Abstract

Surface expression of α-(2,8)-linked polymers of sialic acid in adult tissues has been correlated with metastasis of several human cancers. One approach to chemotherapeutic intervention against the spread of these cancers involves the development of immunogenic molecules that elicit an antibody response against α-(2,8)-linked polysialic acids. Naturally occurring polysialic acids are not viable candidates because they are present during embryonic development and are recognized as self by the immune system. These natural polymers also have poor pharmacokinetic properties because they are readily degraded by neuraminidase enzymes. We have been interested in developing structural surrogates of polysialic acids in an effort to overcome these limitations.

Reported herein are microwave-assisted solid phase peptide syntheses and structural characterization studies of a series of α/δ hybrid peptides derived from Fmoc-Neu2en and Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-OH. Conformational experiments including circular dichroism, NH/ND exchange and ROESY in aqueous solution were performed in order to study the secondary structures of these hybrid foldamers. ROESY data were analyzed with the assistance of XPLOR-NIH that was modified to include parameter and topology files to accommodate unnatural amino acids and the δ amide linkages. The results indicate that stable secondary structure is dependent upon both the amino acid sequence and the configuration of Glu. The most stable foldamer was composed of a total of 6 residues beginning with L-Glu at the carboxy terminus and alternating Neu2en and L-Glu residues. In water, this foldamer adopts a right-handed helical conformation with 3.7 residues per turn, 7.4 Å pitch, 5.8 Å diameter, and a length of 18.5 Å, which is stabilized by both classical C=O•••H-N backbone interactions and by pyranose ring O and L-Glu HN H-bonding. These structural features orient the L-Glu carboxylates along the helical backbone with a periodicity that matches the carboxylate positions along the reported G2+ left-handed helix of α-(2,8)-polysialic acid. However, the charge density of the foldamer is half that of the natural polymer. These findings provide a fundamental understanding of the factors that influence stable secondary structure in hybrid Neu2en/Glu systems, and the tools we have developed establish a viable platform for the rational design of α-(2,8)-polysialic acid surrogates.

Keywords: sialic acid, Neu2en, glutamic acid, α/δ hybrid peptides, foldamers, chimeric peptides, water soluble scaffolds, colominic acid

INTRODUCTION

Significant advances in the rational design and synthesis of peptide mimetics have been achieved in recent years. Many of the developments in this area have addressed some of the pharmacological limitations of naturally occurring biologically active peptides, e.g. enzymatic hydrolysis. A field of unnatural peptide research has emerged, called foldamer science,1 that addresses not only the problem of proteolysis,2,3 but also provides a platform for the mimicry of secondary (2°) structures like helices, sheets and turns,4-10 and higher order helical bundles found in natural peptides.11,12 These unnatural peptides can also act as scaffolds with sophisticated biological functions that include antibacterial magainin mimetics13,14 as well as inhibitors of protein-protein interactions15,16 and viral infections.17,18 In a recent review, developments in structural characterization and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of foldamers document the extensive chemotherapeutic potential and diversity of cyclic and acyclic peptide backbones derived from natural and unnatural amino acids.19

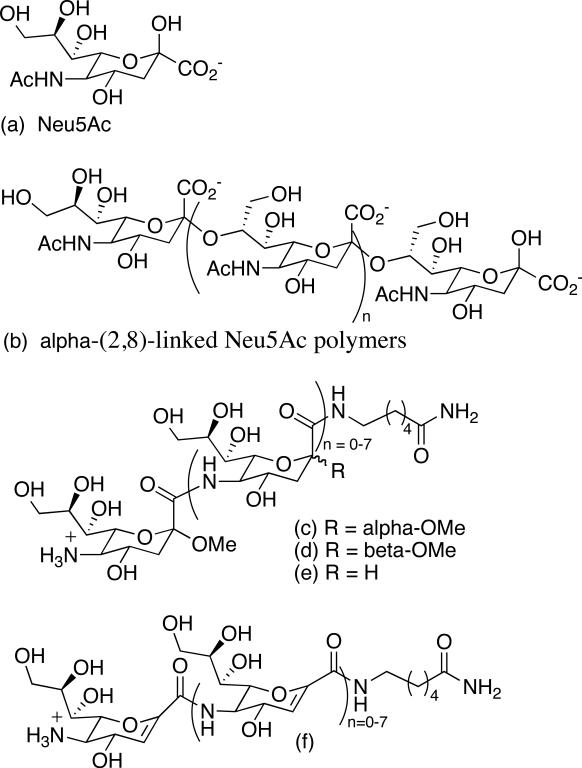

Sugar amino acids (SAAs) are carbohydrates that possess amino and carboxylic acid groups and they serve as novel foldamer building blocks consisting of an amino acid functionality and a rigid sugar pyran framework with desirable water solubility properties.20 Sialic acid (Neu5Ac, Figure 1a) is a naturally occurring nine-carbon pyranose SAA that is typically found as a terminal sugar of oligosaccharides attached to proteins and lipids. These sugar chains decorate mammalian cell surfaces and impart profound effects upon human physiology and pathology.21 In humans, α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac polymers (Figure 1b) post-translationally modify neural cell adhesion molecules (N-CAMs) primarily during embryonic development. N-CAMs are a class of high molecular weight cell surface sialoglycoproteins that function in cell adhesion and cell movement.22-24 Embryonic N-CAM is characterized by a high Neu5Ac content and undergoes a postnatal conversion to the adult form of N-CAM with a low Neu5Ac content.24,25 Cellular adhesion is reduced in embryonic cells presumably due to charge repulsion between the polyanionic structures, which facilitates cellular migration. In contrast, adhesion is promoted between cells expressing the adult form of N-CAM, which helps stabilize adult tissues.

Figure 1.

Synthetic sialic acid and its natural and synthetic homooligomers.

Interestingly, surface expression of Neu5Ac polymers in adult tissues has been correlated with metastasis of several human tumors making this polymer a viable candidate for chemotherapeutic intervention.26-29 Since Neu5Ac polymers are not present in healthy adult tissues, except for localized regions of the brain,30-34 antibody-based approaches provide a means for selectively targeting cancer cells with high Neu5Ac content. This strategy requires the design and synthesis of molecules that when administered to a patient would elicit an immune response that results in the production of antibodies cross-reactive with Neu5Ac polymers. Conventional wisdom suggests that natural Neu5Ac polymers would not be viable candidates because they are seen as self by the immune system.

Our interest in foldamer science has been motivated by the challenge of developing structural surrogates of Neu5Ac polymers with the long-term objective of developing smaller constructs with stable secondary structure and improved bioavailability profiles. Over a decade ago, our program began with a very simple question: How would the structures of amide linked Neu5Ac foldamers compare to glycosidically linked oligomers?35-38 From the early work of Jennings39 and Yamasaki,40 we were aware that decamers of α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac form stable helical structures. At the outset, we did not expect O-linked and amide-linked Neu5Ac polymers to have the same 2° structures, in fact we were not even sure that amide-linked analogs would be water soluble. Therefore our initial studies focused on developing methods for the synthesis of amide-linked oligomers and reliable tools for studying their structural properties. We reported the first Neu5Ac-based unnatural synthetic foldamers that form stable 2° structures in water (Figure 1c-f).41,42 These constructs were primarily characterized by analysis of circular dichroism (CD) studies, which demonstrated that a minimum of 4 residues are required for ordered structure, and further elongation to eight residues increases 2° structure stability. This feature is in contrast to α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac helices, which require a minimum of six residues for helicity and 10 residues for stable secondary structure.39 Due to spectral overlap and the fact that properly parameterized computational programs were not accessible, we were not able to solve the solution-phase structures of the amide-linked homooligomers using NMR. And since crystal structures have not been forthcoming, direct structural comparisons between amide- and glycosidically-linked oligomers have not been possible until now.

