Abstract

Tropomyosins (Tm) in humans are expressed from four distinct genes and by alternate splicing >40 different Tm polypeptide chains can be made. The functional Tm unit is a dimer of two parallel polypeptide chains and these can be assembled from identical (homodimer) or different (heterodimer) polypeptide chains provided both chains are of the same length. Since most cells express multiple isoforms of Tm, the number of different homo and heterodimers that can be assembled becomes very large. We review the mechanism of dimer assembly and how preferential assembly of some heterodimers is driven by thermodynamic stability. We examine how in vitro studies can reveal functional differences between Tm homo and heterodimers (stability, actin affinity, flexibility) and the implication for how there could be selection of Tm isomers in the assembly on to an actin filament. The role of Tm heterodimers becomes more complex when mutations in Tm are considered, such as those associated with cardiomyopathies, since mutations can appear in only one of the chains.

Keywords: Heterodimers and homodimers, Tropomyosin isoforms, Coiled-coils, Actin, Cardiomyopathy mutations

Introduction

Tropomyosins (Tm) form a large family of highly conserved α-helical coil-coiled proteins, which in mammals are expressed from four different genes TPM1–4. These four different genes are the root of the functionally diverse forms of tropomyosin that can exist but Tms are far more varied than can be predicted from simple gene diversity. Individual Tm genes can be alternatively spliced to produce two (TPM4), three (TPM2), five (TPM3) and eleven (TPM1) distinct Tm chains (Lin et al. 2008). Since Tm is assembled from two polypeptide chains, expression of multiple isoforms in one tissue can result in distinct populations of homo and heterodimers. (NB We will use the term dimer throughout this work to refer to the single Tm molecule containing two polypeptide chains.) Tms assemble head-to-tail along actin filaments to form a continuous chain. If multiple forms of the Tm dimer exist in a single cell then there is the potential for additional polymorphism in the assembly of mixed Tm dimers onto actin filaments. Thus heterogeneity can exist at the level of the gene, the monomeric protein chains, the Tm dimers and the assembled Tm dimers onto actin. The extent to which such heterogeneity exists in cells is not well defined. Here we will examine the evidence for the assembly of homo and heterodimers of Tm and their ability to form copolymers on the surface of actin.

Mammalian fast skeletal muscle thin-filaments express two major Tm isoforms, traditionally called skα- and skβ-Tm, and equivalent smα- and smβ-Tm isoforms are found in smooth muscle. The two α isoforms are expressed from alternate splicing of the TPM1 gene and the two β isoforms from TPM2.1 The two polypeptide chains skα and skβ form the Tm dimers skαα-, and skαβ-Tm in fast skeletal muscle in a 60:40 ratio (Lehrer 1975; Bronson and Schachat 1982) and in cardiac muscle cells skαα is present at >90 %. The proportion of skαβ varies between muscle types and species with generally a higher level of skβ-Tm in larger mammals and slower muscles; however, there does not appear to be a simple correlation between speed and isoform content (Bicer and Reiser 2013). The skββ-Tm can be assembled in vitro but has low thermal stability (Lehrer and Joseph 1987) and is not found in most muscle tissues. An excess of β-Tm over α-Tm is reported in some specific muscle tissue which requires the formation of ββ-Tm dimers, notably the rabbit tongue (Bronson and Schachat 1982), mouse tibialis anterior (Corbett et al. 2005) and the temporalis of some squirrels, chipmunks and turtles (Bicer et al. 2011). Minor Tm components are also present in cardiac sarcomeres, κ-Tm (skα1-1 Tm from gene TPM1)(Rajan et al. 2010). In mammalian slow muscle the sk-αTm is replaced by skα-slow Tm (γ-Tm). The α-slow Tm can form dimers with β-Tm but little is known about the ability of κ-Tm to form heterodimers. Chicken gizzard muscle cells express equal amounts of smα-Tm and smβ-Tm and form exclusively smαβ-Tm heterodimers (Sanders et al. 1986) because of greater thermodynamic stability of the heterodimer than the ββ-Tm homodimer (Lehrer and Stafford 1991).

Tms assemble head to tail along actin filaments to form a continuous chain and for the actin in the muscle sarcomere the αα- and αβ-Tm are considered to co-assemble on to the same actin filament; i.e. there is a heterogeneous mixture of αα and αβ along a single actin filament.

In both muscle and non-muscle cells there is a variety of cytoplasmic Tm chains that can be expressed and therefore much greater potential for both homo and heterodimer formation and polymorphism in the assembly of dimers on to the actin filament. The full extent of heterodimer formation amongst cytoplasmic Tms has not been defined although some Tms can form heterodimers. For example, the fibroblast Tm-4 and Tm-5(NM-1) Tm isoforms are able to form both heterodimers and homodimers (Temm-Grove et al. 1996). Similarly the degree of polymorphism in Tm dimers (homodimers or heterodimers) that may assemble onto a single actin filament has not been studied in detail.

We have recently been exploring heterodimer formation in vitro for the mammalian skeletal muscle Tm and there is an extensive literature on dimer assembly in smooth muscle Tm. We will review the literature on in vitro assembly of these Tm dimers and their assembly on to actin filaments before exploring the implication of the work for the wider family of Tm isoforms.

Trigger sequences for Tm dimer assembly?

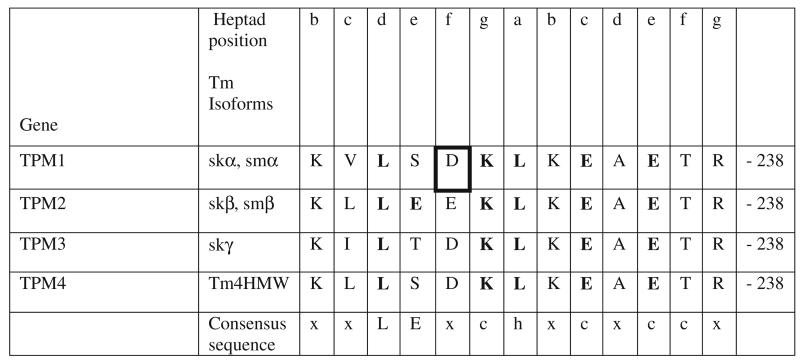

The α-helical coil-coils of Tm consist of two right-handed amphipathic chains (Crick 1953) with characteristic heptad repeats of seven residues denoted a to g (Sodek et al. 1972). There is a strong preference for small hydrophobic residues at positions a and d that form the close-packed hydrophobic core of the dimer. This core is further stabilised by electrostatic interactions across the dimer between residues at positions g and e, (McLachlan and Stewart 1976; Wolska and Wieczorek 2003). If this were the only requirement for coiled-coil formation then it is possible to imagine the polypeptide chains being relatively promiscuous in partner selection. In fact there is a strong thermodynamic selection for coiled-coils assembled from polypeptides of equal length since this will maximise the degree of interaction between the two partners. In general coiled-coil dimers also may have distinct sites within the heptad-repeat amino acid sequences necessary for the mediation of coiled-coil formation (Kammerer et al. 1998). These short autonomous folding units, or trigger sequences, were initially identified in the Dictyostelium discoideum actin-bundling protein cortexillin I (Steinmetz et al. 1998) and the yeast transcriptional activator GCN4 (Kammerer et al. 1998). Alignment of other two-stranded coil-coiled sequences revealed putative trigger motifs in human kinesin, chicken gizzard smooth muscle myosin II and human skβ-Tm (Kammerer et al. 1998). The consensus trigger sequence together with the corresponding putative trigger sequences present in all human Tm isoforms are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of the putative trigger motifs from exon7 and 8 of the four human TPM genes. Lower case letters indicate heptad position; residues matching consensus sequence are in bold; x, any residue; c, charged residue; h, hydrophobic residue, residue in bold square indicates the position of recently discovered dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) mutation Asp230Asn in skα-Tm

