Abstract

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are erythematous skin lesions with blister formation accompanied by mucosal involvement. These conditions are considered to be life-threatening illnesses. Understanding the clinical presentation, risk factors, treatment options and results will be advantageous for physicians in the management of patients in the future. The aim of the present study was to review and analyze the clinical manifestations, drug implications, treatment and outcome of patients with SJS and/or TEN who had been hospitalized in a tertiary care center. All hospitalized patients with SJS and/or TEN during a 5-year period were retrospectively reviewed. The clinical severity was graded according to the score of toxic epidermal necrolysis (SCORTEN) scale. Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, possible precipitating factors, management and outcome data were collected for analysis. A total of 43 patients (mean age, 49.5 years) were hospitalized and classified into the SJS group (55.8%), SJS/TEN overlap group (20.9%) and TEN group (23.3%). The majority of the patients (90.7%) had mucocutaneous eruptions associated with oral drug administration. Allopurinol, anticonvulsants and antibiotics were the most common causative agents for the mucocutaneous eruption. Twenty-eight patients (65.1%) were treated with corticosteroids. The mortality rate was 6.9%. Comparison between the survival group and the non-survival group revealed that patient age >70 years (P=0.014) and body surface area involvement >20% (P<0.01) were the significant factors associated with mortality. The use of systemic steroids was higher in the survival group in comparison with the non-survival group (65.1 vs. 0%, respectively; P=0.014). The mucocutaneous eruptions in SJS and TEN are mostly caused by medication. With early recognition and treatment, the mortality rate in this study was lower than that in previous reports. Patient age and the area of mucocutaneous involvement were significant factors associated with mortality.

Keywords: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, drug reaction

Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have shared characteristics of erythematous cutaneous reaction with blister formation accompanied by mucosal involvement. Patients with SJS have desquamation of the skin affecting <10% of their body surface area whereas patients with TEN have >30% body surface area involvement. Patients with skin lesions affecting between 10 and 30% of their body surface area are considered to have SJS/TEN overlap (1). These epidermal detachments are considered life-threatening (2) and are most frequently manifested by adverse drug reaction. In addition to occurring as a reaction to drugs, these skin eruptions are also associated with underlying infectious diseases, and include the cutaneous manifestations of disseminated candidiasis (3,4), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (5), Chlamydia pneumoniae (6), cytomegalovirus infection (7) and human immunodeficiency virus (8,9). The mortality rates of these skin eruptions have been reported to range from 16 to 25% (10–13). Treatment is based on symptoms and supportive fluid and electrolyte replacement. Dermal coverage to prevent secondary infection and the loss of fluid are also crucial aspects of treatment. Several immunomodulative therapies have been suggested to treat SJS and/or TEN, particularly glucocorticoids and immunoglobulin. Prognostic factors and scoring systems have been used to define the mortality risk in these patients, including the severity-of-illness score of toxic epidermal necrolysis (SCORTEN) scale (14).

In this study, the clinical manifestations, drug implications, treatment and outcomes of patients with SJS and/or TEN who had been hospitalized over the past 5 years in a tertiary referral care center were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed.

Patients and methods

Patient data

The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the King Chulalongkorn University Hospital (Bangkok, Thailand) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors retrospectively reviewed all patients who had been hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of severe skin eruption during the previous 5 years. The medical records were evaluated and classified according to patient history, pre-existing conditions, suspected causes, degree of skin and mucosal involvement, diagnosis, treatment and outcome. The patients were divided into three groups, namely SJS, SJS/TEN overlap and TEN, based on the percentage of body surface area involvement. These three groups of patients were analyzed to determine the difference in clinical manifestations, underlying diseases, clinical course, treatment and mortality.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated. Differences between groups were compared by unpaired t-testing and one way analysis of variance. The level of significance was set at 5%. All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient clinical data

During the 5-year period, 43 of the 47 patients that were hospitalized for SJS, TEN and SJS/TEN overlap had complete medical records to review. The mean age of the subjects was 49.5 (range, 20–85) years. Twenty-four patients (55.8%) were diagnosed with SJS, 9 (20.9%) were classified with SJS/TEN overlap and 10 (23.3%) were categorized as having TEN. The demographic data and underlying diseases are shown in Table I. Mucosal membrane involvement was observed in the oral cavity in 97.7% of cases and eye involvement was observed in 88.4% of the study population. The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table II.

Table I.