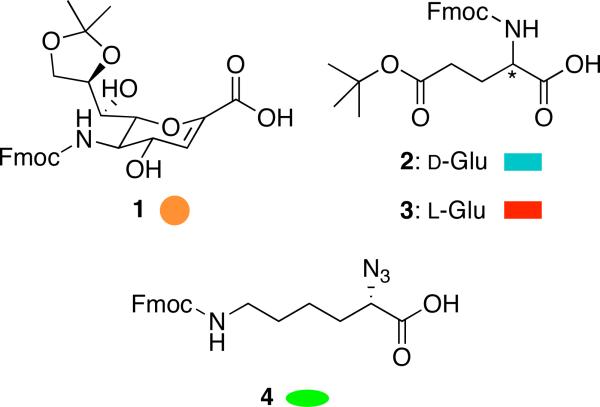

In an effort to address the problem of spectral overlap, we designed a series of heterooligomers composed of glutamic acid and a SAA analog of sialic acid known as Neu2en (Figure 2, 1). Neu2en was chosen as the SAA because earlier studies from our laboratory indicated that homooligomers composed of this building block were the most stable and synthetically accessible.42 Glutamic acid was chosen on the basis of its anionic charge at biological pH, which could serve as a surrogate for the carboxylates present in polymeric α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac. We reasoned that while the backbone structures of glycosidically- and amide-linked sialic acids may not be similar, perhaps the helices could be aligned on the basis of charge distribution.

Figure 2.

Amino acids used for constructing the α/δ hybrid peptides.

Results

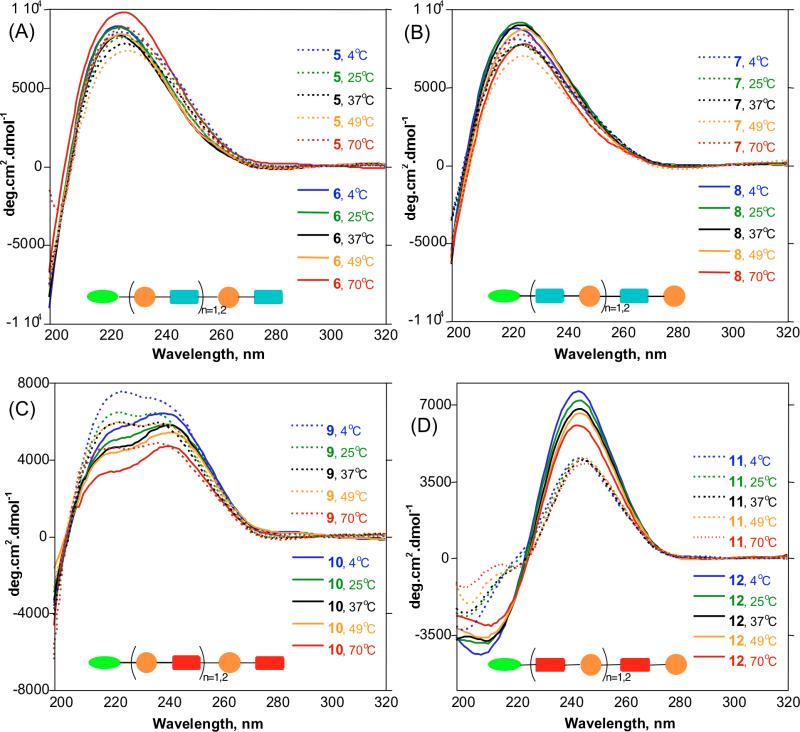

Only a few synthetic hybrid peptides that assume helices have been reported.14,43-45 In a particularly nice example reported by Gellman and co-workers, matched α/β pairs constructed from L-α-residues (Ala, Glu, Lys, Tyr), (S,S)-trans-2-aminocyclopentanecaboxylic acid, and (3R,4S)-trans-aminopyrrolidine-4-carboxylic acid were shown to adopt helical conformations in MeOH.46 Inspired by these findings, we designed four series of tetrameric and hexameric constructs made of alternating amino acid residues having either 1, 2 or 3 at the N-terminus (Figure 3). Fmoc-Neu2en 1 was synthesized following our previous method42 with slight modification to give an overall yield of 32% in eight steps (Supporting Information). Rink amide resin and BOP were used as solid support and coupling agent for SPPS, respectively, since we have previously established these to be optimal reagents.41,42 Fmoc-α-azido-ε-aminocaproic acid linker (N3Lys) 4 was prepared from Boc-Lys(Fmoc)-OH by Cu (II)-catalyzed NH2 to N3 interconversion at 92% yield.47

Figure 3.

Synthetic design of α/δ peptides derived from 1 and 2 or 3.

Oligomerization utilized Fmoc chemistry and commenced with coupling of 4 to the resin to prevent fraying of the C-terminus as well as to introduce the azide as a handle for future functionalization of the scaffold. In contrast to our previous SPPS of Neu5Ac oligomers that takes several hours for each coupling and deprotection step,42 we employed microwave technology to effect shorter coupling (5 min) and deprotection (3 min) times. The use of microwave energy is believed to prevent the growing peptide chain from aggregating,48 and this method has been successfully employed in the generation of a library of helical β-peptides.49 Fmoc was removed using 6% piperazine and iterative coupling and deprotection were implemented to build the oligomers according to the synthetic design. The peptides were cleaved with 30% TFA/CH2Cl2, concentrated in vacuo and purified by RP-C18 HPLC to furnish 22-39% overall yields of α,δ hybrid foldamers.

IR Monitoring of SPPS

Based upon our previous experience, we found that the Kaiser test50 can be ambiguous as a basis for monitoring the deprotection of 1 on bead. We opted to use IR spectroscopy to monitor the completion of each coupling and deprotection step by recording the spectrum of the bead and bound oligomers using attenuated total reflectance (ATR) techniques. Although several studies have been published using on-bead IR monitoring,51,52 we have discovered further use of our IR data. We found that we could use the distinct broad, strong IR absorption band at 1719 cm−1 due to the carbamate C=O of Fmoc as a useful marker for the extent of coupling and deprotection (Supporting Information). In addition, we could quantify the number of residues incorporated using the azide absorption at 2101 cm−1 as an internal standard. There is a linear correlation in the ratio of peak area integrations of azide versus amide as shown for 6 (Supporting Information). By plotting the azide/amide peak area integration of an oligomer bound to the bead and comparing it to the plot from one of our trials, we determined the number of residues of a bead-bound heterooligomer of known peptide sequence without going through a more tedious analytical process like mass spectrometry, which typically requires cleavage from the bead.