This section of sequence is in the constitutive exon 7 and 8 of each tropomyosin gene so is identical in all isoforms expressed from the respective gene. All Tms have the conserved sequence but the skβ sequence is the closest to the consensus sequence. All four Tms have Thr in place of a charged residue at 237. Additionally all Tms except the β-Tm expressed from TPM2 diverge from the consensus at position 229 where Ser or Thr replace Glu. A novel dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) mutation was recently discovered in this region (Lakdawala et al. 2010). Substitution of negatively charged Asp at 230 for polar uncharged Asn in the f position of the heptad will not affect interactions across the dimer interface. However the Asn substitution might cause destabilization of the α-helix as native negatively charged Asp can form salt bridges with positively charged Lys-286 (i+4) and Lys-233 (i+3) in the same chain. We are not aware if the stability of this mutation has been studied experimentally.

We re-examined the sequences of human Tms and found that most Tms have at least one other region containing the putative trigger sequence with two or fewer mismatches. Skβ-Tm (from TMP2, constitutive exon 5) and δ-Tm (TPM4, exon 5) both have a 100 % match in the region V170-E181. A region of the constitutive exon 8 and the alternatively spliced exon 9 of TPM1, TPM3 and TMP4 all define closely related protein sequences with one (A247-K259, TPM3 and TPM4) or two mismatches (D254-K266, TPM1). Thus there appear to be at least two such sequence in many of the human Tms.

The role of the trigger sequence in Tm assembly has not been fully established and there is significant evidence that the sequence identified by Kammerer et al. is not essential. A recent study (Hodges et al. 2009) showed that deletions of various N- and C-fragments do not affect dimer assembly but do dramatically decrease the thermal stability. This study led to the identification of a different region called the stability control region (97–118) which does not mediate folding/assembly but is crucial for the final protein stability. It is probable that any short amino acid sequence able to stabilise an alpha helix (hydrogen-bonding and salt bridge network) and promote dimer, hydrophobic core interactions will lead to the formation of a coiled-coil (Hodges et al. 2009; Kirwan and Hodges 2010; Steinmetz et al. 2007).

The role of trigger sequences in low molecular weight fibroblast tropomyosins Tm-4 and Tm-5 (NM-1) was studied by Araya et al. (2002) who concluded that the sequence was required for the formation of Tm-4 homodimers but not for the formation of heterodimers between Tm-4 and Tm-5 (Araya et al. 2002).

Assembly of Tm heterodimers in vitro

Chicken gizzard and frog skeletal muscle Tms preferentially form αβ heterodimers

For some muscles such as chicken gizzard smooth and Rana esculenta skeletal muscle, the fraction of β/α Tm chains present in vivo approaches 1, and equal amounts of β and α were also found in Rana temporaria frog skeletal muscle (Hvidt and Lehrer 1992; Lehrer et al. 1989). In these muscles the predominant species of Tm is the heterodimer, αβ, rather than an equal mixture of αα and ββ or that expected for random assembly of two monomers, a statistical mixture of 50 % αβ and 25 % of each homodimer. For R. esculenta (Hvidt and Lehrer 1992; Lehrer et al. 1989) and chicken gizzard Tms (Lehrer and Qian 1990; Lehrer and Stafford 1991) it was shown in vitro that under physiological conditions an equal mixture of homodimers slowly converts to heterodimers. Thus, if homodimers are formed first in biosynthesis, they would convert to heterodimers over time. In these cases the explanation for the predominance of heterodimers appears to be a thermodynamic one, so no biological factors need be invoked to promote heterodimer formation. The preference of heterodimers over homodimers can be determined from an equilibrium thermodynamic analysis of the reaction 2αβ ↔ αα + ββ. The equilibrium constant (Keq) for this exchange reaction is given by

where the K’s are individual dissociation constants. At a given temperature, αβ will be preferred over a mixture of αα and ββ if or equivalently if ΔG°αβ < ½ (ΔG°αα + ΔG°ββ) + RT In2. It thus appears that αβ forms at temperatures where ββ is relatively unstable in order to minimize the total free energy. A similar explanation was used to explain the formation of heterodimeric leucine-zipper coiled-coils (O’Shea et al. 1989).

