model cell is necessary for AP repolarization and plays a role in AP termination even when the KNa channels are at a great distance from transient Na+ sources.

DISCUSSION

The most striking finding from this study is the extreme compartmentalization of ion channels and ion transporters across vast distances in E. virescens electrocytes. The KNa channels that repolarize the electrocyte AP and a substantial portion of the Na+-K+-ATPases responsible for removing Na+ after each AP are separated by more than a millimeter from the only identified sources of Na+ influx.

The presence of KNa channels at such a great distance from Na+ sources raises the important question of how these channels are activated during the AP. In previous work with KNa channels from other taxa, channel activation required intracellular Na+ concentrations ([Na+]i) that far exceed those normally found in bulk cytoplasm (Dryer et al. 1989; Kameyama et al. 1984; Yuan et al. 2003). In mammalian neurons, KNa channels are clustered within just a few micrometers of Na+ channels in microdomains that allow localized elevation of Na+ concentrations sufficient to activate KNa channels without changing [Na+]i in the bulk cytoplasm (Budelli et al. 2009; Hage and Salkoff 2012). However, we show in the present study that Na+ and KNa channels are separated by great distances in E. virescens electrocytes, suggesting that KNa channels in E. virescens electrocytes do not require proximal sources of Na+ influx.

One hypothesis as to how KNa channels are activated in electroctyes is that electrocytes experience a significant increase in [Na+]i during each AP or during sustained high-frequency firing, a distinct possibility given the magnitude of INa during the AP. We found a high density of Na+-K+-ATPases on the anterior face, consistent with earlier biochemical data (Denizot 1982), suggesting that Na+ influx from the posterior face ultimately increases [Na+]i in the anterior region. Our computational simulations suggest that only small changes in [Na+]i occur during high-frequency firing in E. virescens electrocytes. This suggests instead a second hypothesis, that the electrocyte's KNa channels are more sensitive to [Na+]i than most other KNa isoforms identified to date. Indeed, our simulated IKNa was based on Na+-dependent rate constants that created partial activation with Na+ concentrations of ∼15 mM. Multiple factors determine the Na+ sensitivity of KNa channels. Single amino-acid substitutions can shift the Na+ sensitivity of KNa channels over a range of 200 mM (Zhang et al. 2010). Given the elevated rates of evolution for other ion channels in gymnotiform electrocytes (Zakon et al. 2006, 2008), it seems possible that KNa channels also could have undergone evolutionary changes that would enhance Na+ sensitivity. Additionally, intracellular factors such as NAD+ can modulate the Na+ sensitivity of KNa channels such that the EC50 is ∼17 mM (Tamsett et al. 2009). It is possible that such molecular evolution or functional modulation in E. virescens KNa channels could allow their activation at Na+ concentrations in the 15 mM range. These possibilities can only be directly addressed through cloning and heterologous expression of E. virescens electrocyte KNa channels.

Our numerical simulations in the present study suggest that the electrocyte KNa channels remain in a state of partial activation during repetitive firing, rather than responding to transient increases in [Na+]i as concluded in earlier work (Markham et al. 2013). If electrocyte KNa channels indeed are maintaining a steady level of activation during normal repetitive firing, this raises the question of what function the channels' Na+ sensitivity serves in this system. Further experimental investigation and computational simulations of Na+ dynamics in the electrocyte are needed to clarify the functional significance of KNa channels' Na+ sensitivity in E. virescens electrocytes.

Additionally, the finding that ion channels are expressed on both the anterior and posterior electrocyte faces contradicts a long-standing assumption, originating with some of the earliest electrophysiological studies of E. virescens electrocytes, that only the innervated face is active (Bennett 1961, 1971) and that all ion channels which produce the AP should therefore be localized to the posterior face (e.g., Assad et al. 1998). The presence of KNa and inward-rectifier K+ channels on the electrocyte anterior membrane indicates that both the posterior and anterior faces of the electrocyte are involved in AP production.