Conformational Studies by CD

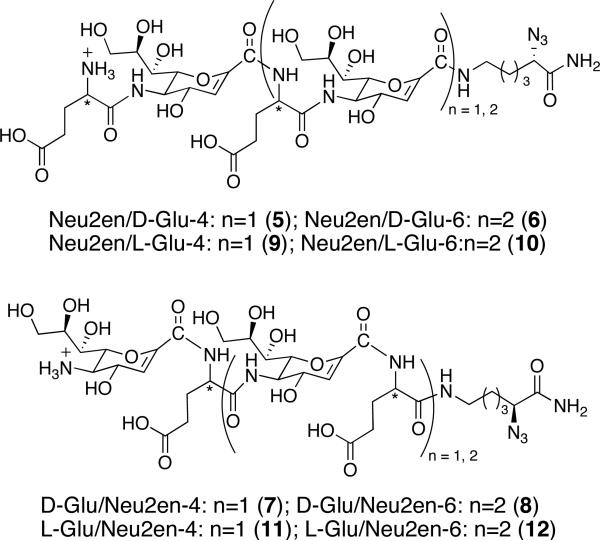

We probed the 2° structure of the α/δ hybrid peptides in PBS buffer by CD at pH 7.4 to mimic physiological conditions. Spectra were recorded at various temperatures from 4 to 70 °C. Molar ellipticities were divided by the number of 1 and Glu residues to normalize the contribution of each residue to the secondary structure of the oligomer, since the additivity of the residues is not linear and is dependent on the stability of the conformation assumed by the peptide.41 CD has been used to characterize solution phase 2° structures of peptides,53,54 and good correlation with crystal structure has been observed.55 We have also demonstrated by CD that unnatural amide-linked analogues of sialic acid form stable 2° structures in water.41,56

The CD profiles of 5-8 in Figures 4A and 4B show positive a Cotton effect centered at 223 nm of the amide region. Within these series, no significant differences in [θ]’s were observed by varying the length or temperature. This is reminiscent of unfolded α-peptides that have random behavior.57 The conjugated amide chromophore of 1 in 5-8 did not show a π to π* transition at longer wavelength, which further suggests that these compounds do not assume any stable conformation and are random coils in aqueous medium. Compounds 9-10 show unusual double positive Cotton effects that look as if the trough at 220 nm is flipped horizontally (Figure 4C). The intensity of the peak at 220 nm decreases with increasing length suggesting that interconversion between random and 2° structure may be occurring. We considered that this CD profile may be the average of the dynamic folding and unfolding behavior of 9 and 10 in aqueous solution, and may be indicative of weak H-bonds that are easily disrupted by water.

Figure 4.

CD spectra of α/δ peptides in PBS, pH 7.4 at different temperatures normalized per residue. (A) and (B) Spectra of 5 – 8 showing positive CD bands for A- and B-series at 223 nm indicating random coils. (C) Spectra of 9 and 10 showing an unusual double positive Cotton effect due to an unstable 2° structure. (D) Spectra of 11 and 12 showing a unique spectral signature distinct from typical amide band. Peak to trough analysis indicates increasing stability of 2° structure from tetramer to hexamer.

Figure 4D shows the CD spectra of 11 and 12 exhibiting Cotton effects at 202 and 245 nm for 11 and 209 and 243 nm for 12. These profiles are different from those previously observed for helical α- β-, or γ-peptides. The π→π* transition of the conjugated olefinic double bond of 1 displays a unique longer wavelength spectral signature. The intensity of these bands is dependent on oligomer length and temperature. Peak to trough analysis reveals increasing stability with length, and decreased peak intensity at higher temperatures (Table 1), the hexamer 12 being more stable than the tetramer 11. We interpreted these CD profiles to indicate that these constructs are matched and form ordered 2° structures in water.

Table 1.

Analyses of peak and trough of molar ellipticities of 11 and 12 indicate increase in 2° structure stability with length and decrease at higher temperatures.

| L-Glu/Neu2en-4 (11) | L-Glu-Neu2en-6 (12) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. (°C) | Peak Max | Peak Min | Peak - Trough | Peak Max | Peak Min | Peak - Trough |

| 4 | 4578.8 | −3244.0 | 7822.8 | 7596.4 | −4379.7 | 11976.1 |

| 25 | 4460.7 | −2694.0 | 7154.7 | 7167.3 | −3881.3 | 11048.6 |

| 37 | 4425.4 | −2536.7 | 6962.1 | 6749.0 | −3845.7 | 10594.7 |

| 49 | 4548.5 | −2093.1 | 6641.6 | 6538.2 | −3687.3 | 10225.5 |

| 70 | 4301.1 | −1334.0 | 5635.1 | 5982.5 | −3100.7 | 9083.2 |

Thermal Stability

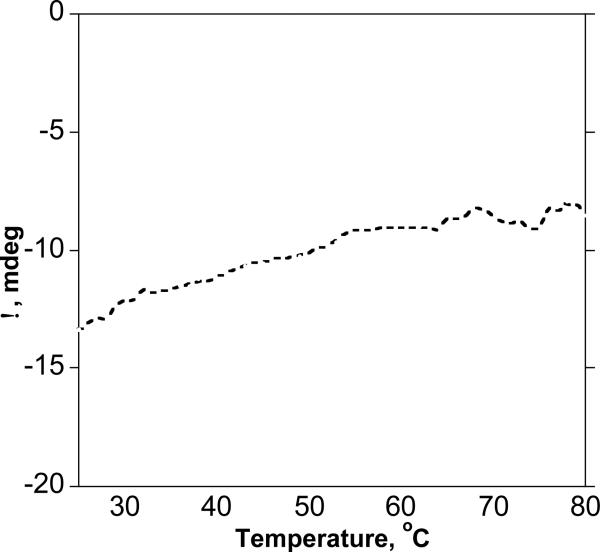

Typical CD patterns of proteins that possess stable 2° structures often show a sharp inflection point upon heating due to denaturation.58 We recorded the temperature-dependent CD spectrum of 12 to probe if its conformation is stabilized by cooperative folding processes due to stabilization by H-bonds between the amide NH and carbonyl oxygen of the backbone. Figure 5 shows a steady decrease in intensity for the Cotton effect at 209 nm that remains almost linear upon heating up to 80 °C, reflecting no breakup in the 2° structure. This non-cooperative mechanism has been observed in thermally stable α-helical peptides,59 as well as in helical β-peptides stabilized by staggering effects.60 We hypothesized that this non-cooperative behavior could be due to strong intramolecular H-bonding that stabilizes the secondary structure of 12.

Figure 5.

Variable temperature CD of 12 for the Cotton effect at 209 nm. No sharp inflection point was observed indicating no cooperative breakup of H-bonds.