Demographic and baseline clinical data of the patients.

| Baseline and clinical variables | SJS | SJS/TEN overlap | TEN | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, n (%) | 24 (55.8) | 9 (20.9) | 10 (23.3) | 43 |

| Mean age (range), years | 46.5 (20–77) | 54.4 (25–85) | 52.4 (21.84) | 49.5 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 13 (54.2) | 7 (77.8) | 5 (50.0) | 25 |

| Female | 11 (45.8) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (50.0) | 18 |

| Underlying disease (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 8.3 | – | 30.0 | 11.6 |

| Hypertension | 16.7 | 33.3 | 40.0 | 25.6 |

| Gout | 12.5 | – | 30.0 | 13.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12.5 | 11.1 | 20.0 | 13.9 |

| Epilepsy | 12.5 | – | – | 7.0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4.2 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 7.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4.2 | 22.2 | 10.0 | 9.3 |

| HIV infection | 33.3 | 22.2 | 60.0 | 37.2 |

| Tuberculosis | 4.2 | 11.1 | 20.0 | 9.3 |

| Viral hepatitis B/C | – | – | 20.0 | 4.7 |

| Other | 8.3 | – | – | 11.6 |

| Alcohol drinking | 12.5 | 22.2 | 10.0 | 14.0 |

| History of malignancy | 12.5 | – | 20.0 | 11.6 |

| History of allergy | 12.5 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 11.6 |

SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Table II.

Clinical presentation and manifestation of the patients.

| Variables | SJS | SJS/TEN overlap | TEN | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, n (%) | 24 (55.8) | 9 (20.9) | 10 (23.3) | 43 |

| Chief complaint (%) | ||||

| Rash | 37.5 | 66.7 | 80.0 | 53.5 |

| Fever | 29.1 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 20.9 |

| Oral ulcer | 16.7 | 11.1 | – | 11.6 |

| Edema | 8.3 | – | 10.0 | 7.0 |

| Eye symptom | 4.2 | 11.1 | – | 4.7 |

| Myalgia | 4.2 | – | – | 2.3 |

| Duration prior to admission (days) | 2.6 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 3.6 |

| Clinical manifestation (%) | ||||

| Oral mucosa involvement | 100 | 100 | 90.0 | 97.7 |

| Eye involvement | 83.3 | 88.9 | 100 | 88.4 |

| Genital involvement | 41.7 | 55.6 | 90.0 | 55.8 |

| Hepatitis | 41.7 | 66.7 | 50.0 | 48.8 |

| Microscopic hematuria | 20.1 | 11.1 | 40.0 | 23.2 |

SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

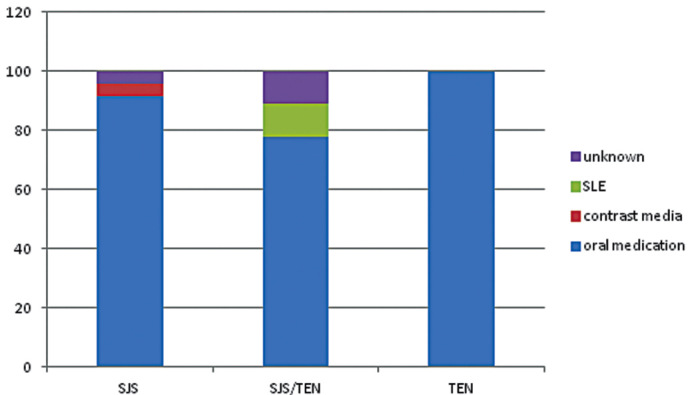

Causes of SJS, TEN and SJS/TEN

In 90.7% of patients, the mucocutaneous eruption was associated with oral drug administration and 2.3% of patients developed the lesions following treatment with contrast media. These mucocutaneous eruptions were considered to be associated with underlying disease, such as the cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus, in 2.3% of cases, as shown in Fig. 1. Allopurinol was the most common single drug causing the eruption (25.6%). The other medications associated with these conditions were anticonvulsants (23.1%) and antibiotics (23.1%). The duration of medication intake prior to the skin eruption ranged from 1 to 60 days (mean, 14.9 days).

Figure 1.

