Abstract

This analysis uses data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to examine whether veteran and disability statuses are jointly associated with household-level poverty and material hardship among older adults. Compared to households that do not include a person with a disability or veteran, disabled non-veteran households are more likely to be in poverty and to experience home hardship, medical hardship, and bill-paying hardship. Disabled veteran households are not significantly different in terms of poverty, but exhibit the highest odds of home hardship, medical hardship, bill-paying hardship, and food insufficiency. The implications for social work practice are discussed.

Keywords: disability, veteran status, poverty, material hardship

INTRODUCTION

Among current cohorts of older adults, the majority of men served in the military at some point during the middle of the twentieth century (Wilmoth & London 2011). Military service is particularly prevalent among older cohorts of men who served in World War II and the Korean War; in 2010, almost 9.3 million men age 65 years and older were veterans, which represents approximately 50% of men in that age group (U.S. Census Bureau 2012). The high prevalence of military service in these cohorts, coupled with the fact that most studies of older adults do not explicitly take the potential effects of military service into account, has led some researchers to claim that military service is a “hidden variable” in aging and life-course research (Settersten & Paterson 2006; Spiro, Schnurr, & Aldwin 1994). This lack of attention to veteran status in aging and life course research overall, as well as the preponderance of veteran-only studies in the literature, is problematic given that many later-life outcomes, including economic well-being, may be influenced by prior military service (Wilmoth & London 2013).

Recent research indicates that veteran status and work-limiting disability interactively influence economic well-being among working-aged households that only include adults younger than 65 (Heflin, Wilmoth & London 2012; London, Heflin & Wilmoth 2011). However, the moderating effect of veteran status on the relationship between disability and economic well-being might operate differently among older adult households. Although the prevalence of various types of disability is higher among the older adult population, older adults have access to social safety nets that could reduce the risk of poverty and material hardship. The majority of older adults have access to income through Social Security, the Supplemental Security Program provides additional support to low-income elders, and the impact of disabling health conditions on older adults’ economic well-being might be minimized by the health care coverage provided by Medicare and Medicaid. Additionally, career veterans and veterans with service-connected disability ratings have access to an additional layer of support through various programs administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs (Street & Hoffman 2013; Wilmoth & London 2011), which could place them at an economic advantage relative to non-veterans. To date, no study of which we are aware has considered the nexus of veteran status, disability, poverty, and material hardship among households that include older adults.

Social workers know that means-testing based on poverty criteria is often used to determine access to programs and services, including those offered through the aging network, and understand how material hardship affects individual- and household-level well-being independent of poverty. However, they might not be as attuned to the unique needs of older adult households, in particular the fact that many of these households contain persons who are disabled and/or are veterans who served during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. This is a population with which social workers will increasingly work as the proportion of the population that is elderly continues to grow (Monahan and Brown 2013). Therefore, it is essential that social workers at all levels of practice recognize the salience of disability and prior military service to the lives of older adults and their family members. For social workers practicing at the micro level, this information can facilitate the coordination of services for older individuals and their families. This information can also enhance community organizing efforts and educational outreach designed by social workers at the mezzo level. At the macro level, social workers need information that will support advocacy aimed at improving the effectiveness of old age policies that provide an essential safety net to individuals and families experiencing economic deprivation.

In an effort to address an important gap in the literature and inform social work practice, we use pooled data from the 2001 and 2004 SIPP to examine the joint influence of veteran and disability status on poverty and material hardship among older adult households. Specifically, we examine the extent to which the veteran and disability statuses of members of older adult households are associated with the odds of household-level poverty and four types of material hardship—home hardship, medical hardship, bill-paying hardship, and food insufficiency—taking into account various household-level characteristics.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Disability and Later-Life Economic Well-Being

Despite evidence suggesting that disability rates in the United States have declined, disability continues to be common among older adults (Schoeni, Freedman, & Wallace 2001). Over 19 million adults ages 65 and older, which represents nearly 50% of the older adult population, have a disability (compared to approximately 17% of the population ages 21 – 64) (Brault 2010). Older adults disproportionately experience all types of disability, including: vision problems (9.8% = population ages 65 and older versus 3.3% = population ages 15 and older); hearing problems (10.8% versus 3.1%); functional limitations (23.8% versus 8.3%); activities of daily living limitations (12.0% versus 3.9%); and instrumental activities of daily living limitations (19.3 versus 6.4%) (Brault 2010).

Disability can threaten individual-level emotional well-being and quality of life (Paul, Ayis, & Ebrahim 2007). It can also undermine household-level economic well-being by limiting paid employment among disabled individuals and their caregivers, and placing additional health-related financial demands on the household (Heflin, Wilmoth & London 2012; London, Heflin & Wilmoth 2011). Even though some older persons with disabilities may engage in paid labor or qualify for disability insurance, poverty rates among disabled older adults are higher than among non-disabled older adults; 11.7% and 6.7% of adults ages 65 and older with severe and non-severe disability, respectively, are in poverty compared to 5.0% of non-disabled older adults (Brault 2010).

The association between disability and poverty among older adults raises questions about the extent to which older disabled adults also disproportionately experience material hardship. Although poverty and various material hardships are conceptually distinct and only modestly correlated (Mayer & Jencks 1989, 1993; Beverly 2000; Boushey et al. 2001; Bradshaw & Finch 2003; Heflin, Sandberg, & Rafail 2009), the inability to meet basic needs is a critical indicator of household economic well-being. Similar to poverty, material hardship tends to decline with age (Mirowsky & Ross 1999; Bauman 2003), but to our knowledge there are no studies that specifically examine the extent to which disabled older adults experience different types of material hardship. Prior research on the working-aged population indicates that poor health or the presence of a work-limiting disability increases the risk of material hardship (Mayer & Jencks 1989; Bauman 1998; Corcoran, Heflin, & Siefert 1999; Heflin, Corcoran, & Siefert 2007, 2012; She & Livermore 2007; Parish, Rose, & Andrews 2009). Although individuals in various contexts variably use social programs, networks, and individual actions to prevent or mitigate the consequences material hardships in their lives (Heflin, London, & Scott 2012), it is reasonable to hypothesize that disability may continue to exert an influence on material hardship as individuals move into later life.