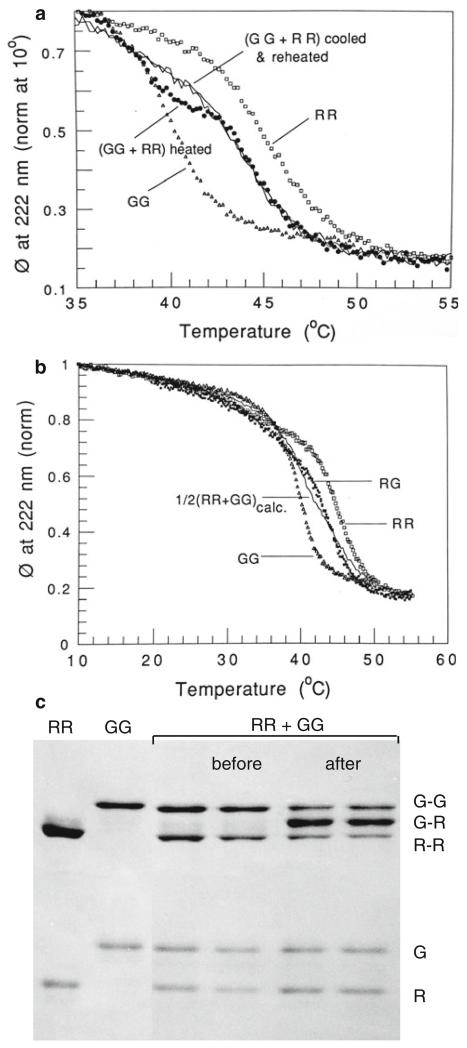

Chicken gizzard αTm (GG) is much less stable than rabbit skeletal αTm (RR) with T1/2 = 40 and 45 °C, respectively, in 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM Hepes pH 7.3 (Fig. 2). To test the ideas presented above with some novel experiments, a mixture of rabbit skeletal αTm + chicken gizzard αTm homodimers (RR+GG, respectively) was thermally unfolded. If thermodynamics apply, the unfolding curve should first follow the unfolding/dissociation of GG homodimer and as the temperature is raised, the more stable RR should then chain exchange with the unfolded G to form heterodimer RG, if the rate is not too slow. The unfolding should then follow a new curve representing the unfolding/dissociation of RG heterodimer. This is what was observed (Fig. 2). On cooling slowly from unfolded chains, RG was refolded and not RR+GG as seen from the refolding profile. Kinetic studies showed that for conditions noted in Fig. 2a, b at 40 °C, RG is formed with a half-time of 12 min from a mixture of RR+GG. Thus, at physiological temperature, heterodimers of rabbit skeletal Tm and chicken gizzard Tm are produced from mixtures of these two different Tms. The heterodimer RG has an intermediate thermal stability between that of RR and GG. To further verify the exchange, the heterodimers thus formed were disulfide cross-linked with DTNB at Cys 190 (Lehrer 1975). The R–R, G–G and R–G dimers can be identified on SDS-gels because of their different mobilities. To prove that RG was formed, RR, GG and a mixture of RR+GG were cross-linked, before and after the CD heating/cooling run (Fig. 2). Cross-linked R–G bands with intermediate mobility were produced with intensity much more than twice that of R–R or G–G (Fig. 2c). These data show that coiled-coil Tms from different species can preferentially form heterodimers if their stabilities are sufficiently different simply as a consequence of thermodynamics. Of course, there may be other requirements, e.g., Tms of different lengths may not be stable enough to form heterodimers, chaperones may be used in certain cases.

Fig. 2.

a Helix unfolding of gizzard α-Tm (GG), rabbit skeletal α-Tm (RR) and an equal mixture of GG+RR. Note that: (1) GG is less stable than RR; (2) in the mixture, GG starts to unfold first, but at 39 °C refolds with a different profile from GG or RR; (3) on slow cooling and reheating (left right arrow) this intermediate stability is maintained. b Helix unfolding of dimers of rabbit skeletal α-Tm (RR) and chicken gizzard α-Tm (GG) and the product (RG) after the heating/cooling cycle of RR+GG. RG is not an equal mixture of RR and GG. c Gels of DTNB-cross-linked samples of rabbit skeletal α-Tm (R) and chicken gizzard α-Tm (G). RR+GG mixtures were treated at room temperature with 1 mM DTNB for several hours before and after thermal unfolding/refolding (see CD run). Conditions: 0.03 mg/ml Tm in 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM Hepes buffer pH 7.3

It should be noted that, in contrast to the chicken gizzard muscle sm-Tm described above, a significantly larger fraction of the total Tm found in mammalian vascular smooth muscle is α-Tm and that the α- and β-Tm do not always co-localise (Gallant et al. 2011; Yamaguchi et al. 1984). Gallant et al. (2011) show by immunofluorescence and western blots that the majority of Tm in mammalian arterial tissue is smα-Tm which means that the αβ-Tm heterodimer cannot be the only Tm dimer present. In fact the two Tm isoforms associate to a different extent with distinct actin populations. The major cytoplasmic β-actin immunoprecipitated with mostly α-Tm while the dynamic peripheral γ-actin precipitated predominantly with β-Tm. In contrast, the muscle specific contractile α-actin does co purify with similar amounts of α- and β-Tm. Which Tm dimers are present in any of the three actin·Tm populations is not known, but since both smα- and smβ-Tm are present the contractile α-actin filament could contain αβ-Tm as seen in chicken gizzard muscle. It remains to be defined how these Tm isoforms, and the other cytoplasmic Tm isoforms, recognise specific actin populations and/or regions of the smooth muscle cell (See below and Gunning this issue).

Mammalian skeletal and cardiac muscle Tm form mixed homo and heterodimers in vitro

Mammalian fast skeletal and cardiac tissues express variable ratios of α- and β-Tm and assemble as αα and αβ dimers. The assumption was therefore that the dimer assembly would be similar to smooth Tm with a strong preference for αβ dimers. The expression level of β-Tm would then control the levels of αα vs αβ present in tissue. But a study of assembly of sk-Tm using E. coli expressed Tm (carrying the Ala–Ser N-terminal extension to mimic acetylation (Monteiro et al. 1994)) showed a small preference for homodimer assembly. Chain exchange studies starting with equal amounts of αα and ββ result in the formation of ~20 % αβ heterodimers and 40 % each of αα and ββ at room temperature equilibrium (Kalyva et al. 2012). If the level of β expressed is low then random assembly of the more stable αβ will limit the formation of any ββ. However as the α:β ratio approaches 1 then some assisted assembly process, possibly involving chaperones, may be required to ensure that β-Tm only assembles as αβ.

The expression of multiple cytoplasmic Tm isoforms in both muscle and non-muscle cells make an understanding of the formation of Tm heterodimers in vivo a much more complex issue than it is in vitro. The possibility of heterodimer formation amongst cytoplasmic Tms has not been explored in any detail in vitro. Studies on human fibroblasts (Novy et al. 1993) and mammalian vascular smooth muscle cells (Gallant et al. 2011) showed expression of multiple Tm isoforms. In the latter at least five low molecular weight and high molecular weight isoforms were observed. Cross-linking studies in situ and in vitro could provide some information about the heterodimer species present (Bronson and Schachat 1982). Using pull-down assays Gimona et al. (1995) demonstrated that expression of skα, smα or skβ −Tm in rat fibroblasts resulted in formation of heterodimers with any of the high molecular weight Tms present in the cell (namely Tm1, Tm2 and Tm3), but not with the shorter Tms, Tm4 (fromTPM4), Tm5a orTm5b (from TPM1) (Gimona et al. 1995). Thus the potential to form heterodimers is clearly present in cells, and the type of dimers formed may depend on the expression levels as well as any controlled assembly process.

The expression levels of different Tm isoforms in striated muscles is associated with the type of muscle, location within the body, developmental stage (Muthuchamy et al. 1993) and presence of pathological muscle impairments such as cancer (Gunning et al. 2008) or heart failure (Rajan et al. 2010). Fast-twitch skeletal muscles (rabbit psoas) express skα-Tm and skβ-Tm in a 60:40 % ratio predominantly as skαβ-Tm heterodimer (Lehrer 1975) whereas rabbit slow-twitch skeletal muscles (semimembranosus) contain 5 % of the specific slow muscle isoform skαslow–Tm (a skαs-Tm from the TPM3 gene in humans) in addition to skα-Tm and skβ-Tm (Kopylova et al. 2013). The proportion of skαslow–Tm in slow muscles varies considerably; 44 % present in rat soleus and 41 % in dog gastrocnemius muscles (Bicer and Reiser 2013). The heterodimers present in slow muscle have not been defined.

Adult human heart extracts are reported to contain a majority of the skα1-Tm isoform and up to 20 % of skβ-Tm isoform present as αβ-Tm heterodimer (Leger et al. 1976). However, other studies using tropomyosin extracted from human ventricle identified the presence of only skα1-Tm isoform (Purcell et al. 1999). A more recent study identified a different human cardiac isoform skα1-1 Tm, or κ-Tm, that accounts for up to 5 % of heart tropomyosin (Rajan et al. 2010). This isoform is also expressed from TPM1 and is identical with Tmskα1, except for the substitution of exon 2b, found in skeletal muscle α-Tm, for exon 2a, found in smooth muscle αTm.