A second important finding here is the sheer magnitude and complexity of the electrocyte's morphology. Our two-photon live-cell and fixed-tissue imaging of E. virescens electroctyes extends earlier electron microscopy studies (Schwartz et al. 1975) that first reported the 2D morphological polarization of these cells. Our 3D reconstructions of E. virescens electrocytes also show that they are extremely large multinucleated cells with striking differences in the ultrastructural features of the posterior and anterior faces. Because of the electrocytes' large diameter, the laser scanning confocal microscope could not resolve the submicrometer detail of the medial region of the cells, preventing us from obtaining a detailed 3D reconstruction of this region of the electrocyte. However, we observed a discrete lower boundary of the fluorescence on the medial side of the electrocyte at a depth of 600 μm, suggesting that the cell is 600 μm across on both the lateral-medial axis and the ventral-dorsal axis.

The deep invaginations of the posterior region create a significant expansion of membrane surface area in a comparatively small volume. This membrane area is almost entirely occupied by vascularization on the extracellular surface and by vesicles on the intracellular surface. It is perhaps possible that some of the fibrillary structures we identified as capillaries were instead portions of the innervating spinal nerves, but this is unlikely because blood vessel walls, unlike nerve, contain autofluorescent elastin and collagen (Deyl et al. 1980), and the narrowest vessels we observed were ∼3 μm in diameter with a hollow center. Additionally, the vessels branched from a large central hollow tube that was almost 20 μm in diameter (Fig. 3B2), making it extremely unlikely that these are axons. The dense vascularization of the posterior face is likely necessary to provide efficient nutrient supply and waste removal, consistent with reports that high concentrations of mitochondria are present in the posterior region (Schwartz et al. 1975). We hypothesize that the densely packed vesicles on the posterior membrane are associated with constitutive trafficking of Na+ channels and Na+-K+-ATPases. In a related electric fish, Na+ channels are constitutively cycled into and out of the electrocyte membrane, and upregulation of channel exocytosis by hormonal factors can increase INa magnitude by more than 50% within minutes (Markham et al. 2009), as has been reported for E. virescens (Markham et al. 2013).

The proliferation of membrane surface area on the posterior face also provides a substrate for high numbers of Na+-K+-ATPases, which are expressed throughout the posterior membrane. Active transport of Na+ by the Na+-K+-ATPase occurs at the rate of ∼103 ions per second (Holmgren et al. 2000), whereas selective ion channels pass 107 to 108 ions per second (Morais-Cabral et al. 2001). In E. virescens electrocytes, ∼6 × 1010 Na+ ions enter the electrocyte with each AP (Lewis et al. 2014) with only 1 ms between APs at 500 Hz. Accordingly, efficient removal of Na+ during the brief interspike interval would depend on extremely high densities of Na+-K+-ATPases. The extensive posterior-face membrane area also would increase membrane capacitance and decrease resistance (assuming a constant membrane resistivity). This combination of high capacitance and low resistance would increase current flow during the AP (Schwartz et al. 1975), and the tuning of resistance relative to capacitance would determine the membrane time constant potentially influencing AP duration (Mills et al. 1992).

The complex organization of the posterior face in E. virescens electrocytes contrasts sharply with the morphology of the anterior face, which is relatively featureless with sparse vascularization and few detectable vesicles. Within the relatively simple organization of the anterior face, KNa channels, inward-rectifier K+ channels, and Na+-K+-ATPases were densely and apparently evenly distributed across the membrane surface. The paucity of anterior-face exocytotic vesicles suggests that KNa channels are perhaps not cycled or trafficked in the same manner as Na+ channels on the posterior face. These results are consistent with our earlier studies of the hormonal regulation of ionic currents in E. virescens electrocytes. Application of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) increased the magnitudes of INa and IKNa. The increase in INa was a direct effect of ACTH application regulating vesicular trafficking of Na+ channels, but the increased conductance of KNa channels was found to be a secondary effect of the hormone-induced increase in INa magnitude (Markham et al. 2013).