For example, there has been some research that specifically examines food insecurity among older adults. The findings indicate households with older adults are less likely to experience food insecurity than households with children under age 18 (Coleman-Jenson, Cole, & Singh 2013), but the risk of food insecurity is higher among older adults who are unmarried, living alone or with grandchildren, African American or Hispanic, at or below the poverty line, and have less than a high school education (Ziliak, Gundersen, & Haist 2008). In addition, disability increases the risk of food insecurity among older adults, net the effect of socioeconomic characteristics (Lee & Frongillo 2001). Despite the availability of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) for low-income older adults, many do not participate in the program due to perceived barriers and social stigma (Guthrie & Lin 2002). However, the program appears to be reaching disabled older adults with nutritional needs: older adults who receive SNAP benefits have higher levels of functional limitations than those who are eligible for the program but do not participate (Fey-Yensan, English, Pacheco, Belyea, & Schuler 2003). Thus, disability appears to influence the risk of hardship as well as the receipt of assistance from social programs.

Military Service and Later-Life Economic Well-Being

There is evidence that military service may enhance later-life economic well-being for some veterans. For cohorts who came of age in the middle of the 20th century, military service was a normative pathway to adulthood that provided access to higher education through the GI Bill (Bennett & McDonald 2013; Bound & Turner 2002; Turner & Bound 2003). Access to education, in addition to military experience and training, translated into an earnings advantage for the World War II cohort, but not for subsequent cohorts (Angrist 1990; Kleykamp 2013; Sampson & Laub 1996; Teachman & Tedrow 2004). In addition, this earnings advantage was enhanced by the other benefits offered through the Department of Veterans Affairs (Wilmoth & London 2011), such as low-interest home loans and access to health care, which contributed to better later-life financial security for veterans, particularly career-service veterans (Street & Hoffman 2013).

Although military service can put some veterans on a path that shapes early- and mid-life trajectories in ways that benefit later-life economic well-being, service-connected disability in early adulthood can also undermine later-life economic well-being by re-shaping employment, occupational, and income trajectories (MacLean 2013). Even though military personnel undergo health screenings that initially select them for better health (National Research Council 2006), the adjusted odds of any disability/functional limitation are higher among male veterans than male non-veterans (Wilmoth, London, & Parker 2011), veteran status differences in the risk of work-limiting disability increase with age (Dobkin & Shabani 2009), and older male veterans—especially war service veterans—experience steeper age-related increases in functional limitations than non-veterans (Wilmoth, London, & Parker 2010). In addition, compared to non-veterans and non-combat veterans, combat veterans are particularly at risk of having a work-limiting disability during the prime working ages of 25 to 55 years (MacLean 2010). Although disabled veterans potentially have access to additional support through the Department of Veterans Affairs, Fulton et al. (2009) found disabled veterans had significantly lower income than persons without disabilities, as well as non-veterans who reported the same number of disabilities.

This finding, in conjunction with our prior research on disability, veteran status, and economic well-being among the working-aged population (Heflin, Wilmoth & London 2012; London, Heflin & Wilmoth 2011), suggests that disability may have a greater impact of veterans than non-veterans. Using data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and focusing on work-limiting disability in households in which all members were under age 65 years, we found that there is a veteran advantage with respect to poverty and material hardship—housing, bill-paying, and medical hardship, and food insufficiency—that is substantially eroded when the veteran is disabled. Specifically, relative to the poverty rate among households that do not include a person with a work-limiting disability or veteran (i.e., non-disabled, non-veteran households) (12.16%): households with a non-disabled veteran are less likely to be in poverty (5.51% among non-disabled veteran households that do not contain other disabled non-veterans; 5.80% among non-disabled veteran households that include a disabled non-veteran); households that contain a veteran with a disability are slightly more likely to be in poverty (13.19%); and households that include a person with a disability and no veteran have a particularly high rate of poverty (32.53%) (London, Heflin & Wilmoth 2011). In addition, relative to non-disabled, non-veteran households: non-disabled veteran households are less likely to experience material hardship, while households with a disabled member, particularly a disabled veteran, are more likely to experience material hardship (Heflin, Wilmoth & London 2012).

Given the findings of previous research, we expect that veteran and disability statuses will jointly influence poverty and material hardship among older adult households, although the associations may not be as strong as the observed associations among working-aged households. Specifically, we hypothesize that: (1) older adult households that include a veteran and no disabled person will have the lowest levels of poverty and material hardship; (2) older adult households that include a disabled person and no veteran will be at a greater risk of poverty and material hardship than households that do not include a disabled person or veteran; and (3) households with a disabled veteran will be the most disadvantaged in terms of poverty and material hardship.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Sample

Data from the 2001 and 2004 panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) are used to examine households with at least one adult who is 65 years or older. Each interview in each SIPP panel consists of a core, with standard questions on demographics, labor force participation, and income, as well as a topical module, which includes questions on topics that change within a panel from one interview to the next. Interviews are conducted every four months and each panel is interviewed 12 times over 4 years. We use data from: the 8th wave of the 2001 and 2004 SIPP panels, which corresponds to data collected from June through September in 2003 and 2005, respectively. When survey weights are used, results are representative of the civilian (non-veteran and veteran), non-institutionalized population of the United States. We use imputed data as provided in the SIPP.

Measures

Dependent Variables

The analysis examines two separate aspects of economic well-being. The first dependent variable measures the household’s poverty status (yes = 1). The Census Bureau provides a continuous income-to-needs ratio in the SIPP data file. Income-to-needs indicates household income as a percentage of the official federal poverty line for a household of a given size. Values below 100 are indicative of poverty.