Functional differences between Tm homo and heterodimers

The diversity of Tm isoforms expressed in various tissues and the ability to shift the specific ratio between Tm isoforms raise important questions of:

Are there preferences in dimer formation between skα-, skβ- and skα2-Tm in skeletal and skα, skβ and skα1-1 Tm isoforms in cardiac tissues?

Is there any preference in how the isoforms assemble on to actin filaments?

What are the functional differences between these dimeric Tms (both homo- and heterodimers)?

Understanding the different roles of αα vs αβ-Tm dimers is therefore important if we want to understand why the isoform ratio varies in different mammalian tissues.

The differences between αα, ββ and αβ-Tms were first addressed for sm-Tm since the α and β isoforms could be separated or expressed in E. coli (with or without an Ala–Ser N-terminal extension to mimic acetylation (Monteiro et al. 1994)) and recombination of the α and β results in exclusively αβ dimers as described above.

In contrast, studies of the functional role of striated muscle αβ-Tm heterodimers have been hindered due to the difficulties in tissue purification and in the reconstitution of recombinantly expressed samples. Firstly there is no mammalian skeletal muscle containing purely αβ-Tm heterodimers; therefore any tissue purified material results in a mixture of αα- and αβ-Tm. Although separation of the αα and αβ-Tm dimers is possible on hydroxyapatite column (Eisenberg and Kielley 1974), it is not always reproducible. Secondly the mixture of recombinantly expressed striated αα- and ββ-Tm homodimers after heating treatment, required for a chain exchange, resulted in the mixture of homo-(αα, ββ) and heterodimers (αβ).

We resolved the purification problems simply by introduction of an N-terminal affinity tag (His or Strep) on the bacterially expressed skβ-Tm. Isolation of the singly tagged αβ-Tm was then possible from the zero tagged αα- or double tagged ββ-Tm using Ni affinity chromatography. The tag was proteolytically cleaved after purification allowing the study of the properties of native-like Tm (Kalyva et al. 2012).

Table 1 lists the affinity for actin of both sm- and sk-Tm dimers. The affinity of the sk-Tm αα and αβ dimers for actin are much weaker than those of smTm but the two ββ dimers are of the same order. Skα- and smα-Tm mRNA differ at the C-terminal exon and two internal exons (2 and 6) while β-Tm differs at the C-terminal exon and exon 6. The head-to-tail overlap of dimers is essential for the head-to tail-polymerisation of Tm on actin (Frye et al. 2010; Greenfield et al. 2006). Swapping just the residues encoded by the C-terminal exons (Cho and Hitchcock-DeGregori 1991) or just the last 10 amino acids at the C-terminus (Coulton et al. 2008) is sufficient to swap the affinities of sk and sm homodimers. This suggests the internal exons play a minor role in defining the differences in affinity between smooth and skeletal muscle isoforms. For sm-Tm the affinity for actin was similar for αα and αβ but 10-fold weaker for ββ-Tms. In contrast for the sk isoforms all three dimers had a similar affinity (0.13–0.36 μM) for actin with ββ being tightest and αβ the weakest. It should be noted that in the striated muscle cell the affinity of sk-Tm for actin is enhanced by the binding of the TnT1 part of troponin T to the Tm–Tm overlap region. The difference in affinity for actin between αα and αβ for both sm and sk-Tm are not sufficient to have any major influence of the preferential binding of αα over αβ.

Table 1.

Actin affinity of striated and smooth αα-, αβ- and ββ-Tm dimers

| Tm dimers | Actin affinity skTm K50% (μM) |

Actin affinity smTm K50% (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| αα-Tm | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.035 |

| αβ-Tm | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 0.03 |

| ββ-Tm | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.30 |

Actin binding affinity (K50%) was derived for the fit of the Hill equation to data (n = 3; ±SD). The sm-Tm data are from Coulton et al. (2008), and sk-Tm data are from Kalyva et al. (2012)

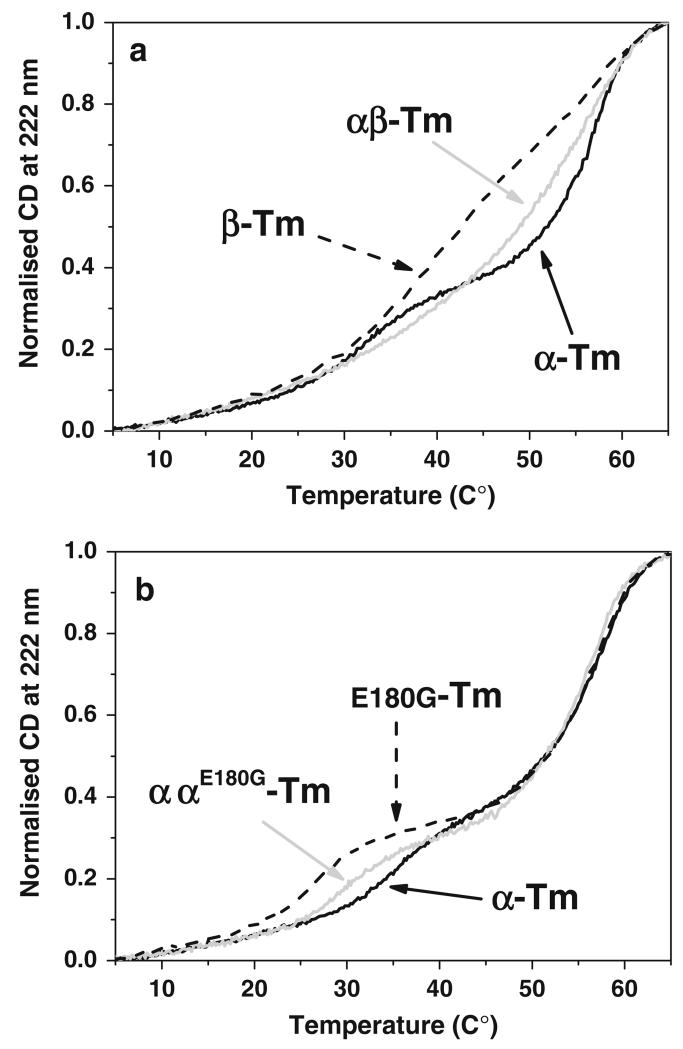

Thermal unfolding assays were performed with Tm heterodimers. To ensure that changes in the population of heterodimers were not occurring after unfolding and refolding, the assays were performed with both reduced or cross-linked Tm (oxidation of at Cys 190 in αα or αβ Tm and at both Cys 36 and 190 for β chain; (Lehrer and Stafford 1991)). In all cases the αβ Tm has intermediate stability between that for the αα and the less stable ββ. But note the corresponding melting curves, indicating that the heterodimer was not simply the arithmetic mean of the two homodimer melting curves, but has its own distinct thermal properties. See Fig. 3 and Kremneva et al. (2004).

Fig. 3.