NH/ND Exchange

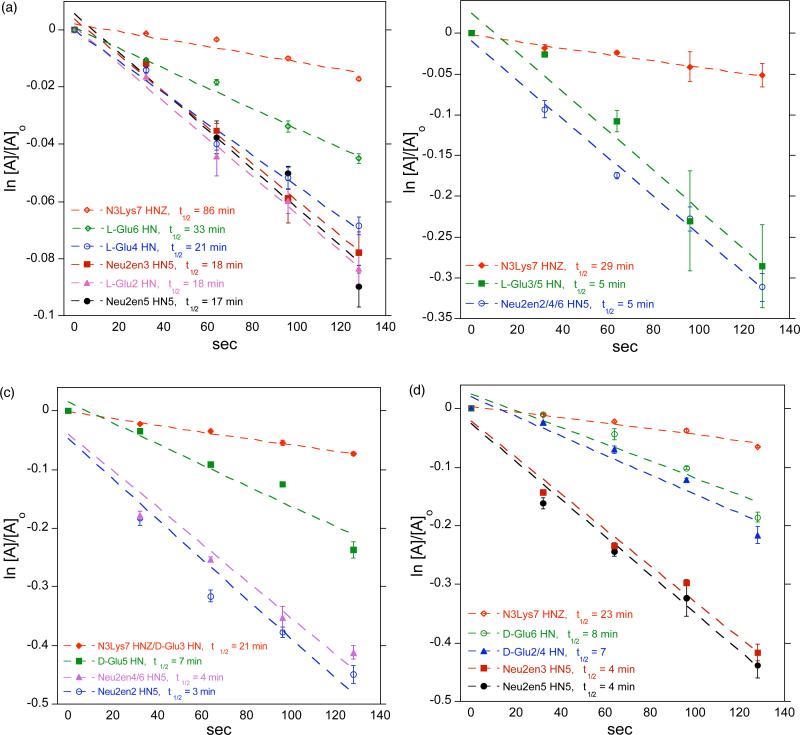

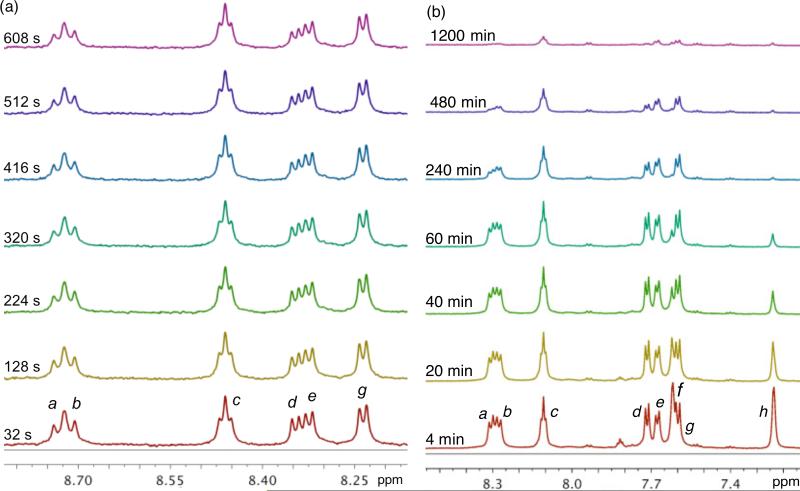

It has been demonstrated that slow NH/ND exchange rates are indicative of stable 2° structure in oligopeptides.5,41 We noticed during our initial 1H NMR studies that the H/D exchange of amide H in D2O is instantaneous at room temperature. Therefore, we opted to perform the NH/ND exchange study in D2O at 277 K to slow down the exchange at a rate that is observable on the NMR time scale. Spectra of 6, 8, 10, and 12 were recorded over time, the integration of the amide peaks were measured at each time point, and the half-life (t1/2) of NH/ND exchange was calculated based upon pseudo first order kinetics. The C-terminal amide hydrogens were completely exchanged prior to the acquisition of the first FID. This rapid exchange suggests that in aqueous solutions, the C-termini of these peptides are fully exposed to the solvent and do not form intramolecular H-bond. The internal amide NH resonances of 6, 8, and 10 showed large difference in exchange rates compared to 12 as a function of sequence and Glu configuration. Figure 6 shows the long t1/2 of the amide H of 12 at 17 – 86 min, suggesting a 2° structure stabilized by intramolecular H-bond. The amide H of 6 and 8 have relatively short t1/2 of 3 – 8 min while those of 10 have t1/2 of 5 min that are equivalent to about three to six times the exchange rate of 12 that suggest unfolded peptide chains. We also performed the NH/ND exchange study in DMSO-d6 solution at 298 K with the addition 10% D2O (Supporting Information) and observed consistent fast relative deuterium exchange rates of 6 and 8 to 12, while 10 showed twice the exchange rate of 12. Figure 7 includes a stack plot of 1H NMR spectra of 12 in (a) D2O and (b) DMSO-d6 + D2O recorded at different time points, showing the differential deuterium exchange of amide protons. Noteworthy is the fact that in DMSO-d6, a significant amount of NH amides of Glu4 (10%), Glu6 (9%), and N3Lys (14%) in 12 remain unexchanged after 20 hrs. This relatively slow exchange suggests a strong intra-residue H-bonding that is responsible for the stable 2° structure of 12. We also observed that NH amides of 12 are more dispersed and distinct from each other as compared to 6, 8, and 10 (Supporting Information). These findings strongly corroborate our CD observations indicating the stable 2° of 12.

Figure 6.

Pseudo first order rate plots showing the long t1/2 of H-bonded amide protons of 12 (a) indicating a 2° structure stabilized by intramolecular amide H-bonds. The amide H of 6 (c) and 8 (d) have relatively shorter t1/2 of 3 – 8 min while those of 10 (b) have t1/2 of 5 min that are equivalent to about three to six times the NH/ND exchange rate of 12 suggesting unfolded peptide chain.

Figure 7.

Stack plot of 1H NMR spectra of 12 in (a) D2O, 277 K and (b) DMSO-d6, 298 K at different times after addition of D2O, 600 MHz. a and b: HN5 of Neu2en3 and 5; c, f and h: HNZ, H2 and H1 of N3Lys7, respectively; d, e and f: HN of L-Glu2, 4, and 6, respectively.

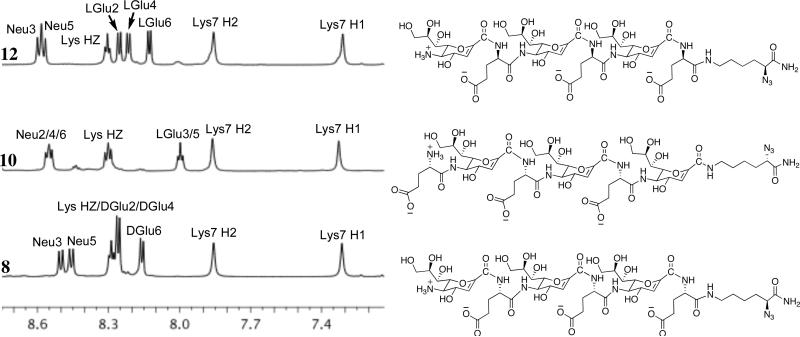

Conformational Studies by NMR

Detailed 1H and 2-D homonuclear ROESY NMR studies were performed on 8, 10, and 12 in 9:1 H2O/D2O to elucidate their structures in solution. Although the kinetics and CD profiles of 8 indicate a random coil, this oligomer was included in the NMR conformational analysis to demonstrate the impact of amino acid configuration on 2° structure stability, while 10 was chosen to probe sequence specificity. Figure 8 is a stack plot of the amide region of the 1H NMR spectra for 8, 10, and 12 and demonstrates the sequence and configuration dependence of their 2° structures. The greater chemical shift dispersion of Glu amide resonances of 12 suggests the presence of 2° structure. This observation is in agreement with our findings in CD spectroscopy. The wider dispersion of amide 1H chemical shifts for 12 is in contrast to overlapping amide resonance peaks found in 8 and 10, suggesting that 8 and 10 lack ordered structure, which is in agreement with their random coil conformation observed by CD.

Figure 8.

Stack plot of the amide regions from the 1H NMR spectra of 8, 10, and 12 in 9:1 H2O/D2O, 600 MHz, 298 K. (Neu = Neu2en; Glu = glutamic acid; Lys = N3Lys)

ROESY spectra were recorded for 8, 10, and 12 to analyze their three-dimensional main chain conformations. Initial 1H NMR studies were performed on the tetramers to differentiate terminal and internal residues and facilitate the assignment of resonances for the hexamers (Supporting Information). A preliminary ROESY experiment was performed on L-Glu/Neu2en dimer to differentiate between intra- and inter-residue NOE of Neu2en. ROESY cross peaks were calibrated into distance restraints for solution phase structure calculations using restrained molecular dynamics and simulated annealing in

XPLOR-NIH.61 The effect of solvent and solvent screening of electrostatic charges in the X-PLOR structure calculation was implemented using the 1/R dielectric option for the electrostatic energy function in XPLOR (Supporting Information). The parameter and topology files for Neu2en and N3Lys were generated by modifying previously known data for Neu5Ac and L-Lys, and the azide parameters were obtained from previously reported ab initio calculations.62 The phi and psi dihedral restraints for L-Glu NH were estimated from the chemical shift index63 and from empirical values of 3JHN,Hα.64 The lowest energy structures without NOE violations were selected, averaged and energy minimized.