The second set of dependent variables measures material hardship in relation to four domains of material need—home, medical, bill-paying, and food hardship (Oullette 2004; Beverly 2001). We construct separate measures of each domain by utilizing a number of dichotomous indicators from the SIPP instrument that were designed for this purpose. Home hardship indicates whether, in the prior 12 months, the household had a problem with pests, a leaky roof or ceiling, broken windows, plumbing problems, or cracks in the walls, floor, or ceiling. Medical hardship indicates that a household member was not able to see a doctor or a dentist when they needed care in the last 12 months. Bill-paying hardship indicates whether, in the prior 12 months, the household was ever behind on utility payments or rent or mortgage, the telephone was ever disconnected, or other essential expenses were not met. The food insufficiency measure is constructed based on the question: Which of the following statements best describes the food eaten in your household in the last 12 months: enough to eat, sometimes not enough to eat, or often not enough to eat? We code those answering “sometimes” or “often not enough to eat” as food insufficient.

Independent Variable

As discussed in the literature review, on the basis of prior research, we expect that veteran and disability statuses interact to influence household-level poverty and material hardship. Given this expectation, the focal independent variable used in the analysis combines information on the characteristics of household members to measure the disability and veteran composition of households that include at least one adult who is 65 years or older. This variable is based on the respondent’s report of two characteristics of each household member: whether a household member has a disability, including work-limiting disability, hearing problems, vision problems, functional limitations, activities of daily living (ADL) limitations, or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) limitations, (yes = 1); and whether a household member ever served on active duty in the armed forces (yes = 1). This information was used to determine whether each household member is a non-disabled non-veteran, disabled non-veteran, non-disabled veteran, or disabled veteran. We then used this household member information to measure the household’s overall disability and veteran composition. Preliminary analysis revealed that all of the observed households in our analysis fall into one of five mutually exclusive categories.

The first household type, which we refer to as “non-disabled non-veteran households,” only includes non-disabled non-veterans who are either living alone or with other non-disabled non-veterans, such as a spouse/partner or child. This household type serves as the reference category in the multivariate analysis. The second household type includes at least one non-disabled veteran and no disabled non-veterans; we refer to these as “non-disabled veteran households.” An example is a household with a non-disabled veteran either living alone or with others who are not disabled. The third household type, which we refer to as “disabled veteran households,” includes at least one disabled veteran. The non-veterans in this household type, if any, may or may not have a disability. Preliminary analysis indicated the very few of the disabled veteran households also include a disabled non-veteran. Examples of this household type include disabled veterans living alone, with a spouse/partner, or with a child. The fourth household type includes at least one non-disabled veteran and at least one disabled non-veteran; we refer to these as “non-disabled veteran with a disabled non-veteran households.” An example is a household with a non-disabled veteran living with a disabled spouse/partner or a disabled sibling, child, or grandchild. The fifth household type, which we refer to as “disabled non-veteran households,” includes at least one disabled non-veteran and no one who is a veteran. An example of this household type is a disabled non-veteran living alone or with a non-veteran parent, spouse/partner, child, or other family member who may or may not have a disability.

Control Variables

The models include controls for a variety of household-level demographic characteristics that are known to be related to poverty and material hardship. The racial and ethnic composition of the household is indicated by a set of five dichotomous variables, which identify households that are White only (yes = 1), Black only (yes = 1), Hispanic only (yes = 1), Asian/Pacific Islander only (yes = 1), and all other race/ethnicities and racial/ethnic compositions, including mixed-race/ethnic households (yes = 1). The omitted reference category in multivariate analyses is White only households. Household-level educational attainment is indicated by the highest level of education achieved by any member of the household. Four dichotomous indicators identify households in which the highest educational attainment is: less than high school (reference category), high school graduate (yes =1), some college (yes =1), and college graduate or more (yes = 1). Three dichotomous variables identify the current marital status of the household reference person: never-married (yes = 1), previously-married (i.e., divorced, widowed, or separated) (yes = 1), and married (reference category). Dichotomous variables respectively indicate the presence of children less than age 18 years old (yes = 1) and the presence of adults ages 18- 64 (yes = 1) in the household. We also include a control for whether the household is located in a metropolitan area (yes = 1) and the SIPP panel year (2004 = 1). Finally, the multivariate models for material hardship include a control for household income-to-needs ratio, which is measured as a continuous variable.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA version 10.1 and all analyses after Table 1 are weighted using the household-level panel-year weight. The variables in this analysis are based on household-level measures and therefore have no missing data; there are 9,528 cases with full information. Following a description of the sample, we present the percentage living in poverty and experiencing each of the four types of material hardship in relation to the five household-level disability and veteran status categories. Then, we present results from logistic regression analyses predicting poverty status and the four types of material hardship. The multivariate model includes the household disability and veteran status variable, the other household-level control variables, and the dichotomous variable for survey year, which controls for the change in poverty and material hardship over the study period. All models pass the likelihood ratio chi-square test of model fit, and are free of multicollinearity and cases with undue influence.

Table 1.