Thermal unfolding of Tm homo and heterodimers. Normalised unfolding profiles of 7 μM cross-linked homo and heterodimers of sk-Tm. a skαα-Tm (black line), skββ-Tm (dashed lines) and skαβ-Tm (grey line); data from Kalyva et al. (2012). b skαα-wt Tm (black line) and the homo (grey line) and heterodimer (dashed line) of the E180G cardiomyopathy mutation. Data from Janco et al. 2012. Each plot is the average of three repeated melting curves on the same sample. Buffer conditions: 0.5 M KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0

As a final test of the differences between Tm dimers the calcium regulation of myosin S1 myosin binding to reconstituted cardiac thin filaments was measured. These assays showed no detectable differences in the way the three Tm dimers influenced myosin binding to actin (Kalyva et al. 2012). The results presented in Kalyva’s study showed that it is not simple to define the functional differences between skαα and skαβ, nor is it possible to explain why there are different ratios of αα and αβ in different cells. What is clear is that the biochemical properties of Tm heterodimers cannot be derived from the mean properties of the two homodimers.

The work of Kalyva did not report the effect of the Tm dimer on calcium sensitivity. In an earlier work Boussouf et al. (2007) used only the αα and ββ-Tm homodimers and reported that in the presence of cardiac Tn the mid-point of the pCa curve was shifted by +0.2 pCa units for ββ-Tm compared to αα-Tm, viz. there was an increase in calcium sensitivity. In contrast note the Tm isoform had no effect on calcium sensitivity when assembled with skeletal muscle Tn. The calcium sensitivity of the αβ-Tm needs to be defined to understand the physiological effect of the isoform mix.

In vivo studies of mouse hearts have explored the effect of alterations in the ratios of Tm isoform expressed. The adult mouse heart normally expresses only α-Tm. Over expression of β-Tm or skαslow-Tm (up to 50 % of total Tm) results in no changes in heart or cell morphology but there are changes to the cardiac performance. These include changes in the rates of relaxation and a shift in the calcium sensitivity which both go in opposite directions for the skβ- and skαslow-Tms (Jagatheesan et al. 2010). Results of studies in transgenic mice can be more complex due to associated changes in the expression of other cardiac protein isoforms and alterations in protein phosphorylation levels. However, the data of Jagatheesan et al. do point to a change in properties of the thin filament linked to the Tm isoform composition. The changes in calcium sensitivity need to be examined for purified thin filaments to establish that this is due solely to the change in Tm isoform.

Tm with a mutation in one chain

Both hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies (HCM and DCM respectively) are complex disorders of the heart caused, in many cases, by simple single-point missense mutations in various sarcomeric proteins. To date, there are 11 HCM and 4 DCM mutations associated with the TPM1, skα-Tm gene (Kalyva et al. 2012; Lakdawala et al. 2010; Olson et al. 2001; Regitz-Zagrosek et al. 2000; Wieczorek et al. 2008); and none with the TPM2 β-Tm gene. (Although there are skeletal muscle myopathies associated with the TPM2 gene (Mokbel et al. 2013; Tajsharghi et al. 2012)). These autosomal dominant mutations in Tm cause remodelling of the heart wall and can result in arrhythmias which can lead to sudden cardiac death or heart failure (Seidman and Seidman 2001).

As mentioned previously, human heart express a majority (90 %) of skα-Tm isoform (Kopylova et al. 2013; Leger et al. 1976). In cardiomyopathy affected individuals, due to their heterozygous background, cardiac cells are expected to express both WT (α-Tm chains) and the mutation (α*-Tm chain). Thus the presence of αα, αα* and α*α*-Tm dimers may be expected to occur. In fact the ratio of Tm mutant to WT monomers expressed within the myocardium differ depending upon age, location and progression or/and severity of the disease. The presence of other Tm isoforms in cardiac tissue increases the number of possible Tm dimers. Thus αβ; α*β may also be expected. The ability of the κ-Tm to form dimers (ακ; α*κ; βκ) has not been assessed. In considering the progression of the cardiomyopathy the role of the different dimers must also be considered. The properties of Tm heterodimers carrying a single copy of the mutation had not been explored due to lack of a reliable method for their formation in vitro just as for αβ-Tm. We have used the same tagging method as used for αβ-Tm (Kalyva et al. 2012) and optimized it for the formation and purification of the αα*-Tm heterodimer carrying either Asp175Asn or Glu180Gly HCM mutations (Janco et al. 2012). The biochemical and biophysical properties of both Asp175Asn and Glu180Gly Tm homodimers have been widely studied and are well established in vitro (Golitsina et al. 1997; Kalyva et al. 2012; Kremneva et al. 2004; Li et al. 2012) and key data are summarized in Table 2 together with the more recent heterodimer data.

Table 2.

Biochemical properties of striated α-Tm carrying Asp175Asn or Glu180Gly in one or both chains of dimer

| Tm dimers | Actin affinity K50% (μM) | Calcium sensitivity pCa50% | Apparent persistence length PLa (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT-Tm | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 5.89 ± 0.01 | 109 ± 19 |

| WT-D175 N–Tm | 0.23 ± 0.05‡ | 6.00 ± 0.06* | 85 ± 9§ |

| D175 N–Tm | 0.52 ± 0.15** | 5.97 ± 0.05* | 81 ± 8 |

| WT-E180G-Tm | 0.27 ± 0.03* | 5.92 ± 0.03 | 72 ± 8§ |

| E180G-Tm | 0.42 ± 0.12*,† | 6.03 ± 0.06*,† | 82 ± 3 |

Actin binding affinity (K50%) was derived for the fit of the Hill equation to data (n ≥ 4; ±SD). Measured values of pCa50% represent the calcium sensitivity of S1 binding to a reconstituted thin filament with WT, HCM homo- or heterodimer Tm mutants (n = 3; ±SD). The apparent persistence length (PLa) of isolated Tm homo- and heterodimers carrying HCM mutations. PLa was determined by the tangent correlation method applied to >750 wildtype homodimers, >200 mutant homodimers, and ~1,000 for mutant heterodimers skeletonized Tm molecules from four preparations

Different from the WT value (p ≤ 0.05).

Different from the WT value (p ≤ 0.001).

Different from the E180G heterodimer value (p ≤ 0.05).

Different from the D175 N heterodimer value (p ≤ 0.01).

K50% and pCa50% data are from Janco et al. (2012); PLa data are from Li et al. (2012); and are a new data

In vitro assays of HCM Tm homodimers showed decreased thermal stability in E180G while D175 N homodimers were indistinguishable from WT-Tm (Kremneva et al. 2004). The heterodimer unfolding profile for the cross-linked E180G proteins is shown in Fig. 3 and demonstrates that the heterodimer has intermediate stability between the two homodimers at ~30–35 °C but all three are identical at higher temperatures. The D175 N was again identical to both homodimers.

An electron microscopy study showed that E180G and D175 N–Tm mutations both caused a ~20 % reduction in persistence length of the protein presumably due to an increase in local and global bending flexibility (Li et al. 2012). We present here novel data on the persistence length of heterodimers using the same approach as for homodimers (Table 2). D175N- and E180G-Tm heterodimers are both indistinguishable from their respective homodimers.