The bioelectrical properties of all excitable cells are determined by their morphology and the subcellular localization of ion channels. Electrocyte morphology is an important determinant of species- and individual-specific EOD waveforms (Bass 1986; Gallant et al. 2011; Hopkins et al. 1990; Mills et al. 1992), and the subcellular distributions and densities of ionic currents also help determine EOD waveform (Ferrari and Zakon 1993; Markham and Zakon 2014; Shenkel and Sigworth 1991). Some of the ion channels, ionotropic receptors, and ion transporters responsible for electrocytes' biophysical properties have been localized in other gymnotiform and mormyriform electric fish (Cuellar et al. 2006; Gallant et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2007). The present work is, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive presentation of detailed electrocyte morphology together with subcellular localization of all ionic mechanisms responsible for an electrocyte's electrical excitability. It is of course possible that additional key membrane proteins are present but not yet detected. Of particular concern is the possibility that a second undetected isoform of KNa channel is expressed in proximity to the voltage-gated Na+ channels. We believe this is unlikely, because an earlier study detected only a single isoform of KNa channel in E. virescens electrocytes by RT-PCR, the KCNT1/Slack isoform (Markham et al. 2013), supporting the conclusion that our immunolabeling in the present study detected all KNa channels expressed in electrocytes. Moreover, the present immunolabeling study detected ion channels corresponding to all known ionic currents in E. virescens electrocytes, and these ionic currents are sufficient to reproduce completely the electrical behavior of these cells as shown by our computational simulations in this study and in earlier work (Markham et al. 2013).

Ultimately, the energetic demands of electrocyte APs and the ability to maintain firing rates exceeding 500 Hz throughout the animal's life span stem from the spatiotemporal dynamics of Na+ entry during the AP and the subsequent Na+ removal within a millisecond by the Na+-K+-ATPases. For these peripheral excitable cells, the metabolic cost of AP generation is likely a major force governing their biophysical properties, as is the case for central neurons (Hasenstaub et al. 2010). Future studies on the temporal and spatial dynamics of Na+ entry and removal in electrocytes will be necessary for understanding how the ion channels and Na+-K+-ATPases coordinate to maintain high firing rates while managing the extremely large inward Na+ currents. Furthermore, additional exploration of the interaction between electrocyte Na+ channels and KNa channels will likely lead to new insights on the many important roles that KNa channels play in excitable cell physiology (Bhattacharjee and Kaczmarek 2005).

GRANTS

Financial support and equipment were provided by National Science Foundation Grants IOS1257580 and IOS1350753 (to M. R. Markham). This research was also supported in part by a grant from the Research Council of the University of Oklahoma Norman Campus.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.B. and M.R.M. conception and design of research; Y.B., B.E.S., and M.R.M. performed experiments; Y.B., B.E.S., and M.R.M. analyzed data; Y.B. and M.R.M. interpreted results of experiments; Y.B., B.E.S., and M.R.M. prepared figures; Y.B., B.E.S., and M.R.M. drafted manuscript; Y.B., B.E.S., and M.R.M. edited and revised manuscript; Y.B., B.E.S., and M.R.M. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rosalie Maltby and Emily Ahadizadeh for technical assistance and fish care. We are grateful to Ari Berkowitz for suggestions on an earlier version of this manuscript. We thank Chris Lemon and Dylan Barnes for providing mice for the Western blot analyses, Rosemary Knapp for use of the cryostat, and J. P. Masly for imaging assistance.