Causes of SJS, SJS/TEN overlap and TEN. JSJ, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

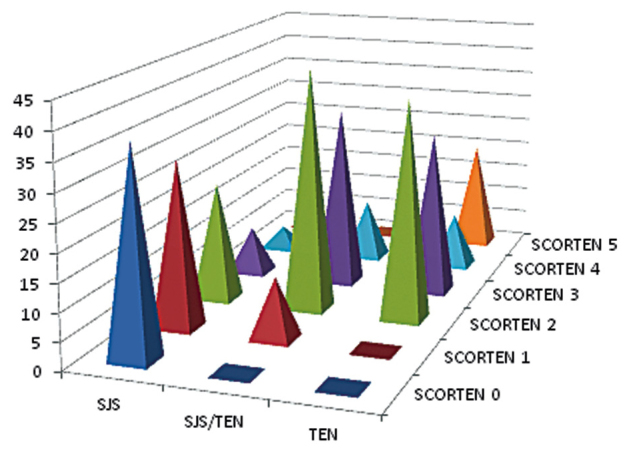

Disease severity

The SCORTEN scoring system was used to grade the severity of these diseases. The majority of the patients in the SJS (67.9%) group had a score of 0 or 1 while the majority of the SJS/TEN overlap (44.4%) and TEN (40%) groups had a score of 2. In the TEN group, 20% of the patients had a score of 5 as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Severity of disease classified by the SCORTEN scale in patients with SJS, SJS/TEN overlap and TEN. SCORTEN, score of toxic epidermal necrolysis; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Treatment

A total of 28 patients (65.1%) were treated with corticosteroids, as shown in Table III. Intravenous dexamethasone was the most common agent used. None of the patients received intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. Antibiotics were used in 60% of patients with TEN.

Table III.

Treatment regimens of the patients.

| Treatment | SJS | SJS/TEN overlap | TEN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total steroid use, n (%) | 14 (58.3) | 8 (88.8) | 6 (60) |

| Dexamethasone IV (%) | 42.8 | 37.5 | 66.7 |

| Mean dose (range), mg/day | 14.2 (8–20) | 20.6 (8–30) | 20 (8–40) |

| Prednisolone oral (%) | 57.2 | 50.0 | 33.3 |

| Mean dose (range), mg/day | 34.5 (20–60) | 57 (50–60) | 45 (30–60) |

| Total steroid duration (range), days | 6.3 (3–8) | 5.7 (1–7) | 6.3 (3–10) |

| Antibiotics use (%) | 29.1 | 22.2 | 60.0 |

| Fluid resuscitation in first 24 h (range), ml | 3,081.2 (500–6,500) | 3,361.1 (1,200–4,850) | 3,973.0 (2,870–5,350) |

| LOS (days) | 9.7 (2–24) | 11.8 (2–41) | 15.9 (2–52) |

SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; IV, intravenous; LOS, length of hospital stay.

Survival

Three patients in the TEN group succumbed while there was no mortality in the SJS and SJS/TEN overlap groups. The causes of mortality were septicemia in 2 cases and arrhythmia related to hyperkalemia in 1 case. Comparison between the survival group and the non-survival group revealed that patient age >70 years of age (P=0.014) and body surface area involvement >20% (P<0.01) were significant factors associated with mortality. The use of systemic steroids was higher in the survival group in comparison with the non-survival group (65.1 vs. 0%, respectively; P=0.014). Table IV shows the comparison analysis of the clinical characteristics between the survival and non-survival groups.

Table IV.

Results of univariate analysis of the clinical characteristics of the survival and non-survival groups.

| Variables | Survival group (%) | Non-survival group (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >70 years | 12.5 | 66.7 | 0.014 |

| Male gender | 55 | 100 | 0.128 |

| Eye involvement | 87.5 | 100 | 0.515 |

| Oral mucosa involvement | 97.5 | 100 | 0.782 |

| Genital involvement | 52.5 | 100 | 0.110 |

| Involvement of 3 mucosal areas | 42.5 | 100 | 0.054 |

| Renal involvement | 22.5 | 33.3 | 0.668 |

| Liver involvement | 50.0 | 33.3 | 0.578 |

| Duration prior to admission >72 h | 30.0 | 33.3 | 0.903 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 | 33.3 | 0.224 |

| Hypertension | 25 | 33.3 | 0.750 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12.5 | 33.3 | 0.315 |

| HIV positive | 30.0 | 33.3 | 0.903 |

| Malignancy | 10 | 33.3 | 0.224 |

| Gout | 12.5 | 33.3 | 0.315 |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | 35 | 66.7 | 0.274 |