The affinity of Tm for actin was reduced by the mutations. In the case of both D175N and E180G the affinity of homodimer for actin was weaker than the WT (approximately two to threefold) which is consistent with the observed reduction in persistence length. In contrast the D175N heterodimer was indistinguishable from WT while the E180G heterodimer was intermediate between the WT and E180G homodimers.

When the Tm carrying HCM mutations were assembled into actin filaments with human cardiac Tn, both homo and heterodimers of D175N–Tm caused an increase in the calcium sensitivity (~+0.1 pCa units) of the rate of myosin binding to actin·Tm·Tn. These assays are a measure of the calcium induced change in accessibility of the actin sites to myosin (McKillop and Geeves 1993). The change in calcium sensitivity observed is consistent with measurements using D175N Tm homodimers in motility assays and muscle fibre force measurements (Bing et al. 1997; Muthuchamy et al. 1999). In contrast E180G homodimers caused a slightly larger increase in calcium sensitivity (+0.14 pCa units) and the heterodimer was not distinguishable from WT (≤+0.03 pCa units).

Understanding how the point mutations (in homodimers as well as heterodimers) alter Tm function is difficult without a high resolution structure. The role of the mutations in the homodimers has been discussed by the authors mentioned above. The two negatively charged residues D175 and E180 are in the e and g position of the heptad repeat respectively where they could make stabilizing interactions across the dimer interface (Li et al. 2012). This is possible for E180 Tm, where R182 is in the g′ position in the opposite Tm chain. Loss of one or both of these contacts could account for the loss of thermal stability in the E180G-Tm homo and heterodimer. The corresponding residue in the partner chain for D175 is G173 so no interchain interaction is expected and no change in thermal stability is observed. The e and g positions of the heptad are on the surface of the Tm dimer and therefore can interact directly with the partner proteins actin and troponin. Modelling studies suggest that neither D175 nor E180 makes a direct contact with actin but E180 is part of cluster of three glutamate residues (in the region 180–184) and the other two residues are predicted to make contact to actin and could be influenced by a charge change at position 180. Both the D175 and E180 residues are close to a potential interaction site with the troponin IC-T2 complex and could therefore affect both Tn binding to Tm and calcium binding to Tn.

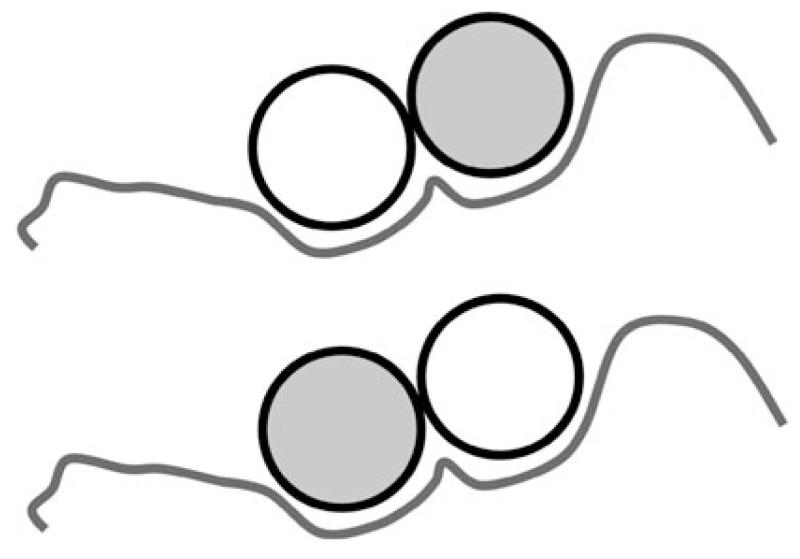

The difference between the homo and heterodimer is that the introduction of a different chain (in αβ-Tm) or a point mutation in one chain (αα*-Tm) changes the αα-Tm from being almost symmetric to asymmetric which means partner proteins can potentially bind to two different faces of Tm. This is simple to imagine for a monomeric binding partner such as Tn in which there can be a preferred orientation of the TmTn complex (see Fig. 4). For Tm interactions with actin it is a little more complex, e.g. the loss of a charge on the surface of Tm may impose a preferred orientation of Tm on actin but this has to be compatible with the orientation of Tm imposed by the TmTm contacts. For αβ-Tm there could be an imposed preference for the orientation of αβ-Tm on actin by an asymmetry in the head-to-tail overlap which could be reinforced or opposed by a mutation affecting a down-stream actin binding contact. Bacchicchio et al., using a fluorescence based assay with chicken smooth muscle Tm, reported that smαα- and smαβ-Tm did indeed have a preferential orientation on actin (Bacchiocchi et al. 2004).

Fig. 4.

End view of a Tm dimer binding to a partner protein such as Tn. The binding site is asymmetric. If the two Tm chains are identical there may be no preference for how Tn binds to the two Tm chains but if the two chains differ in a heterodimer then the two binding modes can differ

Assembly of Tm on to actin-heterogenous Tm on the filament

Tropomyosins can assemble into head-to-tail into polymers via a small overlap of the two pairs of ends of about 10 amino acids. This polymerisation process can be observed in vitro via changes in the viscosity of the solution. Both NMR and crystal structures of the overlap region are available (Frye et al. 2010; Greenfield et al. 2006) showing insertion of the N-terminal coiled-coil between a slightly splayed C-terminal region. The same head-to-tail interaction is central to the polymerisation of Tm on the surface of actin and is the main driver of actin binding. The N-terminus can be alternately spliced between 2 forms (exon 1a and 1b) for three of the four TPM genes. Exon 1a, together with exon 2, is used for HMW Tms while exon 1b is used for LMW Tms. For the C-terminus there are four alternate exons for TPM1 and TPM3, two exons for TPM2 and one in TMP4. Thus there is scope for the alternate N and C-termini to preferentially find a specific binding partner. However, experimental evidence for or against specific binding pairs is not available. In vitro co-polymerisation of different Tms can occur as between skαα and skαβ-Tm.

Where different Tm isoforms with identical N and C termini are expressed then the potential for co-polymers is present. However, the gestalt theory (Holmes and Lehman 2008) of Tm binding to actin in which the Tm shape is matched to the track of Tm on the actin surface, may allow internal exons—through alterations in the shape of Tm, or the exact match with the actin surface in different actin isoforms, to preferentially select specific Tm isoforms. Similarly, in the cell, the initiation of actin assembly of specific actin isoforms via actin binding proteins such as formins (Goode and Eck, 2007) may preferentially recruit a specific Tm isoform to the site of polymerisation. Tm–Tm contacts may then continue to select for specific Tm isoforms to populate/propagate the Tm·actin filament.

In vitro studies of the different Tms binding to actin are possible in bulk solution using competition binding experiments. Alternatively, it could be done by examining how effective Tm isoforms are at displacing each other from actin. But the only way to establish clearly the extent to which Tm isomers co-assemble is through fluorescence labelling of individual Tm dimers and using high resolution single molecule fluorescence methods to look at co-assembly. If we want to understand the role of different Tm isoforms in cell architecture such studies will be required.