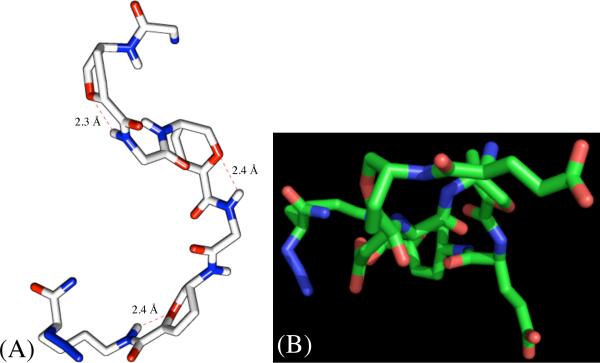

A number of ROESY cross peaks for 12 were assigned that help define its overall main chain conformation. In particular, the most prominent long range ROESY cross peaks include the recurring Neu2en-H8(i)→L-Glu-HN(i+1), Neu2en-H3(i)→Neu2en-H9’(i+2), L-Glu2-Hα→L-Glu4-HN, and N3Lys7-H2→L-Glu4-Hγ (Figure 9). The secondary structure of 12 in water is defined by 76 NOE restraints deduced from the ROESY experiment.

Figure 9.

Crucial long range nOe's for 12 extracted from the ROESY spectra (9:1 H2O/D2O), Neu2en-H8(i)→L-Glu HN(i+1) nOe's are in blue, Neu2en-H3(i)→Neu2en-H9’(i+2) are in brown, L-Glu2-Hα→L-Glu4-HN is in green, and N3Lys7-H2→L-Glu4-Hγ is in black.

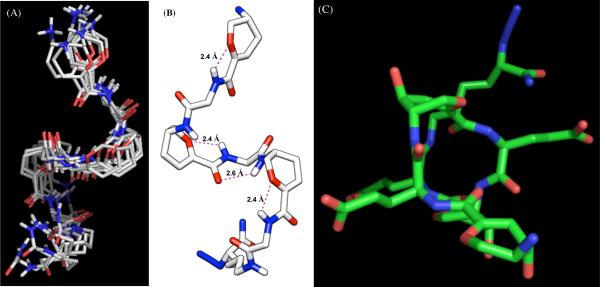

A total of 25 low energy structures were selected, and a side view of a bundle of seven is shown in Figure 10A. The backbone rmsd of 0.699 Å and a rmsd of 1.422 Å for all non-H atoms indicate good convergence of the calculated structures (Table 2). Figure 10B is the side view of the averaged, minimized structure of 12. There are three recurring H-bonds between L-Glu HN and Neu2en pyranose ring oxygen having the same bond lengths of 2.4 Å. This interaction appears to be unique to sialic acid and, as to our knowledge, this H-bond pattern has not been reported in previous SAA studies. A classical C=O•••H-N at 2.6 Å was also found at the center of the peptide chain between Neu2en-3 and Neu2en-5, which significantly contributed to the stability of 12. Although it was previously reported that “nearest-neighbor” five- or seven-membered ring H-bonds are unfavorable for α and 310 helices of proteins,1 our novel α/δ hybrid peptides do not obey this behavior and form a seven-membered ring. Furthermore, there is a direct correlation between these H-bonds and the slow NH/ND exchange rates that we observed for 12 in the kinetic studies.

Figure 10.

(A) A bundle of selected seven low-energy NMR derived structures of foldamer 12 calculated using XPLOR-NIH using NOE restraints generated from ROESY spectra in 9:1 H2O/D2O at 500 ms mixing time, 600 MHz, 298 K. (B) Side view of the averaged and minimized solution phase NMR structure of 12 showing the intra-residue rin g O→H-N and C=O→H-N bonds. (C) Top view from the N-terminus showing fully extended and solvated Glu side chains (all H have been omitted for clarity).

Table 2.

Properties of calculated 25 lowest energy structures of 10 and 12.

| Neu2en/L-Glu-6 (10) | L-Glu/Neu2en-6 (12) | |

|---|---|---|

| r.m.s.d. for Neu2en and L-Glu backbone, Å | 0.867 ±0.384 | 0.699 ±0.220 |

| r.m.s.d. for Non-H atoms, including side chains, Å | 1.520 ±0.375 | 1.422 ±0.280 |

| Inter-residue amide H bonds | 3 | 4 |

| Total Number of NOEs | 82 | 76 |

| Final Energy, kcal/mol | 352.289 | 354.169 |

The top view of 12 from the N-terminus (Figure 10C) shows that the upfield C-terminal NH2 of N3Lys, observed as singlets at 7.25 and 7.64 ppm in DMSO-d6 (Supporting Information), are solvent exposed which accounts for their fast deuterium exchange, while the azide is oriented outwards making it accessible for future functionalization with relevant small molecule ligands using 1,2-dipolar cycloaddition. The Glu side chain carboxylates are fully solvated, and each succeeding Glu residue is oriented opposite from the previous one, separated by an average distance of 14.1 Å while Glu2 and Glu6 carboxylates are 11.8 Å apart. This satisfies the electrostatic stabilization due to maximum separation of negative charges, which is consistent with a model for αNeu5Ac(2→8)αNeu5Ac octamer calculated using complete relaxation matrix analysis.40

The NMR solution phase structure of 10 was studied using the same approach above for 12. Figure 11 is the minimized average structure with a backbone rmsd of 0.867 ±0.384 and rmsd of 1.520 ±0.375 for non-H atoms. This structure clearly shows a lack of defined helical pattern as well as less ordered arrangement of L-Glu side chains. A total of three H-bonds were found between L-Glu3, L-Glu5 HN, and N3Lys7 epsilon HN and pyranose ring O. Oligomer 10 lacks the classical backbone H-bond found in 12, which demonstrates the significance of sequence specificity for establishing a stable 2° structure.

Figure 11.

Minimized average structure of 10 showing a lack of defined helical pattern as well as less ordered arrangement of L-Glu side chains (OH and aliphatic H have been omitted for clarity): (A) side view; (B) top-view.

Fewer H-bonds account for the instability of 10 suggesting that it interconverts between random and folded structures, which is in agreement with the CD and kinetics studies. The NMR solution phase structure of 8 was also analyzed, but did not yield defined conformations: the low energy structures do not converge to a single, preferred conformation. However, an overlay of 25 low energy structures showed extended, random coils (Supporting Information), which is in agreement with the CD and kinetics data. No further conformational analysis was undertaken for 8. The instability of the conformation of 10 and the absence of a defined structure in 8 clearly indicate that the 2° structure of Neu2en/Glu peptides is defined by the appropriate peptide sequence and the configuration of L-Glu that is found in both 11 and 12. The results suggest that all L-α-amino acids will have the matched configuration with Neu2en, which paves the way for the design and construction of neutral, cationic, or zwitterionic Neu5Ac-based foldamers.