REFERENCES

- Assad C, Rasnow B, Stoddard PK, Bower JM. The electric organ discharges of the gymnotiform fishes: II. Eigenmannia. J Comp Physiol A 183: 419–432, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21: 1133–1145, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH. Species differences in electric organs of mormyrids: substrates for species-typical electric organ discharge waveforms. J Comp Neurol 244: 313–330, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 451–465, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MV. Comparative physiology: electric organs. Annu Rev Physiol 32: 471–528, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MV. Electric organs. In: Fish Physiology, edited by Hoar WS, Randall DJ. New York: Academic, 1971, p. 347–491. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MV. Modes of operation of electric organs. Ann NY Acad Sci 94: 458–509, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A, Kaczmarek LK. For K+ channels, Na+ is the new Ca2+. Trends Neurosci 28: 422–428, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Kronengold J, Gazula VR, Spilianakis CG, Flavell RA, von Hehn CA, Bhattacharjee A, Kaczmarek LK. Amino-termini isoforms of the Slack K+ channel, regulated by alternative promoters, differentially modulate rhythmic firing and adaptation. J Physiol 586: 5161–5179, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budelli G, Hage TA, Wei A, Rojas P, Jong YJ, O'Malley K, Salkoff L. Na+-activated K+ channels express a large delayed outward current in neurons during normal physiology. Nat Neurosci 12: 745–750, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Bean BP. Sodium entry during action potentials of mammalian neurons: incomplete inactivation and reduced metabolic efficiency in fast-spiking neurons. Neuron 64: 898–909, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar H, Kim JA, Unguez GA. Evidence of posttranscriptional regulation in the maintenance of a partial muscle phenotype by electrogenic cells of S. macrurus. FASEB J 20: 2540, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denizot JP. The cytochemical demonstration of NaK dependent adenosine triphosphatase at electrocyte level in Eigenmannia virescens (Gymnotidae). Histochemistry 74: 213–221, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyl Z, Macek K, Adam M. Studies on the chemical nature of elastin fluorescence. Biochim Biophys Acta 625: 248–254, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE, Fujii JT, Martin AR. A Na+-activated K+ current in cultured brain stem neurones from chicks. J Physiol 410: 283–296, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari MB, Zakon HH. Conductances contributing to the action potential of Sternopygus electrocytes. J Comp Physiol A 173: 281–292, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant JR, Arnegard ME, Sullivan JP, Carlson BA, Hopkins CD. Signal variation and its morphological correlates in Paramormyrops kingsleyae provide insight into the evolution of electrogenic signal diversity in mormyrid electric fish. J Comp Physiol A 197: 799–817, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham BP, Redman SJ. Dynamic behavior of a model of the muscle stretch reflex. Neural Netw 6: 947–962, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hage TA, Salkoff L. Sodium-activated potassium channels are functionally coupled to persistent sodium currents. J Neurosci 32: 2714–2721, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenstaub A, Otte S, Callaway E, Sejnowski TJ. Metabolic cost as a unifying principle governing neuronal biophysics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 12329–12334, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren M, Wagg J, Bezanilla F, Rakowski RF, De Weer P, Gadsby DC. Three distinct and sequential steps in the release of sodium ions by the Na+/K+-ATPase. Nature 403: 898–901, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins CD. Electric communication: functions in the social behavior of Eigenmannia virescens. Behaviour 50: 270–305, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins CD, Comfort NC, Bastian J, Bass AH. Functional analysis of sexual dimorphism in an electric fish, Hypopomus pinnicaudatus, order Gymnotiformes. Brain Behav Evol 35: 350–367, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth C, Gleeson P, Attwell D. Updated energy budgets for neural computation in the neocortex and cerebellum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 1222–1232, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama M, Kakei M, Sato R, Shibasaki T, Matsuda H, Irisawa H. Intracellular Na+ activates a K+ channel in mammalian cardiac cells. Nature 309: 354–356, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovitz RM, Takeyasu K, Fambrough DM. Molecular characterization and expression of the (Na+ + K+)-ATPase