The role of Tm isoforms in the formation of dimers and actin filaments has only just begun to be revealed. It remains to be seen how much the Tm is a major or minor player in the complex dance that is the basis of the dynamics of cytoskeleton architecture.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Grant 085309 (MAG) and NIH Grants R37HL036153, P01HL086655 (WL) and R01HL022461 (SSL). MJ was supported by a University of Kent studentship.

Abbreviations

- Tm

Tropomyosin

- Tn

Troponin

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- DCM

Dilated cardiomyopathy

- αα*

Heterodimer of αTm where one chain carries the mutation

- HMW

High molecular weight

- LMW

Low molecular weight

- GG

Chicken gizzard αTm

- RR

Rabbit skeletal αTm

- PLa

Apparent persistence length

Footnotes

The nomenclature of the genes and proteins can be confusing as the traditional protein names continue to be used alongside the more recent nomenclature based on the genes involved. There is no broadly-based systematic nomenclature that has wide agreement. Here we will use the traditional protein nomenclature and cross reference to the more recent names (see Fig. 1 in Gunning et al. (2008) article in this issue of the journal).

Contributor Information

Miro Janco, School of Biosciences, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, UK.

Worawit Suphamungmee, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

Xiaochuan Li, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

William Lehman, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

Sherwin S. Lehrer, Boston Biomedical Research Institute, Watertown, MA, USA

Michael A. Geeves, School of Biosciences, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, UK