Comparisons of α-(2-8)Neu5Ac Polymer and Neu2en/L-Glu Foldamer Conformations

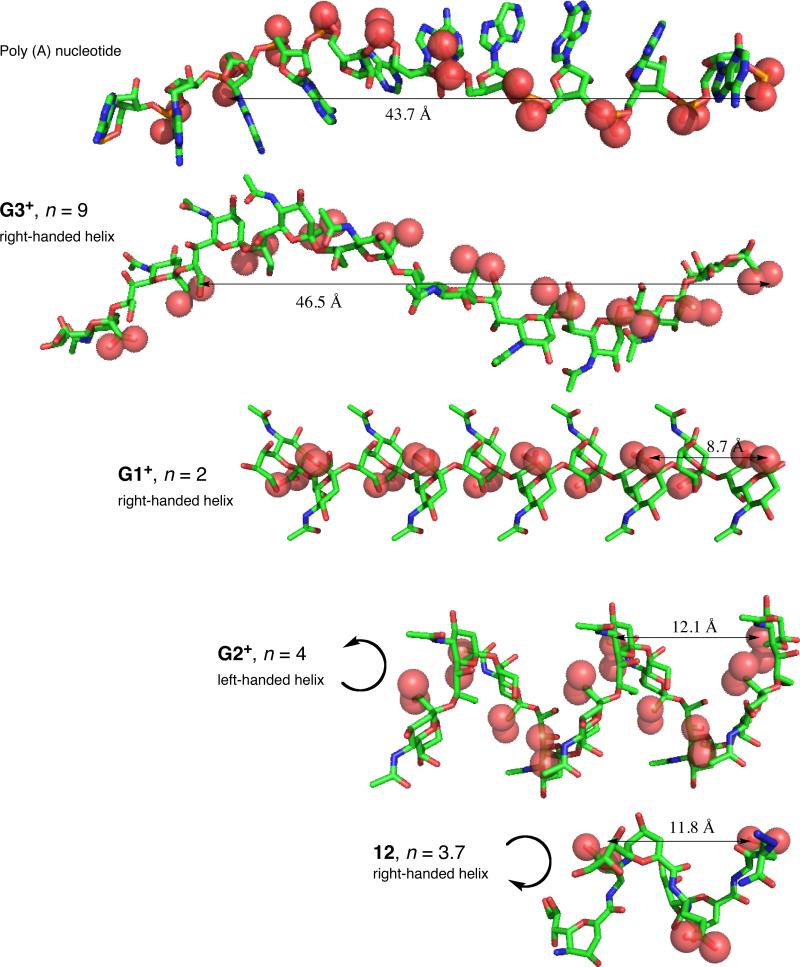

Conformational studies of α-(2-8)Neu5Ac polymer indicate that it exists primarily as a random coil with localized regions of helicity. A human monoclonal macroglobulin IgMNOV with specificity for α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac polymer has been identified.65 This antibody also shows cross-reactivity with polynucleotides and denatured DNA, which bind to the same site that recognizes α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac polymer.65 NMR investigations of the helical regions of α(2→8)Neu5Ac polymer resulted in the identification of three major conformers differing in the number of residues per turn (n) and the chirality of the helix. The G1+ and G3+ conformers are right-handed helices of n=2 and 9, respectively, while G2+ is left handed with n=4.39 Comparisons between the G3+ helical epitope and the structure of poly (A) nucleotide showed remarkable similarities most notably in the positioning of the charged functional groups.39 This finding led to the hypothesis that antibody cross-reactivity arises from the appropriate spatial arrangement of negative charge.65 On the basis of this hypothesis, we have explored the possibility of creating stable Neu2en/Glu foldamers that can serve as novel scaffolds for carboxylate display. To that end, comparisons of 12 with the predicted conformations of α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac polymer indicate that the carboxylate periodicity of 12 closely maps to the G2+ helix with half the charge density (Figure 12). However, the G2+ helix is left-handed whereas 12 is right-handed. Furthermore, the n of 12 is much smaller than the extended helical antigenic G3+ conformer of poly-α(2→8)Neu5Ac leading to the prediction that 12 would not be cross-reactive with IgMNOV based on this conformational difference.21

Figure 12.

Comparison of 12 with the G1+, G2+ and G3+ conformers of poly-α(2→8)Neu5Ac reveals a similar helical conformation and periodicity of carboxylate groups with half the charge frequency and opposite handedness of 12 to G2+ (H atoms were omitted for clarity).

Conclusions

We have constructed a novel class of functionalizable Neu5Ac-derived, water-soluble α/δ hybrid peptides using microwave-assisted SPPS. Constructs made from 1 and 3 (11, 12) are matched and form stable 2° structures in aqueous solution while those from 1 and 2 (5-8) are mismatched and are random coils. We have shown here that stable 2° structure is affected by both the configuration of Glu and the peptide sequence. Our findings indicate that 12 is not only stabilized by traditional C=O•••H-N backbone H-bonding but by a net effect of factors that include the following: (a) inherent rigidity of the flattened pyranose ring and the conjugated amide linkage, (b) appropriate configuration and position of Glu in the peptide sequence, (c) H-bond between L-Glu HN and Neu2en ring O, and (d) minimized electrostatic repulsion between the L-Glu side chains. Since the synthesis of these peptides is modular, we can tailor the length, as well as the charge, by replacing Glu to match the size and charge of the intended target. We anticipate that the design process will be greatly facilitated now that we have access to appropriately parameterized computational programs that can be used to predict the conformations of modified structures.

This report has focused on establishing fundamental principles for scaffold design with the longterm objective of making immunogenic surrogates of α(2→8)Neu5Ac polymer. One target antibody, IgMNOV, recognizes the G3+ conformational epitope of α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac polymer. However, given the conformational flexibility of the Neu5Ac polymer, it is conceivable that antibodies against alternative conformations of α(2→8)Neu5Ac polymer (e.g. G1+ or G2+) could be elicited upon exposure to antigenic epitopes. There are difficulties associated with using α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac polymer to elicit antibody production because the polymer is susceptible to enzymatic degradation by neuraminidase and it is poorly immunogenic due to its role in human embryonic development. An alternative approach to producing antibodies against conformational epitopes of α-(2,8)-linked Neu5Ac would be to develop enzymatically stable foldamers such as 12 that may be capable of eliciting a crossreactive antibody response. The studies outlined in this report establish a viable platform for synthesizing and designing foldamers with this intended purpose. Our future plans include studies to determine the plasma stability of these foldamers as well as their immunogenic properties.

Experimental Section

Experimental procedures for the synthesis of 1 and 4 are fully described in the Supporting Information.