Unweighted Descriptive Statistics (N=9,528)

| Variable | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Poverty | 10.87 |

| Home Hardship | 1.07 |

| Medical Hardship | 4.75 |

| Bill Paying Hardship | 6.84 |

| Food Insufficiency | 0.70 |

| Household Disability and Veteran Status | |

| Non-disabled veteran | 12.14 |

| Disabled veteran | 16.56 |

| Non-disabled veteran with a disabled non-veteran | 4.75 |

| Disabled non-veteran | 19.05 |

| No person with disability or veteran | 47.50 |

| Household Race/Ethnicity | |

| White Only | 81.51 |

| Black Only | 9.07 |

| Hispanic Only | 4.86 |

| Asian Only | 1.59 |

| Other and Mixed Race/Ethnicity | 2.97 |

| Highest Educational Attainment in Household | |

| Less than high school | 16.58 |

| Graduated high school | 32.17 |

| Some college | 29.25 |

| College | 22.00 |

| Marital Status of Householder | |

| Currently Married | 37.21 |

| Never Married | 5.89 |

| Previously Married | 56.90 |

| Household Income-to-Needs | 3.00 |

| Children < 18 Years in Household (1=yes) | 3.69 |

| Adults Aged 18–64 in Household (1=yes) | 19.09 |

| Metropolitan Household (1=yes) | 75.97 |

| Survey Year | |

| 2001 | 33.03 |

| 2004 | 66.97 |

RESULTS

Sample Description

Table 1, which presents the unweighted descriptive statistics, indicates that almost 11% of households containing an older adult are in poverty. Bill paying hardship (6.84%) and medical hardship (4.75%) are most common. In contrast, home hardship (1.07%) and food insufficiency (0.70%) are relatively rare. Given the observed low prevalence of these two material hardships and the relatively small number of households experiencing them, the multivariate results pertaining to them should be interpreted cautiously; non-significant coefficients might be due to inadequate statistical power. Almost half (47.5%) of older-adult households do not contain anyone who is disabled or a veteran. Nearly one-fifth (19%) are disabled non-veteran households and a slightly lower percentage (16.56%) are disabled veteran households. Approximately 12% of older adult households include a non-disabled veteran, while 4.75% include a non-disabled veteran and a disabled non-veteran. Taken together, slightly more than one-third of older adult households include a veteran, which suggests the importance of taking prior military service into account in analyses of older adult economic well-being, as well as other, outcomes.

The majority of older adult households are White only (81.51%), highly educated (51.25% have at least one member with some college or more), previously married (56.9% of household reference persons), and metropolitan (75.97%). Most were included in the 2004 SIPP panel (66.97%). The average income-to-needs ratio for older adult households is 3.00. Very few older adult households contain children under age 18 (3.69%); however, approximately one-fifth (19.09%) contain a working-aged, 18–64 year old, adult.

Poverty and Material Hardship in Older-Adult Households

Table 2 reports the percentage reporting poverty and specific material hardships by household disability and veteran status categories. The percentage in poverty is notably high among disabled non-veteran households (20.57%), which also have a relatively high percentage reporting home hardship (1.75%) and bill-paying hardship (9.42%). In contrast, disabled veteran households have a low percentage in poverty (5.69%), but still experience the highest rates of medical hardship (6.13%) and food insufficiency (0.86%). Non-disabled veteran households are faring the best, with the lowest rates of poverty (3.75%), home hardship (0.20%), medical hardship (0.99%), bill-paying hardship (2.97%), and food insufficiency (0%). Households with a non-disabled veteran and a disabled non-veteran are more similar to non-disabled veteran households without a disabled non-veteran than the other household types, but have slightly higher rates of poverty (4.86%), home hardship (0.74%), medical hardship (2.97%), bill-paying hardship (4.14%), and food insufficiency (0.62%). Older-adult households with no one who is disabled or a veteran in the household tend to fall in between the non-disabled veteran households and the disabled non-veteran households. These bivariate results demonstrate the substantial variance in poverty and material hardships across older adult households that differ with respect to the disability and veteran statuses of their members. Given that these households are likely to vary on a range of characteristics that are related to poverty and material hardship, it is important to control for potentially confounding factors in multivariate models.

Table 2.

Percentage Reporting Poverty and Specific Hardships, by Household Disability and Veteran Status Categories

| Household Disability and Veteran Status | Poverty | Home Hardship |

Medical Hardship |

Bill-paying Hardship |

Food Insufficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-disabled veteran | 3.75 | 0.20 | 0.99 | 2.97 | 0.00 |

| Disabled veteran | 5.69 | 0.97 | 6.13 | 6.46 | 0.86 |

| Non-disabled veteran with a disabled non-veteran | 4.86 | 0.74 | 2.97 | 4.14 | 0.62 |

| Disabled non-veteran | 20.57 | 1.75 | 5.11 | 9.42 | 0.74 |

| No person with disability or veteran | 11.21 | 1.08 | 5.26 | 7.19 | 0.81 |

Note. Chi-square tests indicate significant differences (p<.0001) in poverty and all of the specific hardships across the household disability and veteran status categories.

Multivariate Analyses of Poverty and Material Hardship

Poverty

Table 3 present the results of a multivariate logistic regression model of poverty among older adult households. Compared to households containing no person with any of the six measured disabilities or veteran, and controlling for household characteristics, non-disabled veteran households are less likely to be in poverty (OR = 0.55), while disabled non-veteran households are more likely to be in poverty (OR = 1.53). Disabled veteran households and non-disabled veteran households with a disabled non-veteran are not significantly different from households with no person with a disability or veteran. Poverty is more likely among Black only, Hispanic only, Asian only, and mixed race/ethnicity households (compared to White only households), never married and previously married households (compared to currently married household), and households with children under 18 (compared to households with no children under 18). Poverty is less likely among households where the highest education of a member is high school graduate, some college, or college (compared to less than high school), households that contain adults aged 18 to 64 (compared to households without a working-aged adult), and households in metropolitan areas (compared to households in non-metropolitan areas). Poverty is also lower in 2004 than in 2001.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Poverty

| Variable (reference category) | Poverty | |

|---|---|---|

| b (SE) |

OR | |

| Household Veteran and Disability Statuses (No person with disability or veteran) |