alpha-subunit in Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J 8: 193–202, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JE, Gilmour KM, Moorhead MJ, Perry SF, Markham MR. Action potential energetics at the organismal level reveal a trade-off in efficiency at high firing rates. J Neurosci 34: 197–201, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wu MM, Zakon HH. Individual variation and hormonal modulation of a sodium channel beta subunit in the electric organ correlate with variation in a social signal. Dev Neurobiol 67: 1289–1304, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado RD, de Souza W, Pereira GC, and de Oliveira Castro G. On the fine structure of the electrocyte of Electrophorus electricus L. Cell Tissue Res 174: 355–366, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham MR, Kaczmarek LK, Zakon HH. A sodium-activated potassium channel supports high-frequency firing and reduces energetic costs during rapid modulations of action potential amplitude. J Neurophysiol 109: 1713–1723, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham MR, McAnelly ML, Stoddard PK, Zakon HH. Circadian and social cues regulate ion channel trafficking. PLoS Biol 7: e1000203, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham MR, Zakon HH. Ionic mechanisms of microsecond-scale spike timing in single cells. J Neurosci 34: 6668–6678, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A, Zakon HH, Marchaterre MA, Bass AH. Electric organ morphology of Sternopygus macrurus, a wave-type, weakly electric fish with a sexually dimorphic EOD. J Neurobiol 23: 920–932, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-Cabral JH, Zhou Y, MacKinnon R. Energetic optimization of ion conduction rate by the K+ selectivity filter. Nature 414: 37–42, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niven JE, Laughlin SB. Energy limitation as a selective pressure on the evolution of sensory systems. J Exp Biol 211: 1792–1804, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon EE, Parisi A, Krahe R, Chapman LJ. Energetic constraints on electric signalling in wave-type weakly electric fishes. J Exp Biol 214: 4141–4150, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheich H. Neural basis of communication in the high frequency electric fish, Eigenmannia virescens (jamming avoidance response). J Comp Physiol A 113: 181–206, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz IR, Pappas GD, Bennett MV. The fine structure of electrocytes in weakly electric teleosts. J Neurocytol 4: 87–114, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenkel S, Sigworth FJ. Patch recordings from the electrocytes of Electrophorus electricus. Na currents and PNa/PK variability. J Gen Physiol 97: 1013–1041, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamsett TJ, Picchione KE, Bhattacharjee A. NAD+ activates KNa channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci 29: 5127–5134, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzartos SJ, Rand DE, Einarson BL, Lindstrom JM. Mapping of surface structures of electrophorus acetylcholine receptor using monoclonal antibodies. J Biol Chem 256: 8635–8645, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unguez GA, Zakon HH. Phenotypic conversion of distinct muscle fiber populations to electrocytes in a weakly electric fish. J Comp Neurol 399: 20–34, 1998a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unguez GA, Zakon HH. Reexpression of myogenic proteins in mature electric organ after removal of neural input. J Neurosci 18: 9924–9935, 1998b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unguez GA, Zakon HH. Skeletal muscle transformation into electric organ in S. macrurus depends on innervation. J Neurobiol 53: 391–402, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan A, Santi CM, Wei A, Wang ZW, Pollak K, Nonet M, Kaczmarek L, Crowder CM, Salkoff L. The sodium-activated potassium channel is encoded by a member of the Slo gene family. Neuron 37: 765–773, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakon HH, Lu Y, Zwickl DJ, Hillis DM. Sodium channel genes and the evolution of diversity in communication signals of electric fishes: convergent molecular evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3675–3680, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakon HH, Unguez GA. Development and regeneration of the electric organ. J Exp Biol 202: 1427–1434, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakon HH, Zwickl DJ, Lu Y, Hillis DM. Molecular evolution of communication signals in electric fish. J Exp Biol 211: 1814–1818, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, Tang QY, Noskov S, Logothetis DE. The RCK2 domain uses a coordination site present in Kir channels to confer sodium sensitivity to Slo2.2 channels. J Neurosci 30: 7554–7562, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.