Solid Phase Synthesis of α/δ hybrid peptides

Typically, 100 mg of Fmoc-Rink resin (0.5 mmol/g) was swelled in DMF for 2 h and drained. Every coupling and Fmoc deprotection step was monitored by IR spectroscopy as described below. Fmoc deprotection required 6% piperazine in NMP using an open polypropylene tube with fritted disc and microwave irradiation in a microwave reactor equipped with fiber optic temperature sensor. Reaction conditions were as follows: power = 30 W, ramp time = 1 min, hold time = 3 min, temperature = 75 °C. The resin was washed with MeOH (2 mL × 3) and CH2Cl2 (2mL × 3). N3Lys (4) (86.4 mg, 2 eq), BOP (97 mg, 2 eq), DIPEA (57 mg, 4 eq) and 2 mL NMP were added to the resin and mixed and allowed to sit at room temperature for 10 min. Microwave coupling conditions are the same as in the deprotection, except for the 5 min hold time, and the loading process was repeated using 1 eq of 4, 1 eq of BOP and 4 eq of DIPEA to ensure complete loading. The succeeding coupling reactions were performed using 3 or 1, followed by iterative deprotection and coupling steps between incorporation of amino acid. The oligomer was cleaved from the resin with 30% TFA in CH2Cl2 (5 mL × 30 min agitation × 5), the filtrates were pooled, concentrated in vacuo, diluted in 5 mL H2O, and lyophilized. This process also hydrolyzed the isopropylidene of 1 as well as the t-butyl ester of Glu. The crude peptide was purified by reverse phase HPLC (RP-C18, 10×250 mm; 5-50% aqueous MeOH with 0.1% TFA) with detection set at 225 and 260 nm. Eluates were concentrated and lyophilized to yield white, fluffy solid TFA salt of the peptide.

L-Glu/Neu2en-6 (12)

obtained in 22% purified yield. 1H NMR (D2O, 600 MHz): d 5.97 (d, 1H, J = 3.0 Hz, H3-1), 5.92 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H3-3/5), 4.68 (dd, 1H, J = 9.0, 3.0 Hz, H4-1), 4.65 (dd, 1H, J = 10.2, 1.8 Hz, H6-1), 4.57 (dd, 2H, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, H4-3/5), 4.54 (dd, 1H, J = 5.4, 3.6 Hz, Hα-2), 4.53 (dd, 1H, J = 5.4, 3.6 Hz, Hα-4), 4.45 (dd, 2H, J = 10.8, 1.8 Hz, H6-3/5), 4.45 (dd, 1H, J = 6.6, 3.6 Hz, Hα-6), 4.21 (dd, 1H, J = 9.6, 3.0 Hz, H5-3), 4.19 (dd, 1H, J = 9.0, 3.0 Hz, H5-5), 4.15 (dd, 1H, J = 7.8, 6.0 Hz, Hα-7), 4.09 (ddd, 1H, J = 9.0, 5.4, 3.0 Hz, H8-1), 4.02 (ddd, 1H, J = 12.6, 6.6, 2.4 Hz, H8-3), 4.01 (ddd, 1H, J = 12.6, 6.6, 2.4 Hz, H8-5), 3.95 (dd, 1H, J = 12.0, 3.0 Hz, H9’-1), 3.92 (dd, 2H, J = 10.8, 2.4 Hz, H9’-3/5), 3.92 (dd, 1H, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, H7-1), 3.82 (dd, 1H, J = 12.0, 6.0 Hz, H9-1), 3.73 (dd, 2H, J = 9.0, 2.4 Hz, H7-3/5), 3.72 (dd, 2H, J = 12.0, 6.0 Hz, H9-3/5), 3.66 (dd, 1H, J = 10.2, 9.0 Hz, H5-1), 3.31-3.21 (m, 2H, Hε-7), 2.59 (dd, 3H, J = 7.2, 7.2 Hz, Hγ’-2/4/6), 2.54 (dd, 3H, J = 7.2, 7.2 Hz, Hγ-2/4/6), 2.29-2.09 (m, 6H, Hβ-2/4/6), 1.91-1.79 (m, 2H, Hβ-7), 1.64-1.55 (m, 2H, Hδ-7), 1.44 (p, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz, Hγ-7). 13C NMR (D2O, 150 MHz): d 180.2, 180.1, 178.4, 176.5, 175.6, 166.5, 166.4, 165.9, 148.0, 112.1, 111.0, 79.2, 78.0, 72.8, 70.8, 70.6, 69.8, 67.6, 66.1, 66.0, 65.9, 65.5, 56.4, 56.3, 53.7, 52.9, 41.9, 33.8, 32.9, 30.7, 29.1, 29.0, 24.8. MALDI-TOFMS: [M + Na+] calcd for C48H73N11O28Na+, 1274.4518; found, 1274.452.

Other α/δ-peptides were prepared by the same method as described above and their characterization data are found in the Supporting Information.

IR Spectroscopy

The washed resin containing the growing peptide chain was dried under suction in a manifold. Two to three beads were taken, pressed on top of the ZnSe-diamond crystal of the ATR plate, and the spectrum recorded. The carbamate and azide absorption bands were monitored at 1719 and 2101 cm−1, respectively. Absorbance peak area integration was done using a commercial IR software, and the ratio of amide/azide peak areas of both Fmoc-protected and deprotected peptides were plotted versus oligomer length.

Circular Dichroism

Peptides were prepared at 0.5 mg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4. Spectra were recorded in a 1 mm path length quartz cuvette with PBS as a blank at five temperatures: 4, 25, 37, 49, and 70 °C. Five scans were obtained and averaged for each sample from 320 to 198 nm with data points taken every 1.0 nm. All molar ellipticity values were normalized by dividing by the number of 1 and Glu residues in the oligomer. For thermal stability experiment of 12, the ellipticity at 209 nm was monitored as a function of temperature. Data were collected from 25 to 80 °C in triplicate and averaged for every 1° temperature increment.

Amide NH/ND Exchange

Samples were dissolved in (a) D2O, pD 5.5 and (b) DMSO-d6 followed by the addition of 10% D2O by volume. 1H NMR spectra were collected on a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer at 277 K, 16 scans each at 32 s interval for the D2O solution while the DMSO-d6 solution was studied at 298 K, 64 scans each at 4 min interval. The pseudo first order kinetics and half life (t1/2) of amide NH was calculated using the equations ln [A]/[A]o = -kt and t1/2 = ln 2/k, where [A] = peak area integration at time = t ; [A]o = peak area integration at time = 0.

ROESY NMR and Solution Phase Structure Calculations

The peptides were dissolved in 0.6 mL of H2O/D2O (9:1) at a concentration of 3.5 – 5 mM, pH 5.5. All ROESY experiments were performed at 298 K on a 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm cryoprobe. Water suppression was achieved by WATERGATE technique.66 ROESY spectra were initially recorded at 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ms mixing times, and we found 500 ms to be optimal. All data were recorded using Bruker TopSpin and the ROESY cross-peak volumes in the contour plot were measured using MestReNova software. Restrained molecular dynamics and simulated annealing calculations were performed using the protocol of XPLOR-NIH61 v.2.15 with initial temperature set at 1000 K with 6000 heating and 3000 cooling steps, and incorporated the distance and dihedral angle restraints. As distance restraints, the parameters extracted from ROESY experiments were categorized into three: strong, medium, and weak with 2.9 Å, 3.3 Å and 5.0 Å, respectively as upper bond distance limits. The phi and psi dihedral angle restraints for Glu were derived from empirical data for 3JHN,Hα and chemical shift indices of α-C, α-H and amide C and were assigned the values of −120.0 ±30.0 and 130.0 ±30.0, respectively.63,64 Parameter and topology files for Neu2en and N3Lys were generated by modifying previously known data for Neu5Ac and L-Lys,61 and the azide parameters were obtained from previously reported ab initio calculations.62 The calculations were looped to produce 100 structures, the lowest energy structures without NOE violations were selected, averaged, and energy minimized to generate the final structure. Visualization was done using MacPyMOL67 and UCSF Chimera.68