References

- Araya E, Berthier C, Kim E, Yeung T, Wang X, Helfman DM. Regulation of coiled-coil assembly in tropomyosins. J Struct Biol. 2002;137:176–183. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2002.4463. doi:10.1006/jsbi.2002.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchiocchi C, Graceffa P, Lehrer SS. Myosin-induced movement of alphaalpha, alphabeta, and betabeta smooth muscle tropomyosin on actin observed by multisite FRET. Biophys J. 2004;86:2295–2307. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74287-3. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74287-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicer S, Patel RJ, Williams JB, Reiser PJ. Patterns of tropomyosin and troponin-T isoform expression in jaw-closing muscles of mammals and reptiles that express masticatory myosin. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:1077–1085. doi: 10.1242/jeb.049213. doi:10.1242/jeb.049213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicer S, Reiser PJ. Complex tropomyosin and troponin T isoform expression patterns in orbital and global fibers of adult dog and rat extraocular muscles. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10974-013-9346-9. doi:10.1007/s10974-013-9346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing W, Redwood CS, Purcell IF, Esposito G, Watkins H, Marston SB. Effects of two hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in alpha-tropomyosin, Asp175Asn and Glu180Gly, on Ca2+ regulation of thin filament motility. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:760–764. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7045. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.7045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussouf SE, Maytum R, Jaquet K, Geeves MA. Role of tropomyosin isoforms in the calcium sensitivity of striated muscle thin filaments. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2007;28:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9103-z. doi:10.1007/s10974-007-9103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson DD, Schachat FH. Heterogeneity of contractile proteins. Differences in tropomyosin in fast, mixed, and slow skeletal muscles of the rabbit. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:3937–3944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YJ, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Relationship between alternatively spliced exons and functional domains in tropomyosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10153–10157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett MA, Akkari PA, Domazetovska A, Cooper ST, North KN, Laing NG, Gunning PW, Hardeman EC. An alphaTropomyosin mutation alters dimer preference in nemaline myopathy. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:42–49. doi: 10.1002/ana.20305. doi:10.1002/ana.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton AT, Koka K, Lehrer SS, Geeves MA. Role of the head-to-tail overlap region in smooth and skeletal muscle beta-tropomyosin. Biochemistry. 2008;47:388–397. doi: 10.1021/bi701144g. doi:10.1021/bi701144g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FHC. The packing of α-helices: simple coiled-coils. Acta Crystallogr. 1953;6:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E, Kielley WW. Troponin–tropomyosin complex. Column chromatographic separation and activity of the three, active troponin components with and without tropomyosin present. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:4742–4748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye J, Klenchin VA, Rayment I. Structure of the tropomyosin overlap complex from chicken smooth muscle: insight into the diversity of N-terminal recognition. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4908–4920. doi: 10.1021/bi100349a. doi:10.1021/bi100349a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant C, Appel S, Graceffa P, Leavis P, Lin JJ, Gunning PW, Schevzov G, Chaponnier C, DeGnore J, Lehman W, Morgan KG. Tropomyosin variants describe distinct functional sub-cellular domains in differentiated vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C1356–C1365. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00450.2010. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00450.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimona M, Watakabe A, Helfman DM. Specificity of dimer formation in tropomyosins: influence of alternatively spliced exons on homodimer and heterodimer assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9776–9780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golitsina N, An Y, Greenfield NJ, Thierfelder L, Iizuka K, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Lehrer SS, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Effects of two familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-causing mutations on alpha-tropomyosin structure and function. Bio-chemistry. 1997;36:4637–4642. doi: 10.1021/bi962970y. doi:10.1021/bi962970y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield NJ, Huang YJ, Swapna GV, Bhattacharya A, Rapp B, Singh A, Montelione GT, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Solution NMR structure of the junction between tropomyosin molecules: implications for actin binding and regulation. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.033. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning P, O’Neill G, Hardeman E. Tropomyosin-based regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in time and space. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1–35. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2007. doi:10.1152/physrev.00001.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RS, Mills J, McReynolds S, Kirwan JP, Tripet B, Osguthorpe D. Identification of a unique “stability control region” that controls protein stability of tropomyosin: a two-stranded alpha-helical coiled-coil. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:747–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.039. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes KC, Lehman W. Gestalt-binding of tropomyosin to actin filaments. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2008;29:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s10974-008-9157-6. doi:10.1007/s10974-008-9157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvidt S, Lehrer SS. Thermally induced chain exchange of frog alpha beta-tropomyosin. Biophys Chem. 1992;45:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(92)87023-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagatheesan G, Rajan S, Wieczorek DF. Investigations into tropomyosin function using mouse models. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:893–898. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.003. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janco M, Kalyva A, Scellini B, Piroddi N, Tesi C, Poggesi C, Geeves MA. α-Tropomyosin with a D175N or E180G mutation in only one chain differs from tropomyosin with mutations in both chains. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9880–9890. doi: 10.1021/bi301323n. doi:10.1021/bi301323n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyva A, Schmidtmann A, Geeves MA. In vitro formation and characterization of the skeletal muscle alpha beta tropomyosin heterodimers. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6388–6399. doi: 10.1021/bi300340r. doi:10.1021/bi300 340r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer RA, Schulthess T, Landwehr R, Lustig A, Engel J, Aebi U, Steinmetz MO. An autonomous folding unit mediates the assembly of two-stranded coiled coils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan JP, Hodges RS. Critical interactions in the stability control region of tropomyosin. J Struct Biol. 2010;170:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.01.020. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopylova GV, Shchepkin DV, Nikitina LV. Study of regulatory effect of tropomyosin on actin–myosin interaction in skeletal muscle by in vitro motility assay. Biochemistry. 2013;78:348–356. doi: 10.1134/S0006297913030073. doi:10.1134/S0006297913030073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremneva E, Boussouf S, Nikolaeva O, Maytum R, Geeves MA, Levitsky DI. Effects of two familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in alpha-tropomyosin, Asp175Asn and Glu180Gly, on the thermal unfolding of actin-bound tropomyosin. Biophys J. 2004;87:3922–3933. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048793. doi:10.1529/biophysj.104.048793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawala NK, Dellefave L, Redwood CS, Sparks E, Cirino AL, Depalma S, Colan SD, Funke B, Zimmerman RS, Robinson P, Watkins H, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, McNally EM, Ho CY. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy caused by an alpha-tropomyosin mutation: the distinctive natural history of sarcomeric dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.017. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger J, Bouveret P, Schwartz K, Swynghedauw B. A comparative study of skeletal and cardiac tropomyosins: sub-units, thiol group content and biological activities. Pflugers Arch. 1976;362:271–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00581181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer SS. Intramolecular crosslinking of tropomyosin via disulfide bond formation: evidence for chain register. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3377–3381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer SS, Joseph D. Differences in local conformation around cysteine residues in alpha alpha, alpha beta, and beta beta rabbit skeletal tropomyosin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;256:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer SS, Qian Y. Unfolding/refolding studies of smooth muscle tropomyosin. Evidence for a chain exchange mechanism in the preferential assembly of the native heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1134–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer SS, Qian YD, Hvidt S. Assembly of the native heterodimer of Rana esculenta tropomyosin by chain exchange. Science. 1989;246:926–928. doi: 10.1126/science.2814515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer SS, Stafford WF., 3rd Preferential assembly of the tropomyosin heterodimer: equilibrium studies. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5682–5688. doi: 10.1021/bi00237a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XE, Suphamungmee W, Janco M, Geeves MA, Marston SB, Fischer S, Lehman W. The flexibility of two tropomyosin mutants, D175 N and E180G, that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;424:493–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.141. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Eppinga RD, Warren KS, McCrae KR. Human tropomyosin isoforms in the regulation of cytoskeleton functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;644:201–222. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85766-4_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop DF, Geeves MA. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys J. 1993;65:693–701. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan AD, Stewart M. The 14-fold periodicity in alpha-tropomyosin and the interaction with actin. J Mol Biol. 1976;103:271–298. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokbel N, Ilkovski B, Kreissl M, Memo M, Jeffries CM, Marttila M, Lehtokari VL, Lemola E, Gronholm M, Yang N, Menard D, Marcorelles P, Echaniz-Laguna A, Reimann J, Vainzof M, Monnier N, Ravenscroft G, McNamara E, Nowak KJ, Laing NG, Wallgren-Pettersson C, Trewhella J, Marston S, Ottenheijm C, North KN, Clarke NF. K7del is a common TPM2 gene mutation associated with nemaline myopathy and raised myofibre calcium sensitivity. Brain. 2013;136:494–507. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws348. doi:10.1093/brain/aws348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro PB, Lataro RC, Ferro JA, Reinach Fde C. Functional alpha-tropomyosin produced in Escherichia coli. A dipeptide extension can substitute the amino-terminal acetyl group. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10461–10466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuchamy M, Pajak L, Howles P, Doetschman T, Wieczorek DF. Developmental analysis of tropomyosin gene expression in embryonic stem cells and mouse embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3311–3323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuchamy M, Pieples K, Rethinasamy P, Hoit B, Grupp IL, Boivin GP, Wolska B, Evans C, Solaro RJ, Wieczorek DF. Mouse model of a familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation in alpha-tropomyosin manifests cardiac dysfunction. Circ Res. 1999;85:47–56. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novy RE, Lin JL, Lin CS, Lin JJ. Human fibroblast tropomyosin isoforms: characterization of cDNA clones and analysis of tropomyosin isoform expression in human tissues and in normal and transformed cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1993;25:267–281. doi: 10.1002/cm.970250307. doi:10.1002/cm.970250307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea EK, Rutkowski R, Stafford WF, 3rd, Kim PS. Preferential heterodimer formation by isolated leucine zippers from fos and jun. Science. 1989;245:646–648. doi: 10.1126/science.2503872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson TM, Kishimoto NY, Whitby FG, Michels VV. Mutations that alter the surface charge of alpha-tropomyosin are associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:723–732. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1339. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2000.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell IF, Bing W, Marston SB. Functional analysis of human cardiac troponin by the in vitro motility assay: comparison of adult, foetal and failing hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:884–891. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan S, Jagatheesan G, Karam CN, Alves ML, Bodi I, Schwartz A, Bulcao CF, D’Souza KM, Akhter SA, Boivin GP, Dube DK, Petrashevskaya N, Herr AB, Hullin R, Liggett SB, Wolska BM, Solaro RJ, Wieczorek DF. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel cardiac-specific human tropomyosin isoform. Circulation. 2010;121:410–418. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.889725. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATION AHA.109.889725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Erdmann J, Wellnhofer E, Raible J, Fleck E. Novel mutation in the alpha-tropomyosin gene and transition from hypertrophic to hypocontractile dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;102:E112–E116. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.e112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C, Burtnick LD, Smillie LB. Native chicken gizzard tropomyosin is predominantly a beta gamma-heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12774–12778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman JG, Seidman C. The genetic basis for cardiomyopathy: from mutation identification to mechanistic paradigms. Cell. 2001;104:557–567. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodek J, Hodges RS, Smillie LB, Jurasek L. Amino-acid sequence of rabbit skeletal tropomyosin and its coiled-coil structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:3800–3804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz MO, Jelesarov I, Matousek WM, Honnappa S, Jahnke W, Missimer JH, Frank S, Alexandrescu AT, Kammerer RA. Molecular basis of coiled-coil formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7062–7067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700321104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700321104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz MO, Stock A, Schulthess T, Landwehr R, Lustig A, Faix J, Gerisch G, Aebi U, Kammerer RA. A distinct 14 residue site triggers coiled-coil formation in cortexillin I. EMBO J. 1998;17:1883–1891. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1883. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.7.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajsharghi H, Ohlsson M, Palm L, Oldfors A. Myopathies associated with beta-tropomyosin mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22:923–933. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.05.018. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temm-Grove CJ, Guo W, Helfman DM. Low molecular weight rat fibroblast tropomyosin 5 (TM-5): cDNA cloning, actin-binding, localization, and coiled-coil interactions. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1996;33:223–240. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)33:3<223::AID-CM6>3.0.CO;2-B. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)33:3<223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek DF, Jagatheesan G, Rajan S. The role of tropomyosin in heart disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;644:132–142. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85766-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolska BM, Wieczorek DM. The role of tropomyosin in the regulation of myocardial contraction and relaxation. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0900-3. doi:10.1007/s00424-002-0900-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M, Ver A, Carlos A, Seidel JC. Modulation of the actin-activated adenosinetriphosphatase activity of myosin by tropomyosin from vascular and gizzard smooth muscles. Biochemistry. 1984;23:774–779. doi: 10.1021/bi00299a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]