||

| Non-disabled veteran | −0.601 | 0.55** |

| (0.189) | ||

| Disabled veteran | −0.264 | 0.77 |

| (0.155) | ||

| Non-disabled veteran with a disabled non-veteran | −0.052 | 0.95 |

| (0.270) | ||

| Disabled non-veteran | 0.423 | 1.53*** |

| (0.104) | ||

| Household Race/Ethnicity (White Only) | ||

| Black Only | 1.001 | 2.72*** |

| (0.100) | ||

| Hispanic Only | 1.119 | 3.06*** |

| (0.160) | ||

| Asian Only | 0.693 | 2.00** |

| (0.228) | ||

| Other and Mixed Race/Ethnicity | 0.696 | 2.00** |

| (0.232) | ||

| Highest Education in Household (Less than high school) |

||

| High School Graduate | −0.640 | 0.53*** |

| (0.092) | ||

| Some College | −0.961 | 0.38*** |

| (0.107) | ||

| College | −1.596 | 0.20*** |

| (0.150) | ||

| Marital Status of Householder (Currently Married) |

||

| Never Married | 0.663 | 1.94*** |

| (0.156) | ||

| Previously Married | 0.297 | 1.35** |

| (0.100) | ||

| Child < 18 Years in Household (No) | ||

| Yes | 0.445 | 1.56* |

| (0.198) | ||

| Adult 18–64 Years in Household (No) | ||

| Yes | −0.631 | 0.53*** |

| (0.136) | ||

| Metropolitan Household (No) | ||

| Yes | −0.491 | 0.61*** |

| (0.081) | ||

| Survey Year (2001) | ||

| 2004 | −0.434 | 0.65*** |

| (0.077) | ||

| Intercept | −1.371 | *** |

| (0.148) | ||

| Number of Observations | 9,528 | |

| Wald Chi2 | 574.08 | *** |

Note. Significance levels:

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Material Hardship

Table 4 presents four separate logistic regression models predicting specific types of material hardship. Model 1 indicates that, compared to households with no person with any disability or veteran, disabled veteran households and disabled non-veteran households are significantly more likely to experience home hardship (OR = 2.91 and OR = 2.47 respectively). Home hardship is more likely among Black only, Hispanic only, and Asian only households (compared to White only households), as well as never and previously married households (compared to currently married households).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Four Types of Material Hardship

| Home Hardship | Medical Hardship | Bill-paying Hardship | Food Insufficiency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (reference category) | b (SE) |

OR | b (SE) |

OR | b (SE) |

OR | b (SE) |

OR |

| Household Veteran and Disability Statuses (No person with disability or veteran) |

||||||||

| Non-disabled veteran | −0.414 | 0.661 | −0.800 | 0.449 * | 0.073 | 1.076 | ----- a | ----- |

| (0.729) | (0.371) | (0.238) | ----- | |||||

| Disabled veteran | 1.069 | 2.911 * | 0.940 | 2.559 *** | 0.680 | 1.975 *** | 1.315 | 3.72 ** |

| (0.499) | (0.198) | (0.180) | (0.500) | |||||

| Non-disabled veteran with a disabled Non-veteran |

0.932 | 2.540 | 0.121 | 1.129 | 0.177 | 1.194 | 2.069 | 7.91 * |

| (0.660) | (0.346) | (0.291) | (0.965) | |||||

| Disabled non-veteran | 0.905 | 2.472 * | 0.584 | 1.793 ** | 0.596 | 1.814 *** | 0.369 | 1.45 |

| (0.448) | (0.171) | (0.143) | (0.471) | |||||

| Household Race/Ethnicity (White Only) | ||||||||

| Black Only | 1.169 | 3.219 *** | 0.457 | 1.580 ** | 1.070 | 2.915 *** | 1.116 | 3.05 ** |

| (0.300) | (0.155) | (0.114) | (0.396) | |||||

| Hispanic Only | 1.268 | 3.553 ** | 0.197 | 1.218 | 0.648 | 1.912 *** | 0.865 | 2.37 |

| (0.431) | (0.251) | (0.184) | (0.529) | |||||

| Asian Only | 1.516 | 4.555 ** | 0.834 | 2.302 ** | 0.597 | 1.817 * | 1.996 | 7.36 *** |

| (0.450) | (0.289) | (0.273) | (0.491) | |||||

| Other and Mixed Race/Ethnicity | −0.055 | 0.947 | −0.048 | 0.953 | 0.123 | 1.131 | 1.270 | 3.56 |

| Highest Education in Household (Less than high school) |

(0.757) | (0.292) | (0.266) | (0.712) | ||||

| High School Graduate | −0.207 | 0.813 | −0.262 | 0.769 | −0.338 | 0.713 ** | −0.317 | 0.73 |

| (0.340) | (0.156) | (0.120) | (0.417) | |||||

| Some College | −0.540 | 0.947 | 0.084 | 1.088 | −0.211 | 0.810 | 0.276 | 1.32 |

| (0.325) | (0.160) | (0.129) | (0.377) | |||||

| College | 0.021 | 1.021 | −0.275 | 0.759 | −0.662 | 0.516 *** | −0.670 | 0.51 |

| Marital Status of Householder (Currently Married) |

(0.395) | (0.225) | (0.185) | (0.723) | ||||

| Never Married | 1.049 | 2.855 * | 0.387 | 1.472 | 0.233 | 1.262 | 2.740 | 15.5 *** |

| (0.423) | (0.223) | (0.192) | (0.714) | |||||

| Previously Married | 0.900 | 2.461 ** | 0.464 | 1.591 ** | 0.201 | 1.223 | 2.099 | 8.15 ** |

| (0.281) | (0.140) | (0.119) | (0.661) | |||||

| Household Income-to-Needs | −0.181 | 0.834 | −0.204 | 0.815 ** | −0.261 | 0.770 *** | −0.520 | 0.59 ** |

| (0.101) | (0.075) | (0.045) | (0.176) | |||||

| Child < 18 Years in Household (No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.453 | 1.574 | 0.227 | 1.255 | 0.815 | 2.258 *** | 1.054 | 2.87 ** |

| (0.376) | (0.217) | (0.173) | (0.491) | |||||

| Adult 18–64 Years in Household (No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.576 | 1.78 | 1.039 | 2.82 *** | 0.508 | 1.66 *** | −0.588 | 0.57 |

| (0.297) | (0.139) | (0.128) | (0.422) | |||||

| Metropolitan Household (No) | ||||||||

| Yes | −0.001 | 0.999 | −0.005 | 0.995 | 0.183 | 1.201 | 0.003 | 1.00 |

| (0.280) | (0.125) | (0.105) | (0.378) | |||||

| Survey Year (2001) | ||||||||

| 2004 | 0.101 | 1.107 | 0.208 | 1.231 | 0.100 | 1.106 | 0.047 | 1.05 |

| (0.244) | (0.116) | (0.095) | (0.289) | |||||

| Intercept | −6.488 | *** | ||||||

| (0.927) | ||||||||

| Number of Observations | 8,418 | |||||||

| Wald Chi2 | 110.38 | *** | ||||||

Note.