| BUN >20 mg/dl | 37.5 | 66.7 | 0.319 |

| Serum bicarbonate <20 mEq/l | 27.5 | 66.7 | 0.154 |

| WBC >10,000 | 15 | 0 | 0.470 |

| BSA involvement >20% | 22.5 | 100 | 0.004 |

| Steroid treatment | 65.1 | 0 | 0.014 |

| Antibiotics use | 30 | 100 | 0.014 |

| Fluid in 24 h >2,500 ml | 70 | 100 | 0.206 |

| Infection | 30 | 100 | 0.014 |

| SCORTEN >2 | 27.5 | 66.7 | 0.154 |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; WBC, white blood cell count; BSA, body surface area, SCORTEN, score of toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Discussion

SJS, SJS/TEN overlap and TEN are rare but life-threatening conditions. It is important to recognize the clinical characteristics of the mucocutaneous eruption at early stage due to the high mortality rate, which ranges from 16 to 25% (1,10–12). The most frequent cause of these conditions is medication (15,16). The most common precipitating drug in this study was allopurinol. Anticonvulsants and antibiotics were found to be the second common causative agents in the present study, despite these two groups of medication being reported as the most frequent etiology in a previous study (17). The difference between these results could be explained by the common medications previously reported as having cutaneous adverse reactions now being avoided. With advancements in the identification of specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles that are associated with drug reactions, screening to identify patients at risk for drug reaction is becoming a part of standard clinical practice in certain academic institutions (18–21). This could be one of the reasons why the incidence of drug reactions toward commonly known medications appears to have declined.

The use of systemic corticosteroid treatment in patients with SJS/TEN is controversial, with concerns regarding an increased rate of infections, the masking of septicemia, and delay of epithelialization (22). By contrast, the benefits of immunosuppressants (including corticosteroids) have been reported as preventing ocular complications (23–26). In the present study, 65% of patients received systemic steroid treatment (range, 1–10 days). Notably, there was no mortality in patients treated with systemic steroids. By comparison, 3 cases of mortality were patients who did not receive steroid treatment. The results of the present study suggest the beneficial effect of systemic corticosteroid use in selected groups of SJS and/or TEN patients.

The SCORTEN scoring system has been used to define the severity of the disease and predict mortality for more than a decade. The results of the present study revealed a lower number of cases of mortality than predicted by SCORTEN score (14). There was no significant difference in SCORTEN score between survival and non-survival groups. This finding emphasizes the limitation of the SCORTEN as previously mentioned in certain review articles (27–29).

The mortality rate in the presented study was 6.9%, which was lower than the rates in previous studies (1,10–12). This could be the result of early diagnosis, the immediate discontinuation of causative medication, supportive medical care and immunosuppressive treatment. The finding in the present study concerning corticosteroid treatment is similar to that of the EuroSCAR-and RegiSCAR studies (13,30), which suggested the beneficial use of corticosteroid in selected subgroups of patients with SJS and/or TEN. To confirm this finding, a future prospective controlled study should be undertaken to evaluate the benefit of corticosteroid treatment in SJS/TEN.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, in terms of the small size of the study population selected from a major tertiary care center. Secondly, the study was designed to include only hospitalized patients. This may not provide the full evaluation in both quality and quantity of management in general, since the majority of the patients with mild forms of disease are treated in primary local hospitals. Thirdly, genetic data was not collected. With the advance and availability of genetic testing, genetic screening may be warranted to assist in the selection of treatment options and prevention. Lastly, this observational study may suggest the beneficial effect of steroids in the treatment of patients with SJS/TEN. However, a further double-blinded placebo control study is required to confirm this suggestion.