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. J.S. DeRopp is acknowledged for his help in WATERGATE ROESY experiments. The UC Davis NMR Award to J.G.H. is also acknowledged. The coordinates for poly−α(2→8)Neu5Ac conformers were obtained through the generosity of Dr. J.R. Brisson (NRC, Canada). This research was supported by the NSF Grant CHE-0518010 and NIH EY012347. NSF Grants CHE0443516 and DBI0079461 provided funding for the 600 MHz NMR spectrometers used in this project.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details, 1H NMR, MALDI TOF-MS, IR, and ROESY spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gellman SH. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frackenpohl J, Arvidsson PI, Schreiber JV, Seebach D. Chem Bio Chem. 2001;2:445–455. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010601)2:6<445::aid-cbic445>3.3.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Disney MD, Hook DF, Namoto K, Seeberger PH, Seebach D. Chem. Biodiv. 2005;2:1624–1634. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200590132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seebach D, Abele S, Gademann K, Guichard G, Hintermann T, Jaun B, Matthews JL, Schreiber JV. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1998;81:932–982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appella DH, Christianson LA, Karle IL, Powell DR, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:13071–13072. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peelen TJ, Chi Y, English EP, Gellman SH. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4411–4414. doi: 10.1021/ol0483293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Espinosa JF, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4821–4822. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seebach D, Hook DF, Glattli A. Biopolymers. 2006;84:23–37. doi: 10.1002/bip.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanessian S, Luo X, Schaum R, Michnick S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:8569–8570. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MD, Claridge TDW, Tranter GE, Sansom MSP, Fleet GW. J. Chem. Commun. 1998;18:2041–2042. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman JL, Petersson EJ, Daniels DS, Qiu JX, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14746–14751. doi: 10.1021/ja0754002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horne WS, Price JL, Gellman SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:9151–9156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Som A, Vemparala S, Ivanov I, Tew GN. Biopolymers. 2008;90:83–93. doi: 10.1002/bip.20970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitt MA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6848–6849. doi: 10.1021/ja048546z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadowsky JD, Fairlie WD, Hadley EB, Lee HS, Umezawa N, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Wang SM, Huang DCS, Tomita Y, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:139–154. doi: 10.1021/ja0662523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kritzer JA, Stephens OM, Guarracino DA, Reznik SK, Schepartz A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;13:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akkarawongsa R, Potocky TB, English EP, Gellman SH, Brandt CR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2120–2129. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01424-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephens OM, Kim S, Welch BD, Hodson ME, Kay MS, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13126–13127. doi: 10.1021/ja053444+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bautista AD, Craig CJ, Harker EA, Schepartz A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Roedern EG, Kessler H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1994;33:687–689. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varki A. Trends Mol. Med. 2008;14:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham BA, Hemperly JJ, Murray BA, Prediger EA, Brackenbury R, Edelman GM. Science. 1987;236:799–806. doi: 10.1126/science.3576199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutishauser U, Acheson A, Hall AK, Mann DM, Sunshine J. Science. 1988;240:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.3281256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann S, Sorkin BC, White PC, Brackenbury R, Mailhammer R, Rutishauser U, Cunningham BA, Edelman GM. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:7720–7729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vimr ER, McCoy RD, Vollger HF, Wilkison NC, Troy FA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Asci, USA. 1984;81:1971–1975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livingston BD, McCoy RD, Jacobs JL, Glick MC, Troy FA. J. Biol. Chem. 1988:9443–9448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seidenfaden R, Krauter A, Schertzinger F, Gerardy-Schahn R, Hildebrandt H. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003:5908–5918. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5908-5918.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dall'Olio F, Chiricolo M. Glycoconjugate J. 2001;18:841–850. doi: 10.1023/a:1022288022969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ledermann JA, Pasini F, Olabiran Y, Pelosi G. Int. J. Cancer. Supplement. 1994;8:49–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theodosis DT, Bonhomme R, Vitiello S, Rougon G, Poulain DA. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:10228–10236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10228.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutishauser U. J. Cell. Biochem. 1998:304–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19980901)70:3<304::aid-jcb3>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storms SD, Rutishauser UJ. Biol. Chem. 1998:27124–27129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruses JL, Rutishauser U. J. Cell. Biol. 1998;140:1177–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seki T, Rutishauser U. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:3757–3766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03757.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risseeuw MDP, Overhand M, Fleet GWJ, Simone MI. Tetrahedron Asymm. 2007;18:2001–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schweizer F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;41:230–253. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gruner SAW, Locardi E, Lohof E, Kessler H. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:491–514. doi: 10.1021/cr0004409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandrasekhar S, Reddy MS, Jagadeesh B, Prabhakar A, Ramana Rao MHV, Jagannadh B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13586–13587. doi: 10.1021/ja0467667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brisson JR, Baumann H, Imberty A, Perez S, Jennings HJ. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4996–5004. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamasaki R, Bacon B. Biochemistry. 1991;30:851–857. doi: 10.1021/bi00217a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szabo L, Smith BL, McReynolds KD, Parrill AL, Morris ER, Gervay J. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gregar TQ, Gervay-Hague J. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:1001–1009. doi: 10.1021/jo035312+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Pol S, Zorn C, Klein CD, Zerbe O, Reiser O. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:511–514. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma GVM, Nagendar P, Jayaprakash P, Krishna PR, Ramakrishna KVS, Kunwar AC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5878–5882. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitt MA, Choi SH, Guzei IA, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4538–4539. doi: 10.1021/ja060281w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayen A, Schmitt MA, Ngassa FN, Thomasson KA, Gellman SH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:505–510. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nyffeler PT, Liang C-H, Koeller KM, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10773–10778. doi: 10.1021/ja0264605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collins JM, Leadbeater NE. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:1141–1150. doi: 10.1039/b617084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murray JK, Farooqi B, Sadowsky JD, Scalf M, Freund WA, Smith LM, Chen J, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13271–13280. doi: 10.1021/ja052733v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaiser E, Colescat RL, Bossinge CD, Cook PI. Anal. Biochem. 1970;34:595. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan B. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:621–630. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huber W, Bubendorf A, Grieder A, Obrecht D. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1999;393:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicoll AJ, Weston CJ, Cureton C, Ludwig C, Dancea F, Spencer N, Smart OS, Gunther UL, Allemann RK. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:4310–4315. doi: 10.1039/b513891d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawamura SI, Morita T, Kimura S. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2006;7:544–551. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Appella DH, Christianson LA, Klein DA, Powell DR, Huang XL, Barchi JJ, Gellman SH. Nature. 1997;387:381–384. doi: 10.1038/387381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McReynolds KD, Gervay-Hague J. Tetrahedron Asymm. 2000;11:337–362. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woody RE. In: Circular Dichroism and the Conformational Analysis of Biomolecules. Fasman GD, editor. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. pp. 25–67. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benjwal S, Verma S, Rohm KH, Gursky O. Protein Sci. 2006;15:635–639. doi: 10.1110/ps.051917406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patgiri A, Jochim AL, Arora PS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1289–1300. doi: 10.1021/ar700264k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gademann K, Jaun B, Seebach D, Perozzo R, Scapozza L, Folkers G. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1999;82:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sklenak S, Gatial A, Biskupic S. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 1997;397:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1647–1651. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuboniwa H, Grzesiek S, Delaglio F, Bax AJ. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:871–878. doi: 10.1007/BF00398416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kabat EA, Liao J, Osserman EF, Gamian A, Michon F, Jennings HJ. J. Exp. Med. 1988;168:699–711. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piotto M, Saudek V, Sklenar V. J. Biomol. NMR. 1992;2:661–665. doi: 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DeLano WL. DeLano Scientific LLC; Palo Alto, CA, USA: p. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.