No non-disabled veteran household reported food insufficiency. Thus, 1,100 non-disabled veterans were dropped from this analysis. The N for this analysis is 8,418.

Significance levels:

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Model 2 reveals disabled veteran households (OR = 2.56) and disabled non-veteran households (OR = 1.79) are significantly more likely, while non-disabled veteran households are significantly less likely (OR = 0.45), to experience medical hardship than households with no person with any disability or veteran. Medical hardship is also more likely among Black only and Asian only households (compared to White only households), previously married households (compared to currently married households), and households with adults aged 18–64 (compared to households without a working-aged adult). Households with higher income-to-needs ratios are less likely to experience medical hardship.

Model 3 indicates that, compared to households with no person with any disability or veteran status, disabled veteran households and disabled non-veteran households are significantly more likely to experience bill-paying hardship (OR = 1.96 and OR = 1.81 respectively). Bill-paying hardship is also more likely among Black only, Hispanic only, and Asian only households (compared to White only households), households with children under 18 (compared to households without children), and households with adults 18–64 (compared to households with no working-aged adults). The likelihood of bill-paying hardship is lower among high school and college graduate households (compared to households with no high school graduate), and households with higher income-to-needs ratios.

Model 4 examines food insufficiency. Non-disabled veteran households are not included in this model because none of these households reported food insufficiency (see Table 2). Compared to households with no person with any disability or veteran, households with a disabled veteran and households with a non-disabled veteran and disabled non-veteran are more likely to experience food insufficiency (OR = 3.72 and OR = 7.91 respectively). The likelihood of food insufficiency is more likely among Black only and Asian only households (compared to White only households), never married and previously married households (compared to currently married households), and households with children under age 18 (compared to households with no children). Households with higher income-to-needs ratios are less likely to report food insufficiency.

DISCUSSION

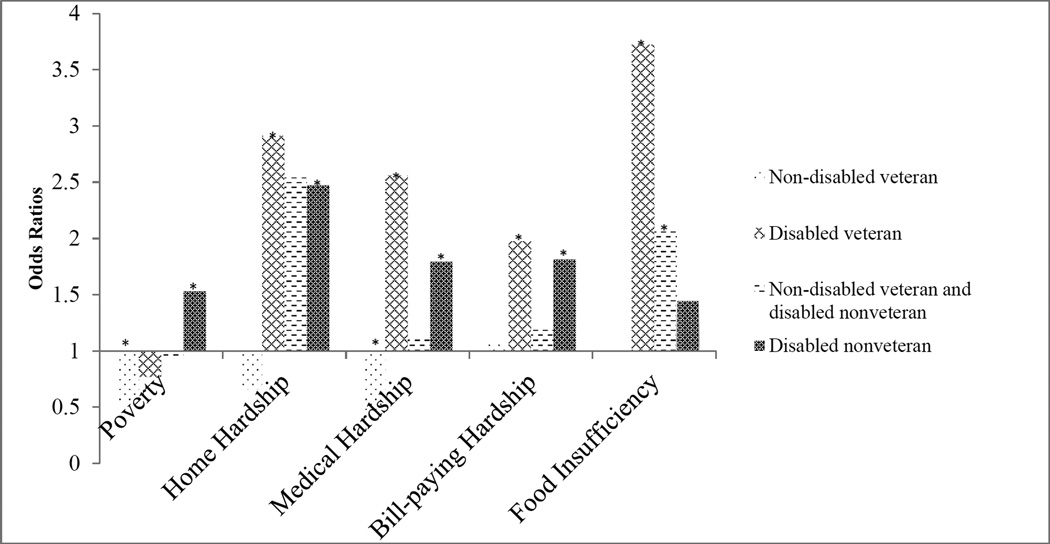

The results of this study indicate that disability and veteran statuses intersect in unique ways to influence older adult household-level poverty and material hardship. To help synthesize the results, Figure 1 summarizes the main findings with regard to the adjusted odds of poverty and material hardship by household disability and veteran status. It shows the relatively advantaged position of households that contain a veteran without any disability. Compared to non-disabled non-veteran households, non-disabled veteran households are significantly less likely to be in poverty or report medical hardship. Non-disabled veteran with a disabled non-veteran households are similar except that they are significantly more likely to report food insufficiency. Disabled non-veteran and disabled veteran households are at a disadvantage relative to non-disabled non-veteran households. Disabled non-veteran households are more likely to be in poverty and to experience home hardship, medical hardship, and bill-paying hardship. Although disabled veteran households are not significantly different than non-disabled non-veteran households in terms of the odds of poverty, they exhibit higher odds of home hardship, medical hardship, bill-paying hardship, and food insufficiency. The significantly higher rates of all types of material hardship, net of income-to-needs and other factors, in older households that contain disabled veterans is consistent with findings for working-aged households (Heflin, Wilmoth & London 2012). The consistency of these results across households that are at different stages of the life course suggests the need for careful evaluation of the adequacy of the programs available to support disabled veterans and their families.

Figure 1.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Poverty and Material Hardship by Household Veteran and Disability Status

Notes: Adjusted odds ratios are based on the models presented in Tables 3 and 4.

* p<.05 significant differences between households with no disability or veterans and the indicated household type.