The severe forms of mucocutaneous eruptions, SJS and/or TEN, are mostly associated with adverse drug reactions. With early recognition and selected treatments, the mortality rate could be reduced. Improved understanding of clinical presentation and risk factors should help physicians to improve the care of high-risk individuals at an earlier stage. Patient age and the area of mucocutaneous involvement have been identified as significant factors associated with mortality.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Stephen Pinder for proofreading this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mockenhaupt M. The current understanding of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7:803–813. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerull R, Nelle M, Schaible T. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: A review. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1521–1532. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821201ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mays SR, Bogle MA, Bodey GP. Cutaneous fungal infections in the oncology patient: Recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:31–43. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodey GP. Dermatologic manifestations of infections in neutropenic patients. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:655–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fournier S, Bastuji-Garin S, Mentec H, Revuz J, Roujeau JC. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:558–559. doi: 10.1007/BF02113442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka A, Nakano M, Tani M, Kira M, Katayama I, Nakagawa J, et al. Adult case of Stevens-Johnson syndrome possibly induced by Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection with severe involvement of bronchial epithelium resulting in constructive respiratory disorder. J Dermatol. 2013;40:492–494. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalaf D, Toema B, Dabbour N, Jehani F. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with severe cytomegalovirus infection in a patient on regular hemodialysis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2011;3:e2011004. doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2011.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannenberg SM, Jordaan HF, Koegelenberg CF, Von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, Visser WI. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome in South Africa: A 3-year prospective study. QJM. 2012;105:839–846. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavlos R, Mallal S, Ostrov D, Pompeu Y, Phillips E. Fever, rash and systemic symptoms: Understanding the role of virus and HLA in severe cutaneous drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badia M, Trujillano J, Gascó E, Casanova JM, Alvarez M, León M. Skin lesions in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1271–1276. doi: 10.1007/s001340051056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neff P, Meuli-Simmen C, Kempf W, Gaspert T, Meyer VE, Künzi W. Lyell syndrome revisited: Analysis of 18 cases of severe bullous skin disease in a burns unit. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rzany B, Mockenhaupt M, Baur S, Schröder W, Stocker U, Mueller J, et al. Epidemiology of erythema exsudativum multiforme majus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Germany (1990–1992): Structure and results of a population-based registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:769–773. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneck J, Fagot JP, Sekula P, Sassolas B, Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M. Effects of treatments on the mortality of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: A retrospective study on patients included in the prospective EuroSCAR study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, Roujeau JC, Revuz J, Wolkenstein P. SCORTEN: A severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung WH, Hung SI. Recent advances in the genetics and immunology of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;66:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perkins JR, Ayuso P, Cornejo-Garcia JA, Ranea JA. The study of severe cutaneous drug hypersensitivity reactions from a systems biology perspective. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14:301–306. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, Naldi L, Halevy S, Bouwes Bavinck JN, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. The EuroSCAR-study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:35–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen P, Lin JJ, Lu CS, Ong CT, Hsieh PF, Yang CC, et al. Carbamazepine-induced toxic effects and HLA-B*1502 screening in Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1126–1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, Molina JM, Workman C, Tomazic J, et al. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:568–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hershfield MS, Callaghan JT, Tassaneeyakul W, Mushiroda T, Thorn CF, Klein TE, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for human leukocyte antigen-B genotype and allopurinol dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:153–158. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tassaneeyakul W, Jantararoungtong T, Chen P, Lin PY, Tiamkao S, Khunarkornsiri U, et al. Strong association between HLA-B*5801 and allopurinol-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in a Thai population. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19:704–709. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328330a3b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mockenhaupt M. Severe drug-induced skin reactions: clinical pattern, diagnostics and therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:142–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araki Y, Sotozono C, Inatomi T, Ueta M, Yokoi N, Ueda E, et al. Successful treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with steroid pulse therapy at disease onset. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López-Garcia JS, Rivas Jara L, Garcia-Lozano CI, Conesa E, de Juan IE, Murube del Castillo J. Ocular features and histopathologic changes during follow-up of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Rojas MV, Dart JK, Saw VP. The natural history of Stevens Johnson syndrome: patterns of chronic ocular disease and the role of systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1048–1053. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.109124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prabhasawat P, Tesavibul N, Karnchanachetanee C, Kasemson S. Efficacy of cyclosporine 0.05% eye drops in Stevens Johnson syndrome with chronic dry eye. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29:372–377. doi: 10.1089/jop.2012.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hague JS, Goulding JM, Long TM, Gee BC. Respiratory involvement in toxic epidermal necrolysis portends a poor prognosis that may not be reflected in SCORTEN. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1294–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thong BY. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: An Asia-pacific perspective. Asia Pac Allergy. 2013;3:215–223. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.4.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Wild T, Stollwerck PL, Namdar T, Stang FH, Mailänder P, Siemers F. Are multimorbidities underestimated in scoring systems of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis like in SCORTEN. Eplasty. 2012;12:e35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HY, Dunant A, Sekula P, Mockenhaupt M, Wolkenstein P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. The role of prior corticosteroid use on the clinical course of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case-control analysis of patients selected from the multinational EuroSCAR and RegiSCAR studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]