Overall, our results suggest that older adult households are not uniformly at risk of poverty and material hardship. We find that prior military service is positively associated with later-life economic well-being if the household contains a veteran who is not disabled. However, older adult households that include a disabled member, regardless of veteran status, are at risk of experiencing economic hardship. These findings extend prior research on poverty and material hardship by focusing on older adult households and distinguishing households on the basis of veteran status and the presence of any type of disability. Consistent with the findings of Mirowsky and Ross (1999) and Bauman (2003), the levels of poverty and material hardship reported by the older adult households in this analysis, as indicated by the percentages in the descriptive analysis, are lower than the levels for working-aged households that were observed by London, Heflin & Wilmoth (2011) and Heflin, Wilmoth & London (2012). However, somewhat counter to our expectations based on the availability of social programs that are available to all older adults, we document associations in the multivariate analyses that are of similar magnitude to those documented for working-aged households in many cases. It should be noted that our results are descriptive rather than causal. It is possible that the households examined in this study differ with respect to unobserved factors that influence the risk of poverty and material hardship. Future research should aim to theorize and empirically evaluate the extent to which the associations we document in this study persist when other potentially confounding factors are taken into account.

Our analysis suggests that current public income support programs for disabled older adults, including those provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs to disabled veterans, are not sufficient and need to be adjusted (Fulton et al. 2009). Moreover, since we control for income-to-needs in the models of material hardship, our results suggest that income support alone will not be sufficient to help households—especially households that include disabled members, regardless of veteran status—meet basic needs. It is beyond the scope of this paper to examine how participation in specific federal or state programs, including SNAP, SSI, SSDI, and Medicaid, or receipt of particular VA benefits is associated with poverty and material hardship among older adult households. However, we believe that this is an important topic for future research that focuses on individual- and household-level well-being. In addition, it is important to consider how the effects of older adult poverty and material hardship impact family members who provide social, instrumental, and economic support, as well as the communities in which they reside. Given that poverty and material hardship are more prevalent among disabled older adults, such research would reveal the broader consequences of disability and potential avenues for the mitigation of those consequences through policy initiatives.

The distinctions in economic well-being among older adult households that are documented in this study are important for social workers to take into consideration as they coordinate care for, provide services to, and advocate on behalf of older adults. Although social workers practicing at the micro level routinely consider how the presence of disability in a household might shape their client’s unique needs, these results underscore the relevance of social workers also considering whether any household members are veterans. This is particularly salient given the prevalence of male veterans among current cohorts of older adults (U.S. Census Bureau 2012) and the consistently higher odds of all types of material hardship in disabled veteran households that we document. These older veterans, and their spouses, potentially have access to an additional layer of support through the Department of Veterans affairs (Street & Hoffman 2013; Wilmoth & London 2011), which social workers may be able to tap into as an additional resource depending on the veteran’s military service history and, if applicable, the nature of their disability. Social workers whose practice focus on mezzo level activities like organizing community-level programs and designing educational outreach programs also need to consider the unique fiscal needs of households with disabled veterans. Partnering with local veterans’ groups could facilitate the distribution of information, and improve the service delivery, to disabled veteran households. Social workers who advocate for improved effectiveness of old age policies at the macro level should broaden the scope of their work beyond traditional sources of support for older adults, such as the services supported by the Older Americans Act and the support provided through Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, to include programs offered through the Department of Veterans Affairs. Taking a comprehensive approach to policy formation will help to ensure the adequacy of the safety net that is provided to older adults who have served our country through military service.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This research was supported by a “Survey of Program Participation (SIPP) Analytic Research Small Grant” from the National Poverty Center, Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, University of Michigan (Co-PIs: Colleen M. Heflin, Andrew S. London, & Janet M. Wilmoth). Additional support was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, “Military Service and Health Outcomes in Later Life” (1 R01 AG028480-01) (PI: Janet M. Wilmoth).

Contributor Information

Janet M. Wilmoth, Department of Sociology and the Aging Studies Institute, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA

Andrew S. London, Department of Sociology and the Aging Studies Institute, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA

Colleen M. Heflin, Harry S. Truman School of Public Affairs, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA

REFERENCES

- Angrist J. Lifetime earnings and the Vietnam Era draft lottery: Evidence from Social Security administrative records. American Economic Review. 1990;80:313–336. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KJ. Direct Measures of Poverty as Indicators for Economic Need: evidence from the survey of income and program participation. Population Division Technical Working Paper 30. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau Population Division; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KJ. [Accessed online March 10, 2014];Age and material well-being in the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Joint Statistical Meetings, Social Statistics Section, U.S. Census Bureau. 2003 http://www.census.gov/hhes/well-being/files/Age%20and%20Material%20Well-Being%20in%20the%20Survey%20of%20Income%20and%20Program%20Participation.pdf.

- Bennett P, McDonald K. Military service as a pathway to early socioeconomic achievement for disadvantaged groups. In: Wilmoth JM, London AS, editors. Life-Course Perspectives on Military Service. New York: Routledge; 2013. pp. 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Beverly S. Material Hardship in the United States: Evidence from the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Social Work Research. 2000;25(3):143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Beverly S. Measures of Material Hardship: Rationale and Recommendations. Journal of Poverty. 2001;5(1):23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bound J, Turner S. Going to war and going to college: Did World War II and the G.I. Bill increase educational attainment for returning veterans? Journal of Labor Economics. 2002;20:784–815. [Google Scholar]

- Boushey H, Brocht C, Gundersen B, Bernstein J. Hardships in America: The Real Story of Working Families. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J, Finch N. Overlaps in Dimensions of Poverty. Journal of Social Policy. 2003;32:513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Brault MW. [Accessed online March 10, 2014];Americans with Disabilities, (2010). Current Population Reports. 2012 :P70–P131. http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p70-131.pdf.

- Coleman- Jensen A, Nord M, Singh A. [Accessed online March 31, 2041];Household food insecurity in the United States in 2012. United States Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Report, Number 155. 2013 http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err155.aspx.

- Corcoran ME, Heflin CM, Siefert K. Food Insufficiency and Material Hardship in Post-TANF Welfare Families. Ohio State Law Review. 1999;60:1395–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin C, Shabani R. The health effects of military service: Evidence from the Vietnam draft. Economic Inquiry. 2009;47:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fey-Yensan N, English C, Pacheco HE, Belyea M, Schuler DJ. Elderly food stamp participants are different from eligible nonparticipants by level of nutrition risk but not nutrient intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(1):103–7. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton L, Belote J, Brooks M, Coppala MN. A comparison of veteran and non-veteran income. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2009;20(3):184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JF, Lin BH. Overview of the diets of lower- and higher-income elderly and their food assistance options. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34:S31–S41. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, Siefert K. Work Trajectories, Income Changes, and Food Insufficiency in a Michigan Welfare Population. Social Service Review. 2007;81(1):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Heflin C, London AS, Scott E. Mitigating Material Hardship: The Strategies Low-Income Mothers Employ to Reduce the Consequences of Poverty‖. Sociological Inquiry. 2011;81(2):223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Heflin CM, Sandberg J, Rafail P. The Structure of Material Hardship in U.S. Households: An Examination of the Coherence Behind Common Measures of Well-Being. Social Problems. 2009;56(4):746–764. [Google Scholar]

- Heflin C, Wilmoth JM, London AS. Veteran Status and Material Hardship: The Moderating Influence of Disability. Social Service Review. 2012;86(1):119–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kleykamp M. Labor market outcomes among veterans and military spouses. In: Wilmoth JM, London AS, editors. Life-Course Perspectives on Military Service. New York: Routledge; 2013. pp. 144–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Frangillo EA., Jr Factors associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons: The importance of functional impairement. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56B(2):S94–S99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.2.s94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London AS, Heflin C, Wilmoth JM. Work-Related Disability, Veteran Status, and Poverty: Implications for Family Well-Being. Journal of Poverty. 2011;15:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean A. The Things They Carry: Combat, Disability, and Unemployment among US Men. American Sociological Review. 2010;75(4):563–585. doi: 10.1177/0003122410374085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean A. A matter of life and death: Military service and health. In: Wilmoth JM, London AS, editors. Life-Course Perspectives on Military Service. New York: Routledge; 2013. pp. 200–220. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SE, Jencks C. Poverty and the distribution of material hardship. Journal of Human Resources. 1989;24:88–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SE, Jencks C. Recent Trends in Economic Inequality in the United States: Income vs. Expenditures vs. In: Papadimitriou D, Wolff E, editors. Material Well- Being. London: Poverty and Prosperity in the USA in the Late Twentieth Century, MacMillan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Economic Hardship Across the Lifecourse. American Sociological Review. 1999;64(4):548–69. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan D, Brown M. Gerontological Social Work: Meeting the Needs of Elder and their Families”. In: Wilmoth JM, Ferraro K, editors. Gerontology: Perspectives and Issues. 4th edition. New York: Springer Pub; 2013. pp. 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (U.S.) Committee on the Youth Population and Military Recruitment. Assessing fitness for military enlistment: Physical, medical, and mental health standards. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette T, Burstein N, Long D, Beecroft E. Measures of Material Hardship: Final Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Parish S, Roderick AR, Andrews M. Income poverty and material hardship among US women with disabilities. Social Service Review. 2009;83:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Paul C, Ayis S, Ebrahim S. Disability and Psychosocial Outcomes in Old Age. Journal of Aging and Health. 2007;19(5):723–741. doi: 10.1177/0898264307304301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson R, Laub J. Socioeconomic achievement in the life course of disadvantaged men: Military service as a turning point, circa 1940-1965. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni RF, Freedman VA, Wallace RB. Consistent, persistent, widespread, and robust? Another look at recent trends in old-age disability. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56(4):S206–S218. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Patterson RS. When nations call: How wartime military service matters for the life course and aging. Research on Aging. 2006;28:12–36. [Google Scholar]

- She P, Livermore GA. Material Hardship, Poverty, and Disability Among Working-Age Adults‖. Social Science Quarterly. 2007;88(4):970–989. [Google Scholar]

- Spiro A, Schnurr PP, Aldwin CM. Combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older men. Psychology and Aging. 1994;9:17–26. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street D, Hoffman J. Military Service, Social Policy, and Later-Life Financial and Health Security. In: Wilmoth JM, London AS, editors. Life- Course Perspectives on Military Service. NY: Routledge; 2013. pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman JD, Tedrow LM. Wage, earnings, and occupational status: Did World War II veterans receive a premium? Social Science Research. 2004;33:581–605. [Google Scholar]

- Turner S, Bound J. Closing the gap or widening the divide: The effects of the BI Bill and World War II on the educational outcomes of Black Americans. Journal of Economic History. 2003;63(1):145–177. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed online March 10, 2014];Table B21001: Sex by Age by Veteran Status for the Civilian Population 18 Years and Older. 2012 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_B21001&prodType=table.

- Wilmoth JM, London AS. Aging Veterans: Needs and Provisions. In: Settersten R, Angel J, editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Aging. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth JM, London AS, editors. Life-Course Perspectives on Military Service. New York: Routledge Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth JM, London AS, Parker W. Military service and men’s health trajectories in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2010;56(6):744–755. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth JM, London AS, Parker W. Sex Differences in the Relationship between Veteran Status and Functional Limitations and Disabilities. Population Research and Policy Review. 2011;30:333–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ziliak JP, Gundersen C, Haist MP. [Accessed online March 31, 2014];The Causes, Consequences, and Future of Senior Hunger in America, Technical Report submitted to the Meals on Wheels Association of America Foundation. 2008 http://www.mowaa.org/document.doc?id=13.